Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Four new nonproprietary tests were recommended for use in the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center's Uniform Data Set Neuropsychological Battery. These tests are similar to previous tests but also allow for continuity of longitudinal data collection and wide dissemination among research collaborators.

METHODS

A Crosswalk Study was conducted in early 2014 to assess the correlation between each set of new and previous tests. Tests with good correlation were equated using equipercentile equating. The resulting conversion tables allow scores on the new tests to be converted to equivalent scores on the previous tests.

RESULTS

All pairs of tests had good correlation (ρ=0.68–0.78). Learning effects were detected for Logical Memory only. Confidence intervals were narrow at each point estimate, and prediction accuracy was high.

DISCUSSION

The recommended new tests are well correlated with the previous tests. The equipercentile equating method produced conversion tables that provide a useful reference for clinicians and researchers.

Keywords: Neuropsychology, test equating, cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, longitudinal

Introduction

The Alzheimer's Disease Centers supported by the NIH National Institute on Aging (NIA/NIH ADCs) collect data on subjects with cognitive impairment as well as normal cognition in order to study the characteristics and course of Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. The Uniform Data Set (UDS) was created in 2005 in order to collect standard clinical data on subjects at all of the ADCs on an approximately annual basis1. The UDS contains information on patient demographics, family history of dementia, health history, the neurological exam, functional and depression scales, the clinical diagnosis, and neuropsychological test results. Version 2 of the UDS neuropsychological battery (UDS2)2, which was in use from September 2005 to March 2015, contains several tests that could not be shared with researchers outside of the Alzheimer’s Disease Centers unless these researchers had licensing agreements of their own in place. This significantly limited the utilization of the UDS 2.0 by collaborators. In addition, some of the tests on the original battery lacked sensitivity to very early cognitive decline. With the implementation of a new version of the UDS (UDS3), the NIA/NIH ADC Clinical Task Force (CTF) sought to replace the UDS2 battery with a new battery composed of non-proprietary neuropsychological tests, allowing the entire battery to be shared more easily with the non-ADC-affiliated research community, and also included measures and scoring methods that would increase the possibility of detecting very minimal cognitive deficits.

In April 2008, the CTF created a UDS Neuropsychology Work Group. The Work Group was charged with providing recommendations for replacing proprietary tests in the UDS Neuropsychological Battery with similar non-proprietary tests. The Work Group recommended that four tests be replaced: the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)3, to be replaced by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)4; WMS-R Logical Memory IA-Immediate and IIA-Delayed Recall 5, to be replaced by Craft Story 21 Recall – Immediate and Delayed; WMS-R Digit Span5, to be replaced by Number Span; and the Boston Naming Test6, to be replaced by the Multilingual Naming Test (MINT) 7.

Once the new battery was implemented, the UDS would contain data from two neuropsychological batteries. In order to continue to analyze all available data, and in particular to facilitate longitudinal data analysis, the two batteries would need to be harmonized. A Statistical Advisory Group was convened and charged with (1) recommending a method for reconciling the two batteries and (2) developing a study to collect data to inform implementation of that method.

Methods

Strategies for equating tests

The Statistical Advisory Group identified several potential methods for analyzing data from both batteries. A direct imputation using equipercentile equating8 was selected as the best available approach. Equipercentile equating uses percentiles to provide equivalent scores from one test to another — in other in other words, a crosswalk. Equipercentile equating has several strengths that make it well-suited for equating of neuropsychological tests. First, all imputed scores are within the range of the test (e.g., one cannot impute a score of 31 on a test that ranges from 0 to 30). Second, it does not assume that test scores follow a prescribed distribution (e.g., a normal distribution); instead it relies on ranks. Third, it allows the tests to have different ranges (e.g., a test ranging from 0 to 30 can be equated with a test ranging from 0 to 32). Finally, it provides a single equivalent score for each value of the original test, which facilitates replication of results obtained using the equated scores. One limitation, however, is that the method does not take into account imputation error in subsequent analysis. In other words, the single-score imputation has a level of error that is not accounted for when the data are analyzed as if the converted score were an observed score.

