Abstract

Introduction

Deficient sensory input from damaged ankle ligament receptors is thought to contribute to sensorimotor deficits in those with chronic ankle instability (CAI). Targeting other viable sensory receptors may then enhance sensorimotor control in these patients. The purpose of this randomized controlled trial was to evaluate the effects of 2 weeks of sensory-targeted rehabilitation strategies (STARS) on patient- and clinician-oriented outcomes in those with CAI.

Methods

Eighty patients with self-reported CAI participated. All patients completed patient-oriented questionnaires capturing self-reported function as well as the weight-bearing lunge test (WBLT) and an eyes closed single limb balance test. After baseline testing, patients were randomly allocated to four STARS groups: joint mobilization (JM), plantar massage (PM), triceps surae stretching (TS), or control (CON). Each patient in the intervention groups received six, five-minute treatments of their respective STARS over two weeks. All subjects were reassessed on patient and clinician oriented measures immediately following the intervention and completed a one-month follow up that consisted of patient-oriented measures. Change scores of the three STARS groups were compared to the CON using independent t-tests and Hedge’s g effect sizes (ES) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

The JM group had the greatest WBLT improvement. PM had the most meaningful single limb balance improvement. All STARS groups improved patient-oriented outcomes with JM having the most meaningful effect immediately after the intervention and PM at the one-month follow up.

Conclusion

Each STARS treatment offers unique contributions to the patient and clinician oriented rehabilitation outcomes of those with CAI. Both JM and PM appear to demonstrate the greatest potential to improve sensorimotor function in those with CAI.

Keywords: Somatosensory System, Manual Therapy, Postural Control, Patient-Oriented Outcomes, Lower Extremity Injury

Introduction

Ankle sprains are the most common injuries associated with physical activity and athletic participation, accounting for approximately 60% of all injuries that occur during interscholastic and intercollegiate sports. (9, 19) Additionally, an estimated 625,000 lateral ankle sprains are seen in United States emergency departments annually. (38) Data from a prospective cohort of interscholastic athletes would suggest that the comprehensive costs (i.e. direct medical costs and human capital costs) of a lateral sprain would be approximately $9,000 to 12,000 per injury. (22) Using these estimates, annual comprehensive costs could be as high as $7.5 billion (625,000 sprains × $12,000). Further, about 30% of those who incur a first time lateral ankle sprain develop chronic ankle instability (CAI) characterized by recurrent ankle sprains, episodes of ankle giving way, and decreased functional performance; (14) however this number has been reported as high as 75%. (1, 32) Those with CAI also have a greater propensity to develop ankle osteoarthritis compared to those with no history of ankle injury. (36) The residual symptoms that define CAI significantly alter an individual’s health and function by causing them to become less active over their life span. (37) Given the high incidence of lateral ankle sprains and CAI, it is not surprising that the total number of lateral ligament reconstructions and ankle arthroscopy procedures increased by over 17% from 2007–2011. (40) Both of these outpatient procedures are common in the treatment of CAI and thus represent another level of healthcare utilization by individuals who have sustained a lateral ankle sprain. Thus ankle sprains, while often viewed as mild injuries, (30) represent a significant public health problem (35, 37) and a major healthcare burden.

Residual symptoms associated with CAI encompass both sensory (18, 25) and motor (3, 17, 42) aspects of sensorimotor function. Despite deficits in both sensory and motor aspects of sensorimotor control, traditional rehabilitation strategies for CAI focus almost exclusively on motor pathway impairments (i.e. strength, coordination). (39) Similarly, most research on CAI has focused only on maximizing motor output, ignoring the full spectrum of sensorimotor dysfunction associated with CAI. (21, 27) Unfortunately, the high recurrence rates, incidence of post-traumatic ankle osteoarthritis, and consequent healthcare burdens clearly indicate that such an emphasis may be ineffective in reducing CAI development and recurrence.

Research has demonstrated that the sensorimotor system dynamically shifts reliance on various sensory inputs depending on the demands placed on the system. (31) These inputs include ankle joint receptors, plantar receptors of the foot, and the musculotendinous receptors specifically within the triceps surae. There have been investigations in which these sources have been manipulated and profound effects on sensorimotor control have been identified. (8, 16, 23, 26, 29) For example, constraining ankle articular receptor information from healthy individuals has deleterious effects on postural control. (26) However, stimulating various foot/ankle complex receptors through various manual therapies has improved postural control in those with CAI. (15, 23) Based on this evidence, there appears to exist an opportunity to advantageously focus on these sensory inputs through manual therapy techniques such as ankle joint mobilizations, plantar massage, and triceps surae stretching to effectively rehabilitate CAI, but our understanding of the unique contributions associated with these sensory-targeted ankle rehabilitation strategies remains unclear. Therefore, the purpose of this investigation was to determine the efficacy of the three sensory-targeted ankle rehabilitation strategies (triceps surae stretching, ankle joint mobilizations, and plantar massage) at causing immediate and prolonged improvements in subjective and objective outcome measures of clinical disablement and sensorimotor dysfunction in those with CAI. We hypothesize that sensory-targeted ankle rehabilitation strategies directed to three unique sources of sensory input (musculotendinous receptors, ankle joint receptors, plantar receptors) will result in specific and unique improvements in clinician-oriented measures of sensorimotor system function and patient-oriented measures of clinical disablement.

Methods

Design & Participants

This study was a clinical trial that used a multicenter, mutli-arm parallel randomized control study design with a 1-month follow-up period. This was a non-inferiority trial, testing the efficacy of three types of sensory-targeted ankle rehabilitation strategies: ankle joint mobilization, plantar massage, and triceps surae stretching at improving patient-, and clinician-oriented outcome measures in individuals with CAI. Participants received one of the three treatment conditions or were assigned to the control group in a 1:1:1:1 ratio at each site. Once the trial was initiated, no changes were made to the study design or outcome measures. Trial registration number is NCT01541657.

