Summary

Divergence of developmental mechanisms within populations may lead to hybrid developmental failure, and may be a factor driving speciation in angiosperms.

We investigate patterns of endosperm and embryo development in Mimulus guttatus and the closely related, serpentine endemic M. nudatus, and compare them to those of reciprocal hybrid seed. We address whether disruption in hybrid seed development is the primary source of reproductive isolation between these sympatric taxa.

M. guttatus and M. nudatus differ in the pattern and timing of endosperm and embryo development. Some hybrid seed exhibit early disruption of endosperm development and are completely inviable, while others develop relatively normally at first, but later exhibit impaired endosperm proliferation and low germination success. These developmental patterns are reflected in mature hybrid seed, which are either small and flat (indicating little to no endosperm), or shriveled (indicating reduced endosperm volume). Hybrid seed inviability forms a potent reproductive barrier between M. guttatus and M. nudatus.

We shed light on the extent of developmental variation between closely related species within the M. guttatus species complex, an important ecological model system, and provide a partial mechanism for the hybrid barrier between M. guttatus and M. nudatus.

Keywords: endosperm, hybrid inviability, Mimulus guttatus (monkeyflower), pollen–pistil interactions, postzygotic isolation, seed development

Introduction

The process of gradual evolution imposes a fundamental constraint on organismal development – each successful evolutionary shift, large or small, must allow for viable offspring (Smith et al., 1985; Bonner, 1988; Beldade et al., 2002). This constraint is perhaps best visualized by the disruption of development frequently observed when two divergent populations hybridize, when both lineages themselves continue to produce viable offspring. In nature, these incompatibilities can keep species distinct by preventing gene flow. In the laboratory, we can make use of incompatibilities witnessed in hybrid offspring to investigate how development has evolved in isolation and how evolutionary constraint may shape developmental trajectories. Here we describe differences in seed development between a recently diverged species pair – Mimulus guttatus and M. nudatus. We further show that postzygotic failures of development are largely responsible for incompatibility in experimental crosses between this sympatric species pair. We propose that the M. guttatus sp. complex may serve as a new model to understand the evolution of development and developmental abnormalities in hybrid plants.

Development in multicellular organisms requires coordination across numerous cell lineages or types. The process of double fertilization in angiosperms is an extreme example as growth must be coordinated across two developing entities: the diploid embryo and the triploid, sexually-derived nutritive tissue called endosperm. Together these distinct entities comprise the angiosperm seed, a highly successful mode of reproduction employed by most vascular plants (Linkies et al., 2010). While the developmental origins of embryo and endosperm have been known for over a century (Nawaschin, 1898; Guignard, 1899, Friedman, 2001), advances in genomic sequencing and gene expression analysis have only lately revealed the basic genetic details of embryogenesis and the development of endosperm (Girke et al., 2000; Casson et al., 2005; Hsieh et al., 2011). Interactions between the developing endosperm and embryo are often responsible for hybrid seed failure (Brink & Cooper, 1947; Haig & Westoby, 1991), emphasizing the critical and sensitive role played by endosperm in promoting successful reproduction.

Despite the essential importance of endosperm, research on endosperm development has been largely restricted to the model system, Arabidopsis thaliana, and its close relatives (Scott et al., 1998; Josefsson et al., 2006; Burkart-Waco et al., 2013), even though several developmental and evolutionary peculiarities of the biology of A. thaliana may limit the applicability of research findings across the broader diversity of plants. For example, A. thaliana undergoes nuclear endosperm development, in which initial rounds of karyokinesis are not accompanied by cytokinesis. While this mode of development is shared by many groups of flowering plants, two other major modes of endosperm development, helobial and cellular, are also distributed widely among angiosperms (Bharathan, 1999). Indeed, ab initio cellular development, wherein karyokinesis is always followed by cytokinesis, is thought to be the ancestral state of endosperm development (Floyd & Friedman, 2000) and is characteristic of a few other model plant systems including Solanum (Lester & Kang, 1998) and Mimulus (Guilford & Fisk, 1951; Arekal, 1965). More broadly, the extent to which basic features of embryo and endosperm development may vary among closely related taxa remains an open question and one which can only be addressed by examining and comparing development between closely related species in other taxa.

Another factor limiting the applicability of research on endosperm in A. thaliana is that it is predominantly self-fertilizing. Self-fertilization limits a major evolutionary pressure on seed development by relaxing conflicts between maternal and paternal genomes over resource provisioning to developing seeds. Relying on A. thaliana as a model of endosperm development and failure potentially limits our ability to fully understand the evolutionary mechanisms shaping plant development. It also limits our ability to investigate the role mating system may play in the evolution of endosperm, a research topic that continues to garner interest (Brandvain & Haig, 2005; Friedman et al., 2008; Köhler et al., 2012; Haig, 2013). Moreover, while seed inviability may be a potent hybrid barrier and potential driver of plant speciation (Tiffin et al., 2001), nearly all research on hybrid seed lethality in A. thaliana is focused on lethality resulting from interploidy crosses (Scott et al., 1998; Köhler et al., 2003), potentially limiting its application to divergence among diploid taxa.

To extend our understanding of seed development and seed failure beyond A. thaliana we turn to the Mimulus guttatus species complex. The genus Mimulus (Phrymaeceae) has emerged as a model system in which to investigate the genetic basis of ecological adaptation and the role of mating system evolution in promoting species divergence (Lowry & Willis, 2010; Martin & Willis, 2010; Wright et al., 2013). Knowledge of the pattern of seed development in this increasingly important genus is limited to two papers published over 50 yr ago on the diploid species Mimulus ringens (Arekal, 1965) and the cultivar M. tigrinus (Guilford & Fisk, 1951), likely a hybrid between M. luteus and the Chilean species M. cupreus (Cooley & Willis, 2009). Seed inviability is a common outcome of crosses between members of the M. guttatus species complex, a highly diverse group of populations, ecotypes and species distributed across western North America (Vickery, 1966, 1978). M. guttatus, also a diploid, is the most geographically widespread and genetically diverse member of the complex (Wu et al., 2007; Oneal et al., 2014), and exhibits varying interfertility with other members of the complex (Vickery, 1978; Wu et al., 2007), however, hybridization between closely related species within the complex is frequently accompanied by varying levels of hybrid seed failure (Vickery, 1978).

While the diploid, edaphic endemic M. nudatus is likely recently derived from a M. guttatus-like ancestor (Oneal et al., 2014), this species pair exhibits the highest level of sequence divergence of any within the M. guttatus sp. complex (~3% genomic sequence divergence; L. Flagel, pers. comm.). Populations of serpentine-adapted M. guttatus overlap with those of M. nudatus at multiple serpentine soil sites in the California Coastal Ranges. Despite their close physical proximity and recent divergence, M. guttatus and M. nudatus rarely form hybrids. The absence of naturally occurring hybrids is all the more striking given that M. guttatus and M. nudatus also overlap substantially in flowering time and share multiple pollinators (Gardner & Macnair, 2000; J. Selby, unpublished data). Gardner & Macnair (2000) found that controlled field and glasshouse crosses recovered very few normal seed but instead produced seed that were shriveled and comparatively flattened, and that failed to germinate (Gardner, 2000). Together, these findings raise the possibility that the recent divergence between M. guttatus and M. nudatus has been accompanied by a shift in the pattern of embryo and endosperm development, that in turn contributes to their reproductive isolation.

Here we investigate early embryo and endosperm development within M. guttatus, a species which has emerged as an important model system in ecological and evolutionary genetics, and contrast it with development of M. nudatus, a serpentine soil endemic. Furthermore, we investigate whether seed inviability is the primary reproductive barrier between M. guttatus and M. nudatus (Gardner & Macnair, 2000). We first address whether interspecific pollen can successfully germinate and penetrate the ovary when either species serves as pollen donor. We then compare the development of hybrid seed with that of the normal pattern of development in both species, and attempt to determine at what point in development hybrid seed failure arises. Finally, we connect the development of hybrid seed to the phenotypes of mature seed collected from hybrid fruits and confirm that hybrid seed are largely inviable.

We find that M. guttatus and M. nudatus exhibit divergent trajectories of early embryo and endosperm development, and suggest that early disruption of endosperm development and a later failure of endosperm proliferation are the major causes of hybrid seed failure and comprise major isolating mechanism between these species. Our work is the first to examine the pattern of seed development in M. guttatus and the first to examine the extent to which early seed development varies between M. guttatus and a closely related species, M. nudatus. Finally, since seed lethality is a common outcome of hybridization between multiple members of the M. guttatus sp. complex (Vickery, 1978), our results suggest that M. guttatus, which is already emerging as a model system in ecological genetics, could also provide valuable insight into the genetic basis of fundamental developmental processes and their importance for speciation in this group.

Materials and Methods

Growth and pollination of Mimulus spp

M. guttatus is the most widespread member of the M. guttatus sp. complex and is adapted to a variety of soil conditions (Lowry et al., 2009, Wright et al., 2014), including serpentine soil. Serpentine-adapted M. guttatus and M. nudatus individuals were collected in 2008 from sympatric populations located at two serpentine soil sites in the Donald and Sylvia McLaughlin Natural Reserve in Lake County, California, and brought back to the Duke Research Glasshouses where they were self-fertilized for at least 2 generations to produce inbred lines. We use one inbred line per population in this study (see Table 1 for a list of accessions), and two populations each of serpentine-adapted M. guttatus and M. nudatus. The lines CSS4 (M. guttatus), CSH10 (M. nudatus) and DHRo22 (M. nudatus) were inbred for 2 generations. Most data generated using the M. guttatus accession DHR14 was acquired from a line that was inbred for 3 generations; however, we were unable to complete the study with these individuals, as they died prematurely in the glasshouse; we completed the study with a 6-generation inbred line of DHR14. All plants used in this study were grown from seeds that were first cold-stratified for 10 d at 4°C, then placed in a glasshouse with 30% relative humidity and a light/temperature regime of 18-h days at 21°C and 6-h nights at 16°C. Following germination, individuals were placed in 2.5-inch square pots where they were maintained for the duration of the study.

Table 1.

Sampling localities and accession names for sympatric serpentine-adapted Mimulus guttatus and M. nudatus populations.

| Accessions | Latitude (N) | Longitude (W) |

|---|---|---|

| M. guttatus/M. nudatus | ||

| CSS4/CSH10 | 38.861 | −122.415 |

| DHR14/DHRo22 | 38.859 | −122.411 |

M. guttatus and M. nudatus are both self-compatible and self-fertilize regularly in the field, although M. nudatus is primarily outcrossing (Ritland & Ritland, 1989). Both species produce hermaphroditic, chasmogamous flowers with four anthers, and invest similarly in male (e.g., stamens) vs. female (e.g., pistil) structures, however, M. nudatus flowers are smaller than those of M. guttatus and produce proportionately fewer ovules and pollen grains (~20% as many ovules and pollen grains) (Ritland & Ritland, 1989). To account for this imbalance in pollen production, we used 4 new flowers (i.e., 16 anthers) whenever M. nudatus served as pollen donor to M. guttatus. All crosses and self-pollinations were performed in the morning and using the same protocol. Pollen recipients were emasculated 1–3 d prior. The day of pollination, mature pollen was obtained by tapping the stamens of a fresh flower onto a glass slide, and then collected with a pair of sterile forceps and placed directly on the open, receptive stigma of the pollen recipient.

