Abstract

Small vessel disease encompasses lacunar stroke, white matter hyperintensities, lacunes and microbleeds. It causes a quarter of all ischemic strokes, is the commonest cause of vascular dementia, and the cause is incompletely understood. Vascular prophylaxis, as appropriate for large artery disease and cardioembolism, includes antithrombotics, and blood pressure and lipid lowering; however, these strategies may not be effective for small vessel disease, or are already used routinely so precluding further detailed study. Further, intensive antiplatelet therapy is known to be hazardous in small vessel disease through enhanced bleeding. Whether acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, which delay the progression of Alzheimer's dementia, are relevant in small vessel disease remains unclear. Potential prophylactic and treatment strategies might be those that target brain microvascular endothelium and the blood brain barrier, microvascular function and neuroinflammation. Potential interventions include endothelin antagonists, neurotrophins, nitric oxide donors and phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐gamma agonists, and prostacyclin mimics and phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitors. Several drugs that have relevant properties are licensed for other disorders, offering the possibility of drug repurposing. Others are in development. Since influencing multiple targets may be most effective, using multiple agents and/or those that have multiple effects may be preferable. We focus on potential small vessel disease mechanistic targets, summarize drugs that have relevant actions, and review data available from randomized trials on their actions and on the available evidence for their use in lacunar stroke.

Keywords: antithrombotics, blood brain barrier, blood pressure lowering, cyclic nucleotide inhibitors, nitric oxide, prostacyclin

Introduction

Small vessel disease (SVD) causes a quarter of all ischemic strokes (lacunar stroke) 1 and is the commonest cause of vascular dementia. The cause of SVD, which also includes white matter hyperintensities (WMH), lacunes and microbleeds 2, 3, is, as yet, incompletely understood. Although conventional vascular prophylaxis, such as intensive antiplatelet therapy, may not be effective for small vessel disease, there are many other therapeutic targets 4, and drugs to test in clinical trials. Here we review all available drugs with actions that are relevant to suspected mechanisms of intrinsic SVD and all available evidence on use of any of these drugs to prevent lacunar stroke and SVD.

Background

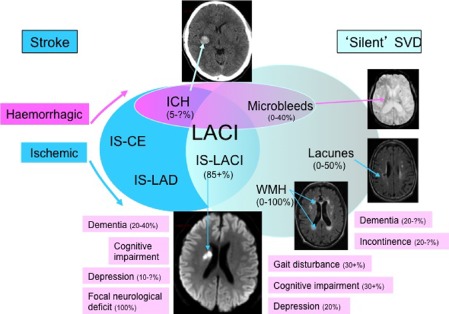

A quarter of ischemic strokes (≈30 000 per year in the UK) are lacunar or small subcortical in type (Fig. 1) 1. These usually cause mild to moderate neurological deficit with low early mortality, but can be physically disabling and have a high long‐term risk of recurrence and cognitive impairment 5, 6. Lacunar stroke is associated with subclinical abnormalities that contribute to the burden of brain damage causing insidious physical and cognitive deficits and vascular dementia 7, and increasing the societal impact beyond that expected from the small size of the infarct alone 3. These abnormalities are easily detected on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain imaging, and include lacunar or small subcortical infarction, lacunes, white matter hyperintensities (WMH) 8 and microbleeds 9. Although they may present after a clinically‐overt event, most lacunes 10, subcortical grey or white matter hyperintensities and microbleeds develop ‘silently’. When numerous, all three are associated with cognitive impairment, doubling the risk of dementia and trebling the risk of stroke 11, 12. Together with lacunar stroke, these features are collectively known as cerebral small vessel disease (SVD; Fig. 1) 2. Small haemorrhages can also present with lacunar stroke 13; and an as yet unknown proportion of large haemorrhages are also now recognized to have SVD as the major underlying pathology (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Venn diagram showing relationship between small vessel disease and other forms of stroke. The embedded neuroimages show, clockwise from the top: intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH), microbleeds, lacunes (‘lakes’ of cerebrospinal fluid), white matter hyperintensities (WMH), and an acute lacunar infarct (LACI). Percentages relate to SVD etiologies and complications and are approximate: ‘?’ indicates a lack of data.

Properties of pharmacological agents needed for SVD

The slow development of SVD and its chronic nature suggest that any intervention for its prevention or treatment will need to be given long‐term. The high prevalence of SVD (e.g. a quarter of all ischemic strokes; 45% of all age‐related dementias; WMH present in 17+% at age 70 + 11, 14) suggests that any long‐term intervention will need to come at modest financial cost to both individuals and society. Extrapolating from these two observations, any effective intervention will have to be administered as an oral, transdermal or nasal preparation, or possibly via a long‐acting injectable. Since the target population will include many older people who may be on multiple drugs for other indications (e.g. vascular prophylaxis, arthritis, gastro‐oesophageal reflux, laxatives), an intervention with limited drug interactions and once (or twice) daily administration will be preferable. The growing number of very elderly people makes it imperative that patients aged over 85 are included in future trials – few have been included in stroke prevention trials to date.

Clinical targets include reducing first or recurrent stroke, and preventing cognitive decline and physical disabilities such as impaired balance or gait, or neuropsychological symptoms 15. Imaging targets include preventing the development of new lacunes, microbleeds and brain atrophy, and delaying the worsening of WMH. It is important to use accurate lesion quantification methods and in particular to avoid confounding of imaging measurements by, for example, including a recurrent cortical or large subcortical infarct in WMH volume which would artificially inflate the apparent WMH burden. Additional targets for detecting reduced brain damage include checking if treatments reduce global brain 16 or focal regional cortical or brainstem atrophy 17, 18 that occur secondary to WMH and incident lacunar ischemic strokes respectively. Importantly, the effectiveness of an agent in the acute situation does not mean that it will be effective in long‐term prevention; adaptation may be a problem with some agents when given long term or expose the patient to increased risk.

Potential pharmacological interventions for preventing or treating SVD

Supplement Table S1 highlights the potential mechanisms by which multimodal drugs might work in patients with SVD, including details of potential mechanisms for which there is current evidence and relevant references. Note that many drugs have little lacunar‐specific data but where available this is highlighted. A list of relevant completed trials where either patients with SVD were included, or where SVD was an outcome, is given in Supplement Table S2. Relevant systematic reviews of drugs that may be of value in SVD are listed in Supplement Table S3. Supplement Table S4 lists ongoing trials.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and other anti‐dementia drugs

Anti‐cholinesterase inhibitors (AChEI) prevent the breakdown of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter, by acetylcholinesterase. Four drugs are licensed for treating mild‐to‐moderate Alzheimer's Disease: tacrine, rivastigmine, galantamine and donepezil; a fifth licensed drug, memantine, is a non‐competitive NMDA receptor antagonist. Short‐term trials of these drugs in vascular cognitive impairment and vascular dementia have given mixed results but small effects have been reported for donepezil, memantine and galantamine (Supplement Table S3). Although some patients with SVD will, inevitably, have been included in these trials, the proportion is unclear. No relevant data were found for rivastigmine (Supplement Table S3).

