Abstract

Background

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a brain stimulation technique used to examine causal relationships between brain regions and cognitive functions. The effects from tDCS are complex, and the extent to which stimulation reliably affects different cognitive domains is not fully understood and continues to be debated.

Objective/Hypothesis

To conduct a meta-analysis of studies examining the effects of single-session anodal tDCS on language.

Methods

The meta-analysis examined the behavioral results from eleven experiments of single-session anodal tDCS and language processing in healthy adults. The means and standard deviations of the outcome measures were extracted from each experiment and entered into the meta-analyses. In the first analysis, we examined the effects of single-session tDCS across all language studies. Next, a series of sub-analyses examined the effects of tDCS on specific tasks and stimulation protocols.

Results

There was a significant effect from anodal single-session tDCS in healthy adults compared to sham (p=0.001) across all language measures. Next, we found significant effects on specific stimulation protocols (e.g., offline measures, p=0.002), as well as specific tasks and electrode montages (e.g., verbal fluency measures and left prefrontal cortex, p=0.035).

Conclusions

The results indicate that single-session tDCS produces significant and reliable effects on language measures in healthy adults.

Keywords: transcranial direct current stimulation, tDCS, language, meta-analysis, reliability

Introduction

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a relatively new technique in neuroscience research and its use has rapidly grown over the last decade [1-4]. In healthy adults, tDCS offers a tool for testing causal relationships between brain regions and their underlying cognitive functions (e.g., motor control, working memory, language) [5-8]. This technique has also been tested in clinical populations for a wide variety of uses, ranging from psychiatric conditions to neurological disorders caused by stroke and neurodegenerative diseases [9-15]. Based on research in animals and humans, it is generally thought that applying anodal tDCS to a brain area leads to increased neural excitability in that region, while cathodal stimulation leads to decreased neural excitability [1, 2, 16-21]. However the effects from tDCS are complex and appear to be affected by a number of stimulation parameters, including intensity and duration [1, 2, 22, 23], the types of cognitive processes engaged during stimulation [24, 25], stimulation polarity [1, 19-22, 26, 27], the underlying levels of cortical neurochemicals [28, 29], and genetics [30]. Research examining the extent and reliability of tDCS effects is ongoing, and it remains an important challenge to determine the parameters under which tDCS can affect cognition and neurophysiology.

The use of tDCS is widespread in both basic research and in clinical settings. Hundreds of researchers use the technique, and there have been over a thousand publications involving tDCS in the last decade. However, a recent meta-analysis examined the reliability of single-session tDCS on cognition and reported null findings for the effects of tDCS across a variety of cognitive domains [31]. Given the widespread use of direct current stimulation and the broad claims that have been made based on these recent null findings, it is important that the results from this meta-analysis are able to be validated. If single-session tDCS has no effect on cognition, this finding would have far-reaching implications for the field and for the future of this technique.

A detailed examination of the meta-analysis by Horvath and colleagues has raised a number of problematic issues in the methodological approach, as reviewed by a number of researchers [32-34]. It therefore remains unclear whether there is truly no effect of single-session tDCS on cognition. The goal of the analyses presented in this paper was to examine this question in the cognitive domain of language. To do this, we analyzed all of the behavioral data from the tDCS papers included in the previous review of language studies [31]. Our meta-analysis was structured into two levels. The first level consisted of a main meta-analysis that examined data from across all language studies using the same behavioral measure (e.g., accuracy measures), but that differed in task (e.g., verbal fluency or novel language learning) and the time-point of data collection (e.g., online or offline). This allowed us to generalize across studies in order to achieve maximum power to detect whether effects on language processes were present. The second level of our investigation consisted of sub-analyses that entailed more narrowly focused examinations of the effects from tDCS for individual tasks (e.g., verbal fluency), electrode montages (e.g., left PFC), and stimulation conditions (e.g., offline). This allowed us to examine more specific effects relating to particular tasks and stimulation conditions. The findings from this meta-analysis reveal significant effects across many behavioral measures in the language studies and provide important implications for future research using tDCS.

