Abstract

Human exposures to arsenic (As) through different pathways (dietary and non-dietary) are considered to be one of the primary worldwide environmental health risks to humans. This study was conducted to investigate the presence of As in soil and vegetable samples collected from agricultural lands located in selected southern districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) Province, Pakistan. We examined the concentrations of total arsenic (TAs), organic species of As such as monomethylarsonic acid (MMA) and dimethylarsonic acid (DMA), and inorganic species including arsenite (AsIII) and arsenate (AsV) in both soil and vegetable. The data were used to determine several parameters to evaluate human health risk, including bioconcentration factor (BCF) from soil to plant, average daily intake (ADI), health risk index (HRI), incremental lifetime cancer risk (ILTCR), and hazard quotient (HQ). The total As concentration in soil samples of the five districts ranged from 3.0-3.9 mg kg−1, exhibiting minimal variations from site to site. The mean As concentration in edible portions of vegetable samples ranged from 0.03-1.38 mg kg−1. It was observed that As concentrations in 75% of the vegetable samples exceeded the safe maximum allowable limit (0.1 mg kg−1) set by WHO/FAO. The highest value of ADI for As was measured for M. charantia, while the lowest was for A. chinense. The results of this study revealed minimal health risk (HI <1) associated with consumption of vegetables for the local inhabitants. The ILTCR values for inorganic As indicated a minimal potential cancer risk through ingestion of vegetables. In addition, the HQ values for total As were <1, indicating minimal non-cancer risk.

Keywords: Arsenic, vegetable, bioaccumulation, daily ingestion, cancer risk

1. Introduction

The contamination of food crops by toxic elements is a universal health concern (e.g., Ng et al., 2003; Waqas et al., 2014). Arsenic (As) is considered to be the most widely distributed contaminant currently in the food chain (Joseph et al., 2015a, 2015b; Llobet et al., 2003). As is released from both natural sources (parent rocks) and also from various anthropogenic activities such as agricultural practices, irrigation with As-contaminated water (Waqas et al., 2015), the improper applications of arsenical fertilizers, insecticides, herbicides, use of poultry litter with As-based intestinal palliatives (Jia et al., 2012; Oti, 2015; Zhu et al., 2008), mining activities, and petroleum refineries (Martínez-Sánchez et al., 2011; Khan et al., 2014; Kabata-Pendias, 2011). Soil is a major sink of As, which can lead to contamination of vegetables because of its high mobility and uptake rate (Sridhar et al., 2011). The bioavailability of As and its subsequent bioaccumulation in vegetables (tomato, cucumber, cauliflower, pea, lettuce, spinach, cabbage, onion, radish, turnip, carrot, potato, etc) depend on soil texture, pH, organic matter content and composition, redox condition, water regime, mineral composition, and microbial activity (e.g., Bergqvist et al., 2014; Khan et al., 2015a; Smith et al., 2009).

As is listed as a class one carcinogen (NRC, 2001; IARC, 2004), and is considered to be one of the most important toxicants of human health concern because of its ongoing potential threat to the health of hundreds of millions of individuals worldwide (Baig et al., 2009; Christen, 2001; Zavala and John, 2008). There is no evidence that As is essential for human health and its exposure has been linked to severe health complications such as hyperkeratosis, gangrene, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, melanosis, keratosis, bladder, and internal cancers, and also its carcinogenic consequences on skin and lungs (Fatmi et al., 2009; IARC, 2004; Ramadan and Al-Ashkar, 2007).

Previous studies have revealed that human exposure to As contaminated water and soil is of great concern, while food ingestion is one of the chief pathways of human exposure to toxic metals (Dummer et al., 2014; Joseph et al., 2015a; Khan et al., 2015b). Consequently, it is of practical significance to assess the extent of As accumulation from soil into plants. This research area has gained increasing attention throughout the world (e.g., Chang et al., 2014). Food crops such as vegetables and cereals are a potential entry source of As into the food chain and can reflect the levels of As that exist in the soil in which they are cultivated (Arain et al., 2009; Joseph et al., 2015b; Rahman et al., 2008; Ramirez-Andreotta et al., 2013a). Millions of individuals in south and south-east Asia have been suffering with As poisoning from exposure to As-contaminated food-crops from the last several years (Jia et al., 2012; Neumann et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2008).

Numerous studies have been conducted in order to assess the amount and toxicity of chemical forms of As such as organic species (monomethylarsonic acid (MMA), dimethylarsonic acid (DMA)) and inorganic species (arsenite (AsIII), arsenate (AsV)) present in soil and food plants (Ruiz-Chancho et al., 2007). Inorganic As (iAs) is considered to be more toxic and mobile than organic As (Egbenda et al., 2015; Van-Herreweghe et al., 2003).

The speciation of As in soil depends on numerous factors including pH, soil organic carbon (SOC), electron donor/acceptor availability, oxidation potential, and bacterial community structure and function. AsIII is the dominant species in reducing environments (~0.0-0.8 VpE and pH 2-10), while AsV is more prevalent under aerobic conditions (Acosta et al., 2015; Álvarez-Ayuso et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2010). As methylation into MMA and DMA occurs in soil mediated by both bacteria and plants (Huang et al., 2012). The literature supports both the ability and inability of plants to methylate iAs inside the tissues (Lomax et al., 2012; Raab et al., 2007). However, As distribution and translocation (root to shoot) occur through both xylem and phloem depending on plant species (Bergqvist et al., 2014).

Previously, several studies have been carried out to investigate As accumulation in vegetables grown in various areas (Garcia et al., 2014; Kronbauer et al., 2013; Martinello et al., 2014; Oliveira et al., 2013; Oliveira et al., 2012; Ramirez-Andreotta et al., 2013a; Ribeiro et al., 2013a; Sanchís et al., 2015; Silva et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2012). However, this is the first study of its nature conducted in the southern section of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan to investigate total As (TAs) and its organic (MMA and DMA) and inorganic species (AsIII and AsV) in agricultural soil and vegetables. Furthermore, we evaluate the daily As intake and cancer risk posed by the consumption of vegetables by local inhabitants.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Site description

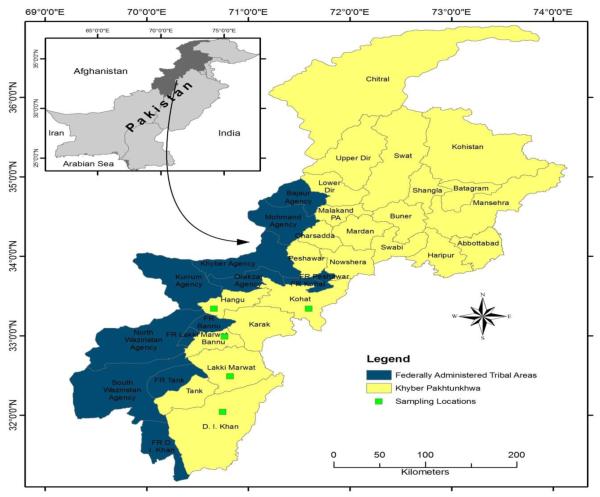

The study was conducted in the southern selected districts Hangu, Kohat, Bannu, Lakki Marwat and Dera Ismail Khan (DI Khan) of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan (Fig. 1). The study area encompassed 15,359 km2 (see Table S1) and has very fertile land, cultivated with a variety of crops and vegetables. In most of the areas, these food crops and vegetables are irrigated with water may contain high As concentration. Cucumber, bitter melon, ridge gourd, onion, garlic, mint, lady finger, squash-melon, lettuce, spinach, pea, pumpkin, cabbage, cauliflower, potato, bringal, turnips, carrot, radish, tomato, yam, perslane, oriental onion and coriander were selected as the most important food crops in this study (DCR, 1998; Waqas et al., 2014).The English and botanical names of selected food stuffs are provided in Table S2.

Fig. 1.

