Abstract

This study investigated roles of racial and ethnic socialization in the link between racial discrimination and school adjustment among a sample of 233 adopted Korean American adolescents from White adoptive families and 155 non-adopted Korean American adolescents from immigrant Korean families. Adopted Korean American adolescents reported lower levels of racial discrimination, racial socialization, and ethnic socialization than non-adopted Korean American adolescents. However, racial discrimination was negatively related to school belonging and school engagement, and ethnic socialization was positively related to school engagement for both groups. Racial socialization also had a curvilinear relationship with school engagement for both groups. Moderate level of racial socialization predicted positive school engagement, whereas low and high levels of racial socialization predicted negative school engagement. Finally, ethnic socialization moderated the link between racial discrimination and school belonging, which differed between groups. In particular, ethnic socialization exacerbated the relations between racial discrimination and school belonging for adopted Korean American adolescents, whereas, ethnic socialization buffered this link for non-adopted Korean American adolescents. Findings illustrate the complex relationship between racial and ethnic socialization, racial discrimination, and school adjustment.

Keywords: racial socialization, ethnic socialization, racial discrimination, Korean Americans, transracial adoptees, school adjustment

Perceptions and consequences of racial discrimination can begin at an early age for children (Coker et al., 2009). Consequently, many parents teach their children to cope with racism and to understand and appreciate their ethnic and racial group membership, known as racial and ethnic socialization (Hughes et al., 2006). However, there is limited research examining the process and outcome of racial and ethnic socialization for Asian American families, with even less attention given to multiracial Asian American families. In the present study, we examined the relationship between perceived racial discrimination, racial and ethnic socialization experiences, and school adjustment among Korean American adolescents growing up in monoracial and multiracial families. Specifically, we compared experiences of transnationally, transracially adopted Korean American adolescents raised by White parents and non-adopted Korean American adolescents raised by Korean immigrant parents. The comparison of adopted and non-adopted Korean American adolescents provides a unique opportunity to explore the diversity within Korean American families, and more specifically, similarities and differences between two groups who share the same race and ethnicity, but differ in their parents’ racial and ethnic backgrounds and socialization experiences (R. M. Lee, 2003).

Racial and Ethnic Experiences of Adopted and Non-adopted Korean Americans

Korean Americans represent the fifth largest Asian ethnic group in the United States with approximately 1.7 million people and are one of the fastest growing populations with a 39% increase from 2000 to 2010 (Hoeffel, Rastogi, Kim, & Hasan, 2012). Korean Americans have endured a longstanding history of individual, institutional, and cultural forms of racism (Takaki, 1989). Their experiences of racism continues today, ranging from everyday encounters of racial microaggression to systemic institutional and cultural hegemonic policies and values (Wu, 2002). In particular, Korean Americans are often treated as perpetual foreigners, exotic, or successful model minorities (Gee & Ponce, 2010; J. Kim, Suh, & Heo, 2014). These racialized experiences are similar to other Asian ethnic groups, since Asian Americans are targets of racism because of their shared phenotypic characteristics and not because of their ethnic group membership (Yoo, Steger, & Lee, 2010). However, the diversity within Asian Americans, including multiracial families, may shape how particular groups perceive, process, and cope with racism—a phenomenon less clear in the literature.

Over 110,000 children from South Korea have been adopted by almost exclusively White families in the United States since 1953 (Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2010). Transnational adoption from South Korea peaked in the late 1980s but continued in large numbers (i.e., more than 2000 children per year) through the 1990s. Although the numbers have dropped dramatically since then, there remains transnational adoption from South Korea to the United States and elsewhere in the world. Based on these adoption statistics, adopted Korean Americans constitute an estimated 5% of the 1.7 million Korean Americans living in the United States (U. S. Census Bureau, 2010).

Adopted Korean American adolescents who are raised in White families are often perceived and treated as members of the majority culture (i.e., racially White and ethnically European) by family members and friends, as well as themselves, even though they remain racial and ethnic minorities in society and, as such, experience racism (R. M. Lee, 2003; Meier, 1999; Tuan & Shiao, 2011). It is perhaps not surprising then that Freundlich and Lieberthal (2000) found that one-third of adopted Korean American adults described themselves as Caucasian/White while growing up, but only 11% identified as such as adults. Docan-Morgan (2010) also found that adopted Korean American adults often recalled memories of being verbally attacked because of their racial appearances (e.g., “flat nose” and “slant eyes”) and ethnic stereotypes (e.g., know martial arts or too foreign) as children. Brooks and Barth (1999) similarly found that one-third of Asian transracial adoptees reported that they experienced negative comments on their ethnicity and race. Interestingly, Asian adoptees reported more discomfort with their appearances and less pride in their racial and ethnic group than Black transracial adoptees even though this latter group reported more negative ethnic and racial comments. More recently, R. M. Lee and colleagues (2010) found White parents with children adopted transnationally from Asia and Latin America reported more perceived discrimination (i.e., intrusive and inappropriate racial and adoption comments) directed to the child and family than parents with children adopted from Eastern Europe.

Racial Discrimination and School Adjustment

It is well established that racial discrimination is associated with a wide range of mental health and physical health/health-behavior outcomes among Asian Americans (see Gee et al., 2009, for review) and Korean Americans in particular (Bernstein, Park, Shin, Cho, & Park, 2011; Choi, Tan, Yasui, & Pekelnicky, 2014; Gee & Ponce, 2010; J. Kim et al., 2014; R. M. Lee, 2005; Shin, D’Antonio, Son, Kim, & Park, 2011; Shrake & Rhee, 2004), but recent studies also suggest that racial discrimination is an important risk factor for the academic success of Asian Americans (Benner & Kim, 2009; McGill, Hughes, Alicea, & Way, 2012; Neblett, Philip, Cogburn, & Sellers, 2006). For instance, perceived racial discrimination is associated with lower grade point average among Asian American high school students (Hyun & Fuligni, 2010; Yoo & Castro, 2011). Studies also have found perceived discrimination is related to lower school engagement and academic achievement (Benner & Kim, 2009; Samuel, 2004), and school belongingness (Faircloth & Hamm, 2005) among Asian American youths.

Fewer studies have examined the negative consequences of racial discrimination on adopted Korean American adolescents and adults. Cederblad, Hook, Irhammar, and Mercke (1999) found being teased for “looking foreign” was associated with higher internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems and lower self-esteem among transracial adoptees in Sweden, which included Korean teenagers and young adults. R. M. Lee and colleagues (2010) similarly reported that racial discrimination was positively correlated with internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems, above and beyond pre-adoption adversity among internationally adopted Asian adolescents. Using the same data as the aforementioned R. M. Lee et al. (2010) study, R. M. Lee, Perry and The Minnesota International Adoption Project Team (2010) found perceived discrimination was significantly related to lower social competence and marginally related to lower academic performance for internationally adopted Asian adolescents.

Racial and Ethnic Socialization and Adjustment

Given the challenges of growing up as racial and ethnic minorities in society, scholars have examined racial and ethnic socialization as protective factors for racial and ethnic minority youths (Harris-Britt, Valrie, Kurtz-Costes, & Rowley, 2007; Hughes et al., 2006). The terms racial socialization and ethnic socialization are used broadly to refer to the transmission of information regarding race and ethnicity from adults to children, although scholars have begun to differentiate the terms (Hughes et al., 2006; R. M. Lee, 2003). For the purpose of this study, racial socialization refers to specific discussions and instructions in preparing children to deal with racial stereotypes and racism. For instance, parents may talk to their children about possible limitations or needing to work harder to get the same rewards because of their Korean background. Ethnic socialization refers to communication and teaching children about their cultural values, customs, history, and language. For instance, parents may teach their children about what it means to be Korean and encourage them to learn and speak Korean.

