Abstract

Background

Understanding the mental health burdens faced by people living with HIV in China is instrumental in the development of successful targeted programs for psychological support and care.

Methods

Using multiple Chinese and English literature databases, we conducted a systematic review of observational research (cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort) published between 1998 and 2014 on the mental health of people living with HIV in China.

Results

We identified a total of 94 eligible articles. A broad range of instruments were used across studies. Depression was the most widely studied problem; the majority of studies reported prevalence greater than 60% across research settings, with indications of a higher prevalence among women than men. Rates of anxiety tended to be greater than 40%. Findings regarding the rates of suicidality, HIV-related neurocognitive disorders, and substance use were less and varied. Only one study investigated posttraumatic stress disorder and reported a prevalence of 46.2%. Conflicting results about health and treatment related factors of mental health were found across studies.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, this review confirmed that people living with HIV are vulnerable to mental health problems, and there is substantial need for mental health services among this population.

Introduction

Although the nationwide HIV prevalence remains low in China, the number of people living with HIV, as well as the number of new infections per year, continues to increase [1]. At the end of October 2014, over 0.49 million people were living with HIV in China based on the China information system for disease control and prevention, of which 40% were AIDS patients [2]. Case reporting data shows that from 2011 to 2014, the number of newly diagnosed increased each year, with the figures for each year standing at 20,450, 41,929, 42,286, and 45,145, respectively [3,4]. The healthcare and management of such a vast number of people living with HIV is a realistic challenge for Chinese health service providers and policy makers, particularly because this number continues to grow.

Mental health in relation to people living with HIV is becoming an increasing concern worldwide; however, to date this pressing issue has been largely ignored in global policy guidelines [5]. Since 2003, under the “Four Frees, One Care” policy, it has become easier for people living with HIV in China to access HIV-related health care [6], but their psychiatric and psychological needs are yet seldom touched [7]. HIV infection is regarded as a traumatic and stressful experience that can negatively affect mental health status and potentially lead patients into a cycle of physical and mental decline [8]. Studies have shown that people living with HIV are more likely than the general population to exhibit mental health problems including depression, anxiety, and suicidality, as well as the harmful use of substances [8–11]. The chronic effects of HIV and antiretroviral therapy (ART) on the brain can also result in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) [12]. Poor mental health status can serve as a barrier to adequate ART adherence, and consequently decrease quality of life and increase mortality [8–10]. Policies and programs designed to decrease the mental health burdens of people living with HIV are urgently needed, and appropriate response hinges on systematic information about mental health status.

In this systematic review, we integrated data on the mental health problems of Chinese people living with HIV from articles published from 1998 to 2014. We sought to accomplish four aims. First, we reviewed articles for evidence of disparities in mental health morbidity affecting people living with HIV. Second, we identified the health and treatment related correlates of mental health in this population. Third, we identified some of the methodological issues that currently influence our understanding of mental health morbidity concerns among this population. Finally, we provided our thoughts on important future directions for research on the mental health of people living with HIV in China.

Methods

Search strategy

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA guideline [13,14]. We systematically searched the following databases: (1) international databases including MEDLINE, PsychINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science; and (2) Chinese scientific databases including China National Knowledge Infrastructure Project (CNKI), China Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), and Digital Journal of Wan fang Data (Wan fang).

We conducted our search by combining keywords from the following concepts:

The population: HIV, AIDS;

The outcome: mental health, psychology, depression, anxiety, substance use, alcohol use, drug use, smoking behavior, suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder, and neuropsychology;

The study location: China.

The full search strategy with adapted terms for each database is included in S1 File.

Eligibility criteria

We reviewed abstracts and full texts of retrieved articles according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) studies conducted in mainland China or Hong Kong with people living with HIV; (2) written in English or Chinese; (3) an observational design (cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort); and (4) contains quantitative data on mental health (prevalence, or scores of instruments).

Articles were excluded if they were qualitative studies, literature reviews, conference abstracts, pharmacological studies, or intervention evaluations. In terms of duplicated data, the one with the maximum sample size and the most comprehensive results was included.

Data

We extracted data on study population (age and gender distribution, HIV-related clinical information), study site, study design, sampling method, instruments, prevalence of mental health problems, and the health and treatment-related correlates.

Because we focused on sample characteristics and prevalence of mental health problems for this review, a four-item appraisal checklist adapted from the scoring systems developed by Loney et al [15] and Kim et al [16] was used for each article. The checklist evaluated sample size (≥ 300 vs. < 300), sampling method (random vs. convenient), participation rate (reported vs. unreported or < 70%), and eligibility criteria (provided vs. not provided). Total scores ranged from 0 to 4, with a lower number indicating lower quality and a higher risk of bias.

Results

Search and study selection

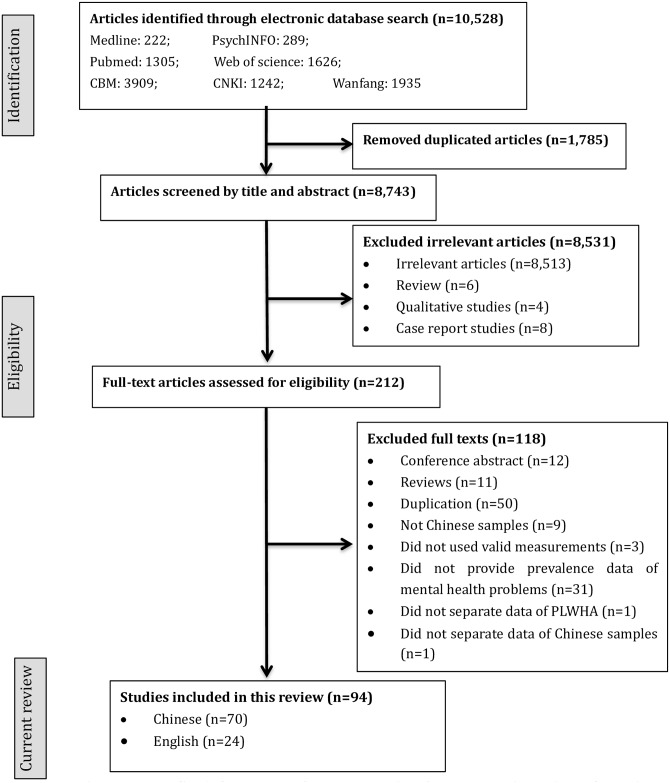

Our electronic search yielded 10,528 articles: 1,784 duplicate articles were retrieved from more than one database and 8,532 irrelevant articles were excluded. We assessed 212 full-text articles for eligibility. Ninety-one studies reported in 94 articles (70 Chinese and 24 English articles published between 2004 and 2014) were included in this systematic review, because one study reported findings across two articles [17,18] and another across three articles [19–21]. Fig 1 presents the flowchart of our study selection and the frequency of reasons for exclusion.

Fig 1. PRISMA flowchart of study selection for systematic review of published research on prevalence of mental health problems among people living with HIV.

Characteristics of studies

Seventy-six out of 91 studies provided province-specific data; seven were conducted in multiple provinces and five did not report the study region. One third (n = 31) of the studies did not specify participants’ stage of illness or the time since being diagnosed HIV-positive. Several studies focused on specific sub-populations. All community-based studies sourced participants from rural areas [19–33] predominantly in central China where most participants were former blood/plasma donors [19–27]. There were also three other studies about people with combined HIV and tuberculosis (HIV/TB) [34–36], three about people who injected drugs [35,37,38], three about pregnant women [31,39,40], and three about men who have sex with men [41–43].

