Abstract

Chronic wounds are a common complication in patients with diabetes that often lead to amputation. These non-healing wounds are described as being stuck in a persistent inflammatory state characterized by accumulation of pro-inflammatory macrophages, cytokines and proteases. Some medications approved for management of type 2 diabetes have demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties independent of their marketed insulinotropic effects and thus have underappreciated potential to promote wound healing. In this review, the potential for insulin, metformin, specific sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors to promote healing is evaluated by reviewing human and animal studies on inflammation and wound healing. The available evidence indicates that diabetic medications have potential to prevent wounds from becoming arrested in the inflammatory stage of healing and to promote wound healing by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines, upregulating growth factors, lowering matrix metalloproteinases, stimulating angiogenesis, and increasing epithelization. However, no clinical recommendations currently exist on the potential for specific diabetic medications to impact healing of chronic wounds. Thus, we encourage further research that may guide physicians on providing personalized diabetes treatments that achieve glycemic goals while promoting healing in patients with chronic wounds.

Keywords: wound healing, insulin, metformin, sulfonylurea, thiazolidinedione, DPP-4 inhibitor

1. INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is an increasing healthcare problem in the United States, affecting 6.5 million patients in 1990 to over 29 million in 2014 and incurring yearly costs that exceed $245 billion (American Diabetes Association 2013, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014, Gregg, Li et al. 2014). Diabetes is associated with impaired wound healing, making patients susceptible to chronic non-healing wounds (Eming, Martin et al. 2014). Such wounds precede 84% of all diabetic lower extremity amputations (Reiber, Vileikyte et al. 1999) and once amputation occurs, patients have a 5-year mortality rate of 50% (Faglia, Favales et al. 2001, Eming, Martin et al. 2014, Gregg, Li et al. 2014).

Chronic diabetic wounds are trapped in a persistent inflammatory state with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and proteases together with impaired expression of growth factors (Eming, Martin et al. 2014, Mirza, Fang et al. 2014). At the same time, the CDC reported that out of 20.9 million respondents with diabetes in the National Health Interview Survey, 2.9 million take insulin only, 11.9 million take oral diabetic medications only, 3.1 million take both, and 3 million take none (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014). Thus, while over 70% of patients with diabetes take diabetic medications regularly at an annual cost of over $50 billion (American Diabetes Association 2013), little is known about whether these medications influence wound healing outcomes, either directly through effects on cells involved in wound healing or indirectly through effects on systemic processes that can affect healing. As a result, no clinical recommendations exist regarding the impact of diabetic medications on healing of chronic wounds.

Wound healing involves a complex sequence of cellular and molecular processes including inflammation, cell proliferation, angiogenesis, collagen deposition, and re-epithelization (Falanga 2005, Reiber and Raugi 2005). Among the early events of a wound-healing response is infiltration of inflammatory cells at the wound site (Martin and Leibovich 2005). This inflammatory response includes accumulation of macrophages which are an important contributor to healing, since monocyte/macrophage depletion results in delayed re-epithelialization, reduced collagen deposition, impaired angiogenesis, and decreased cell proliferation (Leibovich and Ross 1975, Mirza, DiPietro et al. 2009, Lucas, Waisman et al. 2010). However, prolonged inflammatory responses in wounds are associated with impaired healing (Loots, Lamme et al. 1998, Eming, Martin et al. 2014). Our laboratory has demonstrated that macrophages exhibit a persistent pro-inflammatory phenotype expressing high levels of pro-inflammatory molecules like interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and the protease matrix metalloprotease-9 (MMP-9) during impaired healing associated with diabetes (Mirza, Fang et al. 2013, Mirza, Fang et al. 2014, Mirza, Fang et al. 2015). This pro-inflammatory phenotype may be induced by hyperglycemia, which has been reported to increase oxidative and inflammatory stress via production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and TNF-α (Mohanty, Hamouda et al. 2000, Aljada, Friedman et al. 2006).

Since macrophages are the primary producers of pro-inflammatory cytokines in wounds (Mirza, Fang et al. 2015), recent wound healing studies have focused on studying macrophage dysfunction in chronic wounds of diabetic humans and mice. Classically activated or M1-like macrophages are known for killing microorganisms and producing pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, TNF-α and interleukin 6 (IL-6) (Novak and Koh 2013). In contrast, the alternatively activated or M2-like macrophages produce anti-inflammatory factors like IL-10, pro-healing factors such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and transforming growth factor β (TGF- β), and promote wound regenerative actions (Novak and Koh 2013). Thus, the transition of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory M1-like phenotype to an alternative M2-like phenotype has been suggested as a pre-requisite for the switch from inflammation to proliferation in the healing wound (Koh and DiPietro 2011).

Initial studies have compared anti-inflammatory properties between diabetic medications by measuring their effects on the systemic inflammation marker C-reactive protein (CRP) or high-sensitive CRP (hs-CRP) (Kahn, Haffner et al. 2010). Both measure CRP but at different ranges (CRP: 0–10 mg/dL and hs-CRP: < 3 mg/L). CRP is an acute-phase reactant primarily synthesized in the liver by macrophages and fat cells under the stimulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6. Furthermore, CRP has been shown in large clinical trials to provide prognostic information regarding the state of diabetogenesis and metabolic syndrome (Pradhan, Manson et al. 2001). In the case of the multinational clinical study “A Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial” (ADOPT) where 904 drug-naïve patients with type 2 diabetes were treated for a median of 4.0 years with rosiglitazone (a thiazolidinedione), glyburide (a sulfonylurea), or metformin, a subset analysis of patients with CRP measurements concluded that CRP reduction was greatest in the rosiglitazone group by 47.6% relative to glyburide and by 30.5% relative to metformin (Kahn, Haffner et al. 2010).

