Abstract

Anti-VEGF therapy is a clinically validated treatment for age-related macular degeneration (AMD). We have recently reported the discovery of oral VEGFR-2 inhibitors that are selectively distributed to the ocular tissues. Herein we report a further development of those compounds and in particular the validation of the hypothesis that aminoheterocycles such as aminoisoxazoles and aminopyrazoles could also function as effective “hinge” binding moieties leading to a new class of KDR (kinase insert domain containing receptor) inhibitors.

Keywords: Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, VEGF, KDR, hinge binding, scaffold morphing, amino heterocycles

The current approved therapies for the treatment of wet or neovascular AMD are the anti-VEGF-A antibody ranibizumab, the anti-VEGF-A aptamer pegaptanib, and the anti-VEGF-A trap fusion protein aflibercept. Each of these wet-AMD treatments must be delivered by intravitreal injections and 60 percent of patients do not experience a clinically significant gain of visual acuity (≥15 letters).1 In an attempt to provide an alternative wet-AMD treatment paradigm, we have invested in the development of oral inhibitors of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) VEGFR-2 (KDR, Flt-1).2,3

The role of VEGF-A in the regulation of angiogenesis is well established. Although new vessel growth and maturation are highly complex processes requiring the sequential activation of a series of receptors by numerous ligands, VEGF-A signaling often represents a critical rate-limiting step.4 VEGF-A promotes growth of vascular endothelial cells and is also known to induce vascular leakage.5 Ocular VEGF-A levels are increased in neovascular diseases of the retina such as neovascular AMD.6,7

