Abstract

Aims

Most people who quit smoking for a short term will return to smoking again in 12 months. We tested whether self‐help booklets can reduce relapse in short‐term quitters after receiving behavioural and pharmacological cessation treatment.

Design

A parallel‐arm, pragmatic individually randomized controlled trial.

Setting

Smoking cessation clinics in England. Participants People who stopped smoking for 4 weeks after receiving cessation treatment in stop smoking clinics.

Intervention

Participants in the experimental group (n = 703) were mailed eight booklets, each of which taught readers how to resist urges to smoke. Participants in the control group (n = 704) received a leaflet currently used in practice.

Measurements

The primary outcome was prolonged, carbon monoxide‐verified abstinence from months 4 to 12. The secondary outcomes included 7‐day self#x02010;reported abstinence at 3 and 12 months. Mixed‐effects logistic regression was used to estimate treatment effects and to investigate possible effect modifying variables.

Findings

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in prolonged abstinence from months 4 to 12 (36.9% versus 38.6%; odds ratio 0.93, 95% confidence interval 0.75–1.16; P = 0.524). In addition, there were no significant differences between the groups in any secondary outcomes. However, people who reported knowing risky situations for relapse and using strategies to handle urges to smoke were less likely to relapse.

Conclusions

In people who stop smoking successfully with behavioural support, a comprehensive self‐help educational programme to teach people skills to identify and respond to high‐risk situations for return to smoking did not reduce relapse.

Keywords: Behavioural support, coping skills, educational booklets, smoking relapse

Introduction

Smoking remains the leading preventable cause of premature deaths globally 1, 2, although smoking cessation in middle age can prevent most of this excess mortality 3. Many smokers will quit smoking successfully after receiving behavioural support and pharmacotherapy 4. However, most short‐term quitters will relapse and return to regular smoking within a year. For example, a study in the United Kingdom found that 75% of quitters who were abstinent at 4 weeks after quit dates started smoking again by 12 months 5. There is a need to find effective interventions to reduce relapse rates after the initial treatment episode.

The cognitive–behavioural approach to coping skills training has been used to develop interventions for the prevention of smoking relapse 6. A systematic review found insufficient evidence to support the use of any specific intervention for preventing smoking relapse in short‐term quitters, and it was unclear why most interventions were unsuccessful 7. However, results of exploratory meta‐analyses indicated that the risk of smoking relapse may be reduced by self‐help educational materials that taught people skills to cope with urges to smoke 8, 9. The use of self‐help educational materials is relatively inexpensive compared to pharmacotherapy and counselling interventions, and known to be effective compared to no treatment in supporting smoking cessation 10. However, previous studies evaluated self‐help educational materials for smoking relapse prevention in mostly unaided quitters who stopped smoking without professional support 8. Therefore, further research was recommended to evaluate self‐help educational materials for the prevention of smoking relapse in people who stopped smoking with support from stop smoking services 11.

The objective of this study was to compare the effectiveness of a set of self‐help educational booklets and a simple leaflet in preventing smoking relapse in people who quit smoking after receiving intensive cessation treatment. Our hypothesis was that additional self‐help booklets designed specifically to teach people skills to identify risky situations and respond appropriately would prevent relapse to smoking. The main results of the effectiveness of the treatment are reported in this paper, and the full details and results of the study will be published in a Health Technology Assessment monograph 12.

Methods

This was a parallel‐arm pragmatic individually randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of self‐help educational material in preventing smoking relapse, compared with a self‐help leaflet used currently. Research ethical approval was granted by the East of England Research Ethics Committee (reference number: 11/EE/0091). The trial was registered prospectively (Current Controlled Trials, ISRCTN36980856), and the protocol was published in an open‐access journal 13.

Study population

The target population consisted of smokers who received intensive smoking cessation treatment in stop smoking clinics and were abstinent at 4 weeks after the quit date. Study participants were treated smokers who reported abstinence from at least day 14 after a quit date to the 4‐week follow‐up point and who produced an exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) reading of < 10 parts per million (p.p.m.). We excluded 4‐week quitters who were younger than 18 years, pregnant or unable to read booklets in English, as well as quitters from families at the same address.

