Abstract

Background:

Whether final kissing balloon (FKB) dilatation after one-stent implantation at left-main (LM) bifurcation site remains unclear. Therefore, this large sample and long-term follow-up study comparatively assessed the impact of FKB in patients with unprotected LM disease treated with one-stent strategy.

Methods:

Total 1528 consecutive patients underwent LM percutaneous coronary intervention in one center from January 2004 to December 2010 were enrolled; among them, 790 patients treated with one drug-eluting stent crossover LM to left anterior descending (LAD) with FKB (n = 230) or no FKB (n = 560) were comparatively analyzed. Primary outcome was the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events, defined as a composite of death, myocardial infarction (MI) and target vessel revascularization (TVR).

Results:

Overall, The prevalence of true bifurcation lesions, which included Medina classification (1,1,1), (1,0,1), or (0,1,1), was similar between-groups (non-FKB: 37.0% vs. FKB: 39.6%, P = 0.49). At mean 4 years follow-up, rates of major adverse cardiovascular events (non-FKB: 10.0% vs. FKB: 7.8%, P = 0.33), death, MI and TVR were not significantly different between-groups. In multivariate propensity-matched regression analysis, FKB was not an independent predictor of adverse outcomes.

Conclusions:

For patients treated with one-stent crossover LM to LAD, clinical outcomes appear similar between FKB and non-FKB strategy.

Keywords: Angioplasty, Balloon, Bifurcation, Percutaneous Coronary Angioplasty, Unprotected Left-main

INTRODUCTION

Randomized trials comparing simple and complex techniques for non-left-main (LM) coronary bifurcation disease demonstrated that provisional one-stent is easier and not inferior to two-stent technique.[1,2,3,4,5] Although the provisional one-stent approach is now regarded as standard technique for most non-LM bifurcation lesions,[6] three studies reached inconsistent conclusions on necessity of final kissing ballooning (FKB) after main vessel stenting,[7,8,9] and there are no studies on FKB in LM bifurcation lesions.[10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] So, whether FKB dilatation after one-stent implantation at LM bifurcation site remains unclear currently. Therefore, we conduct this long-term follow-up study to comparatively assess FKB impact in patients with unprotected left-main (UPLM) disease treated with one-stent strategy.

METHODS

Study population

Data from 1528 consecutive patients from a single center (FuWai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, China) undergoing LM percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) from January 2004 to December 2010 were prospectively collected. Among them, 790 patients treated with one drug-eluting stent (DES) crossover LM to left anterior descending (LAD) by FKB (n = 230) or no FKB (n = 560) were analyzed after exclusion of patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) within 24 h and cardiac shock. UPLM disease was defined as documented myocardial ischemia with ≥ 50% UPLM stenosis and no patent bypass graft to the LAD or left circumflex (LCX) arteries. The decision for UPLM PCI was based on consultation with both patients and surgeons in instances of patient refusal for surgery or comorbidity that posed excessive surgical risk.

Procedural details

At our center, it is common to perform provisional two-stent strategies if LCX ostium is severely jeopardized after one-stent crossover from LM to LAD that is, severe dissection or thrombosis in MI flow <3 grade or residual stenosis ≥80%. Otherwise, performing FKB was per treating physician's discretion. FKB were performed with noncompliant balloons; main vessel balloons had similar diameter while side branch balloons were usually smaller than vessels. Final kissing pressure was comparatively low (6–10 atm) after the sequential high-pressure dilatation (16–20 atm). Proximal optimization technique[21] with larger noncompliant balloon was often performed. LCX ostium was assessed mainly by angiography, some by intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), and none by fractional flow reserve (FFR) because of its unavailability during the study period.

Before the procedure, all patients received aspirin, 300 mg daily, and a 300 mg loading dose of clopidogrel was given at least 1-day before the procedure. During the procedure, unfractionated heparin (100 U/kg) was administered to all patients, and use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was per operator's judgment. After the procedure, aspirin was prescribed at a dose of 300 mg daily for 3 months, followed by 100 mg daily indefinitely; clopidogrel 75 mg daily was prescribed for at least 1-year.

