Abstract

The goals of palliative care address critical issues for individuals with complex and serious illness residing in nursing homes, including pain and symptom management, communication, preparation for death, decisions about treatment preferences, and caregiver support. Because of the uncertain prognosis associated with chronic nonmalignant diseases such as dementia, many nursing home residents are either not referred to hospice or have very short or very long hospice stays. The integration of palliative care into nursing homes offers a potential solution to the challenges relating to hospice eligibility, staffing, training, and obtaining adequate reimbursement for care that aligns with resident and surrogate’s preferences and needs. However, the delivery of palliative care in nursing homes is hindered by both regulatory and staffing barriers and, as a result, is rare. In this article, we draw on interviews with nursing home executives, practitioners, and researchers to describe the barriers to nursing home palliative care. We then describe 3 existing and successful models for providing nonhospice palliative care to nursing home residents and discuss their ongoing strengths and challenges. We conclude with specific policy proposals to expedite the integration of palliative care into the nursing home setting.

Keywords: Pallative care, models of care

There are approximately 1.5 million individuals residing in nursing homes (NH) in the United States.1 Individuals with dementia make up the largest single group of NH residents with prevalence estimates ranging from 48% to 66%.2–4 Most NH residents require either extensive assistance or total dependence for bathing, personal hygiene, transferring, and using the toilet.1 The average and median length of stay for NH residents is 835 and 463 days, respectively,1 and most residents (66%) die there.5 NHs are responsible for both the long-term management of individuals with multiple, complex, chronic illnesses, including dementia, and the care of these individuals at the end of life.

Provision of high-quality care in NHs is challenged by limited resources, overwhelmed frontline staff, and beleaguered leadership. Untreated or undertreated pain in NHs is well documented1,6–10 and roughly 4% of residents experience daily pain that is excruciating.11 Pressure ulcers (11% of residents),1 physical restraints (39% of residents),1 and feeding tubes (53.9 per 1000 persons in a 12-month period)12,13 are common. Inattention to advance care planning,14–18 inadequate use of hospice,19 and recurrent hospitalizations or “churn”20,21 are widespread, with an estimated 39% of NH residents hospitalized in the last 30 days of life.20 Hospitalization routinely results in medication errors,22 functional decline,23 and poor communication of new care plans.24 By 2030, it is estimated that more than 3 million individuals will reside in NHs and nearly 50% of adults will die there,25 yet NHs rank lowest in terms of family perceptions of quality among the last places of care,26 with families reporting not enough help with pain (32%), dyspnea (24%), and emotional support (50%).26

In this article, we describe strategies for improving access to palliative care in NHs. We draw on interviews conducted in the development of the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) 2008 report, “Improving Palliative Care in Nursing Homes,”25 as well as additional interviews conducted in 2009. The 2008 CAPC report25 was an environmental scan of palliative care services in NHs using literature review of research published between 2004 and 2007, 3 site visits, and 31 in-depth telephone interviews with NH medical directors and executives, palliative care providers in NH settings, and NH researchers. Individuals and sites were selected to provide a representative sample of NHs, including geographic diversity, rural and urban centers, and large and small NHs. Key topics discussed in these interviews included the needs of NH residents, the perceived challenges to delivering palliative care in NHs, influences on NH practice, and current innovative tools or programs to deliver palliative care in this setting. Based on these interviews, 3 existing, fully implemented models for providing palliative care to NH residents were identified, and here we discuss their strengths and challenges. We also conducted additional interviews with policy experts and executives from 2 of the sites whose models are featured. We conclude with specific policy proposals to expedite the integration of palliative care into the NH setting.

PALLIATIVE CARE OFFERS A SOLUTION

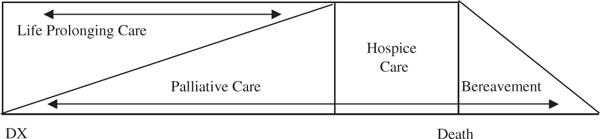

Palliative care is comprehensive interdisciplinary care that aims to relieve suffering and improve quality of life for individuals with advanced illness and their families. The goals of palliative care directly address what has been found to be most important to individuals with advanced illness: pain and symptom management, communication, preparation for death, decisions about treatment preferences, and caregiver support.27 Palliative care spans the continuum of need for patients who enter, have long stays, and ultimately die in the NH (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

The continuum of palliative care and hospice care.

