Abstract

Introduction

To examine the contribution of trauma exposure to cannabis initiation and transition to first cannabis use disorder (CUD) symptom in African-American (AA) and European-American (EA) emerging adults.

Methods

Data are from the Missouri Adolescent Female Twins Study [(N = 3787); 14.6% AA; mean age = 21.7 (SD 3.8)]. Trauma exposures (e.g. sexual abuse, physical abuse, witnessing another person being killed or injured, experiencing an accident, and experiencing a disaster) were modeled as time-varying predictors of cannabis initiation and transition to CUD symptom using Cox proportional hazards regression. Other substance involvement and psychiatric disorders were considered as time-varying covariates.

Results

Analyses revealed different trauma-related and psychiatric predictors for cannabis use supporting racially distinct etiologic models of cannabis involvement. For AA women, history of witnessing injury/death or experiencing a life-threatening accident was associated with cannabis initiation across the complete emerging adult risk period while sexual abuse predicted cannabis initiation only before 15 years old. For EA women, history of sexual or physical abuse and major depressive disorder (MDD) predicted cannabis initiation and physical abuse and MDD predicted transition from initiation to first CUD symptom. No association was discovered between trauma exposures and transition to first CUD symptom in AA women.

Conclusions

Results reveal trauma exposures as important contributors to cannabis initiation and to a lesser extent transition to CUD symptom, with different trauma types conferring risk for cannabis involvement in AA and EA women. Findings suggest the importance of considering racial/ethnic differences when developing etiologic models of cannabis involvement.

Keywords: Cannabis, Marijuana, Traumatic stress, Racial differences

1. Introduction

Cannabis is currently the most used illicit drug and most prevalent illicit substance use disorder (Hall, 2009; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA), 2014). Over half of emerging adults (18–25 year old) report using cannabis in their lifetime (SAMSHA, 2014) and the past-year prevalence of both cannabis use (Grucza et al., 2016; Hasin et al., 2015) and cannabis dependence has increased in the past decade (Hasin et al., 2015). Even more staggering, over a 10-year period, steep increases have been recorded in the prevalence of cannabis use among women (from 2.6% to 6.9%; Hasin et al., 2015). Significant gender differences in substance related etiology, epidemiology, and co-occurring psychopathology are evident (Tuchman, 2010) while research focused on cannabis pathology in women is sparse (Fattore et al., 2008; Hayaki et al., 2010). Racial factors are also important to consider as increases in both cannabis use and cannabis use disorder (CUD) in African-Americans have been reported, with cannabis use increasing from 4.7% to 12.7% and CUD from 1.8% to 4.6% between 2001 and 2013 (Hasin et al., 2015). Furthermore, CUD and cannabis use–particularly early initiation of cannabis use–is linked to a host of deleterious outcomes including psychiatric symptoms (i.e., anxiety and depression) and use of other drugs (Compton et al., 2011; Davis et al., 2013; Hall, 2009; Patton et al., 2002; Volkow et al., 2014). Taken together, these data point to the importance of considering cannabis initiation and CUD as a public health concern and provide a compelling rationale for developing gender- and race-specific etiological models of cannabis involvement.

1.1. Cannabis involvement and the contribution of trauma exposure

Trauma exposure is a well-established risk factor for substance use and related problems in adolescents (Duncan et al., 2008; Kendler et al., 2000; Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Molnar et al., 2001; Nelson et al., 2002; Sartor et al., 2013b; Sullivan et al., 2004;Walsh et al., 2014; Zinzow et al., 2009). Childhood assaultive trauma such as sexual abuse and physical abuse have been the most investigated (Caetano et al., 2003; Sartor et al., 2015), but non-assaultive trauma (i.e., witnessing violence, accidents and natural disasters) have also been found to increase substance-related behaviors, although the data are less consistent (Cerda et al., 2011;Hasin et al., 2007; Keyes et al., 2011; North et al., 2004). Most epidemiologic research has focused primarily on the association between trauma and alcohol related outcomes with studies specifically investigating the relationship of trauma exposure and cannabis outcomes has been scarce (Cougle et al., 2011; Kevorkian et al., 2015; Sartor et al., 2015). Studies which have focused on cannabis outcomes have revealed that exposure to a traumatic event alone and PTSD have both been associated with cannabis outcomes. Cougle et al. (2011) found a significant association between lifetime PTSD and cannabis use when adjusting for co-occurring psychopathology and trauma frequency. Trauma was also associated with cannabis use but specific type of trauma was not considered. Additionally, a recent investigation revealed a graduated relationship between trauma exposure and cannabis phenotypes: overall lifetime trauma exposure was significantly associated with cannabis use but not CUD, while PTSD was associated with CUD but not cannabis use (Kevorkian et al., 2015). However, the extant epidemiologic literature linking cannabis and trauma-related factors has relied on cross-sectional analyses (Cougle et al., 2011; Kevorkian et al., 2015)—limiting the ability to differentiate antecedent from consequent events. Some literature suggests that substance use can increase the likelihood of later trauma exposure and that the relationship is bi-directional (Thompson et al., 2008), emphasizing the need to examine the relationship while considering temporality to better establish causation. Additionally, although the literature supports a clear relationship between trauma pathology and cannabis use, the existing literature often relies on the co-occurrence of PTSD and CUD, neglecting to consider the unique impact of trauma exposure independent of PTSD diagnosis, the contribution of different trauma exposures, and different levels of cannabis involvement as outcomes.