The relevance of AChEI to the prevention or treatment of SVD is probably limited (see mechanisms listed in Supplemental Table S1): existing trials were short‐term (6 months) treatment rather than prevention studies, the observed effect on cognition assessed using the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS‐Cog) was small (Supplement Table S2) and of questionable clinical relevance (ADAS‐Cog ≥ 4 is considered worthwhile 19), benefit on the ADAS‐Cog is of limited relevance to VaD since it does not adequately measure executive function (the Vascular Dementia Assessment Scale, VaDAS, addresses this deficiency but relevant data for AChEI are not available), and the drugs are not disease‐modifying for Alzheimer's Disease (and similarly are unlikely to be post‐lacunar stroke).

Anticoagulation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a major risk factor for both stroke, and for cognitive decline and dementia. Although antiplatelets are ineffective for preventing stroke in patients with AF, warfarin (an antagonist of vitamin K1 recycling) reduced recurrence by two‐thirds in the ‘European Atrial Fibrillation Trial’ (Supplement Table S2). In view of the need for regular monitoring and numerous drug and food interactions, novel fixed dose anticoagulants have been developed (apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban) and these are as effective (and potentially more effective) than warfarin at preventing stroke, and recurrent stroke (subtype unspecified), in patients with AF (Supplement Table S2). Although cardioembolism is an infrequent cause of lacunar ischemic stroke 20, patients with cardioembolic sources who present with lacunar ischemic stroke should have secondary prevention treatment as any other cardioembolic stroke. Apixaban is also more effective than aspirin in AF. Unfortunately, none of these modern trials reported results for outcomes in the subgroup of patients with SVD, or on the effect of treatment on cognition or SVD as an outcome.

In view of the beneficial effect of oral anticoagulation in AF, warfarin has also been tested in patients with prior stroke (including some with a small subcortical infarct) who are in sinus rhythm. With conventional anticoagulation (INR 2–3), warfarin was not superior to aspirin (Supplement Table S2). In the SPIRIT trial, high dose warfarin (INR 3.0–4.5) was associated, as compared with aspirin, with increased intracerebral haemorrhage, particularly in patients with many WMH (Supplement Table S2).

Anti‐inflammatory agents

Steroids and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the two archetypal classes of anti‐inflammatory agents; steroids are not further discussed here since long‐term use would probably cause more problems (e.g. hypertension, hyperglycemia, osteoporosis) than they might solve by attenuating SVD. NSAIDs such as aspirin, ibuprofen and naproxen inhibit the formation of inflammatory‐causing prostaglandins through inhibiting the activity of cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX2, Supplement Table S1), as well as inhibiting COX1 which leads to gastrointestinal bleeding. Selective COX2‐inhibitors (coxibs) are not relevant here since they increase vascular events in at‐risk individuals.

Many other drugs classes have anti‐inflammatory effects manifest as reductions in the activity of the cellular components of inflammation (white cell activation, typically neutrophils and monocytes, and white cell‐platelet conjugates), and/or soluble biomarkers (such as CRP, cytokines and interleukins). Example agents include nitric oxide (NO) donors, prostacyclin (PGI2), phosphodiesterase (PDE)‐inhibitors, and statins (as discussed below and in Supplement Table S1).

Antiplatelet agents

Commonly used oral antiplatelet agents after stroke include aspirin (typically 50 mg to 81 mg daily), cilostazol, clopidogrel, dipyridamole, and triflusal. Practically, aspirin and clopidogrel can be considered to have moderately potent antiplatelet effects, and cilostazol, dipyridamole and triflusal to have mild antiplatelet activity; very potent oral antiplatelet agents such as lotrafiban, a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonist, are not used because of an increased risk of death and bleeding 21. Although clopidogrel is selective as an antiplatelet agent, the other drugs have extra‐platelet effects, including reducing endothelial cell dysfunction, and white cell and smooth muscle cell activity (Supplement Table S1, Fig. S2). All have RCT data to support their efficacy in preventing recurrence after any ischemic stroke (and TIA, for some) (Supplement Table S3). In most of the above trials, differentiation of patients with lacunar stroke from other subtypes was not done, or the results were not reported separately.

The combination of two antiplatelet drugs vs. mono antiplatelet therapy has also been studied although the data vary between acute and chronic administration after stroke. In acute stroke, short‐term dual therapy is superior to mono therapy such that the reduction in early stroke recurrence exceeds any increase in major bleeding, as seen in both a meta‐analysis and subsequent individual trial (Supplement Tables S2 and 3). However, the picture is mixed for chronic administration after stroke; whilst the combination of aspirin and dipyridamole is superior to either agent alone (Supplement Table S3), combined aspirin and clopidogrel are not superior to monotherapy since excess bleeding risk matches or outweighs any reduction in recurrence (Supplement Table S2) 22, particularly in patients with lacunar stroke (Bath P, European Stroke Conference, May 2012).

Across a wider and mixed group of 90 934 patients with ischemic heart disease or stroke (either receiving short‐ or long‐term treatment), the adverse risk‐benefit ratio of combined aspirin and clopidogrel vs. aspirin was confirmed in a meta‐analysis of RCTs except in lacunar stroke where any reduction in MI with dual antiplatelet therapy was offset by an increase in haemorrhage and death 23. Only one completed trial has tested chronic triple antiplatelet therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel and dipyridamole) and this was stopped early because the comparator, aspirin alone, was considered unethical to give beyond 2006 (Supplement Table S2); nevertheless, in this small population of patients, mostly with lacunar stroke (71%), chronic triple antiplatelet therapy was associated with increased bleeding.