Contrary to what is often believed, palliative care is not identical to hospice care, as it differs in terms of both timing and reimbursement. Palliative care is available to patients who continue to benefit from life-prolonging treatments and is not dependent on prognosis (Figure 1). Reimbursement for hospice care under the Medicare Hospice Benefit requires that an individual be certified by 2 physicians as “terminal” (defined as a prognosis of 6 months or less) and agree to give up Medicare coverage for life-prolonging therapies. Palliative care’s independence from prognosis is especially important for NH residents, as most die of chronic, debilitating diseases such as heart disease, stroke, or dementia28 for which prognostication is particularly difficult. Non-hospice palliative care physicians and advance practice nurses bill fee-for-service under Medicare Part B. Ideally, NH residents could receive palliative care services when needed based on objective measures of functional decline and need, independent of prognosis and in conjunction with all other beneficial therapies. As one interviewee stated,

“In nursing facilities, many residents are not hospice eligible but suffer from chronic pain and other conditions that are not being adequately treated.”

Gretchen M. Brown, MSW, President and CEO, Hospice of the Bluegrass (June 2009)

Recent estimates suggest that up to 80% of NH residents could benefit from palliative care.25 However, nonhospice palliative care in the NH setting is rare.

Barriers to NH Palliative Care

Significant regulatory and staffing barriers prevent widespread implementation of NH palliative care.

Regulatory Barriers to NH Palliative Care

A major regulatory barrier to delivering palliative care in the NH is the misperception that palliative care is incompatible with the restorative focus of NH reimbursement and regulation. Specifically, the Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI), which consists of the Minimum Data set (MDS) and a set of Resident Assessment protocols, uses expected signs of terminal illness such as functional decline, weight loss, and dehydration as indicators of inadequate care by the NH.29 The RAI does not include protocols for palliative care outcomes such as symptom control.29 As one interviewee described:

“Instead of weight loss being recognized as perhaps the start of an expected decline and triggering a palliative care approach and level of care (ie, aggressive symptom control and support), it triggers a cascade of appetite stimulants, dietary supplements, and invasive treatments such as feeding tubes and IV fluids, aimed at reversing the weight loss.”

Howard Tuch, MD, Director of Health Policy, Suncoast Hospice (Florida) (May 2009)

NHs’ fear of being charged with poor quality of care through the MDS assessments reinforces the exclusive emphasis on restorative care as a measure of NH care quality and inhibits delivery of palliative care (Table 1).

Table 1.

National Nursing Home Quality Measures

|

Chronic Care Quality Measures: Percentage of residents with

|

|

Postacute Care Quality Measures: Percentage of short stay residents with

|

Source: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Nursing Home Quality Measures: User’s Manual, November 2004 (vo1. 2).

Second, the economic incentives in long-term care promote hospitalization because residents who return to the NH from the hospital are covered by the more generous “Skilled” Medicare Benefit, which is applicable for the first 100 days after a hospital discharge.30 This payment structure creates a strong financial incentive for NHs to rehospitalize their residents to maximize the number of residents with this higher level of coverage.29 Further, the prospective reimbursement categories, the Resource Utilization Groups (RUGs), do not include palliative care. RUGs for intensive rehabilitation or skilled care (eg, intravenous medications and tube feeding) are far more generously reimbursed than personal care, symptom management, and emotional and spiritual support,29 creating a direct financial incentive for artificial nutrition and hydration and intravenous therapies even among the very debilitated and dying. As one of our interviewees explained,

“Higher reimbursement for skilled RUGs presents a strong incentive to deliver rehabilitative care to patients who may be more appropriately managed with palliative care approaches.”

