Abstract

This work examines the potential of the predatory bacterium Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus HD100, an obligate predator of other Gram-negative bacteria, as an external cell-lytic agent for recovering valuable intracellular bio-products produced by prey cultures. The bio-product targets to be recovered were polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) produced naturally by Pseudomonas putida and Cupriavidus necator, or by recombinant Escherichia coli strains. B. bacteriovorus with a mutated PHA depolymerase gene to prevent the unwanted breakdown of the bio-product allowed the recovery of up to 80% of that accumulated by the prey bacteria, even at high biomass concentrations. This innovative downstream process highlights how B. bacteriovorus can be used as a novel, biological lytic agent for the inexpensive, industrial scale recovery of intracellular products from different Gram-negative prey cultures.

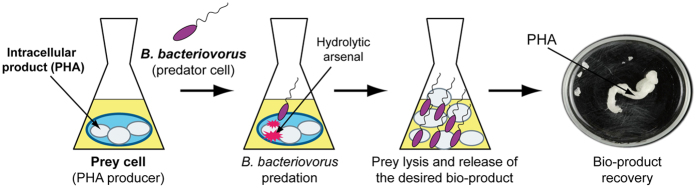

Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus is a small, highly motile, predatory bacterium that attacks other Gram-negative bacteria, invading their periplasm1,2. Once inside, the enzymatic degradation of prey constituents is initiated and the invader begins to grow, leading to the formation of a bdelloplast. The predator grows as a multinucleoid filament that finally septates to yield several progeny that escape the prey ghost to search for new prey cell (Fig. 1a–d). B. bacteriovorus was originally discovered in soil samples3 but has now been isolated from many environments, ranging from marine sediments to fresh water and even the guts of animals and humans4,5,6,7. This, together with an aptitude for preying on biofilms and multidrug-resistant pathogens, makes B. bacteriovorus a potential therapeutic agent for controlling human, animal and plant pathogens, the so-called “living antibiotic”2,8,9,10,11,12. In this work, we evaluated the potential use of a killer bacterium like B. bacteriovorus for biotechnological purposes. Given the predatory lifestyle of Bdellovibrio and its ability to lyse other bacteria, we investigated the feasibility for exploiting this predator as a novel downstream living lytic agent for the production of valuable intracellular bio-products (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Different growth stages of B. bacteriovorus HD100 preying on P. putida KT2440.

(a) TEM image of P. putida KT2440 accumulating mcl-PHA. (b) SEM image of a co-culture of B. bacteriovorus HD100 preying on P. putida KT2440. Different predator growth stages can be distinguished: Attack phase predator cells, entering the periplasm of the prey and growing in rounded prey cells (bdelloplast). (c) Detailed TEM image of predator cell development within a bdelloplast. (d) Detailed SEM image of prey cell lysis and release of predator progeny into the medium. (e) PHA granules released by B. bacteriovorus Bd3709 mutant after 24 h of predation upon P. putida KT2440.

Figure 2. Illustration of the lytic system procedure based on the use of B. bacteriovorus for intracellular bio-products recovery.

A culture of PHA-producing bacteria is prepared and infected with a suspension of B. bacteriovorus cells. After 24 h of predation the intracellular bio-product is released into the culture medium, facilitating the recovery.

At the industrial scale, one of the most challenging downstream production processes is the isolation of bacterial polyesters or polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs). These biodegradable polymers, which are produced by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, are attractive alternatives to petroleum-based plastics13. They accumulate as intracellular granules in the bacterial cytoplasm and can account for up to 90% of cell dry weight. Different short-chain-length-PHAs (scl-PHA) such as poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) based bioplastics are currently produced at large scale by several companies (reviewed by14) and have extensive applications in packaging, moulding, fibre production and other commodities. Medium-chain-length-PHAs (mcl-PHA, with carbon numbers ranging from 6 to 14) are promising candidates as bioplastics given their longer-side-chain-derived properties of reduced crystallinity, elasticity, hydrophobicity, low oxygen permeability and biodegradability. They can be moulded and processed to make compostable packaging or resorbable materials for use in medical applications, and are already in use as food coatings, pressure-sensitive adhesives, paint binders and biodegradable rubbers15,16,17. Unconventional mcl-PHAs bearing bespoke functional moieties in their side chains can be produced using different biotechnological strategies18,19. However, their condition as intracellular bio-products makes their recovery difficult and expensive20,21. In the last decades, great effort has been made for the isolation of these biopolymers, which is the key step of the process profitability in the fermentation system21. Mechanical cell disruption by high-pressure homogenization is one of the most popular methods, although separation processes such us filtration, froth flotation, continuous centrifugation, enzymatic digestion or use of detergents and solvents have been also investigated21. Some disadvantages related to these systems are the high cost of the process or the severe reduction in polymer molecular weight. Several attempts have been carried out to mimic such procedures by using phage lysis genes to disrupt recombinant cells accumulating PHA22,23,24,25,26. However, these systems are species-specific and require engineering of the production chassis26, which limit the broad range applicability of this methodology. Here we present a robust and generalizable downstream system based on the use of the predatory bacterium B. bacteriovorus as a cell lytic agent. In contrast to phage-based methods, Bdellovibrio exhibits the advantage of being able to prey upon a wide range of Gram-negative bacteria1,2, which opens new avenues for the production and recovery of interesting compounds.

It has recently been shown that B. bacteriovorus HD100 can prey upon PHA-producers such as Pseudomonas putida KT2440 while the latter accumutales large amounts of mcl-PHA within its cells27. After lysing the prey, the predator hydrolyses and consumes some, but not all, of the PHA released into the extracellular environment; indeed, significant quantities of PHA granules and of free hydroxyalkanoic acid (HAs) oligomers (54% and 25% respectively of PHA accumulated by the prey bacteria)27 can be recovered. It has been suggested that this hydrolysis is the result of an extracellular-like mcl-PHA depolymerase (PhaZBd), which forms part of B. bacteriovorus’s hydrolytic arsenal27,28,29. The potential of this predator as a downstream tool for intracellular bio-product recovery is shown in the present work by engineering B. bacteriovorus HD100 to avoid it degrading the prey-produced PHA. We show the ability of Bdellovibrio to attack high cell density prey cultures, allowing the release of the polymer. To further demonstrate the feasibility of the system, engineered Bdellovibrio strains were also tested against other species of Gram-negative bacteria that accumulate these biopolymers. The results provide proof-of-principle that this system could be used in the production of PHA and other intracellular bio-products.