Methods

Individual study selection and analysis

Our goal was to analyze behavioral data from language studies that had applied tDCS in healthy adults. Previously, Horvath and colleagues [31] had analyzed data from these studies and found no effect from stimulation. However, a number of investigators revealed substantial weaknesses in these analyses, stemming from the use of inconsistent data-selection criteria and the lack of methodological details explaining these decisions [32-34]. To address these issues, we provide a detailed outline of how data were selected for our study and for the corresponding analyses performed by Horvath and colleagues (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data selection criteria for meta-analysis of tDCS studies of language and key differences from Horvath et al. (2015)

| Study | Study description and data selection | Electrode placement | Type of measure | SMD | Discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Floel et al. 2008

[37] |

Floel and colleagues examined the effect of tDCS on word learning. Participants were trained on novel word associations over five blocks (~30 minutes) while receiving real stimulation or sham for the first 20 minutes. Following training, they administered a test to examine whether subjects had learned the novel word associations (i.e., the transfer test). The data from this test constituted the main behavioral measurement for word learning accuracy in the experiment. This measure yields an SMDadjusted of 0.78. |

Anode = Wernicke’s area (CP5) Cathode = Right supraorbital region |

Accuracy: offline novel language learning |

Anode measure = 94.67 Anode SD = 5.06 Sham measure = 89.72 Sham SD = 7.31 SMD = 0.79 SMDadjusted = 0.78 |

Citation #40 in Horvath et al. [17] This value differs from that used by Horvath and colleagues because they selected data from Block 4 (i.e., one of the learning blocks; stimulation also ended in the middle of this block). We believe this measure is not a suitable measure because it is collected during the training phase, and, furthermore, it reflects a mixture of both online and offline portions of the stimulation protocol. If the results from Block 4 are used, then the SMD is 0.18. |

|

Fiori et al. 2011

[35] |

Fiori and colleagues examined the effect of tDCS on word learning in healthy adults. The authors reported the accuracy of novel word learning as a single measure of performance across the learning blocks and test blocks, and this measure was both during stimulation and after stimulation (i.e., online and offline). It was included in the main meta-analysis that examines the effects across both offline and online measures, but it was not included in the sub-analyses where offline and online measurements were examined separately. This measure yields an SMDadjusted of 0.27. |

Anode = Wernicke’s area (CP5) Cathode = Right supraorbital region |

Accuracy: online and offline novel language learning |

Anode measure = 62 Anode SD = 30 Sham measure = 54 Sham SD = 27 SMD = 0.28 SMDadjusted = 0.27 |

Citation #41 in Horvath et al. [17] Same as reported by Horvath and colleagues |

|

Cerutti et al. 2009

Experiment 1 [34] |

Cerutti and colleagues examined the effects of tDCS on a remote-associates task and a letter verbal fluency task (both offline and online). A measure of verbal fluency was collected before stimulation and again during stimulation, towards the end of the protocol. The measure is reported as a pre-stimulation compared to post-stimulation online measure of verbal fluency. This measure yields an SMDadjusted of −0.16. |

Anode = Left PFC (F3) Cathode = Right supraorbital region |

Accuracy: online verbal fluency measure |

Experiment 1:

Anode measure = 2.31 Anode SD = 4.8 Sham measure = 3.07 Sham SD = 4.4 SMD = −0.17 SMDadjusted = −0.16 |

Citation #44 in Horvath et al. [17] Same as reported by Horvath and colleagues |

|

Cerutti et al.

2009 Experiment 2 [34] |

Experiment 2 was similar in design to experiment 1, except that the second verbal fluency task was collected after the end of stimulation (i.e., offline). The measure was reported as a pre-stimulation compared to post-stimulation offline measure of verbal fluency. This measure yields an SMDadjusted of 0.23. |

Anode = Left PFC (F3) Cathode = Right supraorbital region |

Accuracy: Offline verbal fluency measure |

In experiment 2, the authors report the pre- test to post-test t- statistic between the sham and the anodal F3 conditions. Since the means and standard deviations were not reported, it is necessary to calculate the SMD value from the t-value, as described in the Methods section. t(11) = 0.587, p = 0.57 SMD = 0.24 SMDadjusted = 0.23 |

Citation #44 in Horvath et al. [17] Same as reported by Horvath and colleagues |

|

Penolazzi et al.

