Abstract

Objective. To develop a set of explicit criteria for pharmacologically inappropriate medication use in nursing homes. Design. In an expert panel, a three-round Delphi consensus process was conducted via survey software. Setting. Norway. Subjects. Altogether 80 participants – specialists in geriatrics or clinical pharmacology, physicians in nursing homes and experienced pharmacists – agreed to participate in the survey. Of these, 62 completed the first round, and 49 panellists completed all three rounds (75.4% of those ultimately entering the survey). Main outcome measures. The authors developed a list of 27 criteria based on the Norwegian General Practice (NORGEP) criteria, literature, and clinical experience. The main outcome measure was the panellists’ evaluation of the clinical relevance of each suggested criterion on a digital Likert scale from 1 (no clinical relevance) to 10. In the first round panellists could also suggest new criteria to be included in the process. For each criterion, degree of consensus was based on the average Likert score and corresponding standard deviation (SD). Results. A list of 34 explicit criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in nursing homes was developed through a three-round web-based Delphi consensus process. Degree of consensus increased with each round. No criterion was voted out. Suggestions from the panel led to the inclusion of seven additional criteria in round two. Implications. The NORGEP-NH list may serve as a tool in the prescribing process and in medication list reviews and may also be used in quality assessment and for research purposes.

Keywords: Delphi technique, explicit criteria, general practice, inappropriate medication use, Norway, nursing homes, pharmacoepidemiology

Nursing home residents are frail and thus are especially prone to medication side effects and drug interactions.

This paper describes a three-round Delphi process, resulting in a list of drugs, dosages, and drug combinations to be avoided in nursing home residents for safety reasons.

The list may serve as a tool in the prescribing process and in medication reviews.

The list may also be used in quality assessment and for research purposes.

Introduction

The nursing home (NH) population of Western countries has become increasingly frail and ill, with specific and extensive needs in terms of health care. A recent UK survey found that 56% of the residents in 38 NHs died within a year of admission [1]. In Norway, only 29% of long-term residencies in NHs exceeded two years’ length in 2012 [2]. The majority of patients have multiple diseases with an average of four active diagnoses, four out of five residents have extensive needs for assistance in carrying out activities of daily living [2], and four out of five have dementia [3].

In general, the elderly population is more prone to medication side effects and drug–drug interactions [4]. Still there is often limited research evidence of effects and side effects, because most randomized, controlled trials on drug treatment are conducted in younger populations where comorbidities and polypharmacy are common exclusion criteria.

Various lists of explicit criteria for pharmacological inappropriateness have been developed to guide clinical practice and for assessing the extent of potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use in the elderly [5,6]. The Beers criteria were developed in the US in 1991 for NH residents [7] and later for a general population [8–10]. In Europe the STOPP-START criteria, designed for a general elderly population, were published in 2008 [11] and the German PRISCUS list was developed in 2010 [12]. The Norwegian General Practice (NORGEP) criteria are another list of explicit criteria for pharmacological inappropriateness, targeting home-dwelling elderly seen in general practice [13]. The NORGEP list consists of 36 statements including 21 single drugs and 15 drug–drug combinations. The list is partly based on the Beers’ criteria and it was derived through a three-round Delphi consensus process carried out in 2006 by a large expert panel consisting of geriatricians, GP specialists, and clinical pharmacologists. According to the NORGEP criteria, one-third of the total population of home-dwelling elderly in Norway was exposed to at least one PIM over the course of one year in 2008 [14]. A study from Norwegian NHs based on 28 of the 36 NORGEP criteria revealed a prevalence of PIM of 31% [15].

Some studies have shown an impact of inappropriate drug regimens on health care outcomes like hospital admission rates [16,17], self-perceived health status [18], and health-care utilization [19], while others have found no association between PIMs and the length of hospital stay [18]. Two studies found no association between PIMs and mortality [16,20]. In one study, inappropriate medication use increased the risk of adverse drug events when measured by the STOPP criteria; however, when applying the Beers criteria the correlation was not significant [21]. There is a need for more evidence as to the clinical relevance of the different lists of explicit criteria when it comes to effect on patient-related health outcomes. In the present study we aimed at establishing an updated and clinically relevant tool for assessing medication use in NH residents.

