Abstract

We investigated the environmental conditions that induce a flight response in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum Herbst (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), including resource quality, temperature, relative humidity, and light. Over 72-h trial periods, we observed the proportion of individuals emigrating by flight to range from 0.0 in extreme heat or cold to 0.82 with starvation. Resource quality, presence of a light source, and temperature all directly influenced the initiation of the flight response. We did not detect any effect of relative humidity or sudden change in temperature on the incidence of flight. We discuss our findings in the context of Tribolium ecology and evolution.

Keywords: dispersal, behavioural response, migration, environmental cues, metapopulation, Coleoptera, Tenebrionidae

Introduction

Dispersal is a process that affects both the ecology and the evolution of populations. Of primary concern to population ecologists is the effect of dispersal on the spatial distribution and local abundance of individuals in populations. In an environment with a patchy resource distribution, dispersal is essential to the persistence of populations owing to the ephemeral nature of local resources (Clobert et al., 2012). Evolutionary geneticists are concerned with dispersal effects on population genetic structure, because gene flow determines the amount of genetic variation among populations. Dispersing individuals of most species incur an increased risk of mortality and/or an increased difficulty of finding a mate (reviewed in Johnson & Gaines, 1990; Clobert et al., 2012). Natural selection favors dispersal when the fitness costs of remaining in place exceed those incurred by dispersal, as first pointed out by Van Valen (1971). As a result, dispersal is believed to be condition-dependent, occurring in response to environmental cues (Clobert et al., 2012). These cues signal deterioration of the local environment (Bowler & Benton, 2005). Here, we report our studies of flight initiation in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum Herbst (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), in response to environmental cues, many associated with a deteriorating environment.

The red flour beetle is a globally distributed human communal, inhabiting stored cereal products. Although widely distributed, the species lives in stored products which are spatially separated resulting in a meta-population structure (Levins, 1970; Drury et al., 2009). Its average, genome-wide FST is 0.180 (Drury et al., 2009), suggesting that dispersal among patches, colonization of new patches, and local extinctions (Wade & McCauley, 1988), including those resulting from fumigation, play a significant role in this species’ ecology and evolution. Both, the scale of local adaptation and the opportunity for out-breeding depression are functions of dispersal and gene flow (Slatkin, 1973; Slatkin & Barton, 1989). There is debate about the degree to which dispersal in this species occurs by active flight or by passive anthropogenic movement between patches of resource (Campbell & Arbogast, 2004; Campbell et al., 2010; Drury et al., 2009; Ridley et al., 2011). Studies have shown that, during dispersal, individuals of T. castaneum are attracted more strongly to certain types of resources than they are to others (Ahmad et al., 2013a,b). It has also been shown that beetles disperse locally by active flight among neighboring grain stores (Ridley et al., 2011). Here, we report the results of a set of experiments investigating the effects of resource quality and availability, light, temperature, and relative humidity on the tendency to initiate dispersal by flight.

Material and methods

Beetle rearing

The population used in this study was established from approximately 200 adult beetles collected in 2007 from animal feed on a farm in Adrian, Western Missouri, USA (38.39N, 94.35W). After establishment in the laboratory, the population was maintained at a size of > 200 individuals on standard medium (20:1 ratio of flour to brewer's yeast, wt/wt), in glass 0.5-l (half-quart) jars, in 24 h darkness, at 28 °C, and approximately 70% r.h.

Flight chambers

To measure the incidence of flight, we created flight chambers by placing a 250-ml centrifuge bottle (61.5 × 135.1 mm) inside a 1-l (quart) jar (170 × 85 mm; see Figure 1). A wooden dowel (11 × 2 cm) was fastened to the bottom of the centrifuge bottle, with the unattached end extending 2 mm below the opening with a 7.5 mm gap along all sides. Preliminary experiments confirmed that this was sufficient to prevent escape or dispersal by crawling instead of flight. Beetles were introduced to the inner bottle and only those beetles escaping by flight were collected in the outer bottle. To test the possibility that, after escape by flight, a beetle would re-enter the inner bottle, we placed 40 adults in each of 10 outer bottles. None of the total of 400 beetles returned to the inner chamber. We conclude that beetles only leave the interior bottle by flying and do not return.

