Abstract

Objective

Report the prevalence of favorable growth patterns including healthy weight maintenance (HWM) and return to healthy weight (RHW) among US school-age children.

Methods

A longitudinal analysis of childhood growth patterns from the ECLS-Kindergarten cohort was completed (n=9,416). The primary outcome included describing the prevalence of HWM/RHW patterns using consecutive child growth data from K-5th grades. Multivariate logistic regression was used to explore predictors of HWM/RHW. Incidence of RHW is calculated by grade level.

Results

Seventy percent (n=6617) of children enter kindergarten at a healthy weight and approximately 70% maintained a healthy weight through 5th grade. Among overweight/obese kindergartners, only 17.1% outgrew their weight risk (RHW) by 5th grade.

Conclusions

Fewer than 1 in 5 at-risk children outgrow their weight risk during school-age yet a majority of healthy weight children can maintain healthy weight during a critical growth period. Future work should explore additional socio-ecologic factors associated with favorable growth.

Keywords: Obesity resilience, growth patterns, favorable growth, healthy weight, health disparities, school-age

Background

Although increased attention to the incidence and prevalence of pediatric obesity have informed predictors for disease,1–5 few studies have informed what factors may predict a child’s ability to remain at or return to a healthy weight. Consideration of those unaffected by disease has historically yielded meaningful insights into disease physiology6,7–10 thereby suggesting that a focus on children able to maintain a healthy weight during the pediatric obesity epidemic is worthy of study. Furthermore, despite a growing body of evidence that delineates the importance of early childhood weight in predicting long-term weight outcomes,11–14 expectations that most young children will “outgrow” being overweight or obese and are highly prevalent.15–18

Interestingly, the frequency by which children outgrow their obese status in later childhood has infrequently been reported. Prior studies have described children returning to healthy weight (5%) in a limited sample of children with psychiatric illness over an eight year observational period.19 Among adolescents, Nonemaker et. al described the prevalence (8%) of a “low risk” for obesity trajectory when youth were followed into adulthood but a description of their earlier life trajectory in the context of their later risk was not reported.1 Though these studies are helpful and reveal the infrequent prevalence of favorable growth patterns among two populations, a description of the prevalence of return to healthy weight among a diverse sample of young children is a necessary epidemiologic piece to address prevailing growth misperceptions20 that may pose barriers promoting early behavior change. Thus, an examination of factors relating to healthy weight maintenance (HWM) and return to healthy weight (RHW) may provide novel insights into the pediatric obesity epidemic.

The concept of “resilience” to a disease state has received increased attention secondary to the observation that not all at-risk individuals are pre-destined for adverse outcomes. The study of resilience is concerned with individual variations in response to risk and underlines the need to assess interactions between risk factors and protective factors in addressing health issues.21 Because racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities are substantial in pediatric obesity prevalence,22, 23 an understanding of factors that may promote resilience to obesity as manifested by patterns like HWM or RHW, among at-risk populations would be critical. In a population of disadvantaged minority women, Ball et. al determined that younger age, higher education and higher income promoted resilience to obesity.24 Though the factors analyzed in this context of “resilience” may be considered immutable factors that may not be behaviorally modified, such unique epidemiologic patterns are often initially described in this manner4, 23, 25–26 with additional socio-ecologic factors (i.e. behaviors, environment, physiologic) later introduced. A similar descriptive analysis of resilience in a diverse population of young children would be of great value, however, robust longitudinal samples including racially/ethnically diverse groups such as Hispanic and Asian children have been limited.

The primary objective of this study is to report the prevalence of patterns that may reflect obesity resilience (HWM and RHW) during the pre-pubertal school age. By using a diverse, nationally representative sample of 5–11 year old US children, we examine the frequency of these growth patterns and determine whether these patterns vary by child age, race/ethnicity and parental socio-economic status. We hypothesize that child starting kindergarten as overweight or obese will infrequently be able to return to healthy weight by later school age whereas children who initiate school at a healthy weight will demonstrate the greatest likelihood of maintaining their weight at later school age. This focused, descriptive approach will serve to gain a preliminary understanding of these patterns by which additional work can continue to explore the socio-ecologic factors related to these patterns. Prior longitudinal studies1, 5, 19 have described trajectories relative to the development of overweight or obesity but have not explicitly reported the prevalence or incidence of these HWM or RHW patterns in a diverse, national sample of children. This analysis provides a valuable opportunity to describe individual differences that may pertain to obesity resilience.

Methods

Study Population

The study examined data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K), a nationally representative sample of 21,260 U.S. children designed and conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). The multi-stage probability sampling design included counties/groups of counties as the primary sampling units, schools within the counties as secondary sampling units and students within schools as tertiary sampling units.27 We excluded children in the final data collection wave (spring, 8th grade) to reduce the likelihood of pubertal changes from confounding growth estimates. Participants with study assessments during kindergarten through 5th grades were identified (Kindergarten Spring 1999, 1st grade Spring 2000, 3rd grade Spring 2002, 5th grade Spring 2004; n=10,673).