Howard Tuch, MD, Health Policy Director, Suncoast Hospice (Florida) (May 2009)

The more generous reimbursement of the Skilled Medicare Benefit also increases health care costs because eligibility for the Skilled Medicare Benefit requires that the resident be hospitalized for at least 3 days before coverage. Hence, financial pressures can lead NHs to transfer residents to the hospital during acute episodes of illness because upon return to the NH, reimbursement may be under the generous Skilled Medicare Benefit.20,21,30 It is estimated that more than 40% of these hospitalizations are inappropriate and residents could have safely remained in the NH.31

Medicare policies also serve as a barrier to the receipt of hospice care. An NH resident under the Skilled Medicare Benefit cannot simultaneously receive hospice care under the Medicare Hospice Benefit. The forced choice between these Medicare benefits is not financially neutral. The Skilled Medicare Benefit pays for a NH resident’s room and board, whereas the Medicare Hospice Benefit does not. Not surprisingly, residents who are eligible for hospice typically choose to delay enrollment until after the Skilled Medicare Benefit period ends, simply for financial reasons.5 (For NH residents dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, Medicaid generally covers the room and board costs and thus the choice between the Medicare Hospice Benefit and the Skilled Medical Benefit is approximately financially neutral to the resident.) More worrisome, NHs may not even offer hospice to residents who have Skilled Medicare Benefit days remaining.29

Staffing Barriers to NH Palliative Care

Perhaps the most immediate barrier to improving access to palliative care in NHs is inadequate training and numbers of staff. NHs face a significant labor shortage and high turnover because of the difficulty of the work, inadequate pay, low respect, and demanding paperwork and regulatory requirements.32 Up to 90% of NHs are understaffed,33 leading to substandard care.34 NHs tend to have lower proportions of registered nurses (RNs) than other health care settings32 and the RNs working in NHs often have administrative and supervisory duties rather than direct patient care.32,35 Turnover at all levels, from frontline staff to leadership, is high, exceeding 100% annually in some homes.36

Compounding the shortage of staff is the lack of NH staff trained in palliative care. Education focuses on direct patient care tasks with little exposure to symptom assessment and treatment, communication, psychosocial and spiritual support at the bedside, and decision making. Consequently, NH staff have been found to fall short in assessing and managing common symptoms such as pain and shortness of breath, and continuity of caregivers is poor.37–39

Successful Models of NH Palliative Care

Despite these barriers, there are exemplary programs across the country succeeding in delivering NH palliative care. Using data from our interviews and site visits, we identified 3 different strategies for integrating palliative care into NHs. Although every community is different and the strategies presented here may not be applicable to every NH’s needs, these 3 different approaches provide examples of success in providing NH palliative care. In the following sections, we describe 3 such models (Table 2) and discuss factors considered relevant to their successful implementation, as well as challenges that have accompanied these efforts.

Table 2.

Models for the Delivery of Palliative Care to Nursing Home Residents

| Model | Description | Example Program | Payment Model | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palliative Care Consult Service | MDs and NPs employed by a palliative care center provide palliative care consultations to nonhospice nursing home residents | Palliative Care Center of the Bluegrass, Lexington, Kentucky | Palliative care consultant (MD or NP) bills Medicare Part B | Requires clearly established roles between the nursing home and palliative care staff; No reimbursement for the rest of the interdisciplinary palliative care team; Nursing home staff may have difficulty differentiating palliative and hospice care |

| Nursing Home-Based Palliative Care | Nursing home employs an internal palliative care NP or team (NP, SW, chaplain, MD) | Morningside House, Bronx, NY | MD and NP bills Medicare Part B | Requires high quality ongoing training of palliative care staff, strong leadership commitment, and the size and capacity to scale the innovation |

| Nursing home contracts with a Medicare Managed care program for nurse practitioners with palliative care expertise | Evercare Hospice and Palliative Care, multiple locations | Full risk capitation | Evercare provides its own hospice care and is not regulated by Medicare’s hospice conditions of participation | |

| Hospice-Nursing Home Partnership | Interdisciplinary team employed by a hospice provides hospice care to nursing home residents | Sunrise Retirement Community, Sioux City, Iowa | Hospice care is billed under the Medicare Hospice Benefit | Requires leadership commitment at the nursing home and hospice; requires strong communication and clear delineation of policies, roles, and responsibilities |

Model 1: Palliative Care Consult Service

The palliative care consult service model uses outside consultants on request of the NH medical director, the patient’s attending physician, or the NH director of nursing. An advantage of the consult model is that palliative care is available to all residents, not just those who are clearly dying and therefore hospice eligible. Further, palliative care expertise is available without additional costs to the NH.

