Abstract

Background

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is a common condition in patients with end-stage renal disease and is associated with osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. Despite improved medical treatment, parathyroidectomy (PTX) is still necessary for many patients on renal replacement therapy. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of PTX on patient survival.

Methods

A nested index-referent study was performed within the Swedish Renal Registry (SRR). Patients on maintenance dialysis and transplantation at the time of PTX were analysed separately. The PTX patients in each of these strata were matched for age, sex and underlying renal diseases with up to five referent patients who had not undergone PTX. To calculate survival time and hazard ratios, indexes and referents were assigned the calendar date (d) of the PTX of the index patient. The risk of death after PTX was calculated using crude and adjusted Cox proportional hazards regressions.

Results

There were 20 056 patients in the SRR between 1991 and 2009. Of these, 579 (423 on dialysis and 156 with a renal transplant at d) incident patients with PTX were matched with 1234/892 non-PTX patients. The adjusted relative risk of death was a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.80 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.65–0.99] for dialysis patients at d who had undergone PTX compared with matched patients who had not. Corresponding results for the patients with a renal allograft at d were an HR of 1.10 (95% CI 0.71–1.70).

Conclusions

PTX was associated with improved survival in patients on maintenance dialysis but not in patients with renal allograft.

Keywords: dialysis, epidemiology, hyperparathyroidism, kidney transplantation, PTH, survival analysis

INTRODUCTION

Secondary hyperparathyroidism (sHPT) is common among patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [1], and it often persists after successful renal transplantation [2]. sHPT is associated with high-turnover bone disease [3], interstitial and vascular calcifications [4] and cardiovascular morbidity [5] and mortality [6]. It can contribute to calcification of the allograft and thereby worsen the transplant function [7]. Despite improvements in medical therapy, such as the introduction of calcimimetics, surgical parathyroidectomy (PTX) is often necessary [8].

PTX has been shown to reduce cardiovascular calcification [9] and to have a positive impact on blood pressure [10], anaemia and serum lipids [11]. Improvements in bone density [12] and bone pain [13] have also been reported, although PTX can be associated with significant morbidity [14] and even mortality [15]. PTX has been shown to improve long-term survival in dialysis patients in some [16–21], but not all [22, 23], previous studies. However, none of these studies included transplanted patients. Furthermore, three of them were performed before the introduction of calcimimetics [17, 18, 22] and five of them were limited by small numbers of PTX patients [16, 19, 20, 22, 23]. A randomized trial is unlikely to be performed to compare PTX with medical treatment alone, due to the low rate of PTX [18, 24–27]. Hence, there is a rationale for observational cohort studies on the outcome of PTX for patients with sHPT.

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of PTX on mortality in patients receiving renal replacement therapy (RRT), comprising both transplanted patients and dialysis patients, in a nationwide, population-based cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study cohort

This study was performed and reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement [28]. It is a matched index-referent study within a cohort consisting of all patients in the Swedish Renal Registry (SRR) between 1 January 1991 and 31 December 2009. Registration in the SRR is mandatory for all patients at the start of RRT. All Swedish dialysis and renal transplantation units are affiliated with the SRR, which has a coverage of almost 100% [29].

Ascertaining PTX, comorbidity and death

The date of PTX, defined as total or subtotal PTX, and diagnosis at hospital discharge were retrieved by linking the SRR to the Swedish Inpatient Registry. The dates for PTX in the Swedish Inpatient Registry were compared with information from the Scandinavian Quality Registry for Thyroid, Parathyroid and Adrenal Surgery, which has registered thyroid and parathyroid operations since 2004. Approximately 90% of the units performing this surgery in Sweden report to this registry [30]. Discharge diagnoses in International Classification of Diseases, 7th-9th revision codes were translated into ICD10 by using conversion tables from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare [31]. Discharge diagnoses were then used to construct comorbidity groups according to Charlson et al. [32], with the help of an algorithm described by Quan et al. [33]. The Swedish Inpatient Registry has had a national coverage of nearly 100% since 1987 and has high validity [34, 35]. The physician in charge of the patient enters the date and cause of death into the SRR.

