Abstract

Introduction: Public health approaches to end-of-life (EoL) research and care are relatively rare in Sweden, and health-promoting palliative care (HPPC) remains a foreign concept for most. We recently consolidated our HPPC endeavors into a cohesive research program, DöBra, to promote constructive change and awareness to support better quality of life and death among the general population, in specific sub-groups, and in interventions directed to professional groups caring for dying individuals, their friends and families.

Objectives: In this article, we aim to share ideas, experiences, and reflections from the early stages of this research program, particularly in relation to how we try to work with new ‘publics’, to contribute to the development of HPPC as a new research field.

Methods and Results: We discuss some considerations which arise in the Swedish context, and present the underlying ideas and approaches used in the research program, with examples of their application. HPPC, based on ideas from new public health, is essential as an umbrella for the DöBra program. Action research, experience-based co-design, and knowledge exchange, all aim to bring together a variety of stakeholders to exchange ideas and expertise, and co-create experience-based evidence through knowledge generation, dissemination, and sharing.

Discussion: In reflecting on what we have learned about publics and partnerships in EoL research to date, we question distinctions made between professionals and publics, concluding that including publics in public health research, means also including ourselves and making public many of the reflections, the mistakes, and the experiences we all have, to foster collective learning.

Keywords: Action research, End-of-life research, Experience-based co-design, Health-promoting palliative care, Knowledge exchange, Palliative care, Public health

Although cancer-related specialized palliative care and research (PC) has developed rapidly in Sweden in recent decades, these achievements have not benefited large portions of the population to date. Public health approaches to end-of-life (EoL) research and care are relatively rare in Sweden, and health-promoting palliative care (HPPC)1 remains a foreign concept for most. The authors, with long backgrounds in PC practice/research, recently received national competitive funding to consolidate our work in HPPC into a cohesive research program, DöBra,2 aiming to promote constructive change and awareness of the numerous choices which can support better quality of life and death among the general population, in specific sub-groups, and in interventions directed to professional groups caring for dying individuals, their friends and families. By sharing our ideas, experiences, and reflections from the early stages of the DöBra program, particularly in relation to how we try to work with new ‘publics’, we hope to contribute to the development of HPPC as an emerging and dynamic field of research.

The Swedish context

Approximately 1% (∼90 000 people) of the population in Sweden die each year.3 While 90% of patients in specialized PC have cancer, 25% of deaths in Sweden are cancer related, and <10% of all deaths occur while enrolled in specialist PC.3,4 The vast majority of deaths are not sudden, with an average of 42% of all deaths occurring in acute care hospitals and 38% in residential living facilities for the elderly.5 The situation in both types of facilities share similarities with many other Western countries, with staff often receiving less support to deal with issues of death/dying,6–9 and numerous challenges to providing quality EoL care, especially in comparison with specialized PC. The availability of specialized PC in Sweden is regionally biased, and is generally more available to urban populations than in rural and remote areas, which are quite extensive. For example, the geographic northern half of the country is populated by ∼10% of the population.

While several of these features are common to many countries, others maybe more unique to Sweden. The Swedish healthcare system is based on principles of equal access to care, is almost exclusively full coverage and tax-based with low out-of-pocket costs for care recipients, and organized by geographic region rather than nationally. Healthcare is primarily provided by the public sector, although in-patient hospices and PC facilities are in many cases notable exceptions, with most run by nonprofit foundations; for the most part, out-of-pocket costs do not differ from those in public care facilities. Palliative home care is the dominant form of specialized PC, and with a few exceptions, provided by the public healthcare system.

Context also has linguistic implications, as we are not working in English; for example, the Swedish language has no direct translation for ‘community’, with terms often related to organizational structures rather than ‘sense of community’, nor is there a word for ‘empowerment’. While this may hinder easy communication to some extent when discussing HPPC, it also has positive aspects in removing the possibility of relying on buzz words that are common in other settings. These terms are often used directly in English in academic settings; however we feel this is neither appropriate nor feasible when in communicating with a general public.