The Palliative Care Center of the Bluegrass (PCCB) in Lexington, Kentucky, is an example of the palliative care consult model. Consultation requests focus on pain and symptom management, advance care planning, family communication, and transition to hospice. In 2008, PCCB consultants visited 325 residents in 11 NHs and each resident received 5 to 6 visits, on average. Forty percent of these residents later transitioned to hospice care with a mean length of hospice stay of 66 days. According to a PCCB executive,

“We have no doubt that for most of these patients palliative care consults and subsequent hospice care avoided hospitalization, which is better for the residents and, in terms of costs, better for Medicare.”

Gretchen M. Brown, MSW, President and CEO, Hospice of the Bluegrass (June 2009)

Although the PCCB has successfully implemented the consult service model, replication of this model of NH palliative care requires a number of key success factors (Table 3) and the ability to overcome substantial challenges. First, the model is contingent upon access to palliative care providers in the NH’s service area. Second, from the perspective of the palliative care providers, financial viability depends on the economies of scale in travel and staffing available at larger NHs with greater numbers of residents receiving services. Third, palliative care consultants require training specific to the needs of NH residents.32 Fourth, the consultative relationship may inhibit continuity of palliative care, risking lack of necessary expertise during unpredictable illness and a default to hospitalization.25 Finally, for nonhospice palliative care consultants employed by hospice agencies,40 it is difficult for NH staff to differentiate between palliative and hospice care, in terms of patient eligibility, needs, regulatory requirements, and payer considerations.

Table 3.

Key Success Factors for Palliative Care Consultation in the Nursing Home

|

Sources: Center to Advance Palliative Care. Improving Palliative Care in Nursing Homes; 2008. Available at: http://www.capc.org/support-from-capc/capc_publications/nursing_home_report.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2010.

Model 2: NH-Based Palliative Care

An increasingly prevalent model is NH employment of its own palliative care team. Unlike the outside consultant, the in-house practitioner’s daily interaction with residents may facilitate timely detection of clinical changes.32 Daily contact also promotes understanding of resident/family values, personal goals, and care preferences.32

• Morningside House

An example of NH-based palliative care delivery is Morningside House, a 386-bed nonsectarian NH in the Bronx that established its own palliative care team (MD, nurse practitioner, social worker, and chaplain). Factors considered key to the success of Morningside House’s NH-based palliative care model are shown in Table 4. Morningside’s CEO has a strong commitment to the program, stating “It’s all about leadership,” and ensures that it is attentive to the cultural and religious preferences of the residents. Standardization is strengthened through broad use of The Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST)41–43 to ascertain specific care goals and translate them into medical orders to ensure that care received is concordant with goals. Palliative care staff receive tuition reimbursement for training, and frequent in-services on palliative care are provided for both staff and families. As described by the CEO, the outcomes of this program include improved staff retention, better resident/family satisfaction, more deaths occurring at “home,” and fewer hospitalizations.25,44,45

“Pizza at midnight is okay. Recliner next to Mom’s bed is fine. We provide resident-centered care.”

Morningside’s Vice President for Nutritional Services (January 2007)

Table 4.

Success Factors for Nursing Home–Based Palliative Care

|

Sources: Center to Advance Palliative Care. Improving Palliative Care in Nursing Homes; 2008. Available at: http://www.capc.org/support-from-capc/capc_publications/nursing_home_report.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2010.

Morningside House. Available at: www.allcarenet.org/memdir/mornings.html. Accessed June 15, 2009.

