Abstract

It has remained an enigma how hepatitis C viral (HCV) RNA can persist in the liver of infected patients for many decades. With the recent discovery of roles for microRNAs in gene expression, it was reported that the HCV RNA genome subverts liver-specific microRNA miR-122 to protect its 5′ end from degradation by host cell exoribonucleases. Sequestration of miR-122 in cultured liver cells and in the liver of chimpanzees by small, modified antisense RNAs resulted in dramatic loss of HCV RNA and viral yield. This finding led to the first successful human trial in which subcutaneous administration of antisense molecules against miR-122 lowered viral yield in HCV patients, without the emergence of resistant virus. In this review, the authors summarize the molecular mechanism by which miR-122 protects the HCV RNA genome from degradation by exoribonucleases Xrn1 and Xrn2 and discuss the application of miR-122 antisense molecules in the clinic.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, microRNA, exoribonucleases

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a hepatotropic, single-stranded, positive-sense, enveloped RNA virus that belongs to the family Flaviviridae and the genus Hepacivirus. The liver is the primary target organ, with the hepatocyte being its primary target cell. Hepatitis C virus can establish persistent infections that lead to chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.1 With an estimated 170 million people chronically infected worldwide,2 and more than 350, 000 people dying from HCV-related liver disease each year, HCV infection is a serious global health problem.

Current therapies, based on the protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir, in combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, have been ineffective and result in the emergence of resistant viruses (reviewed in3). However, the recently developed compound Sofosbuvir (Gilead, Foster City, CA), which is a nucleoside analog inhibitor of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase NS5B, has shown a phenomenal sustained virological response rate of over 95% and is clearly the most effective treatment to combat HCV in the absence of a vaccine.

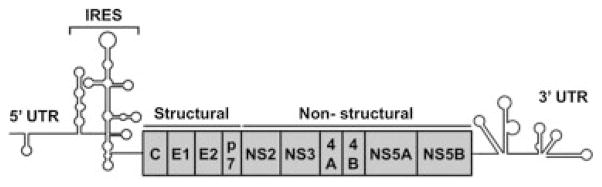

The HCV RNA genome is 9.6 kilobases in size, and it contains conserved 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) that are important for viral replication and translation (Fig. 1). An internal ribosome entry site directs the synthesis of a large, 3010 amino acid viral polyprotein, which is co-and posttranslationally cleaved by host and viral proteases to yield 10 mature structural and nonstructural (NS) proteins, each with distinct functions (Fig. 1). The structural proteins consist of two envelope glycoproteins (E1 and E2), both of which are targets of host antibody responses, and the core protein, which interacts with progeny viral genomes for assembly of the virus. The nonstructural proteins NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B form a complex with viral RNA to initiate replication on specialized endoplasmic reticulum-derived membranes, the so-called membranous web.4 Viral assembly initiates at the interface of the replication complex and cytoplasmic lipid droplets, which are cellular lipid storage organelles important for lipid homeostasis. The assembly complex then follows the cellular host pathway for lipoprotein production to achieve the secretion of very low-density lipoprotein- like lipoviral particles.

Fig. 1.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA genome. The HCV RNA genome consists of a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA molecule. It contains one long open reading frame (ORF) that is flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs). Internal ribosomal entry site- (IRES-) mediated translation of the ORF gives rise to a polyprotein that is co-and posttranslationally processed into structural (C, E1, E2) and nonstructural (p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5B) viral proteins.

A large number of virus-host interactions take place in virus-infected cells. For example, viruses usurp certain host factors to aid in the translation and replication of the viral genome. On the other hand, many viruses counteract the host innate immune system by encoding factors that mimic host cell ligands to inhibit host cell signaling, or proteinases that degrade factors of the innate immune response. In this review, we describe the subversion of the liver-specific micro-RNA miR-122 by HCV to protect its RNA genome from degradation by host 5′-3′ exoribonucleases. Furthermore, we discuss the findings that overexpression of specific micro-RNAs reduce the intracellular abundance of HCV RNA, suggesting a novel antiviral approach to lower HCV viral yield.

