Abstract

Background: Postpartum depression is prevalent among women who have had a baby within the last 12 months. Depression can compromise parenting practices, child development, and family stability. Effective treatments are available, but access to mental healthcare is challenging. Routine infant healthcare visits represent the most regular contact mothers have with the healthcare system, making pediatric primary care (PPC) an ideal venue for managing postpartum depression.

Methods: We conducted a review of the published literature on postpartum depression programs. This was augmented with a Google search of major organizations' websites to identify relevant programs. Programs were included if they focused on clinical care practices, for at-risk or depressed women during the first year postpartum, which were delivered within the primary care setting.

Results: We found that 18 programs focused on depression care for mothers of infants; 12 were developed for PPC. All programs used a screening tool. Psychosocial risk assessments were commonly used to guide care strategies, which included brief counseling, motivating help seeking, engaging social supports, and facilitating referrals. Available outcome data suggest the importance of addressing postpartum depression within primary care and providing staff training and support. The evidence is strongest in family practices and community-based health settings. More outcome data are needed in pediatric practices.

Conclusion: Postpartum depression can be managed within PPC. Psychosocial strategies can be integrated as part of anticipatory guidance. Critical supports for primary care clinicians, especially in pediatric practices, are needed to improve access to timely nonstigmatizing care.

Introduction

Postpartum depression has been termed the most underdiagnosed obstetrical complication in the United States, with a prevalence rate of 13%–19%, with rates varying depending on the postpartum period examined.1–4 Untreated, these symptoms are likely to persist5; their chronicity is associated with risk factors such as partner relationship conflict, stress and anxiety, and poor social networks.6 Maternal depression has significant consequences for the woman, her child, and the family. During infancy, important caregiving activities such as breastfeeding, sleep, adherence to well-child visit, and vaccine schedules can be compromised in depressed mothers.7–9 Among children younger than three years of age, maternal depression is associated with increased use of acute healthcare services, including emergency department visits.9 Maternal depression also influences infant attachment and bonding and can influence child development, leading to cognitive, social, emotional, and behavioral problems that last into adolescence.7,10,11 Among low-income families with young children, maternal depression is associated with household food insecurity.12

Fortunately, maternal depression is identifiable and treatable. Benefits for children have been documented in treatment studies conducted outside of primary care.7,13 Effective treatments for depression include a range of low- to high-intensity psychological interventions and pharmacological treatments.14 However, healthcare utilization patterns suggest under-recognition and detection,15–17 especially among poor women of color.18,19 Barriers to mental health treatment among these women are numerous and include myths about depression, time constraints, stigma, child care issues, and fears of provider judgment and social service involvement.18,20–22 The controversy around the safety of antidepressant medication use while breastfeeding influences the acceptability and comfort with medication by both women and their providers.23–25 These barriers, combined with health providers' reluctance to respond to maternal social–emotional and practical needs, are major obstacles in effectively linking these women to treatment.18

Primary care is an ideal setting for the identification and management of depression in mothers, particularly postpartum depression. Recommendations exist for screening and management of depression in primary care.26 Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) contains antidepressant medication management quality measures, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Psychiatric Association27 have established guidelines for treatment of depression among perinatal women. Because maternal depression is a risk factor for child development, the American Academy of Pediatrics has also called for the incorporation of detection and management of maternal depression in pediatric practices.28 However, few studies of depression management in primary care have focused on depression in mothers of infants.29,30

Most women of childbearing age (84%) visit their own primary care physician once yearly.31,32 Four of five women (but only 63% of women on Medicaid) receive a postpartum visit 4–6 weeks after delivery.33,34 However, the health providers most accessed by women with infants are pediatric primary care (PPC) clinicians. Within the first 15 months of life, 78.2% of children (and 63.6% of children in Medicaid) received six or more well-child visits.34,35 Thus, well-baby visits represent the most consistent contact mothers of infants have with the healthcare system.36,37

Several efforts to implement universal depression screening of mothers of newborns have had mixed results.38,39 Importantly, large-scale screening efforts that are not connected to follow-up do not influence treatment access or maternal outcomes.40,41 Screening is recommended only when staff-assisted supports are in place.2,26 To better understand factors that contribute to the success and/or failure of screening efforts, Yawn et al. undertook a review of postpartum depression screening programs.39 They identified eight programs with outcome data; these programs were delivered in a variety of settings and varied in scope. Of these, only four programs included procedures for addressing women with elevated screening scores. Most reported process outcomes related to screening, diagnosis, and treatment referral or initiation rates. Only two of four studies with outcome data found a positive benefit.42,43 Both of these programs included postscreening follow-up and management and treatment components within primary care. The review also found significant variation in physician or practice training and support.