Aging in America. Morningside House Nursing Home & Rehabilitation Service Care. Available at: www.aiamsh.org/rehabilitation/. Accessed June 15, 2009.

• Evercare Hospice and Palliative Care

Alternatively, the NH-based palliative care model may contract with a Medicare managed care organization for palliative care staff. For example, Evercare Hospice and Palliative Care is a Medicare managed care organization that operates as a full-risk capitation model employing nurse practitioners in 35 states to provide on-site medical care, case management, and palliative care to more than 100,000 NH enrollees (Table 5). For NHs using Evercare, the financial risk for a resident’s care, including hospitalizations, shifts from the NH to Evercare. Evercare’s version of palliative care requires neither a terminal prognosis nor a decision to stop life-prolonging treatment. Because of the strong financial incentive to avoid hospitalization, in one study, Evercare reduced hospitalizations by 45%, emergency department visits by 50%, and average length of stay in the hospital by 1 day.46

Table 5.

Evercare Palliative Care Pledge

|

Our Seven-Point Pledge Within our power, we are committed to providing the best hospice and palliative care experience available. That commitment is expressed in our Seven-Point Pledge. |

Evercare Hospice & Palliative Care pledges to

|

A challenge to scaling the NH-based palliative care model is the lack of availability of palliative care–trained nurse practitioners and other professionals. Further, financial viability of such models is tenuous because the average 120-bed NH does not have the volume of residents required to support the cost of salary support and benefits for the palliative care staff.

Model 3: NH–Hospice Partnerships

Well-integrated hospice care in a NH has been shown to enhance access to palliative care for all NH residents through knowledge diffusion, availability of palliative care technologies on-site, and heightened awareness of pain and symptom management, psychosocial, and spiritual needs.47 These “spillover effects” in culture and caregiving philosophy are evidenced by substantially lower hospitalization rates20,48 and higher rates of advance care planning and pain treatment48 for NHs offering hospice compared with those that do not, varying by length of hospice stay and hospice diagnosis. NH resident enrollment in hospice in the last month of life is estimated to reduce overall government spending by an average of 6%.49 One researcher we interviewed found that

“…homes with strong hospice collaboration have few resident unmet needs and have greater satisfaction, less invasive treatments, fewer hospitalizations, and provide better care practices.”

Susan C. Miller, PhD, Center for Gerontology and Health Care Research, Brown University25 (November 2006)

As of 2004, 78% US NHs reported a contract with a hospice,50 ranging from 96% in Florida to only 42% in Wyoming. However, the level of penetration, quality, and timeliness of access to hospice care among NHs with hospice contracts is unknown. The proportion of NH decedents using hospice at some point varies from 9% (Vermont) to 42% (Oklahoma),20 suggesting that the existence of a hospice contract may not always translate into access to hospice care.51

POLICY ACTIONS TO FACILITATE AND EXPEDITE IMPLEMENTATION OF NH PALLIATIVE CARE

Implementation of palliative care in NHs will require changes to the current regulatory and reimbursement environment, and investment in the workforce necessary to address the shortage of qualified palliative care practitioners.

Eliminate Economic and Regulatory Disincentives for Palliative Care

The perverse economic and regulatory disincentives for NH palliative care must be addressed to ensure that care decisions are based on resident needs. Specifically, a new RUG should be created for residents assessed on the MDS to have functional decline, weight loss, decreased appetite, shortness of breath, and frequent hospitalization or acute infections. These indicators are reliable predictors of an increased likelihood of death52 and could be used to identify residents appropriate for a palliative care focus, either in place of or in addition to, a restorative care focus (Table 1). In addition, states should consider ways of reimbursing for palliative care through the Medicaid program. As one interviewee stated:

“Last year during brainstorming sessions orchestrated by the New York State Department of Health regarding alternative forms of reimbursement, one idea that was raised within the context of payments for quality was to provide nursing homes that demonstrate minimum standards and competency in palliative care with additional reimbursement for residents who require palliative care services.”

