Abstract

Aims

LCZ696 (angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor) is a novel drug developed for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Neprilysin is one of multiple enzymes degrading amyloid‐β (Aβ). Its inhibition may increase Aβ levels. The potential exists that treatment of LCZ696, through the inhibition of neprilysin by LBQ657 (an LCZ696 metabolite), may result in accumulation of Aβ. The aim of this study was to assess the blood–brain‐barrier penetration of LBQ657 and the potential effects of LCZ696 on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of Aβ isoforms in healthy human volunteers.

Methods

In a double‐blind, randomized, parallel group, placebo‐controlled study, healthy subjects received once daily LCZ696 (400 mg, n = 21) or placebo (n = 22) for 14 days.

Results

LCZ696 had no significant effect on CSF AUEC(0,36 h) of the aggregable Aβ species 1–42 or 1–40 compared with placebo (estimated treatment ratios 0.98 [95% CI 0.73, 1.34; P = 0.919] and 1.05 [95% CI 0.82, 1.34; P = 0.702], respectively). A 42% increase in CSF AUEC(0,36 h) of soluble Aβ 1–38 was observed (estimated treatment ratio 1.42 [95% CI 1.05, 1.91; P = 0.023]). CSF levels of LBQ657 and CSF Aβ 1–42, 1–40, and 1–38 concentrations were not related (r 2 values 0.022, 0.010, and 0.008, respectively).

Conclusions

LCZ696 did not cause changes in CSF levels of aggregable Aβ isoforms (1–42 and 1–40) compared with placebo, despite achieving CSF concentrations of LBQ657 sufficient to inhibit neprilysin. The clinical relevance of the increase in soluble CSF Aβ 1–38 is currently unknown.

Keywords: amyloid‐β, CSF, heart failure, LCZ696, neprilysin

What is Already Known about this Subject

Neprilysin is one of multiple enzymes able to degrade amyloid‐β (Aβ); its inhibition may increase Aβ levels.

Aggregable Aβ isoforms are known to accumulate in Alzheimer's disease.

A theoretical and unproven potential exists that treatment with LCZ696 (angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor) may result in the accumulation of Aβ isoforms.

What this Study Adds

Once daily LCZ696 (400 mg) for 14 days does not cause changes in CSF levels of aggregable Aβ isoforms 1–42 and 1–40 compared with placebo, despite achieving CSF concentrations sufficient to inhibit neprilysin. The clinical relevance of the increase in CSF Aβ 1–38 is unknown.

Introduction

LCZ696 (sacubitril/valsartan) is the first‐in‐class angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) developed for the treatment of heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction. Oral administration of LCZ696 delivers systemic exposure to sacubitril (AHU377), which is further metabolized to LBQ657, and valsartan, providing simultaneous inhibition of neprilysin (by LBQ657) and blockade of the angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor (by valsartan) 1. The efficacy and safety of LCZ696 200 mg twice daily (n = 4187) compared with enalapril 10 mg twice daily (n = 4212) on mortality and morbidity in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction was assessed in the PARADIGM‐HF trial 2. In this trial, LCZ696 200 mg twice daily significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular (CV) death or hospitalization for HF compared with enalapril 10 mg twice daily (21.8% vs. 26.5%, respectively, hazard ratio [HR] 0.80, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.73, 0.87; P = 0.0000002), was superior to enalapril in reducing the risk of death from any cause and decreased HF symptoms and physical limitations 2. The benefits of LCZ696 in patients with HF are thought to result from the enhanced activity of protective endogenous neprilysin substrates, such as natriuretic peptides, and the simultaneous inhibition of organ injury driven by sustained activation of the renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system 3.

Amyloid‐β (Aβ) is generated in the brain through sequential cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β‐ and γ‐secretases 4. Aβ is removed from the brain by multiple processes, including transport into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and the bloodstream, and enzymatic degradation 5. In vitro and non‐clinical studies suggest that neprilysin is one of multiple enzymes involved in the proteolytic degradation of Aβ 6, 7, 8. Other proteases with Aβ‐degrading properties include insulin degrading enzyme, endothelin converting enzyme, angiotensin converting enzyme, thimet oligopeptidase and plasmin 9, 10, 11. The relative contribution of individual enzymes to the proteolytic degradation of Aβ remains unknown. The potential exists that treatment with LCZ696, through inhibition of neprilysin by LBQ657, may result in accumulation of Aβ species such as Aβ 1–42, 1–40 and 1–38. Senile plaques composed of aggregation‐prone Aβ subtypes (e.g. Aβ 1–42 and Aβ 1–40) are found in the brain of patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) 12, 13, 14. However the role of Aβ in the pathophysiology of AD is not conclusively defined 15.

The blood–brain‐barrier (BBB) penetration of LBQ657 and the potential effects of LCZ696 on CSF concentrations of Aβ isoforms were assessed in the present clinical study.

Methods

Study participants

The study enrolled healthy male and female volunteers aged 18–55 years (excluding women of child bearing potential), ≥50 kg in weight, with a body mass index (BMI) within the range of 18–30 kg m– 2. Key exclusion criteria included use of prescription drugs, herbal supplements (within 2 weeks prior to baseline) or over‐the‐counter drugs and dietary supplements (within 4 weeks prior to baseline), and a known history of angioedema. All study participants were enrolled at a single centre (PAREXEL International, California, USA).

Study design

This was a double‐blind, randomized, parallel group, placebo‐controlled study designed to investigate the effect of multiple doses of LCZ696 on CSF Aβ isoform concentrations in healthy human volunteers. The study protocol was reviewed by an independent Institutional Review Board (Aspire IRB, LLC; centre number 1001). The study was conducted in accordance with ICH‐Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written, informed consent prior to randomization.

The study consisted of an initial screening period (day −21 to day −4), a safety baseline (day −3), a pharmacodynamics (PD) baseline (day −2 to day −1), and a 2 week treatment period (days 1–14) (Supplementary Material S1). Post‐treatment PD/pharmacokinetic (PK) assessments were performed on days 14 and 15 and the study concluded with an end of study visit (day 19). Subjects were domiciled for 18 nights at the study centre and randomized 1 : 1 to either LCZ696 400 mg once daily for 14 days or matching placebo once daily for 14 days. LCZ696 was taken with water in the morning for 14 days, after an overnight fasting period (~10 h) with no food intake permitted until 1 h post‐dose.

PD assessments

The primary end point was the change from baseline 36 h area under the effect curve (AUEC(0,36 h) of Aβ 1–40 CSF concentration, with LCZ696 compared with placebo. Secondary end points included the change from baseline of AUEC(0,24 h) for CSF Aβ 1–40, and AUEC(0,36 h) and AUEC(0,24 h) for CSF Aβ 1–42 and 1–38, with LCZ696 compared with placebo. Change from baseline AUEC(0,36 h) and AUEC(0,24 h) of Aβ 1–40 plasma concentrations were measured as an exploratory assessment.

