Publisher's Note: There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

Our study has identified common genetic risk factors for VTE among AAs.

These risk factors are associated with decreased thrombomodulin gene expression, suggesting a mechanistic link.

Abstract

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the third most common life-threatening cardiovascular condition in the United States, with African Americans (AAs) having a 30% to 60% higher incidence compared with other ethnicities. The mechanisms underlying population differences in the risk of VTE are poorly understood. We conducted the first genome-wide association study in AAs, comprising 578 subjects, followed by replication of highly significant findings in an independent cohort of 159 AA subjects. Logistic regression was used to estimate the association between genetic variants and VTE risk. Through bioinformatics analysis of the top signals, we identified expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) in whole blood and investigated the messenger RNA expression differences in VTE cases and controls. We identified and replicated single-nucleotide polymorphisms on chromosome 20 (rs2144940, rs2567617, and rs1998081) that increased risk of VTE by 2.3-fold (P < 6 × 10−7). These risk variants were found in higher frequency among populations of African descent (>20%) compared with other ethnic groups (<10%). We demonstrate that SNPs on chromosome 20 are cis-eQTLs for thrombomodulin (THBD), and the expression of THBD is lower among VTE cases compared with controls (P = 9.87 × 10−6). We have identified novel polymorphisms associated with increased risk of VTE in AAs. These polymorphisms are predominantly found among populations of African descent and are associated with THBD gene expression. Our findings provide new molecular insight into a mechanism regulating VTE susceptibility and identify common genetic variants that increase the risk of VTE in AAs, a population disproportionately affected by this disease.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which encompasses deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a significant health problem in the United States, resulting in up to 600 000 new cases annually.1 In the United States, African Americans (AAs) exhibit the highest incidence of DVT and mortality rates of PE, having a 30% to 60% higher incidence compared with populations of European ancestry (EA) and a 74% higher incidence compared with Asian and Pacific Islander populations.2,3

A complex interplay between genetic and environmental risk factors results in VTE.4-7 Among these factors are deficiencies in protein C, protein S, and antithrombin, as well as elevated factor VIII and factor XI.4,5 Twin and family studies among populations of EA suggest that genetic factors explain up to 60% of VTE heritability.8,9 Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) in populations of EA have confirmed the 2 well-established risk variants, factor V Leiden (rs6025) and prothrombin G20210A (rs1799963), and have identified several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the ABO blood group gene (ABO) as susceptibility loci.10-12 However, these variants are found in higher frequencies among individuals of EA compared with AAs, particularly rs6025 and rs1799963 which are nearly absent in AAs. These studies suggest that genetic variation outside the well-established findings in EA populations may contribute to VTE risk in populations of African ancestry. To identify novel VTE susceptibility loci among AAs, we conducted a 2-stage analysis that included a GWAS in a discovery cohort, followed by examination of the most significant SNPs in an independent replication cohort. In addition, we validated the role of these variants in gene regulation through the integration of transcriptomic data sets.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Participants in the discovery and replication cohorts were unrelated, self-described as AA, and over the age of 18 years. Study participants provided a DNA sample (whole-blood, saliva, or mouthwash sample). Data collected on potential risk factors for VTE included age, height, weight, ethnicity, and sex. The research protocol was approved by the local institutional review boards, and study participants gave written informed consent. Cases had a documented history of VTE defined as proximal DVT or PE and without strong known risk factors, including prolonged hospitalization, surgery, active cancer or history of malignancy <5 years, pregnancy or puerperium, oral contraceptive use, menopausal replacement therapy, or protein C/S deficiency. VTE (DVT and/or PE) was diagnosed by physicians using different methods, including venous examination of the lower extremities using duplex ultrasound, spiral computed tomography, computed tomography pulmonary angiogram, or ventilation-perfusion scan. All cases were out-patients placed on warfarin as previously described.13 Control subjects were outpatients free of VTE. Control subjects with cancer, liver, or kidney disease/failure, arterial thrombotic disease, or risk factors for VTE (as described for cases) were excluded.

Discovery study population

The discovery cohort consisted of 146 VTE cases and 432 controls. VTE cases and a subset of the controls (n = 88) were obtained from two International Warfarin Pharmacogenetics Consortium (IWPC) sites: The University of Chicago and the University of Illinois at Chicago. Additional controls (n = 344) were obtained from the DC Prostate Cancer Study (DCPC) recruited at the Division of Urology at Howard University Hospital in Washington, DC.

Replication study population

For the replication cohort, 94 VTE cases and 65 controls were recruited from The University of Chicago, the University of Illinois at Chicago, The George Washington University Medical Faculty Associates, and the Veterans Affairs Hospital in Washington, DC. The replication cohort was independent of the discovery cohort.