Pollen tube growth assay

Pollinated styles and ovaries were fixed in Farmer’s solution (3:1 95% EtOH:acetic acid) for at least 12 h, then softened in 8N NaOH for 24 h before being left to stain overnight in a decolorized aniline blue solution (0.1% in 0.1 M K3PO4) (Kearns & Inouye, 1993) that differentially stains pollen tube walls and callose plugs. Stained styles and ovaries were mounted on a slide and examined with a Zeiss Axio Observer equipped with a fluorescent lamp. We performed 10 reciprocal crosses for each sympatric population pair (CSS4 × CSH10; CSH10 × CSS4; DHR14 × DHRo22; DHRo22 × DHR14) and then collected the styles and ovaries after 24 h, a period sufficient to allow pollen from self-pollinations to penetrate the ovary in each population (E. Oneal, pers. obs.). For each pollination event we noted whether the pollen had successfully germinated and whether pollen tubes were observed within the ovary.

Seed set and viability

We performed 8 reciprocal crosses for each sympatric population pair of M. guttatus/M. nudatus and 8 self-pollinations of each accession, collected the mature fruits and counted the resulting seeds under a dissection scope. Throughout, we use the term ‘self-fertilization’ to describe fertilizations performed with pollen from the same accession (i.e., inbred line), but not necessarily the same individual plant. Normal M. guttatus and M. nudatus seeds are round, fully filled and unbroken with a light brown, reticulate coat (Searcy & Macnair, 1990). We counted the number of seed found in self-fertilized and hybrid fruits and categorized them by outward morphology. We also took pictures of mature seed using a Zeiss Lumar.V12 stereoscope outfitted with a AxioCam MRM firewire monocrome camera and measured the length of up to 25 seed morphs for each self-fertilized accession and reciprocal cross. We sowed round, shriveled, and flat self-fertilized and hybrid seeds (see below) to compare germination rates. All seeds were cold-stratified, placed in the Duke Glasshouses as above, and examined over the course of 14 d for signs of germination.

Seed development

Fruits resulting from interspecific crosses consistently contained seeds that fell into one of three different morphological categories (see below). We used microscopy to connect early embryo and endosperm development with the seed morphologies found in mature fruits and to compare the growth, and embryo and endosperm development, of self-fertilized seeds to those of reciprocal, sympatric hybrid seed. Self-fertilized and hybrid fruits were collected from 1 to 5 d after pollination (DAP), and then at 9 DAP. Emasculated, but unpollinated ovaries were collected at 1–2 DAP.

We first examined whole-mounted fruits to get an initial sense of the pattern of embryo and endosperm development in self-fertilized and hybrid seeds from 1 to 5 DAP. Plant material was fixed in a solution of 9:1 EtOH:acetic acid for at least 2 h and up to 48 h, then washed twice in 90% EtOH for a minimum of 30 min per wash. Tissue was subsequently cleared in Hoyer’s solution (70% chloral hydrate, 4% glycerol and 5% gum arabic) for at least 12 h. A final dissection of the fruit in Hoyer’s solution allowed unfertilized ovules and immature seed to be separated from the ovary or fruit and then mounted on a glass slide. We collected 3 replicate fruits per DAP for each hybrid cross or self-fertilization, as well as 3 unpollinated ovaries from each accession. Mounted specimens were observed with a Zeiss Axioskop2 or Zeiss Axio Imager using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. We took pictures of up to 10 ovules per unfertilized ovary, 10 immature seed per self-fertilized fruit, and up to 10 of each seed morph (see below) per hybrid fruit, and used these images to measure the size of seed morphs.

We used laser confocal microscopy (LCM) to better visualize the pattern of early seed failure observed in whole mounted fruits (see below). Tissue was stained with propidium iodide according to Running (2007). Plant material was fixed under a vacuum with a solution containing 3.7% (v/v) formaldehyde, 5% (v/v) propionic acid, 70% (v/v) ethanol, and then subjected to a graded ethanol series to remove residual chorophyll. Tissue was then subjected to a decreasing ethanol series, stained with propidium iodide dissolved in 0.1M L-arginine (pH 12.4) for 2–4 d (stain time depended upon the size of the plant material), rinsed for 2–4 d in a 0.1M L-arginine buffer (pH 8.0), subjected to another graded ethanol series and then a final graded xylene series. Unfertilized ovules and immature seeds were dissected out and mounted in Cytoseal XYL. Images were acquired with a Zeiss 710 inverted scanning confocal microscope equipped with an argon laser. Some images (e.g., seed at 4–5 DAP) required the collection of extended z-stacks, which were assembled into composite 3-D images using the Zeiss Zen software.

We examined cross sections of self-fertilized and hybrid seeds collected at 9 DAP. Fruits were fixed under a vacuum with a solution containing 3.7% (v/v) formaldehyde, 50% (v/v) EtOH, and 5% (v/v) glacial acetic acid, subjected to a graded ethanol series, then stained overnight in a 0.1% Eosin solution. Stained tissue was subjected to a graded xylene series and then infused with and mounted in paraplast parafin. Fruits were sliced with a microtome into 0.8 micron sections, stained with toluidine blue, and sealed with Cytoseal XYL for imaging. Slides were examined and photographed with a Zeiss Axio Imager outfitted with a QImaging MicroPublisher 5.0 MP color camera.

To determine whether hybrid seeds that appeared to fail early in the course of development (see below) represented fertilized seeds (as opposed to unfertilized, aborted ovules), we used three lines of evidence. First, we used a vanillin stain to test for seed coat development in immature hybrid seed. In A. thaliana, vanillin in acidic solution (i.e., a 1% (w/v) vanillin solution in 6 N HCL) turns red or brown upon binding to proanthocyanidins in the seed coat; a positive stain is indicative of seed coat development and suggests that fertilization has occurred (Deshpande et al., 1986; Roszak & Köhler, 2011). We tested for seed coat development in 5 DAP reciprocal hybrid seed, and unpollinated ovaries (negative control) collected 5 d after emasculation. Second, we measured the length, from micropylar to chalazal end, of hybrid seed and compared their growth trajectory to that of self-fertilized seed. Third, using our LCM images, we compared the width of the central cell of unfertilized ovules from a subset of our accessions (DHR14 and DHRo22) to the width of the putative primary endosperm cell of DHR14 × DHRo22 reciprocal hybrid seed that exhibited signs of arrest at 2 DAP. An increase in size of the putative primary endosperm cell over the central cell is suggestive of successful fertilization (Williams, 2009). Throughout, measurements of size were taken using ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012). All crosses are given with the female parent listed first (i.e., female × male). Unless accessions differed significantly (noted in the text), data are pooled across accessions for both M. guttatus and M. nudatus.

Data accessibility

Immature and mature seed sizes, seed set and proportions of mature seed types: Dryad submission: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.64dh3.

Results

Pollen germination and tube growth

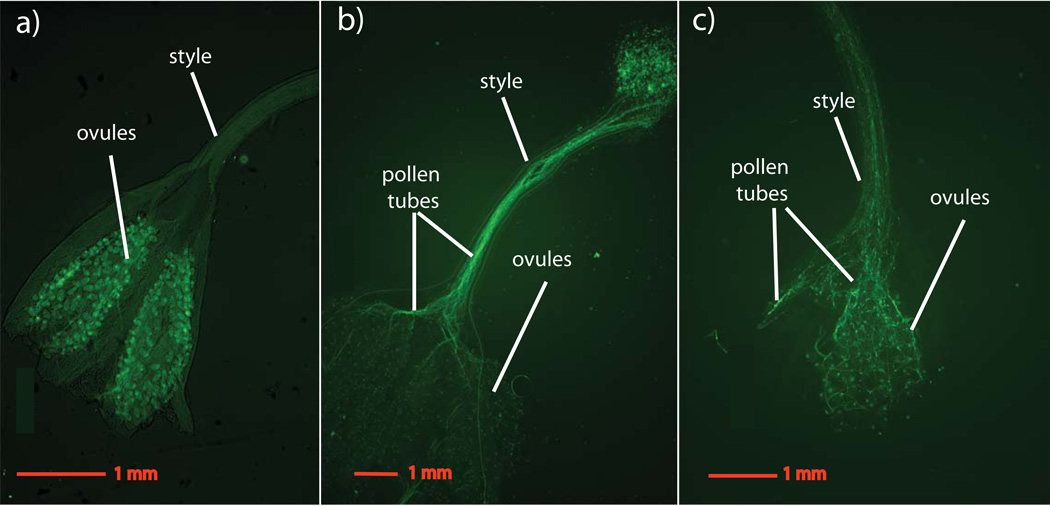

The inability of pollen from one species to successfully germinate, tunnel down the style, and penetrate the ovary of another species is a common prezygotic barrier to hybridization in flowering plants (Galen & Newport, 1988; Boavida et al., 2001; Campbell et al., 2003; Ramsey et al., 2003). In the M. guttatus sp. complex, pollen failure contributes to transmission distortion in crosses between M. guttatus and the closely related M. nasutus (Fishman et al., 2008). Gardner & Macnair (2000) reported that mature hybrid fruits contained few viable seeds but were filled with ‘dust’; however, they did not specify whether these particles were aborted seeds or unfertilized ovules. To clarify this, we investigated whether M. guttatus pollen could germinate and successfully penetrate the ovary of M. nudatus and vice versa, a precondition for fertilization. Interspecific pollen successfully germinated in all crosses and some pollen grains were nearly always successful in tunneling down to the ovary within 24-h (Table 2; Fig. 1). Identity of the female parent did not affect ability of interspecific pollen to penetrate the ovary (Wilcox rank-sum test, P > 0.1, data pooled across accessions). Furthermore, fruits resulting from M. guttatus × M. nudatus crosses exhibited an increase in size typical of that of fruits resulting from self-fertilization in either species (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Pollen germination and ovary penetration data for sympatric interspecific crosses between Mimulus guttatus and M. nudatus

| Cross | N | Styles with germinated pollen | Ovary penetration |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. guttatus × M. nudatus | |||

| CSS4 × CSH10 | 10 | 100% | 90% |

| DHR14 × DHRo22 | 10 | 100% | 80% |

| M. nudatus × M. guttatus | |||

| CSH10 × CSS4 | 10 | 100% | 90% |

| DHRo22 × DHR14 | 10 | 100% | 80% |

All crosses are female × male.