Location map of the study area showing sampling sites in the selected districts of KPK, Pakistan

2.2. Soil sampling and processing

The soil samples (n=175) were collected with a stainless steel auger from a depth of 0-20 cm. Multiple soil samples were collected from randomly selected locations for each site, followed by homogenization to form a composite sample (1 kg), using the quartile method(Wu et al., 2010). The soil samples were transported to the laboratory and then air dried. The dried samples were mechanically ground into fine powder and sieved to 2 mm, removing unwanted granulated substances and placed in clean plastic bags for further analyses.

Soil samples (1 g each) were subjected to acid digestion in Teflon vessels, following the protocol from US EPA SW-846, (1986) in the Arizona Laboratory for Emerging Contaminants (ALEC), University of Arizona, Tucson, USA. The samples were treated with 2.5 mL HNO3 (analytical grade) in microwave assisted reaction system (CEM MARs 6, NC, USA). After filtration through a membrane (0.22 μm), the filtrates were diluted up to 15 ml with milli-Q water and analyzed for TAs using inductively coupled plasmamass spectrometry (ICP MS) (Agilent 7700x, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). The As species such as AsIII, AsV, DMA, and MMA were determined using ICP-MS connected with high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC-ICP-MS) (Hamilton company, USA) and separated with HPLC system comprising a Agilent 1100 HPLC with Hamilton column (PRP-X100) and guard cartridge. The mobile phase was ammonium carbonate (pH 8.75) with 2% methanol in a gradient. The sum of AsIII and AsV was considered as the total iAs. To ensure accuracy and precision, soil standard certified reference material (CRMs, 2702) purchased from National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), USA and reagent blanks (without sample), were used with each batch of samples. The recovery rates were satisfactory and ranged from 92-113%.

2.3 Vegetable samplings and acid digestion

Vegetable samples (n=175) were collected from the same fields used for soil sampling. Further detail is given in SI (Table S2). The edible portions were separated, and all visible soil particles were removed using a soft bristled brush. The samples were then rinsed with tap water and finally washed with distilled water several times. The edible parts of vegetable were dried at 60±5°C for 72 h and then powdered using a Wiley Mill, passed through a 0.3 mm mesh, and stored in labeled coin envelopes at room temperature to avoid humidity, until used for acid digestion.

The powdered vegetable samples (500 mg) were placed in Teflon tubes and 2 ml of nitric acid (HNO3) was added and left to stand overnight. The next morning, after the addition of 2 ml hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), the samples were digested in a microwave assisted reaction system (CEM MARs 6, NC, USA). The temperature was raised to 55 °C held for 10 min, then to 75°C held for 10 min, and finally to 95 °C for 30 min, and then allowed to cool to room temperature (Marwa et al., 2012). The concentrations of TAs in solution were determined by ICP-MS (7700x, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA), while its species including AsIII, AsV, DMA and MMA were analyzed using HPLC-ICP-MS and separated with 1100HPLC system consists of an Hamilton column, USA (PRP-X100) and guard cartridge in the University of Arizona, USA. As done for the soil analysis, the sum of AsIII and AsV was considered as total iAs. To authenticate the quality control and analyses, certified reference material (NIST, 1515), apple leaves purchased from National Institute of Standards and Technology (USA), and acid blanks (sample free) were analyzed with each batch of samples. The recovery rates ranged from 97-107%.

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. Bioconcentration factor (BCF) from soil to plant

The bioconcentration factor (BCF) from soil to plant was computed, after investigating the concentration of total As in the soils and edible portion of the vegetables. BCF is the ratio of metal concentration in edible portion of vegetable dry weight (d.w) basis with the total metal concentration in the soils. The required BCF was determined by the following equation (e.g., Ramirez-Andreotta et al., 2013a):

| (1) |

Here Cvegetable and Csoil represent the element concentration in the extracted vegetable and soils (d.w), respectively.

2.4.2. Average daily As dose

The average daily intake (ADI) of As was calculated according to the following formula (2) as used by Khan et al. (2008, 2010) and Jan et al. (2010), while the total average daily intake was calculated (Eq. (3)), as the sum of the average individual intakes through different types of vegetables (leafy, gourd, Solanaceous and rooty),suggested by Uddh-Söderberg et al. (2015).

| (2) |

| (3) |

Here Cm, IRveg and Bw represent the As concentration in vegetable (mg kg−1), conversion factor, ingestion rate of vegetable, and average body weight, respectively. The values of conversion factor, the average daily ingestion rate of vegetables and the average body weight of adults and children are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Exposure factor values used for the calculation of EDD, ILTCR and HQ.

| Parameters | Symbol | Units | Value | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total As in vegetable | Cveg | mg kg−1 | Presented in Table 3 | This study |

| Inorganic As concentration in vegetable |

CiAs | mg kg−1 | Presented in Table 5 | This study |

| Ingestion rates of leafy, gourd, rooty and solanaceous vegetables |

IRveg | g day−1 | 100.4, 36.6, 21.0 and 28.1 per adult, while and 66.9, 25.0, 14.0 and 18.6 for childa |

Jiang et al. (2015) |

| Exposure frequency | EF | days year−1 | 365 | Li et al. (2011) |

| Exposure duration | ED | years | 70 | Li et al. (2011) |

| Conversion factor | CF | mg kg−1 | 0.085 | Rotten et al. (2005) |

| Body weight | BW | Kg | 70 for adult 24.5 for child |

Chen et al. (2014) |

| Life expectancy | LE | days | 25550 | Khan et al. (2014) |

| Arsenic reference dose | RfD | mg kg−1day−1 | 0.0003 | USEPA (2012b) |

| Arsenic oral cancer slope factor | CSF | Kg day mg−1 | 1.5 for adult, while 4.5for child |

USEPA (2012b) |

different vegetable ingestion rates for children were considered 1.5 factor lesser than adults, calculated from the amounts used in our previous studies (Khan et al., 2008)

2.4.3 Exposure and risk assessment

The average values of total As concentrations for vegetables (CTAs), were used to calculate the estimated daily dose (EDD), by the following formula (EA, 2010; Gerba, 2006; USEPA, 2011; USEPA, 1991b; Khan et al., 2014),

| (4) |

Here IRveg, CF, EF, ED, LE, and BW represent ingestion rate of vegetable, conversion factor, exposure frequency, exposure duration, life expectancy (25550 days), (Li et al., 2011; Zhuang et al., 2009) and average body weight, respectively. The values of these parameters were selected those used in previous literature (Table 1).

2.4.4 Hazard quotient (HQ)

Hazard quotient (non-carcinogenic effects) is the ratio of the EDD to the reference dose (RfD) and RfD value for TAs is 0.0003 mg kg−1 d−1(USEPA, 2012b). The hazard index (HI) was calculated as sum of average HQ values of different vegetables.

| (5) |

Here ADI, and RfD, represent the daily intake of As and reference dose, respectively. The RfD for As is 0.0003 mgkg−1day−1 (USEPA, 2012b). The exposed population is assumed with no potential risk when HQ< 1 (Khan et al., 2008; Muhammad et al., 2011).

2.4.5 Cancer risk assessment

The values of EDD were used to calculate Incremental lifetime cancer risk, (ILTCR) for the iAs, using the following equation (Khan et al., 2014; USEPA, 2010):

| (6) |

CiAsis the concentration of iAs in vegetables, while CSF is the cancer slope factor (Table 1).

Statistical analysis was done using Microsoft Excel (2010) computer package. The measurements were expressed in terms of mean and standard deviation. The location map of the study area was prepared, using Arc-Geographic Information System (Arc-GIS).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Total As and its species in soils

The concentrations of TAs in the soil samples collected from all the selected sites are summarized in Table 2. The TAs concentrations ranged from 3.0-3.9 mg kg−1 (on dry weight (d.w) basis), and exhibited very little variation among the selected sites of the study area. The trend of mean TAs concentration was in order of Lakki Marwat <Hangu <DI Khan <Kohat <Bannu. The TAs concentrations in soils of this study area were lower than those reported in previous studies (Ellice et al., 2001; Ramirez-Andreotta et al., 2013a) but partially consistent with the results obtained by Islam et al. (2012).