Regarding the risk of bias of individual studies, over half of the studies (54.9%, 50/91) had a score of 0 or 1, which indicates a high risk of bias. Sample sizes ranged from 16 to 1,064, and 74 studies (81.3%) were with a sample size less than 300. Forty-one studies (45.1%) did not provide eligibility criteria, and 53 (58.2%) did not report participation rate. The most common limitation observed was risk of bias attributable to convenience sampling (29.7%, 27/91), while 35 studies (38.5%) did not specify their sampling method (Table 1). Only 15 studies used random sampling, and 22 included HIV-negative comparison groups. The overview of studies is provided in S1 Table.

Table 1. Characteristics of reviewed articles.

| Studies, No. | %(N = 91) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-population | ||

| Former blood/plasma donors | 9 | 9.9 |

| HIV/TB | 3 | 3.3 |

| Injected drug users | 3 | 3.3 |

| Pregnant women | 3 | 3.3 |

| Men who have sex with man | 3 | 3.3 |

| Unspecific | 70 | 76.9 |

| Study type | ||

| Cross-sectional | 65 | 71.4 |

| Case-control | 22 | 24.1 |

| Cohort | 2 | 2.2 |

| Other | 3 | 3.3 |

| Sample method | ||

| Convenience | 27 | 29.7 |

| Random | 17 | 18.7 |

| Complete | 9 | 9.9 |

| Other | 6 | 6.6 |

| Not available | 32 | 35.1 |

| Sample sizea | ||

| ≤50 | 11 | 12.1 |

| 51–100 | 21 | 23.1 |

| 101–200 | 27 | 29.6 |

| 201–300 | 16 | 17.6 |

| >300 | 16 | 17.6 |

| Research topic | ||

| Depression | 78 | 85.7 |

| Anxiety | 64 | 70.3 |

| Suicide | 11 | 12.1 |

| PTSDb | 1 | 1.1 |

| HANDc | 9 | 9.9 |

| Substance use | 18 | 19.8 |

aSample size of people living with HIV

bPost-traumatic stress disorders

cHIV-associated neurocognitive disorders

Mental health problems

Depression

Three studies reported rates of clinical disorder by using diagnostic interviews, i.e., the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, Chinese version) [21,38] and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P, Chinese version) [44], among different samples from different settings. In a CDC-based study, Ren and colleagues [44] found 22.8% had lifetime major depressive disorder in a cross-sectional convenience sample of 342 adults who were HIV-positive in Guangdong (14.8% female; 79.5% were drug users). In their community-based study with a convenience sample of 203 rural HIV-positive former plasma donors (39% female), Atkinson and colleagues [21] found 14% had lifetime major depressive disorder and 2.0% had a current major depressive episode. Participants that were HIV-positive were more likely to experience lifetime major depressive disorder than HIV-negative controls (5%). Jin et al. [38] found that 6.4% of a convenience sample of 204 HIV-positive persons who used heroin in methadone clinics (34.2% female) had experienced major depression in their lifetime, while 1.0% were having a current major depressive episode. The rates did not differ meaningfully between the HIV-positive and HIV-negative people who used drugs in treatment. Compared with the control group who were HIV-negative and did not use drugs (1.5%), the rate of lifetime major depression in people who used heroin was significantly higher.

In addition, 78 studies assessed depressive symptoms using a broad range of instruments (Chinese versions): 27 studies used the Symptom Check List-90 (SCL-90) [23,26,33,34,36,40,45–65]; 26 used the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) [17,18,29–32,34,35,51,57,63,65–80]; seven used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [19–21,25,38,81–84]; six used the Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [85–90]; three used the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) [37,47,91,92]; three used the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) [22,24,41]; three used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [91,93,94]; two used the Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ-9) [95,96]; and one used the Irritability, Depression and Anxiety Scale (IDA) [97].

The median prevalence of depressive symptoms among people living with HIV was 60.64%, with a range of 16% to 100%. Twelve studies compared the prevalence of depression among men and women, and women (36.6%–94.5%) were more likely to report depression than men (37.9%–71.8%) [22,46,48,50,56,67,70,75,79,82,90,94]. In addition, seventeen studies documented higher prevalence of depression and more severe depressive symptoms among persons who were HIV-positive when compared to HIV-negative controls [24,26,30,34,36,40,45,48,52,55,56,59,66,76,92,93,97].

Anxiety

Only one study presented prevalence of clinical diagnosis, which was a CDC-based study conducted in Guangdong province. Using the SCID-I/P, it was found that 15.8% of the participants met the criteria for lifetime general anxiety disorder [44].

However, anxiety symptoms were prevalent in a number of studies. Sixty-four studies assessed anxiety symptoms mainly though measurement instruments (Chinese versions): 27 studies used the SCL-90 [23,26,33,34,36,40,45–65]; 26 used the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) [25,29–31,35,42,51,57,63,65–68,70,71,74,76,78,80,86,90,98–102]; three used the DASS [22,24,41]; three used the HADS [91,93,94]; two used the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) [47,92]; two used the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) [95,96]; and one used the IDA scale [97].

The prevalence of anxiety symptoms ranged from 11.11% to 97.53%, and the median prevalence was 43.13%. Eight studies reported that women (47%–80%) were also more likely to report anxiety than men (41.3%–58.6%)[46,48,50,56,70,90,94,102]. Additionally, seventeen studies compared prevalence of anxiety between people living with HIV and HIV-negative controls, which showed that people living with HIV were more likely to experience anxiety and have more severe anxiety than people who were HIV-negative [24,26,30,34,36,40,45,48,52,55,56,59,76,92,93,97,98].

Suicidal behavior

Two studies reported death records due to suicide [103,104]. Qu and colleagues [103] reviewed medical records from Beijing Di Tan Hospital (1991–2003) and found that among 848 HIV-positive patients, nineteen (2.2%) died from suicide (5 females) and four had made suicide attempts (1 female). Seventeen patients were farmers and nine died by poison. Lai et al. [104] collected data from the DataFax Antiretroviral Therapy Information System in China between July 2003 and September 2009. There were 766 people living with HIV who started ART before October 2008 in Sichuan province, and three died from suicide among 144 death records (2.1%) [104].

Nine studies examined suicidal behavior (suicidal ideation, plan, and attempt), but definitions were highly variable and most failed to present gender-disaggregated data (Table 2). Several studies investigated suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in participants’ lifetimes [28,44], in the past year [22,27,44], in the past six months [26], or since HIV diagnosis [41], by asking simple questions like “Have you thought about suicide/attempted suicide?” One study measured suicidal ideation by using the Self-Rating Idea of Suicide Scale (SIOSS), in which a high score indicates a high level of suicidal ideation [18]. Two studies assessed lifetime suicidality and current suicidality by using the CIDI and BDI respectively [21,38].