Participants with CAI were recruited through advertisements and word of mouth between January 2012 and February 2014 from the general population (i.e. student, staff, and faculty) of three large public universities in the United States and tested in research laboratories on the respective campuses. For this investigation, CAI was defined as those individuals with a history of at least two episodes of “giving way” within the past 6 months; scoring ≥ 5 on the Ankle Instability Instrument (AII), scoring ≤ 90% on the FAAM, and scoring ≤ 80% on the FAAM Sport (FAAM-S). (15) Exclusion criteria will consisted of failing to meet the above mentioned inclusion criteria and/or sustaining an acute ankle sprain in the 6 week prior to screening, a previous history of ankle surgeries, lower extremity surgeries associated with internal derangements or repairs, and/or other conditions known to affect sensorimotor function. This investigation was initiated prior to the International Ankle Consortium’s published recommendations, (10–12) but the inclusion/exclusion criteria are consistent with those recommended. The protocol was approved by the research and ethics committees for each institution and all individuals provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Sample Size

Using data from a previous study, (16) which examined the effects of joint mobilization on similar outcome measures, our preliminary power analysis (GPower: version 2.0, University of Dusseldorf, Germany), determined that the number of participants necessary to detect significant changes was 16 per group, based on 1-β=0·90, α=0·10, and the most conservative effect size from a preliminary study (16) on the immediate effects of joint mobilization on the mean of time to boundary minima in the mediolateral direction with eyes open (effect size = 0.4). Thus, 20 participants per group were recruited to account for a planned 20% dropout rate.

Randomization

Following baseline testing, participants were randomized into one of three treatment groups or the control group using sealed opaque envelopes that were created at each institution prior to the initiation of the investigation by individuals not involved with the investigation. In accordance with the data safety officer, randomization procedures were conducted in blocks of 8 at each institution with each block containing two assignments to each group. The primary investigators were responsible for both participant enrollment and oversaw randomization procedures.

Interventions

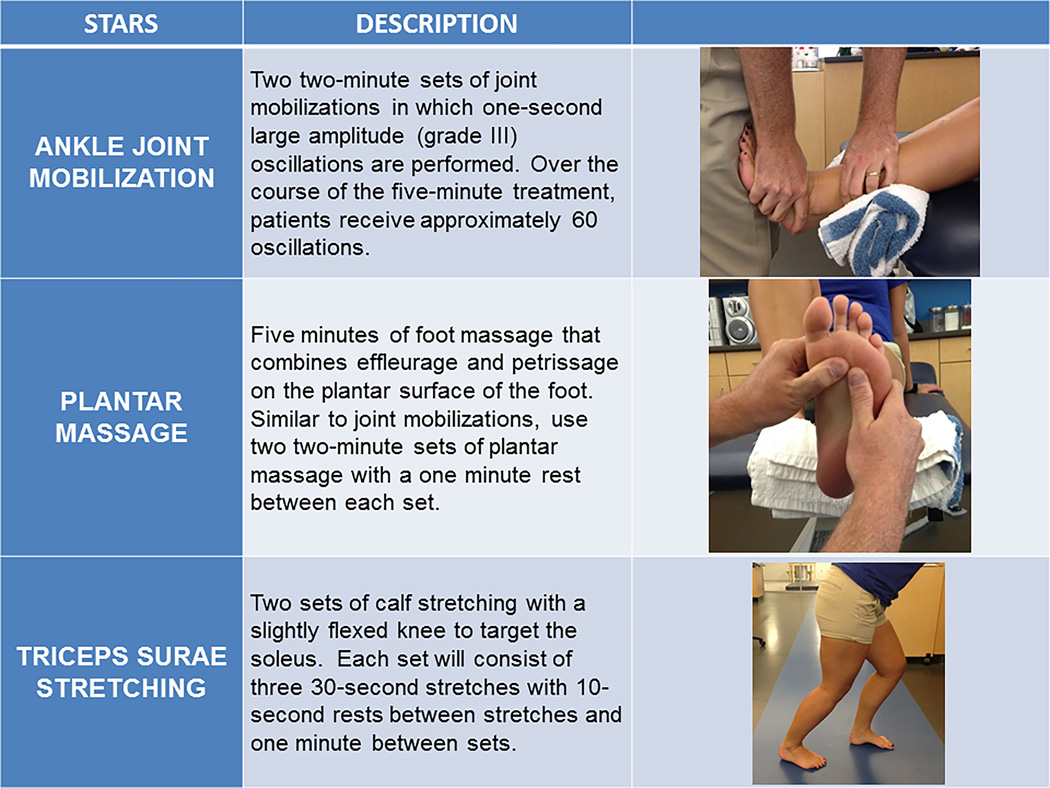

All treatment sessions consisted of a single participant and a primary investigator. Each participant in the treatment groups received a total of six treatment sessions of their assigned sensory-targeted ankle rehabilitation strategy (STARS) over a two-week period and each treatment session lasted 5-minutes in duration. A single treatment session was performed per day with at least 24 hours between treatment sessions across the two weeks. See figure 1. The joint mobilization STARS group received two sets of ankle joint mobilizations. Each set consisted of two-minutes of Grade III anterior-to-posterior talocrural joint mobilizations with a one-minute rest between sets with the patient in a long-sitting position. (15) This mobilization was operationally defined as large-amplitude, one-second rhythmic oscillations from the mid- to end ROM with translation taken to tissue resistance. The plantar massage STARS group received two, two-minute plantar massage sets with a one minute rest between sets. This massage was operationally defined as a combination of petrissage and effleurage to the entire plantar aspect of the foot with the patient supine. (23) However, no effort was made to constrain the time spent using each technique or the location of the massage. The triceps surae stretching STARS group performed two sets of heel cord (i.e. calf) stretching. Each set consisted of three, 30-second stretches with a ten-second rest between stretches and a one-minute rest between sets. Participants stood on an adjustable slant board, so that the calf musculature and musculotendinous unit was gently stretched. Each participant in the control group received no treatment or sham condition and sat quietly for five-minutes during the first treatment session. Control participants were not required to return for additional treatment sessions. All participants were asked to maintain the same level of physical activity and lifestyle over the duration of the study.

Figure 1.

The Sensory-Targeted Ankle Rehabilitation Strategies (STARS) interventions. All subjects allocated to the treatment groups completed 6 sessions of the randomly assigned STARS treatments.