Table 2.

The concentrations (mg Kg−1) of TAs and As species in the soil samples (n=175) on d.w basis collected from the study area.

| Parameters | Statistics | Bannu (n=24) |

DI Khan (n=37) |

Kohat (n=47) |

Hangu (n=39) |

LakkiMarwat (n=28) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 0.89-5.60 | 0.95-6.64 | 1.22-7.10 | 3.81-5.21 | 1.43-4.76 | |

| TAs | Mean±STDa | 3.91±1.15 | 3.58±1.45 | 3.65±1.42 | 3.08±1.38 | 3.02±0.93 |

| Range | 0.70-1.35 | 0.61-1.65 | 0.51-5.99 | 1.0-1.51 | ND | |

| MMA | Mean±STD | 1.02±0.47 | 1.21±0.47 | 2.33±3.16 | (1.27±0.21) | ND |

| Range | NDb | 0.48-0.7 | 0.44-0.63 | ND | ND | |

| DMA | Mean±STD | ND | 0.62±0.12 | 0.54±0.09 | ND | ND |

| Range | ND | 0.49-0.63 | ND | ND | ND | |

| AsIII | Mean±STD | ND | 0.56±0.09 | ND | ND | ND |

| Range | 0.6-10.1 | 1.04-6.01 | 0.05-13.7 | 0.50-1.85 | 0.70-1.75 | |

| AsV | Mean±STD | 2.53±2.77 | 2.08±1.03 | 2.56±3.06 | 1.32±0.41 | 1.24±0.3 |

| Range | 0.6-10.1 | 1.53-6.64 | 0.05-13.7 | 0.50-1.85 | 0.70-1.75 | |

| iAsTotal | Mean±STD | 2.53±2.77 | 2.64±1.39 | 2.56±3.06 | 1.32±0.41 | 1.24±0.32 |

| Recovery (%) |

Range | 92-113% | 92-110% | 94-108% | 93-109% | 97-107% |

Standard deviation

not detected

The TAs concentrations observed in soils were higher than the results reported by Karim et al. (2008) in Feni District, Bangladesh. According to Farooqi et al. (2009), the average concentration of TAs in the soil was 10.2 mg/kg collected from most heavily polluted area of Punjab, Pakistan. Baig and Kazi (2012) observed TAs in range of 2.0-70 mg/kg in the soils collected from Khairpur Mir’s, Sindh, while its concentrations ranged from 8.7-46.2 mg/kg in the soil irrigated with the water of obtained from Manchar Lake in Sehwan Sindh, Pakistan (Arain et al., 2009). These high concentrations of TAs in soils were linked with mining, wastewater and As-contaminated water irrigation. No prior data exit for As and its speciation in the soil of Khyber Pakhtunwakh and only a few sites in Peshawar were analyzed for TAs and its concentrations were found below detection limit (Waseem et al., 2014).

In this study, As concentrations for all samples were below the safe maximum allowable limit (MAL: 30 mg kg−1) established by State Environmental Protection Administration (SEPA, 1995) for soils in China. The low levels of As present in the soil may be from geogenic origins and/or from application of fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides. The absence of elevated concentrations of TAs in soil could be linked with the lack of major mining activity and also with less/no wastewater irrigation in the study area.

The concentrations of As species (DMA, MMA, AsIII and AsV) and the sum of iAs in the soils of the study area are also presented in Table 2. In all soil samples, AsIII was not detected, except for samples from DI Khan, while AsV was observed in the range of 1.2-2.6 mg kg−1 throughout the study area. It was observed that the highest iAs concentration was found in the soil of DI Khan, while the lowest in the soil of Lakki Marwat. MMA was detected in all soil samples of the study area except in the soil of Lakki Marwat where it was below the detection limit (Table 2). The mean concentration of MMA ranged from 1.0-2.3 mg kg−1in all the tested soil samples. DMA was detected in the soils of DI Khan and Kohat, while it was below the limit of detection in the soils of Bannu, Hangu and Lakki Marwat. Moreover, the highest MMA concentration was found in the soils of Kohat, while the lowest concentration was observed in the soils of Bannu. Likewise, the highest concentration of DMA was detected in the soil samples of DI Khan and the lowest was in the soil of Kohat (Table 3). The speciation of As varies from upland to paddy land because of the presence of different controlling factors such as redox condition, oxidation potential and bacterial community structure (Álvarez-Ayuso et al., 2016; Meharg, 2004; Williams et al., 2007). In the study area, the soil basic characteristics including pH, EC, total N C and S, dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and texture were varied (Table S3), which can affect As speciation (Acosta et al., 2015;Álvarez-Ayuso et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2007).

Table 3.

The concentrations (mg kg−1) of As species in vegetables (n=175) on d.w basis collected from the study area

| Vegetables | TAs | DMA | MMA | AsIII | AsV | iAs(AsIII+AsV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. charantia (n=05) | 1.38 | BDL | 1.20 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.24 |

| L. acutangula (n=08) | 1.35 | BDL | 1.11 | BDL | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| S. lycopersicum (n=10) | 0.99 | BDL | 0.88 | BDL | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| A. malvaceae (n=13) | 1.35 | BDL | 0.57 | BDL | 1.35 | 1.35 |

| C. sativus (n=08) | 1.24 | BDL | 1.12 | BDL | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| S. melongena (n=7) | 0.85 | BDL | 0.75 | 1.00 | BDL | 1.00 |

| P. fistulosus (n=08) | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.46 | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| B. oleracea (n=07) | 0.10 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| B. hispada (n=07) | 0.59 | BDL | 0.67 | BDL | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| P. sativum (n=6) | 0.05 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| M. arvensis (n=05) | 0.20 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| L. sativa (n=04) | 0.19 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| B. vulgaris (n=17) | 1.27 | BDL | 1.20 | BDL | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| B. olemcea (n=05) | 0.98 | BDL | 0.70 | BDL | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| C. sativum (n=10) | 0.54 | BDL | 0.36 | BDL | 0.54 | 0.54 |

| A. chinense (n=07) | 0.03 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| P. oleracea (n=05) | 0.72 | BDL | 0.73 | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| A. cepa (n=05) | 0.24 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| A. sativum (n=12) | 0.06 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| R. sativus (n=08) | 0.12 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| B. rapa (n=07) | 0.10 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| D. carota (n=04) | 0.06 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| C. esculanta (n=03) | 0.06 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

| S. tuberosum (n=04) | 0.28 | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL | BDL |

3.2 Total As and its species in vegetables

Table 3 summarizes the concentrations of As and its species in edible parts of various vegetables collected from the study area. Moderate variations were observed in the concentrations of As in different vegetable species. The mean As concentration in vegetable tissue ranged between 0.03-1.38 mg kg−1(on (d.w basis), all of which were below the safe MAL (1 mg kg−1) established by Australia for agricultural food crops, while 17% of the samples had As concentration greater than the Chilean National Standard (2005) for As in plants for human consumption (0.50 mg kg−1). However, the mean As concentration in most of the studied vegetables were above the MAL (0.1 mg kg−1) set by WHO/FAO, except Chinese onion, pea, garlic, carrot, yam and cauliflower. The sequence of mean As accumulation in the edible tissue of selected vegetable species (on d.w basis, mg kg−1) was in the order of: hinese onion < pea < garlic = carrot = yam < cauliflower= turnip < radish < lettuce < mint < onion < potato< cucumber < pumpkin <squash-melon<purslane< brinjal<cabbage<tomato<coriander< spinach <Ridge gourd<lady finger/okra < bitter melon. The results revealed that As concentration was higher than those reported by Meharg (2004), Meharg and Rahman (2003), Alam et al. (2002) and Islam et al. (2012) in Bangladesh and were partially consistent with the findings of Santra et al. (2013). The concentrations of As species (DMA, MMA, AsIII and AsV) and the sum of iAs vegetable samples collected from the study area are presented in Table 3. It is observed that AsIII was below detection in most of the samples, except for M. charantia and S. melongena with mean values of 0.09 and 1.0 mg kg−1, respectively. The highest values of AsV and iAs were detected in A. malvaceae, while the lowest was observed in B. olemcea. Moreover, iAs (AsIII + AsV) was not detected in samples of A. cepa, A. sativum, R. sativus, B. rapa, D. carota, C. esculanta, and S. tuberosum(Table 3). The reported concentrations are lower than the previous studies reported by Khan et al. (2014) in Miaoqian village, Longyan, China and greater than those observed by Li et al. (2011) in Chinese food. Likewise, DMA and MMA were below detection in 95% and 50% of the samples (d.w), respectively.

