Abstract

AIM

The aim of this meta‐analysis was to evaluate the effect of statin therapy on plasma FFA concentrations in a systematic review and meta‐analysis of controlled clinical trials.

Methods

PubMed‐Medline, SCOPUS, Web of Science and Google Scholar databases were searched (from inception to February 16 2015) to identify controlled trials evaluating the impact of statins on plasma FFA concentrations. A systematic assessment of bias in the included studies was performed using the Cochrane criteria. A random effects model and generic inverse variance method were used for quantitative data synthesis. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using the leave‐one‐out method. Random effects meta‐regression was performed using unrestricted maximum likelihood method to evaluate the impact of potential moderators.

Results

Meta‐analysis of data from 14 treatment arms indicated a significant reduction in plasma FFA concentrations following treatment with statins (weighted mean difference (WMD) –19.42%, 95% CI –23.19, −–15.64, P < 0.001). Subgroup analysis confirmed the significance of the effect with both atorvastatin (WMD –20.56%, 95% CI –24.51, –16.61, P < 0.01) and simvastatin (WMD –18.05%, 95% CI –28.12, –7.99, P < 0.001). Changes in plasma FFA concentrations were independent of treatment duration (slope –0.10, 95% CI –0.30, 0.11, P = 0.354) and magnitude of reduction in plasma low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations (slope 0.55, 95% CI –0.17, 1.27, P = 0.133) by statins.

Conclusions

The results of the present study suggest that statin therapy may lower plasma FFA concentrations. The cardiovascular and metabolic significance of this finding requires further investigation.

Keywords: cholesterol, dyslipidaemia, fatty acid, meta‐analysis, statins

What is Already Known about this Subject

The main effect of statins is to decrease plasma low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) and triglycerides and increase high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels.

Previous reports have suggested that free fatty acids (FFAs) may contribute to coronary heart disease by either promoting atherogenesis or thrombogenesis.

Studies evaluating the effects of statins on serum fatty acid metabolism in humans are lacking and published data contradictory.

What this Subject Adds

Results of this meta-analysis revealed a significant reduction in plasma FFAs following treatment with statins.

Changes in plasma FFA concentrations were independent of statin type, treatment duration, and magnitude of LDL-C reduction.

Introduction

Inhibitors of 3‐hydroxy‐3methyl‐glutaryl coenzyme A (HMG‐CoA), are known for their established efficacy in decreasing cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in both primary and secondary prevention 1, 2, 3, 4. The main effect of statins is reducing plasma low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) concentrations 5. In addition, statin therapy can reduce triglycerides and increase high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol concentrations plus a plethora of non‐lipid pleiotropic actions 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12.

FFAs are non‐esterified fatty acids that are released from adipocyte triglyceride stores following lipolysis, and from phospholipids after hydrolysis by phospholipases 13. FFAs promote the formation and release of triglycerides by the liver leading to an overproduction of very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) 14, 15 and consequent development of atherogenic dyslipidaemia. On the other hand, overproduction of VLDL and LDL can increase the flux of plasma FFAs to the liver causing hepatic insulin resistance and inflammation 16, 17.

Fatty acid metabolism was once considered to be unchanged by statin therapy 18, 19, 20. However, mild elevations in fatty acid synthesis were subsequently reported in animal models 21 cultured cells 22, and after statin treatment in mice 23. Moreover, statins may also inhibit hepatic synthesis of apolipoprotein B‐100 and decrease the synthesis and secretion of triglyceride‐rich lipoproteins 24, 25. The molecular mechanism by which statins reduce triglycerides levels is not known with certainty. In this regard, statins could affect hepatic FFA metabolism 26. However, studies evaluating the effects of statins on serum fatty acid metabolism in humans are lacking and published data are contradictory 27. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of statin therapy on plasma FFA concentrations and calculate the size of this effect using a systematic review and meta‐analysis of controlled clinical trials.

Methods

Search strategy

This study was designed according to the guidelines of the 2009 preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analysis (PRISMA) statement 28. PubMed‐Medline, SCOPUS, Web of Science and Google Scholar databases were searched using the following search terms in titles and abstracts (also in combination with MESH terms): (atorvastatin OR simvastatin OR rosuvastatin OR fluvastatin OR pravastatin OR pitavastatin OR lovastatin OR cerivastatin OR ‘statin therapy’ OR statins) AND (‘free fatty acid’ OR ‘free fatty acids’ OR FFA OR FFAs). The wild‐card term ‘*’ was used to increase the sensitivity of the search strategy. No language restriction was used in the literature search. The search was limited to studies in humans. The literature was searched from inception to February 16 2015.

Study selection

Original studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (i) being a controlled trial with either parallel or crossover design, (ii) investigating the impact of statin therapy, either as monotherapy or combination therapy, on plasma/serum concentrations of FFAs, (iii) treatment duration of at least 2 weeks and (iv) presentation of sufficient information on FFA concentrations at baseline and at the end of follow‐up in each group or providing the net change values. Exclusion criteria were (i) non‐interventional trials, (ii) lack of an appropriate control group for statin therapy, (iii) observational studies with case–control, cross‐sectional or cohort design and (iv) lack of sufficient information on baseline or follow‐up FFA concentrations.

Data extraction

Eligible studies were reviewed and the following data were abstracted: 1) first author's name, 2) year of publication, 3) study location, 4) study design, 5) number of participants in the statin and control groups, 5) age, gender and body mass index (BMI) of study participants, 6) baseline concentrations of total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C), and triglycerides, 7) systolic and diastolic blood pressures and 8) data regarding baseline and follow‐up concentrations of FFAs.

Quality assessment

A systematic assessment of bias in the included studies was performed using the Cochrane criteria 29. The items used for the assessment of each study were as follows: adequacy of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, addressing of dropouts (incomplete outcome data), selective outcome reporting and other potential sources of bias. According to the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook, a judgment of ‘yes’ indicated low risk of bias, while ‘no’ indicated high risk of bias. Labelling an item as ‘unclear’ indicated an unclear or unknown risk of bias.

Quantitative data synthesis

Meta‐analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis (CMA) V2 software (Biostat, NJ) 30. Net changes in measurements (change scores) were calculated as follows: measure at end of follow‐up − measure at baseline. For single arm crossover trials, net change in plasma concentrations of FFA were calculated by subtracting the value after control intervention from that reported after treatment. All values were collated as percent change from baseline in each group, or percent change in the statin group relative to control group. Standard deviations (SDs) of the mean difference were calculated using the following formula: SD = square root [(SDpre‐treatment)2 + (SDpost‐treatment)2 – (2R × SDpre‐treatment × SDpost‐treatment)], assuming a correlation coefficient (r) = 0.5. If the outcome measures were reported in median and range (or 95% confidence interval [CI]), mean and standard SD values were estimated using the method described by Hozo et al. 31. Where standard error of the mean (SEM) was only reported, standard deviation (SD) was estimated using the following formula: SD = SEM × square root (n), where n is the number of subjects. To avoid the problem of double‐counting in randomized controlled trials with multiple treatment arms and a common control group, the number of subjects in the control group was divided by the required comparisons.