1.2. Role of race/ethnicity

Racial differences between African-American (AA) and European-American (EA) women in patterns of cannabis and other substance use are also important to consider. Racial disparities in trauma exposure and prevalence of cannabis use (Compton et al., 2004; Finlay et al., 2012) have been identified. African-American women are disproportionately exposed to traumatic stress and report higher rates of psychopathology (i.e., posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression (MDD) (Duncan et al., 2014; McCutcheon et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2011)). Research has shown differential patterns of cannabis use exist between African-American and European-American samples: AAs are more likely to use cannabis first (as opposed to alcohol (Sartor et al., 2013a)) and to use cannabis into adulthood (Finlay et al., 2012). Furthermore, rates of cannabis use disorder are increasing more quickly in AAs (Compton et al., 2004; Hasin et al., 2015). Unfortunately, AA women have been underrepresented in substance-related studies, which limit the examination of racial differences in the influence of environmental factors on multiple cannabis related phenotypes. Research has also shown differences in the impact of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) on cannabis involvement between AA and EA women (Sartor et al., 2015). A recent investigation linked CSA to cannabis initiation and transition to first problem (after taking into account familial risk; Sartor et al., 2015). European-Americans with a history of CSA were at consistently higher risk for cannabis use and transition to problem use. Within AA respondents, the association between CSA and cannabis outcomes varied by developmental period. Childhood sexual abuse increased risk for cannabis use at highest magnitude at ages ≤14 and increased risk for cannabis problem at highest magnitude at ages ≥21. Thus, existing environmental etiological models of cannabis involvement do not appear to fit as well for AA as EAs. Understanding how race can impact cannabis initiation and problem development and how trauma exposure plays a role in initiation and transition to problems is essential for developing culturally sensitive, competent, and effective prevention and intervention strategies.

1.3. Current study

The current report investigates racial differences in the development of cannabis use and problem use in EA and AA women. The aims of the current study are to a) characterize racial differences in cannabis involvement and cannabis risk factors; b) examine racial differences in the risk conferred by specific trauma exposure for cannabis use and time to first cannabis use disorder (CUD) symptom while also considering the contribution of other substance involvement and psychopathological risk factors.

2. Methods

Detailed descriptions of the Missouri Adolescent Female Twin Study (MOAFTS) methods have been previously reported (Heath et al., 2002; Waldron et al., 2013), with summaries pertaining to the current investigation provided. Procedures for MOAFTS were approved by the Human Research Protections Office at Washington University.

2.1. Participants

Missouri Adolescent Female Twin Study is a longitudinal investigation of alcohol-related problems and associated psychopathology in female adolescence and young adults. Twins born to Missouri-resident parents between July 1, 1975 and June 30, 1985 were identified through birth records and recruited from 1995 to 1999. Cohorts of 13, 15, 17, and 19 year-old twin pairs and their families were ascertained. Parental diagnostic interviews were collected at baseline in 78% of the families recruited and found eligible for participation. Baseline (Wave 1) interviews were completed with 3258 twins. Wave 3 retest interviews were conducted with a subset of Wave 1 participants (n = 1370) two years after Wave 1 assessments. (Data were not drawn from Wave 2 interviews, as they did not cover all domains of interest.) Wave 4 assessments were conducted from 2002 to 2005 with 3787 participants (80% of twins identified from birth records) and contained detailed trauma history assessment. Data from Waves 1 and/or 3 were available for 95.5% of Wave 4 participants which included 2176 monozygotic (57.5%) and 1611 di-zygotic (42.5%) female twins. Ages of the female participants at the time of Wave 4 interview ranged from 18 to 29 years (M = 21.7; SD = 2.76); 14.6% percent of participants identified as African-American (AA) and 85.4% as European-American (EA).

2.2. Procedure and assessment battery

Data were collected by trained interviewers using an interview modified for telephone administration from the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA; Bucholz et al., 1994). The SSAGA was designed to assess the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) substance use and other psychiatric disorders and related psychosocial domains. Consent was obtained verbally prior to the start of the interview. All available data from waves 1, 3 and 4 were utilized and collapsed across waves for purpose of analysis. The first reported age of onset given for trauma exposures, cannabis involvement, and other individual level covariates was utilized in analyses.

2.2.1. Cannabis related behaviors

Cannabis initiation was defined as the first time the participant ever used cannabis with age of onset recorded as the earliest age this first occurred. For those who endorsed ever using cannabis at more than one assessment, Cronbach alpha for age of first cannabis initiation was 0.90, indicating high test-retest reliability across waves 1, 3, and 4. As there is no standard definition of early cannabis initiation, we chose the lowest third of the age at initiation distribution (age 15 or younger) to represent early use relative to same sex peers. First CUD symptom was coded positive for individuals who endorsed one or more symptom of cannabis abuse or dependence with age at first CUD symptom derived from reported age(s) that each endorsed symptom was first experienced.