Many diabetic medications have demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties independent of their known marketed insulinotropic effects. Since an increased inflammatory state is linked with impaired healing and diabetic medications may have anti-inflammatory properties, it seems reasonable to speculate that diabetic medications could have an influence on wound healing. The aim of this article is to critically review the available literature on the influence of commonly prescribed medications for the treatment of type 2 diabetes on inflammation and wound healing. For each medication section, we focus on mechanisms of action, human clinical trial data, animal study results, study limitations and safety concerns. To identify relevant studies, we performed a literature search on PUBMED and clinicaltrials.gov using the generic name of the medications on this study and “wound healing”, “inflammation”, or “diabetes”. We illustrate that investigating the effects of diabetes medications on wound healing may allow clinicians the opportunity to offer personalized diabetic patients treatments that both treat the systemic diabetic condition that target the persistent inflammatory conditions associated with chronic wounds.

2. INSULIN

Decreased insulin action is a hallmark of diabetes. Systemic insulin treatment is used for glycemic control and according to the CDC, over 6 million Americans use insulin as daily diabetes treatment (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014). Insulin serves an important role in glucose metabolism, protein synthesis, and proliferation and differentiation of different cell types suggesting that the hormone is capable of affecting different processes involved in wound healing (Apikoglu-Rabus, Izzettin et al. 2010). Additionally, insulin has been shown to induce an anti-inflammatory effect in monocytes from obese patients via reduction of NFkβ signaling and ROS generation (Dandona, Aljada et al. 2001).

Despite the millions of patients taking insulin, no large prospective or retrospective clinical trials have been performed on the effects of systemic insulin treatment on the incidence or healing of diabetic chronic wounds. However, several studies including small clinical trials have shown that application of topical insulin improves wound healing in diabetic humans and animals (Rezvani, Shabbak et al. 2009, Apikoglu-Rabus, Izzettin et al. 2010, Lima, Caricilli et al. 2012). In a recent study, topical use of a 0.5 units (U)/100 gram insulin cream on chronic wounds of patients with type 2 diabetes as part of a prospective, double-blind randomized clinical trial showed complete wound closure in 4 out of 10 patients by 8 weeks vs. none in the placebo group of 12 patients (Lima, Caricilli et al. 2012). In addition, a pilot trial tested the angiogenic potential of insulin treatment on 8 diabetic patients presenting with full-thickness wounds by treating half of their wounds topically with 10 U of insulin while leaving the other half untreated for 14 days. Their results indicated that biopsies from the insulin treated half showed a higher number of new vessels (96 +/− 47) vs. the non-insulin side (32.88 +/− 45) (Martinez-Jimenez, Aguilar-Garcia et al. 2013). Furthermore, in the outpatient clinical setting, topical application of 10 U of insulin on non-diabetic patients with acute (crush wounds, burns) and chronic wounds (pressure ulcers) resulted in a faster daily rate of wound closure (46.09 mm2/day) when compared to saline treated patients (32.24 mm2/day). However, while time to heal (45 days +/− 2 days) was not different between the two groups, the wound sizes in the insulin treatment group were larger at treatment initiation (Rezvani, Shabbak et al. 2009).

In animal studies, several investigators have used streptozotocin (STZ)-injected diabetic rats (a model of type 1 diabetes) to examine the effects of topical insulin on wound healing. One of those studies showed that application of topical insulin on wounds of STZ-injected diabetic rats shortened the median time needed for complete epithelialization from 13 to 11 days (Apikoglu-Rabus, Izzettin et al. 2010). A larger study showed that that topical application of 0.5 U/100 g insulin cream to wounds of STZ-injected diabetic rats induced faster wound healing which was associated with increased activation of the AKT and ERK pathways and increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and stromal cell-derived factor 1α (SDF1α) expression on wounds (Lima, Caricilli et al. 2012). Furthermore, they showed a dose-dependent response where 0.5 U of insulin led to wound closure around 9 days compared to the 11 days for the group treated with 0.25 U insulin and 16 days for the 0.1 U and non-insulin cream control groups.

Mechanistically, insulin has been shown to increase VEGF expression in keratinocytes in excisional wounds of C57BL6 and ob/ob mice via increased AKT signaling (Goren, Muller et al. 2009). Previous studies using cultured keratinocytes from insulin receptor knock out mice showed that absence of insulin signaling induces abnormal differentiation despite increased IGF-1 signaling (Wertheimer, Spravchikov et al. 2001). In addition, recent studies using transgenic mice with an inducible Cre-LoxP deletion of both the insulin and IGF-1 receptors on vascular endothelial cells showed that deletion of insulin and IGF-1 receptors in endothelial cells had little effect on days to superficial wound closure but that the loss of insulin signaling resulted in a large reduction of wound vascularization and granulation tissue formation underscoring the need for insulin signaling in this aspect of wound healing (Aghdam, Eming et al. 2012).

Using non-diabetic mouse models, insulin was also shown to affect early accumulation of inflammatory cells in wounds of mice. Topical treatment with 0.03U insulin/20 μl saline was reported to increase macrophage infiltration in the first 2 days of full-thickness skin wounds of non-diabetic C57BL/6J mice by increasing expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), a potent chemotactic factor for macrophages. Blockage of MCP-1 resulted in reduced macrophage infiltration and impaired wound healing despite the presence of insulin (Chen, Liu et al. 2012).

One limitation of topical insulin studies is the use of zinc to crystallize insulin. Zinc is an essential mineral with anti-inflammatory properties that has been publicized to promote wound healing. One recent randomized pilot study used 90 non-diabetic patients with various community-acquired wounds to compare topical insulin (containing zinc), aqueous zinc chloride solution, and saline controls on healing of open uncomplicated wounds. Their results showed that the insulin and zinc solution induced faster wound healing than saline treated groups. However, the insulin treated groups appeared to provide a superior effect compared with the zinc group, but this effect was not significant due to the heterogeneity of the wounds types and sizes (Attia, Belal et al. 2014).

It is important to mention that endogenous production of human insulin by pancreatic beta cells includes proinsulin C-peptide which is secreted into circulation in equimolar concentrations to regular insulin. Despite previous reports of no effect in diabetic wounds of STZ-injected SKH-1 mice using 10 nM of C-peptide (Langer, Born et al. 2002), a recent study using STZ-injected C57BL6 mice showed that administration of a 35 pmol/kg per minute dose of C-peptide delivered by mini-osmotic pumps in saline for 2 weeks was able to induce 95% wound closure 30% faster (10 vs. 14 days) than untreated diabetic control mice with sham pump surgeries (Lim, Bhatt et al. 2015). If future studies validate these findings, insulin secretagogue diabetic medications might mediate a synergistic wound healing effect by increased c-peptide secretion that exogenous insulin injections cannot offer.