Audrey Weiner, DSW, MPH, President and CEO of Jewish Home Lifecare, New York, NY (June 2009)

Second, the financial incentive to hospitalize NH residents should be removed. One option is to eliminate the 3-day hospital stay requirement for the Medicare Skilled Benefit. Many Medicare Advantage plans have eliminated this requirement, suggesting that the approach may have favorable consequences for both residents and Medicare spending.25

Third, the prohibition of hospice care while on the Medicare Skilled Benefit immediately following hospitalization should be removed so that residents eligible for hospice care or nonhospice palliative care could access it when needed. As one interviewee explained,

“Some amount of rehabilitation is often required to improve the quality of life of a resident transitioning from the hospital to the NH, even when hospice is involved.”

Judi Lund Person, MPH, Vice President of Regulatory and State Leadership for the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (May 2009)

Similar to hospice care among specific subgroups ofMedicare beneficiaries,49 nonhospice palliative care has the potential to provide overall cost savings through clarification of care goals and reduced hospitalization. For example, hospital palliative care programs result in cost savings because of better care coordination, clarified treatment goals, and the avoidance of expensive, nonbeneficial treatments covered by Medicare Part A.53–55

Establish a Licensure Program for Palliative Care Units in NHs

In conjunction with removing regulatory and financial disincentives for palliative care, a licensure program for NHs to train and “specialize” some of their own staff in palliative care could reduce the shortage of palliative care NH staff. As one interviewee stated,

“NHs can be incentivized to have palliative care expertise improved within their own staff. This allows NHs to stay in control, while improving the quality delivered to a specific NH population.”

Laura C. Hanson, MD, Co-Director, University of North Carolina Palliative Care Program (May 2009)

The licensure program could help ensure the quality and content of palliative care training and delivery. As one interviewee explained,

“We are starting to see an increase in the number of homegrown palliative care programs in NHs. These programs try to mimic palliative care principles but often without the palliative care expertise to back it up. Essentially these programs are plagiarized hospice programs. They are offering staff training in palliative care but the training is not coming from anyone certified in palliative care or hospice.”

Todd Cote, MD, Chief Medical Officer, Palliative Care Center of the Bluegrass (June 2009)

Require NHs to Provide Access to Hospice

Access to hospice care should be a requirement for NH reimbursement from Medicare and Medicaid. In addition to demonstration of one or more hospice contracts, NHs could be required to report the percentage of resident deaths in the NH who accessed hospice in the prior year. These conditions would give a reasonable assessment of both the existence and penetration of hospice care within the NH.

The most recent Conditions of Participation for hospices56 defines the responsibilities, documentation, communication, and training required of hospices serving skilled nursing facilities. A parallel regulation for NHs that have residents receiving hospice is currently under review. These regulations clarify the responsibilities of each provider and the right of patients to access hospice while residing in a long-term care facility.

Invest in a Palliative Care Workforce

Improved access to palliative care in NHs cannot be achieved without efforts to address the shortage of qualified palliative care practitioners. Such investments include loan forgiveness programs for nurses, social workers, and physicians who agree to work in NH palliative care for a specified period of time, graduate and midcareer training programs, and recruitment strategies. A multipronged approach is needed to attract, train, and retain the workforce necessary to serve the growing NH population in need of palliative care.

CONCLUSION

There is broad consensus that a solution to some of the pressing problems of quality and cost in NHs is greater penetration of palliative care into the long-term care setting. We describe 3 operating models for delivering NH palliative care: outside nonhospice palliative care consultants, development of NH staff expertise in palliative care, and greater penetration of hospice services through NH–hospice partnerships. However, as this is a descriptive report based on a convenience sample, there may be additional effective models that have not been included here. The generalizability and applicability of these models depends on the NH setting, capacity, leadership, and community environment. Broad implementation of these models is dependent upon addressing the formidable barriers to NH palliative care including regulation, payment, and staffing. Our interviews with leaders in the field identified policy initiatives that could facilitate NH palliative care.

There is no patient population more vulnerable or more in need of care focused on achieving the best possible quality of life in the context of advanced and progressive illness than persons living in NHs. The near absence of such care matched to the needs of the most vulnerable is a solvable problem, as demonstrated by the examples described here. Policy change and investment are needed to make access to quality palliative care a reality for all requiring, and all who will require, long-term care.

