Abstract

Background:

Diabetes mellitus is a major global health problem covering approximately 347 million persons worldwide. Glycemic control has a main role in its management which mainly depends upon patient adherence to the treatment plan. Accurate assessment of medication adherence is necessary for effective management of diabetes.

Objective:

To assess nonadherence and factors affecting adherence of diabetic patients to anti-diabetic medication in Assela General Hospital (AGH), Oromia Region, Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods:

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted on patients seeking anti-diabetic drug treatment and follow-up at AGH using structured questionnaire and reviewing the patient record card using check list from January 24, 2014 to February 7, 2014. Descriptive analysis was used to describe the percentages and number of distributions of the variables in the study; and association was identified for categorical data. P ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Result:

Of all respondents, 149 (52.3%) and 136 (47.7%) were female and male, respectively. The majority of the study participants 189 (66.3%) were in the age group of 30–60 years. Two-hundred nineteen (76.8%) of respondents were married currently. The majority, 237 (83.2%) of respondents did not have blood glucose self-monitoring equipment (glucometer). A total of 196 (68.8%) respondents were adhered to anti-diabetic medication. There was a significant association between adherence to the medication and side effect, level of education, monthly income and presence of glucometer at home (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

The participants in the area of study were moderately adherent to their anti-diabetic medications with nonadherence rate of 31.2%. Different factors of medication nonadherence were identified such as side effect and complexity of regimen, failure to remember, and sociodemographic factors such as educational level and monthly income.

KEY WORDS: Anti-diabetic medication, Assela Hospital, diabetes mellitus, medication nonadherence

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder resulting from a defect in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both, and its prevalence is rapidly rising all over the globe at an alarming rate.[1,2] DM is a major global health problem affecting approximately 347 million persons worldwide.[3] Nearly, half of the individuals with DM remain undiagnosed thereby being subjected to DM related risk of complication.[4,5] In 2014, 9% of adults 18 years and older had diabetes. In 2012, diabetes was the direct cause of 1.5 million deaths. More than 80% of diabetes deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.[6] The estimated prevalence of DM in the adult population of Ethiopia is 1.9%.[7]

Glycemic control has a main role in diabetes management which mainly depends upon patient adherence to the treatment plan.[8,9] To maintain adequate glycemic control, patients typically follow a self-management regimen involving frequent self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG), dietary modifications, exercise, education, and medication administration. Collaboration and negotiation with health care providers, family members, and others are essential so that such behavior changes are optimally supported and encouraged.[10] Adherence is the default medical term used in literature to depict patient's behavior (in terms of taking medication, following diets, or executing lifestyle changes.[9] Adherence to a medication regimen has been defined as the extent that each patient takes medications as prescribed by their health care providers.[11] Hence, it implies active, voluntary, and collaborative involvement of the patient in a mutually acceptable course of behavior to produce a therapeutic result.[12]

Accurate assessment of medication adherence is necessary for effective management of diabetes. However, there is no gold standard for such assessment although various methods have been reported in the literature.[13] A systematic review of literature showed that adherence to oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs) which measured by retrospective analysis ranged from 36% to 93%, although prospective electronic monitoring analysis of outcomes documented 67–85% of patients took OHAs as prescribed.[14] There are different methods to measure adherence to OHAs such as pill count, medication event monitoring system, refill data, and self-report.[15]

Assisting patients to adhere to often complex treatment regimens and achieve tight blood glucose control is a challenge that must be addressed during all phases of diabetic treatment.[16] Nonadherence, poverty, lack of knowledge and poor follow-ups are the main factors observed in poor glycemic control[17] and may lead to suboptimal therapeutic goals and also associated with increased risk of hospitalization.[18,19,20] Nonadherence in chronic diseases has been described as taking <80% of the prescribed treatment.[12] Some reported factors as predictors of medication adherence to anti-diabetic treatment are patient characteristics, the complexity of the therapeutic regimen and characteristics of health care systems.[21]

Besides the absence of sufficient national data on prevalence and incidence of DM in Ethiopia, there is increasing attendance rates and medical admissions in hospitals.[22] According to IDFA report, (2012) Ethiopia ranked 3rd among the top ten countries in Africa with 1.4 million DM cases and estimated the prevalence of 3.32%.[23]