Matching

The patients who had undergone PTX after being entered into the SRR were divided into two patient groups: those on maintenance dialysis treatment and those with a functioning renal allograft at the time of PTX. The patients in the two groups were randomly matched with between one and five patients who had not undergone PTX. The matching criteria were birth year in 10-year categories, sex and cause of ESRD in categories (autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, glomerulonephritis, nephrosclerosis, pyelonephritis and other/unknown). In order to calculate survival time, index and referent patients were assigned the calendar date of PTX of the index patient, hereafter referred to as d. The matched reference patient was required to be alive on this date and to have the same form of RRT at d, i.e. dialysis or a functioning renal transplant.

Statistical analysis

Means and SDs were calculated for continuous variables and numbers and column percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Patients were censored at death or at end of follow-up, 31 December 2009. Crude and adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to compare hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for death between PTX and non-PTX patients in the matched sets, using as the timescale time from d to censoring.

Cox regressions were performed for the PTX and matched non-PTX patients among patients on dialysis and patients with a functioning allograft, respectively. In the adjusted analysis of patients on dialysis, total time in RRT before d and Charlson comorbidity score at d were entered as continuous covariates. Renal transplant during the study period (yes versus no), treatment region (South, South-east, West, Uppsala/Örebro, North and abroad) versus Stockholm region and the first RRT modality, peritoneal dialysis or renal transplantation compared with haemodialysis after entry in the SRR were entered as categorical covariates.

In the adjusted analysis of patients with functioning renal allograft at d, total time in RRT before d and Charlson comorbidity score at d were entered as continuous covariates. Treatment region (South, South-east, West, Uppsala/Örebro, North and abroad) versus Stockholm region was entered as a categorical covariate.

Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier survival estimate curves were calculated from d, censored for end of follow-up at 31 December 2009, for PTX and non-PTX patients with dialysis and renal transplant at d, respectively.

We analysed survival after PTX in unadjusted and adjusted models for dialysis patients starting RRT before 1 January 2004 and after 31 December 2003 separately, i.e. before and after the year of introduction of calcimimetics. Cox regressions were performed separately for men and women. Using analysis of variance, we tested the interaction between renal transplantation and PTX with survival time as the dependent variable.

Results with a P-value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were made using STATA software version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Patients and data

There were 20 056 patients in the SRR during the study period. Of these, 45 patients were excluded for the following reasons: errors in reporting of patient information (n = 18) and censoring on the same day as initiation of RRT (n = 27). From these 20 011 patients, 130 patients were excluded from matching because of PTX occurring before registration in the SRR.

Altogether, 590 patients had undergone PTX after being enrolled in the SRR. Eleven PTX patients could not be matched according to our matching criteria and were excluded. Of the remaining 579 patients, 423 were on dialysis and 156 had a functioning renal allograft at the time of PTX. The 423 dialysis patients were matched with 1234 referent patients (1 matching referent in 7 PTX patients, 2 in 53, 3 in 347, 4 in 2 and 5 in 14), in total 1657 patients on dialysis at d. The 156 patients with a functioning renal allograft were matched with 736 reference patients (1 matching referent in 1 PTX patient, 2 in 13, 4 in 2 and 5 in 140 patients), in total 892 patients with a functioning renal transplant at d.

All incident PTX patients in the Scandinavian Quality Registry for Thyroid, Parathyroid and Adrenal Surgery were identified in the Swedish Inpatient Registry, where admission date was considered as being the operation date. The operation dates for 217 patients who had undergone the operation after 2003 were compared between the two registries mentioned above and found congruent in 149 patients. In 64 patients the date differed by 1 day and in 4 patients the date differed up to 12 days. We used the admission date in the Inpatient Registry as the PTX date for all patients.

Demographics and patient characteristics

Demographics and patient characteristics of the cohort, PTX patients and matched non-PTX patients on dialysis and with a functioning renal allograft are shown in Tables 1–3. The cohort population was older than the matched sets, both at initiation of RRT and at time of death. Patients in the whole cohort were also more often male, were more likely to have diabetes mellitus as the cause of ESRD and had undergone fewer renal transplantations.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, whole cohort including the 2549 study patients

| Factor | All patients (N = 20 011) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Start of RRT | 62.8 (16.5) |

| Deatha | 71.3 (11.7) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 7131 (35.6) |

| Male | 12 880 (64.4) |

| Cause of ESRD | |

| ADPKD | 1572 (7.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4843 (24.2) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 3182 (15.9) |

| Nephrosclerosis | 3651 (18.2) |

| Pyelonephritis | 1009 (5.0) |

| Other and unknown | 5754 (28.8) |

| Number of transplants | |

| 0 | 14 951 (74.7) |

| 1 | 4686 (23.5) |

| 2 | 347 (1.7) |

| 3 | 23 (0.1) |

| 4 | 4 (<0.1) |

| Alive at end of follow-upb | 7045 (35.2) |

| Follow-up time (months) | 48.7 (51.5) |

Italicized numbers indicate mean (SD); number (%) in plain text.