Importantly, all the above trials recruited a mixed group of patients including both lacunar and non‐lacunar stroke and most did not characterize patients at baseline as one or the other. Only one RCT, the ‘Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Stroke’ (SPS3) study (Supplement Table S2), has tested antiplatelet drugs specifically in patients with lacunar stroke. (SPS also assessed intensity of blood pressure lowering in a factorial design [Supplement Table S2].) SPS3 compared long‐term therapy with combined aspirin and clopidogrel vs. aspirin alone in 3020 patients with MRI DWI‐proven lacunar stroke; dual therapy caused excess haemorrhage and death and the trial was stopped prematurely. Since patients with lacunar stroke would be expected to have less atheroma 5 it is perhaps unsurprising, in retrospect, that ischemic vascular events were unchanged in the face of an increase in bleeding. A similar increase in haemorrhage was also seen in the subgroup of patients with prior stroke (47% with SVD) randomized to vorapaxar vs. placebo in the TRA‐2P trial, where vorapaxar was given on top of existing antiplatelet therapy, i.e. amounting to dual therapy 24. The small subgroup in whom lacunar ischemic stroke occurs above a carotid atheromatous stenosis 20, or who have intracranial large artery or branch artery atheroma might be expected to benefit from antiplatelet drugs although such patients must have been included in SPS3 (which did not show benefit) and it is difficult to distinguish atheromatous from intrinsic small vessel lacunar ischemic stroke at present. The lack of benefit of antiplatelet agents in lacunar stroke in trials is supported by laboratory studies where particulate hemostasis, i. e. that based on platelets, is not abnormal in SVD 25, 26. The effects of antiplatelets on the other types of SVD – WMH, lacunes, micro‐bleeds – have not been studied in detail.

Blood brain barrier (BBB) modulation

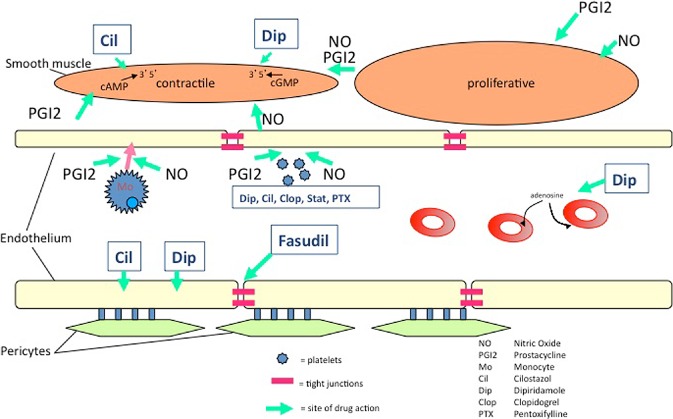

BBB function is damaged by metabolic derangement such as hyperglycemia and hypoxia, as seen experimentally in culture systems 27, 28, 29. Increased BBB permeability occurs with normal ageing 30 and is accelerated in WMH and lacunar stroke 3. However, there is little evidence on interventions that might tighten the BBB thereby reducing the transit of potentially toxic factors through the vessel wall and into parenchymal tissue. Antioxidants and VEGF antibodies strengthen the BBB in experimental studies (Supplement Table S1). Of more practical use is the observation that both cGMP (dipyridamole) and cAMP (cilostazol, pentoxifylline) modulators can improve BBB integrity, at least in experimental studies (Supplement Table S1). Other compounds of potential interest include fasudil and topiramate (Supplement Table S1).

Blood pressure (BP) lowering

Hypertension is the most important modifiable risk factor for stroke and is also the strongest known vascular risk factor for SVD. Multiple trials have shown that treating high BP reduces first stroke. Only one trial assessed the effect of BP lowering on the type of any resulting stroke; in SHEP, antihypertensive therapy (chlorthalidone, with or without atenolol or reserpine) reduced the incidence of ischemic stroke, including lacunar subtype (Supplement Table S2).

A few trials have investigated secondary prevention after stroke either testing the treatment of hypertension, or of lowering BP irrespective of starting level; these found that antihypertensive drugs reduce second stroke (Supplement Table S3). With one exception, the studies either did not phenotype the type of index stroke, or did not report these results in stroke subtypes.

The SPS3 trial compared intensive vs. guideline BP lowering and found no significant reduction in recurrent stroke (Supplement Table S2); however, there was a strong trend to reduced recurrence and meta‐analysis of this and other data in SVD might well show a significant effect. In the absence of other data on lacunar stroke, data on other SVD features are relevant. Although antihypertensive therapy may be associated with less WMH progression in observational studies, little (PROGRESS, n = 192) or no (PRoFESS, n = 771) effect on WMH progression was seen in substudies of RCTs (Supplement Table S2). SPS3 found no benefit for intensive versus guideline BP lowering on long‐term cognition after lacunar stroke (31).

Unlike antiplatelet therapy, where just two years of therapy can be enough to demonstrate a therapeutic effect on outcome, antihypertensive agent trials may need longer treatment and follow‐up periods to detect reductions in stroke or SVD. In general, post‐stroke BP trials can be criticized for starting treatment too late after ictus, not continuing treatment for long enough, and not obtaining a large enough separation in BP between treatment and control groups. Nevertheless, lowering BP too much might also be hazardous, the so‐called ‘J‐shaped’ curve, especially in older patients or in those with a prior stroke 32, 33.

Blood pressure is but one hemodynamic measure altered by antihypertensive drugs and other parameters are also related to stroke, cognition and disability; these include heart rate 34, peak BP and variability 35, and rate‐pressure product. Furthermore, different antihypertensive drug classes are thought to have differential effects on stroke and cardiovascular disease prevention (Supplement Table S3), but there is no information on differential effects of classes in different stroke subtypes.

Endothelin

Endothelin‐1 is a potent peptide vasoconstrictor released by endothelial cells that acts as the physiological antagonist of NO (and PGI2). Most research has focused on the potential treatment of systemic and pulmonary hypertension with endothelin receptor antagonists. But endothelin may contribute to vasospasm associated with subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH), and has been used to induce experimental ischemic stroke 36, 37. Although endothelin receptor antagonists (such as clazosentan and TAK‐044) have been used for the treatment of SAH, their use in SVD has not been reported.

Immunosuppressive agents

The inflammatory nature of SVD suggests that immunomodulatory agents might also have a role in preventing or delaying the progression of SVD. Potent small molecules (e.g. methotrexate) and monoclonal antibodies (e.g. anti TNF‐alpha) probably have no role in view of their known toxicity and carcinogenic profile, although at least one trial is soon to start testing methotrexate in acute myocardial infarction (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01741558); additionally, monoclonal antibodies are very expensive and usually have poor brain penetration when given systemically. But less toxic and expensive agents might be relevant such as thalidomide, a teratogen, currently used in older people in the management of myeloma. Although its mechanisms of action are incompletely elucidated, thalidomide inhibits TNF‐α and is antiangiogenic. Changes in the immune response with advancing age would be a consideration if such agents were to be used in SVD.

