Highlights

-

•

Calvarial cavernous hemangiomas are benign tumors.

-

•

These tumors tend to involve the outer table of the skull.

-

•

More extensive involvement of the inner table and extradural space is very unusual.

-

•

We present a case of a huge frontal cavernoma with intradural extension.

-

•

Our case highlights the possibility of an aggressive course of this rare benign pathology.

Keywords: Cavernous hemangioma, Bone tumors, Intradural extension, Skull tumors

Abstract

Introduction

Cavernous hemangioma of the skull is a rare pathological diagnosis, accounting for 0.2% of bone tumors and 7% of skull tumors. Usually calvarial bone cavernous hemangioma are associated with a benign clinical course and, despite their enlargement and subsequent erosion of the surrounding bone, the inner table of the skull remains intact and the lesion is completely extracranial.

Presentation of a case

The authors present the unique case of a huge left frontal bone cavernous malformation with intradural extension and brain compression determining a right hemiparesis.

Discussion

Calvarial cavernous hemangiomas are benign tumors. They arise from vessels in the diploic space and tend to involve the outer table of the skull with relative sparing of the inner table. More extensive involvement of the inner table and extradural space is very unusual and few cases are reported in literature. To the best of our knowledge, intradural invasion of calvarial hemangioma has not been previously reported.

Conclusion

Our case highlights the possibility of an aggressive course of this rare benign pathology.

1. Introduction

Cavernous hemangioma of the skull is a rare pathological diagnosis, accounting for 0.2% of bone tumors and 7% of skull tumors [1]. They can occur at any age, but are commonly found in females who are in the fourth or fifth decades of life [2]. These cranial lesions are usually solitary and most often found in frontal and parietal bones, but the lesion could occur in almost any skull region (occipital, sphenoidal, clival and ethmoidal regions) [3].

Calvarial cavernous hemangiomas arise from vessels in the diploic space and are supplied by the branches of the external carotid artery. The middle meningeal and superficial temporal arteries are the main sources of blood supply [4].

Calvarial hemangiomas tend to involve the outer table of the skull and the diploe, with relative sparing of the inner table [5]. More extensive involvement of the inner table and extradural space is very unusual [6].

The authors present the unusual case of a frontal bone cavernous malformation with intradural extension. To the best of our knowledge, intradural invasion of calvarial hemangioma has not been previously reported. This case highlights the possibility of an aggressive course of this rare benign pathology.