A random effects model (using the DerSimonian–Laird method) and the generic inverse variance method were used to compensate for the heterogeneity of studies in terms of demographic characteristics of populations being studied and also differences in study design and type of statin being studied 32. Heterogeneity was quantitatively assessed using I2 index. Effect sizes were expressed as weighed mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Subgroup analyses were carried out to explore the impact of statin type and treatment duration (< 12 weeks vs. ≥12 weeks) on plasma FFA concentrations. In order to evaluate the influence of each study on the overall effect size, sensitivity analysis was conducted using the leave‐one‐out method, i.e. removing one study each time and repeating the analysis [33‐35].

Meta‐regression

Random effects meta‐regression was performed using the unrestricted maximum likelihood method to evaluate the association between calculated WMD and potential moderators including duration of treatment with statins, dose of treatment (expressed as equivalent dose of atorvastatin) and magnitude of LDL‐C reduction by statin therapy.

Publication bias

Potential publication bias was explored using visual inspection of Begg's funnel plot asymmetry, Begg's rank correlation and Egger's weighted regression tests. Duval & Tweedie ‘trim and fill’ and ‘fail‐safe N’ methods were used to adjust the analysis for the effects of publication bias [36].

Results

Flow and characteristics of included studies

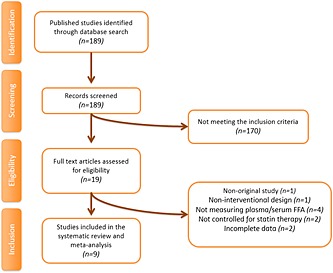

Firstly, 189 published studies were identified following the database search. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 170 studies did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. Then, 19 full text articles were carefully assessed and reviewed. Ten of these studies were excluded for the following reasons: non‐interventional design (n = 1), being non‐original (n = 1), presenting incomplete data (n = 2), not measuring plasma/serum FFA concentrations (n = 4) and not being controlled for statin therapy (n = 2). Finally, nine eligible studies with 14 treatment arms were included in the systematic review and meta‐analysis. The study selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the number of studies identified and included into the meta‐analysis

A total of 764 individuals were incorporated in the nine eligible controlled trials, including 462 and 302 subjects in the statin and control groups (participants from the crossover trials were counted in both treatment and control groups), respectively. Included studies were published between 1991 and 2014. The clinical trials used only atorvastatin and simvastatin but with different doses. Two studies used atorvastatin 10 mg day–1 37, 38, one study atorvastatin 20 mg day–1 39, one study atorvastatin 80 mg day–1 38, one study simvastatin 10 mg day–1 40, one study simvastatin 20 mg day–1 41, one study simvastatin 30 mg day–1 42, three studies simvastatin 40 mg day–1 41, 43, 44 and one study simvastatin 80 mg day–1 45. The range of intervention periods was from 3 weeks 42 to 2 years 41. Study designs of included studies were parallel 38, 39, 40, 41, 43, 44, 45 and crossover 37, 42. Selected trials enrolled subjects with primary hypercholesterolaemia 41, 43, 44, type 2 diabetes 38, 42, 45, metabolic syndrome 37, 40 and mixed dyslipidaemia 39 (Table 1). Finally, most of the included studies measured FFA concentrations using an enzymatic assay method 38, 40, 41, 43, 44, 45, while three trials did not specify the method used 37, 39, 42.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Study design | Target population | Treatment duration | n | Study groups | Age (years)s | Female (n, %) | BMI, ( kg m – 2 ) | Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Total cholesterol (mgdl–1 ) | LDL cholesterol (mg dl –1 ) | HDL cholesterol (mg dl –1 ) | Triglycerides (mg dl –1 ) | FFA (mmol l –1 ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bays et al. 39 * | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Parallel group | Overweight and mixed dyslipidaemia | 8 weeks | 31 28 32 31 30 29 | Control MBX‐8025, 50 mg day–1 MBX‐8025, 100 mg day–1

Atorvastatin 20 mg day–1

MBX‐8025, 50 mg day–1 + atorvastatin 20 mg day–1 MBX‐8025, 100 mg day–1 + atorvastatin 20 mg day–1 |

54.9 ± 1.5

54.3 ± 2.2 54.6 ± 1.9 54.3 ± 1.9 54.6 ± 1.7 52.6 ± 1.7 |

15 (48.0)

11 (39.0) 17 (53.0) 18 (58.0) 18 (60.0) 16 (55.0) |

33.4 ± .08

33.5 ± 1.3 31.8 ± 0.6 34.0 ± 1.2 33.8 ± 1.1 35.2 ± 1.1 |

ND ND ND ND ND ND | ND ND ND ND ND ND | 251.7 ± 5.8

254.6 ± 6.1 250.6 ± 6.4 245.4 ± 5.5 258.4 ± 6.6 239.8 ± 4.8 |

160.7 ± 4.3

169.3 ± 5.0 163.6 ± 6.3 165.1 ± 5.0 175.0 ± 5.3 157.6 ± 3.1 |

43.6 ± 1.3

44.6 ± 1.2 44.3 ± 1.7 42.7 ± 1.5 44.8 ± 1.5 42.6 ± 1.2 |

254.6 ± 22.5

214.8 ± 14.0 236.3 ± 16.3 199.8 ± 11.6 196.2 ± 13.5 211.6 ± 13.9 |

0.6 ± 0.0

0.6 ± 0.0 0.6 ± 0.1 0.6 ± 0.0 0.5 ± 0.0 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| Huptas et al. 37 | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Crossover | Metabolic syndrome | 6 weeks | 10 | Control Atorvastatin 10 mg day–1 | 40 ± 12 | 0 (0.0) | 33.6 ± 5.2 | ND | ND | 208 ± 46 164 ± 41 | 125 ± 43 85 ± 30 | 45.0 ± 11.4 47.6 ± 10.5 | 198 ± 122 192 ± 188 | 0.96 ± 0.49 0.52 ± 0.17 |

| Krysiak et al. 43 | Placebo‐controlled Parallel | Primary hypercholesterolaemia | 12 weeks | 21 23 21 | Control Simvastatin 40 mg day–1 Simvastatin 40 mg day–1+ ezetimibe 10 mg day–1 | 51.1 ± 2.6