RRT, renal replacement therapy; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

aIn 12 966 patients, death occurred before the end of follow-up, 31 December 2009.

b31 December 2009.

Table 3.

Patient characteristics of the individually matched PTX and non-PTX patients with a functioning renal allograft at da

| PTX patients (N = 156) | Matched reference patients (N = 892) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Start of RRT | 46.0 (12.1) | 45.0 (12.3) |

| PTX (d) | 51.9 (12.3) | 50.5 (1) |

| Deathb | 62.3 (14.3) | 59.7 (10.4) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 78 (50.0) | 359 (48.8) |

| Male | 78 (50.0) | 377 (51.2) |

| Time on RRT at PTX (d) (years) | 5.1 (3.1) | 5.7 (3.7) |

| Cause of ESRD | ||

| ADPKD | 24 (15.4) | 120 (16.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 25 (16.0) | 125 (17.0) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 57 (36.5) | 279 (37.9) |

| Nephrosclerosis | 11 (7.1) | 43 (5.8) |

| Pyelonephritis | 11 (7.1) | 30 (4.1) |

| Other and unknown | 28 (18.0) | 139 (18.9) |

| Number of transplants | ||

| 1 | 131 (84.0) | 674 (91.6) |

| 2 | 22 (14.1) | 57 (7.7) |

| 3 | 3 (1.9) | 4 (0.5) |

| 4 | 1 (0.1) | |

| Charlson comorbidity score at PTX (d) | 0.9 (1.3) | 1.1 (1.6) |

| Hospital readmission <30 days from PTX | 36 (23.1) | |

| Alive at end of follow-upc | 125 (80.1) | 597 (81.1) |

| Follow-up time (months from d) | 76.9 (51.1) | 73.5 (49.9) |

Italicized numbers indicate mean (SD); number (%) in plain text.

RRT, renal replacement therapy; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

aThe date of PTX or corresponding time for non-PTX patients.

bIn 31/139 patients, death occurred before end of follow-up, 31 December 2009.

c31 December 2009.

The patients on dialysis at d were older at the start of RRT, had spent less time on RRT at d and had a higher comorbidity score than the patients with a renal allograft at d. The hospital readmission rate within 30 days from PTX was higher for dialysis patients: 30.0% compared with 23.1% for the patients with a renal allograft. Indexes and referents were similar, both regarding matched and unmatched variables (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics of the individually matched PTX and non-PTX patients on dialysis at da

| PTX patients (N = 423) | Matched reference patients (N = 1234) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Start of RRT | 51.6 (14.7) | 53.8 (14.4) |

| PTX (d) | 55.2 (13.9) | 56.0 (14.2) |

| Deathb | 64.6 (12.3) | 64.8 (11.9) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 219 (51.8) | 616 (49.9) |

| Male | 204 (48.2) | 618 (50.1) |

| Time on RRT at PTX (d) (years) | 3.6 (3.2) | 2.2 (2.4) |

| Cause of ESRD | ||

| ADPKD | 68 (14.2) | 173 (14.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 64 (15.1) | 192 (15.6) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 122 (28.8) | 363 (29.4) |

| Nephrosclerosis | 46 (10.9) | 132 (10.7) |

| Pyelonephritis | 37 (8.9) | 88 (7.1) |

| Other and unknown | 94 (22.2) | 286 (23.1) |

| First RRT modality | ||

| Haemodialysis | 243 (57.4) | 800 (64.8) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 172 (40.7) | 424 (34.4) |

| Renal transplant | 8 (1.9) | 10 (0.8) |

| Number of transplants | ||

| 0 | 214 (50.6) | 752 (60.9) |

| 1 | 167 (39.5) | 422 (34.2) |

| 2 | 36 (8.5) | 57 (4.6) |

| 3 | 5 (1.2) | 3 (0.2) |

| 4 | 1 (0.2) | |

| Charlson comorbidity score at PTX (d) | 1.4 (1.7) | 1.6 (1.8) |

| Hospital readmission <30 days from PTX | 127 (30.0) | |

| Alive at end of follow-upc | 233 (55.1) | 604 (49.0) |

| Follow-up time (months from d) | 61.3 (45.7) | 54.6 (43.7) |

Italicized numbers indicate mean (SD); number (%) in plain text.

