Abstract

The primary function of central arteries is to store elastic energy during systole and to use it to sustain blood flow during diastole. Arterial stiffening compromises this normal mechanical function and adversely affects end organs such as the brain, heart, and kidneys. Using an angiotensin-II infusion model of hypertension in wild-type mice, we show that the thoracic aorta exhibits a dramatic loss of energy storage within two weeks that persists for at least four weeks. This diminished mechanical functionality results from increased structural stiffening due to an excessive accumulation of adventitial collagen, not a change in the intrinsic stiffness of the wall. A detailed analysis of the transmural biaxial wall stress suggests that the exuberant production of collagen results more from an inflammatory response than a mechano-adaptation, hence reinforcing the need to control inflammation, not just blood pressure. Although most clinical assessments of arterial stiffening focus on intimal-medial thickening, these results suggest a need to measure and control the highly active and important adventitia.

Keywords: hypertension, arterial stiffness, elastic energy, wall stress, collagen

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is a critical risk factor for many cardiovascular, neurovascular, and renovascular conditions.1–3 Findings over the past two decades suggest that large artery stiffening causes essential hypertension and associated changes in systemic hemodynamics that augment central pulse pressure.4,5. Yet, arteries also stiffen in response to changes in mechanical stress that arise from increased blood pressure, as revealed by several animal models,6–8 and evidenced in humans in aortic coarctation.9 Central artery stiffening can thus be both a cause and a consequence of hypertension and; it likely involves a complex feedback between global changes in hemodynamics/physiology and local changes in wall mechanics/mechanobiology.

Another emerging concept is that inflammation is important in hypertension.10,11 We showed that T-cells and cytokine IL-17a play important roles in the deposition of adventitial collagen in DOCA-salt and angiotensin-II (Ang II) induced hypertension.12 The mechanical analysis performed in that study showed that these forms of hypertension cause a leftward shift in the stress-strain behavior that is often interpreted as stiffening, but did not assess the biaxial wall mechanics, did not compare changes in stiffness or energy storage, and did not consider specific contributions of the adventitia to overall stiffening. We now present the first detailed study of biaxial wall mechanics in induced hypertension based on data collected from the proximal descending thoracic aorta of male wild-type mice following 2 or 4 weeks of Ang II infusion. In particular, we quantified transmurally averaged mechanical properties that are needed to study interactions between the hemodynamics and arterial wall as well as layer-specific properties that are needed to understand differential mechanobiological responses by medial and adventitial cells. Our analyses suggest that early hypertension-induced remodeling of the aorta is mechanically maladaptive in this mouse model, which compromises the ability to store elastic energy and, by inference, to modulate the pulse wave and peripheral perfusion.

METHODS

Animal Model

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University. Briefly, hypertension was induced in male wild-type mice (C57BL/6; Jackson Laboratories) at 3 months of age via chronic infusion of angiotensin-II (Ang II; Sigma-Aldrich) at a continuous rate of 490 ng/kg/min for 2 or 4 weeks using an osmotic mini-pump (Alzet). This pump was implanted subcutaneously on the flank under sterile conditions during a brief surgery in which Ketoprofen (5 mg/kg) was used for pre-anesthesia and ketamine (100mg/kg) and xylazine and 10 (mg/kg) was used for anesthesia. Blood pressure was measured every hour over the up to 4-week study period via an indwelling catheter and telemetry system (Figure S1). At the prescribed endpoint, the mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and the descending thoracic aorta was excised from the left subclavian artery to the third pair of intercostal branches. Age-matched control vessels were obtained similarly, but following a Sham procedure wherein the implanted mini-pumps released normal saline rather than Ang II. Additional details can be found elsewhere.1

The Online Data Supplement describes established methods for biaxial mechanical testing, quantitative histology, and computing wall stress, material stiffness, (an intrinsic property of the wall), structural stiffness (which depends on material stiffness and geometry), and stored energy (http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Statistics

Data in the manuscript are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Geometric and material metrics were compared across all treatment groups (Sham, 2wk Ang II, and 4wk Ang II) using a one-way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Bonferroni correction.