Considering that most patients with diabetes will eventually be placed on insulin treatment, further investigations should be pursued on the effects of insulin on wound healing. In addition, while the literature contains some evidence that topical insulin may promote wound healing, a large multi-center clinical trial is still needed to demonstrate whether such treatment is effective on a large numbers of patients.

3. METFORMIN

Metformin, a biguanide, is currently the first line medication for initial treatment of type 2 diabetes and works by suppressing glucose production by the liver via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (Hundal, Krssak et al. 2000). Despite being one of oldest medications prescribed to patients with type 2 diabetes, few studies have investigated its influence on wound healing.

Unfortunately, a review of the literature revealed no studies on the effects of metformin on wound healing in diabetic patients. However, some clinical studies indicate that oral metformin may induce modest amelioration of systemic inflammation. An outpatient clinic follow-up study of 110 patients with type 2 diabetes taking only metformin or the sulfonylurea glyburide for 4 years indicated that metformin users had lower levels of the inflammatory marker CRP (5.56 ± 1.5 mg/L) than patients taking the glyburide (8.3 ± 1.4 mg/L) (Akbar 2003). Metformin has also been shown to decrease the pro-inflammatory cytokine macrophage migration inhibitor factor (MIF) in the plasma and monocytes from obese patients when compared to untreated patients (Dandona, Aljada et al. 2004). Furthermore, a meta-analysis of 33 human studies looking at the effects of metformin on CRP levels of patients with type 2 diabetes indicated decreases on serum levels of CRP (Shi, Tan et al. 2014).

In laboratory experiments, metformin treatment of isolated human monocytes stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) showed that the drug inhibits production of TNF-α via inhibition of the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) pathway (Arai, Uchiba et al. 2010). Another study indicated that RAW276.4 macrophages stimulated with LPS and treated with various concentrations of metformin (1–10 mM) exhibited decreased production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IFN-γ in a dose dependent manner (Nath, Khan et al. 2009). In addition, diabetic nephropathy related studies demonstrated that metformin decreased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation via suppressing RAGE expression on human renal proximal tubular cells in vitro (Ishibashi, Matsui et al. 2012). Lastly, AMPK activation (a known metformin effect) has been shown to induce anti-inflammatory properties via suppression of NF-kβ signaling (Salminen, Hyttinen et al. 2011).

Despite the potential for metformin to ameliorate inflammation, there is little information available on the potential for metformin to influence wound healing. However, a bioengineering group recently demonstrated that biodegradable nanofibrous drug-eluting membranes designed to sustainably release metformin, accelerated epithelization in wounds of STZ-injected diabetic rats. Specifically, the metformin-eluting membrane induced an 85% vs. 67% wound closure by day 7 and 97% vs. 85% closure by day 14 compared to non-eluting membrane treated wounds (Lee, Hsieh et al. 2014). In addition, there is a large on-going Phase II clinical trial studying whether oral metformin (1000 mg three times a day) can help wound healing on burned children with expected results in 2017. The clinicians hypothesize that compared to a sugar pill placebo, metformin will provide greater anabolic activity that will translate into improved wound healing of burned tissues in children (Herndon 2015).

4. SULFONYLUREAS

Sulfonylureas such as glyburide (glibenclamide) and glimepiride are some of the most commonly used medications for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Sulfonylureas work by binding to a receptor on the ATP-dependent potassium channel in the pancreatic beta cells. The binding inhibits the potassium channels which changes the resting potential of the beta cells allowing higher sensitivity to glucose which induces greater insulin secretion (Bressler and Johnson 1997).

Again, although no studies were found on the effects of sulfonylureas on wound healing in diabetic patients, a few studies have investigated effects on inflammation. To investigate the potential influence of different sulfonylurea drugs on inflammation, a small number of type 2 diabetes patients were switched from glyburide to glimepiride for 28 weeks and titrated up to 6 mg/day. The switch was associated with increased adiponectin and decreased plasma TNF-α, IL-6, and hs-CRP levels compared to patients maintained on glyburide or insulin treated patients (Koshiba, Nomura et al. 2006). Another study on treatment naive type 2 diabetes patients comparing glyburide vs. metformin monotherapy titrated for glycemic control to dosages up to 20 mg/day for glyburide or 2,550 mg/day for metformin indicated that only glyburide was able to induce a reduction in CRP levels within a 3 month time-frame (Putz, Goldner et al. 2004). Together, these studies point to the systemic anti-inflammatory potential of sulfonylureas in patients with diabetes.

One sulfonylurea, glyburide, has been shown to downregulate inflammation and promote wound healing through its ability to inhibit the nod-like receptor protein (NLRP)-3 inflammasome. Previous studies had found that the sulfonyl and benzamido groups on glyburide chemical structure allow for its specific (NLRP)-3 inflammasome inhibitory activity, which is not shared by other sulfonylureas (Lamkanfi, Mueller et al. 2009). Targeting the (NLRP)-3 inflammasome may be particularly useful for reducing inflammation in diabetes since its activation under chronic hyperglycemic states has been shown to initiate an intracellular inflammatory cascade that promotes a persistent pro-inflammatory state (Zhou, Tardivel et al. 2010). In addition, diabetes–mediated metabolic syndrome induces accumulation of lipid activators that facilitate assembly of the (NLRP)-3 inflammasome leading to activation of caspase-1 and increased secretion of IL-1β and IL-18, both pro-inflammatory factors, which exacerbate systemic inflammation and insulin resistance (Bitto, Altavilla et al. 2013).