RRT, renal replacement therapy; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

aThe date of PTX or corresponding time for non-PTX patients.

bIn 190/630 patients, death occurred before end of follow-up, 31 December 2009.

c31 December 2009.

Risk of death

Thirty-day mortality was observed in 5 of 590 PTX patients, (0.8%). The reported causes of death in these patients were myocardial infarction in two patients, infection in two patients and cerebral haemorrhage in one patient. Among the patients on dialysis at d (PTX and non-PTX patients), one died 77 days after the start of RRT and one after 59 days. Among all the patients with a renal allograft at d, no patient died within the first 90 days after the start of RRT. No patient in the matched sets was lost to follow-up.

PTX was associated with better survival, both in crude and adjusted analyses in patients on dialysis at d. The unadjusted HR for death was 0.74 (95% CI 0.62–0.90) for PTX patients compared with non-PTX patients (see Table 4). This association remained significant after adjustment for total time on RRT before d, functioning graft during the study period, region (Stockholm, South, South-east, West, Uppsala/Örebro, North and abroad), first modality of RRT (haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis or transplantation) and comorbidity at d. The adjusted HR for death after PTX was 0.80 (95% CI 0.65–0.99). Greatly improved survival was related to renal allograft during the study period. Time on RRT before PTX and higher Charlson comorbidity score were associated with lower survival. These results were similar in men and women.

Table 4.

Relative risk of death for PTX patients compared with references, on dialysis at da (n = 423/1234) [Cox proportional hazards regression and HR (95% CI)]

| Factor | Unadjusted | Adjusted |

|---|---|---|

| PTX | 0.74 (0.62–0.90) | 0.80 (0.65–0.99) |

| Time on RRT before PTX | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) |

| Functioning graft at any time (yes/no) | 0.21 (0.16–0.27) | 0.20 (0.15–0.27) |

| Region compared with Stockholm region | ||

| South | 0.87 (0.65–1.17) | 0.93 (0.67–1.29) |

| South-east | 1.13 (0.82–1.56) | 1.18 (0.84–1.68) |

| West | 1.11 (0.82–1.48) | 1.19 (0.87–1.65) |

| Uppsala/Örebro | 1.20 (0.90–1.59) | 1.39 (1.02–1.90) |

| North | 0.94 (0.66–1.36) | 1.01 (0.68–1.50) |

| Abroad | 0.10 (0.01–0.79) | 0.10 (0.01–0.79) |

| RRT modality, compared with haemodialysisb | ||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 0.91 (0.75–1.11) | 1.02 (0.83–1.26) |

| Renal transplant | 0.91 (0.27–3.05) | 2.93 (0.83–10.42) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 1.28 (1.20–1.35) | 1.21 (1.14–1.29) |

The adjusted hazard ratios were adjusted for all the variables in the table.

RRT, renal replacement therapy.

aThe date of PTX or corresponding date for non-PTX patients.

bFirst therapy after entry in the SRR.

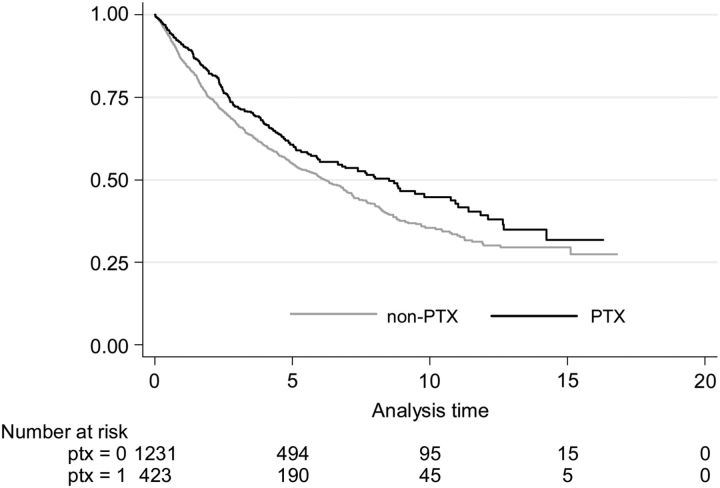

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve also indicated a better survival for PTX patients on dialysis than non-PTX patients during the entire study period (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1:

Kaplan–Meier survival estimate for PTX and non-PTX patients on dialysis at d, where d is the date of PTX or corresponding date for non-PTX patients.