We further identified children within this subset who had complete height and weight measurements in all four data collection waves of interest (n=9,657). A comparison of age, gender, race/ethnicity, SES and weight status at baseline in the sample of children with complete anthropomorphic data with the original sample was completed. This analysis revealed similar distributions of all variables in the two samples with the exception of 1% fewer Hispanic children in the analytic sample suggesting that our analytic subsample was representative of the larger sample. In light of these results and in consideration of the low percentage of missingness for height/weight (<4%), we did not elect to impute missing data as it would have offered little advantage; an analytic approach recently described by Cumming.28 Additionally, children with biologically implausible height/weight measurements in this group were excluded (e.g. children who had a height decrease >2 cm on subsequent waves and children with weight gain >20 lbs. per study year). This excluded 241 participants with a final analytic sample of 9,416 children. The recommended ECLS-K sample weight, which accounts for missing data and oversampling, was used in all descriptive and regression analyses.

Variables including age, gender, race/ethnicity and socio-economic status were selected as key variables by which to describe school-age growth patterns. Oversampling of Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander children was achieved with subsequent sample weights provided to account for participant selection and for the effects of non-responders.27 Based on parent report, children were categorized as: Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian and Other Race (includes children of more than one race, Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, and American Indians/Alaskan Natives. Socioeconomic quintiles were collapsed into three categories for the multivariate regression analysis (Highest quintile=High Income, Quintiles 2–3: Middle Income, Quintiles 4–5: Low Income). This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Evaluation of Data

At each data collection wave, two measurements of both child height and weight were taken with the average of the measures reported. ECLS-K staff measured child height and weight using the Shorr Board for height and a digital scale for weight. Age-gender specific BMI were calculated using measured height/weight with Epi Info 3.5 software.29 Child BMI was then used to classify children into key weight categories: underweight (<5th percentile), healthy weight (≥5th percentile to <85th percentile), overweight (≥85th BMI <95th percentile) and obese (BMI≥95th).30 The latter two categories were combined into an “at-risk” category for the purposes of describing growth patterns. Child BMI classification was conducted for each of the 4 data collection waves such that each participant contributed 4 distinct BMI assessments over the study period.

We first explored all variable weight category transitions exhibited by participants in a manner similar to other studies investigating weight change over time using the ECLS-K dataset.31–32 Details of all growth patterns identified in this first stage of analysis are provided (Appendix 1). We then began our focused analysis of obesity resilient patterns including healthy weight maintenance (HWM) and return to healthy weight (RHW) that were defined in the following manner:

Healthy Weight Maintenance (HWM): Healthy weight at all 4 waves (BMI ≥5th to <85th percentile)

Return to Healthy Weight (RHW): Overweight in prior wave (BMI ≥85th percentile) with subsequent transition to healthy weight (BMI ≥5th to <85th percentile)

Because we were specifically interested in these two mutually-exclusive groups based on weight status in four different waves to reflect resilience, we did not use trajectory analysis for our prevalence estimation. This strategy of defining unique growth patterns to understand epidemiologic trends has been used successfully in previous studies.31–33 Thus, our prevalence estimates were completed such that participants demonstrating HWM (as defined above) were compared to participants who started within the cohort at healthy weight and later transitioned to becoming at-risk (Appendix 1, Healthy Weight Overweight group, HWOW). Similarly, participants demonstrating the RHW were compared to children who remained at-risk in all four waves (Appendix 1, At-risk Maintenance group, ARM). Overweight/Obese children were classified as “returning to healthy weight” after demonstrating 2 or more data points in healthy weight category to promote and understanding of a sustained growth pattern versus one that was transitory. We described the baseline prevalence of growth patterns as well as the prevalence of growth patterns observed over the five year study period.

Statistical analyses

As with prior weight prevalence reports,3, 26 we stratified our growth pattern prevalence according to gender, race/ethnicity and by socio-economic tiers to best understand growth patterns. Logistic regression models, accounting for the multilevel design of ECLS-K, were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for the associations between covariates and HWM or RHW growth patterns. As previously described two separate regression models were completed whereby (1) Participants demonstrating HWM were compared to participants who started at healthy weight and transitioned to becoming at-risk and, (2) Participants demonstrating RHW was compared to children who remained at-risk in all four waves. A focused analysis of incidence of RHW was completed to further explore the role of age in predicting this pattern. Estimates of proportions and ORs in our regression models were weighted using the variables provided by ECLS-K.27 All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v 9.3 (SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA)

Results

Sample Characteristics

Weighted distributions of sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age at each wave was 6 (Kindergarten), 7 (1st grade), 9 (3rd grade) and 11 years (5th grade). Sixty percent of the children were White/Non-Hispanic, 13% were African-American, 19% were Hispanic, 2.9% were Asian with the remainder defined as other (e.g., Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian or multiracial). The majority of children were from low (18.3%) or middle (61.4%) income homes.

Table 1.