Table 2. Summary findings of suicide behaviors.

| Form of suicidality | Measures | First author, year | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed suicide | Death records | Qu, 2005 | 19/848 (2.2%) |

| Lai, 2011 | 3/766 (2.1%) | ||

| Suicide attempts | Medical records | Qu, 2005 | 4/848 (0.5%) |

| Single item | Lv, 2007 | 5.9% (past 1 year) | |

| Lau, 2010 | 8% (past 1 year) | ||

| Wu, 2014 | 2.67% (since HIV diagnosis) | ||

| Questionnaire | Wu, 2007 | 6.9% (lifetime; male 6.5%; female 7.1%) | |

| Ren, 2009 | 37.7% in lifetime; 29.5% in the past year; | ||

| Su, 2010 | 0.7% (past 6 months) | ||

| CIDI (3.0) | Atkinson, 2011 | HIV+: 2%; HIV-: 1% (lifetime) | |

| Suicide ideation | Single item | Lv, 2007 | 32.3% (past 1 year; 58.5% were female) |

| Lau, 2010 | 34.1% (past 1 year) | ||

| Wu, 2014 | 48% (since HIV diagnosis) | ||

| Questionnaire | Wu, 2007 | 34.8% (lifetime; male: 24.7%; female: 23.5%) | |

| Ren, 2009 | 13.7% in lifetime; 3.8% in the past year | ||

| Su, 2010 | 5.9% (past 6 months) | ||

| SIOSS | Qin, 2014 | 29.14% (SIOSS≥12; male: 24.74%; female: 38.30%) | |

| CIDI (3.0) | Atkinson, 2011 | Think a lot about death: HIV+ 16%; HIV- 7%. Think about suicide: HIV+ 11%; HIV- 6%.(in lifetime) | |

| BDI (Item 9) | Atkinson, 2011 | HIV+ 14%; HIV- 12% (past 2 weeks) | |

| Jin, 2013 | HIV+IDU: 37.1%; HIV-IDU: 43.2%; Non-IDU: 8.5% (past 2 weeks) | ||

| Suicide plan | Questionnaire | Wu, 2007 | 25/178 (14.0%; lifetime) |

| Su, 2010 | 2.6% (past 6 months) | ||

| CIDI (3.0) | Atkinson, 2011 | HIV+ 8%; HIV- 3% (lifetime) |

Notes: CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview; BDI = Beck Depression Inventor; SIOSS = Self-rating Idea of Suicide Scale; Questionnaire = not specified or self-developed instruments.

A few noteworthy findings emerged from these studies about suicidal behavior. The prevalence of suicidal ideation in the past year ranged from 29.5% to 34.1% [22,27,44], and the prevalence of attempted suicide in the past year varied from 3.8% to 8% [22,27,44]. There was no significant gender difference observed [27,44]. Additionally, in one community-based study, twelve rural participants (6.9%) had attempted suicide in their lifetime and mostly after getting an HIV diagnosis (10/12) [28]. In a convenience sample of 225 newly diagnosed men who have sex with men in Chengdu, Wu et al. [41] found almost half (48%) of them reported suicidal ideation and 2.67% had attempted suicide since diagnosis. In case-control studies, people who were HIV-positive appeared to be more likely to report suicidal behaviors than their HIV-negative counterparts [21,26,56].

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

We found only one study that screened PTSD symptoms among people living with HIV in China [105]. This survey was conducted in Hengyang, Hunan in 2013 with information collected from a convenience sample of 264 participants aged 18 to 74. Over half of the participants were in the HIV stage (64.4%) and on ART (66.3%). The Chinese version of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) was used and the prevalence of PTSD was 46.2% (male 39.4%; female 59.6%).

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND)

Wu et al. [69] reviewed clinical records of 36 AIDS patients treated from 1999 to 2003 in two hospitals in Shanghai. There were six patients (16.7%) with confirmed AIDS dementia complex (ADC). The average survival time of these ADC patients since diagnosis was 4.7 months, and the average age at death was 41.8 years [69].

As shown in Table 3, six studies examined neuropsychological (NP) impairment or HAND using a wide range of measurements: four studies cited different NP test batteries [19,20,85,88,106], two studies cited the International HIV Dementia Scale (IHDS) [106,107], and one cited the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [108].

Table 3. Summary findings of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.

| Measurement tool | First author, year | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| Medical records | Wu Y, 2007 | 6/36 (16.7%) with confirmed ADC |

| Neuropsychological test battery | Heaton, 2008; Cysique, 2010 | Baseline: HIV+: 36.8% (HIV-monoinfected: 34.2%; HIV/HCV coinfected: 39.7%); HIV-: 19.3% (HCV-monoinfected: 37.2%; controls: 12.7%); 1-year follow-up (NP decline): HIV+: 27.6%; HIV-: 5%. |

| Wright, 2008 | 4% in Beijing; 23% in Hong Kong | |

| Zhang, 2012 | 50/134 (37.31%) | |

| Dwyer, 2014 | 69.4% | |

| International HIV Dementia Scale (IHDS) | Zhang, 2012 | 52/134 = 38.1% (ANI: 22.4%; MND: 11.9%; HAD: 4.5%) |

| Zhao, 2013 | 37.4(ANI: 18.2%; MND: 10.9%; HAD: 8.3%) | |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | Zhen, 2013 | 52.2% (MoCA≥26) |

| Hong Kong List Learning Test (HKLLT) | Au, 2008 | (Mild memory impairment) Total learning: 18%; 10-min Delay Recall: 28%; 30-min Delay Recall: 29%; Discriminability: 13%. |

Notes: ADC: AIDS dementia complex; NP decline: Neuropsychological decline; ANI: asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment; MND: neurocognitive disorder; HAD: HIV-associated dementia

Among these studies, 4% to 69% of the participants were classified as being neuropsychologically impaired [19,20,85,88,106]. Notably, in a community-based cohort study [19,20], 203 HIV-positive people and 198 HIV-negative controls were selected from a rural county in Central China. At baseline, NP impairment was found in 34.2% of the HIV-monoinfected group and 39.7% of the HIV/HCV co-infected group, compared to 37.2% of the HCV-monoinfected group and 12.7% of the uninfected controls. HIV-positive participants with AIDS were more likely to be impaired (43%) than non-AIDS patients (29%) [19]. Twelve months later, 192 HIV-positive and 101 HIV-negative participants were reassessed, and 27% of HIV-positive individuals developed significant cognitive decline compared with 5% of HIV-negative individuals [20].

In addition, Au et al. [81] assessed memory deficits among 90 HIV-positive individuals in Hong Kong using the Hong Kong List Learning Test, and 13.3% to 28.9% were found to have mild memory impairment in the different functions measured.

Substance use

Findings related to substance use were much more fragmented, and inconsistent measurement made results across studies hard to interpret (Table 4). Only two studies defined alcohol use disorder and other substance use disorders through the CIDI (3.0) [21,56]. Atkinson et al. [21] observed a 14% prevalence of lifetime alcohol use disorder in 203 HIV-positive rural former plasma donors compared to 6% lifetime prevalence in a comparable sample of 198 HIV-negative rural former plasma donors. All diagnoses of a lifetime alcohol use disorder were in men and no other substance use disorder was found. Jin and colleagues [56] found comparable rates of lifetime alcohol use disorder among HIV-positive people who used drugs, HIV-negative people who used drugs, and the control group, which were 15.7%, 19.3%, and 12.4%, respectively. The prevalence of current (last 30 days) alcohol use disorders was 2% in all three groups. In addition, 1% of HIV-positive people who used drugs and 3% of HIV-negative people who used drugs had current heroin use disorders.