Genotyping

For the discovery cohort, IWPC and DCPC subjects were genotyped using the Illumina 610 Quad BeadChip and the Illumina Infinium Human1M-Duo, respectively. Genotyping procedures for each data set have been previously described.13,14 For the replication cohort, genomic DNA was isolated from either whole-blood or buccal samples as described previously.15 Genotyping was conducted using the TaqMan allelic discrimination assay according to manufacturer’s instructions. To assess genotyping reproducibility, replicate samples were included, and the concordance was >98% for each SNP. The TaqMan assay for SNP rs62322307 failed these quality control measures and consequently was not analyzed.

Quality control

Because different genotyping platforms were used to generate the discovery cohort, each data set (IWPC and DCPC) underwent rigorous quality control filters individually and then as a merged data set. SNPs were excluded based on a genotyping rate <95%, a minor allele frequency of <0.03, and failed Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) tests P < .00001. SNPs on the X and Y chromosomes and mitochondrial SNPs were also excluded. Because different platforms may have distinct biases that could influence results, we took further measures to filter out errors arising from merging the IWPC and DCPC data sets, including SNPs that were not present in both data sets, SNPs that were A/T or C/G SNPs to eliminate flip-strand issues, or SNPs that were significantly (P < .05) missing between cases and controls. In addition, we performed a pseudo-GWAS between IWPC controls and DCPC controls and removed SNPs with an association P value of <10−5 (925 SNPs). After exclusion criteria, the final number of genome-wide genotyped SNPs for the discovery cohort was 514 419. Genome-wide genotype data were used to validate sex, as well as identity by descent. No sample had a call rate of <95%, missingness >0.10, sex misspecification, or identity by descent >0.125. For the replication cohort, SNPs were also excluded when the genotyping rate was <95% or failed HWE test P values were <.00001. All quality control procedures were conducted using PLINK.16

Global ancestry

Potential population stratification was examined by principal component analysis conducted through genome-wide complex trait analysis17 using a linkage disequilibrium (LD)-pruned (r2 >0.2) set of 149 606 markers (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site). Percentage West African ancestry was determined for each individual using ancestry-informative markers for European and West African ancestry.18 Individual ancestry estimates were obtained using the Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo method implemented in the program STRUCTURE 2.3.3.19

Imputation

Genotypes were phased using SHAPEIT and imputed with IMPUTE2 using reference files from the “1000 Genomes haplotypes–Phase I integrated variant set release (v3) in NCBI build 37 (hg19) coordinates.”20-22 SNPs were excluded if the minor allele frequency was <0.03, the imputation quality was <0.6, and the HWE P value was <.00001, resulting in 10 690 342 SNPs for analysis.

Statistical analysis

A quantile-quantile plot of expected and observed P values revealed no evidence for systematic genotype calling error, and the genomic inflation factor (based on median χ2) was1.00147, indicating sufficient control for possible population stratification (supplemental Figure 2). Covariates and the first 10 principal components were tested as single covariates for association with VTE risk using IBM SPSS Statistics version 19.0.0 package (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Sex was tested only among the IWPC subjects due to the DCPC data set comprising only males. The association of each SNP with risk of VTE for the discovery cohort was conducted using SNPTEST23 v2.5 and for the replication cohort using PLINK,16 adjusting for age. A P value <5.0 × 10−8 was considered significant. In the replication cohort, independent SNPs with a highly suggestive association to VTE risk (P < 5.0 × 10−7) were genotyped. The significance threshold was set at P < .016 (.05/3 SNPs); SNP rs1998081 was genotyped to confirm LD with rs2144940 and rs2567617. Results from the discovery and replication cohorts were meta-analyzed using the software METAL.24 Gene region plots of top SNPs were generated with LocusZoom.25

Thrombomodulin gene expression

We used the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Portal (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gtex/GTEX2/gtex.cgi) to retrieve precomputed significant cis and trans expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) from whole-blood tissue tested in 338 samples.26 To examine whether thrombomodulin (THBD) is differentially expressed between VTE patients and healthy controls, we used whole-blood gene expression data from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), accession number GSE1915127. The microarray data set, consisting of 70 adults with ≥1 prior VTE on warfarin and 63 healthy controls, was analyzed using an independent sample Student t test and the Benjamin-Hochberg false discovery rate correction for multiple testing (P < .05).28

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics for the discovery and replication cohorts are provided in Table 1. Only mean age was statistically significant between VTE cases and controls in both the discovery and replication cohorts (54.9 ± 16.9 and 58.6 ± 16.0, P < .001; and 59.3 ± 10.9 and 63.0 ± 16.4, P = .04; respectively [Table 1]), therefore, all analyses were adjusted for age. Utilizing healthy controls recruited from the DCPC resulted in an overrepresentation of males among controls in the discover cohort, therefore the association between sex and risk of VTE excluded DCPC controls (Table 1). After excluding DCPC controls, sex was not found to be significantly associated with risk of VTE in the remaining discovery cohort, and this lack of association was also observed in the replication cohort. Participants in the discovery cohort clustered between the HapMap CEU (northern and western European ancestry) and YRI (African ancestry) samples, as expected (supplemental Figure 1). Only 1 sample deviated from the expected clustering and was excluded from the analysis (supplemental Figure 1). The first 10 principle components were not associated with disease status.