ECLS-K Sample Characteristics K-5th Grades

| Total (n=9416) | Gender, % (n)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Males (N=4735) | Females (N=4681) | ||

|

| |||

| Mean age in years (SD) | |||

|

| |||

| Kindergarten | 6.21 (0.36) | 6.24 (0.36) | 6.20 (0.35) |

|

| |||

| 1st grade | 7.23 (0.35) | 7.25 (0.35) | 7.22 (0.34) |

|

| |||

| 3rd grade | 9.23 (0.32) | 9.25 (0.32) | 9.22 (0.31) |

|

| |||

| 5th grade | 11.2 (0.44) | 11.2 (0.44) | 11.2 (0.43) |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

|

| |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 60.4 (5617) | 31.3 (2866) | 29.0 (2751) |

|

| |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 13.3 (1002) | 6.2 (493) | 7.1 (509) |

|

| |||

| Hispanic | 19.0 (1647) | 9.4 (809) | 9.6 (838) |

|

| |||

| Asian | 2.9 (617) | 1.3 (298) | 1.6 (319) |

|

| |||

| Other | 4.4 (523) | 2.2 (264) | 2.2 (259) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.8 (125) | 0.3 (65) | 0.5 (60) |

|

| |||

| American Indian/Alaskan | 1.4 (175) | 0.6 (87) | 0.8 (88) |

|

| |||

| More than one race | 2.1 (223) | 1.3 (112) | 0.9 (111) |

|

| |||

| SES** | |||

|

| |||

| Low | 18.3 (1474) | 9.9 (742) | 8.4 (732) |

|

| |||

| Middle | 61.4 (5478) | 30.6 (2748) | 30.8 (2730) |

|

| |||

| High | 20.4 (2179) | 10.1 (1100) | 10.3 (1079) |

|

| |||

| Weight Status At Cohort Entry | |||

| Underweight (BMI <5th) | 2.9(273) | 2.6(124) | 3.2(149) |

|

|

|||

| Healthy Weight (≥5th BMI <85th) | 70.3 (6617) | 69.4(3287) | 71.1(3330) |

|

| |||

| Overweight (≥85th BMI <95th) | 14.5 (1363) | 14.8(700) | 14.2(663) |

|

| |||

| Obese (BMI≥95th) | 12.4(1163) | 13.2(624) | 11.5(539) |

Frequencies provided are weighted to reflect oversampling of specific ethnic groups, thus discrepancies in column and row percentages are related to weighting. Reported sample sizes (n) are unweighted.

SES frequencies reflect the Kindergarten SES composite variable. SES categories reflect collapsed quintiles. High: 1st quintile, Middle: 2nd–4th quintiles, Low: 5th quintile

At the start of kindergarten 3% of children were underweight, 70% were healthy weight, 14.5% were overweight and 12.4% were obese (Table 1). Upon review of weight status change between K-5th grades, ten mutually exclusive growth patterns were identified (Appendix 1) including the two patterns of interest (HWM and RHW).

Healthy Weight Maintenance

Among children starting at a healthy weight in Kindergarten (n=6617), 69.4% (95%CI 67.2–71.6) maintained their healthy weight during the five year study period with girls demonstrating statistically significantly higher prevalence than boys (72.4%, 95%CI 69.6–75.2%, p<0.001). The prevalence of HWM was greatest among younger children at kindergarten entry (Boys: 65.4%, Girls: 71.8%) compared to older age children (Boys: 45.5%, Girls: 65.1%). These differences were statistically significant (p<0.0001). Children of higher socio-economic status had the greatest rates of HWM, with high-income girls demonstrating the greatest rates of this growth pattern (84.0%, 95%CI 80.4–87.6). The prevalence of HWM was highest among Asian and Non-Hispanic White children.