Results

Engineering B. bacteriovorus HD100 to prevent PHA hydrolysis during the predation of P. putida KT2440

B. bacteriovorus HD100 preying on PHA-accumulating P. putida cultures caused the release of part of the PHA granules and hydrolysis products (HAs, meaning a mixture of monomers and oligomers) into the culture medium (Table 1)27. To avoid the degradation of the prey-produced PHA by the attacking B. bacteriovorus cells, a phaZBd depolymerase mutant strain - B. bacteriovorus Bd3709 - was produced by disrupting phaZBd via the insertion of a kanamycin resistance gene (see Methods for details). After 24 h of predation, mutant B. bacteriovorus Bd3709 lysed the prey cells efficiently, resulting in a 2-logs increase in the predator cell number (Table 1). The B. bacteriovorus Bd3709/P. putida KT2440 co-culture showed PHA content similar to that of the control culture (P. putida without B. bacteriovorus) after 24 h of incubation [0.85 g l−1 (80% of the initial PHA produced by the P. putida KT2440 cells)] (Table 1). However, in B. bacteriovorus HD100/P. putida KT2440 co-cultures only 60% of the PHA content was recovered (Table 1). Figure 1e shows the remains of a P. putida KT2440 cell containing PHA after a being preyed by B. bacteriovorus Bd3709 mutant. Remarkably, PHA granules were visible in the extracellular medium together with the predator, while no integer prey cells were appreciable. A film showing B. bacteriovorus Bd3709 cells swimming around the released PHA granules can be seen in the Supplementary Material (Movie 2).

Table 1. Growth and PHA content at time zero and 24 h of co-cultures involving B. bacteriovorus HD100 or the Bd3709 mutant preying on PHA-accumulating P. putida KT2440.

| Strain culturesa | Prey biomass 0 h (g l−1) | Prey PHA content 0 h (g l−1) | PHA content in the bacterial sediment 24 h (g l−1) | PHA hydrolysis product contents in medium 24 h (g l−1) | Prey cell count 24 h (105 cfu ml−1) | Predator cell count 24 h (108 pfu ml−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KT2440b | 1.92 ± 0.08 | 1.07 ± 0.11 | 0.87 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.090 | 1270 ± 423 | – |

| HD100/KT2440 | 1.92 ± 0.08 | 1.07 ± 0.11 | 0.65 ± 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.070 | 1.05 ± 0.84 | 26.20 ± 2.62 |

| Bd3709/KT2440 | 1.92 ± 0.08 | 1.07 ± 0.11 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 0.24 ± 0.020 | 0.09 ± 0.1 | 15.20 ± 4.11 |

aViable prey cell numbers at time zero of predation: (9.5 ± 2.4) · 107 cfu ml−1. Viable B. bacteriovorus HD100 cell numbers at time zero of predation: (8.3 ± 3.7) · 107 pfu ml−1. Viable B. bacteriovorus Bd3709 cell number at time zero of predation: (4.4 ± 2.3) · 107 pfu ml−1.

bControl prey cultures (i.e., with no predatory bacteria).

B. bacteriovorus HD100 released larger amounts of HAs into the extracellular medium than the Bd3709 strain, showing that phaZBd disruption avoided PHA degradation during predation (Table 1). Indeed, with the Bd3709 mutant, nearly all the PHA granules accumulated by the prey were recovered after the predatory event. It is worth mentioning that B. bacteriovorus HD100 did not produce PHA, at least in the conditions assayed (see Methods for details).

B. bacteriovorus HD100 can prey on high cell densities of P. putida KT2440 accumulating PHA

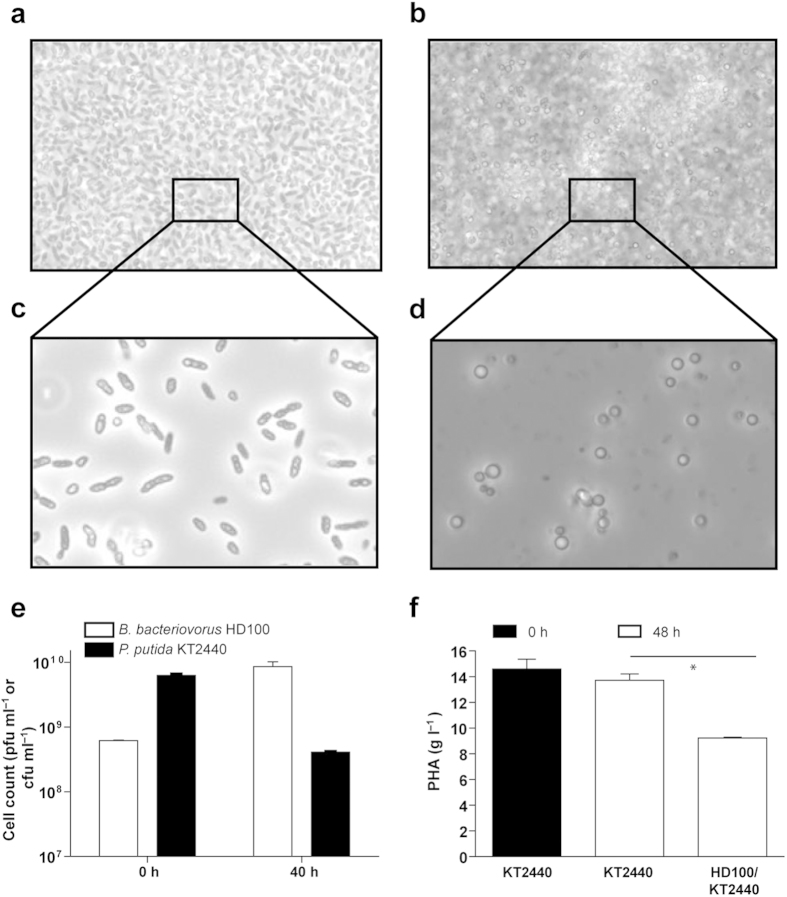

A requirement for the industrial scale use of B. bacteriovorus as a living, cell-lytic system would be the ability of the predator to attack high cell density prey cultures. Therefore, the potential of B. bacteriovorus HD100 to prey on high cell density cultures of P. putida KT2440 accumulating PHA was tested. For this, prey cultures were prepared in Hepes buffer with a cell biomass of 30.5 g l−1 (biomass production by PHA-producing pseudomonads under optimal conditions ranges between 15–55 g l−1)30, corresponding to 8.3 ± 0.3 · 109 colony-forming units [(cfu) ml−1], with a PHA content of 15.1 g l−1 (Fig. 3a,c). These cultures were then inoculated with 6.3 ± 0.3 · 108 plaque-forming units (pfu) ml−1 of B. bacteriovorus HD100. After 40 h of predation, a 1-log reduction in prey cells was observed while an increase of 1-log in the viable cell number of B. bacteriovorus was measured (Fig. 3e). This confirms the predator’s ability to prey on high-density cultures of PHA-accumulating P. putida KT2440. Examination of the co-cultures by phase-contrast microscopy clearly revealed the release of PHA granules into the extracellular medium (Fig. 3b,d). Although optimization of PHA recovery is required at this cell density scale, 65% of the PHA accumulated by the prey bacteria was recovered under our lab scale conditions (Fig. 3f). Notably, the polymer was directly extractable from the wet biomass of the co-cultures.

Figure 3. B. bacteriovorus HD100 preying on high cell densities of P. putida KT2440 accumulating mcl-PHA.