There is limited research that illustrates the racial and ethnic socialization process for Asian Americans or Korean Americans in particular. In one study by Choi and Kim (2010), Korean immigrant parents largely preserved and maintained their traditional Korean values at home. They were reluctant to adapt mainstream Western parental values, except in areas that they believed benefited their children. In particular, Korean American parents worried about their children growing up as racial and ethnic minorities. Consequently, they emphasized traditional Korean values and behaviors to help their children develop a strong sense of ethnic identity to buffer the effects of racism. In another study, Choi and colleagues (Choi, Kim, Pekelnicky, & Kim, 2013) found that Korean ethnic socialization included emphasizing family hierarchy, education, demonstration of respect for and the use of appropriate etiquette with parents and elders, and family obligations and ties. These ethnic socialization experiences reported by youth positively related to Korean identity, and in turn, negatively related to depressive symptoms among early Korean American adolescents (Choi et al., 2014). Interestingly, ethnic socialization reported by their parents did not have the same effect.

For transnational, transracial adoptive families, the process of racial and ethnic socialization is often complicated by the parental lack of first-hand knowledge and experiences of being a racial and ethnic minority in the United States (R. M. Lee, 2003). In a mixed-method study of 30 adopted Korean American adolescents and White parents, for example, O. M. Kim, Reichwald, and Lee (2013) found only one-third of the families were able to constructively talk about racial and ethnic differences within the families. Most families either downplayed or denied the relevance of race and ethnicity in the family or talked about racial and ethnic issues in a conflicted or superficial way that occasionally trivialized the experiences of the adopted child. Other studies similarly found that adopted Korean American adolescents and adults often struggled and avoided talking to their White adoptive parents about experiences of racism growing up because they perceived their parents as being unresponsive or felt the need to minimize racial and ethnic differences (Bergquist, Campbell, & Unrau, 2003; Docan-Morgan, 2010).

Although racial socialization and ethnic socialization are viewed as being important to the adjustment and well-being of racial and ethnic minority youths (Caughy, O’Campo, Randolph, & Nickerson, 2002; Hughes & Chen, 1999; Wang & Huguley, 2012), current research with monoracial Asian American families is more mixed. Extant research suggests ethnic socialization is associated with positive youth adjustment, but the effects of racial socialization are less clear. For Asian American adolescents and young adults, ethnic socialization has been directly linked to higher academic motivation (Huynh & Fuligni, 2008), higher self-esteem (Brown & Ling, 2012), and lower depressive symptoms (Liu & Lau, 2013). It has also been indirectly linked to higher social competence (Tran & Lee, 2010), higher self-esteem (Brown & Ling, 2012; Gartner, Kiang, & Supple, 2014), and lower depressive symptoms (Choi et al., 2014) through higher ethnic identity. In contrast, racial socialization has been significantly related to higher depression for Asian American adolescents and young adults (Gartner et al., 2014; Liu & Lau, 2013) or no relationship at all with adjustment for Asian American adolescents (Tran & Lee, 2010). Far less is known about the relationship between racial and ethnic socialization and adjustment among adopted Korean American youths. In one of the few studies, ethnic socialization was associated with lower externalizing behavior problems (Johnston, Swim, Saltsman, Deater-Deckard, & Petrill, 2007) and higher psychological well-being (Basow, Lilley, Bookwala, & McGillicuddy-DeLisi, 2008).

Role of Racial and Ethnic Socialization

The differential effect of racial and ethnic socialization on adjustment outcomes may depend on how a child receives different types of socialization messages. For instance, Liu and Lau (2013) found that the links between racial and ethnic socialization and depression symptoms were mediated by optimism and pessimism among a diverse sample of African American, Latino, and Asian American young adults. In particular, individuals who reported that their families engaged in ethnic socialization had a more optimistic and less pessimistic outlook, which in turn, explained lower levels of depression symptoms. In contrast, racial socialization was linked to greater pessimism and less optimism, which in turn, were associated with higher levels of depression symptoms. However, the authors cautioned that their results did not necessarily imply that engaging in any amount of racial socialization would affect poor psychological adjustment. Instead, the impact of racial socialization may vary depending on how much preparation for racial bias messages are given. Some scholars (Frabutt, Walker, & MacKinnon-Lewis, 2002; Harris-Britt et al., 2007; Hughes & Johnson, 2001) have suggested a curvilinear relationship between racial socialization and adjustment outcomes. Therefore, moderate amounts of preparation for racially biased messages are necessary for healthy adjustment of racial minority youths, yet little to no messages may leave them ill-prepared and too many messages may leave them overwhelmed and feeling inadequate to overcome racism.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no published study that examines whether racial and ethnic socialization buffers the effect of racial discrimination on psychological outcome for Asian Americans. There are however a few empirical studies using African American samples that might shed light on how minority youth in general and Asian American adolescents in particular use racial and ethnic socialization experiences to cope with racial discrimination. Wang and Huguley (2012) found that ethnic socialization attenuated the effects of peer and teacher racial discrimination on academic achievement and educational aspirations among African American adolescents. Similarly, Harris-Britt et al. (2007) reported the buffering interaction effect on self-esteem among African American adolescents. However, the potential protective property of racial socialization when dealing with racism again is not as clear. For instance, Wang and Huguley (2012) and Neblett et al. (2006) did not find a significant interaction effect with racial socialization. Fischer and Shaw (1999) reported a negative relationship between perceived racism and mental health at low levels, but not at high levels of racial socialization among African American college students. In efforts to address the mixed findings, Harris-Britt et al. (2007) examined whether the adaptive properties of racial socialization varied depending on the levels of racial socialization received. Specifically, they tested a curvilinear moderation model of racial socialization between perceived racism and self-esteem among African American adolescents. Results found that a negative relationship between perceived discrimination and self-esteem was mitigated for youths who reported moderate amount of racial socialization from their parents, but was exacerbated for those who reported both low and high levels of racial socialization. Thus, it seems that ethnic socialization may linearly moderate the discrimination and outcome link, whereas racial socialization may curvilinearly moderate the discrimination and outcome link.

Study Purpose and Hypotheses

We examined the relationship between perceived racial discrimination, racial and ethnic socialization experiences, and school adjustment (i.e., school belonging and school engagement) of adopted and non-adopted Korean American adolescents. We expected that adopted and non-adopted Korean American adolescents would have similar experiences of racial discrimination since they share the same racial phenotypes and appear as a racial minority in society (J. Kim, Suh, & Heo, 2014; R. M. Lee, 2003), However, we expected that adopted Korean American adolescents compared to non-adopted Korean American adolescents would receive fewer racial and ethnic socialization messages from their White parents, since White parents are less likely to have firsthand experiences as a racial minority or have grown up with a Korean culture (Else-Quest & Morse, 2015). Moreover, we expected racial discrimination (as a risk factor) would negatively correlate with school adjustment and racial and ethnic socialization (as protective factors) would positively correlate with school adjustment. Given the recent research findings for racial socialization (Frabutt et al., 2002), we hypothesized a positive linear relationship between ethnic socialization and school adjustment, and a curvilinear relationship between racial socialization and school adjustment. We expected moderate amounts of racial socialization messages would positively correlate with school adjustment, while both low and high amounts of racial socialization messages would negatively correlate with school adjustment. Similarly, we hypothesized ethnic socialization would buffer the effects of racial discrimination on school adjustment, and racial socialization would curvilinearly moderate the effects of racial discrimination on school adjustment. We expected moderate amounts of racial socialization messages would attenuate, while both low and high amounts of messages would exacerbate the racial discrimination—school adjustment link. We did not make any hypotheses on group differences of these relationships given the limited research in this area, although they were tested for exploratory purposes.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The sample consisted of 401 Korean American adolescents drawn from two separate studies conducted between 2007 - 2009. The adopted Korean American dataset was drawn from a larger study on Korean youth who were adopted transnationally through agencies in Minnesota (J. P. Lee, Lee, Hu, & Kim, 2014). Inclusion required that Korean adoptees were in teenage years from 12 to 18 years old from transracial families with White adoptive parents. We only included adopted Korean American adolescents with White parents because the purpose of this was to investigate racial and ethnic socialization practice done in transracial adoptive families and 95% of adopted Korean American adolescents’ parents were White. The final sample consisted of 233 transracially adopted Korean American adolescents (M age = 15.36, SD = 1.72, 48.5% male). Among 230 participants who provided data on age at adoption, the mean age at adoption was 7.33 months (SD = 6.34).