Material and methods

We conducted a three-round consensus process using the Delphi technique [22]. The Delphi technique is a structured communication technique where a panel of experts answers questions, most often in the form of a questionnaire, to which there are no scientifically proven correct answers [22]. The idea is that a group of experts, participating individually and anonymously, will give a more valid approach than experts one by one, and that consensus is reached through consecutive rounds in which participants are shown average responses made by the panel in previous rounds.

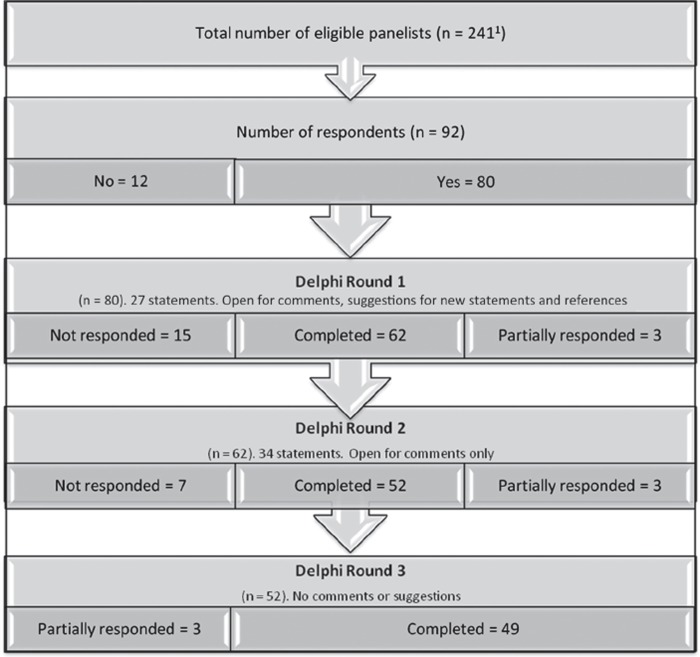

In August 2011 we invited by e-mail all members of the Norwegian Geriatrics Society (NGS, n = 122) and the Norwegian Society of Clinical Pharmacology (NFKF, n = 48) to participate. We also invited five pharmacists known to have particular expertise in medication safety, a convenience sample of NH physicians working in Oslo (n = 55), and all members of the Norwegian College of General Practitioners’ Reference Group for NH medicine (n = 11). Altogether, the number of eligible doctors in the five groups was 241. A total of 92 doctors responded to the invitation, and 80 agreed to participate (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Delphi process, setting, and participants. 1Nursing home physicians (n = 55), members of the Clinical Reference Group for Nursing Homes (n = 11), geriatricians (n = 122), clinical pharmacologists (n = 48), pharmacists (n = 5). Two of the doctors in the CRGNH were also nursing home physicians in Oslo and are represented in both groups here.

The three rounds of the Delphi process were completed between August 2011 and March 2012. The survey was conducted via the software SurveyMonkey® (Madison, WI, US), and the participants were sent an e-mail with a link to the survey. In first round they were exposed to 27 statements, suggesting criteria for inappropriate medication use in NH residents. The proposed criteria were based on the NORGEP criteria [13] and the knowledge and experience of the authors, who also carried out a comprehensive literature search for each suggested criterion. A few of the criteria from the NORGEP list have since their publication been taken off market and a few of them were shown to be of little clinical relevance in a subsequent pharmacoepidemiological national study [14] and these criteria were not included here. Other criteria given as single drug criteria in the NORGEP were here listed as drug classes (first-generation tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs], first-generation antihistamines, and neuroleptics). Each statement was presented with a brief explanation and up to three literature references. A commentary box was provided beneath each criterion. In addition, the participants were encouraged to suggest additional criteria and references.