(a) Phase-contrast microscopy of a co-culture of B. bacteriovorus HD100 preying on P. putida KT2440 at the onset of predation (time zero) and (b) after 40 h of incubation. (c,d) 1:100 dilution of the co-cultures from panels (a,b), respectively. Mcl-PHA granules can be observed in the extracellular medium after 40 h of predation. (e) Cell viability assay of the co-culture of B. bacteriovorus HD100/P. putida KT2440 (white bars and black bars, respectively) at the onset of predation (time zero) and within 40 h. (f) Total PHA content in the co-culture of B. bacteriovorus HD100/P. putida KT2440 compared to the control culture (KT2440 without the predator) at the onset of predation (time zero) (white bars) and within 40 h (black bars). Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences (*P < 0.05).

Molecular characterization of the PHA recovered from predator/prey co-cultures

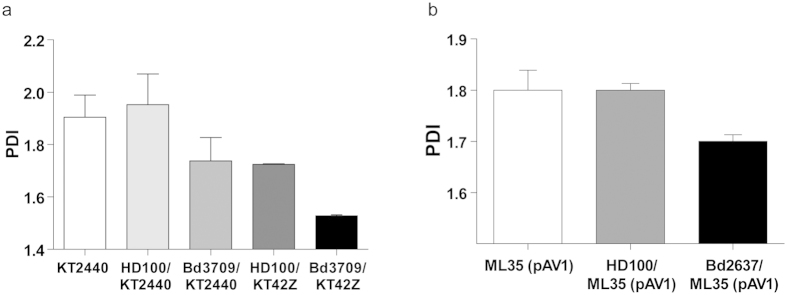

The PHA recovered from the B. bacteriovorus Bd3709/P. putida KT2440 co-culture was compared to that recovered from the B. bacteriovorus HD100/P. putida KT2440 co-culture and that from the P. putida KT2440 culture (as control experiment, extracted by subjecting the cells to lysis using a French press). The PHA extracted from B. bacteriovorus Bd3709/P. putida KT2440 co-culture showed a profile with a higher weight-average molecular weight (Mw) and number-average molecular weight (Mn), and a lower polydispersity index (PDI) than the PHA recovered from the B. bacteriovorus HD100/P. putida KT2440 co-culture (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 2). This indicates that, in the latter co-culture the biopolymer was partially degraded, increasing the heterogeneity of the polymer chains in terms of their molecular mass.

Figure 4. Molecular characterization of PHA and PHB polymers obtained from 24 h co-cultures with B. bacteriovorus strains.

(a) Polydispersity index (PDI) values of the PHA obtained from the co-cultures of B. bacteriovorus HD100 and Bd3709 strains preying on PHA-accumulating P. putida KT2440 or KT42Z. (b) PDI values of the PHB obtained from B. bacteriovorus HD100 and Bd2637 strains preying on PHB-accumulating E. coli ML35 (pAV1). Polymer granules were directly isolated from the co-cultures sediments with chloroform (PHA) or dichloromethane (PHB). As an experimental control, the polymer was extracted from the prey culture (without predator) by breaking the cells with a French press. The results of one experiment are shown; the values were reproducible in three separate experiments with standard deviations of <10%. Error bars mean the variation of three technical replicates.

It is well documented that P. putida KT2440 possesses an intracellular mcl-PHA depolymerase (PhaZKT) that plays a key role in PHA turnover31,32. PhaZKT degrades PHA and releases 3-hydroxycarboxylic acid monomers, which can either be oxidized via the β-oxidation pathway to generate energy, or be incorporated into nascent PHA polymer chains by PHA synthase, depending on the metabolic state of the cell32. To analyse the putative activity of PhaZKT depolymerase during the predatory event, the PDI of the polymer recovered from the co-cultures of B. bacteriovorus HD100 and Bd3709 preying on P. putida KT42Z (which lacks the PhaZKT depolymerase) was also quantified and characterized (Fig. 4a). As expected, the PHA extracted from the B. bacteriovorus Bd3709/P. putida KT42Z co-culture showed lower PDI than the PHA recovered from the B. bacteriovorus HD100/P. putida KT42Z co-culture, highlighting the extracellular-like depolymerase of B. bacteriovorus as the responsible for the partial degradation of the mcl-PHA during predation.

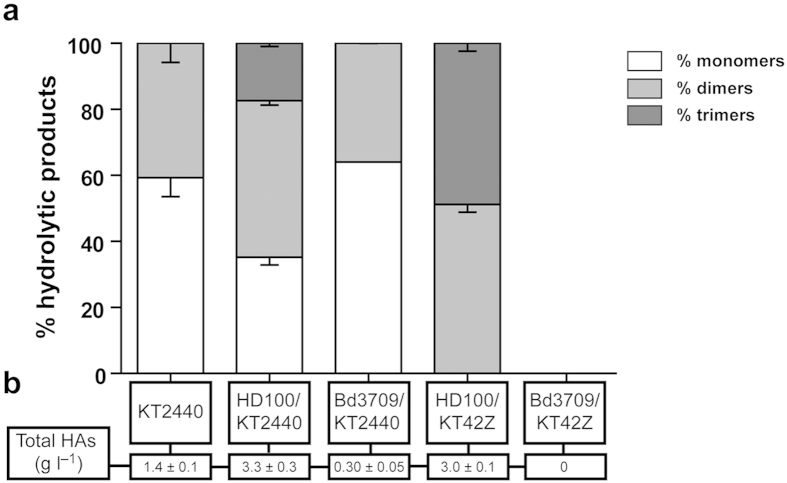

Analysis of the mcl-PHA hydrolytic products recovered by B. bacteriovorus Bd3709

According to the above results, the profile of the HAs products should differ depending on the predatory strain used in the co-culture. To examine this, P. putida KT2440 cells were prepared in Hepes buffer at a biomass of 5.7 g l−1 (corresponding to 2.4 ± 0.2 · 107 cfu ml−1 with a PHA content of 2.4 g l−1), and subsequently inoculated with 5.3 ± 0.3 · 107 B. bacteriovorus HD100 or 3.7 ± 0.1 · 107 pfu ml−1 B. bacteriovorus Bd3709. After 30 h of predation, the extracellular medium was analysed by HPLC-MS. The mcl-PHA hydrolytic product profile for the B. bacteriovorus Bd3709/P. putida KT2440 co-culture - mainly monomers and dimers - was similar to that recorded for P. putida KT2440 growing alone (Fig. 5). However, it differed strongly to that of the B. bacteriovorus HD100/P. putida KT2440 co-cultures, which showed larger proportions of dimers and trimers, similar to that obtained in in vitro experiments using pure PhaZBd depolymerase29. These differences could be attributed to the different activities of the depolymerases produced by P. putida KT2440 (PhaZKT, intracellular) and B. bacteriovorus (PhaZBd, extracellular-like) (see below).

Figure 5. Mcl-PHA hydrolytic product profile identified in the co-culture supernatants of B. bacteriovorus strains preying on P. putida KT2440 and KT42Z accumulating mcl-PHA.