2013 [42] |

Penolazzi and colleagues examined the effects of several anodal tDCS montages on semantic verbal fluency and simple reaction time tasks (offline). The “frontal” electrode montage in this paper used an anode on F3 and a cathode on the right supraorbital region. The “frontal” montage was selected for the meta-analysis in this paper because this was most consistent with the other experiments using frontal montages included in the same set of analyses. This experiment was a between-subject design where a pre-stimulation and two post-stimulation measures of verbal fluency were obtained in each stimulation group (N = 18 participants per condition). Both post- stimulation measures were collected within 20 minutes after the end of stimulation. To estimate the offline effects of stimulation on verbal fluency, we used an average of both post-stimulation measures to represent the effect after stimulation. This is then compared to the pre-stimulation measure, to obtain a pre-stimulation compared to post-stimulation difference score for both sham and frontal anodal stimulation conditions. This measure yields an SMDadjusted of 0.33. |

Anode = Left PFC (F3) Cathode = Right supraorbital region |

Accuracy: offline verbal fluency measure |

Anode measure = 2.12 Anode SD = 7.38 Sham measure = −0.36 Sham SD = 7.38 SMD = 0.34 SMDadjusted = 0.33 |

Citation #46 in Horvath et al. [17] Horvath et al. did not select the pre- stimulation compared to post-stimulation measure, as they did for Cerutti et al. [19]. Here, Horvath and colleagues selected only the ”post-stimulation 1” score to compare between the stimulation and sham condition. It is important to use a pre-stimulation versus post-stimulation difference score because this study was a between-subject design and the subjects differed in verbal fluency at the pre- stimulation baseline. If only the “post- stimulation 1” score is selected, this yields an SMD of −0.23 (a negative effect driven by a between-subject difference at baseline). Additionally, Horvath and colleagues count the sham group multiple times in order to include each experimental electrode montage as a separate effect (e.g., up to four times in the Horvath et al. [17] meta-analysis), which is problematic since there is only one sham group and it should not be counted as multiple independent measures. |

|

Cattaneo et al.

2011 [39] |

Cattaneo and colleagues examined the effects of tDCS on verbal fluency (offline). They administered two verbal fluency tasks (letter and semantic) after the end of stimulation. The effect on both verbal fluency tasks yields an SMDadjusted of 1.11. |

Anode = Left PFC (~FC3; crossing point between T3-Fz and F7-Cz) Cathode = Right supraorbital region |

Accuracy: offline verbal fluency measure |

Anode measure = 18.93 Anode SD = 3.24 Sham measure = 15.38 Sham SD = 2.89 SMD = 1.16 SMDadjusted = 1.11 |

Citation #45 in Horvath et al. [17] Horvath and colleagues counted the letter and the semantic verbal fluency measures separately (i.e., as independent data sets) in the same analysis, yielding two SMDs (0.63 and 1.00). Since the data came from the same experiment and subjects, we used the average performance on the two verbal fluency tasks provided in the paper. |

|

Vannorsdall et al.

2012 [40] |

Vannorsdall and colleagues examined the effects of tDCS on verbal fluency (online). The authors reported the online effects of the semantic verbal fluency task, and this yields an SMDadjusted of 0.47. |

Anode = Left PFC (F3) Cathode = Cz (vertex) |

Accuracy: online verbal fluency measure |

Anode measure = 25.9 Anode SD = 6.2 Sham measure = 23 Sham SD = 5.6 SMD = 0.49 SMDadjusted = 0.47 |

Citation #48 in Horvath et al. [17] Same as reported by Horvath and colleagues |

|

Meinzer et al.

2012 [41] |

Meinzer and colleagues examined the effects of tDCS on semantic verbal fluency. The task was collected during stimulation (i.e., online), and this yields an SMDadjusted of 0.72. |

Anode = Left PFC (placed between F5 and FC5) Cathode = Right supraorbital region |

Accuracy: online verbal fluency measure |

Anode measure = 55.7 Anode SD = 2.9 Sham measure = 53.3 Sham SD = 3.6 SMD = 0.73 SMDadjusted = 0.72 |

Citation #51 in Horvath et al. [17] Same as reported by Horvath and colleagues |

Because tDCS is a relatively recent technique, it is difficult to find a large number of studies using the same electrode montages, tasks, and stimuli. However small sample sizes in meta-analyses severely limit the power and reliability of summary statistics. To address this, we structured the meta-analysis to first perform a large-sample main analysis across the data from all of the language papers, followed by smaller sub-analyses that aimed to address more specific questions about particular tasks and stimulation protocols.