Since IL-1β is predominantly produced by monocytes and macrophages (Mirza, Fang et al. 2015), use of an inflammasome inhibitor to lower IL-1β expression may be an appealing anti-inflammatory strategy since these inflammatory cells are key regulators of the wound healing process (Koh and DiPietro 2011). Notably, treatment of excisional wounds on db/db diabetic mice with topical glyburide was shown to accelerate epithelialization and increase granulation tissue formation. In addition, glyburide treatment decreased levels of pro-inflammatory IL-1β and IL-18 in wound homogenates and reduced mRNA expression in macrophages isolated from wounds. Glyburide treatment also induced concurrent increased expression of pro-healing IGF-1, TGF-β, and IL-10 growth factors (Mirza, Fang et al. 2014). Separate confirmatory studies using local wound treatment of incisional wounds in diabetic db/db mice with the I-κB kinase-β inhibitor, BAY 11-7082, which also inhibits the (NLRP)-3 inflammasome, showed improved wound healing and increased angiogenesis with upregulation of VEGF and SDF-1α (Bitto, Altavilla et al. 2013).

Together, these studies show promise for the use of glyburide as a topical treatment to inhibit the inflammasome and promote healing of chronic wounds on diabetic patients. By restricting the use of glyburide to the wound area, there is also a decreased risk of side effects like hypoglycemia that is commonly reported when used systemically (Shorr, Ray et al. 1996). Future studies testing its effectiveness for ameliorating inflammation and accelerating wound closure in a clinical trial appears to be warranted. In addition, wound healing studies comparing glyburide to newer generation sulfonylureas may identify other candidates for therapeutic use.

5. THIAZOLIDINEDIONES

Thiazolidinedione (TZD) medications improve insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus by targeting the peroxisome proliferator-activated gamma receptor (PPAR-γ), which is thought to increase insulin sensitivity by retention of fatty acids in adipose tissue and regulation of adipocyte secreted hormones that impact glucose homeostasis (Rangwala and Lazar 2004). Early studies evaluating anti-inflammatory properties by rosiglitazone showed its ability to lower MCP-1 and CRP in plasma and NFkβ-binding activity in mononuclear cell extract from a group of non-diabetic and diabetic obese patients treated for 6 weeks (Mohanty, Aljada et al. 2004).

A single-centre, randomized, open-label study in type 2 diabetes patients showed that 12 weeks of rosiglitazone treatment leads to greater reductions in inflammatory biomarkers compared to metformin/glyburide treatment including greater decreases in hs-CRP (58% vs. 26% non-significant reduction in metformin/glyburide group) (Gupta, Teoh et al. 2012). When studies were performed on human macrophages isolated from blood, TZD mediated PPAR-γ activation was shown to inhibit the expression of the pro-inflammatory genes TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β suggesting its role as a negative regulator of macrophage activation (Jiang, Ting et al. 1998). However, in vitro studies that blocked all PPAR activity demonstrated that TZD medications can induce anti-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic effects independent of PPAR (Schiefelbein, Seitz et al. 2008).

Another commonly prescribed TZD, pioglitazone, was shown in a prospective clinical trial of 50 patients with type 2 diabetes to decrease inflammatory cytokines and increase pro-angiogenic factors in plasma (Vijay, Mishra et al. 2009). Specifically, 20 patients on 45mg pioglitazone daily for 16 weeks showed decreased TNF-α, CRP, and lipid profile proteins (due to its partial PPAR-α activity) with increases in VEGF, IL-8 and angiogenin when compared to 10 control patients on sulfonylureas or other insulin secretagogues. An additional 20 patients taking 4mg rosiglitazone showed similar but less robust effects than patients on pioglitazone except for no changes in TNF-α or lipid profile. Overall, a recent meta-analysis of 27 randomized controlled trials evaluating pioglitazone and rosiglitazone therapy on circulating levels of inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes showed that both medications decreased levels of hs-CRP and MCP-1 with limited effects on IL-6 and MMP-9 (Chen, Yan et al. 2015).

Recent studies have reported that topical treatment of wounds on db/db diabetic mice with rosiglitazone reported improved wound healing by inducing a switch of pro-inflammatory macrophages towards a pro-healing phenotype (Mirza, Fang et al. 2015). They also found that diabetic wounds from mouse and human patients showed impaired PPAR-γ activity due to sustained expression of IL-1β, which maintained wounds in a persistent inflammatory state. Mechanistically, PPAR-γ has been reported to control the inflammatory response by inhibition AP-1, NF-κβ, or STAT-3 signaling pathways in macrophages (Chinetti, Fruchart et al. 2003) and likely other cells. Additionally, a recent study showed that macrophages deficient in PPARγ from PPARγ knock out mice exhibited impaired skin wound healing with high expression of TNF-α and reduced collagen deposition, angiogenesis and granulation formation (Chen, Shi et al. 2015). They also found that treatment with rosiglitazone on wounds of wild type mice resulted in accelerated wound healing and decreased TNF-α levels compared to wounds of vehicle treated controls, but that rosiglitazone did not elicit these changes in PPARγ-knock out mice. In the case of pioglitazone, a study showed its ability to inhibit matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) which is a potent protease shown to be associated with impaired healing in diabetes. Using an in-vitro model of HaCaT cells, treatment with advanced glycation end product (AGE) induced high levels of MMP-9 protease, which was inhibited with pioglitazone in a dose dependent manner (Zhang, Huang et al. 2014).

Today, pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are the only TZDs that remain on the market after safety concerns caused the withdrawal of the other TZD medications. However, both medications have been associated with increased incidence of heart failure, weight gain, peripheral edema, and more recently, bone fractures (Dormandy, Charbonnel et al. 2005, Colhoun, Livingstone et al. 2012). In summary, TZD medications may represent an option to dampen inflammation and have potential to promote healing of chronic wounds. In addition, their recent availability as generic medications lowers their costs significantly. Importantly, topical TZD treatment may benefit chronic wounds while avoiding the risks associated with systemic administration.

6. DIPEPTIDYL PEPTIDASE 4 INHIBITORS

The incretin hormones glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) are reported to account for 50% to 70% of postprandial insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells (Baggio and Drucker 2007). The hormones are secreted after a meal from the small intestine but have a circulating half-life of less than 2 minutes from its rapid degradation by dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) (Lovshin and Drucker 2009). Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (DPP-4i) are diabetes medications that work by blocking DPP-4 inactivation of the incretin hormones to allow extended stimulation of pancreatic insulin secretion and inhibition of glucagon release in a glucose-dependent manner (Koliaki and Doupis 2011, Shah, Kampfrath et al. 2011). Since DPP-4 and GLP-1 receptors are widely expressed throughout the human body including monocyte/macrophages; it has been proposed that incretin based therapies may exert pleiotropic effects that extend beyond pancreatic islet stimulation (Koliaki and Doupis 2011). Studies on diabetic humans and mice have indicated that DPP-4i improve postprandial lipemia, reduce inflammatory markers, improve endothelial function, reduce platelet aggregation, and are weight neutral (Scheen 2015).

