Abstract

Hypertension is the most prevalent modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and disorders directly influencing CVD morbidity and mortality such as diabetes, chronic kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea, etc. Despite aggressive attempts to influence lifestyle modifications and advances in pharmacotherapeutics, a large percentage of patients still do not achieve recommended blood pressure control world-wide. Thus, we believe that mechanism-based novel strategies should be considered in order to significantly improve control and management of hypertension. The overall objective of this review is to summarize implications of peripheral- and neuroinflammation as well as the autonomic nervous system-bone marrow communication in hematopoietic cell homeostasis and their impact on hypertension pathophysiology. Additionally, we discuss the novel and emerging field of intestinal microbiota and roles of gut permeability and dysbiosis in CVD and hypertension. Finally, we propose a “brain-gut-bone marrow” triangular interaction hypothesis and discuss its potential in the development of novel therapies for hypertension.

Keywords: Hypertension, microbiota, neuroinflammation, bone marrow

Despite decades of advancements in the management and treatment, the prevalence of hypertension continues to remain high, since it has been difficult to achieve recommended blood pressure (BP) goals in a large proportion of this patient population at-risk for adverse outcomes1,2. Accumulating evidence indicates that bone marrow (BM) plays critically important regulatory roles in both peripheral- and neuro-inflammation associated with many pathophysiological conditions. This has led us to investigate the neural communication between BM and the brain in hypertension.

Thus, the objectives of this review are to summarize recent advances in knowledge that link neuroinflammation with hypertension, and the role of the autonomic nervous system in regulation of BM cell activity. Furthermore, we will discuss the implications of gut pathophysiology and microbiota in BP control and hypertension. Finally, we will propose a unifying brain-gut-BM triangular interaction hypothesis, which we believe contributes to persistent and chronic hypertension, and may provide an opportunity to develop novel therapeutic strategies for this disease.

Neuroinflammation

Our understanding of the involvement of neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of hypertension has become more robust in the recent years. Multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as leukotriene-B44, C–C chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2)5, NF-κb6, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1)7, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-68, have all been documented to be elevated in the brains of animal models of hypertension. Although the mechanisms remain under investigation, an enhanced vasodeleterious axis of the renin angiotensin system (RAS)9, such as angiotensin type 1 receptors (AT1R) and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), have been shown to be involved in driving central pro-inflammatory pathways6, 10. In contrast, central overexpression of ACE2, a member of the vasoprotective axis of the RAS, beneficially attenuates neurogenic hypertension11. Consistent with this knowledge is the observation that shedding of membrane-bound ACE2 is involved in neurogenic hypertension12. Finally, sRA mice that have an overactive brain RAS also have elevated production of several pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain13. These findings highlight the importance of the RAS in neuroinflammation and hypertension.

How neuroinflammation modulates BP is an area of active investigation. Evidence indicates that increased inflammation in cardioregulatory brain centers is associated with elevated sympathetic nervous system drive that leads to increased BP; conversely, inhibiting these central pro-inflammatory pathways dampens the increase in BP14. Additionally, central nervous system (CNS) injection of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and TNF-α, increases sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) and BP15. Furthermore, inhibition of brain TNF-α attenuates the development of hypertension in animal models8, 16. Thus, while there is a general consensus of the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in central BP control, the origin of these cytokines remains unclear. While it is true that circumventricular organs may respond to systemic cytokines17, these cytokines can also be produced centrally and released by neurons10 and microglial cells to induce pro-inflammatory processes18.

The contribution of microglial cells is of particular relevance in this regard. Microglial cells are the innate immune cells of the brain, constantly surveying the brain environment, promoting immune homeostasis, and producing neurotrophic factors. They become activated in response to pathological insults and alterations in brain homeostasis19. Our group was among the first to demonstrate the involvement of brain microglial cells in hypertension, an observation now supported by others7, 20. Inhibition of microglia activation is associated with attenuation of hypertension, sympathetic activation, and peripheral inflammation5, 20. Furthermore, specific deletion of brain microglia attenuates Ang II-induced hypertension21. A particularly interesting issue is whether these microglia are directly responding to Ang II, or if this response is mediated by other neuronal factors. There is no consensus on this issue at present. Evidence indicates that resting microglia in the adult brain do not express AT1R18, although others have demonstrated effects of Ang II on these cells both in vitro and in vivo22, 23. This discrepancy could be due to the fact that microglial cells do not express AT1R in normal physiological conditions unless primed by certain stimuli24, such as pro-hypertensive stress signals. Thus, it would be reasonable to suggest that pro-hypertensive signals, such as Ang II, that are known to activate autonomic neurons, could generate mediators that could cause microglial cell activation/differentiation leading to their responsiveness to Ang II. Support for this contention is the evidence that Ang II causes generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)25 and cytokines, such as CCL2 and HMGB1, that are known to impact microglia19. Further investigation is needed to clarify this area of neuronal-mediated microglial activation.

Brain-Bone Marrow Communication

As mentioned above, neuroinflammation contributes to peripheral sympatho-excitation. Our group has shown that the femoral sympathetic nerve is activated and BM norepinephrine contents are elevated during hypertension. BM is highly innervated by the sympathetic nervous system26. This sympathetic innervation regulates hematopoiesis and the stem cell niche homeostasis27. Sympathetic signals from the brain are thought to travel through adrenergic nerve fibers to BM releasing neurotransmitters that impact hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) mobilization and release into the general circulation28, 29. For example, catecholaminergic neurotransmitters control the release of HSPCs from BM by G-CSF induced osteoblast suppression and bone CXCL12 regulation26, or by directly modulating the Wnt-β-catenin pathway in HSPCs30. BM sympathetic fibers can also regulate HSPC mobilization through substance P-mediated nociceptive signaling31. Although this mechanism remains to be investigated in hypertension, it has been characterized in patients with diabetes32.