Figure 1.

Components and construction of experimental flight chambers. From left to right: glass 1-l (quart) jar, 250 ml centrifuge bottle, 11 cm dowel rod, and the items assembled in the flight chamber configuration.

Flight trials

In all cases, 24 h before each flight trial, experimental adult beetles were sequestered in groups of 40 in a 28 °C incubator without food. To mitigate the effects of sudden temperature change on flight response, 3 h prior to testing, beetles were acclimated to the experimental temperature by sealing them within flight chambers. After the acclimation period, the seal was removed and beetles were free to fly out of the chamber for 72 h. We investigated the possibility that these pre-treatments had an effect on the flight response, using a factorial experiment with different combinations of starvation, acclimation, and light treatments. The overall fit of a linear model was significant (F7,112 = 9.66, P<0.001; r2 = 0.337), but there were only two significant effects: a main effect of light treatment (F1,112 = 38.13, P<0.001) and an interaction between food quality and light (F1,112 = 23.10, P<0.001). Thus, the pre-treatment handling did not affect the results reported below.

For each condition, the propensity to fly was assessed by placing 40 beetles in the center of a flight chamber. Ten replicate fight chambers were used for each condition. All trials took place over a 72-h interval, at 75% r.h., 35 °C, and constant light unless otherwise noted. After the 72-h period, flight chambers were removed from incubators and the beetles inside the 1-l and outside the centrifuge bottle were counted. A small number in the inner chamber died during the experiment and their numbers were removed from our calculations. We calculated the incidence of flight for each replicate as follows:

Flight incidence = no. outside / (no. outside + no. live inside).

Experiment 1: Food and temperature

We exposed test beetles to either standard medium (10 g) or indigestible α-cellulose medium (10 g) across a range of five temperatures spanning the species’ physiologically active range (20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 °C). After that period, the beetles, alive and dead, were counted inside and outside the flight chamber. Trials were run with 20 replicates at a time [10 with standard medium and 10 with α-cellulose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a single temperature. Flight chambers were randomly positioned within the incubator. This procedure was repeated 5×, once for each temperature.

Experiment 2: Food and light

To determine the influence of light on the propensity of beetles to fly, we set up a factorial experiment with light or no light combined with either 10 g standard medium or 10 g α-cellulose. We ran two trials with 20 replicates per trial (a total of 800 beetles) with flight chambers randomly positioned within the incubator.

Experiment 3: Variation in food availability

In this experiment, we varied the amount of food by mixing four 10-g combinations of standard medium and α-cellulose: (1) 100% standard medium, (2) 50% standard medium and α-cellulose, (3) 7.5% standard medium and 92.5% α-cellulose, and (4) 100% α-cellulose. There were 10 replicates of each treatment and all trials were performed simultaneously with flight chambers randomly distributed throughout the incubator.

Experiment 4: Relative humidity and food quality

Similar to experiment 2, we combined the two types of medium (standard or α–cellulose) with two humidities [high (ca. 78%) and low (ca. 20%)]. Relative humidity of the high treatment ranged from 71 to 85% (mean ± SEM = 78 ± 3%), whereas that of the low relative humidity treatment ranged from 17 to 25% (20.3 ± 1%). Trials were performed in a humidity-controlled incubator.

Statistical analysis

As recommended for percentages and proportions (Sokal & Rholf, 1995; Whitlock & Schluter, 2009), all flight frequencies were arcsin(√x) transformed to approximate normality, which was assessed using a Shapiro-Wilk test. We used one- and two-way ANOVA of the transformed data to determine significant differences among treatments. Pair-wise significant differences among treatments were assessed using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test. For experiments with an overrepresentation of 0’s (no beetles flying), as in the lowest temperature treatment, the data distribution could not be transformed to approximate normality. In all cases, we performed a randomization with 10 000 replicates and report the results of both analyses (Manly, 1991), as well as nonparametric post hoc comparisons. All analyses were performed using the R statistical environment (Ihaka & Gentleman, 1996).

