Abstract

Angiotensin-(1–7) improves glycemic control in animal models of cardiometabolic syndrome. The tissue-specific sites of action and blood pressure dependence of these metabolic effects, however, remain unclear. We hypothesized that angiotensin-(1–7) improves insulin sensitivity by enhancing peripheral glucose delivery. Adult male C57BL/6J mice were placed on standard chow or 60% high fat diet for 11 weeks. Angiotensin-(1–7) [400 ng/kg/min] or saline was infused subcutaneously during the last 3 weeks of diet, and hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps were performed at the end of treatment. High-fat fed mice exhibited modest hypertension (systolic blood pressure: 137±3 high-fat versus 123±5 mmHg chow; p=0.001), which was not altered by angiotensin-(1–7) [141±4 mmHg; p=0.574]. Angiotensin-(1–7) did not alter body weight or fasting glucose and insulin in chow or high-fat fed mice. Angiotensin-(1–7) increased the steady-state glucose infusion rate needed to maintain euglycemia in high-fat fed mice (31±5 angiotensin-(1–7) versus 16±1 mg/kg/min vehicle; p=0.017) reflecting increased whole-body insulin sensitivity, with no effect in chow-fed mice. The improved insulin sensitivity in high-fat fed mice was due to an enhanced rate of glucose disappearance (34±5 angiotensin-(1–7) versus 20±2 mg/kg/min vehicle; p=0.049). Angiotensin-(1–7) enhanced glucose uptake specifically into skeletal muscle by increasing translocation of glucose transporter 4 to the sarcolemma. Our data suggest that angiotensin-(1–7) has direct insulin-sensitizing effects on skeletal muscle, independent of changes in blood pressure. These findings provide new insight into mechanisms by which angiotensin-(1–7) improves insulin action, and provide further support for targeting this peptide in cardiometabolic disease.

Keywords: renin-angiotensin system, insulin resistance, obesity, metabolism, hypertension

Introduction

Over-activation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is a potential mechanism linking hypertension and the development of insulin resistance. Angiotensin (Ang) II promotes hypertension by inducing AT1 receptor-mediated vasoconstriction, renal fluid and salt retention, and sympathetic activation.1 Enhanced systemic RAS activity is also observed in obese and diabetic patients and closely correlates with insulin resistance.2 Ang II promotes insulin resistance by decreasing insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in peripheral tissues, inhibiting insulin-mediated suppression of hepatic glucose production, and impairing insulin signaling.2 Therapies that block Ang II activity [Ang converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and AT1 receptor antagonists] reduce incidence of new-onset type II diabetes in randomized clinical trials.3 These drugs also increase levels of Ang-(1–7), a peptide that counter-regulates Ang II actions, which may contribute to their beneficial cardiometabolic effects.4

Ang-(1–7) binds the G-protein coupled receptor mas to produce vasodilatory, anti-hypertensive, sympatholytic, and cardioprotective effects.4 Accumulating evidence suggests that activation of the Ang-(1–7)/mas axis also improves glucose homeostasis. Chronic peripheral or central Ang-(1–7) infusion lowers blood pressure (BP) and improves glucose tolerance in fructose-fed rats.5–7 Conversely, global mas receptor and ACE2 deletion, both of which reduce Ang-(1–7) activity, induce a metabolic syndrome-like phenotype in mice.8, 9 These studies support the potential for targeting Ang-(1–7) in cardiometabolic disease. The precise mechanisms and blood pressure dependence of Ang-(1–7) effects on insulin action, however, remain unclear.

We hypothesized that Ang-(1–7) would improve insulin sensitivity during progression of cardiometabolic syndrome, when levels of the peptide are deficient,10 by enhancing peripheral glucose delivery. To test this, we performed hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps in high fat diet (HFD) and chow-fed mice following chronic peripheral Ang-(1–7) administration. We demonstrate that Ang-(1–7) produces blood pressure-independent improvement in whole-body insulin sensitivity in HFD mice by enhancing insulin-stimulated muscle glucose uptake (MGU). In contrast to our hypothesis, this improvement was not due to changes in glucose delivery but instead was associated with increased glucose transporter 4 (Glut4) levels at the myocyte plasma membrane (sarcolemma).

Methods

These studies were approved by the Vanderbilt Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. For a detailed Methods section please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org.

Mouse Models

Male 6 week-old C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory) were fed standard chow (5001 Laboratory Rodent Diet) or 60% HFD (Bioserv F3282) ad libitum for 11 weeks. After 8 weeks of diet, subcutaneous osmotic mini-pumps (Alzet Model 2004) were implanted to deliver Ang-(1–7) [400 ng/kg/min; Bachem] or saline vehicle for 3 weeks.

Assessment of Body Composition, Hemodynamics, and Cardiac Function

Body composition was determined after 2 weeks of treatment using an mq10 nuclear magnetic resonance analyzer (Bruker Optics). Transthoracic echocardiography was also performed at this time point using a Sonos 5500 system (Agilent). BP and heart rate (HR) were measured via an indwelling carotid artery catheter connected to a transducer and a BPA-400 analyzer (Digi-Med).

Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamps (Insulin Clamps)

Insulin clamps were performed in conscious, unstressed, chronically catheterized mice as previously described.11 Mice were fasted for 5 hours prior to starting the insulin clamp. A [3-3H]glucose (0.04µCi·min−1; Perkin Elmer) infusion was starting at t=−90 min to determine rates of plasma glucose appearance (Ra) and disappearance (Rd). At t=0 min, continuous insulin (4mU·kg−1·min−1; Humulin R; Eli Lilly) and variable glucose (D50 + 50µCi[3-3H]glucose) infusions were initiated. From time t=0 to 120 min, arterial glucose was measured every 10 min, with the exogenous glucose infusion rate (GIR) adjusted to maintain euglycemia (130–150 mg/dl). Steady-state GIR and [3-3H]glucose kinetics were determined from t=80 to 120 min. Arterial blood samples were taken at baseline (basal) and during steady state (clamp) to measure insulin and non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) levels. At t=120 min, mice received an intravenous bolus of 2[14C]deoxyglucose (2[14C]DG; 13µCi; Perkin Elmer) to determine the tissue-specific glucose metabolic index (Rg).

Analysis of plasma and tissue samples from insulin clamp

Insulin was measured by double antibody radioimmunoassay12 and NEFA by enzymatic colorimetric assay (NEFA C Kit; Wako Chemicals). 3[3H]glucose, 2[14C]2DG, and 2[14C]2DG-6-phosphate radioactivity were measured using liquid scintillation counting. EndoRa and Rd were calculated using non-steady-state equations.13 Rg was calculated as previously described.14

Immunostaining

CD31, Glut4, and Cav3 immunostaining were assessed in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, 5µM gastrocnemius muscle sections using anti-CD31 (BD Biosciences), anti-Glut4 (Abcam), and anti-Cav3 (Santa Cruz) antibodies. CD31 staining was visualized with EnVision+HRP/DAB System (Dako). Glut4 and Cav3 staining were visualized with fluorescent secondary antibodies. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ (NIH).

Immunoblotting

Gastrocnemius homogenates were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, and probed with phosphorylated Akt (Ser473; Cell Signaling), total Akt (Cell Signaling), phosphorylated AS160 (Ser588; Cell Signaling), and total AS160 (Millipore) antibodies.

Microspheres

In a separate cohort of HFD mice [n=4 vehicle, n=3 Ang-(1–7)], 100 µl of yellow 15-µm microspheres (Dye-Trak, Triton Technology) were injected into the carotid artery after the last sampling time point of the insulin clamp to measure regional blood flow to the hind limb.

Circulating Ang Peptide Levels

Plasma Ang-(1–7) and Ang II levels were measured in a separate cohort of mice that did not undergo insulin clamps [n=6 chow-fed, vehicle; n=6 chow-fed Ang-(1–7); n=8 HFD, vehicle; n=8 HFD Ang-(1–7)] by radioimmunoassay.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Analyses were performed using Prism (Version 6.0, GraphPad), with a two-tailed p value <0.05 defined as statistical significance. Differences in outcomes were compared using unpaired t-test, or two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc tests.

Results

Effect of Ang-(1–7) on cardiovascular indices

Plasma Ang-(1–7) was reduced in HFD versus chow-fed mice (Table 1; p=0.045 diet effect). Chronic Ang-(1–7) infusion restored HFD-induced reductions in the peptide to approximately 70% of levels seen in chow-fed mice. There were significant diet (p=0.015) and interaction (p=0.004) effects for plasma Ang II, which were driven entirely by increased Ang II levels in chow-fed mice following Ang-(1–7) treatment. HFD mice had increased systolic (p=0.001), diastolic (p=0.039) and mean (p=0.001) BP, with no difference in HR (p=0.129). There was no effect of Ang-(1–7) on BP or HR in chow-fed or HFD mice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hormonal and Cardiovascular Effects of Chronic Ang-(1–7) Administration

| Parameter, unit | Chow Vehicle |

Chow Ang-(1–7) |

HFD Vehicle |

HFD Ang-(1–7) |

PDiet | PDrug | PInt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 10 | 6 | 7 | |||

| Ang-(1–7), ng/ml | 2.94±1.29 | 1.72±0.90 | 0.45±0.15 | 1.97±1.31 | 0.045 | 0.267 | 0.191 |

| Ang II, ng/ml | 0.16±0.06 | 0.51±0.14 | 0.18±0.02 | 0.09±0.03 | 0.015 | 0.074 | 0.004 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 123±5 | 128±3 | 143±4 | 143±3 | 0.001 | 0.574 | 0.566 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 97±5 | 98±4 | 109±3 | 104±3 | 0.039 | 0.658 | 0.515 |

| MBP, mm Hg | 110±5 | 113±3 | 126±3 | 123±2 | 0.001 | 0.949 | 0.454 |

| Heart Rate, bpm | 647±41 | 701±24 | 618±21 | 648±19 | 0.129 | 0.119 | 0.652 |

Data are mean±SEM and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA for diet effect (PDiet), drug effect (PDrug), and their interaction (PInt).