The Intricate Biogenesis of microRNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) comprise a large class of endogenous, noncoding, single-stranded RNAs of 19 to 25 nucleotides in length. These short RNA molecules function in posttranscriptional gene silencing by base pairing with their target mRNAs to promote mRNA target cleavage and translational repression. This is accomplished in most cases by interaction of the seed sequences in miRNAs (nucleotides 2–8) with complementary seed match sequences, located in 3′ noncoding regions of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs), to inhibit mRNA function.5,6 MiRNAs are one of the largest gene families, accounting for approximately 1% of the human genome and modulating the expression of at least one third of all human mRNAs.7 MiRNAs can function in a tissue-specific manner, and are important for diverse biological processes such as development, cell proliferation, apoptosis, cancer, and viral infection.

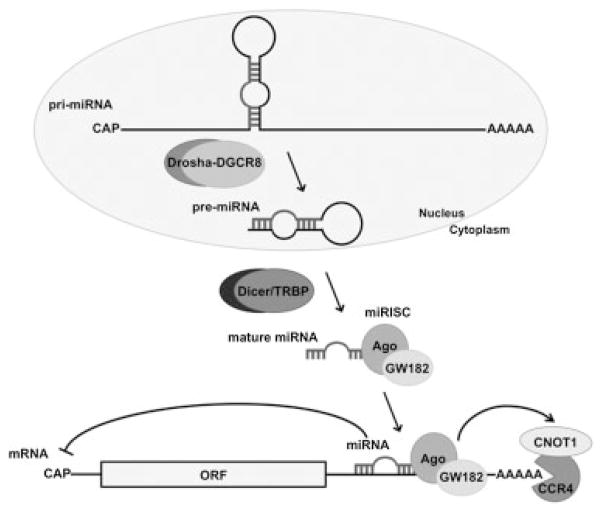

Genomic positions of miRNA genes indicate that they can reside as distinct transcriptional units or in polycistronic clusters from where they can be transcribed as distinct miRNAs.8 Unlike most small RNAs that are transcribed by RNA polymerase III (Pol III), the transcription of miRNA genes is mediated by Pol II. Long primary transcripts (pri-miRNAs) that contain 5′ cap structures and 3′ poly(A) tails, and a local RNA hairpin structure are generated by Pol II (Fig. 2).9 The subsequent processing of the pri-miRNA occurs in two steps, first in the nucleus to precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA), and then in the cytoplasm to mature miRNA. In the nucleus, the RNase III–type enzyme Drosha, aided by its cofactor DGCR8, cleaves the stem-loop structure of the pri-miRNA to release a pre-miRNA of approximately 70 nucleotides (Fig. 2). The pre-miRNA hairpin is exported to the cytoplasm by the nuclear transport receptor exportin-5. In the cytoplasm, the pre-miRNA is subjected to a second processing step by another RNase III enzyme called Dicer, aided by its cofactor TRBP, to give rise to an approximately 22-nucleotide miRNA duplex (Fig. 2).10 The less stable of the two strands in the duplex RNA is incorporated into an effector complex, known as the miRNA-containing RNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC), that contains one of the four Argonaute (Ago) proteins and factor GW182. The miRISC causes translational repression by inhibition of ribosome recruitment to the capped 5′ end of the mRNA and, subsequently, degradation of the target mRNA by activation of the CNOT1/CCR4 deadenylase complex (Fig. 2).11–13

Fig. 2.

MicroRNA (miRNA) processing pathway. Transcription of the primary miRNA transcript (pri-miRNA) by RNA polymerase II and pri-miRNA cleavage by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex occurs in the nucleus. The resulting precursor hairpin (pre-miRNA) of 50 to 70 nucleotides is exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. In the cytoplasm, the RNAse Dicer, in complex with the double stranded RNA-binding protein TRBP, cleaves the pre-miRNA hairpin to its mature length. The miRNA duplex is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex miRISC (Ago1–4, GW182 in mammals). One of the duplex strands is preferentially retained in miRISC, where it guides miRISC to silence target mRNAs by mRNA translational repression and deadenylation by CNOT1/CCR4.