Results

Experiment 1: Food and temperature

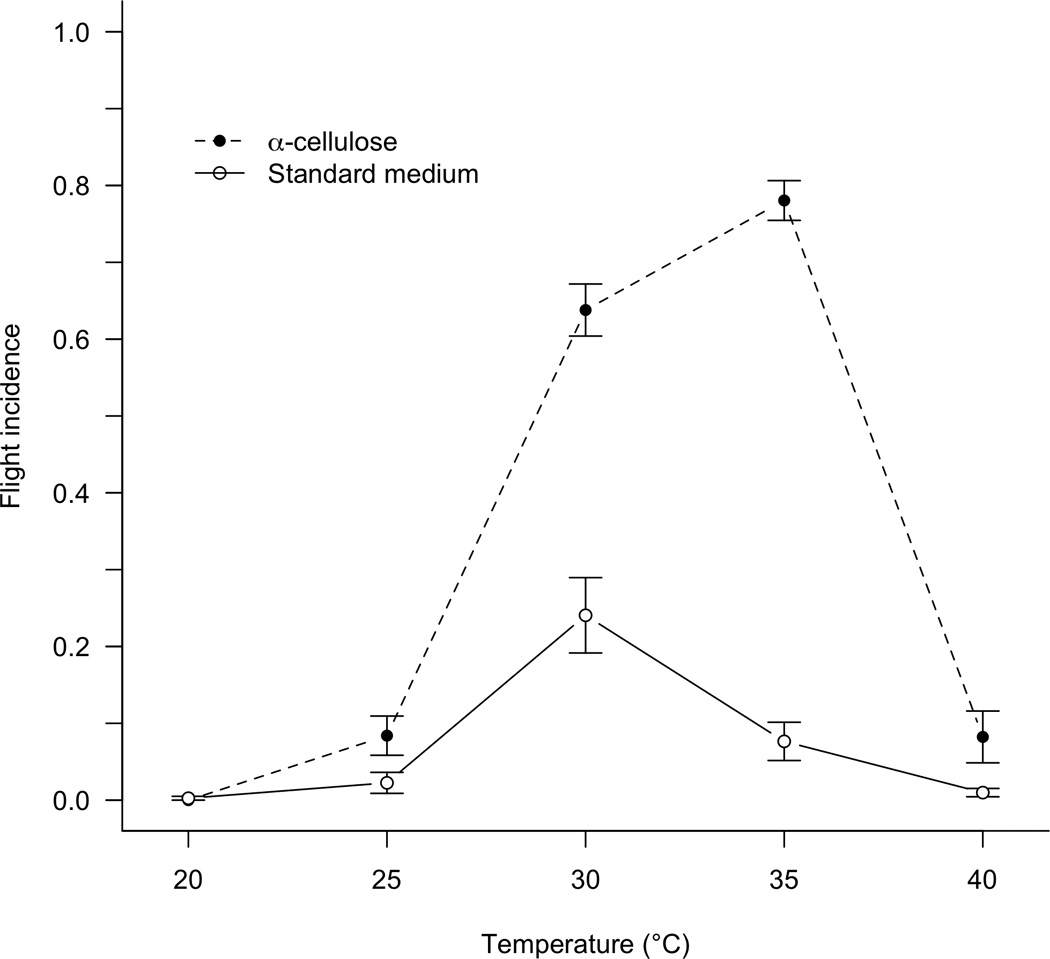

Temperature influenced the incidence of flight (two-way ANOVA: F4,90 = 126.88, P<0.001; Table 1). As expected from the results of Cox et al. (2007), who investigated flight initiation in a range of stored-product pests, little to no flight occurred at temperatures below 25 °C. The presence or absence of food also influenced flight (F1,90 = 167.29, P<0.001), with beetles much more prone to fly under poor nutrient conditions. The interaction between temperature and substrate was also highly significant (F4,90 = 35.55, P<0.001): food-mediated differences in the propensity to fly were largest at intermediate temperatures. Across the experiment, flight rates ranged from 0.0 in the 20 °C treatments to 0.832 (± 0.023, mean ± SEM) in the 35 °C α -cellulose treatment (Figure 2). For two of the five temperature treatments, flight rates were significantly different between medium types, with high flight tendency associated with poorer nutrient conditions. At 30 °C, the difference in flight incidence was 0.418 (two-tailed Mann-Whitney test: U10,10 = 97, z = 3.55, P<0.001), whereas at 35 °C, the difference increased to 0.754 (U10,10 = 100, z = 3.78, P<0.001). There were no nutrient-mediated differences in flight at either the lowest or the highest temperatures (40 °C, difference of 0.089; U10,10 = 55, z = 0.39, P = 0.71). We noticed very few individuals on the surface of the medium in any replicate at 40 °C, suggesting that beetles sought refuge from the heat by burrowing.

Table 1.

Analysis of variance of flight incidence as a function of food availability, temperature treatment, and their interaction

| Source | d.f. | MS | F | P | Prand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium type | 1 | 2.9894 | 167.292 | <0.001 | 0.0001 |

| Temperature | 4 | 2.2672 | 126.878 | <0.001 | 0.0001 |

| Medium*temperature | 4 | 0.6353 | 35.554 | <0.001 | 0.0001 |

| Residuals | 90 | 0.0179 |

Prand refers to probabilities generated from 10000 randomizations (see text)

Figure 2.

Mean (± SEM) proportion of beetles flying over a range of temperatures in the presence of a food source (standard medium) or an indigestible medium (α-cellulose). Each data point is based on ten replicates of 40 adult beetles.