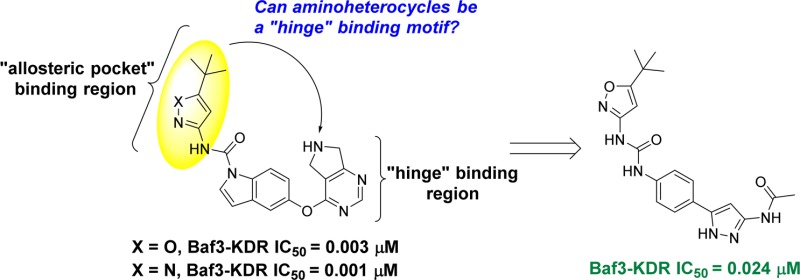

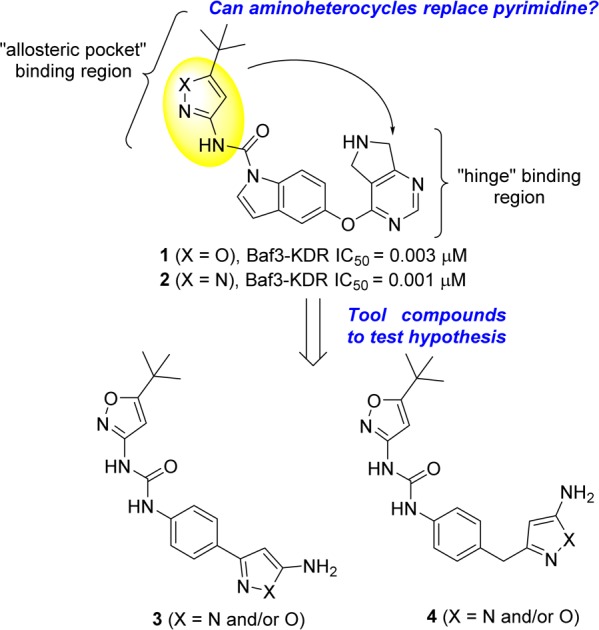

VEGF-A binds to two related receptor tyrosine kinases, VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, both of which have an extracellular domain consisting of seven immunoglobulin-like domains, a single transmembrane region and a consensus tyrosine kinase sequence that is interrupted by a kinase-insert domain.8 Upon VEGF-A binding, VEGFR-2 undergoes dimerization and ligand-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation in intact cells, resulting in a mitogenic, chemotactic, and survival signal.9 Crystal structures of VEGFR-2 with and without inhibitors, exemplify not only diversity in binding modes in DFG-in and DFG-out forms of the kinase catalytic site10 but also dependency on juxtamembrane domain conformations.11 Several chemical classes of VEGFR-2 inhibitors have been reported for oncology indications and some of them have been investigated in wet AMD.12−14 Structural similarity of our indole carboxamide series2 to phenyl ureas15 led us to hypothesize that compounds like 1 and 2 (Figure 1) bind in the DFG-out conformation of VEGFR-2, (confirmed subsequently by X-ray, unpublished data). Introduction of the polar amino-heterocycles (in place of the more classical meta-CF3 aniline) on our VEGFR-2 inhibitors provided a marked improvement in solubility, PK properties, and VEGFR-2 potency.2 These findings, together with the established role of heterocycles as “hinge binding” motifs in KDR literature,16,17 inspired us to use this moiety to replace the pyrimidine “hinge” binding motif in our established series of inhibitors (1, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothesis and design of new VEGFR-2 inhibitors bearing a new “hinge” binding moiety starting from established inhibitors.2,3