The role of the general public also differs from many other countries in that volunteers play a relatively limited role in healthcare provision in general and in palliative and EoL care in particular,10,11 although unpaid engagement is common in other sectors of Swedish society. One implication of this is that there is little tradition of engaging the public in EoL issues. This may be reflected in the results of our 2014 survey assessing familiarity with and awareness of PC among the general population in Sweden (n = 2012), replicating a survey conducted in Northern Ireland.12 Over 40% of respondents reported having no awareness of what PC is; this compares poorly to the 19% in Northern Ireland.12 As in Northern Ireland, the vast majority of responses to an open question about what hinders the general public from being more aware of issues related to PC focused on fear and resistance to issues related to death and dying. This avoidance was said to be supported by a lack of information and avoidance in Swedish society in general, as well as within the healthcare system. Here again, we consider the impact of language: we replicated use of the term ‘palliative care’ when translating the survey, but have since considered its implications. Has acceptance of the professional/policy-driven, changing societal trend to use this broader term instead more directly referring to ‘EOL care’ specifically, acted as a euphemism in the Swedish context which might confuse rather than stimulate discussion? This was yet one further experience that served to make us more conscious of the importance of the words we chose to use in the DöBra program.

The DöBra program

After many years of working within the traditional PC world, about 10 years ago we began to increasingly question our own roles and the limitations of specialized PC in Sweden. We saw a need to update and re-conceptualize ways of reaching populations of interest – a variety of publics beyond those receiving care. We were interested in finding locally relevant means of working to improve EoL care, and recognized a need to find innovative forms of contact with individuals and community groups, as well as inter- and transdisciplinary collaboration to achieve this. Triggered by our contact with LaTrobe University and early HPPC initiatives in Wangaratta, Australia,13,14 we recognized that there was substantial international experience which we needed to capitalize on and test for relevance in Sweden. However, we were also aware that we needed to develop situation and culturally specific initiatives, with flexibility to adapt to different contexts across Sweden, if we were to support community capacity related to EoL issues. The quest for major funding as well as creating the program was a long and winding road, taking nearly five years.

After several years of fragmented funding for different projects, the DöBra research program was first financed as such through a one-year grant in 2013, aiming to reframe traditional forms of research dissemination to be more interactive, reciprocal, and participatory.15 We thereafter successfully sought a four-year programmatic research grant from the same national funders.16

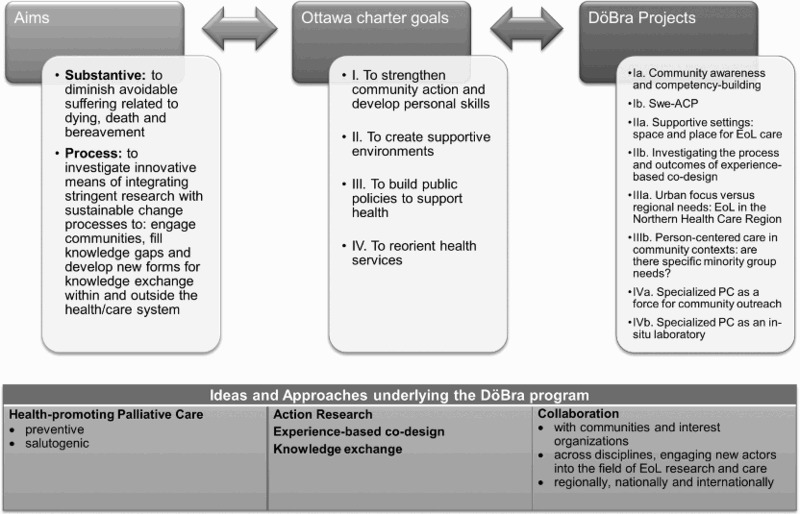

The DöBra program enjoins various projects sharing the overarching substantive aim of working to diminish avoidable suffering related to dying, death, and bereavement, and is graphically depicted in Fig. 1. We also focus on process, aiming to investigate innovative means of integrating stringent research with sustainable change processes to engage communities, fill knowledge gaps, and develop new forms for knowledge exchange (KE) within and outside the health and social care (health/care) systems.