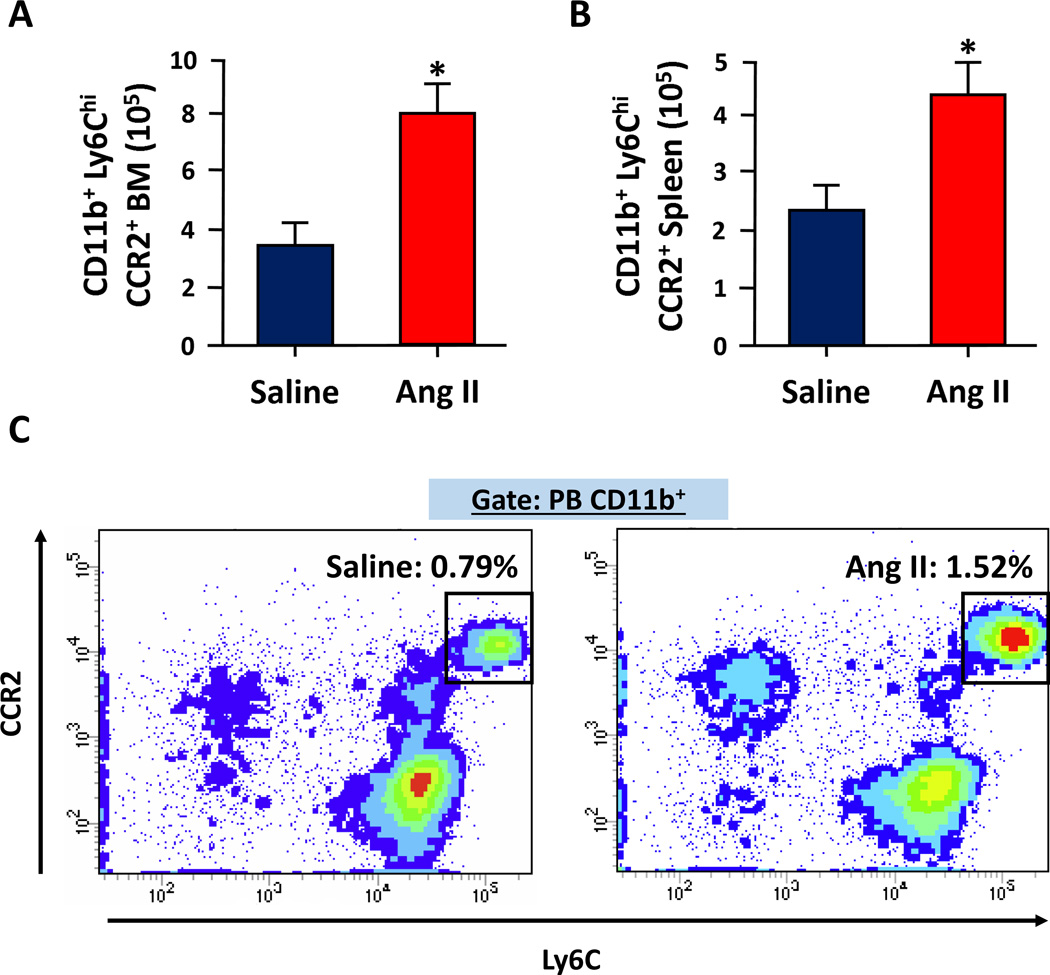

Dysfunction of BM sympathetic tone or complete sympathetic denervation has been associated with impaired HSPC mobilization and loss of circadian rhythmicity of HSPC release26, 29. Additionally, inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake is associated with enhanced HSPC mobilization33. Sympathetic innervation to BM has also been shown to be important in several cardiovascular pathologies. In myocardial infarction and stroke, enhanced sympathetic drive to BM mobilizes HSPCs and increases the output of inflammatory monocytes34, 35. This process has been specifically attributed to CCR2+ HSPCs36. Our research indicates that in hypertension, enhanced sympathetic tone to BM is associated with loss of circadian rhythmicity possibly associated with altered adrenergic signaling37. Additionally, we have recently observed that Ang II regulates HSPC proliferation in BM and enhances production of inflammatory monocytes in the spleen also via CCR2+ HSPCs38. These studies provide convergent evidence that Ang II-induced increases of CCR2+ HSPCs and myeloid progenitors in BM and spleen could contribute to the development of hypertension through increased sympathetic drive to BM. However, it remains to be determined if CCR2+ HSPCs are also activated in other models of hypertension and if CCR2+ HSPCs are rhythmically released from BM in response to sympathetic drive.

In addition to regulating HSPC mobilization from BM, the sympathetic nervous system regulates the immune system in a circadian manner39. Adrenergic nerves have been shown to regulate recruitment of leukocytes to tissues40. Norepinephrine stimulates immune cells to regulate proliferation, differentiation, maturation, and effector functions41. Specifically, adrenergic receptor stimulation of immune cells has been implicated in both anti- and pro-inflammatory responses42. Autonomic modulation of the immune system appears to be important in development of hypertension-related pathology and appears to be specifically biased towards enhanced pro-inflammatory responses. Our data (Figure 1) show that CCR2 expressing inflammatory monocytes are increased in BM. Interestingly, similar increases are also observed in the spleen and peripheral blood suggesting that there is constant trafficking of myeloid progenitors from BM to the spleen that contribute to monocyte-mediated inflammation in hypertension43. It appears that in hypertension, autonomic modulation of the immune system is altered such that anti-inflammatory cholinergic modulation of the innate immune system becomes pro-inflammatory44. Additionally, sympathetic drive appears to promote hypertension by norepinephrine-mediated T cell activation45. Interestingly, norepinephrine preferentially activates memory T cells to release pro-inflammatory cytokines46, which is particularly important because memory T cells accumulate in the kidney and vasculature of hypertensive animals47. Our data indicate that norepinephrine application into BM increases mobilization of immune cells, and this response is attenuated by application of acetylcholine37. Furthermore, renal denervation has been shown to prevent immune cell activation and reduce renal inflammation in Ang II-induced hypertension48. Therefore, it becomes evident that autonomic regulation of the immune system is not only important, but also altered toward enhancing pro-inflammatory responses in hypertension.

Figure 1. Chronic Ang II-induced hypertension results in increased differentiation and mobilization of inflammatory monocytes in mice.

A and B. The average numbers of CCR2+ inflammatory monocytes (CD11b+, Ly6Chi) were significantly increased in both the BM (A) and spleen (B) of Ang II-infused C57BL6 mice. Saline or Ang II (1000ng·kg−1·min−1) was delivered by subcutaneously implanted osmotic mini-pumps (ALZET) for three weeks and CD11b+, Ly6Chi, CCR2+ monocytes were analyzed from each hind leg (1 femur and 1 tibia) or whole spleen by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. C. CCR2+ inflammatory monocytes were also increased in circulation after 3 weeks of Ang II infusion. Peripheral blood (PB) from above mice was collected and mononuclear cells were separated using Ficoll gradient. These cells were pre-gated on CD11b+ and analyzed for the expression of Ly6C and CCR2. (n=8–10)

Another important aspect to consider is a positive feedback loop, where neuroinflammation contributes to sympathoexcitation, which then promotes activation of the immune system and stem/progenitor cells in BM25. In turn, this can feedback to the brain and exacerbate central inflammation generating a vicious pro-inflammatory cycle25. Using BM-chimeric rats, our group has shown that pro-inflammatory progenitors from BM extravasate and enter the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) to contribute to neuroinflammation in Ang II-induced hypertension5. Additionally, treatment with minocycline, an anti-inflammatory antibiotic, not only attenuates central microglial activation and hypertension, but also decreases the number of BM-derived microglia/macrophages in the PVN. Similar findings in the PVN were reported in a mouse model of chronic stress49, an important risk factor for the development of hypertension. Others have shown the presence of T cell infiltration in the subfornical organ (SFO) during Ang II-induced hypertension50. Taken together, these observations indicate that sympathetic activation has a profound impact on BM pro-inflammatory progenitors, as some of these cells extravasate into the brain, and contribute to neuroinflammation.

The specific mechanisms underlying extravasation of BM cells into the brain remain a subject of extensive investigation. Studies indicate that a CCL2 gradient, leading to its increased concentration in the brain, could be one of these signals5, 49. Additionally, pro-inflammatory Ly6ChiCCR2+ monocytes have been suggested to be the monocyte progenitor responsible for these extravasated cells in the brain51. Although this view has not yet been evaluated in hypertension studies, there is evidence both from our group (Figure 1) and others52 indicating that Ang II-induced hypertension in mice models is associated with elevated Ly6Chi monocytes mostly expressing CCR2. Finally, a “leaky” blood-brain barrier associated with hypertension53 could also contribute to extravasation of BM cells into the brain.

Brain-Gut Communication

The gut enteric nervous system is complex and capable of functioning independent of extrinsic inputs. Communication between this system and the CNS has been extensively reviewed elsewhere54. Therefore, we will focus on the effects of autonomic innervation on immune responses and gut function, as well as the effects of gut microbial factors on the CNS.

Autonomic input to the gut plays an important role in modulating the local immune response55. Norepinephrine and sympathetic nerves are key in regulating lymphocyte migration and accumulation in the gut56. Resident intestinal macrophages are closely regulated by both the vagus nerves57 and sympathetic varicosities58. Vagal nerve stimulation and blocking sympathetic drive prevents breakdown of the intestinal lumen-blood barrier59 and enhances epithelial cell barrier function, respectively60. These observations suggest that both the sympathetic and parasympathetic arms of the autonomic nervous system are important in regulating the gut’s immune response as well as function of the gut epithelial barrier. However, whether intestinal inflammation and barrier permeability are altered in hypertension remains to be determined.

The brain-gut communication appears to be bidirectional where gut microbiota and their products are implicated in sympathetic activation61 that maintains an influx of lymphocytes to intestinal tissue62. This view is supported by evidence from germ-free (GF) mice where lacking gut microbes appear to have a less anxious phenotype in both the “elevated plus maze” and “light dark box” tests63. Relevant to cardiovascular physiology, GF mice also have an exaggerated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress response64, in addition to a disruption of the blood brain barrier65. It is interesting to note that these mice also display global microglial defects66. Taken together with the evidence that microglia homeostasis is regulated by bacterial short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)66, it is tempting to suggest that gut microbiota and its products hold the potential to regulate neural control mechanisms in hypertension.