Lipid lowering

The main therapeutic and licensed role for statins (HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors) is to lower LDL‐cholesterol in patients with a high risk of developing large artery atheromatous disease (MI or stroke), or who already have it. In addition to lipid lowering, statins exhibit multiple other effects (pleiotropism) including antiplatelet, anti‐inflammatory and pro‐endothelial activity (Supplement Table S1). These effects are mediated, in part, by increased vascular NO production through activation of nitric oxide synthase‐3 (NOS, endothelial NOS, eNOS). Statins may be categorized by:

Production method – fermentation‐derived (pravastatin, simvastatin) or synthetic (atorvastatin, fluvastatin, rosuvastatin).

Potency in LDL‐lowering at maximum dose – rosuvastatin > atorvastatin > simvastatin > pravastatin > fluvastatin.

Solubility – hydrophilic: fluvastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin; lipophilic: atorvastatin, simvastatin.

Such pharmacological differences and pleiotropic behaviour may impact on their ability to modulate the development or extension of SVD.

Statins reduce both first and recurrent stroke (Supplement Table S3). Although there are no large trials specifically after lacunar stroke, atorvastatin reduced recurrent stroke by similar amounts in small vessel (n = 1409) and large artery stroke (hazard ratio 0.85, 0.70 respectively) in the SPARCL trial (Supplement Table S2). In contrast, neutral effects were seen for simvastatin on amelioration of cognitive decline in the HPS mega‐trial, for pravastatin on WMH progression in 535 patients in PROSPER, for simvastatin (20 mg daily for 24 months) on WMH progression in 208 patients in ROCAS; and atorvastatin (80 mg daily for 3 months) on cerebral vasoreactivity and endothelial function in 94 patients with recent lacunar stroke (Supplement Table S2).

Neurotrophins

Cerebrolysin is a peptide product derived from pig brain with potential neurotrophic (including nerve growth factor activity) and neuroprotective activity. The drug is administered as an intravenous preparation given daily for days or weeks. Small studies have suggested that cerebrolysin might be effective in VaD (Supplement Table S3) but further trials are needed and specific effects in SVD have not been published. The relevance of cerebrolysin to SVD prevention or treatment is unclear in view of the need for intravenous administration (although a nasal preparation is in development).

Nitric oxide/cyclic GMP system

Nitric oxide is a key autocrine and paracrine mediator in numerous physiological and pathophysiological processes. NO is synthesized from the amino acid, L‐arginine, by NO synthase (including NOS‐3/eNOS), and from nitrate then nitrite through reduction. It stimulates down‐stream processes through the second messenger cyclic guanylate monophosphate (cGMP, Supplement Table S1, Fig. S2). cGMP is broken down by phosphodiesterase, predominantly type 5. So, the vascular L‐arginine/NO/cGMP/PDE system may be up‐regulated through enhancing L‐arginine or nitrate levels, increasing NO synthase activity, administering NO donors, and blocking PDE activity. In respect of actions that might be relevant to the development of SVD, NO has antiplatelet, anti‐leucocyte, anti‐smooth muscle cell, and other anti‐inflammatory activity, as well as pro‐endothelial and blood‐brain barrier actions (Supplement Table S1).

Increasing endogenous NO synthesis

Endogenous vascular NO synthesis may be augmented through increasing blood substrate levels of L‐arginine or nitrate, e.g. through diet, detected as changes in systemic and cerebral hemodynamics in some 38, 39, 40 but not all studies 41. The activity of NOS‐3 is up‐regulated by statins (Supplement Table S1).

NO donors

In experimental studies, NO donors are neuroprotective (Supplement Table S3) and anti‐inflammatory, e.g. through inhibiting white cell function (such as chemotaxis and adhesion, Supplement Table S1). In stroke, NO donors lower blood pressure and vasodilate cerebral vasculature (Supplement Table S2). It is important to note that NO donors vary in their antiplatelet activity – those that inhibit platelets (NO itself, and donors that spontaneously release NO such as sodium nitroprusside) and those that do not (organic nitrates such as isosorbide mononitrate and glyceryl trinitrate). The absence in platelets of the metabolic apparatus to release NO from organic nitrates explains this difference. Whether this explanation would be relevant in SVD‐prevention is not clear. Circulating NO levels are low in acute, and probably chronic, stroke 42, 43 although levels in lacunar stroke have not been individually reported; hence, one action of NO donors is to augment endogenous vascular NO levels.

cGMP augmentation/PDE5 inhibition

Phosphodiesterases (PDE) catalyze the hydrolysis of cyclic nucleotides (cAMP, cGMP) to inactive 5'‐cyclic nucleotides 44. 11 classes of PDEs (comprising more than 60 different isoforms) exist with differential effects on cAMP and cGMP. PDE types 3 (PDE3, primarily of relevance to cAMP metabolism) and 5 (PDE5, cGMP), and their inhibitors, are of most relevance to the vasculature and management post‐stroke. Relevant PDE‐inhibitors are either non‐selective (e.g. methylxanthines such as caffeine, pentoxifylline and theophylline) or selective, e.g. cilostazol inhibits PDE3, dipyridamole inhibits PDE5 (Supplement Table S1). Several PDE‐inhibitors also exhibit adenosine modulating effects acting either as adenosine re‐uptake inhibitors (cilostazol, dipyridamole, pentoxifylline) or as adenosine receptor antagonists.

PDE5 inhibitors mimic many of the features of NO, including exhibiting mild antiplatelet activity, and endothelial protection (manifest as a reduction in von Willebrand factor) (Supplement Table S1). The main PDE5‐inhibitor of clinical relevance to stroke is dipyridamole.

Dipyridamole is licensed for the secondary prevention of stroke based on trials involving monotherapy or when given with aspirin (Supplement Table S3). Although dipyridamole can cause a NO‐like headache, the presence of headache (indicating the presence of cerebrovascular reactivity) is associated with a reduced rate of stroke recurrence 45.

Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor (PPAR)‐gamma agonists

Pioglitazone, a PPAR‐gamma inhibitor that is licensed for diabetes management, has multiple properties that might attenuate SVD, including BP modulation, pro‐endothelial activity, anti‐vascular inflammation, lipid modulation, anti‐smooth muscle cell proliferation, and anti‐ fibrinolysis (Supplement Table S1). However, treatment with pioglitazone is associated with a number of adverse events such as weight gain, heart failure, and possibly bladder cancer.

In a post hoc analysis, pioglitazone was observed to reduce recurrence and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in 984 patients with type II diabetes and previous stroke in the PROactive trial; however the proportion of patients with SVD was not recorded at baseline (Supplement Table S2). Further, pioglitazone did not prevent first stroke.