Remarkable progress has been made in our understanding of miRNA biogenesis and function in the last few years. In-depth studies of the mechanisms that are used by miRNAs to control viral infection and how viruses subvert potential inhibitory miRNAs are currently under intense scrutiny.14 In the next section, we will discuss how the HCV RNA genome subverts the liver-specific miR-122 to protect its RNA genome.

Subversion of Liver-Specific miR-122 by the HCV RNA Genome

The nucleotide sequences of the highly abundant, liver-specific miRNA-122 are highly conserved from zebrafish to humans.15 With approximately 66,000 copies per cell, miR-122 constitutes over 70% of the total miRNA population of the human liver.16 Extensive studies have revealed the important functions of miR-122 in lipid metabolism. Specifically, inhibition of miR-122 by antisense miR-122 oligonucleotides dramatically reduced fatty acid and sterol biosynthesis rates in mice and humans.17–19 Thus, miR-122 normally upregulates fatty acid and sterol biosynthesis, likely through the downregulation of an inhibitor of these pathways.

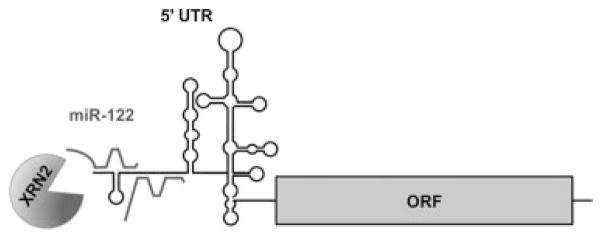

Curiously, miR-122 plays a crucial role in the HCV life cycle, as it positively modulates HCV RNA abundance. It was noted that HCV RNA and protein abundances dramatically decreased when miR-122 was sequestered by antisense miR-122 oligonucleotides.20 The effects of miR-122 on HCV RNA abundance were studied by Machlin et al21 using a miR-122 mutational analysis approach. It was discovered that miR-122 forms an extensive oligomeric complex with the 5′ end sequences of HCV RNA. This unique oligomeric complex likely protects the viral genome from nucleolytic degradation or sensors of the immune response21(Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Hepatitis C virus– (HCV–) miR-122 interactions. Two molecules of miR-122 form extensive base-pairing interactions with the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) of the HCV RNA genome to protect it from Xrn2-mediated 5′-3′ degradation. The viral 5′ UTR and open reading frame (ORF) are indicated.

Li et al22 reported that miR-122 can protect the viral RNA genome from degradation by the 5′-3′ exoribonuclease Xrn1. However, depletion of Xrn1 did not allow replication of the viral RNA in the absence of miR-122. We discovered that Xrn2, the Xrn1 paralogue, is responsible for the degradation of the viral RNA genome, and that depletion of Xrn2 by siRNAs allowed the viral RNA to replicate in the absence of miR-122.23 To reconcile these differences, it is important to understand the roles of these two exoribonucleases in cellular and viral metabolism.

Roles of Exoribonucleases Xrn1 and Xrn2 in Cellular and Viral RNA Turnover

Exoribonucleases 1 (Xrn1) and 2 (Xrn2) are evolutionarily conserved 5′-3′ exoribonucleases that were first identified in Saccharomyces cereviceae.24–27 Xrn1 (175 kDa) and Xrn2 (108 kDa) show extensive conservation within their N-terminal regions and share an enzymatic site.28 Sequence conservation is much lower outside the XRN active site domain. For example, the C-terminus of Xrn1 extends much further than the C-terminus of Xrn2. Xrn1 is localized in the cytoplasm,29 whereas Xrn2 is predominantly localized in the nucleus.30 Orthologs of the exoribonucleases have been identified in most model organisms, suggesting important functions for these nucleases.31–36