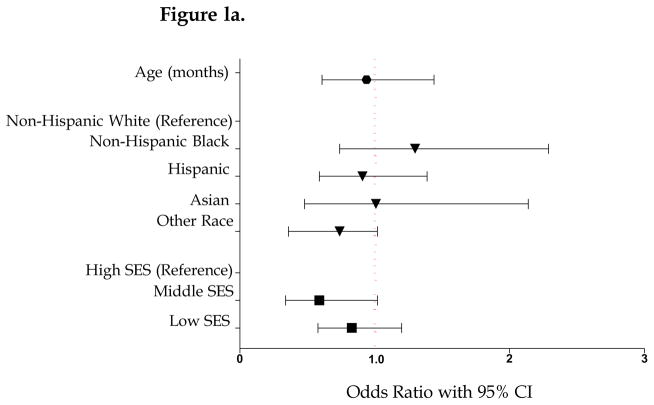

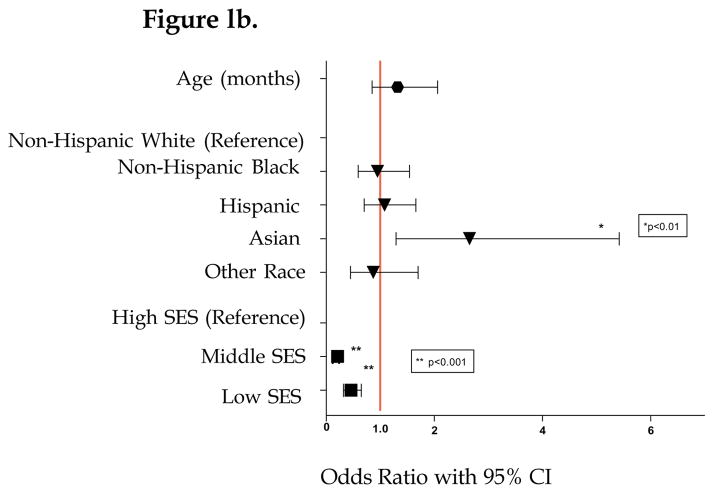

In a multivariate model controlling for age, race/ethnicity, and SES among boys, likelihood of HWM was not associated with key sample factors (Figure 1a). However, in an identical model among girls (Figure 1b), we found that Asian race/ethnicity was statistically significant in predicting HWM when compared to Non-Hispanic White girls (OR 2.65, 95%CI 1.29–5.42) and Non-Hispanic Black girls (OR 2.78, 95%CI 1.26–6.1. Results not shown). Additionally, females within both the middle and low income groups were noted to have statistically significantly decreased odds of healthy weight maintenance compared to higher income girls in the sample. This trend was observed for middle income boys however did not achieve statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. ECLS-K Boys (K-Sth Grade)

Multivariate Regression Model: Healthy Weight Maintenance

Figure 1b. ECLS-K Girls (K-Sth Grade)

Multivariate Regression Model: Healthy Weight Maintenance

Return to Healthy Weight-Prevalence

Though 25% of children started Kindergarten as overweight or obese, only 17.1% returned to a healthy weight by 5th grade (n=432, 95%CI 14.4–19.8). Girls had a statistically significantly higher prevalence of “outgrowing” obesity than did boys (Table 2, p<0.001). Younger girls (23.9%) and older boys (23.1%) had statistically significant higher rates of RHW compared to other age categories (both p values: <0.0001). Children of higher SES were noted to have the highest rates of RHW (30.9%, 95%CI 21.9–39.9). Hispanic and Asian males demonstrated the lowest prevalence of RHW (10.3% and 11.0%, respectively).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Obesity Resilient Growth Patterns by Key Sample Demographic Factors, ECLS-K (K-5th grade)

| Total Children HWM* (n=4659) | Boys (n=2223) | Girls (n=2436) | Total Children RHW** (n=432) | Boys (n=223) | Girls (n=209) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample Prevalence (%) K-5th Grade | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 69.4% (67.2–71.6) | 66.4% (63.4–69.5) | 72.4% 69.6–75.2) | 17.1% (14.4–19.8) | 15.2% (11.9–18.5) | 19.3%(15.3–24.2) | |

|

| ||||||

| Prevalence by Age at Cohort Entry (%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 4–5yrs | 68.7% (65.0–72.4) | 65.4% (59.7–71.2) | 71.8% (67.1–76.4) | 19.9% (15.1–24.7) | 15.8% (10.6–21.1) | 23.9% (16.3–31.5) |

| 6yrs | 70.1% (67.7–72.4) | 67.5% (64.2–70.8) | 72.8% (69.5–76.1) | 15.7% (12.9–18.6) | 14.8% (10.7–18.8) | 16.8% (12.5–21.2) |

| 7–8yrs | 52.8% (36.2–69.4) | 45.5% (30.3–60.7) | 65.1% (22.5–100) | 15.2% (10.1–20.3) | 23.1% (14.7–31.5) | 0% (N/A) |

|

| ||||||

| Prevalence by Socioeconomic Status (%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Low | 61.6% (56.3–66.9) | 61.3% (53.3–69.4) | 61.9% (54.2–69.6) | 12.0% (7.7–16.3) | 13.1% (6.3–19.9) | 10.7% (5.1–16.3) |

| Middle | 69.1% (66.3–71.8) | 66.8% (63.2–70.5) | 71.3% (67.2–75.3) | 15.6% (12.7–18.5) | 15.6% (11.3–19.9) | 15.6% (11.7–19.5) |

| High | 77.0% (73.0–80.9) | 69.9% (63.5–76.4) | 84.0% (80.4–87.6) | 30.9% (21.9–39.9) | 20.8% (12.7–28.9) | 40.7% (28.2–53.2) |

|

| ||||||

| Prevalence by Race-Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 71.5% (68.8–74.2) | 68.0% (64.3–71.7) | 75.4% (71.5–79.3) | 19.4% (15.2–23.6) | 15.4% (10.7–20.1) | 24.0% (17.9–30.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 62.5% (55.5–69.4) | 62.8% (52.9–72.7) | 62.1% (53.5–70.8) | 18.0% (10.9–25.1) | 25.6% (12.3–38.9) | 11.1% (2.64–19.6) |

| Hispanic | 66.1% (62.1–70.1) | 64.1% (57.7–70.4) | 67.8% (62.5–73.1) | 11.4% (8.2–14.6) | 10.3% (6.2–14.5) | 12.7% (7.7–17.6) |

| Asian | 74.2% (65.9–82.6) | 71.4% (61.9–80.9) | 76.3% (63.7–88.9) | 22.6% (11.3–33.8) | 11.0% (0–22.2) | 34.7% (16.5–53.0) |

| Other | 68.9% (60.9–76.8) | 59.1% (47.0–71.3) | 78.9% (71.0–86.8) | 13.0% (6.8–19.2) | 14.4% (3.9–24.8) | 11.6% (4.0–19.2) |