A new literature search was performed before the authors decided whether or not to include criteria proposed by the panellists in the first round. The revised list of criteria was presented to the panellists in round two, in which average relevance scores from the first round were included. In the second round there was still room for comments but not for suggesting additional criteria. In the third round average scores for each criterion in round two were enclosed and the panellists were asked only to score without comments. A link for opting out was provided in each mail.

Main outcome was the panellists’ evaluation of the clinical relevance in an NH setting of each statement as scored on a digital Likert scale from 1 (no clinical relevance) to 10 (highly clinically relevant) [23,24].

Statistics

For each criterion, degree of consensus was based on the average Likert score and corresponding standard deviation (SD). SDs described the degree of discordance through the three rounds. Statements were included in the final list if the mean score minus one SD exceeded 5 in round three.

Subgroup analyses were performed comparing scores made by the NH physician group with corresponding scores made by the rest of the panel. Because frequency distributions were skewed towards the right and thus were not normally distributed, Mann–Whitney U-tests were employed to analyse differences in consensus between the two groups. The participants were assumed independent of each other, since the survey was conducted via Internet and not in a face-to-face group. Because of the large number of statistical tests significance was set to p < 0.01. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.

Ethics

The study protocol was presented to and approved by the Norwegian Social Sciences Data Services (NSD). Since there was no intervention as such and all correspondence and comments were anonymous the NSD assessed that the study did not need explicit approval by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics.

Results

We received altogether 92 responses from 34 Oslo nursing home physicians, nine members of the Reference Group for NH medicine (some of whom also were physicians in Oslo nursing homes), 13 members of NFKF, 38 members of NGF, and all five pharmacists. Of these, 80 participants agreed to take part in the survey out of which 52 completed all three rounds and 49 provided complete data (see Figure 1). The first round comprised 27 statements to be scored while the second and third rounds held a total of 34 statements, seven of which were based on the panellists’ suggestions in the first round. Five participants gave reasons for not completing the survey; the rest opted out by not responding to it. Of the 49 participants completing all three rounds, 15 (30.6%) were specialists in geriatrics, five (10.2%) specialists in clinical pharmacology, and five (10.2%) pharmacists, thus making up a group of 25. The other 24 (49.0%) respondents were NH physicians, some members of the General Practitioners’ Reference Group for NH medicine.

All proposed criteria were included in the final list (Table I). There was generally a high score for clinical relevance for most criteria, 26 of them receiving a mean score > 8.0 for the first round the criterion was included (Table II). For all criteria the relevance scores increased through the second and third rounds: 28 of the 34 criteria attained a final average score > 9 in round three. For all criteria the SD was reduced from first to third round, reflecting fewer outliers at the lower end of the scale. Three criteria with an average score < 8 in the first round had a final score > 9 in the third round, namely non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in general, anti-psychotics in absence of psychosis, and first generation of anti-histamines. Only the criterion regarding concurrent use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and bisphosphonates still had a score < 8 in round three.

Table I.

Norwegian General Practice Nursing Home (NORGEP-NH) criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly (> 70 years) nursing home residents.

| A: Single substance criteria | Comments, adverse effects |

| Regular use should be avoided | |

| 1. Combination analgesic codeine/paracetamol | Poor long-term effects. Constipation, sedation, falls |

| 2. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)1 | Anticholinergic effects, cardiotoxicity |

| 3. Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | High risk of side effects and interactions |

| 4. First-generation antihistamines2 | Anticholinergic effects, prolonged sedation |

| 5. Diazepam | Over-sedation, falls, fractures |

| 6. Oxazepam: Dosage > 30 mg/day | Over-sedation, falls, fractures |

| 7. Zopiklone: Dosage > 5 mg/day | Over-sedation |

| 8. Nitrazepam | Over-sedation, falls, fractures |

| 9. Flunitrazepam | Over-sedation, falls, fractures, addiction |

| 10. Chlometiazole | Poor safety record. Risk of cardiopulmonary death |

| 11. Regular use of hypnotics | Over-sedation, falls, fractures |

| B: Combination criteria | |

| Combinations to avoid | |

| 12. Warfarin + NSAIDs | Increased risk of bleeding |

| 13. Warfarin + SSRIs/SNRIs3 | Increased risk of bleeding |

| 14. Warfarin + ciprofloxacin/ofloxacin/erythromycin/clarithromycin | Increased risk of bleeding |