Xrn1 is responsible for the degradation of a wide range of cytoplasmic RNAs, including mRNAs that have undergone attack by RNAi or nonsense-mediated decay. On the other hand, Xrn2 plays important functions in RNA metabolism in the nucleus, such as processing of ribosomal RNAs and small nucleolar RNAs,37 and it is crucial for the transcription termination of Poll II.38–41 Although Xrn1 and Xrn2 show redundancy in the processing of some of their substrates RNAs, only XRN2 is essential in S. cerevisiae.24

These exoribonucleases have also been found to play roles in the degradation of the HCV RNA genome. Xrn1 was identified as a restriction factor for HCV by Jones et al. 42 Li et al22 found that siRNA-mediated depletion of Xrn1 slowed the decay rate of HCV RNA in liver Huh7.5 cells that were stably infected with a genotype 1a virus (H77S.3), whereas depletion of PM/Scl-100, a component of the exosome, had no effects on the decay rates of viral RNA. Xrn1 depletion also enhanced viral RNA abundance and production of infectious virus. However, depletion of Xrn1 was reported by others to have no effects on HCV abundance.43–45 We reported that Xrn2 modulates HCV RNA abundance. Specifically, depletion of Xrn2 did not alter translation or replication rates of HCV RNA, but affected RNA stability. Importantly, during sequestration of miR-122, Xrn2 depletion restored HCV RNA abundance, arguing that Xrn2 depletion eliminates the miR-122 requirement for viral RNA stability.23 The cause for the different effects seen by different investigators has not been sorted out yet. It is possible that different HCV RNA complexes exist in infected cells, only some of which may contain bound miR-122, or some complexes may be specially localized because of their engagement in translation, replication, or packaging. Thus, Xrn1 and Xrn2 seem to target distinct complexes that display different requirements for miR-122.

Roles for Components of the MicroRNA Pathway during HCV Infection

Because miR-122 plays an essential role in the life cycle of HCV, it was of interest to examine whether factors of the microRNA pathway that generate mature miR-122 affect HCV RNA abundance. Wilson et al46 investigated the role of RISC proteins during HCV infection and reported that Ago2 was required for miR-122 to enhance HCV RNA accumulation and translation. Ago2 has also been implicated in miR-122-mediated stabilization of HCV RNA.47,48 In addition, Dicer and TRBP were also found to be required for efficient HCV replication.49 Dicer and TRBP are essential for pre-miR-122 processing and activity, arguing that processing of miR-122 by Dicer and TRBP is required for miR-122 function on HCV RNA abundance. In an interesting twist, Cox et al50 also noted that pre-miR-122 can fulfill the functions of mature miR-122 in stabilization of the HCV RNA genome, suggesting that Dicer/TRBP complexes are needed for the generation of additional microRNAs, other than miR-122, to aid in HCV RNA amplification.

Effects of Non-miR-122 Host Cell miRNAs on HCV RNA Amplification

Binding sites for several miRNAs, other than miR-122, have been detected on the HCV RNA genome. For example, Pedersen et al51 reported that miR-448 and miR-196 directly target the RNA genome of HCV. MiR-448 binds to the coding sequence of core, whereas miR-196 interacts with a sequence within NS5A (Table 1). Overexpression of these miRNAs reduced HCV RNA replication.51 Interestingly, miR-448 and miR-196 are positively modulated by interferon alpha/beta (IFNα/β), suggesting that the IFN network can use miRNAs to combat viral infections.

Table 1.