Healthy Weight Maintenance (HWM): prevalence estimate based on the total number of children starting at healthy weight in Kindergarten (n=6617)

Return to Healthy Weight (RHW): prevalence estimate based on total number of children overweight or obese in Kindergarten (n=2526)

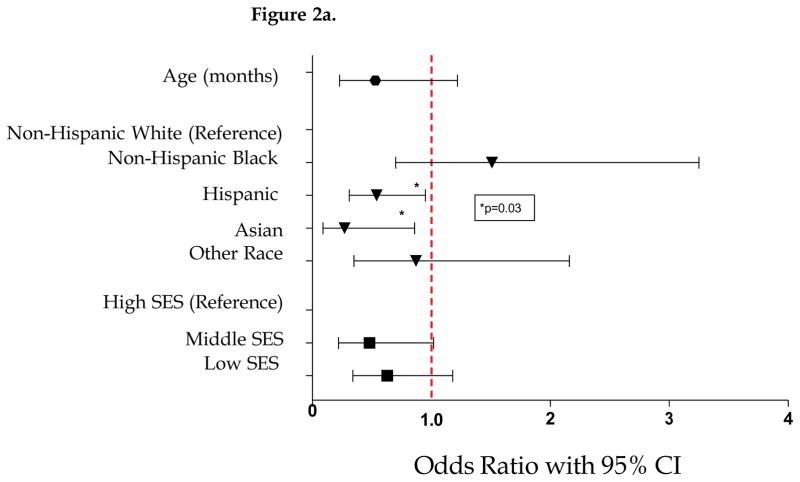

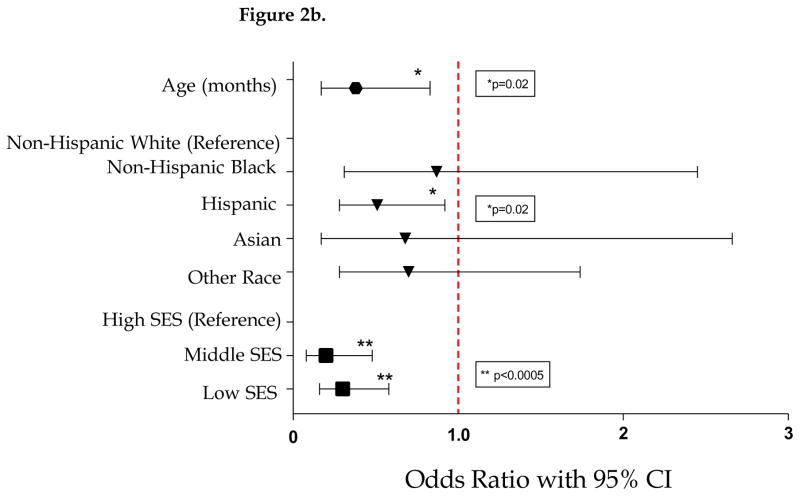

In the multivariate regression analysis, we found that Hispanic boys (OR 0.54, 95%CI 0.31–0.95) and girls (OR 0.51, 95%CI 0.28–0.92) were the least likely racial/ethnic group to return to healthy weight compared to Non-Hispanic White children (Figures 2a–b). Hispanic boys remained less likely to return to healthy weight (OR 0.36, 95%CI 0.16–0.80, results not shown) when compared to Non-Hispanic Black children. This relationship was not observed between Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Black girls. Asian boys in this sample were also noted to have significantly lower likelihood of returning to healthy weight compared to Non-Hispanic White and Black boys (OR 0.27, 95%CI 0.31–0.95 and OR 0.16, 95%CI 0.05–0.66 respectively). After adjusting for age and race-ethnicity, girls in the low (OR 0.30, 95%CI 0.16–0.58) and middle SES (OR 0.20, 95%CI 0.08–0.48) were less likely to return to a healthy weight when compared to their high-income counterparts. Girls of older age were noted to have statistically significantly decreased likelihood of returning to healthy weight compared to younger girls in the cohort (OR: 0.38, 95%CI 0.17–0.83).

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. ECLS-K Boys (K-Sth Grade)

Multivariate Regression Model: Return to Healthy Weight

Figure 2b. ECLS-K Girls (K-Sth Grade)