The National Health Service (NHS) stop smoking service has been established since 2001 in England to provide behavioural support and pharmacotherapy to smokers who would like to quit. The English stop smoking services include specialist stop smoking clinics, primary care and pharmacy 14. Clients set a quit date after 2 weeks pre‐quit preparation, and received additional weekly behavioural support in group or one‐to‐one counselling sessions for 4 weeks after quit date. Cessation medications are also provided, including the use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion and varenicline. In 2010/2011, 34% of smokers who set a quit date in English stop smoking clinics stopped smoking 4 weeks after the quit date 15. However, approximately 75% of these short‐term quitters returned to regular smoking within 12 months 5. Study participants were recruited initially from the specialist stop smoking clinic in Norfolk. Because the recruitment rate was slower than anticipated, the participant recruitment was expanded to non‐specialist settings (including general practice and pharmacy) in Norfolk, and to stop smoking clinics in Suffolk, Hertfordshire, Lincolnshire, Great Yarmouth and Waveney in England.

Sample size

A meta‐analysis indicated that coping skills training interventions (including the use of self‐help booklets) may reduce the odds of smoking relapse in unaided quitters (odds ratio = 1.44) 9. Therefore, the abstinence rate of 4‐week quitters at 12 months was estimated to be 25.0% in the control group and 32.4% in the intervention group. Assuming α = 0.05, 1‐β = 0.80 and a dropout rate of 15%, approximately 700 participants were required in each of the two arms 16.

Randomization and masking

Smoking cessation advisers introduced the study, gained consent for participation from their clients and collected baseline data. On the return of baseline data, trial coordinators allocated participants randomly, using a computerized allocation system provided by the Norwich Clinical Trial Unit (CTU) which ensured allocation concealment. We used simple randomization with no stratification or blocking by participant characteristics or site. This was an open trial, without attempts to blind investigators and patients after randomization.

Interventions investigated

After randomization, researchers mailed the experimental and control self‐help materials to participants. The experimental intervention was the full pack of eight Forever Free booklets 17. The content of the Forever Free booklets is based on the cognitive–behavioural approach to coping skills training 6. Quitters are trained to anticipate situations with high risks of smoking relapse (such as going out with friends or feeling frustrated), and to develop skills to cope with such situations and urges to smoke again. Booklet 1 is a brief summary of all issues relevant to smoking relapse prevention. The remaining seven booklets provide more information on important issues for relapse prevention (see Appendix S1 for the contents of booklets and leaflet investigated in the study). The original Forever Free booklets were developed in the United States. We revised the booklets to make the material more suitable to British users, mainly changing spellings, Americanisms and some culturally specific examples 13. The control leaflet ‘Learning to Stay Stopped’ is used commonly in NHS practice and contains brief but comprehensive information on issues related to smoking relapse, and also provides brief recommendations on how to cope with cravings and tempting triggers.

Outcomes and data collection

The primary outcome was prolonged abstinence from months 4 to 12 after the quit date, with no more than five cigarettes in total, and confirmed by CO < 10 p.p.m. at the 12‐month follow‐up. Participants who declined biochemical verification or who did not respond to follow‐up were classified as smokers. However, participants who died or were known to have moved away were excluded from the numerator and denominator 18. The secondary outcomes were 7‐day self‐reported abstinence at 3 months, 7‐day self‐report and CO‐validated abstinence at 12 months after the quit date.

Methods for baseline and follow‐up data collection were described in detail in the published trial protocol 13. Study participants were followed‐up by researchers at 3 and 12 months after the quit date. The follow‐up interviews were conducted by telephone and involved the researchers administering a questionnaire about the participants’ smoking status and their use of self‐help booklets. At the 12‐month follow‐up participants were asked whether they had smoked at all, and the number of cigarettes smoked, between 4 and 12 months. Participants who reported 7‐day abstinence at the 12‐month follow‐up were invited for a CO test. People came to a local centre or a researcher visited them at home for this test. A £20 shopping voucher was given to each of the participants who completed the CO test at the 12‐month follow‐up.