We examined eleven language experiments from nine manuscripts that reported the effects of anodal stimulation relative to sham stimulation [35-43] (two manuscripts reported two separate experiments on independent groups of subjects). The manuscripts were read in detail by two independent reviewers, and the data for the mean and variance for each behavioral measure were recorded from each experiment. In some cases, the mean and/or variance were not reported in the manuscript but included as images in the figures of the manuscripts. In these cases, the images were exported and the size of each measure and/or error bar was assessed using a metric overlay in Adobe Illustrator. In the analysis performed by Horvath and colleagues [31], there were cases in which multiple measures were selected from a single experiment but counted as independent data in the meta-analysis. This produces dependent data samples (i.e., multiple measures from a single group of subjects), which violates the assumption that the data represent independent experiments. For experiments that reported multiple measures of the same type of task (e.g., two post stimulation measures of verbal fluency, obtained close in time after the offset of stimulation), we used an averaged score of these measures in the meta-analysis, rather than counting each measure as an independent data set. For studies that reported the effects of multiple montages, the electrode montage that was the most consistent with the other studies in the analysis was selected. The data were labeled according to whether the effect represented a measure taken during stimulation (i.e., online) or after the end of stimulation (i.e., offline).

Using the data from each paper, we calculated standardized mean difference (SMD) effect sizes as follows [44, 45]:

X1: mean of behavioral measurement from the anode condition

X2: mean of behavioral measurement from the sham condition

SDpooled: pooled standard deviation from both the anode and sham conditions

A common rule of thumb for interpreting SMD effect sizes is that a value of ~0.2 indicates a small effect, a value of ~0.5 indicates a medium effect and a value of ~0.8 or higher indicates a large effect [46].

Many published tDCS studies include small sample sizes (as low as 10 subjects in the studies examined here). Small sample sizes can produce a positive bias in meta-analyses. We therefore performed a correction to adjust for small sample sizes [45]. This provides a more conservative estimate of the effect size for each experiment (i.e., results in a slight reduction of SMD). The correction was performed using the formula:

Where Γ is the gamma function

n1 is sample size for anodal group

n2 is sample size for sham group

SMDadjusted = the standardized mean difference corrected for small sample size, also referred to as Hedge’s g

For one experiment [35], the t-statistic was provided without the individual condition means and standard deviations. Using the t-statistic, the standardized mean difference could be calculated with the following relationship:

n1 is sample size for anodal group

n2 is sample size for sham group

t is t-statistic

Meta-analysis

There were two levels to this meta-analysis. The first level of analyses examined all language studies with comparable behavioral measures (e.g., accuracy). The objective was to identify whether single-session tDCS has a general effect on language-related behaviors. This approach benefited from having a larger number of studies [47, 48], but provided less specificity with respect to the type of behavior examined. The second set of meta-analyses aimed to identify more specific effects from tDCS. This approach had lower power but had the benefit that it included specificity with regard to the type of language task performed and the location of electrode placement.

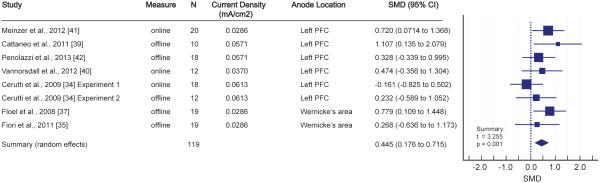

We applied random-effects models in the analyses where the studies varied in the type of task (e.g., verbal fluency or novel language learning) and the type of electrode montage (e.g., anode located at left PFC or anode located at Wernicke’s area), since this assumed inhomogeneity across studies (Figure 1 and 2) [44, 45]. We applied fixed-effects models in the analyses where the studies used the same task and location of anode (e.g., all verbal fluency, offline measures, with anode at left PFC), since this assumed homogeneity (Figure 3 and 4) [44, 45].

Figure 1.

Results of main meta-analysis examining the effects of single-session tDCS on accuracy measures across all the language studies. Left: Properties of individual studies, including standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. Right: Forest plot for the main meta-analysis.

Figure 2.

Results of sub-analysis examining effects of single-session tDCS on accuracy measures obtained after the end of stimulation. Left: Properties of individual studies, including standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. Right: Forest plot for the sub-analysis of offline studies.

Figure 3.

Results of sub-analysis examining effects of single-session tDCS on accuracy measures of verbal fluency obtained after the end of stimulation . Left: Properties of individual studies, including standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. Right: Forest plot for the sub-analysis of offline verbal fluency studies.

Figure 4.

Results of sub-analysis examining effects of single-session tDCS on accuracy measures of verbal fluency obtained during stimulation. Left: Properties of individual studies, including standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. Right: Forest plot for the sub-analysis of online studies.

There were accuracy measures from language tasks in eight of the eleven experiments (including both offline and online measures). There was one analysis in the language section from Horvath and colleagues that analyzed reaction time measures in a picture-naming task across two experiments [37, 39]. Since there were only two studies in this analysis, we did not perform analyses examining the effects on reaction time measures and thus our analyses are limited to examining the effects on accuracy measures. We note though that including the reaction time data in the main analysis (after sign-flipping to align the hypothesized direction of results for reaction time and accuracy) did not substantively alter the summary effect of the main analysis (see Results below). We also note that the same results were yielded for each model when the statistical analyses were performed using software from MedCalc version 15.2.