Nonadherence to chronic diseases has been described as taking <80% of the prescribed treatment. Adherence to diabetes treatment has been reported to be suboptimal ranging from 23% to 77%.[12] There is a gap in knowledge about the prevalence and factors affecting adherence to diabetic treatment in developing countries because a limited number of studies were conducted in these countries. This study was carried out to address the area not covered previously and at least to narrow down the knowledge gap from the South Eastern part of the country. Therefore, the aim of our study was to assess nonadherence and factors affecting adherence of Diabetic Patients to anti-diabetic Medication in Assela General Hospital (AGH), Oromia Region, Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in AGH, which is found in Assela town, Arsi zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Assela town is located 175 km in the South-East of Addis Ababa. The hospital has several departments to deliver diversified health care activities through a number of different care providing units. Among the units, diabetes follow-up clinic is the one which provides anti-diabetic treatment and counseling.

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted by interviewing the patients visiting the diabetic clinic for follow-up using structured questionnaire and by reviewing case charts using checklist to assess the level of adherence to anti-diabetic treatment among DM patients, who were following their treatment in AGH between January 24, 2014 and February 7, 2014. A self-reported 4-item Morisky medication adherence scale was used. Patients who have been on anti-diabetic drugs for more than 2 months, age above 18 years, who have no communication problem, who have no mental problems and volunteer to participate in the study were included in the study and those below the age of 18 years, elders above 80 years (because of fear of recall bias), those with obvious psychiatric problems were not included in the study. Sample size was determined by using the following formula based on the following assumption: “P” is the proportion of patients adherent to the treatment; which was assumed to be 50%; “n” is the required sample size, “z” is a standard score corresponding to 95% confidence level and “d” is the margin of error (5%). From this the determined sample size was:

n = (z [a/2]2 × p [1 − P])/d2 = ([1.96]2 × [0.5] [1 − 0.5])/(0.05)2 = 384. Since the number of total population was < 10,000 (N < 10,000) the size of sample was adjusted by the following formula:

nf = n/[1 + (n/N)] =384/[1+(384/923)] =271.

After considering 5% nonresponse rate, a final sample size was 285.

Where n = The calculated sample size = 384, N = Total DM patients (923), nf = adjusted sample size.

Data were collected by using pretested data collection format. Every day the collected data were reviewed and checked for completeness and consistency of response.

Data were analyzed by using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16 for Windows. Descriptive analysis was used to describe the percentages and number of distributions of the variables in the study; and the association was identified for categorical data. P ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The result was presented using tables, graphs and texts as based on the type of data.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Pharmacy Department, College of Public Health and Medical Sciences, Jimma University. Then, officials at different levels in the study area were communicated through letters from Jimma University, College of Public Health and Medical Science Department of Pharmacy. Informed consent was obtained verbally from each study participant after a clear explanation about the purpose of the study. Confidentiality of the information was assured, and privacy of the respondents was maintained.

Operational definitions

Health literacy

The degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.

Adherence

The active, voluntary, and collaborative involvement of the patient in a mutually acceptable course of behavior to produce a therapeutic result.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