Outcomes

Primary and secondary outcomes focused on two construct areas: patient-, and clinician-oriented measures. (28) Patient-oriented outcome measures included self-reported disability and self-reported physical activity levels. Self-reported disability was recorded using the FAAM and FAAM-S as part of the eligibility screening. Lower percentages (patient’s score divided by max score) represent greater disability. All participants were asked to rate their level of self-reported function on these scales for both the treatment and non-treatment limbs. In addition, participants completed the National Aeronatics and Space Administration (NASA) Physical Activity Status Scale (PASS), an indicator of aerobic fitness. (13) The PASS allows each participant to rate his/her level of physical activity over a set time period. At the time of inclusion in the study, participants reported the number of giving way episodes experienced within the past 3 months. This was operationally defined as “the regular occurrence of uncontrolled and unpredictable episodes of excessive inversion of the rear foot, which do not result in an acute ankle sprain”. (5, 10–12) All patient-oriented outcomes were recorded at baseline (pre intervention), within 72-hours of the final treatment session (Post-Test 2), and at 1 month Follow-Up.

Clinician-oriented outcomes included weight-bearing dorsiflexion range of motion (ROM) and single limb balance. Dorsiflexion ROM was measured using the weight bearing lunge test (WBLT) in accordance to a previously estabilished protocol. (2) Measuring distance with the WBLT has been shown to have excellent inter-rater and intra-rater reliability (2) and discriminate between those with CAI and healthy uninjured controls. (33) Single limb balance was assessed by counting the number of errors that occurred during three, 20-second trials of single limb balance test (SLBT) on a firm surface with eyes closed in accordance to a previously established protocol. (7) Potential errors included 1) touching down with the opposite limb, 2) lifting hands off of the hips, 3) lifting the forefoot or rearfoot of the stance foot, 4) opening the eyes, 5) moving the hip into more than 30 degrees of flexion or abduction, 6) stepping, stumbling, or falling, or 7) remaining out of the test position for more than 5 seconds. If more than one error occurred simultaneously, it was simply counted as one error. (7) Previous research has demonstrated good inter-tester reliability for this test. (34) All clinician-oriented outcomes were recorded at baseline (pre intervention), immediatly following the first STARS and control (5-minutes of quiet sitting) session (Post test 1), and at post-test 2 on both the treated and nontreated limbs. All assessment periods were conudcted using identical methodology.

Statistical Analysis

The primary hypothesis was that all three sensory-targeted ankle rehabilitation strategies would improve patient-oriented outcomes, but each would have unique influences on the clinician-oriented measures of sensorimotor function. The outcome of interest for each of the variables was the amount of change due to the intervention. Thus, all patient-oriented outcome measures were analyzed using change scores from baseline to Post-Test 2 and at 1-month follow-up. The clinician-oriented outcomes were also analyzed using change scores but from baseline to Post-Test 1 and Post-Test 2. In order to explore the effects each treatment had on these measures, the control group was used as the reference group. Change scores of the three treatment groups were compared to the control group using independent sample t-tests and bias corrected Hedge’s g effect sizes (ES) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Hedge’s g effect sizes were interpreted as less than 0.3 as small, 0.31–0.7 moderate, and greater than 0.71 as large. An alpha level set a priori at 0.10 was used for all statistical analyses. Additionally, the measurement error for all outcomes was assessed utilizing the non-treatment limb change from baseline to post-test 2. For the patient-oriented measures (FAAM and FAAM-S, Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess reliability. For the clinician-oriented measures, an ICC(2,3) model was employed. From the reliability estimates, the minimum detectable change (MDC) was calculated from the standard error of the measurement (SDpre-test, post-test 2 * √1-ICC) and multiplied by √2 to determine the amount of change needed to go beyond the typical measurement error for the outcome. (16) The changes calculated within the treatment limb as described above were then evaluated with their respective MDCs.

Results

Baseline characteristics for each group can be seen in Table 1. The Consort Statement flow diagram for the STARS trial is presented in the appendix (See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, Appendix—the STARS Consort Statement flow diagram). At Follow-up there was an ~94% (75/80) retention rate with no differences in loss to follow-up among the trial groups and no suggestion of differences between those lost to follow-up and those remaining in the trial at the 1-month assessment. There were no related adverse events during the study. Because of the high retention rate, an intention to treat analysis was not performed. Missing data were simply removed from the analysis. The minimum detectable change, means, standard deviations, change scores, and resulting p values for all primary and secondary outcome measures can be seen in Tables 2 (patient-oriented) and 3 (clinician-oriented). Figures 2 (patient-oriented) and 3 (clinician-oriented) illustrate the effect sizes and 95% CI of the primary and secondary outcome measures.

Table 1. Baseline Demographics and injury history information for all groups and overall.

Participant demographics across the 4 treatment groups within the Sensory-Targeted Ankle Rehabilitation Strategies (STARS) trial.

| Control | Joint Mobilizations | Plantar Massage | Calf Stretching | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 22.9±4.5 | 23.6 ± 6.7 | 22.3 ± 2.7 | 22.0 ± 2.8 | 22.7 ± 4.4 |

| Height (cm) | 170.5 ± 6.1 | 171.8 ± 9.6 | 171.7 ± 8.2 | 170.8 ± 13.2 | 171.2 ± 9.5 |

| Weight (kg) | 76.1 ± 13.9 | 77.5 ± 18.7 | 74.6 ± 14.3 | 69.2 ± 16.5 | 74.4 ± 16.0 |

| Female, n (%) | 12 (60%) | 11 (55%) | 12 (60%) | 12 (60%) | 47 (57%) |

| Race group white, n (%) | 14 (60%) | 15 (75%) | 14 (60%) | 18 (90%) | 65 (76%) |

| AII “yes” responses | 6.7 ± 1.2 | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 6.4 ±1.2 | 6.8 ± 1.4 | 6.7 ± 1.4 |

| Total # of sprains | 5.1 ± 3.9 | 4.4 ± 3.4 | 4.1 ± 3.1 | 6.3 ± 3.8 | 4.9 ± 3.6 |

| Time since last sprains (months) | 20.2 ± 28.2 | 11.2 ± 8.8 | 25.5 ± 32.6 | 12.7 ± 9.6 | 17.4 ± 22.8 |