Intestinal microbiota and hypertension

The gut microbiota has become one of the most active areas of research in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. The human gut microbiota is dominated by Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria phyla67. Recent studies note an association of intestinal dysbiosis with several cardiometabolic diseases, including insulin resistance, obesity, and cardiovascular disease68. Intestinal dysbiosis is an imbalance in the gut microbiota, which may be described by several characteristics, such as a decrease in richness and diversity69, altered representation of bacterial metabolic pathways, and modifications in composition of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes70. In this section, we will highlight some of the tools enabling research in the field of microbiota in cardiometabolic diseases, summarize the link between the intestinal microbiota and hypertension, and draw a conclusion by reviewing the effects of the intestinal microbes on intestinal pathology and immunity.

Microbiota research is enabled by metagenomics, which allows high-resolution and culture-independent sequencing of bacterial DNA using either amplicons sequencing or whole-metagenome shotgun sequencing71. Bioinformatics analysis of sequencing data is usually performed in two ways: first, for taxonomic classification72, and second, for functional profiling by microbial product identification/prediction73. Resulting data provide information on the presence of different species in a microbial population and their potential metabolic functions. However, the involvement of these microbial populations in pathophysiology requires more complex experimental design, such as microbial depletion by antibiotics, or fecal transplantation studies between control and experimentally diseased animals and perhaps fecal transplantation from human samples into GF mice. The latter approach using “humanized” mice has led to important discoveries indicating that gut microbiota modulate metabolism and obesity74. The added benefit of using human intestinal microbiota samples for these experiments is that they may have superior benefits for patients. For example, a recent study indicates that transplants from lean donors to patients with metabolic syndrome led to an increase in the recipient’s insulin sensitivity75.

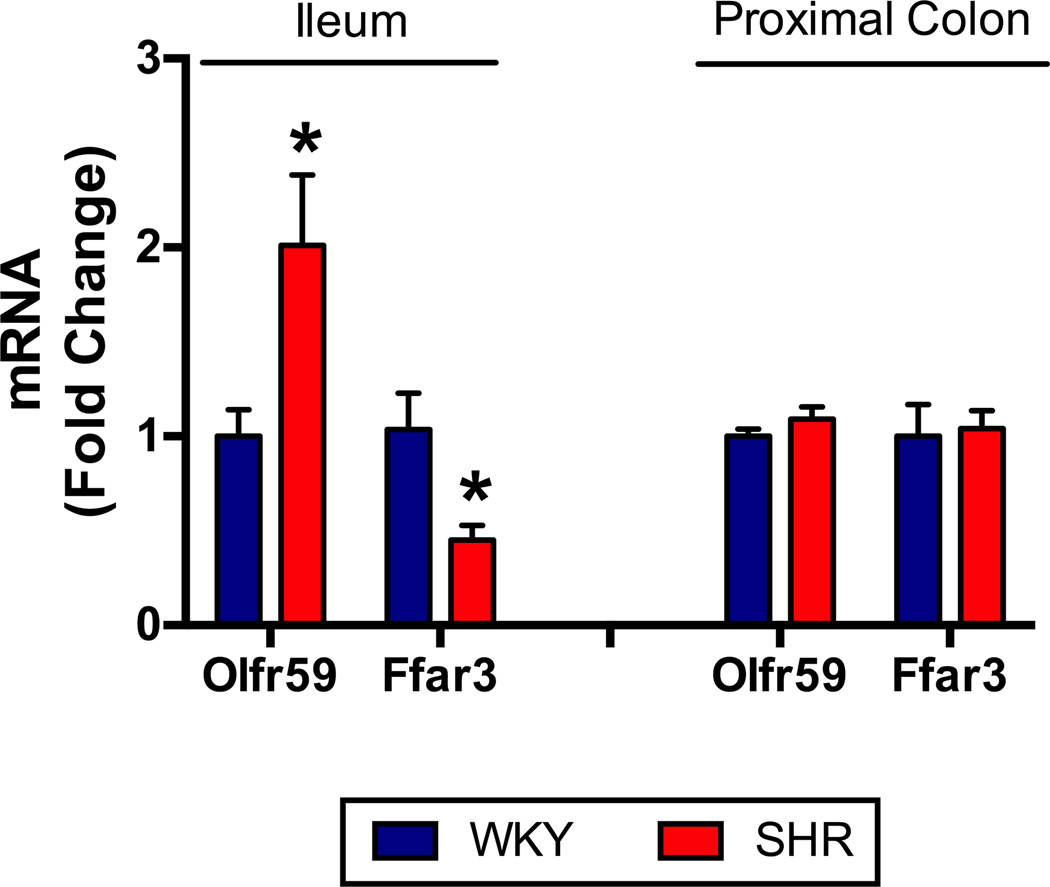

To date, there are limited studies indicating a direct association between gut microbiota and hypertension in both animal models and human disease. Early studies have shown an elevated BP in GF rats by approximately 20mmHg, implicating a role for gut microbiota in BP regulation76–78. Availability of metagenomic technology has accelerated investigation linking hypertension and gut microbiota. The first evidence for such a link was the demonstration that SCFAs modulate BP through the renal and vascular olfactory receptor (Olfr) 78 and G protein-coupled receptor (Gpr) 41 in mice79. These receptors are mutually antagonistic and respond to SCFAs, products of bacterial metabolism found in the circulation80. This is supported by a series of studies using Olfr78 and Gpr41 knockout mice, demonstrating that stimulation of Olfr78 elevates BP, while stimulation of Gpr41 lowers BP. Therefore, we sought to determine whether there were alterations in mRNA expression of the rat orthologs of Olfr78 and Gpr41, namely Olfr59 and free fatty acid receptor 3 (Ffar3), comparing Wistar Kyoto (WKY) and spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) models. Interestingly, we found a two-fold upregulation of Olfr59 in the small intestine accompanied by a 60% down-regulation of Ffar3 (Figure 2). Since Olfr59 elevates BP and Ffar3 opposes this action to lower BP, these data support the suggestion that altered SCFA receptors in the small intestine may play a role in elevated BP of the SHR. Clearly, additional studies are necessary to confirm this conclusion and provide a mechanism for the differential regulation of these SCFA receptors throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

Figure 2. Short-chain fatty-acid receptors involved in blood pressure regulation are altered in the ileum of SHR.

SCFA receptors Olfr59 and Ffar3 are involved in BP regulation, to increase or decrease it, respectively79, 80. Intestinal bacteria are the main source of SCFAs112; therefore, we sought to examine the SCFA receptors in rat intestinal tissue. Ileum and colon tissues were excised for RNA extraction and RT-PCR from 20-week old WKY and SHR, as previously described5 (n=8 per group, MAP WKY: 99±3, MAP SHR: 158±2). We observed an increase in Olfr59 mRNA and a decrease in Ffar3 mRNA in the ileum, but not colon, of SHR.

Two simultaneous studies reported a link between gut microbial composition and hypertension81,82. Employing Dahl rats, Mell et al demonstrated significant differences in cecal microbiota comparing salt-sensitive and salt-resistant strains81. In addition, changes in several SCFAs in plasma following cecal transplantation were observed. They concluded that microbial composition does indeed affect plasma SCFA levels. Our study compared alterations in the fecal microbiota in the SHR and chronic Ang II infusion rat models of hypertension82. We observed a significant dysbiosis as a result of decreases in microbial richness, diversity, evenness, and increased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in hypertensive animals. This dysbiosis was associated with decreased acetate- and butyrate-producing bacterial colonies82. Additionally, we found that the antihypertensive effects of minocycline were associated with beneficial changes in gut microbial composition in Ang II-induced hypertension. It is pertinent to point out that in other studies no significant changes in gut microbiota following L-NAME treatment83 or between WKY and SHR84 were observed. This could be due to a difference in technologies employed, thus underscoring the implementation and importance of adequate and established use of state-of-the-art technology for such studies.