(a) HPLC-MS analysis after 30 h of predation by Bdellovibrio strains. Monomers (white bars), dimers (light grey bars) and trimers (dark grey bars). Control supernatants of P. putida KT2440 and KT42Z are also shown. (b) Total PHA hydrolysis products quantified in the culture supernatants. No significant differences were observed between: (i) the percentage of monomers of the PHA extracted from KT2440 and Bd3709/KT2440, (ii) the percentage of dimers of KT2440 and HD100/KT2440, (iii) the percentage of dimers of KT2440 and Bd3709/KT2440, and (iv) the percentage of dimers of KT2440 and dimers of Bd3709/KT42Z. The rest of the conditions showed significant differences (P < 0.05) determined by ANOVA-test.

The total PHA hydrolysis products released to the extracellular medium following predation was quantified by HPLC-MS (Fig. 5). Values of 3.3 ± 0.33 and 0.30 ± 0.05 g l−1 were recorded for the B. bacteriovorus HD100/P. putida KT2440 and B. bacteriovorus Bd3709/P. putida KT2440 co-cultures, respectively (Fig. 5b). To further confirm that PhaZBd degrades PHA during predation, the PHA hydrolytic product profile was also examined for the co-cultures of B. bacteriovorus HD100 or Bd3709 preying on P. putida KT42Z (Fig. 5). As expected, no HAs were found in the B. bacteriovorus Bd3709/P. putida KT42Z co-culture, while the hydrolytic product profile of the B. bacteriovorus HD100/P. putida KT42Z co-culture showed (mainly) dimers and trimers (Fig. 5).

Expanding the B. bacteriovorus toolbox to other microorganisms

Since B. bacteriovorus HD100 attacks a broad range of Gram-negative bacteria1,2, the feasibility of using this lytic tool in other production systems was tested. As a proof-of-concept, the recovery of other PHAs such as polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), consisting of C4–C5 monomers and with different properties and applications33, was studied. E. coli ML35 (pAV1) expressing the three main proteins for PHB synthesis in Cupriavidus necator H16 (PhaC1, PhaA and PhaB1), was used as a prey bacterium. These cells were prepared in Hepes buffer at 5.25 g l−1 (corresponding to 2.2 · 109 cfu ml−1 and 1.3 g l−1 PHB), and inoculated with 1.45 · 107 pfu ml−1 of B. bacteriovorus HD100 for 24 h (Table 2). After 24 h of predation by B. bacteriovorus HD100 PHA content decreased by more than 50% of that previously accumulated by the prey, suggesting that the predator hydrolysed the PHB. In this case, the PHB hydrolysis observed cannot be ascribed to any hydrolytic activity of the prey, since E. coli strains are unable to degrade PHB due to the lack of the necessary depolymerases.

Table 2. Growth and PHB content at time zero and 24 h of co-cultures involving B. bacteriovorus HD100 or the Bd3709 mutant preying on PHB-accumulating E. coli ML35 (pAV1).

| Strain culturesa | Prey biomass 0 h (g l−1) | Prey PHB content 0 h (g l−1) | PHB content in the bacterial sediment 24 h (g l−1) | Prey cell count 24 h (107cfu ml−1) | Predator cell count 24 h (109 pfu ml−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML35 (pAV1)b | 5.25 ± 0.13 | 1.3 ± 0.33 | 1.30 ± 0.22 | 283 ± 61 | – |

| HD100/ML35 (pAV1) | 5.25 ± 0.13 | 1.3 ± 0.33 | 0.63 ± 0.12 | 1.75 ± 0.645 | 13.2 ± 6.2 |

| Bd2637/ML35 (pAV1) | 5.25 ± 0.13 | 1.3 ± 0.33 | 0.83 ± 0.25 | 0.54 ± 0.51 | 16.1 ± 2.8 |

aViable prey cell numbers at time zero of predation: (2.2 ± 4.0) · 109 cfu ml−1. Viable B. bacteriovorus HD100 cell numbers at time zero of predation: (1.45 ± 3.4) · 107 pfu ml−1. Viable B. bacteriovorus Bd3709 cell number at time zero of predation: (1.6 ± 3.3)·107 pfu ml−1.

bControl prey cultures (without predator cells).

To investigate the effect of PHB degradation on the fitness of B. bacteriovorus, the wild-type strain E. coli ML35 (pACYC184) and the PHB-producing strain E. coli ML35 (pAV1), were cultured under PHB production growth conditions. Prey cultures were adjusted to equal residual (i.e., a PHB-free) biomass (0.3 ± 0.05 g l−1), and then inoculated with 1.9 ± 0.108 pfu ml−1 of B. bacteriovorus HD100. After 24 h of predation, the predator population was 10-fold higher when preying on PHB-accumulating E. coli cells than on the wild-type E. coli cells unable to produce PHB (Supplementary Fig. 1). This suggests a benefit for B. bacteriovorus in terms of biomass yield when preying on bacteria containing an extra carbon source in the form of PHB. This differs to that reported with P. putida; when preying on this bacterium, the number of progeny is independent of the presence of mcl-PHA27.

A potential extracellular scl-PHA depolymerase coding sequence is found in the genome of B. bacteriovorus HD100 [open reading frame (ORF) Bd2637], adding to its hydrolytic arsenal27,28,34. This putative scl-PHA depolymerase might be responsible for the degradation of the prey’s PHB during the predatory cycle. Therefore, B. bacteriovorus was engineered to avoid PHB degradation via an in-frame deletion of ORF Bd2637. This was achieved by inserting the suicide vector pK18mobsacB-2637 into B. bacteriovorus HD100 via conjugation and homologous recombination, with subsequent sucrose suicide screening for gene replacement. After 24 h of predation upon E. coli ML35 (pAV1), B. bacteriovorus Bd2637 knockout caused the release of larger amounts of PHB than did B. bacteriovorus HD100 (64% and 48%, respectively) (Table 2). This shows that ORF Bd2637 codes for a genuine scl-PHA depolymerase and confirms B. bacteriovorus Bd2637 mutant can be used as an improved lytic agent in the PHB production process. These results demonstrate the potential of B. bacteriovorus as a tailored tool for use in the harvesting of prey intracellular products.

Predation in high-density PHB-producing E. coli ML35 (pAV1) cultures was also monitored. At the start of the experiment, host viability, cell biomass and PHB content were 2.6 · 109 cfu ml−1, 55 g l−1 and 19 g l−1, respectively. After 48 h of predation, both the wild-type and mutant B. bacteriovorus strains lysed the prey cells efficiently, achieving 4-log reductions in prey cells.

The molecular characterization of the PHB recovered from the co-cultures of the wild-type and mutant B. bacteriovorus strains preying upon E. coli ML35 (pAV1) showed extremely high Mw, as described by reference35, ranging from 3 × 106 to 1 × 106, with relatively low PDI of around 1.8–1.7 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 2). The PDI remained nearly unchanged during the predation event, independently of the predatory strain applied in the process. These results indicated that the impact of the functionality of the scl-PHA depolymerase in the molecular weight and PDI of the polymer is not significant in our assay conditions. This differs to the results obtained for P. putida (see above).