| 15. NSAIDs/coxibs4 + ACE-inhibitors5/AT2-antagonists6 | Increased risk of kidney failure |

| 16. NSAIDs/coxibs + diuretics | Reduced effect of diuretics, risk of heart and kidney failure |

| 17. NSAIDs/coxibs + glucocorticoids | Increased risk of bleeding, fluid retention |

| 18. NSAIDs/coxibs + SSRI/SNRIs | Increased risk of bleeding |

| 19. ACE-inhibitors/AT2-antagonists + potassium or potassium-sparing diuretics | Increased risk of hyperkalaemia |

| 20. Beta blocking agents + cardioselective calcium antagonists | Increased risk of atrioventricular block, myocardial depression, hypotension, orthostatism |

| 21. Erythromycin/clarithromycin + statins | Increased risk of adverse effects of statins |

| 22. Bisphosphonate + proton pump inhibitors | Increased risk of fractures |

| 23. Concomitant use of 3 or more psychotropics7 | Increased risk of falls, impaired memory |

| 24. Tramadol + SSRIs | Risk of serotonin syndrome |

| 25. Metoprolol + paroxetine/fluoxetine/bupropion | Hypotension, orthostatism |

| 26. Metformin + ACE-inhibitor AT2-antagonists + diuretics | Risk of impaired renal function and metformin-induced lactacidosis, especially in dehydration |

| C: Deprescribing criteria. Need for continued use should be reassessed8 | |

| 27. Anti-psychotics (incl. “atypical” substances9) | Frequent, serious side effects. Avoid long-term use for BPSD10 |

| 28. Anti-depressants | Limited effect on depression in dementia |

| 29. Urologic spasmolytics | Limited effect for urinary incontinence in old age Risk of anticholinergic side effects |

| 30. Anticholinesterase inhibitors | Temporary symptomatic benefits only. Frequent side effects |

| 31. Drugs lowering blood pressure | Hypotension, orthostatism, falls |

| 32. Bisphosphonates | Assess risk–benefit in relation to life expectancy |

| 33. Statins | Assess risk–benefit in relation to life expectancy |

| 34. Any preventive medicine | Assess risk–benefit in relation to life expectancy |

Notes: 1Amitriptyline, doxepine, chlomipramine, trimipramine, nortryptiline; 2dexchlorfeniramine, promethazine, hydroxyzine, alimemazine (trimeprazine); 3selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors/selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; 4cyclooxygenase-2-selective inhibitors; 5angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; 6angiotensin II receptor antagonists; 7from the groups centrally acting analgesics, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and/or benzodiazepines; 8this should be undertaken at regular intervals. For criteria 27–29, a safe strategy for re-evaluation is first to taper dosage, then stop the drug while monitoring clinical condition; 9risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, aripiprazole; 10behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia.

Table II.

Norwegian General Practice Nursing Home (NORGEP-NH) criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents.1 Mean scores with standard deviations and final score.