Patient follow-up

All patients were evaluated by clinic visit or by phone at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months and annually thereafter. Patients were advised to return for coronary angiography if clinically indicated by symptoms or documentation of myocardial ischemia.

Study outcomes

Angiographic success was defined as residual stenosis of <30% by visual estimation in the presence of TIMI flow grade 3. MI was diagnosed by electrocardiographic changes and/or a rise and fall of the creatine kinase-myocardial band fraction in the presence of ischemic symptoms. New development of pathological Q-waves in two contiguous leads was defined as Q-wave MI; and in the absence of pathological Q-waves, an elevation in creatine kinase-myocardial band level >3 times the upper limit of normal was defined as non-Q-wave MI. Target vessel revascularization (TVR) was defined as repeated revascularization by PCI or surgery of the target vessel. The composite of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) was defined as the occurrence of death, MI, and TVR in-hospital and during follow-up. Stent thrombosis was defined on the basis of Academic Research Consortium definitions according to timing of presentation as early (0–30 days), late (31–360 days), or very late (>360 days) and to the level of certainty as definite, probable and possible.[22]

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are described as mean (standard deviation) or median (Q1, Q3), and Student's t-tests or Wilcoxon test were performed for between-group comparisons as appropriate. Categorical variables are shown as percentages and compared by Chi-square test.

Propensity score matching analysis was performed to minimize potential bias secondary to between-group imbalance. Propensity scores were calculated using a logistic model (C-statistics: 0.88) with inclusion of the following variables: Sex, age, body mass index, prior MI, prior PCI, previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), diabetes mellitus, hypertension, unstable angina, hyperlipidemia, family history of coronary artery disease, prior stroke, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), transradial approach, stent diameter, stent length, use of IVUS, and baseline SYNTAX score. Patients were matched 1:1 using the greedy 8-to-1 digit matching algorithm without replacement. Kaplan–Meier product limit methods were used to calculate survival curves for outcomes by group and log-rank tests were used to examine differences between-groups. Hazard ratios were estimated by the Cox proportional hazard regression model after controlling for the abovementioned confounders. All tests were two-sided and conducted at the 0.05 level.

RESULTS

Baseline patient characteristics

The two groups were matched for all clinical characteristics except for a higher prevalence of prior CABG and a lower LVEF in the non-FKB group [Table 1]. Lesion and procedural characteristics are presented in Table 2. The patients enrolled in this study were at low-intermediate SYNTAX score (non-FKB: 25 ± 7 vs. FKB: 23 ± 5, P = 0.01), and clinical SYNTAX scores were similar between-groups (non-FKB: 31 ± 23 vs. FKB: 28 ± 20, P = 0.15). The prevalence of true bifurcation lesions, which included Medina classification (1,1,1), (1,0,1), or (0,1,1), was similar between-groups (non-FKB: 37.0% vs. FKB: 39.6%, P = 0.49). Compared with FKB patients, non-FKB patients more frequently were treated with transradial approach. Second-generation DESs including Xience V and Endeavor Sprint or Endeavor Resolute DES were commonly implanted in non-FKB than FKB patients (24.3% vs. 12.6%, P < 0.01). Procedure time was longer and more contrast was used in the FKB group. LM bifurcation angiographic success rate was significantly lower in non-FKB patients (68.9% vs. 83.0% %, P < 0.01), mainly secondary to residual stenosis at LCX ostium.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics

| Items | Total population | Propensity-matched population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-FKB (n = 560) | FKB (n = 230) | P | Non-FKB (n = 392) | FKB (n = 196) | P | |

| Age, years | 59.7 ± 10.5 | 59.6 ± 10.8 | 0.95 | 59.68 ± 10.39 | 59.80 ± 10.62 | 0.89 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 446 (79.6) | 184 (80.0) | 0.91 | 308 (78.6) | 157 (80.1) | 0.65 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.9 ± 3.2 | 25.8 ± 2.9 | 0.49 | 25.9 ± 3.1 | 25.7 ± 2.9 | 0.42 |

| Diabetes mellitus*, n (%) | 124 (22.1) | 52 (22.6) | 0.89 | 88 (22.4) | 42 (21.4) | 0.78 |

