Abstract

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX) is among the few inherited neurometabolic disorders amenable to specific treatment. It is easily diagnosed using plasma cholestanol. We wished to delineate the natural history of the most common neurological and non-neurological symptoms in thirteen patients with CTX. Diarrhea almost always developed within the first year of life. Cataract and school difficulties usually occurred between 5 and 15 years of age preceding by years the onset of motor or psychiatric symptoms. The median age at diagnosis was 24.5 years old. It appears critical to raise awareness about CTX among paediatricians in order to initiate treatment before irreversible damage occurs.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13023-016-0419-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, Diarrhea, Cataract, Cerebellar ataxia, Cognitive dysfunction, Psychiatric symptoms

Introduction

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX) is a rare autosomal recessive sterols storage disorder caused by 27-sterol-hydroxylase deficiency due to CYP27A1 mutations resulting in an accumulation of cholestanol in blood and organs, mainly the central nervous system, eyes, tendons and vessels [1, 2]. With an estimated prevalence of 1/50,000 [3] but only about 300 patients reported, CTX remains too often under- or misdiagnosed while treatment is available. Patients typically manifest both systemic and neuropsychiatric symptoms of the disease. Systemic manifestations may include infantile cholestasis or liver dysfunction, juvenile cataract, Achilles tendon xanthomas, osteoporosis, premature arteriosclerosis and cardiovascular disease [1, 2, 4]. Neurological symptoms encompass cognitive delay, spastic paraplegia, cerebellar ataxia, peripheral neuropathy, bulbar palsy, epilepsy, movement disorders, dementia and psychiatric disturbances [1, 2, 4]. While these symptoms are well described, their natural history is not. More importantly, CTX is almost always diagnosed in adults whereas most of the initial symptoms occur in childhood and adolescence. We therefore describe the natural history of the most common neurological and non-neurological symptoms in thirteen patients with CTX in order to alert on the early symptoms of the disease.

Patients and methods

We collected retrospectively clinical, biochemical, imaging and electrophysiological data from thirteen genetically confirmed CTX patients followed at La Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital. In order to delineate the natural history of the disease, we selected only patients whose diagnosis was made in adolescence or adulthood. Values are expressed in mean ± SD and/or median. For the Kaplan-Meier analyses, we assumed that patients are determined to have CTX at birth. Therefore all time to event data (e.g. time to diarrhea, time to cataract) assumed that the initial time was the date of birth. The censoring time was the age at latest neurological exam. The symptoms were communicated via the caregiver or the patient directly. Each patient gave a written informed consent to participate in the study. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (CPPIdF6, La Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital).

Results

We describe four males and nine females with CTX belonging to ten families. Four patients were born from a consanguineous union (Additional file 1). All patients were Caucasian except two patients of Turkish origin. Six patients were compound heterozygous and five patients homozygous for CYP27A1 mutations. In two siblings, the second mutation was not identified despite very high levels of plasma cholestanol (Additional file 1). In three families, the diagnosis of the index case led to the diagnosis of a sibling. The mean and median age at diagnosis were 30.4 ± 14.9 years and 24.5 years (range: 14-55) respectively. The mean and median disease duration at the time of diagnosis were 26.2 ± 11.6 years and 21.5 years (range: 13.5–54.5) respectively.

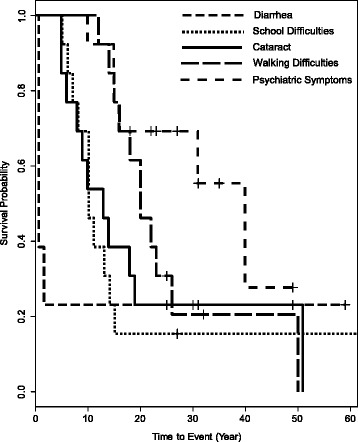

The natural history of our CTX cohort revealed that chronic diarrhea was very common, starting within the first year of life (Table 1, Fig. 1). None of our patients had a known history of infantile hepatic dysfunction. Cataract and school difficulties usually followed between 5 and 15 years of age (Additional file 1). Another 5–15 years later, most patients developed motor dysfunction leading to walking difficulties and/or psychiatric symptoms (Fig. 1, Additional file 1). Plasma cholestanol was markedly elevated in all patients with a mean of 64 ± 23 μmol/l (35–98 μmol/l, normal range: 2-10 μmol/l) (Additional file 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics in a cohort of thirteen patients with CTX

