Abstract

It has been previously shown that intestinal proteases translocate into the circulation during hemorrhagic shock and contribute to proteolysis in distal organs. However, consequences of this phenomenon have not previously been investigated using high-throughput approaches. Here, a shotgun label-free quantitative proteomic approach was utilized to compare the peptidome of plasma samples from healthy and hemorrhagic shock rats to verify the possible role of uncontrolled proteolytic activity in shock. Plasma was collected from rats after hemorrhagic shock (HS) consisting of two-hour hypovolemia followed by two-hour reperfusion, and from healthy control (CTRL) rats. A new two-step enrichment method was applied to selectively extract peptides and low molecular weight proteins from plasma, and directly analyze these samples by tandem mass spectrometry. 126 circulating peptides were identified in CTRL and 295 in HS animals. 96 peptides were present in both conditions; of these, 57 increased and 30 decreased in shock. In total, 256 peptides were increased or present only in HS confirming a general increase in proteolytic activity in shock. Analysis of the proteases that potentially generated the identified peptides suggests that the larger relative contribution of to the proteolytic activity in shock is due to chymotryptic-like proteases. These results provide quantitative confirmation that extensive, system-wide proteolysis is part of the complex pathologic phenomena occurring in hemorrhagic shock.

Keywords: Hemorrhagic shock, Proteolysis, Serine-Proteases, Matrix Metalloproteases, Peptidomics, Mass spectrometry

INTRODUCTION

Circulatory shock is the leading cause of mortality in the intensive care unit [1], and despite decades of basic and clinical research, morbidity and mortality rates remain high. An incomplete understanding of the pathological mechanisms involved in tissue damage, organ dysfunction and failure limits available treatments for shock to source control (e.g. antibiotic therapy) and supportive therapy such as fluids and pressor agents.

The pathways activated in response to an initial insult, for example global ischemia in hemorrhagic shock (HS), suggest that shock involves several common pathologic mechanisms. One specific organ, long suspected as fundamental to the pathogenesis of shock is the intestine, whose failure triggers a widespread inflammatory state, which can ultimately lead to multiple organ failure (MOF) and death. One of the hypotheses that implicate the intestine in the progression of shock is centered around the role of the enteral digestive enzymes [2]. The intestinal mucosal barrier may become severely damaged due to hypoperfusion in hemorrhage and sepsis. As a consequence, its function as a barrier between the intestinal lumen and the interstitial tissue and vasculature may become compromised, and digestive enzymes, such as proteases and lipases may exit the intestinal lumen and reach the systemic circulation, resulting in global cellular and organ dysfunction [2–5]. Digestive proteases contribute to malfunction of important transmembrane receptors, such as the insulin receptor, possibly through cleavage [4], but they are also known to activate matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in vivo, and could therefore act as mediators of secondary cell and tissue injury. Both serine proteases and MMPs have the potential to cause uncontrolled pathological proteolysis, and this phenomenon may play an important role in the evolution of shock-induced organ failure.

We test here the hypothesis that hemorrhagic shock causes an increase in systemic proteolysis of proteins in the presence of increased enzymatic activity levels. We used high-throughput quantitative mass spectroscopy-based proteomic techniques to analyze the peptidome, in order to precisely identify and quantify the peptides in plasma.

Proteomic approaches have been introduced recently in shock research [6], but interpretation of the data is still limited by the lack of a comprehensive model of the disease. Here we report the results of the analysis of the peptidome of rat plasma collected after hemorrhagic shock (HS) in order to quantify the relative changes in the concentration of circulating peptides relative to their physiologic concentration in the plasma of healthy control rats. A systematic analysis of the circulating peptides, both in terms of their origin and possible generation by proteolytic cleavage, was carried out to obtain information on the proteolytic activity of several serine proteases and MMPs present in the bloodstream. The objective of the study was to garner direct evidence in support of one of the possible mechanistic processes underlying shock-induced organ failure and death, i.e. diffuse proteolysis. These results may open future directions to identify possible biomarkers in circulatory shock, by analysis of peptides and proteins that appear in the plasma starting from the experimental protocol set up in the present report.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. Experimental Protocol

The animal protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of California, San Diego and conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th edition, by the National Institutes of Health (2011).

Six male Wistar rats (300–450 g, Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) were randomly assigned to either a control (CTRL, n=3) or a hemorrhagic shock (HS, n=3) group. The animals were housed in the vivarium of the Department of Bioengineering at the University of California San Diego and experiments took place during the morning. The temperature (~ 20–22 °C) and humidity (~ 70–75%) in the vivarium are controlled and monitored regularly, and the light/dark cycles (6 hours light/6 hours dark) are standardized according to the facility procedures. Each cage houses at most two rats. Food and water are given at libitum and the health of animals is confirmed by regular veterinary inspection. The well-being of the animals is ensured according to Federal, State and University regulation.

After general anesthesia (ketamine 75 mg/kg + xylazine, 4 mg/kg; i.m.) the right femoral vein was cannulated for blood withdrawal and intravenous supplemental anesthesia (xylazine, 4 mg/kg; ketamine 7.5 mg/kg i.v.) and the right femoral artery for continuous monitoring of arterial blood pressure. Body temperature was measured continuously rectally, and the animals were placed on a heated stage (at 37°C) and covered with a heat-retaining blanket in order to limit the temperature drop occurring during the hypovolemic phase of the experiment. Both HS and CTRL animals were heparinized (porcine heparin from Sagent Pharmaceuticals, Schamburg, IL) following an initial stabilization after the induction of anesthesia (1 unit heparin/cc total blood volume, estimated at 6% of the body weight). Hemorrhage was induced by blood withdrawal from the femoral vein (0.5 cc/min) to a target mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 35 mmHg. Hypovolemia was maintained for two hours, at which point the shed blood was reinfused (0.5 cc/min). The shed blood was maintained at room temperature (~ 22°C) and gently warmed to 37°C before reinfusion to minimize the temperature gradient.

The animals were monitored for an additional two hours, and euthanized at the end of the observation period, with Beuthanasia-D (120 mg/kg, Merck Animal Health). CTRL animals were monitored under anesthesia and without any further intervention for the same duration of the shock experiment until euthanasia. Death was confirmed by verification of cardiac arrest after thoracotomy to expose the chest cavity.

B. Plasma collection

Just before euthanasia 1 mL of venous blood was collected in a BD Vacutainer ® Plus Plastic K2EDTA (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, U.S.A.) vial after the addition of a protease inhibitor solution (a tablet of cOmplete™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Roche, diluted in water to obtain a 10X solution with the plasma sample), and centrifugation at 1300 rpm for 10 min to separate plasma. The supernatant was collected, stored at +4°C and shipped for analysis by mass spectroscopy.

C. Shotgun analysis and label free quantitation

C.1 Sample preparation

500 μL of each plasma sample were diluted with an equal volume of 32% (v/v) acetic acid, transferred to an Amicon Ultra-0.5 mL centrifugal filter (MWCO 10K), and centrifuged at 5000×g at 4 °C for 2 hour to deplete the high molecular weight proteins [7]. After the first centrifugation, 500 μL of 32% (v/v) acetic acid were added to the Amicon Ultra filter device and centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 2 hours. The filtrate was precipitated with two volumes of cold acetonitrile (ACN) containing 0.1% of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (stored at 4 °C for at least 1 hours) and centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 30 minutes [8] to remove residual proteins. The supernatant containing peptides and low molecular weight proteins was collected, dried (Speed Vacuum), dissolved in 1% (v/v) formic acid and desalted (Zip-Tip C18, Millipore) before mass spectrometric (MS) analysis.

C.2 Liquid chromatography electrospray–tandem MS/MS analysis

LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis was performed on a Dionex UltiMate 3000 HPLC System with a PicoFrit ProteoPrep C18 column (200 mm, internal diameter of 75 μm) (New Objective, USA). Gradient: 1% ACN in 0.1 % formic acid for 10 min, 1–4 % ACN in 0.1% formic acid for 6 min, 4–30% ACN in 0.1% formic acid for 147 min and 30–50 % ACN in 0.1% formic for 3 min at a flow rate of 0.3 μl/min. The eluate was electrosprayed into an LTQ Orbitrap Velos (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) through a Proxeon nanoelectrospray ion source (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The LTQ-Orbitrap was operated in positive mode in data-dependent acquisition mode to automatically alternate between a full scan (m/z 350–2000) in the Orbitrap (at resolution 60000, AGC target 1000000) and subsequent collision-induced dissociation (CID) MS/MS in the linear ion trap of the 20 most intense peaks from full scan (normalized collision energy of 35%, 10 ms activation). Isolation window: 3 Da, unassigned charge states: rejected, charge state 1: rejected, charge states 2+, 3+, 4+: not rejected; dynamic exclusion enabled (60 s, exclusion list size: 200). Three technical replicate analyses of each sample were performed. Data acquisition was controlled by Xcalibur 2.0 and Tune 2.4 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

C.3 Data processing and statistical analysis

Mass spectra were analyzed using MaxQuant software (version 1.3.0.5). The initial maximum allowed mass deviation was set to 15 ppm for monoisotopic precursor ions and 0.5 Da for MS/MS peaks. Enzyme specificity was set as unspecific. N-terminal acetylation, methionine oxidation, and asparagine/glutamine deamidation were set as variable modifications. The spectra were searched by the Andromeda search engine against the rat Uniprot sequence database (release 03.12.2014). Quantification in MaxQuant was performed using the built in XIC-based label free quantification (LFQ) algorithm [9] using fast LFQ. The required false positive rate was set to 5% at the peptide and 5% at the protein level, and the minimum required peptide length was set to 6 amino acids. Statistical analyses were performed using the Perseus software (version 1.4.0.6, www.biochem.mpg.de/mann/tools/).

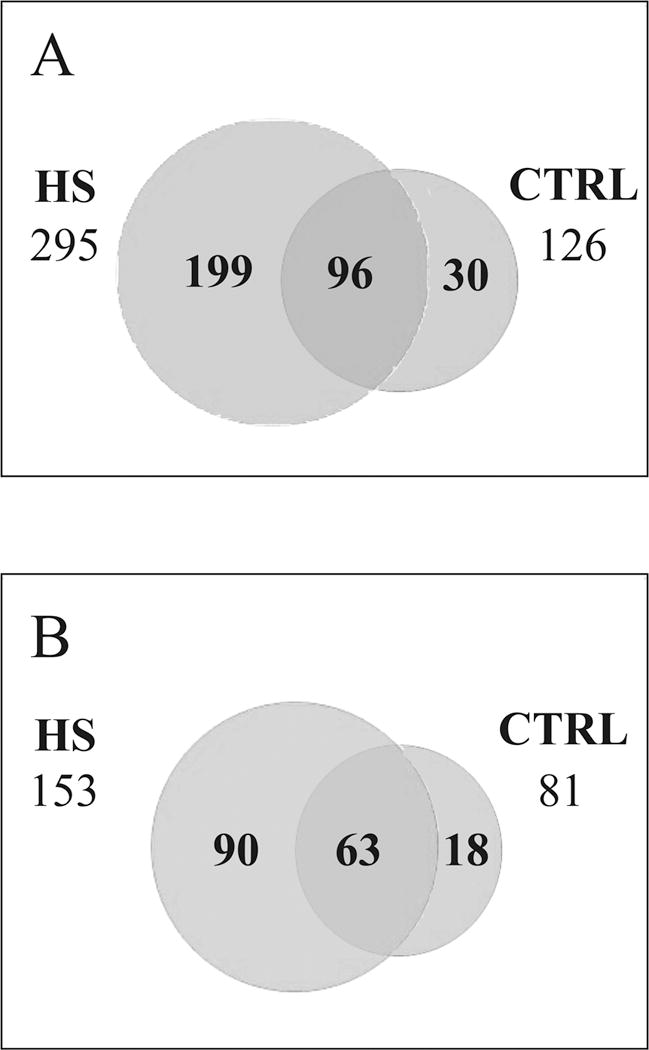

Three biological replicates (3 healthy vs. 3 hemorrhagic shock animals) were analyzed. Three technical replicates were carried out for each biological sample. Only peptides present in at least 2 out of 3 technical replicates were considered as positively identified and quantified in each biological replicate. Then, biological replicates were compared, leading to three groups of peptides: only-HS peptides (199 peptides), i.e. peptides that were found in HS samples in at least 2 out of 3 biological replicates; only-CTRL peptides (30), i.e. peptides that were found in CTRL samples in at least 2 out of 3 biological replicates; and peptides present in both HS and CTRL (96), i.e. identified and quantified in at least 2 out of 3 biological replicates both in HS and CTRL samples).