Table 4. Summary findings of substance use.

| Form of substance use | Measures | First author, year | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substance use | Questionnaire | Li, 2004 | HIV+: 2.01±1.35; Relatives: 0.62±0.83; Control: 0.67±0.79 (definition unknown) |

| Drug use | CIDI (3.0) | Atkinson, 2011 | None |

| Jin, 2013 | Current heroin use disorders: HIV+IDU: 1.0%; HIV-IDU: 3.0% | ||

| Questionnaire | Fang, 2008 | 4.74% (definition unknown) | |

| Shan, 2009 | 98.4% (lifetime) | ||

| Ren, 2009 | 79.5% (lifetime) | ||

| Greene, 2013 | 16.7% (daily) | ||

| Luo, 2013 | 55.4% (lifetime) | ||

| Wang, 2014 | 23.2% (current heroin use) | ||

| Alcohol use | CIDI (3.0) | Atkinson, 2011 | HIV+: 14%; HIV-: 6% (Lifetime alcohol use disorder, all were male) |

| Jin, 2013 | HIV+IDU: 15.7%; HIV-IDU: 19.3%; non-IDU: 12.4% (Lifetime alcohol use disorder) | ||

| Questionnaire | Wu, 2006 | 10.2% (current use) | |

| Wu, 2007 | 8/175(4.6%, definition unknown) | ||

| Fang, 2007 | 16.8% (definition unknown) | ||

| Su, 2010 | HIV+: 47.7%; HIV-: 54.9% (past month) | ||

| Luo, 2013 | Ever drinkers: 65.1% (male: 89.7%; female: 16.9%). Current drinker (past month): 40.0% (male: 35.9%; female: 7.1%). | ||

| Dwyer, 2014 | 38% (past 6 months; male: 18%; female: 12.5%) | ||

| Xu, 2014 | 79/157 (50.3%, past year) | ||

| Sun, 2014 | 322/772 (41.7%, past month) | ||

| Tobacco use | Questionnaire | Wu, 2006 | 44.1% (current use) |

| Wu, 2007 | 48/175 (27.4%, definition unknown) | ||

| Fang, 2007 | 26.3% (definition unknown) | ||

| Li, 2007 | HIV+: 72.2%; HIV-: 40.4% (definition unknown) | ||

| Su, 2010 | HIV+: 41.2%; HIV-: 26.0% (past month) | ||

| Cheng, 2014 | 15/68(22.1%, smoking history) | ||

| Sun, 2014 | 373/772 (48.3%, "Are you a smoker?") | ||

| Xu, 2014 | 75/157 (47.8%, past year) | ||

| Dwyer, 2014 | 50% (Current smoker; male: 53.8%; female: 25.0%) |

Notes: Questionnaire: not specified or self-developed instruments; CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview

Other studies assessed substance use behavior mostly by self-developed questionnaires. In terms of drug use, three studies reported a range from 55.4% to 98.4% of lifetime drug use [44,109,110]. Greene et al. [37] found that among 96 HIV-positive people who used drugs recruited from a clinic in Yunnan, 16.7% reported injecting drugs daily. Wu et al. [41] found that 23.2% of newly diagnosed men who have sex with men in Chengdu were current heroin users. Finally, Fang et al. [39] conducted a survey among 572 pregnant women in four provinces who were diagnosed between 2004 and 2006 and found that 4.74% used drugs and most shared drug paraphernalia (74%).

As for alcohol use, three studies reported prevalence of alcohol use in the past month, which was from 40.0% to 47.7% [26,90,109]. In a cross-sectional study, 50.3% of HIV-positive men who have sex with men on ART had used alcohol in the last year [43]. After disaggregating findings by gender, males were more likely to report alcohol use than females [21,88,109]. In three case-control studies, people living with HIV reported comparable [26,56] or significantly higher alcohol use rates than control groups [21]. Three other studies did not specify the definition of substance use [28,67,70].

In terms of tobacco use, 41.2% of participants who were HIV-positive reported smoking in the past month, and their smoking frequency and quantity were both higher than the HIV-negative group in a community-based case-control study [26]. In a cross-sectional study, 47.8% of HIV-positive men who have sex with men on ART had smoked in the last year [43]. Several other studies reported smoking behaviors among people living with HIV without specifying definitions [28,42,67,70,88,90,93], and the smoking rates ranged from 22.1% to 50%. Only one study presented data separated by gender, and the researchers found that 53.8% of males and 25% of females were current smokers [88].

The health and treatment-related correlates

Health-related correlates

The findings about the associations between mental health and physical health status, as measured by time since diagnosis, CD4 counts, number of somatic symptoms, and disease courses (AIDS diagnosis), are fragmented as well. Two studies found that people with a higher number of somatic symptoms were more likely to experience depression and anxiety [22,96], while two studies reported no significant association between them [24,91].

Meanwhile, eight studies showed that people living with HIV with lower CD4 (lower than 200) or in the AIDS stage had poorer mental health status [18,19,42,50–52,79,101], including depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and NP impairment, while another six studies reported that there was no association between CD4 count or being diagnosed with AIDS and mental health [19,21,58,67,89,91].

Studies also found that people living with HIV or in treatment for shorter periods were more likely to report poorer mental health status, including PTSD [105], suicidality [44], and self-reported depression [41,79] and anxiety [71]. Although it was a cross-sectional rather than longitudinal study, Ren et al. [44] found that the prevalence of suicide attempts increased along with disease progression. Yet, several studies reported depression [22,77,84,89,91], anxiety [22,91] and suicidal ideation [18,27] did not differ by time since diagnosis.

Treatment-related correlates

Similarly, there were inconsistent results about treatment-related correlates of mental health among people living with HIV in China. Two studies found that people on ART were more likely to report high levels of depression and anxiety [77,93]. One study indicated absence of ART was independently associated with higher depression score [24], whereas four studies suggested that mental health status (depression, anxiety, PTSD, and suicidal ideation) was not associated with ART treatment [18,42,89,105]. In addition, one study reported a negative association between adherence to ART and anxiety and depression [72], while one other study reported a non-significant connection [67].

Discussion

In this review, the available evidence indicates that people living with HIV in China are at risk for mental health problems. Depression and anxiety were the most widely studied and the most common problems, while findings regarding suicidality, substance use, HAND, and PTSD were varied and less prevalent (S2 Table). Notably, most studies were based on a broad range of self-reported scales for psychiatric symptoms, and only three studies employed standardized clinical diagnostic measurements [21,38,44]. Although studies reported a high prevalence of psychiatric symptoms, the reported prevalence of psychiatric disorders was low. There was only around a 2% prevalence rate reported for both current major depressive disorder and substance use disorder [21,38]. Given health care strategies for psychiatric symptoms and psychiatric disorders may differ, we are not sure of the actual needs for different health services among this population. There is also not enough evidence to assist policy makers in making decisions about distribution of resources and cost-effectiveness.

We also found conflicting results regarding health and treatment related correlates of mental health, which may be due to the cross-sectional design of the majority of studies. In order to identify the relationship between disease severity and mental health status, a longitudinal design is needed (such as from HIV-infection diagnosis to AIDS diagnosis). Furthermore, the equivocal findings of our review may be because of the limitation in comparability and generalizability of the current studies. First, as mentioned above, the inconsistency in measurements limits the comparability across studies, especially on substance use and suicidality, of which the definitions were often not specified. Second, not all studies reported the sociodemographic and HIV-related characteristics of participants that may have a significant effect on mental health status. Third, most studies focused on subgroups with differential patterns, such as former blood/plasma donors [19–27], people who injected drugs [35,37,38], pregnant women [31,39,40], and men who have sex with men [41–43], rather than the wider population who are living with HIV in a particular region or the whole country.

According to our assessment criteria on sample size, sampling method, eligibility criteria, and participation rate, the results indicated the included studies were of low quality and had a high risk of bias. Convenience sampling was the most commonly used method, while almost one fourth did not specify the sampling strategy. Additionally, the majority of studies were based on a small sample size. As such, questions can be raised about sample representativeness and generalizability of the findings. Additionally, one-fourth of the studies employed a case-control design, but sometimes the HIV-negative status of the comparison group was self-reported or undetermined. Some studies also failed to present comparable sociodemographic characteristics with the HIV-positive group, which begs the question of whether there was an adequate control group. Further, many studies without a control group preferred to compare the results of people living with HIV with Chinese norms for the general population, especially those using the SCL-90. However, the most commonly used norm for the SCL-90 was based on a study conducted in 1986 [111], which may fail to serve as a good comparison because the psychological status of the general Chinese population may have greatly changed over the past three decades.

