Abstract

Background:

During the last decade, the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in human patients has increased. Carbapenemase-producing bacteria are usually multidrug resistant. Therefore, early recognition of carbapenemase producers is critical to prevent their spread.

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to develop the primers for single and/or multiplex PCR amplification assays for simultaneous identification of class A, class B, and class D carbapenem hydrolyzing β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae and then to evaluate their efficiency.

Materials and Methods:

The reference sequences of all genes encoding carbapenemases were downloaded from GenBank. Primers were designed to amplify the following 11 genes: blaKPC, blaOXA, blaVIM, blaNDM, blaIMP, blaSME, blaIMI, blaGES, blaGIM, blaDIM and blaCMY. PCR conditions were tested to amplify fragments of different sizes. Two multiplex PCR sets were created for the detection of clinically important carbapenemases. The third set of primers was included for detection of all known carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae. They were evaluated using six reference strains and nine clinical isolates.

Results:

Using optimized conditions, all carbapenemase-positive controls yielded predicted amplicon sizes and confirmed the specificity of the primers in single and multiplex PCR.

Conclusions:

We have reported here a reliable method, composed of single and multiplex PCR assays, for screening all clinically known carbapenemases. Primers tested in silico and in vitro may distinguish carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and could assist in combating the spread of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae.

Keywords: Enterobacteriaceae, Drug Resistance, Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction, Carbapenems

1. Background

Carbapenems are considered to be one of the few drugs that are useful for the treatment of infections caused by multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria. The emergence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae is a serious public health concern due to the large spectrum of resistant genes and the lack of therapeutic options (1, 2). Therefore, there is an ongoing effort in the development of earlier and more sensitive detection of carbapenemase producers. With regard to carbapenem resistance, it must be taken into account that carbapenemase-producing bacteria may sometimes exhibit only a slight increase of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values for carbapenems, which reflects the importance of molecular approaches to phenotypic tests (3).

Enterobacteriaceae, such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter spp., commonly cause nosocomial pneumonias and infections in the bloodstream, urinary tract and intra-abdominal region (4, 5). Carbapenem resistance mechanisms in Enterobacteriaceae include the following: (i) enzymatic inactivation by β-lactamases; (ii) modification of outer-membrane proteins (porins) and penicillin-binding proteins; and (iii) efflux pumps (6). Carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases belonging to molecular class A (e.g., KPC, GES, IMI, SME), class B (e.g. IMP, VIM, NDM, GIM) and class D (e.g. OXA-23 and OXA-48), are the main source of antibiotic resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. Genes encoding these types of carbapenemases are extensively reported among E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates from many European countries (1).

The carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamase OXA-48 has been identified in a K. pneumoniae isolate from Europe (7, 8), OXA-23 in Proteus mirabilis from France (9), OXA-162 in K. pneumoniae isolates from Hungary (10), OXA-181 in K. pneumoniae from Romania (11) and Citrobacter freundii from France (12), OXA-232 in K. pneumoniae from France (13) and OXA-244 and 245, both in K. pneumoniae from Spain (14). Additionally, OXA-247 was first described in K. pneumoniae in Argentina (15). Recently, blaOXA-51-like, blaOXA-58 and blaDIM-1 carbapenemase genes have been found in a large variety of enterobacterial species (16). Further, the presence of carbapenemases and extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) were also described: (i) blaTEM-1, blaSHV-11, blaCTX-M-15 and blaOXA-9 genes were present in the K. pneumoniae isolates harboring blaOXA-48; (ii) blaTEM-1 and blaOXA-1 genes were found in E. coli harboring blaOXA-162 and blaOXA-48; (iii) blaSHV-5 in C. freundii harboring blaOXA-162; and (iv) blaTEM-1 and blaCTX-M-15 in Enterobacter cloacae carrying blaOXA-48 (17).

Moreover, E. coli and K. pneumoniae clinical isolates producing CTX-M-2 and CTX-M-92 and a K. pneumoniae isolate with CTX-M-3 were detected, and each had the OXA-2 type beta-lactamase (18). In addition, KPC-2 and TEM-1 enzymes were identified in K. pneumoniae isolates, and VIM-1 and TEM-1 in P. mirabilis, both of which were positive for blaOXA-10 (19). In this context, a recent study has demonstrated that OXA-2 and OXA-10 are in fact carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D beta-lactamases (CHDLs), also called oxacillinases (OXA) (20). Interestingly, development of carbapenem resistance in CTX-M-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae has been reported (21, 22). Furthermore, it has been reported that CMY-2 β-lactamase plays a role in carbapenem resistance ("trapping" of meropenem) (23).