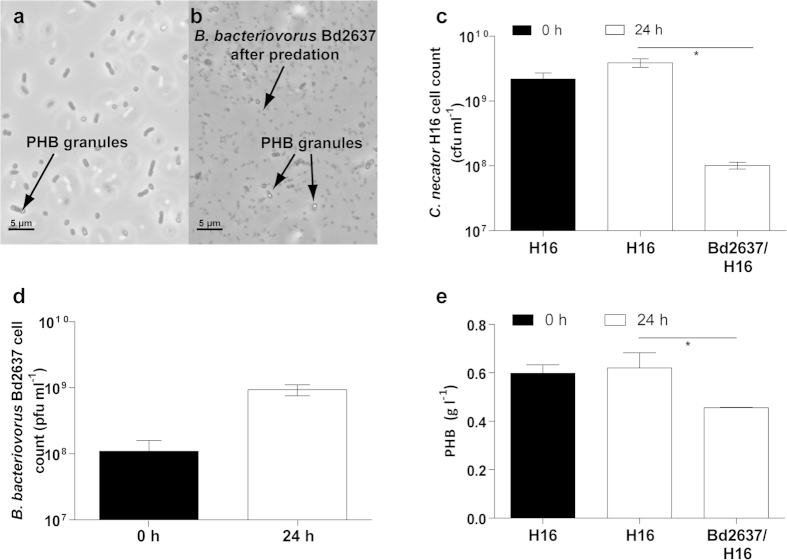

Finally, other model PHB producer like C. necator H16 was grown under PHB production conditions and infected with B. bacteriovorus Bd2637. C. necator H16 (Fig. 6) felt prey to the predator demonstrating the versatility of this lytic system. Specifically, predation upon C. necator H16 let to an increase of 1-log in the viable cell number of B. bacteriovorus (Fig. 6d) and the recovery of 80% of the prey’s PHB after 24 h of predation (Fig. 6e). These results demonstrated the predator’s capability to prey upon other natural PHB producing bacteria, although scaling up would request to optimize the conditions of PHB production and recovery for each particular process.

Figure 6. B. bacteriovorus Bd2637 preying on C. necator H16 accumulating PHB.

(a) Phase-contrast microscopy of the co-culture at the onset of predation (time zero) and (b) after 24 h of incubation with B. bacteriovorus. (c) Number of viable cells of C. necator H16 accumulating PHB at time zero and after 24 h of predation without and with B. bacteriovorus Bd2637. (d) Number of viable cells of B. bacteriovorus Bd2637 at time zero and after 24 h of predation upon C. necator H16 accumulating PHB. (e) Total PHB content in the co-cultures. In all graphs, error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean (n = 3). Asterisk indicate significant differences (*P ≤ 0.05) between control prey culture (i.e., without the predator) and B. bacteriovorus Bd2637 co-cultures, as determined by ANOVA-test.

Discussion

The obligate predator B. bacteriovorus has long been proposed as an alternative for antibiotics, given its ability to attack Gram-negative bacteria2,8,9,10,11,12. The genome sequence of B. bacteriovorus HD10028 suggested that the vast amount of hydrolytic enzymes (biocatalysts) might be suitable for numerous industrial applications27,28,29. In this context, we highlight B. bacteriovorus as an innovative cell lytic agent for intracellular bio-products recovery. The system described in the present work consists of adding a predator culture to a culture of PHA-producing prey bacteria, leading to the release of this intracellular biopolymer into the culture medium. Using a B. bacteriovorus PhaZBd depolymerase mutant (B. bacteriovorus Bd3709) to prevent the breakdown of the target product, more than 80% of the PHA accumulated in the prey cells was recovered from the extracellular medium. This system avoids the costly step of breaking the cells and drying the prey biomass – the conventional method of harvesting the PHA. Unlike B. bacteriovorus HD100, the Bd3709 mutant did not degrade the prey-produced mcl-PHA during predation, allowing the recovery of more homogeneous samples with lower PDI, a key requirement in polymer processing21.

In contrast to phage specificity, B. bacteriovorus attacks a wide range of Gram-negative bacteria1,2. Therefore, the cell lysis procedure was also successfully used in other prey species for the harvesting of PHB as C. necator H16. The system progressed successfully in the model strain C. necator H16 (Fig. 6). However, it is well known that during their cell cycle, some PHB producers might degrade the intracellularly accumulated PHB by the action of their native depolymerases36. This would make necessary to rational development of the phenotype of the producer prey or to engineer a more amenable heterologous chassis organism. The latter was attempted by expressing the PHB synthesis cluster from C. necator H16 in E. coli ML35 (E. coli is among the organisms most tractable to biological engineering37). Using this as the prey for B. bacteriovorus Bd2637 mutant (the HD100 knockout for the putative PHB depolymerase29,34), allowed the recovery of larger amounts of extremely high Mw (3–1 × 106) PHB after 24 h of predation. However, this mutant still degraded some of the prey’s PHB. Indeed, B. bacteriovorus is known to have many hydrolases in its hydrolytic arsenal28, some of which might have degraded the PHB.

Unexpectedly, both B. bacteriovorus Bd3709 and Bd2637 killed more prey cells than did wild-type B. bacteriovorus HD100. Additional experiments are needed to determine whether mcl-PHA and scl-PHA depolymerase deletion improves the fitness and predation capacity of Bdellovibrio.

Previous studies of B. bacteriovorus HD100 preying upon P. putida showed that PHA degradation confers ecological advantages upon the former in terms of motility and predation efficiency, very likely due to an increment of the intracellular ATP content, but does not increase the biomass or number of predator cells27. In contrast, preying on PHB-accumulating E. coli cells did seem to afford the predator fitness benefits in terms of number of progeny, although the mean swimming speed was similar. The monomers and hydrolysis products derived from PHB degradation might be catabolised for biomass generation via a putative R-3-hydroxyacyl CoA synthase (Bd1803) [EC 6.2.1.3 (http://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?bba00071)], followed by the action of a putative 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA isomerase to yield S-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA (Bd1836) [EC 5.1.2.3 (http://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?bba00650)]. Finally, 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase would convert S-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA into acetoacetyl-CoA (Bd1836) [EC 1.1.1.35 (http://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?bba00650)], which channels into central metabolism, thus explaining the increase in predator progeny after preying on PHB-accumulating E. coli. It has also been described that B. bacteriovorus uses intermediate metabolites it takes from the prey38,39; PHA and PHB may therefore have behaved as extra carbon sources. These metabolites might become incorporated into the fatty acid pathway and secondary metabolism, improving the predation capacity of the bacterium.

Although the examined system needs to be tested at larger scales in a pilot plant, it showed good performance at high biomass concentrations, suggesting industrial-scale upgrade is possible. This is worth investigating since it would provide a means of harvesting intracellular bio-products such as PHA in a single step, avoiding cell breakage and dry biomass treatments, and using reduced amounts of organic solvents. Not only would this be cheaper, it would have environmental benefits. More powerful predators also need to be developed, as do systems that can guarantee their long-term storage without loss of their predatory capacity. This opens new challenges to be addressed by synthetic biology strategies.