Equipercentile equating has been used previously with the MMSE and other neuropsychological tests. For example, Fong et al. used equipercentile equating to create a crosswalk between the MMSE and the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status9, and Roalf et al. created a crosswalk between the MMSE and the MoCA 10.

In order to provide equivalent scores to investigators using NACC data, data from similar populations receiving both the new and the previous tests would need to be obtained and analyzed. The Crosswalk Study was thus planned.

The Crosswalk Study: Design

The goals of the Crosswalk Study were (1) to assess the correlation between the previous tests and the new tests and (2) if reasonably highly correlated, to create a crosswalk between the previous and new tests so that tests could be equated.

It is ideal to administer both the previous and new tests to those who come to the ADC for the first time (i.e., subjects who are making their initial visit). However, due to the much longer duration required to accrue data from a sufficient number of subjects making an initial visit, each ADC was asked to give new and returning subjects both the UDS2 neuropsychological battery and the new proposed tests. The order of the UDS2 battery versus new tests was randomized for each Center individually so that some subjects received the UDS2 battery first while others received the new tests first. Target strata for screening subjects into the study were determined in order to maximize recruitment of subjects with mild cognitively impairment (MCI) and mild to moderate dementia. Each ADC was asked to administer the test to 10 subjects with MMSE scores of 26–30, 20 subjects with MMSE scores of 21–25, 20 subjects with MMSE scores of 16–20, and 10 subjects with MMSE scores of 10–15. Lower MMSE scores were deemed not necessary for the crosswalk as it is difficult to administer the battery in its entirety to severely demented subjects, and these scores often show poor test-retest reliability due to within-subject variation 11,12 . These strata were set as targets for the ADCs in order to encourage a desirable distribution of scores; however, filling these strata exactly as prescribed was not necessary for evaluating correlation nor performing the test equating.

The study was conducted from December 2013 to April 2014. Standard UDS quality assurance (http://www.alz.washington.edu/WEB/qaqc_main.html) was performed on all UDS data collected as part of the Crosswalk Study. Additional parallel quality assurance was performed on the new test battery data. This process included ensuring that the data were within the allowable ranges, recalculating total scores from sub scores to confirm the provided total scores were correct, and identifying improbable combinations of test scores (e.g., Boston Naming Test score=5 and MINT score=30). Centers were asked to verify or correct all identified data-quality concerns, and those concerns that were not either corrected or verified as correct were excluded from the study (<1%).

The Crosswalk Study: Statistical analysis

Prior to data collection, thresholds for minimum acceptable correlation coefficients were established. As there are no agreed-upon cutoffs for correlation coefficients, we chose a conservative approach to categorizing correlation. Poor correlation was defined as a Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient <0.3, moderate correlation was a coefficient of 0.3 – 0.59, good correlation was a coefficient of 0.6 – 0.79, and very good correlation was a coefficient ≥0.8. Tests with correlation coefficients ≥0.6 would be candidates for equating, while a crosswalk of tests with weaker correlation would not be advisable or pursued further. The MoCA is often adjusted for educational attainment such that subjects with fewer than 12 years of education have an extra point added to their total score. Correlation coefficients were calculated for both raw and adjusted scores.

As both newly enrolled UDS subjects and returning subjects making follow-up visits were included in the study, there was potential for learning effects, especially for Logical Memory IA-Immediate and IIA-Delayed 13–15. Two types of learning effects were considered. The first type is learning how to take the test. To reduce bias of this type, about half of the participants in the study received the UDS2 battery first while others received the new battery first. The second type of learning effect, a differential learning effect, involves remembering specific details of the story. This type would artificially raise scores on the Logical Memory recall test (a test in UDS2), but not the Craft Story (a newly introduced test in UDS3), for subjects who had received the UDS2 neuropsychological battery previously. In order to evaluate differential learning effects, linear regression was performed with visit number as the independent variable and neuropsychological score as the dependent measure for all of the tests in the UDS2 battery. Visit number was treated as a categorical variable with the initial visit as the reference. Only subjects who scored a 25 or higher on the MMSE were included, as retesting effects are more pronounced, and thus easier to detect, in those with normal cognition compared to subjects with cognitive impairment16,17. A sensitivity analysis restricted the sample further to those with normal cognition by applying the additional exclusion of subjects with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) global score >018. Statistically significant differences for visit number would suggest the presence of retesting effects, and as such, the crosswalk would be performed using only data from visits that were not different from the initial visit.