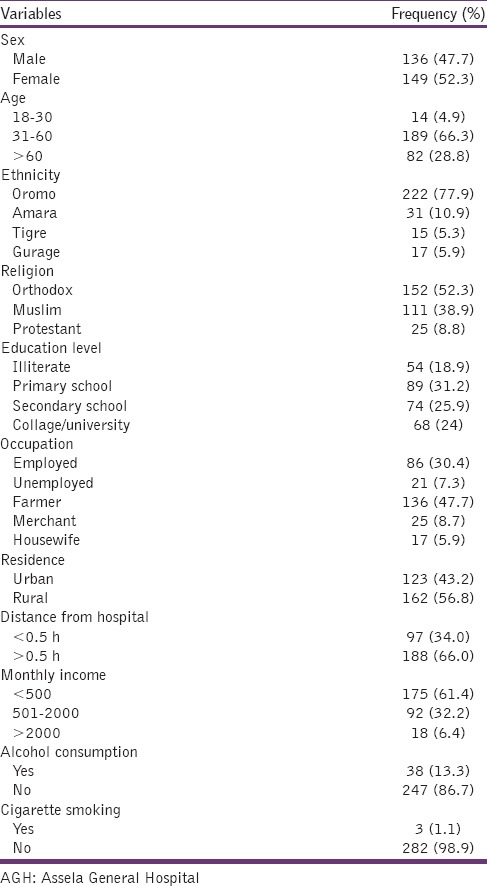

Of total respondents, 285 were involved in the study (females [149, 52.3%] and males [136, 47.7%]). The majority of them (189, 66.3%) were in the age group of 30–60 years. Two hundred nineteen (76.8%) of respondents were married currently. Most of them, 152 (52.3%) were orthodox Christian and Oromo (77.9%) by ethnicity. About 54 (18.9%) of the respondents were illiterate. 61.4% reported that they earn <500 birr per month. Only 3 (1.1%) of them reported habit of smoking and 38 (13.3%) of them were alcohol consumers [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of diabetic patients at diabetic clinic of AGH, January 24, 2014 to February 7, 2014 (n=285)

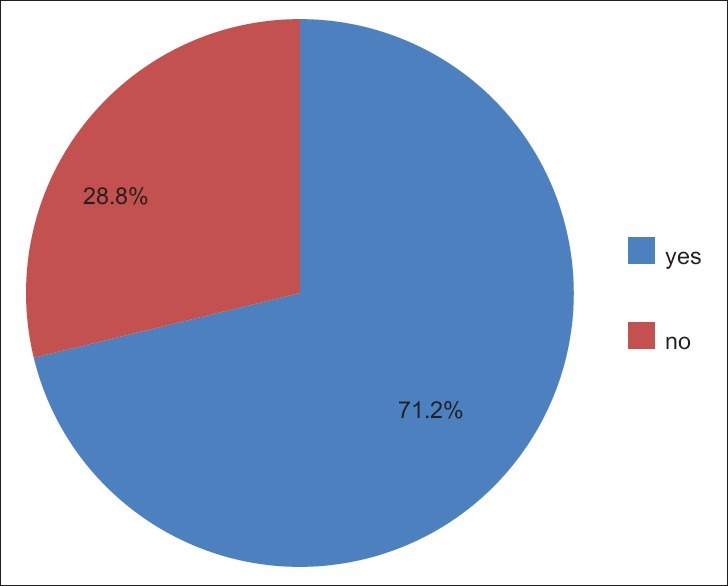

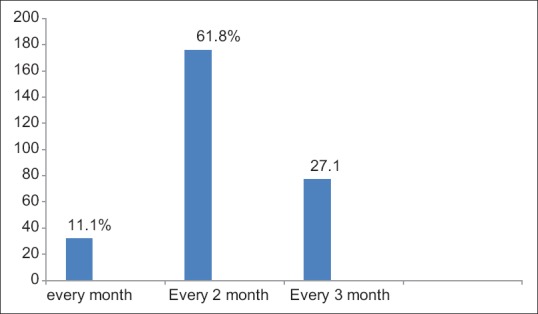

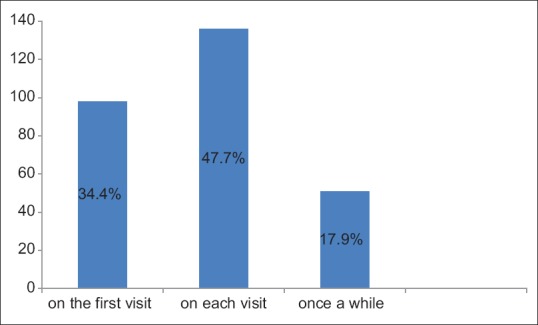

Factors related to service provider and health facility

The majority of the participants 203 (71.2%) were satisfied by service provided [Figure 1]. Most of the study participants reported that they visit the health service every 2 months (61.8%) [Figure 2]. Around 136 (47.7%) of participants reported that they get counseling service by health care providers on each visit [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Patients' satisfaction in relation to service provider and health facility at diabetic clinic of Assela General Hospital January 24, 2014 to February 7, 2014 (n = 285)

Figure 2.

Frequency of visiting diabetic clinic by the study participants, Assela General Hospital, January 24, 2014 to February 7, 2014 (n = 285)

Figure 3.