The rates of hydrolysis by OXA-type carbapenemases are weak. However, genes encoding OXA overcome this deficiency by possessing efficient promoters, leading to their overexpression and to increased carbapenem resistance (24). Thus, rapid and useful detection methods are important for the implementation of appropriate infection control measures to prevent the further spread of ESBLs and carbapenemases.

2. Objectives

The aim of the present study was to develop the primers for single and/or multiplex PCR amplification assays for identification of all known genes that confer carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae and evaluate the amplification efficiency of the primers.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Bacterial Isolates

Fifteen carbapenemase-producing strains were used as positive controls for optimizing the multiplex PCR assay; six reference strains and nine clinical isolates. The reference strains used were: (i) IMP-type (NCTC 13476), producing E. coli; (ii) KPC-3 positive K. pneumoniae (NCTC 13438); (iii) NDM-1 positive K. pneumoniae (NCTC 13443); (iv) VIM-10 positive Pseudomonas aeruginosa (NCTC 13437); (v) OXA-23 positive Acinetobacter baumannii (NCTC 13301); and (vi) OXA-48 positive K. pneumoniae (NCTC 13442). The clinical isolates were: (i–v) K. pneumoniae that produce VIM (V602B), KPC-2 (V117), KPC-3 (V514) and KPC (V601, V646); (vi–viii) P. aeruginosa-producing IMP (V7424) and VIM (V109, V7393); and (ix) NDM-1 positive A. baumannii (V509). All the clinical strains were provided by Ing. J. Hrabák, Ph.D. from the Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital in Plzen, Charles University in Prague, Plzen, Czech Republic.

3.2. Design of Group-Specific Primers for Single and Multiplex PCR Assays

Two multiplex PCRs were designed in this study: a blaKPC/blaOXA-48-like/blaVIM multiplex PCR and a blaNDM-1/blaIMP variants/blaOXA-23-like mutliplex PCR. The sequences of genes that encode carbapenemases (KPC, VIM, IMP, SME, IMI, GES, NDM, OXA) so far described (http://www.lahey.org/studies/; last accessed February 2015) were downloaded from the GenBank databases and were aligned using Geneious Pro 4.8.5 (Biomatters Ltd, Newark, NJ, USA) to identify highly homologous regions suitable for designing primers. Two sets of primers were tested against reference standard strains, as well as clinical isolates, in a single PCR reaction and then in a multiplex format. These reference strains included NCTC 13476, NCTC 13438, NCTC 13443, NCTC 13437, NCTC 13301 and NCTC 13442. Representative V602B, V117, V514, V601, V646, V7424, V109, V7393 and V509 were used as clinical isolates. Further, eleven pairs of primers were designed but not tested. The primer sequences, concentrations and calculated lengths of the corresponding amplicons are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Sequences of Primers Used for Single and Multiplex PCR for Detection of Genes Encoding Carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae.

| PCR Name | Targeted Gene | Primer Name | Sequence (5' to 3' Direction) a | Length (Bases) | Amplicon Size, bp | TM in °C | Primer CONCENTRATION, pmol/µL | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex I KPC, OXA and VIM | blaKPC type | Forward | TGTTGCTGAAGGAGTTGGGC | 20 | 340 | 56 | 15 pmol | This study |

| Reverse | ACGACGGCATAGTCATTTGC | 20 | ||||||

| blaOXA-48-like including OXA-199 and OXA-370 | Forward | AACGGGCGAACCAAGCATTTT | 21 | 585 or 597 | 15 pmol | This study | ||

| Reverse | TGAGCACTTCTTTTGTGATGGCT | 23 | ||||||

| blaVIM type | Forward | CGCGGAGATTGARAAGCAAA | 20 | 247 | 15 pmol | This study | ||

| Reverse | CGCAGCACCRGGATAGAARA | 20 | ||||||

| Multiplex II NDM, IMP and OXA | bla NDM-1 | Forward | TAAAATACCTTGAGCGGGC | 19 | 439 | 52 | 15 pmol | This study |