| Criterion: | Round 1 MS (SD) | Round 2 MS (SD) | Round 3 MS (SD) | Final score2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Single substance criteria. The following should be avoided for regular use whenever possible: | ||||

| 1. Combination analgesic with codeine/paracetamol | 6.5 (2.3) | 8.3 (1.8) | 8.5 (1.4) | 7.1 |

| 2. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) for depression | 7.2 (2.1) | 9.1 (1.2) | 9.5 (0.7) | 8.8 |

| 3. NSAIDs | 8.8 (2.0) | 9.8 (0.6) | 9.8 (0.5) | 9.3 |

| 4. First-generation antihistamines | 7.6 (2.4) | 8.6 (1.6) | 9.3 (1.0) | 8.3 |

| 5. Diazepam | 9.1 (1.7) | 9.6 (1.0) | 9.7 (1.0) | 8.7 |

| 6. Oxazepam: Dosage > 30 mg/day | 8.8 (1.5) | 9.4 (1.2) | 9.6 (1.0) | 8.6 |

| 7. Zopiklone: Dosage > 5 mg/day | 7.6 (2.4) | 8.1 (2.0) | 8.5 (1.8) | 6.7 |

| 8. Nitrazepam | 8.7 (1.9) | 9.5 (1.0) | 9.7 (0.8) | 9.1 |

| 9. Flunitrazepam | 9.3 (1.5) | 9.8 (0.6) | 9.9 (0.2) | 9.7 |

| 10. Chlometiazole | 8.6 (1.9) | 9.1 (1.2) | 9.2 (1.3) | 7.9 |

| 11. Regular use of hypnotics | N/A3 | 8.5 (2.0) | 9.2 (1.3) | 7.9 |

| B: Combination criteria. The following drug combinations should be avoided whenever possible: | ||||

| 12. Warfarin + NSAIDs | 9.6 (1.1) | 10.0 (0.1) | 10.0 (0.3) | 9.7 |

| 13. Warfarin + SSRI/SNRI | 7.3 (2.5) | 7.8 (1.5) | 8.1 (1.4) | 6.7 |

| 14. Warfarin + ciprofloxacin/ofloxacin/ erythromycin/ clarithromycin | 8.1 (2.4) | 9.1 (1.3) | 9.2 (1.1) | 8.1 |

| 15. NSAIDs/coxibs + ACE-inhibitors/AT2-antagonists | 9.1 (1.3) | 9.4 (1.1) | 9.6 (1.0) | 8.6 |

| 16. NSAIDs/coxibs + diuretics | 8.0 (2.2) | 8.6 (1.8) | 9.2 (1.6) | 7.6 |

| 17. NSAIDs/coxibs + glucocorticoids | 8.2 (2.1) | 9.2 (1.3) | 9.5 (0.9) | 8.6 |

| 18. NSAIDs/coxibs + SSRI/SNRIs | 7.2 (2.5) | 8.1 (1.9) | 8.8 (1.5) | 7.3 |

| 19. ACE-inhibitors/AT2-antagonists + potassium or potassium-sparing diuretics | 8.4 (2.0) | 9.2 (1.3) | 9.6 (0.8) | 8.8 |

| 20. Beta blocking agents + cardioselective calcium antagonists | 8.5 (2.0) | 9.3 (1.2) | 9.6 (0.8) | 8.8 |

| 21. Erythromycin/clarithromycin + statins | 8.3 (2.0) | 9.5 (0.9) | 9.6 (0.8) | 8.8 |

| 22. Bisphosphonate + proton pump inhibitors | 6.6 (2.4) | 6.8 (2.1) | 7.4 (1.8) | 5.6 |

| 23. Concomitant use of three or more psychotropic drugs | 9.6 (0.7) | 9.9 (0.5) | 10.0 (0.1) | 9.9 |

| 24. Tramadol + SSRIs | N/A2 | 8.5 (1.8) | 9.2 (0.9) | 8.3 |

| 25. Metoprolol + paroxetine/fluoxetine/bupropion | N/A2 | 8.9 (1.1) | 9.1 (1.0) | 8.1 |

| 26. Metformin + ACE-inhibitors/AT2-antagonists + diuretics | N/A2 | 8.4 (1.8) | 8.6 (1.4) | 7.2 |

| C: De-prescribing criteria. Need for continued use should be reassessed4 | ||||