Our study also showed an association of gut dysbiosis with high BP in a small cohort of hypertensive patients82. Recently, we reported a case study where an impressive BP lowering effect was observed in a patient with treatment-resistant hypertension when treated with a combination of antibiotics (vancomycin, rifampin, and ciprofloxacin)85. This patient’s BP decreased from 160/90 mmHg before treatment to 130/60 mmHg following the antibiotic regimen, and the effect persisted for six months after termination of the antibiotics. This prolonged BP response further suggests a possible role for gut microbiota. Collectively, these data suggest a strong association between gut microbial dysbiosis and hypertension pathology.

Gut-Bone Marrow Communication

Gut dysbiosis has been classically associated with increased intestinal inflammation and enhanced barrier permeability in animal models of obesity and diabetes86, 87. Intestinal eubiosis is constantly regulated by maintenance of an intact intestinal barrier88 supported by regulatory T cells89. However, alterations in gut microbiota can cause low-grade inflammation through enhanced leakage of bacterial products such as LPS90, or promote resolution of certain inflammatory responses through other products such as SCFAs91. This low-grade inflammation has the ability to modulate the gut epithelial barrier92 through various mechanisms, including interferon (IFN)-γ93, IL-1094, and myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88)95. Interestingly, enhancing the gut barrier to reduce LPS leakage improves insulin sensitivity in mice96. Additionally, a gut-specific anti-inflammatory agent which targets peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ97, 5-aminosalicylic acid, has been suggested to be beneficial in insulin resistance and obesity by reducing gut permeability, increasing bacterial diversity, and reversing bowel inflammation86. Hence, the question becomes whether these gut pathologies are also observed in the hypertensive state. Future work in the field must determine whether low-grade inflammation and enhanced barrier permeability are present during or preceding hypertension development, and importantly, whether a gut-specific anti-inflammatory agent like 5-aminosalicylic acid would lower BP in hypertensive animal models with gut dysbiosis.

In addition to directly modulating intestinal immunity and barrier function, gut bacteria can affect peripheral immune cells and BM HSPCs. The presence of reduced numbers of myeloid progenitors in both BM and the spleen in GF mice supports this view98. Additionally, Rag1-deficient mice have lower numbers and proportions of HSPCs, an effect which is reversed by fecal transplantation from wild type mice99. In obesity, gut microbiota have been shown to regulate HSPC differentiation by impairing BM niche function100. Therefore, it could be suggested that hypertension, which exhibits gut dysbiosis, is likely to have an impact on BM stem cell niche and HSPC function.

The mechanism by which gut microbiota could modulate the immune system relative to hypertension is an area of active investigation. One possibility is through bacterial products that enter the circulation. For example, SCFAs such as acetate and butyrate have been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects on myeloid cells as well as intestinal epithelial cells101. Through histone deacetylase inhibition, butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function102, while acetate promotes T helper 17 (Th17) cell development103. Th17 cells are modulated by various gut immune and microbial mechanisms, and have been associated with the development of intestinal inflammation104. We recently observed that Th17 cells (CD4+/CD17+) are elevated in hypertensive patients, which is particularly relevant since activation of these cells is regulated by gut-intrinsic mechanisms105, 106. It would be important to determine in future experiments if the increase in these Th17 cells is mediated by gut-derived factors as a results of dysbiosis in hypertension.

Implications for human hypertension

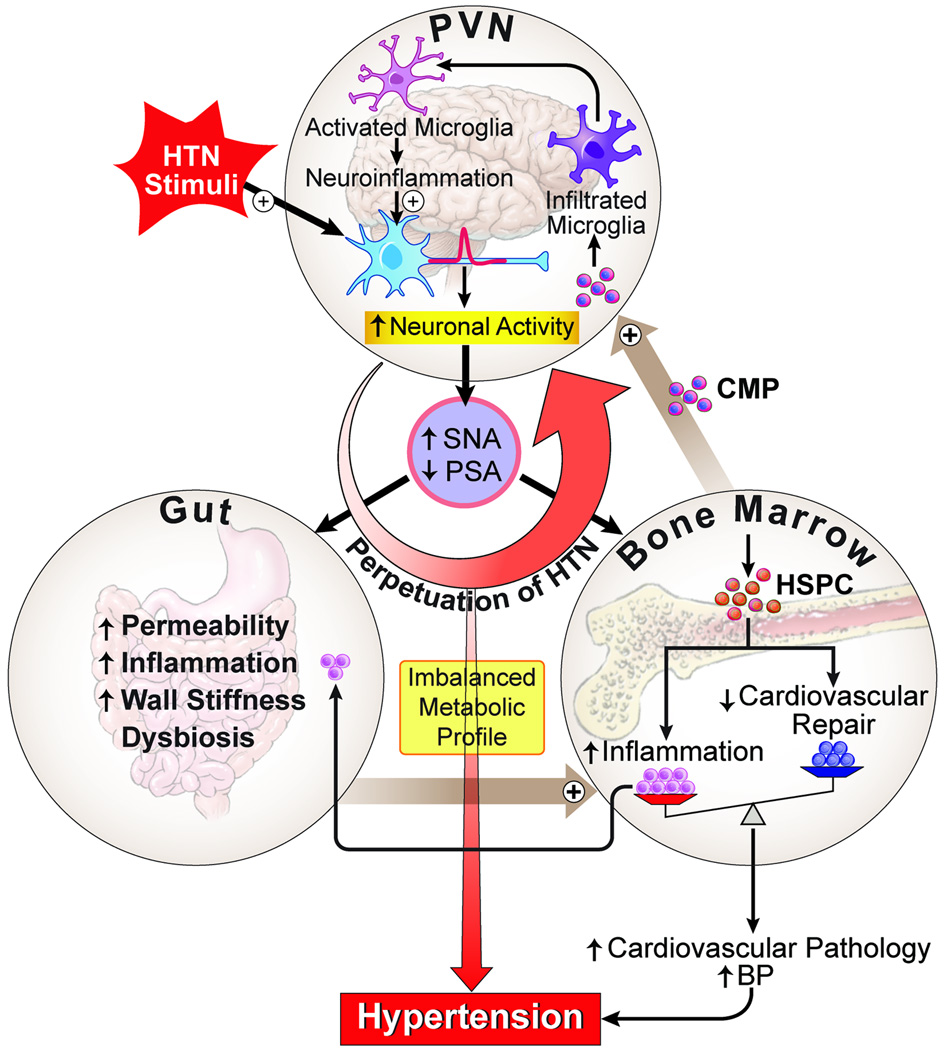

It could be summarized from the above discussion that the brain, BM (immune system), and gut microbiota are potentially intertwined functionally to control BP, and their dysfunctions could be associated with hypertension. Key questions to be addressed are whether there is interplay among these organs in hypertension and if so, what is the contribution of this interplay in the overall hypertensive state? We propose the following “brain-gut-BM” triangular interaction hypothesis (Figure 3). This working hypothesis has been developed by synthesizing available evidence from the literature including our own work. We propose that hypertensive stimuli (such as Ang II, salt, stress, and other hypertension risk factors) trigger autonomic neural pathways resulting in increases in sympathetic and dampening of parasympathetic activities. This directly impacts cardiovascular-relevant organs (such as blood vessels, heart, kidney, etc.) to increase BP. We propose that increases in sympathetic drive to the gut and BM may also set in motion a sequence of signaling events that ultimately contribute to an overall increase of BP and establishment of hypertension. For example, increased SNA to the gut could result in increased gut permeability, gut inflammatory status, and dysbiosis, leading to an imbalance in microbial-derived metabolites in the plasma. These metabolites, working together with elevated sympathetic drive to the BM, may act as modulators for BM cell activity by increasing production and release of myeloid progenitors and other pro-inflammatory cells, and decrease in angiogenic progenitors. This could be a critical event for establishment of hypertension as increases in myeloid progenitors contribute to an overall increase in peripheral inflammation and neuroinflammation by differentiating into brain macrophages/microglia. Decreases in angiogenic cells also can lead to a compromised vascular repair capacity, a hallmark of hypertension. Neuroinflammation-associated increases in cytokines, chemokines, and ROS accentuate autonomic neuronal activity and SNA to the gut and BM, thus perpetuating hypertension. Therefore, although there are multiple factors that cause high BP, we propose that involvement of SNA-mediated gut dysbiosis, BM pro-inflammatory cell activity, and neuroinflammation all play an important role in elevating BP.