| Reverse | AAATGGAAACTGGCGACC | 18 | ||||||

| blaIMP variants except, IMP-3, IMP-16, IMP-27, IMP-31, IMP-34 and IMP-35 | Forward | GAGTGGCTTAATTCTCRATC | 20 | 183 | 15 pmol | Monteiro et al., 2012 (25) | ||

| Reverse | CCAAACYACTASGTTATCT | 19 | Ellington et al., 2007 (26) | |||||

| bla OXA-23-like | Forward | GTGGTTGCTTCTCTTTTTCT | 20 | 736 | 15 pmol | This study | ||

| Reverse | ATTTCTGACCGCATTTCCAT | 20 | ||||||

| PCR/Multiplex b | bla SME(1-5) | Forward | TATGGAACGATTTCTTGGCG | 20 | 300 | 56 | This study | |

| Reverse | CTCCCAGTTTTGTCACCTAC | 20 | 58 | |||||

| bla IMI type | Forward | CTACGCTTTAGACACTGGC | 19 | 481 | 57 | This study | ||

| Reverse | AGGTTTCCTTTTCACGCTCA | 20 | 56 | |||||

| bla IMP-27 | Forward | AAAGGCACTGTTTCCTCACA | 20 | 169 | 56 | This study | ||

| Reverse | TCGCCAGCCAATAACTAACC | 20 | 58 | |||||

| bla NDM(2-10, 12) | Forward | ATGACCAGACCGCCCAGAT | 19 | 380 | 60 | This study | ||

| Reverse | GAGATTGCCGAGCGACTTG | 19 | 60 | |||||

| bla IMP(3, 34) | Forward | GTGGTTCTTGTAAATGCTGAGG | 22 | 532 | 60 | This study | ||

| Reverse | CCGCCTGCTCTAATGTAAGT | 20 | 58 | |||||

| bla GES(1-22, 24) | Forward | GAAACCAAACGGGAGACGC | 19 | 207 | 60 | This study | ||

| Reverse | CTTGACCGACAGAGGCAACT | 20 | 60 | |||||

| bla GIM-1 | Forward | TCGACACACCTTGGTCTGAA | 20 | 477 | 58 | Ellington et al., 2007 (26) | ||

| Reverse | AACTTCCAACTTTGCCATGC | 20 | 56 | |||||

| bla OXA-2-like | Forward | ATTTCAAGCCAAAGGCACGA | 20 | 568 | 56 | This study | ||

| Reverse | GCCACTCAACCCATCCTACC | 20 | 63 | |||||

| bla OXA-10-like | Forward | ACGGAAAGCCAAGAGCCAT | 19 | 354 or 357 | 57 | This study | ||

| Reverse | CCCACACCAGAAAAACCAGT | 20 | 58 | |||||

| bla OXA-51-like | Forward | TGTACCTGCTTCGACCTTCA | 20 | 435 | 58 | This study | ||

| Reverse | TCCCCAACCACTTTTTGCGT | 20 | 58 | |||||

| bla OXA-58-like | Forward | GCCATTCCCCAGCCACTTTTA | 21 | 470 | 61 | This study | ||

| Reverse | CACGCATTTAGACCGAGCAA | 20 | 58 | |||||

| bla DIM-1 | Forward | CGGCTGTTTTGTGCGTAG | 18 | 215 | 56 | This study | ||

| Reverse | GCGTTCGGCTGGATTGATT | 19 | 57 | |||||

| bla CMY-2 | Forward | GCCGTTGCCGTTATCTAC | 18 | 511 | 56 | This study | ||

| Reverse | AATCTTTTTGTTCGTTCTGCG | 21 | 55 |

aFor degenerate primers: R = A or G; S = G or C; Y = C or T.

bDesigned primers but not tested.

3.3. DNA Extraction and Multiplex PCRs

DNA preparation was performed by suspending a colony of each bacterial strain in 100 μL of distilled water, boiling at 98°C for 10 minutes and centrifuging the cell extract for five minutes at 13,000 rpm. A multiplex PCR assay was designed to detect and differentiate one family of class A carbapenemase (KPC), three families of class B carbapenemases (IMP, NDM and VIM) and two families of class D carbapenemases (OXA) in two reactions. Both multiplex PCRs were performed with six pairs of specific primers (Table 1), which were used to amplify fragments (different in size) of 340 bp (KPC), 597 bp (OXA-48), 247 bp (VIM), 439 bp (NDM), 183 bp (IMP) and 736 bp (OXA-23). The PCR reaction mixture contained: 0.5 µL DNA (50 ng) in 24.5 µL complete reaction buffer with MgCl2 (containing 100 mmol/L Tris-HCl [pH 8.8], 500 mmol/L KCl, 1% Triton X-100, 15 mmol/L MgCl2) (Top-Bio, Czech Republic; 4 µL), dNTP (10 mM, 0.5 µL), 15 pmol of each primer (0.5 µL) and Taq DNA polymerase (Top-Bio, Czech Republic; 0.2 µL).

