Protein-protein interactions (PPI's) are central to nearly all processes within cells, whether they are formed transiently in dynamic networks or permanently in macromolecular assemblies. There has been considerable progress towards our understanding of how proteins recognize their partners and how the energetics of their interactions are tuned.1 Nevertheless, the ability to predict or interfere with natural PPI's or engineer new ones remains a great challenge, owing to the fact that protein-protein docking processes are guided by the superposition of many weak, non-covalent bonds that spread over large and often flexible surfaces. Our goal is to utilize the strength, directionality and selectivity of metal-ligand interactions to control PPI's, thereby achieving specificity and affinity without requiring extensive binding surfaces. We describe here the Zn-mediated construction of a 16-helix architecture comprising four copies of cytochrome cb562(cyt cb562), a 4-helix bundle heme protein. Our results demonstrate that the self-organization of this macromolecule is controlled by metal coordination, with little or no thermodynamic bias from specific protein-protein contacts.

There are several factors that make cyt cb562 a good model system for investigating metal-mediated PPI's. It has a highly stable helical-bundle fold that is further strengthened through the engineering of covalent heme-polypeptide linkages into the parent protein, cyt b562.2, 3 As a result, its structure is not perturbed by modifications on its surface. The all-α-helical makeup of cyt cb562 leads to uniform surface features that facilitate the introduction of metal binding motifs. In addition, cyt cb562 has a rigid, roughly cylindrical shape, ideal for use as a building block for protein superstructures.

An earlier examination of the crystal structure of cyt cb562 revealed that the protein molecules are associated in pairs within the crystal lattice, despite being monomeric even at millimolar concentrations.3 The pairing is mediated by a crystal packing contact formed by the antiparallel alignment of Helix 3's (residues 56-80) from individual molecules. Based on this non-functional packing arrangement, we envisioned that metal-mediated interactions between cyt cb562 monomers could be forged through the incorporation of metal coordinating motifs onto the Helix 3 surface. To this end, we engineered a variant (His4-cb562) featuring two di-histidine motifs near the N- and C-termini of this helix at positions 59/63 and 73/77, which are located directly opposite each other in the crystal lattice and could potentially participate in interprotein metal coordination. Such di-His motifs placed at i and i+4 positions on an α-helix can coordinate metal ions with high affinity, and have been widely used for the assembly of metalloproteins and peptides.4-7 In addition, two Asp residues at positions 60 and 74 contained within each di-His motif were left intact in order to increase the likelihood of stable metal coordination.8

Our studies on metal-mediated PPI's have focused on late firstrow transition metal ions. Zn(II), in particular, should have a high binding affinity for the di-His motifs on His4-cb562 and exhibit rapid ligand exchange, which should prevent the formation of kinetically trapped protein-protein complexes. While dynamic light scattering measurements suggested the formation of multimeric His4-cb562 structures upon Zn(II) addition, aggregates were formed at metal:protein ratios exceeding 2:1, even at protein concentrations below 100 μM. These protein aggregates were readily dissolved upon EDTA addition or lowering the solution pH below 6, indicating that Zn-His coordination is responsible for protein oligomerization. At high Zn loadings, both di-His clamps are likely charged with metal, which can lead to multiple modes of interprotein coordination, and thereby, aggregation. To capture the structures of any homogenous protein assemblies, we screened for crystals of His4-cb562 at low Zn loadings, and obtained diffraction quality ones at less than 2:1 metal:protein ratios.