| Hypertension*, n (%) | 296 (52.9) | 128 (55.7) | 0.47 | 214 (54.6) | 104 (53.1) | 0.73 |

| Hyperlipidemia*, n (%) | 286 (51.1) | 103 (44.8) | 0.11 | 204 (52.0) | 94 (48.0) | 0.33 |

| Prior MI, n (%) | 137 (24.5) | 57 (24.8) | 0.93 | 93 (23.7) | 48 (24.5) | 0.84 |

| Prior PCI, n (%) | 109 (19.5) | 58 (25.2) | 0.08 | 81 (20.7) | 42 (21.4) | 0.82 |

| Prior CABG, n (%) | 17 (3.0) | 2 (0.9) | 0.05 | 3 (0.8) | 2 (1.0) | 0.75 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 159 (28.4) | 67 (29.1) | 0.84 | 113 (28.8) | 56 (28.6) | 0.95 |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 61 (10.9) | 34 (14.8) | 0.13 | 43 (11.0) | 21 (10.7) | 0.92 |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 35 (6.3) | 16 (7.0) | 0.72 | 25 (6.4) | 15 (7.7) | 0.56 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 32 (5.7) | 7 (3.0) | 0.10 | 17 (4.3) | 7 (3.6) | 0.66 |

| Chronic lung disease, n (%) | 4 (0.7) | 4 (1.7) | 0.10 | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.22 |

| Unstable angina, n (%) | 345 (61.6) | 145 (63.0) | 0.71 | 247 (63.0) | 125 (63.8) | 0.85 |

| LVEF, % | 62.6 ± 7.6 | 63.8 ± 7.0 | 0.04 | 62.7 ± 7.2 | 63.0 ± 6.8 | 0.62 |

| Creatinine clearance rate, ml/min | 81.1 ± 18.5 | 81.3 ± 20.8 | 0.88 | 81.4 ± 19.7 | 81.3 ± 21.3 | 0.98 |

Data represented as n (%) or mean ± SD. *Defined as requiring medical therapy. MI: Myocardial infarction; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: Coronary artery disease; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; SD: Standard deviation; FKB: Final kissing balloon; BMI: Body mass index.

Table 2.

Lesion and procedural characteristics and outcomes

| Items | Total population | Propensity-matched population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-FKB (n = 560) | FKB (n = 230) | P | Non-FKB (n = 392) | FKB (n = 196) | P | |

| Baseline SYNTAX score | 24.6 ± 6.5 | 23.4 ± 5.3 | 0.01 | 23.9 ± 5.9 | 23.8 ± 5.4 | 0.89 |

| Clinical SYNTAX score | 30.6 ± 22.5 | 28.3 ± 19.6 | 0.15 | 30.5 ± 22.9 | 29.3 ± 19.7 | 0.53 |

| Medina classification, n (%) | ||||||

| 1,1,1 | 140 (25.0) | 59 (25.7) | 0.14 | 77 (21.9) | 52 (28.3) | 0.19 |

| 1,0,1 | 34 (6.1) | 17 (7.4) | 19 (5.4) | 15 (8.2) | ||

| 0,1,1 | 33 (5.9) | 15 (6.5) | 4 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | ||

| 1,0,0 | 51 (9.1) | 11 (4.8) | 12 (3.4) | 6 (3.3) | ||

| 1,1,0 | 222 (39.6) | 81 (35.2) | 165 (42.4) | 73 (37.2) | ||

| 0,1,0 | 66 (11.8) | 41 (17.8) | 45 (11.5) | 37 (18.9) | ||

| 0,0,1 | 14 (2.50) | 6 (2.61) | 6 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) | ||

| True bifurcation*, n (%) | 207 (37.0) | 91 (39.6) | 0.49 | 142 (36.2) | 75 (38.3) | 0.63 |

| Restenotic lesion, n (%) | 13 (2.3) | 8 (3.5) | 0.37 | 8 (2.0) | 6 (3.1) | 0.45 |