Figure 3. Brain-gut-bone marrow axis.

Increases in pro-hypertensive stimuli, such as Ang II, enhance neuronal activity and trigger neuroinflammatory pathways in cardioregulatory brain centers to result in sympathoexcitation. Sympathetic activity to the BM induces mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells, and Ang II stimulates their differentiation into inflammatory cells. These cells may then migrate to the brain to become microglia/macrophages and propagate neuroinflammation, as well as to the gut to contribute to low-grade intestinal inflammation. Sympathetic activity to the gut could modulate motility as well as the local immune response. Finally, the low-grade inflammation of the gut coupled with alterations in the gut microbiota may result in bacterial metabolites entering circulation, where they could negatively affect both brain neuronal activity as well as the BM immune cells. This triangular interaction may play an important role in perpetuating the progression of hypertension and may be critical in the establishment of resistant hypertension.

The concept of gut microbiota impacting BP is novel and represents a paradigm-shift in the hypertension field. However, a number of important gaps in knowledge remain in support of this hypothesis as outlined in Table 1. If proven, this may have great implications for treatment of hypertension with the use of dietary supplements, such as pre- and pro-biotics, as well as appropriate fecal/bacterial transplantation. Some evidence already exists supporting a beneficial role for Lactobacillus probiotics in BP regulation107–109. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of nine randomized trials demonstrated a significant decrease in both systolic and diastolic BP in patients who consumed a daily dose of ≥1011 CFU of probiotics110.

Table 1.

Summary of Gaps in Knowledge in the Brain-Gut-BM Triangular Interaction Hypothesis

| 1) Critical questions for further establishing mechanism and proof of concept |

|

| 2) Clinical/Translational gaps |

|

In summary, evidence in this review emphasizes that gut microbial composition holds the potential for playing an important role in BP control. This field is in its rudimentary stage, at present, and many important questions, as outlined in Table 1, must be addressed before its full clinical and translational potential is recognized. First, a full-scale clinical study must be conducted to confirm dysbiosis in hypertensive patients; second, fecal transplantation studies would be useful in animals to establish the “proof of concept” of the role of gut microbial dysbiosis in hypertension and resistant hypertension; and finally, metabolic profiles of plasma must be conducted in patients to determine if there are bacterial metabolites unique to resistant hypertension.

Supplementary Material

Summary and future directions.

In this review, we have presented a working hypothesis involving the brain, gut, and BM, whose dysfunctional interactions may be critical in persistent neuroinflammation and key in the development and establishment of hypertension. Of course, the story is just beginning and an extensive amount of research must be undertaken, and critical issues addressed, in order to further support, modify, or even refute this hypothesis. Some of these issues are as follows: 1) What are the characteristics of extravasated cells into the brain? Are they all activated microglia? How long do they remain in the brain? What is the role of the spleen in the extravasation of myeloid progenitors? Is there an increase in activated microglia in human hypertension? 2) Is there a unique signature of metabolite(s), such as SCFAs, and/or bacterial DNA in plasma of hypertensive animals and/or patients that could be considered as a marker for early detection? 3) Extensive studies must be conducted to further characterize the autonomic regulation of SNA to the gut and BM. 4) The role of SCFAs, their receptors, and their targets (blood vessels, gut, BM, brain, etc) requires investigation. Answers to these and other related questions entrust optimism towards the development of a novel therapeutic approach for the control of hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL33610, HL56921, HL102033, 5UM1HL087366 and UL1TR001427, and One Florida Clinical Research Consortium CDRN-1501-26692