Serial CSF samples were taken from day −2 to day −1 (PD baseline) and from day 14 to day 15 from an indwelling spinal catheter inserted into the lower spinal canal by trained personnel using a standard operating procedure at time points that matched 30 min pre‐dose, and 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 and 36 h post‐dose. In each case, up to 2 ml of CSF was required to flush the tubing connected to the indwelling catheter, followed by collection of a total of 6 ml used for analysis. CSF aliquots were supplemented with 0.2% (v/v) Tween‐20 prior to storage at −70°C. CSF sample collection itself may result in an increase in CSF Aβ concentrations (placebo‐drift). As such, the study was baseline and placebo controlled and these measurements served as reference points to distinguish study drug and procedural‐related effects. In addition, a parallel group (rather than crossover) design was employed.

Blood samples were obtained by direct venipuncture or indwelling cannula inserted in a forearm vein. In total, ~4 ml of blood was collected into EDTA monovettes or EDTA vacutainers to obtain a final volume of 1.3 ml plasma. Validated, sandwich‐based multiplexed immunoassays were used to determine separately Aβ isoforms in CSF with lower limits of quantification (LLOQ) for Aβ 1–40, 1–42 and 1–38 isoforms of 126.2 pg ml‐1, 46.6 pg ml‐1 and 70.0 pg ml‐1, respectively. A validated immunoassay was used to determine Aβ 1–40 in plasma (LLOQ of 5.04 pmol l–1). Validation included the assessment of parallelism, selectivity, reproducibility and stability. Acceptance criteria (accuracy, precision) were defined for each of these assessments. The sensitivity of each method was based on the lowest concentration of the analyte in a biological sample that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision and accuracy.

PK assessments

Steady‐state PK assessments of LCZ696 analytes (sacubitril, LBQ657 and valsartan) in plasma and of LBQ657 in CSF were carried out using a validated LC‐MS/MS method. Plasma and CSF samples were collected on day 14 at 30 min pre‐dose and 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 and 36 h post‐dose. Blood samples (3 ml) were obtained by direct venipuncture or indwelling cannula inserted into a forearm vein and collected in K2EDTA‐containing polyethylene sample tubes. Tubes were immediately inverted gently and stored on ice prior to centrifugation. Centrifugation was carried out within 30 min of collection, between 2 and 8°C for 10 min at ~1500 g. Immediately thereafter, plasma was transferred to a 2 ml polypropylene sample tube and stored on dry ice. Tubes were maintained in storage conditions of ≤ − 20°C prior to analysis.

CSF samples (2 ml, as described above) were transferred into two polypropylene screw cap tubes (1 ml aliquots) without additives and placed immediately on dry ice and maintained in storage conditions of ≤ − 20°C prior to analysis. Samples were labelled with the exact times of dosing and collection. Validated, specific LC‐MS/MS methods were used to quantify sacubitril, LBQ657 and valsartan in plasma with LLOQ of 1.00 ng ml‐1, 20.0 ng ml‐1 and 10.0 ng ml‐1, respectively. The LLOQ for quantification of LBQ657 in CSF using LC‐MS/MS was 0.2 ng ml‐1.

Safety assessments

Assessments included monitoring and recording adverse events (AEs), monitoring of haematology, blood chemistry and urine, vital signs, electrocardiograms, physical condition, body weight and food intake, and physical examination at safety baseline, day 14 and day 19, including neurological examination and fundoscopy.

Statistical analyses

Forty subjects were required to ensure that 34 subjects (n = 17 per group) completed the study. The sample size was chosen to obtain less than 1 x standard deviation (SD) half‐width for the 95% CI of difference to placebo in change from baseline of AUEC(0,36 h) for CSF concentrations of Aβ 1–40.

All PD analyses were performed on subjects with more than one post‐baseline PD assessment without any significant protocol deviation (PD population). All PK analyses were performed on subjects with more than one valid PK concentration measurement, and who received study drug without any significant protocol deviation (PK population). Samples obtained from the placebo treatment group for PK analysis were assessed in order to exclude treatment mis‐randomizations but were not included in this data set. Safety analyses were performed on all subjects who received any study drug (safety population).

The primary end point was analyzed using a linear model with treatment as fixed effect and baseline AUEC as covariate, with 95% CIs presented for the treatment difference. In addition, the change from baseline in log‐scale was analyzed with treatment as a fixed effect and log‐transformed baseline value as a covariate. The 95% CI for the treatment ratio (LCZ696 400 mg vs. placebo) was computed and presented for the ratio to baseline in AUEC. Study subjects with missing post‐dose measurements for all time points on day 14 were excluded from the primary analysis. Subjects with missing post‐dose measurements for some time points on day 14 were assessed regarding the number of completed measurements for inclusion in the primary analysis. Additional supportive analyses included assessment of 24 h AUEC change from baseline in linear and log scale. Concentration–time profiles and individual AUEC (24 h and 36 h) and change from baseline data were explored graphically. Similar analyses were performed for the secondary variables (24 h and 36 h AUEC change from baseline in linear and log scale for Aβ 1–42 and 1–38 isoform concentrations in CSF) and for the exploratory assessment of Aβ 1–40 concentrations in plasma.

PK parameters of AUC(0,τ,ss), C max, C trough and t max were determined for LCZ696 analytes sacubitril, LBQ657 and valsartan in plasma and LBQ657 in CSF from concentration–time profiles using actual recorded sampling times and non‐compartmental methods (Phoenix, v6.2 or higher). PK parameters were evaluated with summary statistics. Concentrations of analytes below LLOQ were treated as zero for all PK calculations, including summary statistics, and a geometric mean was not reported if the dataset included zero values. The BBB penetration of LBQ657 was calculated by estimating the CSF : plasma exposure ratio.

For PD/PK analyses, plasma and CSF LBQ657 concentrations were plotted against plasma and CSF Aβ concentrations.

Results

Participant disposition and characteristics

Forty‐three subjects were randomized to study treatment (LCZ696, n = 21; placebo, n = 22) and 39 subjects completed the study (LCZ696, n = 20; placebo, n = 19). Four subjects discontinued due to an AE (n = 1) or protocol deviations (n = 3). A further four subjects were excluded from the PD evaluation population, two due to missing blood or CSF samples and two due to the use of medications not allowed by the study protocol. All randomized subjects were included in the safety evaluation (n = 43), 35 subjects in the PD evaluation (LCZ696, n = 17; placebo, n = 18) and 19 subjects in the PK evaluation (LCZ696, n = 19; placebo, n = 0). Baseline characteristics were generally well balanced between groups (Table 1). All subjects were male.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (all randomized patients)

| LCZ696 n = 21 | Placebo n = 22 | Total n = 43 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age, years

Mean (SD) Median Range |

|||

| 36.4 (11.3)

37.0 21–55 |

39.7 (9.7)

42.0 21–54 |

38.1 (10.5)

38.0 21–55 |

|

| Male, n (%) | 21 (100) | 22 (100) | 43 (100) |

|

Predominant race, n (%)

Caucasian Black Asian Other Native American |

|||

| 1 (52)

8 (38) 1 (5) 1 (5) 0 |

16 (73)

4 (18) 1 (5) 0 1 (5) |

27 (63)