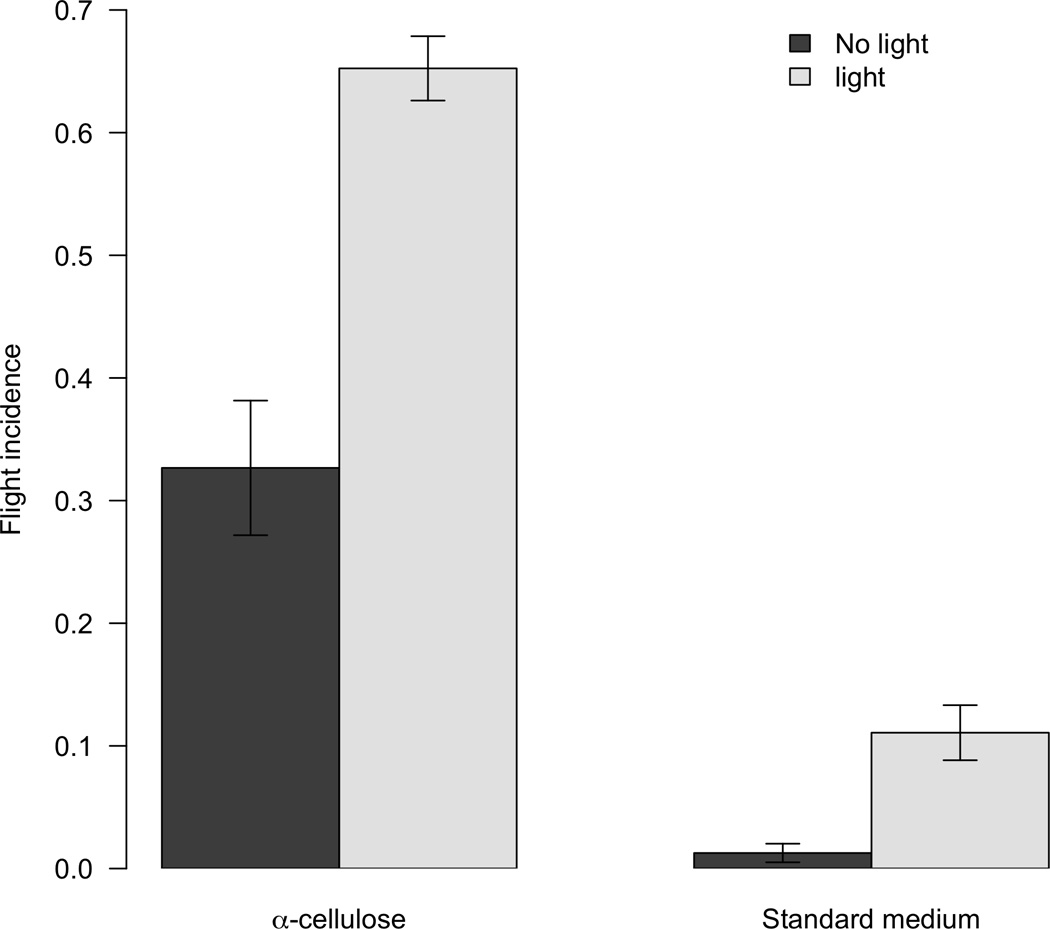

Experiment 2: Food quality and light

We found the main effect of light treatment (two-way ANOVA: F1,35 = 63.87, P<0.001) to be highly significant (Table 2): light stimulates flight. Food type was also a significant factor affecting propensity to fly (F1,35 = 206.71, P<0.001), but there was no significant interaction between light and food (F1,35 = 1.98, P = 0.17).

Table 2.

Analysis of variance of flight incidence as a function of food availability, photoperiod, and their interaction

| Source | d.f. | MS | F | P | Prand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | 1 | 3.1951 | 206.7167 | <0.001 | 0.0001 |

| Light | 1 | 0.9872 | 63.8737 | <0.001 | 0.0001 |

| Medium*light | 1 | 0.0306 | 1.9802 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| Residuals | 35 | 0.00867 |

Prand refers to probabilities generated from 10000 randomizations (see text)