Results

The effects of single-session tDCS on accuracy measures across the language studies

We first conducted the main meta-analysis across the accuracy measures in the language studies (outlined in Table 1) in order to test for any effect of tDCS across the experiments. This approach generalized across behavioral measures for verbal fluency and novel word learning, and included both online and offline measures. This analysis revealed a significant effect from single-session tDCS on accuracy measures in language (t=3.255, p=0.002; Figure 1). As noted in the Methods section, this analysis did not include studies that employed reaction time measures. Inclusion of these studies, however, did not alter the significance of the main analysis (t=3.249, p<0.001).

The effects of single-session tDCS on accuracy measures obtained after the end of stimulation

Next, we performed a number of sub-analyses in order to examine more specific effects from single-session tDCS. First, we examined whether there was a significant effect on the accuracy measures restricted to those collected after the end of stimulation (i.e., offline). We found a significant effect of tDCS across the four experiments that reported offline accuracy measures, including accuracy measures from verbal fluency and novel word learning (t =3.101, p=0.002; Figure 2).

The analysis of offline accuracy measures from Figure 2 included measures from two different types of tasks (i.e., verbal fluency and novel word learning) and anode locations (i.e., left PFC and Wernicke’s area). Next, we examined task-specific effects from offline measures, and separated the data for the two tasks. This resulted in a sub-analysis across three experiments that showed a significant effect of anodal tDCS on offline accuracy measures of verbal fluency with an anode location of left PFC (t=2.150, p=0.035; Figure 3). There was only one experiment with an offline accuracy measure from novel word learning, and therefore no sub-analysis could be performed for this task.

The effects of single-session tDCS on accuracy measures obtained during stimulation

To examine the effects of tDCS on accuracy measures obtained during stimulation, we performed an analysis across the three experiments that provided online measures of accuracy in the language studies. These measures were obtained from the same tasks (i.e., verbal fluency) with the same anode placement (i.e., left PFC). This analysis showed a non-significant effect (t=1.680, p=0.096; Figure 4), with the effect trending in the hypothesized direction. Note: The online measurements reported in these experiments were collected at different time points during stimulation. The reported measurements ranged from data collection that started 6 minutes after the onset of anodal stimulation up to 24 minutes after the onset of stimulation. Additionally, one of the studies used behavioral training coupled with stimulation, while the other two studies did not.

Discussion

Here, we report a series of meta-analyses that provide a quantitative examination of the effects of single-session tDCS on cognitive processes in language. The main analysis found that across a broad range of language studies, anodal tDCS produced reliable effects on behavior in healthy adults. There were also a number of significant effects from tDCS when the studies were further divided into sub-analyses examining specific tasks (e.g., verbal fluency), electrode montages (e.g., left PFC), and stimulation protocols (e.g., offline). The only non-significant sub-analysis was for behavioral measures obtained during stimulation (i.e., online). Previous work has suggested that the size of the effect from tDCS is influenced by the duration and intensity of stimulation [1, 2, 22, 23], as well as whether or not stimulation is coupled with behavioral training [24, 49]. The online measures in these studies were obtained after a variable duration of stimulation, and differed in whether or not the stimulation was coupled with cognitive training beforehand. Therefore, it is difficult to determine whether the online effects were only trending due to the duration of stimulation, differences in cognitive training, or because the measures were collected during stimulation. It will be of important in future meta-analytic work to examine cognitive differences between these factors as more studies become available for examining these differences.

Comparing Meta-Analyses of tDCS Studies of Language

There are two main factors that led to the substantial difference in findings between this meta-analysis and the meta-analysis performed by Horvath and colleagues. The first factor relates to the method of data selection from the individual papers. This is reviewed in Table 1, and demonstrates that in many studies the data selection differed considerably. Differences at the level of each individual study can lead to substantially different final outcomes. Indeed these differences were sufficient to alter the outcomes in the sub-analyses. For example, the sub-analysis in Figure 4 is the same sub-analysis Horvath and colleagues performed (i.e., all verbal fluency measures obtained offline), but selecting data consistently across the studies and counting each experiment once. This led to a significant, rather than null, outcome.