Test pairs with correlation ≥0.6 were then equated using equipercentile equating with log linear smoothing19 using the “equate” package in R20. 95% confidence intervals were calculated using 100 bootstrap samples21.

Model diagnostics were performed to assess the accuracy of the equipercentile equating. First, before any equipercentile equating was performed, the data were split into training and validation data sets. 70% of the subject data was devoted to the training set, while 30% was used to test the accuracy of the single value estimation. After the equipercentile equating was performed on the training data, the score predicted by the equate method was subtracted from the observed score in the validation data. This value was then a measure of accuracy of the estimate determined from the equating. Only subjects scoring ≥10 on the MMSE were including in the model diagnostics, as this was the lowest score of interest in this study. Histograms of the difference between the predicted score and the observed score in the validation data set were created in order to show the distribution of the accuracy of the imputation.

All analyses were performed in R version 3.1.1. Research using the NACC database is approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Results

A total of 935 subjects from 24 ADCs contributed data to the Crosswalk Study (data downloaded on September 8, 2014). Of these, 102 were from initial visits, and the remaining 833 were from follow-up visits (median visit number=4, range=1–9). The randomization process produced 482 subjects receiving the new tests first and 453 receiving the UDS2 battery first. A majority of the subjects (73%) tested within the highest stratum of the MMSE; however, ample data were available in all of the targeted strata. 56% percent of subjects were women, and the median age was 75. Additional sample characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Alzheimer’s Disease Center subjects participating in neuropsychology test Crosswalk Study (n=935)

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Visit type | ||

| Initial visit | 102 | 11% |

| 1st follow-up visit | 159 | 17% |

| 2nd follow-up visit | 121 | 13% |

| 3rd follow-up visit | 96 | 10% |

| 4th follow-up visit | 94 | 10% |

| 5th follow-up visit | 99 | 11% |

| 6th follow-up visit | 104 | 11% |

| 7th follow-up visit | 93 | 10% |

| 8th follow-up visit | 67 | 7% |

| Battery order | ||

| UDS3 tests first | 482 | 52% |

| UDS2 tests first | 453 | 48% |

| MMSE score | ||

| 26–30 | 686 | 73% |

| 21–25 | 139 | 15% |

| 16–20 | 62 | 7% |

| 10–15 | 41 | 4% |

| <10 | 7 | 1% |

| Age at visit | ||

| <50 | 7 | 1% |

| 50–59 | 46 | 5% |

| 60–69 | 206 | 22% |

| 70–79 | 367 | 39% |

| 80–89 | 259 | 28% |

| 90+ | 50 | 5% |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 412 | 44% |

| Female | 523 | 56% |

| Race | ||

| White | 739 | 79% |

| Black/African American | 139 | 15% |

| Asian | 25 | 3% |

| American Indian/Alaska | 1 | <1% |

| Native | ||

| Mixed race | 31 | 3% |

| Education | ||

| No college | 165 | 18% |

| College | 392 | 42% |

| Graduate school | 378 | 40% |

UDS=Uniform Data Set

MMSE= Mini Mental State Examination

Correlation coefficients for each test are presented in Table 2. Non-parametric Spearman correlations were calculated to account for non-normally distributed data. All coefficients fell within the “good correlation” range (ρ ≥0.6), indicating that the tests had suitable correlation for test equating. Pearson coefficients were also calculated for comparison and were even higher than the non-parametric estimates, with several coefficients falling in the “very good” range (results not shown).

Table 2.