In human studies, a prospective randomized study with 22 type 2 diabetes patients treated with sitagliptin or placebo for 12 weeks resulted in decreases on plasma levels of CRP, IL-6, free fatty acids, and mononuclear cell expression of TNF-α, JNK-1, TLR-2, and TLR-4 indicating an anti-inflammatory response (Makdissi, Ghanim et al. 2012). Another prospective randomized study comparing two DPP-4i medications, sitagliptin and vildagliptin, in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled by metformin showed that, as an add on therapy, the medications lowered plasma pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-18, and TNF-α (Rizzo, Barbieri et al. 2012).

A review of the literature revealed only two studies on the effects of DPP-4i on wound healing, one in humans and one in mice. In the first study, an open label study showed that diabetic patients for whom vildagliptin was added to their diabetes treatment plan (+/− insulin, metformin, and/or a sulfonylurea) had improved healing of foot ulcers after 12 weeks compared to foot ulcers from patients without vildagliptin. Biopsies from patients treated with vildagliptin showed increased staining of HIF-1α and VEGF that suggested pro-angiogenic involvement (Marfella, Sasso et al. 2012). Since they also detected decreases on nitrotyrosine levels and proteasome 20S activity on tissues from treated patients, investigators proposed that vildagliptin may work by reducing oxidative stress and preventing increased ubiquitin proteosome system degradation of HIF-1α leading to increased VEGF expression.

In the second study, linagliptin improved wound healing in diabetic ob/ob mice by increasing re-epithelialization and myofibroblast differentiation compared with untreated mice. Linagliptin treatment also induced increases in SDF-1α and MIP-2 protein expression (Schurmann, Linke et al. 2012). Unexpectedly, their studies using cultured HaCaT keratinocytes indicated that DPP-4 does not directly influence keratinocyte proliferation, since linagliptin was unable to induce increased proliferation at any concentration. Furthermore, addition of active GLP-1 to keratinocytes induced a reduction of EGF-induced phosphorylation of p42/44 MAPK arguing against an effect by GLP-1 on the regulation of keratinocyte proliferation.

It is important to note that while vildagliptin is not available in the US since it has not received FDA approval, they are six other DPP-4i medications that are currently offered. As for adverse effects, DPP-4i and GLP-1 receptor agonists have been associated with pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer although several studies have indicated no increased risk including a recent meta-analysis (Li, Shen et al. 2014). Also, vildagliptin has been recently associated with skin reactions although the reported instances are very rare (7 cases in total) and most patients were on metformin as well (Bene, Jacobsoone et al. 2015) making a clear inference difficult. In summary, as the most recent diabetes medication class to show anti-inflammatory potential, further research is needed to determine whether DPP-4i can be used to promote wound healing.

7. CONCLUSION

In 2012, 30% of the $176 billion in direct medical costs of treating diabetes in the United States was used to purchase medications to treat diabetes and its complications (American Diabetes Association 2013). At the same time, introducing new diabetic medications costs billions of dollars and years of research. Thus, millions of patients could benefit from identification of favorable pleiotropic effects of available diabetes medications that may ameliorate diabetes related complications including poor wound healing. While several factors contribute to impaired wound healing in patients with diabetes, amelioration of the persistent inflammation involved in chronic wounds may be a goal that can be achieved with existing medications. Such therapies could provide an anti-inflammatory effect to prevent wounds from becoming arrested in the inflammatory stage and promote non-healing wounds to progress to epithelization.

Recent investigations of insulin, metformin, specific sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, and DPP-4 inhibitors indicate that they possess anti-inflammatory properties. Many of these medications are now known to downregulate the pro-inflammatory phenotype of macrophages and to increase the anti-inflammatory and healing-associated macrophage phenotypes, decrease levels of matrix metalloproteinases, increase keratinocyte and fibroblast proliferation, induce new vessel formation from endothelial cells, and accelerate wound closure. In addition, many of the reviewed medications appear to exhibit potential to stimulate angiogenesis and granulation tissue formation that is necessary for effective wound healing.

Our review of clinical data suggests that the thiazolidinedione rosiglitazone results in the lowest levels of the inflammation marker CRP followed by the sulfonylurea glyburide when compared to metformin. However, it remains to be seen whether the reported anti-inflammatory results translate to improved healing of chronic wounds. Thus, further research is needed to determine the potential of the different diabetes medications currently available in the market on improving the healing of chronic wounds. Considering the millions of patients taking these medications, future wound healing research efforts should involve both clinical studies (e.g. retrospective studies, prospective cohort studies, as well as clinical trials) and basic science studies using animal models of diabetes. The focus should be on elucidating which drugs are most beneficial for type 2 diabetes patients suffering from chronic wounds. Also, since in clinical practice most patients with type 2 diabetes take multiple diabetic medications at the same time and there is a lack of studies on the effects of concomitant diabetic medications on wound healing, it seems necessary to perform studies on the impact of combining multiple diabetic medications on healing. A future aim should be the creation of recommendations in collaboration with wound healing clinicians and primary care diabetes physicians to provide personalized diabetes treatments that achieve glycemic goals while promoting wound healing conditions in patients with chronic wounds.

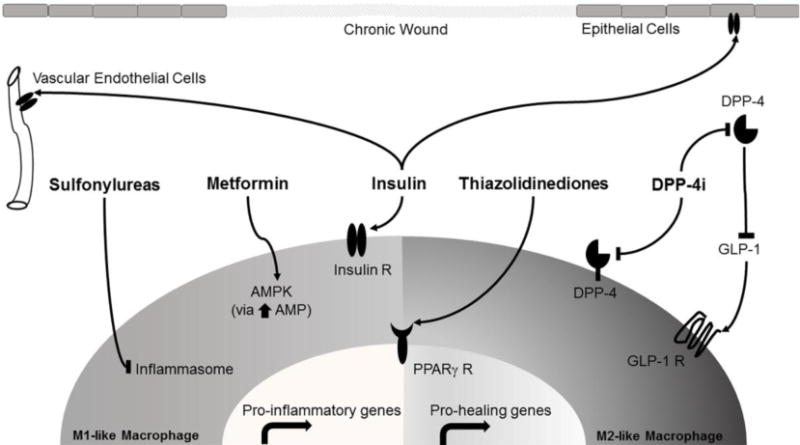

Figure 1. Diabetes Medications Associated Mechanisms of Action Involved in Wound Healing.