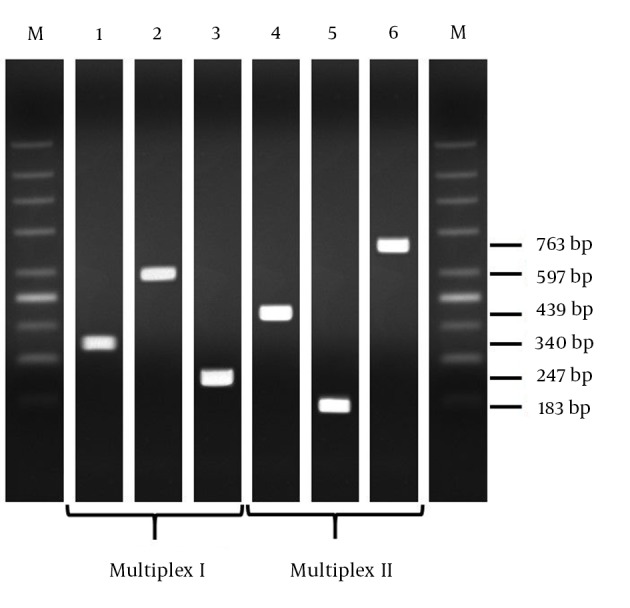

The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for five minutes, 35 cycles at 95°C for one minute, at different annealing temperatures for one minute and 72°C for one minute, followed by a single, final elongation step at 72°C for five minutes. The annealing temperature was optimal at 56°C for amplification of the blaKPC, blaOXA and blaVIM genes and optimal at 52°C for amplification of the blaNDM, blaIMP and blaOXA genes (Table 1). Amplicons were visualized after running at 100 V for 90 minutes on a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (Figure 1). A 200 – 1500 bp DNA ladder (Top-Bio, Czech Republic) was used as a size marker.

Figure 1. Detection of Genes Encoding Carbapenemases in Carbapenem-resistant Control Strains and Clinical Isolates by Multiplex PCR.

Notes, lane 1, control blaKPC gene; lane 2, control blaOXA-48 gene; lane 3, control blaVIM gene; lane 4, control blaNDM-1 gene; lane 5, control blaIMP gene; lane 6, control blaOXA-23 gene. M, Molecular mass markers (200 - 1500 bp DNA ladder).

4. Results

After optimizing the PCR (amplification) conditions, all positive controls (reference strains and clinical isolates) yielded amplicons of the predicted sizes and confirmed the specificity of the primers used (Figure 1). The primer paris were tested in mixed (Table 1, Figure 1) and individual reactions (data not shown). The two multiplex PCR assays were 6 validated with a panel of fifteen characterized Gram-negative bacterial strains. This collection includes 5 class A carbapenemases (5 KPC), 8 class B carbapenemases (2 IMP, 2 NDM and 4 VIM) and 2 class D carbapenemases (2 OXA). The resistance genes of the control isolates were correctly determined by each multiplex PCR (accuracy 100%; Figure 1). Non-specific amplification generating fragments of unexpected size was not observed. In addition, eleven pairs of primers have been proposed but not tested experimentally in PCR and/or multiplex reactions (Table 1).

5. Discussion

The emergence of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae has become a substantial clinical problem, since carbapenemase production cannot be easily inferred from the antimicrobial resistance profiles, thus, dissemination of these enzymes among nosocomial pathogens (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae) is a threat to public health and must be closely monitored (phenotypic and genotypic tests). In addition, delay in detection of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae results in longer hospitalizations and increased healthcare costs (26).