Spearman correlation coefficients for correlations between UDS2 and new neuropsychology battery tests

| Tests | ρ |

|---|---|

| MMSE, MoCA (raw) | 0.77 |

| MMSE, MoCA (education-adjusted) | 0.76 |

| BNT,MINT | 0.76 |

| Logical Memory IA-Immediate, Craft Story 21 Immediate Paraphrase | 0.73 |

| Logical Memory IIA-Delayed, Craft Story 21 Delayed Paraphrase | 0.77 |

| Digit, Number Span Forward-trials correct | 0.75 |

| Digit, Number Span Forward-length | 0.68 |

| Digit, Number Span Backward-trials correct | 0.78 |

| Digit, Number Span Backward-length | 0.72 |

MMSE=Mini Mental State Examination

MoCA= Montreal Cognitive Assessment

BNT=Boston Naming Test

MINT=Multilingual Naming Test

Learning effects were evaluated by exploring a potential difference in test score on the previous test (UDS2) by visit number. Among subjects with normal cognition, Logical Memory IIA-Delayed Recall test scores from visits 2,3,4, and 5 were not statistically significantly different from test scores from the initial visit; however, test scores from visits 6,7,8, and 9 were different from scores at the initial visit (p<.01 for all visits). Test scores from later visits were on average 2 – 4 points higher than test scores form the initial visit (see Supplementary Table 1). These results suggest that retesting effects became statistically and clinically significant at the sixth visit and thereafter. Thus, subjects making visit 6, 7, 8, or 9 as part of the Crosswalk Study were excluded from the equipercentile equating process for the Logical Memory tests. For all other tests, there was no evidence of retesting effects (p>.05 for all visits; data not shown). Therefore, all visits were included for the other tests (MMSE, Digit Span, and Boston Naming Test).

Six hundred fifty five subjects were randomly selected for the training set used to determine the equivalency tables, and 280 were retained for testing the accuracy of the equating. Of those 280, 268 scored ≥10 on the MMSE.

MoCA and MMSE

The raw MoCA scores and education-adjusted MoCA scores both had good correlation with the MMSE. Since the education-adjusted score is the main summary score for the MoCA, it was selected for use in the equate process.

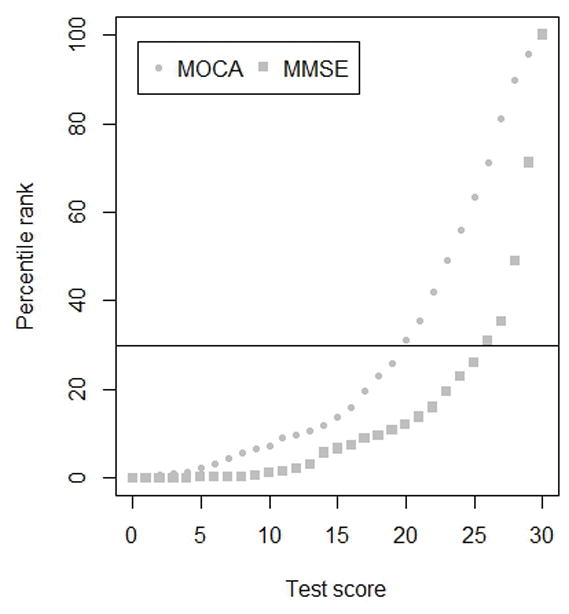

In general, MoCA scores equated with higher MMSE scores. For example, a score of 20 on the MoCA was equivalent to a score of 26 on the MMSE. Confidence intervals for lower scores were quite wide, with upwards of 4 points in each direction, mainly due to smaller sample size; however, confidence intervals for moderate and high scores were much closer, with 0 – 2 points in each direction. Results of the MOCA to MMSE equating are presented in Table 3 and Figure 1. All other conversion tables are provided as supplementary material (Supplementary Tables 2–8).

Table 3.

Equivalent MMSE score for a given MoCA score

| Education-adjusted MoCA | Equivalent MMSE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 0 | 6 | (4,9) |