The figure shows signaling pathway that may be targeted by diabetic medications on epithelial cells (keratinocytes), vascular endothelial cells, “classically activated” M1-like macrophages, and “alternative activated” M2-like macrophages present in chronic wounds. Classically activated M1-like macrophages produce pro-inflammatory gene products that maintain wounds on a persistent inflammatory state. Alternative activated M2-like macrophages produce more pro-healing gene products that allow wound to resolve the inflammatory state and proceed to healing. All receptors (Insulin R, PPARγ R and GLP-1 R) and cell targets are present in both types of macrophages.

Table 1.

Summary of Reported Changes on Molecular Pathways and Cytokine Levels by Diabetes Medications in Wound Healing.

| Medications | Reported Molecular Pathways Affected | Reported Effects on Growth Factors and Cytokines Involved in Wound Healing | FDA Reported Clinical Side Effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-Inflammatory | Pro-Healing | |||

| Insulin | AKT ERK |

⬆ MCP-1 ⬇ ROS |

⬆ VEGF ⬆ SDF1α |

|

| Metformin | AMP-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) ERK NFkβ |

⬇ TNFα ⬇ IL-6 ⬇ INF-γ ⬇ ROS ⬇ MIF |

Lactic Acidosis (Black Label Warning) | |

| Sulfonylureas (Glyburide) | Inhibit Nod-Like Receptor NLRP-3 Inflammasome |

⬇ IL-1β ⬇ IL-18 |

⬆ IGF-1 ⬆ TGF-β ⬆ IL-10 |

Hypoglycemia |

| TZD | PPARγ Activation NFkβ P38 MAPK |

⬇ TNFα ⬇ IL-6 ⬇ Resistin ⬇ IL-1β ⬇ MCP-1 ⬇ MMP-9 |

⬆ VEGF ⬆ IL-8 ⬆ Adiponectin |

Congestive Heart Failure (Black Label Warning) |

| DPP-4 Inhibitors | Inhibition of DPP-4 proteases Extend GLP-1 bioavailability |

⬇ TNFα ⬇ IL-6 ⬇ IL-18 ⬆ MIP-2 |

⬆ VEGF ⬆ SDF1α |

Heart Failure (Saxagliptin) |

Highlights.

Chronic wounds in diabetic patients exhibit persistent inflammation.

Diabetes medications exhibit anti-inflammatory properties

These medications have underappreciated potential to promote wound healing

Further research needed to guide diabetes treatment in patients with chronic wounds

Acknowledgments

Source of funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institute of Health Award RO1GM092850 (TJK). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aghdam SY, Eming SA, Willenborg S, Neuhaus B, Niessen CM, Partridge L, Krieg T, Bruning JC. Vascular endothelial insulin/IGF-1 signaling controls skin wound vascularization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;421(2):197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar DH. Effect of metformin and sulfonylurea on C-reactive protein level in well-controlled type 2 diabetics with metabolic syndrome. Endocrine. 2003;20(3):215–218. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:20:3:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aljada A, Friedman J, Ghanim H, Mohanty P, Hofmeyer D, Chaudhuri A, Dandona P. Glucose ingestion induces an increase in intranuclear nuclear factor kappaB, a fall in cellular inhibitor kappaB, and an increase in tumor necrosis factor alpha messenger RNA by mononuclear cells in healthy human subjects. Metabolism. 2006;55(9):1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):1033–1046. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apikoglu-Rabus S, Izzettin FV, Turan P, Ercan F. Effect of topical insulin on cutaneous wound healing in rats with or without acute diabetes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(2):180–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai M, Uchiba M, Komura H, Mizuochi Y, Harada N, Okajima K. Metformin, an antidiabetic agent, suppresses the production of tumor necrosis factor and tissue factor by inhibiting early growth response factor-1 expression in human monocytes in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334(1):206–213. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.164970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia EA, Belal DM, El Samahy MH, El Hamamsy MH. A pilot trial using topical regular crystalline insulin vs. aqueous zinc solution for uncomplicated cutaneous wound healing: Impact on quality of life. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22(1):52–57. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2131–2157. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bene J, Jacobsoone A, Coupe P, Auffret M, Babai S, Hillaire-Buys D, Jean-Pastor MJ, Vonarx M, Vermersch A, Tronquoy AF, Gautier S. Bullous pemphigoid induced by vildagliptin: a report of three cases. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2015;29(1):112–114. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitto A, Altavilla D, Pizzino G, Irrera N, Pallio G, Colonna MR, Squadrito F. Inhibition of inflammasome activation improves the impaired pattern of healing in genetically diabetic mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;171(9):2300–2307. doi: 10.1111/bph.12557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressler R, Johnson DG. Pharmacological regulation of blood glucose levels in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(8):836–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. 2014 Retrieved 1 July 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf.

