Abstract

Pulmonary coagulopathy is a characteristic feature of lung injury including ventilator-induced lung injury. The aim of this individual patient data meta-analysis is to assess the effects of nebulized anticoagulants on outcome of ventilated intensive care unit (ICU) patients. A systematic search of PubMed (1966–2014), Scopus, EMBASE, and Web of Science was conducted to identify relevant publications. Studies evaluating nebulization of anticoagulants in ventilated patients were screened for inclusion, and corresponding authors of included studies were contacted to provide individual patient data. The primary endpoint was the number of ventilator-free days and alive at day 28. Secondary endpoints included hospital mortality, ICU- and hospital-free days at day 28, and lung injury scores at day seven. We constructed a propensity score-matched cohort for comparisons between patients treated with nebulized anticoagulants and controls. Data from five studies (one randomized controlled trial, one open label study, and three studies using historical controls) were included in the meta-analysis, compassing 286 patients. In all studies unfractionated heparin was used as anticoagulant. The number of ventilator-free days and alive at day 28 was higher in patients treated with nebulized heparin compared to patients in the control group (14 [IQR 0–23] vs. 6 [IQR 0–22]), though the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.459). The number of ICU-free days and alive at day 28 was significantly higher, and the lung injury scores at day seven were significantly lower in patients treated with nebulized heparin. In the propensity score-matched analysis, there were no differences in any of the endpoints. This individual patient data meta-analysis provides no convincing evidence for benefit of heparin nebulization in intubated and ventilated ICU patients. The small patient numbers and methodological shortcomings of included studies underline the need for high-quality well-powered randomized controlled trials.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13613-016-0138-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Anticoagulants, Administration, Inhalation, Mechanical ventilation, Humans, Heparin, Intensive care

Background

Pulmonary coagulopathy is a characteristic feature of various forms of lung injury, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [1–4], pneumonia [1, 5, 6], and inhalation trauma [7]. Recently, it was even demonstrated that mechanical ventilation has the potential to alter the pulmonary hemostatic balance [8], with remarkably similar changes in coagulation and fibrinolysis as found in ARDS, pneumonia, or inhalation trauma [1, 4, 7, 9].

Fibrin deposition and hyaline membrane formation are considered important early features in diffuse alveolar damage, the hallmark of ARDS [1, 10–12]. Pulmonary activation of coagulation is likely to be involved in containing inflammation or infection to the site of injury and may have evolved as a host-protective mechanism [13, 14]. However, these local hemostatic disturbances could also be deleterious, as excessive or persistent fibrin deposition has been associated with alveolar collapse due to impaired surfactant function [15], pulmonary edema and impaired gas exchange [16], and eventually pulmonary fibrosis [17].

While preclinical studies provided support for the use of nebulized or systemic anticoagulants to prevent lung injury in animals [18, 19], clinical studies in ventilated patients thus far showed conflicting results [19, 20]. Clinical trials have been performed in patients with (mild) ARDS or sepsis, focusing on systemic treatment with anticoagulants such as recombinant human (rh)-activated protein C, antithrombin, rh-tissue factor pathway inhibitor, and unfractionated heparin. All but one trial were unsuccessful in improving patient outcomes [21–32]. It has been suggested that higher concentrations of an anticoagulant in the pulmonary compartment may be necessary to affect pulmonary disturbances [19]. Thus, local administration of anticoagulants to the pulmonary compartment could be considered a more effective anticoagulant intervention.

Over the last decades, nebulized heparin has been safely administered in a number of pulmonary conditions [33–35]. Studies in healthy volunteers showed nebulized heparin to reach the lower respiratory tract [36], distribute uniformly in the lungs [36], and exert local anticoagulant effects [35]. In line herewith, nebulized heparin attenuated pulmonary coagulopathy in critically ill patients with acute lung injury [37]. Intrapulmonary administered heparin crosses the alveolar membrane into the circulation, being absorbed rapidly and released gradually into the blood [38]. Indeed, there is evidence of a dose-dependent effect of heparin nebulization on plasma levels of aPTT [35, 39], with a threshold dose of 150,000 IU of heparin resulting in a measurable increase in aPTT [35]. This effect on systemic coagulation does not seem to potentiate the risk of bleedings [39–41], suggesting heparin nebulizations to be safe. Nevertheless, data on the feasibility and safety of heparin nebulizations in ventilated patients are scarce [19], and there are very limited data on the use of nebulized anticoagulants in ventilated patients. A systematic review recently showed conflicting effects of nebulized anticoagulation in burn patients with inhalation injury, a patient population in which this intervention is frequently applied [20]. It remains unclear whether nebulized anticoagulation is beneficial for all ventilated intensive care unit (ICU) patients. We performed an individual patient data meta-analysis to determine the association between nebulized anticoagulants and outcomes of intubated and ventilated ICU patients to test the hypothesis that nebulization of anticoagulants improves outcome.