| 1 | 9 | (7,11) |

| 2 | 10 | (8,12) |

| 3 | 11 | (9,13) |

| 4 | 12 | (10,14) |

| 5 | 12 | (10,14) |

| 6 | 13 | (11,15) |

| 7 | 14 | (12,16) |

| 8 | 15 | (13,17) |

| 9 | 15 | (13,17) |

| 10 | 16 | (14,18) |

| 11 | 17 | (15,19) |

| 12 | 18 | (16,20) |

| 13 | 19 | (17,21) |

| 14 | 20 | (18,22) |

| 15 | 21 | (19,23) |

| 16 | 22 | (21,24) |

| 17 | 23 | (22,25) |

| 18 | 24 | (23,25) |

| 19 | 25 | (24,26) |

| 20 | 26 | (25,27) |

| 21 | 27 | (26,27) |

| 22 | 28 | (27,28) |

| 23 | 28 | (28,28) |

| 24 | 29 | (28,29) |

| 25 | 29 | (29,29) |

| 26 | 29 | (29,30) |

| 27 | 30 | (30,30) |

| 28 | 30 | (30,30) |

| 29 | 30 | (30,30) |

| 30 | 30 | (30,30) |

MMSE=Mini Mental State Examination

MoCA= Montreal Cognitive Assessment

Figure 1.

MoCA scores and corresponding MMSE computed from the MoCA score, based on percentile rank

MMSE= Mini Mental State Examination

MoCA= Montreal Cognitive Assessment

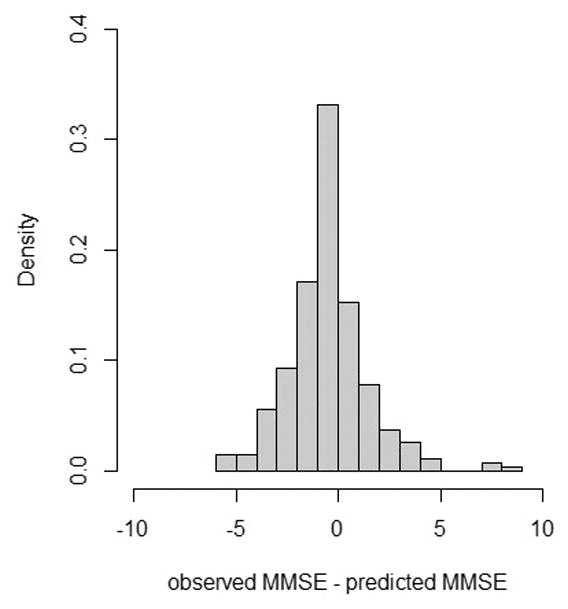

Observed scores on the MMSE were compared to those predicted by the equipercentile table using the validation sample. Of the observed scores, 33% exactly matched the predicted score from the table. Sixty-one percent of observed scores were within 1 point of the predicted score, and 83% were within 2 points. As shown in Figure 2, a few observed scores (n=10; <4%) were 5 or more points different from the predicted MMSE. While these extreme differences were rare, it is important to note their occurrence.

Figure 2.

Model prediction accuracy for the MoCA to MMSE crosswalk

MMSE= Mini Mental State Examination

MoCA= Montreal Cognitive Assessment

MINT and BNT

MINT scores and Boston Naming test (BNT) scores were very similar for lower scores, but for middle and higher scores, the MINT was often matched with lower BNT scores. This finding suggests that the MINT may be somewhat easier than the BNT, with subjects able to name upwards of three additional items on the MINT than on the BNT.

The differences between the observed BNT and those predicted from the conversion table were similar to those observed for the MoCA and MMSE: 22% of subjects in the validation set had observed scores equal to that predicted by the equipercentile table, 48% were within 1 point of the predicted score, and 65% were within 2 points.

Craft Story and Logical Memory

Only subjects making an initial visit or follow-up visit 1 – 4 (maximum total of five visits) were included in the equate process for Craft Story to Logical Memory. In general, Craft Story 21 paraphrase scores were determined to be about 0 – 2 points higher than Logical Memory scores for both IA-Immediate and IIA-Delayed recall. Confidence intervals for this crosswalk were tight across the range of scores, varying at most by 2 points from the equivalent value.

There was considerable variation in the paraphrase scores observed and those predicted by the conversion table for the immediate recall. Approximately 10% of subjects had exactly the same score, with 25% scoring within 1 point, 46% scoring within 2 points, and 72% scored within 5 points. The differences between observed and expected scores were slightly more for the delayed recall, where only 4% had exact matches, 19% were within 1 point, 30% were within 2 points, and 71% were within 5 points. For both immediate and delayed-recall tests, further restricting the sample to subjects scoring ≥24 on the MMSE did not improve accuracy (results not shown).