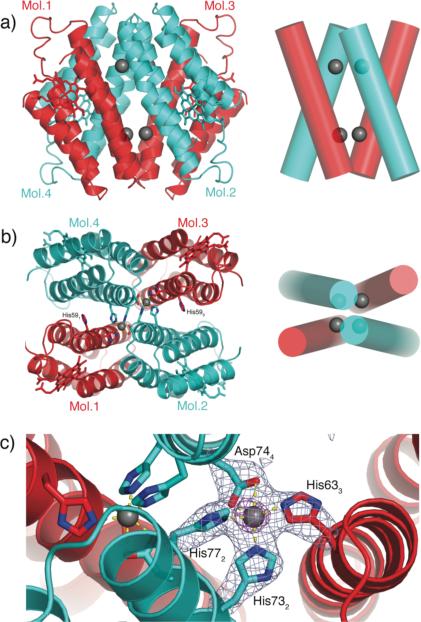

The 2.9-Å data reveal a unique quaternary structure (PDB ID: 2QLA) stabilized by four Zn(II) ions, wherein four His4-cb562 monomers form two interlaced V-shaped dimers to yield a 16-helix bundle (Figure 1).9 Each V-shape is formed by the parallel alignment of two cyt cb562 molecules related by a non-crystallographic two-fold symmetry axis, forming a ~37° interprotein angle. The two V's, on the other hand, are wedged into one another in an antiparallel fashion. Both the formation of the V's and their interlacing are achieved entirely by interprotein Zn-coordination. Each Zn shares an identical distorted tetrahedral coordination environment with ligands from three monomers (Figure 1c): the 73/77 di-His clamp from one molecule holds the Zn in a bidentate fashion, coordination of Asp74 from a second molecule stabilizes the V-arrangement between the two, and coordination of His63 from a third molecule locks the two V's together. This striking arrangement suggests that the formation of the protein assembly and metal coordination should be highly cooperative. Interestingly, the 59/63 di-His clamp is not utilized for bidentate coordination despite the likelihood that it has a similar Zn affinity as the 73/77 couple. The His59 sidechain is, in fact, H-bonded to Thr31 across the interface, but not involved in metal coordination (Figure 1b). The discrimination by Zn between the two di-His motifs is in accord with the dynamic self-assembly of the cyt cb562 superstructure: the lability of Zn likely permits the exploration of different coordination geometries, resulting in the formation of the thermodynamically most stable quaternary structure.

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of the 4 Zn-4 His4-cb562 assembly. Pairs of protein molecules that form the V-shaped dimers are colored alike. Zn ions are shown as grey spheres. (a) View of the assembly parallel to the non-crystallographic twofold axis and the corresponding cylindrical representation of Helix 3's involved in Zn coordination; (b) view down the non-crystallographic twofold axis; (c) close-up view of the Zn coordination environment and simulated-annealing Fo-Fc omit electron density map (grey, 4σ; purple, 12σ). The parent molecules for metal ligands are shown in subscripts.

The interfaces between the four His4-cb562 monomers feature a large number of polar interactions and bury a surface area exceeding 5000 Å2. While the surface of cyt cb562 is not optimized for self-association and the interfacial contacts are likely to be non-specific, they may collectively impart sufficient thermodynamic driving force to bias the formation of the observed assembly. To probe the existence of any metal-independent pre-organization between the His4-cb562 monomers and to examine their metal-dependent oligomerization behavior in solution, we carried out NMR and sedimentation velocity (SV) experiments. Indicative of a monomeric species, the 1D-proton-NMR spectra of His4-cb562 at high protein concentrations (> 1 mM) feature significant chemical shift dispersion. Upon addition of one equivalent of Zn, the peaks broaden considerably, as expected from the formation of a high-order oligomer. In order to quantitatively determine the hydrodynamic properties of this oligomer, we utilized pulsed field gradient (PFG) diffusion NMR spectroscopy.10 These experiments yielded diffusion coefficients of 1.17 × 10−6 and 0.785 × 10−6 cm2/s for the protein in the absence and presence of one equivalent of Zn, respectively, with corresponding Stokes radii of 17.6 Å and 26 Å. The ~ 9-Å expansion is consistent with the formation of a tetramer.