| 27. Anti-psychotics | 7.6 (1.9) | 9.5 (1.4) | 9.7 (0.8) | 8.9 |

| 28. Anti-depressants | 8.6 (0.9) | 9.9 (0.2) | 10.0 (0.0) | 10.0 |

| 29. Urologic spasmolytics | 8.9 (1.6) | 9.7 (0.7) | 9.9 (0.4) | 9.5 |

| 30. Anticholinesterase inhibitors | 9.4 (1.1) | 9.8 (0.4) | 9.9 (0.7) | 9.2 |

| 31. Drugs that lower blood pressure | N/A2 | 9.9 (0.5) | 10.0 (0.2) | 9.8 |

| 32. Bisphosphonates | N/A2 | 9.7 (0.9) | 9.9 (0.4) | 9.5 |

| 33. Statins | 9.1 (1.3) | 9.7 (0.9) | 9.9 (0.5) | 9.4 |

| 34. General use of preventive medication | N/A2 | 9.6 (1.0) | 9.9 (0.4) | 9.5 |

Notes: 1The clinical relevance for each of the criteria is scored (from 1 to 10) by a panel of experts during a three-round consensus process. Figures are mean scores with standard deviation, MS (SD). 2Final score (column to the right) is mean score in round 3 minus 1 SD in round 3. To be included on final NORGEP-NH list, final score should be > 5. 3Not available, this denotes criteria first entered into the Delphi process in round 2. 4More details are given in Table I.

Through all three rounds 27 criteria were assessed three times by the panel while seven were scored twice, resulting in 95 means altogether (see Table II). When comparing mean scores made by NH physicians with those made by the group of geriatricians, clinical pharmacologists, and pharmacists (Mann–Whitney U-test with p < 0.01 to correct for the large number of tests) we only found a significant but small difference for five out of 95 mean scores. For one criterion there was a difference in round 1 (p = 0.002) and 3 (p = 0.004), but not round 2 (p = 0.06), namely the combination of NSAIDs with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors/selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs/SNRIs), where the nursing home physicians scored higher compared with the other group. The nursing home physicians were also more restrictive regarding NSAIDs in general (p = 0.001), statins (p = 0.001), and the combination of systemic NSAIDs/coxibs + systemic glucocorticoids (p = 0.008) in round 1 than the other group, but in later rounds no such difference was found.

Discussion

This three-round Delphi process, carried out among 80 participants, resulted in a list of 34 criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in NHs. Both the degree of consensus and the average scores for clinical relevance increased throughout the Delphi process. A corresponding trend was also seen in the NORGEP Delphi process [13]. A Delphi technique is said to be useful when a problem does not lend itself to precise analytical techniques, but can benefit from subjective judgements on a collective basis [22]. However, the initial 27 suggestions, and the seven criteria suggested by the panel, are all based on a combination of experience among both the authors and the panel and evidence from the literature. All suggestions have been scrutinized through literature searches and relevant references were provided to the panel during the consensus process.

The standard deviations of the means can be interpreted as a measure of the degree of discord among the participants. However, our data did not follow a normal distribution, as most participants’ scores were in the high range (right skewed distribution), especially in round 3, thus the SD will be inflated and not give an exact measure of the variance [25]. Still, a larger SD implies that a larger number of participants scored well below the mean. The Delphi technique in itself can be said to be conservative in the respect that it takes quite a lot for a proposed criterion to be rejected. The main reasons for the Delphi method to fail are imposing monitor views and preconceptions upon the respondent group, and ignoring and not exploring disagreements [22]. In order to avoid falling into these traps and including criteria for which there was substantial discord, we decided that a criterion be included in the final list only if (mean –1SD) > 5, so that not only was the mean score taken into consideration but also the degree of discord. In a case with a high degree of disagreement, as seen by a high SD, the average minus SD will thus be lower than in a case with a high general agreement (and thus a low SD). In this way, a controversial criterion will be less likely to be included in the list than a less controversial. Still no criterion was voted out through the three rounds.