The non-adopted Korean American dataset was drawn from a study on the adjustment of Korean American adolescents from immigrant families. This data consisted of 161 Korean American adolescents from Midwest and on the East Coast (Seol & Lee, 2012). Five participants who filled out the survey in Korean and one who was identified as European American were excluded from analyses. The final sample consisted of 155 Korean American adolescents (M age = 14.81, SD = 1.85, 51% male). Seventy-seven adolescents participated from Minnesota, 22 from Indiana and 56 from Washington D.C. In order to examine group differences in main variables by region, we conducted t-tests dividing adolescents into two groups, East coast (i.e., Washington D.C.) vs. Mid-West (i.e., Minnesota and Indiana). We did not find any significant group differences in our main variables. None of the 155 participants were identified as being adoptees. Among 154 participants who provided data on ethnicity of their parents, all participants indicated that their parents are Korean except one participant who identified her father’s ethnicity as White. Regarding generation status, 92 were U.S.-born and 63 were foreign-born. The mean age at the time of migration to the U.S. was 7.02 years (SD = 4.68) for foreign-born participants.

Measures

Racial Discrimination

Racial discrimination was measured using nine items developed for the adopted Korean American study (J. P. Lee et al., 2014), which assesses subtle forms of discrimination that are commonly experienced by Korean Americans. These items examined general perceptions of denigration due to racial/ethnic differences in the past year (e.g., “I have overheard people make rude or insensitive ethnic and racial comments about minorities”). They are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often), with higher scores representing higher levels of racial discrimination. In support of validity and reliability of the measure, J. P. Lee et al. (2014) found that this measure significantly correlated with internalizing problems (r = .33, p < .01), externalizing problems (r = .35, p < .01), and substance use (r = .19, p < .05) among adopted Korean American youths. The internal reliability estimates (α) for this measure was .87. In this study, the mean item score of Racial Discrimination was 1.95 (SD = .57) for adopted Korean American, and 2.47 (SD = .65) for non-adopted with internal reliability estimates (α) of .86 for adopted Korean American, .85 for non-adopted Korean American, and .88 for the total group.

Racial and Ethnic Socialization

Racial and ethnic socialization was measured using 13 items of Perceived Ethnic-Racial Socialization measure, which assesses perceived past-year ethnic-racial socialization practices from the perspective of the adolescent (Tran & Lee, 2010). Tran and Lee (2010) modified Hughes and Johnson (2001)’s Ethnic-Racial Socialization Scale that were originally developed for African Americans and validated it with Asian American adolescents. Similar to the Hughes and Johnson’s measure, Tran and Lee identified 3 subscales, including Cultural Socialization/Pluralism, Preparation for Bias, and Promotion of Mistrust. Racial Socialization was measured using the eight-item Preparation for Bias subscale, which assesses the frequency of parental messages promoting awareness of racial bias and discrimination (e.g., talking about racial stereotypes, prejudice, and/or discrimination against Koreans and Asians in general). Ethnic Socialization was measured using the five-item Cultural Socialization/Pluralism subscale, which assesses the frequency of parental messages emphasizing ethnic pride, culture, heritage and diversity (e.g., talking about important Korean people or historical events). These items were rated on a 5-point rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often), with higher scores representing higher levels of Racial and Ethnic Socialization. In Tran and Lee (2010)’s study, the internal reliability estimates (α) for Racial Socialization was .85, and for Ethnic Socialization was .80. In this study, the mean item score of Racial Socialization was 1.66 (SD = .62) for adopted Korean American, and 2.33 (SD = .82) for non-adopted Korean American with internal reliability estimates (α) of .84 for adopted Korean American, .82 for non-adopted Korean American, and .85 for total group. The mean item score of Ethnic Socialization was 2.26 (SD = .82) for adopted Korean American, and 2.63 (SD = .86) for non-adopted Korean American with internal reliability estimates (α) of .77 for adopted Korean American, .73 for non-adopted Korean American, and .75 for the total group.

School Adjustment

School Adjustment was measured using eight items from Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) Measure of Student Engagement (Adams & Wu, 2003). The PISA Measure of Student Engagement consists of two subscales, including Sense of Belonging and Participation. The six-item Sense of Belonging subscale assesses how much adolescents feel like they belong to their school (e.g., “I feel like I belong when I am at school”). The two-item Participation subscale assesses how much adolescents are motivated and interested in their school (e.g., “I do not want to go to school”). These items were rated on a 5-point rating scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with higher scores representing higher levels of school adjustment. We used the original six-item Sense of Belonging subscale to assess School Belonging of Korean American adolescents in this study. We assessed School Engagement in this study using the original two-item Participation subscale and added three additional items (i.e., “I want to do well at school,” “I take school seriously,” “I pay attention in class”).

In order to ascertain whether the PISA Measure of Student Engagement and three added items properly yield two factors—School Belong and School Engagement, we performed factor analyses. We randomly divided the total sample into two equally sized groups. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted on the two samples separately. Results of a maximum-likelihood exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotation and parallel analysis on 11 items supported the hypothesized two-factor model, resulting in a two-factor solution accounting for 55.75% of the variance. Two factors with an Eigen value of > 1 emerged with all items of factor loading higher than .39. Using Hu and Bentler’s (1999) criteria of fit, results of confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 18.0 also verified a fair fit of the two-factor structure: χ2(43, N = 194) = 98.263, p < .001, root-mean-square error of approximation = .082, 90% CI [.06, .103], standardized root-mean-square residual = .077, comparative fit index = .925, and incremental fit index = .928. Factor loading ranges were .63-.81 for School Belonging, and .41-.73 for School Engagement. In our sample, these measures of School Belonging and School Engagement were moderately related (r = .36).

In national data provided by Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) PISA report, the internal reliability estimates (α) for School Belonging was .86 when applied to U.S. adolescents aged from 15 to 16 (Adams & Wu, 2003). The internal reliability estimates of Participation were not reported by PISA. The mean item score of School Belonging was 3.38 (SD = .50) for adopted Korean American, and 3.21 (SD = .50) for non-adopted Korean American with internal reliability estimates (α) of .88 for adopted Korean American, .82 for non-adopted Korean American, and .86 for the total group. The mean item score of School Engagement was 3.18 (SD = .47) for adopted Korean American, and 3.05 (SD = .48) for non-adopted Korean American with internal reliability estimates (α) of .77 for adopted Korean American, .70 for non-adopted Korean American, and .73 for the total group.

Results

Table 1 presents the correlation matrix for all the study variables. For both adopted and non-adopted Korean American groups, Racial Discrimination was significantly and negatively correlated with School Belonging and School Engagement. Racial Socialization was not significantly correlated with School Belonging and School Engagement. Ethnic Socialization was significantly and positively correlated with School Engagement, but not with School Belonging. For the adopted Korean American group, Age was significantly and negatively correlated with School Belonging. For the non-adopted Korean American group, Age was significantly and negatively correlated with School Belonging and School Engagement. For both groups, Gender (0 = male, 1 = female) was significantly and positively correlated with School Engagement. We elected to control for Age and Gender in our main moderation analyses as they correlated with our dependent variables (Jaccard, Guilamo-Ramos, Johansson, & Bouris, 2006). Table 2 presents mean group differences of main study variables between both groups of adolescents. Consistent with our hypothesis, non-adopted Korean American adolescents reported significantly higher levels of Racial Socialization (t = −8.86, p < .001), and Ethnic Socialization (t = −4.12, p < .001) than adopted Korean American adolescents. Inconsistent with our hypothesis, non-adopted Korean American adolescents also reported a significantly higher level of Racial Discrimination than adopted Korean American adolescents (t = −7.91, p < .001).