Prostacyclin/cyclic AMP system

Prostacyclin I2 (PGI2), related prostaglandins (e.g. PGE2), and their mimics, exert many of the effects seen with NO and cGMP modifying agents (Supplement Table S1). This includes antiplatelet, anti‐smooth muscle and anti‐inflammatory activity, and pro‐endothelial effects. PGI2 is synthesized from prostaglandin H2 by prostacyclin synthase. Since PGH2 is synthesized by COX1/2 (PGH2 synthase), PGI2 production is attenuated by aspirin. Many of the effects of PGI2 are mediated by the second messenger, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP, Fig. 2), which is broken down by PDE3 (among other PDEs).

Figure 2.

Targets and potential pharmacological interventions for preventing and/or treating small vessel disease. The green arrows indicate the site of some actions of a drug. The diagram indicates drugs acting on red blood cells, platelets, endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells (and potentially on pericytes).

Prostacyclin and mimetics

Intravenous PGI2 has been assessed in several small trials in acute stroke (Supplement Table S3). In the context of SVD prevention/treatment, PGI2 and its prostaglandin derivatives and mimetics (e.g. beraprost, treprostinil), are probably not suitable agents since they have to be given intravenously or very frequently by inhalation, and no suitable oral preparations are available.

cAMP augmentation/PDE3 inhibition

The PGI2/cAMP system may best be stimulated chronically by reducing the metabolism of cAMP with an oral PDE3 inhibitor such as cilostazol, pentoxifylline or triflusal. PDE‐inhibitors have the added advantage that they may increase NO production by modulating dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolases (Supplement Table S1).

Cilostazol: Cilostazol is licensed for peripheral vascular disease (PVD) 46 but has also been shown to reduce recurrent ischemic stroke, with fewer haemorrhagic complications than aspirin (Supplement Tables S2–S4). Cilostazol was also assessed in chronic lacunar stroke for effects on forearm vascular reactivity 47, and acute lenticulostriate stroke for neurological deterioration 48. Experimentally, cilostazol may enhance white matter regeneration after ischemia (Supplement Table S2) 49; in SHRSP, it both improved motor and cognitive function and reduced infarct size as compared with aspirin 50. Further trials of cilostazol beyond those listed in Supplementary Table S4 are thought to be ongoing.

Pentoxifylline: Pentoxifylline, propentofylline and pentifyline are related methylxanthines that have been studied in several trials in acute ischemic stroke and dementia prevention (Supplement Table S3); although some results were promising, the RCTs were small and of suboptimal design. Pentoxifylline is licensed for the treatment of PVD and improves the healing of venous leg ulcers. Theophylline, another methylxanthine (and commonly found in tea), has similar effects.

Triflusal has multiple modes of action including acting as an inhibitor of COX1 (in platelets but not endothelium) and PDE3, protecting PGI2 from metabolism, and promoting the release of NO (through stimulating NOS‐3) from white cells. Triflusal is licensed for the prevention of recurrent vascular events in high‐risk individuals.

None of the larger stroke trials of PDE‐inhibitors have focused on patients with SVD; indeed stroke subtype was usually not phenotyped so the beneficial results might be more or less relevant for patients with SVD as compared with other types of stroke.

Rho‐kinase (ROCK)‐antagonists

Fasudil, a selective rho‐kinase inhibitor, increases the integrity of the blood brain barrier and reduces small muscle cell proliferation (Supplement Table S1) in acute experimental models of stroke. It improved early neurological deficit vs. placebo in 160 patients with acute ischemic stroke; the subtype of stroke was not specified in this study 51 and there are no specific data for SVD. The effects on chronic BBB dysfunction, which might have a different mechanism to that seen after acute ischemic stroke, are not known.

Stimulants

Stimulant agents include sympathomimetics (e.g. amphetamine) and eugeroics (which increase catecholaminergic and histaminergic activity in the brain). Modafinil, an eugeroic that inhibits dopamine transport, is licensed for the treatment of narcolepsy, and potentially enhances cognition and reduces fatigue. However, its role in stroke and SVD remains untested. Although amphetamine has been assessed for promoting recovery after stroke, it increased BP and was associated with increased deaths (Supplement Table S3).

Vitamins

Amongst multiple classes of vitamins, the ones potentially of most interest to stroke are those that modulate homocysteine metabolism, namely B6, B12 and folate. Although trials of these failed to prevent stroke recurrence (Supplement Table S3), a small neuroimaging substudy (using MRI) from the large VITATOPS trial suggested that B vitamins might be associated with less WMH change in patients with severe WMH at baseline (Supplement Table S2).

Xanthine oxidase inhibitors

Allopurinol and febuxostat, xanthine oxidase inhibitors, lower plasma uric acid levels and are licensed for the prevention of gout (Supplement Table S3). Allopurinol also increases NO availability, has anti‐inflammatory effects, reduces augmentation index (reducing stiffness in large compliance arteries), reduces left ventricular hypertrophy, and modulates BP. However, the type, magnitude and direction of the relationship between urate and vascular disease is unclear, and might be explained by co‐association with body mass index 52. The effects of allopurinol in clinical trials are mixed, and allopurinol is associated with adverse events at high dose. In a small study in 50 patients with subcortical stroke, allopurinol did not alter cerebral vasoreactivity, augmentation index or soluble markers of inflammation (Supplement Table S2).

Other potential therapeutic strategies

Multiple other interventions may have properties that are relevant to SVD‐prevention:

Information from experimental stroke models: Several other interventions have been proposed as treatment or prevention strategies for SVD, including nicotiflorin (a flavonoid), minocycline and relaxin (Supplement Table S3). However many of the experimental models were not relevant to human intrinsic SVD and the evidence for any of these drugs is limited by small numbers and suboptimal methods.

Lifestyle modifications 53: These include smoking cessation, salt reduction, increased dietary nitrates, dietary flavonones 54, a healthy diet 55, and exercise 56. However, whether any of these have differential effects on lacunar stroke/SVD or are simply good for general health is unclear. Clearly smoking cessation is a major public health target worldwide and should be encouraged. Decreasing salt intake reduces blood pressure, platelet adhesion and oxidative stress and improves vascular function in salt‐replete and sensitive individuals 57, 58 so probably benefits both large artery disease and SVD. Short‐term dietary nitrates increase frontal white matter perfusion 40 and increase cerebrovascular reactivity in young people 59. L‐arginine supplements (e.g. in the form of ‘Heart bars’) reduce eclampsia 60. Some trials are testing multiple risk factor interventions, i.e. two or more of the above 61. A recent systematic review identified 25 non‐pharmacological and eight multiple risk factor intervention trials; of these, 16 were published and 17 ongoing (Supplement Tables S3 and S4); these trials are not discussed further here. It is worth noting that lifestyle modifications can be difficult to implement, and are very difficult to sustain chronically in a trial environment.