2.2.2. Trauma exposure

Trauma exposure history was assessed using a checklist of traumatic events adapted from the Revised Diagnostic Interview Schedule (Robins et al., 1985) used in the National Comorbidity Survey (Kessler et al., 1995). Respondent booklets were mailed prior to the interview and included a list of traumatic events. Participants were asked whether they had experienced each of the traumatic events listed in the respondent booklet and were instructed not to report the same event twice. Age at first experience of each endorsed event was queried. Traumatic experiences included childhood sexual abuse (CSA), childhood physical abuse (CPA), witnessing injury or death, life threatening accident, and natural disaster. Additional questions using behavioral descriptions of experiences consistent with childhood sexual or physical abuse were asked by the interviewer using the questions from the SSAGA with endorsement of one or more questions coded as a positive for CSA or CPA respectively (see Table 1). Ages of onset were defined as age of first reported experience for each event.

Table 1.

Items Used to Define Childhood Physical and Sexual Abuse in MOAFTS.

| Childhood Sexual Abuse |

Parental Discipline and Early Childhood Experiences

|

| Health Problems and Health Habits |

| Has anyone ever forced you to have sexual intercourse? |

Traumatic Events

|

| Childhood Physical Abuse |

Parental Discipline and Early Childhood Experiences

|

Traumatic Events

|

| MOAFTS=Missouri Adolescent Female Twin Study |

2.2.3. Covariates

As co-occurring substance use (Guxens et al., 2007) and psychopathology (Kedzior and Laeber, 2014) have been associated with cannabis involvement, alcohol use, tobacco use, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) were considered as covariates in the current investigation. Tobacco initiation (age of onset) was defined as the age at which the participant first ever used/tried tobacco. Alcohol initiation (age of onset) was defined as the age at which the participant first consumed a full alcoholic beverage. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder diagnosis reflects DSM-IV criteria and was assessed querying the traumatic event reported as most disturbing which also resulted in feelings of “intense fear, helplessness, or horror.” Individuals who reported no trauma or disturbing feelings were coded as negative for PTSD. Age at onset of PTSD was defined as age at first symptom that lasted at least 1 month. Major Depressive Disorder criteria was met if dysphoria or anhedonia were reported as occurring for more than 2 weeks along with DSM-IV criteria for 5 or more major depressive symptoms during the same 2-week period with age of onset defined as age when first met full criteria. Parental characteristics: To account for the impact of socio-economic status, parental education was included in models as a proxy. Individual variables representing mother’s and father’s education levels were created by dummy-coding parental reports on whether each parent had completed high school (with more than high school as the reference variable). As maternal smoking has been strongly associated with young adult cannabis involvement (Hayatbakhsh et al., 2009), history of maternal nicotine dependence was considered and coded from maternal-report of nicotine dependence assessed in the parent interview in accordance with DSM-IV criteria.

2.3. Data analysis

2.3.1. Cannabis involvement, psychopathology, and trauma exposure by race

Chi-square tests of association were conducted to test for differences in rates of use and endorsement of CUD symptoms (one or more) by race/ethnicity within the AA and EA subsamples. Independent t-tests were conducted to test for differences in age at first use, age at onset of first CUD symptom, rate of transition from first use to first symptom by race/ethnicity. Chi-square tests of association to test for differences in rates of PTSD, MDD, and trauma exposure by race were also conducted. All analyses were conducted taking familial clustering into account using the cluster command as implemented in Stata (StataCorp, 2007).

2.3.2. Predicting initiation of cannabis use and onset of CUD symptoms with trauma exposure

Cox proportional hazards (pH) regression analyses were conducted to predict initiation of cannabis use and transition from cannabis initiation to onset of CUD symptoms. Age at first cannabis use was the entry point in the CUD symptom onset analyses. Cox pH regression analyses account for the possibility that participants who have not yet experienced the event of interest (e.g. initiation of cannabis use) may do so in the future. Under this approach, data up until the time of censoring (most recent interview) is used in the calculation of hazard ratios. The pH assumption that risk remains constant over time was tested with the Grambsch and Therneau test of the Schoenfeld residuals (Grambsch and Therneau, 1994), violations of the assumption were corrected with age specific interactions, which can reveal the extent to which risk associated with trauma varies across the period of risk (e.g., whether trauma exposure is a predictor at certain ages). Trauma exposures, PTSD, MDD, tobacco and alcohol involvement were modeled as time-varying covariates coded as negative in each year prior to the age at first occurrence and positive for that year and each subsequent year, so that only covariates preceding the outcomes were considered informative. Analyses were conducted in Stata (StataCorp, 2007) using Huber-White robust standard errors to adjust for the non-independence of observations in twins. Violations of the pH assumption were resolved by estimating piecewise hazard ratios (HRs) for each age ranges of ≤14, 15–18, and ≥19. All analyses were adjusted for age at most recent interview, maternal nicotine dependence, and parental educational attainment. Additionally, the CUD symptom onset analyses included early cannabis use status as a covariate.

As a primary goal of this study was to investigate racial differences in cannabis involvement, Cox regression analyses testing the interaction of race and trauma type were conducted. As race was revealed as a significant predictor of both cannabis initiation and transition to a CUD symptom and significant interactions were found for race with sexual abuse, physical abuse, and experiencing an accident, further analyses were stratified by race to investigate the unique trauma-related etiologic models for cannabis involvement in EA and AA subsamples.