Experiment 3: Food quality

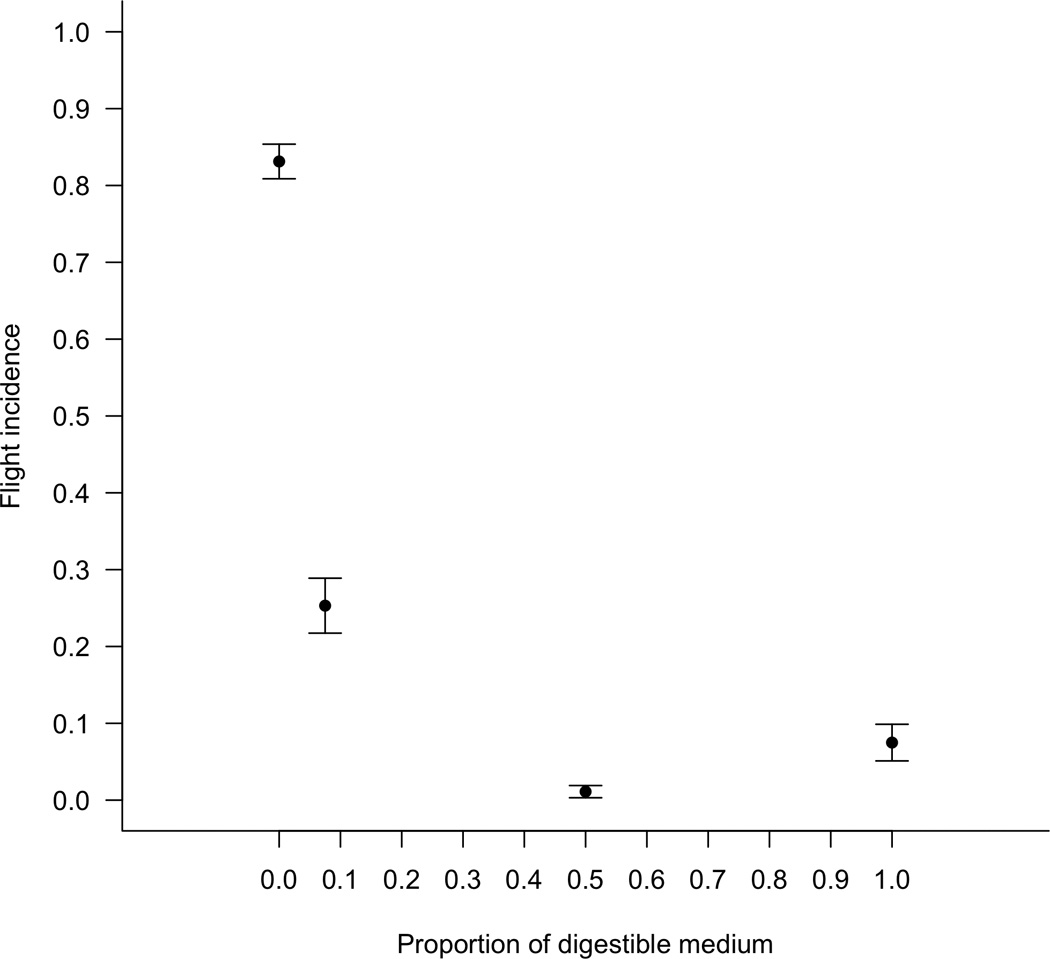

Incidence of flight varied across resource treatments (one-way ANOVA: F3,36 = 138.35, P<0.001). The small increase from 0 to 7.5% in the percentage of edible resource was sufficient to reduce the frequency of individuals attempting flight more than three-fold, from 0.831 (± 0.023, mean ± SEM) to 0.253 (± 0.036). This is an estimated difference in flight propensity of 0.578 (95% confidence interval = 0.672-0.485; Tukey’s HSD: P<0.001; Figure 4). Increasing the percentage of edible resource from 7.5 to 50% resulted in a further two-fold reduction in flight tendency, from 0.253 to 0.011 (± 0.008, mean ± SEM); this is a difference of 0.242 (95% CI = 0.148-0.336; Tukey’s HSD: P<0.001). Increasing the food concentration from 0.5 to 1.0 had no additional significant effect (from 0.011 ± 0.008 to 0.075 ± 0.024, a difference not different from zero; 95% CI = -0.157-0.030; Tukey’s HSD: P = 0.27).

Figure 4.

Mean (± SEM) proportion of beetles flying over a range of digestible medium concentrations.

Experiment 4: Relative humidity and food quality

We found no effect of relative humidity (25 or 75%) on the tendency of beetles to fly (two-way ANOVA: F1,36 = 0.08, P = 0.78). Mean flight incidence, on high-quality food, was low at both the standard humidity (mean flight incidence ± SEM = 0.077 ± 0.024) and the lower humidity (0.087 ± 0.018). As in our other experiments, poor nutrient quality (α-cellulose medium) increased flight incidence: 0.608 ± 0.093 at standard humidity and 0.615 ± 0.091 at low humidity. There was no interaction between food quality and relative humidity as we saw for light.

Discussion