Cognitive interventions: Several ongoing trials are assessing a variety of cognitive interventions, including coaching, strategy training, and reading skills. Such trials are not discussed further here.

Preventing and treating SVD

Existing data

Ultimately, new large scale RCTs will be needed to assess whether specific interventions can prevent the development of SVD and/or treat its progression. But information is required now on whether current guideline‐based treatments (e.g. antihypertensives, antiplatelets and statins) have any benefit for preventing first or recurrent lacunar stroke; much might be learnt from existing trials of these interventions, especially where patients with identified SVD were randomized (e.g. with lacunar stroke as in SPS3 22, 62), or where SVD outcomes were recorded (such as WMH, as assessed in a PRoFESS substudy, Supplement Table S2).

To this end, the authors are coordinating a data‐pooling project with the aim of collecting individual patient data on clinical and neuroimaging measures from appropriate RCTs. The aim is to assess whether existing pharmacological interventions already have evidence for preventing SVD development and progression. Nevertheless, this approach will be limited since most trials did not accurately‐phenotype the diagnosis or outcome of SVD; further, even where subtyping was attempted, the imperfect distinction of lacunar from non‐lacunar stroke based on clinical syndrome plus CT scanning (as used in most previous trials) will have misclassified about 20% of lacunar as non‐lacunar strokes and vice versa 63, thus adding ‘noise’ to any retrospective analysis.

Ongoing and planned RCTs

A number of ongoing trials are assessing patients with SVD, as described in Supplement Table S4. These may be categorized according to their design:

Aim: Prevention of new events, or treatment of existing disease.

Patients: SVD absent or present, pre‐ or post‐stroke, cognition normal or impaired.

Intervention: Drug, device, or management strategy (intensity of treatment).

Comparator: Placebo, or open‐label.

Outcome: Prevention of SVD or stroke, functional outcome, cognition or neuroimaging measure.

Design: Double‐blind placebo‐controlled, single‐blind blinded‐outcome, or open‐label blinded‐outcome.

Which interventions should be tested for SVD?

This review has highlighted potential mechanisms that might modulate SVD and several drugs with one or more of these relevant mechanisms of action. However, as yet none of these interventions have been shown definitely to prevent or treat SVD. Nevertheless, some provisional conclusions can be drawn:

Both BP and lipid lowering are standard secondary prevention interventions after an ischemic stroke or TIA. Similarly, both have biologically plausible mechanisms by which they might prevent SVD. But their routine use means that further testing would necessitate a comparison either of intensive vs. standard (guideline) lowering, or a comparison of drug classes (as discussed above).

Potent antiplatelet agents (aspirin, clopidogrel) do not appear to have a role since they are already used routinely, either individually or together, after ischemic stroke whilst long‐term intensive treatment based on their combination is associated with increased major intra‐ and extra‐cranial bleeding (Supplement Tables S2 and 3).

Agents that increase cAMP or cGMP appear promising with theoretical protective effects on endothelium and the blood‐brain barrier, and attenuating effects on inflammation, platelets, smooth muscle cell and white cells. Hence drugs that induce cAMP or reduce its degradation (PDE3 inhibitors such as aminophylline, cilostazol, pentoxifylline or triflusal), or induce cGMP (NO donors) or reduce its degradation (PDE5 inhibitors such as dipyridamole) are candidates for testing, especially since all are already licensed for clinical use. One concern is that the mild anti‐platelet effects of PDE inhibitors (e.g. cilostazol, dipyridamole) and their chronic co‐administration with a potent antiplatelet agent (such as clopidogrel) might increase bleeding, although this was not seen when aspirin and dipyridamole were used together in ESPS‐2 and ESPRIT (Supplement Table S2).

To maximize modulation of the multiple systems that contribute to the development and extension of SVD, it may be necessary to use either drugs that have multiple mechanisms of action (such as NO donors, PDE‐inhibitors and statins, Supplement Table S1), or combinations of drugs, or a mix of both.

- Potential combinations of drugs are either:

- Those that have unrelated but potentially synergistic effects. Useful combinations might include assessing two or more of the various types of interventions described above, e.g. intensive BP lowering and statins, PPAR‐gamma antagonist and xanthine oxidase inhibitor, or intensive BP lowering and raising NO.

- Combining agents that have related effects, e.g. by raising cAMP and cGMP. Potential combinations include dipyridamole and pentoxifylline 64, dipyridamole and cilostazol 65, and isosorbide mononitrate and cilostazol. Alternatively, hybrid drugs that comprise a NO donor and cAMP modulator might be relevant, e.g. cilostazol dinitrate 66.

It is conceivable that some treatment strategies might have differential effects on the various types of SVD; whilst BP lowering might be beneficial on all, statins and antiplatelets might be beneficial in reducing lacunar stroke but increase symptomatic bleeding from micro‐bleeds due to their antithrombotic activity. This emphasizes the need to monitor all features of SVD in future trials.

Conclusions

There are no established therapeutic strategies for either preventing or treating SVD although more information about strategies to avoid and that show promise are emerging 4. A number of routine vascular prophylaxis strategies, especially lowering BP, might reduce SVD but their current guideline use means any future trials would have to test intensity of treatment. Other potential interventions are not in routine use post stroke and have multiple activities with the potential for targeting mechanisms of SVD formation. It is clear that further trials dedicated to preventing the development or worsening of SVD are now required.

Supporting information

Table S1. Effects of drug classes and individual drugs on general categories of mechanisms that might be relevant for preventing or treating small vessel disease.

Table S2. Completed randomized controlled trials that either included patients with small vessel disease (SVD), or where SVD was an outcome.

Table S3. Published systematic reviews of drugs and drug classes in stroke that may be worth testing for the prevention or treatment of small vessel disease.

Table S4. Ongoing randomized clinical trials where either (i) patients with small vessel disease (SVD) are included, or (ii) SVD is an outcome.

Acknowledgements

PMWB is Stroke Association Professor of Stroke Medicine. JMW is supported by the Scottish Funding Council through the SINAPSE Collaboration (http://www.sinapse.ac.uk). Support for writing the review came from the MRC (ENOS Trial, G0501797), HTA (Tardis Trial, 10/104/24), Stroke Association and Alzheimer's Society (PODCAST Trial, 2008/09), and Wellcome Trust (088134/Z/09).