3. Results

3.1. Cannabis involvement, psychopathology, and trauma exposure by race

No differences were discovered between AA and EA women in cannabis use, first age of initiation, age at first CUD symptom, or transition time from first use to first CUD symptom(Table 2). However, of those who had used cannabis, AA women were significantly more likely to experience a CUD problem (X2 = 7.95, p = .009) than their EA counterparts. AAs were also more likely to be diagnosed with PTSD [total sample: (X2 = 16.25, p < .001); trauma-exposed: (X2 = 4.86, p = .04)] and MDD (X2 = 9.13, p = .004). AAs reported a higher prevalence of sexual abuse (X2 = 17.15, p < .001), physical abuse (X2 = 162.70, p <.001), witnessing injury or death (X2 = 45.54, p < .001), and experiencing a life threatening accident (X2 = 20.88, p < .001) than EA women. No differences were found in prevalence of experiencing a natural disaster between EA and AA women.

Table 2.

Cannabis Involvement, Psychopathology, and Trauma Characteristics by Race.

| Total | EA | AA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis Related Behaviors | |||

| Ever used Cannabis | 44.9% | 44.1% | 49.6% |

| Age at Cannabis Initiation (years)a | 16.6 (2.3) | 16.5 (2.3) | 16.9 (2.5) |

| ≥1CUD symptoma | 19.7% | 18.5% | 25.9%** |

| Age at Cannabis Initiation (years)b | 15.5 (2.2) | 15.3 (2.2) | 16.0 (2.0) |

| Age at 1st CUD symptom (years)b | 17.3 (2.6) | 17.2 (2.6) | 17.9 (2.6) |

| Psychiatric Disorders | |||

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 4.1% | 3.6% | 7.2%** |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (trauma exposed) | 7.5% | 6.9% | 10.1%* |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 14.3% | 13.6% | 18.4%** |

| Trauma exposure | |||

| Sexual Abuse | 15.8% | 14.8% | 21.7%** |

| Sexual Abuse Age of Onset (years) | 8.6 (4.0) | 8.7 (4.0) | 8.5 (3.8) |

| Physical Abuse | 25.4% | 21.7% | 47.2%*** |

| Physical Abuse Age of Onset (years) | 9.1 (2.3) | 9.1 (2.4) | 9.3 (2.0)** |

| Witnessed another being killed or injured | 16.7% | 15.0% | 26.6%*** |

| Witnessing Age of Onset (years) | 15.4 (4.6) | 15.7 (4.4) | 14.3 (4.9)** |

| Involved in a Disaster | 17.5% | 17.7% | 16.6% |

| Disaster Age of Onset (years) | 11.6 (5.6) | 11.4 (5.6) | 12.7 (5.7) |

| Experienced a life threatening accident | 15.4% | 14.3% | 21.9%*** |

| Accident Age of Onset (years) | 15.1 (5.1) | 14.9 (5.1) | 15.9 (5.1) |

Conditional only includes those who ever used cannabis.

Conditional only includes those who endorsed at least 1CUD symptom.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.0001.