HFD, high fat diet; Ang, angiotensin; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MBP, mean blood pressure.

Effect of Ang-(1–7) on metabolic indices

Body weight and adiposity were higher in HFD mice (p=0.001 diet effect; Table 2). Ang-(1–7) did not alter body weight in HFD or chow-fed mice; however, there was a small reduction in adiposity (p=0.040 drug effect). HFD mice had higher basal arterial glucose and insulin (p=0.018 and p=0.001 diet effect, respectively), with no difference in NEFA. Ang-(1–7) tended to lower basal insulin (p=0.055 drug effect), but did not alter fasting glycemia or NEFA. During steady-state hyperinsulinemia, glucose was clamped at ~140 mg•dl−1 glucose in both HFD and chow-fed mice (Figure 1A and 1B). HFD mice maintained higher insulin levels during the clamp (p=0.002 diet effect; Table 2), compared with chow-fed mice. Ang-(1–7) did not alter clamp glucose and insulin levels, but significantly enhanced insulin-mediated suppression of NEFA (p=0.001 drug effect; Table 2).

Table 2.

Metabolic Effects of Chronic Ang-(1–7) Administration

| Parameter, unit | Chow Vehicle |

Chow Ang-(1–7) |

HFD Vehicle |

HFD Ang-(1–7) |

PDiet | PDrug | PInt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 10 | 6 | 7 | |||

| Body Mass, g | 29±1 | 28±1 | 39±2 | 37±1 | 0.001 | 0.321 | 0.981 |

| Adiposity, % | 6.7±0.7 | 6.5±0.2 | 35.6±2.6 | 30.1±1.4 | 0.001 | 0.040 | 0.056 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | |||||||

| Basal | 132±7 | 131±7 | 152±13 | 153±7 | 0.018 | 0.969 | 0.923 |

| Clamp | 141±3 | 142±4 | 133±3 | 137±3 | 0.078 | 0.555 | 0.603 |

| Insulin, pmol/l | |||||||

| Basal | 226±40 | 136±19 | 648±100 | 533±47 | 0.001 | 0.055 | 0.843 |

| Clamp | 585±59 | 569±58 | 1518±430 | 1245±290 | 0.002 | 0.549 | 0.480 |

| NEFA, mmol/l | |||||||

| Basal | 0.81±0.12 | 0.62±0.13 | 0.57±0.10 | 0.37±0.08 | 0.055 | 0.129 | 0.947 |

| Clamp | 0.25±0.06 | 0.05±0.03 | 0.25±0.05 | 0.11±0.06 | 0.677 | 0.001 | 0.472 |

Data are mean±SEM and were analyzed by two-way ANOVA for diet effect (PDiet), drug effect (PDrug), and their interaction (PInt). Metabolic hormones were measured in arterial blood at baseline (basal), and during steady state of hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps (clamp).

HFD, high fat diet; Ang, angiotensin; NEFA, non-esterified fatty acids.

Figure 1. Ang-(1–7) improves whole-body insulin sensitivity in high-fat diet (HFD) mice.

A, B: Arterial glucose levels were maintained at ~140 mg/dl during insulin clamps by variable venous infusion of 50% glucose. C, D: The glucose infusion rate (GIR) needed to maintain euglycemia, a measure of whole-body insulin sensitivity, over the 120 min period of the insulin clamp. E: There was no effect of Ang-(1–7) on mean steady-state GIR (measured from t=80–120 min of the insulin clamp) in chow fed mice. F: Ang-(1–7) significantly increased the mean steady-state GIR in HFD mice.