| Giving way episodes (3 months) | 5.3 ± 4.5 | 4.7 ± 3.7 | 5.6 ± 4.7 | 6.6 ± 6.0 | 5.5 ± 4.8 |

| FAAM-ADL (%) | 82.0 ± 8.5 | 80.7 ± 10.5 | 76.8 ± 12.9 | 75.7 ± 12.4 | 78.9 ± 11.3 |

| FAAM-S (%) | 63.6 ± 12.6 | 63.0 ± 12.3 | 62.7 ± 13.6 | 61.0 ± 14.9 | 62.6 ± 13.1 |

| NASA PASS | 6.0 ± 2.2 | 5.6 ± 2.2 | 6.7 ± 1.7 | 6.5 ± 2.1 | 6.2 ± 2.1 |

Table 2. Patient-Oriented Outcome Measures. Minimum detectable change, means and standard deviations, respective change from baseline, and p values for STARS change comparisons to control.

Patient-oriented outcome changes from baseline to post-test 2 and 1 month follow up.

| Baseline | Post-Test 2 | Six Treatment Δ | p-value (Δ vs. Control Δ) |

Follow-up | Follow-up Δ | p-value (Δ vs. Control Δ) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foot & Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM) (%) | |||||||

| Cronbach’s α = 0.91, MDC = 4.8% | |||||||

| Control | 81.96±8.45 | 81.70±8.99 | −0.13±6.94 | - | 82.83±10.18 | 1.00±6.54 | - |

| Joint Mobilizations | 80.65±10.51 | 85.24±9.02 | 4.58±9.93 | 0.096 | 86.59±11.91 | 6.26±8.29 | 0.036 |

| Massage | 76.75±12.86 | 84.39±11.40 | 7.64±6.84 | 0.001 | 88.22±10.81 | 11.46±12.66 | 0.002 |

| Calf Stretching | 75.65±12.44 | 85.00±13.18 | 8.64±8.81 | 0.001 | 86.71±9.81 | 11.11±8.37 | <0.001 |

| FAAM-Sport (%) | |||||||

| Cronbach’s α = 0.90, MDC = 7.6% | |||||||

| Control | 63.59±12.63 | 65.15±12.42 | 1.56±9.09 | - | 66.44±11.54 | −0.46±18.59 | - |

| Joint Mobilizations | 62.97±12.26 | 73.90±13.68 | 10.93±13.04 | 0.012 | 74.84±18.23 | 8.13±22.63 | 0.197 |

| Massage | 62.66±13.60 | 70.39±19.79 | 7.73±11.84 | 0.075 | 75.16±17.99 | 12.5±17.71 | 0.032 |

| Calf Stretching | 61.02±14.88 | 67.81±18.25 | 6.78±14.84 | 0.187 | 74.83±14.39 | 7.46±10.51 | 0.062 |

| Episodes of Giving Way (episodes per week) | |||||||

| Control | 0.43±0.37 | 0.85±1.17 | 0.41±1.07 | - | 0.67±0.98 | 0.23±0.88 | - |

| Joint Mobilizations | 0.39±0.31 | 0.55±0.48 | 0.16±0.48 | 0.341 | 0.42±0.57 | 0.01±0.52 | 0.323 |

| Massage | 0.46±0.39 | 0.31±0.42 | −0.16±0.54 | 0.038 | 0.18±0.24 | −0.29±0.49 | 0.024 |

| Calf Stretching | 0.48±0.43 | 0.32±0.46 | −0.13±0.50 | 0.045 | 0.23±0.24 | −0.22±0.50 | 0.048 |

| NASA Physical Activity Status Scale (numerical scale) | |||||||

| Cronbach’s α = 0.93, MDC = 0.8 points | |||||||

| Control | 5.95±2.23 | 6.20±2.14 | 0.25±1.06 | - | 6.36±1.97 | 0.10±1.25 | - |

| Joint Mobilizations | 5.55±2.21 | 5.85±2.39 | 0.30±1.08 | 0.883 | 5.63±2.40 | −0.20±2.14 | 0.591 |

| Massage | 6.73±1.72 | 6.73±1.72 | 0.00±0.88 | 0.432 | 6.52±2.06 | −0.21±1.71 | 0.521 |

| Calf Stretching | 6.50±2.06 | 6.50±1.98 | 0.00±1.16 | 0.489 | 6.27±2.29 | −0.85±2.66 | 0.156 |

Table 3. Clinician-Oriented Outcome Measures. Minimum detectable change (MDC), means and standard deviations, respective change from baseline, and p values for STARS change comparisons to control.

Clinician-oriented outcome changes from baseline to post-test 1 and post-test 2.

| Baseline | Post-Test 1 | Single Treatment Δ |

p-value (Δ vs. Control Δ) |

Post-Test 2 | Six Treatment Δ |

p-value (Δ vs. Control Δ) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Bearing Lunge Test (cm) | |||||||

| ICC(2,3) = 0.98, MDC = 0.75 cm | |||||||

| Control | 8.04±4.18 | 8.54±4.15 | 0.50±1.26 | - | 7.88±4.38 | −0.16±1.09 | - |

| Joint Mobilizations | 8.18±2.84 | 9.75±2.98 | 1.57±1.46 | 0.018 | 10.41±2.74 | 2.23±2.01 | <0.001 |

| Massage | 10.46±4.44 | 11.17±4.73 | 0.71±0.81 | 0.55 | 11.15±4.25 | 0.69±1.13 | 0.021 |

| Calf Stretching | 9.89±2.80 | 11.04±2.64 | 1.15±1.01 | 0.08 | 11.14±2.84 | 1.24±0.99 | <0.001 |

| Single Limb Balance Test (errors) | |||||||

| ICC(2,3) = 0.86, MDC = 1 error | |||||||

| Control | 2.86±1.92 | 2.86±1.99 | 0.00±0.93 | - | 3.41±2.05 | 0.55±1.52 | - |

| Joint Mobilizations | 2.83±2.10 | 1.85±1.76 | −0.98±1.47 | 0.016 | 2.06±1.60 | −0.76±1.17 | 0.004 |

| Massage | 3.28±1.74 | 2.15±2.02 | −1.12±1.67 | 0.012 | 1.84±1.64 | −1.43±1.53 | <0.001 |

| Calf Stretching | 3.08±2.55 | 2.11±2.14 | −0.96±1.51 | 0.019 | 2.73±2.41 | −0.35±1.15 | 0.042 |