3.2. Cox regression for cannabis initiation and onset of first CUD symptom

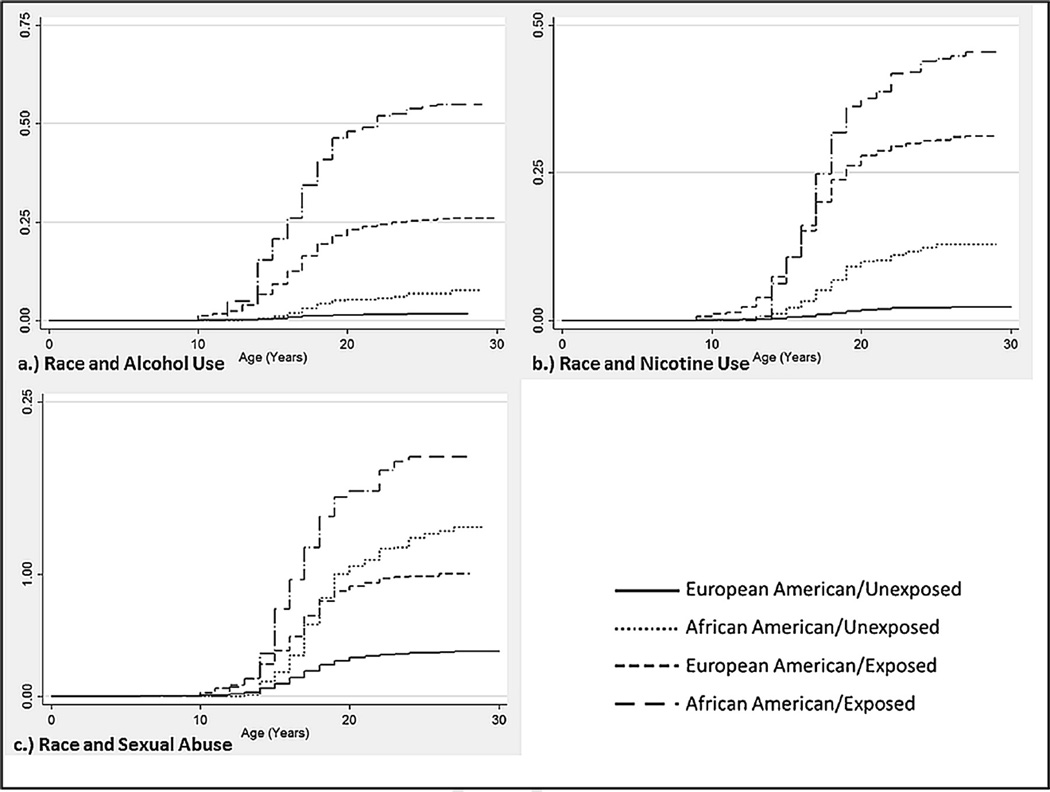

Sexual abuse increased the hazard of cannabis initiation for EA women across all risk periods [HR = 1.19, 95%CI: (1.03–1.38)] and AA women prior to the age of 15 [HR = 2.20, 95%CI: (1.11–4.39)]. Witnessing another person being killed or injured [HR = 1.36, 95%CI: (1.02–1.81)] and experiencing an accident [HR = 1.68, 95%CI: (1.27–2.22)] were associated with increased initiation of cannabis among AA women only. In EA women only, physical abuse [HR = 1.21, 95%CI: (1.07–1.37)] and MDD [HR = 1.43, 95%CI: (1.19–1.71)] also increased the risk for cannabis initiation. For AA women, the increased hazard conferred by alcohol use [HR = 2.79, 95%CI: (2.07–3.75)] and tobacco use [HR = 2.69, 95%CI: (2.04–3.54)] for cannabis initiation was consistent across all risk periods. The largest magnitude risk for cannabis initiation was conferred by alcohol use [HR = 4.74, 95%CI: (3.77–5.96)] and tobacco use [HR = 6.69, 95%CI: (5.18–8.64)] during adolescent years (ages 15–18) in EA women(Table 3 and Fig. 1). Posttraumatic stress disorder did not significantly increase the hazard for cannabis initiation in EA or AA women.

Table 3.

Results of Cox proportional hazards regression analysis predicting cannabis initiation

| African American | European American | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Alcohol Use | (≤ 14) (15–18) (≥ 19) |

┬ 2.79 (2.07–3.75)*** ┴ |

0.91 (0.63–1.31) 4.74 (3.77–5.96)*** 0.56 (0.22–1.47) |

| Tobacco Use | (≤ 14) (15–18) (≥ 19) |

┬ 2.69 (2.04–3.54)*** ┴ |

2.01 (1.17–3.46)* 6.69 (5.18–8.64)*** 0.54 (0.29–0.98)* |

| MDD | 1.09 (0.73–1.65) | 1.43 (1.19–1.71)*** | |

| PTSD | 1.31 (0.78–2.21) | 1.12 (0.85–1.47) | |

| Sexual Abuse | (≤ 14) (≥ 15) |

2.20 (1.11–4.39)* 0.80 (0.55–1.17) |

┬ 1.19 (1.03–1.38)* ┴ |

| Physical Abuse | 0.88 (0.70–1.11) | 1.21 (1.07–1.37)** | |

| Witness | 1.36 (1.02–1.81)* | 1.16 (0.98–1.39)† | |

| Accident | 1.68 (1.27–2.22)*** | 1.09 (0.92–1.29) | |

| Disaster | 1.22 (0.84–1.76) | 1.05 (0.90–1.22) | |

Note: Models adjusted for age, mother s and father s education and mother s lifetime history of nicotine dependence;

p <0.1 (trend),

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.0001

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier failure estimates: probability of cannabis initiation as a function of race and a) alcohol use, b) nicotine use, and c) sexual abuse adjusting for all covariates included in the cox proportional hazard regression.

When considering transition from first use to first CUD symptom, survival analysis revealed significant predictors in EA women only. Physical abuse predicted transition across the risk period [HR = 1.34, 95%CI: (1.02–1.78)] and MDD increased the hazard of transition to first CUD symptom prior to age 19 [HR = 1.86, 95%CI: (1.24–2.79)] (Table 4). No trauma exposure, psychiatric disorder, or substance use conferred risk for transition to first CUD symptom in AA women, although, PTSD diagnosis did reach trend level for transition to first CUD symptom in both EA and AA women.

Table 4.

Results of Cox proportional hazards regression analysis predicting rate of transition from cannabis initiation to first CUD symptom

| African American | European American | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Alcohol Use | 1.45 (0.71–2.96) | 1.38 (0.86–2.23) | |

| Tobacco Use | 1.22 (0.65–2.27) | 0.73 (0.39–1.39) | |

| Early Cannabis Use | 1.05 (0.56–1.95) | 1.31 (0.97–1.77) | |

| MDD | (≤ 18) (≥ 19) |

┬ 1.38 (0.78–2.44) ┴ |

1.86 (1.24–2.78)** 0.73 (0.31–1.74) |

| PTSD | 1.78 (0.93–3.42)† | 1.54 (0.93–2.53)† | |

| Sexual Abuse | 0.73 (0.38–1.40) | 0.96 (0.69–1.34) | |

| Physical Abuse | 1.39 (0.85–2.27) | 1.35 (1.02–1.78)* | |

| Witness | 0.98 (0.58–1.66) | 1.17 (0.83–1.65) | |

| Accident | 0.59 (0.32–1.10) | 1.01 (0.70–1.46) | |

| Disaster | 0.91 (0.48–1.73) | 1.15 (0.83–1.59) | |

Note: Transition from first cannabis use to first cannabis problem; Models adjusted for age, mother s and father s education and mother s lifetime history of nicotine dependence;

p <0.1 (trend),

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.0001

4. Discussion

We investigated cannabis involvement and the contribution of trauma exposure to cannabis initiation and transition to cannabis problems in EA and AA women. The likelihood of developing CUD symptoms was higher in AA than EA women who had tried cannabis, but no differences between rates of cannabis initiation or ages of onset for cannabis initiation, time of first CUD symptom, transition time from cannabis initiation to first cannabis problem were discovered. AA women did report elevated rates of PTSD, MDD, and trauma exposure (with the exception of experiencing a disaster) as compared to their EA counterparts.