This review demonstrates the mental health risks for people living with HIV and reveals the need for greater support and prevention work. Reduction in the prevalence of mood disorders in people living with HIV should be a primary goal. Future studies should utilize larger and more rigorously characterized samples, as well as more sound methodologies. Research would also benefit from using consistent instruments for which data is already available in similar populations in the region. More studies are needed on suicidal behavior, substance use, HAND, and PTSD, as well as the co-occurrence of these problems, instead of just treating one problem as a risk factor for another. Additionally, more prospective longitudinal research is required to track the trend of mental health status concurrent with the natural history of disease.

It is important to note that, despite the obvious need for mental health services shown by this review, people living with HIV in China rarely access the support that they require [28]. Additionally, we found only one study that investigated mental health service utilization [27], and two studies indicated the need for psychological support for this population [22,24]. More research is also required to understand their mental health needs and develop effective intervention efforts to address this issue. Furthermore, although this review focused on quantitative data, qualitative evidence is also valuable. Because the qualitative reports are the voices of people living with HIV themselves—whether they view mental health as a problem and what they need in terms of care and support for mental health issues—a future review of qualitative evidence will aid greater learning and understanding of the mental health issues of this population.

Conclusion

This review identified the vulnerability of people living with HIV in terms of mental health issues, and depression and anxiety are most prevalent. It is imperative for academics, health care providers, and policy makers to address this issue as a matter of urgency, and to involve people living with HIV as well as their caregivers in defining their psychiatric and psychological needs. Combined with qualitative evidence, large-scale and longitudinal studies using standard instruments are needed to better inform policies on, and services for, the complex and diverse needs of different subgroups of people with HIV. It is time to put mental health services for people living with HIV in China on the healthcare agenda and develop an integrated mental health and physical health service.

Supporting Information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81202290) received by Dan Luo, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (D43 TW009101). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.National Health and Family Planning Commission of China. 2014 China AIDS response progress report. 25 June 2014. Available: http://www.unaids.org.cn/cn/index/Document_view.asp?id=860. Accessed 1 July 2015.

- 2.China News. The total number of alive people living with HIV in China is 497,000. 1 Dec 2014. Available: http://www.chinanews.com/gn/2014/12-01/6832958.shtml. Accessed on October 29th, 2015.

- 3.Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012 National report on notifiable infectious disease. 15 March 2013. Available: http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/jkj/s3578/201304/b540269c8e5141e6bb2d00ca539bb9f7.shtml. Accessed 16 April 2015.

- 4.Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014 National report on notifiable infectious disease. 16 Feb 2015. Available: http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/jkj/s3578/201502/847c041a3bac4c3e844f17309be0cabd.shtml. Accessed 16 April 2015.

- 5.Orza L, Bewley S, Logie CH, Crone ET, Moroz S, Strachan S, et al. How does living with HIV impact on women’s mental health? Voices from a global survey. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015; 18(Suppl 5):20289 10.7448/IAS.18.6.20289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao Y, Cui Y, Sun XH, Guo W, Xia G, Ding Z.A retrospective study of HIV/AIDS situation: a ten-year implementation of “four frees and one care” policy in China. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2014;18(5): 369–374. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Zhang Y, Miege P, Wang X, Wang X, Xu Y, et al. The Impact of the Global Fund on Equity, Financial Protection and Social Assistance Policy Development on HIV/AIDS Families in China. April 2008. Available: http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/projects/alliancehpsr_impactglobalfundchina08.pdf. Accessed 16 April 2015.

- 8.Brandt R. The mental health of people living with HIV/AIDS in Africa: a systematic review. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2009;8(2): 123–133. 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.2.1.853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherr L, Clucas C, Harding R, Sibley E, Catalan J. HIV and depression- a systematic review of interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2011;16(5): 493–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clucas C, Sibley E, Harding R, Liu L, Catalan J, Sherr L. A systematic review of interventions for anxiety in people with HIV. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2011;16(5): 528–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catalan J, Harding R, Sibley E, Clucas C. HIV infection and mental health: suicidal behavior-systematic review. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2011;16(5): 588–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rackstraw S. HIV-related neurocognitive impairment—A review. Psychology, health & medicine. 2011;16(5): 548–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62: e1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews andmeta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. International journal of surgery. 2010;8: 336–341. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loney PL, Chambers LW, Bennett KJ, Roberts JG, Stratford PW. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Diseases in Canada. 1998;19(4):170–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HJ, Park E, Storr CL, Tran K, Juon H-S. Depression among Asian-American Adults in the Community: Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6): e0127760 10.1371/journal.pone.0127760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang YJ, Qin XJ, Zhang H, Huang GF, Li GL, Li YJ. The study on depression and influencing factors among people living with HIV/AIDS. J Trop Med. 2013;13(11): 1381–1384, 1391. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin XJ, Yang YJ, Huang GF. Suicidal ideation and influencing factors among people living with HIV/AIDS. South China J Prev Med. 2014;40(03): 208–211. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heaton RK, Cysique LA, Jin H, Shi C, Yu X, Letendre S, et al. Neurobehavioral effects of human immunodeficiency virus infection among former plasma donors in rural China. Journal of NeuroVirology. 2008;14: 536–549. 10.1080/13550280802378880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cysique LA, Letendre SL, Ake C, Jin H, Franklin DR, Gupta S, et al. Incidence and nature of cognitive decline over 1 year among HIV-infected former plasma donors in China. AIDS. 2010;24(7): 983–990. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833336c8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkinson JH, Jin H, Shi C, Yu X, Duarte NA, Casey CY, et al. Psychiatric context of Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection among former plasma donors in rural China. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;130(3): 421–428. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv YH. A cross-sectional study on the mental health among people living with HIV/AIDS. M.Sc. Thesis, Peking Union Medical College. 2007. Available: http://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?QueryID=1&CurRec=1&recid=&filename=2007211763.nh&dbname=CMFD2008&dbcode=CMFD&pr=&urlid=&yx=&uid=WEEvREcwSlJHSldSdnQ0SWZaaGxST1Biem9NQmkwMjhqdXVCVkRlRUNzQ1hCZDY4QVhTY2JEWWVOT2ZRSXRESWVnPT0=$9A4hF_YAuvQ5obgVAqNKPCYcEjKensW4IQMovwHtwkF4VYPoHbKxJw!!&v=MjI4MTNKRWJQSVI4ZVgxTHV4WVM3RGgxVDNxVHJXTTFGckNVUkwrZlllUm1GeWpnVmI3SVYxMjdHYkc1SDliS3I=. Accessed 23 January 2015.