In summary, this study highlights the potential use of bacterial predators as external, living, cell-lytic agents of Gram-negative bacteria, causing the release into the extracellular medium of compounds previously made by the latter. The industrial-scale recovery of PHAs from bacterial cells is currently difficult and expensive. Solving this problem would unlock the economics of PHA production. The present work proposes an innovative downstream procedure that could make the production of bioplastics much profitable. This could have enormous environmental, economic and social benefits.

Methods

Bacterial strains, media and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are described in Supplementary Table 1. Unless otherwise stated, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas putida and Cupriavidus necator strains were grown in nutrient broth (NB) (Difco) or in lysogeny broth (LB)40 at 37 °C (E. coli) or 30 °C (P. putida and C. necator) with shaking. Chloramphenicol (Cm) (30 μg ml−1) and kanamycin (Km) (50 μg ml−1) were added when needed. Growth was monitored using a Shimadzu UV-260 spectrophotometer at 600 nm (OD600). Solid media were made with 1.5% (w/v) agar. For PHB production, E. coli ML35 (pAV1) was grown in LB broth with 1% glucose, at 20 °C for 40 h; C. necator was grown in a nitrogen-limited minimal medium modified from reference41 (0.33 g KH2PO4 l−1, 1.2 g Na2HPO4 l−1, 0.11 g NH4Cl l−1) for 24 h, supplemented with 3.25 mM MgSO4, a solution of trace elements (composition 1000 × 2.78 g FeSO4·7H2O l−1, 1.98 g MnCl2·4H2O l−1, 2.81 g CoSO4·7H2O l−1, 1.47 g CaCl2·2H2O l−1, 0.17 g CuCl2·2H2O l−1, 0.29 g ZnSO4·7H2O l−1) and fructose (55.5 mM) as the sole carbon source. For mcl-PHA production, P. putida strains were grown in 0.1 N M63, a nitrogen-limited minimal medium (13.6 g KH2PO4 l−1, 0.2 g (NH4)2SO4 l−1, 0.5 mg FeSO4·7H2O l−1, adjusted to pH 7.0 with KOH). This medium was supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4 and a solution of trace elements (composition 1000 × 2.78 g FeSO4·7H2O l−1, 1.98 g MnCl2·4H2O l−1, 2.81 g CoSO4·7H2O l−1, 1.47 g CaCl2·2H2O l−1, 0.17 g CuCl2·2H2O l−1, 0.29 g ZnSO4·7H2O l−1). Sodium octanoate (15 mM) was used as the sole carbon source, as previously described27,42. B. bacteriovorus HD100 was routinely grown in co-culture in Hepes buffer (25 mM Hepes amended with 2 mM CaCl2·2H2O and 3 mM MgCl2·3H2O, pH 7.8) or DNB liquid medium (consisting of 0.8 g l−1 NB supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2 and 3 mM MgCl2), with P. putida KT2440 as prey27. Prey cultures were prepared from cells grown in NB for 16 h, and diluted to OD600 1 in Hepes buffer. After predation, the co-cultures were filtered twice through a 0.45 μm filter (Sartorius) and the B. bacteriovorus cells used in the assays below. All co-cultures were grown in 100 ml flasks in a final volume of 10 ml.

DNA manipulations

DNA manipulations and other standard molecular biology techniques were essentially performed as previously described40. PCR amplifications were performed in the buffer recommended by the manufacturer plus 0.05 μg of template DNA, 2 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase and 0.5 μg of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate. Conditions for amplification were chosen according to the GC content of the oligonucleotides used. DNA fragments were purified by standard procedures using the Gene Clean Turbo Kit (MP Biomedicals). Genomic DNA was isolated with the Bacteria genomicPrep Mini Spin Kit (GE Healthcare). PCR products were purified using the High Pure Plasmid Isolation Kit (Roche Applied Science).

Construction of B. bacteriovorus HD100 mutants

B. bacteriovorus Bd3709 (genotype Bd3709::pK18mob-3709) was constructed via the disruption of the phaZBd gene (ORF Bd3709). This involved the insertion of the whole pK18mob-3709 plasmid (Supplementary Table 1) into the chromosome of the predator by conjugation and homologous recombination. The plasmid pK18mob-3709 carries a truncated version of the phaZBd gene and its integration confers kanamycin resistance. The plasmid was constructed using the oligonucleotides PHO-F and PHO-R (Supplementary Table 1) with the B. bacteriovorus HD100 genome as a template. A 582 bp fragment of phaZBd was produced by introducing an artificial stop codon to interrupt the translation of the gene in the resulting B. bacteriovorus Bd3709 mutant. This fragment was digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes and ligated using T4 DNA ligase, resulting in the desired mutant version of the gene. This was cloned into the corresponding HindIII and XbaI sites of the pK18mob plasmid to yield pK18mob-3709 (Supplementary Table 1) (the DNA sequence of the resultant plasmid was confirmed). This was then used to deliver the mutation to the host chromosome of B. bacteriovorus HD100. Biparental mating was performed using E. coli S17-λpir as the donor strain and B. bacteriovorus HD100 as the recipient (Supplementary Table 1). For conjugation, 12 ml of the overnight culture of the donor strain, suspended in 100 μl of DNB, and 50 ml of B. bacteriovorus HD100/P. putida KT2440 co-culture filtered, pelleted and suspended in 100 μl of DNB, were collected on a Millipore filter, which was then placed on a DNB agar plate and incubated for 30 h at 30 °C. After incubation, the cells were suspended in 2 ml of DNB medium and plated on DNB plus kanamycin using the double-agar-overlay method27,43, with a kanamycin-resistant P. putida strain (from our laboratory collection) as the prey. Kanamycin-resistant conjugants were isolated from the double-layer agar plates and the insertion checked by PCR. To check the insertion stability, 10 consecutive passes from plate to plate containing DNB plus kanamycin were performed, and the insertion confirmed by PCR analysis of 20 mutant B. bacteriovorus plaques.

B. bacteriovorus Bd2637 (genotype ΔBd2637) was constructed as follows. The bd2637 gene coding for a putative scl-PHA depolymerase29,34 was inactivated by allelic exchange homologous recombination using the mobilizable suicide plasmid pK18mobsacB44. The deletion of ORF Bd2637 was engineered using the DNA fragments PHBA and PHBB (745 bp and 776 bp long respectively) generated by PCR using the primer pairs PHB-F and PHB-IR for PHBA, and PHB-IF and PHB-R for PHBB (Supplementary Table 1). These two fragments were digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes, ligated using T4 DNA ligase and cloned into the corresponding HindIII and XbaI sites of pK18mobsacB to yield pK18mobsacB-2637 (Supplementary Table 1). The resultant plasmid was confirmed by DNA sequencing and used to deliver the mutation to the host chromosome of B. bacteriovorus HD100 via homologous recombination. Biparental mating was performed for 30 h with E. coli S17-λpir as the donor strain as described above. The strains resulting from the first recombination event were screened for the insertion of the knockout construct via PCR. Merodiploid clones were plated twice onto double-layer agar plates with a kanamycin-resistant P. putida strain as prey. Thereafter, the merodiploids were transferred onto double-layer agar plates containing 5% sucrose in the bottom layer, plus an additional 5% sucrose and P. putida cells in the top layer. The resulting turbid plaques were isolated and the second cross-over event confirmed by PCR, leaving the resultant mutant strain B. bacteriovorus Bd2637 with bd2637 deleted (Supplementary Table 1).