Number Span and Digit Span

Number Span and Digit Span scores were very closely matched. For both forward and backward tests, exact or nearly exact scores were equated for the length scores and trials correct scores. For the forward length score, the lower values were slightly different for Number Span and Digit Span but never by more than 1 point. All confidence intervals for these tests were extremely tight, varying at most by 1 point in either direction.

The range for the number and digit span is narrower than for the other tests, so a difference of 1 point is much more meaningful in this case. For the trials correct score, 78% on the forward test and 67% on the backward test had observed scores within 1 point of the predicted score. Similarly, for the digit span length score, 93% of the forward and 86% of the backward scores observed were within 1 point of the expected score, with 46% exact matches for both forward and backward.

Discussion

The UDS Neuropsychological Work Group succeeded in identifying non-propriety neuropsychological tests to replace those in the UDS2 battery. The new tests have “good” to “very good” correlation with the previous tests, and equivalent test equating returned single imputations for each of the new tests with reasonably tight confidence intervals.

The MoCA to MMSE conversion table generated from the Crosswalk Study data was very similar to those conversions presented by Roalf et al.10, varying by 1 point at most. The finding that MoCA scores equated with higher MMSE scores is consistent with studies that have found the MoCA to be a more sensitive measure than the MMSE among those with high cognitive function and in Alzheimer's dementia as well as other dementias 22–25.

The finding that most observed scores were within 1 or 2 points of the scores predicted by the conversion tables provides support for our estimation approach; however, additional steps to account for imputation error in subsequent data analysis should be considered.

Although large differences of 5 or more points were observed for some subjects, these were infrequent (4% for MoCA/MMSE) and were predominantly observed in the lower ranges of scores. Moreover, neuropsychological test scores are often analyzed using methods built around ranges of scores, such as score cutoffs for cross-sectional data and test composite scores and reliable change indices for longitudinal data. These methods allow for some variation in scores due to measurement error and within-person variability and instead focus on clinically meaningful changes in test scores over time.

Logical Memory and Craft Story 21 had the lowest prediction accuracy: the predicted score and the observed score differed by more than 2 points for more than half the sample. This could be due to differential learning effects not detected in the regression model or lack of experience among test administrators in scoring the new story. It could also be that there is more within-subject variability for this domain and/or specific test. Prediction accuracy in subjects scoring ≥24 on the MMSE was similar to that seen in the entire sample (results not shown); thus, there is little evidence for varying reliability by cognitive state.

This study did have potential weaknesses. First, the equipercentile method requires an anchor test. In other words, the equating process is designed so that one can convert the new test score to an equivalent score on the previous test but not the other way around. As the goal of the Crosswalk Study was to impute MMSE scores from MoCA scores until data on the MoCA accumulate and eventually replace the MMSE, this is a temporary limitation.

Second, the equipercentile method is a single imputation, and thus, it is not possible to account for the variation (i.e., error component) of the imputed scores. For example, if three subjects scored a 26 on the MoCA and their corresponding observed MMSE scores were 29, 29, and 30, we cannot adjust for the variation in the imputed MMSE scores. Alternative methods such as the Approximate Bayesian Bootstrap Imputation 26 could potentially address this issue. Additional analyses, using other conversion and imputation techniques, should be explored.

Third, subject characteristics such as age, sex, and education were not adjusted for in the equating process; instead, it is assumed that these characteristics affect the previous test and new test in similar ways. Thus, adjustment for these characteristics can be done at the discretion of the investigator.

Fourth, the NACC subject population has unknown generalizability to other populations. The high proportion of subjects with advanced education combined with limited data on those with non-White race and diverse ethnicity make it difficult to assess the potential external validity of the Crosswalk Study presented here. Nonetheless, the internal validity of the study was reasonable; the validation sample had observed scores similar to those predicted by the equipercentile equating tables.

A major strength of the Crosswalk Study was that the same subjects took both sets of tests, thus there were no differences between the subject populations taking the new and previous tests. Other potential sources of variation such as test order and learning effects were accounted for in the study design. In addition, the Crosswalk Study was performed using UDS subjects, and thus was representative of the inference population. Other strengths included the use of a validation sample and the estimate of confidence intervals.