- 23.Li K, Jiang QC. Analysis of psychological health status among paid blood donors infected with HIV in rural are. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2008;12(6): 550–552. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu XN, Lau JTF, Mak WWS, Cheng YM, Lv YH, Zhang JX. Risk and protective factors in association with mental health problems among people living with HIV who were former plasma/blood donors in rural China. AIDS Care. 2009;21(5): 645–654. 10.1080/09540120802459770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meade CS, Wang JP, Lin XY, Wu H, Poppen PJ. Stress and Coping in HIV-Positive Former Plasma/Blood Donors in China: A Test of Cognitive Appraisal Theory. Aids and Behavior. 2010;14(2): 328–338. 10.1007/s10461-008-9494-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su PY, Tao FB, Hao JH, Huang K, Zhu P. Mental health and risk behavior of married adult HIV/AIDS subjects derived from paid blood donation in the rural of Anhui Province. Journal of Hygiene Research. 2010;39(6): 739–742, 746 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau JTF, Yu XN, Mak WWS, Cheng YM, Lv YH, Zhang JX. Suicidal ideation among HIV+ former blood and/or plasma donors in rural China. AIDS Care. 2010;22 (8): 946–954. 10.1080/09540120903511016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu HY, Sun YH, Zhang XJ, Zhang ZK, Cao HY. Study on the social psychology influencing factors of suicidal ideation in people living with AIDS. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2007;11(4): 342–345. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Wu JL, Ge Q, Wang CR. The emotion state of 105 HIV infected patients in rural areas and influencing factor. Medicine and Society. 2007;20(2): 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi CR, Zhang MH, Gao XY, Gao BX. Investigation on the psychological conditions of the HIV infected and their families. China Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;16(12): 1409–1411. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang YC, Li AQ. A study on depression, anxiety and related factors in pregnant women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Chinese Journal of Family Planning. 2010;18(6): 340–343. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li L, Liang LJ, Ding YY, Ji GP. Facing HIV as a Family: Predicting Depressive Symptoms With Correlated Responses. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25(2): 202–209. 10.1037/a0022755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie Z, Xie CY, Liu HJ, Jin YT, Li PY, Chen XM. Analysis on psychological health and personality types of HIV/AIDS patients in rural Henan province. Chinese Journal of Practical Nervous Diseases. 2012;15(24): 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pei XL, Peng ZB, Liu M, Chen SQ. Research on the depression and risk factors in pulmonary tuberculosis patients with positive HIV antibodies. Medical Journal of Chinese People’s Health. 2007;19(11): 511,513. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou P. Analysis on psychological status among TB co-infection with HIV patients. For all Health. 2014;8(20): 435–435. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao JH, Liu ZH, Jiang CS, Tan YQ, Qin ZY, Tang JW, et al. Western Guangxi and TB co-infection with HIV (HIV/TB) patients with mental health and social support study analysis. Popular Science & Technology. 2014;16(03): 107–109. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greene MC, Zhang JP, Li JH, Desai M, Kershaw T. Mental health and social support among HIV-positive injection drug users and their caregivers in China. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5): 1775–1784. 10.1007/s10461-012-0396-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin H, Atkinson JH, Duarte NA, Yu X, Shi C, Riggs PK, et al. Risks and predictors of current suicidality in HIV-infected heroin users in treatment in Yunnan, China: a controlled study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(3): 311–316. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827ce513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fang LW, Wang LH, Wang Q. Study on characteristics and infected route of 572 cases maternal women living with HIV infection in four provinces. Maternal and Child Health Care of China. 2008;23(11): 1525–1528. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang HX. Research on the stress and its correlates of HIV-infected pregnant women. M.Sc. Thesis, Kunming Medical College. 2011. Available: http://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?QueryID=5&CurRec=1&recid=&filename=1011122124.nh&dbname=CMFD2011&dbcode=CMFD&pr=&urlid=&yx=&uid=WEEvREcwSlJHSldSdnQ0SWZaaGxST1Biem9NQmkwMjhqdXVCVkRlRUNzQ1hCZDY4QVhTY2JEWWVOT2ZRSXRESWVnPT0=$9A4hF_YAuvQ5obgVAqNKPCYcEjKensW4IQMovwHtwkF4VYPoHbKxJw!!&v=MDA3Nzh6QlZGMjZIN0s2SE5ET3E1RWJQSVI4ZVgxTHV4WVM3RGgxVDNxVHJXTTFGckNVUkwrZlllUm1GeWpoVXI=. Accessed 23 January 2015.

- 41.Wu X. Mental health, risk behaviours and illness perception among newly diagnosed HIV positive men who have sex with men in China. Ph.D. Thesis, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. 2014. Available: http://gateway.proquest.com/openurl?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&res_dat=xri:pqm&rft_dat=xri:pqdiss:3538928. Accessed 23 January 2015.

- 42.Cheng X. Mental health status and intervention strategies among male homosexuality PLWHA. M.Sc. Thesis, Nanchang University. 2014. Available: http://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?QueryID=1&CurRec=1&recid=&filename=1014055291.nh&dbname=CMFD201501&dbcode=CMFD&pr=&urlid=&yx=&uid=WEEvREcwSlJHSldSdnQ0SWZxdkw4YkJ5Q1NFQ1JrMlJyOUdyYm91OTJUNEc2Q0ZwbzVvTEVZcXdUeWRrTzdac0dBPT0=$9A4hF_YAuvQ5obgVAqNKPCYcEjKensW4IQMovwHtwkF4VYPoHbKxJw!!&v=MjkzNThSOGVYMUx1eFlTN0RoMVQzcVRyV00xRnJDVVJMK2ZZT1p1RmlEa1Y3N0pWRjI2R3JPOUc5UEZycEViUEk=. Accessed 23 January 2015.

- 43.Xu Q, Ye L, Yang CK, Li JJ, Wang XL, Yan HJ, et al. Efficacy of HAART and its determinants in men who have sex with men in two cities of Jiangsu. Acta Universitatis Medicinalis Nanjing (Natural Science). 2014;34 (06): 834–838. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ren YX An epidemiologic study on suicide ideation and attempts among people living with HIV/AIDS. M.Sc. Thesis, Guangdong Pharmaceutical University. 2009. Available:http://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?QueryID=5&CurRec=1&recid=&filename=2009226509.nh&dbname=CMFD2010&dbcode=CMFD&pr=&urlid=&yx=&uid=WEEvREcwSlJHSldSdnQ0SWZxdkw4YkJ5Q1NFQ1JrMlJyOUdyYm91OTJUNEc2Q0ZwbzVvTEVZcXdUeWRrTzdac0dBPT0=$9A4hF_YAuvQ5obgVAqNKPCYcEjKensW4IQMovwHtwkF4VYPoHbKxJw!!&v=MjM2NTViUElSOGVYMUx1eFlTN0RoMVQzcVRyV00xRnJDVVJMK2ZZT1p1RmlEa1dyek9WMTI3RjdHNkdOVE1wcEU=. Accessed 23 January 2015.

- 45.Chen QL, Zhou ZQ, Wen YH, Lu WQ, Huang GG, Jia M, et al. Effect of mental health and psychosocial factors in individuals with HIV/AIDS. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2004;18(12): 850–853. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang GG, Li S, Chen QL, Zhang J, Jiang ZL, Guo Y, et al. Investigation of psychological health of HIV infections and AIDS cases in Honghe Prefecture. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;12(6): 464–465. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, Wu XY, Zhang XD, Zhou PL, He HX, Qiu YF. Investigative of psychological status of patients with HIV/AIDS. J of Pub Health and Prev Med. 2005;16(2): 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu JY, Zhao G. Comparation of psychological problems between HIV-infected patients and the general. Zhejiang Prev Med. 2007;19(10): 60,65. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun HM, Zhang JJ, Fu XD. Psychological status, coping, and social support of people living with HIV/AIDS in central China. Public Health Nursing. 2007;24(2): 132–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen G, Xiong HY, Zhu Q, Chen QW, Wei SQ. Survey of mental health of rural individuals with HIV/AIDS in a county of Henan Province. Acta Academiae Medicinae Militaris Tertiae. 2008;30(11): 1091–1093. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu SH, Tang XP, Deng XL, Chen WL, Hu RX. Relationship between psychological distress and T lymphocyte in HIV/AIDS patients. Chinese J Exp Clin Virol. 2009;23(1): 23–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yin YT, Li J. Analysis of mental health status in HIV/AIDS patients. Modem Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(20): 3913–3914. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bao MJ, Du YY, Lu Y, Wang XL, Zhang J, Zhang JJ. Analysis on SCL-90 scores among 80 HIV/AIDS patients in Shanghai. Proceedings of the Fifth CAACM Clinical Microbiology & AIDS Opportunistic Infection Symposium, Shanghai. 2009. Available: http://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/Conference_7232961.aspx. Accessed 23 January 2015.