Out of the 80 doctors who initially agreed to take part in the survey, 49 (61%) completed all three rounds. Of these 24 (49%) were nursing home physicians. The survey was lengthy, with a lot of text and many references, and this might have added to the withdrawal percentage. However, participants who completed all three rounds were in large part active throughout the process, providing numerous comments and suggestions for further references in both rounds one and two, thus giving the impression of an involved and independent panel.

It has been argued that one of the most critical aspects when designing a Delphi survey is the selection of qualified experts [22]. In some earlier surveys, among them the Beers consensus process and its later updates [7,8,10], the recruitment process differed from the present study in that the panel consisted of considerably fewer, hand-picked experts: 12 and six in the case of Beers criteria for NHs. The Delphi process leading to the NORGEP criteria, however, included a panel of 47 doctors [13]. At present there is no vocational training leading to a clinical speciality within NH medicine in Norway. Thus we do not know NH doctors’ level of expertise and experience. To check for robustness with regard to this matter we tested the average scores and the development of consensus throughout the survey's three rounds for these participants versus the rest of the panel. Using the Mann–Whitney U-test with p < 0.01 to correct for the large number of tests, we found only minor differences between the two groups of panellists. The final list of explicit criteria would have been unaltered had only either one of the two participant groups undertaken the survey.

The final 34 criteria can roughly be divided into three groups: single-substance criteria, drug–drug combination criteria, and criteria where regular consideration of “de-prescribing” is of uttermost importance in this population. The term “de-prescribing” can be defined as cessation of long-term therapy, supervised by a clinician [26]. It has been suggested that the term should be adopted internationally by researchers and practitioners engaged in this area [27]. Three criteria in this latter group concern preventive drug use when expected remaining life span is short: one concerning the use of preventive medication in general, the other two concerning the use of, respectively, bisphosphonates and statins. One can argue that the two latter criteria are redundant. However, since there was consensus to include all three criteria throughout the survey, they were included in the final list. A similar argument applies to using NSAIDs in different combinations, all of which could have been substituted by a single general criterion. However, since some of the combinations are particularly risky, the combination criteria still may serve a purpose in attracting attention to these potential threats.

The criterion concerning the combination of PPIs and bisphosphonates, suggested by one of the participants, was the only criterion with a mean score < 8 in the final round. Because this represented relatively new knowledge at the time of the survey, the lower score can be viewed as healthy scepticism, as one could argue that more research was needed. After this study was completed, new research has strengthened the evidence for the clinical relevance of avoiding this combination, which is associated with increased risk for fractures [28,29].

The criteria concerning concomitant use of SSRI/SNRI, and warfarin and NSAIDs respectively, do not distinguish between different SSRI/SNRI. However, different SSRI/SNRI represent a varying increase in the risk of bleeding when combined with anticoagulants due to differences in serotonin inhibition [30].

The Norwegian General Practice Nursing Home (NORGEP-NH) criteria resulting from this survey can be used as a reminder for NH physicians in their daily clinical work, and may also be useful for pharmacoepidemiological research and quality assessment work. In a previous study we found that one-third of the total population of home-dwelling elderly in Norway were exposed to at least one PIM over the course of one year, according to a modified version of the NORGEP criteria [14]. The present list, although primarily developed for the especially frail patients in nursing homes, can also be useful as a tool for GPs undertaking medication reviews for elderly patients outside institutions.

There is a need for more research on the effects of implementing the NORGEP-NH and similar lists with explicit criteria in clinical practice on outcomes like quality of life, morbidity, and mortality.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants of this Delphi study for their interest, effort and time. They would also like to thank statistician Magne Thoresen at the Department of General Practice/Family Medicine, Institute of Health and Society, University of Oslo, Norway.