Methods

Systematic search

Publications were identified through a systematic search of PubMed (1966–2014), Scopus, EMBASE, and Web of Science. Search terms referred to the intervention (nebulized, vaporized, aerosolized) and anticoagulant agents (anticoagulants, anticoagulation, antithrombins, heparin), as well as conditions of the patient population (acute lung injury, ARDS, critical illness, burn, smoke, inhalation injury) and mechanical ventilation. Searches were not limited by date or language. The detailed search strategy is shown in Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

Titles and available abstracts of the articles identified were screened. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they evaluated nebulized or aerosolized anticoagulants, including heparins, heparinoids, antithrombins, and/or fibrinolytics, in ventilated ICU patients. There were no restrictions regarding age of patients. Case reports and ongoing studies were excluded. Retrieved articles were screened for pertinent information, and reference lists of eligible articles were screened for potentially important papers. Quality of evidence for randomized and nonrandomized studies were assessed with use of, respectively, the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias [42] and the Newcastle Ottawa Scale [43], see Additional file 1: Appendix 5.

Collection of individual patient data

The corresponding author of each included study was contacted and asked for individual patient data. This included demographic and baseline characteristics, dose and duration of nebulized anticoagulants, duration of ventilation, occurrence of pneumonia, length of stay in the ICU and hospital, and mortality. Ventilatory parameters and lung injury scores (LIS) [44] were collected up to 7 days from admission. Data were accepted in any kind of electronic format.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the number of ventilator-free days and alive at day 28, defined as the number of days alive and without ventilation until day 28.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included mortality during hospital stay, ICU-free days at day 28, defined as the number alive and outside the ICU at day 28, and hospital-free days and alive at day 28, defined as the number of days alive and outside hospital at day 28. PaO2/FiO2 and LIS at day seven, calculated from the available data, and occurrence of pneumonia during hospital stay.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as median and interquartile range (median [IQR]). Binary and categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages [n (%)].

Patients were analyzed according to use or not of nebulized anticoagulants. Time-to-event was defined as time from the day of inclusion in the study to the event of interest. We used a Cox proportional-hazards regression model to examine simultaneous effects of multiple covariates on outcomes, censoring patient data at the time of death, or hospital discharge. In all models, the categorical variables were tested for trend with the nonuse of nebulized anticoagulants as reference. The proportional-hazards assumption was assessed plotting partial residuals against survival time. A test for interaction between pairs of variables in the final model was performed. The effect of each variable in these models was assessed with the use of the Wald test and described by the hazard ratio with 95 % confidence interval (CI). The initial model included age and baseline PaO2/FiO2. The final model was developed by dropping each variable in turn from the model and by conducting likelihood-ratio tests to compare the full and the nested models. We used a significance level of 0.05 as the cutoff to exclude a variable from the model. Finally, use of nebulized anticoagulants (no vs. yes) was added to the model. Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank test were used to determine the univariate significance of the study variables.

A linear mixed model was used to analyze time-course variables. A repeated-measures generalized linear model (GLM) was used to assess the time interaction for ventilatory and oxygenation parameters during mechanical ventilation. The model includes two factors: (1) study group (fixed factor), each level of the study group factor had a different linear effect on the value of the dependent variable; (2) time as covariate, time was considered to be a random sample from a larger population of values, and the effect was not limited to the chosen times.

Subgroup analyses were used to assess the effect of tidal volume size in the following prespecified subgroups: (1) age (<18 vs. ≥18 years); (2) dose of nebulized anticoagulant (low dose, defined as 30,000 U/day versus high dose, defined as ≥60,000 U/day); and (3) patient population (burn vs. non-burn). Propensity scores were estimated for each patient with logistic regression using two clinically relevant baseline characteristics (age and baseline PaO2/FiO2). Propensity score matching is described in detail in the supplemental material (Appendix file 1: Appendix 4). We conducted a post hoc sensitivity analysis in the matched cohort, including age (<18 vs. ≥18 years), dose of nebulized anticoagulant (low dose, defined as 30,000 U/day vs. high dose, defined as 60,000 U/day or higher), patient population (burn vs. non-burn), and tidal volume size (low, defined as ≤560 ml vs. high, defined as >560 ml by using the median as a cutoff value). All analyses were conducted with Review Manager v.5.1.1 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark), SPSS v.20 (IBM Corporation, New York, USA), and R v.2.12.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For all analyses two-sided P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Systematic search