Frequency of getting counseled by healthcare providers in diabetic clinic at Assela General Hospital, January 24, 2014 to February 7, 2014 (n = 285)

Distribution of different variables among the patients

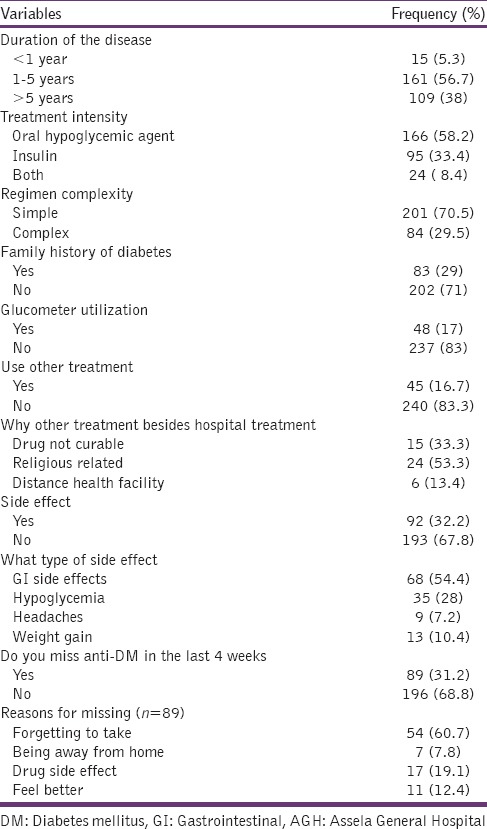

The majority, 161 (56.7%), of participants, were on diabetic treatment for 1–5 years. Of all respondents, 166 (58.2%), 95 (33.4%), and 24 (8.4) had OHA, insulin, and both treatment intensity respectively. A Larger proportion of patients, 201 (70.5%) were on the simple regimen. At least one side effect to diabetic medication had been reported by, 92 (32.2%) participants. Two-hundred two (71%) of the respondents did not have a family history of diabetes and only 48 (17%) respondents had a glucometer at home. Some of the respondents, 45 (16.7%), reported to use additional treatment options besides hospital treatment. Eighty-nine (31.2%) of the study participants missed one or more doses in the last month during the study period. A major reason for missed doses was forgetting to take the medication (60.7%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution of different variables among DM patients in diabetic clinic of AGH, January 24, 2014 to February 7, 2014 (n=285)

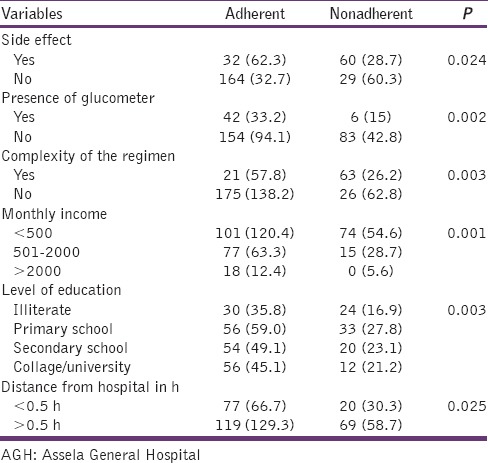

Factors associated with anti-diabetic treatment adherence

The prevalence of nonadherence was 31.2% (n = 285). Side effect (P = 0.024), presence of glucometer (P = 0.002), complexity of regimen (P = 0.003), monthly income (P = 0.001), level of education (0.003), and distance from hospital (0.02) were significantly associated with nonadherence [Table 3].

Table 3.

Factors associated with nonadherence in diabetic clinic of AGH, January 24, 2014 to February 7, 2014 (n=285)

Discussion

Diabetes and associated complications pose a major healthcare burden worldwide and present major challenge to patients, healthcare systems and national economies.[24] Poor medication adherence seems to be a significant barrier to the attainment of positive clinical outcome among diabetes patients.[25] Presently, there is no single measure accepted as the gold standard to measure medication adherence since all commonly employed methods have drawbacks. In this study, from the available methods, a self-reported 4-item Morisky medication adherence scale was used to assess medication nonadherence. The Morisky's instrument was adopted as a method of measuring adherence because of its simplicity, economic feasibility, and as one of the most useful methods in clinical settings.[26] This was done by requiring patients to answer the questions on the basis of their adherence behavior of last 1-month during the study period.