Peptides were considered increased or decreased if they were present only in either the healthy (CTRL) or hemorrhagic (HS) group or, in the case of the 96 peptides found in both groups, if they showed 50 % fold change differences (> 1.5-fold increase or < 0.67-fold decrease) in HS compared to CTRL, as calculated from the ratio of mean XIC-based label free quantification of the respective biological replicates [10].

Proteins were classified as secreted or non-secreted, and the presence of transmembrane topology was searched by combining the results of five different computer programs: Perseus Annotation, SecretomeP [11], SignalP [12], Phobius [13], TMHMM [14].

C.4 Plasma protease activity

The role played in the proteolysis observed following shock by some of the most important digestive enzymes (i.e., trypsin, chymotrypsin, elastase), and by several MMPs known for their proteolytic function in pathologic conditions [15, 16] (i.e. MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-14) was determined by matching the C-terminus of the sequences of the peptides identified in the MS-based analysis with the cleavage site specificities of the proteases.

The relative contribution of a specific protease to the overall proteolytic activity was estimated: i) in the case of HS, as the ratio between the number of peptides generated by the protease and found to be present only in HS or in a higher concentration vs. CTRL, and the total number of peptides present in the HS sample; ii) in the case of CTRL, as the ratio between the number of peptides generated by the protease and found to be present only in CTRL or in a higher concentration vs. HS, and the total number of peptides present in the CTRL sample. The data were also analyzed by a Fisher’s exact test to detect statistically significant enrichment (increase and/or decrease) in the fraction of peptides potentially generated by a specific protease in HS or CTRL as compared to all peptides detected and quantified.

To cross-validate the estimates of protease activity derived from the peptidomics based approach described above, serine protease activity in the plasma was determined by gelatin zymography, as performed by SDS-PAGE gels containing 80 μg/mL gelatin. Gels were renatured by four 15 min washes with 2.5% Triton X-100 and incubated overnight at 37°C in developing buffer (0.05 M Tris base, 0.2 M NaCl, 4 μM ZnCl2, 5 mM CaCl2·2H2O). Gels were subsequently stained (50% methanol, 10% acetic acid, 40% water, and 0.25% Coomassie blue solution) for one hour before de-staining in buffer (10% methanol, 10% acetic acid, 80% water). A standard protein ladder (Invitrogen) was used to estimate the molecular weights of the proteases. Gels were digitized and bands were analyzed in ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

RESULTS

A. Peptidomics of plasma in shock

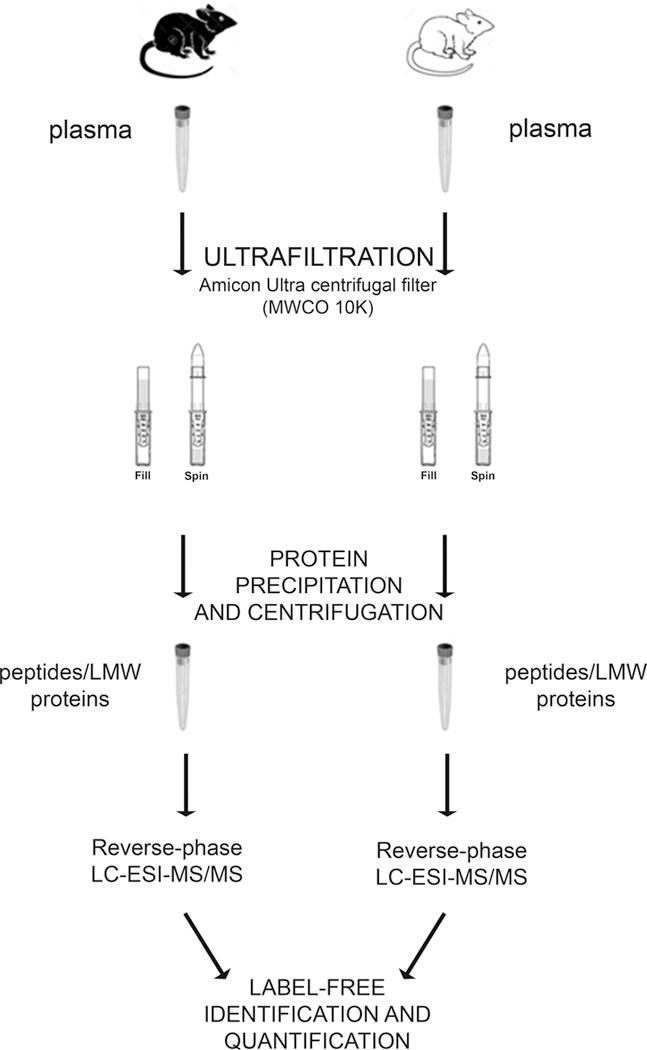

Shotgun label-free quantitative proteomic analysis is widely used to examine differences in global protein/peptide expression. This approach was utilized to compare the peptidome of plasma samples from healthy and hemorrhagic shock rats with the aim to identify and quantify the peptides present in plasma. These data serve to elucidate the possible role of uncontrolled proteolytic activity in shock. Figure 1 provides an overview of the workflow.

Figure 1. Peptidome sample preparation workflow for mass spectrometric analysis.

A new two-step enrichment method to selectively extract peptides and LMW components in plasma samples from healthy and hemorrhagic-shock rats was applied. The process consists of an ultrafiltration step with a 10kDa cut-off filter followed by a precipitation step conducted with a dissociating solution before LC-ESI MS/MS analysis

Due to the high complexity and wide dynamic range of plasma proteins, we applied a new two-step enrichment method to selectively extract peptides and low molecular weight (LMW) components, which are low abundant in plasma. The process consists of an ultrafiltration step with a 10kDa cut-off filter followed by a precipitation step conducted with a dissociating solution to increase the recovery of LMW molecules. To optimize reproducibility and quantification, each sample was then analyzed directly by LC-ESI MS/MS without any further separation step of the peptides mixture using the so-called shotgun approach. Analyses were performed on three biological replicates (3 CTRL vs 3 HS rats), each one analyzed three times (three technical replicates).

126 and 295 peptides were identified in the CTRL and HS groups, respectively (Figure 2A); among the 96 peptides present in both CTRL and HS, 57 increased (>1.5 fold-change) and 30 decreased (<0.67 fold change) in concentration in HS. Overall, the analysis identified 256 peptides, which were increased or present only in HS while 60 peptides were decreased or present only in the healthy group (CTRL). These peptides are listed in Tables 1 and 2 respectively, clearly showing a significantly increased number of peptides derived from an intrinsic proteolytic activity in HS samples in comparison with CTRL.

Figure 2.

A) Venn diagram of the peptides identified in hemorrhagic (HS) and healthy (CTRL) rats. B) Venn diagram of the proteins identified in hemorrhagic (HS) and healthy (CTRL) rats

Table 1. List of the peptides increased or present only in HS.

Peptides were considered increased if they were present only in either the healthy (CTRL) or hemorrhagic (HS) group or if they showed significant fold change differences between the two groups (> 1.5-fold increase or < 0.67-fold decrease in HS compared to CTRL) (ratio mean LFQ HS/mean LFQ CTRL). The specificity of proteases responsible for the generation of the peptides data set is indicated in the table (column: Selected Proteolytic Enzymes).

| Sequence | ratio HS/CTRL | Proteins | Genes | Selected Proteolytic enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGEQHFKGLVL | 80.28 | P02770 | Alb | chymotrypsin-like |

| IQKTPQIQVY | 28.79 | P07151 | B2m | chymotrypsin-like |

| SLEIPGSSDPNVIPDGDFSSF | 28.62 | M0RB00 | C4 | chymotrypsin-like |

| LTTNPQGDTLDVSF | 25.83 | Q6IRS6 | Fetub | chymotrypsin-like |

| ASTVRPSFSLGNETLKVPLAL | 24.55 | Q5I0D7 | Pepd | chymotrypsin-like |

| ATGKPRYVVLVPSELY | 23.63 | Q63041 | A1m | chymotrypsin-like |

| EVTSDQVANVMWDY | 19.5 | P02651 | Apoa4 | chymotrypsin-like |

| LNGNSKYMVL | 18.79 | Q03626 | Mug1 | chymotrypsin-like |

| EAHKSEIAHRFKDLGEQHFKGLVL | 17.84 | P02770 | Alb | chymotrypsin-like |

| AAPRPPPAISVSVSAPAF | 16.83 | D4A7U1 | Zyx | chymotrypsin-like |

| LQLTGGHEAF | 15.61 | B2GVB9 | Fermt3 | chymotrypsin-like |

| MSKQAFVFPGVSATAY | 15.36 | P48199 | Crp | chymotrypsin-like |

| DAGLTPNNLKPVAAEF | 15.34 | Q7TMC7 | Tf | chymotrypsin-like |

| QKASLEHMVSMQY | 12.56 | D4ACQ4 | RGD15608 | chymotrypsin-like |

| DEPQSQWDRVKDFATVY | 11.55 | P04639 | Apoa1 | chymotrypsin-like |

| LLFGNSKY | 11.35 | Q6IE52 | Mug2 | chymotrypsin-like |

| KIILDPSGSMNIY | 11.14 | Q7TP05 | Cfb | chymotrypsin-like |

| MDLPGQQPVSEQAQQKLPPLAL | 10.72 | Q68FT8 | Serpinf2 | chymotrypsin-like |

| HEDMSKQAFVFPGVSATAY | 7.88 | P48199 | Crp | chymotrypsin-like |

| HPSSPPVVDTTKGKVLGKY | 7.37 | P10959 | Ces1c | chymotrypsin-like |

| SFSYKPRAPSAEVEMTAYVL | 7.23 | Q63041 | A1m | chymotrypsin-like |

| DVQMTQSPSY | 7.14 | P01681 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| QAAETDVQTLFSQY | 7.04 | P04638 | Apoa2 | chymotrypsin-like |