- Chen H, Shi R, Luo B, Yang X, Qiu L, Xiong J, Jiang M, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Wu Y. Macrophage peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma deficiency delays skin wound healing through impairing apoptotic cell clearance in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1597. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Yan J, Liu P, Wang Z. Effects of thiazolidinedione therapy on inflammatory markers of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Liu Y, Zhang X. Topical insulin application improves healing by regulating the wound inflammatory response. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20(3):425–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinetti G, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: new targets for the pharmacological modulation of macrophage gene expression and function. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2003;14(5):459–468. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200310000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colhoun HM, Livingstone SJ, Looker HC, Morris AD, Wild SH, Lindsay RS, Reed C, Donnan PT, Guthrie B, Leese GP, McKnight J, Pearson DW, Pearson E, Petrie JR, Philip S, Sattar N, Sullivan FM, McKeigue P, G. Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology Hospitalised hip fracture risk with rosiglitazone and pioglitazone use compared with other glucose-lowering drugs. Diabetologia. 2012;55(11):2929–2937. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2668-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandona P, Aljada A, Ghanim H, Mohanty P, Tripathy C, Hofmeyer D, Chaudhuri A. Increased plasma concentration of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and MIF mRNA in mononuclear cells in the obese and the suppressive action of metformin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(10):5043–5047. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandona P, Aljada A, Mohanty P, Ghanim H, Hamouda W, Assian E, Ahmad S. Insulin inhibits intranuclear nuclear factor kappaB and stimulates IkappaB in mononuclear cells in obese subjects: evidence for an anti-inflammatory effect?”. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(7):3257–3265. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, Erdmann E, Massi-Benedetti M, Moules IK, Skene AM, Tan MH, Lefebvre PJ, Murray GD, Standl E, Wilcox RG, Wilhelmsen L, Betteridge J, Birkeland K, Golay A, Heine RJ, Koranyi L, Laakso M, Mokan M, Norkus A, Pirags V, Podar T, Scheen A, Scherbaum W, Schernthaner G, Schmitz O, Skrha J, Smith U, Taton J, P. R. investigators Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eming SA, Martin P, Tomic-Canic M. Wound repair and regeneration: Mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(265):265sr266. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faglia E, Favales F, Morabito A. New ulceration, new major amputation, and survival rates in diabetic subjects hospitalized for foot ulceration from 1990 to 1993: a 6.5-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(1):78–83. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falanga V. Wound healing and its impairment in the diabetic foot. Lancet. 2005;366(9498):1736–1743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goren I, Muller E, Schiefelbein D, Gutwein P, Seitz O, Pfeilschifter J, Frank S. Akt1 controls insulin-driven VEGF biosynthesis from keratinocytes: implications for normal and diabetes-impaired skin repair in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(3):752–764. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg EW, Li Y, Wang J, Burrows NR, Ali MK, Rolka D, Williams DE, Geiss L. Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1990–2010. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(16):1514–1523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M, Teoh H, Kajil M, Tsigoulis M, Quan A, Braga MF, Verma S. The effects of rosiglitazone on inflammatory biomarkers and adipokines in diabetic, hypertensive patients. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2012;17(4):191–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon D, University of Texas Mechanisms of Improved Wound Healing and Protein Synthesis of Insulin and Metformin. 2015 Retrieved 20 April 2015, from http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01666665.