Consistent with the limited extant literature linking cannabis involvement and trauma exposure, for both AA and EA women, we found trauma exposure increased the hazard for cannabis initiation − although the trauma type conferring the risk was not consistent across races. With the exception of physical abuse in EA women, the increase in hazard associated with each trauma exposure did not persist when transitioning to first CUD symptom. These findings build on previous research (Cougle et al., 2011; Kevorkian et al., 2015; Sartor et al., 2015) by examining the effects of trauma exposure types and considering the transition to first CUD problem from cannabis initiation as opposed to starting our analyses at birth. By doing so, we were able to parse out the effects of trauma exposures on cannabis use from those on conditional progression to first CUD symptom. The current findings suggest, in general, trauma exposure may most strongly impact initiation of cannabis use with diminished associations at more pathological levels of use. Our findings further previous reports by Kevorkian and colleagues (2015) who suggested a graduated relationship between trauma and cannabis involvement. They found any life-time trauma exposure to be significantly associated with cannabis use and PTSD to be associated with CUD with only a marginal relationship between trauma exposure and the more severe cannabis pathology. Although not significant in our analyses, a trend to association between PTSD and transition to a CUD symptom was revealed in both EA and AA women, which is suggestive of a potentially significant relationship. Our findings are consistent with the supposition that cannabis use is initiated following the trauma as a possible means of self-medication to relieve the general distress surrounding a traumatic event (Bonn-Miller et al., 2010, 2007).

Interestingly, racial differences in the type of trauma, psychopathology, and developmental period of risk associated with cannabis initiation and transition to first CUD problem were discovered. Although sexual abuse was determined to increase risk for cannabis initiation in both AA and EA women, the risk conferred for cannabis initiation in AA women was significant only prior to 15 years of age. This difference may be partially explained by reports that AAs are more likely to initiate cannabis first while EAs often use alcohol as their first substance (Sartor et al., 2013a). That is, AAs that experience childhood sexual abuse may be more likely to initiate cannabis while EAs may be more prone to use alcohol or other substances. Additionally, cannabis use may be more normative and easily accessible in some populations, increasing the likelihood of use at an early age. Witnessing another person being killed or injured and experiencing a life threatening accident were associated with cannabis initiation in AA women only. Physical abuse and MDD were discovered as risk factors for both cannabis initiation and transition to cannabis-related problems but only in the EA women, suggesting distinct risk factors for EA women illuminating a possible point of intervention for these individuals. A possible explanation for differences in hazard associated physical abuse may be due to differences in acculturation of physical punishment. Previous research supports variations in cultural norms pertaining to the use of physical discipline (Deater-Deckard et al., 2003) and AA parents have been reported to be more likely to use harsh physical discipline as compared to EA parents (Zolotor et al., 2008). Furthermore, in a partially overlapping study, AAs were found to be more likely than EAs to endorse behavioral questions querying physical abuse not directly labeling the experience as traumatic (Unpublished results). Therefore the experience, although termed physical abuse, may not have been interpreted as such by the participant. Therefore increased risk of cannabis involvement might not be expected. Overall, these differences in trauma associated risk are difficult to interpret as we would have expected larger hazards associated trauma for EAs compared AAs given the overall higher rates of trauma exposure in the AA sample. A possible explanation for racial differences could be linked to differential levels of support following trauma exposure. African Americans are less likely to seek treatment following a trauma exposure (Roberts et al., 2011). As such, they may experience prolonged distress associated with the trauma as compared to those who do receive treatment and subsequently use cannabis to alleviate the distress. As the main focus on MOAFTS was substance related, treatment seeking following a trauma exposure was not assessed, but would be a valuable factor to consider in future investigations.

Additionally, the degree of stability in the relationship between alcohol and tobacco use and cannabis initiation differed in EA vs. AA women. In AA women, alcohol and tobacco use conferred a consistent, significant risk for cannabis initiation across the period of risk, whereas the association between alcohol and tobacco use and cannabis initiation in EA women was unstable. For alcohol, before the age of 15 and after the age of 18 no significant association was revealed for cannabis initiation; however a substantial risk was associated with alcohol use for cannabis initiation between 15 and 18 years old in the EA women. A similar pattern emerged for tobacco use with the highest hazard for cannabis initiation during adolescent years for EA women but a consistent increase in risk in AA women. These findings indicate the risk conferred by use of alcohol and tobacco are specific to early initiation in EAs but in AAs–who initiate alcohol and tobacco later and in which use is slightly less normative–use at any age may contribute to pathological outcomes. This is consistent with previous findings in a partially overlapping sample which reported AA women are more likely to use cannabis before alcohol or tobacco and first use substances at a later age and for longer than EA women (Sartor et al., 2013a).