| Transradial approach, n (%) | 351 (62.7) | 121 (52.6) | 0.01 | 153 (39.0) | 79 (40.3) | 0.75 |

| Stent/patient | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 0.10 | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 0.96 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.35 ± 0.39 | 3.39 ± 0.39 | 0.11 | 3.36 ± 0.39 | 3.39 ± 0.39 | 0.36 |

| Stent length, mm | 33 ± 19 | 30 ± 17 | 0.04 | 33 ± 19 | 30 ± 16 | 0.12 |

| DES type, n (%) | ||||||

| Sirolimus-eluting | 347 (62.0) | 160 (69.6) | <0.01 | 237 (60.5) | 141 (71.9) | 0.01 |

| Paclitaxel-eluting | 77 (13.8) | 41 (17.8) | 62 (15.8) | 31 (15.8) | ||

| Second-generation DES† | 136 (24.3) | 29 (12.6) | 93 (23.7) | 24 (12.2) | ||

| IVUS, n (%) | 177 (31.6) | 79 (34.3) | 0.46 | 126 (32.1) | 63 (32.1) | 1.00 |

| Hemodynamic support with IABP, n (%) | 27 (4.8) | 12 (5.2) | 0.81 | 19 (4.9) | 11 (5.6) | 0.68 |

| Procedure time, min | 46 ± 32 | 61 ± 36 | <0.01 | 45 ± 31 | 63 ± 37 | <0.01 |

| Contrast volume, ml | 232 ± 83 | 266 ± 82 | <0.01 | 234 ± 79 | 265 ± 78 | <0.01 |

| LM bifurcation angiographic success, n (%) | 386 (68.9) | 191 (83.0) | <0.01 | 263 (67.1) | 158 (81.1) | <0.01 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± SD. *True bifurcation included Medina classification (1,1,1; 1,0,1; 0,1,1); †Second-generation DES included: Xience V and Endeavor Sprint or Endeavor Resolute DES. DES: Drug-eluting stent; IVUS: Intravascular ultrasound; IABP: Intra-aortic balloon pump; LM: Left-main; FKB: Final kissing balloon; SD: Standard deviation.

In-hospital and long-term outcomes

During hospitalization, no differences were observed in the rates of death, MI and TVR between-groups; likewise for MACE rate (non-FKB: 2.7% vs. FKB: 0.9%, P = 0.17) [Table 3].

Table 3.

In-hospital and late clinical outcomes

| Items | Total population | Propensity-matched population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-FKB (n = 560) | FKB (n = 230) | P | Non-FKB (n = 392) | FKB (n = 196) | P | |

| In-hospital outcomes, n (%) | ||||||

| MACE | 15 (2.7) | 2 (0.9) | 0.17 | 9 (2.3) | 2 (1.0) | 0.30 |

| Death | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 0.63 | 3 (0.8) | 2 (1.0) | 0.75 |

| Cardiac death | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.9) | 0.58 | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0.49 |

| MI | 13 (2.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0.08 | 8 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0.20 |

| TVR | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| TLR | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Late clinical outcomes | ||||||

| Follow-up duration, years | 4.1 ± 1.9 | 4.8 ± 2.0 | <0.01 | 4.0 ± 1.8 | 4.7 ± 2.0 | <0.01 |

| MACE, n (%) | 56 (10.0) | 18 (7.8) | 0.33 | 40 (10.2) | 15 (7.7) | 0.34 |

| Death, n (%) | 26 (4.6) | 11 (4.8) | 0.93 | 19 (4.8) | 9 (4.6) | 0.89 |

| Cardiac death, n (%) | 17 (3.0) | 8 (3.5) | 0.75 | 11 (2.8) | 7 (3.6) | 0.62 |

| MI, n (%) | 42 (7.5) | 13 (5.7) | 0.34 | 27 (6.9) | 11 (5.6) | 0.57 |

| TVR, n (%) | 41 (7.3) | 12 (5.2) | 0.27 | 26 (6.6) | 10 (5.1) | 0.48 |

| TLR, n (%) | 28 (5.0) | 8 (3.5) | 0.34 | 20 (5.1) | 7 (3.6) | 0.42 |

| Stent thrombosis*, n (%) | 12 (2.1) | 8 (3.5) | 0.29 | 8 (2.0) | 7 (3.6) | 0.28 |