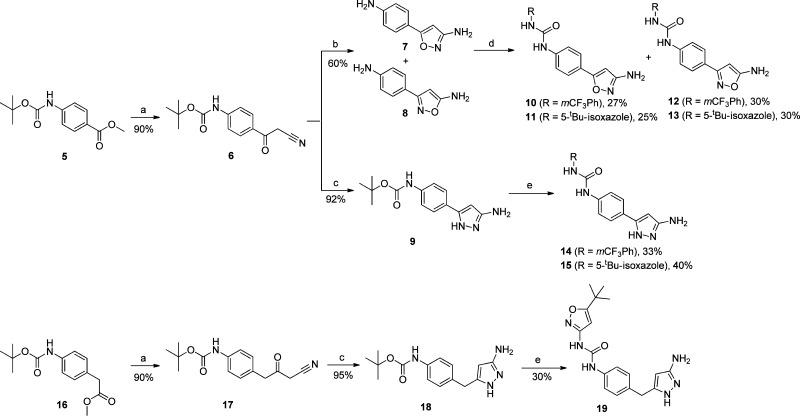

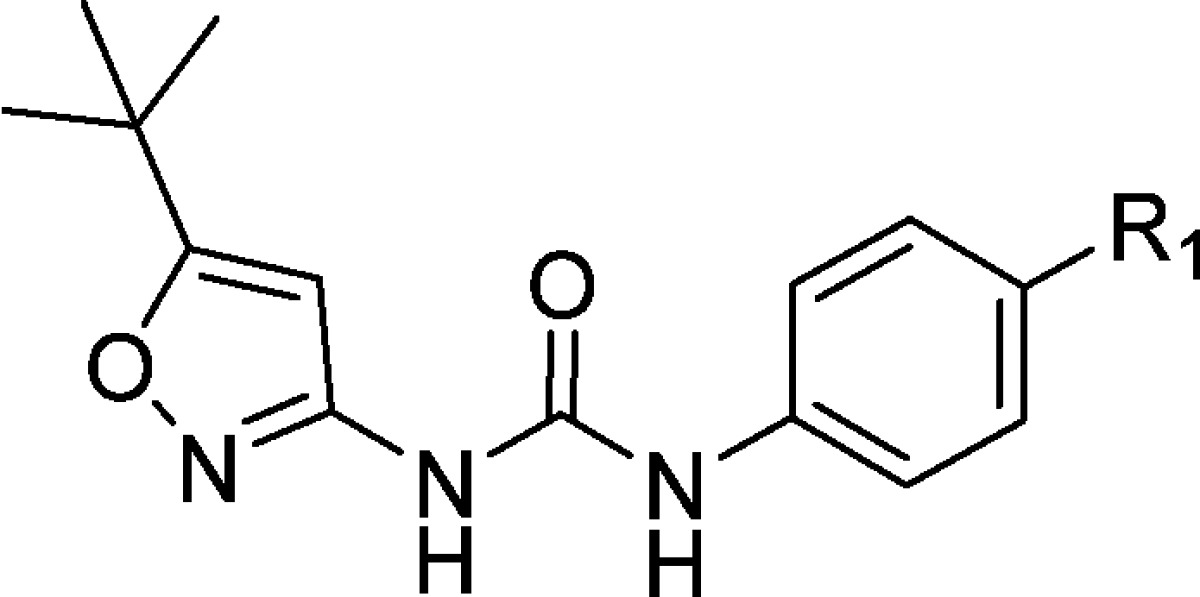

Replacing the pyrimidine in 1 (Figure 1) with the aminoheterocycle of choice (pyrazole or isoxazole) was envisioned in two ways: either directly attached to the core (3, in Figure 1) or with a methylene linker (4 in Figure 1) to more closely mimic the ether linker in inhibitor 1 (Figure 1). In addition, the indole core was simplified to aniline given that previously established SAR in that region allowed for such modification to be tolerated.11 The synthesis of the newly designed compounds outlined in Figure 1 started with the commercially available Boc protected anilines 5 and 16 (Scheme 1). Transformation of the ester to the nitriles 6 and 17 (precursors to the aminoheterocycle formation) was accomplished using established chemistry.2 Reaction of nitrile 6 with hydroxylamine sulfate and sodium hydroxide in EtOH, followed by reaction of the mixture with hydrochloric acid, furnished both the 3-amino and 5-aminoisoxazoles 7 and 8 (respectively) as a 50/50 mixture with the loss of the protecting group.18,19 Reaction of nitriles 6 and 17 with hydrazine in MeOH gave the expected aminopyrazoles 9 and 18.20 In the case of aminoisoxazoles 7 and 8 simple urea formation of the anilines with either isocyanate or phenyl carbamates efficiently produced the wanted ureas 10–13 (see Supporting Information for separation conditions to isolate the single isomers). In the case of the aminopyrazoles 9 and 18, a temporary protection of the aminopyrazole moiety (as a benzylcarbamate) was needed in order to efficiently couple the aniline (after Boc deprotection) with the isocyanates or phenyl carbamates to get the desired ureas 14, 15, and 19 (Scheme 1). Acylation of the free aminoisoxazole 13 with cyclopropanecarbonyl chloride and pyridine easily furnished the wanted inhibitor 20 (Scheme 2). For aminopyrazole containing compounds, acylation of the NH2, required a