The second factor contributing to the major differences between our findings and those reported by Horvath and colleagues relates to the manner in which individual studies were grouped for the meta-analysis. Horvath and colleagues chose to examine subgroups of specific behaviors in language that often involved sample sizes of only two or three studies. They never performed an analysis that collapsed across a large group of studies, as in Figure 1. It is difficult to make strong claims from null results when there are very few studies available for each analysis. Here, we attempt to address this by first performing a larger meta-analysis across all studies from the language section that contain the same type of behavioral outcome measure (i.e., accuracy). Indeed when the criteria were loosened and a larger-scale analysis was performed across the language studies, it revealed a reliable effect of tDCS on this cognitive domain.

Future Directions and Limitations

The meta-analyses employed in this study are limited to analyzing the data from language studies and they do not include data from outside of this cognitive domain (e.g., studies of memory or executive function). It will be useful for future work to evaluate whether there are reliable effects from tDCS in the other cognitive domains.

The data from the language section are limited to comparisons of anodal and sham stimulation conditions in the language tasks. Because of this, we are not able to draw conclusions about polarity-specific modulations of tDCS on behavior from this meta-analysis. Further work is needed to determine whether there are dissociable effects across studies between cathodal and sham montages, and between cathodal and anodal montages.

Additionally, this meta-analysis was unable to divide studies based on the type of cognitive training that occurred during the application of tDCS due to the small sample sizes available. For example, it may be the case that there are methods by which stronger effects can be achieved by coupling stimulation with cognitive training during stimulation [24, 25, 27, 50-52]. These differences in paradigmatic approach may make a significant difference in the size of the effects that can be achieved using tDCS.

At present, there is a lack of comparable studies available in the literature. There are few studies that examine the same task using similar stimuli and the same electrode montage. This is to be expected given that tDCS is a fairly new technique. However, this means that if a meta-analysis is overly restricted (i.e., only examines specific tasks, with the same montages, and specific categories of stimuli) then it leads to analyses that are severely underpowered and results that are less reliable (i.e., only two studies per analysis). It may benefit future meta-analyses in the tDCS literature to begin by examining more general effects across a large number of studies, and to then subsequently perform sub-analyses depending on whether there are enough published studies in the literature that are directly comparable.

Conclusions and Broader Implications

The results from these meta-analyses support the conclusion that the effects seen from anodal tDCS on behavior are not artifacts with a net zero outcome. These behavioral findings are consistent with the observed effects from tDCS on neurophysiology in animals and humans. Given the growing use of this technique in basic research and clinical trials, these results provide important insights into whether tDCS can be effectively used to alter cognition. In light of these findings, it will be of great interest to future research to characterize the stimulation parameters that drive variability in the effects from tDCS across individuals (e.g., genetics, state-dependent interactions, type and duration of stimulation).

Research using tDCS has already provided important insights into the neurobiology of certain cognitive processes. Future tDCS research that integrates behavioral measurements with simultaneous measurements from other methodologies will provide valuable converging evidence for basic research and clinical applications of tDCS, including the effect of tDCS on brain oscillations, neurotransmitter release, and functional connectivity.

Highlights.

The effects of tDCS are complex, and the extent to which stimulation reliably influences different cognitive domains has been debated.

We performed a meta-analysis of 9 studies of single-session tDCS in healthy adults that included behavioral measures from language tasks.

There was a significant effect from anodal single-session tDCS in healthy adults compared to sham. Behavioral effects of tDCS were more robust for measures obtained after a full session of tDCS (e.g. off-line stimulation).