Figure 1 .

Graphic representation of DöBra program, as conceptualized in most recent grant application.

DöBra builds on our existing national and international collaborations, linking universities and PC facilities across Sweden, separated by over 1500 km. The interdisciplinary program team, large at the onset, has now grown to include individuals from six different patient, family, and retired people's associations, as well as researchers and advisors representing ethnology, ethics, healthcare innovation & policy, IT, medical management, PC research and practice (nurses, physicians), social policy, sociology, social/pastoral theology, and design disciplines, including architecture, experience design, and arts. We have research access to specialized PC inpatient and home care facilities, as well as acute care hospitals and residential care facilities for elderly; the specialized facilities with best resources function as ‘test sites’ to develop and trial initiatives – processes or prototypes – that can then be disseminated further. We are attempting to heighten national relevance by including large urban centers, smaller towns, and rural and remote areas.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, we operationalized our general aims into four combined goals in line with the five delineated in the WHO's Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion from 198617 which marked the beginning of the era of new public health.18 A series of projects in DöBra are directed toward achieving these goals. The process and outcomes of the Ottawa Charter have been criticized on numerous points, from impotency in carrying out its aims, to being developed through a process that contradicted its goals.19,20 However, while this problematization and critical discourse has heightened our awareness of the need for consistency in how we talk and how we act, we found the Ottawa Charter to be a cogent tool for organizing our thoughts and explaining our vision and direction in various forums.

Ideas and approaches underlying the DöBra program

The different ideas and approaches we utilize in DöBra share characteristics, in addressing different ways to engage a variety of publics in HPPC endeavors. We see HPPC as an umbrella, based on ideas from new public health, essential to the DöBra program. Action research (AR), experience-based co-design (EBCD) and KE, all aim to bring together a variety of stakeholders to exchange ideas and expertise, and co-create experience-based evidence through knowledge generation, dissemination, and sharing.

For us, adopting ideas and approaches from HPPC has involved a major step from our clinical backgrounds. We make efforts to work salutogenically (i.e. focusing on what supports positive outcomes21,22) rather than focusing on problems, based on a preventive rather than reactive focus, to maximize health and minimize distress in relation to death-related issues. We have found that ideas originating from ‘asset-based community development’. 23,24 offer both theoretical inspiration and concrete strategies as a means of moving from needs-based approaches to those more in line with a salutogenic approach. Asset-based community development includes approaches which utilize strengths, resources, and capacities in transformative processes. We are trying to apply these principles in our work, in program governance, and in specific projects. For example, in a first general program meeting in May 2015, we brought together 25 participants in the program with varied backgrounds, from members of community organizations through students through professors, using exercises to stimulate interaction while trying to avoid privileging particular forms of knowledge. This had several aims: to build relationships, to find synergies among projects and people, and to jointly discuss visions, ways of working and outputs in working together as a basis for formulating terms of reference for the program.

AR has been described as research ‘with people’, rather than ‘on’ or ‘for people’ – referring to all stakeholders, potential users, or benefactors25,26 and thus may be seen as another way of acting out the visions of the Ottawa Charter in research endeavors. Basic features of AR include a dynamic and cyclic process of problem identification, planning, action, and evaluation which incrementally changes and builds further based on lessons learned, in partnership between researchers and other stakeholders.27 Characteristics of AR include defining, interpreting, and explaining social situations; incorporating change interventions aimed at improvement; being context specific and future oriented as well as educative and empowering; using reflection to learn; utilizing a variety of methods to include both practical and theoretical knowledge; and having potential to examine existing theories and generate new ones from practice.27