To improve the identification and treatment of maternal depression, various initiatives have been implemented through national and state legislation.41,44 Efforts have included programs for managing postpartum depression (typically defined as depression onset within 12 months of childbirth) as part of primary care.39,43,45–47 Because of the frequency of pediatric visits during the first year of a child's life, an opportunity exists within PPC settings not only to identify but also to monitor and manage postpartum depression symptoms.48,49 Providing depression care within primary care settings is highly desirable to women, as it circumvents many attitudinal and practical barriers faced by mothers. This is especially the case when the venue is one in which routine care also occurs for their babies.50

The goal of this article is to delineate key elements of maternal depression management conducted within primary care settings, with a focus on the first year postpartum, a period when women tend to have frequent contact with primary care via their children. To better understand how key practice elements from these various programs for postpartum depression management could be integrated into PPC settings, we built upon the review by Yawn et al.39 Specifically, we systematically delineated practice elements within primary care settings. Unlike Yawn et al., we only focused on programs that delivered specific follow-up procedures for women with elevated depression screening scores within the primary healthcare context. We also included programs regardless of available outcome data because there were very few structured research studies. Policy initiatives related to this topic have spawned demonstration projects that could augment our understanding of practice elements potentially feasible in primary healthcare, outside of a research context. In addition, we examined whether the practice elements differed by context (e.g., adult vs. pediatric settings) and whether the context of their delivery influenced maternal or child outcomes. We focused on key aspects of these programs that might increase the success of identification and management of postpartum depression in primary care settings that provide routine well-child visits to highlight feasible approaches to the persistent problem of underidentification of maternal depression.

Materials and Methods

Two approaches were taken to identify relevant screening and management programs in primary care. The first was a review of the published literature on postpartum depression programs in primary care settings (pediatrics, family medicine, obstetrics–gynecology, community health centers). Second, we augmented our literature review with a Google search, with a focus on websites of major professional and caregiving/support organizations to identify relevant toolkits or programs related to the identification and treatment of postpartum or maternal depression. Secondary searches were also conducted by cross-referencing information or studies cited in key depression care programs.

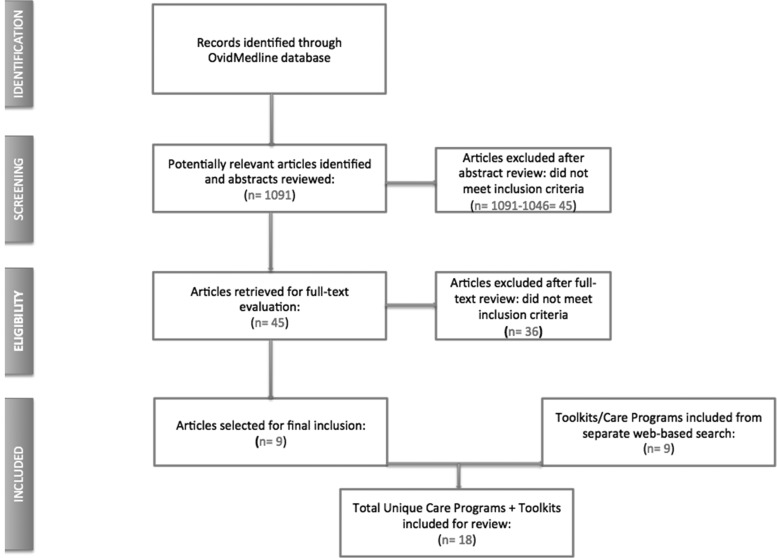

Literature review: We conducted a comprehensive computerized search of the MEDLINE database on the Ovid platform (Ovid SP; Ovid Technologies, Inc., Philadelphia, PA) between February 10 and February 26, 2015. The search strategy for MEDLINE combined concepts “Maternal Depression,” “Postpartum,” and “Postnatal” with “Intervention,” “Screening,” “Risk Assessment,” or “Management.” From these concepts, we selected the relevant medical index subject headings (MeSH terms: mother–child relationships, expecting mothers, and depressive disorder). Inclusion criteria were as follows: peer-reviewed articles written in English with a focus on clinical care practices for women identified as at-risk for or depressed during the first postpartum year. Programs were excluded if they (1) focused on at-risk or depressed mothers whose children were outside of 0–1 years of age or had special needs (e.g., infants in the NICU and infants with HIV), (2) provided care that occurred outside the primary healthcare context (e.g., early intervention programs, home visiting programs, and psychiatric settings), or (3) provided no specific follow-up care to individuals who screened positive for depression. We chose to exclude screening-only programs because screening without follow-up is considered controversial and unethical.14,26,38 In total, 1091 unique records were identified (Fig. 1). All search results were recorded in a reference management program (Endnote X7; Thomson Reuters, Carlsbad, CA). After reviewing these abstracts, we determined that 45 articles met criteria for a full text review. After full text review, nine articles (including one that was pulled based on cross-references42) met criteria for final inclusion; these nine articles described nine unique programs (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Postpartum depression care programs search flow chart.

Web-based search: The websites examined included the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, American Medical Association, American Psychological Association, American Psychiatric Association, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Academy for State Health Policy, National Institute of Mental Health, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Specific postpartum or maternal depression support websites included Clinicians Enhancing Child Health Practice-Based Research Network, Health Team Works, Illinois Academy of Family Physicians/Family Practice Education Network, and Postpartum Support International. In total, nine relevant toolkits or guidelines for identifying and managing postpartum depression were identified.