Fig. 1.

Images of pollen tubes penetrating the ovaries within 24-h of pollination for interspecific crosses of Mimulus guttatus and M. nudatus. Pollen tubes are stained with aniline blue and visualized with a Zeiss Axio Observer equipped with a fluorescent lamp and DAPI filter. (a) An unpollinated M. guttatus ovary. (b) Pollen tubes from M. nudatus pollen growing down a M. guttatus style. (c) Pollen tubes from M. guttatus pollen growing down a M. nudatus style.

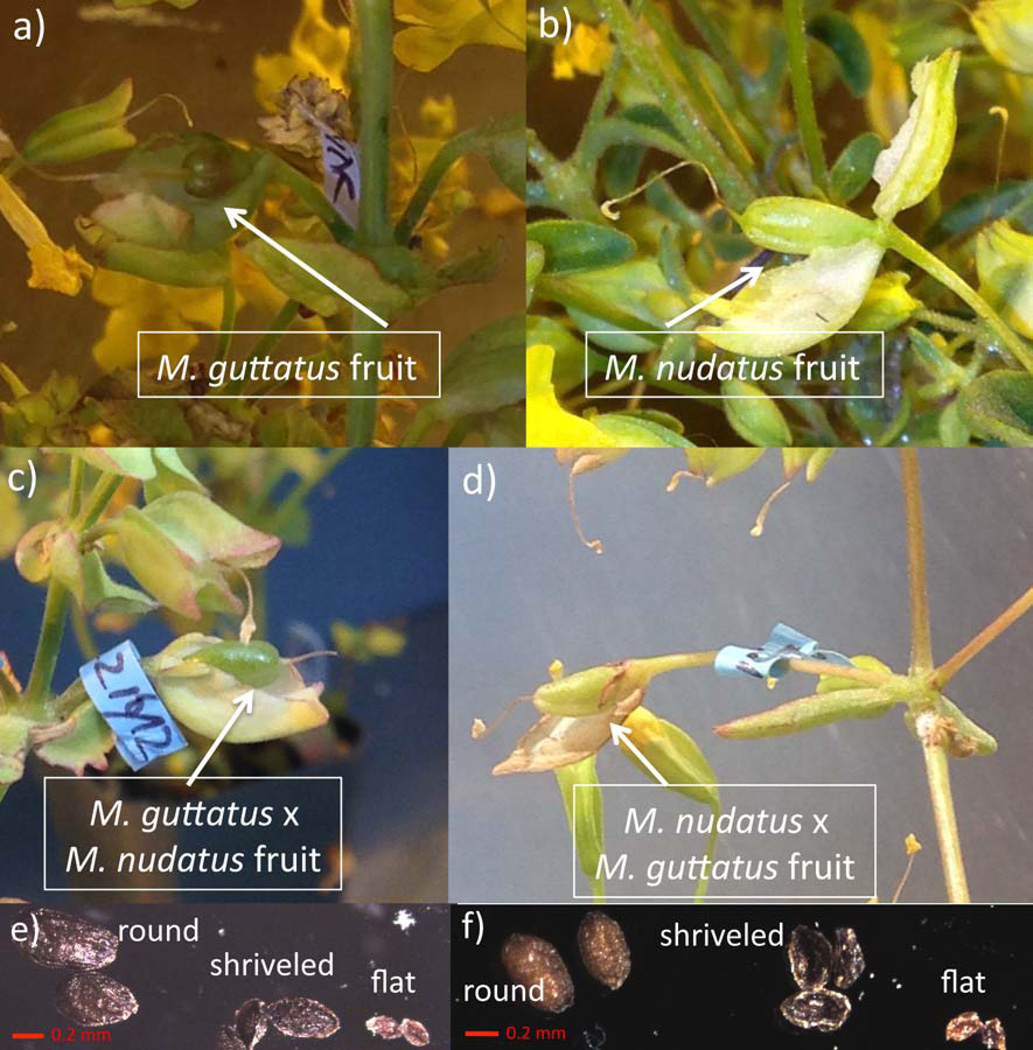

Fig. 2.

Developing fruits resulting from Mimulus guttatus and M. nudatus self-fertilizations and reciprocal crosses of M. guttatus × M. nudatus, as well as images of mature seed recovered from self-fertilized and hybrid fruits. All crosses are female × male. (a) M. guttatus self-fertilized fruit. (b) M. nudatus self-fertilized fruit. (c) M. guttatus × M. nudatus fruit. (d) M. nudatus × M. guttatus. (e) Round M. guttatus seed; shriveled and flat M. guttatus × M. nudatus seed. (f) Round M. nudatus seed; shriveled and flat M. nudatus × M. guttatus seed. All seed types appear to have developed a seed coat.

Seed set and germination success

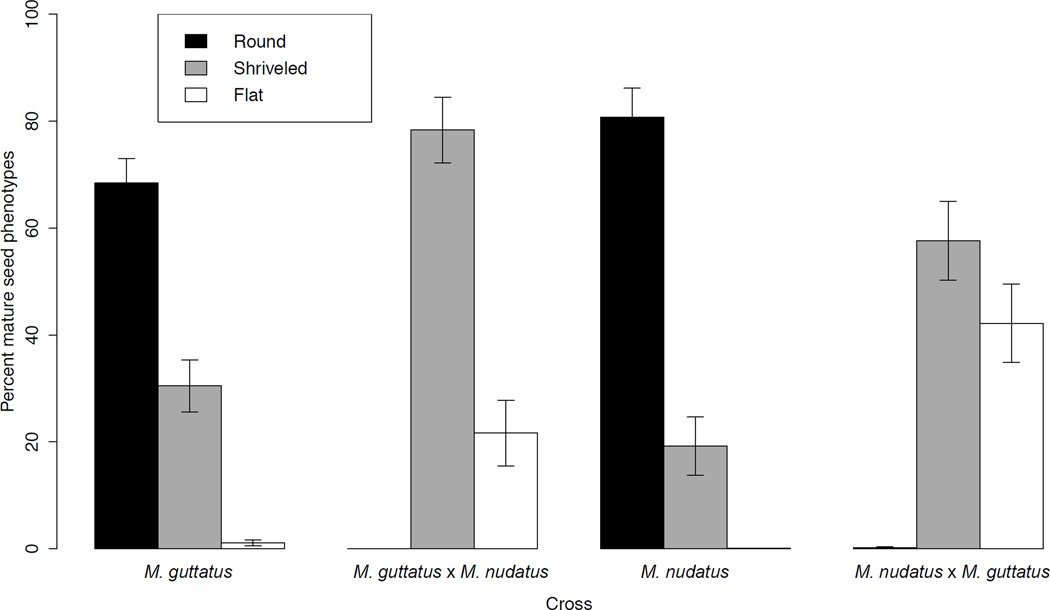

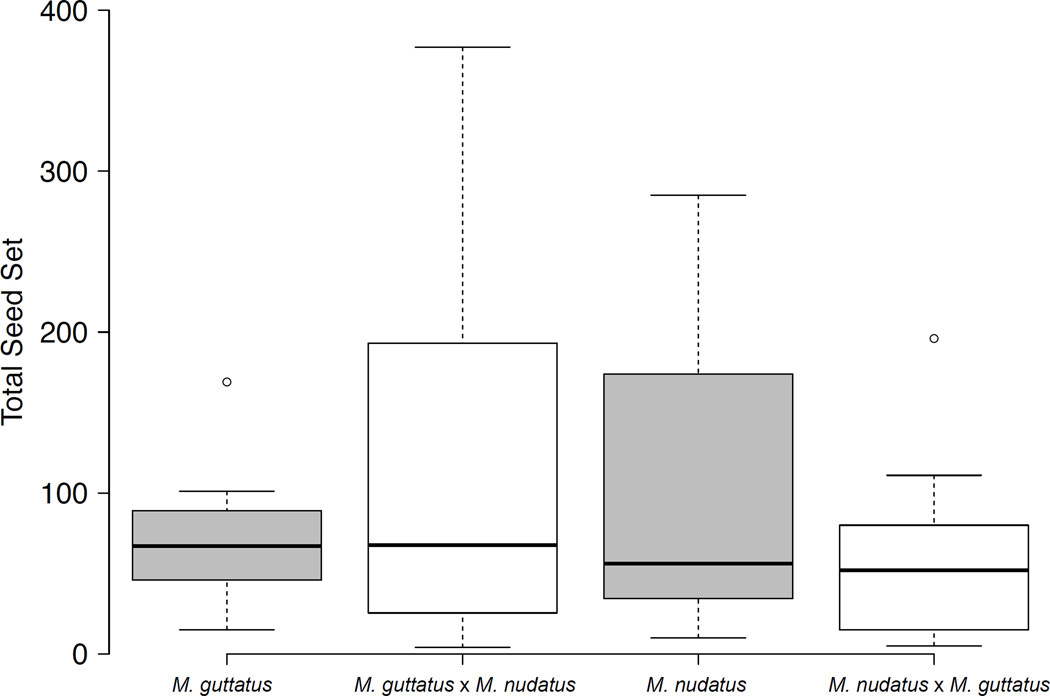

The majority of seeds from mature self-fertilized fruits of M. guttatus and M. nudatus were round and unbroken with a light brown, reticulate coat (Searcy & Macnair, 1990) (Figs 2, 3; termed ‘round’ in this work). Most self-fertilized fruits (30 of 32) also contained a minority of seeds which were shriveled and irregularly shaped (Fig. 3, termed ‘shriveled’), and were significantly smaller than the usual, round seed for both species (seed length: M. guttatus F1,98 = 58.647, P < 0.001; M. nudatus F1,95 = 108.14, P < 0.001). For both species, the size difference between round and shriveled seeds varied with accession (two-way ANOVA: M. guttatus F1,98 = 4.24, P = 0.002; M. nudatus F1,95 = 10.0, P = 0.042). In addition, several self-fertilized fruits (1 M. nudatus and 5 M. guttatus) contained a few seeds (16 total) that were considerably smaller than round, wild type seed and of a brown, flat appearance (Fig. 3, termed ‘flat’). The proportion of round seed was lower in M. guttatus than M. nudatus (M. guttatus: round mean = 69.3% ± 19.2 SD; M. nudatus: round mean = 80.7% ± 21.8 SD) (Fig. 3). Total seed set per fruit of self-fertilized accessions was 77.3 (± 40.9 SD) for M. guttatus and 84.0 (± 19.7 SD) for M. nudatus. (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Percentages of each mature seed phenotype resulting from self-fertilized Mimulus guttatus and M. nudatus self-fertilizations and reciprocal M. guttatus × M. nudatus crosses, pooled across accessions. Error bars, ± SE. All crosses are female × male.