AR is intrinsic to DöBra. One example of its application is in the development of a first advance care planning (ACP) program in Sweden (see Fig. 1, Ib Swe-ACP), inspired by approaches used in an earlier Australian project, entrust-u.28 The project group is comprised of a combination of researchers with different backgrounds and members of community organizations, who have met regularly for several years to detail plan the project and adapt tools to the Swedish context. This drawn-out process was an inadvertent consequence of unclear funding for the future, but the timeframe has proven to have untold beneficial effects. We have gotten to know one another and are developing a sense of trust and humor in the process of trial and error in adapting GoWish cards29 and Ecomapping30 for use in ACP in Sweden. The extended timeframe also provided opportunity to have extensive discussions about how best to tailor the project to the different situations of the individual members of organizations with very different profiles, while maintaining some common structure. In the Swedish context, where ‘patient and public involvement’ is not a given, we had no praxis to follow, but had to find new ways of working together in this constellation.

EBCD, based on work by Bate and Robert,31,32 focuses on utilizing participatory action-oriented processes to accomplish change in the health care system, building on design thinking. Bate and Robert challenge traditional mindsets which place patients in a passive role based on listening and responding to ideas generated by others, arguing that proactive influence which instead challenges this hierarchy is a key to change. They emphasize that the experience goals of users need to be at the center of design of all types of health care processes and settings, with status equal to other organizational and clinical goals. The EBCD approach uses a range of methods to co-produce knowledge based on the experiences of health/care users, which is then applied to redesign processes for improved usability in terms of how interactions with products or services are experienced.

When we first encountered EBCD, it had been used in >60 health services internationally,33,34 but had not been applied in PC, aside from then ongoing trial to improve care for elderly patients with palliative needs in a UK emergency room (Blackwell & Robert, personal communication, Feb. 2015). We had begun to work with designers, but felt a need to find a structured way to implement design thinking; this led to our present use of a form of accelerated EBCD.35 This is being trialed in our work on supportive care environments for EoL care (Fig. 1, IIa Supportive settings: Space and Place for EoL care), where we use photographs from an earlier project, taken by patients, staff, and family members, and depicting features of different EoL care environments they find important. These photographs, along with interview quotes have been compiled into ‘trigger films’ which will be used to stimulate discussion and reflection in a series of workshops bringing patients, family, and staff together this autumn to determine priorities for change. This is intended to lead to co-design work in small groups formed around the identified priorities. We collaborate with an external evaluator who observes our processes to help us understand our failures and successes, and how we can improve and adapt EBCD or other forms of co-design, for application outside health/care systems. While Bate and Robert focus on change within systems, therefore referring to patients, we believe that EBCD or other forms of co-design can offer new ways of thinking and reaching new publics in HPPC.

With KE, we take exception to a unilateral process of research dissemination to instead adopt a multidirectional process uniting different stakeholders, groups and communities for the exchange of different and complementary ideas, evidence and expertise. KE includes ‘generating, sharing, and/or using knowledge through various methods appropriate to the context, purpose, and participants involved.’36 (p.20) KE also aims to contribute to societal change, in line with recent ideas on the need for transformative learning in health care.37 In their review, Fazey et al.36 emphasize the importance and challenges of finding means to study KE and other participatory initiatives, and structure useful points to support this.

Instead of conceptualizing the general public as ‘uninformed’ or ‘misinformed’ and professionals as ‘knowledge bearers’, as is so often the case in professionally driven and problem-oriented research, we work on the assumption that issues related to death and dying are experienced by us all, with experience-based knowledge a mainstay in the DöBra program, regardless of the actor. One example of how this was actualized early in developing DöBra, was our participation in the Room for Death project, which teamed artists and craftspeople together to create prototypes of space for difficult conversations in EoL settings. These prototypes were presented in a museum exhibition, where we contributed a question to explore reflections of the public viewing the exhibition: ‘How would you like it to be around you when you are dying?’ Written responses from over 500 visitors from 46 countries allowed us to distinguish different foci in conceptualizing preferences for EoL surroundings, something we know all too little about. While these data do not give clear answers as to how EoL care should be organized or provided, they raise numerous issues for our consideration, and from the responses, clearly have also stimulated reflection among the museum visitors.38