These results indicate that single-session tDCS produces a significant and reliable effect on language measures in healthy adults.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health (AG017586 and 5T32AG000255). The authors wish to acknowledge fellow members of the Laboratory for Cognition and Neural Stimulation (LCNS) at the University of Pennsylvania for assisting with close reading and evaluation of the manuscript by Horvath and colleagues [31]. We also thank Dr. Barbara Penolazzi for additional help with data from the Penolazzi et al. (2013) [43] manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nitsche MA, Paulus W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J Physiol. 2000;527(Pt 3):633–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nitsche MA, Paulus W. Sustained excitability elevations induced by transcranial DC motor cortex stimulation in humans. Neurology. 2001;57(10):1899–901. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.10.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuo MF, Nitsche MA. Exploring prefrontal cortex functions in healthy humans by transcranial electrical stimulation. Neurosci Bull. 2015;31(2):198–206. doi: 10.1007/s12264-014-1501-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priori A, Berardelli A, Rona S, Accornero N, Manfredi M. Polarization of the human motor cortex through the scalp. Neuroreport. 1998;9(10):2257–60. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199807130-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filmer HL, Dux PE, Mattingley JB. Applications of transcranial direct current stimulation for understanding brain function. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37(12):742–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chrysikou EG, Hamilton RH, Coslett HB, Datta A, Bikson M, Thompson-Schill SL. Noninvasive transcranial direct current stimulation over the left prefrontal cortex facilitates cognitive flexibility in tool use. Cogn Neurosci. 2013;4(2):81–9. doi: 10.1080/17588928.2013.768221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turkeltaub PE, Benson J, Hamilton RH, Datta A, Bikson M, Coslett HB. Left lateralizing transcranial direct current stimulation improves reading efficiency. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(3):201–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiener M, Hamilton R, Turkeltaub P, Matell MS, Coslett HB. Fast forward: supramarginal gyrus stimulation alters time measurement. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010;22(1):23–31. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunoni AR, Nitsche MA, Bolognini N, Bikson M, Wagner T, Merabet L, et al. Clinical research with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS): challenges and future directions. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(3):175–95. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotelli M, Manenti R, Petesi M, Brambilla M, Cosseddu M, Zanetti O, et al. Treatment of primary progressive aphasias by transcranial direct current stimulation combined with language training. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;39(4):799–808. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Wu D, Chen Y, Yuan Y, Zhang M. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on language improvement and cortical activation in nonfluent variant primary progressive aphasia. Neurosci Lett. 2013;549:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandiga PC, Hummel FC, Cohen LG. Transcranial DC stimulation (tDCS): a tool for double-blind sham-controlled clinical studies in brain stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(4):845–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nardone R, Holler Y, Tezzon F, Christova M, Schwenker K, Golaszewski S, et al. Neurostimulation in Alzheimer's disease: from basic research to clinical applications. Neurol Sci. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10072-015-2120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah PP, Szaflarski JP, Allendorfer J, Hamilton RH. Induction of neuroplasticity and recovery in post-stroke aphasia by non-invasive brain stimulation. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:888. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.San-Juan D, Morales-Quezada L, Orozco Garduno AJ, Alonso-Vanegas M, Gonzalez-Aragon MF, Espinoza Lopez DA, et al. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in Epilepsy. Brain Stimul. 2015;8(3):455–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purpura DP, McMurtry JG. Intracellular Activities and Evoked Potential Changes during Polarization of Motor Cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1965;28:166–85. doi: 10.1152/jn.1965.28.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bindman LJ, Lippold OC, Redfearn JW. The Action of Brief Polarizing Currents on the Cerebral Cortex of the Rat (1) during Current Flow and (2) in the Production of Long-Lasting after-Effects. J Physiol. 1964;172:369–82. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nitsche MA, Doemkes S, Karakose T, Antal A, Liebetanz D, Lang N, et al. Shaping the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation of the human motor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97(4):3109–17. doi: 10.1152/jn.01312.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pellicciari MC, Brignani D, Miniussi C. Excitability modulation of the motor system induced by transcranial direct current stimulation: a multimodal approach. Neuroimage. 2013;83:569–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antal A, Kincses TZ, Nitsche MA, Bartfai O, Paulus W. Excitability changes induced in the human primary visual cortex by transcranial direct current stimulation: direct electrophysiological evidence. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(2):702–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antal A, Kincses TZ, Nitsche MA, Paulus W. Manipulation of phosphene thresholds by transcranial direct current stimulation in man. Exp Brain Res. 2003;150(3):375–8. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1459-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batsikadze G, Moliadze V, Paulus W, Kuo MF, Nitsche MA. Partially non-linear stimulation intensity-dependent effects of direct current stimulation on motor cortex excitability in humans. J Physiol. 2013;591:1987–2000. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.249730. Pt 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo HI, Bikson M, Datta A, Minhas P, Paulus W, Kuo MF, et al. Comparing cortical plasticity induced by conventional and high-definition 4 × 1 ring tDCS: a neurophysiological study. Brain Stimul. 2013;6(4):644–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gill J, Shah-Basak PP, Hamilton R. It's the thought that counts: examining the task-dependent effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on executive function. Brain Stimul. 