Adherence to medications is of paramount importance because there are strong correlations between medication adherence, patient outcomes, and treatment costs.[27] In patients with chronic diseases like DM, medication nonadherence puts a considerable problem in the management. Worldwide adherence rate for medication for diabetes vary between 36% and 93%. Adherence to prescribed medication is crucial to reach metabolic control as nonadherence with blood glucose lowering, or lipid-lowering drug is associated with higher glycosylated hemoglobin and cholesterol, levels, respectively.[28] The prevalence of nonadherence in this study was lower as compared to the study results reported from Nigeria as well as from Egypt[4,29] thereby implying suboptimal adherence level. However, it is almost comparable with the study done in Adama Referral Hospital, Ethiopia.[30]

Distance from the hospital was one of the variables that found to be significantly associated with the adherence status of the respondents. Those patients from distant areas, especially when it was accompanied by poor infrastructure like lack of transportation, were less likely to be adherent as compared to study subjects who were closer. A study done in India reported similar finding.[31] If the patients need to cover long distance to come to the clinic, it will possibly affect their interest of collecting drugs from the health institution when they refill the medications.

According to our study low income and low educational level were significantly associated with the level of adherence to the treatment regimen. From different studies education and income have been identified as major socioeconomic determinants of adherence to anti-diabetic medication. Low income and low educational level have been associated with higher rates of nonadherence.[25,26,27,28,29,31,32] Consequently, poor economic base and illiteracy can result in the poor outcome of diabetes due to poor accessibility to healthcare services and self-care of diabetes. More educated patients were more adherent to therapy. Being less educated makes learning more difficult; as diabetes drug therapy gets more complex, patients are required to have more complex cognitive skills to be able to understand the prescribed drug therapy and to adhere to treatment for good glucose control.[32]

A variety of side effects were reported from different studies, for instance, a symptom of hypoglycemia, constipation or diarrhea, headaches, weight gain and water retention.[33,34] The most common side effects reported in our study was gastrointestinal side effects followed by hypoglycemic symptoms, weight gain, and headache. In addition, in this study, it was revealed that patients who experienced side effects to their medication were less adherent to the treatment regimen. Early identification and management of medication-related tolerability issue is important to achieve positive diabetes outcomes. Health care workers should give due attention to medication side effects and its impact on the successful management of especially chronic diseases that require long-term treatment.

According to our study patients on complex and multiple medications were nonadherent as compared to patients on one medication. This finding supports the other study which also reported that patients on complex drug regimen were less adherent to their treatment regimen.[35] SMBG is recognized to be useful and effective in achieving diabetes control. However, in this study only a few number of respondents were performing SMBG practices. The possible explanation for this could be either lack of awareness on importance SMBG in the management of diabetes, or there may be financial barriers to purchase the device.

Conclusion

The participants in the study area were moderately adherent to their anti-diabetic medications. Different factors of medication nonadherence were identified such as side effect and complexity of regimen, failure to remember, and sociodemographic factors such as educational level and monthly income. In general, adherence to prescribed medication and self-care practice was suboptimal among diabetic patients in the diabetic clinic of AGH. More effort is needed to increase the medication adherence of these patients so they can realize the full benefits of prescribed therapies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Jimma University for supporting this study.

References

- 1.Conget I. Diagnosis, classification and cathogenesis of diabetes mellitus. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2002;55:528–35. doi: 10.1016/s0300-8932(02)76646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nandeshwar S, Jamra V, Pal D. Indian diabetes risk score for screening of undiagnosed diabetic subjects of Bhopal city. Natl J Community Med. 2010;1:176–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shrestha SS, Shakya R, Karmacharya BM, Thapa P. Medication adherence to oral hypoglycemic agents among type II diabetic patients and their clinical outcomes with special reference to fasting blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin levels. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2013;11:226–32. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v11i3.12510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahfouz EM, Awadalla HI. Compliance to diabetes self-management in rural El-Mina, Egypt. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2011;19:35–41. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bener A, Zirie M, Janahi IM, Al-Hamaq AO, Musallam M, Wareham NJ. Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in a population-based study of Qatar. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;84:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Diabetes Mellitus Fact Sheet. 2014. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 09]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/