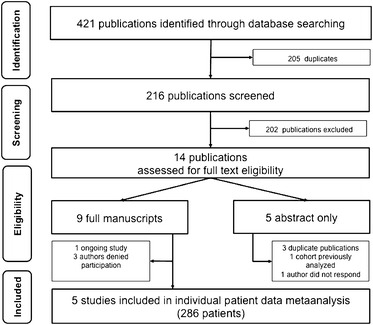

The search yielded 216 potentially relevant publications (Fig. 1). Based on the titles or abstracts, 202 publications were excluded. The remaining 14 publications reported on ten clinical studies, all on nebulized heparin [39–41, 45–55]. One publication reported on an ongoing trial [49]. Nine studies were eligible for inclusion in our individual patient data meta-analysis (521 patients). However, the corresponding authors of three studies did not provide the individual patient data [41, 45, 48], and one could not be contacted [53]. Therefore, data from five studies (286 patients) were available for the meta-analysis [39, 40, 50–52].

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow diagram showing the literature search and selection strategy

Table 1 summarizes the study characteristics of the included studies. All three studies conducted in burn patients with inhalation injury were retrospective studies with historical controls [50–52]. One open label phase I study and one randomized controlled trial were conducted in critically ill patients [39, 40]. One study had a mixed population with both pediatric and adult patients [50], and all other studies were performed in adult patients. Dosage of heparin varied from 30,000 to 400,000 U/day.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the individual patient data meta-analysis

| Authors (year) | Design | Population (adult/pediatric) | Number of patients | Dose of heparin | Outcomes included in IPD meta-analysis | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heparin | Control | ||||||

| Holt (2008) | Retrospective with historical control | Smoke inhalation (adult and pediatric) | 62 | 88 | 30,000 | VFD-28; hospital mortality; pneumonia; PaO2/FiO2 at day 7; hospital-free days and alive at day 28 | [50] |

| Dixon (2008) | Open label phase 1 trial | Critically ill (adult) | 16 | – | 50,000–400,000 | VFD-28; ICU mortality; ICU and hospital-free days and alive at day 28 | [39] |

| Miller (2009) | Retrospective with historical control | Smoke inhalation (adult) | 16 | 14 | 60,000 | VFD-28; hospital mortality; PaO2/FiO2 and LIS at day 7; ICU and hospital-free days and alive at day 28; pneumonia | [52] |

| Dixon (2010) | Randomized controlled trial | Critically ill (adult) | 25 | 25 | 150,000 | VFD-28; hospital mortality; PaO2/FiO2 and LIS at day 7; ICU and hospital-free days and alive at day 28 | [40] |

| Kashefi (2014) | Retrospective with historical control | Smoke inhalation (adult) | 20 | 20 | 30,000 | VFD-28; hospital mortality; pneumonia; PaO2/FiO2; and hospital-free days and alive at day 28 | [51] |

VFD-28 ventilator-free days and alive at day 28, IPD individual patient data meta-analysis, LIS Lung injury scores

Of note, patients treated with nebulized heparin were ventilated with lower tidal volumes during the first 7 days of ventilation (Additional file 1: Appendix 3: Tables S1 and Appendix 4: Table S5). All other ventilatory parameters were similar between the two study groups (Additional file 1: Appendix 2: Figures S2 and S3; Appendix 3: Table S1).

Table 2 summarizes the demographic data of the included patients. For the propensity score-matched cohort, 248 patients could be analyzed (Additional file 1: Appendix 4: Table S3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the patients included in the individual patient data analysis

| Variables | Overall cohort (N = 286) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nebulized heparin (N = 139) | Control (N = 147) | SD (%), P | |

| Age, years | 50.0 (36.0–69.0) | 45.0 (31.0–63.0) | 17.6, 0.09 |

| (N = 139) | (N = 147) | ||

| Gender, male (%) | 81 (65.9) | 107 (72.8) | −19.0, 0.14 |

| APACHE III | 22.0 (17.0–31.0) | 24.0 (15.0–32.0) | 5.1, 0.74 |

| (N = 57) | (N = 39) | ||

| % TBSA | 25.5 (12.9–52.2) | 31.2 (16.5–52.2) | −5.1, 0.51 |

| (N = 90) | (N = 110) | ||

| Dosage of heparin (U/day) | 30,000 | 0.0 | – |

| (30,000–100,000) | (0.0–0.0) | ||

| Dosage of NAC (mg/day) | 3600 (3600–3600) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | – |

| Duration of treatment | 7.0 (3.0–12.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | – |

| Baseline LIS | 2.0 (0.7–2.5) | 2.0 (1.2–3.0) | −26.2, 0.29 |

| (N = 41) | (N = 39) | ||

| Baseline PaO2/FiO2 | 219.5 (158.2–316.5) | 270.0 (163.5–366.5) | −18.3, 0.09 |

| (N = 136) | (N = 141) | ||

Values are median (IQR) or no./total no. (%). Not all requested data were available for each study