| Early | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.9) | 0.58 | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0.49 |

| Late | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 1.00 | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) | 0.73 |

| Very late | 7 (1.3) | 5 (2.2) | 0.35 | 3 (0.8) | 4 (2.0) | 0.20 |

*Including definite, probable stent thrombosis according to ARC definition. MACE: Major adverse cardiac events; MI: Myocardial infarction; TVR: Target vessel revascularization; TLR: Target lesion revascularization; FKB: Final kissing balloon; NA: Nonavailable; ARC: Academic Research Consortium.

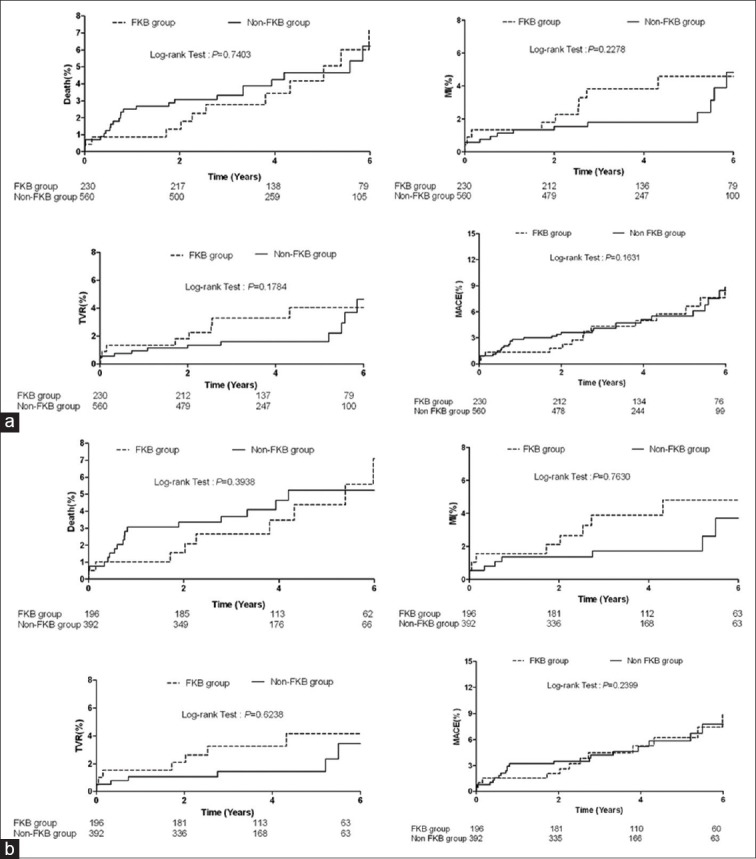

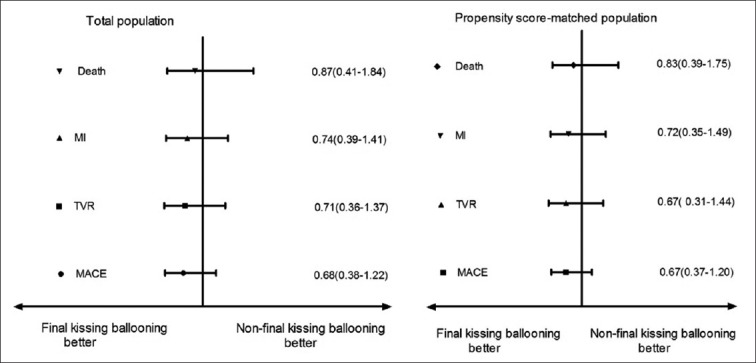

Clinical follow-up was completed for all patients, and follow-up duration was longer for FKB patients (non-FKB: 4.1 ± 1.9 years vs. FKB: 4.8 ± 2.0 years, P < 0.01). Rates of death, MI and TVR were not significantly different between-groups; likewise for MACE rate (non-FKB: 10.0% vs. FKB: 7.8%, P = 0.33) [Table 3]. Definite and probable stent thrombosis rates were also similar overall and at different time intervals (early, late, very late) between-groups (overall, non-FKB: 2.1% vs. FKB: 3.5%, P = 0.29). There were no between-group differences in Kaplan–Meier estimated rates of MACE or its individual components [Figure 1a]. Furthermore, in multivariate regression analysis, FKB was not predictive of MACEs [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