4.1. Limitations and future directions

As the aim of the current investigation was to characterize the impact of trauma exposure on cannabis involvement, the current study did not investigate if cannabis involvement increased the risk of experiencing a trauma. That is, cannabis use may increase the risk for additional trauma exposure by increasing the likelihood of high-risk behaviors (Baskin-Sommers and Sommers, 2006). Secondly, the current study coded each trauma type as positive at the first age of onset not taking into account later additional exposures to the same trauma. Future research would benefit from a more fine-tuned consideration of trauma exposure assessment that assessed events occurring throughout the lifespan. Future research should query cannabis involvement and trauma exposure longitudinally, beginning in childhood, to allow for the examination of the impact trauma-related factors have on the trajectory of cannabis use and cannabis related pathology. Additional methodological limitations include the potential for recall bias of ages of onset for both substance and trauma related measures as well use of a Midwestern cohort that might not be generalizable to national and global populations. The current findings suggest etiological models of cannabis involvement for AA and EA women must be considered discretely as risk and protective factors may differ across race. However, future research would benefit from including a larger sample of AA women, as the current investigation was limited by AA sample size. Including a larger AA cohort would allow for the development of well powered, racially distinct etiological models of cannabis involvement. Lastly, the current findings cannot be generalized to men as men differ from women with respect to their experiences of trauma, reactions to trauma (Breslau, 2002; Tolin and Foa, 2006) and level of involvement in cannabis (Agrawal and Lynskey, 2007).

4.2. Conclusion

The current investigation extends previous research by identifying unique trauma-related and psychiatric risk factors of cannabis involvement for AA and EA women. Our results highlight trauma exposure as a risk factor for cannabis initiation with tempered findings in more pathological cannabis involvement. Considering the impact of trauma exposure types, in addition to PTSD, on cannabis and other substance involvement is important to fully develop etiological models. The inclusion of a larger number of AAs and more specific trauma-related measures in a longitudinal design that can examine bi-directional influences of trauma exposure and cannabis involvement will provide further insight into the relationship between trauma exposure and cannabis use involvement.

Acknowledgments

None.

Contributors

This work was primarily supported by National Institute of Health grants awarded to authors Bucholz (AA011998, AA012640), Heath (AA017688), McCutcheon (AA018146), Sartor (AA017921, AA023549). The work of author Werner was supported by NIDA grand T32-DA15035 and included preparation of the initial draft of the manuscript. Authors Heath and Bucholz provided the data and contributed to the conceptualization and preparation of the manuscript. Authors Sartor and McCutcheon assisted in analysis and preparation of the research. Authors Agrawal and Nelson provided theoretical insight and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. All authors contributed to preparation and have approved of the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Does gender contribute to heterogeneity in criteria for cannabis abuse and dependence? Results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV. Am. Psychiatr. Assoc. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Baskin-Sommers A, Sommers I. The co-occurrence of substance use and high-risk behaviors. J. Adolesc. Health. 2006;38:609–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Feldner MT, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ. Posttraumatic stress symptom severity predicts marijuana use coping motives among traumatic event-exposed marijuana users. J. Trauma. Stress. 2007;20:577–586. doi: 10.1002/jts.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Babson KA, Vujanovic AA, Feldner MT. Sleep problems and PTSD symptoms interact to predict marijuana use coping motives: a preliminary investigation. J. Dual Diagn. 2010;62:111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N. Gender differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Gend. Specif. Med. 2002;5:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Reich T, Schmidt I, Schuckit MA. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: a report on the reliability of the SSAGA. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 1994;552:149. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Field CA, Nelson S. Association between childhood physical abuse, exposure to parental violence, and alcohol problems in adulthood. J. Interpers. Violence. 2003;18:240–257. [Google Scholar]