Ang-(1–7) reverses HFD-induced skeletal muscle (SkM) insulin resistance

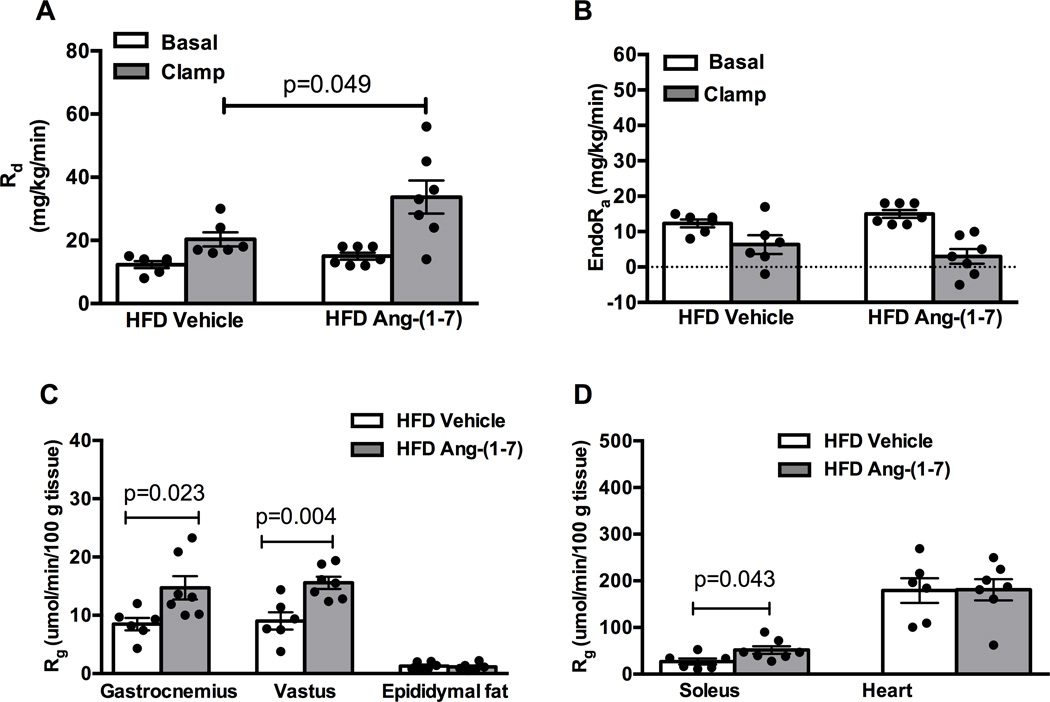

The GIR required to maintain euglycemia during steady state hyperinsulinemia, a measure of whole-body insulin sensitivity, was similar following Ang-(1–7) versus saline treatment in chow-fed mice (Figures 1C and 1E; p=0.143). As expected, HFD mice had lower whole-body insulin sensitivity compared with chow fed-mice (p=0.001). Ang-(1–7) doubled the GIR required to maintain euglycemia in HFD mice (Figures 1D and 1F; p=0.017). This enhanced whole body insulin sensitivity was due to increased insulin-stimulated peripheral glucose disposal (Rd; Figure 2A; p=0.049). There was no effect of Ang-(1–7) on insulin-mediated suppression of endogenous glucose production (EndoRa; Figure 2B; p=0.476). Consistent with effects on peripheral glucose disposal, Ang-(1–7) augmented insulin-stimulated glucose uptake (Rg) in soleus, gastrocnemius, and vastus muscles in HFD mice, with no effect in epididymal adipose or cardiac tissue (Figures 2C and 2D). Ang-(1–7) did not alter Rd, EndoRa or Rg in chow-fed mice (Figure S1, please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Figure 2. Ang-(1–7) improves insulin sensitivity in high-fat diet (HFD) mice by increasing insulin-stimulated skeletal muscle glucose uptake.

A: Ang-(1–7) increased peripheral glucose disposal (Rd) in HFD mice as determined by steady-state plasma levels of 3[3H]glucose. B: Ang-(1–7) had no effect on the insulin-stimulated rate of endogenous glucose production (EndoRa). C, D: Ang-(1–7) increased the glucose metabolic index (Rg) in gastrocnemius, vastus, and soleus skeletal muscles from HFD mice as determined by 2[14C]deoxyglucose accumulation, with no effect in epididymal fat or heart.

Ang-(1–7) does not improve measures of perfusion in HFD mice

To determine if the Ang-(1–7)-mediated improvement in insulin sensitivity was due to improved vascular glucose delivery, we measured indices of SkM perfusion in HFD mice. Levels of a capillary density marker (CD31) were not different in gastrocnemius muscle following Ang-(1–7) treatment (Figures S2A and S2B). Hind limb perfusion, measured by deposition of colored microspheres at the end of the insulin clamp, was not different between treatment groups (Figure S2C). Finally, Ang-(1–7) did not alter cardiac function (Table S1).

Ang-(1–7) enhances sarcolemmal Glut4 translocation in HFD mice

A critical step in insulin-stimulated MGU is translocation of Glut4 from intracellular vesicles to the sarcolemma. To determine if Ang-(1–7) improves SkM insulin sensitivity by increasing sarcolemmal Glut4 levels, we measured Glut4 abundance within the region demarcated by the sarcolemmal marker Cav3 in gastrocnemius muscle (Figure 3A). Ang-(1–7) increased mean Glut4 fluorescence at the muscle plasma membrane in HFD mice (Figure 3B; p=0.011). This increased Glut4 trafficking was associated with reduced total AS160 protein, a negative regulator of Glut4 translocation (Figure 3C; p=0.034), with no effect on phosphorylated AS160 (p=0.999). Ang-(1–7) did not alter phosphorylated or total Akt in HFD mice (Figure S4).

Figure 3. Ang-(1–7) increases sarcolemmal Glut4 in high-fat diet (HFD) mice by reducing levels of AS160, a negative regulator of Glut4 trafficking.

A: Representative 500× magnification micrographs of gastrocnemius sections from HFD mice treated with vehicle versus Ang-(1–7). Sections were stained for Cav3 (green) and Glut4 (white) and images were obtained by confocal microscopy. B: Ang-(1–7) increased sarcolemmal Glut4, measured as the mean Glut4 fluorescence intensity in the region demarcated by Cav3 staining. C: Immunoblot of gastrocnemius extracts from clamped HFD vehicle and Ang-(1–7)-treated mice. Ang-(1–7) decreased total AS160 protein levels, with no effect on phosphorylated AS160.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that chronic systemic Ang-(1–7) administration reverses HFD-induced whole-body insulin resistance by enhancing insulin-stimulated MGU. These insulin-sensitizing effects of Ang-(1–7) on SkM were associated with increased sarcolemmal Glut4 levels and down-regulation of AS160, a negative regulator of Glut4 translocation. Importantly, these effects occurred independent of changes in body weight, blood pressure, and measures of systemic and regional perfusion. Taken together, these findings provide evidence for blood pressure-independent effects of Ang-(1–7) on insulin action, and further support targeting this peptide to treat insulin resistance in cardiometabolic disease.