- 54.Gully A, Peng LH, Xie DE.Mental health and related factors among AIDS patients. Chin J Mod Dru Appl. 2010;04(11): 213–215. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang JN, Qu WY. Psychological change of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection or acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Chin J Health Manage. 2010;04(4): 196–199. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jin C, Zhao G, Zhang F, Feng L, Wu N. The psychological status of HIV-positive people and their psychosocial experiences in eastern China. HIV Med. 2010;11(4): 253–9. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00770.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu WQ, Huang LH, Ma LP. Investigation on psychological status among HIV/AIDS patients. Chinese Medicine Modern Distance Education of China. 2011;9(16):109–109, 112. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu JP, Ma YM, Du ST. Psychological status and related factors among HIV-infected patients in paid-blood-donation district in Henan province. Journal of Medical Forum. 2011;32(14): 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu SP, Ge Z, Peng YM. Mental health of inpatients who were newly diagnosis of HIV infection. Medical Journal of National Defending Forces in Southwest China. 2012;22(5): 580–581. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Y, Han YP, Wang J.Mental health of 38 AIDS patients in Yunnan Province. China Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;20(1): 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie SP, Liu XX, Sang HY, Xu QL, Hou MJ, Zhang M, et al. A study of changes in the mental health status of 106 patients with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Pathogen Biology. 2012;7(10): 781–783. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao J, Wang L, Duan CY, Qu GC, Li YP, Fang L, et al. An investigation of mental health status of 32 clinic patients with HIV/AIDS. Yunnan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Materia Medica. 2012;33(10): 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guo ZK, Qu RB. Mental health of HIV/AIDS patients and intervention strategies. Chinese and Foreign Medical Research. 2013;11(8): 151–152. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou ZH, Gao YX. Mental health of AIDS/HIV positive clients. China Journal of Health Psychology. 2014;22(1): 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yao HJ, Zhu XZ, Wang H, Gu KK. Analysis of mental health status among people with HIV/AIDS in Shanghai. Chinese Primary Health Care. 2014;28(3): 48–49, 54. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li J, Kuang WH, Ma YG, Liao Q. Anxiety and depression of the HIV infected persons or AIDS patient and their family member. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2004;18(8): 530–532. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu HN. The study of factors affecting medicine adherence among 59 HIV/AIDS patients. M.Sc. Thesis, Dalian Medical University. 2006. Available: http://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?QueryID=0&CurRec=1&recid=&filename=2006141171.nh&dbname=CMFD0506&dbcode=CMFD&pr=&urlid=&yx=&uid=WEEvREcwSlJHSldSdnQ0SWZxdkw4YkJ5Q1NFQ1JrMlJyOUdyYm91OTJUNEc2Q0ZwbzVvTEVZcXdUeWRrTzdac0dBPT0=$9A4hF_YAuvQ5obgVAqNKPCYcEjKensW4IQMovwHtwkF4VYPoHbKxJw!!&v=MzA4MzZXNy9OVjEyN0dMSzhIOURMcnBFYlBJUjhlWDFMdXhZUzdEaDFUM3FUcldNMUZyQ1VSTCtmWU9adUZpRG0=. Accessed 23 January 2015.

- 68.Qian ZZ, Yu DB. Psychological characteristics of HIV/AIDS patients in two cities. J of Pub Health and Prev Med. 2006;17(5): 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu YC, Zhao YB, Tang MG, Zhuang-Nunes SX, McArhur JC. AIDS dementia complex in China. Journal of clinical neuroscience. 2007;14(1): 8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fang GX, Jiang QC, Dong Y. Analysis and study of psychological state among paid blood donors infected with HIV in rural areas. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2007;11(2): 127–129. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li BG, Zhu Y, Mo J, Zhang JP. Psychological evaluation of anxiety and depression response for 95 cases of HIV positive people. Journal of Kunming Medical University. 2008;29(6): 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang HH, Zhou J, Huang L. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral treatment and related factors in drug users with HIV/AIDS. Chin J Behavioral Med Sci. 2008;17(10): 881–883. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen X, Chen XY, Zhuo YN. Relationship between depression and social support in people living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Nursing Science. 2008;23(17): 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu TZ, Fu JH, Kang DM, Qian YS, Lv CX, Zhang XF. Investigation on living condition among HIV-infected patients in Shandong Province. Prev Med Trib. 2010;16(03): 228–230. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lu L, He CY, Yang YH. Analysis and persuasion of depression during AIDS patients in rural areas. China Modern Doctor. 2010;48(6): 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang ZL. Analysis on anxiety, depression among HIV infected patients and related strategies. Journal of Medical Forum. 2010;31(19): 100–101. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu Q, Yang JJ, Guo Y. Investigation on depression and social support among people living with HIV/AIDS. Medical Journal of Wuhan University. 2011;32(2): 273–276. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sun YH, Fan AP, Yan XL. Survey on psychology status and related factors among population with HIV/AIDS. Chin J of PHM. 2011;27(03): 314–316. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dong WY, Geng WK, Huang JP, Tang YQ, Ou RZ, Qin YM. Multi-variated logistic regression analysis of influencing factors of the depression in the HIV-infected out-patients. Chinese Journal of New Clinical Medicine. 2011;04(5): 429–433. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huang CY, Du LQ. Investigation on anxiety and depression among HIV/AIDS patients and related factors. China Health Care & Nutrition. 2013;23(3): 1475–1475. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Au A, Cheng C, Shan I, Leung P, Li P, Heaton RK. Subjective memory complaints, mood, and memory deficits among HIV/AIDS patients in Hong Kong. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2008;30(3): 338–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bai P. The evaluation of degree of depression and quality of life of HIV/AIDS patients. Chinese and Foreign Medical Research. 2012;10(20): 61–62. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yuan D. The effect of attribution on the HIV/AIDS patients’ psychology and behavior—the mediating effect of the living condition. M.Sc. Thesis, Ningbo University. 2012. Available: http://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?QueryID=0&CurRec=1&recid=&filename=1012050761.nh&dbname=CMFD201301&dbcode=CMFD&pr=&urlid=&yx=&uid=WEEvREcwSlJHSldSdnQ0SWZxdkw4YkJ5Q1NFQ1JrMlJyOUdyYm91OTJUNEc2Q0ZwbzVvTEVZcXdUeWRrTzdac0dBPT0=$9A4hF_YAuvQ5obgVAqNKPCYcEjKensW4IQMovwHtwkF4VYPoHbKxJw!!&v=MDQ4MjdTN0RoMVQzcVRyV00xRnJDVVJMK2ZZT1p1RmlEaFZMckxWRjI2SExPOUh0YktycEViUElSOGVYMUx1eFk=. Accessed 23 January 2015.