Abstraction of care features: In total, 18 programs were included in our review (Fig. 1); 9 from the literature review and 9 from web-based searches. Four of these 18 were initially selected for independent review by the study team to identify key elements of depression care. A final consensus set of features of postpartum depression care was then used to code all 18 programs. Features of care programs were organized according to key domains: screening/identification, assessment, care management, organization/system level tools that promote depression management, and the availability of outcome data. Using this code list, features of each care model were independently abstracted by two coders (D.W. and E.D.W.). Additional articles were pulled as needed by cross-referencing related publications to facilitate abstraction of program care features. Any discrepancies in coding were resolved by having the lead author review, and consensus was reached through team discussion.

Results

The 18 programs focused on depression care for mothers of infants are organized into two tables; the 9 programs from the literature review are asterisked. Table 1 includes 12 programs or toolkits that were developed for primary care settings where routine pediatric care is provided (i.e., pediatrics, n = 6 [one study also included family practice sites]; family medicine, n = 2; health centers, n = 4). All programs in pediatric practices and family medicine were based in the United States; all four programs in community-based health settings were internationally based. Table 2 includes six programs or toolkits that were developed for obstetrics and gynecology (ob-gyn) or generic toolkits developed for managing women with postpartum depression. All but one program51 in Table 2 are U.S. based. Below, we present the common elements of these programs.

Table 1.

Common Elements of Postpartum Depression Care in Pediatric Primary Care Settings

| Family medicine | Pediatrics | Community-based health settings | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAFP/FPEN60(screen and Tx option) | TRIPPD43,a | Practicing safety58 | START (Oregon)85,86 | AAP practicing safety87,88 | Dartmouth implementation manual (ABCD)55 | Stepped care model30,a(included both pediatric and family practices) | Improving women's health53,a | Trial of GP management61,a | PRISM62,89,a | RCT in Chile59,a | EPDS RCT program42,a | Total (12) | |

| Screening/identification | |||||||||||||

| Postpartum depression screening instrument | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 12 |

| EPDS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 9 | ||||

| PHO-2/PHQ-9 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||||

| Periodicity of screening | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 11 | |

| 2 weeks postpartum | X | X | X | 3 | |||||||||

| 4–6 weeks postpartum | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||||

| Crisis intervention/protocol | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||||||

| Assessment | |||||||||||||

| Diagnostic confirmation | (X) | X | X | X | 3 | ||||||||

| Structured interview: SCID/MINI | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||

| Risk assessment | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 9 | |||

| Treatment adherence | X | X | X | 3 | |||||||||

| Child-level assessment | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||

| Care management | |||||||||||||

| Dedicated care manager | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||

| Screen and refer | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||

| Screen and manage in practice | (X) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 11 | |

| Education | (X) | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | |||||

| Motivational interviewing | X | 1 | |||||||||||

| Referral to outside services | (X) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 8 | ||||

| Engage social supports | (X) | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | |||||

| Counseling | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||||||

| Medication management | (X) | X | X | 3 | |||||||||

| Organization/systems level | |||||||||||||

| Available mental health consultation | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||||||

| Decision support tools | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||||||

| Referral networks | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 10 | ||

| Staffing/workflow guidelines | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 7 | |||||

| Reimbursement guidelines | X | X | 2 | ||||||||||

| Outcome data | |||||||||||||

| Available outcomes | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||||

| Maternal | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||||||

| Child | X | 1 | |||||||||||

| Practice Feasibility/penetration | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 11 | |

Identified from literature search.

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; RCT, randomized control trial; X, presence of practice element.

Table 2.

Common Elements of Postpartum Depression Care in Adult Primary Care Settings

| Ob-Gyn | Guidelines/toolkits | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phone management52,a | PRAM51,a | Colorado OB toolkit56 | Health team work chart90 | MedEd57 | SAMHSA monograph91 | Total (6) | |

| Screening/identification | |||||||

| Postpartum depression screening instrument | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 |

| EPDS | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 |

| PHQ-2/PHQ-9 | X | 1 | |||||

| Periodicity of screening | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| 2 weeks postpartum | X | X | 2 | ||||

| 4–6 weeks postpartum | X | 1 | |||||

| Crisis intervention/protocol | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Assessment | |||||||

| Diagnostic confirmation | X | 1 | |||||

| Structured interview: SCID/MINI | 0 | ||||||

| Risk assessment | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Treatment adherence | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Child-level assessment | 0 | ||||||

| Care management | |||||||

| Dedicated care manager | X | 1 | |||||

| Screen and refer | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Screen and manage in practice | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Education | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Motivational interviewing | X | X | 2 | ||||

| Referral to outside services | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Engage social supports | X | X | 2 | ||||

| Counseling | X | 1 | |||||

| Medication management | X | X | 2 | ||||

| Organization/systems level | |||||||

| Available mental health consultation | X | X | 2 | ||||

| Decision support tools | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Referral networks | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Staffing/workflow guidelines | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Reimbursement guidelines | X | X | 2 | ||||

| Outcome data | |||||||

| Available outcomes | 0 | ||||||

| Maternal | 0 | ||||||

| Child | 0 | ||||||

| Practice feasibility/penetration | X | X | 2 | ||||

Identified from literature search.

X, presence of practice element.