SD standardized difference, TBSA total burn surface area, NAC N-acetylcysteine, LIS lung injury scores, N number of patients

Effects of heparin on outcome

The median number of ventilator-free days and alive at day 28 did not differ in patients treated with nebulized heparin compared to patients in the control group (14, IQR 0–23 vs. 6, IQR 0–22 days, P = 0.459). A statistically significant difference was found for ICU-free days at day 28 (3 [0–19] vs. 0 [0–14] days, P = 0.035). The LIS at day seven were also significantly lower in patients treated with nebulized heparin (2.0 [1.0–2.5] vs. 2.2 [1.7–3.0] days, P = 0.027). There was no difference in hospital mortality (Table 3 and Additional file 1: Appendix 2: Figure S1), hospital-free days and alive at day 28 or occurrence of pneumonia during hospital stay (Table 3).

Table 3.

Primary and secondary outcomes

| Variables | Nebulized heparin (N = 139) | Control (N = 147) | Odds ratioa (95 % CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Ventilator-free days at day 28 | 14.0 (0.0–23.0) | 6.0 (0.0–22.0) | 0.459 | |

| (N = 139) | (N = 144) | |||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Overall mortality | 34/139 (24.5) | 35/147 (23.8) | 0.65 (0.50–1.56)b | 0.653 |

| (N = 139) | (N = 147) | |||

| PaO2/FiO2 at day seven (mmHg) | 242.5 (206.0–300.0) | 220.2 (179.4–297.7) | 0.098 | |

| (N = 61) | (N = 78) | |||

| LIS at day seven | 2.0 (1.0–2.5) | 2.2 (1.7–3.0) | 0.027 | |

| (N = 40) | (N = 48) | |||

| Pneumonia during hospital stay | 48/82 (58.5) | 48/106 (45.3) | 1.49 (0.79–2.80) | 0.219 |

| (N = 82) | (N = 106) | |||

| ICU-free days at day 28 | 2.9 (0.0–19.0) | 0.0 (0.0–14.2) | 0.035 | |

| (N = 78) | (N = 62) | |||

| Hospital-free days at day 28 | 0.0 (0.0–12.0) | 0.0 (0.0–14.0) | 0.951 | |

| (N = 139) | (N = 147) | |||

Values are median (IQR), and others are no./total no. (%)

Not all requested data were available for each study

LIS lung injury scores, CI confidence interval, N number of patients

aAdjusted by: age and baseline PaO2/FiO2

bPresented as hazard ratio adjusted by: age, %TBSA, and baseline PaO2/FiO2

In subgroup analyses, there was no difference in number of ventilator-free days at day 28, overall mortality nor number of hospital-free days and alive at day 28, according to age (<18 vs. ≥18 years), dose of heparin, type of population and tidal volume size (Additional file 1: Appendix 3: Table S2).

Propensity score-matched cohort

Results of the meta-analysis in the propensity score-matched cohort are presented in the online supplement (Additional file 1: Appendix 4: Tables S3–S6).

The median number of ventilator-free days at day 28 in patients treated with nebulized heparin was higher than that in control patients (16 [0–23] vs. 5 [0–20] days), but again this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.133). Also, no statistical differences were found for the number of ICU-free days and alive at day 28 and LIS at day seven and other secondary endpoints (Additional file 1: Appendix 2: Figure S1 and Appendix 4: Table S4).

Also in this part of the analysis, it was found that patients treated with nebulized heparin were ventilated with lower tidal volumes than control patients during the first 7 days of ventilation (Additional file 1: Appendix 4: Table S5). In the post hoc sensitivity analysis on age, dose of heparin, type of population and tidal volume size, no differences were found for ventilator-free days and hospital-free days at day 28 (Additional file 1: Appendix 4: Table S6).

Discussion

Nebulization of heparin, alone or combined with other agents, did not improve the outcome of mechanically ventilated patients in this individual patient data meta-analysis. Even though patients who received nebulization with heparin demonstrated higher numbers of ventilator-free days and alive at day 28, differences were not statistically significant. We did find a higher number of ICU-free days and alive at day 28 and lower LIS at day seven in patients treated with nebulized heparin. A propensity score-matched cohort analysis, however, showed no beneficial effects of heparin nebulization.