(a) Kaplan–Meier estimates of major cardiovascular events for overall patients treated with final kissing balloon (FKB) and non-FKB strategies. MACE: Major adverse cardiac events; MI: Myocardial infarction; TVR: Target vessel revascularization; (b) Kaplan–Meier estimates of major cardiovascular events for propensity-matched patients treated with final kissing balloon (FKB) and non-FKB strategies; MACE: Major adverse cardiac events; MI: Myocardial infarction; TVR: Target vessel revascularization.

Figure 2.

Multivariable analysis of major adverse events multivariable matched propensity analysis demonstrates no significant difference in incidence rates of individual and composite clinical outcomes between final kissing balloon (FKB) and non-FKB patients. MACE: Major adverse cardiac events; MI: Myocardial infarction; TVR: Target vessel revascularization.

Propensity score: Matched analysis

After performing propensity score matching, a total of 196 matched pairs (392 patients from the non-FKB group and 196 patients from the FKB group) were generated. There were no significant differences in baseline clinical, lesion and procedural characteristics for the propensity-matched subjects except for the rate of second-generation DES [Tables 1 and 2]. In this adjusted model, MACE and its individual components did not differ significantly between-groups [Table 3 and Figure 1b], and FKB was not predictive of MACEs in multivariate regression analysis [Figure 2].

DISCUSSION

The major finding of this relatively large study evaluating FKB impact on long-term outcomes after one-stent at LM bifurcation site was that one-stent crossover LM to LAD without FKB was associated with similar in-hospital and long-term clinical outcomes to that with FKB.

To date, there have been only three studies assessing FKB impact in patients with bifurcation lesions treated with one-stent strategy.[7,8,9] The randomized Nordic III study,[7] which recruited 477 patients, indicated that there was neither advantage nor disadvantage to kissing balloon inflations within 6 months follow-up. The study conducted by Gwon et al. enrolled a total of 1065 consecutive patients in the COBIS registry,[8] one-third of whom underwent FKB dilatation. During a mean follow-up of 22 months, the main vessel re-intervention rate was significantly higher in the kissing balloon group (9.1%) than the nonkissing balloon group (3.4%). The study, therefore, concluded that in patients treated with one-stent technique for bifurcation lesions, FKB after main vessel stenting may be harmful due to increased TLR. Another study conducted by Yamawaki et al. was a sub-analysis of the TAXUS Japan Postmarket Surveillance Study,[9] comparing 132 FKB patients versus 121 non-FKB patients with 3 years follow-up. The study concluded that in a one-stent approach, FKB was associated with worse angiographic outcomes in the main vessel and did not demonstrate any clinical benefit over the long-term follow-up period. It was noted that these studies focused on non-LM bifurcation studies, and the sample size of Yamawaki et al.'s study was too small, which could not evaluate low incidence clinical events of different approaches. Although Gwon et al.'s and the current analysis are based on registry studies reflecting real world practice, obvious higher prevalence of true bifurcation lesions was found in the former study (65.9% vs. 37.7%). This may reflect operators’ preference of two-over one-stent techniques for LM than non-LM true bifurcation lesions to avoid the dire consequences of losing a large side branch such as LCX or LAD.