protection of the more reactive ring nitrogen (as a benzylacarbamate), followed by acylation of the amine with electrophiles. This was followed by deprotection of the aniline to enable urea formation with the carbamate. In vitro inhibition of VEGFR-2 receptor tyrosine kinase was assessed with two primary assays; a KDR receptor tyrosine kinase biochemical assay and a cellular assay with BaF3-Tel-KDR cells that are engineered to constitutively require VEGFR-2 kinase domain activity for survival and proliferation.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Sequence to Access Compounds Bearing New Hinge Binding Moiety.

Reagents and conditions: (a) LDA (3.3 equiv), CH3CN (3 equiv), THF, −78 °C to rt; (b) hydroxylamine sulfate (1.1 equiv), NaOH (1.15 equiv), EtOH, 80 °C, then HCl (1.5 equiv); (c) hydrazine (2 equiv), MeOH, 80 °C; (d) 1-isocyanato-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzene (1.5 equiv), THF, 0 °C for 10 and 12; phenyl (5-tert-butyl)isoxazol-3-yl)carbamate2 (3 equiv), DMF, 70 °C for 11 and 13; (e) 2,6-lutidine (2 equiv), benzyl carbonochloridate (1.5 equiv), DCM, 0 °C, then TFA/DCM, then 2,6-lutidine (4 equiv), 1-isocyanato-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzene (1.1 equiv), THF, 0 °C for 14; 2,6-lutidine (2 equiv), benzyl carbonochloridate (1.5 equiv), DCM, 0 °C, then TFA/DCM, then 2,6-lutidine (4 equiv), phenyl (5-tert-butyl)isoxazol-3-yl)carbamate2 (1.5 equiv), DMF, 70 °C for 15 and 19.

Scheme 2. Acylation of Compounds 13 and 15 to Expand SAR in the Hinge Binding Region.

Reagents and conditions: (f) pyridine (2 equiv), cyclopropanecarbonyl chloride (1.5 equiv), THF, 0 °C; (g) 2,6-lutidine (2 equiv), benzyl carbonochloridate (1.5 equiv), DCM, 0 °C, then 2,6-lutidine (2 equiv), cyclopropanecarbonyl (for 21) [pyvaloyl chloride for 22, acetyl chloride for 23], DCM, rt then TFA/DCM, then 2,6-lutidine (4 equiv), phenyl (5-tert-butyl)isoxazol-3-yl)carbamate2 (1.5 equiv), DMF, 70 °C.