51.9 ± 2.7 52.5 ± 3.5 |

9 (43)

9 (39) 9 (43) |

26.8 ± 2.7

26.7 ± 2.3 26.5 ± 2.4 |

ND ND ND | ND ND ND | 250 ± 15

192 ± 13 156 ± 12 |

175 ± 13

128 ± 11 98 ± 9 |

47 ± 4

49 ± 5 54 ± 4 |

112 ± 13

107 ± 14 105 ± 18 |

0.34 ± 0.04

0.24 ± 0.02 0.20 ± 0.02 |

| Krysiak et al. 44 | Placebo‐controlled Parallel | Primary hypercholesterolemia | 30 days | 17 22 | Control Simvastatin 40 mg day–1 | 50.7 ± 2.6 51.8 ± 2.6 | 8 (47) 9 (41) | 27.2 ± 2.6 26.3 ± 2.5 | ND ND | ND ND | 246 ± 14 191 ± 13 | 175 ± 14 128 ± 11 | 48 ± 5 49 ± 5 | 119 ± 12 113 ± 15 | 0.32 ± 0.05 0.30 ± 0.03 |

| Mitropoulos et al. 41 | Randomized, placebo‐controlled | Primary hypercholesterolaemia | 2 years | 54 57 51 | Simvastatin 40 mg/day Simvastatin 20 mg day–1 Control | 62.6 ± 6.7

62.5 ± 7.6 64.0 ± 6.2 |

6 (11.1)

8 (14.0) 10 (19.6) |

26.0 ± 2.7

25.8 ± 3.5 26.7 ± 4.2 |

ND ND ND | ND ND ND | 194.9 ± 34.8

233.6 ± 64.2 273.0 ± 45.2 |

95.5 ± 25.1 ND 162.8 ± 35.2 | 62.6 ± 15.1 ND 58.4 ± 14.7 | 146.1 ± 71.7

131.1 ± 64.7 185.1 ± 94.8 |

0.32 ± 0.21

0.34 ± 0.21 0.41 ± 0.23 |

| Paolisso et al. 42 | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over | Type 2 diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia | 3 weeks | 12 | Control Simvastatin 30 mg day–1 | 72.3 ± 1.4 | 6 (50.0) | 27.2 ± 0.6 | ND | ND | 305.5 ± 11.6 204.9 ± 7.7 | 278.4 ± 15.5 166.3 ± 11.6 | 23.2 ± 7.7 34.8 ± 11.6 | 256.9 ± 35.4 186.0 ± 17.7 | 1.10 ± 0.21 0.81 ± 0.10 |

| Plat et al. 40 * | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled parallel | Metabolic syndrome | 8 weeks | 9 10 9 8 | Control Simvastatin 10 mg day–1Plant stanols Simvastatin 10 mg day–1 + plant stanols | 60 ± 7

61 ± 8 60 ± 4 60 ± 8 |

4 (44.4)

4 (40.0) 2 (22.2) 3 (37.5) |

30.2 ± 1.9

29.2 ± 3.3 28.1 ± 2.6 29.7 ± 7.5 |

142 ± 14

139 ± 7 138 ± 11 150 ± 30 |

92 ± 10

89 ± 7 94 ± 8 96 ± 21 |

250.2 ± 57.6

247.5 ± 43.7 288.1 ± 49.1 280.4 ± 47.6 |

ND ND ND ND | 45.6 ± 7.7

43.3 ± 8.9 44.9 ± 7.3 45.2 ± 16.2 |

174.5 ± 80.6

203.7 ± 75.3 128.4 ± 44.3 177.1 ± 81.5 |

0.30 ± 0.10

0.39 ± 0.14 0.29 ± 0.10 0.29 ± 0.08 |

| DALI Study Group 38 | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled parallel | Type 2 diabetes and dyslipidaemia | 30 weeks | 72 73 72 | Control Atorvastatin 10 mg day–1 Atorvastatin 80 mg day–1 | 58.5 ± 7.5

59.7 ± 7.6 60.1 ± 7.7 |

26 (36.1) 13 (17.8) | 32.2 ± 6.0

30.0 ± 3.8 30.4 ± 4.5 |

144 ± 19

146 ± 17 145 ± 17 |

85 ± 9

86 ± 10 85 ± 9 |

232.0 ± 3.9

158.5 ± 3.9 139.2 ± 3.9 |

139.2 ± 3.9

85.1 ± 3.9 65.7 ± 3.9 |

40.2 ± 1.2

42.5 ± 1.5 42.2 ± 1.5 |

255.1 ± 19.5

163.0 ± 8.9 157.7 ± 14.2 |

0.72 ± 0.04

0.57 ± 0.03 0.61 ± 0.03 |

| Szendroedi et al. 45 | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled parallel | Type 2 diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia | 2 months | 10 10 | Simvastatin 80 mg day–1 Control | 55 ± 6 58 ± 8 | 3 (30.0) 5 (50.0) | 28.9 ± 3.5 27.3 ± 3.7 | ND ND | ND ND | 197.2 ± 38.7 255.2 ± 30.9 | 108.3 ± 34.8 162.4 ± 19.3 | 54.1 ± 11.6 54.1 ± 11.6 | 132.9 ± 35.4 186.0 ± 70.9 | 0.39 ± 0.13 0.60 ± 0.23 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD. *Only basal conditions. ND, no data; BMI, body mass index; FFA, free fatty acids; DALI, Diabetes Atorvastatin Lipid Intervention.

Risk of bias assessment

Seven included studies were characterized by lack of information about the sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors 37, 38, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45. In addition, two studies had high risk of bias for sequence generation and allocation concealment 43, 44. However, six evaluated studies showed low risk of bias with respect to selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias 38, 39, 40, 41, 43, 45. Finally, all trials had low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data. Details of the quality of bias assessment are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality of bias assessment of the included studies according to the Cochrane guidelines

| Study | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bays et al. 39 | L | L | U | L | L | L |

| Huptas et al. 37 | U | U | U | L | U | L |

| Krysiak et al. 43 | H | H | L | L | L | L |

| Krysiak et al. 44 | H | H | L | L | L | U |

| Mitropoulos et al. 41 | U | U | L | L | L | L |

| Paolisso et al. 42 | U | U | U | L | U | L |

| Plat et al. 40 | U | L | L | L | L | L |

| DALI Study Group 38 | U | U | U | L | L | L |

| Szendroedi et al. 45 | U | U | U | L | L | L |

L, low risk of bias; H, high risk of bias; U, unclear risk of bias.