12 (28) 2 (5) 1 (2) 1 (2) |

|

|

Ethnicity, n (%)

Other Hispanic/Latino |

|||

| 17 (81) 4 (19) | 17 (77) 5 (23) | 34 (79) 9 (21) | |

|

Height, cm

Mean (SD) Median Range |

|||

| 178.0 (8.3)

178.0 154–189 |

175.7 (6.9)

177.0 164–190 |

176.9 (7.6)

177.0 154–190 |

|

|

Weight, kg

Mean (SD) Median Range |

|||

| 85.2 (9.5)

85.1 68–103 |

79.7 (11.0)

77.8 60–94 |

82.4 (10.5)

82.5 60–103 |

|

|

BMI,

kg m

–

2

Mean (SD) Median Range |

|||

| 26.9 (2.4)

27.3 22–30 |

25.8 (3.4)

27.3 18–30 |

26.3 (2.9)

27.3 18–30 |

|

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation

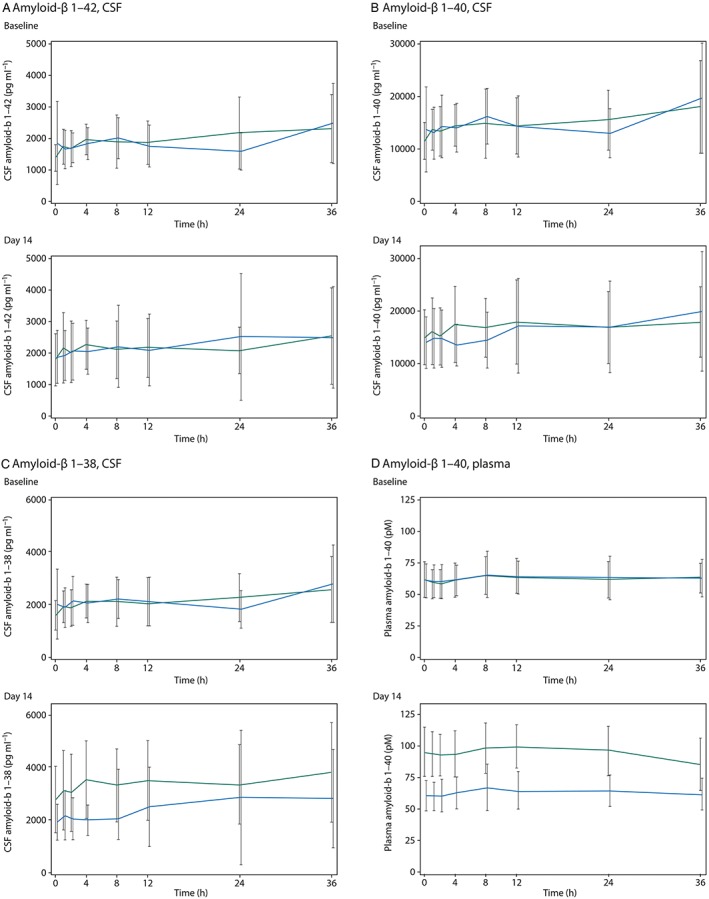

Amyloid‐β in CSF

Compared with placebo, LCZ696 treatment was not associated with a change from baseline to day 14 in CSF Aβ1–42 AUEC(0,36 h), when assessed by treatment comparison or visual inspection of the concentration time–profile (Table 2, Figure 1A). Similarly, there was no change from baseline in CSF Aβ1–40 AUEC(0,36 h) with LCZ696 compared with placebo (Table 2, Figure 1B).

Table 2.

Change from baseline of cerebrospinal fluid and plasma amyloid‐β isoforms AUEC(0,36 h) (pg ml‐1 h) on day 14 (PD analysis set)

| Absolute AUEC(0,36 h) | Adjusted mean change from baseline * AUEC(0,36 h) | Estimated treatment difference * (95% CI) | P value * | Adjusted geometric mean † | Estimated treatment ratio † (LCZ696 : placebo) | 95% CI of ratio † (LCZ696 : placebo) | P value † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Day 14 | ||||||||

| CSF | |||||||||

| Amyloid‐β 1–42 | |||||||||

| LCZ696, n = 17 | 73167.4 | 81043.7 | 9703.18 | −5754.79 (−32122.78, 20613.20) | 0.660 | 1.12 | 0.98 | 0.73, 1.34 | 0.919 |

| Placebo, n = 18 | 66702.1 | 83885.4 | 15457.97 | 1.14 | |||||

| Amyloid‐β 1–40 | |||||||||

| LCZ696, n = 17 | 551061.5 | 630561.3 | 82414.33 | 16332.96 (−135541.51, 168207.42) | 0.828 | 1.14 | 1.05 | 0.82, 1.34 | 0.702 |

| Placebo, n = 18 | 536543.5 | 605377.5 | 66081.37 | 1.09 | |||||

| Amyloid‐β 1–38 | |||||||||

| LCZ696, n = 17 | 79256.6 | 126201.7 | 47183.26 | 31549.18 (−1100.04, 64198.40) | 0.058 | 1.58 | 1.42 | 1.05, 1.91 | 0.023 |

| Placebo, n = 18 | 76621.5 | 92480.6 | 15634.09 | 1.11 | |||||

| Plasma | |||||||||

| Amyloid‐β 1–40 | |||||||||

| LCZ696, n = 17 | 2287.0 | 3430.9 | 1143.76 | 1144.05 (946.70, 1341.40) | <0.001 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.41, 1.59 | <0.001 |

| Placebo, n = 18 | 2296.9 | 2296.4 | −0.29 | 1.00 | |||||

Adjusted means (SE), 95% CIs for mean difference and P values are determined from a linear model on change from baseline AUEC with treatment as fixed effect and baseline AUEC as a continuous covariate.

The change from baseline AUEC in log scale was analyzed using a fixed effect model with treatment as fixed effect and log transformed baseline AUEC as continuous covariate.

AUEC, area under the effect curve; CI, confidence interval; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; PD, pharmacodynamic; SE, standard error

Figure 1.

Concentration of amyloid‐β isoforms by timepoint at baseline and on day 14 for LCZ696 (green lines) and placebo (blue lines) groups, (A) amyloid‐β 1–42 in cerebral spinal fluid, (B) amyloid‐β 1–40 in cerebral spinal fluid, (C) amyloid‐β 1–38 in cerebral spinal fluid and (D) amyloid‐β 1–40 in plasma

An increase was observed in CSF Aβ 1–38 concentrations in the LCZ696 group compared with placebo at day 14, and was most apparent at time points between 0 and 8 h (Figure 1C). There was a 42% increase in CSF Aβ 1–38 AUEC(0,36 h) with LCZ696 compared with placebo as assessed by the treatment ratio, a difference which reached statistical significance (P = 0.023). However, the absolute treatment difference in CSF Aβ 1–38 AUEC(0,36 h) between LCZ696 and placebo for change from baseline to day 14 was not statistically significant (P = 0.058) (Table 2).