RESULTS

Infusion of Ang II (490 ng/kg/min) increased systemic blood pressure to 167/133 mmHg at 2 weeks, which persisted at 4 weeks (172/129 mmHg). Sham mice had steady state pressures of 121/99 mmHg.12 Figure 1A,B shows mean in vitro pressure-diameter and axial force-length data from two of the seven mechanical testing protocols for all three groups. Clearly, the hypertension-induced remodeling is strongly biaxial: the aortas are less distensible (i.e., they exhibit a reduced range of pressure-induced diameter change; Figure 1A) and less extensible (i.e., a reduced range of force-induced length change; Figure 1B). Shown, too, are stress-stretch behaviors for the pressure-diameter protocol performed at the in vivo axial length and the axial force-length protocol performed at a constant pressure of 100 mmHg (Figure 1C,D). Note the leftward shift and significantly lower values of biaxial wall stress due to hypertension. Importantly, as a result of the marked loss of distensibility and extensibility, hypertension also dramatically reduces elastic energy storage upon biaxial loading (Figure 1E,F).

Figure 1.

Mechanical testing of the proximal descending thoracic aorta from Sham (n=5, black), 2-week (n=5, grey) and 4-week (n=5, white circles) angiotensin-infused mice (mean ± SEM). (A) Pressure-diameter curves at group-specific in vivo axial stretches and (B) axial force-length curves at 100 mmHg plus associated mean (C) circumferential and (D) axial stress-stretch curves. Iso-energy contours for (E) Sham and (F) angiotensin-infused mice (2-week, black; 4-week, grey) wherein filled circles represent the elastically stored energy at group-specific systolic pressures and in vivo axial stretches and solid lines represent the energy level at any biaxial state.

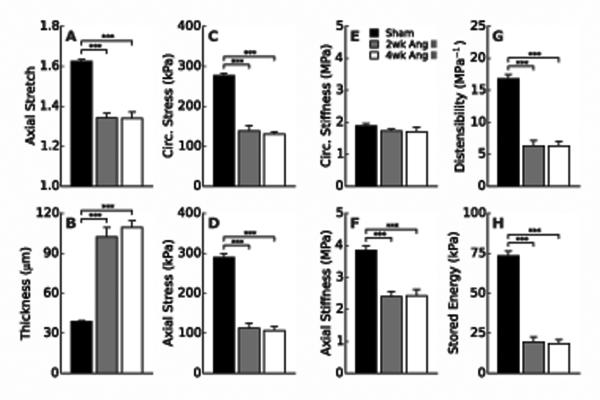

Figure 2A,B suggests that the lower values of wall stress in hypertension (Figure 2C,D) likely result from two primary changes: a significantly lower in vivo axial stretch (<1.35 vs. 1.62, Figure 2A) and a significantly greater wall thickness (>100 vs. 39 μm, Figure 2B). Interestingly, overall circumferential material stiffness is not statistically different between Sham and either Ang II group (2 or 4 weeks); conversely, axial material stiffness is significantly lower in both hypertensive groups, likely due to lower axial stretches (Figure 2E,F). Circumferential structural stiffness is nevertheless higher in hypertension (Figure 2G, Table S1), consistent with a thicker wall, and energy storage is significantly reduced at 2 and 4 weeks (Figure 2H). Hence, despite a remarkable maintenance of overall circumferential material stiffness, hypertension induces striking morphometric (wall thickness and axial stretch), material (axial stiffness and energy storage), and structural (distensibility) changes in the thoracic aorta. For completeness, Supplemental Table S1 lists all morphological and transmurally-averaged mechanical findings and Table S2 lists values of the model parameters that were used to compute stress, stiffness, and stored energy.

Figure 2.

Comparison of morphometric, material, and structural metrics for aortas from Sham (black), 2-week (grey) and 4-week (white) angiotensin-infused mice at group-specific systolic pressures. (A) In vivo axial stretch, (B) wall thickness, mean (C) circumferential and (D) axial wall stress, overall (E) circumferential and (F) axial material stiffness, (G) distensibility, and (H) energy storage. See Online Data Supplement for descriptions of these mechanical quantities (Table S1). ***P < 0.001 between groups.