Table 1.

Association between demographic and clinical characteristics to VTE risk in each cohort

| Characteristic | Discovery cohort | Replication cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 146) | Controls (n = 432) | P | Cases (n = 94) | Controls (n = 65) | P | |

| Age, y* | 54.9 ± 16.9 | 59.3 ± 10.9 | .004 | 58.6 ± 16.7 | 64.9 ± 16.0 | .02 |

| Height, cm* | 167.3 ± 10.8 | 168.1 ± 9.8 | .61 | 171.8 ± 12.3 | 170.2 ± 10.2 | .41 |

| Weight, kg* | 93.3 ± 28.9 | 87.4 ± 23.4 | .22 | 99.9 ± 33.4 | 100.0 ± 34.1 | .99 |

| West African Ancestry, % | 81 | 80 | .54 | 77 | 76 | .33 |

| Sex, % | ||||||

| Female | 73.3 | 70.4 | .77 | 45.7 | 45.2 | .82 |

| Male | 26.7 | 29.5† | 54.3 | 54.8 | ||

| VTE location in cases, % | ||||||

| DVT | 51 | 47 | ||||

| PE | 2 | 36 | ||||

| DVT/PE | 24 | 17 | ||||

Values are mean ± standard deviation.

Association between sex and risk of VTE excluded DCPC controls.

Association of genetic variants with VTE

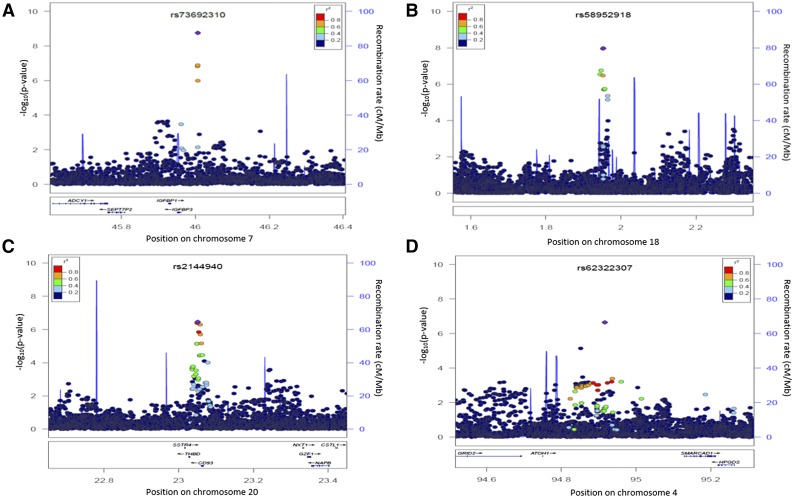

In the discovery cohort, we identified 7 SNPs that increased the risk of VTE by 2.18- to 3.04-fold. Among these, SNP rs73692310 on chromosome 7 (odds ratio [OR], 3.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.0-4.7; P = 1.73 × 10−9) and SNPs rs58952918 (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 1.7-3.7; P = 1.07 × 10−8) and rs28496996 (OR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.6-3.6; P = 1.07 × 10−8) on chromosome 18 reached genome-wide significance. On chromosome 20, SNPs rs2144940 (OR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.6-2.9; P = 3.52 × 10−7), rs2567617 (OR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.6-2.9; P = 4.01 × 10−7), and rs1998081 (OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.6-3.1; P = 5.17 × 10−7), as well as SNP rs62322307 on chromosome 4 (OR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.8-4.3; P = 2.25 × 10−7) were strongly suggestive of association to VTE risk (Table 2). These risk alleles were found either almost exclusively or in higher frequency among populations of African descent (Table 3). All SNPs are intergenic; however, rs73692310 is ∼50 kb from IGFBP3; rs2144940, rs2567617, and rs1998081 are located between THBD and CD93; and the closest gene to rs62322307 is ATOH1 (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Top allelic associations to VTE risk among AAs

| Chr | SNP | Nearby genes | MA | Discovery cohort | Replication cohort | Meta-analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM | MAF cases | MAF controls | OR (95% CI) | P* | MAF cases | MAF controls | OR (95% CI) | P* | P | ||||

| 4 | rs62322307 | ATOH1 | T | 0.94 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 2.79 (1.8-4.3) | 2.25 × 10−7 | ND | ND | ND | ND | NA |