Treatment comparisons of change from baseline of CSF Aβ isoform AUEC(0,24 h) (24 h area under the effect curve) were also analyzed (Table 3). Compared with placebo, LCZ696 was not associated with an increase from baseline to day 14 in CSF AUEC(0,24 h) for Aβ 1–42 and 1–40 isoforms. However, LCZ696 compared with placebo was associated with a statistically significant increase from baseline to day 14 in CSF AUEC(0,24 h) for Aβ 1–38 as assessed by the treatment ratio (P = 0.010) and by the absolute treatment difference between LCZ696 and placebo (P = 0.026).

Table 3.

Change from baseline of cerebrospinal fluid and plasma amyloid‐β isoforms AUEC(0,24 h) (pg ml‐1 h) on day 14 (PD analysis set)

| Absolute AUEC (0,24 h) | Adjusted mean change from baseline * AUEC(0,24 h) | Estimated treatment difference * (95% CI) | P value * | Adjusted geometric mean † | Estimated treatment ratio † (LCZ696 : Placebo) | 95% CI of ratio † (LCZ696 : placebo) | P value † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Day 14 | ||||||||

| CSF | |||||||||

| Amyloid‐β 1–42 | |||||||||

| LCZ696, n = 17 | 47289.5 | 52090.0 | 5709.89 | −4374.08 (−19372.94, 10624.79) | 0.557 | 1.11 | 0.96 | 0.73, 1.26 | 0.767 |

| Placebo, n = 18 | 42604.7 | 53547.5 | 10083.97 | 1.16 | |||||

| Amyloid‐β 1–40 | |||||||||

| LCZ696, n = 17 | 356264.3 | 412403.2 | 58593.53 | 20441.88 (−71901.30, 112785.06) | 0.655 | 1.16 | 1.07 | 0.86, 1.34 | 0.546 |

| Placebo, n = 18 | 342756.1 | 383226.1 | 38151.65 | 1.08 | |||||

| Amyloid‐β 1–38 | |||||||||

| LCZ696, n = 17 | 51304.9 | 81642.5 | 30492.92 | 21916.37 (−2767.16, 41065.58) | 0.026 | 1.58 | 1.43 | 1.10, 1.86 | 0.010 |

| Placebo, n = 18 | 49484.2 | 58207.5 | 8576.55 | 1.11 | |||||

| Plasma | |||||||||

| Amyloid‐β 1–40 | |||||||||

| LCZ696, n = 17 | 1528.9 | 2335.9 | 806.96 | 801.09 (676.15, 926.03) | <0.001 | 1.53 | 1.52 | 1.43, 1.62 | <0.001 |

| Placebo, n = 18 | 1533.4 | 1539.2 | 5.87 | 1.01 | |||||

Adjusted means (SE), 95% CIs for mean difference and P values are determined from a linear model on change from baseline AUEC with treatment as fixed effect and baseline AUEC as a continuous covariate.

The change from baseline AUEC in log scale was analyzed using a fixed effect model with treatment as fixed effect and log transformed baseline AUEC as continuous covariate.

AUEC, area under the effect curve; CI, confidence interval; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; PD, pharmacodynamic; SE, standard error

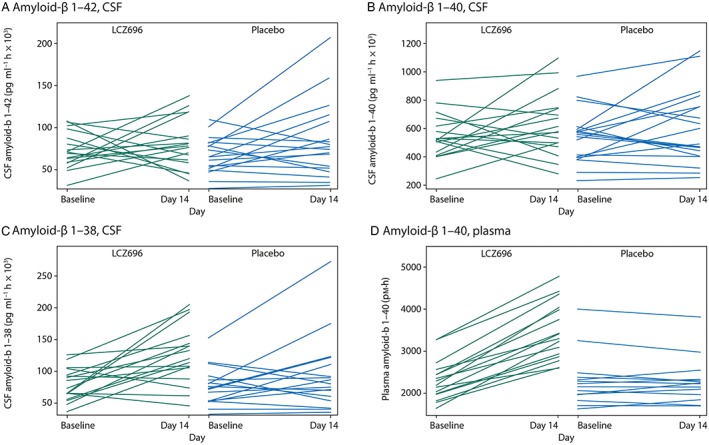

To assess trends within treatment groups, individual CSF Aβ isoform AUEC(0,36 h) and AUEC(0,24 h) values at baseline and day 14 were plotted (Figure 2 for AUEC(0,36 h)). Visual inspection did not reveal any apparent differences or unidirectional trends in Aβ 1–42 and 1–40 AUEC(0,36 h) values or group imbalances in either treatment group. The individual exhibiting the largest increase in, and highest post‐treatment value of, CSF Aβ 1–42 AUEC(0,36 h) received placebo (Figure 2A, B). Subjects in the LCZ696 group appeared to have an increase in CSF Aβ 1–38 AUEC(0,36 h) values, compared with placebo. As above, the individual exhibiting the largest increase in, and highest post‐treatment value of, CSF Aβ 1–38 AUEC(0,36 h) received placebo (Figure 2C). Individual CSF Aβ isoform AUEC(0,24 h) analyses were comparable and supportive of AUEC(0,36 h) data outlined above (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Individual subject ping‐pong plots of amyloid‐β isoform AUEC(0,36 h) at baseline and at day 14 for LCZ696 (left‐hand graph of each panel) and placebo (right‐hand graph of each panel) groups, (A) amyloid‐β 1–42 in cerebral spinal fluid, (B) amyloid‐β 1–40 in cerebral spinal fluid, (C) amyloid‐β 1–38 in cerebral spinal fluid and (D) amyloid‐β 1–40 in plasma

Amyloid‐β in plasma

The effects of LCZ696 on plasma Aβ 1–40 levels were also explored. Aβ 1–40 was selected as plasma biomarker because Aβ 1–40 plasma concentrations were expected to be higher and associated with a lower variability relative to plasma concentrations of Aβ 1–42 and Aβ 1–38. At day 14, plasma Aβ 1–40 levels were higher in the LCZ696 group compared with the placebo group at all time points (Figure 1D). Overall, there was a significant increase of 50% (P < 0.001) from baseline to day 14 in plasma Aβ 1–40 AUEC(0,36 h) with LCZ696 compared with placebo (Table 2). All subjects receiving LCZ696 had increases in plasma Aβ 1–40 AUEC(0,36 h) values from baseline to day 14 (Figure 2D). A similar observation was made for AUEC(0,24 h) (Table 3).