Numerous previous studies using intraperitoneal glucose and insulin tolerance tests have demonstrated that activation of the Ang-(1–7)/mas axis improves whole-body glucose homeostasis.5–7, 15 These tests involve a number of variables including intestinal glucose absorption, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, insulin sensitivity, glucose effectiveness, and counter-regulatory responses. Here, we specifically measured the contribution of insulin sensitivity to Ang-(1–7)-induced improvements in glucose tolerance using insulin clamps. Moreover, by combining the insulin clamp with isotopic glucose tracers, as in the present study, we are able to assess tissue-specific insulin action. Using this gold standard method, we provide evidence that restoration of physiological Ang-(1–7) levels improves whole-body insulin sensitivity in a well-established animal model of cardiometabolic syndrome that exhibits mild hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and modest hypertension.16 We did not observe an effect of chronic Ang-(1–7) in chow-fed mice, in contrast to reports showing acute intravenous Ang-(1–7) enhances insulin sensitivity in lean anesthetized rats.17, 18 This may reflect differences in species and methodology, as well as compensatory mechanisms to prolonged Ang-(1–7) elevation including mas receptor internalization.19

Interestingly, Ang-(1–7) did not alter the mild fasting hyperglycemia induced by HFD feeding in this study. The first response, however, to increased insulin action is compensation by the endocrine pancreas. This is evidenced by an initial reduction in insulin, without changes in blood glucose or hemoglobin A1c levels.20 In our study, Ang-(1–7) treated-mice had approximately 20% lower fasting insulin levels than vehicle-treated mice. Similarly, short-term Ang-(1–7) treatment (2 to 4 weeks) lowers plasma insulin levels in fructose fed rats, but does not lower fasting glycemia.5, 7 Longer-term Ang-(1–7) treatment (8–24 weeks) lowers both fasting insulinemia and glycemia in animal models of cardiometabolic syndrome.7, 15 Thus, an improvement in insulin sensitivity precedes and contributes to normalization of glycemia. In our study, it is likely glycemia would have been lowered with more prolonged Ang-(1–7) treatment.

The reason for maintained hyperglycemia following short-term Ang-(1–7) treatment is unclear. It is conceivable that an increase in basal glucose transport and/or delivery would increase MGU and normalize fasting glycemia. In this study, sarcolemmal Glut4 levels and SkM perfusion were both measured under the insulin-stimulated conditions. It is not likely that the lack of effect of Ang-(1–7) on SkM perfusion in our study would contribute to the preserved basal hyperglycemia, given that an increase in glucose delivery in the absence of hyperinsulinemia has no impact on glucose uptake.21 Importantly, an improvement in insulin sensitivity alone has beneficial effects on cardiometabolic health. For example, insulin sensitivity is a stronger predictor of type 2 diabetes development compared with fasting glucose or HbA1c.22, 23 Furthermore, insulin sensitivity is a stronger risk factor for cardiovascular disease than hyperglycemia.24

Over-activation of the RAS, and in particular Ang II, is associated with development of SkM and hepatic insulin resistance.25, 26 We found that chronic Ang-(1–7) infusion improves insulin-stimulated MGU in HFD mice. This corroborates in vitro studies showing that Ang-(1–7) potentiates insulin-stimulated MGU in normal rodents and reverses Ang II-induced muscle insulin resistance.9, 27 Ang-(1–7) did not alter basal or insulin-stimulated hepatic glucose output in HFD mice, which was normal in HFD compared with chow-fed mice. The lack of hepatic insulin resistance in HFD mice is consistent with previous reports from our group.28, 29 This is likely due to the high physiologic insulin dose infused during clamps, which could mask more subtle effects of Ang-(1–7) on hepatic insulin sensitivity. Ang-(1–7) reduced adiposity and improved insulin-stimulated suppression of lipolysis in our study, consistent with reports showing improved adipose insulin action.5, 15 Although there was no effect of Ang-(1–7) on adipose glucose uptake during insulin clamps, one cannot rule out an indirect contribution of reduced adiposity to improved insulin sensitivity.

It is unclear to what extent the vascular effects of Ang-(1–7) contribute to its metabolic effects. Ang-(1–7) promotes endothelial-dependent vasodilation in macro- and micro-vessels.4 The improved glucose tolerance in fructose-fed rats with Ang-(1–7) was associated with BP-lowering,5, 6 which could indicate vasodilation and manifest as improved glucose delivery and insulin sensitivity. Ang-(1–7) did not alter BP or cardiac function, however, in HFD mice. The lack of a depressor effect in our model is consistent with accumulating evidence showing that the anti-hypertensive effect of Ang-(1–7) is not apparent in all research models. There are several potential reasons for varying BP effects with Ang-(1–7) including species differences, diet, and dose, duration, and route of treatment. The discrepancy between the two previous studies and our results most likely reflects differences in animal models. Fructose-fed rats do not gain weight during the first 8 weeks feeding and, for the most part, develop isolated systolic hypertension.30 In contrast, high fat diet-fed mice have about 5 times more adiposity than their lean counterparts, and develop both systolic and diastolic hypertension. The hypertension in these two models may therefore be driven by different mechanisms with varying sensitivity to Ang-(1–7).