Multivariate Regression Model: Return to Healthy Weight

Return to Healthy Weight-Incidence

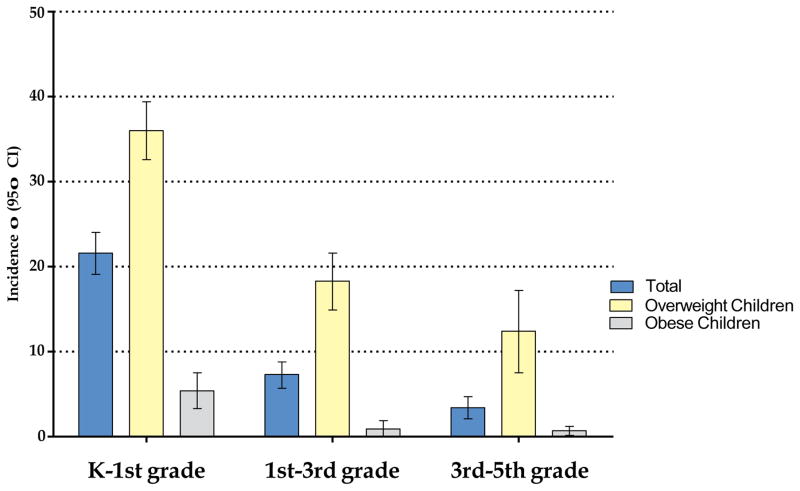

The highest incidence of outgrowing obesity occurred among at-risk Kindergarten children in this sample (Figure 3, Incidence: 21.6%, 95% CI 19.4–24.0). At-risk children in later grade intervals had a significantly lower incidence of outgrowing their weight risk (1st–3rd grade: 7.3% 95%CI 5.7–8.8, 3rd–5thgrade 3.4%, 95%CI 2.1–4.7). No significant differences in incidence of RHW were noted by gender. Overweight children, compared to obese children, consistently demonstrated a higher incidence of RHW at each grade interval.

Figure 3.

Return to Healthy Weight (RHW) Incidence by Grade Interval, Weight Status

Discussion

In 2001, the Surgeon General published a call to action to treat and prevent obesity among children34. Within this sample of children living during a time (1999–2004) where obesity had only recently become a national health priority, nearly 70% of US children were able to maintain a healthy weight during school age. That a majority of children demonstrated this favorable growth pattern during a socio-ecologic window where factors including ubiquitous obesogenic built environments, under-prioritized school nutritional policies and only early awareness of the obesity epidemic may have contributed to child weight risks,35–36 supports the hypothesis that HWM may itself reflect resilience to existing socio-ecologic risk factors. Additionally, with over 25% of children starting at an overweight or obese status in kindergarten, we found that the fewer than 1 in 5 children (17.1%) initially overweight/obese in kindergarten were able to outgrow their obesity by the 5th grade. Thus, pervasive expectations that children will ultimately outgrow their weight risk are unlikely based on our analysis of a nationally representative sample. With a focus on pre-pubertal children during school age, this is the first study to our knowledge to explore associations between gender, race/ethnicity and socio-economic status in predicting favorable growth patterns such as healthy weight maintenance and return to healthy weight.

With a growing body of work relating obesity disparities to poverty,37 our findings support SES as a strong predictor of the broader nutritional state of school-age children in that fewer middle and low income children were able to maintain a healthy weight or return to healthy weight. In prior studies exploring resilience to obesity in socio-economically disadvantaged females, 21, 24, 38 factors including youth and higher educational levels were associated with increased resilience against obesity. Our findings support these initial results in that the lowest rates of both HWM and RHW were found in low-income girls after adjusting for age and race-ethnicity. Though interventions targeting low-income children have received increased attention in recent years, 39–40 our findings suggest that an assessment of what may confer obesity resilience among low/middle income girls during a critical growth window is necessary. In a review by Wang et. al, the well-known associations between risks for obesity were identified to be more complex than to be explained simply by individual SES41 and that a bidirectional causal relationship may be present where nutritional status predicts educational/socio-economic opportunities and that these opportunities predict nutrition status. A focused assessment on the educational and socio-economic opportunities experienced by low-income girls, specifically in older age intervals (1st–5th grade) may further explain differences in HWM and RHW prevalence for this population. We additionally identified that the highest grade-related incidence of RHW occurred among younger at-risk school-age children (21.6%) compared to those in later grades (7.3% and 3.4% respectively). Age was also identified as a significant predictor of RHW among girls in the sample. Our data support recent findings by Cunningham et. al indicating that growth trajectories are largely determined by 5 years of age.42 These data challenge long-standing expectations that older children make healthy weight transitions more commonly than younger children16, 18 and in fact validate ongoing discussions prioritizing preschool age as a time of where critical assessment and robust intervention are needed. Moreover, with an understanding that overweight kindergartners (BMI≥85th to <95th) were most likely to demonstrate obesity resilience with a RHW pattern (36% incidence in kindergarten), new policies, programs, and campaigns focusing on this “lower-risk” population may yield the greatest impact in promoting favorable growth transitions.

In accordance with a number of other studies that have outlined disparities among young Hispanic children for obesity, 25–26, 43 our analysis found that Hispanic children were the least likely racial/ethnic group to outgrow their obesity risk. Whereas Asian girls demonstrated a greater prevalence of HWM, Asian boys demonstrated lower likelihood of outgrowing obesity along with Hispanic males. This constellation of findings supports prior work that has described complex socio-ecologic interactions between genetics, culture and normative beliefs on child growth influencing obesity onset and validates the expectations that similar factors also influence healthy transitions between weight categories during childhood. Further, the similarities observed between Asian and Hispanic boys in demonstrating reduced resilience suggest that parallel socio-ecologic interactions, particularly surrounding polarization of male and female growth expectations, 20, 44 may exist within these cultural groups that limit obesity resilience. Support of future studies using sampling designs where oversampling and assessment of Hispanic and Asian ethnic subgroups are consistently performed, is a means by which to further study these interactions and begin to more effectively address obesity health disparities in children.