Dispersal can be viewed as consisting of two components: (1) escape from deteriorating local resources, and (2) discovery of or attraction to new or better resource patches. Our report addresses the former component, whereas other researchers have studied the latter (Ahmad et al., 2013a,b). Our data are supportive of the hypothesis that flight is a plastic behavioral response used by T. castaneum, to escape poor local nutrient conditions and begin active dispersal to better resource patches. However, this plastic response is conditional and avoided at both low- and high-temperature extremes. It is generally believed that low temperatures physiologically impair flight in ectothermic insects, although, in some cases, high temperatures (> 40 °C) have also been shown to impair the flight response. For example, in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster Meigen increasing temperature has been used to ‘knock down’ individuals mid-flight (Roberts et al., 2003). At similarly high temperatures, T. castaneum beetles take refuge by burrowing into their food source instead of dispersing.

Tribolium beetles can be reared for several generations in total darkness and, relative to other insects, this species has lost large numbers of genes in the opsin family over its evolution (Richards et al., 2008). Nevertheless, the presence of light is a signal for initiating a flight response: light always provokes a higher flight response than no light. However, we tested only the extremes of constant light and constant darkness. The presence of a light source is not a requirement for survival in T. castaneum as many strains have been reared in constant darkness for > 35 years. However, constant light may be an environmental stressor, inducing a dispersal response greater than would be observed during a standard day-night cycle.