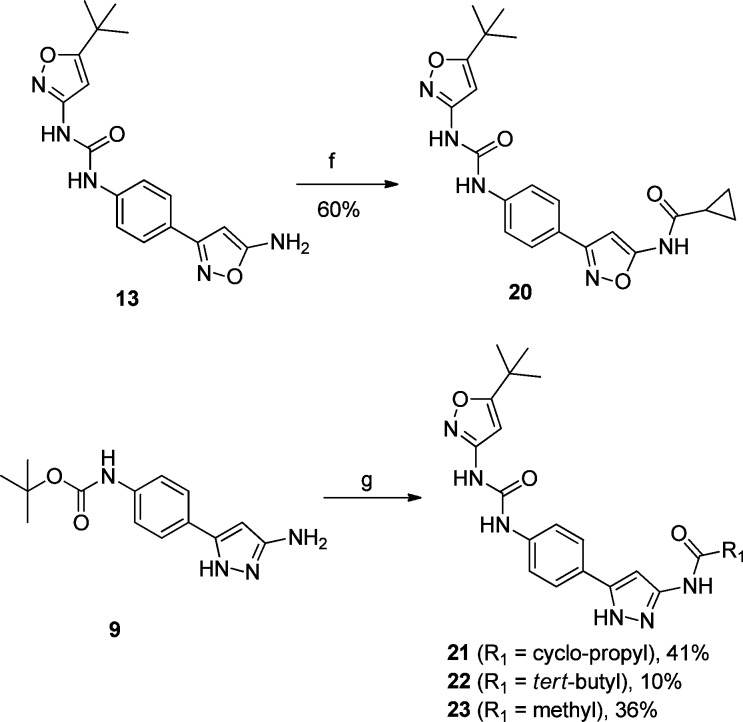

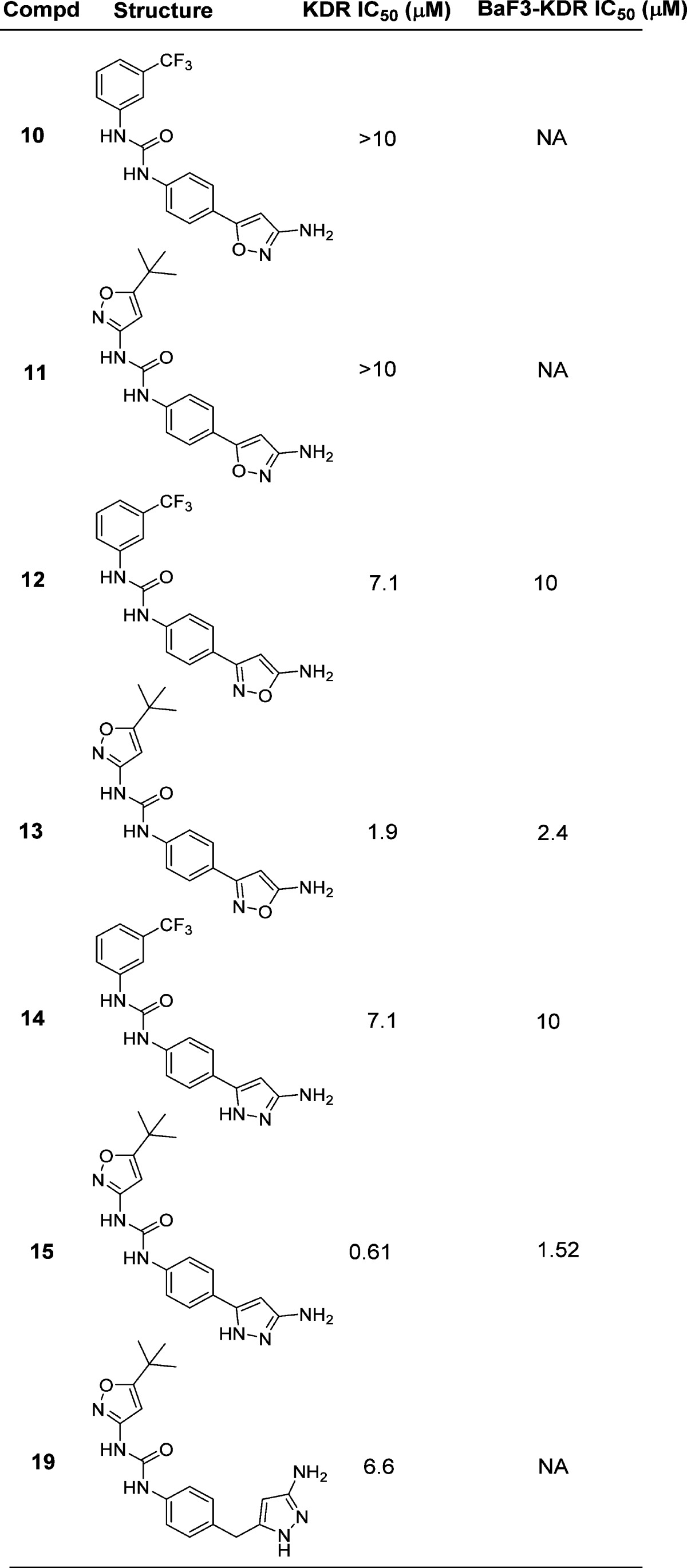

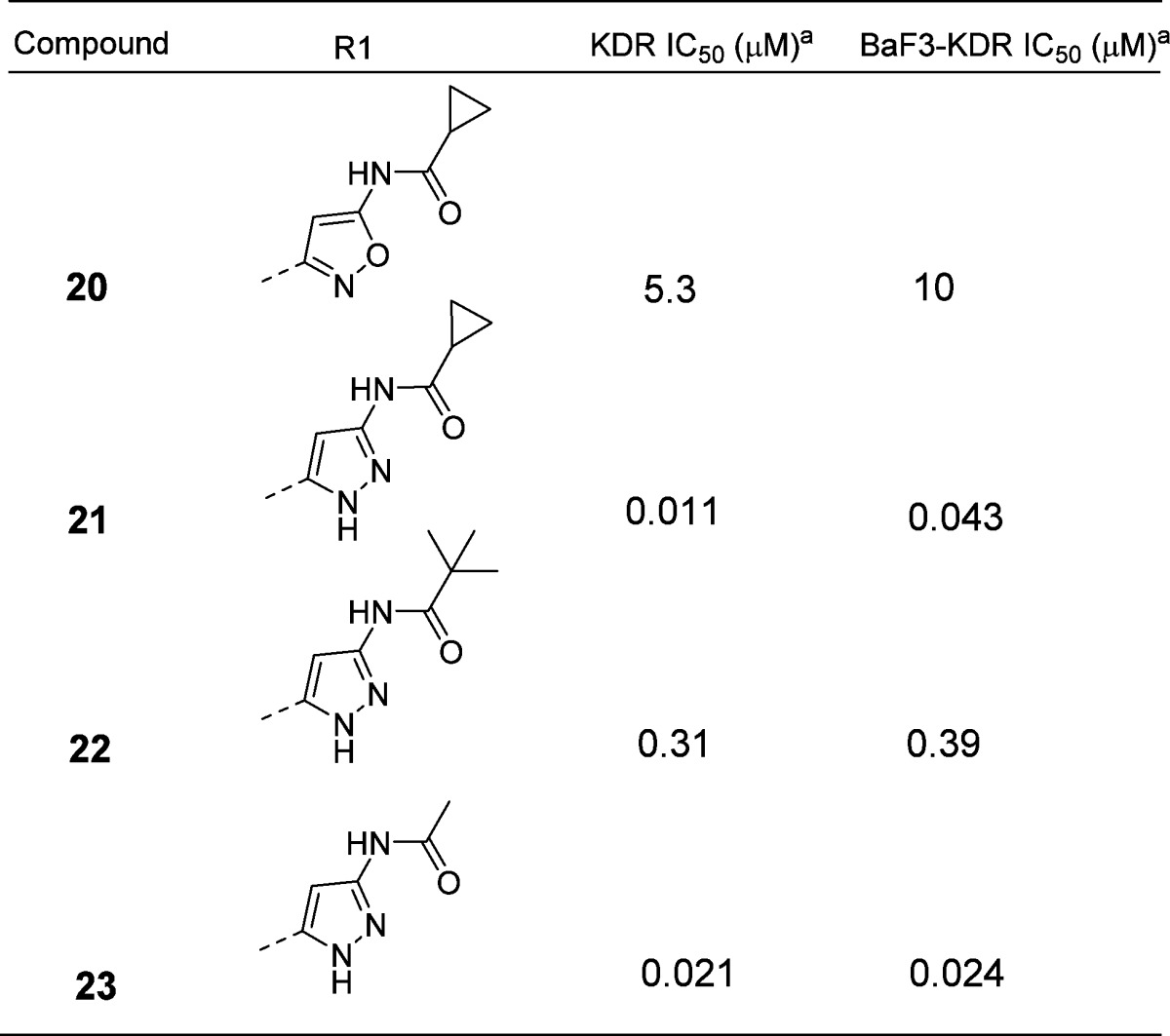

When we decided to investigate the ability of the aminoheterocycles in question to be efficient “hinge” binding moieties, we decided to include the more historically validated phenyl ureas together with the aminoheterocycle based ureas. The first set of compounds tested were all possible combinations of aminoisoxazole isomers, aminopyrazoles, and ureas (Table 1). Both enzymatic and cellular data showed that the 3-aminoisoxazole (compounds 10 and 11, Table 1) was not a suitable group for hinge interaction. The 5-aminoisoxazole compounds 12 and 13, however, showed some interesting activity especially in combination with the heterocycle based urea 13 (1.9 and 2.4 μM in biochemical and cellular assay, respectively). Of note, this type of urea SAR was also seen in the pyrimidine based series of VEGFR-2 inhibitors.2 The aminopyrazoles 14 and 15 also showed a promising potency profile pointing to the key role of the 1–3 relationship between the amino group and the ring nitrogen (not present in compounds 10 and 11) and a possible contribution of the second ring nitrogen at the 2-position. Aminopyrazole 19 was synthesized to explore if addition of a flexible linker would more closely replicate the spatial orientation of the progenitor series (compound 1, Figure 1). The disappointing biochemical potency of 19 (6.6 μM) directed further efforts to the improvement of inhibitors 13 and 15 especially around the hinge binding region. Cyclopropancarboxamide analogues of 13 and 15 helped in differentiating and in the selection of the better hinge binding motif (Table 2). Compound 21 with a pyrazole group for hinge binding was 400-fold more active than the isoxazole 20. This also demonstrated for the first time acylated aminopyrazole 21 as a potent VEGFR-2 inhibitor with excellent biochemical and cellular potency (11 and 43 nM, respectively) and in doing so validating the initial hypothesis that aminoheterocycles could function as pyrimidine replacements in this series of KDR inhibitors. Pyvaloyl (compound 22) and acetyl (compound 23) analogues of 21 supported the initial finding of pyrazolyl amide as efficient hinge binders, leading to potent inhibition of VEGFR-2.

Table 1. In Vitro VEGFR-2 Inhibitory Potency for Compounds Produced via Scheme 1.

Values are mean of at least two experiments (IC50, μM).

Table 2. Impact of the Aminoheterocycles on VEGFR-2 Inhibitory Potency.

Values are mean of at least two experiments (IC50, μM).