Some final reflections

Writing this article has provided occasion for us to reflect and take inventory of where we are in a process and what we have learned about publics and partnerships in EoL research through it. Perhaps the most salient lesson is that we repeatedly have had reason to question conceptualizations of ‘we’ and ‘them’, the professionals and the public, even in public health research. We have so clearly been reminded that there is no public out there, we are all the public. This has been brought home to us by the stories, engagement and interest of the people we encounter and by sicknesses and deaths among our own families and friends as we plan and conduct DöBra. We have once again had to revisit and rethink many of the professional assumptions we have been schooled into, with implications ranging from basic ontological to personal and professional levels. The need for continued critical distance to avoid replacing ‘old assumptions’ with new ones, and maintain scientific stringency has been essential.

We have also found we need to make all effort to lead DöBra with a process of governance based on the same principles of involvement, dialogue and co-creation as those we espouse in relation to the substantive outcomes we hope to achieve in relation to EoL issues. It has taken us time to recognize that our open, sometimes heated dialogues and critical discussions are a form of social capital and trust, which can be at least as important as quick action.

We have consciously brought together a diverse group in DöBra, with different types of knowledge, skills, resources, and perspectives which we are convinced can enrich HPPC. However even if our intention was to quickly move to action, the cloud of the involuntary delay related to funding the program has turned out to have an unexpected silver lining. Establishing trust and getting to know our individual and collective strengths and limits, and how we can complement each other takes time and effort. We are still beginning to understand how our strengths and resources can be creatively combined to reach a wide variety of publics and potentials.

In short, including publics in public health research, means including ourselves and making public many of the reflections, the mistakes, and the experiences we all have, to foster collective learning.

Footnotes

HPPC originated with the work of Allan Kellehear, a sociologist from Australia, in response to an increasingly acknowledged need to complement the individually-based remit of specialist PC,(e.g. 1,2 ) and is discussed in depth elsewhere.

In Swedish, DöBra is a play on words, literally meaning ’Dying Well’, but also an idiom roughly equivalent to ’awesome’ in English.

References

- Kellehear A. Health promoting palliative care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kellehear A. Compassionate cities: Public health and end-of-life care. London: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. Causes of death 2014. Statistics – health and medical care. 2015 August [cited 2015 August 28]. Available from: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2015/2015-8-1

- The Swedish Register of Palliative Care. Svenska palliativregistrets årsrapport för år 2014 [Annual review for 2014, in Swedish]. 2015 [cited 2015 August 28]. Available from: http://palliativ.se/?p=875

- Håkanson C, Öhlén J, Morin L, Cohen J. A population-level study of place of death and associated factors in Sweden. Scand J Public Health. 2015;43(7):744–51. doi: 10.1177/1403494815595774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck I, Tornquist A, Brostrom L, Edberg AK. Having to focus on doing rather than being-nurse assistants’ experience of palliative care in municipal residential care settings. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(4):455–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson JB, Hallett CE, Luker KA. Everyday death: how do nurses cope with caring for dying people in hospital? Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42(2):125–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser-Jones J, Schell E, Lyons W, Kris AE, Chan J, Beard RL. Factors that influence end-of-life care in nursing homes: The physical environment, inadequate staffing, and lack of supervision. Gerontologist. 2003;43(Spec No 2):76–84. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrung Wallin A, Jakobsson U, Edberg AK. Job strain and stress of conscience among nurse assistants working in residential care. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23(3):368–79. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson B, Öhlén J. Being a hospice volunteer. Palliat Med. 2005;19(8):602–9. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm1083oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter S, Rasmussen BH. Volontärer i livets slutskede [Volunteering in end-of-life care] Omsorg – Nordisk tidsskrift for palliativ medisin. 2010;27(1):35–8. Swedish. [Google Scholar]