Several mechanisms mediate the availability and bioaccumulation of As in vegetables, which are influenced by physicochemical properties of the soil, such as texture, pH, DOC, cation exchange properties, bacterial community, and physiological properties of the plant (Acosta et al., 2015; Álvarez-Ayuso et al., 2016; Keith et al., 2011). In the study area, the range of As concentrations observed in the same plant species collected from different sites may be be attributed to variations in soil properties as well as location-specific ranges in soil TAs concentrations. For example, higher soil pH leads to precipitation of metals, which is one of the significant mechanisms controlling their availability and accumulation in vegetables (Ok et al., 2010). Soil DOC acts as chelator and reduces metal accumulation in vegetables by forming stable C-metal complexes. Furthermore, interactions between As and different soil elements such as S, Si and P can influence its availability, accumulation and speciation in vegetables; however, these elements were not determined in this study.

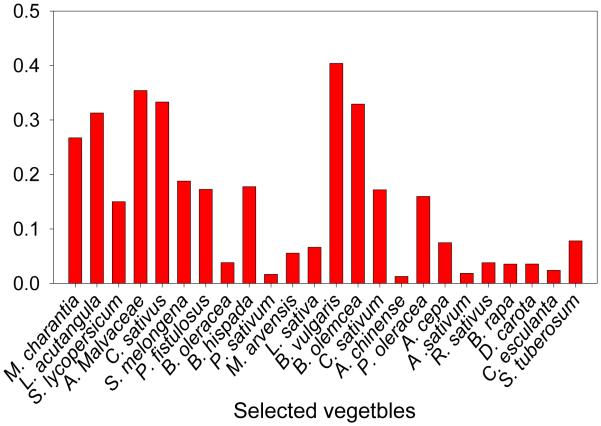

3.3 Bioconcentration factor (BCF)

Figure 2 summarizes the values of BCF for As from soil to the edible portions of various selected vegetables collected from the study sites. BCF is the ratio of the concentration of a particular element in a plant to that in soil and is a vital quantifiable indicator of crop/vegetables contamination which has commonly been used for estimating metal transfer from soil into plants (USEPA, 2005). The highest BCF (0.4) for TAs was observed for B. vulgaris, while the smallest BCF (0.01) was determined for A. chinense. The results show that BCF values for tested edible portions of all the vegetables were less than one. The typical soil to plant BCF of As ranges from 0.01-0.1mg kg−1 for typical plants (Kloke et al., 1984). Plants with BCF values ≥1 are often classified as hyperaccumulators (e.g., Vithanage et al., 2011).

Fig. 2.

Bioconcentration factor (BCF)of TAs for collected vegetable grown in the study area

An As BCF of 0.546 for M. charantia is reported by Bibi et al. (2014), which is approximately twice the As BCF of 0.27 reported in our study for the same plant species. In general the BCF values obtained in this study are in the range of prior reported As BCF values, such as 0.1 for tomato, 0.06 for cucumber (Waqas et al., 2014, 2015) and 0.001-0.12 for other vegetables (Huang et al., 2006). The observed range of BCF factors for the same plant species is expected given that As uptake and bioconcentration are influenced by many factors such as soil pH, Eh, SOC, soil type/texture, Al/Fe/Mn oxides, concentrations of S, P, and As, land use and growth seasons (Song et al., 2006; Waqas et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2007). Soil characteristics varied across the study area, as given in Table S2, which may have affected As bioconcentration in the selected vegetables.

It is observed that BCF values varied from one plant species to the next. This is consistent with prior results and is expected given that metal uptake is a function of plant characteristics. In addition, plant genetics as well as physiological adaptations allow them to bioaccumulate, translocate, and resist high amounts of metals. Generally, plants have an efficient root uptake, effective root-to-shoot translocation, and an enhanced tolerance to As inside plant cells (Wang et al., 2009).

3.4 Average daily intake(ADI) of As and hazard quotient

To assess the human health risk index of As, it is necessary to estimate the level of exposure by quantifying the paths of exposure of As to the target organisms. The exposure of toxic elements to humans occurs through several pathways, including inhalation, food intake and dermal contact. The ADI and HI of As were calculated to evaluate the potential human health risk associated with vegetable consumption. Similar ananlyses were previously reported in other studies (Arenas-Lago et al., 2013; Cerqueira et al., 2011, 2012; Hower et al., 2013; Ramirez-Andreotta et al., 2013b; Ramos et al., 2015; Ribeiro et al., 2013b; Rodriguez-Iruretagiiena et al., 2015; Silva et al., 2011; Martinello et al., 2014).

Table 4 summarizes the values of ADI and HQ for As through food ingestion by the local inhabitants. It was observed that the ADI values were relatively high through the consumption of various selected vegetables grown in the study area. However, all of the ADI values are <1. The highest daily intake of As was estimated for M. charantia, while the lowest was for A. chinense. The ADI values for As through ingestion of gourd, leafy, and rooty vegetables were lower in adults than children, while the total ADI value was 1.36×10−4 mg kg−1 d−1 for adults and 2.58×10−4 mg kg−1 d−1 for children. The ADI data indicated that the As intake for both children and adults through vegetable consumption was lower than the RfD limit (3.0×10−4 mg kg−1 d−1) set by USEPA (2012).

Table 4.

The values of ADI (mgkg−1day−1) and HQ for different vegetable grown in the study area

| ADI |

HQ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | Adults | Children | Adults | Children |