Effect of statin therapy on plasma FFA concentrations

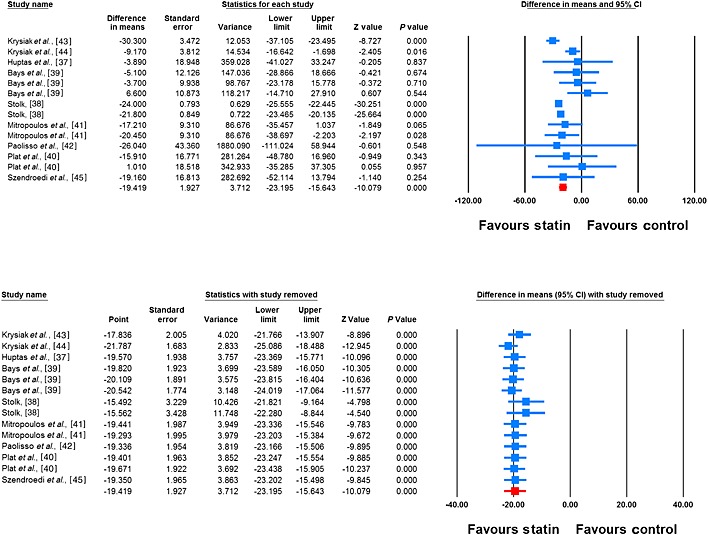

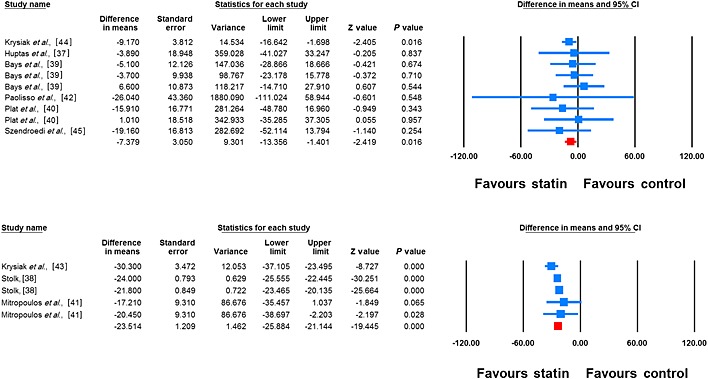

Meta‐analysis of data from 14 treatment arms revealed a significant reduction in plasma FFAs following treatment with statins (WMD –19.42%, 95% CI –23.19, –15.64, P < 0.001; I2 65.27%). This effect was robust in the sensitivity analysis (Figure 2). In subgroup analysis, reductions in plasma FFA concentrations were observed in both subsets of trials with treatment durations <12 weeks (WMD –7.38%, 95% CI –13.36, –1.40, P = 0.016; I2 0%) and ≥12 weeks (WMD –23.51%, 95% CI –25.88, –21.14, P < 0.001; I2 52.41%), though the effect size was numerically greater in the latter group (Figure 3). With respect to the type of statin, there were significant reductions in plasma FFA concentrations with both atorvastatin (WMD –20.56%, 95% CI –24.51, –16.61, P < 0.01; I2 71.91%) and simvastatin (WMD –18.05%, 95% CI –28.12, –7.99, P < 0.001; I2 61.81%) (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Forest plot displaying weighted mean difference and 95% confidence intervals for the impact of statin therapy on plasma FFA concentrations (I2 65.27%). Lower plot shows leave‐one‐out sensitivity analysis

Figure 3.

Forest plot displaying weighted mean difference and 95% confidence intervals for the impact of statin therapy on plasma FFA concentrations in trials with treatment durations of <12 weeks (upper plot) (I2 0%) and ≥12 weeks (lower plot) (I2 52.41%)

Figure 4.

Forest plot displaying weighted mean difference and 95% confidence intervals for the impact of atorvastatin (upper plot) (I2 71.91%) and simvastatin (lower plot) (I2 61.81%) on plasma FFA concentrations