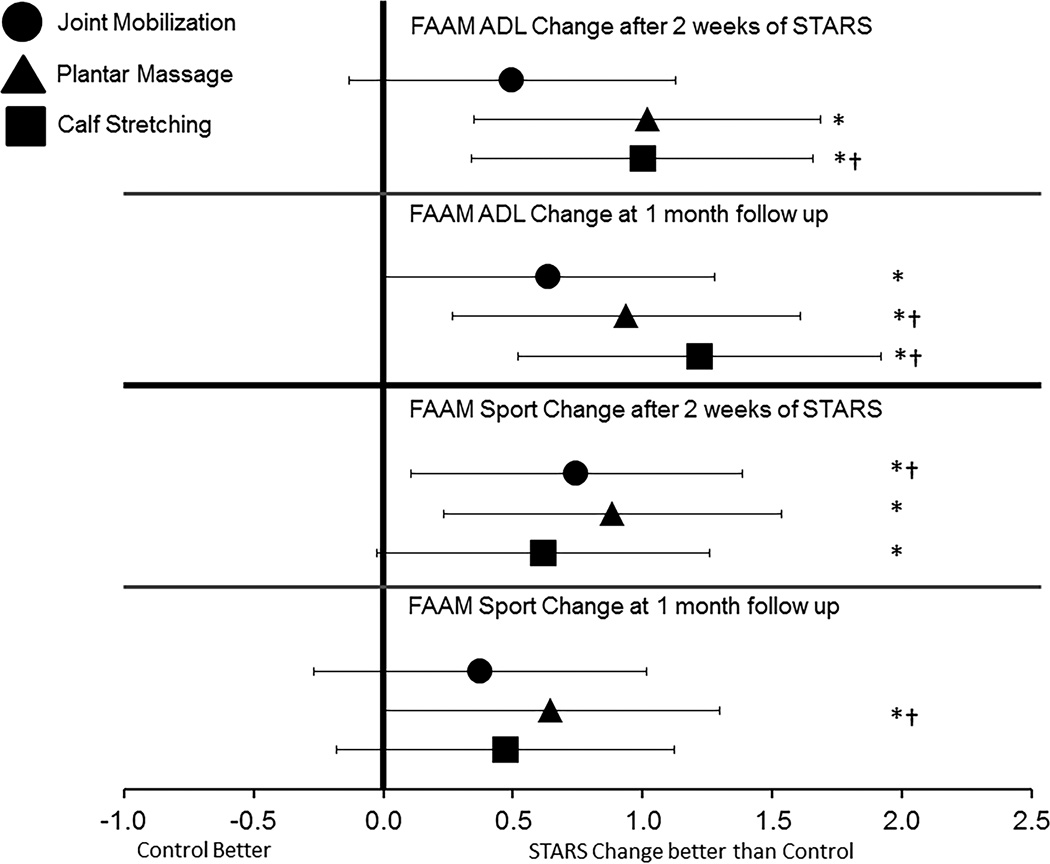

Figure 2.

Bias-corrected Hedge’s g estimates of effect size with 95% confidence intervals. All effect sizes were calculated based on the change in the respective STARS group in comparison to the change in the control group from baseline to post-test 2 and the 1 month follow up. Point measures that fall to the right of the zero line indicates that the STARS change was comparatively larger than the control group change. * indicates that the change also exceeded the minimum detectable change calculated from the reliability estimates of the opposite limb change from baseline to post-test 2. † indicates that the change in the STARS group exceeded the established minimum clinically important difference established for the outcome measure.

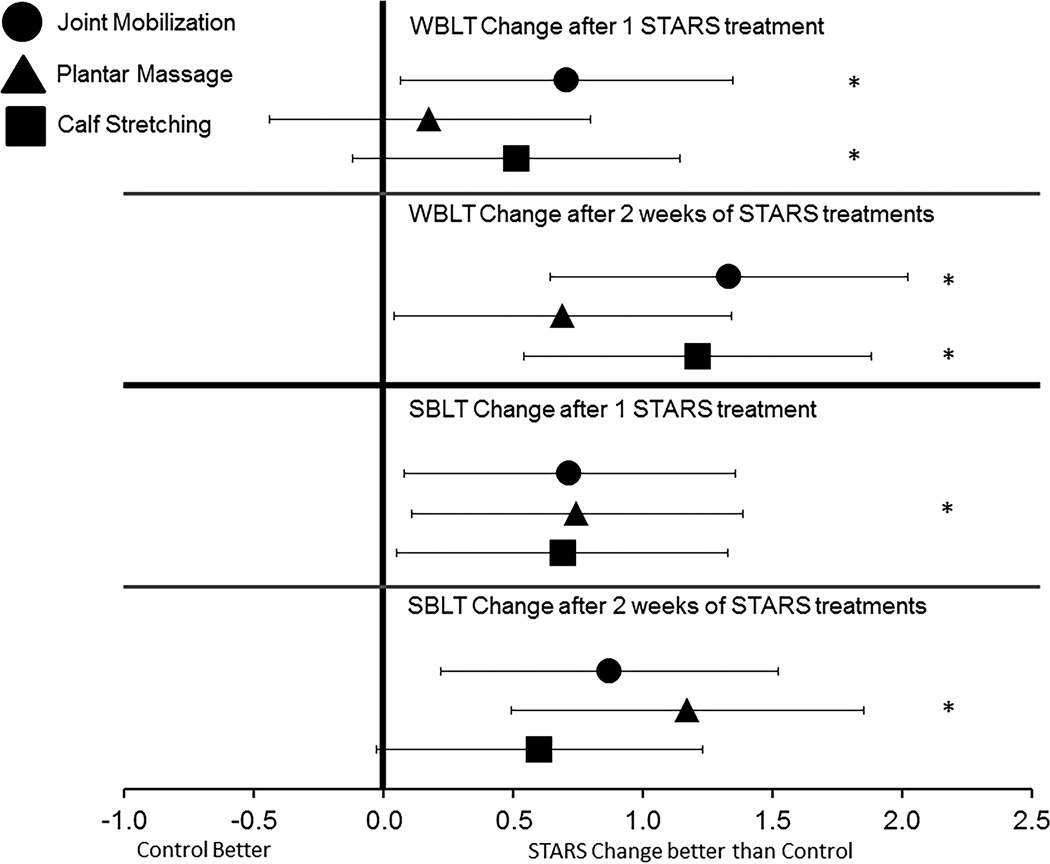

Figure 3.