Strengths to our study include the use of a longitudinal, nationally representative and diverse dataset of school-age children whereby growth patterns are likely generalizable to many populations. In addition, an assessment of obesity resilience during a socio-ecologic time when obesity prevention was not yet a central health priority (1990s–2000s) adds value to consider variations in disease when risk is more uniformly elevated. Additional strengths include the ability to use multiple, sequential data collection points to add rigor to our assessment of growth transitions and patterns.

There are important limitations to note within our study sample and analytic approach. Our data restriction of only including participants with intact height and weight measurement may have introduced some selection bias. Specifically, our sample comparison indicated that 1% fewer Hispanic participants were included in our analytic sample which may have led to underestimates of resilient growth patterns in this racial-ethnic group. We feel that use of the ECLS-K sample weights where oversampling and missingness were included, minimized the likelihood of selection bias. Also, collapsing of multiple racial groups into a larger “Other” race/ethnicity category, limited our ability to explore HWM and RHW among Native American, Pacific Islander and multiracial children. Next, our definition of HWM and RHW might have limited our ability to identify other favorable growth patterns in this population of children. In addition, we limited our exploration of covariates associated with HWM and RHW to age, gender SES and race/ethnicity. Clearly, other factors should be considered as predictors of growth in school age children however, as these growth patterns had not previously been explored, we felt that an analysis focused on key, immutable factors would inform next steps.

Conclusion

Curbing the pediatric obesity epidemic will depend on exploring all aspects of growth in children including an understanding of obesity resilient growth patterns. Although many school-age children demonstrate HWM, few children exhibit RHW. Identifying strategies where clinicians can promote HWM and RHW patterns among groups demonstrating disparities in these patterns may be a necessary next step in advancing clinical practice. A comprehensive socio-ecologic approach where these patterns of interest are studied will add substantial depth to our understanding of risk and resilience to pediatric obesity.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1: Prevalence of All Observed Growth Patterns by Key Demographic Factors, ECLS-K Cohort (K-5th Grade)

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: All phases of this study were supported by the All Children’s Johns Hopkins Medicine Foundation. Grant number: 506427-6800.

Abbreviations

- HWM

Healthy Weight Maintenance

- RHW

Return to Healthy Weight

- ECLS-K

Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Kindergarten Cohort

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: All authors have report no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Potential Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Contributor’s Statements:

Raquel G. Hernandez: Dr. Hernandez conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the study analyses, drafted and reviewed the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Janelle Garcia: Dr. Garcia acquired and analyzed the data. She additionally contributed to the initial manuscript and approved of the final manuscript as submitted.

Ernest K. Amankwah: Dr. Amankwah acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Arik V. Marcell: Dr. Marcell contributed to the study design, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Tina L. Cheng: Dr. Cheng critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