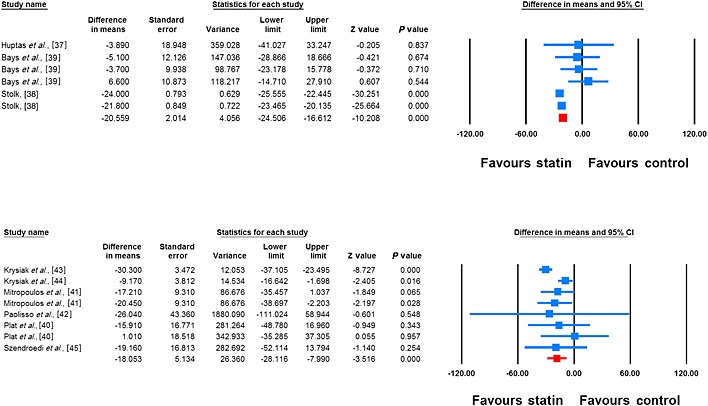

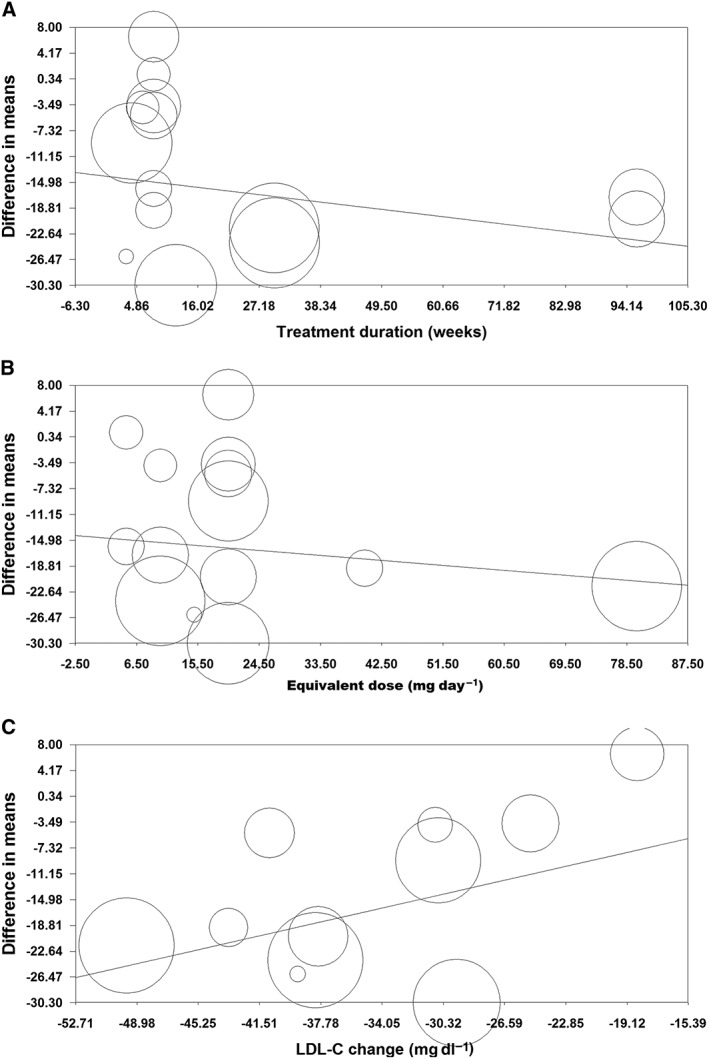

Meta‐regression

Random effects meta‐regression was performed to evaluate the impact of potential moderators on the estimated effect size. Changes in plasma FFA concentrations were independent of treatment duration (slope –0.10, 95% CI –0.30, 0.11, P = 0.354), statin dose (slope –0.08, 95% CI –0.33, 0.16, P = 0.514) and magnitude of LDL‐C reduction (slope 0.55, 95% CI –0.17, 1.27, P = 0.133) by statins (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Meta‐regression plots of the association between mean changes in plasma FFA concentrations with duration of statin therapy (A), statin dose (expressed as equivalent dose of atorvastatin; B) and magnitude of LDL‐C reduction (C)

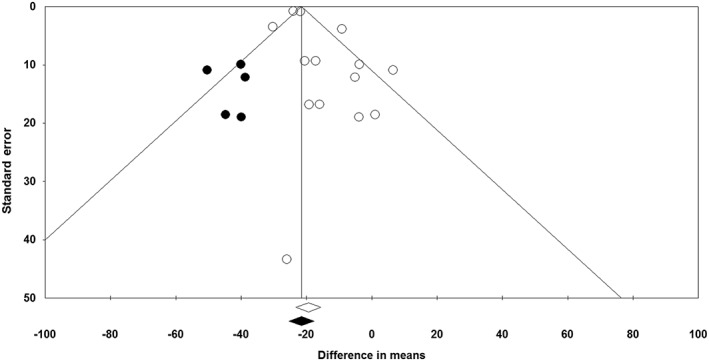

Publication bias

The funnel plot of standard error vs. effect size (mean difference) was asymmetric and suggested potential publication bias. Presence of publication bias was also suggested by Egger's linear regression (intercept =1.05, standard error = 0.48; 95% CI = 0.004, 2.10, t = 2.19, df = 12.00, two‐tailed P = 0.049) but not Begg's rank correlation test (Kendall's Tau with continuity correction =0, z = 0, two‐tailed P value =1.000). After adjustment of effect size for potential publication bias using the ‘trim and fill’ correction, five potentially missing studies on the left side of the funnel plot were imputed leading to a corrected effect size that was greater than the initial estimate (WMD –21.54%, 95% CI –25.44, –17.64) (Figure 6). The ‘fail‐safe N’ test showed that 1417 studies would be needed to bring the WMD down to a non‐significant (P > 0.05) value.

Figure 6.

Funnel plot displaying publication bias in the studies reporting the impact of statin therapy on plasma FFA concentrations. Open diamond represents observed effect size; closed diamond represents imputed effect size

Discussion

The findings of the present meta‐analysis suggest that statins are associated with a significant reduction in the plasma concentrations of FFAs. This effect that was independent of statin type, treatment duration and dose and magnitude of changes in plasma LDL‐C concentrations. It has been reported that high concentrations of FFAs induce oxidative stress, inflammation and insulin resistance by activating the nuclear factor‐kappa B pathway and promoting increased reactive oxidant species 17. Therefore, the decrease in FFA concentrations after statin therapy may have important clinical implications slowing the progression of atherogenesis and consequently a lower cardiovascular risk. However, these potential effects of statins as antioxidant and anti‐inflammatory through the reduction of FFA concentrations are still uncertain and remain to be clarified in further studies. Although the effect of statins on FFA metabolism is unclear, there are several mechanisms which may be involved. In this regard, acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase and fatty acid synthase, two important regulatory enzymes in fatty acid biosynthesis, could be regulated simultaneously by HMG‐CoA reductase enzyme at the genomic level. Therefore, activity of both enzymes could be influenced by statin therapy 46, 47. Since HMG‐CoA reductase and acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase are reversibly inactivated through phosphorylation by AMP‐activated protein kinase 48, down regulation of this enzyme by sterol deficiency would increase acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase activity after statin therapy when regulatory sterols are absent 49. In addition, a pleiotropic effect of statins on peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐α (PPARα) expression has been described. Statins activate PPARα, which increases the hepatic fatty acid uptake and promotes the transformation of fatty acids to acyl‐coenzyme A, resulting in increased β‐oxidation and reduced availability of fatty acids 50. However, available data on the effects of statins on plasma FFA concentrations in humans is still limited and is based on small scale studies. The aim of the present study was to obtain more robust evidence on the impact of statins on plasma FFA concentrations through combining individual studies and applying a random effects meta‐analysis.

Circulating FFAs mainly derive from adipose tissue lipolysis by the action of lipase. Hepatic FFAs are available from de novo lipogenesis and uptake of triglyceride‐rich lipoproteins, cholesteryl esters, and plasma FFAs. Fatty acid derivatives can serve as ligands for the peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptors (PPARs) 51, particularly PPAR‐α which is considered as the most important regulator of intra and extracellular fatty acid metabolism. In fact, PPAR‐α activation decreases VLDL synthesis and secretion, increases plasma HDL, decreases triglyceride concentrations and enhances fatty acid oxidation 52. Interestingly, lipid lowering drugs have shown a reduction of serum total fatty acid concentration while simultaneously increasing the proportion of long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and precursor fatty acids for eicosanoid production 53. Circulating total fatty acids are found in different forms: 45% in triacylglycerols, 15% in cholesteryl esters, 35% in phospholipids and about 5% as non‐esterified free fatty acids 53. Between 75% and 80% of serum cholesterol is esterified with fatty acids and only 20% to 25% is non‐esterified cholesterol 53. Nonetheless, statins appear to exert their effects on the metabolism and serum composition of FFAs through disturbing the biogenesis of isolated fatty acids independently of the mechanism that regulates lipoprotein synthesis and secretion. In this context, the results of meta‐regression analysis revealed that changes in plasma FFA concentrations were independent of the magnitude of LDL‐C reduction. This lack of dependence of FFA changes on the potency and duration of statin treatment is suggestive of a class effect that is independent of degree of inhibition of HMG‐CoA reductase. As referred to above, it is likely that enhancement of PPAR‐α expression and activity in liver and muscle tissues is responsible for the FFA‐reducing effect through increasing FFA uptake, FFA conversion to acyl‐CoA and β‐oxidation of FFAs 54.