| 7 | rs73692310 | IGFBP3 | T | 0.78 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 3.04 (2.0-4.7) | 1.73 × 10−9 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 1.27 (0.4-2.7) | .60 | 2.48 × 10−8 |

| 18 | rs58952918 | NA | A | 0.90 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 2.48 (1.7-3.7) | 1.07 × 10−8 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NA |

| 18 | rs28496996 | NA | G | 0.90 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 2.44 (1.6-3.6) | 1.13 × 10−8 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 1.34 (0.6-2.6) | .45 | 6.37 × 10−8 |

| 20 | rs2144940 | THBD, CD93 | C | 0.97 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 2.18 (1.6-2.9) | 3.52 × 10−7 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 1.89 (1.1-3.3) | .016 | 1.88 × 10−8 |

| 20 | rs2567617 | THBD, CD93 | G | 0.98 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 2.17 (1.6-2.9) | 4.01 × 10−7 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NA |

| 20 | rs1998081 | THBD, CD93 | T | NA | 0.27 | 0.14 | 2.28 (1.6-3.1) | 5.17 × 10−7 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 1.94 (1.1-3.5) | .016 | 4.62 × 10−8 |

SNP rs1998081 was genotyped.

Chr, chromosome; IM, infometric (takes a value between 0 and 1, whereby values near 1 indicate that an SNP has been imputed with high certainty); MA, minor allele; MAF, minor allele frequency; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined due to failed assay; NT, not tested due to high LD.

Age adjusted.

Table 3.

Minor allele frequency distribution among populations from the 1000 Genomes

| Chromosome | SNP | Discovery cohort | ASW | AFR | ASN | EUR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | rs62322307 (T) | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.0 | 0.03 |

| 7 | rs73692310 (T) | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.0 | 0.001 |

| 18 | rs58952918 (A) | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.0 | 0.003 |

| 18 | rs28496996 (G) | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.0 | 0.003 |

| 20 | rs2144940 (C) | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| 20 | rs2567617 (G) | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| 20 | rs1998081 (T) | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

AFR, African; ASN, Asian; ASW, Americans of African Ancestry in SW USA; EUR, European.

Figure 1.

Locus-specific plots of genotyped and imputed SNP results for top loci. Position on chromosome 7 (A), chromosome 18 (B), chromosome 20 (C), and chromosome 4 (D). Purple diamond indicates the most significant finding in the region. Colors on the marks represent LD (r2) with the top SNP. Chromosomal positions and linkage LD are based on hg19/1000 Genomes Mar 2012 AFR (http://csg.sph.umich.edu/locuszoom/).

To validate the association between SNPs and VTE risk in the discovery cohort, we sought to replicate these findings in an independent AA cohort. LD between SNPs was obtained from the “1000 Genomes among Americans of African Ancestry in SW USA.” For SNPs in LD (coefficient of determination r2 ≥ 0.8), we chose to genotype the SNP with the lowest P value for each pair. To validate LD with SNP rs2144940, an exception was made for rs1998081. SNP rs62322307 did not pass genotyping quality control measures and was therefore not tested. The replication study confirmed a significant association with increased risk of VTE for rs2144940 and rs1998081 (Table 2). Carriers of the minor allele (C) for rs2144940 and the minor allele (T) for rs1998081 had an increased risk of VTE (OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.1-3.3; P = .02 and OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.1-3.5; P = .02, respectively) compared with noncarriers (Table 2). In the meta-analysis of the results, rs2144940 and rs1998081 reached genome-wide significance (1.88 × 10−8 and 4.62 × 10−8, respectively; Table 2). In our replication cohort, we were able to confirm LD between rs2144940 and rs1998081 (r2 = 0.82). Together, these data support the association of SNPs rs2144940, rs2567617, and rs1998081 with increased risk of VTE among AAs.

We also compared previously identified VTE risk alleles in populations of EA with our discovery cohort (Table 4). SNPs rs6025 (factor V) and rs1799963 (coagulation factor II [F2]) were monomorphic; however, we replicated 3 previously identified ABO SNPs associated with risk of VTE in our discovery cohort, although not at genome-wide significance (P > .002; Table 4). More recently, a very large meta-analysis among populations of EA identified rs78707713 (TSPAN15) and rs2288904 (SLC44A2) as susceptibility loci for VTE (Table 4).29 However, rs78707713 is found in very low frequency outside of EA populations, and rs2288904 was not associated with VTE risk in our discovery cohort (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of previously identified VTE risk alleles between the discovery cohort and populations of EA

| Discovery cohort | Previous studies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr | SNP | Allele | AF | OR (95% CI) | P* | AF | OR | P | Reference |