Fig. 4.

Boxplot of seed set for self-fertilized and reciprocal crosses of Mimulus guttatus and M. nudatus, pooled across accessions. Horizontal lines represent the median, whiskers give maximum and minimum values, and circles represent outliers. For seed set by accession, see Supporting Information Fig. S1. All crosses are female × male.

Total seed set did not differ between self-fertilized fruits and fruits resulting from interspecific crosses (two-way ANOVA, P > 0.1 for M. guttatus or M. nudatus female) (Fig. 4; Supporting Information Fig. S1). Of 16 interspecific M. guttatus × M. nudatus crosses, only one produced one round seed. Instead, most hybrid seeds (mean = 76.8% ± 24.8 SD) were dark brown and shriveled (termed ‘shriveled’), resembling the shriveled seed present at lower frequency in self-fertilized fruits (Figs 2e, 3, S2). The remaining hybrid seeds (mean = 23.2% ± 24.8 SD) were very small, dark brown and flattened in appearance (Figs 2e, 3, S2) (termed ‘flat’). These latter seeds were clearly distinguishable from unfertilized ovules, which are smaller and light pink in color (due to a lack of seed coat) (Searcy & Macnair, 1990). We found one round seed with endosperm that had exploded through the seed coat in one of 16 mature fruits where M. nudatus was the female (CSH10 × CSS4). Otherwise, M. nudatus × M. guttatus crosses produced hybrid seed that were either shriveled or small and flat (mean shriveled = 40.0% ± 19.2 SD; mean flat = 59.6% ± 19.1 SD) (Fig. 3).

Germination success

Averaging across accessions, 92% (± 5.6 SD; N=50) of seed from self-fertilized M. guttatus accessions germinated, while 62.5% (± 26.5 SD; N = 32) of self-fertilized M. nudatus seed germinated (see Table 3 for germination success by accession and cross); the difference was not significant (Fisher exact test, P = 0.484). Shriveled seeds from self-fertilized fruits germinated at a lower rate for both species (M. guttatus = 13.6%; M. nudatus = 3.5%, P < 0.001 for both comparisons, Fisher’s exact test). Hybrid seed germinated only when M. guttatus was the female, and then at significantly lower rates than self-fertilized seed (6.01% overall; Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.0001). None of the flat seeds germinated, including flat seeds from self-fertilized fruits.

Table 3.

Germination success of self-fertilized and hybrid seed

| Seed type | % Germinated | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-fertilized | |||

| Mimulus guttatus CSS4 | round | 96.0 | 25 |

| M. guttatus CSS4 | shriveled | 11.3 | 106 |

| M. guttatus CSS4 | small, flat | 0.0 | 14 |

| M. guttatus DHR14 | round | 88.0 | 25 |

| M. guttatus DHR14 | shriveled | 15.6 | 115 |

| M. nudatus CSH10 | round | 81.2 | 16 |

| M. nudatus CSH10 | shriveled | 4.40 | 91 |

| M. nudatus CSH10 | flat | 0.0 | 2 |

| M. nudatus DHRo22 | round | 43.8 | 16 |

| M. nudatus DHRo22 | shriveled | 0.0 | 30 |

| M. guttatus × M. nudatus | |||

| CSS4 × CSH10 | round | 0.0 | 1 |

| CSS4 × CSH10 | large, flattened | 10.7 | 75 |

| CSS4 × CSH10 | small, flattened | 0.0 | 50 |

| DHR14 × DHRo22 | large, flattened | 2.78 | 108 |

| DHR14 × DHRo22 | small, flattened | 0.0 | 17 |

| M. nudatus × M. guttatus | |||

| CSH10 × CSS4 | round, exploded | 0.0 | 2 |

| CSH10 × CSS4 | large, flattened | 0.0 | 104 |

| CSH10 × CSS4 | small, flattened | 0.0 | 50 |

| DHRo22 × DHR14 | large, flattened | 0.0 | 98 |

| DHRo22 × DHR14 | small, flattened | 0.0 | 138 |

All crosses are female × male.

M. guttatus seed development

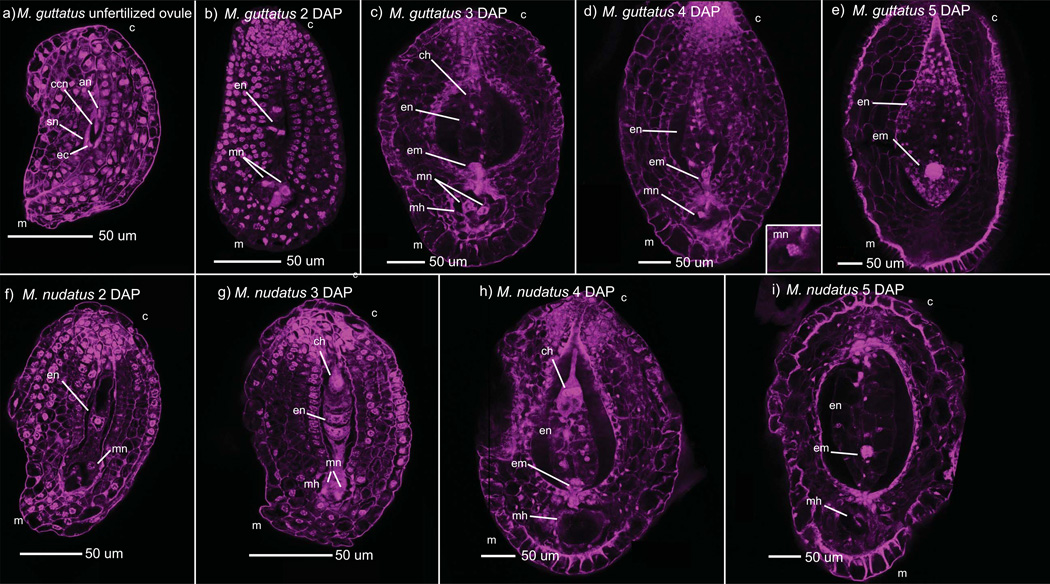

The Mimulus mature female gametophyte is the Polygonum type, and posesses two haploid synergid cells, a haploid egg cell and two antipodal cells, one of which is binucleate (as described for M. ringens (Arekal, 1965) (Fig. 5a). Microscopy revealed that within 24-h after pollination, many M. guttatus seeds are undergoing the first transverse division of the primary endosperm cell, which is accompanied by cell wall formation (see Fig. 5g for example). At 2 DAP, endosperm development consists of 2 to 8 evenly spaced endosperm cells (Fig. 5b), and the establishment of the chalazal and micropylar domains. The micropylar domain is anchored by two cells whose nuclei accumulate multiple nucleoli – signs of endoreduplication, a phenomenon commonly observed in plant tissue (Galbraith et al., 1991). The chalazal haustorium, also containing two very large nuclei, differentiates from the central endosperm, occupying the chalazal domain. At times, the cells of the micropylar haustorium penetrate beyond the base of the micropylar domain towards the chalazal domain. By 3 DAP, cellularized endosperm continues to proliferate, the embryo is at the 2/4-cell stage, and the chalazal haustorium has already begun to degrade (Fig. 5c). Between 4–5 DAP, the embryo progresses rapidly from the 8-celled stage with suspensor to the late globular stage (Fig. 5d,e). The seed contains regularly distributed endosperm cells (Fig. 5e), which become densely packed by 9 DAP (Fig. 6e); at this point the micropylar haustorium has largely degenerated, but remains visible as a darkly stained element in the micropylar domain (Fig. 6e).

Fig. 5.

Development of normal Mimulus guttatus and M. nudatus seeds. LCM images were selected that represent typical development at each stage. an, antipodal nuclei; ccn, central cell nucleus; c, chalazal end; ch, chalazal haustorium; ec, egg cell; en, endosperm; em, embryo; m, micropylar end; mh, micropylar haustorium; mn, micropylar nucleus; sn, synergid nucleus. (a) M. guttatus unfertilized ovule. (b) M. guttatus, 2 d after pollination (DAP); endosperm has undergone at least three divisions. (c) M. guttatus, 3 DAP with faintly visible chalazal haustorium, an embryo and micropylar nuclei with multiple nucleoli. (d) M. guttatus, 4 DAP with a 16-cell embryo with suspensor, and a micropylar nucleus with multiple nucleoli (micropylar nucleus is enlarged in inset). (e) M. guttatus, 5 DAP. Endosperm is densely packed and surrounds the globular embryo. (f) M. nudatus, 2 DAP with one nucleus in the chalazal domain and one nucleus in the micropylar domain. (g) M. nudatus, 3 DAP: a chalazal haustorium is plainly visible, a micropylar haustorium with nuclei has been established, and transverse division of endosperm nuclei is occurring. (h) M. nudatus, 4 DAP, displaying a prominent chalazal haustorium with two heavily nucleolated nuclei, proliferating endosperm, an 8-cell embryo and a micropylar haustorium (the cells of the micropylar haustorium are not visible in this microscopic plane). (i) M. nudatus, 5 DAP. The chalazal haustorium has largely degraded, and a 16-cell embryo is visible.

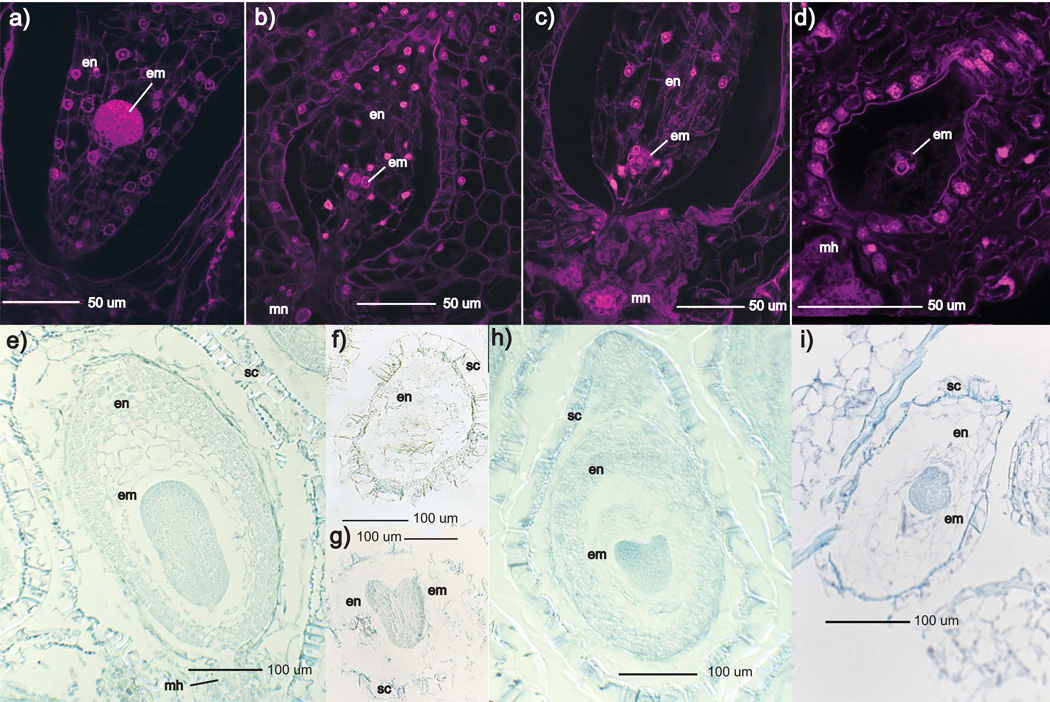

Fig. 6.