The aim of this individual patient data meta-analysis was to investigate the effectiveness of nebulized anticoagulants in intubated and ventilated ICU patients. Since heparin was the only anticoagulant agent used in the included studies, we are unable to ascertain the potential efficacy of any other anticoagulant, due to paucity of available evidence. Also, the majority of patients included were patients with inhalation injury (220 of 286). Thus, conclusions on the effects of nebulized heparin for intubated and ventilated ICU patients in general cannot be made. As adverse effects of mechanical ventilation may be more severe in burn patients, it is possible that these patients benefit more from nebulized anticoagulants compared to non-burn or smoke inhalation patients [19].

Reported effects of nebulized heparin on duration of mechanical ventilation and other outcomes such as mortality in patients with inhalation injury have been conflicting. Beneficial effects of heparin nebulization could have been confounded by improvements in ICU care in general as they were conducted around a change in institutional protocol [45, 52]. In two other before–after studies no beneficial effects of heparin nebulizations were seen [50, 51]. Furthermore, in three of the included studies [50–52], nebulized heparin was combined with the use of mucolytic agents and bronchodilators. This highlights the difficulty to distinguish between the effects of heparin nebulization and other parts of treatment on patient outcome in retrospective studies with historical controls.

One important finding of our individual patient data meta-analysis was that patients receiving heparin nebulization were ventilated with lower tidal volumes compared to control patients. While in theory improved clinical outcomes could have been caused by nebulization of heparin, it could also function as an important confounder, since low tidal volume ventilation is associated with a better outcome, also in patients without ARDS [56–60]. Still, relatively high tidal volumes were used in all included studies which may hamper extrapolation to current ventilation practices. On the other hand, while lower tidal volumes are increasingly being used [61, 62], guidelines inconsistently advise on tidal volume size in ICU patients without ARDS and current ventilation practice is uncertain [63].

Dosage of heparin varied from 30,000 to 400,000 U/day. Several studies suggested a dose-dependent effect of heparin nebulization in which dosages of 30,000 U/day improved outcomes in pediatric patients [45] but failed to improve outcomes in adults [50, 51], while higher dosages did improve outcome of adult patients [48, 52]. The present meta-analysis could not confirm this. Types of nebulizers and its position in the circuit may affect the delivery of nebulized drugs in ventilated patients [64–66]. Furthermore, aerosol particle size distribution and heparin concentrations may also influence the amount of heparin delivered to the lower respiratory tract [67]. The method of nebulization differed between studies. Three studies used mesh nebulizers [39, 40, 50], and two studies used jet nebulizers [51, 52]. Thus, the delivered amount of nebulized drugs may have varied.

Our results contradict the conclusion of a previous systematic review concluding that inhaled anticoagulation regimens improve survival and decrease morbidity in smoke inhalation patients [20]. This may be due to some major differences between the two studies. First, as our aim was to investigate the effect of heparin nebulization in any critically ill patient, we included different studies. Second, the use of individual patient data allowed standardization of the analyses across studies irrespective of how the data were reported [68].

One major limitation of this meta-analysis is that we were only able to analyze the individual data of 286 patients out of 521 potentially eligible patients as the authors of four studies did not provide individual patient data. Other limitations are caused by the methodological shortcomings of included studies. Only one of the included studies was a small, but properly conducted randomized controlled trial [40]. The other studies, mostly small in size, used an open label design or were retrospective cohort studies with use of historical controls. Due to these limitations, the results from this meta-analysis should be interpreted with great caution. To account for some of those limitations we used propensity score matching correcting for relevant baseline characteristics. However, imbalances such as the presence of unmeasured confounders are likely to remain [69]. Nevertheless, the post hoc sensitivity analysis indicates that the results of this meta-analysis were affected neither by factors such as age, presence of burn, or inhalation injury nor by differences in tidal volume size and heparin dosages.

Conclusion

No beneficial effects of heparin nebulization on the outcome of ventilated patients were observed in this individual patient data meta-analysis. The small patient numbers and methodological shortcomings of included studies underline the need for high-quality well-powered randomized controlled trials to determine the effect of heparin nebulization on outcome of intubated and ventilated ICU patients.

Authors’ contributions

GJG, MJS, JH, and ASN contributed to the conception and design of the study, drafted, and revised the manuscript. ASN acquired and analyzed the data. AC, BD, EME, IF, SD, and ACM provided the individual patient data and critically revised the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by ‘de Nederlandse Brandwondenstichting’ (the Dutch Burn Association, Beverwijk, the Netherlands).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CI

confidence interval

- GLM

generalized linear model

- GRADE

grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation

- ICU

intensive care unit

- IQR

interquartile range

- LEICA

Laboratory of Experimental Intensive Care and Anesthesiology

- LIS

lung injury scores

- SD

standard deviation

Additional file

10.1186/s13613-016-0138-4 Online supplemental material.