| PVTSVDAAFRGPDSVF | 7.03 | P20059 | Hpx | chymotrypsin-like |

| PNHFRPEGLPEKY | 6.32 | F7EHL9 | Hps5 | chymotrypsin-like |

| SDKPDMAEIEKFDKSKL | 5.03 | P62329 | Tmsb4x | chymotrypsin-like |

| EDVPAADLSDQVPDTDSETRIL | 4.71 | M0RBF1 | C3 | chymotrypsin-like |

| LNGNSKYMVLVPSQL | 3.42 | Q03626 | Mug1 | chymotrypsin-like |

| DLPGQQPVSEQAQQKLPPLAL | 2.54 | Q68FT8 | Serpinf2 | chymotrypsin-like |

| SDKPDMAEIEKF | 1.94 | P62329 | Tmsb4x | chymotrypsin-like |

| KESTLHLVL | 1.61 | F1LML2 | Ubc | chymotrypsin-like |

| AADISQWAGPLSL | P31044 | Pebp1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AALQERLDNVSHTPSSY | Q5U2Z3 | Nap1l4 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AAPAKGENLSL | P27867 | Sord | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AAVVLENGVLSRKLSDFGQETSY | P04176 | Pah | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AEFYGSLEHPQTHY | Q7TMC7 | Tf | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AETDVQTLFSQY | P04638 | Apoa2 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AEVTGLSPGVTYLFKVF | P04937 | Fn1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AGQAFRKFLPLF | P26772 | Hspe1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AGQAFRKFLPLFDRVL | P26772 | Hspe1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AGVLSRDAPDIESIL | O89000 | Dpyd | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AHKSEIAHRFKDLGEQHFKGLVL | P02770 | Alb | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AKLLGLTL | P55159 | Pon1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ALKNVPFRSEVLAWNPDNLADY | Q920L0 | Lcp2 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ALKPLAPLLRGYHVVL | D4AA35 | Asmtl | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ALSMPLNGLKEEDKEPLIEL | G3V8C4 | Clic4 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| APPSFFAQVPQAPPVLVFKL | P13221 | Got1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ARGSVSDEEMMELREAF | Q5XI38 | Lcp1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ASINTDFTLSL | P05545 | Serpina3k | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ASSDIQVKELEKRASGQAFEL | P13668 | Stmn1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ASTVRPSFSLGNETLKVPLALF | Q5I0D7 | Pepd | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ASVLTAQPRLMEPIY | P05197 | Eef2 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ATGKPRYVVLVPSEL | Q63041 | A1m | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ATTFKQDSPGQSSGFVY | P18757 | Cth | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ATTVSTQRGPVY | A2RUW1 | Tollip | chymotrypsin-like | |

| AVYSLSKSY | Q03626 | Mug1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| DEPQSQWDRVKDF | P04639 | Apoa1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| DGILGRDTLPHEDQGKGRQLHSLTL | P05545 | Serpina3k | chymotrypsin-like | |

| DIISNILHNF | D3ZY96 | Ngp | chymotrypsin-like | |

| DIVLTQSPVL | F1LYU4 | chymotrypsin-like | ||

| EAHKSEIAHRFKDLGEQHFKGL | P02770 | Alb | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ELVEAYQEQAKGLLDGGVDILL | G3V8A4 | Mtr | chymotrypsin-like | |

| EMLKGMIMSGMNVAHL | D3ZH80 | LOC689343 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| EMQQQELAQMRQRDANL | M0R4D8 | Taf4a | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ETLKDDTEKLKQLNTEQNIL | Q5FVG2 | Epb41l5 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| FAQVPQAPPVLVFKL | P13221 | Got1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| FGSPLGKDLLFKDSAFGL | Q7TMC7 | Tf | chymotrypsin-like | |

| FIGGDAGDAFDGYDFGDDPSDKF | P02680 | Fgg | chymotrypsin-like | |

| FILKHTGPGILSMANAGPNTNGSQF | M0RCZ9 | Ppia | chymotrypsin-like | |

| FQVAEKPTEVDGGVWSIL | Q5EBC0 | Itih4 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| FRVGPESDKYRLTY | P02680 | Fgg | chymotrypsin-like | |

| FRVGPESDKYRLTYAY | P02680 | Fgg | chymotrypsin-like | |

| FTKTPKFFKPAMPFDL | M0RBF1 | C3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| FTNIHGRGGGALLGDRWIL | D4A1T6 | C1r | chymotrypsin-like | |

| FVLSPEQINAVY | P48199 | Crp | chymotrypsin-like | |

| FYARGNFEAQQRGSGGVW | F7EHL9 | Hps5 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| GFGDLKTPAGLQVLNDYLADKSY | Q7TPK5 | Eef1b2l | chymotrypsin-like | |

| HKSEIAHRFKDLGEQHFKGLVL | P02770 | Alb | chymotrypsin-like | |

| IAHRFKDLGEQHFKGLVL | P02770 | Alb | chymotrypsin-like | |

| IAVDYLNKHLLQGFRQIL | P24090 | Ahsg | chymotrypsin-like | |

| IIGGRNAELGLFPWQAL | Q8CHN8-2 | Masp1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| IVEGWDAEKGIAPWQVML | G3V843 | F2 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| KPRLLLFSPSVVNLGTPLSVGVQL | M0RB00 | C4 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| LDTKSYWKALGISPFHEY | P02767 | Ttr | chymotrypsin-like | |

| LELLDHVL | G3V852 | Tln1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| LGAPQEADASEEGVQRALDF | P14841 | Cst3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| LQIGATTQQAQKLKGEEVAF | P10959 | Ces1c | chymotrypsin-like | |

| LQKPEAELSPSL | P14046 | A1i3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| LQKPEAELSPSLIYDLPGMQDSNF | P14046 | A1i3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| LRSEPLDIKFNKPFILLL | P31211 | Serpina6 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| MEGPAGYLRRASVAQLTQELGTAF | P12928-2 | Pklr | chymotrypsin-like | |

| MEMDKRIY | P49911 | Anp32a | chymotrypsin-like | |

| MEVKPKLY | P14942 | Gsta4 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| MFRNQYDNDVTVWSPQGRIHQIEY | P18420 | Psma1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| MIVESETQSPLF | P17475 | Serpina1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| MMDQARSAFSNLF | G3V679 | Tfrc | chymotrypsin-like | |

| MNAAAEAEFNIL | Q80Z29 | Nampt | chymotrypsin-like | |

| MQKDASSSGFLPSFQHF | P18757 | Cth | chymotrypsin-like | |

| PKPDSEAGTAFIQTQQLHAAMADTF | P11980 | Pkm2 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| PYEIKKVF | Q5RKI0 | Wdr1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| RKLQPNLYVVAELFTGSEDL | D4AEH9 | Agl | chymotrypsin-like | |

| RLLWESGSLL | M0RBF1 | C3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| RVELDTKSYWKALGISPFHEY | P02767 | Ttr | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SEIAHRFKDLGEQHFKGLVL | P02770 | Alb | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SEKKQPVDLGLLEEDDEF | D3ZHW9 | Shfm1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SFSYKPRAPSAEVEMTAY | Q63041 | A1m | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SKPDNPGEDAPAEDMARY | P07808 | Npy | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SLLDEFYKL | Q5M9G3 | Caprin1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SLLFGNSKY | Q6IE52 | Mug2 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SLPEGVVDGIEIY | Q63416 | Itih3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SMTDLLSAEDIKKAIGAF | P02625 | Pvalb | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SPMYSIITPNVLRLESEETF | M0RBF1 | C3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SPTVFRLLWESGSL | M0RBF1 | C3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SPTVFRLLWESGSLL | M0RBF1 | C3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SQADFDKAAEEVKRLKTQPTDEEML | P11030 | Dbi | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SSGNAKIGHPAPSF | Q63716 | Prdx1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| STNESSNSHRGLAPTNVDFAFNL | P31211 | Serpina6 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| SYDRAITVFSPDGHLFQVEY | F1LSQ6 | Psma7 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| TDVANYLDWIQEHTAF | D3ZTE0 | F12 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| TVFRLLWESGSLL | M0RBF1 | C3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| VDIFEPQGISRLDAQASF | B2RYM3 | Itih1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| VDLPGGLHQLSFPLSVEPALGIY | Q63041 | A1m | chymotrypsin-like | |

| VFRLLWESGSLL | M0RBF1 | C3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| VSLEGFTQPVAVF | P10959 | Ces1c | chymotrypsin-like | |

| VTGLSPGVTYLFKVF | P04937 | Fn1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| VVFTANDSGHRHYTIAALLSPYSY | P02767 | Ttr | chymotrypsin-like | |

| VVLSAPAVESELSPRGGEF | Q03626 | Mug1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| VYDAGLTPNNLKPVAAEF | Q7TMC7 | Tf | chymotrypsin-like | |

| WEFWQQDEPQSQWDRVKDF | P04639 | Apoa1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| WTKTLPQKIQELKGSQSKHAEL | D3ZE31 | Ces2i | chymotrypsin-like | |

| YASVLTAQPRLMEPIY | P05197 | Eef2 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| YAVGGRSHKPLDMSKVF | M0RB00 | C4 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| YSIITPNVLRLESEETFIL | M0RBF1 | C3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| YSLAPQIKVIAPWRMPEF | P09034 | Ass1 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| YVRPGGGFVPNFQL | P23764 | Gpx3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| YVGRPLVSQYNV | 13.72 | Q9WUW3 | Cfi | elastase-like |

| FDWISYYVGRPLVSQYNV | Q9WUW3 | Cfi | ||

| FRLLGNMIV | P02091 | Hbb | ||

| MATPVVTKTAWKLQEIV | Q4VFZ4 | Katnb1 | ||

| FAIEEYSAPFSSDSEQGNA | 6.87 | Q63041 | A1m | elastase-like/MMPs |

| YPSKPDNPGEDAPAEDMA | 4.16 | P07808 | Npy | elastase-like/MMPs |

| FLSRLMSPEEKPAPAA | 1.92 | P04638 | Apoa2 | elastase-like/MMPs |

| AAGTLYTYPENWRAFKALIA | Q68FR6 | Eef1g | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| AEVVFTANDSGHRHYTIA | P02767 | Ttr | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| AGQAFRKFLPLFDRVLVERSA | P26772 | Hspe1 | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| ASDPILYRPVA | P11980 | Pkm2 | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| DAGLTPNNLKPVA | Q7TMC7 | Tf | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| FDKFTWSSLMMSQVVNPA | P31211 | Serpina6 | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| INYYDMNAANVGWNGSTFA | D3ZE63 | LOC686548 | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| MDFLSRLMSPEEKPAPAA | P04638 | Apoa2 | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| MPLFFRKRKPSEEARKRLEYQMCLA | D3ZI42 | Lrsam1 | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| PSKPDNPGEDAPAEDMA | P07808 | Npy | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| SETAPAETTAPAPVEKSPA | D3ZBN0 | Hist1h1b | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| SFSYKPRAPSAEVEMTA | Q63041 | A1m | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| VVFTANDSGHRHYTIA | P02767 | Ttr | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| VVYPWTQRYFDSFGDLSSA | P02091 | Hbb | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| YETDEFAIEEYSAPFSSDSEQGNA | Q63041 | A1m | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| KPRLLLFSPSVVNLGTPLSVG | 34.99 | M0RB00 | C4 | elastase-like/MMPs |