There is evidence indicating that treatment with statins is a risk factor for the development of new onset type 2 diabetes 55, though the causes of this negative effect remain unexplained. In this regard, it has been suggested that statins may contribute to insulin resistance and impair β‐cell function 56. In animal models, long term treatment with statins increased insulin resistance in the adipose tissue 57. There is evidence indicating that both increased efflux of FFAs from adipose tissue and impaired insulin‐mediated skeletal muscle uptake of FFAs increase fatty acid flux to the liver promoting the development of peripheral insulin resistance 58, 59. The association between plasma FFA concentrations and insulin resistance has been supported by epidemiological studies 60. There is robust evidence from published meta‐analyses indicating that although statin therapy increases the risk of new‐onset diabetes, the risk is not equivalent for all statins. It has been reported that the diabetogenic effect of statins depends on the type (being highest with rosuvastatin) and dose of statins (a higher risk at higher doses) 61, 62. In this context, it is important to note that none of the studies included in the present meta‐analysis included a rosuvastatin arm, and except one trial, all other included studies used a mild to moderate intensity statin therapy regimen. Hence, the overall set of trials included in this meta‐analysis may not fully represent the impact of a highly diabetogenic statin regimen on plasma concentrations of FFAs, and future studies are required to see if a similar or differential effect on plasma FFAs could be seen in trials with rosuvastatin and high intensity statin regimens. Moreover, in spite of some controversies, it has been shown that in diabetic subjects statin therapy is not associated with an adverse impact on glycaemic index and insulin resistance 63. Therefore, since diabetes was either the main inclusion criteria or comorbidity in most of the studies included in the present meta‐analysis, it is unlikely that the diabetogenic effect of statins has occurred predominantly in the overall population studied in our analysis. Hence, further evidence is required to clarify if the FFA‐reducing effect of statins can be replicated in non‐diabetic subjects receiving high intensity statins, particularly rosuvastatin.

Some limitations of this study should be mentioned. The most important one was the small sample size in several of the included studies. As another limitation, changes in plasma FFA concentrations were not among the primary objectives of the included studies. Thus, further studies are warranted to evaluate the effect of statin therapy on FFA concentrations as primary outcome to obtain more robust evidence about the effects of statins on circulating FFA status. Finally, the diversity of statin types in the included studies was low and administered statins were limited to atorvastatin and simvastatin. While this may reduce the inter‐study heterogeneity, it limits the generalizability of findings to other statin types.

Conclusion

In conclusion, results of this meta‐analysis, being the first of its kind, showed that statin therapy significantly reduces plasma FFA concentrations. Future investigations are required to clarify if this effect of statin therapy accounts, at least in part, for the established cardiovascular benefits of these drugs. Also, the association of this effect of statins with the hepatic content of FFAs and risk of hepatic insulin resistance needs to be elucidated in future studies. Finally, the magnitude of the FFA lowering effects of statins in comparison with other conventional and novel lipid lowering therapies 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 remains to be clarified.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form and declare no support from any organization for the submitted work. GFW has received honoraria for lectures and commentaries, outside the submitted work, from Genfit, Pfizer, Astrazeneca, MSD, Novartis, Amgen and Sanofi‐Aventis in the previous 3 years. There are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author Contributions

AM conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the statistical analyses and interpretation of data, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. LES‐M drafted the initial manuscript, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. CP critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. GF critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. PN critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. SB critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. GD critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. PM critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. GFW critically reviewed the manuscript, interpreted data and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Sahebkar, A. , Simental‐Mendía, L. E. , Pedone, C. , Ferretti, G. , Nachtigal, P. , Bo, S. , Derosa, G. , Maffioli, P. , and Watts, G. F. (2016) Statin therapy and plasma free fatty acids: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of controlled clinical trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 81: 807–818. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12854.