Predatory capability of B. bacteriovorus HD100 and mutant strains

B. bacteriovorus and prey strain viabilities in co-culture were calculated. Serial dilutions of the co-culture from 10−1 to 10−7 were made in DNB liquid medium. To calculate B. bacteriovorus viability, 0.1 ml of the appropriate dilution was mixed with additional 0.5 ml of prey cell suspension of P. putida KT2440 pre-grown in NB and prepared in Hepes buffer at OD600 10, vortexed, and plated on DNB solid medium using the double-agar-overlay method. Predators were counted as pfu (plaque-forming units) developing on the lawn of P. putida KT2440 after 48 h of incubation at 30 °C. To calculate the viability of the prey strain, 10 μl of each dilution were placed on LB solid medium and the number of cfu (colony-forming units) counted. Experiments were performed in triplicate for each strain.

To test the predation capacity of the predator on prey cells containing PHA, P. putida and E. coli strains were grown under PHA production conditions, centrifuged, suspended in Hepes buffer (at different cell densities), and these cultured and inoculated with B. bacteriovorus strains (107–109 pfu ml−1). Interactions were left to proceed for 24–48 h. For predation experiments involving C. necator H16, the prey cultures were prepared in Hepes buffer (OD600 1) and inoculated with 107 pfu ml−1 of B. bacteriovorus HD100 for 24 h. To normalize the predation, results obtained with PHB-accumulating prey cells against those obtained with non-accumulating cells, E. coli ML35 (pACYC184) and E. coli ML35 (pAV1) prey suspensions were adjusted to have equal residual biomass (0.3 ± 0.05 g l−1) (i.e., the cell biomass after subtracting the mass of PHA) in Hepes buffer. These cultures were then exposed to 108 pfu ml−1 of B. bacteriovorus strains for 24 h.

Biomass calculation

Cell densities, expressed in grams of cell dry weight (CDW) per litre, were determined gravimetrically as previously reported26. Briefly, 10 ml of culture medium were centrifuged for 20 min at 14,000 g and 4 °C. The cell pellets and supernatants were lyophilised for 24 h and weighed. The residual biomass (total biomass minus the PHB biomass) of these cells was used in analyses of the capacity of B. bacteriovorus strains to prey on PHB-producing E. coli ML35 (pAV1).

GC-MS analysis of PHA content

For total PHA quantification, cultures were harvested, lyophilized and analysed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) as previously reported26,31. For PHA quantification in B. bacteriovorus HD100 cells, 50 ml of a co-culture with P. putida KT2440 were filtered twice, lyophilized and analysed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.

HPLC-MS analysis for the identification of PHA hydrolysis products

To identify degradation products, co-culture extracellular medium was analysed by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) as previously reported27,29. Briefly, the prepared extracellular medium was suspended in methanol at 3 mg/ml, and 25 μl injected into the chromatographic system. The separation of the hydrolysis products was performed using a Finnigan Surveyor pump coupled to a Finnigan LXQ TM ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron).

PHA isolation and molecular characterization

10 ml of the co-cultures of B. bacteriovorus strains preying on P. putida KT2440 or E. coli ML35 (pAV1) accumulating PHA or PHB were centrifuged and the resulting sediments (wet biomass) suspended in 5 ml of chloroform or dichlorometane, respectively. The solvent phase was collected and precipitated by adding 10 volumes of methanol. Finally, the polymer was dried under vacuum for 10 min and analysed by GC-MS to determine the polymer content and purity. As a control, 10 ml of PHA-accumulating P. putida KT2440 or PHB accumulating E. coli ML35 (pAV1) cultures (without the predator bacterium) were harvested, suspended in salt solution, and disrupted twice by passing through a French pressure cell at 69 bars.

The weight-average molecular weight (Mw), number-average molecular weight (Mn) and polydispersity index (PDI) of the mcl-PHA were determined by size exclusion chromatography in a Perkin-Elmer instrument equipped with a series 200 isocratic pump connected to a differential refractometric detector (series 200a). Two Styragel columns (HR5E, 5 μm, 7.8 mm × 300 mm) (Waters) were conditioned at 70 °C and used to elute the samples (2 mg ml−1 concentration) at 0.7 ml min−1. HPLC grade N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) supplemented with 0.1% v/v LiBr was used as the mobile phase. The calibration curve was constructed using polystyrene standards (Polymer Laboratories) from 580 to 1.6 · 106 g mol−1. The sample injection volume was 100 μl. For PHB molecular characterization (Mw, Mn and PDI), the samples were analysed by employing gel permeation chromatography (GPC) coupled with a Waters HPLC 1512 equipped with a Waters 996 photodiode array detector and a TOSOH Bioscience TSKGEL GMHHR column (300 mm × 7.8 mm). Chloroform was used as elution solvent at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. Briefly, samples were dissolved in chloroform at a final concentration of 0.5% (w/v) and filtered (PTFE membrane, 0.22 μm) prior to analysis. Calibration curves were performed with polystyrene standards at a range from 500 to 31.5 · 106 g mol−1. Integration and molecular weight calculations were carried out using Empower GPC software (Waters).

Phase contrast, scanning electron, and transmission electron microscopy

Cultures were routinely visualized using a 100X phase-contrast objective and images taken with a Leica DFC345 FX camera. For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), co-cultures of B. bacteriovorus HD100/P. putida KT2440 co-cultures were harvested, washed twice with distilled sterile water, fixed with 2% (w/v) paraformaldehyde for 2 h at room temperature, and washed three times with distilled sterile water. The dried samples were mounted on aluminium stumps and sputter-coated with chromium before SEM examination using a Philips XL 30 device (acceleration voltage 15 kV). For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), the same co-cultures were harvested, washed twice in PBS and fixed in 5% (w/v) glutaraldehyde in the same solution, as previously described26. The cells were incubated with 2.5% (w/v) OsO4 for 1 h, gradually dehydrated in ethanol solutions and propylene oxide, and embedded in Epon 812 resin. Ultrathin sections (50–70 nm) were cut and observed using a Jeol-1230 electron microscope.

Statistical Analysis

Data sets were analysed using Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). Comparisons between two groups were made using Student’s‐test. Comparisons between multiple groups were made using one‐way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, depending whether one or two different variables were considered, respectively.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Martínez, V. et al. Engineering a predatory bacterium as a proficient killer agent for intracellular bio-products recovery: The case of the polyhydroxyalkanoates. Sci. Rep. 6, 24381; doi: 10.1038/srep24381 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Escolar and D. Gómez for help during microscopy work. A. Valencia, I. Calvillo and F. de la Peña are thanked for excellent technical assistance, as are M. Fernández and J. San Román for their assistance in the size exclusion chromatography experiments. This work was funded by the EU Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement no. 311815 (SYNPOL), and by grants from the Comunidad de Madrid (P2013/MIT2807) and the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, (BIO2010-21049, BIO2013-44878-R).