Screening for depressive symptoms

All programs utilized a screening tool to facilitate identification of women with high levels of depressive symptoms (Tables 1 and 2). Several screening tools were used or endorsed; however, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was the most common (found in 75% in PPC; 100% in ob-gyn and generic toolkits). Cut points used to identify those at risk for depression varied, with a score of 10 being the most commonly used. Significant variation existed in periodicity of screening, with screenings commonly recommended at 2 weeks through 6 months postpartum. In PPC settings, screenings at 4–6 weeks are most frequently seen (Table 1); in ob-gyn settings, 2 weeks are relatively more common.

Assessment

Suicide risks are examined as part of the most common screening tools (e.g., both EPDS and the Patient Health Questionnaire contain suicide items). Approximately half the programs identified specific crisis protocols for handling suicidality,43,52–58 with an emphasis in some for providers to be observant about the presence of rare but serious indicators of psychotic symptoms and thoughts of infant harm.43,52

Only 5 of the 18 programs (28%) followed positive screens with a diagnostic confirmation. Three programs within PPC (Table 1) followed a positive screen with a structured psychiatric interview54,59 or an additional tool to confirm diagnosis.39 Two other programs recommended referral to a mental health provider for diagnostic confirmation before treatment.56,60

In PPC settings, 75% of the programs included a psychosocial risk assessment, typically done through an interview (Table 1); two-thirds of adult primary care and generic toolkits also conducted or recommend risk assessments as part of postpartum depression care management (Table 2). Although risk assessment is typically done through an interview, a standardized risk assessment tool was specifically used in one program.51 Ongoing monitoring of treatment adherence was uncommon in PPC settings, where only three programs monitored treatment adherence as part of care.43,54,59 By contrast, all three ob-gyn settings monitored the treatment adherence of women who had positive screens.51,52,56 Only two programs in PPC conducted child-level assessments. None of the programs in adult primary care or the generic toolkits recommended child assessment.

Care management of elevated postpartum depressive symptoms

Few of the 18 programs (17%) used or recommended use of a dedicated care manager to manage women with elevated depression symptoms. Care strategies commonly used can be broadly divided into “screen and refer” versus “screen and manage” approaches, with one toolkit,60 suggesting use of either strategy based on practice capacity.

Few PPC programs used a “screen and refer” only approach. Rather, a “screen and manage” approach was more common, which included interventions such as counseling (typically nondirective or about lifestyle choices), psychoeducation about postpartum depression, motivating help seeking, engaging social supports, and referral to outside services as needed. None of the interventions involved psychotherapy; medication management was found in two family medicine-based programs43,60 and one health center.59 By contrast, ob-gyn or other settings were equally likely to use either a “screen and refer” or “screen and manage” approach. Management approaches included education, medication, motivating help-seeking outside practice, and engaging social supports.

Implementation supports at organizational/practice level

Implementation supports typically included training provided about postpartum depression as part of the initial program startup. However, ongoing organizational-level/practice-level support to implement postpartum depression screening and management was highly variable. Mental health consultation was available only in one-third of PPC-based programs and in two of the three ob-gyn settings. Referral networks were the most common strategy to support primary care practitioners across all settings (83% in PPC and 67% in other settings), followed by staffing guidelines (58% in PPC and 50% in other settings). Reimbursement strategies were relatively uncommon, especially in PPC.

Outcome data

Across the 18 programs, only 6 (all within PPC settings and all randomized control trials [RCTs]) reported outcome data, with only one extending beyond maternal health to child health.42 Four of these six studies showed health benefits to the mother, with improved mental health outcomes for the mother posttreatment,61 at 3 months,59 6 months,42 or 12 months.43 However, effects diminished over time in two studies.42,59 Reduction in postpartum depression was reported at 12 months in the largest family practice-based effectiveness trial conducted in the United States to date. These benefits were found with relatively modest nursing support focused on medication adherence and side effects.43 Findings were negative in both studies that examined secondary outcomes related to parenting stress, partner satisfaction, or infant health.42,43 In a three-arm RCT study based in Australia, women in the general practitioner-only condition were more likely to remain above the clinical cutoff for depression when compared to those who received adjunctive Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)-based counseling provided by a postnatal nurse or counseling provided by a psychologist. This finding supports the added benefit of adjunctive CBT-based counseling.

We compared the two negative studies with those that found positive outcomes to better understand contextual factors that may influence the outcomes of the two negative studies. The first negative study, called the PRISM study,62 used a cluster-randomized design to test the effectiveness of a complex and multifaceted primary care and community-based strategy to facilitate the identification and support of new mothers across an Australian state. Compared to control women, those in the intervention arm did not show improvement in physical health scores or reduction in depression 6 months postbirth. In this program, maternal and child health nurses were not integrated with primary care services. Other potential barriers included reimbursement mechanisms based on a fee for service system, role diffusion of health nurses due to role shifts, and the lack of ongoing support for general practitioners and community building. In the second negative study based in both U.S. pediatric and family practices, a stepped care intervention increased women's awareness of their depression and their likelihood of getting treatment; however, no benefit was found for duration of treatment, health, or work outcomes.54 A major limitation in the program design of this study was the requirement for a diagnostic confirmation by a mental health specialist for study enrollment. This introduced a significant bias, because fewer than a third of mothers who screened positive followed up with positive diagnostic assessments.