| M. charantia | 6.13×10−5 | 1.15×10−4 | 2.04×10−1 | 3.83×10−1 |

| L. acutangula | 6.00×10−5 | 1.12×10−4 | 2.00×10−1 | 3.75×10−1 |

| C. sativus | 5.51×10−5 | 1.03×10−4 | 1.84×10−1 | 3.44×10−1 |

| P. fistulosus | 3.07×10−5 | 5.75×10−5 | 1.02×10−1 | 1.92×10−1 |

| B. hispada | 2.62×10−5 | 4.91×10−5 | 8.74×10−2 | 1.64×10−1 |

| S. lycopersicum | 3.37×10−5 | 6.53×10−5 | 1.12×10−1 | 2.18×10−1 |

| A. Malvaceae | 4.59×10−5 | 8.90×10−5 | 1.53×10−1 | 2.97×10−1 |

| B. oleracea | 3.40×10−6 | 6.59×10−6 | 1.13×10−2 | 2.20×10−2 |

| S. melongena | 2.89×10−5 | 5.60×10−5 | 9.63×10−2 | 1.87×10−1 |

| P. sativum | 1.70×10−6 | 3.30×10−6 | 5.67×10−3 | 1.10×10−2 |

| C. esculanta | 2.04×10−6 | 3.96×10−6 | 6.80×10−3 | 1.32×10−2 |

| S. tuberosum | 9.52×10−6 | 1.85×10−5 | 3.17×10−2 | 6.15×10−2 |

| M. arvensis | 2.44×10−6 | 4.65×10−5 | 8.13×10−2 | 1.55×10−1 |

| L. sativa | 2.32×10−5 | 4.42×10−5 | 7.72×10−2 | 1.47×10−1 |

| B. vulgaris | 1.55×10−4 | 2.95×10−4 | 5.16×10−1 | 9.84×10−1 |

| B. olemcea | 1.19×10−4 | 2.28×10−4 | 3.98×10−1 | 7.59×10−1 |

| C. sativum | 6.58×10−5 | 1.26×10−4 | 2.19×10−1 | 4.18×10−1 |

| A. chinense | 3.66×10−6 | 6.97×10−6 | 1.22×10−2 | 2.32×10−2 |

| Persalane | 8.78×10−5 | 1.67×10−4 | 2.93×10−1 | 5.58×10−1 |

| A. cepa | 6.12×10−6 | 1.17×10−5 | 2.04×10−2 | 3.89×10−2 |

| A .sativum | 1.53×10−6 | 2.91×10−6 | 5.10×10−3 | 9.71×10−3 |

| R. sativus | 3.06×10−6 | 5.83×10−6 | 2.04×10−1 | 1.94×10−2 |

| B. rapa | 2.55×10−6 | 4.86×10−6 | 2.00×10−1 | 1.62×10−2 |

| D. carota | 1.53×10−6 | 2.91×10−6 | 1.84×10−1 | 9.71×10−3 |

The HQ (which is the ratio of EDD to the RfD) is used to assess the potential for non-cancer adverse health risk through ingestion of As. The RfD is an estimate of a daily oral exposure to humans that is considered to cause minimal substantial health risk of toxic effects throughout the lifespan (USEPA, 2012b). The measured HQ values (Table 4) are <1 for all cases, indicating no substantial risk of non-cancer adverse health effects. In case of TAs, the maximum value for HQ was observed for M. charantia, while the minimum value was for A. chinense.

The Hazard index (HI) characterizes the sum of As exposure through consumption of different vegetables divided by its allowable value. In this study, the HI value was nearly two folds higher in children (8.61×10−1) than adults (4.53×10−1), indicating potential health risk for this group of population. The previous studies have also revealed that the children and teenagers were at high risk due to ingestion of As contaminated vegetables (Jiang et al., 2015)

3.5 Exposure and cancer risk assessment

In order to determine the cancer risks associated with iAs intake via vegetable ingestion in the study area, EDD, and ILTCR were calculated (Table 5). The daily dose of As was estimated using the average vegetable consumption by inhabitants. The values of EDD were higher than the acceptable limits or reference dose (RfD) for daily exposure of TAs without any considerable health risk throughout the lifetime.

Table 5.

The values of EDD (mg kg−1 day−1) and ILTCR for iAs through ingestion of vegetable

| EDD |

ILTCR |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetable | Adults | Children | Adults | Children |

| M. charantia | 1.07×10−5 | 2.00×10−5 | 1.60×10−5 | 8.99×10−5 |

| L. acutangula | 7.56×10−6 | 1.42×10−5 | 1.13×10−5 | 6.37×10−5 |

| B. hispada | 3.11×10−6 | 5.83×10−6 | 4.67×10−6 | 2.62×10−5 |

| S. melongena | 3.40×10−5 | 6.59×10−5 | 5.10×10−5 | 2.97×10−4 |

| S. lycopersicum | 4.42×10−6 | 8.57×10−6 | 6.63×10−6 | 3.86×10−5 |

| A. Malvaceae | 4.59×10−5 | 8.90×10−5 | 6.89×10−5 | 4.00×10−4 |

| C. sativus | 2.32×10−5 | 4.42×10−5 | 3.47×10−5 | 1.99×10−4 |

| B. vulgaris | 1.22×10−5 | 2.32×10−5 | 1.83×10−5 | 1.05×10−4 |

| B. olemcea | 7.31×10−6 | 1.39×10−5 | 1.10×10−5 | 6.28×10−5 |

| C. sativum | 6.58×10−5 | 1.26×10−4 | 9.88×10−5 | 5.65×10−4 |

The cancer risk was characterized using, incremental lifetime cancer risk (ILTCR), which is determined from multiplying EDD of inAs by the cancer slope factor (CSF). The CSF has a maximum bound level of 1.5 and 4.5 for adults and children, respectively for As, approaching a 95% confidence level (USEPA, 2012b). The ILTCR illustrates the cancer risk for an individual who consumes that vegetable following the assumption used in the calculation of EDD. USEPA, (2012b) reported that ILTCR is the theoretical maximum number of cancer cases that are expected to develop due to that exposure and concentration.

The ILTCR data indicated that the cancer risk was one extra case per 100,000 for adults through ingestion of gourd vegetable grown in the study area, while this value increased to 3.6 per 100,000 for children. In the case of Solanaceous vegetable, the risk was 1.8 extra individuals per 100,000 in adults and 10 extra per 100,000 for children. The leafy vegetables showed the highest cancer risk development with 2.3 and 13 individuals per 100,000 adults and children, respectively. Interestingly no cancer risk development in both children and adults was observed for the rooty vegetables. The overall cancer risk development through ingestion of all types of vegetables was 5.7 fold higher in children (2.74×10−4) than adults (4.77×10−4). Uddh-Söderberg et al. (2015) reported the development of cancer risk in 20 extra individuals per 100,000 through ingestion of homegrown vegetables in south-eastern Sweden.

4. Conclusion

As concentrations in soil samples of the five districts ranged from 3.0-3.9 mg kg−1, and showed very little variation from site to site. The mean As concentration in edible portions (d.w) for most of the studied vegetables exceeded the WHO/FAO safe MAL (0.1 mg kg−1), except A. chinense, P. sativum, A. sativum, D. carota, C. esculanta, B. oleracea. The relatively high As concentrations in groundwater/irrigation water may be a potential food contaminant in the study area. The highest BCF for As was observed for B. vulgaris, while the smallest BCF was determined for A. chinense. The highest daily intake of As was estimated in M. charantia, while the lowest it was in B.vulgaris. The results of this study revealed that the values of HRI for As were < 1 for most of the vegetable species examined. Likewise, the results indicate that there is very low cancer risk from ingestion of edible portions of tested vegetables, although this could vary according to actual ingestion rates in individuals. However, regular monitoring is suggested to assess future risk associated with heavy metal contamination, especially toxic elements such as As, and uptake in food crops grown in the study area. Further research work is needed to investigate the contribution of As and its species from all water sources used for irrigation purposes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This study was financially supported by Directorate of Science and Technology (Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), Higher Education Commission, Pakistan under International Research Support Initiative Program (IRSIP I-8/HEC/HRD/2013/2784) and the Superfund Research Program of the NIEHS (P42 ES04940). The authors thank the whole staff of Arizona Laboratory for Emerging Contaminants (ALEC), University of Arizona, USA, for providing analytical facilities for this research study.