In summary, the Crosswalk Study provides conversion tables that clinical researchers can refer to when assessing patients with the new battery. There is also potential for researchers to combine the previous and new UDS neuropsychological test battery data in order to analyze longitudinal data with minimal disruption.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the ADC clinic staff, data managers, and the participants who made this study possible.

The authors also thank the members of the Neuropsychology Work Group Advisory to the Clinical Task Force: Steven Ferris, Joel Kramer, David Loewenstein, Po Lu, Bruno Giordani, Felicia Goldstein, Dan Marson, John Morris, Dan Mungas, David Salmon, and Kathleen Welsh-Bohmer, as well as ex-officio members Nina Silverberg and Tony Phelps.

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976.

NACC data are contributed by the National Institute on Aging -funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI David Teplow, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), and P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD).

References

- 1.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(3):249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(2):91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wechsler A. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivanova I, Salmon DP, Gollan TH. The multilingual naming test in Alzheimer’s disease: clues to the origin of naming impairments. J Int Neuropsychol Soc JINS. 2013;19(3):272–283. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolen MJ, Brennan RL. Test Equating. New York: Springer; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong TG, Fearing MA, Jones RN, et al. The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status: Creating a crosswalk with the Mini-Mental State Exam. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2009;5(6):492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roalf DR, Moberg PJ, Xie SX, Wolk DA, Moelter ST, Arnold SE. Comparative accuracies of two common screening instruments for classification of Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy aging. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2013;9(5):529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gamaldo AA, An Y, Allaire JC, Kitner-Triolo MH, Zonderman AB. Variability in performance: Identifying early signs of future cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology. 2012;26(4):534–540. doi: 10.1037/a0028686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burton CL, Strauss E, Hultsch DF, Moll A, Hunter MA. Intraindividual variability as a marker of neurological dysfunction: a comparison of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2006;28(1):67–83. doi: 10.1080/13803390490918318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theisen ME, Rapport LJ, Axelrod BN, Brines DB. Effects of practice in repeated administrations of the Wechsler Memory Scale Revised in normal adults. Assessment. 1998;5(1):85–92. doi: 10.1177/107319119800500110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benedict RH, Zgaljardic DJ. Practice effects during repeated administrations of memory tests with and without alternate forms. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20(3):339–352. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.339.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodge HH, Wang C-N, Chang C-CH, Ganguli M. Terminal decline and practice effects in older adults without dementia: the MoVIES project. Neurology. 2011;77(8):722–730. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822b0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darby D, Maruff P, Collie A, McStephen M. Mild cognitive impairment can be detected by multiple assessments in a single day. Neurology. 2002;59(7):1042–1046. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.7.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howieson DB, Carlson NE, Moore MM, et al. Trajectory of mild cognitive impairment onset. J Int Neuropsychol Soc JINS. 2008;14(2):192–198. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris JC, Ernesto C, Schafer K, et al. Clinical dementia rating training and reliability in multicenter studies: the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study experience. Neurology. 1997;48(6):1508–1510. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.6.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livingston SA. Equating Test Scores with IRT. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albano A. equate: Statistical methods for test score equating. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Efron B. Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann Stat. 1979;7:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong Y, Lee WY, Basri NA, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment is superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination in detecting patients at higher risk of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr IPA. 2012;24(11):1749–1755. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freitas S, Simões MR, Alves L, Vicente M, Santana I. Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): validation study for vascular dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc JINS. 2012;18(6):1031–1040. doi: 10.1017/S135561771200077X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cameron J, Worrall-Carter L, Page K, Stewart S, Ski CF. Screening for mild cognitive impairment in patients with heart failure: Montreal cognitive assessment versus mini mental state exam. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs J Work Group Cardiovasc Nurs Eur Soc Cardiol. 2013;12(3):252–260. doi: 10.1177/1474515111435606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalrymple-Alford JC, MacAskill MR, Nakas CT, et al. The MoCA: well-suited screen for cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;75(19):1717–1725. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fc29c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple Imputation for Interval Estimation From Simple Random Samples With Ignorable Nonresponse. J Am Stat Assoc. 1986;81(394):366–374. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.