By contrast, the four studies that found benefits for maternal health included specific follow-up procedures that were all based within the primary care site. In these studies, less than 10% of the women who screened positive were referred for treatment outside the primary care practices. Key implementation supports were in place, including extensive and often tailored staff training and decision support tools to guide depression management. Ongoing mental health consultation was available to support management at three of these sites.42,59,61

Discussion

Maternal depression is a public health issue because of the negative consequences on the mother, her child, and her family. Despite numerous efforts, linking new mothers to specialty mental health for depression treatment is challenging because of attitudinal, logistic, and structural barriers. These barriers are amplified among socially disadvantaged women, putting those most vulnerable at highest risk for unmet treatment needs and adverse long-term outcomes.

This review identified 18 unique programs or toolkits for managing postpartum depression within primary care. Care strategies were highly similar across both pediatric and adult settings. Two-thirds of the programs reviewed were based in settings that provided routine care for infants. This finding supports the notion that PPC is ideally suited for managing postpartum depression. Data are strongest for programs within family practices and community-based health settings. In particular, two large-scale multistate initiatives focused on family practice networks have been fielded within the United States,43 with available data showing positive benefits on maternal health.43 However, the majority of young children in the United States are seen by pediatricians. To date, the only rigorous U.S. study involving pediatric practices was compromised because the sample was biased by the requirement of a research-based diagnostic tool for study randomization54; all other programs have involved demonstration projects with no outcome data. Thus, while the evidence suggests the feasibility of managing postpartum depression within pediatric practices, outcome data are needed. Unlike family practices and health centers that are set up to serve both children and adults, incentive structures and organizational supports must be established to support postpartum depression management programs in pediatric practices.28,53

Among the primary care programs reviewed, a “screen and manage” approach was common, where depression in mothers was addressed to varying degrees within the practice where screening occurred. Interestingly, very few programs followed a positive screen with a confirmatory diagnostic interview. Psychosocial assessments, usually conducted via interview, were more commonly used as a basis to determine follow-up care strategies. Psychosocial risk assessments are considered both an opportunity to contextualize depressive symptoms within current life circumstances and to develop a successful management plan.51,63,64 Thus, despite USPSTF recommendations to follow positive screens with confirmatory diagnosis, this is not typical in the programs we reviewed. In fact, requiring a diagnosis as a precursor to care provision was a deterrent for many women.39,54 Few women with positive depression screens in primary care settings followed up with outside referrals, especially for diagnostic assessments.27,39,54 Although it can be important to differentiate a positive screen from a depression diagnosis for individuals with complex mental health issues, the benefits of skipping this step may outweigh the risk of excluding women who endorse significant distress from the benefits of an intervention, especially among less clinically complex populations typically present in primary care.39 A preventive approach, through which women with elevated symptoms and less complicated risk profiles could receive care, especially brief evidence-based interventions, is an important option. For women with more complex clinical profiles, coordination and/or linkages to specialty care are warranted.

Our review showed that various aspects of care were provided by a range of professionals, including the physician, nurses, midwives, or care managers. The primary care physician's role was most often to identify presence and degree of depression and to support the execution of a management plan through collaboration with allied health professionals and mental health specialists. Management within primary care typically involved brief counseling, motivating help seeking, engaging social supports, and facilitating mental health referrals. Few of these programs provided treatments; when treatment was provided, they involved primarily medication management. Available systems or organizational tools were typically in place to support depression care. Aside from initial training, development of referral networks is the most common type of organizational/practice support. Onsite or ongoing mental health consultation and decision support tools were less common though important strategies that were used in the programs with positive outcome data.39,42,59,61 Incentives or reimbursement strategies were surprisingly rarely addressed, despite being identified as a major barrier for implementing such programs, especially in pediatric practice settings where mothers are not the identified patients.

Psychosocial interventions have been shown to be effective for adult depression, including those targeting postpartum depression.65–68 Despite the openness of mothers to nonpharmacological management of their depression within primary care,69,70 programs relied primarily on nondirective counseling. It is likely that the implementation of these psychosocial interventions hinges on the availability of both trained providers and reimbursement mechanisms. Increasingly, evidence exists for the delivery of psychosocial interventions by lay and nonspecialty providers.61,71–74 With training and support, such strategies could potentially be adapted for delivery within PPC settings by allied health professionals, nurses, and physicians.75 The availability of psychosocial interventions within primary care is particularly important for depressed women of infants, who understandably have concerns about antidepressant use, especially while nursing. Making brief psychosocial intervention options available within primary care could increase access to timely nonstigmatizing care for at-risk women and reduce the potential negative consequences for their child and family.

Efficacy trials support the benefits of integrating behavioral healthcare for depression within primary care29, however, challenges and variability in implementing such collaborative care models persist.76,77 Stepped care approaches, a variant of collaborative care, have been proposed to increase the likelihood of care access for depressed mothers within PPC, where different levels of care are administered based on case severity. By moving from low to high levels of care, encouraging providers to manage low-level mental health needs and referring those with complex needs, efficiency and cost-effectiveness could be maximized.39,54,78 A stepped care model, with comprehensive, one-stop early intervention services, has the advantage of addressing two key barriers, namely, limited availability of specialty mental health services and women's challenges with the logistics and attitudes about mental healthcare. However, outcome data for such models within pediatric practice settings are needed.