| Demographic | |||

| - Gender | Female: 9 | Male: 4 | |

| - Familial genetics | Consanguinity: 4 | Affected sibs: 6 | |

| Age of onset [median; mean ± SD; range] (years) | |||

| - Diarrhea | 10/13, neonatal | ||

| - School difficulties | 11/13 [10; 9.9 ± 3.2; 5–15] | ||

| - Cataract (age of surgery) | 11/13 [13; 15.4 ± 13.8; 5–54] | ||

| - Psychiatric symptoms | 6/13 [15.5; 21.2 ± 11.7; 10–40] | ||

| - Walking difficulties | 11/13 [20; 21.4 ± 10.3; 12–50] | ||

| Neurological examination | |||

| Age at examination [median; mean ± SD; range] (years) | 30; 33 ± 13.8 (18–60) | ||

| - Dysmetria | Yes: 7/13 | ||

| - Tandem | Unable: 5/13 | Abnormal: 7/13 | Normal: 1/13 |

| - LL spasticity | Yes: 6/13 | ||

| - UL spasticity | Yes: 0/13 | ||

| - LL reflexes (knee) | Increased: 6/13 | Absent: 3/13 | Normal: 4/13 |

| - LL reflexes (ankle) | Increased: 5/13 | Absent: 3/13 | Normal: 5/13 |

| - UL reflexes | Increased: 9/13 | Normal: 4/13 | |

| - Plantar reflexes | Upgoing: 7/13 | Flexor/Indifferent: 6/13 | |

| - Romberg | Positive: 3/12 | Negative: 9/12 | |

| - LL proprioception | Decreased: 10/11 | Normal: 1/11 | |

| - UL proprioception | Normal: 11/11 | ||

| Eye movements | |||

| - Pursuit | Saccadic: 8/13 | Normal: 5/13 | |

| - Saccades | Dysmetric: 7/13 | Normal: 6/13 | |

| Cognitive dysfunction | 13/13 | ||

| - Delayed cognition | 10/13 | ||

| - Dysexecutive/Decline | 12/13 | ||

| Paroxysmal manifestations | |||

| - Myoclonic dystonia | 7/13 | ||

| - Epilepsy | 1/13 | ||

| Osteoporosis | 4/13 | ||

| Tendon Xanthoma | 3/13 | ||

| Peripheral neuropathy | 10/13 - Axonal (4/10), Demyelinating (5/10), Mixed (1/10) | ||

| Brain MRI/MRS | |||

| - Global atrophy | 3/13 | ||

| - Periventricular T2 hyperintensities | 10/13 | ||

| - Increased choline peak (MRS) | 13/13 | ||

| - Dentate nuclei T2 hyperintensities | 12/13 | ||

| - Cerebellar atrophy | 7/13 | ||

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier analyses indicate the natural history of thirteen patients with CTX for time to diarrhea, cataract, school difficulties, walking difficulty and psychiatric symptoms

A detailed neurological evaluation was performed at a median age of 30 years (18–60). Except for two patients with no overt motor dysfunction, CTX patients presented mainly with cerebello-pyramidal (6/13), neuropathic (3/13), cerebellar (1/13) or pyramidal (1/13) dysfunction. Seven patients also displayed postural myoclonic jerks associated with dystonia, including six that were confirmed by electrophysiological recordings [5]. Cognitive functions were altered in all patients and a neuropathy was documented in ten patients (Table 1). On clinical examination, only 3/13 patients had clinical tendon xanthomas (Table 1). Four patients developed osteopenia but none experienced cardiac or pulmonary manifestations (Table 1). Typically, brain MRI showed T2-weighted hyperintensities of the dentate nuclei and brain MR spectroscopy identified an increased peak of choline in all patients (Table 1).