At the follow‐up interviews, trial participants reported receipt and reading of the self‐help booklets. We then asked trial participants whether the educational materials helped them to identify risky situations and to know more ways of handling urges to smoke again. Thirdly, we investigated whether trial participants had actually applied the skills learnt from the booklets. Finally, we invited the participants to give an overall assessment of the usefulness of the booklets.

Data analysis methods

The comparison of smoking abstinence rates (and other binary outcomes) between the two groups was carried out using the odds ratio as the measure of treatment effect, and reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). There were six study sites by area and type of stop smoking service (specialist or non‐specialist). We used a mixed‐effects logistic model to estimate treatment effects to allow for variation in baseline smoking rates between study sites but a common treatment effect across study sites, through modelling a random intercept, fixed slopes and heterogeneous residual variance across different study sites. We also analysed the primary outcome in mixed‐effects regression after adjusting for a range of baseline variables, including age, sex, marital status, education level, unemployment, receipt of free prescription, living with a smoking partner, number of cigarettes per day before quitting, first cigarette within 5 minutes after waking, any previous quit attempts, longest time managed to quit previously and cessation support from specialist or non‐specialist services. To explore possible effect modifying variables, an interaction term was added to each of the baseline variables in the adjusted analyses. (Note: only one interaction term was added in each adjusted analysis.)

The association between the smoking outcome and important process variables (including reading of booklets or leaflet, know more about risky situations or ways of handling urges and ever tried to do something to handle urges) was also examined by mixed‐effects logistic regression.

We planned to estimate survival curves for smoking abstinence by using data on time to the first event of smoking relapse. Because of inadequate reporting by a large proportion of relapse participants of the time that the first relapse occurred, this secondary analysis was not conducted. The exploratory mediation analyses 19 were also planned for any significant differences in the primary or secondary outcomes between groups, which were not conducted due to statistically non‐significant results for all smoking outcomes.

Data analyses were conducted using Stata software (Stata/IC for Windows, version 13.1).

Results

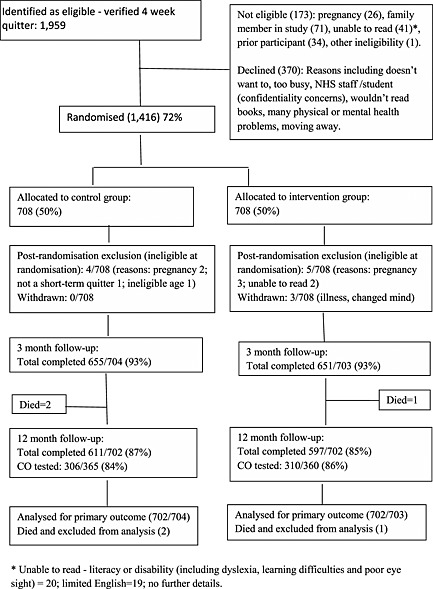

Between August 2011 and June 2013, we recruited and allocated randomly 1416 quitters to the intervention and the control group (Fig. 1). After randomization, four participants in the control group and five in the intervention group were found to be ineligible. In addition, three participants in the intervention group and none in the control group withdrew from the study due to illness or other reasons. The overall follow‐up rate was 93% at the 3‐month follow‐up and 86% at the 12‐month follow‐up. At the 12‐month follow‐up, 725 participants reported abstinence in the past 7 days and were therefore eligible for a CO test. Verification tests were carried out for 616 of these participants (85%), while 109 participants declined or were unable to have the test (all therefore classified as smokers).

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram

Of the initially recruited 1416 participants, 85% were from Norfolk (n = 1208), and the number of participants from other sites was small: 75 from Suffolk, 75 from Hertfordshire, 51 from Lincolnshire and seven from Great Yarmouth and Waveney. In addition, 1098 of the 1416 participants were from specialist stop smoking clinics and only 318 (22%) were recruited from non‐specialist settings.