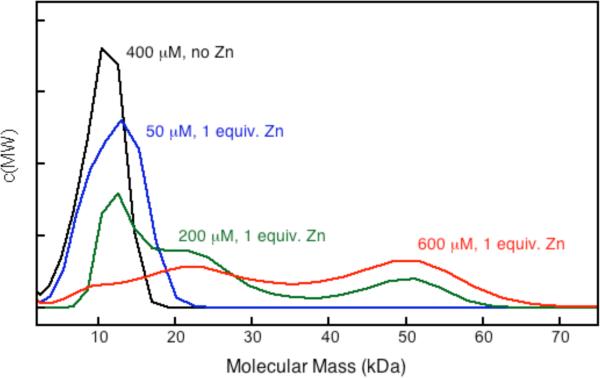

The molecular mass distributions of His4-cb562 species determined by SV measurements under different solution conditions are shown in Figure 2. In the absence of Zn, the protein is monomeric at all concentrations tested (up to 400 μM), with a single maximum at ~11500 Da (12328 Da actual). Upon addition of Zn, two new peaks centered at ~ 22 kDa and ~ 50 kDa emerge at the expense of the monomeric species. The 22-kDa species presumably corresponds to either one of the two possible dimeric halves of the 16-helix bundle: a) the V-shaped His4-cb562 dimer (e.g., Mol1 and Mol3 in Figure 1) held together by two Zn ions with His73/77 and Asp74 coordination, or b) the antiparallel dimer (e.g., Mol1 and Mol4) with His 73/77 and His 63 coordination. These two species can further dimerize into the observed 16-helix bundle structure through His63-Zn or Asp74-Zn coordination, respectively, and become the predominant species at high protein concentrations.

Figure 2.

Molecular mass distributions of His4-cb562 species determined by sedimentation velocity experiments. The distributions are normalized with respect to the area covered under the curves.

Metal coordination chemistry has been used successfully for directing the formation of discrete non-biological supramolecular complexes.11 We have demonstrated here that protein building blocks with non-interacting surfaces can be assembled into self-healing superstructures through metal coordination. Such chemical control of protein-protein interactions paves the way for the generation of new biomaterials and manipulation of cellular processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Drs. Arnold L. Rheingold and Antonio DiPasquale for their help with X-ray data collection, and the Komives Lab, Dr. Andrew Herr (University of Cincinnati) and Dr. Xuemei Huang for their assistance with SV and NMR experiments. This work was supported by the University of California, San Diego, a Hellman Faculty Scholar Award (F.A.T.), N.I.H. Molecular Biophysics Training Grant (E.N.S), and N.S.F. (Instrumentation Grant 0634989 to A.L.R.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Materials and methods for protein expression/purification/characterization, experimental details for DLS, NMR and SV measurements, crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics.

References

- 1.a Shoemaker BA, Panchenko AR. PLos Comput. Biol. 2007;3:595–601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Vizcarra CL, Mayo SL. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005;9:622–626. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kortemme T, Baker D. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d DeLano WL. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:14–20. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Sheinerman FB, Norel R, Honig B. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:153–159. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen JWA, Barker PD, Ferguson SJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:52075–52083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faraone-Mennella J, Tezcan FA, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10504–10511. doi: 10.1021/bi060242x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold FH, Haymore BL. Science. 1991;252:1796–1797. doi: 10.1126/science.1648261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghadiri MR, Choi C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:1630–1632. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handel TM, Williams SA, Degrado WF. Science. 1993;261:879–885. doi: 10.1126/science.8346440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krantz BA, Sosnick TR. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:1042–1047. doi: 10.1038/nsb723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The only other His residue (102) in this variant is coordinated to the heme iron in the protein core and thus unable to participate in PPI's.

- 9.Though only at 2.9-Å resolution, the crystallographic data quality is sufficient to determine the architecture of the protein assembly, the configurations of most sidechains, and the metal coordination.

- 10.Altieri AS, Hinton DP, Byrd RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:7566–7567. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a Lehn JM. Science. 2002;295:2400–2403. doi: 10.1126/science.1071063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Leininger S, Olenyuk B, Stang PJ. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:853–907. doi: 10.1021/cr9601324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Caulder DL, Raymond KN. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:975–982. [Google Scholar]; d Holliday BJ, Mirkin CA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Eng. 2001;40:2022–2043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Ockwig NW, Delgado-Friedrichs O, O'Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Acc. Chem. Res. 2005;38:176–182. doi: 10.1021/ar020022l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.