2. Presentation of a case

2.1. History and examination

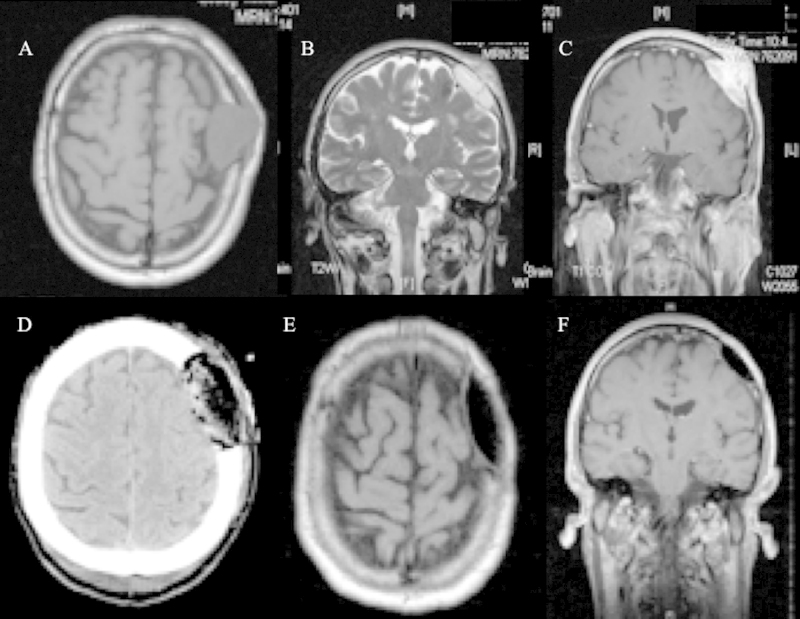

A 60-year-old man with a left frontal mass was admitted to our Department after 2 week of increasing headaches, nausea, right arm weakness with poor coordination, and difficulty walking because of a “clumsy” right leg. A clinical history of uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes mellitus and prostatic hypertrophy is reported. The patient denied previous trauma. The mass had been present for at least 6 months and had shown gradual growth. Physical examination revealed an approximately four cm in diameter palpable and non-tender mass in the left frontal region. Neurologic examination revealed a patient with right hemiparesis. The patient had 3/5 strength in the right upper and lower extremities. The deep tendon reflexes were slightly increased on the right side. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large extra-axial lesion with epicenter in left frontal bone, predominantly solid (Fig. 1A–C). It measured 4 cm in its largest dimension and approximately 3 cm in depth. There was discontinuity in the cortical surfaces of both the inner and outer tables of the skull with intracranial invasion. The intracranial component of the lesion compressed the left frontal lobe. The extracranial component was also seen in the left frontal scalp region. The lesion was predominantly isointense on T1-weighted images (Fig. 1A) and hyperintense on T2-weighted images (Fig. 1B). After the administration of Gadolinium, there was heterogeneous enhancement of the mass (Fig. 1C). A surgical plan was made under the assumption that this lesion was a meningioma.

Fig. 1.

(A–C) Pre-operative MRI imaging revealed a large extra-axial lesion with epicenter in left frontal bone and intradural invasion, predominantly isointense on axial T1-weighted image (A), hyperintense on coronal T2 weighted image (B) and with contrast enhancement (C). (D) Postoperative CT scan showed a good restoration of the cranial deformity. (E, F) Follow-up MRI axial and coronal T1 weighted images with Gadolinium demonstrated no evidence of recurrence.

2.2. Surgical treatment

During surgery, the patient was positioned in the supine decubitus position and head was fixed in 3-pin head holder and rotated to the right. A question mark-shaped incision was given just behind the posterior margin of the mass and the skin flap was raised subgaleally. Soft, reddish-brown, highly vascular lesion was seen in the left frontal region with erosion of the outer table. The whole extracranial portion was removed. Then we proceed to remove the intracranial portion of the tumor. After placing a burr hole behind the lesion, a circular craniotomy of about 6 cm was performed around the lesion. At this point, the tumor was found to be not completely extradural. In fact, the lesion eroded the dural mater with invasion of intradural compartment. The lesion is then coagulated and followed up to identify the opening of the dural mater. A defect of the dural plane caused by the tumor has been used to remove the residual intradural part of the lesion. At this stage, the lesion did not have arterious pial afferents anymore. The pia mater was thick and whitish. After total removal of the lesion, a polymethyl methacrylate cranioplasty was performed.

2.3. Postoperative course

Postoperatively, the patient presented immediate relief of symptoms, and results of his neurological examination were normal, with complete recovery from his previous motor weakness. Postoperative CT scan showed a good restoration of the cranial deformity (Fig. 1D).

He was discharged home on postoperative Day 3 after an uneventful course. The patient has been followed up for 48 months post-operatively and remains asymptomatic with an excellent cranial contour and no evidence of recurrence on serial MRI imaging (Fig. 1E and F).

2.4. Pathological findings

Macroscopically, the pathologic bone presented a huge purple-red blush mass that eroded completely the inner table. The dura appeared eroded throughout its thickness by a bluish red spongy lesion.

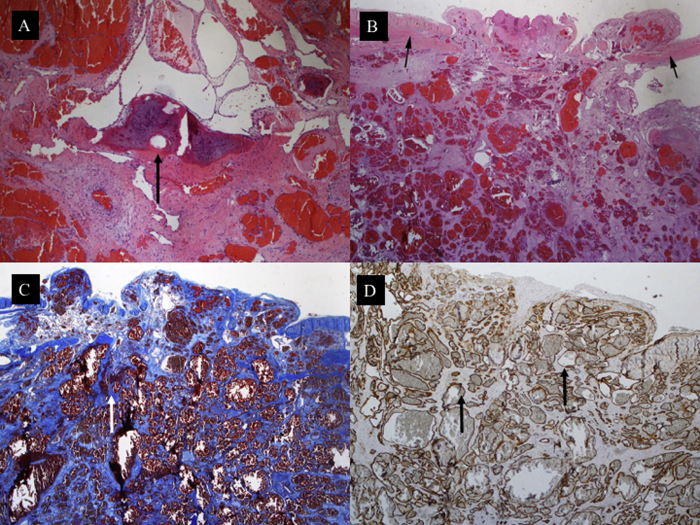

Histological examination of the bone revealed a capillary hemangioma consisting of thin-walled blood vessels, some of which were distended with blood (Fig. 2A). Microscopic examination of the dura showed pathological vessels perforating the dura mater (Fig. 2B). The vessels were separated by scarce connective tissue intensely blue stained (Fig. 2C). Immunohistochemical staining with CD34 highlights the contours of the malformed vessels (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