The two arms were comparable in participant characteristics, including age, sex, education, employment status and smoking history (including cigarettes per day before quitting, first cigarette after waking up and previous quit attempts) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and smoking history at baseline.

| Intervention (n = 703) | Control (n = 704) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 47.8 (14.1) | 47.9 (13.6) |

| Sex (female) | 381 (54.2%) | 360 (51.1%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/living with partner | 444 (63.2%) | 423 (60.1%) |

| Separated/divorced | 110 (15.6%) | 114 (16.2%) |

| Single | 118 (16.8%) | 138 (19.6%) |

| Other/unknown | 31 (4.4%) | 29 (4.1%) |

| Ethnic origin | ||

| White | 690 (98.2%) | 695 (98.7%) |

| Other | 11 (1.6%) | 8 (1.1%) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.3%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| English the first language | ||

| Yes | 681 (96.9%) | 674 (95.7%) |

| No | 11 (1.6%) | 16 (2.3%) |

| Unknown | 11 (1.6%) | 14 (2.0%) |

| Employment status | ||

| In paid employment | 372 (52.9%) | 368 (52.3%) |

| Unemployed | 70 (10.0%) | 71 (10.1%) |

| Looking after the home | 53 (7.5%) | 51 (7.2%) |

| Retired | 144 (20.5%) | 142 (20.2%) |

| Full‐time student | 9 (1.2%) | 8 (1.1%) |

| Other | 55 (7.8%) | 64 (9.1%) |

| Education level | ||

| Degree or equivalent | 109 (15.5%) | 105 (14.9%) |

| A ‐level or equivalent | 123 (17.5%) | 115 (16.3%) |

| GCSE or equivalent | 246 (35.0%) | 234 (33.2%) |

| None | 129 (18.3%) | 153 (21.7%) |

| Other/unknown | 99 (14.1%) | 94 (13.3%) |

| Free prescription | ||

| Yes | 400 (56.9%) | 392 (55.7%) |

| No | 298 (42.4%) | 299 ((42.5%) |

| Unknown | 5 (0.7%) | 13 (1.8%) |

| Cigarettes per day before quitting, mean (SD) | 19.9 (9.5) | 20.4 (10.2) |

| First cigarette after waking up within 5 minutes | 295/702 (42.0%) | 298/703 (42.4%) |

| Any previous quit attempts | 625/702 (89.0%) | 629/704 (89.4%) |

GCSE = General Certificate of Secondary Education; SD = standard deviation.

Smoking relapse results

The proportion of prolonged, CO‐verified smoking abstinence from 4 to 12 months was 36.9% in the intervention group and 38.6% in the control group (Table 2), and the difference between the groups was statistically non‐significant (P = 0.524). In addition, there were no statistically significant differences in any of secondary smoking outcomes, such as 7‐day self‐reported smoking at the 3‐ and 12‐month follow‐ups, and CO‐verified smoking abstinence at 12 months (Table 2).

Table 2.

Smoking relapse results—mixed‐effects logistic regression analysis.

| End‐point | Intervention event/n (%) | Control event/n (%) | Mixed‐effects odds ratio (95% CI); P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking abstinence | |||

| Primary outcome: prolonged abstinence from 4–12 months (CO‐validated at 12 months) | 259/702 (36.9%) | 271/702 (38.6%) | 0.93 (0.75, 1.16); P = 0.524 |

| CO‐validated 7‐day smoking abstinence at 12 months | 309/702 (44.0%) | 305/702 (43.4%) | 1.02 (0.83, 1.27); P = 0.804 |

| Smoking relapse | |||

| 7‐day self‐reported smoking at 3 months | 145/703 (20.6%) | 147/704 (20.9%) | 0.98 (0.76, 1.27); P = 0.903 |

| 7 day self–reported smoking at 12 months | 342/702 (48.7%) | 337/702 (48.0%) | 1.03 (0.83, 1.27); P = 0.789 |

None of the likelihood‐ratio tests comparing the mixed‐effects model to fixed‐effect logistic regression was statistically significant. CI = confidence interval; CO = carbon monoxide.