Ang-(1–7) could also influence regional perfusion to improve insulin sensitivity. Indeed, acute Ang-(1–7) increases muscle microvascular perfusion in normal rats.18 We were unable to detect differences in insulin-stimulated muscle perfusion following Ang-(1–7) in HFD mice. There are several possible explanations: (1) previous studies used acute intravenous Ang-(1–7) and were done under anesthesia,18 which alone has hemodynamic effects; (2) the ability of acute Ang-(1–7) to promote peripheral vasodilation could be lost following prolonged exposure; (3) while microsphere deposition is the gold standard for assessing microvascular perfusion in conscious animals, it may not give the resolution necessary to detect small changes; (4) the mild hyperglycemia in HFD mice may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, thus preventing Ang-(1–7) vasodilatory actions; and (5) Ang-(1–7) may improve other aspects of endothelial function that enhance SkM insulin action such as transendothelial insulin transport from capillaries to the myocyte surface.

Given that we did not observe changes in perfusion, we examined direct effects of Ang-(1–7) on SkM. A critical component of SkM insulin action is partitioning of Glut4 to the sarcolemma to enhance glucose transport.31 Chronic Ang-(1–7) potentiated insulin-stimulated Glut4 translocation in HFD mice, thereby increasing glucose transport into myocytes. This is consistent with previous reports demonstrating effects of Ang-(1–7) on Glut4. Namely, ACE2 deletion in mice reduces SkM Glut4 expression, an effect reversed by Ang-(1–7) infusion.9 Furthermore, ACE inhibition, which increases Ang-(1–7) levels, improves insulin sensitivity by enhancing Glut4 translocation.32 Insulin stimulates Glut4 translocation via activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway. Ultimately, Akt phosphorylates and inactivates AS160 (a Rab GTPase-activating protein) to allow Glut4-containing vesicles to fuse with the sarcolemma.33 In normal and fructose-fed rats, Ang-(1–7) stimulates Akt phosphorylation in insulin-sensitive tissues.5, 34, 35 In addition, Ang-(1–7) increases AS160 phosphorylation in normal and diabetic rats.34, 36 In our study, Ang-(1–7) reduced AS160 protein levels, which functionally promotes increased Glut4 at the myocyte plasma membrane,37 independent of changes in classical Akt signaling. The precise mechanism suppressing AS160 levels is unclear, but may involve transcriptional regulation.

There are some potential limitations to these studies. We did not examine receptor and related intracellular signaling mechanisms involved in Ang-(1–7) metabolic effects. The literature suggests that most, if not all, of Ang-(1–7) actions in vivo are mediated by mas receptors.38 Indeed, the ability of Ang-(1–7) to augment insulin-mediated glucose disposal is mas-dependent in anesthetized rats.18 There is evidence, however, that AT2 receptors participate in complex vascular effects of Ang-(1–7). Furthermore, due to limitations in blood volume sampling in mice, we were unable to measure all components of the circulating RAS. The few studies examining Ang-(1–7) effects on RAS components showed no effect on renin activity in lean rats,39 and reduced aldosterone in fructose-fed rats7. We observed significant plasma Ang II elevations following Ang-(1–7) infusion in chow-fed mice, with no effect in HFD mice. A similar elevation was observed in lean rats and thought to reflect a homeostatic feedback response.39 Finally, it should be noted that the HFD had lower sodium content compared with the control diet. Despite lower sodium, HFD mice exhibited a cardiometabolic syndrome-like phenotype and did not have increased RAS components. Furthermore, all HFD mice were fed the same diet, indicating the improved insulin sensitivity with Ang-(1–7) was sodium-independent.

In summary, these studies show that chronic Ang-(1–7) reverses diet-induced muscle insulin resistance by enhancing insulin-stimulated Glut4 translocation. Importantly, these effects occurred even when giving a dose of Ang-(1–7) that does not lower BP. These findings provide evidence for divergence between Ang-(1–7) effects on BP and glucose metabolism, and support the growing notion that the RAS influences whole body physiology beyond control of BP.40

Perspectives

The worldwide prevalence of insulin resistance secondary to obesity is alarmingly high. Thus, there is an urgent need to understand molecular mechanisms contributing to obesity-associated insulin resistance and related cardiovascular comorbidities. Therapies that block Ang II actions have emerged as an important strategy to lower BP in obese patients due to their positive metabolic profile.3 The positive metabolic effects of these therapies, however, may also reflect elevated Ang-(1–7) levels.4 Animal models of cardiometabolic syndrome have reduced circulating levels of Ang-(1–7),10 and modulation of the Ang-(1–7)/ACE2/mas receptor axis improves glucose metabolism. We extend these findings by showing that Ang-(1–7) has direct insulin sensitizing effects on SkM in obese mice, which are BP-independent. These findings enhance our understanding of RAS mechanisms involved in regulation of insulin action, and provide new insight into the potential for targeting Ang-(1–7) in cardiometabolic disease.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

1) What is New?