Figure 3A shows representative histological findings. Verhoeff van Gieson (VVG)-stained sections reveal less undulation of elastic laminae and greater inter-lamellar spacing in hypertension, consistent with smooth muscle hypertrophy and intra-lamellar deposition of thin collagen fibers (green in dark-field picrosirius red (PSR)-images). Masson’s Trichrome (MTC)- and PSR-stained sections show that the most dramatic hypertension-induced change is adventitial thickening due to increased deposition of thick (white in PSR images) fibrillar collagens. Layer-specific histological image analyses (Figure 3B) reveal that, on average, Sham aortas contain 33% elastin, 33% smooth muscle, and 4% collagen in the media (70% of wall), with 1% elastin and 29% collagen in the adventitia (30% of wall). Associated with an ~2.6-fold increase in wall cross-sectional area in hypertension, quantitation reveal an ~1.8-fold increase in smooth muscle and ~3.3-fold increase in medial collagen, which contribute to the mild medial hypertrophy (1.7-fold increase in medial area), but a marked 4.7-fold increase in adventitial collagen that contributes to the large increase in adventitial thickness (4.6-fold increase in adventitial area) and wall percentage (on average, 55% in Ang II vs. 30% in Sham).

Figure 3.

Histological analysis and layer-specific wall composition for representative Sham (A, top row) and 2-week angiotensin-infused (A, bottom row) mice. (A) Stained sections show distributions of elastin (black in VVG), smooth muscle (red in MTC), and collagen (blue in MTC and green-red in PSR). (B) Quantitative area fraction analysis for elastin (white), smooth muscle (light-grey), and collagen (dark-grey) in the media (below dashed line) and adventitia (above dashed line).

Figures 4A and 4B show calculated transmural distributions of aortic wall stress for Sham and 2-week Ang II infused mice at group-specific values of in vivo axial stretch and mean arterial pressure; associated model parameters are in Table S3. Circumferential stress is higher in the media than the adventitia in the Sham group, consistent with the media bearing most of the load under physiologic conditions while the adventitia engages and bears more load when pressure increases acutely above normal levels, as in exercise.13 Circumferential stress is lower and nearly constant across the wall in hypertension, with a reduced difference between layers suggesting a greater engagement of the adventitia as expected of a protective sheath. Note the overall mean value calculated using the Laplace equation. Axial stress is nearly equally distributed between the media and adventitia at mean arterial pressure for both groups, albeit at different values. Figure 4C,D shows associated values of material stiffness. Consistent with histological observations (Figure 3A), hypertension markedly redistributes material stiffness between layers. Despite maintaining an average value that is similar to normal, hypertension decreases circumferential stiffness in the media and increases it in the adventitia. Conversely, axial stiffness decreases more in the adventitia than the media, thus resulting in a lower average value than normal. These results are consistent with an increase in circumferentially oriented collagen fibers in hypertension (Table S3). Finally, Figures 4E and F illustrate the protective mechanical role of the adventitia in a normal aorta by simulating changes in wall stress for an instantaneous change in systolic pressure from normal (Sham systolic) to hypertensive (Ang II systolic) levels. Although the predicted biaxial stresses increase in the media and adventitia, the latter experiences greater increases circumferentially (80% increase) and axially (25% increase).

Figure 4.

Transmural distributions of biaxial stress and material stiffness for Sham (black) and 2-week angiotensin-infused (grey) mice. Predicted layer-specific distributions of circumferential and axial (A,B) stress and (C,D) material stiffness at group-specific in vivo axial stretches and mean arterial pressures within the medial (M) and adventitial (A) layers. Mean circumferential stress computed via the Laplace equation (in A, dashed line; Eq. S.4.1) and the integral means of material stiffness (in C, D, dashed lines) are shown for comparison. (E) Circumferential and (F) axial stress distributions are shown for a simulated step-increase from Sham to Ang II systolic pressure; annotations show layer-specific percent changes in biaxial stress. Normalized radius ranges from 0 (inner wall) to 1 (outer wall), and vertical solid lines (light-grey) denote the predicted medial-adventitial border (0.68 for Sham and 0.43 for Ang II, similar to that in Figure 3B).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that early aortic responses to angiotensin-induced hypertension are strongly biaxial, affecting circumferential and especially axial wall properties, and markedly different between the media and adventitia. Moreover, these early responses appear to be nearly complete by 2 weeks and to persist over 4 weeks. A consequence of these differential responses is a dramatically reduced ability of the aorta to store elastic energy during systole (Figure 1F), which compromises its primary mechanical function to sustain blood flow during diastole.1,3,14