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations of Main Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | .03 | .14* | −.09 | −.06 | −.16* | −.04 |

| 2. Gender | .04 | — | −.07 | −.07 | .04 | .02 | .19** |

| 3. Racial Discrimination | .13 | −.15 | — | .25** | .07 | −.31** | −.18** |

| 4. Racial Socialization | −.05 | −.00 | .25** | — | .71** | −.07 | .06 |

| 5. Ethnic Socialization | −.21* | .12 | −.00 | .55** | — | .07 | .16* |

| 6. School Belonging | −.23** | .01 | −.28** | −.05 | .14 | — | .33** |

| 7. School Engagement | −.18* | .17* | −.31** | −.08 | .23** | .34** | — |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Correlations above the diagonal are for adopted Korean American youths, and correlations below the diagonal are for non-adopted Korean American youths.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Main Study Variables by Adoption Status

| Variable | Adopted Korean American Youths Mean (SD) | Non-adopted Korean American Youths Mean (SD) | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Racial Discrimination | 1.95 (.57) | 2.47 (.65) | −7.91*** |

| Racial Socialization | 1.66 (.62) | 2.33 (.82) | −8.86*** |

| Ethnic Socialization | 2.26 (.82) | 2.63 (.86) | −4.12*** |

| School Belonging | 3.38 (.50) | 3.21 (.50) | 3.33** |

| School Engagement | 3.18 (.47) | 3.05 (.48) | 2.68** |

Note.

p < .01,

p < .001.

Hierarchical regression analyses were used to test the hypothesized main and interaction effects. In specific, Aiken and West’s (1991) statistical procedure was employed to examine moderating roles of Racial Socialization and Ethnic Socialization on the relationship between Racial Discrimination and School Adjustment (i.e., School Belonging and School Engagement. All continuous predictors were centered to reduce multicollinearity between the main effect and interaction terms (Aiken & West, 1991). Total of four hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed with School Belonging and School Engagement as dependent variables (see Table 3–6). The statistical significance level was set at p < .05, and the Bonferroni method was used to adjust the p values for multiple regression analyses (p < .05/4 = .0125; corrected for 4 analyses).

Table 3.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Predicting School Belonging from Adoption Status, Racial Discrimination, and Racial Socialization

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β |

| (Constant) | 1.34**(.45) | 1.39**(.44) | 1.37**(.45) | 1.41**(.46) | ||||

| Age | −.09**(.03) | −.16 | −.08**(.03) | −.15 | −.08**(.03) | −.15 | −.09**(.03) | −.15 |

| Gender | .05 (.11) | .03 | −.02 (.10) | −.01 | −.02 (.10) | −.01 | −.02 (.10) | −.01 |

| Adoption Status | −.16 (.12) | −.08 | −.17 (.15) | −.09 | −.20 (.15) | −.10 | ||

| Racial Discrimination | −.30***(.06) | −.30 | −.33***(.09) | −.33 | −.35**(.12) | −.35 | ||

| Racial Socialization | .06 (.07) | .06 | .00 (.09) | .00 | −.02 (.09) | −.02 | ||

| Racial Socialization2 | −.07 (.04) | −.10 | −.07 (.09) | −.11 | −.04 (.09) | −.06 | ||

| Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination | .13 (.13) | .08 | .16 (.15) | .10 | ||||

| Adoption Status x Racial Socialization | .19 (.16) | .13 | .14 (.16) | .10 | ||||

| Adoption Status x Racial Socialization 2 | −.02 (.12) | −.03 | −.01 (.12) | −.01 | ||||

| Discrimination x Racial Socialization | −.01 (.08) | −.01 | −.13 (.10) | −.14 | ||||

| Discrimination x Racial Socialization 2 | −.03 (.05) | −.07 | −.06 (.12) | −.12 | ||||

| Adoption Status x Discrimination x | .31(.17) | .28 | ||||||

| Racial Socialization | ||||||||

| Adoption Status x Discrimination x Racial Socialization 2 | −.05 (.14) | −.11 | ||||||

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Table 6.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Predicting School Engagement from Adoption Status, Racial Discrimination, and Ethnic Socialization

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β |

| (Constant) | .51(.44) | .37 (.44) | .36 (.45) | .36 (.45) | ||||

| Age | −.05 (.03) | −.08 | −.03 (.03) | −.05 | −.03 (.03) | −.05 | −.03 (.03) | −.05 |

| Gender | .37***(.10) | .18 | .29**(.10) | .14 | .29**(.10) | .14 | .29**(.10) | .14 |

| Adoption Status | −.18 (.11) | −.09 | −.17 (.11) | −.08 | −.17 (.11) | −.08 | ||

| Racial Discrimination | −.24***(.05) | −.24 | −.21**(.08) | −.21 | −.21**(.08) | −.21 | ||

| Ethnic Socialization | .18***(.05) | .18 | .16*(.07) | .16 | .16*(.07) | .16 | ||

| Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination | −.06 (.11) | −.04 | −.06 (.11) | −.04 | ||||

| Adoption Status x Ethnic Socialization | .05 (.11) | .03 | .05 (.11) | .03 | ||||

| Racial Discrimination x Ethnic Socialization | −.04 (.06) | −.03 | −.04 (.08) | −.04 | ||||

| Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination x | .00 (.11) | .00 | ||||||

| Ethnic Socialization | ||||||||

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

For Racial Socialization models, a squared term of Racial Socialization (i.e., Racial Socialization2) was used to assess its curvilinear relationship with School Adjustment and its interaction with Racial Discrimination and group’s Adoption Status (0 = adopted Korean American adolescents, 1 = non-adopted Korean American adolescents) (Harris-Britt, et al., 2007) on School Adjustment. Step 1 included Age and Gender as covariates (0 = male, 1 = female). Step 2 included Adoption Status, Racial Discrimination, Racial Socialization, and Racial Socialization2 to test for main effects. A significant Racial Socialization2 on School Adjustment would suggest the curvilinear relation between Racial Socialization and School Adjustment. Step 3 included Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination, Adoption Status x Racial Socialization, Adoption Status x Racial Socialization2, Racial Discrimination x Racial Socialization, and Racial Discrimination x Racial Socialization2 to test for two-way interaction effects. A significant Racial Discrimination x Racial Socialization2 on School Adjustment would suggest that the linear relation between Racial Discrimination and School Adjustment varies across levels of Racial Socialization. Step 4 included Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination x Racial Socialization, and Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination x Racial Socialization2 to test for the three-way interaction effect. A significant Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination x Racial Socialization2 would suggest that the two-way interaction between Racial Discrimination and Racial Socialization on School Adjustment differs based on Adoption Status. Two Racial Socialization models were tested on School Belonging and School Engagement as dependent variables.

For Ethnic Socialization models, Step 1 included Age and Gender as covariates. Step 2 included Adoption Status, Racial Discrimination, and Ethnic Socialization to test for main effects. Step 3 included Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination, Adoption Status x Ethnic Socialization, and Racial Discrimination x Ethnic Socialization to test for two-way interaction effects. Step 4 included Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination x Ethnic Socialization to test for a three-way interaction effect. Two Ethnic Socialization models were tested on School Belonging and School Engagement as dependent variables. To probe significant interaction effects in the Ethnic Socialization models, simple slope analyses were performed to determine whether the slope of Racial Discrimination on School Adjustment was significantly different from zero when the conditional value for Ethnic Socialization was high or low (Aiken & West, 1991). Regression slopes of significant three-way interaction were also plotted using predicted values for low and high Ethnic Socialization on low and high Racial Discrimination, but they were graphed separately for adopted and non-adopted Korean American adolescents.