| EAHKSEIAHRFKDLGEQHFKG | P02770 | Alb | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| FGIDKDAIVQAVKGLVTKG | G3V826 | Tkt | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| HPSSPPVVDTTKGKVLGKYVSLEG | P10959 | Ces1c | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| LLLFSPSVVNLGTPLSVG | M0RB00 | C4 | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| LVQKDTVVKPVIVEPEG | Q63041 | A1m | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| VPETGRKDTVVKVLIVEPEG | Q03626 | Mug1 | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| VQKDTVVKPVIVEPEG | Q63041 | A1m | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| SDKPDMAEIEKFDKS | 34.7 | P62329 | Tmsb4x | MMPs |

| VQEQVQEQVQPKPLES | 18.24 | P02651 | Apoa4 | MMPs |

| NPLPSKETIEQEKQAGES | 1.83 | P62329 | Tmsb4x | MMPs |

| AAVSKIAWHVIRNS | Q9EQV9 | Cpb2 | MMPs | |

| EALAAVSKIAWHVIRNS | Q9EQV9 | Cpb2 | MMPs | |

| EKNPLPSKETIEQEKQAGES | P62329 | Tmsb4x | MMPs | |

| EQVQEQVQPKPLES | P02651 | Apoa4 | MMPs | |

| ETQEKNPLPSKETIEQEKQAGES | P62329 | Tmsb4x | MMPs | |

| KNPLPSKETIEQEKQAGES | P62329 | Tmsb4x | MMPs | |

| QVQEQVQEQVQPKPLES | P02651 | Apoa4 | MMPs | |

| TVFRLLWES | M0RBF1 | C3 | MMPs | |

| ALLSPYSYSTTAVVSNPQN | 1.77 | P02767 | Ttr | MMPs |

| FYIMPVMNVDGYDYTWKKNRMWRKN | Q9EQV9 | Cpb2 | MMPs | |

| LNETGDEPFQYKN | P09606 | Glul | MMPs | |

| SFFNLTMKEMVKDVLRGQN | B1WC01 | Kif20a | MMPs | |

| SFSYKPRAPSAEVE | 5.16 | Q63041 | A1m | MMPs |

| AALKDQLIVNLLKE | P04642 | Ldha | MMPs | |

| AMQKIFAREILDSRGNPTVE | P15429 | Eno3 | MMPs | |

| ASKRALVILAKGAEEME | O88767 | Park7 | MMPs | |

| DFESEFVYMLNQQCFKFLQMKRETE | F1LW73 | MMPs | ||

| DGLFSFFKE | F7EHL9 | Hps5 | MMPs | |

| DVGSYQEKVDVVLGPIQLQSPSKE | Q8CIZ5 | Dmbt1 | MMPs | |

| EHICMSEHMCMSEHMCLSEHMCMSE | M0R8P2 | MMPs | ||

| MWASCCNWFCLDGQPE | Q8CIN9 | Rffl | MMPs | |

| QSLLNQQMMGKKQTLQRPTME | F1M3B2 | Maml2 | MMPs | |

| RVELDTKSYWKALGISPFHEYAE | P02767 | Ttr | MMPs | |

| SDKPDMAEIEKFDKSKLKKTE | P62329 | Tmsb4x | MMPs | |

| SDKPDMAEIEKFDKSKLKKTETQE | P62329 | Tmsb4x | MMPs | |

| TSQIRQNYSTEVE | Q7TP54 | Fam65b | MMPs | |

| VDYSVWDHIE | Q63692 | Cdc37 | MMPs | |

| VQKDTVVKPVIVEPE | Q63041 | A1m | MMPs | |

| SETQSPLFVGKVIDPTR | 20.81 | P17475 | Serpina1 | trypsin-like |

| SDKPDMAEIEKFDKSK | 3.33 | P62329 | Tmsb4x | trypsin-like |

| MIVESETQSPLFVGKVIDPTR | 3.29 | P17475 | Serpina1 | trypsin-like |

| DSEVTSHSSQDPLVVQEGSR | 3.15 | Q6P734 | Serping1 | trypsin-like |

| EDVPAADLSDQVPDTDSETR | 1.94 | M0RBF1 | C3 | trypsin-like |

| SFSQVTPAQMDLVFQR | 1.91 | Q64602 | Aadat | trypsin-like |

| SETAPAAPAAPAPAEKTPIK | 1.51 | P15865 | Hist1h1c | trypsin-like |

| DLEAMRMQTEMELRMFRQNEFMYHK | D4A3D2 | Smyd1 | trypsin-like | |

| IISDTETAIAPFLAKIFNPK | P09006 | Serpina3n | trypsin-like | |

| LASVSTVLTSKYR | P01946 | Hba1 | trypsin-like | |

| LTSVPRYSMWFNQIMK | G3V8K8 | Proz | trypsin-like | |

| SDKPDMAEIEKFDKSKLK | P62329 | Tmsb4x | trypsin-like | |

| SETAPAAPAAPAPVEKTPVK | M0R7B4 | LOC684828 | trypsin-like | |

| SPTVFRLLWESGSLLR | M0RBF1 | C3 | trypsin-like | |

| SSPTVFRLLWESGSLLR | M0RBF1 | C3 | trypsin-like | |

| TVFRLLWESGSLLR | M0RBF1 | C3 | trypsin-like | |

| VFRLLWESGSLLR | M0RBF1 | C3 | trypsin-like | |

| VLLAYLTSASSRPTR | Q63041 | A1m | trypsin-like | |

| YPSKPDNPGEDAPAEDMAR | P07808 | Npy | trypsin-like | |

| FVKRQFMNKSLSGPGQ | 31.94 | B2GV73 | Arpc3 | |

| VITDNNGQSVFFMGKVTNPM | 14.32 | P05545 | Serpina3k | |

| WTELLAKNPPQTEHTEHT | 12.73 | P10959 | Ces1c | |

| MIVESETQSPLFVGKVID | 7.35 | P17475 | Serpina1 | |

| VLLAYLTSASSRPT | 6.74 | Q63041 | A1m | |

| SDKPDMAEIEKFDKSKLKKT | 6.56 | P62329 | Tmsb4x | |

| YQPVTMVTSQGQVVTQAIPQ | 6.14 | A0A096MJK | LOC100364346 | |

| LAYLTSASSRPT | 3.51 | Q63041 | A1m | |

| GEDAAQAEKFQHPNTD | 2.79 | Q66H98 | Sdpr | |

| AQASLGEYLFERLTLKHD | Q7TP54 | Fam65b | ||

| ASGVAVSDGVIKVFND | M0R6D6 | Cfl1 | ||

| DEPQSQWDRVKDFATVYVD | P04639 | Apoa1 | ||

| EEVVSESFASGP | P02783 | Svs4 | ||

| EQRLNRRRQNEIMAKIQAAIIQI | Q9R095-2 | Spef2 | ||

| FAQVPQAPPVLVFKLIAD | P13221 | Got1 | ||

| FLFRDGDILGKYVD | P26772 | Hspe1 | ||

| GEDAAQAEKFQHPNT | Q66H98 | Sdpr | ||

| GGGEMNPFETKVKTRIT | P04812 | Svs5 | ||

| GGWVLVRDLLIPSNNMLYIVANGMI | Q2TGI4 | Zdhhc25 | ||

| GMLNQQLTPVAGMMGGYP | D3ZT52 | Pbrm1 | ||

| INDFHRAI | F1LSG1 | Kcnt1 | ||

| IQEVTINQSLLTPMNLQIDPTIQ | Q4FZU2 | Krt6a | ||

| LAFQMQYQMAKYQAP | M0RAT6 | Tmed8 | ||

| LGRFLESANMFFMVNQKVII | E9PTA3 | LOC502618 | ||

| LVITDNNGQSVFFMGKVTNPM | P05545 | Serpina3k | ||

| MDAGLTFKTNQGLQTDQRED | M0RBF1 | C3 | ||

| MIVESETQSPLFVGKVIDPT | P17475 | Serpina1 | ||

| MKLTSEKLPKNPFSLSQYAAKQ | G3V9B8 | Lrp2bp | ||

| MRDKNRKPVVMKIKPDEIQQNGQT | D3ZZW3 | Entpd4 | ||

| MTAYVLLAYLTSASSRPT | Q63041 | A1m | ||

| SDKPDMAEIEKFDKSKLKKTET | P62329 | Tmsb4x | ||

| SDKPDMAEIEKFDKSKLKKTETQ | P62329 | Tmsb4x | ||

| SPMYSIITPNVLRLESEET | M0RBF1 | C3 | ||

| TQLKRKENEIELSLLQLREQQAT | D3Z8G3 | Rpgrip1l | ||

| TRAGMERWRDRLALVT | G3V978 | Dhrs11 | ||

| VAQASLGEYLFERLTLKHD | Q7TP54 | Fam65b | ||

| VKVLDAVRGSPAVD | P02767 | Ttr | ||

| VVLARLTAQPAPSPED | Q03626 | Mug1 | ||

| WKQQVMTTVQNMQHESAQLQEELH | D4ABD7 | Trip11 | ||

| YPSKPDNPGEDAPAED | P07808 | Npy | ||

| YVLLAYLTSASSRPT | Q63041 | A1m |

Table 2. List of the peptides decreased or present only in CTRL.

Peptides were considered increased if they were present only in either the healthy (CTRL) or hemorrhagic (HS) group or if they showed significant fold change differences between the two groups (> 1.5-fold increase or < 0.67-fold decrease in HS compared to CTRL) (ratio mean LFQ HS/mean LFQ CTRL). The specificity of proteases responsible for the generation of the peptides data set is indicated in the table (column: Selected Proteolytic Enzymes).