Bias-corrected Hedge’s g estimates of effect size with 95% confidence intervals. All effect sizes were calculated based on the change in the respective STARS group in comparison to the change in the control group from baseline to post-test 1 and post-test 2. Point measures that fall to the right of the zero line indicates that the STARS change was comparatively larger than the control group change. * indicates that the change also exceeded the minimum detectable change calculated from the reliability estimates of the opposite limb change from baseline to post-test 2.

Patient-Oriented Outcomes

Upon completion of the 2 weeks of STARS interventions, plantar massage and calf stretching demonstrated the largest improvements in the FAAM ADL with statistically significant change scores compared to the control group that exceeded the MDC (see table 2). These changes resulted in large effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals that did not cross zero (see figure 2). The change within the joint mobilization did not reach statistical significance, nor did it exceed the MDC. At the one month follow-up, all 3 STARS groups demonstrated statistically significant changes compared to the control group which exceeded the MDC. The largest effect size was found within the calf stretching group with confidence intervals that did not cross zero.

The FAAM-S revealed a different pattern (see table 2). After 2 weeks of STARS, both joint mobilizations and plantar massage had statistically significant improvements compared to the control group that exceeded the MDC with large effect sizes and confidence intervals that did not cross zero (see figure 2). At the one-month follow-up, only the plantar massage group demonstrated a statistically significant improvement that exceeded the MDC and produced a large effect size with confidence intervals that did not cross zero.

Based on the results of the weekly episodes of giving way, it appeared that both the calf stretching and plantar massage groups demonstrated statistically significant reductions in the episodes of giving way reported after 2 weeks of treatment and continued to the 1-month follow up compared to the control group (see table 2). The joint mobilization group did not demonstrate a substantial reduction in episodes of giving way after treatment or at the 1-month follow-up.

Lastly, it is important to note that across the study, none of the STARS groups demonstrated a statistically significant change in their physical activity status compared to the control group (see table 2). This indicates that changes in physical activity may not be a factor in the improvements in self-reported function identified through the FAAM-ADL and FAAM-S scales.

Clinician-Oriented Outcomes

The findings from the WBLT revealed that both the calf stretching group and the joint mobilization groups demonstrated significant improvements in dorsiflexion range of motion compared to the control group which also exceeded the MDC after both the initial treatment and the 2-weeks of treatment (See table 3). The largest change was found within the joint mobilization group after both the initial treatment and after all 6 treatments. The joint mobilization group also demonstrated the largest effect size with a confidence interval that did not cross zero (see figure 3).

The SLBT findings revealed that after the initial STARS treatment, all groups demonstrated statistically significant improvements with large effect sizes and confidence intervals that did not cross zero. However, only the plantar massage group had an improvement which exceeded the MDC (see table 3). After the initial STARS treatment, this group had a reduction in the number of errors committed on the SLBT by at least 1. This pattern continued after the full 2-weeks of treatment. Only the plantar massage group demonstrated a statistically significant improved in the SLBT that exceeded the MDC (see table 3) and produced the largest effect size (see figure 3).

Discussion

The main findings suggest that, indeed, each STARS does provide unique sets of contributions to CAI-associated impairments. For example, dorsiflexion restrictions are a common clinical impairment in CAI (33) and improving the available range of motion, a structural adaptation to repetitive injury, can have implications for enhancing functional movement patterns. (15) Joint mobilizations resulted in an immediately more meaningful treatment effect compared to the stretching group with confidence intervals that did not cross zero (Figure 3). After two-weeks of treatment, the joint mobilization group continued to see improvements, whereas by contrast, the stretching group had no greater change beyond the immediate effect. However, the magnitude of the effect at the 2 week mark was similar for both stretching and joint mobilizations with confidence intervals that did not cross zero. These findings suggest that targeting potential arthrokinematic restrictions of posterior talar glide results in comparatively greater improvement in range of motion initially and supports the hypothesis that ankle sprains may cause positional faults of the talus and fibula. (20, 41) As well, based on the changes reported, the joint mobilization group had a two-fold increase in dorsiflexion improvement at 2 weeks, but the variability of this improvement also increased. This suggests that 2 weeks of either STARS may be effective in enhancing dorsiflexion.

These dorsiflexion improvements found in the joint mobilization group follow those found in previous studies. For example, Hoch et al. (15) found similar improvements after two weeks of combined ankle joint traction and mobilization and that these changes persisted one week after the final treatment. Using a mobilization with movement technique, Cruz-Diaz et al. (4) observed a 7 mm improvement in dorsiflexion range of motion after 6 treatment sessions that remained at the six month follow-up. Interestingly, the magnitude of mean change we found on the WBLT was three times that of the mobilization with movement study (4) suggesting that future research is needed to determine the comparative effectiveness of joint mobilization techniques.

Single limb balance improved as a result of targeting the sensory pathways via the STARS treatments. Only the plantar massage group demonstrated substantial improvements in single limb balance based on all 3 comparison criteria – statistically significant improvement beyond the MDC that resulted in a large effect size with confidence intervals that did not cross zero. The plantar cutaneous receptors have been shown to play a large role in the maintenance of postural control (23, 31) and it has been proposed that those with CAI may place heavier reliance on these receptors in the absence of relevant information from the ankle. (23, 26) As well, those with CAI have also demonstrated increased sensory detection thresholds on the plantar surface of the foot compared to healthy subjects indicating that CAI individuals process this information differently. (18) Targeting the ankle (joint mobilization) or calf receptors (stretching) resulted in immediate improvement in single limb balance, but not to the extent of plantar massage. These balance improvements are consistent with the findings from LeClaire and Wikstrom (23) who found that plantar massage, but not calf massage significantly improved single limb postural control in patients with CAI.