Adoption Status, Racial Socialization, and Racial Discrimination on School Adjustment

School Belonging

In Step 1, the covariates were significantly associated with School Belonging (R2 = .03), F (2, 357) = 4.80, p < .0125. Specifically, Age was negatively associated with School Belonging, controlling for Gender. In Step 2, consistent with the hypothesis, the incremental main effect on School Belonging was statistically significant (R2 = .14; ΔR2 = .12), F (6, 353) = 9.75, p < .0125. Specifically, Racial Discrimination was negatively associated with School Belonging, controlling for Adoption Status, Racial Socialization, and Racial Socialization2. In Step 3, the incremental effect of the set of two-way interaction terms on School Belonging was not statistically significant (R2= .15; ΔR2= .01), F (11, 348) = 5.65, p = .58. In Step 4, the incremental effect of the set of three-way interaction terms on School Belonging was not statistically significant (R2= .16; ΔR2= .01), F (13, 346) = 5.06, p = .18 (see Table 3).

School Engagement

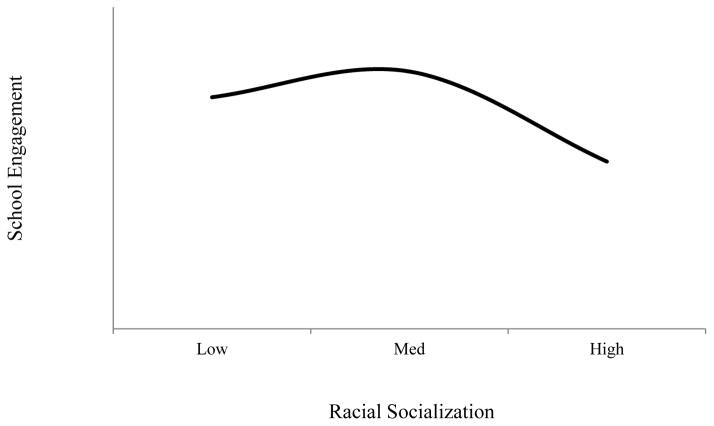

In Step 1, the covariates were significantly associated with School Engagement (R2 = .04), F (2, 358) = 7.27, p < .0125. Specifically, Gender was positively associated with School Engagement, controlling for Age. In Step 2, consistent with the hypothesis, the incremental main effect on School Engagement was statistically significant (R2 = .12; ΔR2 = .08), F (6, 354) = 8.09, p < .0125. Specifically, Racial Discrimination was negatively associated with School Engagement, controlling for Adoption Status, Racial Socialization, and Racial Socialization2. Also, Racial Socialization was positively associated with School Engagement, controlling for Adoption Status, Racial Discrimination, and Racial Socialization2. Racial Socialization2 was negatively associated with School Engagement, indicating that the linear relation between Racial Socialization and School Engagement increased, then curved downward, similar to an upside-down U. Thus, when Racial Socialization levels were low and high, School Engagement was low; when Racial Socialization levels were moderate, School Engagement was high (see Figure 1). In Step 3, the incremental effect of the set of two-way interaction terms on School Engagement was not statistically significant (R2 = .12; ΔR2 = .00), F (11, 349) = 4.50, p = .92. In Step 4, the incremental effect of the set of three-way interaction terms on School Engagement was not statistically significant (R2 = .12; ΔR2 = .00), F (13, 347) = 3.79, p = .96 (see Table 4).

Figure 1.

Curvilinear relationship between Racial Socialization and School Engagement.

Table 4.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Predicting School Engagement from Adoption Status, Racial Discrimination, and Racial Socialization

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β |

| (Constant) | .51(.45) | .53(.45) | .56(.46) | .58 (.47) | ||||

| Age | −.05 (.03) | −.08 | −.03(.03) | −.06 | −.04(.03) | −.06 | −.04 (.03) | −.07 |

| Gender | .37***(.11) | .18 | .31**(.10) | .15 | .31**(.10) | .15 | .31**(.10) | .15 |

| Adoption Status | −.15 (.12) | −.07 | −.18 (.15) | −.09 | −.19 (.15) | −.09 | ||

| Racial Discrimination | −.25***(.06) | −.25 | −.19*(.09) | −.19 | −.21(.12) | −.21 | ||

| Racial Socialization | .15*(.07) | .15 | .16 (.09) | .16 | .15 (.09) | .15 | ||

| Racial Socialization 2 | −.10*(.04) | −.15 | −.10 (.09) | −.15 | −.10 (.10) | −.15 | ||

| Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination | −.02 (.13) | − .02 | .00 (.16) | .00 | ||||

| Adoption Status x Racial Socialization | −.02 (.16) | −.01 | −.02 (.16) | −.01 | ||||

| Adoption Status x Racial Socialization 2 | .04 (.12) | .06 | .05 (.12) | .07 | ||||

| Racial Discrimination x Racial Socialization | .02 (.08) | .02 | .02 (.11) | .03 | ||||

| Racial Discrimination x Racial Socialization2 | −.05 (.05) | −.11 | −.02 (.12) | −.04 | ||||

| Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination x | .00 (.17) | .00 | ||||||

| Racial Socialization | ||||||||

| Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination x Racial Socialization2 | −.04 (.14) | −.08 | ||||||

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Adoption Status, Ethnic Socialization, and Racial Discrimination on School Adjustment

School Belonging

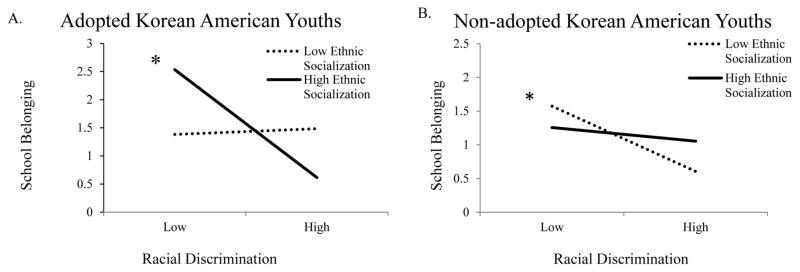

In Step 1, the covariates were significantly associated with School Belonging (R2 = .03), F (2, 364) = 4.89, p < .0125. Specifically, Age was negatively associated with School Belonging, controlling for Gender. In Step 2, consistent with the hypothesis, the incremental main effect on School Belonging was statistically significant (R2 = .15; ΔR2 = .12), F (3, 361) = 12.23, p < .0125. Specifically, Racial Discrimination was negatively associated with School Belonging, controlling for Adoption Status and Ethnic Socialization. In Step 3, the incremental effect of the set of 2 two-way interaction terms on School Belonging was not statistically significant (R2 = .15; ΔR2 = .00), F (3, 358) = 7.71, p = .84. In Step 4, the incremental effect of the three-way interaction term on School Belonging was statistically significant (R2 = .17; ΔR2 = .02), F (1, 356) = 8.90, p < .0125. In particular, there was a significant three-way interaction between Adoption Status, Racial Discrimination, and Ethnic Socialization on School Belonging (β = .35, SE = .11, sr2 = .02, p < .05) (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Predicting School Belonging from Adoption Status, Racial Discrimination, and Ethnic Socialization