Summary of microRNAs that interact with the HCV RNA genome

| miRNA | Target | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-199a* | Domain II of HCV IRES | Inhibits HCV RNA replication | 52 |

| miR-448 | HCV core coding region | Inhibits HCV RNA replication | 51 |

| miR-196 | HCV NS5A coding region | Inhibits HCV RNA replication | 51 |

| let-7b | Stem loop IV of 5′ UTR HCV NS5B coding region | Inhibits HCV RNA replication | 57 |

| miR-122 | HCV 5′ UTR | Enhances HCV RNA replication and translation | 22 |

| 48 | |||

| 47 | |||

| 21 | |||

| 46 | |||

| 61 | |||

| 20 |

Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; IRES, internal ribosomal entry site; UTR, untranslated region.

In addition, Murakami et al52 used a miRNA target-search algorithm to identify miRNAs that target the HCV RNA genome. MiR-199a* was identified and its binding site was located in stem loop (SL) II of the 5′ UTR of HCV, downstream of the binding sites for miR-122. The miR-199a* binding sites on the HCV genome are conserved across genotypes. It was found that miR-199a* overexpression inhibited HCV RNA replication in Huh7–1b or -2a HCV replicons cells, whereas miRNA sequestration using antisense oligonucleotides caused an increase in viral RNA replication. This work suggests that miRNAs can negatively regulate HCV RNA replication. The antiviral activity of miR-199a* is dependent on its direct interaction with the viral genome because mutations that altered the binding site eliminated the effects of miR-199a* on HCV RNA abundance. Because the secondary structure of SLII is important for both translation and replication or the viral genome,53 the exact mechanism by which miR-199a* reduces HCV RNA abundance remains unknown.

Let7-b, which is known to function as a tumor suppressor miRNA in lung cancer7,49,54 and in high-risk prostate cancer,55 and to contribute to the epithelial immune response against Helicobacter pylori infection,56 has also been shown to be a regulator of HCV replication.57 Cheng et al57 showed that let-7b suppresses HCV replication, but has no effect on HCV RNA translation. Their mutational analysis also showed that let-7b directly interacts with the HCV RNA genome at different positions to modulate viral RNA abundance. Two let-7b binding sites are located within the coding region of NS5B, and in one in SLIV of the 5′ UTR (Table 1). All of these sites are conserved among HCV genotypes and were shown to bind let-7b. Another potential target site was found in SL1 at the 3′ UTR and does not appear to be functional. The main caveat with effects on non-miR-122 molecules on HCV RNA amplification is that all experimental protocols involve overexpression of the examined microRNAs. In contrast to miR-122, these miRNAs are much less abundant in liver cells than miR-122, and it is currently unknown whether they affect HCV gene expression at physiological concentrations.

Loss of HCV in Patients Treated with Locked Nucleic Acids that Sequester miR-122 in the Liver

The loss of HCV RNA abundance and virus yield by antisense oligonucleotides directed against miR-122 in cultured cells encouraged Santaris Pharma (Copenhagen, Denmark) to conduct preclinical trials in chimpanzees infected with HCV. It was found that a locked nucleic acid directed against miR-122, termed miravirsen, reduced viral load by 2.6 logs in the animals without displaying adverse effects, and importantly, without the emergence of drug resistance.58 Pharmacokinetic analysis showed that miravirsen was secreted from the animals after 7 weeks of administration. Subsequently, in phase 2 clinical trials, patients who had not been treated before with any antiviral compound, were subcutaneously injected with miravirsen once a week for 5 weeks.18 At the highest dose of 7 mg/kg, the viral load in treated patients declined by 3 logs and was undetectable in four out of nine patients.18 Again, there was no evidence of the appearance of escape mutations, at least in the viral noncoding regions that include the binding sites for miR-122.18 Follow-up studies with these patients will reveal whether miravirsen is efficacious and safe in the long term. It is important to note that mice that lack the gene for miR-122 do have a higher risk of developing a fatty liver and hepatocellular carcinoma.59,60 Thus, miR-122 functions as a tumor-suppressor gene and should only be sequestered short term. Despite this caution, short-term application of an antagomir directed against miR-122 together with the application of a long-term powerful and novel therapeutic agent may quickly lower viral yield by several logs. This could allow the innate and humoral immune responses to take over the infection.