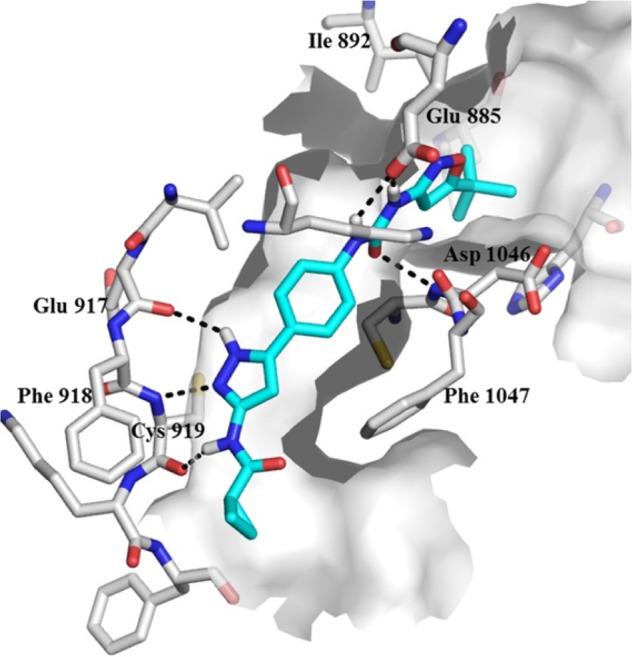

Molecular modeling21 of compounds 20 and 21 in the ATP-site of VEGFR-2 rationalized the potency differences seen for these inhibitors. As shown in Figure 2, aminopyrazole of inhibitor 21 makes H-bonding interactions with Glu917, Phe918, and Cys919 in the hinge, while the urea makes H-bonding interaction with Asp1046 and bidentate H-bonding with Glu885. The tert-butyl group is located in a hydrophobic pocket surrounded by residues Ile892, Val898, Leu1019, Met1016, His1026, and Ile1044. Inhibitor 20 can elicit similar binding mode, with the major difference observed in its interactions in the hinge region. While the donor −NH of pyrazole in 21 can make an additional H-bonding with Glu97 backbone carbonyl, in case of inhibitor 20 the acceptor oxygen in isoxazole will be electrostatically repulsive thereby causing loss in binding affinity and potency.

Figure 2.

Modeled binding mode of 21 (blue) in the ATP-binding site of VEGF-R2 (white). Hydrogen bonding interactions are shown as black dotted lines.

We have thus validated the hypothesis that simple aminoheterocycles can replace the pyrimidine in a well-established series of VEGFR-2 inhibitors2 and function as effective hinge binding moieties. It was also shown how aminopyrazoles are more efficient than aminoisoxazoles in binding in the ATP binding site of KDR substantiating empirical findings with molecular modeling experiments. The reported findings could have a substantial impact on the chemical diversity, physicochemical properties, and in vivo distribution profile of new series of VEFGR-2 inhibitors and hopefully offer further avenues toward new and less invasive therapies for patients suffering from AMD.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of the Analytical Sciences group at the Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research for support in generating the analytical details for the compounds described herein.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- AMD

age-related macular degeneration

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- Flt-1

FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1

- VEGFR-2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00486.