- Cerda M, Tracy M, Galea S. A prospective population based study of changes in alcohol use and binge drinking after a mass traumatic event. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;115:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD, Stinson FS. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT, Simmons CM, Weiss PS, West JC. Axis IV psychosocial problems among patients with psychotic or mood disorders with a cannabis use disorder comorbidity. Am. J. Addict. 2011;20:563–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ, Hawkins KA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cannabis use in a nationally representative sample. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2011;25:554–558. doi: 10.1037/a0023076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GP, Compton MT, Wang S, Levin FR, Blanco C. Association between cannabis use psychosis, and schizotypal personality disorder: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Schizophr. Res. 2013;151:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Pettit GS, Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Bates JE. The Development of attitudes about physical punishment: an 8-Year Longitudinal Study. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003;17:351–360. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AE, Sartor CE, Scherrer JF, Grant JD, Heath AC, Nelson EC, Jacob T, Bucholz KK. The association between cannabis abuse and dependence and childhood physical and sexual abuse: evidence from an offspring of twins design. Addiction. 2008;103:990–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AE, Munn-Chernoff MA, Hudson DL, Eschenbacher MA, Agrawal A, Grant JD, Nelson EC, Waldron M, Glowinski AL, Sartor CE, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Heath AC. Genetic and environmental risk for major depression in African-American and European-American women. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2014;17:244–253. doi: 10.1017/thg.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore L, Altea S, Fratta W. Sex differences in drug addiction: a review of animal and human studies. Womens Health Lond. Engl. 2008;4:51–65. doi: 10.2217/17455057.4.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AK, White HR, Mun E-Y, Cronley CC, Lee C. Racial differences in trajectories of heavy drinking and regular marijuana use from ages 13–24 among African-American and White males. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;121:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Grucza RA, Agrawal A, Krauss MJ, Cavazos-Rehg PA, Bierut LJ. Recent trends in the prevalence of marijuana use and associated disorders in the united states. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:300–301. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guxens M, Nebot M, Ariza C. Age and sex differences in factors associated with the onset of cannabis use: a cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W. The adverse health effects of cannabis use: what are they, and what are their implications for policy? Int. J. Drug Policy. 2009;20:458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Aharonovich EA, Alderson D. Alcohol consumption and posttraumatic stress after exposure to terrorism: effects of proximity, loss, and psychiatric history. Am. J. Public Health. 2007;97:2268–2275. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Zhang H, Jung J, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, Grant BF. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the united states between 2001 and 2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayaki J, Hagerty CE, Herman DS, de Dios MA, Anderson BJ, Stein MD. Expectancies and marijuana use frequency and severity among young females. Addict. Behav. 2010;351:995–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayatbakhsh MR, Najman JM, Bor W, OCallaghan MJ, Williams GM. Multiple risk factor model predicting cannabis use and use disorders: a longitudinal study. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;356:399–407. doi: 10.3109/00952990903353415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Howells W, Bucholz KK, Glowinski AL, Nelson EC, Madden PAF. Ascertainment of a mid-western US female adolescent twin cohort for alcohol studies: assessment of sample representativeness using birth record data. Twin Res. 2002;5:107–112. doi: 10.1375/1369052022974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedzior KK, Laeber LT. A positive association between anxiety disorders and cannabis use or cannabis use disorders in the general population- a meta-analysis of 31 studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, Hettema JM, Myers J, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevorkian S, Bonn-Miller MO, Belendiuk K, Carney DM, Roberson-Nay R, Berenz EC. Associations among trauma posttraumatic stress disorder, cannabis use, and cannabis use disorder in a nationally representative epidemiologic sample. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2015;29:633–638. doi: 10.1037/adb0000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hasin DS. Stressful life experiences alcohol consumption, and alcohol use disorders: the epidemiologic evidence for four main types of stressors. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2011;21:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: data from a national sample. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon VV, Sartor CE, Pommer NE, Bucholz KK, Nelson EC, Madden PA, bHeath AC. Age at trauma exposure and PTSD risk in young adult women. J. Trauma. Stress. 2010;23:811–814. doi: 10.1002/jts.20577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Buka SL, bKessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the national comorbidity survey. Am. J. Public Health. 2001;91:753–760. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EC, Heath AC, Madden PAF, Cooper ML, Dinwiddie SH, Bucholz KK, Glowinski A, McLaughlin T, Dunne MP, Statham DJ, Martin NG. Association between self-reported childhood sexual abuse and adverse psychosocial outcomes: results from a twin study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:139–145. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Kawasaki A, Spitznagel EL, Hong BA. The course of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse, and somatization after a natural disaster. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2004;192:823–829. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000146911.52616.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Lynskey M, Hall W. Cannabis use and mental health in young people: cohort study. BMJ. 2002;325:1195–1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, Koenen KC. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychol. Med. 2011;41:71–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Orvaschel H, Anthony JC, Blazer DG, Burnam A, Burke JD. Epidemiologic Field Methods In Psychiatry: The NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Bethesda: NIH; 1985. The diagnostic interview schedule; pp. 143–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Duncan AE, Grant JD, Nelson EC, Madden PA, Heath AC, Bucholz KK. Cannabis or alcohol first?: Differences by ethnicity and in risk for rapid progression to cannabis-related problems in women. Psychol. Med. 2013a;43:813–823. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Waldron M, Duncan AE, Grant JD, McCutcheon VV, Nelson EC, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Heath AC. Childhood sexual abuse and early substance use in adolescent girls: the role of familial influences. Addiction. 2013b;108:993–1000. doi: 10.1111/add.12115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Agrawal A, Grant JD, Duncan AE, Madden PAF, Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Bucholz KK. Differences between African-American and European-American women in the association of childhood sexual abuse with initiation of marijuana use and progression to Problem use. J. Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76:569–577. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp LP. Stata Data Analysis And Statistical Software. Special Edition Release. 2007;10 [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TN, Kung EM, Farrell AD. Relation between witnessing violence and drug use initiation among rural adolescents: parental monitoring and family support as protective factors. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2004;33:488–498. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Sims L, Kingree JB, Windle M. Longitudinal associations between Problem alcohol use and violent victimization in a national sample of adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health. 2008;421:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Foa EB. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2006;132:959–992. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuchman E. Women and addiction: the importance of gender issues in substance abuse research. J. Addict. Dis. 2010;29:127–138. doi: 10.1080/10550881003684582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron M, Bucholz KK, Lynskey MT, Madden PAF, Heath AC. Alcoholism and timing of separation in parents: findings in a midwestern birth cohort. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:337–348. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K, Elliott JC, Shmulewitz D, Aharonovich E, Strous R, Frisch A, Weizman A, Spivak B, Grant BF, Hasin D. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder and risk for alcohol, nicotine, and marijuana dependence in Israel. Compr. Psychiatry. 2014;55:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Ruggiero KJ, Hanson RF, Smith DW, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Witnessed community and parental violence in relation to substance use and delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. J. Trauma. Stress. 2009;22:525–533. doi: 10.1002/jts.20469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotor AJ, Theodore AD, Chang JJ, Berkoff MC, Runyan DK. Speak softly-and forget the stick: corporal punishment and child physical abuse. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008;35:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]