- McIlfatrick S, Hasson F, McLaughlin D, Johnston G, Roulston A, Rutherford L, et al. Public awareness and attitudes toward palliative care in Northern Ireland. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-12-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbold B. Public health approaches to palliative care in Australia. In: Sallnow L, Kumar S, Kellehear A, editors. International perspectives on public health and palliative care. New York: Routledge; 2012. pp. 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Salau S, Rumbold B, Young B. From concept to care: Enabling community care through a health promoting palliative care approach. Contemp Nurse. 2007;27(1):132–40. doi: 10.5172/conu.2007.27.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.forte.se/en/Grants-data-base/?arende=29254&item=Ref (2015 August 28)

- http://www.forte.se/en/Grants-data-base/?arende=33109 (2015 August 28)

- World Health Organization. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. 1986 November 21 [cited 2015 August 28]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/

- Kellehear A, Sallnow L. Public health and palliative care: An historical overview. In: Sallnow L, Kumar S, Kellehear A, editors. International perspectives on public health and palliative care. New York: Routledge; 2012. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- McPhail-Bell K, Fredericks B, Brough M. Beyond the accolades: A postcolonial critique of the foundations of the Ottawa Charter. Glob Health Promot. 2013;20(2):22–29. doi: 10.1177/1757975913490427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missoni E. Critical analysis of WHO's role in promoting health. 2006 November 21–23 [cited 2015 August 28] Available from: http://www.eduardomissoni.net/CV/mieiscrittipdf/061122%20-%20ISDE%20Firenze.pdf

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tishelman C. Critical reflections on the uncritical use of measuring instruments: Example Sense of Coherence questionnaire. Vard Nord Utveckl Forsk. 1996;16(1):33–37. doi: 10.1177/010740839601600107. discussion 38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis G, West D. Exploring the potential of social network analysis in asset-based community development practice and research. Australian Social Work. 2010;63(4):404–17. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2010.508167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathie A, Cunningham G. From clients to citizens: Asset-based community development as a strategy for community-driven development. Dev Pract. 2003;13(5):474–86. doi: 10.1080/0961452032000125857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J. Co-operative inquiry – research into the human condition. London: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Reason P, Bradbury H. Introduction: Inquiry and participation in search of a world worthy of human aspiration. In: Reason P, Bradbury H, editors. Handbook of action research – participative inquiry and practice. London: Sage; 2001. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman H, Tillen D, Dickson R, de Koning K. Action research: A systematic review and guidance for assessment. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(23):157. doi: 10.3310/hta5230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.entrust-u.org.au/ (2015 August 28)

- Menkin ES. Go wish: A tool for end-of-life care conversations. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(2):297–303. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray RA, Street AF. Ecomapping: An innovative research tool for nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50(5):545–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate P, Robert G. Experience-based design: From redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(5):307–10. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.016527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate P, Robert G. Bringing user experience to healthcare improvement. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Donetto S, Tsianakas V, Robert G. Using experience-based co-design to improve the quality of healthcare: Mapping where we are now and establishing future directions. London: King's College London; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Robert G, Cornwell J, Locock L, Purushotham A, Sturmey G, Gager M. Patients and staff as codesigners of healthcare services. BMJ. 2015;350:g7714. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locock L, Robert G, Boaz A, Vougioukalou S, Shuldham C, Fielden J, et al. Using a national archive of patient experience narratives to promote local patient-centered quality improvement: An ethnographic process evaluation of ‘accelerated’ experience-based co-design. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2014;19(4):200–7. doi: 10.1177/1355819614531565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazey I, Evely AC, Reed MS, Stringer LC, Kruijsen J, White PCL, et al. Knowledge exchange: a review and research agenda for environmental management. Environ Conserv. 2013;40(1):19–36. doi: 10.1017/S037689291200029X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist O, Tishelman C. Room for death – International museum-visitors’ preferences regarding the end of their life. Soc Sci Med. 2015;139:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]