| 1 | rs6025 (F5) | T | 0.0 | NA | NA | 0.06 | 2.56 | 1.40 × 10−12 | 11 |

| 11 | rs1799963 (F2) | A | 0.0 | NA | NA | 0.02 | 1.69 | 3.00 × 10−2 | 11 |

| 9 | rs687621 (ABO) | G | 0.43 | 1.55 (1.2-2.0) | 0.002 | 0.43 | 1.84 | 6.69 × 10−22 | 10 |

| 9 | rs505922 (ABO) | C | 0.36 | 1.52 (1.2-2.0) | 0.002 | 0.43 | 1.85 | 1.84 × 10−22 | 10 |

| 9 | rs657152 (ABO) | A | 0.44 | 1.39 (1.1-1.8) | 0.03 | 0.45 | 1.7 | 2.00 × 10−17 | 10 |

| 10 | rs78707713 (TSPAN15) | T | 0.97† | NA | NA | 0.88 | 1.28 | 5.74 × 10−11 | 29 |

| 19 | rs2288904 (SLC44A2) | G | 0.93 | 0.90 (0.5-1.5) | 0.75 | 0.79 | 1.19 | 1.07 × 10−9 | 29 |

AF, allele frequency; Chr, chromosome; NA, not available.

Age adjusted.

Allele frequency taken from 1000 Genomes–Americans of African Ancestry in SW USA (ASW).

Effect of VTE-associated variants on gene expression

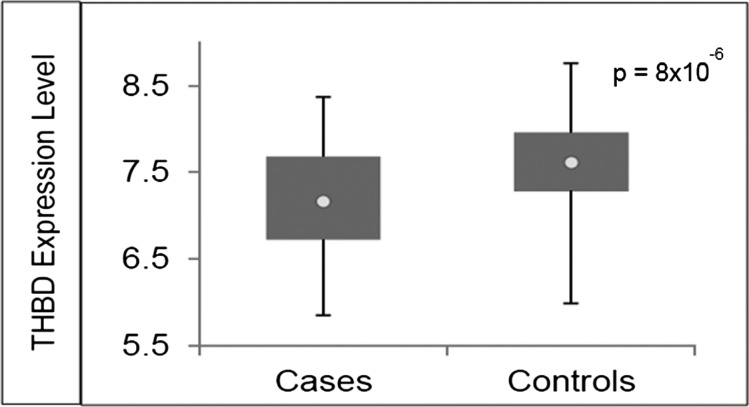

To identify a plausible biological function for our top SNP associations with VTE risk, we used the GTEx Portal, which provides information on correlations between tissue-specific gene expression levels and genetic variation.26 We found that rs1998081, rs2567617, and rs2144940 genotypes are associated with differential THBD gene expression in whole blood (P = 1.3 × 10−7, P = 4.8 × 10−6, and P = 4.6 × 10−6, respectively; Figure 2). This information suggests that SNPs rs1998081, rs2567617, and rs2144940 are cis-eQTLs (map within 500 kb of the transcription start site) for THBD, a candidate gene in the coagulation pathway. Furthermore, the lower THBD gene expression levels observed in the presence of the minor alleles are in accordance with its association with increased risk of VTE. To examine whether THBD gene expression levels vary between VTE cases and controls, we conducted a whole-genome differential expression analysis of data obtained from the GEO. We found mean THBD gene expression levels to be significantly lower in VTE cases (7.15 ± 0.59) compared with controls (7.61 ± 0.54; unadjusted P = 8.10 × 10−6; adjusted for multiple testing P = 4.31 × 10−5; Figure 3), and the variance (r2) explained by THBD expression levels to be 14%.

Figure 2.

THBD gene expression levels. THBD gene expression levels by rs1998081 (A), rs2567617 (B), and rs2144940 (c) genotypes in whole blood. Data were obtained from the GTEx Analysis V6 for 338 individuals. The box and whisker plot shows the correlation of genotype with THBD gene expression. The minor allele for each SNP represents the risk allele in our study, and increasing copies of the risk allele are associated with decreased THBD gene expression in whole blood. The x-axis of each plot corresponds to the 3 observed genotypes for each SNP. The y-axis represents the normalized gene expression. The SNPs are located on chromosome 20 and are in high LD with each other (r2 > 0.80). The P value refers to the allelic association to THBD gene expression levels.

Figure 3.

Differential THBD gene expression between VTE cases and controls. The expression data for GSE19151 was obtained from the GEO database. Differential THBD gene expression is observed between VTE cases and controls. Circle indicates the mean.