- Hundal RS, Krssak M, Dufour S, Laurent D, Lebon V, Chandramouli V, Inzucchi SE, Schumann WC, Petersen KF, Landau BR, Shulman GI. Mechanism by which metformin reduces glucose production in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2000;49(12):2063–2069. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.12.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi Y, Matsui T, Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S. Metformin inhibits advanced glycation end products (AGEs)-induced renal tubular cell injury by suppressing reactive oxygen species generation via reducing receptor for AGEs (RAGE) expression. Horm Metab Res. 2012;44(12):891–895. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1321878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature. 1998;391(6662):82–86. doi: 10.1038/34184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Viberti G, Herman WH, Lachin JM, Kravitz BG, Yu D, Paul G, Holman RR, Zinman B, G. Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial Study Rosiglitazone decreases C-reactive protein to a greater extent relative to glyburide and metformin over 4 years despite greater weight gain: observations from a Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial (ADOPT) Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):177–183. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh TJ, DiPietro LA. Inflammation and wound healing: the role of the macrophage. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e23. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411001943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koliaki C, Doupis J. Incretin-based therapy: a powerful and promising weapon in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2011;2(2):101–121. doi: 10.1007/s13300-011-0002-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiba K, Nomura M, Nakaya Y, Ito S. Efficacy of glimepiride on insulin resistance, adipocytokines, and atherosclerosis. J Med Invest. 2006;53(1–2):87–94. doi: 10.2152/jmi.53.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M, Mueller JL, Vitari AC, Misaghi S, Fedorova A, Deshayes K, Lee WP, Hoffman HM, Dixit VM. Glyburide inhibits the Cryopyrin/Nalp3 inflammasome. J Cell Biol. 2009;187(1):61–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer S, Born F, Breidenbach A, Schneider A, Uhl E, Messmer K. Effect of C-peptide on wound healing and microcirculation in diabetic mice. Eur J Med Res. 2002;7(11):502–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Hsieh MJ, Chang SH, Lin YH, Liu SJ, Lin TY, Hung KC, Pang JH, Juang JH. Enhancement of diabetic wound repair using biodegradable nanofibrous metformin-eluting membranes: in vitro and in vivo. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(6):3979–3986. doi: 10.1021/am405329g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibovich SJ, Ross R. The role of the macrophage in wound repair. A study with hydrocortisone and antimacrophage serum. Am J Pathol. 1975;78(1):71–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Shen J, Bala MM, Busse JW, Ebrahim S, Vandvik PO, Rios LP, Malaga G, Wong E, Sohani Z, Guyatt GH, Sun X. Incretin treatment and risk of pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and non-randomised studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g2366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YC, Bhatt MP, Kwon MH, Park D, Na S, Kim YM, Ha KS. Proinsulin C-peptide prevents impaired wound healing by activating angiogenesis in diabetes. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(1):269–278. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima MH, Caricilli AM, de Abreu LL, Araujo EP, Pelegrinelli FF, Thirone AC, Tsukumo DM, Pessoa AF, dos Santos MF, de Moraes MA, Carvalheira JB, Velloso LA, Saad MJ. Topical insulin accelerates wound healing in diabetes by enhancing the AKT and ERK pathways: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loots MA, Lamme EN, Zeegelaar J, Mekkes JR, Bos JD, Middelkoop E. Differences in cellular infiltrate and extracellular matrix of chronic diabetic and venous ulcers versus acute wounds. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111(5):850–857. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovshin JA, Drucker DJ. Incretin-based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(5):262–269. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas T, Waisman A, Ranjan R, Roes J, Krieg T, Muller W, Roers A, Eming SA. Differential roles of macrophages in diverse phases of skin repair. J Immunol. 2010;184(7):3964–3977. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makdissi A, Ghanim H, Vora M, Green K, Abuaysheh S, Chaudhuri A, Dhindsa S, Dandona P. Sitagliptin exerts an antinflammatory action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):3333–3341. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfella R, Sasso FC, Rizzo MR, Paolisso P, Barbieri M, Padovano V, Carbonara O, Gualdiero P, Petronella P, Ferraraccio F, Petrella A, Canonico R, Campitiello F, Corte A Della, Paolisso G, Canonico S. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibition may facilitate healing of chronic foot ulcers in patients with type 2 diabetes. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:892706. doi: 10.1155/2012/892706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Leibovich SJ. Inflammatory cells during wound repair: the good, the bad and the ugly. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15(11):599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Jimenez MA, Aguilar-Garcia J, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Metlich-Medlich MA, Dietsch LJ, Gaitan-Gaona FI, Kolosovas-Machuca ES, Gonzalez FJ, Sanchez-Aguilar JM. Local use of insulin in wounds of diabetic patients: higher temperature, fibrosis, and angiogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(6):1015e–1019e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a806f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza R, DiPietro LA, Koh TJ. Selective and specific macrophage ablation is detrimental to wound healing in mice. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(6):2454–2462. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza RE, Fang MM, Ennis WJ, Koh TJ. Blocking interleukin-1beta induces a healing-associated wound macrophage phenotype and improves healing in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62(7):2579–2587. doi: 10.2337/db12-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza RE, Fang MM, Novak ML, Urao N, Sui A, Ennis WJ, Koh TJ. Macrophage PPAR-gamma and Impaired Wound Healing in Type 2 Diabetes. J Pathol. 2015 doi: 10.1002/path.4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza RE, Fang MM, Weinheimer-Haus EM, Ennis WJ, Koh TJ. Sustained inflammasome activity in macrophages impairs wound healing in type 2 diabetic humans and mice. Diabetes. 2014;63(3):1103–1114. doi: 10.2337/db13-0927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty P, Aljada A, Ghanim H, Hofmeyer D, Tripathy D, Syed T, Al-Haddad W, Dhindsa S, Dandona P. Evidence for a potent antiinflammatory effect of rosiglitazone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2728–2735. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty P, Hamouda W, Garg R, Aljada A, Ghanim H, Dandona P. Glucose challenge stimulates reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation by leucocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(8):2970–2973. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.8.6854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath N, Khan M, Paintlia MK, Singh I, Hoda MN, Giri S. Metformin attenuated the autoimmune disease of the central nervous system in animal models of multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2009;182(12):8005–8014. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak ML, Koh TJ. Phenotypic transitions of macrophages orchestrate tissue repair. Am J Pathol. 2013;183(5):1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286(3):327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putz DM, Goldner WS, Bar RS, Haynes WG, Sivitz WI. Adiponectin and C-reactive protein in obesity, type 2 diabetes, and monodrug therapy. Metabolism. 2004;53(11):1454–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangwala SM, Lazar MA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in diabetes and metabolism. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25(6):331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiber GE, Raugi GJ. Preventing foot ulcers and amputations in diabetes. Lancet. 2005;366(9498):1676–1677. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67674-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiber GE, Vileikyte L, Boyko EJ, del Aguila M, Smith DG, Lavery LA, Boulton AJ. Causal pathways for incident lower-extremity ulcers in patients with diabetes from two settings. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(1):157–162. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani O, Shabbak E, Aslani A, Bidar R, Jafari M, Safarnezhad S. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine the effects of topical insulin on wound healing. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2009;55(8):22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MR, Barbieri M, Marfella R, Paolisso G. Reduction of oxidative stress and inflammation by blunting daily acute glucose fluctuations in patients with type 2 diabetes: role of dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibition. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(10):2076–2082. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A, Hyttinen JM, Kaarniranta K. AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits NF-kappaB signaling and inflammation: impact on healthspan and lifespan. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89(7):667–676. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0748-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheen AJ. A review of gliptins for 2014. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16(1):43–62. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.978289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefelbein D, Seitz O, Goren I, Dissmann JP, Schmidt H, Bachmann M, Sader R, Geisslinger G, Pfeilschifter J, Frank S. Keratinocyte-derived vascular endothelial growth factor biosynthesis represents a pleiotropic side effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist troglitazone but not rosiglitazone and involves activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase: implications for diabetes-impaired skin repair. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74(4):952–963. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurmann C, Linke A, Engelmann-Pilger K, Steinmetz C, Mark M, Pfeilschifter J, Klein T, Frank S. The dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor linagliptin attenuates inflammation and accelerates epithelialization in wounds of diabetic ob/ob mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;342(1):71–80. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.191098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah Z, Kampfrath T, Deiuliis JA, Zhong J, Pineda C, Ying Z, Xu X, Lu B, Moffatt-Bruce S, Durairaj R, Sun Q, Mihai G, Maiseyeu A, Rajagopalan S. Long-term dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibition reduces atherosclerosis and inflammation via effects on monocyte recruitment and chemotaxis. Circulation. 2011;124(21):2338–2349. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.041418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Tan GS, Zhang K. Relationship of the Serum CRP Level With the Efficacy of Metformin in the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jcla.21803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorr RI, Ray WA, Daugherty JR, Griffin MR. Individual sulfonylureas and serious hypoglycemia in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(7):751–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay SK, Mishra M, Kumar H, Tripathi K. Effect of pioglitazone and rosiglitazone on mediators of endothelial dysfunction, markers of angiogenesis and inflammatory cytokines in type-2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2009;46(1):27–33. doi: 10.1007/s00592-008-0054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheimer E, Spravchikov N, Trebicz M, Gartsbein M, Accili D, Avinoah I, Nofeh-Moses S, Sizyakov G, Tennenbaum T. The regulation of skin proliferation and differentiation in the IR null mouse: implications for skin complications of diabetes. Endocrinology. 2001;142(3):1234–1241. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.3.7988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Huang X, Wang L. Pioglitazone inhibits the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9, a protein involved in diabetes-associated wound healing. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10(2):1084–1088. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(2):136–140. doi: 10.1038/ni.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]