2015;8(2):253–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antal A, Terney D, Poreisz C, Paulus W. Towards unravelling task-related modulations of neuroplastic changes induced in the human motor cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26(9):2687–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobson L, Koslowsky M, Lavidor M. tDCS polarity effects in motor and cognitive domains: a meta-analytical review. Exp Brain Res. 2012;216(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2891-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stagg CJ, Jayaram G, Pastor D, Kincses ZT, Matthews PM, Johansen-Berg H. Polarity and timing-dependent effects of transcranial direct current stimulation in explicit motor learning. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(5):800–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batsikadze G, Paulus W, Grundey J, Kuo MF, Nitsche MA. Effect of the Nicotinic alpha4beta2-receptor Partial Agonist Varenicline on Non-invasive Brain Stimulation-Induced Neuroplasticity in the Human Motor Cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2014 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Batsikadze G, Paulus W, Kuo MF, Nitsche MA. Effect of serotonin on paired associative stimulation-induced plasticity in the human motor cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(11):2260–7. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunoni AR, Kemp AH, Shiozawa P, Cordeiro Q, Valiengo LC, Goulart AC, et al. Impact of 5-HTTLPR and BDNF polymorphisms on response to sertraline versus transcranial direct current stimulation: implications for the serotonergic system. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(11):1530–40. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horvath JC, Forte JD, Carter O. Quantitative Review Finds No Evidence of Cognitive Effects in Healthy Populations From Single-session Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) Brain Stimul. 2015;8(3):535–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.01.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price AR, Hamilton RH. A Re-evaluation of the Cognitive Effects From Single-session Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2015;8(3):663–5. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nitsche MA, Bikson M, Bestmann S. On the Use of Meta-analysis in Neuromodulatory Non-invasive Brain Stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2015;8(3):666–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chhatbar PY, Feng W. Data Synthesis in Meta-Analysis may Conclude Differently on Cognitive Effect from Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation. Brain Stimul. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.06.001. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cerruti C, Schlaug G. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of the prefrontal cortex enhances complex verbal associative thought. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21(10):1980–7. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.21143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiori V, Coccia M, Marinelli CV, Vecchi V, Bonifazi S, Ceravolo MG, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation improves word retrieval in healthy and nonfluent aphasic subjects. J Cogn Neurosci. 2011;23(9):2309–23. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wirth M, Rahman RA, Kuenecke J, Koenig T, Horn H, Sommer W, et al. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on behaviour and electrophysiology of language production. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(14):3989–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Floel A, Rosser N, Michka O, Knecht S, Breitenstein C. Noninvasive brain stimulation improves language learning. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008;20(8):1415–22. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fertonani A, Rosini S, Cotelli M, Rossini PM, Miniussi C. Naming facilitation induced by transcranial direct current stimulation. Behav Brain Res. 2010;208(2):311–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cattaneo Z, Pisoni A, Papagno C. Transcranial direct current stimulation over Broca's region improves phonemic and semantic fluency in healthy individuals. Neuroscience. 2011;183:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vannorsdall TD, Schretlen DJ, Andrejczuk M, Ledoux K, Bosley LV, Weaver JR, et al. Altering automatic verbal processes with transcranial direct current stimulation. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:73. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meinzer M, Antonenko D, Lindenberg R, Hetzer S, Ulm L, Avirame K, et al. Electrical brain stimulation improves cognitive performance by modulating functional connectivity and task-specific activation. J Neurosci. 2012;32(5):1859–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4812-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penolazzi B, Pastore M, Mondini S. Electrode montage dependent effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on semantic fluency. Behav Brain Res. 2013;248:129–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borenstein M. Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, U.K.: 2009. pp. xxviii–421. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic Press; Orlando: 1985. pp. xxii–369. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd L. Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, N.J.: 1988. pp. xxi–567. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Collaboration . Cochrane book series. Wiley-Blackwell; Chichester, England ; Hoboken, NJ: 2008. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions; pp. xxi–649. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fu R, Gartlehner G, Grant M, Shamliyan T, Sedrakyan A, Wilt TJ, et al. Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(11):1187–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andrews SC, Hoy KE, Enticott PG, Daskalakis ZJ, Fitzgerald PB. Improving working memory: the effect of combining cognitive activity and anodal transcranial direct current stimulation to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Brain Stimul. 2011;4(2):84–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karok S, Witney AG. Enhanced motor learning following task-concurrent dual transcranial direct current stimulation. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e85693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bortoletto M, Pellicciari MC, Rodella C, Miniussi C. The interaction with task-induced activity is more important than polarization: a tDCS study. Brain Stimul. 2015;8(2):269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reis J, Schambra HM, Cohen LG, Buch ER, Fritsch B, Zarahn E, et al. Noninvasive cortical stimulation enhances motor skill acquisition over multiple days through an effect on consolidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(5):1590–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805413106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]