Recently, multiplex PCR assays for the detection of blaIMP, blaVIM, blaOXA, blaNDM and blaKPC have been described (25-30). Unfortunately, the primers used had lower detection ranges (many homologs are missed). For example, the multiplex PCR assay described by Kaase et al. (29) targeted VIM and IMP enzymes, among other carbapenemases, and allowed the detection of 22 variants of IMP (IMP-1 to IMP-22) and 13 variants of VIM (VIM-1 to VIM-13). However, according to the Lahey Clinic website, to this day over 41 IMP and 39 VIM derivatives have been documented. This suggests that specificity of those primers may be impaired due to sequence variations. Nijhuis et al. (30) targeted IMP, OXA-48-like types (OXA-48, 162, 163, 181, 204, 232, 244, 245, 370) and other carbapenemase genes. The assay reported in this study allowed the detection of 33.3% of IMP variants (14/42) and was not able to detect OXA-23 and OXA-247.

This study shows that primers in two multiplex PCRs are able to detect of KPC, VIM, NDM-1, OXA (OXA-23-like and OXA-48-like enzymes) and IMP variants (except IMP-3, IMP-16, IMP-27, IMP-31, IMP-34 and IMP-35) present in Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates. Due to the success of the first primer sets, the additional untested sets (Table 1) are predicted to detect the remaining NDM- and IMP-type enzymes and other carbapenemases. Therefore, the combination of primer sets presented in this study will cover all known carbapenemase genes found in Enterobacteriaceae.

The multiplex PCR assay described in this study is a fast, low-cost, efficient and accurate test for rapid screening of Enterobacteriaceae isolates with respect to drug resistant genes for blaKPC, blaVIM, blaIMP, blaNDM and blaOXA and cover 100% (19/19), 100% (39/39), 85.7% (36/42), 9.1% (1/11) and 8.5% (25/293) of the genes described in the Lahey database, respectively. The proposed untested primers may be also used for detection of the remaining carbapenemases in single and/or multiplex PCR reactions (Table 1). The resulting assays could collectively cover 92.9% (39/42), 100% (11/11), 100% (5/5), 100% (4/4), 95.8% (23/24) and 52.6% (154/293) of the blaIMP, blaNDM, blaSME, blaIMI, blaGES, blaOXA and other genes, respectively.

We included here all known carbapenemase genes that have been identified in clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae (blaKPC, blaOXA, blaVIM, blaNDM, blaIMP, blaSME, blaIMI, blaGES, blaGIM, blaDIM and blaCMY). In conclusion, primers tested in silico and in vitro may be used in single and/or multiplex PCR for screening encountered carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae, as well as for monitoring their emergence and spread (e.g., outbreaks).

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Ing. Jaroslav Hrabák, Ph.D. for providing bacterial strains with positive carbapenemase production.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution:Patrik Mlynarcik designed the primers; Patrik Mlynarcik and Magdalena Roderova carried out the experiments; Patrik Mlynarcik, Magdalena Roderova and Milan Kolar prepared the manuscript.

Funding/Support:This work was supported by project CZ.1.07/2.3.00/30.0004. This work was funded by the European Social Fund in the Czech Republic and by the state budget of the Czech Republic.