Discussion

We describe the natural history of 13 patients with CTX. Chronic diarrhea was the earliest symptom commonly observed in CTX but did not seem to be a main cause for consultation, possibly due to the absence of associated growth retardation [6, 7]. Nonetheless, paediatric gastroenterologists should search for CTX in the context of an early onset diarrhea, especially with a history of infantile hepatic dysfunction. Similarly, the diagnosis of a cataract in a child or an adolescent must lead to measure plasma cholestanol. In our cohort, cataract and school difficulties tended to occur at a similar age suggesting that visual difficulties may contribute to the early cognitive difficulties of some CTX patients. Years after the onset of diarrhea, cataract and/or school difficulties, many patients developed gait abnormalities primarily related to cerebellar and/or pyramidal dysfunction and combined with cognitive dysfunction. About half of our cohort also developed psychiatric symptoms. Tendon xanthomas were rarely found on clinical examination, which emphasizes that their absence should not delay the diagnosis of CTX [6]. Electromyography often revealed a peripheral neuropathy with either an axonal or a demyelinating pattern. Brain MRI also showed T2-weighted hyperintensities of the dentate nuclei and are suggestive of the diagnosis [8]. The increased peak of choline on MR spectroscopy might be useful to monitor response to therapy.

It has been shown that non-neurological and neurological manifestations can respond to chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) through decreased plasma cholestanol levels [1, 4, 9]. When initiated early, the therapeutic response to CDCA can be dramatic [10, 11]. Therefore, paediatricians must be at the forefront of diagnosing CTX in children with chronic diarrhea and/or cataract and/or learning difficulties. Indeed, such symptoms constitute an important therapeutic window to initiate treatment in patients with CTX before the onset of disabling motor and psychiatric symptoms.

Conclusion

Our work shows that CTX is almost always diagnosed in adults whereas key symptoms occur in childhood and adolescence. Treatment shall be initiated before the onset of disabling motor and psychiatric symptoms.

Consent for publication

Not applicable (manuscript contains no individual person’s data).

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Xuan Wang for statistical support and Sigma-Tau for an educational grant.

Funding sources for the study

None.

Abbreviations

- CDCA

chenodeoxycholic acid

- CTX

cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis

Additional file

Demographic, biochemical and genetic characteristics, and age of onset of key symptoms in a cohort of thirteen patients with CTX. (XLSX 10 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BD and FM were involved in conception and design of the research project, in analysis and interpretation of the data, and writing of the first draft of the manuscript. ER, FL and PC were involved in conception and design of the research project. BD, YN, FL, MdMA, PC and FM were involved in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the clinical, radiological and genetic data. YN, FL, MdMA, ER and PC were involved in revising this manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Federico A, Dotti MT. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: clinical manifestations, diagnostic criteria, pathogenesis and therapy. J Child Neurol. 2003;18:633–638. doi: 10.1177/08830738030180091001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verrips A, Hoefsloot LH, Steenbergen GCH, Theelen JP, Wevers RA, Gabreëls FJ, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic characteristics of patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Brain. 2000;123:908–909. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.5.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorincz MT, Rainier S, Thomas D, Fink JK. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: possible higher prevalence than previously recognized. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(9):1459–1463. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.9.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nie S, Chen G, Cao X, Zhang Y. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: a comprehensive review of pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:179. doi: 10.1186/s13023-014-0179-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lagarde J, Roze E, Apartis E, Pothalil D, Sedel F, Couvert P, et al. Myoclonus and dystonia in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Mov Disord. 2012;27(14):1805–1810. doi: 10.1002/mds.25206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verrips A, van Engelen BGM, Wevers RA, van Geel BM, Cruysberg JR, van den Heuvel LP, et al. Presence of diarrhea and absence of tendon xanthomas in patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:520–524. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mignarri A, Gallus GN, Dotti MT, Federico A. A suspicion index for early diagnosis and treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014;37(3):421–429. doi: 10.1007/s10545-013-9674-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berginer VM, Berginer J, Korczyn AD, Tadmor R. Magnetic resonance imaging in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: a prospective clinical and neuroradiological study. J Neurol Sci. 1994;122:102–108. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berginer VM, Salen G, Shefer S. Long-term treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with chenodeoxycholic acid. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1649–1652. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198412273112601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonnot O, Fraidakis MJ, Lucanto R, Chauvin D, Kelley N, Plaza M, et al. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis presenting with severe externalized disorder: improvement after one year of treatment with chenodeoxycholic Acid. CNS Spectr. 2010;15(4):231–236. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berginer VM, Gross B, Morad K, Kfir N, Morkos S, Aaref S, et al. Chronic diarrhea and juvenile cataracts: think cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis and treat. Pediatrics. 2009;123:143–147. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]