A Cavernous angioma made of a proliferation of thin-walled vessels with dilated lumina. The vessels are seen substituting the bone tissue of the cranial vault (black arrow). H&E∗ × 100. (B) The thin-walled vessels are seen perforating the dura (black arrows). H&E∗ × 100. (C) The vessels are separated by scarce connective tissue intensely blue stained (white arrow). Picro Mallory ×100. (D) Immunohistochemical staining with CD34 highlights the contours of the malformed vessels (black arrows). ×100.

∗ H&E: haematoxylin and eosin stain.

The present work has been reported in line with the CARE criteria [7].

3. Discussion

Hemangiomas are benign tumors of blood vessels and are histologically classified as cavernous and capillary [8]. Most of the calvarial hemangiomas are of the cavernous type. The cavernous type is composed by a group of large, dilated blood vessels separated by fibrous tissue. On the contrary, vertebral hemangiomas are most frequently of the capillary type that lacks fibrous septa and have smaller vascular lumen.

Calvarial cavernous hemangiomas arise from vessels in the diploic space and tend to involve the outer table of the skull with relative sparing of the inner table. In fact, despite their enlargement and subsequent erosion of the surrounding bone, the inner table remains intact [5]. More extensive involvement of the inner table and extradural space is very unusual [6]. Some authors reported the grow of intraosseous cavernous hemangiomas into the internal skull with dural sparing [6]. Uemura et al. described a patient with a calvarial cavernous hemangioma who presented with an epidural haemorrhage in which the inner table was completely eroded and the lesion was in direct contact with intact dura mater [9]. Khanam et al. [2] reported a right sphenoid wing hemangioma with involvement of adjacent dura, which was also resected and sent for pathologic analysis. Finally, Gottfried et al. [10] presented a case of a 50-year-old man in whom a symptomatic subdural hematoma resulting from a cavernous hemangioma of the calvaria had hemorrhaged and eroded through the inner table of the skull and dura mater. During surgery, the authors found that the dura mater was eroded all the way through in the area immediately subjacent to the skull cavernous hemangioma, making the subdural space contiguous with the calvarial lesion.

Nevertheless, in all of these cases a clear extension of the tumor into the subdural space was not documented [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13].

The peculiarity of our case consists in the complete erosion of dural plane with invasion of subdural space by the skull cavernous hemangioma. During surgery, after durotomy, the lesion did not present pial vascular afferents and both the arachnoid and the pia mater appeared thickened and whitish, but intact. To the best of our knowledge, this extensive intradural invasion of calvarial hemangioma has not been previously reported.

These lesions are usually small and asymptomatic but can cause a variety of symptoms depending on their location [8]. Patients most often report a slowly enlarging mass that may become tender, but most often is not [11]. Headaches are reported to occur as the lesion expands. Neurological symptoms can occur especially hearing loss, pulsatile tinnitus, and facial paralysis when the petrous or sphenoid bones are involved [12].

Another peculiarity of our patient was the presence of hemiparesis related the brain compression. In fact, the presence of motor deficit was not previously described in frontal bone cavernous hemangioma.

The classic appearance of a hemangioma on radiographs are a “honeycomb” pattern, denoting rounded area of rarefaction [3]. This pattern can be also appreciated on bone windows of a CT scan. Enhancement with contrast material is intense on both CT and MRI. On MRI imaging, these lesions show an intermediate to high T1 signal intensity and a high, hetereogeneousT2 signal intensity [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6].

Benign lesions with similar findings include aneurysmal bone cyst, osteoma, giant cell tumor or fibrous dysplasia. More aggressive lesions include meningioma, multiple myeloma, metastatic disease and osteosarcomas [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. Therefore, classic MRI features may not be sufficient to distinguish the different pathologic entities. Sometimes, the classic radiographic appearances are not evident. Consequently, the diagnosis is established in most of the cases only after surgery and biopsy [1], [2], [3], [4], [5].

The standard therapy for cranial hemangiomas is the surgical resection with or without cranioplasty [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. To prevent recurrence, removal of the lesion plus a 1-cm-wide margin of uninvolved bone is always recommended [5]. This method allows the removal of the tumor intact, obviating the risk of significant bleeding because the sinusoids are undisturbed. In our case, after removal of whole extracranial, intraosseous and extradural components of the lesion in one piece, we proceed to the excision of the infiltrated dura mater and intradural part of the tumor.