Loss of energy storage is due largely to a marked reduction in distensibility and extensibility (cf. Figure 1E,F), that is, adverse biaxial remodeling. Because of circumferential–axial coupling (i.e., both stresses depend on circumferential and axial stretches; Online Data Supplement), the marked decrease in axial stretch helps to protect circumferentially oriented medial smooth muscle cells from excessive stresses in hypertension (cf. Figure 2C,D). This reduced axial stretch also helps maintain overall circumferential material stiffness near its normal value (Figure 2E), which is mechanobiologically favorable since intramural cells appear to seek to establish and maintain wall properties near preferred values.15–17 These observations emphasize the importance of axial wall mechanics, which are seldom considered but play essential roles in the mechanobiology18 and structural integrity19 of the arterial wall and even pulse wave propagation.20 Indeed, altered axial mechanics can be among the earliest adaptations to hemodynamic changes.21,22 Nevertheless, the axial response ultimately appears maladaptive in the present case for it also contributes to a significant loss of elastic energy storage capability (Figure 1F) and presumably an inability of the aorta to augment diastolic blood flow optimally.

Another indicator of maladaptive remodeling is the reduction in wall stress well below normal (Figures 1C,D and 2C,D). Arteries tend to adapt mechanically in many cases of altered hemodynamics and disease by maintaining circumferential stress near a homeostatic value8,23,24. It is straightforward to show that “optimal” mechano-adaptations to altered blood flow and pressure result in changes in luminal radius a and total wall thickness h according to particular rules25: α → ε1/3α0, and h → γε1/3α0, where ε denotes the fold-increase in flow and ε the fold-increase in pressure, with subscript o denoting an original (homeostatic) value. With mean arterial pressures of 144 and 106 mmHg at 2 weeks in the angiotensin-infused and Sham mice, respectively, γ=1.36. Although not measured in the descending thoracic aorta, changes in flow are typically small in hypertension (i.e., ε~1.0). Indeed our finding that values of luminal radius are similar across the two groups (Table S1) suggests little change in flow in this model of hypertension, consistent with regulation of wall shear stress 26,23. The measured increase in wall thickness at 2 weeks (h/ho=102 μm/39 μm=2.62)is thus well in excess of the mechano-adaptive target of γ=1.36, which contributes to a significant decrease in biaxial stress (Figure 1C,D) and mechanical functionality (Figure 1E,F). Similar maladaptation (h/ho=2.79) is found after 4 weeks of hypertension. Although such an overcompensation could resolve over a longer period (low wall stresses typically promote atrophy,23) with a possible approaching of the homeostatic target,27,28 the early and persistent responses at 2 and 4 weeks are mechanically maladaptive due primarily to excessive collagen deposition in the adventitia.

The present study is the first to delineate biaxial wall stresses in the media and adventitia for an Ang II infusion model. Circumferential stresses are normally higher in the media than in the adventitia (Sham; Figure 4A), consistent with the goal of storing energy in elastic fibers during systolic distensions. The highly nonlinear behavior of the normal collagen-rich adventitia allows stresses to increase more in this layer in response to a sudden increase in pressure, however, which enables it to protect medial smooth muscle cells and elastic fibers from excessive stresses (Figure 4E,F). It seems that angiotensin II induced hypertension increases adventitial stress more than medial stress, consistent with greater remodeling of the former (Figure 3A). Importantly, adventitial remodeling is also more dramatic in other models of induced hypertension, including DOCA-salt and aortic banding.12,28,29 There is, therefore, a pressing need to account for differential stresses in these two layers and associated differences in smooth muscle cell and fibroblast mechanobiology,12,30 as well as possible paracrine signaling among these cells.31 Yet, consistent with aforementioned indicators of maladaptation, adventitial thickening is far greater than needed to restore adventitial and medial stresses to normal values (Figure 4A,B). This overcompensation suggests either a dysfunctional mechanosensing that leads to a fibrotic response or additional contributors to the exuberant collagen production.32 Among other factors, inflammation is important in multiple rodent models that exhibit adventitial thickening, including induced hypertension,12,33,34 and central artery aging.35,36 Indeed, the adventitia is now recognized to be a biologically complex layer that is involved in many cases of arterial remodeling and injury response.37,38 It not only contains resident fibroblasts that can differentiate into myofibroblasts, it is a source of progenitor and inflammatory cells.39 Both pressure-induced wall stresses (which can augment local production of Ang II as well as diverse cytokines and proteases)40,41 and exogenous Ang II which stimulates production of other pro-inflammatory molecules,42–44 can promote the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells. Genetic manipulation studies in mice demonstrate that macrophages and T-cells play particularly important roles in such cases.12,45 It is not surprising, therefore, that ex vivo models confirm that effects of pressure-induced stress and exogenous Ang II are synergistic in the production of matrix,46 consistent with in vivo studies.34 Cell culture and ex vivo studies similarly show that increased mechanical loading,47 and exogenous Ang II increase the production of proteases, independent of inflammatory cells.43 Deposition and degradation are fundamental to overall extracellular matrix remodeling.