Footnotes

No conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Acosta JA, Arocena JM, Faz A. Speciation of arsenic in bulk and rhizosphere soils from artisanalcooperative mines in Bolivia. Chemosphere. 2015;138:1014–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MGM, Allinson G, Stagnitti F, Tanaka A, Westbrooke M. Metal concentrations in rice and pulses of SamtaVillage, Bangladesh. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2002;69:323–9. doi: 10.1007/s00128-002-0065-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Ayuso E, Abad-Valle P, Murciego A, Villar-Alonso A. 206. Arsenic distribution in soils and rye plants of a cropland located in anabandoned mining area. Sci. Total Environ. 542:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelia L, Seyffert H, Samuel MW, Joy C, Andrew S, Fendorf S. Arsenic localization, speciation, and co-occurrence with iron on rice (Oryza sativa L.) roots having variable Fe coatings. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:8108–8113. doi: 10.1021/es101139z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arain MB, Kazi TG, Baig JA, Jamali MK, Afridi HI, Shah AQ, Jalbani N, Sarfraz RA. Determination of arsenic levels in lake water, sediment, and foodstuff from selected area of Sindh, Pakistan: estimation of daily dietary intake. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009;47:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas-Lago D, Veja FA, Silva LS, Andrade L. Soil interaction and fractionation of added cadmium in some Galician soils. Microchem. J. 2013;110:681–690. [Google Scholar]

- Baig JA, Kazi TG. Translocation of arsenic contents in vegetables from growing media of contaminated areas. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe. 2012;75:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig JA, Kazi TG, Arain MB, Afridi HI, Kandhro GA, Sarfraz RA, Jamal MK, Shah AQ. Evaluation of arsenic and other physico-chemical parameters of surface and groundwater of Jamshoro, Pakistan. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;166:662–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergqvist C, Herbert R, Persson I, Greger M. Plants influence on arsenic availability and speciation in therhizosphere, roots and shoots of three different vegetables. Environ. Pollut. 2014;184:540–546. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibi B, Khan ZI, Ahmad K, Ashraf M, Hussain A, Akram NA. Vegetables as a Potential Source of Metals and Metalloids for Human Nutrition: A Case Study of Momordica charantia Grown in Soil Irrigated with Domestic Sewage Water in Sargodha, Pakistan. Pak. J. Zool. 2014;46(3):633–641. [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira B, Vega FA, Serra C, Silva LFO, Andrade ML. Time of flight secondary ion mass spectrometry and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy/energy dispersive spectroscopy: A preliminary study of the distribution of Cu2+ and Cu2+/Pb2+ on a Bt horizon surfaces. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011;195:422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira B, Vega FA, Silva LFO, Andrade L. Effects of vegetation on chemical and mineralogical characteristics of soils developed on a decantation bank from a copper mine. Sci. Total Environ. 2012:421–422. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.01.055. 220-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CY, Yu HY, Chen JJ, Li FB, Zhang HH, Liu CP. Accumulation of heavy metals in leafy vegetables from agricultural soils and associated potential health risks in the Pearl River Delta, South China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014;186:1547–1560. doi: 10.1007/s10661-013-3472-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Huang B, Hu B, Weindorf DC, Liu X, Niedermann S. Assessing the risks of trace elements in environmental materials underselected greenhouse vegetable production systems of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2014:470–471. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.10.095. 1140-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen K. The arsenic threat worsens. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001;35:286A–291A. doi: 10.1021/es012394f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DCR1998 Khan DI, editor. District Census Report of Lakki Marwat, Bannu. Kohat and Hangu; Population Census Organization, Statistic Division, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Statistic Government of Pakistan. :1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Devesa V, Velez D, Montoro R. Effect of thermal treatments on arsenic species contents in food. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008;46:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Ma LQ, Li Y. Characteristics and mechanisms of hexavalent chromium removal by biochar from sugar beet tailing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011;190:909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dummer TJB, Yu ZM, Nauta L, Murimboh JD, Parker L. Geostatistical modelling of arsenic in drinking water wells and related toenail arsenic concentrations across Nova Scotia. Canada. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;505:1248–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EA Engineering, Science, and Technology, Inc. Remedial Investigation Report Iron King Mine Humboldt Smelter Superfund Site DeweyHumboldt,YavapaiCounty,Arizona. 2010 Available: http://yosemite.epa.gov/r9/sfund/r9sfdocw.nsf/3dc283e6c5d6056f88257426007417a2/9ff58681f889089c882576fd0075ea2f!OpenDocument2010.[accessed 19 June 2012]

- Egbenda PO, Thullah F, Kamara I. A physio-chemical analysis of soil and selected fruits in one rehabilitated out site in the sierra rutile environs for the presence of heavy metals: Lead, Copper, Zinc, Chromium, and Arsenic. Afr. J. Pure Appl. Chem. 2015;9:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ellice MC, Dowling K, Smith J, Smith E, Naidu R. Proceedings of arsenic in the Asia-Pacific region: managing arsenic for our future. Vol. 124. Adelaide; South Australia: Nov, 2001. Abandoned mine tailings with high arsenic concentrations: A case study with implications for regional Victoria; pp. 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi A, Masuda H, Siddiqui R, Naseem M. Sources of Arsenic and Fluoride in Highly Contaminated Soils Causing Groundwater Contamination in Punjab, Pakistan. Arch Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2009;56:693–706. doi: 10.1007/s00244-008-9239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatmi Z, Azam I, Ahmed F, Kazi A, Gill AB, Kadir MM, Ahmed M, Ara N, Janjua NZ, Panhwar SA, Tahir A, Ahmed T, Dil A, Habaz A, Ahmed S. Health burden of skin lesions at low arsenic exposure through groundwater in Pakistan, is river the source? Environ. Res. 2009;109:575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendorf S, Michael HA, Van-Geen A. For field measurements and sensors. Vol. 328. US EPA; Washington, DC: 2010. Spatial and temporal variations of groundwater arsenic in south and southeast Asia. Sc. pp. 1123–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu PP, Cheng SH, Coop L, Xia Q, Culp SJ, Tolleson WH, Wamer WG, Howard PC. Photoreaction, phototoxicity, and photocarcinogenicity of retinoids. J. Environ. Sci. Health. 2003;21:165–197. doi: 10.1081/GNC-120026235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia KO, Teixeira EC, Agudelo-Castaneda DM, Braga M, Alabarse PG, Wiegand F, Kautzmann RM, Silva LFO. Assessment of nitro-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in PM1 near an area of heavy-duty traffic. Sci. Total Environ. 2014:479–480. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.01.126. 57-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerba CP. Risk Assessment. In: Pepper IL, Gerba CP, Brusseau ML, editors. Environ-mental and Pollution Science. Elsevier Inc; Amsterdam: 2006. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hall GEM, Pelachat JC, Gautier G. Stability of inorganic arsenic (III) and arsenic (V) in water samples. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 1999;14:205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Helgensen H, Larsen EH. Bioavailability and speciation of arsenic in carrots grown in contaminated soil. Analyst. 1998;123:791–796. doi: 10.1039/a708056e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hower JC, O’Keefe JMK, Henke KR, Wagner NJ, Copley G, Blake DR, Garrison T, Oliveira MLS, Kautzmann RM, Silva LFO. Gaseous emissions and sublimates from the Truman Shepherd coal fire, Floyd County, Kentucky: A re-investigation following attempted mitigation of the fire. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2013;116:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Jia Y, Sun GX, Zhu YG. Arsenic speciation and volatilization from flooded paddy soils amended with different organic matters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:2163–2168. doi: 10.1021/es203635s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang RQ, Gao SF, Wang WL, Staunton S, Wang G. Soil arsenic availability and the transfer of soil arsenic to crops in suburban areas in Fujian Province, southeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 2006:531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC International Agency for Research on Cancer, Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risk to human. some drinking water disinfectants and contaminants, including arsenic, lyons, France. 2004;84:39–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISEST . Arsenic. IARC; Geneva: 2013. International Symposium on Environmental Science and Technology; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Islam MR, Hugh-Brammer GK, Rahman MM, Raab A, Jahiruddin M, Solaiman ARM, Andrew A, Meharg G, Norton J. Arsenic in rice grown in low-arsenic environments in Bangladesh. Water Qual. Expo. Health. 2012;4:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Jan FA, Ishaq M, Khan S, Ihsanullah I, Ahmad I, Shakirullah M. A comparative study of human health risks via consumption of food crops grown on wastewater irrigated soil (Peshawar) and relatively clean water irrigated soil (lower Dir) J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;179:612–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Huang H, Sun GX, Zhao FJ, Zhu YG. Pathways and relative contributions to arsenic volatilization from rice plants and paddy soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:8090–8096. doi: 10.1021/es300499a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Zeng X, Fan X, Chao S, Zhu M, Cao H. Levels of arsenic pollution in daily foodstuffs and soils and its associated human health risk in a town in Jiangsu Province, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe. 2015;122:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josef G, Thundiyil Y, Smith AH, Steinmaus C. Seasonal variation of arsenic concentration in wells in Nevada. Environ. Res. 2007;104:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph T, Dubey B, McBean EA. A critical review of arsenic exposures for Bangladeshi adults. Sci. Total Environ. 2015a:527–528. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.05.035. 540-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph T, Dubey B, McBean EA. Human health risk assessment from arsenic exposures in Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 2015b:527–528. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.05.053. 552-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabata-Pendias A. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants. fourth CRC; Boca Raton: 2011. p. 534. [Google Scholar]