Reconstruction of the defect with methylmethacrylate quite often yields favorable cosmetic results [5], as seen in our patients. Before cranioplasty, in this case we perfomerd a duroplasty with bovine pericardium.

Alternative therapies used for the treatment of cranial hemangiomas include surgical percutaneous embolization, curettage, and radiotherapy [13]. Curettage is associated with an increased risk of haemorrhage and recurrence, since residual tumor can be left behind. Radiotherapy, typically used when resection is not possible, has been shown to decrease the size of hemangiomas, but not reduce the risk of haemorrhage and is associated with radiation-induced carcinoma [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13].

4. Conclusion

The authors present the unusual case of a huge frontal bone cavernous malformation with intradural extension and brain compression determining a hemiparesis. To the best of our knowledge, intradural extension of calvarial hemangioma has not been previously reported. On the basis of this report, neurosurgeon must be aware on the possibility of an aggressive course of this rare benign pathology

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Funding

No involvement of any funding to be mentioned.

Ethical approval

Approval obtained from local research committee. Approval was given by consenting the patient.

Consent

We obtained written informed consent from subject of this study.

Author contribution

Davide Nasi: Author,

Lucia di Somma: Co-author,

Maurizio Iacoangeli: Co-author–literature review,

Valentina Liverotti: Data collection,

Antonio Zizzi: Pahtological findings collection and interpretation,

Mauro Dobran: Discussion of the case,

Maurizio Gladi: Discussion of the case,

Massimo Scerrati: Data analysis or interpretation–literature review.

Guarantor

Davide Nasi and Maurizio Iacoangeli.

References

- 1.Haeren R.H., Dings J., Hoeberigs M.C., Riedl R.G., Rijkers K. Posttraumatic skull hemangioma: case report. J. Neurosurg. 2012;117(6):1082–1088. doi: 10.3171/2012.8.JNS112141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khanam H., Lipper M.H., Wolff C.L., Lopes M.B. Calvarila hemangiomas: report of two cases and review of the literature. Surg. Neurol. 2001;55:63–67. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(00)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heckl S., Aschoff A., Kunze S. Cavernomas of the skull: review of the literature 1975–2000. Neurosurg. Rev. 2002;25:56–67. doi: 10.1007/s101430100180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma S.K., Singh P.K., Garg K., Satyarthee G.D., Sharma M.C., Singh M. Giant calvarial cavernous hemangioma. J. Pediatr. Neurosci. 2015;10(1):41–44. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.154337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naama O., Gazzaz M., Akhadar A., Belhachmi A., Asri A., Elmostarchid B. Cavernous hemangioma of the skull: 3 case reports. Surg. Neurol. 2008;70:654–659. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu P., Lan S., Liang Y., Xiao Q. Multiple cavernous hemangiomas of the skull with dural tail sign: a case report and literature review. BMC Neurol. 2013;25(13):155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gagnier J., Kienle G., Altman D.G., Moher D., Sox H., Riley D.S., The CARE groupy The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013;67(1):46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonioli D.A., Carter D., Mills S.E., Oberman H.A., Sternberg S.S. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Raven Press; New York: 1994. p. 301. (Diagnostic Surgical Pathology). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uemura K., Takahashi S., Sonobe M., Oyama K., Akai T., Sugita K. Intradiploic haemagioma associated with epidural haematoma. Neuroradiology. 1996;38:456–457. doi: 10.1007/BF00607275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottfried O.N., Gluf W.M., Schmidt M.H. Cavernous hemangioma of the skull presenting with subdural hematoma: case report. Neurosurg. Focus. 2004;15:17. doi: 10.3171/foc.2004.17.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haeren R.H., Dings J., Hoeberigs M.C., Riedl R.G., Rijkers K. Posttraumatic skull hemangioma: case report. J. Neurosurg. 2012;117(6):1082–1088. doi: 10.3171/2012.8.JNS112141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glasscock M.E., III, Smith P.G., Schwaber M.K., Nissen A.J. Clinical aspects of osseous hemangiomas of the skull base. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:869–873. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198407000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nasrallah I.M., Hayek R., Duhaime A.C., Stotland M.A., Mamourian A.C. Cavernous hemangioma of the skull: surgical treatment without craniectomy. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2009;4(6):575–579. doi: 10.3171/2009.7.PEDS09105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]