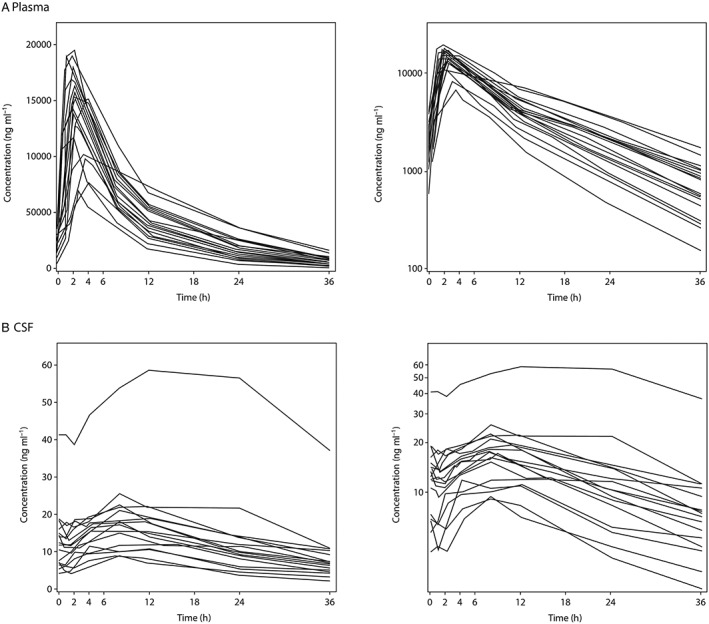

LCZ696 plasma and CSF PK

Following oral administration of LCZ696, peak concentrations (C max) of sacubitril, LBQ657 and valsartan were reached in plasma at median t max times of 1 h, 2 h and 1 h, respectively (Table 4). In contrast to steady‐state PK of LCZ696 in plasma, the concentration of LBQ657 in CSF increased slowly, reaching C max in a median t max time of 8 h (Table 4, Figure 3). At steady‐state, mean C max and trough CSF concentrations (C trough) of LBQ657 were 19.2 ng ml‐1 and 13.2 ng ml‐1, respectively. The CSF : plasma ratio of LBQ657 exposure (AUC(0,τ,ss)) was estimated to be 0.002825. Since sacubitril and valsartan do not inhibit neprilysin, CSF concentrations of these LCZ696 analytes were not measured.

Table 4.

Summary statistics for pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for LCZ696 analytes (sacubitril, LBQ657 and valsartan) (PK analysis set)

| AUC(0,τ ,ss) (ng ml‐1 h) | C max (ng ml‐1 ) | C trough * (ng ml‐1 ) | t max (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma, n | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

|

Sacubitril

Mean (SD)

CV% Mean Median Min–max |

3220 (1530)

47.5 3010 1030–7830 |

1710 (682)

39.9 1740 553–3150 |

0.412 (0.787)

191.0 0 0–2.83 |

NA

NA 1.00 1.00–4.00 |

|

LBQ657

Mean (SD)

CV% Mean Median Min–max |

137 000 (39 400)

28.7 131 000 66 800–218 000 |

14 100 (3600)

25.5 14 200 7790–19 600 |

1840 (907)

49.3 1710 455–3720 |

NA

NA 2.00 1.00–4.00 |

|

Valsartan

Mean (SD)

CV% Mean Median Min–max |

21 300 (11 200)

52.8 19 400 7940–49 500 |

3910 (2100)

53.7 3420 1030–9380 |

180 (113)

62.9 145 57.7–532 |

NA

NA 1.03 1.00–2.05 |

| CSF, n | 16† | 17‡ | 16† | 17‡ |

|

LBQ657

Mean (SD)

CV% Mean Median Min–max |

387 (261)

67.4 338 154–1290 |

19.2 (11.3)

58.9 17.9 9.09–58.8 |

13.2 (12.4)

94.0 10.2 3.93–56.6 |

NA

NA 8.00 3.98–12.0 |

For all analytes in both plasma and CSF, C trough was observed at 24 h post‐dose.

Data from three subjects were excluded due to insufficient concentration data for estimation of AUC(0,τ) and C trough.

All PK parameters from two subjects were excluded from summary statistics due to insufficient concentration data.

AUC, area under the curve; C max, maximum plasma concentration; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; C trough, trough plasma concentration; CV, coefficient of variation; NA, not available; PK, pharmacokinetic; SD, standard deviation; t max, time to maximum concentration

Figure 3.

Individual subject LBQ657 concentrations vs. time on day 14 following oral administration of LCZ696 at 400 mg once daily, (A) plasma and (B) cerebral spinal fluid. Left‐hand graph of each panel is a linear plot with an expanded time scale, right‐hand graph of each panel is a semi‐logarithmic plot

PD/PK assessment of an individual outlier

Upon assessment of steady‐state PK data, it was apparent that one subject exhibited >2‐fold higher peak CSF LBQ657 concentrations compared with all other subjects (Figure 3B). The CSF C max and C trough values for this individual were reported as 58.8 ng ml‐1 and 56.6 ng ml‐1 in comparison with the treatment group mean values of 19.2 ng ml‐1 and 13.2 ng ml‐1, respectively. However, plasma C max of LBQ657 in this subject (19 000 ng ml‐1) was within the observed variability of plasma LBQ657 C max values in the LCZ696 treatment group (Table 4). Assessment of individual Aβ isoform AUEC(0,36 h) and AUEC(0,24 h) data indicated that levels of Aβ isoforms in this subject did not increase at day 14 relative to baseline (baseline AUEC(0,36 h) (pg ml‐1 h); Aβ 1–42, 107549; Aβ 1–40, 517338; Aβ 1–38, 67382; day 14 AUEC(0,36 h) (pg ml‐1 h); Aβ 1–42, 36572; Aβ 1–40, 288260; Aβ 1–38 46409).

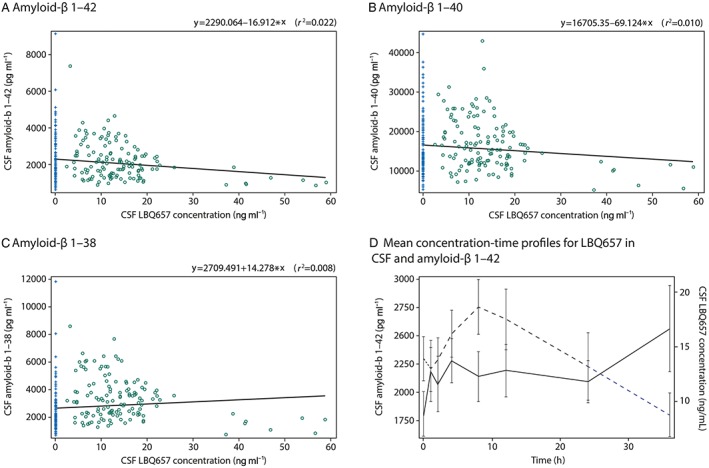

Relationship of LBQ657 and Aβ isoform concentrations

The relationship between LBQ657 levels and Aβ isoform levels was explored through analysis of scatter plots (Figure 4). The R‐square values for LBQ657 CSF concentration and CSF Aβ 1–42, 1–40, and 1–38 were 0.022, 0.010 and 0.008, respectively (Figure 4A–C). Similar results were obtained through analysis of LBQ657 CSF area under the concentration–time curve at steady‐state (AUC(0,τss)) and CSF Aβ isoform levels (data not shown). Mean concentration‐time profiles of CSF LBQ657 and Aβ 1–42 (Figure 4D) also support that there was no relationship between LBQ657 and Aβ CSF concentrations.

Figure 4.