| sequence | ratio HS/CTRL | Proteins | Genes | Selected Proteolytic enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGNFIDQTRVLNLGPITRQGVQA | 0.66 | P27590 | Umod | elastase-like/MMPs |

| TVIDQNRDGIIDKEDLRDT | 0.66 | P04466 | Mylpf | |

| ELEAMSRYTSPVNPAV | 0.55 | D3ZS52 | LOC10036304 | elastase-like |

| TAPKIPEGEKVDFDDIQK | 0.45 | P09739-3; | Tnnt3 | trypsin-like |

| MEKEEETTREL | 0.35 | M0R9D5 | Ahnak | chymotrypsin-like |

| GTTSEFIEAGGDIR | 0.31 | P06399;Q | Fga | trypsin-like |

| PRLLLLLLLLPSLAWG | 0.26 | B0BN16 | Igfbpl1 | elastase-like/MMPs |

| DISNADRLGSSEVEQVQ | 0.25 | P00564 | Ckm | |

| GQGLEWIGRIGPGSGDTNY | 0.24 | M0RBX3 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| WESGPEDQLTTPTLEP | 0.24 | P06759 | Apoc3 | |

| ELEEAEERADIAESQVN | 0.22 | F1LRV9;G | Myh4;Myh8;M | elastase-like/MMPs |

| HELEEAEERADIAESQVN | 0.22 | F1LRV9;G | Myh4;Myh8;M | elastase-like/MMPs |

| TTALQPWHGAESKTDDSAL | 0.21 | Q99MH3 | Hamp | chymotrypsin-like |

| TTALQPWHGAESKTDDSA | 0.21 | Q99MH3 | Hamp | elastase-like/MMPs |

| TTALQPWHGAES | 0.19 | Q99MH3 | Hamp | elastase-like/MMPs |

| FEVTNLNMKSGMSLKIKGKIHN | 0.19 | Q9Z144 | Lgals2 | elastase-like/MMPs |

| MFRLLTACWSRQKATEGKQ | 0.19 | Q6AXT3 | Arl13a | |

| ATTDSDKVDLSIAR | 0.16 | P14480 | Fgb | trypsin-like |

| TGTTSEFIEAGGDIR | 0.16 | P06399;Q | Fga | trypsin-like |

| SIASTTVPLENQ | 0.16 | P02650 | Apoe | |

| PTIETTEFSDFDLLDALS | 0.15 | P08934;M | Kng1 | elastase-like/MMPs |

| MLRLGALRLRGLALRS | 0.15 | Q5RKL4;Q | Dmgdh | elastase-like/MMPs |

| ETDAIQRTEELEEA | 0.14 | G3V885;P | Myh6;Myh7;M | elastase-like/MMPs |

| ADTGTTSEFIEAGGDIRGPRIVE | 0.14 | P06399;Q | Fga | elastase-like/MMPs |

| GFMGVMNNMRKQRTLCDVI | 0.11 | Q5XHZ6 | Klhl7 | |

| ADTGTTSEFIEAGGD | 0.1 | P06399;Q | Fga | |

| ADTGTTSEFIEAGGDIR | 0.09 | P06399;Q | Fga | trypsin-like |

| DTGTTSEFIEAGGDIR | 0.08 | P06399;Q | Fga | trypsin-like |

| TRQTTALQPWHGAES | 0.06 | Q99MH3 | Hamp | elastase-like/MMPs |

| MGTAVLRKLQLVLLL | 0.05 | B2RYM1 | Angptl6 | chymotrypsin-like |

| DIENPSSHVPEF | P06399;Q | Fga | chymotrypsin-like | |

| EEAEEQSNVNLAKF | F1LRV9;F1 | Myh4;Myh8 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| EQIQYRNNGVSSKQLMVF | P32232-2 | Cbs | chymotrypsin-like | |

| KENTIHLTL | Q921A3 | Ubd | chymotrypsin-like | |

| MMNFLRRRLSDSSFIANLPNGY | Q63537;Q | Syn2 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| MSPASLTFFCIGL | M0R8A3; | Gp6 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| TMMGKQEESQAGIIPQL | O88658;O | Kif1b | chymotrypsin-like | |

| VGPIQSLQM | D3ZTA8 | Rbm33 | chymotrypsin-like | |

| ARNKMLTGVVGLVL | M0RDH5 | chymotrypsin-like | ||

| TKYETDAIQRTEELEEA | G3V885;P | Myh6;Myh7;M | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| ADTGTTSEFIEAGGDIRG | P06399;Q | Fga | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| SQDAIMDAIAGQAQAQG | A0A096M | Ldb3 | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| EGELEVTDQLPGQS | P02650 | Apoe | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| AGSVADSDAVVKLDDGHLN | B4F7A3 | Lgalsl | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| KNKMTKEQYIKMNRGIN | D4A631;Q | Arfgef1;Arfgef | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| LEEAEERADIAESQVN | F1LRV9;G | Myh4;Myh8;M | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| VIDLFGNEHDNFTKNLEN | D4A3H4 | RGD1307621 | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| SQMPVLGKSSLRNVE | E9PSU2 | Donson | elastase-like/MMPs | |

| DAGAGIALNDNFVK | M0R6I3;M | RGD1560797; | trypsin-like | |

| DIDPEDEELELGPR | P31394;Q | Proc | trypsin-like | |

| DLEEATLQHEATAATLR | F1LRV9;G | Myh4;Myh13 | trypsin-like | |

| TDSDKVDLSIAR | P14480 | Fgb | trypsin-like | |

| DGPEGPKGRGGPNGDPGPL | Q9JI03;G3 | Col5a1 | ||

| EHVQYMAEVIERLSNEPL | D3ZWJ0 | Gmnn | ||

| MEHTGQYLHLVFLMT | Q5HZW9 | Evi2a | ||

| QQQQQQQMQQLQQQ | F1LXK8 | LOC100362634 | ||

| SRPSSKTSHRQQEEVKAPQMSQ | D3ZK09 | Scyl3 | ||

| TAPKIPEGEKVDFDDIQ | P09739-3; | Tnnt3 | ||

| TEEDDPGSSALLDTVQEH | G3V8D4 | Apoc2 | ||

| VELGNDATDIEDD | P06866-2; | Hp |

Computational identification of secreted and transmembrane proteins by means of prediction tools including Secreome P, SignalP, Phobius in combination with TMHMM allowed determination of the proteins from which the peptides originated (Figure 2B and Tables 3 and 4). The Tables report also the analysis carried out using the reference Plasma Proteome Database (http://www.plasmaproteomedatabase.org/), which contains a list of the plasma and serum proteins from healthy individuals. Among the peptides which increased or were present only in HS samples, 73% originated from proteins described as secreted or transmembrane while 23% (60 peptides out of 256) originated from 51 proteins out of 124 (41%) that are classified as non secreted. Moreover, 72% of the proteins have been previously reported in plasma according to the Plasma Proteome Database.

Table 3. Proteins increased or present only in HS from which the peptides in Table 1 originate.

List of the proteins predicted to be secreted/transmembrane or non-secreted by Perseus Annotation, Secreome P, SignalP, Phobius and TMHMM software or previously reported in plasma according to the Plasma Proteome Database.

| Protein names | Protein IDs | Genes | transmembrane/secreted | non secreted | plasma proteome DB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-1-inhibitor 3 | P14046 | A1i3 | x | ||

| Alpha-1-macroglobulin | Q63041 | A1m | x | ||

| Amylo-1, 6-glucosidase | D4AEH9 | Agl | x | x | |

| Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein | P24090 | Ahsg | x | x | |

| Serum albumin | P02770 | Alb | x | x | |

| Acidic leucine-rich nuclear phosphoprotein 32 family | P49911 | Anp32a | x | x | |

| Apolipoprotein A-I | P04639 | Apoa1 | x | x | |

| Apolipoprotein A-II | P04638 | Apoa2 | x | x | |

| Apolipoprotein A-IV | P02651 | Apoa4 | x | x | |

| Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 3 | B2GV73 | Arpc3 | x | x | |

| Protein Asmtl | D4AA35 | Asmtl | x | x | |

| Argininosuccinate synthase | P09034 | Ass1 | x | x | |

| Beta-2-microglobulin | P07151 | B2m | x | x | |

| Protein C1r | D4A1T6 | C1r | x | x | |

| Complement C3 | M0RBF1 | C3 | x | x | |

| Complement C4 | M0RB00 | C4 | x | x | |

| Caprin-1 | Q5M9G3 | Caprin1 | x | ||

| Hsp90 co-chaperone Cdc37 | Q63692 | Cdc37 | x | x | |

| Carboxylesterase 1C | P10959 | Ces1c | x | ||

| Protein Ces2a | D3ZE31 | Ces2i | x | ||

| Da1-24 | Q7TP05 | Cfb | x | x | |

| Complement factor I | Q9WUW3 | Cfi | x | x | |

| Cofilin-1 | M0R6D6 | Cfl1 | x | x | |

| Chloride intracellular channel protein 4 | G3V8C4 | Clic4 | x | x | |

| Carboxypeptidase B2 | Q9EQV9 | Cpb2 | x | x | |

| C-reactive protein | P48199 | Crp | x | x | |

| Cystatin-C | P14841 | Cst3 | x | x | |

| Cystathionine gamma-lyase | P18757 | Cth | x | x | |

| Protein Dhrs11 | G3V978 | Dhrs11 | x | ||

| Deleted in malignant brain tumors 1 protein | Q8CIZ5 | Dmbt1 | x | x | |

| Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase [NADP(+)] | O89000 | Dpyd | x | x | |

| Ac2-067 | Q7TPK5 | Eef1b2l | x | x | |

| Elongation factor 1-gamma | Q68FR6 | Eef1g | x | x | |

| Elongation factor 2 | P05197 | Eef2 | x | x | |

| Beta-enolase | P15429 | Eno3 | x | x | |

| Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 4 | D3ZZW3 | Entpd4 | x | x | |

| Band 4.1-like protein 5 | Q5FVG2 | Epb41l5 | x | x | |

| Coagulation factor XII | D3ZTE0 | F12 | x | x | |

| Prothrombin | G3V843 | F2 | x | x | |

| Ferritin | Q7TP54 | Fam65b | x | ||

| Fermt3 protein | B2GVB9 | Fermt3 | x | x | |

| Fetuin-B | Q6IRS6 | Fetub | x | x | |

| Fibrinogen gamma chain | P02680 | Fgg | x | x | |

| Fibronectin;Anastellin | P04937 | Fn1 | x | x | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | P13221 | Got1 | x | x | |

| Glutathione peroxidase 3 | P23764 | Gpx3 | x | x | |

| Glutathione S-transf. alpha-4 | P14942 | Gsta4 | x | ||

| Hemoglobin subunit alpha-1/2 | P01946 | Hba1 | x | x | |

| Hemoglobin subunit beta-1 | P02091 | Hbb | x | x | |

| Histone H1.5 | D3ZBN0 | Hist1h1b | x | x | |

| Serum amyloid A protein | F7EHL9 | Hps5 | x | x | |

| Hemopexin | P20059 | Hpx | x | x | |

| 10 kDa heat shock protein | P26772 | Hspe1 | x | x | |

| Itih1 | B2RYM3 | Itih1 | x | x | |

| Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H3 | Q63416 | Itih3 | x | x | |

| Inter alpha-trypsin inhibitor, heavy chain 4 | Q5EBC0 | Itih4 | x | x | |

| Katanin p80 WD40 repeat-containing subunit B1 | Q4VFZ4 | Katnb1 | x | x | |

| Potassium channel subfamily T member 1 | F1LSG1 | Kcnt1 | x | x | |

| Kinesin-like protein | B1WC01 | Kif20a | x | x | |

| Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 6A | Q4FZU2 | Krt6a | x | x | |

| Lymphocyte cytosolic protein 1 | Q5XI38 | Lcp1 | x | x | |

| Lymphocyte cytosolic protein 2 | Q920L0 | Lcp2 | x | ||

| Protein Pknox2 | A0A096MJK1 | LOC100364346 | x | ||

| Protein LOC502618 | E9PTA3 | LOC502618 | x | ||

| Protein LOC684828 | M0R7B4 | LOC684828 | x | ||

| Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | D3ZE63 | LOC686548 | x | x | |

| Pyruvate kinase | D3ZH80 | LOC689343 | x | ||

| LRP2-binding protein | G3V9B8 | Lrp2bp | x | ||

| Protein Lrsam1 | D3ZI42 | Lrsam1 | x | x | |

| Protein Maml2 | F1M3B2 | Maml2 | x | ||

| Mannan-binding lectin serine protease 1 | Q8CHN8-2 | Masp1 | x | x | |

| Methionine synthase | G3V8A4 | Mtr | x | x | |

| Murinoglobulin-1 | Q03626 | Mug1 | x | ||

| Murinoglobulin-2 | Q6IE52 | Mug2 | x | ||

| Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase | Q80Z29 | Nampt | x | x | |

| Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 4 | Q5U2Z3 | Nap1l4 | x | x | |

| Neutrophilic granule protein (P | D3ZY96 | Ngp | x | ||

| Pro-neuropeptide Y | P07808 | Npy | x | x | |

| Phenylalanine-4-hydroxylase | P04176 | Pah | x | x | |

| Protein DJ-1 | O88767 | Park7 | x | x | |

| Protein Pbrm1 | D3ZT52 | Pbrm1 | x | x | |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 | P31044 | Pebp1 | x | x | |

| Xaa-Pro dipeptidase | Q5I0D7 | Pepd | x | x | |

| Pyruvate kinase PKLR | P12928-2 | Pklr | x | x | |

| Pyruvate kinase M1/M2 | P11980 | Pkm2 | x | ||

| Serumparaoxonase/arylestera se1 | P55159 | Pon1 | x | x | |

| Pept.-prolyl cis-trans isomA | P10111 | Ppia | x | x | |

| Peroxiredoxin-1 | Q63716 | Prdx1 | x | x | |

| Protein Proz | G3V8K8 | Proz | x | x | |

| Proteas. Sub. alpha type-1 | P18420 | Psma1 | x | x | |

| Proteas. sub. alpha type | F1LSQ6 | Psma7 | x | x | |

| Parvalbumin alpha | P02625 | Pvalb | x | ||

| E3 ubiq.-prot. ligase rififylin | Q8CIN9 | Rffl | x | ||

| Protein Zc3h12b | D4ACQ4 | RGD1560891 | x | ||

| Protein Rpgrip1l | D3Z8G3 | Rpgrip1l | x | ||

| Alpha-1-antiproteinase | P17475 | Serpina1 | x | x | |

| Ser. Prot. inhibitor A3K | P05545 | Serpina3k | x | ||

| Ser. Prot. inhibitor A3N | P09006 | Serpina3n | x | ||

| Corticosteroid-binding globulin | P31211 | Serpina6 | x | x | |

| Protein Serpinf2 | Q68FT8 | Serpinf2 | x | x | |

| Plasma protease C1 inhib. | Q6P734 | Serping1 | x | x | |

| Protein Shfm1 | D3ZHW9 | Shfm1 | x | ||

| Protein Smyd1 | D4A3D2 | Smyd1 | x | x | |

| Sorbitol dehydrogenase | P27867 | Sord | x | x | |

| Q9R095-2 | Spef2 | x | |||

| Stathmin | P13668 | Stmn1 | x | x | |

| Sem. ves. Secr. protein 4 | P02783 | Svs4 | x | ||

| Sem. ves. Secr. prot. 5 | P04812 | Svs5 | x | ||

| Serotransferrin | Q7TMC7 | Tf | x | x | |

| Transferrin rec. protein 1 | G3V679 | Tfrc | x | x | |

| Transketolase | G3V826 | Tkt | x | x | |

| Protein Tln1 | G3V852 | Tln1 | x | x | |

| Protein Tmed8 | M0RAT6 | Tmed8 | x | ||

| Thymosin beta-4 | P62329 | Tmsb4x | x | x | |

| Toll-interacting protein | A2RUW1 | Tollip | x | x | |

| Protein Trip11 | D4ABD7 | Trip11 | x | x | |

| Transthyretin | P02767 | Ttr | x | x | |

| WD repeat-cont. protein 1 | Q5RKI0 | Wdr1 | x | x | |

| Palmitoyltransferase | Q2TGI4 | Zdhhc25 | x | ||

| Protein Zyx | D4A7U1 | Zyx | x | x | |

| Uncharacterized protein | F1LW73 | x | |||

| Uncharacterized protein | F1LYU4 | x | |||

| Uncharacterized protein | M0R4D8 | Taf4a | x | ||

| Ig kappa chain V region S211 | P01681 | x |

Table 4. Proteins decreased or present only in CTRL from which the peptides in Table 2 originate.

List of the proteins predicted to be secreted/transmembrane or non-secreted by Perseus Annotation, Secreome P, SignalP, Phobius and TMHMM software or previously reported in plasma according to the Plasma Proteome Database.

| Protein names | Protein IDs | Genes | transmembrane/secreted | non secreted | plasma proteome DB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Ahnak | M0R9D5 | Ahnak | x | x | |

| Angiopoietin-like 6 | B2RYM1 | Angptl6 | x | x | |

| Apolipoprotein C-II | G3V8D4 | Apoc2 | x | x | |

| Apolipoprotein C-III | P06759 | Apoc3 | x | x | |

| Apolipoprotein E | P02650 | Apoe | x | x | |

| Brefeldin A-inhibited guanine nucleotide-exchange protein 1 | D4A631 | Arfgef1 | x | x | |

| ADP-ribosylation factor-like protei | Q6AXT3 | Arl13a | x | ||

| Cystathionine beta-synthase | P32232-2 | Cbs | x | x | |

| Creatine kinase M-type | P00564 | Ckm | x | x | |

| Collagen alpha-1(V) chain | Q9JI03 | Col5a1 | x | x | |

| Dimethylglycine dehydrogenase | Q5RKL4 | Dmgdh | x | x | |

| Protein Donson | E9PSU2 | Donson | x | x | |

| Ecotropic viral integration site 2A | Q5HZW9 | Evi2a | x | x | |

| Fibrinogen alpha chain | P06399 | Fga | x | x | |

| Fibrinogen beta chain | P14480 | Fgb | x | x | |

| Geminin (Predicted) | D3ZWJ0 | Gmnn | x | x | |

| Protein Gp6 | M0R8A3 | Gp6 | x | ||

| Hepcidin | Q99MH3 | Hamp | x | ||

| Haptoglobin | P06866-2 | Hp | x | x | |

| Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-like 1 | B0BN16 | Igfbpl1 | x | ||

| Kinesin-like protein KIF1B | O88658 | Kif1b | x | x | |

| Kelch-like protein 7 | Q5XHZ6 | Klhl7 | x | ||

| Kininogen-1 | P08934 | Kng1 | x | x | |

| Protein Ldb3 | A0A096MKD | Ldb3 | x | x | |

| Galectin-2 | Q9Z144 | Lgals2 | x | ||

| Galectin | B4F7A3 | Lgalsl | x | x | |

| Histone-lysine N-methyltransferas | F1LXK8 | OC100362634 | x | ||

| Myosin-4 | F1LRV9 | Myh4 | x | x | |

| Myosin regulatory light chain 2 | P04466 | Mylpf | x | x | |

| Vitamin K-dependent protein C | P31394 | Proc | x | ||

| Protein Rbm33 | D3ZTA8 | Rbm33 | x | ||

| Uncharacterized protein | D4A3H4 | RGD1307621 | x | ||

| Protein Scyl3 | D3ZK09 | Scyl3 | x | ||

| Synapsin-2 | Q63537 | Syn2 | x | ||

| Troponin T | P09739-3 | Tnnt3 | x | ||

| Ubiquitin D | Q921A3 | Ubd | x | ||

| Uromodulin |

P27590 M0RDH5 |

Umod | x x |

x | |

| Uncharacterized protein | M0RBX3 | x |

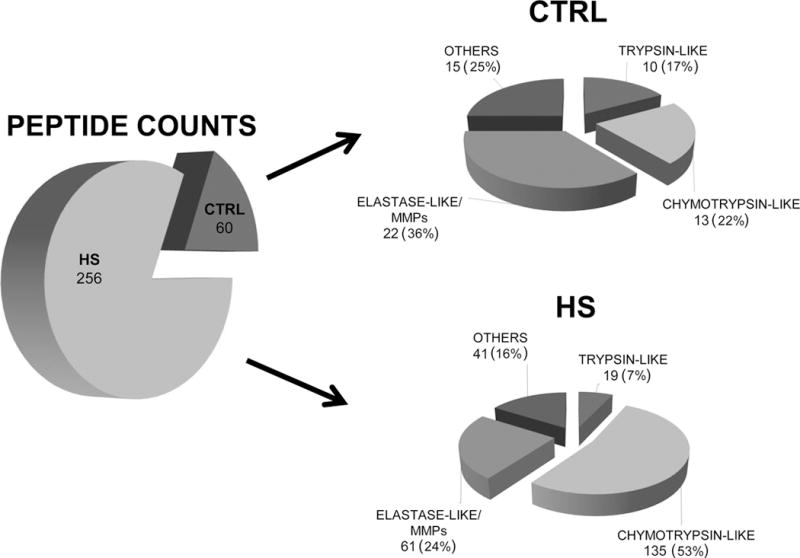

B. Proteolytic activity

A higher protease activity was found in plasma samples following hemorrhagic shock. In particular, the analyses took into account, as possible effector enzymes for the previously described proteolysis, the main intestinal serine proteases (trypsin-like, chymotrypsin-like and elastase-like enzymes) and the most common MMPS (i.e. MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-14). Both those peptides, which were increased or present only in the HS group, and peptides which were increased or present only in the CTRL group were examined, taking into account the C-terminus of each peptide and the cleavage site specificities of the proteases. In this way, it was possible to elaborate on the possible families of enzymes responsible for the cleavage of the proteins listed in the Tables and the subsequent generation of the related peptides. This analysis showed a huge increase in peptides generated by all proteolytic enzymes examined, in particular a significant increase of peptides possibly generated by chymotryptic-like enzymes: 53% in post-shock plasma compared to 22% in control, (Fisher’s exact test p value of 8.06E-06) (Figure 3 and Table 5).

Figure 3. Pie chart showing the number and the % of peptides in plasma samples of CTRL and HS.

The analysis was carried out both on peptides increased and present only in HS group (Table 1) and peptides decreased in HS and present only in healthy group (Table 2) focusing on the cleavage site specificities of the main serine proteases potentially derived from the intestine (trypsin-like, chymotrypsin-like and elastase-like enzymes) and on the most common MMPS: (i.e. MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9, and MMP-14)

Table 5. Plasma protease activity.