- Kabata-Pendias A, Pendias H. Trace elements in soil and plants. third CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Karim RA, Hossain SM, Miah MMH, Nehar K, Mubin MSH. Arsenic and heavy metal concentrations in surface soils and vegetables of Feni district in Bangladesh. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008;145:417–425. doi: 10.1007/s10661-007-0050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazi TG, Arain MB, Baig JA, Jamali MK, Afridi HI, Jalbani N. The correlation of arsenic levels in drinking water with the biological samples of skin disorders. Sci. Total Environ. 2009;407:1019–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith A, Singh B, Singh BP. Interactive priming of biochar and labile organic matter mineralization in a smectite-rich soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:9611–9618. doi: 10.1021/es202186j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Cao Q, Zheng YM, Huang YZ, Zhu YG. Health risks of heavy metals in contaminated soils and food-crops irrigated with wastewater in Beijing, China. Environ. Pollut. 2008;152:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Rehman S, Khan AZ, Khan MA, Shah MT. Soil and vegetables enrichment with heavy metals from geological sources in Gilgit, northern Pakistan. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe. 2010;73:1820–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Waqas M, Ding F, Shamshad I, Arp HPH, Li G. The influence of various biochars on the bioaccessibility and bioaccumulation of PAHs and potentially toxic elements to turnips (Brassica rapa L.) J. Hazard. Mater. 2015b;300:243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Khan S, Khan MA, Qamar Z, Waqas M. The uptake and bioaccumulation of heavy metals by food plants, their effects on plants nutrients, and associated health risk: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015a;22:13772–13799. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Reid BJ, Li G, Zhu YG. Application of biochar to soil reduces cancer risk via rice consumption: A case study in Miaoqian village, Longyan, China. Environ. Int. 2014;68:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloke A, Sauerback DR, Vetter H. The contamination of plants and soils with heavy metals and the transport of metals in terrestrial food chains. In: Nriagu J, editor. Changing Metal Cycles and Human Health. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1984. pp. 113–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kronbauer MA, Izquierdo M, Dai S, Waanders FB, Wagner NJ, Mastalerz M, Hower JC, Oliveira MLS, Taffarel SR, Bizani D, Silva LFO. Geochemistry of ultra-fine and nano-compounds in coal gasification ashes: A synoptic view. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;456-457:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Sun GX, Williams PN, Nunes L, Zhu Y-G. Inorganic arsenic in Chinese food and its cancer risk. Environ. Int. 2011;37:1219–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MS, Yeo IW, Clement TP, Roh Y, Lee KK. Mathematical model for predicting microbial reduction and transport of arsenic in groundwater system. J. Water. 2007;41:2079–2088. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llobet JM, Falco G, Casas C, Teixido A, Domingo JL. Concentrations of arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead in common foods and estimated daily intake by children, adolescents, adults, and seniors of Catalonia, Spain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:838–842. doi: 10.1021/jf020734q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomax C, Liu W-J, Wu L, Xue K, Xiong J, Zhou J, McGrath SP, Meharg AA, Miller AJ, Zhao F-J. Methylated arsenic species in plants originate from soil microorganisms. New Phytol. 2012;193:665–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinello K, Oliveira MLS, Molossi FA, Ramos CG, Teixeira EC, Kautzmann RM, Silva LFO. Direct identification of hazardous elements in ultra-fine and nanominerals from coal fly ash produced during diesel co-firing. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;470-471:444–452. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinello K, Oliveira MLS, Molossi FA, Ramos CG, Teixeira EC, Kautzmann RM, Silva LFO. Direct identification of hazardous elements in ultra-fine and nanominerals from coal fly ash produced during diesel co-firing. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;470-471:444–452. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Sánchez MJ, Martínez-López S, García-Lorenzo ML, Martínez-Martínez LB, Pérez-Sirvent C. Evaluation of arsenic in soils and plant uptake using various chemical extraction methods in soils affected by old mining activities. Geoderma. 2011;160:535–541. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren RG, Naidu R, Smith J, Tiller KG. Fractionation and distribution of arsenic in soils contaminated by cattle dip. J. Environ. Quality. 1998;27:348–354. [Google Scholar]

- Meharg AA. Arsenic in rice understanding a new disaster for South-East Asia. Trend. Plant Sci. 2004;9:415–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meharg AA, Rahman MD. Arsenic contamination of Bangladesh paddy field soils: implications for rice contribution to arsenic consumption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003;37:229–34. doi: 10.1021/es0259842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Anke M. Distribution of cadmium in the food chain (soil-plant-human) of a cadmium exposed area and the health risks of the general population. Sci. Total Environ. 1994;156:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(94)90352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Food Authority . Australian Food Standards Code: March 1993. Australian Government Publishing Service; Canberra, Australia: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (NRC) Arsenic in drinking water. 2001 update. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- NCh, 409 . Norma Chilena 409/1.Of. Agua Potable Parte 1: Requisitos. Instituto Nacional de Normalización (INN); Santiago de Chile: 2005. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann RB, St., Vincent AP, Roberts LC, Badruzzaman ABM, Ali MA, Harvey CF. Rice field geochemistry and hydrology: An explanation for why groundwater irrigated fields in Bangladesh are net sinks of arsenic from groundwater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:2072–2078. doi: 10.1021/es102635d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng JC, Wang J, Shraim A. A global health problem caused by arsenic from natural sources. Chemosphere. 2003;52:1353–1359. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00470-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ok YS, Oh, Ahmad M, Hyun S, Kim KR, Moon DH, Lee SS, Lim KJ, Jeon WT, Yang JE. Effects of natural and calcined oyster shells on Cd and Pb immobilization in contaminated soils. Environ. Earth Sci. 2010;61:1301–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira LM, Lena QM, Jorge AG, Luiz RG, Jason TL. Effects of arsenate, chromate and sulfate on arsenic and chromium uptake and translocation by arsenic hyper-accumulator Pteris vittata L. Environ. Pollut. 2014;184:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira MLS, Ward CR, Izquierdo M, Sampaio CH, de Brum IAS, Kautzmann RM, Sabedot S, Querol X, Silva LFO. Chemical composition and minerals in pyrite ash of an abandoned sulphuric acid production plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2012;430:34–47. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira MLS, Ward CR, Sampaio CH, Querol X, Cutruneo CMNL, Taffarel, Silvio R, Silva LFO. Partitioning of Mineralogical and Inorganic Geochemical Components of Coals from Santa Catarina, Brazil, by Industrial Beneficiation Processes. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2013;116:75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro I, Gomez M, Camara C, Palacios MA. Arsenic speciation in environmental and biological samples extraction and stability studies. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2003;495:85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Raab A, Ferreira K, Meharg AA, Feldmann J. Can arsenic-phytochelatin complex formation be used as an indicator for toxicity in Helianthus annuus? J. Exp. Bot. 2007;58:1333–1338. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MA, Hasegawa H, Rahman MM, Miah MAM, Tasmin A. Arsenic accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L. human exposure through food Chain. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe. 2008;69:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MM, Naidu R, Bhattacharya P. Arsenic contamination in groundwater in the Southeast Asia region. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2009;31:9–21. doi: 10.1007/s10653-008-9233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Pandey AK, Sharma YK, Khare PB, Srivastava PK, Singh N. Metabolic adaptation of Pteris vittata L. gametophyte to arsenic induced oxidative stress. Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102:9827–9832. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan MAE, Al-Ashkar EA. The effect of different fertilizers on the heavy metals in soil and tomato plant. Aust. J. Basic Appl. 2007;1:300–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Andreotta MD, Brusseau ML, Artiola JF, Maier RM. A greenhouse and field-based study to determine the accumulation of arsenic in common homegrown vegetables grown in mining-affected soils. Sci. Total Environ. (2013a);443:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.10.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Andreotta MD, Brusseau ML, Beamer P, Maier RM. Home gardening near a mining site in an arsenic-endemic region of Arizona: assessing arsenic exposure dose and risk via ingestion of home garden vegetables, soils, and water. Sci. Total Environ. (2013b);454/455:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.02.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos CG, Querol X, Oliveira MLS, Pires K, Kautzmann RM, Oliveira LFS. A preliminary evaluation of volcanic rock powder for application in agriculture as soil a remineralizer. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;512-513:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattan RK, Datta SP, Chhonkar PK, Suribabu K, Singh AK. Long-term impact of irrigation with sewage effluents on heavy metal content in soils, crops and groundwater-a case study. Agri. Ecosys. Environ. 2005;109:310–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro J, DaBoit K, Flores D, Kronbauer MA, Silva LFO. Extensive FE-SEM/EDS, HR-TEM/EDS and ToF-SIMS studies of micron- to nano-particles in anthracite fly ash. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;452-453:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro J, DaBoit K, Flores D, Ward CR, Silva LFO. Identification of nanominerals and nanoparticles in burning coal waste piles from Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408:6032–6041. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro J, Taffarel SR, Sampaio CH, Flores D, Silva LFO. Mineral speciation and fate of some hazardous contaminants in coal waste pile from anthracite mining in Portugal. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2013a;109-110:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-ruretagiiena A, Fdez-Ortiz de Vallejuelo S, Gredilla A, Ramos CG, Oliveira MLS, Arana G, De Diego A, Madariaga JM, Silva LFO. Fate of hazardous elements in agricultural soils surrounding a coal power plant complex from Santa Catarina (Brazil) Sci. Total Environ. 2015;508:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Chancho MJ, López-Sánchez JF, Rubio R. Analytical speciation as a tool to assess arsenic behavior in soils polluted by mining. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007;387:627–35. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0939-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchís J, Oliveira LFS, De Leão FB, Farrè M, Barcelò D. Liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure photoionization-Orbitrap analysis of fullerene aggregates on surface soils and river sediments from Santa Catarina (Brazil) Sci. Total Environ. 2015;505:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEPA . Environmental Quality Standards for Soils. State Environmental Protection Administration; China: 1995. GB15618-1995. [Google Scholar]