Source of funding

The study was funded through a grant from the General Practice Research Fund (AMFF) hosted by the Norwegian Medical Association.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Kinley J, Hockley J, Stone L, Dewy M, Hansford P, Stewart R, et al. The provision of care for residents dying in UK nursing care homes. Age Ageing 2014;43:375–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mørk E, Sundby B, Otnes B, Wahlgren M, Gabrielsen B. Nursing and care services 2012. Statistics on services and recipients. Oslo: Statistics Norway; 2013. Report No.: 42/2013. http://www.ssb.no/en/helse/artikler-og-publikasjoner/pleie-og-omsorgstjenesten-2012 (accessed October 1, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Bergh S, Holmen J, Saltvedt I, Tambs K, Selbæk G. Dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing-home patients in Nord-Trondelag County. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2012; 132:1956–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obreli-Neto PR, Nobili A, de Oliveira Baldoni A, Guidoni CM, de Lyra DP jr, Pilger D, et al. Adverse drug reactions caused by drug–drug interactions in elderly outpatients: A prospective cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2012;68:1667–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy HB, Marcus EL, Christen C. Beyond the Beers criteria: A comparative overview of explicit criteria. Ann Pharmacother 2010;44:1968–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CB, Chan DC. Comparison of published explicit criteria for potentially inappropriate medications in older adults. Drugs Aging 2010;27:947–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, Reuben DB, Brooks J, Beck J. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. UCLA Division of Geriatric Medicine. Arch Intern Med 1991;151:1825–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly: An update. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1531–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers M. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: Results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel American Geriatric Society updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:616–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Kennedy J, O’Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008;46:72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thürmann PA. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: The PRISCUS list. Dtsch Atztebl Int 2010;107:543–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rognstad S, Brekke M, Fetveit A, Spigseth O, Bruun Wyller T, Straand J. The Norwegian General Practice (NORGEP) criteria for assessing potentially inappropriate prescriptions to elderly patients. Scand J Prim Health Care 2009;27:153–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyborg G, Straand J, Brekke M. Inappropriate prescribing for the elderly: A modern epidemic? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2012;68:1085–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen KH, Granas AG, Engeland A, Ruths S. Prescribing quality for older people in Norwegian nursing homes and home nursing services using multidose dispensed drugs. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klarin I, Wimo A, Fastbom J. The association of inappropriate drug use with hospitalisation and mortality: A population–based study of the very old. Drugs Aging 2005;22:69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert SM, Colombi A, Hanlon J. Potentially inappropriate medications and risk of hospitalization in retirees: Analysis of a US retiree health claims database. Drugs Aging 2010; 27:407–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu AZ, Liu GG, Christensen DB. Inappropriate medication use and health outcomes in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:1934–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick DM, Mion LC, Beers MH, Waller LJ. Health outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Res Nurs Health 2008;31:42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder G, Landi F, Liperoti R, Fialova D, Gambassi G, Bernabei R. Impact of inappropriate drug use among hospitalized older adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005;61:453–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton H, Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, O’Mahony D. Potentially inappropriate medications defined by STOPP criteria and the risk of adverse drug events in older hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1013–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linstone H, Turoff M. The Delphi Method: Techniques and applications. Newark: New Jersey Institute of Technology; 2002. Available from: http://is.njit.edu/pubs/delphibook/ (accessed October 1, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Matell MS, Jacoby J. Is there an optimal number of alternatives for Likert scale items? Study I: Reliability and validity. Educational and Psychological Measurement 1971: 657–74. [Google Scholar]

- Garland R. The mid-point of a rating scale: Is it desirable? Marketing Bulletin. 1991;2:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Swinscow TD. Statistics at square one, III: Standard deviation. BMJ 1976;1:1393–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S, Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older: A systematic review. Drugs Aging 2008; 25:1021–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alldred DP. Deprescribing: A brave new word? Int J Pharmacy Practice 2014;22:2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Youn K, Choi NK, Lee JH, Kang D, Song Hj, et al. A population-based case-control study: Proton pump inhibition and risk of hip fracture by use of bisphosphonate. J Gastroenterol 2013;48:1016–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA 2006;296:2947–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RELIS Northern Norway [Concomitant use of venlafaxine and warfarin.] Published August 9, 2011. http://relis.arnett.no/Utredning_Ekstern.aspx?Relis = 5&S = 2567 (accessed October 1, 2014).