Comparison of self-fertilized Mimulus guttatus and M. nudatus seed at 5 d after pollination (DAP) (a–d) and 9 DAP (e–i). Reciprocal M. guttatus × M. nudatus hybrid seed exhibit delayed embryo growth and impaired endosperm development. All crosses are female × male. en, endosperm; em, embryo: mh, micropylar haustorium; mn, micropylar nuclei; sc, seed coat. (a) M. guttatus self-fertilized seed at 5 DAP. Endosperm is densely packed and embryo is at the globular stage. (b) M. guttatus × M. nudatus seed at 5 DAP. Endosperm resembles that of self-fertilized M. guttatus, but embryo is delayed at 8-cell stage. (c) M. nudatus self-fertilized seed at 5 DAP. Endosperm is densely packed and embryo is at the 16-cell stage; micropylar nuclei are also visible. (d) M. nudatus × M. guttatus seed at 5 DAP. Endosperm is poorly developed and embryo is at the 8-cell stage. (e) M. guttatus seed at 9 DAP. These seeds have a well-developed seed coat, densely packed endosperm, and a torpedo stage embryo. (f, g) M. guttatus × M. nudatus seed at 9 DAP, with loosely packed and irregularly deposited endosperm and a heart stage embryo. (h) M. nudatus seed at 9 DAP with densely packed endosperm and a heart stage endosperm. (i) M. nudatus × M. guttatus seed with irregularly developed endosperm and late globular stage embryo.

M. nudatus seed development

We found that the female gametophyte of M. nudatus is significantly smaller than that of M. guttatus (one-tailed t-test, P < 0.001). M. nudatus seed development parallels that of M. guttatus but with some important differences. Most notably, endosperm and embryo development proceed more slowly in M. nudatus than in M. guttatus (Fig. 5f – i). In addition, M. nudatus endosperm is less compact and regularly spaced. Division of the primary endosperm nucleus initiates by 2 DAP and completes by 3DAP (Fig. 5f,g). The chalazal and micropylar haustoria emerge by 3 DAP; both are more prominent and persist longer in M. nudatus than M. guttatus (Fig. 5g,h). At 5 DAP, the M. nudatus embryo is a 16-cell embryo (Fig. 5i). At 9 DAP, embryo development ranges from heart stage to torpedo stage (Fig. 6h).

Early hybrid seed development

Earlier work suggested that the primary barrier to hybridization between M. guttatus and M. nudatus was the formation of nonviable hybrid seed (Gardner & Macnair, 2000). To test this, we compared the development of seeds from reciprocal, interspecific crosses to that of seeds resulting from self-fertilizations for each accession of M. guttatus and M. nudatus, respectively.

We found that reciprocal M. guttatus × M. nudatus crosses produce seed with broadly similar developmental trajectories for hybrid seed: an early stage of arrested development (Fig. 7), a pattern of delayed embryo development visible by 5 DAP (Fig. 6a–d), and retarded endosperm proliferation evident at 9 DAP (Fig. 6e – i).

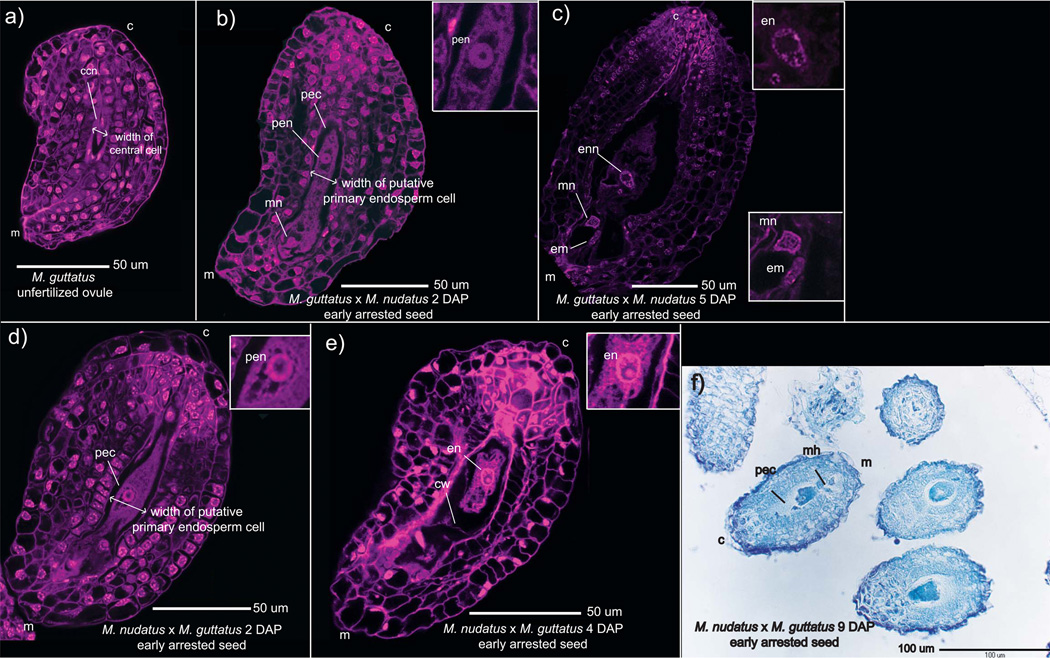

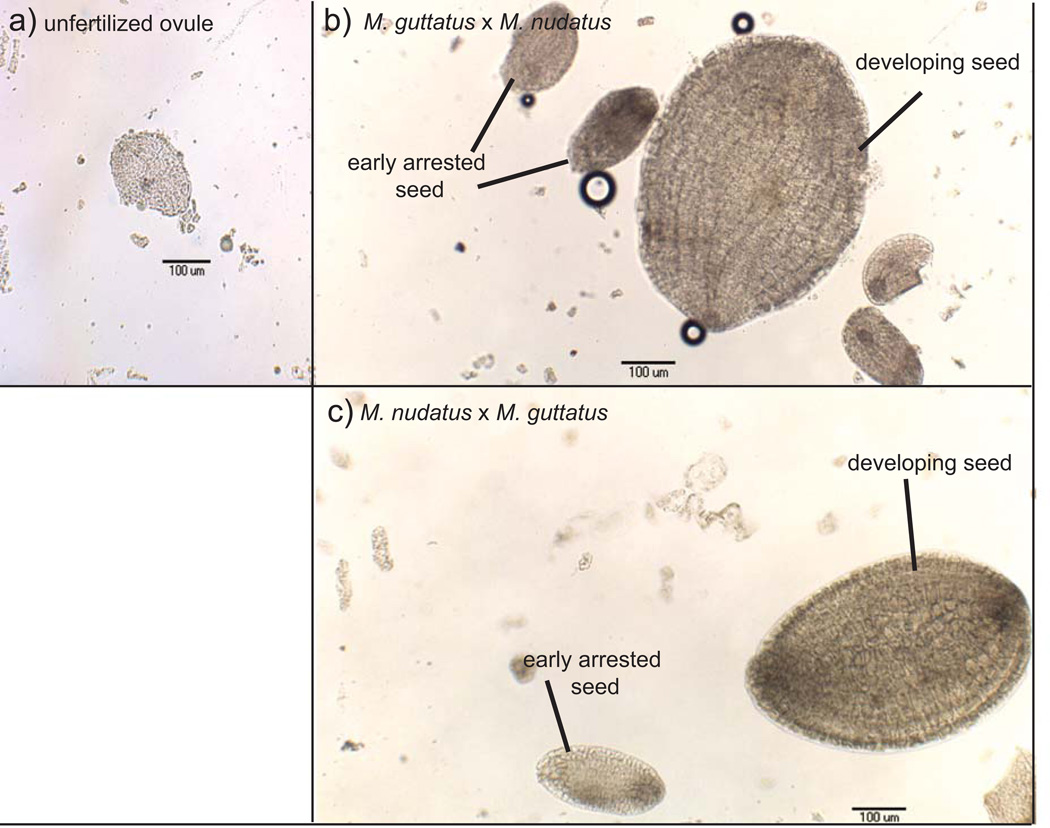

Fig. 7.

Images of the Mimulus guttatus unfertilized ovule (a) and early arrested hybrid seed from reciprocal, sympatric crosses between M. guttatus and M. nudatus (b–f). All crosses are female × male. Early arrested hybrid seed show clear signs of fertilization, including a widened primary endosperm cell compared to the width of the gametophytic central cell (a, b, d), signs of mitosis within the primary endosperm nucleus (i.e., visible nucleoli), the development of micropylar nuclei and, occasionally, a visible embryo. c, chalazal end; ccn, central cell nucleus; cw, cell wall; em, embryo; en, endosperm; enn, endosperm nucleus; m, micropylar end; mh, micropylar haustorium; mn, micropylar nucleus; pec, primary endosperm cell; pen, primary endosperm nucleus. All crosses are female × male. (a) M. guttatus female gametophyte. (b) M. guttatus × M. nudatus, 2 d after pollination (DAP) with an undivided primary endosperm nucleus; a micropylar nucleus is visible. (c) arrested M. guttatus × M. nudatus seed, 4 DAP; endosperm nucleus has multiple nucleoi evident, but there is little to no endosperm present; a micropylar nucleus with multiple nucleoli and an embryo are present. (d) M. nudatus × M. guttatus seed, 2 DAP, with an undivided primary endosperm nucleus. (e) Arrested M. nudatus × M. guttatus seed, 5 DAP. One endosperm nucleus with at least one nucleolus is visible, as is a possible endosperm cell wall. (f) M. nudatus × M. guttatus arrested seed, 9 DAP. A primary endosperm cell and micropylar haustorium are visible.