- SEPA . The Limits of Pollutants in Food. State Environmental Protection Administration; China: 2005. GB 2762-2005. [Google Scholar]

- Silva LFO, Querol X, da Boit KM, Fdez-Ortiz de Vallejuelo S, Madariaga JM. Brazilian Coal Mining Residues and Sulphide Oxidation by Fenton s Reaction: an accelerated weathering procedure to evaluate possible environmental impact. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011;186:516–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva LFO, Moreno T, Querol X. An introductory TEM study of Fe-nanominerals within coal fly ash. Sci. Total Environ. 2009;407:4972–4974. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva LFO, Sampaio CH, Guedes A, Fdez-Ortiz de Vallejuelo S, Madariaga JM. Multianalytical approaches to the characterisation of minerals associated with coals and the diagnosis of their potential risk by using combined instrumental microspectroscopic techniques and thermodynamic speciation. Fuel. 2012;94:52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley PL, Kinniburgh DG. A review of the source, behaviour and distribution of arsenic in natural waters. Appl. Geochem. 2002;17:517–568. [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Naidu R, Alston AM. Chemistry of arsenic in soils: I. Sorption of arsenate and arsenite by four Australian soils. J. Environ. Qual. 1999;28:1719–1726. [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Smith J, Naidu R. Distribution and nature of arsenic along former railway corridors of South Australia. Sci. Total Environ. 2006;363:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EA, Juhasz L, Weber J. Arsenic uptake and speciation in vegetables grown under greenhouse conditions. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2009;31:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s10653-008-9242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Zhao F-J, McGrath SP, Luo Y-M. Influence of soil properties and aging on arsenic phytotoxicity. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006;25:1663–1670. doi: 10.1897/05-480r2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar BBM, Han FX, Diehl SV, Monts DL, Su Y. Effect of phyto-accumulation of arsenic and chromium on structural and ultra-structural changes of brake fern (Pterisvittata) Braz. Soc. Plant Physiol. 2011;23:285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Uddh-Söderberg TE, Gunnarsson SJ, Hogmalm KJ, Boel MI, Lindegård G, Augustsson ALM. An assessment of health risks associated with arsenic exposure via consumption of homegrown vegetables near contaminated glassworks sites. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;536:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA Human health risk assessment protocol for hazardous waste combustion facilities. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- USEPA . Exposure Factors Handbook 2011 Edition (Final) US Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, DC: 2011. EPA/600/R09/052F. Available at: http://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/risk/recordisplay.cfm?deid=236252#Download. [Accessed20 September 2012] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA Integrated risk information system (IRIS) 2012 Available at: http://www.epa.gov/IRIS/ [accessed August 2012]

- Van-Herreweghe S, Swennen R, Vandecasteele C, Cappuyns V. Solid phase speciation of arsenic by sequential extraction in standard reference materials and industrially contaminated soil samples. Environ. Pollut. 2003;122:323–42. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(02)00332-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vithanage M, Dabrowska BB, Mukherjee AB, Bhattacharya P. Arsenic uptake by plants and possible phytoremediation applications: a brief overview. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2011:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Waqas M, Khan S, Chao C, Shamshad I, Qamar Z, Khan K. Quantification of PAHs and health risk via ingestion of vegetable in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;497-498:448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.07.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas M, Li G, Khan S, Shamshad I, Reid BJ, Qamar Z, Chao C. Application of sewage sludge and sewage sludge biochar to reduce polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and potentially toxic elements (PTE) accumulation in tomato. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015;22:7071–7081. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waseem A, Arshad J, Iqbal F, Sajjad A, Mehmood Z, Murtaza G. Pollution Status of Pakistan: A Retrospective Review on Heavy Metal Contamination of Water, Soil, and Vegetables. BioMed Res. Int. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/813206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/813206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . Recommendations. 3rd Vol. 1. Geneva: 2008. World Health Organization. Guidelines for drinking water quality. [Google Scholar]

- Williams PN, Villada A, Deacon C, Raab A, Figuerola J, Green AJ, Feldmann J, Mehrag AA. Greatly enhanced arsenic shoot assimilation in rice leads to elevated grain levels compared to wheat and barley. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:6854–6859. doi: 10.1021/es070627i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SC, Lockwood PV, Ashley PM, Tighe M. The chemistry and behaviour of antimony in the soil environment with comparisons to arsenic: a critical review. Environ. Pollut. 2010;158:1169–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YG, Xu YN, Zhang JH, Hu SH. Evaluation of ecological risk and primary empirical research on heavy metals in polluted soil over Xiaoqinling gold mining region, Shaanxi, China. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 2010;20:688–694. [Google Scholar]

- Yao LX, Li GL, Dang Z, He ZH, Zhou CM, Yang BM. Arsenic uptake by two vegetables grown in two soils amended with As-bearing animal manures. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;164:904–910. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.08.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavala YJ, John MD. Arsenic in rice: I. estimating normal levels of total arsenic in rice grain. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:3856–3860. doi: 10.1021/es702747y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YG, Williams PN, Meharg AA. Exposure to inorganic arsenic from rice: A global health issue? Environ. Pollut. 2008;154:169–171. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.