Discussion

Our study is the first to investigate genetic variation associated with risk of VTE at a genome-wide level, which allowed us to identify regulatory variants and THBD gene expression predictors of VTE affecting AAs specifically. In the United States, VTE remains associated with significant morbidity and mortality and disproportionately affects AAs. Our GWAS identified 3 novel SNPs located on chromosome 20 (rs2144940 [OR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.6-2.9; P = 3.52 × 10−7], rs2567617 [OR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.6-2.9; P = 4.01 × 10−7], and rs1998081 [OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.6-3.1; P = 5.17 × 10−7]) associated with increased risk of VTE among AAs, which were validated in an independent cohort (Table 2). These risk alleles are found in much higher frequency among populations of African descent (∼20%-30%) compared with European and Asian populations (8% and 5%, respectively) (Table 3). Through bioinformatics analyses of whole-blood transcriptome data, we determined that rs2144940, rs2567617, and rs1998081 are significant cis-eQTLs for THBD, and the minor alleles are associated with decreased THBD gene expression (Figure 2). In addition, when comparing VTE cases to controls, THBD gene expression was found to be significantly lower in cases vs controls (P = 8.0 × 10−6; Figure 3).

THBD plays a pivotal role in the regulation of coagulation.30 THBD is an endothelial glycoprotein that binds to thrombin and thus dramatically suppresses the amount of thrombin available for clot formation.31 THBD acts as an intrinsic anticoagulant by forming a 1:1 complex with the coagulation factor thrombin (F2) and altering F2 specificity for several substrates, ultimately acting as an antithrombotic factor.32 In addition, the F2:THBD complex activates protein C, leading to degradation of factors V and VIII.30 Consequently, THBD is an important candidate gene in VTE risk. However the specific THBD SNPs associated with VTE risk have not been definitively identified.32,33 The functional implication that the minor alleles of rs2144940 (C), rs2567614 (G), and rs1998081 (T) are associated with lower THBD gene expression, combined with lower THBD gene expression in VTE cases compared with controls, supports our findings that carriers of the minor alleles for rs2144940, rs2567617, and rs1998081 have an increased risk of VTE (Figure 2; Table 2).

Recently, a study among African-Caribbean DVT patients found thrombin levels to be significantly higher compared with DVT patients of EA and healthy African-Caribbean control subjects.34 It is possible that a combination of higher levels of thrombin and genetic polymorphisms that reduce THBD gene expression may significantly increase an individual’s risk for VTE. Furthermore, a previous study has suggested that chromosome 20 may harbor common variants yet to be identified that could contribute ∼7% of the total genetic variance underlying VTE susceptibility.10 Our results help place these previous findings in the context of a specific gene and regulatory SNPs that affect the expression of this gene.

GTEx data, which consist of samples from mostly (85%) EA identified rs2424508 as highly associated with THBD expression (P = 1.0 × 10−6; data not shown). In individuals of EA, rs2424508 is in strong LD with rs2144940, rs2567617, and rs1998081 (r2 > 0.8), but not in populations of African ancestry. This may explain the association to THBD gene expression observed in GTEx data and the lower association to VTE risk found in our discovery cohort for rs2424508 (OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.4-2.7; P = .0002). Nonetheless, it demonstrates the potential of rs2144940, rs2567617, and rs1998081 to affect THBD gene expression in other populations, albeit with a smaller effect, given the low minor allele frequency in populations outside of Africa. According to GEO (GSE19151) expression data, we found THBD gene expression to be lower among VTE cases compared with controls. The data were collected from cases during warfarin treatment; therefore, the effect of warfarin on THBD gene expression cannot be assessed independently of case status. SNPs rs2144940, rs2567617, and rs1998081 are located in close proximity to CD93, which has been implicated in acute myocardial infarction.35 Based on the GSE19151 data set, CD93 and THBD gene expression levels are highly correlated (β = 0.42, P < .001).

The 2 well-established VTE risk alleles, rs6025 (factor V Leiden) and rs1799963 (prothrombin G20210A), which are used clinically, are rare in AAs and are therefore of limited clinical utility in this population.36-38 As expected, we did not observe these risk alleles in our discovery cohort; yet, among EA populations, these risk alleles continue to be highly associated with VTE susceptibility (Table 4). Since the early 1960s, the ABO blood group has been recognized as a risk factor for VTE, with the non-O blood types having a higher risk of VTE compared with O blood type.19 In the United States, AAs exhibit a higher incidence of VTE and mortality rates from the disease compared with populations of European and Asian ancestry.3,4,39,40 Nonetheless, AAs have a higher percentage of O blood type, which is in the opposite direction of what would be expected.6,41 Several GWASs have identified polymorphisms in the ABO gene to be associated with risk of VTE among populations of EA10-12 Although not at GWAS significance, 3 previously identified ABO SNPs were also associated with risk of VTE in our discovery cohort (Table 4). Among these ABO SNPs is rs687621 (OR, 1.56; P = .002), which in populations of EA is in LD with rs8176719, the ABO blood type non-O allele associated with increased risk of VTE (Table 3).11,42 Our study confirmed the association of these SNPs with VTE at nominally significant P values (Table 4). However, given the lower ORs of these associations, ABO is unlikely to contribute significantly to VTE risk in AAs. A lack of association among populations of EA and other groups for SNPs that are highly significant in AAs has been previously observed13 and may be due to the difference in LD structure between ethnic groups.