- 7.Feleke SA, Alemayehu M, Adane HT. Assessment of the level and associated factors with knowledge and practice of diabetes mellitus among diabetic patients attending at Felege Hiwot hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Clin Med Res. 2013;2:110–20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selvin E, Wattanakit K, Steffes MW, Coresh J, Sharrett AR. HbA1c and peripheral arterial disease in diabetes: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:877–82. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ming Y, Judy M. Self-care practices of Malaysian adults with diabetes and sub-optimal glycemic control. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;72:252–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W, Von Korff M, Ludman E, Lin E, et al. Influence of patient attachment style on self-care and outcomes in diabetes. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:720–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000138125.59122.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beckles GL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM, Herman WH, Aubert RE, Williamson DF. Population-based assessment of the level of care among adults with diabetes in the U. S. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1432–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delamater AM. Improving patient adherence. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1107–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnan PT, MacDonald TM, Morris AD. Adherence to prescribed oral hypoglycaemic medication in a population of patients with Type 2 diabetes: A retrospective cohort study. Diabet Med. 2002;19:279–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lifetime benefits and costs of intensive therapy as practiced in the diabetes control and complications trial. The diabetes control and complications trial research group. JAMA. 1996;276:1409–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paes AH, Bakker A, Soe-Agnie CJ. Impact of dosage frequency on patient compliance. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1512–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.10.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fatima AI, Omole M, Sheriff LO. Medication adherence amongst diabetic patients in a tertiary healthcare institution in central Nigeria. Trop J Pharm Res. 2014;13:997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalyango JN, Owino E, Nambuya AP. Non-adherence to diabetes treatment at Mulago Hospital in Uganda: Prevalence and associated factors. Afr Health Sci. 2008;8:67–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau D, Nau D. Oral antihyperglycemic medication nonadherence and subsequent hospitalization among individuals with type 2 diabetes. Am Diabetes Assoc. 2004;27:2149–53. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panahi Y, Mojtahedzadeh M, Beiraghdar F, Najafi A, Khajavi MR, Pazouki M, et al. Microalbuminuria in hyperglycemic critically Ill patients treated with insulin or metformin. Iran J Pharm Res. 2011;10:141–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Geest S, Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2:323. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kravitz RL, Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, DiMatteo MR, Rogers WH, Ordway L, et al. Recall of recommendations and adherence to advice among patients with chronic medical conditions. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1869–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamiru S, Alemseged F. Risk factors for cardiovascular diseases among diabetic patients in southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2010;20:121–8. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v20i2.69438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreau A, Aroles V, Souweine G, Flori M, Erpeldinger S, Figon S, et al. Patient versus general practitioner perception of problems with treatment adherence in type 2 diabetes: From adherence to concordance. Eur J Gen Pract. 2009;15:147–53. doi: 10.3109/13814780903329510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manjusha S, Madhu P, Atmatam P, Amit M, Ronak S. Medication adherence to anti-diabetic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;6:564–70. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taruna S, Juhi K, Dhasmana DC, Harish B. Poor adherence to treatment: A major challenge in diabetes. JIACM. 2014;15:26–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rwegerera GM. Adherence to anti-diabetic drugs among patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania- A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17:252. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.17.252.2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wabe NT, Angamo MT, Hussein S. Medication adherence in diabetes mellitus and self-management practices among type-2 diabetics in Ethiopia. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3:418–23. doi: 10.4297/najms.2011.3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yusuff KB, Obe O, Joseph BY. Adherence to anti-diabetic drug therapy and self-management practices among type-2 diabetics in Nigeria. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:876–83. doi: 10.1007/s11096-008-9243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelaw BK, Mohammed A, Tegegne GT, Defersha AD, Fromsa M, Tadesse E, et al. Nonadherence and contributing factors among ambulatory patients with antidiabetic medications in Adama Referral Hospital. J Diabetes Res 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/617041. 617041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner RC, Cull CA, Frighi V, Holman RR. Glycemic control with diet, sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Progressive requirement for multiple therapies (UKPDS 49). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. JAMA. 1999;281:2005–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.21.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gimenes HT, Zanetti ML, Haas VJ. Factors related to patient adherence to antidiabetic drug therapy. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2009;17:46–51. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692009000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pollack MF, Purayidathil FW, Bolge SC, Williams SA. Patient-reported tolerability issues with oral antidiabetic agents: Associations with adherence; treatment satisfaction and health-related quality of life. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:204–10. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mann DM, Ponieman D, Leventhal H, Halm EA. Predictors of adherence to diabetes medications: The role of disease and medication beliefs. J Behav Med. 2009;32:278–84. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colombo GL, Rossi E, De Rosa M, Benedetto D, Gaddi AV. Antidiabetic therapy in real practice: Indicators for adherence and treatment cost. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:653–61. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S33968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]