Self-reported function improved as measured by the FAAM-ADL and FAAM-S scales. Within ADLs, the plantar massage and stretching groups demonstrated the largest effects with confidence intervals that did not cross zero at both the 2-week and 1-month follow-up evaluations. The changes on the ADL scale for the joint mobilization group failed to exceed the MDC or the established MCID (8%) (24) and had confidence intervals that crossed zero. However this group reported the largest change on the FAAM-S scale that exceeded both the MDC and MCID (9%) (24) critical values after 2 weeks of treatment with a large treatment effect compared to the control group with confidence intervals that did not cross zero. The changes found follow a logical pattern. After 2 weeks of joint mobilizations, this STARS group reported enhanced functional ability to run, land, jump, and perform cutting/lateral movements. These improvements may be based on the enhanced functional freedom of restoring dorsiflexion range of motion and are supported by improvements in landing patterns previously reported in those with CAI after receiving joint mobilization treatments. (6) Unfortunately, these self-reported function changes were not seen at the one month follow-up, which indicates that a larger dose may be needed to retain the benefit or some form of maintenance may be required to maintain the sport functional gains.

The plantar massage and stretching groups demonstrated substantial improvements in the ADL compared to the control group with changes that exceeded both the MDC and MCID over the course of the one month follow up. However, only the plantar massage group continued to demonstrate improvements on the FAAM-S scale over the course of the one month follow up period that exceeded the MDC and MCID and these improvements were the largest of all STARS.. The absence of functional gains at immediate post treatment testing and improvements at 1 month suggest that the true effects of stimulating the plantar receptors mature after treatment rather than degrade like the effect of stretching and joint mobilization. Given the opposing maturation trends of joint mobilization and plantar massage, further exploration is needed to determine how these interventions may interact and complement each other. Another important consideration to be explored in future studies is that there may be an effective clinical prediction rule for including certain STARS for CAI patients with specific structural and/or sensorimotor impairments. As well, these treatments would typically not be used in isolation in the treatment of CAI. Developing an understanding of the complementary effects of STARS in a larger CAI rehabilitation protocol is necessary and the current results provide the foundation on which to develop a systematic and logical approach to treating CAI that incorporates STARS.

This study is not without limitations. While we employed a randomized design with concealed allocation across multiple study sites, there was no blinding of the subjects or the examiners. Therefore, there is the possibility of bias within the internal validity of the results. In the absence of blinding, we chose to examine the changes within these measures in multiple ways. Specifically, utilizing the statistical significance, effect sizes with confidence intervals, and the MDC/MCID values afforded us multiple criteria to base our interpretation. It is important to note that while self-reported improvements were found, none of the improvements exceeded the critical values for defining CAI. In the inclusion criteria, CAI was defined as having a self-reported functional deficit of at least 10% on the FAAM-ADL and 20% on the FAAM-S scales. While the improvements found in this study exceeded the critical values associated with measurement error, all subjects would still be classified as having CAI according to the FAAM scales. This is a very important consideration in the development of effective rehabilitation programs for those with CAI. As stated above, these interventions would typically not be used in isolation within a rehabilitation protocol for patients with CAI, but this study marks a major step in developing rehabilitation strategies that incorporate the purposeful manipulation of sensory pathways for functional improvements in those with CAI. These interventions require no equipment, little time, and can be implemented in any clinical environment regardless of facility space or budget restrictions. Future research is needed to validate these results with more stringent control on bias including the blinding of examiners as well as the introduction of sham treatments that may offer further insight into the effectiveness of STARS.

Conclusion

This was the first study to examine the comparative effects of 3 manual therapies which target sensory pathways for the rehabilitation of those with CAI. It is apparent that each STARS treatment offers unique contributions to the rehabilitation outcomes of those with CAI. Joint mobilization resulted in the most meaningful improvements in weight-bearing dorsiflexion whereas plantar massage had the most meaningful effect on single limb balance. Stretching the triceps surae offers benefit as well, but these benefits may be maximized potentially in combination with the other STARS. While STARS would not typically not used in isolation, this study provides initial evidence that the comparative effectiveness can be used to systematically target sensory pathways that may be advantageous in the rehabilitation of CAI. Future studies are needed to determine the extent of benefit of STARS in combination as well as their synergistic effects when combined with other interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, and Skin Diseases (NIAMS 5R03AR061561). The NIAMS was not involved in any of the design, collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests that could potentially bias this work. The results of this study do not constitute endorsement by the ACSM.

SDC 1 - Supplemental Digital Content 1.tif – Appendix: The Consort Statement Flow Diagram of the Sensory-Targeted Ankle Rehabilitation Strategies (STARS) trial.