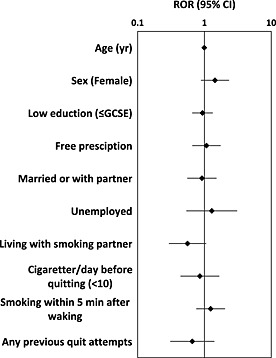

Results of mixed‐effects analysis after adjusting for multiple baseline variables are presented in Table 3. Similar to the unadjusted result, the adjusted difference between the treatment and control group in prolonged abstinence from 4 to 12 months was statistically non‐significant (P = 0.597). The results in Table 3 also reveal that a higher smoking abstinence at 12 months was associated with age, married or living with a partner, fewer than 10 cigarettes per day before quitting, first cigarette at least 5 minutes after waking up and cessation support from specialist advisers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of multivariable, mixed‐effects regression analysis.

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment versus control | 0.94 (0.74, 1.19) | 0.597 |

| Age (years) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 0.006 |

| Sex: female versus male | 0.94 (0.73, 1.21) | 0.626 |

| Married or living with a partner versus all other | 1.50 (1.15, 1.96) | 0.003 |

| Education up to GCSE versus A‐level or above | 0.94 (0.73, 1.22) | 0.656 |

| Unemployed versus all other | 0.67 (0.43, 1.06) | 0.090 |

| Free prescription versus no free prescription | 0.93 (0.71, 1.23) | 0.626 |

| Living with a smoking partner versus not | 0.82 (0.59, 1.14) | 0.231 |

| Cigarettes per day before quitting: <10 versus ≥10 | 1.73 (1.22, 2.44) | 0.002 |

| First cigarette within 5 minutes after waking versus ≥ 5 minutes | 0.77 (0.60, 0.99) | 0.046 |

| Any previous quit attempts vs. no previous quit attempts | 0.72 (0.45, 1.14) | 0.161 |

| Longest time managed to quit before: > 4 weeks versus ≤ 4 weeks | 0.89 (0.64, 1.23) | 0.483 |

| Specialist service versus non‐specialist service | 1.46 (1.09, 1.97) | 0.012 |

Prolonged smoking abstinence was the dependent variable, and multiple baseline characteristics as independent variables. Odds ratio > 1 indicates that a variable is associated with a higher rate of smoking abstinence. GCSE = General Certificate of Secondary Education; CI = confidence interval.

According to the results of treatment–interaction analyses, the treatment effect did not differ significantly by participant characteristics at baseline (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Results of exploratory, mixed‐effects logistic regression analyses of interactions between treatment effect and baseline variables

Process and mediating variables

The proportion of participants who reported receiving and still possessing the booklets was statistically significantly higher in the treatment group than in the control group (Table 4). More participants in the intervention group reported that they knew more about situations that might lead to relapse than those in the control group at the 3‐month follow‐up (52 versus 46%; P = 0.04), although the difference between the groups disappeared at the 12‐month follow‐up (52 versus 51%). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in the proportion of participants reporting that they knew more about ways of handling urges or knew at least one thing that could be done to handle urges. Approximately 83% of all participants by 3 months, and 60% between 4 and 12 months, reported enacting a strategy to handle urges to smoke, with no significant differences between groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparisons of process and mediating variables between the groups.

| Intervention group | Control group | P‐value a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of participants | |||

| At 3 months | 703 | 704 | |

| At 12 months | 702 | 702 | |

| Booklets received at 3 months | 628 (89.3%) | 554 (78.7%) | P < 0.001 |

| Still had booklets/leaflet at follow‐up | |||

| At 3 months | 580 (82.5%) | 437 (62.1%) | P < 0.001 |

| At 12 months | 343 (48.9%) | 242 (34.5%) | P < 0.001 |

| Had read the booklets/leaflet (reported at follow‐up) | |||

| 2–3 months | 495 (70.4%) | 485 (68.9%) | P = 0.535 |

| 4–12 months | 189 (26.9%) | 144 (20.5%) | P = 0.005 |

| Knew more about relapse‐risky situations (reported at the follow‐up) | |||

| At 3 months | 368 (52.3%) | 330 (45.9%) | P = 0.040 |

| At 12 months | 362 (51.6%) | 361 (51.4%) | P = 0.957 |

| Knew more about ways of handling urges (reported at the follow‐up) | |||

| At 3 months | 361 (51.3%) | 193 (47.0%) | P = 0.104 |

| At 12 months | 358 (51.0%) | 356 (50.7%) | P = 0.915 |

| Knew at least one thing that could be done to handle urges | |||

| At 3 months | 608 (86.5%) | 611 (86.8%) | P = 0.867 |

| At 12 months | 447 (63.7%) | 460 (65.5%) | P = 0.468 |

| Ever attempted to do something to cope with urges | |||

| At 3 months | 580 (82.5%) | 585 (83.1%) | P = 0.768 |

| At 12 months | 420 (59.8%) | 431 (61.4%) | P = 0.548 |

Pearson's χ2 test.