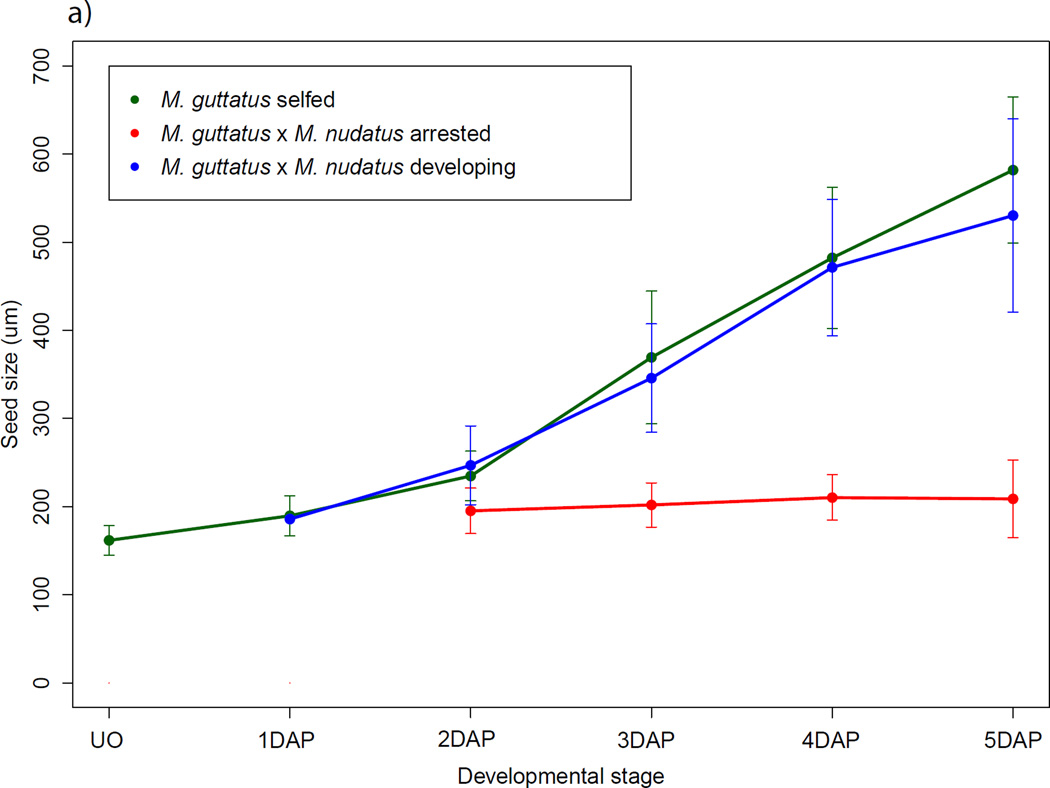

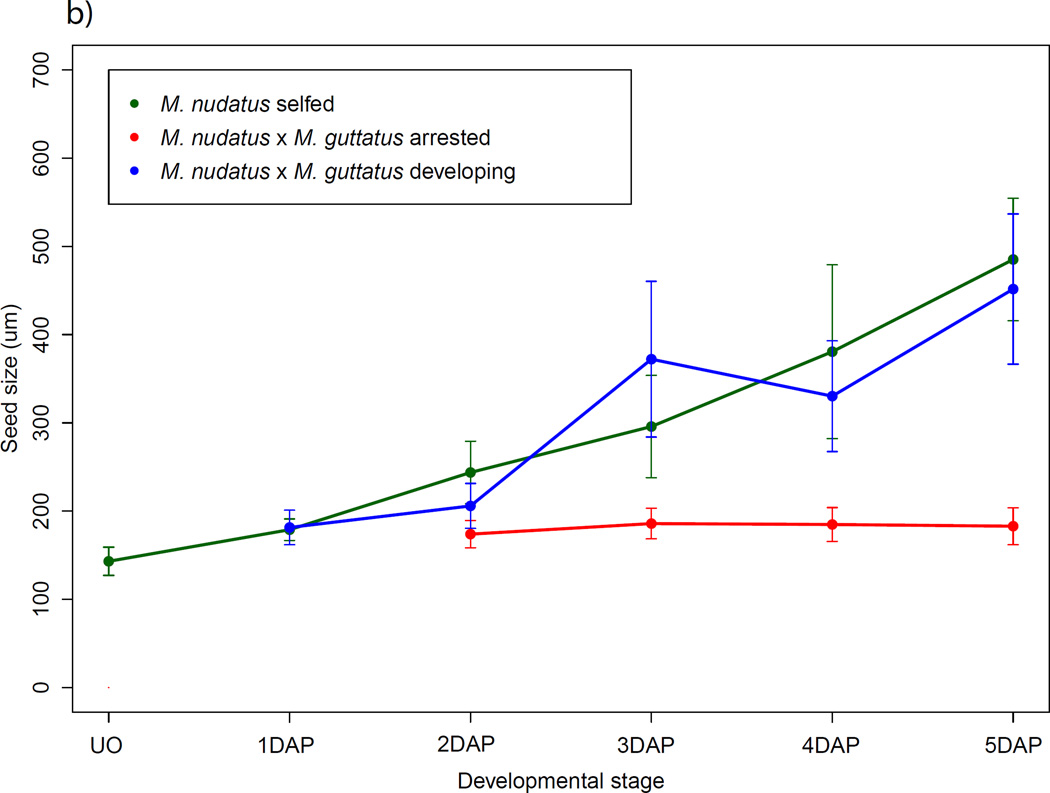

We also found that seeds that fail early are distinguishable as early as 2 DAP. At this stage, M. guttatus and M. nudatus self-fertilized seed have undergone at least one and often a few divisions of the primary endosperm cell. In hybrid seed at 2 DAP, regardless of which species serves as maternal parent, the putative primary endosperm cell widens and becomes significantly larger than the central cell of the female gametophyte of the maternal parent (t-test, P < 0.001 for both crossing directions). These seeds are also significantly longer than unfertilized ovules (t-test, P < 0.0001 for both crossing directions) but do not increase substantially in size over time (Fig. 8a,b).

Fig. 8.

Growth trajectories of self-fertilized and hybrid seed, pooled across accessions. Points represent the mean ± SD. All crosses are female × male. For seed size increase by accession, see Supporting Information Fig. S2. (a) Mimulus guttatus self-fertilized seed and M. guttatus × M. nudatus hybrid seed. (b) M. nudatus self-fertilized seed and M. nudatus × M. guttatus seed. DAP, days after pollination.

Confocal microscopy of these hybrid seeds indicated that at 2 DAP, transverse division of the primary endosperm cell fails to occur: cells walls are not evident, and the cell is filled with multiple vacuoles (Fig. 7b,d). At 4–5 DAP, early arrested seeds may show signs of division by the primary endosperm cell (Fig. 7c,e), including the presence of a few cell walls (Fig. 7e). Also at this stage, one or a few endosperm nuclei appear to contain multiple nucleoli, potentially due to endoreduplication (Fig. 7c,e). Intriguingly, for both cross directions the primary endosperm cell of 2 DAP hybrid seeds appears to be filled with nucleic acids (either DNA or RNA) bound to the propidium iodide stain. This fluorescence often, but not always, diminishes by 4–5 DAP (Fig. 7c,e). As in self-fertilized seed, micropylar haustoria are evident by 2 DAP and at later stages exhibit multiple nucleoli. A few arrested seeds may even show evidence of embryo growth (Fig. 7c), albeit at a very early stage.

Finally, exposure of hybrid fruit to vanillin stain at 5 DAP revealed two distinct sizes of dark seed, indicating a positive reaction to the proanthocyanidins present in seed coat, a tissue that develops only when fertilization has occurred. We suggest that the smaller seeds, which were darker than ovules from unpollinated ovaries (Fig. 9), represent the early arrested hybrid seeds (i.e., flat seeds), while the larger dark seeds represent hybrid seed that develop embryos and proliferating endosperm, but have a later, shriveled appearance.

Fig. 9.

Vanillin stain test for developed seed coat. All crosses are female × male. (a) Ovule from Mimulus nudatus unpollinated ovaries collected 5 d after emasculation. (b) M. guttatus × M. nudatus seed, 5 d after pollination (DAP). (c) M. nudatus × M. guttatus seed, 5 DAP. Two hybrid seed types are visible: small, arrested seed. Both appear to have a seed coat.

Later hybrid seed development

In contrast to early arresting seeds, we found that many hybrid seed undergo development that at the earliest stages (2–4 DAP) closely resembles that of the maternal parent (as described above), including in the initial pattern of endosperm division and cellularization and the timing of the emergence and eventual degeneration of chalazal and micropylar haustoria. Notably, these seeds are typically slightly smaller than seed from the self-fertilized maternal parent (Fig. 8a,b; see Fig. S3 for growth by accession). For both crossing directions, however, by 5 DAP hybrid embryo development is slightly delayed: M. guttatus × M. nudatus embryos range from 8- to 16-cell embryos, as compared to M. guttatus embryos, which are at the globular stage (Fig. 6a,b). Similarly, M. nudatus × M. guttatus hybrid embryos are at the 8-cell stage while the M. nudatus embryo is more typically at the 16-cell to early globular stage (Fig. 6c,d). This delay persists at later stages and moreover, is accompanied by defects in endosperm proliferation at 9 DAP (Fig. 6e – i). Compared to M. guttatus and M. nudatus self-fertilized seed, at 9 DAP hybrid seed exhibit endosperm that is patchily distributed and less dense. Connecting these patterns of early and late endosperm development in hybrid seed with the phenotypes of hybrid seeds found in mature fruits leads us to conclude that the early arrested seed most likely become the small, flat seeds recovered in mature fruits, while the hybrid seed that continue to develop, but in a delayed fashion, likely mature to become the shriveled seed of mature fruits (Fig. 2e,f).

Discussion

Comparing the pattern of embryo development of M. guttatus and M. nudatus with that of M. ringens (Arekal, 1965), and to a lesser extent, the cultivar M. tigrinus (Guilford & Fisk, 1951) enables us to shed light on the variation in seed development within the Phrymaeceae. Like M. ringens and M. tigrinus, both M. guttatus and M. nudatus exhibit the Polygonum-type of female gametophyte and ab initio cellular endosperm. Their endosperms also share the development of micropylar and chalazal haustoria, organs that appear to funnel nutrients from the maternal plant to the developing seed (Raghavan, 1997; Nguyen et al., 2000, Płachno et al., 2013) (Fig. 5). The chalazal haustorium appears to be more prominent and persist longer in M. nudatus than in M. guttatus or M. ringens (Arekal, 1965). Another notable developmental difference between M. guttatus and M. nudatus is the pattern of endosperm development: endosperm cellularization appears to produce cells that are more symmetrically arranged in M. guttatus than in M. nudatus at 5 DAP (Fig. 6a,c). Finally, the pace of embryo development also differs, with the M. guttatus embryo at the globular stage by 5 DAP, while that of M. nudatus is still at the 16-cell stage (Fig. 6a,c).