Concluding Remarks

The past few years have revealed that mature miRNAs and pre-miRNAs can display astonishing diverse functions. In infected liver, HCV can subvert both pre-miR-122 and mature miR-122 to aid in the protection of the viral RNA genome from degradation by host cell 5′-3′ exoribonucleases. Because the liver is amenable to targeting miRNAs with small anti-sense molecules, sequestration of miR-122 presents an Achilles’ heel for HCV. Long-term phase 2b and phase 3 clinical trials with antisense molecules directed against miR-122 will reveal whether sequestration of miR-122 is an additional antiviral therapeutic venue in addition to the classical application of compounds that inactivate virus-encoded enzymes.

Acknowledgments

Studies in the authors’ laboratory were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI47365, AI069000). CDS acknowledges support from the Stanford Genome Training Program (SGTP; NIH/NHGRI).

Abbreviations

- Ago2

Argonaute 2

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- mRNAs

messenger RNAs

- miRNAs

microRNAs

- miRISC

microRNA-induced silencing complex

- NS

nonstructural

- pol II, III

RNA polymerase II, III

- pre-miRNA

precursor microRNA

- pri-miR

primary microRNA

- SL

stem loop

- UTR

untranslated region

References

- 1.Hoofnagle JH. Course and outcome of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36(5, Suppl 1):S21–S29. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavanchy D. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(2):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casey LC, Lee WM. Hepatitis C virus therapy update 2013. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29(3):243–249. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835ff972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartenschlager R, Penin F, Lohmann V, André P. Assembly of infectious hepatitis C virus particles. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19(2):95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannell IG, Kong YW, Bushell M. How do microRNAs regulate gene expression? Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36(Pt 6):1224–1231. doi: 10.1042/BST0361224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115(7):787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs - microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(4):259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001;294(5543):853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee Y, Jeon K, Lee JT, Kim S, Kim VN. MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J. 2002;21(17):4663–4670. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sontheimer EJ, Carthew RW. Silence from within: endogenous siRNAs and miRNAs. Cell. 2005;122(1):9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Boland A, Kuzuo ğlu-Öztürk D, et al. A DDX6-CNOT1 complex and W-binding pockets in CNOT9 reveal direct links between miRNA target recognition and silencing. Mol Cell. 2014;54(5):737–750. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meijer HA, Kong YW, Lu WT, et al. Translational repression and eIF4A2 activity are critical for microRNA-mediated gene regulation. Science. 2013;340(6128):82–85. doi: 10.1126/science.1231197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Djuranovic S, Nahvi A, Green R. miRNA-mediated gene silencing by translational repression followed by mRNA deadenylation and decay. Science. 2012;336(6078):237–240. doi: 10.1126/science.1215691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cullen BR. Viruses and microRNAs: RISCy interactions with serious consequences. Genes Dev. 2011;25(18):1881–1894. doi: 10.1101/gad.17352611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerlach D, Kriventseva EV, Rahman N, Vejnar CE, Zdobnov EM. miROrtho: computational survey of microRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D111–D117. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang J, Nicolas E, Marks D, et al. miR-122, a mammalian liver-specific microRNA, is processed from hcr mRNA and may down-regulate the high affinity cationic amino acid transporter CAT-1. RNA Biol. 2004;1(2):106–113. doi: 10.4161/rna.1.2.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esau C, Davis S, Murray SF, et al. miR-122 regulation of lipid metabolism revealed by in vivo antisense targeting. Cell Metab. 2006;3(2):87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janssen HL, Reesink HW, Lawitz EJ, et al. Treatment of HCV infection by targeting microRNA. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1685–1694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krützfeldt J, Rajewsky N, Braich R, et al. Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with ‘antagomirs’. Nature. 2005;438(7068):685–689. doi: 10.1038/nature04303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific microRNA. Science. 2005;309(5740):1577–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1113329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machlin ES, Sarnow P, Sagan SM. Masking the 5′ terminal nucleotides of the hepatitis C virus genome by an unconventional microRNA-target RNA complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(8):3193–3198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012464108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Masaki T, Yamane D, McGivern DR, Lemon SM. Competing and noncompeting activities of miR-122 and the 5′ exonuclease Xrn1 in regulation of hepatitis C virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(5):1881–1886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213515110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sedano CD, Sarnow P. Subversion of liver-specific miR-122 by hepatitis C virus RNA genome to protect against exoribonuclease Xrn2. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16(2):257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amberg DC, Goldstein AL, Cole CN. Isolation and characterization of RAT1: an essential gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae required for the efficient nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of mRNA. Genes Dev. 1992;6(7):1173–1189. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larimer FW, Stevens A. Disruption of the gene XRN1, coding for a 5′——3′ exoribonuclease, restricts yeast cell growth. Gene. 1990;95(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90417-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens A. An exoribonuclease from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: effect of modifications of 5′ end groups on the hydrolysis of substrates to 5′ mononucleotides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978;81(2):656–661. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91586-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens A. Purification and characterization of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae exoribonuclease which yields 5′-mononucleotides by a 5′ leads to 3′ mode of hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 1980;255(7):3080–3085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang JH, Xiang S, Xiang K, Manley JL, Tong L. Structural and biochemical studies of the 5′ → 3′ exoribonuclease Xrn1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(3):270–276. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heyer WD, Johnson AW, Reinhart U, Kolodner RD. Regulation and intracellular localization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strand exchange protein 1 (Sep1/Xrn1/Kem1), a multifunctional exonuclease. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(5):2728–2736. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson AW. Rat1p and Xrn1p are functionally interchangeable exoribonucleases that are restricted to and required in the nucleus and cytoplasm, respectively. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(10):6122–6130. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.6122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Käslin E, Heyer WD. A multifunctional exonuclease from vegetative Schizosaccharomyces pombe cells exhibiting in vitro strand exchange activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(19):14094–14102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bashkirov VI, Scherthan H, Solinger JA, Buerstedde JM, Heyer WD. A mouse cytoplasmic exoribonuclease (mXRN1p) with preference for G4 tetraplex substrates. J Cell Biol. 1997;136(4):761–773. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.4.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Till DD, Linz B, Seago JE, et al. Identification and developmental expression of a 5′-3′ exoribonuclease from Drosophila melanogaster. Mech Dev. 1998;79(1–2):51–55. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kastenmayer JP, Green PJ. Novel features of the XRN-family in Arabidopsis: evidence that AtXRN4, one of several orthologs of nuclear Xrn2p/Rat1p, functions in the cytoplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(25):13985–13990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.25.13985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li CH, Irmer H, Gudjonsdottir-Planck D, et al. Roles of a Trypanosoma brucei 5′->3′ exoribonuclease homolog in mRNA degradation. RNA. 2006;12(12):2171–2186. doi: 10.1261/rna.291506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chatterjee S, Grosshans H. Active turnover modulates mature microRNA activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2009;461(7263):546–549. doi: 10.1038/nature08349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petfalski E, Dandekar T, Henry Y, Tollervey D. Processing of the precursors to small nucleolar RNAs and rRNAs requires common components. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(3):1181–1189. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brannan K, Kim H, Erickson B, et al. mRNA decapping factors and the exonuclease Xrn2 function in widespread premature termination of RNA polymerase II transcription. Mol Cell. 2012;46(3):311–324. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim M, Krogan NJ, Vasiljeva L, et al. The yeast Rat1 exonuclease promotes transcription termination by RNA polymerase II. Nature. 2004;432(7016):517–522. doi: 10.1038/nature03041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearson EL, Moore CL. Dismantling promoter-driven RNA polymerase II transcription complexes in vitro by the termination factor Rat1. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(27):19750–19759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.434985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.West S, Gromak N, Proudfoot NJ. Human 5′ —>3′ exonuclease Xrn2 promotes transcription termination at co-transcriptional cleavage sites. Nature. 