Non-standard Abbreviations

- ACE

Angiotensin converting enzyme

- AT1R

Angiotensin type 1 receptors

- BP

Blood pressure

- BM

Bone marrow

- CCL2

C-C chemokine ligand 2

- CNS

Central nervous system

- Ffar3

Free fatty acid receptor 3

- Gpr

G protein-coupled receptor

- GF

Germ-free

- HSPC

Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells

- HMGB1

High mobility group box 1

- PVN

Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus

- IFN-γ

Interferon-γ

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1β

- MyD88

Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88

- Olfr

Olfactory receptor

- PPAR-γ

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- RAS

Renin angiotensin system

- SCFAs

Short chain fatty acids

- SHR

Spontaneously hypertensive rats

- SFO

Subfornical organ

- SNA

Sympathetic nerve activity

- Th17

T helper 17 cell

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- WKY

Wistar Kyoto

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MacKenzie TD, Ogedegbe O, Smith SC, Jr, Svetkey LP, Taler SJ, Townsend RR, Wright JT, Jr, Narva AS, Ortiz E. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint national committee (jnc 8) Jama. 2014;311:507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoon SS, Carroll MD, Fryar CD. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United states, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith SM, Pepine CJ, Cooper-DeHoff RM. Reply to ‘resistant hypertension revisited: Definition and true prevalence’. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1547. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waki H, Hendy EB, Hindmarch CC, Gouraud S, Toward M, Kasparov S, Murphy D, Paton JF. Excessive leukotriene b4 in nucleus tractus solitarii is prohypertensive in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2013;61:194–201. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.192252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santisteban MM, Ahmari N, Carvajal JM, Zingler MB, Qi Y, Kim S, Joseph J, Garcia-Pereira F, Johnson RD, Shenoy V, Raizada MK, Zubcevic J. Involvement of bone marrow cells and neuroinflammation in hypertension. Circ Res. 2015;117:178–191. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardinale JP, Sriramula S, Mariappan N, Agarwal D, Francis J. Angiotensin ii-induced hypertension is modulated by nuclear factor-kappabin the paraventricular nucleus. Hypertension. 2012;59:113–121. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.182154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masson GS, Nair AR, Silva Soares PP, Michelini LC, Francis J. Aerobic training normalizes autonomic dysfunction, hmgb1 content, microglia activation and inflammation in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of shr. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H1115–H1122. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00349.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song XA, Jia LL, Cui W, Zhang M, Chen W, Yuan ZY, Guo J, Li HH, Zhu GQ, Liu H, Kang YM. Inhibition of tnf-alpha in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus attenuates hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting neurohormonal excitation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;281:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marc Y, Llorens-Cortes C. The role of the brain renin-angiotensin system in hypertension: Implications for new treatment. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal D, Dange RB, Raizada MK, Francis J. Angiotensin ii causes imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by modulating gsk-3beta in neuronal culture. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:860–874. doi: 10.1111/bph.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sriramula S, Xia H, Xu P, Lazartigues E. Brain-targeted angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 overexpression attenuates neurogenic hypertension by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-mediated inflammation. Hypertension. 2015;65:577–586. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia H, Sriramula S, Chhabra KH, Lazartigues E. Brain angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 shedding contributes to the development of neurogenic hypertension. Circ Res. 2013;113:1087–1096. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi P, Grobe JL, Desland FA, Zhou G, Shen XZ, Shan Z, Liu M, Raizada MK, Sumners C. Direct pro-inflammatory effects of prorenin on microglia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue B, Thunhorst RL, Yu Y, Guo F, Beltz TG, Felder RB, Johnson AK. Central renin-angiotensin system activation and inflammation induced by high-fat diet sensitize angiotensin ii-elicited hypertension. Hypertension. 2015 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei SG, Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Felder RB. Proinflammatory cytokines upregulate sympathoexcitatory mechanisms in the subfornical organ of the rat. Hypertension. 2015;65:1126–1133. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.05112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sriramula S, Cardinale JP, Francis J. Inhibition of tnf in the brain reverses alterations in ras components and attenuates angiotensin ii-induced hypertension. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei SG, Zhang ZH, Beltz TG, Yu Y, Johnson AK, Felder RB. Subfornical organ mediates sympathetic and hemodynamic responses to blood-borne proinflammatory cytokines. Hypertension. 2013;62:118–125. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Kloet AD, Liu M, Rodriguez V, Krause EG, Sumners C. Role of neurons and glia in the cns actions of the renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular control. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;309:R444–R458. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00078.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kettenmann H, Kirchhoff F, Verkhratsky A. Microglia: New roles for the synaptic stripper. Neuron. 2013;77:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi P, Diez-Freire C, Jun JY, Qi Y, Katovich MJ, Li Q, Sriramula S, Francis J, Sumners C, Raizada MK. Brain microglial cytokines in neurogenic hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;56:297–303. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen XZ, Li Y, Li L, Shah KH, Bernstein KE, Lyden P, Shi P. Microglia participate in neurogenic regulation of hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;66:309–316. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pannell M, Szulzewsky F, Matyash V, Wolf SA, Kettenmann H. The subpopulation of microglia sensitive to neurotransmitters/neurohormones is modulated by stimulation with lps, interferon-gamma, and il-4. Glia. 2014;62:667–679. doi: 10.1002/glia.22633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez-Perez AI, Borrajo A, Rodriguez-Pallares J, Guerra MJ, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Interaction between nadph-oxidase and rho-kinase in angiotensin ii-induced microglial activation. Glia. 2015;63:466–482. doi: 10.1002/glia.22765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyoshi M, Miyano K, Moriyama N, Taniguchi M, Watanabe T. Angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonist inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced stimulation of rat microglial cells by suppressing nuclear factor kappab and activator protein-1 activation. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:343–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.06014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young CN, Davisson RL. Angiotensin-ii, the brain, and hypertension: An update. Hypertension. 2015;66:920–926. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.03624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katayama Y, Battista M, Kao WM, Hidalgo A, Peired AJ, Thomas SA, Frenette PS. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124:407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanoun M, Maryanovich M, Arnal-Estape A, Frenette PS. Neural regulation of hematopoiesis, inflammation, and cancer. Neuron. 2015;86:360–373. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452:442–447. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afan AM, Broome CS, Nicholls SE, Whetton AD, Miyan JA. Bone marrow innervation regulates cellular retention in the murine haemopoietic system. Br J Haematol. 1997;98:569–577. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.2733092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spiegel A, Shivtiel S, Kalinkovich A, Ludin A, Netzer N, Goichberg P, Azaria Y, Resnick I, Hardan I, Ben-Hur H, Nagler A, Rubinstein M, Lapidot T. Catecholaminergic neurotransmitters regulate migration and repopulation of immature human cd34+ cells through wnt signaling. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1123–1131. doi: 10.1038/ni1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amadesi S, Reni C, Katare R, Meloni M, Oikawa A, Beltrami AP, Avolio E, Cesselli D, Fortunato O, Spinetti G, Ascione R, Cangiano E, Valgimigli M, Hunt SP, Emanueli C, Madeddu P. Role for substance p-based nociceptive signaling in progenitor cell activation and angiogenesis during ischemia in mice and in human subjects. Circulation. 2012;125:1774–1786. S1771–S1719. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.089763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dang Z, Maselli D, Spinetti G, Sangalli E, Carnelli F, Rosa F, Seganfreddo E, Canal F, Furlan A, Paccagnella A, Paiola E, Lorusso B, Specchia C, Albiero M, Cappellari R, Avogaro A, Falco A, Quaini F, Ou K, Rodriguez-Arabaolaza I, Emanueli C, Sambataro M, Fadini GP, Madeddu P. Sensory neuropathy hampers nociception-mediated bone marrow stem cell release in mice and patients with diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015;58:2653–2662. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3735-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lucas D, Bruns I, Battista M, Mendez-Ferrer S, Magnon C, Kunisaki Y, Frenette PS. Norepinephrine reuptake inhibition promotes mobilization in mice: Potential impact to rescue low stem cell yields. Blood. 2012;119:3962–3965. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-367102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dutta P, Courties G, Wei Y, Leuschner F, Gorbatov R, Robbins CS, Iwamoto Y, Thompson B, Carlson AL, Heidt T, Majmudar MD, Lasitschka F, Etzrodt M, Waterman P, Waring MT, Chicoine AT, van der Laan AM, Niessen HW, Piek JJ, Rubin BB, Butany J, Stone JR, Katus HA, Murphy SA, Morrow DA, Sabatine MS, Vinegoni C, Moskowitz MA, Pittet MJ, Libby P, Lin CP, Swirski FK, Weissleder R, Nahrendorf M. Myocardial infarction accelerates atherosclerosis. Nature. 