References

- 1.Anandacoomarasamy A, Barnsley L. Long term outcomes of inversion ankle injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(3):1–4. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.011676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennell KL, Talbot RC, Wajswelner H, Techovanich W, Kelly DH, Hall AJ. Intra-rater and inter-rater reliability of a weight-bearing lunge measure of ankle dorsiflexion. Aust J Physiother. 1998;44(3):175–180. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown C. Foot clearance in walking and running in individuals with ankle instability. The American journal of sports medicine. 2011;39(8):1769–1776. doi: 10.1177/0363546511408872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruz-Diaz D, Lomas Vega R, Osuna-Perez MC, Hita-Contreras F, Martinez-Amat A. Effects of joint mobilization on chronic ankle instability: a randomized controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(7):601–610. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.935877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delahunt E, Coughlin GF, Caulfield B, Nightingale EJ, Lin CC, Hiller CE. Inclusion criteria when investigating insuficiencies in chronic ankle instability. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2010;42(11):2106–2121. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181de7a8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delahunt E, Cusack K, Wilson L, Doherty C. Joint mobilization acutely improves landing kinematics in chronic ankle instability. Med Sci Sports Exer. 2013;45(3):514–519. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182746d0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Docherty CL, Valovich McLeod TC, Shultz SJ. Postural control deficits in participants with functional ankle instability as measured by the balance error scoring system. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16(3):203–208. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200605000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duclos NC, Maynard L, Barthelemy J, Mesure S. Postural stabilization during bilateral and unilateral vibration of ankle muscles in the sagittal and frontal planes. Journal of neuroengineering and rehabilitation. 2014;11:130. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-11-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez WG, Yard EE, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of lower extremity injuries among U.S. high school athletes. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(7):641–645. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.03.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gribble PA, Delahunt E, Bleakley C, et al. Selection criteria for patients with chronic ankle instability in controlled research: a position statement of the International Ankle Consortium. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(13):1014–1018. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gribble PA, Delahunt E, Bleakley CM, et al. Selection criteria for patients with chronic ankle instability in controlled research: a position statement of the international ankle consortium. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(8):585–591. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2013.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gribble PA, Delahunt E, Bleakley CM, et al. Selection criteria for patients with chronic ankle instability in controlled research: a position statement of the International Ankle Consortium. J Athl Train. 2014;49(1):121–127. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heil DP, Freedson PS, Ahlquist LE, Price J, Rippe JM. Nonexercice regression models to estimate peak oxygen consumption. Med Sci Sports Exer. 1995;27:599–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiller CE, Nightingale EJ, Lin CW, Coughlan GF, Caulfield B, Delahunt E. Characteristics of people with recurrent ankle sprains: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(8):660–672. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.077404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoch MC, Andreatta RD, Mullineaux DR, et al. Two-week joint mobilization intervention improves self-reported function, range of motion, and dynamic balance in those with chronic ankle instability. J Orthop Res. 2012;30(11):1798–1804. doi: 10.1002/jor.22150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoch MC, McKeon PO. Joint mobilization improves spatiotemporal postural control and range of motion in those with chronic ankle instability. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(3):326–332. doi: 10.1002/jor.21256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoch MC, McKeon PO. Peroneal reaction time after ankle sprain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(3):546–556. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182a6a93b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoch MC, McKeon PO, Andreatta RD. Plantar vibrotactile detection deficits in adults with chronic ankle instability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(4):666–672. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182390212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):311–319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hubbard TJ, Hertel J, Sherbondy P. Fibular position in those with self-reported chronic ankle instability. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(1):3–9. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.36.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaminski TW, Buckley BD, Powers ME, Hubbard TJ, Ortiz C. Effect of strength and proprioception training on eversion to inversion strength ratios in subjects with unilateral functional ankle instability. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37(5):410–415. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.5.410. discussion 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knowles SB, Marshall SW, Miller T, et al. Cost of injuries from a prospective cohort study of North Carolina high school athletes. Injury Prevention. 2007;13:416–421. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.014720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeClaire J, Wikstrom EA. Massage improves postural control in those with chronic ankle instability. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2012;4(5):213–219. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin RL, Irrgang JJ. A survey of self-reported outcome instruments for the foot and ankle. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37(2):72–84. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2007.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKeon JM, McKeon PO. Evaluation of joint position recognition measurement variables associated with chronic ankle instability: a meta-analysis. J Athl Train. 2012;47(4):444–456. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.4.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKeon PO, Booi MJ, Branam B, Johnson DL, Mattacola CG. Lateral ankle ligament anesthesia significantly alters single limb postural control. Gait Posture. 2010;32(3):374–377. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKeon PO, Hertel J. Systematic Review of postural control and lateral ankle instability, Part 2: Is balance training clinically effective? J Athl Train. 2008;43(3):305–315. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.3.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKeon PO, Medina-McKeon JM, Mattacola CG, Lattermann C. Finding context: a new model for interpreting clinical evidence. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2011;16(5):10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKeon PO, Stein AJ, Ingersoll CD, Hertel J. Altered plantar receptor stimulation impairs postural control in those with chronic ankle instability. Journal of sport rehabilitation. 2012;21(1):1–6. doi: 10.1123/jsr.21.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medina McKeon JM, Bush HM, Reed A, Whittington A, Uhl TL, McKeon PO. Return-to-play probabilities following new versus recurrent ankle sprains in high school athletes. Journal of science and medicine in sport / Sports Medicine Australia. 2014;17(1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterka RJ, Loughlin PJ. Dynamic regulation of sensorimotor integration in human postural control. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91(1):410–423. doi: 10.1152/jn.00516.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters JW, Trevino SG, Renstrom PA. Chronic lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle. 1991;12(3):182–191. doi: 10.1177/107110079101200310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plante JE, Wikstrom EA. Differences in clinician-oriented outcomes among controls, copers, and chronic ankle instability groups. Phys Ther Sport. 2012;14(4):221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riemann BL, Guskiewicz KM, Shields WW. Relationship between clinical and forceplate measures of postural stability. J Sport Rehab. 1999;8:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soboroff SH, Pappius EM, Komaroff AL. Benefits, risks, and costs of alternative approaches to the evaluation and treatment of severe ankle sprain. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;(183):160–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valderrabano V, Hintermann B, Horisberger M, Fung TS. Ligamentous posttraumatic ankle osteoarthritis. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2006;34:612–620. doi: 10.1177/0363546505281813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verhagen RA, de Keizer G, van Dijk CN. Long-term follow-up of inversion trauma of the ankle. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1995;114(2):92–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00422833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waterman BR, Owens BD, Davey S, Zacchilli MA, Belmont PJ., Jr The epidemiology of ankle sprains in the United States. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2010;92(13):2279–2284. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Webster KA, Gribble PA. Functional rehabilitation interventions for chronic ankle instability: a systematic review. Journal of sport rehabilitation. 2010;19(1):98–114. doi: 10.1123/jsr.19.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Werner BC, Burrus T, Park JS, Perumal V, Gwathmey FW. Trends in ankle arthroscopy and its use in the management of pathologic conditions of the lateral ankle in the united states: a national database study. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(7):1330–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wikstrom EA, Hubbard TJ. Talar positional fault in person with chronic ankle instability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(8):1267–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wikstrom EA, Naik S, Lodha N, Cauraugh JH. Balance capabilities after lateral ankle trauma and intervention: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;39(6):1287–1295. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318196cbc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.