Dysfunctional endosperm development is associated with reduced hybrid seed viability in many groups of flowering plants, including Solanum (Johnston & Hanneman, 1982; Lester & Kang, 1998), Amaranthus (Pal et al., 1972), Lilium (Dowrick & Brandham, 1970), Oryza (Fu et al., 2009), and Arabidopsis (Scott et al., 1998), and now, Mimulus, where disrupted endosperm development manifests itself as one of two phenotypes. In the first phenotype, division of the primary endosperm cell almost never occurs. The arrested seed enlarges slightly and seed coat development occurs, indicating that fertilization has occurred, but initial growth quickly plateaus and by 5 DAP, these arrested seeds are less than 1/3 the size of developing hybrid seeds. These early arrested seeds likely eventually become the small flat seeds found in mature hybrid fruits, and never successfully germinate.

The second dysfunctional endosperm phenotype is represented by hybrid seed that appear to develop relatively normally from 1 to 5 DAP, but exhibit impaired endosperm proliferation by 9 DAP, and are ultimately deficient in total endosperm volume as demonstrated by their shriveled, phenotype at maturity. Embryo development is also impaired, with a slight delay evident at 5 DAP that continues to accumulate by 9 DAP (Fig. 6). Intriguingly, both small, flat seeds and shriveled seeds have been previously described in crosses involving copper-adapted M. guttatus (Searcy & Macnair, 1990), suggesting a common developmental mechanism underlying failed seed development in the M. guttatus species complex.

The development of these seeds suggests that even when endosperm cellularization initially proceeds, transfer of resources from the maternal plant to this nutritive tissue may yet be limited. In addition to its primary role of providing nutrition to the embryo, endosperm tissue actively regulates and modulates embryo growth (Lester & Kang, 1998, Costa et al., 2004, Hehenberger et al., 2012). We note that disruption in endosperm development may be accompanied or caused by arrested or reduced embryo development (Lester & Kang, 1998, Scott et al., 1998). Future experiments, such as embryo rescue (e.g., Rebernig et al., 2015), would be needed to tease apart the relative contributions of endosperm vs. embryo inviability to hybrid incompatibility between M. guttatus and M. nudatus.

Reproductive isolation and speciation

By visualizing the progress of pollen tubes and examining development of seeds in hybrid fruits, we conclude that interspecific pollen is functionally capable of fertilization regardless of which species serves as maternal parent, and also that under controlled conditions, fertilization produces large numbers of hybrid seed in both directions. Nevertheless, M. guttatus and M. nudatus are strongly reproductively isolated. Field experiments, as well as microsatellite and genomic sequencing data suggest that introgression between these species is rare (Gardner & Macnair, 2000; Oneal et al., 2014; L. Flagel, unpublished data). Few if any seeds of round appearance are produced from crosses between M. guttatus and M. nudatus. Early dysfunctional endosperm development results in small, flat hybrid seed that never germinate, and the fraction of these apparently inviable seed can be substantial, ranging from 23% of hybrid seed when M. guttatus is female, to 60% when M. nudatus serves as female (Fig. 3). Germination success of shriveled hybrid seed is very low (6.0% averaged across M. guttatus accessions; 0% for M. nudatus accessions).

We conclude, like Gardner & Macnair (2000), that postzygotic seed inviability forms the primary barrier between M. guttatus and M. nudatus, but differ with their conclusions in some respects. Most notably, we cannot rule out that subtle pollen-pistil interactions may yet serve as a partial prezygotic isolating mechanism, since we did not explicitly test whether interspecific pollen suffers a competitive disadvantage in fertilization success. We note that hybrid crosses where M. nudatus served as female had substantially lower seed set than self-fertilized M. nudatus, which is suggestive of a relative deficiency of M. guttatus pollen when fertilizing M. nudatus. Second, speculating that bee pollinators would find landing on the M. guttatus stigma more difficult, Gardner & Macnair (2000) concluded that gene flow was likely asymmetric and would flow more in the direction of M. guttatus to M. nudatus than the reverse. We found, however, that none of the hybrid seed in which M. nudatus was the female parent germinated. Gardner & Macnair (2000) also found that only rounded hybrid seed germinated, and at a very low rate (< 1%), while shriveled seeds did not germinate at all. We found instead that none of the few round, hybrid seed germinated, but up to 6.74% of shriveled hybrid seed germinated. We attribute this difference to the fact that we recovered very few round hybrid seed to assay for germination (N=3) and to differences in our categorization of hybrid seed: we found that mature hybrid seed lie on a continuum of endosperm fullness, and that distinguishing between round and shriveled hybrid seed was somewhat subjective. Since the shriveled appearance of these hybrid is indicative of incomplete endosperm development (Lester & Kang, 1998), in the future, seed weight may be a better measure of the completeness of endosperm development in hybrid seed.

Studies of aberrant seed development in interploidy crosses between A. thaliana accessions suggest that dosage imbalances in the expression of imprinted paternally and maternally expressed alleles and/or their regulatory targets causes dysfunctional embryo and endosperm development and ultimately, aborted seeds (Birchler, 1993; Köhler et al., 2003; Reyes & Grossniklaus, 2003; Josefsson et al., 2006; Erilova et al., 2009; Kradolfer et al., 2013). In theory, such dosage imbalances could underlie failed diploid crosses as well – such as crosses between M. guttatus and M. nudatus – via changes in imprinting status, for example, or sequence divergence or gene duplication of involved loci in one or both species, all of which might alter the critical balance of dosage-sensitive genes necessary for normal seed development (Johnston & Hanneman, 1982; Birchler & Veitia, 2010; Köhler et al., 2010, 2012; Birchler, 2014). While the vast majority of reciprocal M. guttatus × M. nudatus seeds appear deficient in endosperm development, it is intriguing that one M. nudatus × M. guttatus cross produced two rounded seeds with exploded endosperm, a phenotype associated with excessive expression of paternally imprinted alleles in failed A. thaliana interploidy crosses (Scott et al., 1998). This raises the possibility that imbalances in the dosages of genes involved in mediating maternal investment in endosperm of developing seeds may contribute to postzygotic isolation between M. guttatus and M. nudatus. Mapping the genes associated with interspecific endosperm failure will enable us to test this possibility.

While hybrid seed lethality has long been recognized as a common postzygotic isolating mechanism among members of the ecologically and genetically diverse M. guttatus sp. complex (Vickery, 1978; Gardner & Macnair, 2000), our work is the first to provide a partial developmental mechanism – early arrested endosperm development and later failures of endosperm proliferation – for that outcome, and to provide insight into the early stages of endosperm and embryo development for members of the complex. We find that despite the fact that M. nudatus is likely recently derived from a M. guttatus-like ancestor (Oneal et al., 2014), these species exhibit different patterns of embryo and endosperm development. The temporal coordination of development across cell types with different developmental roles is increasingly recognized as a critical aspect of achieving normal development (Del Toro-De León et al., 2014; Gillmor et al., 2014). We suggest that divergence in the timing of development between M. guttatus and M. nudatus may partly underlie the near complete hybrid barrier between them. Our work provides a framework for further investigation of the role of this fundamental developmental feature in the divergence between these closely related species. The extensive genomic tools already developed for the M. guttatus sp. complex, including an annotated genome sequence for M. guttatus, extensive Illumina re-sequence data from M. nudatus, and the continued development of transgenic experimental methods (Yuan et al., 2014) will only enhance future work on this important aspect of plant evolution and speciation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Phillip Benfey for allowing us to use a Zeiss Axio Observer dissecting microscope to obtain pictures of pollen-tube fluorescence, and Louise Lieberman for her assistance in obtaining images of pollen tube growth. We thank Yasheng Gao of the Duke Microscopy Facility for assistance with DIC imaging, as well as Eva Johannes at NC State University and Benjamin Carlson at Duke with assistance with laser confocal microscopy. Jessica Selby collected the populations used in this study. We thank Yaniv Brandvain, Clément Lafon-Placette, and Claudia Köhler for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. Three anonymous referees provided comments that greatly improved the writing and technical aspects of the paper. Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation grants EF-0328636 and EF-0723814 to J.H.W., as well an NIH NRSA fellowship (1F32GM097929-01) to E.O.

Footnotes

Author contributions

E.O., J.H.W. and R.G.F. planned and designed the research. E.O. collected images and data and analysed data. E.O., J.H.W. and R.G.F. wrote the manuscript.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Fig. S1 Seed set for self-fertilized M. guttatus and M. nudatus accessions and reciprocal, sympatric M. guttatus × M. nudatus crosses.

Fig. S2 Percentages of each mature seed phenotype resulting from self-fertilized M. guttatus and M. nudatus accessions and reciprocal M. guttatus × M. nudatus crosses.

Fig. S3 Growth trajectories of self-fertilized seed and hybrid seed from sympatric, pairwise crosses between M. guttatus × M. nudatus, broken down by accession.

Please note: Wiley Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

References

- Arekal GD. Embryology of Mimulus ringens . Botanical Gazette. 1965;1965:58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Beldade P, Koops K, Brakefield PM. Developmental constraints versus flexibility in morphological evolution. Nature. 2002;416:844–847. doi: 10.1038/416844a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharathan G. Endosperm development in angiosperms: a phylogenetic analysis. Biodiversity, taxonomy, and ecology. 1999;1999:167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Birchler JA. Dosage analysis of maize endosperm development. Annual Review of Genetics. 1993;27:181–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler JA. Interploidy hybridization barrier of endosperm as a dosage interaction. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2014;5:1–4. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler JA, Veitia RA. The gene balance hypothesis: implications for gene regulation, quantitative traits and evolution. New Phytologist. 2010;186:54–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boavida LC, Silva JP, Feijó JA. Sexual reproduction in the cork oak (Quercus suber L). II. Crossing intra-and interspecific barriers. Sexual Plant Reproduction. 2001;14:143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Bomblies K, Lempe J, Epple P, Warthmann N, Lanz C, Dangl JL, Weigel D. Autoimmune response as a mechanism for a Dobzhansky-Muller-type incompatibility syndrome in plants. PLoS biology. 2007;5:e236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner JT. The evolution of complexity. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton Univ. Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Burkart-Waco D, Ngo K, Dilkes B, Josefsson C, Comai L. Early disruption of maternal-zygotic interaction and activation of defense-like responses in Arabidopsis interspecific crosses. The Plant Cell Online. 2013;25:2037–2055. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.108258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandvain Y, Haig D. Divergent mating systems and parental conflict as a barrier to hybridization in flowering plants. The American Naturalist. 2005;166:330–338. doi: 10.1086/432036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brink RA, Cooper DC. The endosperm in seed development. The Botanical Review. 1947;13:479–541. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DR, Alarcon R, Wu CA. Reproductive isolation and hybrid pollen disadvantage in Ipomopsis . Journal of evolutionary biology. 2003;16:536–540. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casson S, Spencer M, Walker K, Lindsey K. Laser capture microdissection for the analysis of gene expression during embryogenesis of Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal. 2005;42:111–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley AM, Willis JH. Genetic divergence causes parallel evolution of flower color in Chilean Mimulus. New Phytologist. 2009;183:729–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa CB, Costa JA, de Queiroz LP, Borba EL. Self-compatible sympatric Chamaecrista (Leguminosae-Caesalpinioideae) species present different interspecific isolation mechanisms depending on their phylogenetic proximity. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 2013;299:699–711. [Google Scholar]