Chronic Ang-(1–7) administration reverses diet-induced muscle insulin resistance by enhancing insulin-stimulated Glut4 translocation. Importantly, these insulin-sensitizing effects are independent of changes in body weight and blood pressure.

2) What is Relevant?

These findings provide new insight into tissue-specific mechanisms by which angiotensin-(1–7) improves insulin action in an animal model of cardiometabolic syndrome, and enhance our understanding of renin-angiotensin mechanisms involved in glucose homeostasis.

3) Summary

This study provides new evidence for blood pressure-independent effects of Ang-(1–7) to improve skeletal muscle insulin action in obese mice. These findings provide further support for targeting Ang-(1–7) in treatment of cardiometabolic disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors received technical support from the Vanderbilt Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center and the laboratory of Dr. David Robertson in the Vanderbilt Division of Clinical Pharmacology.

Sources of Funding

These studies were funded by NIH grant K99 HL122507. Additional support was provided by NIH grants P01 HL056693, U24 DK059637, R01 DK054902, and T32 DK007563.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Kim S, Iwao H. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of angiotensin ii-mediated cardiovascular and renal diseases. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:11–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luther JM, Brown NJ. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and glucose homeostasis. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:734–739. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abuissa H, Jones PG, Marso SP, O'Keefe JH., Jr Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers for prevention of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:821–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schindler C, Bramlage P, Kirch W, Ferrario CM. Role of the vasodilator peptide angiotensin-(1–7) in cardiovascular drug therapy. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3:125–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giani JF, Mayer MA, Munoz MC, Silberman EA, Hocht C, Taira CA, Gironacci MM, Turyn D, Dominici FP. Chronic infusion of angiotensin-(1–7) improves insulin resistance and hypertension induced by a high-fructose diet in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E262–E271. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90678.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guimaraes PS, Oliveira MF, Braga JF, Nadu AP, Schreihofer A, Santos RA, Campagnole-Santos MJ. Increasing angiotensin-(1–7) levels in the brain attenuates metabolic syndrome-related risks in fructose-fed rats. Hypertension. 2014;63:1078–1085. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus Y, Shefer G, Sasson K, Kohen F, Limor R, Pappo O, Nevo N, Biton I, Bach M, Berkutzki T, Fridkin M, Benayahu D, Shechter Y, Stern N. Angiotensin 1–7 as means to prevent the metabolic syndrome: Lessons from the fructose-fed rat model. Diabetes. 2013;62:1121–1130. doi: 10.2337/db12-0792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santos SH, Fernandes LR, Mario EG, Ferreira AV, Porto LC, Alvarez-Leite JI, Botion LM, Bader M, Alenina N, Santos RA. Mas deficiency in fvb/n mice produces marked changes in lipid and glycemic metabolism. Diabetes. 2008;57:340–347. doi: 10.2337/db07-0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeda M, Yamamoto K, Takemura Y, Takeshita H, Hongyo K, Kawai T, Hanasaki-Yamamoto H, Oguro R, Takami Y, Tatara Y, Takeya Y, Sugimoto K, Kamide K, Ohishi M, Rakugi H. Loss of ace2 exaggerates high-calorie diet-induced insulin resistance by reduction of glut4 in mice. Diabetes. 2013;62:223–233. doi: 10.2337/db12-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupte M, Thatcher SE, Boustany-Kari CM, Shoemaker R, Yiannikouris F, Zhang X, Karounos M, Cassis LA. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 contributes to sex differences in the development of obesity hypertension in c57bl/6 mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1392–1399. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayala JE, Bracy DP, Malabanan C, James FD, Ansari T, Fueger PT, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH. Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps in conscious, unrestrained mice. J Vis Exp. 2011;57:3188. doi: 10.3791/3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan CR, Lazarow A. Immunoassay of pancreatic and plasma insulin following alloxan injection of rats. Diabetes. 1965;14:669–671. doi: 10.2337/diab.14.10.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steele R, Wall JS, De Bodo RC, Altszuler N. Measurement of size and turnover rate of body glucose pool by the isotope dilution method. Am J Physiol. 1956;187:15–24. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1956.187.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraegen EW, James DE, Jenkins AB, Chisholm DJ. Dose-response curves for in vivo insulin sensitivity in individual tissues in rats. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:E353–E362. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1985.248.3.E353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrade JM, Lemos Fde O, da Fonseca Pires S, Millan RD, de Sousa FB, Guimaraes AL, Qureshi M, Feltenberger JD, de Paula AM, Neto JT, Lopes MT, Andrade HM, Santos RA, Santos SH. Proteomic white adipose tissue analysis of obese mice fed with a high-fat diet and treated with oral angiotensin-(1–7) Peptides. 2014;60:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winzell MS, Ahren B. The high-fat diet-fed mouse: A model for studying mechanisms and treatment of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 3):S215–S219. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Echeverria-Rodriguez O, Del Valle-Mondragon L, Hong E. Angiotensin 1–7 improves insulin sensitivity by increasing skeletal muscle glucose uptake in vivo. Peptides. 2014;51:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu Z, Zhao L, Aylor KW, Carey RM, Barrett EJ, Liu Z. Angiotensin-(1–7) recruits muscle microvasculature and enhances insulin's metabolic action via mas receptor. Hypertension. 