References

- 1. Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, Moore TH, Burke M, Davey Smith G, Ward K, Ebrahim S. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 1: CD004816. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004816.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, Kirby A, Sourjina T, Peto R, Collins R, Simes R; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaborators . Efficacy and safety of cholesterol‐lowering treatment: prospective meta‐analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005; 366: 1267‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Erqou S, Sever P, Jukema JW, Ford I, Sattar N. Statins and all‐cause mortality in high‐risk primary prevention: a meta‐analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials involving 65,229 participants. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170: 1024–31. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vrecer M, Turk S, Drinovec J, Mrhar A. Use of statins in primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke. Meta‐analysis of randomized trials. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2003; 41: 567–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bilheimer DW, Grundy SM, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Mevinolin and colestipol stimulate receptor‐mediated clearance of low density lipoprotein from plasma in familial hypercholesterolemia heterozygotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1983; 80: 4124–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schaefer EJ, McNamara JR, Tayler T, Daly JA, Gleason JL, Seman LJ, Ferrari A, Rubenstein JJ. Comparisons of effects of statins (atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin) on fasting and postprandial lipoproteins in patients with coronary heart disease versus control subjects. Am J Cardiol 2004; 93: 31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones PH, Davidson MH, Stein EA, Bays HE, McKenney JM, Miller E, Cain VA, Blasetto JW; STELLAR Study Group . Comparison of the efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin across doses (STELLAR* trial). Am J Cardiol 2003; 92: 152‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Serban C, Sahebkar A, Ursoniu S, Mikhailidis DP, Rizzo M, Lip GY, Kees Hovingh G, Kastelein JJ, Kalinowski L, Rysz J, Banach M. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the effect of statins on plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine concentrations. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 9902. doi:10.1038/srep09902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sahebkar A, Serban C, Mikhailidis DP, Undas A, Lip GY, Muntner P, Bittner V, Ray KK, Watts GF, Hovingh GK, Rysz J, Kastelein JJ, Banach M; Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta‐analysis Collaboration (LBPMC) Group . Association between statin use and plasma D‐dimer levels. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. Thromb Haemost 2015; 114: 546‐57. doi:10.1160/TH14-11-0937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sahebkar A, Kotani K, Serban C, Ursoniu S, Mikhailidis DP, Jones SR, Ray KK, Blaha MJ, Rysz J, Toth PP, Muntner P, Lip GY, Banach M; Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta‐analysis Collaboration (LBPMC) Group . Statin therapy reduces plasma endothelin‐1 concentrations: aA meta‐analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials. Atherosclerosis 2015;241:433‐42. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sahebkar A, Ponziani MC, Goitre I, Bo S. Does statin therapy reduce plasma VEGF levels in humans? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Metabolism 2015; 64: 1466–76. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parizadeh SM, Azarpazhooh MR, Moohebati M, Nematy M, Ghayour‐Mobarhan M, Tavallaie S, Rahsepar AA, Amini M, Sahebkar A, Mohammadi M, Ferns GA. Simvastatin therapy reduces prooxidant‐antioxidant balance: results of a placebo‐controlled cross‐over trial. Lipids 2011; 46: 333–40. doi:10.1007/s11745-010-3517-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mozaffarian D. Free fatty acids, cardiovascular mortality, and cardiometabolic stress. Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 2699–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goh EH, Heimberg M. Stimulation of hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis by oleic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1973; 55: 382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewis GF, Uffelman KD, Szeto LW, Weller B, Steiner G. Interaction between free fatty acids and insulin in the acute control of very low density lipoprotein production in humans. J Clin Invest 1995; 95: 158–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kwiterovich PO Jr Clinical relevance of the biochemical, metabolic, and genetic factors that influence low‐density lipoprotein heterogeneity. Am J Cardiol 2002; 90: 30i–47i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tripathy D, Mohanty P, Dhindsa S, Syed T, Ghanim H, Aljada A, Dandona P. Elevation of free fatty acids induces inflammation and impairs vascular reactivity in healthy subjects. Diabetes 2003; 52: 2882–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaneko I, Hazama‐Shimada Y, Endo A. Inhibitory effects on lipid metabolism in cultured cells of ML‐236B, a potent inhibitor of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme‐a reductase. Eur J Biochem 1978; 87: 313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alberts AW. Discovery, biochemistry and biology of lovastatin. Am J Cardiol 1988; 62: 10J–5J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fears R, Richards DH, Ferres H. The effect of compactin, a potent inhibitor of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme‐a reductase activity, on cholesterogenesis and serum cholesterol levels in rats and chicks. Atherosclerosis 1980; 35: 439–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mosley ST, Kalinowski SS, Schafer BL, Tanaka RD. Tissue‐selective acute effects of inhibitors of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase on cholesterol biosynthesis in lens. J Lipid Res 1989; 30: 1411–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bensch WR, Ingebritsen TS, Diller ER. Lack of correlation between the rate of cholesterol biosynthesis and the activity of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylgutaryl coenzyme a reductase in rats and in fibroblasts treated with ML‐236B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1978; 82: 247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Endo A, Tsujita Y, Kuroda M, Tanzawa K. Inhibition of cholesterol synthesis in vitro and in vivo by ML‐236A and ML‐236B, competitive inhibitors of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme a reductase. Eur J Biochem 1977; 77: 31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ginsberg HN, Le NA, Short MP, Ramakrishnan R, Desnick RJ. Suppression of apolipoprotein B production during treatment of cholesteryl ester storage disease with lovastatin. Implications for regulation of apolipoprotein B synthesis. J Clin Invest 1987; 80: 1692–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grundy SM. Consensus statement: role of therapy with “statins” in patients with hypertriglyceridemia. Am J Cardiol 1998; 81: 1B–6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Isley WL, Harris WS, Miles JM. The effect of high‐dose simvastatin on free fatty acid metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 2006; 55: 758–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rise P, Pazzucconi F, Sirtori CR, Galli C. Statins enhance arachidonic acid synthesis in hypercholesterolemic patients. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2001; 11: 88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.0.2. London: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive meta‐analysis version 2. Englewood, NJ, USA: Biostat; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005; 5: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F. Methods for meta‐analysis in medical research, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sahebkar A, Serban MC, Mikhailidis DP, Toth PP, Muntner P, Ursoniu S, Mosterou S, Glasser S, Martin SS, Jones SR, Rizzo M, Rysz J, Sniderman AD, Pencina MJ, Banach M. Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta‐analysis Collaboration (LBPMC) Group. Head‐to‐head comparison of statins versus fibrates in reducing plasma fibrinogen concentrations: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Pharmacol Res. 2015; 103: 236–52. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sahebkar A. Are curcuminoids effective C‐reactive protein‐lowering agents in clinical practice? Evidence from a meta‐analysis. Phytother Res 2014; 28: 633–42. doi:10.1002/ptr.5045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ferretti G, Bacchetti T, Sahebkar A. Effect of statin therapy on paraoxonase‐1 status: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of 25 clinical trials. Prog Lipid Res 2015; 60: 50–73. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel‐plot‐based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta‐analysis. Biometrics 2000; 56: 455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huptas S, Geiss HC, Otto C, Parhofer KG. Effect of atorvastatin (10 mg/day) on glucose metabolism in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2006; 98: 66–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Diabetes Atorvastin Lipid Intervention (DALI) Study Group . The effect of aggressive versus standard lipid lowering by atorvastatin on diabetic dyslipidemia: the DALI study: a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 1335‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bays HE, Schwartz S, Littlejohn T 3rd, Kerzner B, Krauss RM, Karpf DB, Choi YJ, Wang X, Naim S, Roberts BK. MBX‐8025, a novel peroxisome proliferator receptor‐delta agonist: lipid and other metabolic effects in dyslipidemic overweight patients treated with and without atorvastatin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 2889–97. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Plat J, Brufau G, Dallinga‐Thie GM, Dasselaar M, Mensink RP. A plant stanol yogurt drink alone or combined with a low‐dose statin lowers serum triacylglycerol and non‐HDL cholesterol in metabolic syndrome patients. J Nutr 2009; 139: 1143–9. doi:10.3945/jn.108.103481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mitropoulos KA, Armitage JM, Collins R, Meade TW, Reeves BE, Wallendszus KR, Wilson SS, Lawson A, Peto R. Randomized placebo‐controlled study of the effects of simvastatin on haemostatic variables, lipoproteins and free fatty acids. The Oxford Cholesterol Study Group. Eur Heart J 1997; 18: 235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Paolisso G, Sgambato S, De Riu S, Gambardella A, Verza M, Varricchio M, D'Onofrio F. Simvastatin reduces plasma lipid levels and improves insulin action in elderly, non‐insulin dependent diabetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1991; 40: 27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Krysiak R, Zmuda W, Okopien B. The effect of simvastatin‐ezetimibe combination therapy on adipose tissue hormones and systemic inflammation in patients with isolated hypercholesterolemia. Cardiovasc Ther 2014; 32: 40–6. doi:10.1111/1755-5922.12057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Krysiak R, Zmuda W, Okopień B. The effect of short‐term simvastatin treatment on plasma adipokine levels in patients with isolated hypercholesterolemia: a preliminary report. Pharmacol Rep 2014; 66: 880–4. doi:10.1016/j.pharep.2014.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Szendroedi J, Anderwald C, Krssak M, Bayerle‐Eder M, Esterbauer H, Pfeiler G, Brehm A, Nowotny P, Hofer A, Waldhäusl W, Roden M. Effects of high‐dose simvastatin therapy on glucose metabolism and ectopic lipid deposition in nonobese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 209–14. doi:10.2337/dc08-1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Osborne TF, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. 5′ end of HMG CoA reductase gene contains sequences responsible for cholesterol‐mediated inhibition of transcription. Cell 1985; 42: 203–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nakanishi M, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Multivalent control of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase. Mevalonate‐derived product inhibits translation of mRNA and accelerates degradation of enzyme. J Biol Chem 1988; 263: 8929–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hardie DG, Carling D, Sim ATR. The AMP‐activated protein kinase—a multisubstrate regulator of lipid metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci 1989; 14: 20–3. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Williams ML, Menon GK, Hanley KP. HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors perturb fatty acid metabolism and induce peroxisomes in keratinocytes. J Lipid Res 1992; 33: 193–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jasińska M, Owczarek J, Orszulak‐Michalak D. Statins: a new insight into their mechanisms of action and consequent pleiotropic effects. Pharmacol Rep 2007; 59: 483–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kliewer SA, Sundseth SS, Jones SA, Brown PJ, Wisely GB, Koble CS, Devchand P, Wahli W, Willson TM, Lenhard JM, Lehmann JM. Fatty acids and eicosanoids regulate gene expression through direct interactions with peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptors alpha and gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94: 4318–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Staels B, Dallongeville J, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K, Leitersdorf E, Fruchart JC. Mechanism of action of fibrates on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Circulation 1998; 98: 2088–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jula A, Marniemi J, Rönnemaa T, Virtanen A, Huupponen R. Effects of diet and simvastatin on fatty acid composition in hypercholesterolemic men: a randomized controlled trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005; 25: 1952–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Roglans N, Sanguino E, Peris C, Alegret M, Vázquez M, Adzet T, Díaz C, Hernández G, Laguna JC, Sánchez RM. Atorvastatin treatment induced peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor alpha expression and decreased plasma nonesterified fatty acids and liver triglyceride in fructose‐fed rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 302: 232–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, Seshasai SR, McMurray JJ, Freeman DJ, Jukema JW, Macfarlane PW, Packard CJ, Stott DJ, Westendorp RG, Shepherd J, Davis BR, Pressel SL, Marchioli R, Marfisi RM, Maggioni AP, Tavazzi L, Tognoni G, Kjekshus J, Pedersen TR, Cook TJ, Gotto AM, Clearfield MB, Downs JR, Nakamura H, Ohashi Y, Mizuno K, Ray KK, Ford I. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta‐analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet 2010; 375: 735–42. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61965-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Park ZH, Juska A, Dyakov D, Patel RV. Statin‐associated incident diabetes: a literature review. Consult Pharm 2014; 29: 317–34. doi:10.4140/TCP.n.2014.317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Henriksbo BD, Lau TC, Cavallari JF, Denou E, Chi W, Lally JS, Crane JD, Duggan BM, Foley KP, Fullerton MD, Tarnopolsky MA, Steinberg GR, Schertzer JD. Fluvastatin causes NLRP3 inflammasome‐mediated adipose insulin resistance. Diabetes 2014; 63: 3742–7. doi:10.2337/db13-1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Boden G. Role of fatty acids in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and NIDDM. Diabetes 1997; 46: 3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kelley DE, Simoneau JA. Impaired free fatty acid utilization by skeletal muscle in non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 1994; 94: 2349–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Reaven GM, Chen YD. Role of abnormal free fatty acid metabolism in the development of non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Med 1988; 85: 106–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, Murphy SA, Ho JE, Waters DD, DeMicco DA, Barter P, Cannon CP, Sabatine MS, Braunwald E, Kastelein JJ, de Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Pedersen TR, Tikkanen MJ, Sattar N, Ray KK. Risk of incident diabetes with intensive‐dose compared with moderate‐dose statin therapy: a meta‐analysis. JAMA 2011; 305: 2556–64. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Navarese EP, Buffon A, Andreotti F, Kozinski M, Welton N, Fabiszak T, Caputo S, Grzesk G, Kubica A, Swiatkiewicz I, Sukiennik A, Kelm M, De Servi S, Kubica J. Meta‐analysis of impact of different types and doses of statins on new‐onset diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2013; 111: 1123–30. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhou Y, Yuan Y, Cai RR, Huang Y, Xia WQ, Yang Y, Wang P, Wei Q, Wang SH. Statin therapy on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: a meta‐analysis. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2013; 14: 1575–84. doi:10.1517/14656566.2013.810210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sahebkar A, Chew GT, Watts GF. Recent advances in pharmacotherapy for hypertriglyceridemia. Prog Lipid Res 2014; 56: 47–66. doi:10.1016/j.plipres.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sahebkar A, Watts GF. New LDL‐cholesterol lowering therapies: pharmacology, clinical trials, and relevance to acute coronary syndromes. Clin Ther 2013; 35: 1082–98. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Banach M, Aronow WS, Serban C, Sahabkar A, Rysz J, Voroneanu L, Covic A. Lipids, blood pressure and kidney update 2014. Pharmacol Res 2015; 95–96: 111–25. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2015.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sahebkar A, Watts GF. New therapies targeting apoB metabolism for high‐risk patients with inherited dyslipidaemias: what can the clinician expect? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2013; 27: 559–67. doi:10.1007/s10557-013-6479-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sahebkar A, Watts GF. Managing recalcitrant hypercholesterolemia in patients on current best standard of care: efficacy and safety of novel pharmacotherapies. Clin Lipidology 2014; 9: 221–33. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sahebkar A, Chew GT, Watts GF. New peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor agonists: potential treatments for atherogenic dyslipidemia and non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2014; 15: 493–503. doi:10.1517/14656566.2014.876992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sahebkar A, Watts GF. Role of selective peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor modulators in managing cardiometabolic disease: tale of a roller‐coaster. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014; 16: 780–92. doi:10.1111/dom.12277 [Google Scholar]