A limitation of our study was the relatively small sample size for both the discovery cohort and the replication cohort, which may have affected our ability to replicate the SNPs on chromosomes 7 and 18, which reached genome-wide significance (Table 2). Unfortunately, there is a lack of genome-wide data in well-phenotyped AA cohorts in general. Again, this limitation is further highlighted in the publicly available data sets obtained from GTEx and GEO, which consist of predominantly EA participants. Another factor to be considered is that our discovery cohort consisted of 2 data sets, IWPC and DCPC. However, extensive quality control measures were taken, including a pseudo-GWAS between controls, to eliminate false associations arising from differences in our controls. Utilizing the DCPC data set introduced a biased overrepresentation of males. When excluding the DCPC cohort, we found that sex was not significantly associated with risk of VTE in the discovery cohort (Table 1). The lack of association between sex and VTE risk was also found in the replication cohort, suggesting that sex is not a strong predictor of VTE in our AA cohorts (Table 1).

In summary, our study has identified common genetic risk factors (rs2144940, rs2567617, and rs1998081) for VTE among AAs with minor allele frequencies of ∼20%, meaning that 36% of AAs carry at least 1 risk allele, providing evidence that common variants in the region significantly contribute to VTE risk in AAs. We demonstrate that THBD is differentially expressed between VTE cases and controls and that our novel SNPs are also associated with decreased THBD gene expression. Taken together, our findings support a novel role for SNPs rs2144940, rs2567617, and rs1998081 as VTE risk alleles among AAs. In addition, we further validate that rs6025 (factor V Leiden) and rs1799963 (prothrombin G20210A) are extremely rare in AAs and are therefore of limited clinical utility in risk assessment in this population as the current standard of care, and demonstrate the limited role of ABO variants in VTE risk in AAs. Thus, our findings may help better understand the etiology of VTE among AAs and highlight the importance of conducting population-specific research in precision medicine. These results demonstrate the unique discoveries that are possible through ethnic-specific genomic studies due to differences in LD structure and allele frequencies between populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dan Nicolae, Department of Medicine, Section of Genetic Medicine, for his valuable input in the analysis process; and the RIKEN research institute for their ongoing collaboration that provided our high-quality genome-wide genotyping.

This study was supported (in part) by research funding from the National Collaborative on Aging Faculty Awards Program (T.J.O., A.F.H., and M.T.); the American Heart Association Midwest Affiliate Grant-In-Aid (10GRNT3750024) (L.H.C.); the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants K23 HL089808-01A2 and R21 HL106097-01A1 and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant 1R01MD009217-01 (M.A.P.); the University of Chicago Cardiovascular Sciences Training grant 5T32 HL007381 (W.H.); CA157823, and National Institutes of Health National Institute of Mental Health grants R01 MH101820 and R01 MH090937 (E.R.G.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: W.H. analyzed and interpreted the data and cowrote the paper; E.R.G. provided analytical support and analyzed the GEO gene expression data; E.S., A.B., and R.A.K. were responsible for sample processing, DNA extraction, and/or genotyping; R.A.K., T.J.O., A.F.H., M.T., and L.H.C. provided patient samples and clinical information; and M.A.P. contributed to the design of the study, data analysis, data interpretation, and cowrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Minoli A. Perera, Section of Genetic Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, 900 E. 57th St, Room 3220B, Chicago IL 60637; e-mail: mperera@bsd.uchicago.edu.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.White RH, Keenan CR. Effects of race and ethnicity on the incidence of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2009;123(Suppl 4):S11–S17. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(09)70136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zakai NA, McClure LA. Racial differences in venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(10):1877–1882. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ageno W, Becattini C, Brighton T, Selby R, Kamphuisen PW. Cardiovascular risk factors and venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2008;117(1):93–102. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.709204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckman MG, Hooper WC, Critchley SE, Ortel TL. Venous thromboembolism: a public health concern. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 Suppl):S495–S501. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang C, Cohen HW, Billett HH. Race, ABO blood group, and venous thromboembolism risk: not black and white. Transfusion. 2013;53(1):187–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Souto JC, Almasy L, Borrell M, et al. Genetic susceptibility to thrombosis and its relationship to physiological risk factors: the GAIT study. Genetic Analysis of Idiopathic Thrombophilia. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(6):1452–1459. doi: 10.1086/316903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heit JA, Phelps MA, Ward SA, Slusser JP, Petterson TM, De Andrade M. Familial segregation of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2(5):731–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7933.2004.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen TB, Sørensen HT, Skytthe A, Johnsen SP, Vaupel JW, Christensen K. Major genetic susceptibility for venous thromboembolism in men: a study of Danish twins. Epidemiology. 2003;14(3):328–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Germain M, Saut N, Greliche N, et al. Genetics of venous thrombosis: insights from a new genome wide association study. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heit JA, Armasu SM, Asmann YW, et al. A genome-wide association study of venous thromboembolism identifies risk variants in chromosomes 1q24.2 and 9q. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(8):1521–1531. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04810.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trégouët DA, Heath S, Saut N, et al. Common susceptibility alleles are unlikely to contribute as strongly as the FV and ABO loci to VTE risk: results from a GWAS approach. Blood. 2009;113(21):5298–5303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perera MA, Cavallari LH, Limdi NA, et al. Genetic variants associated with warfarin dose in African-American individuals: a genome-wide association study. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):790–796. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60681-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haiman CA, Chen GK, Blot WJ, et al. Genome-wide association study of prostate cancer in men of African ancestry identifies a susceptibility locus at 17q21. Nat Genet. 2011;43(6):570–573. doi: 10.1038/ng.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernandez W, Gamazon ER, Aquino-Michaels K, et al. Ethnicity-specific pharmacogenetics: the case of warfarin in African Americans. Pharmacogenomics J. 2014;14(3):223–228. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2013.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg NA, Li LM, Ward R, Pritchard JK. Informativeness of genetic markers for inference of ancestry. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73(6):1402–1422. doi: 10.1086/380416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155(2):945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delaneau O, Marchini J, Zagury JF. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat Methods. 2012;9(2):179–181. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44(8):955–959. doi: 10.1038/ng.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howie B, Marchini J, Stephens M. Genotype imputation with thousands of genomes. G3 (Bethesda) 2011;1(6):457–470. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.001198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchini J, Howie B. Genotype imputation for genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(7):499–511. doi: 10.1038/nrg2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(18):2336–2337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lonsdale J, Thomas J, Salvatore M, et al. GTEx Consortium. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45(6):580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Center for Biotechnology Information. GEO: Gene expression omnibus. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo. Accession number GSE19151.