We recently reported complementary data wherein mouse aortic fibroblasts were subjected to cyclic stretching, IL-17a, or Ang II, and different combinations thereof.12 Cyclic stretching increased the production of collagen 1a1, 3a1, and 5a1 in a stress-dependent fashion whereas IL-17a and Ang II independently increased collagen production. Combined with results of Figure 4, these data support the hypothesis that a combination of preferential pressure-induced mechanical stresses and angiotensin-induced inflammation led to the exuberant and rapid production of matrix in the adventitia (Figure 3). Similar adventitial collagen deposition has been reported in aortic banding,33 DOCA-salt hypertension,12 and a model of hypertension associated with increased vascular oxidative stress. It is therefore likely that our findings of maladaptive wall mechanics are not specific to Ang II, but instead are relevant to many models of hypertension.

PERSPECTIVES

The present experimental findings and computational results suggest that hypertension preferentially increases circumferential stress within the adventitial layer, the primary site of matrix accumulation and remodeling. Because the overall aortic response is mechanically maladaptive, the over-exuberant production of adventitial collagen nevertheless appears to result more from an inflammatory response, hence reinforcing the need to control inflammation, not just blood pressure. Finally, although most clinical assessments of arterial stiffening focus on intimal-medial thickening, our results suggest a need to control the highly active and important adventitia that can adversely limit elastic energy storage by an otherwise competent medial layer of the aortic wall.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What is new?

This is the first analysis of how aortic axial and circumferential mechanical properties are altered differentially in the media and adventitia in hypertension.

This analysis reveals that hypertension causes a striking decline in the ability of the aorta to store energy, which compromises its primary mechanical function.

The exuberant deposition of adventitial collagen in hypertension is maladaptive and exceeds that necessary to normalize wall stress.

What is relevant?

These changes in aortic compliance have striking implications for systemic perfusion.

Loss of energy storage reduces the ability of the aorta to maintain diastolic flow while the increase in biaxial stiffness enhances systolic forward flow.

Clinically, these perturbations of pulse wave contour are associated with untoward outcomes.

Biaxial and bilayered analyses of wall mechanics provides novel insight into vascular function having basic and translational implications.

Summary.