Author Present Address

§ N.M.: Raze Therapeutics, 400 Technology Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Brown D. M.; Kaiser P. K.; Michels M.; Soubrane G.; Heier J. S.; Kim R. Y.; Sy J. P.; Schneider S. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1432–1444. 10.1056/NEJMoa062655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith E. L.; Mainolfi N.; Poor S.; Qiu Y. B.; Miranda K.; Powers J.; Liu D. L.; Ma F. P.; Solovay C.; Rao C.; Johnson L.; Ji N.; Artman G.; Hardegger L.; Hanks S.; Shen S. Y.; Woolfenden A.; Fassbender E.; Sivak J. M.; Zhang Y. Q.; Long D.; Cepeda R.; Liu F.; Hosagrahara V. P.; Lee W.; Tarsa P.; Anderson K.; Elliott J.; Jaffee B. Discovery of Oral VEGFR-2 Inhibitors with Prolonged Ocular Retention That Are Efficacious in Models of Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 9273–9286. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainolfi N.; Powers J.; Meredith E. L.; Elliott J.; Poor S.; Fang L.; Anderson K.. Core Replacements in a Potent Series of VEGFR-2 Inhibitors and Their Impact on Potency, Solubility and hERG. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. To be published. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N.; DavisSmyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr. Rev. 1997, 18, 4–25. 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D. O.; Curry F. E. Vascular endothelial growth factor increases microvascular permeability via a Ca2+-dependent pathway. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circul. Physiol. 1997, 273, H687–H694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez P. F.; Sippy B. D.; Lambert H. M.; Thach A. B.; Hinton D. R. Transdifferentiated retinal pigment epithelial cells are immunoreactive for vascular endothelial growth factor in surgically excised age-related macular degeneration-related choroidal neovascular membranes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1996, 37, 855–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H.; Qiao X.; Gao R.; Mieler W. F.; McPherson A. R.; Holz E. R. Intravitreal triamcinolone does not alter basal vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA expression in rat retina. Vision Res. 2004, 44, 349–356. 10.1016/j.visres.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman B. I.; Doughervermazen M.; Carrion M. E.; Dimitrov D.; Armellino D. C.; Gospodarowicz D.; Bohlen P. Identification of the Kdr Tyrosine Kinase As A Receptor for Vascular Endothelial-Cell Growth-Factor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992, 187, 1579–1586. 10.1016/0006-291X(92)90483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T.; Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF Receptor Signal Transduction. Sci. Signaling 2001, 2001, re21. 10.1126/stke.2001.112.re21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. A.; Cheung M.; Hunter R. N.; Brown M. L.; Veal J. M.; Nolte R. T.; Wang L.; Liu W.; Crosby R. M.; Johnson J. H.; Epperly A. H.; Kumar R.; Luttrell D. K.; Stafford J. A. Discovery and Evaluation of 2-Anilino-5-aryloxazoles as a Novel Class of VEGFR2 Kinase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 1610–1619. 10.1021/jm049538w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTigue M.; Murray B. W.; Chen J. H.; Deng Y. L.; Solowiej J.; Kania R. S. Molecular conformations, interactions, and properties associated with drug efficiency and clinical performance among VEGFR TK inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 18281–18289. 10.1073/pnas.1207759109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenone S.; Bondavalli F.; Botta M. Antiangiogenic agents: an update on small molecule VEGFR inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 2495–2516. 10.2174/092986707782023622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Shan Y.; Pan X.; He L. Recent Advances in Antiangiogenic Agents with VEGFR as Target. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 920–946. 10.2174/138955711797068355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musumeci F.; Radi M.; Brullo C.; Schenone S. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Receptors: Drugs and New Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 10797–10822. 10.1021/jm301085w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M.; Nishigaki N.; Washio Y.; Kano K.; Harris P. A.; Sato H.; Mori I.; West R. I.; Shibahara M.; Toyoda H.; Wang L.; Nolte R. T.; Veal J. M.; Cheung M. Discovery of Novel Benzimidazoles as Potent Inhibitors of TIE-2 and VEGFR-2 Tyrosine Kinase Receptors. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 4453–4470. 10.1021/jm0611051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilodeau M. T.; Rodman L. D.; McGaughey G. B.; Coll K. E.; Koester T. J.; Hoffman W.; Hungate L. W.; Kendall R. L.; Mcfall R. C.; Rickert K. W.; Rutledge R. Z.; Thomas K. A. The discovery of N-(1,3-thiazol-2-yl)pyridin-2-amines as potent inhibitors of KDR kinase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 2941–2945. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy R.; Ghose A.; Singh J.; Bacon E. R.; Angeles T. S.; Yang S. X.; Albom M. S.; Aimone L. D.; Herman J. L.; Mallamo J. P. 1,2,3-Thiadiazole substituted pyrazolones as potent KDR/VEGFR-2 kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 1793–1798. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takase A.; Murabayashi A.; Sumimoto S.; Ueda S.; Makisumi Y. Practical Synthesis of 3-Amino-5-Tert-Butylisoxazole from 4,4-Dimethyl-3-Oxopentanenitrile with Hydroxylamine. Heterocycles 1991, 32, 1153–1158. 10.3987/COM-91-5712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L.; Powers J.; Ma F. P.; Jendza K.; Wang B.; Meredith E.; Mainolfi N. A Reliable Synthesis of 3-Amino-5-Alkyl and 5-Amino-3-Alkyl Isoxazoles. Synthesis 2013, 45, 171–173. 10.1055/s-0032-1317935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji N.; Meredith E.; Liu D. L.; Adams C. M.; Artman G. D.; Jendza K. C.; Ma F. P.; Mainolfi N.; Powers J. J.; Zhang C. Syntheses of 1-substituted-3-aminopyrazoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 6799–6801. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.10.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binding modes were obtained in a high resolution crystal structure of VEGF-R2 (PDB entry 3VHE) using induced fit docking from Schrödinger. Schrödinger Suite 2008 Induced Fit Docking protocol; Glide version 5.0, Prime version 1.7; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.