We did not detect an effect on flight over the range from 25 to 75% r.h. The absence of effect is surprising given that a primary function of the coleopteran elytra is protection from mechanical stress and desiccation. Indeed, many desert-adapted tenebrionid beetles are believed to have evolved flightlessness to prevent water loss (Ahearn & Hadley, 1969) and some have completely fused elytra (Zachariassen et al., 1987). Moreover, when beetle elytra have been experimentally perforated, the rate of water loss by transpiration increased 10-fold (Cloudsley-Thompson, 1964). Tribolium beetles do not require a water source; they actively absorb atmospheric water using a kidney-like cryptonephridial organ (Koefoed, 1971). However, in order to initiate and sustain flight, Tribolium beetles must extend the elytra laterally, diminishing their role in mitigating transpiratory water loss. For these reasons, we find it surprising that lowered humidity did not significantly reduce the incidence of flight.

Rates of Tribolium adult dispersal between resources have been predominantly assayed using pheromone traps, and findings show that, at a local scale of less than one to a few km, active migration by flight is common in this species. Campbell & Arbogast (2010) found T. castaneum can be readily caught within a mill, but are captured at lower rates outside relative to inside. Ridley et al. (2011) showed that T. castaneum can be collected 1 km away from grain storages and 1.5 m above the ground when lured by aggregation pheromone. Our results show that T. castaneum has the potential for active dispersal by flight, although our experimental design permitted only very short distance flight. The distances dispersed in nature, which determine gene flow, remain unknown.

Studies of the genetic differentiation among T. castaneum populations (Drury et al., 2009; Semeao et al., 2012; Ridley et al., 2011) have compared populations at vastly greater geographic scales than the studies conducted so far investigating active dispersal by flight. The study by Ridley et al. (2011) investigated the genetic differentiation of individuals collected within a 40-km radius of southern Queensland, Australia. The study of Semeao et al. (2012) assayed the genetic structure of populations collected from across the USA, whereas Drury et al. (2009) assayed differentiation at a global scale, using wild cultures recently collected as well as cultures maintained over 25 years in laboratory husbandry. Together, these studies found a weak trend toward isolation by distance with overall FST increasing with the geographic scale of the study. At a local scale of a few km, the average estimate of FST is 0.024 (Ridley et al., 2011), at a continental scale, the mean estimate is 0.082 (Semeao et al., 2012), whereas at a global scale, estimates of FST approach 0.180 (Drury et al., 2009). However, within the scale of any single study, the pervasive finding is a lack of isolation by distance (IBD), meaning that populations nearer to one another are genetically not more similar than populations further apart. The combination of genetic evidence in support of highly genetically differentiated population but an absence of IBD suggests a pattern of short distance dispersal mediated by active flight among adjacent or nearby demes, combined with larger-scale dispersal via anthropogenic trafficking, which tends to shuffle the expected pattern of IBD. Thus, although T. castaneum beetles incorporate local environmental cues to initiate dispersal by flight, the proportional influence of human-mediated dispersal on the large-scale genetic population structure of this species appears to exceed that of active migration by flight.

Figure 3.

Mean (± SEM) proportion of beetles flying in the presence of a food source (standard medium) or an indigestible medium (α-cellulose) and in the presence/absence of a light source.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge NSF-IGERT grant DGE-0504627 for supporting DWD and the support of NIH grant 5R01GM65414-4 to MJW.