- 84.Su XY, Lau JTF, Mak WWS, Choi KC, Chen L, Song JM, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depression among people living with HIV in two cities in China. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;149(1–3): 108–115. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wright E, Brew B, Arayawichanont A, Robertson K, Samintharapanya, Kongsaengdao S, et al. Neurologic disorders are prevalent in HIV-positive outpatients in the Asia-Pacific region. Neurology. 2008;71(1): 50–56. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316390.17248.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gao LL, Wang M, Xu HF, Chen WQ. Effects of psychosocial factors on emotional disorders in HIV positive persons. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2010;14(5): 415–418. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rao D, Chen WT, Pearson CR, Simoni JM, Fredriksen-Goldsen K, Nelson K, et al. Social support mediates the relationship between HIV stigma and depression/quality of life among people living with HIV in Beijing, China. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(7): 481–4. 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dwyer R, Wenhui L, Cysique L, Brew BJ, Lal L, Bain P, et al. Symptoms of depression and rates of neurocognitive impairment in HIV positive patients in Beijing, China. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;162: 89–95. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang HH, Zhang CH, Ruan Y, Li XH, Fennie K, Williams AB.Depressive Symptoms and Social Support Among People Living With HIV in Hunan, China. Janac-Journal of the Association of Nurses in Aids Care.2014; 25(6): 568–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sun W, Wu M, Qu P, Lu CM, Wang L. Psychological well-being of people living with HIV/AIDS under the new epidemic characteristics in China and the risk factors: a population-based study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014;28: 147–152. 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chan I, Au A, Li P, Chung R, Lee MP, Yu P. Illness-related factors, stress and coping strategies in relation to psychological distress in HIV-infected persons in Hong Kong. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8): 977–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen FQ, Li F, Chen LL, Li Y, Li Y, Guo ZA, et al. Depression and anxiety among HIV/AIDS patients. J Dermatology and Venereology. 2014;36(2): 110–112. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li L. A study on living status of people living with HIV/AIDS in high HIV prevalence districts. M.Sc. Thesis, Peking Union Medical College. 2007. Available: http://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?QueryID=0&CurRec=1&recid=&filename=2007211702.nh&dbname=CMFD2008&dbcode=CMFD&pr=&urlid=&yx=&uid=WEEvREcwSlJHSldSdnQ0SWZxdkw4YkJ5Q1NFQ1JrMlJyOUdyYm91OTJUNEc2Q0ZwbzVvTEVZcXdUeWRrTzdac0dBPT0=$9A4hF_YAuvQ5obgVAqNKPCYcEjKensW4IQMovwHtwkF4VYPoHbKxJw!!&v=MTYxMThNMUZyQ1VSTCtmWU9adUZpRG1VTC9LVjEyN0diRzVIOWJNclpFYlBJUjhlWDFMdXhZUzdEaDFUM3FUclc=. Accessed 23 January 2015.

- 94.Zhou G. A study on psychological states and coping styles in HIV/AIDS during the antiretroviral therapy in three hospitals in Yunnan Province. M.Sc. Thesis, Kunming Medical University. 2014. Available: http://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?QueryID=4&CurRec=1&recid=&filename=1014344331.nh&dbname=CMFD201501&dbcode=CMFD&pr=&urlid=&yx=&uid=WEEvREcwSlJHSldSdnQ0SWZxdkw4YkJ5Q1NFQ1JrMlJyOUdyYm91OTJUNEc2Q0ZwbzVvTEVZcXdUeWRrTzdac0dBPT0=9A4hF_YAuvQ5obgVAqNKPCYcEjKensW4IQMovwHtwkF4VYPoHbKxJw!!&v=MTY0MTMzcVRyV00xRnJDVVJMK2ZZT1p1RmlEblVMekxWRjI2R3JDOEd0TFBycEViUElSOGVYMUx1eFlTN0RoMVQ=. Accessed 23 January 2015.

- 95.Liu Y, Gong HY, Yang GL, Yan J. Perceived stigma, mental health and unsafe sexual behaviors of people living with HIV/AIDS. J Cent South Univ (Med Sci). 2014;39(07): 658–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Qiu YY, Luo D, Cheng R, Xiao Y, Chen X, Huang ZL, et al. Emotional problems and related factors in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Cent South Univ (Med Sci). 2014;39(8): 835–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shi CR, Zhang MH, Wang Y, Yang YJ. Investigation on the emotional state of HIV infected individuals and their family members and related factors. Chin J AIDS STD. 2010;16 (01): 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bai GX, Tai YD, Li CH. Anxiety among HIV/AIDS patients. Chinese Remedies & Clinics. 2008;8(S1): 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pan CE, Zha LJ, Sun JJ, Ren CY, Lu HZ. Analysis of anxiety symptoms among AIDS patients in Shanghai. Chin J Mod Nurs. 2010;16(3): 259–261. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhen LX, Chen XM, Ding HY, Liu JJ, Tian AL. The correlation between anxiety and social support among HIV-infected patients. Chinese Journal of Practical Nervous Diseases. 2011;14(10): 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang YJ, Qin XJ, Zhang H, Huang GF, Li GL, Li YJ.The study on depression and influencing factors among people living with HIV/AIDS. J Trop Med. 2013;12(5): 605–609. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wu M, Yao WQ, Wang L, Sun LX, Yang GL, Zhang FQ, et al. The mediating role of psychological capital in the relationship between social support and anxiety symptoms among people living with HIV/AIDS. Chronic Pathemathol J. 2013;14 (07): 489–491. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Qu WY, Tian JH, Xu KX, Wang KR. The study of the cause of suicide among people living with HIV/AIDS and crisis intervention. China J AIDS/STD. 2005;11(2): 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lai WH, Yu H, Luo YJ, Li T, Liu L, Zhou JS, et al. Survival analysis for AIDS patients in Sichuan province after antiretroviral therapy. Chin J Public Health. 2011;27(12): 1521–1522. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li YX. Study of PTSD and its determinants among people living with HIV/AIDS. M.Sc. Thesis, Central South University. 2013. Available: http://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?QueryID=5&CurRec=1&recid=&filename=2009226509.nh&dbname=CMFD2010&dbcode=CMFD&pr=&urlid=&yx=&uid=WEEvREcwSlJHSldSdnQ0SWZxdkw4YkJ5Q1NFQ1JrMlJyOUdyYm91OTJUNEc2Q0ZwbzVvTEVZcXdUeWRrTzdac0dBPT0=$9A4hF_YAuvQ5obgVAqNKPCYcEjKensW4IQMovwHtwkF4VYPoHbKxJw!!&v=MjM2NTViUElSOGVYMUx1eFlTN0RoMVQzcVRyV00xRnJDVVJMK2ZZT1p1RmlEa1dyek9WMTI3RjdHNkdOVE1wcEU=. Accessed 23 January 2015.

- 106.Zhang YL, Qiao LX, Ding W, Wei FL, Zhao QX, Wang XC, et al. An initial screening for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders of HIV-1 infected patients in China. J Neurovirol. 2012;18(2):120–126. 10.1007/s13365-012-0089-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhao TT, Huang JR, Tang XY, Wei B. The effects of educational background on IHDS scores among HIV/AIDS patients in Guangxi. Guangdong Medical Journal. 2013;34(16): 2506–2508. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhen LF, Pan CE, Liu L, Zhang RF, Shen YZ, Qi TK, et al. Occurrence of neurocognitive disorders in 136 acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients in Shanghai. J Intern Med Concepts Pract. 2013;8(02): 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Luo XF, Duan S, Duan QX, Pu YC, Yang YC, Ding YY, et al. Alcohol Use and Subsequent Sex among HIV-Infected Patients in an Ethnic Minority Area of Yunnan Province, China. Plos One. 2013; 8(4): e61660 10.1371/journal.pone.0061660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shan JH, Yuan M, Lu YH. Investigation on high-risk behaviors among people infected with HIV in Dongguan City, Guangdong Province. Chineses Journal of Health Education. 2009;25(5): 366–368. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jin H, Wu WY, Zhang MY. Preliminary analysis on SCL-90 scores among the Chinese general. Chinese Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 1986;12(5): 260–263. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.