References

- 1.Canton R, Akova M, Carmeli Y, Giske CG, Glupczynski Y, Gniadkowski M, et al. Rapid evolution and spread of carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(5):413–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poirel L, Pitout JD, Nordmann P. Carbapenemases: molecular diversity and clinical consequences. Future Microbiol. 2007;2(5):501–12. doi: 10.2217/17460913.2.5.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornaglia G, Akova M, Amicosante G, Canton R, Cauda R, Docquier JD, et al. Metallo-beta-lactamases as emerging resistance determinants in Gram-negative pathogens: open issues. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;29(4):380–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandell GL, Douglas RG, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases. 6th ed. New York: Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaynes R, Edwards JR, National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance S. Overview of nosocomial infections caused by gram-negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(6):848–54. doi: 10.1086/432803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush K, Jacoby GA. Updated functional classification of beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(3):969–76. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01009-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinmann J, Kaase M, Gatermann S, Popp W, Steinmann E, Damman M, et al. Outbreak due to a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain harbouring KPC-2 and VIM-1 in a German university hospital, July 2010 to January 2011. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(33):19944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodford N, Turton JF, Livermore DM. Multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria: the role of high-risk clones in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35(5):736–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonnet R, Marchandin H, Chanal C, Sirot D, Labia R, De Champs C, et al. Chromosome-encoded class D beta-lactamase OXA-23 in Proteus mirabilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(6):2004–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.2004-2006.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janvari L, Damjanova I, Lazar A, Racz K, Kocsis B, Urban E, et al. Emergence of OXA-162-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Hungary. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46(4):320–4. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2013.879993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szekely E, Damjanova I, Janvari L, Vas KE, Molnar S, Bilca DV, et al. First description of bla(NDM-1), bla(OXA-48), bla(OXA-181) producing Enterobacteriaceae strains in Romania. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303(8):697–700. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villa L, Carattoli A, Nordmann P, Carta C, Poirel L. Complete sequence of the IncT-type plasmid pT-OXA-181 carrying the blaOXA-181 carbapenemase gene from Citrobacter freundii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(4):1965–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01297-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potron A, Rondinaud E, Poirel L, Belmonte O, Boyer S, Camiade S, et al. Genetic and biochemical characterisation of OXA-232, a carbapenem-hydrolysing class D beta-lactamase from Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;41(4):325–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oteo J, Hernandez JM, Espasa M, Fleites A, Saez D, Bautista V, et al. Emergence of OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and the novel carbapenemases OXA-244 and OXA-245 in Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(2):317–21. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez S, Pasteran F, Faccone D, Bettiol M, Veliz O, De Belder D, et al. Intrapatient emergence of OXA-247: a novel carbapenemase found in a patient previously infected with OXA-163-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(5):E233–5. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leski TA, Bangura U, Jimmy DH, Ansumana R, Lizewski SE, Li RW, et al. Identification of blaOXA-(5)(1)-like, blaOXA-(5)(8), blaDIM-(1), and blaVIM carbapenemase genes in hospital Enterobacteriaceae isolates from Sierra Leone. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(7):2435–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00832-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfeifer Y, Schlatterer K, Engelmann E, Schiller RA, Frangenberg HR, Stiewe D, et al. Emergence of OXA-48-type carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in German hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(4):2125–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05315-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seputiene V, Linkevicius M, Bogdaite A, Povilonis J, Planciuniene R, Giedraitiene A, et al. Molecular characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from hospitals in Lithuania. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59(Pt 10):1263–5. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.021972-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galani I, Souli M, Panagea T, Poulakou G, Kanellakopoulou K, Giamarellou H. Prevalence of 16S rRNA methylase genes in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from a Greek university hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):E52–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antunes NT, Lamoureaux TL, Toth M, Stewart NK, Frase H, Vakulenko SB. Class D beta-lactamases: are they all carbapenemases? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(4):2119–25. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02522-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mena A, Plasencia V, Garcia L, Hidalgo O, Ayestaran JI, Alberti S, et al. Characterization of a large outbreak by CTX-M-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and mechanisms leading to in vivo carbapenem resistance development. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(8):2831–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00418-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Safari M, Shojapour M, Akbari M, Pourbabaee A, Abtahi H. Dissemination of CTX-M-Type Beta-lactamase Among Clinical Isolates of Enterobacteriaceae in Markazi Province, Iran. Jundishapur J Microb. 2013;6(8) doi: 10.5812/jjm.7182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goessens WH, van der Bij AK, van Boxtel R, Pitout JD, van Ulsen P, Melles DC, Tommassen J. Antibiotic trapping by plasmid-encoded CMY-2 beta-lactamase combined with reduced outer membrane permeability as a mechanism of carbapenem resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(8):3941–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02459-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turton JF, Ward ME, Woodford N, Kaufmann ME, Pike R, Livermore DM, et al. The role of ISAba1 in expression of OXA carbapenemase genes in Acinetobacter baumannii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;258(1):72–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monteiro J, Widen RH, Pignatari AC, Kubasek C, Silbert S. Rapid detection of carbapenemase genes by multiplex real-time PCR. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(4):906–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellington MJ, Kistler J, Livermore DM, Woodford N. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding acquired metallo-beta-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(2):321–2. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poirel L, Walsh TR, Cuvillier V, Nordmann P. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70(1):119–23. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dallenne C, Da Costa A, Decre D, Favier C, Arlet G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(3):490–5. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaase M, Szabados F, Wassill L, Gatermann SG. Detection of carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae by a commercial multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(9):3115–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00991-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nijhuis R, Samuelsen O, Savelkoul P, van Zwet A. Evaluation of a new real-time PCR assay (Check-Direct CPE) for rapid detection of KPC, OXA-48, VIM, and NDM carbapenemases using spiked rectal swabs. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;77(4):316–20. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]