2004;432(7016):522–525. doi: 10.1038/nature03035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones DM, Domingues P, Targett-Adams P, McLauchlan J. Comparison of U2OS and Huh-7 cells for identifying host factors that affect hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(Pt 9):2238–2248. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.022210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ariumi Y, Kuroki M, Kushima Y, et al. Hepatitis C virus hijacks P-body and stress granule components around lipid droplets. J Virol. 2011;85(14):6882–6892. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02418-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pager CT, Schütz S, Abraham TM, Luo G, Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance and virus release by dispersion of processing bodies and enrichment of stress granules. Virology. 2013;435(2):472–484. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scheller N, Mina LB, Galão RP, et al. Translation and replication of hepatitis C virus genomic RNA depends on ancient cellular proteins that control mRNA fates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(32):13517–13522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906413106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson JA, Zhang C, Huys A, Richardson CD. Human Ago2 is required for efficient microRNA 122 regulation of hepatitis C virus RNA accumulation and translation. J Virol. 2011;85(5):2342–2350. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02046-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roberts AP, Lewis AP, Jopling CL. miR-122 activates hepatitis C virus translation by a specialized mechanism requiring particular RNA components. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(17):7716–7729. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimakami T, Yamane D, Jangra RK, et al. Stabilization of hepatitis C virus RNA by an Ago2-miR-122 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(3):941–946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112263109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang C, Huys A, Thibault PA, Wilson JA. Requirements for human Dicer and TRBP in microRNA-122 regulation of HCV translation and RNA abundance. Virology. 2012;433(2):479–488. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cox EM, Sagan SM, Mortimer SA, Doudna JA, Sarnow P. Enhancement of hepatitis C viral RNA abundance by precursor miR-122 molecules. RNA. 2013;19(12):1825–1832. doi: 10.1261/rna.040865.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pedersen IM, Cheng G, Wieland S, et al. Interferon modulation of cellular microRNAs as an antiviral mechanism. Nature. 2007;449(7164):919–922. doi: 10.1038/nature06205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murakami Y, Aly HH, Tajima A, Inoue I, Shimotohno K. Regulation of the hepatitis C virus genome replication by miR-199a. J Hepatol. 2009;50(3):453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Friebe P, Lohmann V, Krieger N, Bartenschlager R. Sequences in the 5′ nontranslated region of hepatitis C virus required for RNA replication. J Virol. 2001;75(24):12047–12057. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12047-12057.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Esquela-Kerscher A, Trang P, Wiggins JF, et al. The let-7 microRNA reduces tumor growth in mouse models of lung cancer. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(6):759–764. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.6.5834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schubert M, Spahn M, Kneitz S, et al. Distinct microRNA expression profile in prostate cancer patients with early clinical failure and the impact of let-7 as prognostic marker in high-risk prostate cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e65064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teng GG, Wang WH, Dai Y, Wang SJ, Chu YX, Li J. Let-7b is involved in the inflammation and immune responses associated with Helicobacter pylori infection by targeting Toll-like receptor 4. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e56709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng JC, Yeh YJ, Tseng CP, et al. Let-7b is a novel regulator of hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(15):2621–2633. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0940-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elmén J, Lindow M, Schütz S, et al. LNA-mediated microRNA silencing in non-human primates. Nature. 2008;452(7189):896–899. doi: 10.1038/nature06783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsu SH, Wang B, Kota J, et al. Essential metabolic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumorigenic functions of miR-122 in liver. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(8):2871–2883. doi: 10.1172/JCI63539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsai WC, Hsu SD, Hsu CS, et al. MicroRNA-122 plays a critical role in liver homeostasis and hepatocarcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(8):2884–2897. doi: 10.1172/JCI63455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henke JI, Goergen D, Zheng J, et al. MicroRNA-122 stimulates translation of hepatitis C virus RNA. EMBO J. 2008;27(24):3300–3310. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]