- Costa LM, Gutierrez-Marcos JF, Dickinson HG. More than a yolk: the short life and complex times of the plant endosperm. Trends in plant science. 2004;9:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Del Toro-De León G, García-Aguilar M, Gillmor CS. Non-equivalent contributions of maternal and paternal genomes to early plant embryogenesis. Nature. 2014;514:624–627. doi: 10.1038/nature13620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande SS, Cheryan M, Salunkhe DK, Luh BS. Tannin analysis of food products. Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition. 1986;24:401–449. doi: 10.1080/10408398609527441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowrick GJ, Brandram SN. Abnormalities of endosperm development in Lilium hybrids. Euphytica. 1970;19:433–442. [Google Scholar]

- Erilova A, Brownfield L, Exner V, Rosa M, Twell D, Scheid OM, Hennig L, Köhler C. Imprinting of the Polycomb Group gene MEDEA srves as a ploidy sensor in Arabidopsis . PLoS Genetics. 2009;5:e1000663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman L, Aagaard J, Tuthill JC. Toward the evolutionary genomics of gametophytic divergence: patterns of transmission ratio distortion in monkeyflower (Mimulus) hybrids reveal a complex genetic basis for conspecific pollen precedence. Evolution. 2008;62:2958–2970. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd SK, Friedman WE. Evolution of endosperm developmental patterns among basal flowering plants. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2000;161:S57–S81. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman WE. Comparative embryology of basal angiosperms. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2001;4:14–20. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman WE, Madrid EN, Williams JH. Origin of the fittest and survival of the fittest: relating female gametophyte development to endosperm genetics. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2008;169:79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fu XL, Lu YG, Liu XD, Li JQ. Crossability barriers in the interspecific hybridization between Oryza sativa and O. meyeriana . Journal of integrative plant biology. 2009;51:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith DW, Harkins KR, Knapp S. Systemic endopolyploidy in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Physiology. 1991;96:985–989. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.3.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galen C, Newport MEA. Pollination quality, seed set, and flower traits in Polemonium viscosum: complementary effects of variation in flower scent and size. American Journal of Botany. 1988;75:900–905. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M, Macnair M. Factors affecting the co-existence of the serpentine endemic Mimulus nudatus Curran and its presumed progenitor, Mimulus guttatus Fischer ex DC. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2000;69:443–459. [Google Scholar]

- Gillmor CS, Silva-Ortega CO, Willmann MR, Buendía-Monreal M, Poethig RS. The Arabidopsis Mediator CDK8 module genes CCT (MED12) and GCT (MED13) are global regulators of developmental phase transitions. Development. 2014;141:4580–4589. doi: 10.1242/dev.111229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girke T, Todd J, Ruuska S, White J, Benning C, Ohlrogge J. Microarray analysis of developing Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiology. 2000;124:1570–1581. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.4.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossniklaus U, Spillane C, Page DR, Köhler C. Genomic imprinting and seed development: endosperm formation with and without sex. Current opinion in plant biology. 2001;4:21–27. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guignard L. Sur les anthérozoides et la double copulation sexuelle chez les végétaux angiospermes. Comptes Rendus de l’Aca- demie des Sciences de Paris. 1899;128:864–871. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(01)01346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haig D. Kin conflict in seed development: an interdependent but fractious collective. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2013;29:189–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haig D, Westoby M. Genomic imprinting in endosperm: its effect on seed development in crosses between species, and between different ploidies of the same species, and its implications for the evolution of apomixis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B. 1991;333:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hehenberger E, Kradolfer D, Köhler C. Endosperm cellularization defines an important developmental transition for embryo development. Development. 2012;139:2031–2039. doi: 10.1242/dev.077057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoballah ME, Gübitz T, Stuurman J, Broger L, Barone M, Mandel T, Dell’Olivo A, Arnold M, Kuhlemeier C. Single gene-mediated shift in pollinator attraction in Petunia . The Plant Cell Online. 2007;19:779–790. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh TF, Shin J, Uzawa R, Silva P, Cohen S, Bauer MJ, Hashimoto M, Kirkbride RC, Harada JJ, Zilberman D, et al. Regulation of imprinted gene expression in Arabidopsis endosperm. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:1755–1762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019273108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston SA, Hanneman RE. Manipulations of endosperm balance number overcome crossing barriers between diploid Solanum species. Science. 1982;217:446–448. doi: 10.1126/science.217.4558.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefsson C, Dilkes B, Comai L. Parent-dependent loss of gene silencing during interspecies hybridization. Current Biology. 2006;16:1322–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns CA, Inouye DW. Techniques for pollination biologists. Colorado, CO, USA: University Press of Colorado; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Köhler C, Hennig L, Spillane C, Stephane P, Gruissem W, Grossniklaus U. The Polycomb-group protein MEDEA regulates seed development by controlling expression of the MADS-box gene PHERES1 . Genes and Development. 2003;17:1540–1553. doi: 10.1101/gad.257403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kradolfer D, Hennig L, Köhler C. Increased maternal genome dosage bypasses the requirement of the FIS polycomb repressive complex 2 in Arabidopsis seed development. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler C, Mittelsten Scheid O, Erilova A. The impact of the triploid block on the origin and evolution of polyploid plants. Trends in Genetics. 2010;26:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler C, Wolff P, Spillane C. Epigenetic mechanisms underlying genomic imprinting in plants. Annual review of plant biology. 2012;63:331–352. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard Smith J, Burian R, Kauffman S, Alberch P, Campbell J, Goodwin B, Lande R, Raup D, Wolpert L. Developmental constraints and evolution: a perspective from the Mountain Lake conference on development and evolution. Quarterly Review of Biology. 1985;60:265–287. [Google Scholar]

- Lester RN, Kang JH. Embryo and endosperm function and failure in Solanum species and hybrids. Annals of Botany. 1998;82:445–453. [Google Scholar]

- Linkies A, Graeber K, Knight C, Leubner-Metzger G. The evolution of seeds. New Phytologist. 2010;186:817–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry DB, Willis JH. A widespread chromosomal inversion polymorphism contributes to a major life-history transition, local adaptation, and reproductive isolation. PLoS Biology. 2010;8:e1000500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin NH, Willis JH. Geographical variation in postzygotic isolation and its genetic basis within and between two Mimulus species. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2010;365:3469–2478. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaschin SG. Resultate einer Revision der Befruchtungs- vorgänge bei Lilium martagon und Fritillaria tenella. Bulletin de l’Academie des Sciences de Saint Petersbourg. 1898;9:377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H, Brown RC, Lemmon BE. The specialized chalazal endosperm in Arabidopsis thaliana and Lepidium virginicum (Brassicaceae) Protoplasma. 2000;212:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Oneal E, Lowry DB, Wright KM, Zhu Z, Willis JH. Divergent population structure and climate associations of a chromosomal inversion polymorphism across the Mimulus guttatus species complex. Molecular ecology. 2014;23:2844–2860. doi: 10.1111/mec.12778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal M, Pandey RM, Khoshoo TN. Evolution and improvement of cultivated amaranths. Journal of Heredity. 1982;73:353–356. [Google Scholar]

- Płachno BJ, Świątek P, Sas-Nowosielska H, Kozieradzka-Kiszkurno M. Organisation of the endosperm and endosperm-placenta syncytia in bladderworts (Utricularia, Lentibulariaceae) with emphasis on the microtubule arrangement. Protoplasma. 2013;250:863–873. doi: 10.1007/s00709-012-0468-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey J, Bradshaw HD, Schemske DW. Components of reproductive isolation between the monkeyflowers Mimulus lewisii and M. cardinalis (Phrymaceae) Evolution. 2003;57:1520–1534. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebernig CA, Lafon-Placette C, Hatorangan MR, Slotte T, Köhler C. Non-reciprocal interspecies hybridization barriers in the Capsella genus are established in the endosperm. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JC, Grossniklaus U. Diverse functions of Polycomb group proteins during plant development. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2003;14:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(02)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Willis JH. Plant speciation. Science. 2007;317:910–914. doi: 10.1126/science.1137729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritland C, Ritland K. Variation of sex allocation among eight taxa of the Mimulus guttatus species complex (Scrophulariaceae) American Journal of Botany. 1989;1989:1731–1739. [Google Scholar]

- Roszak P, Köhler C. Polycomb group proteins are required to couple seed coat initiation to fertilization. PNAS. 2011;108:20826–20831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117111108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Running M. Nuclear staining of plants for confocal microscopy. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2007;2007 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4685. pdb-prot4685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schemske DW, Bradshaw HD. Pollinator preference and the evolution of floral traits in monkeyflowers (Mimulus) PNAS. 1999;96:11910–11915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RJ, Spielman M, Bailey J, Dickinson HG. Parent-of-origin effects on seed development in Arabidopsis thaliana . Development. 1998;125:3329–3341. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.17.3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searcy KB, Macnair MR. Differential seed production in Mimulus guttatus in response to increasing concentrations of copper in the pistil by pollen from copper tolerant and sensitive sources. Evolution. 1990;1990:1424–1435. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb03836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffin P, Olson S, Moyle LC. Asymmetrical crossing barriers in angiosperms. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B. 2001;268:861–867. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickery RK. Speciation and isolation in section Simiolus of the genus Mimulus . Taxon. 1966;15:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Vickery RK. Case studies in the evolution of species complexes in Mimulus . Evolutionary Biology. 1978;11:405–507. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JH. Amborella trichopoda (Amborellaceae) and the evolutionary developmental origins of the angiosperm progamic phase. American Journal of Botany. 2009;96:144–165. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KM, Lloyd D, Lowry DB, Macnair MR, Willis JH. Indirect evolution of hybrid lethality due to linkage with selected locus in Mimulus guttatus . PLoS biology. 2013;11:e1001497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CA, Lowry DB, Cooley AM, Wright KM, Lee YW, Willis JH. Mimulus is an emerging model system for the integration of ecological and genomic studies. Heredity. 2007;100:220–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6801018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YW, Sagawa JM, Frost L, Vela JP, Bradshaw HD. Transcriptional control of floral anthocyanin pigmentation in monkeyflowers (Mimulus) New Phytologist. 2014;204:1013–1027. doi: 10.1111/nph.12968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Immature and mature seed sizes, seed set and proportions of mature seed types: Dryad submission: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.64dh3.