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β | B (SE B) | β |

| (Constant) | 1.34**(.44) | 1.28**(.44) | 1.25**(.44) | 1.31**(.44) | ||||

| Age | −.09**(.03) | −.16 | −.08**(.03) | −.14 | −.08**(.03) | −.14 | −.08**(.03) | −.15 |

| Gender | .05 (.10) | .03 | −.03 (.10) | −.01 | −.03 (.10) | −.01 | −.02 (.10) | −.01 |

| Adoption Status | −.19(.11) | −.09 | −.20(.11) | −.10 | −.19(.11) | −.10 | ||

| Racial Discrimination | −.30***(.05) | −.30 | −.35***(.07) | −.35 | −.37***(.07) | −.37 | ||

| Ethnic Socialization | .10(.05) | .10 | .09 (.07) | .09 | .05 (.07) | .05 | ||

| Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination | .09 (.11) | .06 | .08 (.11) | .05 | ||||

| Adoption Status x Ethnic Socialization | .03 (.11) | .02 | −.02 (.11) | −.01 | ||||

| Racial Discrimination x Ethnic Socialization | −.00 (.06) | −.00 | −.16*(.07) | −.15 | ||||

| Adoption Status x Racial Discrimination x | .35**(.11) | .23 | ||||||

| Ethnic Socialization | ||||||||

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

For adopted Korean American adolescents, simple slope analyses found that the slope for Racial Discrimination on School Belonging was significantly different from zero when the conditional value for Ethnic Socialization was high, t = −3.76, p < .001, and it was not significantly different from zero when the conditional value for Ethnic Socialization was low, t = .07, ns (see Figure 2). As illustrated in Figure 2A, adopted Korean American adolescents who received high levels of Ethnic Socialization reported less School Belonging when they perceived high levels of Racial Discrimination than when they perceived low levels of Racial Discrimination. For non-adopted Korean American adolescents, simple slope analyses found that the slope for Racial Discrimination on School Belonging was not significantly different from zero when the conditional value for Ethnic Socialization was high, t = −1.33, ns, and it was significantly different from zero when the conditional value for Ethnic Socialization was low, t = −3.73, p < .001. As illustrated in Figure 2B, non-adopted Korean American adolescents who received low levels of Ethnic Socialization reported less School Belonging when they perceived high levels of Racial Discrimination than when they perceived low levels of Racial Discrimination. In sum, post hoc data analyses suggest that the exacerbating effect of high Ethnic Socialization seemed more relevant to adopted Korean American adolescents than it did to non-adopted Korean American adolescents (as seen in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ethnic Socialization moderates Racial Discrimination and School Belonging. * p < .001.

School Engagement

In Step 1, the covariates were significantly associated with School Engagement (R2 = .04), F (2, 365) = 7.41, p < .0125. Specifically, Gender was positively associated with School Engagement, controlling for Age. In Step 2, consistent with the hypothesis, the incremental main effect on School Engagement was statistically significant (R2 = .13; ΔR2 = .09), F (3, 362) = 11.14, p < .0125. Specifically, Racial Discrimination was negatively associated with School Engagement, controlling for Adoption Status and Ethnic Socialization. Also, Ethnic Socialization was positively associated with School Engagement, controlling for Adoption Status and Racial Discrimination. In Step 3, the incremental effect of the set of 2 two-way interaction terms on School Engagement was not statistically significant (R2 = .14; ΔR2 = .00), F (3, 359) = 7.04, p = .81. In Step 4, the incremental effect of the three-way interaction term on School Engagement was not statistically significant (R2 = .14; ΔR2 = .00), F (1, 358) = 6.24, p = .98 (see Table 6).

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between racial discrimination, racial and ethnic socialization experiences, and school adjustment of adopted and non-adopted Korean American adolescents. We found mixed support for our hypotheses. As hypothesized, racial discrimination was negatively correlated with school adjustment for both groups. Racial socialization was curvilinearly associated with school adjustment for both groups, with moderate level of racial socialization predicting positive school adjustment, and low and high levels of racial socialization predicting negative school adjustment. The hypothesized moderation effect of ethnic socialization differed by groups. Ethnic socialization exacerbated the link between perceived racial discrimination and school belongingness for adopted Korean American adolescents. However, ethnic socialization buffered the link for non-adopted Korean American adolescents.

Inconsistent with our hypothesis, non-adopted Korean American adolescents reported perceiving more racial discrimination than adopted Korean American adolescents, although we assumed experiences of racial discrimination for both groups would be comparable given their shared racial phenotypes and the literature highlighting frequent encounters of racism for both groups (Cederblad et al., 1999; Gee et al., 2009; J. P. Lee et al., 2014). It is possible that non-adopted Korean American adolescents were simply exposed to more instances of racism than adopted Korean American adolescents. Alternatively, the difference may lie within the perceptions of racial discrimination than actual encounters of racial discrimination. In our sample, non-adopted Korean American youths may have more developed ethnic-racial identities and more racial socialization experiences—both noted to increase sensitivity and awareness of racism (Alvarez, Juang, & Liang, 2006; Hughes & Chen, 1999). Studies with African American families revealed that parental racial socialization was correlated not only with parents’ own racial discrimination experiences but also with their children’s (Hughes & Johnson, 2001; Hughes & Chen, 1997). Although Korean parents may differ from African American parents, it is possible that more frequent experiences of racism among non-adopted Korean American adolescent families motivates Korean parents to racially socialize their children, which in turn, helps non-adopted Korean American adolescents to identify racial discriminating experiences more than their adopted Korean American counterparts. Consistent with our hypothesis, non-adopted Korean American adolescents reported higher levels of racial and ethnic socialization than adopted Korean American adolescents. As expected, adopted Korean American adolescents may have less opportunities, exposures, and discussions with their White families in learning about what it means to be Korean or how to deal with experiences of racism (Berbery & O’Brien, 2011; Docan-Morgan, 2010; R. M. Lee, 2003).

Despite these group differences, consistent with our hypotheses, racial discrimination was negatively related to school belonging and school engagement, and ethnic socialization was positively related to school engagement for both adopted and non-adopted Korean American adolescents. These findings are consistent with the literature that suggest deleterious effects of racism (Gee et al., 2009; J. P. Lee et al., 2014; Yoo et al., 2010) and protective effects of ethnic socialization (Brown & Ling, 2012; Huynh & Fuligni, 2008; Liu & Lau, 2013) in the lives of Asian Americans. The protective effect of racial socialization and its relationship to school adjustment was more complex. Consistent with our hypothesis, racial socialization had a curvilinear relationship with school engagement for both groups, with moderate level of racial socialization predicting positive school engagement, while low and high levels of racial socialization predicting negative school engagement. Our results support the thesis that moderate amounts of racial socialization may be necessary for healthy adjustment of racial minority youths, yet little to no racial socialization may leave them ill-prepared and too much of it may leave them overwhelmed and feeling inadequate to overcome racism (Harris-Britt et al., 2007; Hughes & Johnson, 2001; Marshall, 1995).

Racial socialization did not moderate the relationship between racial discrimination and school adjustment for both adopted and non-adopted Korean American youths. It is possible that for Korean Americans, the role of ethnic socialization and emphasis on Korean traditions, values, and behaviors may be more relevant than racial socialization when coping with racism. It is also possible that Korean American parents (regardless of whether they are White or Korean immigrants) are less likely to engage in specific discussions and instructions in preparing their children to deal with racial stereotypes and racism (Else-Quest & Morse, 2015)—possibly due to limited first-hand experiences with racism or time in processing best coping methods. Racial socialization practices might be different for Korean American families that were not properly assessed with our racial socialization measure. In particular, our general measure of racial socialization assessed whether parents broadly talked to their children about racial stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. However, specific types of conversations or activities for handling pervasive model minority or perpetual foreigner stereotypes unique to Korean Americans were not assessed. Moreover, culturally congruent racial socialization strategies such as possibly indirect communications or other activities were not measured.