The contribution of a specific protease was calculated as the relative proportion between the number of peptides increased and present only in HS and on peptides decreased in HS and present only in CTRL and the total number of peptides present in the HS or CTRL sample.

| HS

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digestive protease | Cleavage site C-term | peptide count (tot 256) | % | Total % |

| Trypsin-like | K (Lys) | 7 | 2.7 | 7 |

| R (Arg) | 12 | 4.7 | ||

| Chymotrypsin-like | W (Trp) not before P | 1 | 0.4 | 53 |

| Y (Tyr) not before P | 39 | 15.2 | ||

| F (Phe) not before P | 37 | 14.5 | ||

| L (Leu) not before P | 58 | 22.7 | ||

| M (Met) not before P | / | |||

| Elastase-like and Metalloprotease (MMPs) | A (Ala) | 18 | 7.0 | 24 |

| G (Gly) | 8 | 3.1 | ||

| V (Val) | 4 | 1.6 | ||

| S (Ser) | 11 | 4.3 | ||

| N (Asn) | 4 | 1.6 | ||

| E (Glu) | 16 | 6.3 | ||

| CTRL

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digestive protease | Cleavage site C-term | peptide count (tot 60) | % | Total % |

| Trypsin-like | K (Lys) | 2 | 3.3 | 17 |

| R (Arg) | 8 | 13.3 | ||

| Chymotrypsin-like | W (Trp) not before P | / | 22 | |

| Y (Tyr) not before P | 2 | 3.3 | ||

| F (Phe) not before P | 3 | 5.0 | ||

| L (Leu) not before P | 7 | 11.7 | ||

| M (Met) not before P | 1 | 1.7 | ||

| Elastase-like and Metalloprotease (MMPs) | A (Ala) | 4 | 6.7 | 36 |

| G (Gly) | 3 | 5.0 | ||

| V (Val) | 1 | 1.7 | ||

| S (Ser) | 5 | 8.3 | ||

| N (Asn) | 7 | 11.7 | ||

| E (Glu) | 2 | 3.3 | ||

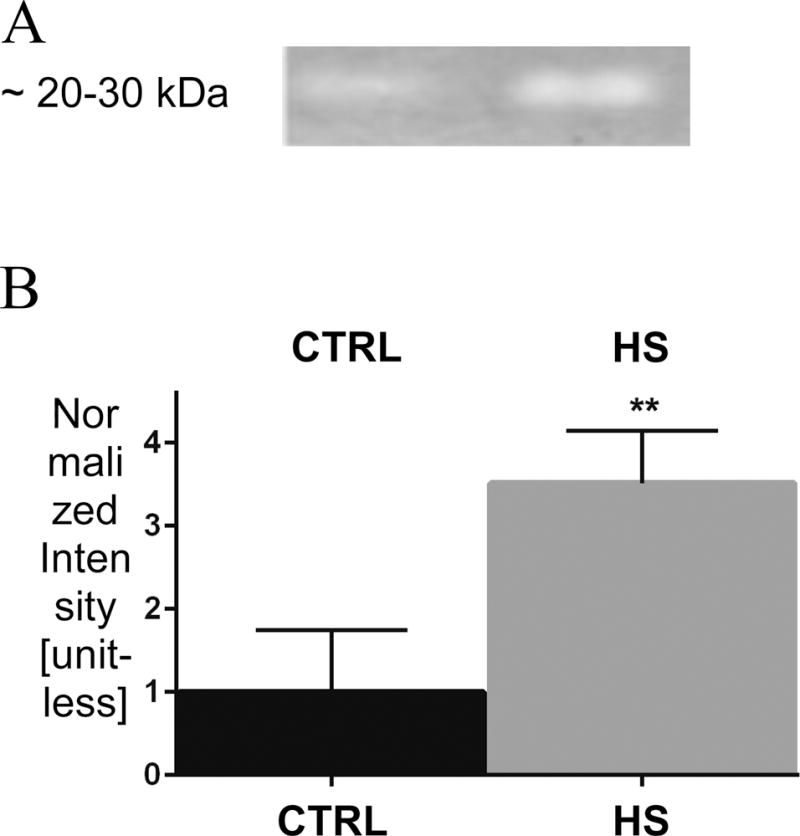

Consistent with the results from the peptidomic analysis, zymography demonstrated a significant increase in serine-protease activity in HS compared to CTRL plasma, with increased activity at a molecular weight compatible with that expected for chymotrypsin (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Plasma serine protease activity by gelatin zymography (n = 3 rats/group).

(A) Serine protease activity band (~ 20–30 kDa) and relevant statistics (B) **p < 0.01 CTRL vs. HS.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this work is that plasma displays an increase in peptides possibly generated by serine proteases after hemorrhagic shock, linking proteases to the larger presence of circulating peptides. Our data support and quantitatively confirm for the first time the hypothesis of extensive, system-wide proteolytic cleavage as part of the pathologic phenomena occurring in shock.

The importance of proteomics as a tool to shed light on the mechanisms underlying cardiovascular disease, and to propose biomarkers for early diagnosis and monitoring of the responsiveness to therapy has already been recognized [6, 17, 18] but, to our knowledge, no systematic study has utilized a peptidomic approach to investigate systemic proteolysis in the general and highly complex context of the possible pathological mechanisms taking place in shock. Therefore, a high-throughput mass spectroscopy-based approach as the peptidomic one described in this work appeared ideal to quantitatively investigate the problem of enzymatic proteolysis in hemorrhagic shock.

Several studies have examined lymph proteins in hemorrhagic shock [19–22]. The assumption in these studies is that the mesenteric lymph is a vehicle for injurious factors produced or released in the intestine, which are mediators of severe injury to organs distal other than the intestine. However, analysis of the lymph, despite its importance for understanding the generation and early transport of cytotoxic mediators, has the disadvantage of a more limited translational potential, due to the difficulty of collecting gut lymph samples from shock patients. In contrast, further investigations, initially conducted using this mass spectrometry based approach with plasma (a very easily available and abundant source) and involving a suitable larger number of animals and conditions, may lead to the detection of potential biomarkers which could then be routinely quantified using widespread and much less demanding detection techniques, such as antibody-based methods.

A common finding in previous reports is that several proteins are upregulated in shock lymph, especially proteins with inflammatory and pro-coagulation properties. D’Alessandro and coworkers [22] reported that the upregulation of such proteins is accompanied by an impaired homeostasis of the balance between proteases and anti-proteases, especially serine proteases and MMPs, and that this could entail an activation of neutrophils following extracellular matrix metalloproteinase involvement. These observations are consistent with the evidence that digestive enzymes can promote “autodigestion” [2–5]. Hence, we took the next step in this investigation, the analysis of peptides in plasma, with the goal of looking for evidence of proteolytic processes in shock, which could prove impactful in future clinical studies.

Several categories of proteins were affected by the proteolysis detected in our study:

heat shock proteins related to mitochondrial function, which are known to be impaired in shock [23, 24];

serine protease inhibitors (Inter alpha-trypsin inhibitors, serine protease inhibitor A3N and A3K, plasma protease C1 inhibitor, alpha macroglobulins, etc.), indicating a possible response of the anti-proteases to the increased concentrations of circulating serine proteases in shock, and possibly suggesting that the increased protease activity produces extensive proteolysis because of a failure of the physiologic self-defense against proteases;

several cytoplasmic (e.g. aspartate aminotransferase) and membrane proteins (e.g. β2 microglobulin), suggesting that the degradation process also occurs inside cells or that cell contents leak into the bloodstream and become substrates for circulating proteases;

proteins involved in the coagulation cascade, typically involved in the response to hemorrhage, such as fibrinogen, coagulation factor XII, etc.;

proteins involved in the inflammatory response initiated by hemorrhage, and specifically in the innate immune response, such as C-reactive protein, complement proteins, macrophage migration inhibitory factors, thymosin β4, etc.

Many of the proteins from which the newly found fragments in shock are derived, besides being involved in a system-wide inflammatory and pro-coagulant response, are also typically associated with organ dysfunction, especially in the liver and the heart, and their presence in the plasma of HS patients, if verified, could serve as markers of organ failure and shock progression. The possible relationship between proteolysis and organ failure should be further investigated also on the basis of the result showing that the large majority of the cleaved proteins, from which the peptides increased in HS were generated, are cytoplasmic and membrane proteins. This could indicate cellular damage, which may play a role in organ dysfunction.

The enhanced activity of chymotrypsin-like proteases, estimated from the number of peptides generated by these enzymes with respect to the total number of peptides generated by proteolysis in shock, represents an important finding, which integrates previous data on protease activity in plasma and vital organs [2–5]. Low-throughput, semi-quantitative techniques such as gel or in situ zymography are unable to discriminate among serine proteases. This intrinsic limitation of these approaches was overcome by the quantitative nature of mass spectroscopy.

It is important to observe that, despite the fact that chymotrypsin-like enzymes appear to be responsible for much of the proteolytic generation of peptides in shock, all the proteolytic enzymes analyzed and reported in Table 5, including elastase-like and MMPs, generate a larger number of peptides in shock than in control animals. However, the overwhelming contribution of chymotrypsin-like enzymes (more than 50% of peptides generated in shock) leads to an apparently limited contribution (i.e., percentage value of peptide generation, Table 5) of other proteases.

An important implication of our findings is that they fit and validate previous reports on the possible effects of digestive enzymes which escape the intestinal lumen because of the damage that gut ischemia induces in the mucosal barrier [2–5] and cause damage in distal organs (“Autodigestion Hypothesis”). The proteolytic activity was not only reported to be increased in plasma, but also in distal organs, and the framework of the Autodigestion Hypothesis first provided a possible explanation for the role of digestive proteases in the organ damage which characterizes circulatory shock. In particular, it was reported that the proteolytic function of these enzymes affect transmembrane receptor integrity, e.g. shock was shown to reduce the density of the extracellular domain of the insulin receptor [25]. The results presented in this manuscript do not include the presence of fragments of the extracellular domain of transmembrane receptors such as the insulin receptor, possibly because of the relative low abundance in comparison to other more abundant plasma proteins. Still, the hypothesis that proteolytic activity takes place and coincides with increased activity of digestive enzymes, such as the chymotrypsin-like enzymes, was quantitatively validated by the findings obtained through the proposed peptidomic approach.

The choice of the experimental hemorrhagic shock model, and the related advantages and possible pitfalls of this model deserve to be discussed as well. This study used the Fixed-Pressure Hemorrhage (Wiggers) model, which is one of the standard models for experimental hypovolemic shock. The predicted mortality rate for this type of model exceeds 75% [4], and animals that do not survive consistently demonstrate multiorgan failure as measured by gross tissue examination, histology, and certain cellular and tissue markers (e.g., Troponin I, lung wet/dry ratios).

As detailed by Fülöp and colleagues [26], this model has the advantage of being highly standardized, controlled and reproducible, and as such is optimal for the study of the pathophysiology and proteomics/peptidomics of shock. In particular: i) the controlled procedure for blood withdrawal and return (executed at the same rate of 0.5 cc/min, as explained in the Materials and Methods) is completely reproducible; ii) the objective control of the hemodynamic state of the animal during hypovolemia is ensured by the maintenance of blood pressure around the target value of 35 mmHg; iii) the monitoring of conditions such as body temperature (decreased following bleeding, constant throughout the hypovolemic phase, and increased again to physiologic levels upon reperfusion) is conveniently repeatable. All these elements are consistently observed in our experience with this HS model [3–5, 25]. Of particular benefit for proteomics/peptidomics studies is this particular model minimizes trauma to the animals (e.g., a laparotomy was not done), mitigating the potential for confounders to the analysis of hemorrhage per se.

One of the main technical requirements of the Fixed-Pressure Hemorrhage model (and of every experiment where the animal is cannulated) is the use of anticoagulation to prevent the clotting of catheters and ensure the ability to withdraw, add, and store whole blood during the ischemic period. We used systemic heparinization both in the shock and control groups, which prevented any bias between the shock and the control groups. However, there could be a potential limitation of our results, in that heparin may have potentially interfered with proteolytic mechanisms, specifically the clotting cascade. Heparin increases (up to 600-fold [27, 28]) the inhibitory activity of antithrombin, a serpin (serine protease inhibitor) which binds, upon activation by heparin [27–30], to thrombin, trypsin and other coagulation factors. Further, proteases other than circulating serine proteases have been shown to be inhibited more effectively in the presence of heparin [30]. This may have led to an underestimate of the amount of proteolytic activity and subsequent peptide generation occurring in shocked animals compared to controls; thus our observations are most likely conservative in nature.