The emphasis on quality in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) creates an opportunity to focus attention on new models to optimize care for managing postpartum depression in PPC settings. While family practitioners have led the way in addressing this public health problem, pediatricians, who provide the majority of routine care for young children in the United States, have lagged behind. Because postpartum depression is a maternal condition, pediatricians are additionally challenged by legal, ethical, and reimbursement issues.79 Barriers related to pediatricians' attitudes about managing depression in the mothers of their young patients and a lack of efficacy in identification and management of postpartum depression must also be addressed.79–84

Building on the National Quality Forum's recommendation to screen for maternal depression, models that expand upon existing strategies found in this review are important. In particular, supporting pediatric providers through targeted training, collaboration, and/or integration of behavioral health providers is key. Care models that emphasize a responsive, patient-centered, and evidence-based strategy for addressing this highly treatable maternal condition can promote health and long-term well-being of mothers and their children.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephen Maher, MSIS, Assistant Director, Content Management and Scholarly Communications at the NYU Health Sciences Library. This research was supported by NIMH P30 MH09 0322.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Dave S, Petersen I, Sherr L, Nazareth I. Incidence of maternal and paternal depression in primary care: A cohort study using a primary care database. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:1038–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myers ER, Aubuchon-Endsley N, Bastian LA, et al. Efficacy and safety of screening for postpartum depression. Comparative Effectiveness Review 106 (Prepared by the Duke Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10066-I.). AHRQ Publication No. 13-EHC064-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, April 3, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes: Summary. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2005:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—A meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatr 1996;8:37–54 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horwitz SM, Kelleher KJ, Stein RE, et al. Barriers to the identification and management of psychosocial issues in children and maternal depression. Pediatrics 2007;119:e208–e218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kingsbury AM, Hayatbakhsh R, Mamun AM, Clavarino AM, Williams G, Najman JM. Trajectories and predictors of women's depression following the birth of an infant to 21 years: A longitudinal study. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:877–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field T. Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: A review. Infant Behav Dev 2010;33:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregory EF, Butz AM, Ghazarian SR, Gross SM, Johnson SB. Are unmet breastfeeding expectations associated with maternal depressive symptoms? Acad Pediatr 2015;15:319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Scharfstein D, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and children's receipt of health care in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics 2005;115:306–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson G, Frey K, Panagiotides H, Yamada E, Hessl D, Osterling J. Infants of depressed mothers exhibit atypical frontal electrical brain activity during interactions with mother and with a familiar, nondepressed adult. Child Dev 1999;70:1058–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kingston D, Tough S, Whitfield H. Prenatal and postpartum maternal psychological distress and infant development: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2012;43:683–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: A cluster RCT. Pediatrics 2015;135:e296–e304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne P, Poh E, et al. Psychopathology and functioning among children of treated depressed fathers and mothers. J Affect Disord 2014;164:107–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The treatment and management of depression in adults. Available at: https://wwwniceorguk/guidance/cg90 (accessed June17, 2015) [PubMed]

- 15.Institute of Medicine. Committee on crossing the quality chasm: Adaptation to mental health and addictive disorders. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. Washington, DC: National Academic Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leiman JM, Fund C. Selected facts on US women's health: A chart book. New York, NY: Commission, College of Physicians & Surgeons, Columbia University, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sim LJ, England MJ. Depression in parents, parenting, and children: Opportunities to improve identification, treatment, and prevention. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: A qualitative systematic review. Birth 2006;33:323–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miranda J, Green BL. The need for mental health services research focusing on poor young women. J Ment Health Policy 1999;2:73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrams LS, Dornig K, Curran L. Barriers to service use for postpartum depression symptoms among low-income ethnic minority mothers in the United States. Qual Health Res 2009;19:535–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heneghan AM, Mercer M, DeLeone NL. Will mothers discuss parenting stress and depressive symptoms with their child's pediatrician? Pediatrics 2004;113:460–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teng L, Blackmore ER, Stewart D. Healthcare worker's perceptions of barriers to care by immigrant women with postpartum depression: An exploratory qualitative study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2007;10:93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Battle CL, Salisbury AL, Schofield CA, Ortiz-Hernandez S. Perinatal antidepressant use: Understanding women's preferences and concerns. J Psychiatr Pract 2013;19:443–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yonkers KA, Blackwell KA, Forray A. Antidepressant use in pregnant and postpartum women. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2014;10:369–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scalea TL, Wisner KL. Pharmacotherapy of postpartum depression. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2009;10:2593–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:784–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: A report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31:403–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Earls MF; The Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Clinical report—Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2010;126:1032–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: A cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:2314–2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gjerdingen D, Katon W, Rich DE. Stepped care treatment of postpartum depression: A primary care-based management model. Womens Health Issues 2008;18:44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salganicoff A, Ranji UR, Wyn R. Women and health care: A national profile: Key findings from the Kaiser Women's Health Survey. Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Depression among women of reproductive age. Available at: http://wwwcdcgov/reproductivehealth/Depression/2013 (accessed August8, 2015)