Acknowledgments

M.D.A.C. is a Brookdale Leadership in Aging Fellow and supported by a National Institute of Nursing Research Career Development Award (1K99NR010495–01); B.L. is supported by a Career Development Award from the Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation; D.E.M.is supported by, a 2009–2010 Health and Aging Policy Fellowship, NCI R01CA 116227, and the Center to Advance Palliative Care.

References

- 1.Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR, Strahan GW. The national nursing home survey: 2004 overview. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics. 2009;13:167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banaszak-Holl J, Zinn JS, Brannon D, et al. Specialization and diversification in the nursing home industry. Health Care Manag. 1997;3:91–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magaziner J, German P, Zimmerman SI, et al. The prevalence of dementia in a statewide sample of new nursing home admissions aged 65 and older: diagnosis by expert panel. Epidemiology of Dementia in Nursing Homes Research Group. Gerontologist. 2000;40:663–672. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Dijk PT, Mehr DR, Ooms ME, et al. Comorbidity and 1-year mortality risks in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:660–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furman CD, Pirkle R, O’Brien JG, Miles T. Barriers to the implementation of palliative care in the nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8:e45–e48. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teno JM, Weitzen S, Wetle T, Mor V. Persistent pain in nursing home residents. JAMA. 2001;285:2081. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2081-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrell BA, Ferrell BR, Osterweil D. Pain in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:409–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, et al. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE Study Group. Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology. JAMA. 1998;279:1877–1882. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller SC, Mor V, Wu N, et al. Does receipt of hospice care in nursing homes improve the management of pain at the end of life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:507–515. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Painter K. Nurse dispenses dignity to dying. USA Today. Available at: www.usatoday.com/life/people/2003-12-30-hospice-nurse-main_x.htm. Accessed September 7, 2010.

- 11.Teno JM, Kabumoto G, Wetle T, et al. Daily pain that was excruciating at some time in the previous week: Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:762–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Roy J, et al. Clinical and organizational factors associated with feeding tube use among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2003;290:73–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Skinner J, et al. Churning: The association between health care transitions and feeding tube insertion for nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:359–362. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley EH, Wetle T, Horwitz SM. The patient self-determination act and advance directive completion in nursing homes. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:417–423. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.5.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castle NG, Mor V, Banaszak-Holl J. Special care hospice units in nursing homes. Hosp J. 1997;12:59–69. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1997.11882869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley EH, Walker CW. Education and advance care planning in nursing homes: The impact of ownership type. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 1998;27:339–357. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley E, Walker L, Blechner B, Wetle T. Assessing capacity to participate in discussions of advance directives in nursing homes: Findings from a study of the Patient Self Determination Act. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:79–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradley EH, Blechner BB, Walker LC, Wetle TT. Institutional efforts to promote advance care planning in nursing homes: Challenges and opportunities. J Law Med Ethics. 1997;25:150–159. 183. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1997.tb01890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones B, Nackerud L, Boyle D. Differential utilization of hospice services in nursing homes. Hosp J. 1997;12:41–57. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1997.11882868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller SC, Gozalo P, Mor V. Hospice enrollment and hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Am J Med. 2001;111:38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castle NG, Mor V. Hospitalization of nursing home residents: A review of the literature, 1980–1995. Med Care Res Rev. 1996;53:123–148. doi: 10.1177/107755879605300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boockvar K, Fishman E, Kyriacou CK, et al. Adverse events due to discontinuations in drug use and dose changes in patients transferred between acute and long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:545–550. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.5.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillick MR, Serrell NA, Gillick LS. Adverse consequences of hospitalization in the elderly. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:1033–1038. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourbonniere M, Teno J, Roy J, Mor V. Transitions at the end of life: Quality of care and information continuity [abstract] J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:S40–S41. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Center to Advance Palliative Care. Improving Palliative Care in Nursing Homes. 2008 Available at: http://www.capc.org/support-from-capc/capc_publications/nursing_home_report.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2010.