Ethnic socialization moderated the relationship between racial discrimination and school belonging, although it varied between adopted and non-adopted Korean American adolescents. Ethnic socialization buffered the effects of racial discrimination on school belonging for non-adopted Korean American youths, while it exacerbated the effects of racial discrimination on school belonging for adopted Korean American youths. In other words, instilled messages of ethnic pride, history, and values seemed to help non-adopted Korean American youths more effectively cope with racial discrimination, which is similar to the few results found with African American adolescents (Harris-Brit et al., 2007; Wang & Huguley, 2012). However, these same messages seemed to worsen the effects of racial discrimination for adopted Korean American adolescents. There are several possibilities for this mixed finding in the role of ethnic socialization.

The first possibility may be attributed to different levels of ethnic identity between adopted and non-adopted Korean American groups. It is possible that our sample of transracial adopted youths have more insecure or lower Korean ethnic identity that may impede the adaptive function of ethnic socialization. Studies have found that ethnic socialization was positively related to ethnic identity, which in turn, was related to psychological well-being of Asian Americans (Brown & Ling, 2012; Choi et al., 2014; Gartner et al., 2014; Tran & Lee, 2010). Consequently, the buffering or exacerbative moderation effect of ethnic socialization on racial discrimination for adopted and non-adopted Korean American adolescents may be further mediated or explained by different levels of ethnic identity. Alternatively, it is possible that our sample of transracial adopted youths raised by White families have a greater affinity or group orientation towards mainstream, White American culture. Freidlander and colleagues (2000), for instance, found transracial adoptees were more likely to identify themselves as European Americans and expressed more ambivalent attitudes toward racial and ethnic socialization. Accordingly, adopted Korean American adolescents who identify with more White American culture may find messages of Korean pride, history, and values incongruent with their social identity, thus exacerbating the effects of racism.

The second possibility may be attributed to the different meaning and properties attached to ethnic socialization between adopted and non-adopted Korean American groups. For adopted Korean American youths, ethnic socialization focusing on Korean culture may be a reminder of the difference between them and their White family. Consequently, ethnic socialization may further validate differences already experienced when facing racial discrimination, thus decreasing belongingness and increasing isolation and marginalization. In fact, studies have shown that limited, superficial types of ethnic socialization activities, such as kids participating in culture camps or visiting Korean restaurants, can actually create emotional and psychological distance between adopted Korean American youths and their families (O. M. Kim et al., 2013; Randolph & Holdzman, 2010). Alternatively, ethnic socialization experienced by adopted Korean American youths may not promote enough meaningful, cultural competency skills that are helpful when dealing with racial discrimination. For instance, Choi and colleagues (2014) found that Korean language proficiency mediated the link between ethnic socialization and depression among Korean American adolescents. It is possible that there are certain properties of ethnic socialization that may be more helpful than others when coping with racism.

Limitations and Implications

There are a few limitations in the current study. First, our study is cross-sectional and causal inferences made in the relationship between racial and ethnic socialization, racial discrimination, and school adjustment should be read with caution. For instance, our results similarly suggest that individuals with lower school adjustment are going to perceive more racial discrimination and less ethnic socialization messages from their parent(s). Future research should implement experimental and longitudinal designs that better captures the directionality of these relationships. Second, our measure of racial socialization in particular used in this study may not be best suited for this population. Hughes and Johnson’s (2001) measure of racial and ethnic socialization is a popular measure, though very general in description of items. Consequently, the specific details and process of racial socialization based on the unique experiences of racial stereotypes and discrimination faced by Asian Americans is not clear. Given the limited research in this area, future research should qualitatively explore the exact meaning and process of racial socialization and quantitatively construct more valid and reliable measures of racial socialization specific to Asian American lives. Third, additional within-group analyses are warranted in understanding when and how the relationship between racial and ethnic socialization, racial discrimination, and school adjustment may vary across different groups of Asian Americans. For instance, our study highlighted the many differences between adopted and non-adopted Korean American adolescents. The complexities of these relationships may further vary by generational status, socioeconomic statuses, and community settings, since experiences and coping process of racial discrimination do vary by the individual’s ecological contexts (Harrell, 2000).

In summary, our study contributes to a sorely needed area of research that focuses on the experience and psychological consequences of racial and ethnic socialization practiced in Asian American families. It specifically examines a unique interactive effect between racial discrimination, racial and ethnic socialization, and school adjustment in a sample of adopted and non-adopted Korean American adolescents. Our findings highlight the complex differences and relationships of racial and ethnic socialization within Asian American families. It suggests, even though adopted Korean American adolescents reported lower levels of racial discrimination, racial socialization, and ethnic socialization than non-adopted Korean American adolescents, racial discrimination was negatively related to school adjustment, and ethnic socialization was positively related to school adjustment for both groups. Racial socialization also demonstrated to produce a complex curvilinear relationship with school adjustment with moderate amounts of racial socialization best predicting school adjustment. Finally, the process of instilled messages of Korean pride, history, and values had a differential effect for adopted and non-adopted Korean Americans when specifically coping with racism. Undoubtedly, the process and outcome of racial and ethnic socialization for Asian American families are nuanced and intricate that significantly varies by the individual’s ecology.

The study findings have implications for both intervention and prevention. Practitioners and parents should be aware that racial discrimination has negative effects on Korean American adolescents. Proper racial and ethnic socialization appear to mitigate negative effects of racial discrimination. However, the current study suggests that racial and ethnic socialization may be practiced differently according to Korean American adolescents’ cultural context in the home. Ethnic socialization in particular seems to be critical to non-adopted Korean American adolescents’ adjustment when these individuals’ cultural identification is in line with Korean culture. Facilitating Korean parents develop more effective ethnic socialization strategies may help Korean American adolescents better adapt to their own discrimination experiences, and adjustment. It may be premature to conclude that adopted Korean American adolescents would not receive benefits from ethnic socialization messages in the face of discrimination. Rather, emotional reactions and cognitive meanings of receiving ethnic socialization messages need to be processed first. Such messages might lead adopted Korean American adolescents to feel alienated from other family members by highlighting differences between adopted adolescents and their parents. In terms of racial socialization, proper levels of race related messages such as racial barriers and possible discrimination due to race appears to be a more critical consideration regardless of racial and ethnic background of Korean American adolescents’ family. Too little or too much of messages on racism and racial barriers may discourage Korean American adolescents in school, and consequently interfere with their academic adjustment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant from National Institute of Mental Health (K01 MH070740) to Richard M. Lee.