Theoretically, there are several advantages for FKB after one-stent crossover LM to LAD. This technique scaffolds the origin of the LCX, retains access to LCX, and optimizes expansion of the proximal part of the stent. This study showed higher angiographic success rate for FKB group (83.0% vs. 68.9%; P < 0.01), mainly secondary to less stenosis of LCX after FKB. However, in-hospital and long-term outcomes were similar between-groups even after propensity score matched analysis that is, the immediate better angiographic result did not translate into better long-term clinical outcomes. However, because this study only enrolled patients with mild to intermediate stenosis at LCX ostium (<80% in diameter) without functional assessment by FFR,[23] it remains undefined if FKB would result in better clinical outcomes in patients with severe stenosis at LCX ostium (≥80% in diameter). Nordic III study showed similar results to those of this study,[7] however 6 months’ follow-up in Nordic III was not long enough particularly because the first-generation DES used exhibits a restenotic catch-up phenomenon.[24]

FKB potentially may be associated with complications including main vessel stent deformation, DES polymer disruption caused by side branch ballooning and main vessel proximal part injury secondary to over-dilatation. In Gwon et al.'s study, FKB increased TLR rate,[8] perhaps secondary to harmful effects of FKB; however, no information was provided on balloons and FKB pressure. Presumedly, bigger than vessel size and semi-compliant balloons and higher pressure FKB would increase the severity of all those harmful effects. In this study, however, FKB were noncompliant and main vessels balloons were similar in diameter to the vessels while side branch balloons were usually smaller than vessel size; final kissing pressure also was comparatively low (6–10 atm) after sequential high pressure dilatation (16–20 atm), and proximal optimization technique[21] with bigger noncompliant balloon was often performed. All the latter features might minimize damage and deformation of the main vessel proximal part. Moreover, higher TLR rate in FKB group in Gwon et al.'s study might be secondary to higher prevalence of true bifurcations (74.8% vs. 62.0%, P < 0.001), in contrast to this study, in which the prevalence of true bifurcation lesions was similar between-groups (non-FKB: 37.0% vs. FKB: 39.6%, P = 0.49).

Although patients with FKB had similar clinical outcomes as those without FKB, this study also showed that FKB more often required higher volume of contrast, longer procedure time and more balloons, indicating that FKB cases were technically more challenging and required more resources than non-FKB ones.

The major limitation of this study is its nonrandomized design in which operator bias and unmeasured confounders may preclude any definitive conclusion. Because patients with bail-out side branch stenting were excluded from this analysis, study conclusions do not apply to all LM bifurcation lesions. In addition, the study did not include qualitative comparative analysis data although it would have provided more detailed information, we did not think it would affect result interpretation.

In conclusion, for patients treated with one-stent crossover LM to LAD, clinical outcomes appear similar between FKB and non-FKB strategy.