Our analysis of biaxial wall mechanics reveals that hypertension not only leads to increased structural stiffness of the aorta, but also profoundly reduces the ability of the aorta to store elastic energy. This is largely due to dramatic, maladaptive remodeling of the adventitia. These alterations of aortic compliance likely contribute to end organ damage and untoward clinical outcomes. Efforts to modulate adventitial remodeling will likely have therapeutic benefit.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Yale Pathology Tissue Services for preparing, sectioning, and staining the histological sections.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the NIH (R01 HL105294 and HL390006, VITA contract HHSN268201400010C and the American Heart Association Strategically Focused Research Network Grant to DGH, R01 HL105297 to JDH) and NSF (CMMI-1161423 to JDH).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.O’Rourke MF, Hashimoto J. Mechanical factors in arterial aging: a clinical perspective. J. Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakatta EG, Wang M, Najjar SS. Arterial aging and subclinical arterial disease are fundamentally intertwined at macroscopic and molecular levels. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:583–604. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.008. Table of Contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safar ME. Arterial aging--hemodynamic changes and therapeutic options. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:442–449. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avolio AP, Van Bortel LM, Boutouyrie P, Cockcroft JR, McEniery CM, Protogerou AD, Roman MJ, Safar ME, Segers P, Smulyan H. Role of pulse pressure amplification in arterial hypertension: Experts’ opinion and review of the data. Hypertension. 2009;54:375–383. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.134379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, Pannier B, Vlachopoulos C, Wilkinson I, Struijker-Boudier H. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: Methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2588–2605. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolinsky H. Comparison of medial growth of human thoracic and abdominal aortas. Circ Res. 1970;27:531–538. doi: 10.1161/01.res.27.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu C, Zarins CK, Bassiouny HS, Briggs WH, Reardon C, Glagov S. Differential transmural distribution of gene expression for collagen types I and III proximal to aortic coarctation in the rabbit. J Vasc Res. 2000;37:170–182. doi: 10.1159/000025728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayashi K, Naiki T. Adaptation and remodeling of vascular wall; biomechanical response to hypertension. J. Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2009;2:3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogt M, Kühn A, Baumgartner D, Baumgartner C, Busch R, Kostolny M, Hess J. Impaired elastic properties of the ascending aorta in newborns before and early after successful coarctation repair: Proof of a systemic vascular disease of the prestenotic arteries? Circulation. 2005;111:3269–3273. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.529792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMaster WG, Kirabo A, Madhur MS, Harrison DG. Inflammation, Immunity, and Hypertensive End-Organ Damage. Circ Res. 2015;116:1022–1033. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McEniery CM, Wilkinson IB. Large artery stiffness and inflammation. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:507–509. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Trott DW, Saleh MA, Xiao L, Madhur MS, Chen W, Harrison DG. Inflammation and mechanical stretch promote aortic stiffening in hypertension through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Circ. Res. 2014;114:616–625. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellini C, Ferruzzi J, Roccabianca S, Di Martino ES, Humphrey JD. A microstructurally motivated model of arterial wall mechanics with mechanobiological implications. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:488–502. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0928-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferruzzi J, Bersi MR, Uman S, Yanagisawa H, Humphrey JD. Decreased Elastic Energy Storage, Not Increased Material Stiffness, Characterizes Central Artery Dysfunction in Fibulin-5 Deficiency Independent of Sex. J Biomech Eng. 2015;137:031007. doi: 10.1115/1.4029431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shadwick RE. Mechanical design in arteries. J Exp Biol. 1999;202(Pt 23):3305–3313. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.23.3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bersi MR, Ferruzzi J, Eberth JF, Gleason RL, Humphrey JD. Consistent biomechanical phenotyping of common carotid arteries from seven genetic, pharmacological, and surgical mouse models. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:1207–1223. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-0988-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagenseil JE, Mecham RP. Vascular extracellular matrix and arterial mechanics. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:957–989. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dajnowiec D, Sabatini PJB, Van Rossum TC, Lam JTK, Zhang M, Kapus A, Langille BL. Force-induced polarized mitosis of endothelial and smooth muscle cells in arterial remodeling. Hypertension. 2007;50:255–260. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cyron CJ, Humphrey JD. Preferred fiber orientations in healthy arteries and veins understood from netting analysis. Math Mech Solids. 2014:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demiray H. Wave propagation through a viscous fluid contained in a prestressed thin elastic tube. Int J Eng Sci. 1992;30:1607–1620. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson ZS, Gotlieb AI, Langille BL. Wall tissue remodeling regulates longitudinal tension in arteries. Circ Res. 2002;90:918–925. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000016481.87703.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humphrey JD, Eberth JF, Dye WW, Gleason RL. Fundamental role of axial stress in compensatory adaptations by arteries. J Biomech. 2009;42:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humphrey JD. Cardiovascular Solid Mechanics: Cells, Tissues and Organs. Springer; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolinsky H, Glagov S. A lamellar unit of aortic medial structure and function in mammals. Circ Res. 1967;20:99–111. doi: 10.1161/01.res.20.