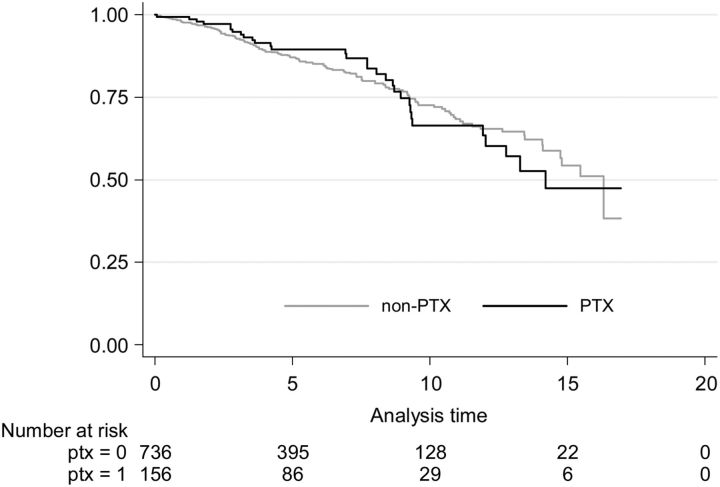

There was no difference in survival between PTX and non-PTX patients with a functioning renal allograft at d, neither in crude nor adjusted analysis (Table 5 and Figure 2). Time spent on RRT before PTX in the crude analysis was associated with lower survival for transplanted patients, as was a higher Charlson comorbidity score in both the crude and adjusted analyses.

Table 5.

Relative risk of death for PTX patients compared with references, with a functioning renal allograft at or da (n = 156/736) [Cox proportional hazards regression and HR (95% CI)]

| Factor | Unadjusted | Adjusted |

|---|---|---|

| PTX | 1.01 (0.66–1.53) | 1.10 (0.71–1.70) |

| Time on RRT before PTX | 1.09 (1.00–1.18) | 1.07 (0.98–1.169 |

| Region compared with Stockholm region | ||

| South | 0.98 (0.57–1.70) | 1.06 (0.60–1.86) |

| South-east | 1.31 (0.69–2.50) | 1.47 (0.76–2.86) |

| West | 0.55 (0.28–1.08) | 0.63 (0.31–1.28) |

| Uppsala/Örebro | 0.72 (0.42–1.25) | 0.75 (0.43–1.31) |

| North | 0.67 (0.32–1.42) | 0.66 (0.31–1.41) |

| Abroad | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Charlson comorbidity score | 1.38 (1.18–1.61) | 1.21 (1.14–1.29) |

The adjusted hazard ratios were adjusted for all the variables in the table.

RRT, renal replacement therapy.

aThe date of PTX or corresponding date for non-PTX patients.

FIGURE 2:

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates for PTX and non-PTX patients with functioning renal allograft at d, where d is the date of PTX or corresponding date for non-PTX patients.

Stratified Cox regressions were performed according to time of PTX (d), i.e. before and after the introduction of calcimimetics in 2004.

In patients on dialysis at d until and including the year 2003 (6078 person-years in total), the unadjusted HR for death after PTX was 0.73 (95% CI 0.59–0.90). In patients on dialysis at d from 2004 and onwards (1692 person-years in total), the survival estimate was similar but no longer significant, [HR 0.81 (95% CI 0.55–1.21)].

The interaction between PTX and the renal transplant variable was significant (P < 0.05), which indicates that survival time varies for the different levels of the independent variables (PTX/non-PTX and with renal transplant at d/without a renal transplant at d). The mean survival time for patients who underwent PTX and were on dialysis at d was 61.3 months, compared with the patients who underwent PTX and received an allograft, who survived 76.9 months. Patients who did not undergo PTX and were on dialysis had a mean survival time of 37.0 months, compared with 76.8 months for the non-PTX patients with an allograft.

DISCUSSION

Patients on RRT who underwent PTX during dialysis treatment had a 26% lower risk of death compared with those who did not, after matching for age, sex and underlying renal condition. PTX was responsible for a 20% reduced risk of death in patients on dialysis even after adjustment for total time on RRT before d, renal allograft at any time during the study period, region, first RRT modality and comorbidity score. The association between PTX and survival was similar in men and women. Similar results were seen after stratifying the analysis to the time before and after the introduction of calcimimetics. Interestingly, PTX did not have a positive effect on survival in patients with a functioning renal allograft at d.