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Min Chen

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colombo A, Bramucci E, Saccà S, Violini R, Lettieri C, Zanini R, et al. Randomized study of the crush technique versus provisional side-branch stenting in true coronary bifurcations: The CACTUS (Coronary Bifurcations: Application of the Crushing Technique Using Sirolimus-Eluting Stents) Study. Circulation. 2009;119:71–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.808402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steigen TK, Maeng M, Wiseth R, Erglis A, Kumsars I, Narbute I, et al. Randomized study on simple versus complex stenting of coronary artery bifurcation lesions: The Nordic bifurcation study. Circulation. 2006;114:1955–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferenc M, Gick M, Kienzle RP, Bestehorn HP, Werner KD, Comberg T, et al. Randomized trial on routine vs. provisional T-stenting in the treatment of de novo coronary bifurcation lesions. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2859–67. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hildick-Smith D, de Belder AJ, Cooter N, Curzen NP, Clayton TC, Oldroyd KG, et al. Randomized trial of simple versus complex drug-eluting stenting for bifurcation lesions: The British Bifurcation Coronary Study: Old, new, and evolving strategies. Circulation. 2010;121:1235–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.888297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen SL, Santoso T, Zhang JJ, Ye F, Xu YW, Fu Q, et al. A randomized clinical study comparing double kissing crush with provisional stenting for treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions: Results from the DKCRUSH-II (Double Kissing Crush versus Provisional Stenting Technique for Treatment of Coronary Bifurcation Lesions) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:914–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latib A, Colombo A, Sangiorgi GM. Bifurcation stenting: Current strategies and new devices. Heart. 2009;95:495–504. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.150391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niemelä M, Kervinen K, Erglis A, Holm NR, Maeng M, Christiansen EH, et al. Randomized comparison of final kissing balloon dilatation versus no final kissing balloon dilatation in patients with coronary bifurcation lesions treated with main vessel stenting: The Nordic-Baltic Bifurcation Study III. Circulation. 2011;123:79–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.966879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gwon HC, Hahn JY, Koo BK, Song YB, Choi SH, Choi JH, et al. Final kissing ballooning and long-term clinical outcomes in coronary bifurcation lesions treated with 1-stent technique: Results from the COBIS registry. Heart. 2012;98:225–31. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamawaki M, Muramatsu T, Kozuma K, Ito Y, Kawaguchi R, Kotani J, et al. Long-term clinical outcome of a single stent approach with and without a final kissing balloon technique for coronary bifurcation. Circ J. 2014;78:110–21. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YH, Park SW, Hong MK, Park DW, Park KM, Lee BK, et al. Comparison of simple and complex stenting techniques in the treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery bifurcation stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1597–601. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim WJ, Kim YH, Park DW, Yun SC, Lee JY, Kang SJ, et al. Comparison of single- versus two-stent techniques in treatment of unprotected left main coronary bifurcation disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77:775–82. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmerini T, Marzocchi A, Tamburino C, Sheiban I, Margheri M, Vecchi G, et al. Impact of bifurcation technique on 2-year clinical outcomes in 773 patients with distal unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis treated with drug-eluting stents. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:185–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.800631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price MJ, Cristea E, Sawhney N, Kao JA, Moses JW, Leon MB, et al. Serial angiographic follow-up of sirolimus-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:871–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaquerizo B, Lefèvre T, Darremont O, Silvestri M, Louvard Y, Leymarie JL, et al. Unprotected left main stenting in the real world: Two-year outcomes of the French left main taxus registry. Circulation. 2009;119:2349–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.804930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng W, Lundstrom R, McNulty E. Impact of stenting technique and bifurcation anatomy on long-term outcomes of PCI for distal unprotected left main coronary disease. J Invasive Cardiol. 2013;25:23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toyofuku M, Kimura T, Morimoto T, Hayashi Y, Ueda H, Kawai K, et al. Three-year outcomes after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation for unprotected left main coronary artery disease: Insights from the j-Cypher registry. Circulation. 2009;120:1866–74. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.873349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang K, Koh YS, Jeong SH, Lee JM, Her SH, Park HJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting for unprotected left main coronary bifurcation disease in the drug-eluting stent era. Heart. 2012;98:799–805. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmerini T, Sangiorgi D, Marzocchi A, Tamburino C, Sheiban I, Margheri M, et al. Ostial and midshaft lesions vs. bifurcation lesions in 1111 patients with unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis treated with drug-eluting stents: Results of the survey from the Italian Society of Invasive Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2087–94. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valgimigli M, Malagutti P, Rodriguez Granillo GA, Tsuchida K, Garcia-Garcia HM, van Mieghem CA, et al. Single-vessel versus bifurcation stenting for the treatment of distal left main coronary artery disease in the drug-eluting stenting era. Clinical and angiographic insights into the Rapamycin-Eluting Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (RESEARCH) and Taxus-Stent Evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (T-SEARCH) registries. Am Heart J. 2006;152:896–902. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen SL, Zhang Y, Xu B, Ye F, Zhang J, Tian N, et al. Five-year clinical follow-up of unprotected left main bifurcation lesion stenting: One-stent versus two-stent techniques versus double-kissing crush technique. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:803–14. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I7A123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hildick-Smith D, Lassen JF, Albiero R, Lefevre T, Darremont O, Pan M, et al. Consensus from the 5th European Bifurcation Club meeting. EuroIntervention. 2010;6:34–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: A case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koo BK, Park KW, Kang HJ, Cho YS, Chung WY, Youn TJ, et al. Physiological evaluation of the provisional side-branch intervention strategy for bifurcation lesions using fractional flow reserve. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:726–32. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park KW, Kim CH, Lee HY, Kang HJ, Koo BK, Oh BH, et al. Does “late catch-up” exist in drug-eluting stents: Insights from a serial quantitative coronary angiography analysis of sirolimus versus paclitaxel-eluting stents. Am Heart J. 2010;159:446–53.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]