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humphrey JD. Mechanisms of arterial remodeling in hypertension: coupled roles of wall shear and intramural stress. Hypertension. 2008;52:195–200. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dajnowiec D, Langille BL. Arterial adaptations to chronic changes in haemodynamic function: coupling vasomotor tone to structural remodelling. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;113:15–23. doi: 10.1042/CS20060337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolinsky H. Long-term effects of hypertension on the rat aortic wall and their relation to concurrent aging changes. Morphological and chemical studies. Circ Res. 1972;30:301–309. doi: 10.1161/01.res.30.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eberth JF, Popovic N, Gresham VC, Wilson E, Humphrey JD. Time course of carotid artery growth and remodeling in response to altered pulsatility. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1875–1883. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00872.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuang SQ, Geng L, Prakash SK, Cao JM, Guo S, Villamizar C, Kwartler CS, Peters AM, Brasier AR, Milewicz DM. Aortic remodeling after transverse aortic constriction in mice is attenuated with AT1 receptor blockade. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2172–2179. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lacolley P, Regnault V, Nicoletti A, Li Z, Michel JB. The vascular smooth muscle cell in arterial pathology: A cell that can take on multiple roles. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:194–204. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goel SA, Guo LW, Shi XD, Kundi R, Sovinski G, Seedial S, Liu B, Kent KC. Preferential secretion of collagen type 3 versus type 1 from adventitial fibroblasts stimulated by TGF-b/Smad3-treated medial smooth muscle cells. Cell Signal. 2013;25:955–960. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Humphrey JD, Dufresne ER, Schwartz MA. Mechanotransduction and extracellular matrix homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014:1–11. doi: 10.1038/nrm3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eberth JF, Gresham VC, Reddy AK, Popovic N, Wilson E, Humphrey JD. Importance of pulsatility in hypertensive carotid artery growth and remodeling. J Hypertens. 2009;27:2010–21. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832e8dc8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Capers Q, Alexander RW, Lou P, De Leon H, Wilcox JN, Ishizaka N, Howard AB, Taylor WR. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in aortic tissues of hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1997;30:1397–1402. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleenor BS, Marshall KD, Durrant JR, Lesniewski LA, Seals DR. Arterial stiffening with ageing is associated with transforming growth factor-β1-related changes in adventitial collagen: reversal by aerobic exercise. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 20):3971–3982. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.194753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesniewski LA, Durrant JR, Connell ML, Henson GD, Black AD, Donato AJ, Seals DR. Aerobic exercise reverses arterial inflammation with aging in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1025–1032. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01276.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maiellaro K, Taylor WR. The role of the adventitia in vascular inflammation. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:640–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gingras M, Farand P, Safar ME, Plante GE. Adventitia: the vital wall of conduit arteries. J Am Soc. Hypertens. 2009;3:166–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Majesky MW, Dong XR, Hoglund V, Mahoney WM, Daum G. The adventitia: A dynamic interface containing resident progenitor cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1530–1539. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Q, Muragaki Y, Hatamura I, Ueno H, Ooshima A. Stretch-induced collagen synthesis in cultured smooth muscle cells from rabbit aortic media and a possible involvement of angiotensin II and transforming growth factor-beta. J Vasc Res. 1998;35:93–103. doi: 10.1159/000025570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanley AG, Patel H, Knight AL, Williams B. Mechanical strain-induced human vascular matrix synthesis: the role of angiotensin II. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1:32–35. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2000.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ford CM, Li S, Pickering JG. Angiotensin II stimulates collagen synthesis in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Involvement of the AT(1) receptor, transforming growth factor-beta, and tyrosine phosphorylation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1843–1851. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.8.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Browatzki M, Larsen D, Pfeiffer CAH, Gehrke SG, Schmidt J, Kranzhofer A, Katus HA, Kranzhofer R. Angiotensin II stimulates matrix metalloproteinase secretion in human vascular smooth muscle cells via nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein 1 in a redox-sensitive manner. J Vasc Res. 2005;42:415–423. doi: 10.1159/000087451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tieu BC, Ju X, Lee C, Sun H, Lejeune W, Recinos A, Brasier AR, Tilton RG. Aortic adventitial fibroblasts participate in angiotensin-induced vascular wall inflammation and remodeling. J Vasc Res. 2011;48:261–272. doi: 10.1159/000320358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, McCann LA, Weyand C, Gordon FJ, Harrison DG. Central and peripheral mechanisms of T-lymphocyte activation and vascular inflammation produced by angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;107:263–270. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bardy N, Merval R, Benessiano J, Samuel JL, Tedgui A. Pressure and angiotensin II synergistically induce aortic fibronectin expression in organ culture model of rabbit aorta. Evidence for a pressure-induced tissue renin-angiotensin system. Circ Res. 1996;79:70–78. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lehoux S, Lemarié CA, Esposito B, Lijnen HR, Tedgui A. Pressure-Induced Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Contributes to Early Hypertensive Remodeling. Circulation. 2004;109:1041–1047. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115521.95662.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.