A second limitation of the experimental model is the necessity for storage of the drawn blood during hypovolemia. In order to maintain mean arterial pressure around the target level (i.e., ~ 35 mmHg in this experiment), it may be necessary to draw and/or reinfuse small aliquots of blood during the two-hour hypovolemic phase, and this requires that the shed blood is readily available at body temperature. Previous reports from our laboratory obtained both in hemorrhagic and non- hemorrhagic shock models, which do not entail ex vivo storage of blood for a pre-defined amount of time (e.g., splanchnic arterial occlusion shock or septic (peritonitis) shock or by endotoxin administration) have consistently shown that protease levels and activity are increased in shock independent of the model studied [4, 31–33]. Still, the possible effect of the storage of the shed (heparinized) blood at room temperature on excess proteolytic activity should be limited. Zimmerman and coworkers demonstrated that the temperature (including the range of room temperatures) and time of storage do not affect significantly blood proteins, which are broadly stable at the peptide level [34]. Additionally, heparin also has a protective effect on the stability of whole blood proteins at room temperatures, as reported by Henriksen et al. [35].

Conclusions and Perspectives

In summary, the main conclusions of this study are:

-

-

a quantitative confirmation that massive proteolysis occurs on the organism scale as a fundamental degrading phenomenon induced by shock;

-

-

serine proteases, whose plasma activity is increased in shock, are largely responsible for the observed proteolysis;

-

-

the experimental conditions of sample treatment and analysis suitable for the future identification of novel biomarkers of hemorrhagic shock in plasma has been set up.

One of the limitations of our study is the presentation of a “static” picture of the effect of shock at the end of the hypovolemia and reperfusion experiment. However, the possibility of collecting multiple blood samples in the rat is strongly limited by the sensitivity of the animal to blood withdrawal, especially during the hypovolemic phase, and a dynamic description of the phenomena reported in this manuscript during a similar hemorrhagic shock protocol requires the use of larger animals. Another possible limitation concerns the low number of animals included in the study. However, the use of technical replicates, which ensures robustness to the results obtained from each biological replicate, and the detection of a large increase in proteolytically produced peptides in all HS samples compared to CTRL, allows us to conclude that the present data fully support the direct experimental evidence of a general proteolytic activity in shock.

The role of the peptides, which are generated in shock, should be the subject of future analyses, given their potential role in shock. For example, vasoactive intestinal peptides, which are generated in the gut and promote cardiovascular responses (e.g., vasodilation and blood pressure reduction) are an example of peptides with patho-physiological relevance, to be further investigated, particularly in circulatory shock. If peptides present only in plasma from hemorrhagic shock animals, but not in control plasma, have possible vasoactive effects, they could become important pathogenic factors to study in the context of organ dysfunction induced by shock as well as new therapeutic targets.

The results presented in this manuscript serve as a starting point towards validation in large animals and clinical studies, in which an appropriate design should also include the assessment of the “dynamic” effects of shock on the peptidome and proteome (i.e., several blood samples over time from the same subject). Such studies should also propose the test of protease blockade as a cornerstone of an innovative therapeutic approach to protein degradation and peptide formation in circulatory shock.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the “ShockOmics” grant #602706 of the European Union, by the “CelSys Shock” Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship PIOF-GA-2012-328796 of the European Union in support of the first author, by the NIH grant GM 85072, and by the Career Development Award (CDA2) 1IK2BX001277-01A1 from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: FAD and GWSS own stock in Inflammagen Inc., a company that develops new shock treatments. Research supported by the “ShockOmics” grant #602706 of the European Union; by the “CelSys Shock” Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship PIOF-GA-2012-328796 of the European Union; by the NIH GM 85072; and by Career Development Award (CDA2) 1IK2BX001277-01A1 from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development.

Footnotes

AUTHORS

FA: contributed in the conception of the study and execution of the animal experiments and drafted the manuscript

EM: was involved in the proteomics analysis

AN: was involved in the proteomics analysis

MHS: contributed to the design of the study and to the animal experiments

FAD: contributed to the design of the study and to the animal experiments

EBK: contributed to the conception of the study as a whole, contributed to the manuscript

GWSS: contributed to the conception of the study as a whole, contributed to the manuscript

GT: contributed in the conception of the study, coordinated and executed the proteomics analysis, contributed to the manuscript

References

- 1.Vincent JL, De Backer D. Circulatory Shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1726–1734. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmid-Schönbein GW, Chang M. The autodigestion hypothesis for shock and multi-organ failure. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42(2):405–414. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0891-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altshuler AE, Penn AH, Yang JA, Kim GR, Schmid-Schönbein GW. Protease activity increases in plasma, peritoneal fluid, and vital organs after hemorrhagic shock in rats. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeLano FA, Hoyt DB, Schmid-Schönbein GW. Pancreatic digestive enzyme blockade in the intestine increases survival after experimental shock. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(169):169ra11. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altshuler AE, Richter MD, Modestino AE, Penn AH, Heller MJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW. Removal of luminal content protects the small intestine during hemorrhagic shock but is not sufficient to prevent lung injury. Physiol Rep. 2013;1(5):e00109. doi: 10.1002/phy2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langley RJ, Tsalik EL, van Velkinburgh JC, Glickman SW, Rice BJ, Wang C, Chen B, Carin L, Suarez A, Mohney RP, Freeman DH, Wang M, You J, Wulff J, Thompson JW, Moseley MA, Reisinger S, Edmonds BT, Grinnell B, Nelson DR, Dinwiddie DL, Miller NA, Saunders CJ, Soden SS, Rogers AJ, Gazourian L, Fredenburgh LE, Massaro AF, Baron RM, Choi AM, Corey GR, Ginsburg GS, Cairns CB, Otero RM, Fowler VG, Jr, Rivers EP, Woods CW, Kingsmore SF. An integrated clinico-metabolomic model improves prediction of death in sepsis. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(195):195ra95. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai X, Witzmann FA, Liangpunsakul S. Characterization of peptides and low molecular weight proteins in plasma from subjects with hepatocellular carcinoma. A Proteomics. 2014;1(1):6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chertov O, Biragyn A, Kwak LW, Simpson JT, Boronina T, Hoang VM, Prieto DA, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Fisher RJ. Organic solvent extraction of proteins and peptides from serum as an effective sample preparation for detection and identification of biomarkers by mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2004;4(4):1195–1203. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(12):1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luerman GC, Nguyen C, Samaroo H, Loos P, Xi H, Hurtado-Lorenzo A, Needle E, Stephen Noell G, Galatsis P, Dunlop J, Geoghegan KF, Hirst WD. Phosphoproteomic evaluation of pharmacological inhibition of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 reveals significant off-target effects of LRRK-2-IN-1. J Neurochem. 2014;128:161–176. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyrløv Bendtsen J, Juhl Jensen L, Blom N, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Feature based prediction of non-classical and leaderless protein secretion. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2004;17(4):349–356. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersen T, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Henrik Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nature Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Käll L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer ELL. A Combined Transmembrane Topology and Signal Peptide Prediction Method. J Mol Biol. 2004;338(5):1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer E. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305(3):567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turk Be, Huang LL, Piro ET, Cantley LC. Determination of protease cleavage site motifs using mixture-based oriented peptide libraries. Nature Biotecnology. 2001;19:661–667. doi: 10.1038/90273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thrailkill K, Cockrell G, Simpson P, Moreau C, Fowlkes J, Bunn RC. Physiological matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) concentrations: comparison of serum and plasma specimens. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44(4):503–504. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2006.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards AV, White MY, Cordwell SJ. The role of proteomics in clinical cardiovascular biomarker discovery. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7(10):1824–1837. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R800007-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen X, Young R, Canty JM, Qu J. Quantitative proteomics in cardiovascular research: global and targeted strategies. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2014;8(7–8):488–505. doi: 10.1002/prca.201400014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peltz ED, Moore EE, Zurawel AA, Jordan JR, Damle SS, Redzic JS, Masuno T, Eun J, Hansen KC, Banerjee A. Proteome and system ontology of hemorrhagic shock: exploring early constitutive changes in postshock mesenteric lymph. Surgery. 2009;146(2):347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang JF, Shih LY, Yuan KC, Fang KY, Hwang TL, Hsieh SY. Proteomic analysis of post-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph. Shock. 2010;34(3):291–298. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181ceef5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mittal A, Middleditch M, Ruggiero K, Loveday B, Delahunt B, Jüllig M, Cooper GJ, Windsor JA, Phillips AR. Changes in the mesenteric lymph proteome induced by hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2010;34(2):140–149. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181cd8631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Alessandro A, Dzieciatkowska M, Peltz ED, Moore EE, Jordan JR, Silliman CC, Banerjee A, Hansen KC. Dynamic changes in rat mesenteric lymph proteins following trauma using label-free mass spectrometry. Shock. 2014;42(6):509–517. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeger V, Djafarzadeh S, Jakob SM, Takala J. Mitochondrial function in sepsis. Eur J clin Invest. 2013;43(5):532–542. doi: 10.1111/eci.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villarroel JP, Guan Y, Werlin E, Selak MA, Becker LB, Sims CA. Hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation are associated with peripheral blood mononuclear cell mitochondrial dysfunction and immunosuppression. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(1):24–31. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182988b1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeLano FA, Schmid-Schönbein GW. Pancreatic digestive enzyme blockade in the small intestine prevents insulin resistance in hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2014;41(1):55–61. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fülöp A, Turóczi Z, Garbaisz D, Harsányi L, Szijártó A. Experimental models of hemorrhagic shock: a review. Eur Surg Res. 2013;50(2):57–70. doi: 10.1159/000348808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin L, Abrahams JP, Skinner R, Petitou M, Pike RN, Carrell RW. The anticoagulant activation of antithrombin by heparin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(26):14683–14688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang L, Manithody C, Rezaie AR. Heparin-activated antithrombin interacts with the autolysis loop of target coagulation proteases. Blood. 2004;104(6):1753–1759. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whisstock JC, Pike RN, Jin L, Skinner R, Pei XY, Carrell RW, Lesk AM. Conformational changes in serpins: II. The mechanism of activation of antithrombin by heparin. J Mol Biol. 2000;301(5):1287–1305. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins WJ, Fox DM, Kowalski PS, Nielsen JE, Worrall DM. Heparin enhances serpin inhibition of the cysteine protease cathepsin L. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(6):3722–3729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.037358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altshuler AE, Lamadrid I, Li D, Ma SR, Kurre L, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Penn AH. Transmural intestinal wall permeability in severe ischemia after enteral protease inhibition. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang M, Alsaigh T, Kistler EB, Schmid-Schönbein GW. Breakdown of mucin as barrier to digestive enzymes in the ischemic rat small intestine. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e40087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penn AH, Schmid-Schönbein GW. Severe intestinal ischemia can trigger cardiovascular collapse and sudden death via a parasympathetic mechanism. Shock. 2011;36(3):251–262. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182236f0f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimmerman LJ, Li M, Yarbrough WG, Slebos RJ, Liebler DC. Global stability of plasma proteomes for mass spectrometry-based analyses. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(6):M111.014340. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.014340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henriksen LO, Faber NR, Moller MF, Nexo E, Hansen AB. Stability of 35 biochemical and immunological routine tests after 10 hours storage and transport of human whole blood at 21°C. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2014;74(7):603–610. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2014.928940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]