Panels (A)–(C) show individual scatter plots of cerebral spinal fluid concentrations of amyloid‐β isoforms vs. LBQ657 concentrations on day 14 following oral administration of LCZ696 at 400 mg once daily (open circles) or placebo (plus signs), (A) amyloid‐β 1–42, (B) amyloid‐β 1–40 and (C) amyloid‐β 1–38. The solid line represents the regression (r 2). Panel (D) shows mean amyloid‐β 1–42 concentrations in cerebral spinal fluid (solid line, left y‐axis) and LBQ657 concentrations in cerebral spinal fluid (dashed lines, right y‐axis) vs. time on day 14 following oral administration of LCZ696 at 400 mg once daily

Additional analyses of LBQ657 and plasma Aβ 1–40 indicated that there was a weak relationship between LBQ657 and Aβ 1–40 plasma levels. R‐square values for the relationships between plasma LBQ657 and Aβ 1–40 concentrations and plasma LBQ657 AUC(0,τss) and Aβ 1–40 AUEC(0,36 h) were 0.293 and 0.617, respectively.

Safety and tolerability

More subjects in the LCZ696 group (n = 19) compared with the placebo group (n = 14) reported AEs related to the procedure of CSF collection (Supplementary Material S2). All AEs were of mild or moderate intensity and resolved by the end of the study (data not shown). Seven subjects reported AEs considered to be related to study treatment, two subjects receiving LCZ696 and five subjects receiving placebo. In the LCZ696 group, these were mild lightheadedness and temporomandibular joint pain. Both AEs were resolved by the study end. Two serious AEs (SAEs) were reported, one in each treatment group (post‐dural puncture headache [LCZ696] and mild sacral pain [placebo], which represented the only study discontinuations secondary to an AE).

Discussion

The key finding of this study in healthy subjects is that LCZ696 400 mg once daily did not result in changes in CSF concentrations of the aggregable Aβ isoforms 1–40 and 1–42. The lack of effect of LCZ696 was evidenced by unchanged Aβ 1–40 and 1–42 AUEC(0,36 h) and AUEC(0,24 h), and confirmed by unchanged concentration–time profiles of Aβ 1–42 and 1–40 in CSF. Individual subject AUECs at baseline and on day 14 did not reveal any obvious changes with LCZ696 compared with placebo, and there was no apparent relationship between CSF LBQ657 and CSF Aβ 1–42 and 1–40 concentrations. Despite very low BBB penetration and considering low protein binding in CSF compared with plasma, observed CSF concentrations of the neprilysin inhibitor LBQ657 were sufficient to inhibit neprilysin.

In contrast to unchanged CSF Aβ 1–42 and 1–40 levels, an increase from baseline in CSF Aβ 1–38 AUEC(0,36 h) and AUEC(0,24 h) with LCZ696 compared with placebo was observed. Concentration–time profiles of CSF Aβ 1–38 concentrations and individual subject AUECs at baseline and on day 14 were associated with considerable variability. However, there was no apparent relationship between CSF Aβ 1–38 concentrations and LBQ657 plasma and CSF concentrations. Aβ 1–38 is soluble 16, more readily transported within the brain interstitial space and into the CSF, and may be more susceptible to increase with neprilysin inhibition compared with the more hydrophobic and aggregation‐prone isoform Aβ 1–42 17, 18. In addition, neprilysin degraded monomeric Aβ 1–40 in vitro while no significant proteolysis of aggregated Aβ 1–40 was observed 19, providing support for a potential differential effect of neprilysin inhibition on aggregable vs. soluble Aβ isoforms.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no obvious or conclusive evidence in the literature showing that an isolated increase of CSF Aβ 1–38 concentrations results in or facilitates Aβ plaque formation in the brain or cognitive decline. While in vitro evidence suggests that Aβ plaque formation involves conformational conversion of Aβ oligomers 20, 21, 22, it remains unknown whether an isolated increase in CSF Aβ 1–38 may alter the propensity of other Aβ isoforms to form oligomers in vivo. However, the pattern of change in CSF concentrations of Aβ isoforms observed with LCZ696 (isolated increase in CSF Aβ 1–38) is substantially different from that observed in patients with prodromal AD and AD (decrease in CSF Aβ 1–42 23, 24, 25) or in children with Down's syndrome (increase in CSF Aβ 1–42, 1–40 and 1–38 at 54 months 26). Furthermore, Aβ 1–38 has been shown to accumulate only in brain plaques in patients with familial AD due to APP mutations within the Aβ coding region, a finding that is unrelated to neprilysin inhibition 27. Unlike Aβ 1–42 and 1–40, Aβ 1–38 was absent in parenchymal Aβ deposits in patients with sporadic AD, patients with presenilin mutations and in individuals with Down's syndrome 27, supporting that an isolated increase in CSF Aβ 1–38 is unlikely to be clinically meaningful with regards to parenchymal Aβ deposits in the brain. Furthermore, CSF Aβ 1–38 is not recommended by the Alzheimer's Biomarker Standardization Initiative as a biomarker that is neurochemically compatible with AD 28. Other neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia with Lewy bodies and Niemann–Pick disease type C, in which CSF concentrations of Aβ 1–38 are decreased or increased, respectively, are also associated with a complex change of multiple Aβ isoforms 29, 30, again suggesting that an isolated increase in CSF Aβ 1–38 without concomitant changes in other CSF Aβ isoforms is unlikely to be clinically important.

Administration of LCZ696 was associated with an increase in plasma Aβ 1–40 concentrations. While more than 30 structurally unrelated precursor proteins with a propensity to form amyloid fibrils were identified in various forms of amyloidosis, plasma Aβ has not been implicated in the pathophysiology of diseases involving systemic or organ‐specific amyloidosis outside the CNS 31, 32, and results from studies investigating the utility of plasma Aβ levels to predict cognitive decline are inconsistent. While baseline plasma Aβ 1–42 levels were decreased in patients who transitioned to cognitive decline 33, baseline plasma Aβ levels were not related to cognitive decline in studies in patients with mild cognitive impairment and AD 34. Notably, there was a decrease in plasma Aβ in apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 carriers with mild cognitive impairment, which is considered a risk factor for cognitive decline, and an increase in plasma Aβ in patients with AD following treatment with simvastatin. While non‐clinical and clinical results were inconsistent with regards to AD prevention by statins, there was no evidence for statins facilitating cognitive decline 35. Therefore, the observed increase in plasma Aβ 1–40 with LCZ696 is not considered to be clinically relevant but to reflect a PD change related to neprilysin inhibition.

The results of this study suggest that disposition pathways or enzymes other than neprilysin may be more important in the clearance of CSF Aβ in humans 10. This conclusion is supported by the observation that multiple other enzymes are implicated in Aβ degradation 10. Since the role of Aβ in the pathophysiology of AD is still not well defined 15, CSF and plasma Aβ measured in this study are considered to be a biomarker of target engagement reflecting neprilysin inhibition and not a surrogate biomarker to predict the development of Aβ plaques in the brain, cognitive decline or AD. However, human genetic data support the lack of a relationship between neprilysin and AD. A large meta‐analysis of human genome‐wide association studies in 74046 individuals did not reveal any association between variations in the neprilysin gene (membrane metallo‐endopeptidase [MME]) and AD 36. The lack of any such association supports the conclusion that common MME genetic variations are unlikely to be a clinically meaningful risk factor for AD in humans. Moreover, no obvious neurocognitive deficit has been reported for human carriers of MME loss of function mutations 37. This is consistent with the finding of this study demonstrating that LCZ696 did not affect CSF concentrations of the Aβ isoforms 1–42 and 1–40, which are poorly soluble, rapidly aggregate and the main component of Aβ plaques in the brain and therefore considered to have the greatest amyloidogenic properties 15, 38, 39.