- 26.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zerzan J, Stearns S, Hanson L. Access to palliative care and hospice in nursing homes. JAMA. 2000;284:2489–2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanson LC. Creating excellent palliative care in nursing homes. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:7–9. doi: 10.1089/10966210360510064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grabowski DC. Medicare and Medicaid: Conflicting incentives for long-term care. Milbank Q. 2007;85:579–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saliba D, Kington R, Buchanan J, et al. Appropriateness of the decision to transfer nursing facility residents to the hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:154–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ersek M, Wilson SA. The challenges and opportunities in providing end-of-life care in nursing homes. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:45–57. doi: 10.1089/10966210360510118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pear R. 9 of 10 nursing homes lack adequate staff, study finds. New York Times on the Web. Available at: www.nytimes.com/2002/02/18/national/18NURS.html. Accessed: June 8, 2009.

- 34.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Appropriateness of minimum staffing ratios in nursing homes. Baltimore: ABT Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fulmer T, Mezey M. Contemporary geriatric nursing. In: Hazzard W, Blass J, Ettinger W, et al., editors. Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 4th. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hostetter M. Issue of the month: Changing the culture of nursing homes. Quality Matters: Nursing Home Improvement, a Newsletter from the Commonwealth Fund. 2007 Jan-Feb Vol. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ersek M, Grant MM, Kraybill BM. Enhancing end-of-life care in nursing homes: Palliative Care Educational Resource Team (PERT) program. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:556–566. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ersek M, Kraybill BM, Hansberry J. Assessing the educational needs and concerns of nursing home staff regarding end-of-life care. J Gerontol Nurs. 2000;26:16–26. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20001001-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller SC, Teno JM, Mor V. Hospice and palliative care in nursing homes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2004;20:717–734. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Four Seasons. Home page. Available at: http://www.fourseasonscfl.org/what-we-offer.php?seasons5palliative-care-services. Accessed June 15, 2009.

- 41.Meier DE, Beresford L. POLST offers next stage in honoring patient preferences. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:291–295. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.9648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bomba PA, Vermilyea D. Integrating POLST into palliative care guidelines: A paradigm shift in advance care planning in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4:819–829. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2006.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cantor MD. Improving advance care planning: Lessons from POLST. Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1343–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morningside House. Home page. Available at: www.allcarenet.org/memdir/mornings.html. Accessed June 15, 2009.

- 45.Aging in America. Morningside House Nursing Home & Rehabilitation Service Care. Available at: www.aiamsh.org/rehabilitation/. Accessed June 15, 2009.

- 46.Kane RL, Keckhafer G, Flood S, et al. The effect of Evercare on hospital use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1427–1434. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welch LC, Miller SC, Martin EW, Nanda A. Referral and timing of referral to hospice care in nursing homes: The significant role of staff members. Gerontologist. 2008;48:477–484. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levy C, Morris M, Kramer A. Improving end-of-life outcomes in nursing homes by targeting residents at high-risk of mortality for palliative care: Program description and evaluation. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:217–225. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gozalo PL, Miller SC, Intrator O, et al. Hospice effect on government expenditures among nursing home residents. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:134–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller SC, Han B. End-of-life care in U.S. nursing homes: Nursing homes with special programs and trained staff for hospice or palliative/end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:866–877. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gozalo PL, Miller SC. Hospice enrollment and evaluation of its causal effect on hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:587–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Porock D, Oliver DP, Zweig S, et al. Predicting death in the nursing home: Development and validation of the 6-month Minimum Data Set mortality risk index. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:491–498. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:855–860. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bruera E, Neumann CM, Gagnon B, et al. The impact of a regional palliative care program on the cost of palliative care delivery. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:181–186. doi: 10.1089/10966210050085241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fromme EK, Bascom PB, Smith MD, et al. Survival, mortality, and location of death for patients seen by a hospital-based palliative care team. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:903–911. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs: Hospice Conditions of Participation; Final Rule. 73 Federal Register. 2008;109 (codified at 42 CFR Part 418) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]