Results of exploratory mixed‐effects logistic regression analyses to investigate the association between prolonged smoking abstinence and potential mediating variables are presented in Table 5. Smoking abstinence was more common in people who had read the booklets by 3 months compared with those who did not (P < 0.001), although there was no significant association between smoking abstinence and booklet‐reading between 4 and 12 months (P = 0.546). Prolonged smoking abstinence was higher in participants who reported knowing more about risky situations or about ways to handle urges. Participants who reported doing something to handle urges to smoke were less likely to relapse by 12 months than were people who had no strategy to cope with urges (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association between smoking abstinence 4–12 months and mediating variables—results of mixed‐effects univariable regression analyses.

| Odds ratio of smoking abstinence (95% CI); P‐value | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2–3 months | 4–12 months | |

| Any reading of booklets or leaflet | 1.62 (1.27, 2.07); P < 0.001 | 1.08 (0.84, 1.39); P = 0.546 |

| Know more about risky situations | 1.19 (1.04, 1.36); P = 0.012 | 1.48 (1.30, 1.69); P < 0.001 |

| Know more about ways of handling urges | 1.15 (1.00, 1.31); P = 0.045 | 1.46 (1.28, 1.67); P < 0.001 |

| Ever tried to do something to handle urges | 1.72 (1.25, 2.38); P = 0.001 | 3.11 (2.44, 3.95); P < 0.001 |

Odds ratio > 1 indicates that a variable is associated with a higher rate of smoking abstinence.

Figure 3 shows that the proportion of prolonged smoking abstinence was lowest among participants who reported no attempt to control urges at all (19%) and highest among participants who had attempted to control urges by both the 3‐ and 12 month follow‐ups (48%). Participants who reported any attempts only by the 3‐month follow‐up had a smoking abstinence rate (24%) slightly higher than those who reported no attempts at all (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Proportion of prolonged smoking abstinence from 4 to 12 months by attempts to do something to handle urges to smoke

Discussion

Recent quitters who were sent the eight revised Forever Free booklets were no more likely to remain abstinent from smoking by 12 months than people who were sent a brief leaflet. In addition, there was no evidence that people in the intervention group developed more coping skills for preventing smoking relapse compared with those in the control group.

Findings from previous systematic reviews indicated that self‐help booklets were effective for preventing smoking relapse in unaided quitters 8, 9. However, results from the current trial indicate that the full set of Forever Free booklets was no more effective than a single leaflet in short‐term quitters who received intensive behavioural support to stop smoking. It is worth considering possible explanations for the different findings in the present study compared to previous studies using a very similar intervention 20, 21. The most important reason may be the difference in smoking cessation treatment received by study participants. The booklets were developed originally to help self‐quitters instead of more intensive face‐to‐face counselling. In contrast, the present study used the booklets as an extension of an intensive intervention provided by the NHS stop smoking clinics. Participants had received behavioural support from smoking cessation advisers before participating in the trial. Therefore, it is very likely that they had received information from other sources similar to that in the Forever Free booklets.

There may be other reasons for the null result of the current study. For example, the efficacy of the Forever Free booklets may be affected by cultural differences between the UK and US quitters, even though the booklets were revised in order to make them more suitable to British users. Finally, it is important to note that most participants relapsed and many failed to use strategies to cope with urges to smoke. This indicates that both intensive behavioural sessions and the self‐help booklets combined did not give many smokers sufficient skills to prevent relapse.