References

- Ahearn GA, Hadley NF. Effects of temperature and humidity on water loss in 2 10 desert tenebrionid beetles, Eleodes armata and Cryptoglossa verrucosa. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1969;30:739–749. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad F, Daglish GJ, Ridley AW, Burrill PR, Walter GH. Short-range resource location by Tribolium castaneum Herbst (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) demonstrates a strong preference for fungus infected cotton seed. Journal of Stored Products Research. 2013a;52:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad F, Ridley AW, Daglish GJ, Burrill PR, Walter GH. Response of Tribolium castaneum and Rhyzopertha dominica to various resources, near and far from grain storage. Journal of Applied Entomology. 2013b;137:773–781. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler DE, Benton TG. Causes and consequences of animal dispersal strategies: relating individual behaviour to spatial dynamics. Biological Reviews. 2005;80:205–225. doi: 10.1017/s1464793104006645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JF, Arbogast RT. Stored-product insects in a flour mill: population dynamics and response to fumigation treatments. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 2004;112:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JF, Toews MD, Arthur FH, Arbogast RT. Long-term monitoring of Tribolium castaneum in two flour mills: seasonal patterns and impact of fumigation. Journal of Economic Entomology. 2010;103:991–1001. doi: 10.1603/ec09347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloudsley-Thompson JL. On the function of the subelytral cavity in desert Tenebrionidae (Col.) Entomologist's Monthly Magazine. 1964;100:148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Clobert J, Baguette M, Benton TG, Bullock JM, Ducatez S. Dispersal Ecology and Evolution. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cox PD, Wakefield ME, Jacob TA. The effects of temperature on flight initiation in a range of moths, beetles and parasitoids associated with stored products. Journal of Stored Product Research. 2007;43:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Demuth JP, Wade MJ. Population differentiation in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. I. Genetic architecture. Evolution. 2007a;61:494–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuth JP, Wade MJ. Population differentiation in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. II. Haldane's rule and incipient speciation. Evolution. 2007b;61:694–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury DW, Siniard AL, Wade MJ. Genetic differentiation among wild populations of Tribolium castaneum estimated using microsatellite markers. Journal of Heredity. 2009;100:732–741. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury DW, Wade MJ. Genetic variation and co-variation for fitness between intra-population and inter-population backgrounds in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2011;24:168–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihaka R, Gentleman R. R: A language for data analysis and graphics. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 1996;5:299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Koefoed BM. Ultrastructure of cryptonephridial system in meal worm Tenebrio molitor. Zeitschrift für Zellforschung und mikroskopische Anatomie. 1971;116:487–501. doi: 10.1007/BF00335054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Gaines MS. Evolution of dispersal: theoretical models and empirical tests using birds and mammals. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1990;21:449–480. [Google Scholar]

- Levins R. Extinction. In: Gerstenhaber M, editor. Some Mathematical Problems in Biology. Providence, RI, USA: American Mathematical Society; 1970. pp. 77–107. [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Gibbs RA, Weinstock GM, Brown SJ, Denell R, et al. The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum. Nature. 2008;452:949–955. doi: 10.1038/nature06784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley AW, Hereward JP, Daglish GJ, Raghu S, Collins PJ, Walter GH. The spatiotemporal dynamics of Tribolium castaneum (Herbst): adult flight and gene flow. Molecular Ecology. 2011;20:1635–1646. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SP, Marden JH, Feder ME. Dropping like flies: environmentally induced impairment and protection of locomotor performance in adult Drosophila melanogaster. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 2003;76:615–621. doi: 10.1086/376922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semeao AA, Campbell JF, Beeman RW, Whitworth RJ, Sloderbeck PE, Lorenzen MD. Genetic structure of Tribolium castaneum populations in mills. Environmental Entomology. 2012;41(1):188–199. doi: 10.1603/EN11207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M. Gene flow and selection in a cline. Genetics. 1973;75:733–756. doi: 10.1093/genetics/75.4.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M, Barton NH. A comparison of three indirect methods for estimating average levels of gene flow. Evolution. 1989;43:1349–1368. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Valen L. Group selection and the evolution of dispersal. Evolution. 1971:591–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1971.tb01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade MJ, Goodnight CJ. The theories of Fisher and Wright in the context of metapopulations: When nature does many small experiments. Evolution. 1998;52:1537–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1998.tb02235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade MJ, McCauley DE. Extinction and recolonization: their effects on the genetic differentiation of local populations. Evolution. 1988;42:995–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1988.tb02518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. Evolution in Mendelian populations. Genetics. 1931;16:97–159. doi: 10.1093/genetics/16.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariassen KE, Andersen J, Maloiy GMO, Kamau JMZ. Transpiratory water loss and metabolism of beetles from arid areas in East Africa. Comarative. Biochemistry and Physiology. 1987;86A:403–408. [Google Scholar]