Conflict of interest: PMWB is Chief Investigator of the ‘Efficacy of Nitric Oxide in Stroke’ (ENOS), ‘Triple Antiplatelets for Reducing Dependency after Ischaemic Stroke’ (TARDIS) and ‘Prevention Of Decline in Cognition After Stroke Trial’ (PODCAST) academic studies; and was a member of the Trial Steering Committee of the PRoFESS trial. JMW is Imaging Lead for ENOS, coordinated the Centres of Excellence in Neurodegeneration STRIVE guidelines, is Chief Investigator of the Wellcome Trust–funded Mild Stroke Study 2, and imaging lead for the MRC Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology. They have no commercial disclosures of relevance to this review.

References

- 1. Warlow C, Sudlow C, Dennis M, Wardlaw J, Sandercock P. Stroke. Lancet 2003; 362:1211–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9:689–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ et al Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12:822–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arboix A, Blanco‐Rojas L, Marti‐Vilalta J. Advancements in understanding the mechanisms of symptomatic lacunar ischemic stroke: translation of knowledge to prevention strategies. Expert Rev Neurother 2014; 14:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jackson CA, Hutchison A, Dennis MS, Wardlaw JM, Lewis SC, Sudlow CL. Differences between ischemic stroke subtypes in vascular outcomes support a distinct lacunar ischemic stroke arteriopathy: a prospective, hospital‐based study. Stroke 2009; 40:3679–3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Makin SD, Turpin S, Dennis MS, Wardlaw JM. Cognitive impairment after lacunar stroke: systematic review and meta‐analysis of incidence, prevalence and comparison with other stroke subtypes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013; 84:893–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Windham BG, Griswold ME, Shibata D, Penman A, Catellier DJ, Mosley TH Jr. Covert neurological symptoms associated with silent infarcts from midlife to older age: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Stroke 2012; 43:1218–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rost NS, Rahman RM, Biffi A et al White matter hyperintensity volume is increased in small vessel stroke subtypes. Neurology 2010; 75:1670–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wardlaw JM, Lewis SC, Keir SL, Dennis MS, Shenkin S. Cerebral microbleeds are associated with lacunar stroke defined clinically and radiologically, independently of white matter lesions. Stroke 2006; 37:2633–2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Potter GM, Doubal FN, Jackson CA et al Counting cavitating lacunes underestimates the burden of lacunar infarction. Stroke 2010; 41:267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ 2010; 341:c3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vermeer SE, Longstreth WT Jr, Koudstaal PJ. Silent brain infarcts: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6:611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arboix A, Garcia‐Eroles L, Massons J, Oliveres M. Hemorrhagic Lacunar Stroke. Cerebrov Dis 2000; 10:229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morris Z, Whiteley WN, Longstreth WT Jr et al Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ 2009; 339:b3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blanco‐Rojas L, Arboix A, Canovas D, Grau‐Olivares M, Morera J, Parra O. Cognitive profile in patients with a first‐ever lacunar infarct with and without silent lacunes: a comparative study. BMC Neurol 2013; 13:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aribisala B, Valdes Hernandez M, Royle N et al Brain atrophy associations with white matter lesions in the ageing brain: the Lothian Birth Cohort. Eur Radiol 1936; 23:1084–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Duering M, Righart R, Csanadi E et al Incident subcortical infarcts induce focal thinning in connected cortical regions. Neurology 2012; 79:2025–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grau‐Olivares M, Arboix A, Junque C, Arenaza‐Urquijo E, Rovira M, Bartres F. Progressive gray matter atrophy in lacunar patients with vascular mild cognitive impairment. Cerebrov Dis 2010; 30:157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Qaseem A, Snow V, Cross JT Jr et al Current pharmacologic treatment of dementia: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148:370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bene A, Makin S, Doubal F, Inzitari D, Wardlaw J. Variation in risk factors for recent small subcortical infarcts with infarct size, shape, and location. Stroke 2013; 44:3000–3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Topol E, Easton D, Harrington R et al Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, international trial of the oral IIb/IIIa antagonist lotrafiban in coronary and cerebrovascular disease. Am Heart Assoc 2003; 108:399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, Szychowski JM, Coffey CS, Pearce LA. Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:817–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Palacio S, Hart RG, Pearce LA, Benavente OR. Effect of addition of clopidogrel to aspirin on mortality: systematic review of randomized trials. Stroke 2012; 43:2157–2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morrow D, Braunwald M, Bonaca M et al Vorapaxar in the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1404–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bath PMW, Blann A, Smith N, Butterworth RJ. Von Willebrand factor, p‐selectin and fibrinogen levels in patients with acute ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, and their relationship with stroke sub‐type and functional outcome. Platelets 1998; 9:155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lavallee PC, Labreuche J, Faille D et al Circulating markers of endothelial dysfunction and platelet activation in patients with severe symptomatic cerebral small vessel disease. Cerebrovasc Dis 2013; 36:131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Allen CL, Bayraktutan U. Antioxidants attenuate hyperglycaemia‐mediated brain endothelial cell dysfunction and blood‐brain barrier ghypermeability. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009; 11:480–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Allen C, Srivastava K, Bayraktutan U. Small GTPase RhoA and its effector rho kinase mediate oxygen glucose deprivation‐evoked in vitro cerebral barrier dysfunction. Stroke 2010; 41:2056–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shao B, Bayraktutan U. Hyperglycaemia promotes cerebral barrier dysfunction through activation of protein kinase C‐beta. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013; 15:993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Farrall AJ, Wardlaw JM. Blood‐brain barrier: ageing and microvascular disease–systematic review and meta‐analysis. Neurobiol Aging 2009; 30:337–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pearce LA, McClure LA, Anderson DC et al Effects of long‐term blood pressure lowering and dual antiplatelet treatment on cognitive function in patients with recent lacunar stroke: a secondary analysis from the SPS3 randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13:1177–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ovbiagele B, Diener H‐C, Yusuf S et al Level of systolic blood pressure within the normal range and risk of recurrent stroke. JAMA 2011; 306:2137–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sabayan B, van Vliet P, de Ruijter W, Gussekloo J, de Craen AJ, Westendorp RG. High blood pressure, physical and cognitive function, and risk of stroke in the oldest old: the Leiden 85‐plus Study. Stroke 2013; 44:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bohm M, Cotton D, Foster L et al Impact of resting heart rate on mortality, disability and cognitive decline in patients after ischaemic stroke. Eur Heart J 2012; 33:2804–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E et al Prognostic significance of