Whilst the results of this study are reassuring, it should be noted that healthy subjects were enrolled rather than patients with HF, the target patient population of LCZ696, due to the need for serial CSF collections and to reduce confounding factors related to concomitant diseases and medications that may have impacted study results. However, LBQ657 CSF concentrations achieved in healthy subjects were sufficient to inhibit neprilysin, enabling the study of clinically relevant doses of LCZ696 on Aβ levels. It cannot be excluded that the turnover of CSF Aβ in patients with prodromal or manifest AD is different from the turnover of CSF Aβ in healthy subjects. However pre‐existing reductions in Aβ 1–42 and 1–40 CSF levels would have been likely to confound the interpretation of study results in this specific patient population. Therefore, the selection of healthy subjects to investigate the PDeffect of neprilysin inhibition on CSF Aβ levels is considered appropriate.

The treatment duration (2 weeks) was considered sufficient to ensure plasma PK steady‐state, allowing for equilibrium between CSF and plasma LBQ657 concentrations and providing a sufficient time window between CSF collection periods to avoid procedure‐related increases in CSF Aβ (placebo‐drift). Extrapolation of the study results following 2 weeks of dosing to long term administration of LCZ696 is relevant because of the intended chronic use of LCZ696. It could be hypothesized that alternative proteolytic pathways are activated with continued dosing of LCZ696 that compensate for neprilysin inhibition. It is therefore proposed that 2 weeks of dosing with LCZ696 may reflect or overestimate changes in CSF Aβ following chronic dosing. However, this has yet to be elucidated.

The results from the present study demonstrate that administration of LCZ696 400 mg once daily for 14 days in healthy subjects does not cause changes in CSF Aβ 1–42 and 1–40 concentrations. The clinical relevance of the associated increase in CSF Aβ 1–38 is unknown.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author). SJ reports grants from Novartis Pharma AG, during the conduct of the study, HG and SJ were employees of PAREXEL International at the time the study was conducted and hold or were eligible to receive PAREXEL stocks. THL, CT, SA, PP, MAV, MH and IR were Novartis employees at the time the study was conducted and hold or were eligible to receive Novartis stocks.

Author contributions

THL and IR conceptualized this study. All authors contributed to the development of study design and clinical study protocol. THL, CT, HG and SJ contributed to the conduct of the study; HG was the study investigator. MAV led the analysis of Aβ in CSF and plasma samples. SA conducted the PK analysis. PP conducted all statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the reporting of study results and writing of the manuscript.

The study was conducted at PAREXEL International, Glendale, CA, USA. CSF Aβ samples were analyzed at SGS Cephac, France. CSF and plasma PK samples were analyzed at Wuxi, China. The authors were assisted in the preparation of the manuscript by Derek Lavery, a professional medical writer contracted to CircleScience, an Ashfield company (part of UDG Healthcare plc). Writing support was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland .

Supporting information

Figure S1 Design of a double‐blind, randomized, parallel group, placebo‐controlled study to investigate the effect of multiple doses of LCZ696 on cerebral spinal fluid amyloid‐β isoform concentrations in healthy human subjects. Male subjects received either LCZ696 at 400 mg once daily (n = 21) or placebo (n = 22) for 14 days. PD, pharmacodynamic (cerebral spinal fluid concentrations of amyloid‐β 1–42, 1–40 and 1–38 and plasma concentrations of amyloid‐β 1–40). PK, pharmacokinetic (assessment of LCZ696 analytes [sacubitril, LBQ657 and valsartan] in plasma and of LBQ657 in cerebral spinal fluid). EOS, end of study.

Table S1 Adverse events, serious adverse events, discontinuations and deaths (safety population).

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Langenickel, T. H. , Tsubouchi, C. , Ayalasomayajula, S. , Pal, P. , Valentin, M.‐A. , Hinder, M. , Jhee, S. , Gevorkyan, H. , and Rajman, I. (2016) The effect of LCZ696 (sacubitril/valsartan) on amyloid‐β concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 81: 878–890. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12861.