- 28.Lewis DA, Stashenko GJ, Akay OM, et al. Whole blood gene expression analyses in patients with single versus recurrent venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2011;128(6):536–540. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Germain M, Chasman DI, de Haan H, et al. Cardiogenics Consortium. Meta-analysis of 65,734 individuals identifies TSPAN15 and SLC44A2 as two susceptibility loci for venous thromboembolism. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(4):532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esmon NL. Thrombomodulin. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1987;13(4):454–463. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1003522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackman RW, Beeler DL, Fritze L, Soff G, Rosenberg RD. Human thrombomodulin gene is intron depleted: nucleic acid sequences of the cDNA and gene predict protein structure and suggest sites of regulatory control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(18):6425–6429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.18.6425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anastasiou G, Gialeraki A, Merkouri E, Politou M, Travlou A. Thrombomodulin as a regulator of the anticoagulant pathway: implication in the development of thrombosis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2012;23(1):1–10. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32834cb271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heit JA, Petterson TM, Owen WG, Burke JP, De Andrade M, Melton LJ., III Thrombomodulin gene polymorphisms or haplotypes as potential risk factors for venous thromboembolism: a population-based case-control study. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):710–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts LN, Patel RK, Chitongo P, Bonner L, Arya R. African-Caribbean ethnicity is associated with a hypercoagulable state as measured by thrombin generation. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24(1):40–49. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32835a07fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Youn JC, Yu HT, Jeon JW, et al. Soluble CD93 levels in patients with acute myocardial infarction and its implication on clinical outcome. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dilley A, Austin H, Hooper WC, et al. Prevalence of the prothrombin 20210 G-to-A variant in blacks: infants, patients with venous thrombosis, patients with myocardial infarction, and control subjects. J Lab Clin Med. 1998;132(6):452–455. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(98)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dowling NF, Austin H, Dilley A, Whitsett C, Evatt BL, Hooper WC. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in Caucasians and African-Americans: the GATE Study. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(1):80–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel RK, Ford E, Thumpston J, Arya R. Risk factors for venous thrombosis in the black population. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90(5):835–838. doi: 10.1160/TH03-05-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hooper WC. Venous thromboembolism in African-Americans: a literature-based commentary. Thromb Res. 2010;125(1):12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang Y, Sampson B, Pack S, et al. Ethnic differences in out-of-hospital fatal pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2011;123(20):2219–2225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.976134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garratty G, Glynn SA, McEntire R Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study. ABO and Rh(D) phenotype frequencies of different racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Transfusion. 2004;44(5):703–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.03338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang W, Teichert M, Chasman DI, et al. A genome-wide association study for venous thromboembolism: the extended cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37(5):512–521. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]