visit‐to‐visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet 2010; 375:895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hainsworth AH, Markus HS. Do in vivo experimental models reflect human cerebral small vessel disease? A systematic review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008; 28:1877–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bailey EL, McCulloch J, Sudlow C, Wardlaw JM. Potential animal models of lacunar stroke: a systematic review. Stroke 2009; 40:e451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hishikawa K, Nakaki T, Tsuda M et al Effect of systemic L‐arginine administration on hemodynamics and nitric oxide release in man. Jpn Heart J 1992; 33:41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Larsen FJ, Lundberg JO. Effects of dietary nitrate on blood pressure in health volunteers. NEJM 2006; 355:2792–2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Presley TD, Morgan AR, Bechtold E et al Acute effect of a high nitrate diet on brain perfusion in older adults. Nitric Oxide 2011; 24:34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baudouin SV, Bath P, Martin JF, Du Bois R, Evans TW. L‐arginine infusion has no effect on systemic haemodynamics in normal volunteers, or systemic and pulmonary haemodynamics in patients with elevated pulmonary vascular resistance. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1993; 36:45–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rashid PA, Whitehurst A, Lawson N, Bath PMW. Plasma nitric oxide (nitrate/nitrite) levels in acute stroke and their relationship with severity and outcome. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2003; 12:82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ferlito S, Gallina M, Pitari GM, Bianchi A. Nitric oxide plasma levels in patients with chronic and acute cerebrovascular disorders. Panminerva Med 1998; 40:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gresele P, Momi S, Falcinelli E. Anti‐platelet therapy: phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011; 72:634–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Davidai G, Cotton D, Gorelick P et al Dipyridamole‐induced headache and lower recurrence risk in secondary prevention of ischaemic stroke: a post hoc analysis. Eur J Neurol 2014; 21:1311–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dawson DL, Cutler BS, Meissner MH, Strandness DE. Cilostazol has beneficial effects in treatment of intermittent clauidication. Circulation 1998; 98:678–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Han SW, Lee SS, Kim SH et al Effect of cilostazol in acute lacunar infarction based on pulsatility index of transcranial Doppler (ECLIPse): a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Eur Neurol 2013; 69:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kondo R, Matsumoto Y, Furui E et al Effect of cilostazol in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke in the lenticulostriate artery territory. Eur Neurol 2013; 69:122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Miyamoto N, Tanaka R, Shimura H et al Phosphodiesterase III inhibition promotes differentiation and survival of oligodendrocyte progenitors and enhances regeneration of ischemic white matter lesions in the adult mammalian brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010; 30:299–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Omote Y, Deguchi K, Tian F et al Clinical and pathological improvement in stroke‐prone spontaneous hypertensive rats related to the pleiotropic effect of cilostazol. Stroke 2012; 43:1639–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shibuya M, Hirai S, Seto M, Satoh S, Ohtomo E. Effects of fasudil in acute ischemic stroke: results of a prospective placebo‐controlled double‐blind trial. J Neurol Sci 2005; 238:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Palmer TM, Nordestgaard BG, Benn M et al Association of plasma uric acid with ischaemic heart disease and blood pressure: mendelian randomisation analysis of two large cohorts. BMJ 2013; 347:f4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brainin M, Tuomilehto J, Heiss W‐D et al Post‐stroke cognitive decline: an update and persepctives for clinical research. Eur J Neurol 2015; 22:229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cassidy A, Rimm EB, O'Reilly EJ et al Dietary flavonoids and risk of stroke in women. Stroke 2012; 43:946–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dehghan M, Mente A, Teo KK et al Relationship between healthy diet and risk of cardiovascular disease among patients on drug therapies for secondary prevention: a prospective cohort study of 31 546 high‐risk individuals from 40 countries. Circulation 2012; 126:2705–2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lawrence M, Kerr S, McVey C, Godwin J. The effectiveness of secondary prevention lifestyle interventions designed to change lifestyle behavior following stroke: summary of a systematic review. Int J Stroke 2012; 7:243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bath PMW, Cappuccio FP, Singer DRJ, Markandu NM, MacGregor GA. A high salt intake is associated with an increase in platelet size: a further risk factor for vascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovas Dis 1995; 5:71–75. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Al‐Solaiman Y, Jesri A, Zhao Y, Morrow JD, Egan BM. Low‐Sodium DASH reduces oxidative stress and improves vascular function in salt‐sensitive humans. J Hum Hypertens 2009; 23:826–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Aamand R, Dalsgaard T, Ho YC, Moller A, Roepstorff A, Lund TE. A NO way to BOLD?: dietary nitrate alters the hemodynamic response to visual stimulation. Neuroimage 2013; 83C:397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vadillo‐Ortega F, Perichart‐Perera O, Espino S et al Effect of supplementation during pregnancy with L‐arginine and antioxidant vitamins in medical food on pre‐eclampsia in high risk population: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2011; 342:d2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Teuschl Y, Matz K, Brainin M. Prevention of post‐stroke cognitive decline: a review focusing on lifestyle interventions. Eur J Neurol 2013; 20:35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Benavente OR, Coffey CS, Conwit R et al Blood‐pressure targets in patients with recent lacunar stroke: the SPS3 randomised trial. Lancet 2013; 382:507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Potter G, Doubal F, Jackson C, Sudlow C, Dennis M, Wardlaw J. Associations of clinical stroke misclassification (‘clinical‐imaging dissociation’) in acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010; 29:395–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Santos MT, Valles J, Aznar J, Yaya R, Perez‐Requejo JL. Effects of dipyridamole, pentoxifylline or dipyridamole plus pentoxifylline on platelet reactivity in patients with ischemic cerebrovascular insufficiency. Thromb Res 1993; 72:219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rondina MT, Weyrich AS. Targeting phosphodiesterases in anti‐platelet therapy. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2012; 210:225–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Knorr M, Hausding M, Schulz E et al Characterization of new organic nitrate hybrid drugs covalently bound to valsartan and cilostazol. Pharmacology 2012; 90:193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Effects of drug classes and individual drugs on general categories of mechanisms that might be relevant for preventing or treating small vessel disease.

Table S2. Completed randomized controlled trials that either included patients with small vessel disease (SVD), or where SVD was an outcome.

Table S3. Published systematic reviews of drugs and drug classes in stroke that may be worth testing for the prevention or treatment of small vessel disease.

Table S4. Ongoing randomized clinical trials where either (i) patients with small vessel disease (SVD) are included, or (ii) SVD is an outcome.