A positive association in patients on dialysis was observed between survival and renal allograft throughout the study period. An inverse association between time spent receiving RRT before d and comorbidities according to the Charlson index and survival for dialysis patients was also seen. In patients with a functioning renal allograft at d, time spent on RRT before d and comorbidity at d were associated with impaired survival.

The results for the dialysis patients are in line with most, but not all, previous studies. In a large population-based study from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) between 1988 and 1998 (4558 PTX patients), Kestenbaum et al. [17] found a 13% lower risk of death after 90 days following PTX compared with matched non-PTX patients. Similarly, in a somewhat later USRDS study of haemodialysis patients, Foley et al. [18] reported a lower relative risk of death after PTX compared with non-PTX controls. A recently published study by Komaba et al. [21] agrees with these results, in a nationwide population-based cohort of Japanese patients on haemodialysis. The risk of 1-year post-operative all-cause mortality was found to be 34% lower in patients who underwent PTX compared with their matched reference patients. Three smaller, retrospective studies on dialysis patients also reported improved survival after PTX [16, 19, 20].

In contrast, two other studies found no consistent evidence of improved survival after PTX [22, 23]. In one of these comprising 50 patients, controls were selected on the basis of having refused PTX [23], thus differing from our matched control patients. Trombetti et al. [22] found an increased survival after PTX, which disappeared after adjusting for comorbidities.

The reasons for the improved survival for patients undergoing PTX in this study are most likely multifactorial. High (and very low) levels of PTH have been associated with higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [36], PTH may have stimulating effects on the development of atherosclerosis [37]. sHPT affects plasma calcium and phosphate levels. Both high calcium and phosphate are implicated in contributing to an increased cardiovascular calcification in patients on RRT and an increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [38, 39]. Moreover, sHPT and hyperphosphatemia have detrimental effects on bone structure and have been associated with fracture-related death [5, 40, 41]. PTX improves calcium and phosphate balance [42]. These various effects most likely contribute to the decrease in morbidity and mortality among operated patients [10, 11, 42, 43].

There is a profound difference between the sHPT in patients with a functioning renal allograft and the sHPT in dialysis patients. Renal transplantation corrects disturbances in mineral metabolism, and high phosphate levels are much less a problem in these patients. Some patients, though, can have persisting hypercalcaemia and hyperparathyroidism that needs to be treated with PTX. The lack of a positive effect of PTX on survival in the transplanted patients is somewhat enigmatic. However, especially during the first year post-transplantation, there are other competing risk factors. The span in renal function can be wide and may fluctuate due to viral infections or recurrence of the original kidney disease. Moreover, the fact that renal control of mineral metabolism is very much improved may have an important impact on mortality.

In a recent USRDS study by Ishani et al. [41], comprising 4435 haemodialysis patients who had undergone PTX between 2007 and 2009, severe adverse clinical outcomes after PTX were reported. They found a 2% 30-day mortality and a 24% re-hospitalization rate within 30 days after discharge. The study also showed more frequent hospitalizations and emergency room visits during the year following PTX compared with the preceding year. In our study, the 30-day mortality was 0.8%. This discrepancy may be related to differences in patient characteristics in our cohorts. For example, nearly 23% of the patients in the USRDS study had diabetes as the primary cause of ESRD, compared with 15% of the dialysis patients in our study. Furthermore, 66% of the patients in the US study had spent >5 years on dialysis before PTX, compared with 26% of the patients in the present study. There are also differences in comorbidity, with a markedly lower prevalence of congestive heart failure (13 versus 44%) and peripheral vascular disease (6 versus 31%) in our cohort. On the other hand, the dialysis patients in our study had a 30% readmission rate to hospital within 30 days of PTX, which is higher than reported by Ishani et al. (24%). The initial time in hospital for the actual PTX procedure is fairly short in Sweden, in our data 6.6 days for patients on dialysis and 5.2 days for patients with renal allograft, which might well influence the re-admission rate.