References

- 1. Langenickel TH, Dole WP. Angiotensin receptor‐neprilysin inhbition with LCZ696: a novel approach for the treatment of heart failure. Drug Discov Today: Therap Strateg 2012; 9: e131–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2. McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR. Angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vardeny O, Miller R, Solomon SD. Combined neprilysin and renin‐angiotensin system inhibition for the treatment of heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2014; 2: 663–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haass C, Kaether C, Thinakaran G, Sisodia S. Trafficking and proteolytic processing of APP. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2: a006270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saido T, Leissring MA. Proteolytic degradation of amyloid β‐protein. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2: a006379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Howell S, Nalbantoglu J, Crine P. Neutral endopeptidase can hydrolyze β‐amyloid(1–40) but shows no effect on β‐amyloid precursor protein metabolism. Peptides 1995; 16: 647–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Takaki Y, Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Taniguchi S, Toyoshima S, Lu B, Gerard NP, Gerard C, Lee HJ, Shirotani K, Saido TC. Biochemical identification of the neutral endopeptidase family member responsible for the catabolism of amyloid β peptide in the brain. J Biochem 2000; 128: 897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Watanabe K, Sekiguchi M, Hosoki E, Kawashima‐Morishima M, Lee HJ, Hama E, Sekine‐Aizawa Y, Saido TC. Identification of the major Aβ1‐42‐degrading catabolic pathway in brain parenchyma: suppression leads to biochemical and pathological deposition. Nat Med 2000; 6: 143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carson JA, Turner AJ. β‐amyloid catabolism: roles for neprilysin (NEP) and other metallopeptidases? J Neurochem 2002; 81: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang DS, Dickson DW, Malter JS. β‐Amyloid degradation and Alzheimer's disease. J Biomed Biotechnol 2006; 2006: 58406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baranello RJ, Bharani KL, Padmaraju V, Chopra N, Lahiri DK, Greig NH, Pappolla MA, Sambamurti K. Amyloid‐beta protein clearance and degradation (ABCD) pathways and their role in Alzheimer's disease . Curr Alzheimer Res 2015; 12: 32–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Glenner GG, Wong CW, Quaranta V, Eanes ED. The amyloid deposits in Alzheimer's disease: their nature and pathogenesis. Appl Pathol 1984; 2: 357–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in senile plaques with end‐specific Aβ monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ42(43). Neuron 1994; 13: 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iwatsubo T, Mann DM, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Ihara Y. Amyloid beta protein (Aβ) deposition: Aβ42(43) precedes Aβ40 in down syndrome. Ann Neurol 1995; 37: 294–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sorrentino P, Iuliano A, Polverino A, Jacini F, Sorrentino G. The dark sides of amyloid in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. FEBS Lett 2014; 588: 641–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jarrett JT, Berger EP, Lansbury PT Jr The C‐terminus of the β protein is critical in amyloidogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1993; 695: 144–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gaudoux F, Boileau G, Crine P. Localization of neprilysin (EC 3.4.24.11) mRNA in rat brain by in situ hybridization. J Neurosci Res 1993; 34: 426–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ji Y, Permanne B, Sigurdsson EM, Holtzman DM, Wisniewski T. Amyloid beta40/42 clearance across the blood–brain barrier following intra‐ventricular injections in wild‐type, apoE knock‐out and human apoE3 or E4 expressing transgenic mice. J Alzheimers Dis 2001; 3: 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Betts V, Leissring MA, Dolios G, Wang R, Selkoe DJ, Walsh DM. Aggregation and catabolism of disease‐associated intra‐Aβ mutations: reduced proteolysis of AβA21G by neprilysin. Neurobiol Dis 2008; 31: 442–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee J, Culyba EK, Powers ET, Kelly JW. Amyloid‐β forms fibrils by nucleated conformational conversion of oligomers. Nat Chem Biol 2011; 7: 602–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Benilova I, Karran E, De SB. The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer's disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nat Neurosci 2012; 15: 349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vandersteen A, Masman MF, De BG, Jonckheere W, van der Werf K, Marrink SJ, Rozenski J, Benilova I, De SB, Subramaniam V, Schymkowitz J, Rousseau F, Broersen K. Molecular plasticity regulates oligomerization and cytotoxicity of the multipeptide‐length amyloid‐β peptide pool. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 36732–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fagan AM, Xiong C, Jasielec MS, Bateman RJ, Goate AM, Benzinger TL, Ghetti B, Martins RN, Masters CL, Mayeux R, Ringman JM, Rossor MN, Salloway S, Schofield PR, Sperling RA, Marcus D, Cairns NJ, Buckles VD, Ladenson JH, Morris JC. Longitudinal change in CSF biomarkers in autosomal‐dominant Alzheimer's disease . Sci Transl Med 2014; 6: 226ra30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosen C, Hansson O, Blennow K, Zetterberg H. Fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease ‐ current concepts. Mol Neurodegener 2013; 8: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Buchhave P, Minthon L, Zetterberg H, Wallin AK, Blennow K, Hansson O. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of β‐amyloid 1–42, but not of tau, are fully changed already 5 to 10 years before the onset of Alzheimer dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69: 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Englund H, Anneren G, Gustafsson J, Wester U, Wiltfang J, Lannfelt L, Blennow K, Hoglund K. Increase in β‐amyloid levels in cerebrospinal fluid of children with down syndrome. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2007; 24: 369–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moro ML, Giaccone G, Lombardi R, Indaco A, Uggetti A, Morbin M, Saccucci S, Di FG, Catania M, Walsh DM, Demarchi A, Rozemuller A, Bogdanovic N, Bugiani O, Ghetti B, Tagliavini F. APP mutations in the Aβ coding region are associated with abundant cerebral deposition of Aβ38. Acta Neuropathol 2012; 124: 809–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, Dubois B, Engelborghs S, Lewczuk P, Perret‐Liaudet A, Teunissen CE, Parnetti L. The clinical use of cerebrospinal fluid biomarker testing for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis: a consensus paper from the Alzheimer's Biomarkers Standardization Initiative. Alzheimers Dement 2014; 10: 808–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mulugeta E, Londos E, Ballard C, Alves G, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Skogseth R, Minthon L, Aarsland D. CSF amyloid β38 as a novel diagnostic marker for dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011; 82: 160–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Bianconi S, Yanjanin NM, Fu R, Mansson JE, Porter FD, Blennow K. γ‐secretase‐dependent amyloid‐β is increased in Niemann‐Pick type C: a cross‐sectional study. Neurology 2011; 76: 366–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dobson CM. The structural basis of protein folding and its links with human disease. Philos Trans R Soc Lond. B Biol Sci 2001; 356: 133–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dobson CM. Protein aggregation and its consequences for human disease. Protein Pept Lett 2006; 13: 219–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rembach A, Watt AD, Wilson WJ, Villemagne VL, Burnham SC, Ellis KA, Maruff P, Ames D, Rowe CC, Macaulay SL, Bush AI, Martins RN, Masters CL, Doecke JD. Plasma amyloid‐β levels are significantly associated with a transition toward Alzheimer's disease as measured by cognitive decline and change in neocortical amyloid burden. J Alzheimers Dis 2014; 40: 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Donohue MC, Moghadam SH, Roe AD, Sun CK, Edland SD, Thomas RG, Petersen RC, Sano M, Galasko D, Aisen PS, Rissman RA. Longitudinal plasma amyloid β in Alzheimer's disease clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement 2014; ; Oct 6:pii: S1552‐5260(14)02769‐1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, Malouf R, Passmore P. Statins for the treatment of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 7: CD007514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lambert JC, Ibrahim‐Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, DeStafano AL, Bis JC, Beecham GW, Grenier‐Boley B, Russo G, Thorton‐Wells TA, Jones N, Smith AV, Chouraki V, Thomas C, Ikram MA, Zelenika D, Vardarajan BN, Kamatani Y. Meta‐analysis of 74046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer's disease . Nat Genet 2013; 45: 1452–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Debiec H, Nauta J, Coulet F, van der Burg M, Guigonis V, Schurmans T, de Heer E, Soubrier F, Janssen F, Ronco P. Role of truncating mutations in MME gene in fetomaternal alloimmunisation and antenatal glomerulopathies. Lancet 2004; 364: 1252–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Miller DL, Papayannopoulos IA, Styles J, Bobin SA, Lin YY, Biemann K, Iqbal K. Peptide compositions of the cerebrovascular and senile plaque core amyloid deposits of Alzheimer's disease . Arch Biochem Biophys 1993; 301: 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Potter R, Patterson BW, Elbert DL, Ovod V, Kasten T, Sigurdson W, Mawuenyega K, Blazey T, Goate A, Chott R, Yarasheski KE, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Benzinger TL, Bateman RJ. Increased in vivo amyloid‐β42 production, exchange, and loss in presenilin mutation carriers. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5: 189ra77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Design of a double‐blind, randomized, parallel group, placebo‐controlled study to investigate the effect of multiple doses of LCZ696 on cerebral spinal fluid amyloid‐β isoform concentrations in healthy human subjects. Male subjects received either LCZ696 at 400 mg once daily (n = 21) or placebo (n = 22) for 14 days. PD, pharmacodynamic (cerebral spinal fluid concentrations of amyloid‐β 1–42, 1–40 and 1–38 and plasma concentrations of amyloid‐β 1–40). PK, pharmacokinetic (assessment of LCZ696 analytes [sacubitril, LBQ657 and valsartan] in plasma and of LBQ657 in cerebral spinal fluid). EOS, end of study.

Table S1 Adverse events, serious adverse events, discontinuations and deaths (safety population).

Supporting info item

Supporting info item