References

- Adams R, Wu M. PISA 2000 Technical Report. Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez AN, Juang L, Liang CTH. Asian Americans and racism: When bad things happen to “model minorities”. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12(3):477–492. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basow SA, Lilley E, Bookwala J, McGillicuddy-DeLisi A. Identity development and psychological well-being in Korean-born adoptees in the U.S. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(4):473–480. doi: 10.1037/a0014450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Kim SY. Experiences of discrimination among Chinese American adolescents and the consequences for socioemotional and academic development. Developmental Psychology. 2009a;45(6):1682–1694. doi: 10.1037/a0016119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbery M, O’Brien K. Predictors of White adoptive parents’ cultural and racial socialization behaviors with their Asian adopted children. Adoption Quarterly. 2011;14(4):284–304. [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist KJS, Campbell ME, Unrau YA. Caucasian parents and Korean adoptees: A survey of parents' perceptions. Adoption Quarterly. 2003;6(4):41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein KS, Park SY, Shin J, Cho S, Park Y. Acculturation, discrimination and depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants in New York City. Community mental health journal. 2011;47(1):24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9261-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks D, Barth RP. Adult transracial and inracial adoptees: Effects of race, gender, adoptive family structure, and placement history on adjustment outcomes. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1999;69(1):87–99. doi: 10.1037/h0080384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CM, Ling W. Ethnic-racial socialization has an indirect effect on self-esteem for Asian American emerging adults. Psychology. 2012;3(1):78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MOB, O’Campo PJ, Randolph SM, Nickerson K. The influence of racial socialization practices on the cognitive and behavioral competence of African American preschoolers. Child Development. 2002;73(5):1611–1625. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederblad M, Höök B, Irhammar M, Mercke A. Mental health in international adoptees as teenagers and young adults. An epidemiological study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40(8):1239–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim YS. Acculturation and the family: Core vs. peripheral changes among Korean Americans. Journal of Studies of Koreans Abroad. 2010;21:135– 190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim YS, Pekelnicky DD, Kim HJ. Preservation and modification of culture in family socialization: Development of parenting measures for Korean immigrant families. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2013;4(2):143–154. doi: 10.1037/a0028772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Tan KPH, Yasui M, Pekelnicky DD. Race–ethnicity and culture in the family and youth outcomes: Test of a path model with Korean American youth and parents. Race and Social Problems. 2014;6(1):69–84. doi: 10.1007/s12552-014-9111-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker TR, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Grunbaum JA, Schwebel DC, Gilliland MJ, et al. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination among fifth-grade students and its association with mental health. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(5):878–884. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docan-Morgan S. Korean adoptees' retrospective reports of intrusive interactions: Exploring boundary management in adoptive families. Journal of Family Communication. 2010;10(3):137–157. [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Morse E. Ethnic variations in parental ethnic socialization and adolescent ethnic identity: A longitudinal study. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2015;21(1):54–64. doi: 10.1037/a0037820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faircloth BS, Hamm JV. Sense of belonging among high school students representing 4 ethnic groups. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34(4):293–309. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AR, Shaw CM. African Americans’ mental health and perceptions of racist discrimination: The moderating effects of racial socialization experiences and self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46(3):395–407. [Google Scholar]

- Frabutt JM, Walker AM, MacKinnon-Lewis C. Racial socialization messages and the quality of mother-child interactions in African American families. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2002;22(2):200–217. [Google Scholar]

- Freidlander ML, Larney LC, Skau M, Hotaling M, Cutting ML, Schwam M. Bicultural identification: Experiences of internationally adopted children and their parents. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2000;47(2):187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Freundlich M, Lieberthal JK. The gathering of the first generation of adult Korean adoptees: Adoptees’ perceptions of international adoption. 2000 Retrieved October 16, 2002, from http://www.adoptioninstitute.org/

- Gartner M, Kiang L, Supple A. Prospective links between ethnic socialization, ethnic and American identity, and well-being among Asian-American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43(10):1715–1727. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ponce N. Associations between racial discrimination, limited English proficiency, and health-related quality of life among 6 Asian ethnic groups in California. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(5):888. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, Chae D. Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: Evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2009;31(1):130–151. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(1):42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Britt A, Valrie CR, Kurtz-Costes B, Rowley SJ. Perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem in African American youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17(4):669–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Hasan S. The Asian Population: 2010. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Chen L. The nature of parents’ race-related communications to children: A developmental perspective. In: Balter L, Tamis-LeMonda CS, editors. Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues. New York: Psychology Press; 1999. pp. 467–490. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Johnson D. Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(4):981– 995. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents' ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(5):747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh VW, Fuligni AJ. Ethnic socialization and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(4):1202–1208. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Guilamo-Ramos V, Johansson M, Bouris A. Multiple regression analyses in clinical child and adolescent psychology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(3):456–479. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston KE, Swim JK, Saltsman BM, Deater-Deckard K, Petrill SA. Mothers' racial, ethnic, and cultural socialization of transracially adopted Asian children. Family Relations. An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2007;56(4):390–402. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Suh W, Heo J. Do Korean immigrant adolescents experience stress-related growth during stressful intergroup contact and acculturation? Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2014;54(1):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kim OM, Reichwald R, Lee R. Cultural socialization in families with adopted Korean American adolescents: A mixed-method, multi-informant study. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2013;28(1):69–95. doi: 10.1177/0743558411432636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare. Yearly Statistical Report. Korean Government Printing Office; Seoul, Korea: 2010. Retrieved May 30, 2011, from http://stat.mw.go.kr/front/include/download.jsp?bbsSeq=6&nttSeq=17070&atchSeq=2622. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. The transracial adoption paradox: History, research, and counseling implications of cultural socialization. The Counseling Psychologist. 2003;31(6):711–744. doi: 10.1177/0011000003258087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. Resilience against discrimination: Ethnic identity and other-group orientation as protective factors for Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52(1):36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. Parental perceived discrimination as a postadoption risk factor for internationally adopted children and adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16(4):493–500. doi: 10.1037/a0020651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Perry Y . the Minnesota International Adoption Project Team. Post-adoption risk and protective factors and the social and academic competence of internationally adopted children. In: McCubbin H, Ontai K, Kehl L, McCubbin L, Strom I, Hart H, et al., editors. Mulutiethnicity and multiethnic families: Development, identity, and resilience. Honolulu, HI: A Le’a; 2010. pp. 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JP, Lee RM, Hu AW, Kim OM. Ethnic identity as a moderator against discrimination for transracially and transnationally adopted Korean American adolescents. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0038360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LL, Lau AS. Teaching about race/ethnicity and racism matters: An examination of how perceived ethnic racial socialization processes are associated with depression symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2013;19(4):383–394. doi: 10.1037/a0033447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S. Ethnic socialization of African American children: Implications for parenting, identity development, and academic achievement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24(4):377–396. [Google Scholar]

- Meier DI. Cultural identity and place in adult Korean-American intercountry adoptees. Adoption Quarterly. 1999;3(1):15–48. [Google Scholar]

- McGill RK, Hughes D, Alicea S, Way N. Academic adjustment across middle school: The role of public regard and parenting. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48(4):1003–1018. doi: 10.1037/a0026006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Philip CL, Cogburn CD, Sellers RM. African American adolescents' discrimination experiences and academic achievement: Racial socialization as a cultural compensatory and protective factor. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006;32(2):199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Randolph TH, Holtzman M. The role of heritage camps in identity development among Korean transnational adoptees: A relational dialectics approach. Adoption Quarterly. 2010;13(2):75–99. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel E. Racism in peer-group interactions: South Asian students' experiences in Canadian academe. Journal of College Student Development. 2004;45(4):407–424. [Google Scholar]

- Seol KO, Lee RM. The effects of religious socialization and religious identity on psychosocial functioning in Korean American adolescents from immigrant families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26(3):371–380. doi: 10.1037/a0028199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JY, D’Antonio E, Son H, Kim S, Park Y. Bullying and discrimination experiences among Korean-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34(5):873–883. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrake EK, Rhee S. Ethnic identity as a predictor of problem behaviors among Korean American adolescents. Adolescence. 2004;39(155):601–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaki R. Strangers from a different shore: A history of Asian Americans. Boston: Little, Brown; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tran AGTT, Lee RM. Perceived ethnic–racial socialization, ethnic identity, and social competence among Asian American late adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16(2):169–178. doi: 10.1037/a0016400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuan M, Shiao JL. Choosing ethnicity, negotiating race: Korean adoptees in America. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. The Asian population: 2010 (Census 2010 Brief No. C2010BR/11) 2010 Retrieved March, 2012, from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf.

- Wang M, Huguley JP. Parental racial socialization as a moderator of the effects of racial discrimination on educational success among African American adolescents. Child Development. 2012;83(5):1716–1731. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu FH. Yellow: Race in America beyond Black and White. New York: Basic Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HC, Castro KS. Does nativity status matter in the relationship between perceived racism and academic performance of Asian American college students? Journal of College Student Development. 2011;52(2):234–245. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HC, Steger MF, Lee RM. Validation of the subtle and blatant racism scale for Asian American college students (SABR-A2) Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16(3):323. doi: 10.1037/a0018674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]