Generalizability

Fewer than 20% of people who were approached to participate declined and, furthermore, there was no evidence that the effect of the booklets was modified by participant characteristics. As is typical of smoking cessation studies in countries with mature smoking epidemics, the population had relatively low educational attainment and were more dependent on cigarettes than the general population of smokers. This suggests that the results apply to most people who stop smoking successfully with the aid of behavioural support and medication. We did not include pregnant women, as the process of return to smoking after pregnancy is often different from other smokers, so the results may not apply to them.

Strengths and limitations

This large trial recruited to target and therefore provided good precision to exclude the kind of effect seen in previous studies. Follow‐up of smokers is always challenging, because many relapsed participants are not willing to declare this, but we achieved a higher follow‐up rate (86%). We imputed as smokers those who were not prepared to be followed‐up, and the evidence suggests that this is a valid assumption in this context 18. Participant allocation was concealed adequately and the main characteristics of participants were well balanced at baseline.

As with other behavioural interventions, it was difficult to blind participants and investigators to allocation for follow‐up. Lack of blinding is unlikely to influence the objectively measured primary outcome 22, although bias could be introduced in the self‐reported measurement of process variables such as reported receiving and reading of booklets. Possible recall bias is unlikely to be a major concern for the validity of estimated treatment effect, but it could affect analyses of process and mediating variables. Readers should note that a large number of exploratory analyses were conducted in this study. Any apparent differences between arms that emerged are hypothesis‐generating and not confirmatory.

Interpretation and implications

The proportion of participants that recalled having received and the proportions who reported reading the booklets were slightly higher in the experimental group than in the control group. However, there were no differences in the proportion of participants who reported that they knew more about coping skills, and no differences in reported actual strategies to handle smoking urges, between the trial groups. The intervention booklets provided detailed training on how to cope with urges to smoke and other risky situations, but were clearly ineffective at providing this learning.

According to a within‐trial economic evaluation from the perspective of the NHS and personal social services (PSS), the estimated costs of the use of the experimental booklets was £20.78 per participants, compared to £0.67 per participants for the use of the control leaflet, and the provision of the intervention booklets would not constitute a cost‐effective use of health‐care resources 12.

In agreement with evidence from previous studies 23, 24, reported attempts by participants to do something to cope with urges to smoke were associated with a lower risk of smoking relapse. Results of the exploratory analyses (Fig. 3) revealed that the proportion of smoking abstinence from months 4 to 12 was lowest among participants who reported no strategies at all (19%), and highest among participants who attempted strategies at both the 3‐ and 12‐month follow‐ups (48%). Further research needs to focus upon identifying successful strategies of behavioural interventions to improve continued efforts by quitters to cope with urges to smoke.

In conclusion, a full set of the revised Forever Free booklets was found not to provide additional benefit to short‐term quitters who had received intensive behavioural intervention, compared with a single leaflet containing a similar but briefer message for smoking relapse prevention.

Clinical trial registration

The trial was prospectively registered (Current Controlled Trials, ISRCTN36980856).

Declaration of interests

P.A. has conducted ad‐hoc consultancy and research for the pharmaceutical industry on smoking cessation. T.H.B. has received research funding and study medication from Pfizer, Inc. No other competing interests declared; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Contents of self‐help educational materials investigated in the study.

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme (Project 09/91/36). Visit the HTA programme website for more details www.hta.ac.uk/link to project page. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health. We acknowledge the support of the National Institute for Health Research, through the Primary Care Research Network. P.A. is funded by an NIHR award and the UK Centre for Tobacco Control Studies (a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence) and received funding from British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council and the Department of Health. We thank staff from NHS Norfolk and Norfolk Community Health and Care NHS Trust for providing advice on the development of the trial protocol. We thank stop smoking advisers from NHS stop smoking services in Norfolk, Lincolnshire, Suffolk, Hertfordshire, Great Yarmouth and Waveney for recruiting quitters to the study. The trial was conducted in collaboration with the Norwich Clinical Trials Unit, whose staff provided input into the design, conduct and analysis (Tony Dyer: randomization and data management, Garry Barton: health economics). We thank Laura Vincent for providing administrative support, data entering and data checking.