- 33.Scholle SH, Haskett RF, Hanusa BH, Pincus HA, Kupfer DJ. Addressing depression in obstetrics/gynecology practice. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2003;25:83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Committee for Quality Assurance. The State of Health Care Quality 2013. Washington, DC: NCQA, 2013. https:www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/Newsroom/SOHC/2013/SOHC-web_version_report.pdf Accessed July21, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leiferman JA, Dauber SE, Scott K, Heisler K, Paulson JF. Predictors of maternal depression management among primary care physicians. Depress Res Treat 2010;2010 pp. 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Kitzman HJ, Wadkins HI, Conwell Y. Detection of postpartum depressive symptoms by screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics 2004;113:551–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perfetti J, Clark R, Fillmore C-M. Postpartum depression: Identification, screening, and treatment. WMJ 2004;103:56–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thombs BD, Arthurs E, Coronado-Montoya S, et al. Depression screening and patient outcomes in pregnancy or postpartum: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2014;76:433–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yawn BP, Olson AL, Bertram S, Pace W, Wollan P, Dietrich AJ. Postpartum depression: Screening, diagnosis, and management programs 2000 through 2010. Depress Res Treat 2012;2012 pp. 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bryan T, Georgiopoulos A, Harms R, Huxsahl J, Larson D, Yawn B. Incidence of postpartum depression in Olmsted County, Minnesota. A population-based, retrospective study. J Reprod Med 1999;44:351–358 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kozhimannil KB, Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Busch AB, Huskamp HA. New Jersey's efforts to improve postpartum depression care did not change treatment patterns for women on medicaid. Health Aff 2011;30:293–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leung SS, Leung C, Lam T, et al. Outcome of a postnatal depression screening programme using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: A randomized controlled trial. J Public Health 2010:33:292–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yawn BP, Dietrich AJ, Wollan P, et al. TRIPPD: A practice-based network effectiveness study of postpartum depression screening and management. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:320–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelletier H, Abrams M. The North Carolina ABCD Project: A new approach for providing developmental services in primary care practice. Washington, DC: National Academy for State Health Policy, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 45.LaRocco-Cockburn A, Reed SD, Melville J, et al. Improving depression treatment for women: Integrating a collaborative care depression intervention into OB-GYN care. Contemp Clin Trials 2013;36:362–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melville JL, Reed SD, Russo J, et al. Improving care for depression in obstetrics and gynecology: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:1237–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.University of Washington. Depression attention for women now (DAWN). Available at: http://wwwdawncareorg (accessed March30, 2015)

- 48.Liberto TL. Screening for depression and help-seeking in postpartum women during well-baby pediatric visits: An integrated review. J Pediatr Health Care 2012;26:109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mishina H, Takayama JI. Screening for maternal depression in primary care pediatrics. Curr Opin Pediatr 2009;21:789–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuosmanen L, Vuorilehto M, Kumpuniemi S, Melartin T. Postnatal depression screening and treatment in maternity and child health clinics. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2010;17:554–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Priest S, Austin M-P, Barnett B, Buist A. A psychosocial risk assessment model (PRAM) for use with pregnant and postpartum women in primary care settings. Arch Womens Ment Health 2008;11:307–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cardone I, Kim J, Gordon T, Gordon S, Silver R. Psychosocial assessment by phone for high-scoring patients taking the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: Communication pathways and strategies. Arch Womens Ment Health 2006;9:87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feinberg E, Smith MV, Morales MJ, Claussen AH, Smith DC, Perou R. Improving women's health during internatal periods: Developing an evidenced-based approach to ddressing maternal depression in pediatric settings. J Womens Health 2006;15:692–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gjerdingen D, McGovern P, Center B. Problems with a diagnostic depression interview in a postpartum depression trial. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24:187–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olson A, Gaffney C. Parental depression screening for pediatric clinicians: An implementation manual. New York: The Commonwealth Fund, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stafford B. Health team works. Pregnancy-related depressive symptoms guidance. 2010. Available at: http://healthteamworks-mediaprecis5com/1cc3633c579a90cfdd895e64021e2163 (accessed October8, 2014)

- 57.Postpartum Support International. MedEd care pathways. Available at: http://wwwpostpartumnet/professionals/professional-tools/ (accessed June15, 2013)