We chose not to adjust for surgical technique in our study based on the lack of evidence of effect on outcome after subtotal or total PTX. In this study, 58% of the patients had a total and 42% had a subtotal PTX. Kuo et al. [44] performed a retrospective study of outcome after PTX between 2008 and 2011, focusing on 30-day mortality in dialysis patients undergoing either total or subtotal PTX. They found no differences in 30-day mortality in either group, although subtotal PTX comprised the majority of the operations performed, in contrast to our study.

The rate of PTX has varied greatly in recent decades, and in the present millennium, medical alternatives to PTX have been developed that have lowered the operation rate [18, 24]. The effects of calcimimetics, calcium-free phosphate binders and new vitamin D-analogues on survival are as yet unclear. In light of the introduction of these new and effective alternative therapies for sPTH, survival analyses performed before and after 2004, as in our study, are interesting. Survival before and after was similar in our study, and the loss of significance for the HR for PTX performed from 2004 onwards could be an effect of less power due to fewer person-years studied in the latter period.

There are certain limitations in this study. Despite matching and adjustment for several confounding factors, residual confounding cannot be excluded. It would have been valuable to have information on medical treatment, laboratory analyses of PTH, calcium and phosphate as well as certain demographic and social factors. Patients with a renal transplant are heterogeneous regarding renal function, BK virus and cytomegalovirus infections, development of new-onset diabetes and relapse of underlying kidney disease. We did not have the data to adjust for these differences in this study.

A strength of the present study is the fact that the national registries contain information on almost all patients on RRT in Sweden, making this the first truly population-based European study performed. Thus, our findings ought to have high external validity and decreased bias depending on regional differences. Furthermore, the long-term follow-up time includes different eras of PTX incidence and medical treatments.

In conclusion, PTX was associated with improved survival in patients on maintenance dialysis. However, there was no survival advantage after PTX in patients with a functioning renal allograft.

FUNDING

Received donations from Skane University Hospital, The Anna Lisa and Sven-Erik Lundgren Foundation for Medical Research and Southern Health Care Region Grants.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared. The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the participating centres of the Swedish Renal Registry and Scandinavian Quality Registry for Thyroid, Parathyroid and Adrenal Surgery, who were indispensable in collecting and reporting the data required for the present study. We would like to especially thank professor Jonas Ranstam for invaluable advice regarding statistical study design.