Maskrey, V. , Blyth, A. , Brown, T. J. , Barton, G. R. , Notley, C. , Aveyard, P. , Holland, R. , Bachmann, M. O. , Sutton, S. , Leonardi‐Bee, Jo. , Brandon, T. H. , and Song, F. (2015) Self‐help educational booklets for the prevention of smoking relapse following smoking cessation treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 110: 2006–2014. doi: 10.1111/add.13080.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO) WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2013. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giovino G. A., Mirza S. A., Samet J. M., Gupta P. C., Jarvis M. J., Bhala N. et al. Tobacco use in 3 billion individuals from 16 countries: an analysis of nationally representative cross‐sectional household surveys. Lancet 2012; 380: 668–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jha P., Peto R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 60–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zwar N. A., Mendelsohn C. P., Richmond R. L. Supporting smoking cessation. BMJ 2014; 348: f7535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferguson J., Bauld L., Chesterman J., Judge K. The English smoking treatment services: one‐year outcomes. Addiction 2005; 100: 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marlatt G. A., Gordon J. R. Determinants of relapse: implications for the maintenance of behavior change In: Davidson P., Davidson S., editors. Behavioral Medicine: Changing Health Lifestyles. New York:: Brunner/Mazel; 1980, pp. 410–52. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hajek P., Stead L. F., West R., Jarvis M., Hartmann‐Boyce J., Lancaster T. Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 8:CD003999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Agboola S., McNeill A., Coleman T., Leonardi‐Bee J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of smoking relapse prevention interventions for abstinent smokers. Addiction 2010; 105: 1362–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Song F., Huttunen‐Lenz M., Holland R. Effectiveness of complex psycho‐educational interventions for smoking relapse prevention: an exploratory meta‐analysis. J Public Health (Oxf) 2010; 32: 350–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hartmann‐Boyce J., Lancaster T., Stead L. F. Print‐based self‐help interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 6:CD001118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coleman T., Agboola S., Leonardi‐Bee J., Taylor M., McEwen A., McNeil A. Relapse prevention in UK Stop Smoking Services: current practice, systematic reviews of effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess 2010; 14: iii–iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blyth A., Maskrey V., Notley C., Barton G. R., Brown J. T., Aveyard P. et al Effectiveness and economic evaluation of self-help educational materials for the prevention of smoking relapse: randomised controlled trial. Health Technology Assessment 2015; 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Song F., Holland R., Barton G. R., Bachmann M. O., Blyth A., Maskrey V. et al. Self‐help materials for the prevention of smoking relapse: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2012; 13: 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Department of Health NHS Stop Smoking Services: Service and Monitoring Guidance 2010/11. London: Department of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15. West R., May S., West M., Croghan E., McEwen A. Performance of English stop smoking services in first 10 years: analysis of service monitoring data. BMJ 2013; 347: f4921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Armitage P., Berry G. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moffitt Cancer Center . Moffitt Cancer Center Original Forever Free®: A Guide to Remaining Smoke Free. Tampa, FL: Moffitt Cancer Center; [This is the original set of 8 booklets designed to prevent smoking relapse among individuals who have recently attempted to quit smoking.]; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18. West R., Hajek P., Stead L., Stapleton J. Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction 2005; 100: 299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mackinnon D. P., Fairchild A. J. Current directions in mediation analysis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2009; 18: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brandon T. H., Collins B. N., Juliano L. M., Lazev A. B. Preventing relapse among former smokers: a comparison of minimal interventions through telephone and mail. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68: 103–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brandon T. H., Meade C. D., Herzog T. A., Chirikos T. N., Webb M. S., Cantor A. B. Efficacy and cost‐effectiveness of a minimal intervention to prevent smoking relapse: dismantling the effects of amount of content versus contact. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004; 72: 797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wood L., Egger M., Gluud L. L., Schulz K. F., Juni P., Altman D. G. et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta‐epidemiological study. BMJ 2008; 336: 601–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Curry S. J., McBride C. M. Relapse prevention for smoking cessation: review and evaluation of concepts and interventions. Annu Rev Public Health 1994; 15: 345–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Connell K. A., Hosein V. L., Schwartz J. E. Thinking and/or doing as strategies for resisting smoking. Res Nurs Health 2006; 29: 533–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Contents of self‐help educational materials investigated in the study.

Supporting info item