- 58.Davis G. Multifaceted program helps pediatricians screen for maternal depression and asses infant crying and toilet training, enhancing their ability to prevent, identify, and address cases of potential child abuse. AHRQ; Available at: https://innovationsahrqgov/profiles/multifaceted-program-helps-pediatricians-screen-maternal-depression-and-assess-infant (accessed September8, 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rojas G, Fritsch R, Solis J, et al. Treatment of postnatal depression in low-income mothers in primary-care clinics in Santiago, Chile: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007;370:1629–1637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wiedmann M, Garfield C. Maternal depression and child development: strategies for primary care providers. IAFB/FPEN 2007:1–15 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Milgrom J, Holt CJ, Gemmill AW, et al. Treating postnatal depressive symptoms in primary care: A randomised controlled trial of GP management, with and without adjunctive counselling. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lumley J, Watson L, Small R, Brown S, Mitchell C, Gunn J. PRISM (Program of Resources, Information and Support for Mothers): A community-randomised trial to reduce depression and improve women's physical health six months after birth [ISRCTN03464021]. BMC Public Health 2006;6:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Austin MP, Priest SR, Sullivan EA. Antenatal psychosocial assessment for reducing perinatal mental health morbidity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008:CD005124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feinberg ME, Kan ML. Establishing family foundations: Intervention effects on coparenting, parent/infant well-being, and parent-child relations. J Fam Psychol 2008;22:253–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dennis C-L, Hodnett E, Kenton L, et al. Effect of peer support on prevention of postnatal depression among high risk women: Multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grote NK, Swartz HA, Geibel SL, Zuckoff A, Houck PR, Frank E. A randomized controlled trial of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Am Psychiatr Assoc 2009;60:313–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stuart S, O'Hara M, Gorman L. The prevention and psychotherapeutic treatment of postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health 2003;6:s57–s69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Swartz HA, Frank E, Zuckoff A, et al. Brief interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed mothers whose children are receiving psychiatric treatment. Am J Psychiatr 2008;165:1155–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pereira AT, Soares MJ, Bos S, et al. Why should we screen for perinatal depression? Ten reasons to do it. Int J Clin Neurosci Ment Health 2014; pp. 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Walker EA, Gelfand A, Katon WJ, et al. Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. Am J Med 1999;107:332–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boer PC, Wiersma D, Russo S. Paraprofessionals for anxiety and depressive disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dennis C-L, Ravitz P, Grigoriadis S, et al. The effect of telephone-based interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of postpartum depression: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2012;13:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Verdeli H, Clougherty K, Bolton P, et al. Adapting group interpersonal psychotherapy for a developing country: Experience in rural Uganda. World Psychiatry 2003;2:114–120 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weissman MM. Recent non-medication trials of interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2007;10:117–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grigoriadis S, Ravitz P. An approach to interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression Focusing on interpersonal changes. Can Fam Physician 2007;53:1469–1475 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Collins C, Hewson DL, Munger R, Wade T, McDonough JE, Foege WH. Evolving models of behavioral health: integration in primary care. News about Publications from the Milbank Memorial Fund; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Solberg LI, Crain AL, Jaeckels N, et al. The DIAMOND initiative: Implementing collaborative care for depression in 75 primary care clinics. Implement Sci 2013;8:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Feinstein L, Sabates R, Anderson TM, Sorhaindo A, Hammond C. The Effects of Education on Health: Concepts, evidence and policy implications. A review for the OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI). Paris: CERI, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Campbell AT, Mounts KO, McInerny TK. Legal and ethical considerations: Risks and benefits of postpartum depression screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics 2007;119:123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Horwitz SM, Caspary G, Storfer-Isser A, et al. Is developmental and behavioral pediatrics training related to perceived responsibility for treating mental health problems? Acad Pediatr 2010;10:252–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kerker BD, Storfer-Isser A, Szilagyi M, et al. Do pediatricians ask about adverse childhood experiences in pediatric primary care? [published online ahead of print October 31, 2015] Acad Pediatr 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Olson AL, Kemper KJ, Kelleher KJ, Hammond CS, Zuckerman BS, Dietrich AJ. Primary care pediatricians' roles and perceived responsibilities in the identification and management of maternal depression. Pediatrics 2002;110:1169–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wiley C, Burke G, Gill P, Law N. Pediatricians' views of postpartum depression: A self-administered survey. Arch Womens Ment Health 2004;7:231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Heneghan AM, Silver EJ, Bauman LJ, Stein RE. Do pediatricians recognize mothers with depressive symptoms? Pediatrics 2000;106:1367–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Abatemarco DJ, Kairys SW, Gubernick RS, et al. Expanding the pediatrician's black bag: A psychosocial care improvement model. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2008;34:106–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gillespie D. Screening tools and referral training for pediatric and primary care practices. AHRQ. 2014. Available at: http://www.postpartum.net/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=CW%2FnQRt%2BPh8%3D&tabid=593 (accessed September8, 2014)

- 87.Lovell JL, Roemer R, Talmi A. Pregnancy-related depression screening and services in pediatric primary care. A model program for addressing maternal depression in pediatric care. AAP Practicing Safety Project, May, 2014. http://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/newsletter/2014/05/pregnancy-depression.aspx (accessed October31, 2015)

- 88.Talmi A, Stafford B, Buchholz M. Providing perinatal mental health services in pediatric primary care. Washington, D.C.: Zero to Three, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Program of resources, information and support for mothers (PRISM) Model. 2015. Available at: http://www.latrobe.edu.au/jlc/research/maternity-care-and-family-services-in-the-early-years/prism/key-minimum-elements#eduprograms (accessed March30, 2015)

- 90.Health Team Works through APA. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Pregnancy-related depressive symptoms guidance. 2013. Available at: http://healthteamworks-media.precis5.com/5cbbf2ec6dfb4fde9a8467f0c00e1a42 (accessed June20, 2014)

- 91.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration monograph. 2008. Available at: http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/conditions/maternal-depression-making-difference-through-community-action-planning-guide (accessed March27, 2015) [PubMed]