2012;487:325–329. doi: 10.1038/nature11260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Courties G, Herisson F, Sager HB, Heidt T, Ye Y, Wei Y, Sun Y, Severe N, Dutta P, Scharff J, Scadden DT, Weissleder R, Swirski FK, Moskowitz MA, Nahrendorf M. Ischemic stroke activates hematopoietic bone marrow stem cells. Circ Res. 2015;116:407–417. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutta P, Sager HB, Stengel KR, Naxerova K, Courties G, Saez B, Silberstein L, Heidt T, Sebas M, Sun Y, Wojtkiewicz G, Feruglio PF, King K, Baker JN, van der Laan AM, Borodovsky A, Fitzgerald K, Hulsmans M, Hoyer F, Iwamoto Y, Vinegoni C, Brown D, Di Carli M, Libby P, Hiebert SW, Scadden DT, Swirski FK, Weissleder R, Nahrendorf M. Myocardial infarction activates ccr2(+) hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zubcevic J, Jun JY, Kim S, Perez PD, Afzal A, Shan Z, Li W, Santisteban MM, Yuan W, Febo M, Mocco J, Feng Y, Scott E, Baekey DM, Raizada MK. Altered inflammatory response is associated with an impaired autonomic input to the bone marrow in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 2014;63:542–550. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S, Zingler M, Harrison JK, Scott EW, Cogle CR, Luo D, Raizada MK. Angiotensin ii regulation of proliferation, differentiation, and engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells. Hypertension. 2016 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheiermann C, Kunisaki Y, Frenette PS. Circadian control of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:190–198. doi: 10.1038/nri3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheiermann C, Kunisaki Y, Lucas D, Chow A, Jang JE, Zhang D, Hashimoto D, Merad M, Frenette PS. Adrenergic nerves govern circadian leukocyte recruitment to tissues. Immunity. 2012;37:290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellinger DL, Lorton D. Autonomic regulation of cellular immune function. Auton Neurosci. 2014;182:15–41. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ganta CK, Lu N, Helwig BG, Blecha F, Ganta RR, Zheng L, Ross CR, Musch TI, Fels RJ, Kenney MJ. Central angiotensin ii-enhanced splenic cytokine gene expression is mediated by the sympathetic nervous system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1683–H1691. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00125.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, Wildgruber M, Cortez-Retamozo V, Panizzi P, Figueiredo JL, Kohler RH, Chudnovskiy A, Waterman P, Aikawa E, Mempel TR, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325:612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harwani SC, Chapleau MW, Legge KL, Ballas ZK, Abboud FM. Neurohormonal modulation of the innate immune system is proinflammatory in the prehypertensive spontaneously hypertensive rat, a genetic model of essential hypertension. Circ Res. 2012;111:1190–1197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.277475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, McCann LA, Weyand C, Gordon FJ, Harrison DG. Central and peripheral mechanisms of t-lymphocyte activation and vascular inflammation produced by angiotensin ii-induced hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;107:263–270. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slota C, Shi A, Chen G, Bevans M, Weng NP. Norepinephrine preferentially modulates memory cd8 t cell function inducing inflammatory cytokine production and reducing proliferation in response to activation. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;46:168–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trott DW, Thabet SR, Kirabo A, Saleh MA, Itani H, Norlander AE, Wu J, Goldstein A, Arendshorst WJ, Madhur MS, Chen W, Li CI, Shyr Y, Harrison DG. Oligoclonal cd8+ t cells play a critical role in the development of hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;64:1108–1115. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao L, Kirabo A, Wu J, Saleh MA, Zhu L, Wang F, Takahashi T, Loperena R, Foss JD, Mernaugh RL, Chen W, Roberts J, 2nd, Osborn JW, Itani HA, Harrison DG. Renal denervation prevents immune cell activation and renal inflammation in angiotensin ii-induced hypertension. Circ Res. 2015;117:547–557. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ataka K, Asakawa A, Nagaishi K, Kaimoto K, Sawada A, Hayakawa Y, Tatezawa R, Inui A, Fujimiya M. Bone marrow-derived microglia infiltrate into the paraventricular nucleus of chronic psychological stress-loaded mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pollow DP, Uhrlaub J, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Sandberg K, Nikolich-Zugich J, Brooks HL, Hay M. Sex differences in t-lymphocyte tissue infiltration and development of angiotensin ii hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;64:384–390. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mildner A, Schmidt H, Nitsche M, Merkler D, Hanisch UK, Mack M, Heikenwalder M, Bruck W, Priller J, Prinz M. Microglia in the adult brain arise from ly-6chiccr2+ monocytes only under defined host conditions. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1544–1553. doi: 10.1038/nn2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore JP, Vinh A, Tuck KL, Sakkal S, Krishnan SM, Chan CT, Lieu M, Samuel CS, Diep H, Kemp-Harper BK, Tare M, Ricardo SD, Guzik TJ, Sobey CG, Drummond GR. M2 macrophage accumulation in the aortic wall during angiotensin ii infusion in mice is associated with fibrosis, elastin loss, and elevated blood pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H906–H917. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00821.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Biancardi VC, Son SJ, Ahmadi S, Filosa JA, Stern JE. Circulating angiotensin ii gains access to the hypothalamus and brain stem during hypertension via breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. Hypertension. 2014;63:572–579. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharkey KA, Savidge TC. Role of enteric neurotransmission in host defense and protection of the gastrointestinal tract. Auton Neurosci. 2014;181:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Straub RH, Wiest R, Strauch UG, Harle P, Scholmerich J. The role of the sympathetic nervous system in intestinal inflammation. Gut. 2006;55:1640–1649. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.091322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gonzalez-Ariki S, Husband AJ. The role of sympathetic innervation of the gut in regulating mucosal immune responses. Brain Behav Immun. 1998;12:53–63. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1997.0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matteoli G, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Nemethova A, Di Giovangiulio M, Cailotto C, van Bree SH, Michel K, Tracey KJ, Schemann M, Boesmans W, Vanden Berghe P, Boeckxstaens GE. A distinct vagal anti-inflammatory pathway modulates intestinal muscularis resident macrophages independent of the spleen. Gut. 2013 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Phillips RJ, Powley TL. Macrophages associated with the intrinsic and extrinsic autonomic innervation of the rat gastrointestinal tract. Auton Neurosci. 2012;169:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krzyzaniak M, Peterson C, Loomis W, Hageny AM, Wolf P, Reys L, Putnam J, Eliceiri B, Baird A, Bansal V, Coimbra R. Postinjury vagal nerve stimulation protects against intestinal epithelial barrier breakdown. J Trauma. 2011;70:1168–1175. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318216f754. discussion 1175–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schaper J, Wagner A, Enigk F, Brell B, Mousa SA, Habazettl H, Schafer M. Regional sympathetic blockade attenuates activation of intestinal macrophages and reduces gut barrier failure. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:134–142. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182784c93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palsson J, Ricksten SE, Delle M, Lundin S. Changes in renal sympathetic nerve activity during experimental septic and endotoxin shock in conscious rats. Circ Shock. 1988;24:133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Straub RH, Pongratz G, Weidler C, Linde HJ, Kirschning CJ, Gluck T, Scholmerich J, Falk W. Ablation of the sympathetic nervous system decreases gram-negative and increases gram-positive bacterial dissemination: Key roles for tumor necrosis factor/phagocytes and interleukin-4/lymphocytes. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:560–572. doi: 10.1086/432134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Diaz Heijtz R, Wang S, Anuar F, Qian Y, Bjorkholm B, Samuelsson A, Hibberd ML, Forssberg H, Pettersson S. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3047–3052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sudo N, Chida Y, Aiba Y, Sonoda J, Oyama N, Yu XN, Kubo C, Koga Y. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J Physiol. 2004;558:263–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Braniste V, Al-Asmakh M, Kowal C, Anuar F, Abbaspour A, Toth M, Korecka A, Bakocevic N, Ng LG, Kundu P, Gulyas B, Halldin C, Hultenby K, Nilsson H, Hebert H, Volpe BT, Diamond B, Pettersson S. The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:263ra158. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Erny D, Hrabe de Angelis AL, Jaitin D, Wieghofer P, Staszewski O, David E, Keren-Shaul H, Mahlakoiv T, Jakobshagen K, Buch T, Schwierzeck V, Utermohlen O, Chun E, Garrett WS, McCoy KD, Diefenbach A, Staeheli P, Stecher B, Amit I, Prinz M. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the cns. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:965–977. doi: 10.1038/nn.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, Mende DR, Li J, Xu J, Li S, Li D, Cao J, Wang B, Liang H, Zheng H, Xie Y, Tap J, Lepage P, Bertalan M, Batto JM, Hansen T, Le Paslier D, Linneberg A, Nielsen HB, Pelletier E, Renault P, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Turner K, Zhu H, Yu C, Jian M, Zhou Y, Li Y, Zhang X, Qin N, Yang H, Wang J, Brunak S, Dore J, Guarner F, Kristiansen K, Pedersen O, Parkhill J, Weissenbach J, Bork P, Ehrlich SD. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tremaroli V, Backhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. 2012;489:242–249. doi: 10.1038/nature11552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Turnbaugh PJ, Gordon JI. The core gut microbiome, energy balance and obesity. J Physiol. 2009;587:4153–4158. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mariat D, Firmesse O, Levenez F, Guimaraes V, Sokol H, Dore J, Corthier G, Furet JP. The firmicutes/bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Franzosa EA, Hsu T, Sirota-Madi A, Shafquat A, Abu-Ali G, Morgan XC, Huttenhower C. Sequencing and beyond: Integrating molecular ‘omics’ for microbial community profiling. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:360–372. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. Qiime allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Joice R, Yasuda K, Shafquat A, Morgan XC, Huttenhower C. Determining microbial products and identifying molecular targets in the human microbiome. Cell Metab. 2014;20:731–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ridaura VK, Faith JJ, Rey FE, Cheng J, Duncan AE, Kau AL, Griffin NW, Lombard V, Henrissat B, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Ilkayeva O, Semenkovich CF, Funai K, Hayashi DK, Lyle BJ, Martini MC, Ursell LK, Clemente JC, Van Treuren W, Walters WA, Knight R, Newgard CB, Heath AC, Gordon JI. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;341:1241214. doi: 10.1126/science.1241214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vrieze A, Van Nood E, Holleman F, Salojarvi J, Kootte RS, Bartelsman JF, Dallinga-Thie GM, Ackermans MT, Serlie MJ, Oozeer R, Derrien M, Druesne A, Van Hylckama Vlieg JE, Bloks VW, Groen AK, Heilig HG, Zoetendal EG, Stroes ES, de Vos WM, Hoekstra JB, Nieuwdorp M. Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:913–916. e917. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zweifach BW, Gordon HA, Wagner M, Reyniers JA. Irreversible hemorrhagic shock in germfree rats. J Exp Med. 1958;107:437–450. doi: 10.1084/jem.107.3.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baez S, Gordon HA. Tone and reactivity of vascular smooth muscle in germfree rat mesentery. J Exp Med. 1971;134:846–856. doi: 10.1084/jem.134.4.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Honour J. The possible involvement of intestinal bacteria in steroidal hypertension. Endocrinology. 1982;110:285–287. doi: 10.1210/endo-110-1-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pluznick JL, Protzko RJ, Gevorgyan H, Peterlin Z, Sipos A, Han J, Brunet I, Wan LX, Rey F, Wang T, Firestein SJ, Yanagisawa M, Gordon JI, Eichmann A, Peti-Peterdi J, Caplan MJ. Olfactory receptor responding to gut microbiota-derived signals plays a role in renin secretion and blood pressure regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4410–4415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215927110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pluznick J. A novel scfa receptor, the microbiota, and blood pressure regulation. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:202–207. doi: 10.4161/gmic.27492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mell B, Jala VR, Mathew AV, Byun J, Waghulde H, Zhang Y, Haribabu B, Vijay-Kumar M, Pennathur S, Joe B. Evidence for a link between gut microbiota and hypertension in the dahl rat. Physiol Genomics. 2015;47:187–197. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00136.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang T, Santisteban MM, Rodriguez V, Li E, Ahmari N, Carvajal JM, Zadeh M, Gong M, Qi Y, Zubcevic J, Sahay B, Pepine CJ, Raizada MK, Mohamadzadeh M. Gut dysbiosis is linked to hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;65:1331–1340. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xu J, Ahren IL, Prykhodko O, Olsson C, Ahrne S, Molin G. Intake of blueberry fermented by lactobacillus plantarum affects the gut microbiota of l-name treated rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:809128. doi: 10.1155/2013/809128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Petriz BA, Castro AP, Almeida JA, Gomes CP, Fernandes GR, Kruger RH, Pereira RW, Franco OL. Exercise induction of gut microbiota modifications in obese, non-obese and hypertensive rats. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:511. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Qi Y, Aranda JM, Rodriguez V, Raizada MK, Pepine CJ. Impact of antibiotics on arterial blood pressure in a patient with resistant hypertension - a case report. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:157–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Luck H, Tsai S, Chung J, Clemente-Casares X, Ghazarian M, Revelo XS, Lei H, Luk CT, Shi SY, Surendra A, Copeland JK, Ahn J, Prescott D, Rasmussen BA, Chng MH, Engleman EG, Girardin SE, Lam TK, Croitoru K, Dunn S, Philpott DJ, Guttman DS, Woo M, Winer S, Winer DA. Regulation of obesity-related insulin resistance with gut anti-inflammatory agents. Cell Metab. 2015;21:527–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, Burcelin R. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57:1470–1481. doi: 10.2337/db07-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brown EM, Sadarangani M, Finlay BB. The role of the immune system in governing host-microbe interactions in the intestine. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:660–667. doi: 10.1038/ni.2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cong Y, Feng T, Fujihashi K, Schoeb TR, Elson CO. A dominant, coordinated t regulatory cell-iga response to the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19256–19261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812681106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Tuohy KM, Chabo C, Waget A, Delmee E, Cousin B, Sulpice T, Chamontin B, Ferrieres J, Tanti JF, Gibson GR, Casteilla L, Delzenne NM, Alessi MC, Burcelin R. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, Kranich J, Sierro F, Yu D, Schilter HC, Rolph MS, Mackay F, Artis D, Xavier RJ, Teixeira MM, Mackay CR. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor gpr43. Nature. 2009;461:1282–1286. doi: 10.1038/nature08530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pastorelli L, De Salvo C, Mercado JR, Vecchi M, Pizarro TT. Central role of the gut epithelial barrier in the pathogenesis of chronic intestinal inflammation: Lessons learned from animal models and human genetics. Front Immunol. 2013;4:280. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Beaurepaire C, Smyth D, McKay DM. Interferon-gamma regulation of intestinal epithelial permeability. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:133–144. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hasnain SZ, Tauro S, Das I, Tong H, Chen AC, Jeffery PL, McDonald V, Florin TH, McGuckin MA. Il-10 promotes production of intestinal mucus by suppressing protein misfolding and endoplasmic reticulum stress in goblet cells. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:357–368. e359. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Everard A, Geurts L, Caesar R, Van Hul M, Matamoros S, Duparc T, Denis RG, Cochez P, Pierard F, Castel J, Bindels LB, Plovier H, Robine S, Muccioli GG, Renauld JC, Dumoutier L, Delzenne NM, Luquet S, Backhed F, Cani PD. Intestinal epithelial myd88 is a sensor switching host metabolism towards obesity according to nutritional status. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5648. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang X, Ota N, Manzanillo P, Kates L, Zavala-Solorio J, Eidenschenk C, Zhang J, Lesch J, Lee WP, Ross J, Diehl L, van Bruggen N, Kolumam G, Ouyang W. Interleukin-22 alleviates metabolic disorders and restores mucosal immunity in diabetes. Nature. 2014;514:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature13564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rousseaux C, Lefebvre B, Dubuquoy L, Lefebvre P, Romano O, Auwerx J, Metzger D, Wahli W, Desvergne B, Naccari GC, Chavatte P, Farce A, Bulois P, Cortot A, Colombel JF, Desreumaux P. Intestinal antiinflammatory effect of 5-aminosalicylic acid is dependent on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1205–1215. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Khosravi A, Yanez A, Price JG, Chow A, Merad M, Goodridge HS, Mazmanian SK. Gut microbiota promote hematopoiesis to control bacterial infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kwon O, Lee S, Kim JH, Kim H, Lee SW. Altered gut microbiota composition in rag1-deficient mice contributes to modulating homeostasis of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Immune Netw. 2015;15:252–259. doi: 10.4110/in.2015.15.5.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Luo Y, Chen GL, Hannemann N, Ipseiz N, Kronke G, Bauerle T, Munos L, Wirtz S, Schett G, Bozec A. Microbiota from obese mice regulate hematopoietic stem cell differentiation by altering the bone niche. Cell Metab. 2015;22:886–894. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Iraporda C, Errea A, Romanin DE, Cayet D, Pereyra E, Pignataro O, Sirard JC, Garrote GL, Abraham AG, Rumbo M. Lactate and short chain fatty acids produced by microbial fermentation downregulate proinflammatory responses in intestinal epithelial cells and myeloid cells. Immunobiology. 2015;220:1161–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chang PV, Hao L, Offermanns S, Medzhitov R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:2247–2252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322269111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Park J, Kim M, Kang SG, Jannasch AH, Cooper B, Patterson J, Kim CH. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory t cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mtor-s6k pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:80–93. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kayama H, Takeda K. Functions of innate immune cells and commensal bacteria in gut homeostasis. J Biochem. 2015 doi: 10.1093/jb/mvv119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim S, Rodriguez V, Santisteban M, Yang T, Qi Y, Raizada M, Pepine C. 6b.07: Hypertensive patients exhibit gut microbial dysbiosis and an increase in th17 cells. J Hypertens. 2015;33(Suppl 1):e77–e78. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kleinewietfeld M, Manzel A, Titze J, Kvakan H, Yosef N, Linker RA, Muller DN, Hafler DA. Sodium chloride drives autoimmune disease by the induction of pathogenic th17 cells. Nature. 2013;496:518–522. doi: 10.1038/nature11868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kawase M, Hashimoto H, Hosoda M, Morita H, Hosono A. Effect of administration of fermented milk containing whey protein concentrate to rats and healthy men on serum lipids and blood pressure. J Dairy Sci. 2000;83:255–263. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)74872-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tanida M, Yamano T, Maeda K, Okumura N, Fukushima Y, Nagai K. Effects of intraduodenal injection of lactobacillus johnsonii la1 on renal sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in urethane-anesthetized rats. Neurosci Lett. 2005;389:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gomez-Guzman M, Toral M, Romero M, Jimenez R, Galindo P, Sanchez M, Zarzuelo MJ, Olivares M, Galvez J, Duarte J. Antihypertensive effects of probiotics lactobacillus strains in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015 doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Khalesi S, Sun J, Buys N, Jayasinghe R. Effect of probiotics on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Hypertension. 2014;64:897–903. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.