REFERENCES

- 1.Llach F, Velasquez Forero F. Secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic renal failure: pathogenic and clinical aspects. Am J Kidney Dis 2001; 38 (5 Suppl 5): S20–S33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isaksson E, Sterner G. Early development of secondary hyperparathyroidism following renal transplantation. Nephron Clin Pract 2012; 121: c68–c72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham J, Sprague SM, Cannata-Andia J et al. Osteoporosis in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43: 566–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres PA, De Broe M. Calcium-sensing receptor, calcimimetics, and cardiovascular calcifications in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2012; 82: 19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM et al. Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 2208–2218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganesh SK, Stack AG, Levin NW et al. Association of elevated serum PO(4), Ca×PO(4) product, and parathyroid hormone with cardiac mortality risk in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12: 2131–2138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gwinner W, Suppa S, Mengel M et al. Early calcification of renal allografts detected by protocol biopsies: causes and clinical implications. Am J Transplant 2005; 5: 1934–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Kidney Foundation. K-DOQI: clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab 2007; 5: 53–67 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleyer AJ, Burkart J, Piazza M et al. Changes in cardiovascular calcification after parathyroidectomy in patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 46: 464–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldsmith DJ, Covic AA, Venning MC et al. Blood pressure reduction after parathyroidectomy for secondary hyperparathyroidism: further evidence implicating calcium homeostasis in blood pressure regulation. Am J Kidney Dis 1996; 27: 819–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evenepoel P, Claes K, Kuypers D et al. Impact of parathyroidectomy on renal graft function, blood pressure and serum lipids in kidney transplant recipients: a single centre study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005; 20: 1714–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein MS, Packham DK, Wark JD et al. Response to parathyroidectomy at the axial and appendicular skeleton in renal patients. Clin Nephrol 1999; 52: 172–178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rayes N, Seehofer D, Schindler R et al. Long-term results of subtotal vs total parathyroidectomy without autotransplantation in kidney transplant recipients. Arch Surg 2008; 143: 756–761; discussion 61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jofre R, Lopez Gomez JM, Menarguez J et al. Parathyroidectomy: whom and when? Kidney Int Suppl 2003; 85: S97–S100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta PK, Smith RB, Gupta H et al. Outcomes after thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy. Head Neck 2012; 34: 477–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma J, Raggi P, Kutner N et al. Improved long-term survival of dialysis patients after near-total parathyroidectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2012; 214: 400–407; discussion 7–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kestenbaum B, Andress DL, Schwartz SM et al. Survival following parathyroidectomy among United States dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2004; 66: 2010–2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foley RN, Li S, Liu J et al. The fall and rise of parathyroidectomy in U.S. hemodialysis patients, 1992 to 2002. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16: 210–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwamoto N, Sato N, Nishida M et al. Total parathyroidectomy improves survival of hemodialysis patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. J Nephrol 2012; 25: 755–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldenstein PT, Elias RM, Pires de Freitas do Carmo L et al. Parathyroidectomy improves survival in patients with severe hyperparathyroidism: a comparative study. PLoS One 2013; 8: e68870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komaba H, Taniguchi M, Wada A et al. Parathyroidectomy and survival among Japanese hemodialysis patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int 2015; 88: 350–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trombetti A, Stoermann C, Robert JH et al. Survival after parathyroidectomy in patients with end-stage renal disease and severe hyperparathyroidism. World J Surg 2007; 31: 1014–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conzo G, Perna AF, Savica V et al. Impact of parathyroidectomy on cardiovascular outcomes and survival in chronic hemodialysis patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. A retrospective study of 50 cases prior to the calcimimetics era. BMC Surg 2013; 13 (Suppl 2): S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akaberi S, Clyne N, Sterner G et al. Temporal trends and risk factors for parathyroidectomy in the Swedish dialysis and transplant population – a nationwide, population-based study 1991–2009. BMC Nephrol 2014; 15: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li S, Chen YW, Peng Y et al. Trends in parathyroidectomy rates in US hemodialysis patients from 1992 to 2007. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 57: 602–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kestenbaum B, Seliger SL, Gillen DL et al. Parathyroidectomy rates among United States dialysis patients: 1990–1999. Kidney Int 2004; 65: 282–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malberti F, Marcelli D, Conte F et al. Parathyroidectomy in patients on renal replacement therapy: an epidemiologic study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12: 1242–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.STROBE statement. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology. http://www.strobe-statement.org/ (11 August 2015, date last accessed)

- 29.Schon S, Ekberg H, Wikstrom B et al. Renal replacement therapy in Sweden. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2004; 38: 332–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scandinavian Quality Register for Thyroid and Parathyroid Surgery. https://www.thyroid-parathyroidsurgery.com/ (2 January 2013, date last accessed) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.National Board of Health and Welfare. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/klassificeringochkoder/laddaner/Sidor/konvtabeller.aspx (24 February 2015, date last accessed)

- 32.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40: 373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005; 43: 1130–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nilsson AC, Spetz CL, Carsjo K et al. [Reliability of the hospital registry. The diagnostic data are better than their reputation]. Lakartidningen 1994; 91: 598, 603–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tentori F, Wang M, Bieber BA et al. Recent changes in therapeutic approaches and association with outcomes among patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism on chronic hemodialysis: the DOPPS study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10: 98–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rashid G, Bernheim J, Green J et al. Parathyroid hormone stimulates the endothelial nitric oxide synthase through protein kinase A and C pathways. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007; 22: 2831–2837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B et al. Arterial calcifications, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 2001; 38: 938–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.London GM. Arterial calcification: cardiovascular function and clinical outcome. Nefrologia 2011; 31: 644–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alem AM, Sherrard DJ, Gillen DL et al. Increased risk of hip fracture among patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 2000; 58: 396–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishani A, Liu J, Wetmore JB et al. Clinical outcomes after parathyroidectomy in a nationwide cohort of patients on hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10: 90–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puccini M, Carpi A, Cupisti A et al. Total parathyroidectomy without autotransplantation for the treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism associated with chronic kidney disease: clinical and laboratory long-term follow-up. Biomed Pharmacother 2010; 64: 359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakman G, Parsak CK, Balal M et al. Outcomes of total parathyroidectomy with autotransplantation versus subtotal parathyroidectomy with routine addition of thymectomy to both groups: single center experience of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Balkan Med J 2014; 31: 77–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuo LE, Wachtel H, Karakousis G et al. Parathyroidectomy in dialysis patients. J Surg Res 2014; 190: 554–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]