Contributor Information

Gerie J. Glas, Email: g.j.glas@amc.uva.nl

Ary Serpa Neto, Email: aryserpa@terra.com.br.

Janneke Horn, Email: j.horn@amc.uva.nl.

Amalia Cochran, Email: amalia.cochran@hsc.utah.edu.

Barry Dixon, Email: Barry.DIXON@svha.org.au.

Elamin M. Elamin, Email: eelamin@health.usf.edu

Iris Faraklas, Email: irisfaraklas@gmail.com.

Sharmila Dissanaike, Email: sharmila.dissanaike@ttuhsc.edu.

Andrew C. Miller, Email: taqwa1@gmail.com

Marcus J. Schultz, Email: marcus.j.schultz@gmail.com

References

- 1.Gunther A, Mosavi P, Heinemann S, Ruppert C, Muth H, Markart P, et al. Alveolar fibrin formation caused by enhanced procoagulant and depressed fibrinolytic capacities in severe pneumonia. Comparison with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(2 Pt 1):454–462. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9712038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Idell S. Coagulation, fibrinolysis, and fibrin deposition in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4 Suppl):S213–S220. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057846.21303.AB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Idell S, James KK, Levin EG, Schwartz BS, Manchanda N, Maunder RJ, et al. Local abnormalities in coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways predispose to alveolar fibrin deposition in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1989;84(2):695–705. doi: 10.1172/JCI114217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vervloet MG, Thijs LG, Hack CE. Derangements of coagulation and fibrinolysis in critically ill patients with sepsis and septic shock. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1998;24(1):33–44. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levi M, Schultz MJ, Rijneveld AW, Van Der Poll T. Bronchoalveolar coagulation and fibrinolysis in endotoxemia and pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4 Suppl):S238–S242. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057849.53689.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schultz MJ, Millo J, Levi M, Hack CE, Weverling GJ, Garrard CS, et al. Local activation of coagulation and inhibition of fibrinolysis in the lung during ventilator associated pneumonia. Thorax. 2004;59(2):130–135. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.013888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofstra JJ, Vlaar AP, Knape P, Mackie DP, Determann RM, Choi G, et al. Pulmonary activation of coagulation and inhibition of fibrinolysis after burn injuries and inhalation trauma. J Trauma. 2011;70(6):1389–1397. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820f85a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz MJ, Determann RM, Royakkers AA, Wolthuis EK, Korevaar JC, Levi MM. Bronchoalveolar activation of coagulation and inhibition of fibrinolysis during ventilator-associated lung injury. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:961784. doi: 10.1155/2012/961784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofstra JJ, Haitsma JJ, Juffermans NP, Levi M, Schultz MJ. The role of bronchoalveolar hemostasis in the pathogenesis of acute lung injury. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2008;34(5):475–484. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1092878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Consensus Conferences in Intensive Care Medicine Ventilator-associated Lung Injury in ARDS. This official conference report was cosponsored by the American Thoracic Society, The European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, and The Societe de Reanimation de Langue Francaise, and was approved by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(6):2118–2124. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.ats16060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bastarache JA, Ware LB, Bernard GR. The role of the coagulation cascade in the continuum of sepsis and acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27(4):365–376. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-948290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro CY. ARDS and diffuse alveolar damage: a pathologist’s perspective. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;18(1):13–19. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opal SM. Phylogenetic and functional relationships between coagulation and the innate immune response. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(9 Suppl):S77–S80. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200009001-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultz MJ, Dixon B. A breathtaking and bloodcurdling story of coagulation and inflammation in acute lung injury. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(12):2050–2052. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seeger W, Stohr G, Wolf HR, Neuhof H. Alteration of surfactant function due to protein leakage: special interaction with fibrin monomer. J Appl Physiol. 1985;58(2):326–338. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laterre PF, Wittebole X, Dhainaut JF. Anticoagulant therapy in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4 Suppl):S329–S336. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057912.71499.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall R, Bellingan G, Laurent G. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: fibrosis in the fast lane. Thorax. 1998;53(10):815–817. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.10.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Idell S. Anticoagulants for acute respiratory distress syndrome: can they work? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(4):517–520. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2102095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuinman PR, Dixon B, Levi M, Juffermans NP, Schultz MJ. Nebulized anticoagulants for acute lung injury—a systematic review of pre-clinical and clinical investigations. Crit Care. 2012;16(2):R70. doi: 10.1186/cc11325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller AC, Elamin EM, Suffredini AF. Inhaled anticoagulation regimens for the treatment of smoke inhalation-associated acute lung injury: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):413–419. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a645e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abraham E, Reinhart K, Opal S, Demeyer I, Doig C, Rodriguez AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of tifacogin (recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor) in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(2):238–247. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Afshari A, Wetterslev J, Brok J, Moller AM. Antithrombin III for critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD005370. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005370.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, LaRosa SP, Dhainaut JF, Lopez-Rodriguez A, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(10):699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhainaut JF, Laterre PF, Janes JM, Bernard GR, Artigas A, Bakker J, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in the treatment of severe sepsis patients with multiple-organ dysfunction: data from the PROWESS trial. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(6):894–903. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1731-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisele B, Lamy M, Thijs LG, Keinecke HO, Schuster HP, Matthias FR, et al. Antithrombin III in patients with severe sepsis. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind multicenter trial plus a meta-analysis on all randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials with antithrombin III in severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(7):663–672. doi: 10.1007/s001340050642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaimes F, De La Rosa G, Morales C, Fortich F, Arango C, Aguirre D, et al. Unfractioned heparin for treatment of sepsis: a randomized clinical trial (The HETRASE Study) Crit Care Med. 2009;37(4):1185–1196. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819c06bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laterre PF, Opal SM, Abraham E, LaRosa SP, Creasey AA, Xie F, et al. A clinical evaluation committee assessment of recombinant human tissue factor pathway inhibitor (tifacogin) in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Crit Care. 2009;13(2):R36. doi: 10.1186/cc7747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu KD, Levitt J, Zhuo H, Kallet RH, Brady S, Steingrub J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of activated protein C for the treatment of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(6):618–623. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-419OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marti-Carvajal AJ, Sola I, Gluud C, Lathyris D, Cardona AF. Human recombinant protein C for severe sepsis and septic shock in adult and paediatric patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD004388. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004388.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS, Dhainaut JF, Douglas IS, Finfer S, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in adults with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(22):2055–2064. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warren BL, Eid A, Singer P, Pillay SS, Carl P, Novak I, et al. Caring for the critically ill patient. High-dose antithrombin III in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1869–1878. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wunderink RG, Laterre PF, Francois B, Perrotin D, Artigas A, Vidal LO, et al. Recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor in severe community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(11):1561–1568. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201007-1167OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bendstrup KE, Jensen JI. Inhaled heparin is effective in exacerbations of asthma. Respir Med. 2000;94(2):174–175. doi: 10.1053/rmed.1999.0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monagle K, Ryan A, Hepponstall M, Mertyn E, Monagle P, Ignjatovic V, et al. Inhalational use of antithrombotics in humans: review of the literature. Thromb Res. 2015;136(6):1059–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markart P, Nass R, Ruppert C, Hundack L, Wygrecka M, Korfei M, et al. Safety and tolerability of inhaled heparin in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2010;23(3):161–172. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2009.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bendstrup KE, Chambers CB, Jensen JI, Newhouse MT. Lung deposition and clearance of inhaled (99 m)Tc-heparin in healthy volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5 Pt 1):1653–1658. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9809123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dixon B, Schultz MJ, Hofstra JJ, Campbell DJ, Santamaria JD. Nebulized heparin reduces levels of pulmonary coagulation activation in acute lung injury. Crit Care. 2010;14(5):445. doi: 10.1186/cc9269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaques LB, Mahadoo J, Kavanagh LW. Intrapulmonary heparin. A new procedure for anticoagulant therapy. Lancet. 1976;2(7996):1157–1161. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(76)91679-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dixon B, Santamaria JD, Campbell DJ. A phase 1 trial of nebulised heparin in acute lung injury. Crit Care. 2008;12(3):R64. doi: 10.1186/cc6894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dixon B, Schultz MJ, Smith R, Fink JB, Santamaria JD, Campbell DJ. Nebulized heparin is associated with fewer days of mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14(5):R180. doi: 10.1186/cc9286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yip LY, Lim YF, Chan HN. Safety and potential anticoagulant effects of nebulised heparin in burns patients with inhalational injury at Singapore General Hospital Burns Centre. Burns. 2011;37(7):1154–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murray JF, Matthay MA, Luce JM, Flick MR. An expanded definition of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138(3):720–723. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.3.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Desai MH, Mlcak R, Richardson J, Nichols R, Herndon DN. Reduction in mortality in pediatric patients with inhalation injury with aerosolized heparin/acetylcystine therapy. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1998;19(3):210–212. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199805000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dixon B, Santamaria D, Campbell J. Nebulized heparin in acute lung injury. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2009;22(2):203. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dixon B, Schultz M, Fink JB, Campbell D, Santamaria JD. Nebulised heparin is associated with fewer days of mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183. (1 Meeting Abstracts) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Elsharnouby NM, Eid HEA, Abou Elezz NF, Aboelatta YA. Heparin/N-acetylcysteine: an adjuvant in the management of burn inhalation injury. A study of different doses. J Crit Care. 2014;29(1):182.e1–182.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glas GJ, Muller J, Binnekade JM, Cleffken B, Colpaert K, Dixon B, et al. HEPBURN—investigating the efficacy and safety of nebulized heparin versus placebo in burn patients with inhalation trauma: study protocol for a multi-center randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:91. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holt J, Saffle JR, Morris SE, Cochran A. Use of inhaled heparin/N-acetylcystine in inhalation injury: does it help? J Burn Care Res. 2008;29(1):192–195. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31815f596b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kashefi NS, Nathan JI, Dissanaike S. Does a nebulized heparin/N-acetylcysteine protocol improve outcomes in adult smoke inhalation? Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;2(6):e165. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller AC, Rivero A, Ziad S, Smith DJ, Elamin EM. Influence of nebulized unfractionated heparin and N-acetylcysteine in acute lung injury after smoke inhalation injury. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30(2):249–256. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318198a268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Otremba S, Faris J. Hall Zimmerman L, Barbat S, White M. Inhaled heparin in critically ill patients with smoke inhalation injury. Crit Care Med. 2013;1:A231–A232. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000440161.08953.76. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rivero A, Elamin E, Nguyen V, Cruse W, Smith D. Can nebulized heparin and N-acetylcysteine reduce acute lung injury after inhalation lung insult? Chest. 2007;132(4):565S. doi: 10.1378/chest.132.4_MeetingAbstracts.565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kashefi N, Dissanaike S. Does a nebulized heparin/N-acetylcysteine protocol improve clinical outcomes in adult patients with inhalation injury? J Burn Care Res. 2013;1:S82. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Determann RM, Royakkers A, Wolthuis EK, Vlaar AP, Choi G, Paulus F, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with conventional tidal volumes for patients without acute lung injury: a preventive randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14(1):R1. doi: 10.1186/cc8230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gajic O, Dara SI, Mendez JL, Adesanya AO, Festic E, Caples SM, et al. Ventilator-associated lung injury in patients without acute lung injury at the onset of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(9):1817–1824. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000133019.52531.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gajic O, Frutos-Vivar F, Esteban A, Hubmayr RD, Anzueto A. Ventilator settings as a risk factor for acute respiratory distress syndrome in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(7):922–926. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2625-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Serpa NA, Cardoso SO, Manetta JA, Pereira VG, Esposito DC, Pasqualucci MO, et al. Association between use of lung-protective ventilation with lower tidal volumes and clinical outcomes among patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308(16):1651–1659. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Serpa Neto A, Simonis FD, Barbas CS, Biehl M, Determann RM, Elmer J, et al. Association between tidal volume size, duration of ventilation, and sedation needs in patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(7):950–957. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Putensen C, Theuerkauf N, Zinserling J, Wrigge H, Pelosi P. Meta-analysis: ventilation strategies and outcomes of the acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute lung injury. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(8):566–576. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-8-200910200-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Esteban A, Ferguson ND, Meade MO, Frutos-Vivar F, Apezteguia C, Brochard L, et al. Evolution of mechanical ventilation in response to clinical research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(2):170–177. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-893OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neto A, Barbas C, Raventós A, Canet J, Determann R. Rationale and study design of provent—an international multicenter observational study on practice of ventilation in critically ill patients without ARDS. J Clin Trials. 2013;3:146. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ari A, Areabi H, Fink JB. Evaluation of aerosol generator devices at 3 locations in humidified and non-humidified circuits during adult mechanical ventilation. Respir Care. 2010;55(7):837–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ari A, Fink JB, Dhand R. Inhalation therapy in patients receiving mechanical ventilation: an update. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2012;25(6):319–332. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2011.0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dhand R. Aerosol delivery during mechanical ventilation: from basic techniques to new devices. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2008;21(1):45–60. doi: 10.1089/jamp.2007.0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bendstrup KE, Newhouse MT, Pedersen OF, Jensen JI. Characterization of heparin aerosols generated in jet and ultrasonic nebulizers. J Aerosol Med. 1999;12(1):17–25. doi: 10.1089/jam.1999.12.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ. 2010;340:c221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winkelmayer WC, Kurth T. Propensity scores: help or hype? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(7):1671–1673. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]