Footnotes

Author Contributions V.M. and M.A.P. designed the research, V.M. and C.H. performed the experimental work, and V.M., E.J. and M.A.P. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Jurkevitch E. & Davidov Y. Phylogenetic diversity and evolution of predatory prokaryotes. In Predatory Prokaryotes – Biology, Ecology, and Evolution. Jurkevitch E. (ed.). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag, pp. 11–56 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Sockett E. R. Predatory Lifestyle of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63, 523–539 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolp H. & Starr M. P. Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus Gen. et Sp. n., a predatory, ectoparasitic, and bacteriolytic microorganism. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 29, 217–248 (1963). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravenschlag K., Sahm K., Pernthaler J. & Amann R. High bacterial diversity in permanently cold marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 3982–3989 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkevitch E., Minz D., Ramati B. & Barel G. Prey range characterization, ribotyping, and diversity of soil and rhizosphere B. bacteriovorus spp. isolated on phytopathogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 2365–2371 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwudke D., Strauch E., Krueger M. & Appel B. Taxonomic studies of predatory bdellovibrios based on 16S rRNA analysis, ribotyping and the hit locus and characterization of isolates from the gut of animals. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 24, 385–394 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iebba V. et al. Higher prevalence and abundance of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus in the human gut of healthy subjects. PLoS One 16, e61608 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sockett E. R. & Lambert C. B. bacteriovorus as therapeutic agents: a predatory renaissance? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 669–675 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatzkes K. et al. Examining the safety of respiratory and intravenous inoculation of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus and Micavibrio aeruginosavorus in a mouse model. Sci. Rep. 5, 12899 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashiff A., Junka R. A., Libera M. & Kadouri D. E. Predation of human pathogens by the predatory bacteria Micavibrio aeruginosavorus and Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 110, 431–444 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atterbury R. J. et al. Effects of orally administered B. bacteriovorus bacteriovorus on the well-being and salmonella colonization of young chicks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 15, 5794–5803 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadouri D. E., To K., Shanks R. M. Q. & Doi Y. Predatory bacteria: a potential ally against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. PLoS One 1, e63397 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto M. A. et al. A holistic view of polyhydroxyalkanoate metabolism in Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12760 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanprateep S. Current trends in biodegradable polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biosci Bioeng. 110, 621–632 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudesh K., Abe H. & Doi Y. Synthesis, structure and properties of polyhydroxyalkanoates: biological polyesters. Prog. Polym. Sci. 25, 1503–1555 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Laycock B., Halley P., Pratt S., Werker A. & Lant P. The chemomechanical properties of microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Prog. Polym. Sci. 38, 536–583 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Yin J. & Chen G. Q. Polyhydroxyalkanoates, challenges and opportunities. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 30, 59–65 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortajada M., da Silva L. F. & Prieto M. A. Second-generation functionalized medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates: the gateway to high-value bioplastic applications. Int. Microbiol. 16, 1–15 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinjaski N. & Prieto M. A. Smart polyhydroxyalkanoate nanobeads by protein based functionalization. Nanomedicine, doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.01.018 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquel N., Lob C. W., Wei Y. H., Wu H. S. & Wang S. S. Isolation and purification of bacterial poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates). Biochem. Eng. J. 39, 15–27 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Madkour M. H., Heinrich D., Alghamdi M. A., Shabbaj I. I. & Steinbüchel A. PHA recovery from biomass. Biomacromolecules 9, 2963–2972 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler S. & Dennis D. Polyhydroxyalkanoate production in recombinant Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 103, 231–236 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resch S. et al. Aqueous release and purification of poly(b-hydroxybutyrate) from Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 65, 173–182 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Yin J., Li H., Yang S. & Shen Z. Construction and selection of the novel recombinant Escherichia coli strain for poly(b-hydroxybutyrate) production. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 89, 307–311 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori K., Kaneko M., Tanji Y., Xing X. H. & Unno H. Construction of self-disruptive Bacillus megaterium in response to substrate exhaustion for polyhydroxybutyrate production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 59, 211–216 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez V., García P., García J. L. & Prieto M. A. Controlled autolysis facilitates the polyhydroxyalkanoate recovery in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Microb. Biotechnol. 4, 533–547 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez V., Jurkevitch E., García J. L. & Prieto M. A. Reward for Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus for preying on a polyhydroxyalkanoate producer. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 1204–1215 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendulic S. et al. A predator unmasked: life cycle of B. bacteriovorus bacteriovorus from a genomic perspective. Science 303, 689–692 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez V. et al. Identification and biochemical evidence of a medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate depolymerase in the Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus predatory hydrolytic arsenal. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 6017–6026 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbahloul Y. & Steinbüchel A. Large-scale production of poly(3-hydroxyoctanoic acid) by Pseudomonas putida GPo1 and a simplified downstream process. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 643–651 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Eugenio L. I. et al. Biochemical evidence that phaZ gene encodes a specific intracellular medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoate depolymerase in Pseudomonas putida KT2442: characterization of a paradigmatic enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 4951–4962 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Eugenio L. I. et al. The turnover of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates in Pseudomonas putida KT2442 and the fundamental role of PhaZ depolymerase for the metabolic balance. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 207–221 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jendrossek D. & Handrick R. Microbial degradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56, 403–432 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll M., Hamm T. M., Wagner F., Martínez V. & Pleiss J. The PHA depolymerase engineering database: a systematic analysis tool for the diverse family of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) depolymerases. BMC Bioinform. 10, 89 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahar P. et al. Effective production and kinetic characterization of ultra-high-molecular-weight poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate] in recombinant Escherichia coli. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 87, 161–169 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Uchino K., Saito T. & Jendrossek D. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) depolymerase PhaZa1 is involved in mobilization of accumulated PHB in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 1058–1063 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddon C. J. & Keasling J. D. Semi-synthetic artemisinin: a model for the use of synthetic biology in pharmaceutical development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 355–367 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuenen J. G. & Rittenberg S. C. Incorporation of long-chain fatty acids of the substrate organism by Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus during intraperiplasmic growth. J. Bacteriol. 121, 1145–1157 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby E. G. & McCabe J. B. An ATP transport system in the intracellular bacterium Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus 109J. J. Bacteriol. 167, 1066–1070 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J. & Russell D. W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press (2001).

- Peoples O. P. & Sinskey A. J. Poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) biosynthesis in Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. Identification and characterization of the PHB polymerase gene (phbC). J Biol Chem. 264, 15298–15303 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldes C., García P., García J. L. & Prieto M. A. In vivo immobilization of fusion proteins on bioplastics by the novel tag BioF. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 3205–3212 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert C., Smith M. C. & Sockett R. E. A novel assay to monitor predator-prey interactions for Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus 109 J reveals a role for methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins in predation. Environ. Microbiol. 5, 127–132 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer A. et al. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145, 69–73 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.