References

- 1.Nonnemaker JM, Morgan-Lopez AA, Pais JM, Finkelstein EA. Youth BMI trajectories: evidence from the NLSY97. Obesity. 2009 Jun;17(6):1274–1280. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nader PR, O’Brien M, Houts R, et al. Identifying Risk for Obesity in Early Childhood. Pediatrics. 2006 Sep;118(3):e594–e601. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham SA, Kramer MR, Narayan KMV. Incidence of Childhood Obesity in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(5):403–411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li C, Goran MI, Kaur H, Nollen N, Ahluwalia JS. Developmental trajectories of overweight during childhood: role of early life factors. Obesity. 2007 Mar;15(3):760–771. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obesity reviews: an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2008 Sep;9(5):474–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am J Med. 1977 May;62(5):707–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verschooten L, Declercq L, Garmyn M. Adaptive response of the skin to UVB damage: role of the p53 protein. International journal of cosmetic science. 2006 Feb;28(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.2006.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruger S, Alda M, Young LT, Goldapple K, Parikh S, Mayberg HS. Risk and resilience markers in bipolar disorder: brain responses to emotional challenge in bipolar patients and their healthy siblings. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006 Feb;163(2):257–264. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Persaud D, Gay H, Ziemniak C, et al. Absence of detectable HIV-1 viremia after treatment cessation in an infant. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Nov 7;369(19):1828–1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sapouna M, Wolke D. Resilience to bullying victimization: the role of individual, family and peer characteristics. Child abuse & neglect. 2013 Nov;37(11):997–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitaker RC, Pepe MS, Wright JA, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Early adiposity rebound and the risk of adult obesity. Pediatrics. 1998 Mar;101(3):E5. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.3.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nader PR, O’Brien M, Houts R, et al. Identifying risk for obesity in early childhood. Pediatrics. 2006 Sep;118(3):e594–601. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serdula MK, Ivery D, Coates RJ, Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Byers T. Do obese children become obese adults? A review of the literature. Prev Med. 1993 Mar;22(2):167–177. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker JL, Olsen LW, Sorensen TI. Childhood body-mass index and the risk of coronary heart disease in adulthood. The New England journal of medicine. 2007 Dec 6;357(23):2329–2337. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baughcum AE, Chamberlin LA, Deeks CM, Powers SW, Whitaker RC. Maternal perceptions of overweight preschool children. Pediatrics. 2000 Dec;106(6):1380–1386. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain A, Sherman SN, Chamberlin LA, Carter Y, Powers SW, Whitaker RC. Why don’t low-income mothers worry about their preschoolers being overweight? Pediatrics. 2001 May;107(5):1138–1146. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherry B, McDivitt J, Birch LL, et al. Attitudes, practices, and concerns about child feeding and child weight status among socioeconomically diverse white, Hispanic, and African-American mothers. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004 Feb;104(2):215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eckstein KC, Mikhail LM, Ariza AJ, et al. Parents’ perceptions of their child’s weight and health. Pediatrics. 2006 Mar;117(3):681–690. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mustillo S, Worthman C, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ. Obesity and psychiatric disorder: developmental trajectories. Pediatrics. 2003 Apr;111(4 Pt 1):851–859. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lundahl A, Kidwell KM, Nelson TD. Parental Underestimates of Child Weight: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014 Feb 2; doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2690. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Ball KDL. Physical Activity, ehalthy eating and obesity prevention: understanding and promoting “resilience”: amongst socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. Austral Epidemiol. 2010;17(3):16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wen X, Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Sherry B, Kleinman K, Taveras EM. Decreasing prevalence of obesity among young children in Massachusetts from 2004 to 2008. Pediatrics. 2012 May;129(5):823–831. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, Taveras EM. Trends and racial/ethnic disparities in severe obesity among US children and adolescents, 1976–2006. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010 Mar 17; doi: 10.3109/17477161003587774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ball K, Abbott G, Cleland V, et al. Resilience to obesity among socioeconomically disadvantaged women: the READI study. International journal of obesity. 2012 Jun;36(6):855–865. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balistreri KS, Van Hook J. Trajectories of overweight among US school children: a focus on social and economic characteristics. Matern Child Health J. 2011 Jul;15(5):610–619. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0622-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012 Feb 1;307(5):483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tourangeau KNC, Le T, Sorongon AG, Najarian M. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–99 (ECLS-K): Combined user’s manual for the ECLS-K Eighth-Grade and K-8 full sample data files and electronic codebooks (NCES 2009-004) Washington D.C: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cummings P. Missing data and multiple imputation. JAMA pediatrics. 2013 Jul;167(7):656–661. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epi Info [computer program]. Version 3.5.4. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed Januray 25, 2013];Growth Charts. 2010 http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/

- 31.Chang Y, Gable S. Predicting weight status stability and change from fifth grade to eighth grade: the significant role of adolescents’ social-emotional well-being. J Adolesc Health. 2013 Apr;52(4):448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gable S, Krull JL, Chang Y. Boys’ and girls’ weight status and math performance from kindergarten entry through fifth grade: a mediated analysis. Child development. 2012 Sep-Oct;83(5):1822–1839. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss BG, Yeaton WH. Young children’s weight trajectories and associated risk factors: results from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort. Am J Health Promot. 2011 Jan-Feb;25(3):190–198. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090123-QUAN-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General., United States. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.), National Institutes of Health (U.S.) The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. Rockville, MD Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD, et al. Obesogenic neighborhood environments, child and parent obesity: the Neighborhood Impact on Kids study. American journal of preventive medicine. 2012 May;42(5):e57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cleland VJ, Ball K, Salmon J, Timperio AF, Crawford DA. Personal, social and environmental correlates of resilience to physical inactivity among women from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds. Health education research. 2010 Apr;25(2):268–281. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y, Zhang Q. Are American children and adolescents of low socioeconomic status at increased risk of obesity? Changes in the association between overweight and family income between 1971 and 2002. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2006 Oct;84(4):707–716. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ball K, Cleland V, Salmon J, et al. Cohort Profile: The Resilience for Eating and Activity Despite Inequality (READI) study. International journal of epidemiology. 2012 Dec 18; doi: 10.1093/ije/dys165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kit BK, Ogden CL, Flegal KM. Prescription medication use among normal weight, overweight, and obese adults, United States, 2005–2008. Ann Epidemiol. 2012 Feb;22(2):112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ploeg VM. WIC and the Battle Against Childhood Overweight. United States Department of Agriculture; Apr, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States--gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiologic reviews. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cunningham SA, Kramer MR, Narayan KM. Incidence of childhood obesity in the United States. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Jan 30;370(5):403–411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman K, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Racial/ethnic differences in early-life risk factors for childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2010 Apr;125(4):686–695. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olvera N, Suminski R, Power TG. Intergenerational perceptions of body image in hispanics: role of BMI, gender, and acculturation. Obesity research. 2005 Nov;13(11):1970–1979. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Prevalence of All Observed Growth Patterns by Key Demographic Factors, ECLS-K Cohort (K-5th Grade)