2014;63:1219–1227. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.03025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gironacci MM, Adamo HP, Corradi G, Santos RA, Ortiz P, Carretero OA. Angiotensin (1–7) induces mas receptor internalization. Hypertension. 2011;58:176–181. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.173344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cavaghan MK, Ehrmann DA, Byrne MM, Polonsky KS. Treatment with the oral antidiabetic agent troglitazone improves beta cell responses to glucose in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:530–537. doi: 10.1172/JCI119562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zinker BA, Lacy DB, Bracy DP, Wasserman DH. Role of glucose and insulin loads to the exercising limb in increasing glucose uptake and metabolism. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1993;74:2915–2921. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.6.2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdul-Ghani MA, Williams K, DeFronzo R, Stern M. Risk of progression to type 2 diabetes based on relationship between postload plasma glucose and fasting plasma glucose. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1613–1618. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorenzo C, Wagenknecht LE, Hanley AJ, Rewers MJ, Karter AJ, Haffner SM. A1c between 5.7 and 6.4% as a marker for identifying pre-diabetes, insulin sensitivity and secretion, and cardiovascular risk factors: The insulin resistance atherosclerosis study (iras) Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2104–2109. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laakso M, Kuusisto J. Insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia in cardiovascular disease development. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:293–302. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henriksen EJ, Prasannarong M. The role of the renin-angiotensin system in the development of insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;378:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coimbra CC, Garofalo MA, Foscolo DR, Xavier AR, Migliorini RH. Gluconeogenesis activation after intravenous angiotensin ii in freely moving rats. Peptides. 1999;20:823–827. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(99)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasannarong M, Santos FR, Henriksen EJ. Ang-(1–7) reduces ang ii-induced insulin resistance by enhancing akt phosphorylation via a mas receptor-dependent mechanism in rat skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;426:369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.08.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonner JS, Lantier L, Hocking KM, Kang L, Owolabi M, James FD, Bracy DP, Brophy CM, Wasserman DH. Relaxin treatment reverses insulin resistance in mice fed a high-fat diet. Diabetes. 2013;62:3251–3260. doi: 10.2337/db13-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang L, Mayes WH, James FD, Bracy DP, Wasserman DH. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 opposes diet-induced muscle insulin resistance in mice. Diabetologia. 2014;57:603–613. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3128-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran LT, Yuen VG, McNeill JH. The fructose-fed rat: A review on the mechanisms of fructose-induced insulin resistance and hypertension. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;332:145–159. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leto D, Saltiel AR. Regulation of glucose transport by insulin: Traffic control of glut4. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:383–396. doi: 10.1038/nrm3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiuchi T, Cui TX, Wu L, Nakagami H, Takeda-Matsubara Y, Iwai M, Horiuchi M. Ace inhibitor improves insulin resistance in diabetic mouse via bradykinin and no. Hypertension. 2002;40:329–334. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000028979.98877.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sano H, Kane S, Sano E, Miinea CP, Asara JM, Lane WS, Garner CW, Lienhard GE. Insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of a rab gtpase-activating protein regulates glut4 translocation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14599–14602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munoz MC, Giani JF, Burghi V, Mayer MA, Carranza A, Taira CA, Dominici FP. The mas receptor mediates modulation of insulin signaling by angiotensin-(1–7) Regul Pept. 2012;177:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munoz MC, Giani JF, Dominici FP. Angiotensin-(1–7) stimulates the phosphorylation of akt in rat extracardiac tissues in vivo via receptor mas. Regul Pept. 2010;161:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santos SH, Giani JF, Burghi V, Miquet JG, Qadri F, Braga JF, Todiras M, Kotnik K, Alenina N, Dominici FP, Santos RA, Bader M. Oral administration of angiotensin-(1–7) ameliorates type 2 diabetes in rats. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014;92:255–265. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larance M, Ramm G, Stockli J, van Dam EM, Winata S, Wasinger V, Simpson F, Graham M, Junutula JR, Guilhaus M, James DE. Characterization of the role of the rab gtpase-activating protein as160 in insulin-regulated glut4 trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37803–37813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503897200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santos RA. Angiotensin-(1–7) Hypertension. 2014;63:1138–1147. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mendes AC, Ferreira AJ, Pinheiro SV, Santos RA. Chronic infusion of angiotensin-(1–7) reduces heart angiotensin ii levels in rats. Regul Pept. 2005;125:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Passos-Silva DG, Verano-Braga T, Santos RA. Angiotensin-(1–7): Beyond the cardio-renal actions. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013;124:443–456. doi: 10.1042/CS20120461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.