Abstract

Research on the relationship between social capital and individual health often suffers from important limitations. Most research relies on cross-sectional data, which precludes identifying whether participation predicts health or vice-versa. Some important conceptualizations of social capital, like social participation, have seldom been examined and little is known about participation and health in sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, both physical and mental health have seldom been tested together, and variation by age has rarely been examined. We use longitudinal survey data for 2328 men and women from the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health, containing (1) several measures of social participation, (2) measures of physical and mental health, and (3) an age range of 15–80+ years. Our results differ by gender and age, and for mental and physical health. We find that social participation is associated with better physical health but can predict worse mental health for Malawians.

Introduction

In studying its relationship with health, social capital has been measured in a myriad of ways: social network characteristics, kinship ties, transfers, social trust, and social support (e.g,. Cattell 2001; Moffitt 2002; Rose 2000; Szreter and Woolcock 2004; Wind and Komproe 2012). Social participation, studied much less frequently, plays a central role in social capital formation (Putnam 2000): participation in social organizations and events facilitates the development of ties with otherwise-unknown individuals, resulting in an expanded social network (Feld 1981) that offers access to “embedded” resources (Lin 1999). Thus, greater social participation could increase one’s access to resources and support that provide a range of livelihood benefits, including better health.

Although research has often identified an association, identifying the reasons why social capital and health are linked remains challenging. A general explanation for this connection comes from Durkheim (1951) who suggests that social integration gives meaning to one’s life and thus reduces the chances of poor mental health (such as depression) or mortality (via suicide). Greater detail on the connection between social capital and health, however, remains elusive for several reasons.

Identifying the mechanisms that connect social capital with health is challenging in part due to the reliance on cross sectional data (e.g., Helliwell and Putnam 2004; Hyyppä and Mäki 2003; Lindström, Hanson, and Östergren 2001; Veenstra 2000). While a cross-sectional approach is useful in establishing an association between social participation and health, it cannot establish why the association is found: a positive relationship between participation and health could be due to the effect of participation on health, or the fact that individuals with higher income or educational attainment are both healthier and more likely to participate (Navarro 2002).

Additionally, most research on social participation and health has come from high-income countries (HICs) and comparatively little is known about this topic in low-income countries (LICs). The decline of civic engagement over the past half century has been well-documented in the US (Putnam 2000); but high levels of social participation are the norm in many LICs, where having a strong sense of community is necessary for survival. A LIC context provides an interesting comparison, as the type of social participation that is beneficial (or detrimental) to one’s health in HICs might not be the same in a markedly different social structure. For instance, many LICs offer limited or no formal credit and insurance systems, which often means that individuals need to rely more on the development of social ties for times of crisis. Thus, social participation—and the possibility of developing new ties and accessing their resources in the process—may play a more important role in the daily life of residents of LICs.

Other limitations common to research on social capital and health include a focus on either physical or mental health only, and it is unknown how the impact of social participation compares across these dimensions of health. Further, the literature also suggests that the relationship between social participation and health likely varies by age due to the functional limitations of older adults. But age differences in the relationship between social participation and health have seldom been examined.

We use a longitudinal dataset to examine the relationship between social participation and health in rural Malawi. This setting is appropriate, since social participation and community involvement are integral to Malawi’s cultural identity (Forster 1994), and Malawi is one of the least developed countries in the world, with low life expectancies and little access to formal health care. We have two main goals for this paper: to (1) use longitudinal data to address common methodological limitations in research on social participation and health, and (2) expand the geographical scope of this research to a high mortality and morbidity setting where social participation plays a key role in daily life.

Background

Social Participation and Health: A Brief Overview

Most definitions of social capital involve social connections of varying strength and trust (see Adler and Kwon 2002 for a review). These connections are valuable since they provide individuals with the ability to access resources, information, and support in the present and future (Bourdieu 1986; Coleman 1988; Lin 1999; Putnam 2000).

Most forms of social capital are perceived to benefit individuals in achieving desired outcomes. Thus it is not surprising that research has typically found a positive relationship between social capital and mental and physical health. Many explanations support Durkheim’s (1951) views on the benefits of social integration, in which being socially engaged often boosts one’s outlook, sense of autonomy, and overall mental health (Cattell 2001; Moffitt 2002; Rose 2000). As with social capital, social participation has been positively linked with various health measures, such as lower rates of heart diseases, cancers, infant mortality (Kawachi et al. 1997), and adult mortality (Dalgard and Håheim 1998; Lochner et al. 2003); as well as higher levels of happiness, mental health, and self-rated health scores (Helliwell and Putnam; Hyyppä and Mäki 2003; Kawachi, Kennedy, and Glass 1999; Nummela et al. 2008; Phillips 1967; Veenstra 2000; Young and Glasgow 1998).

However, other theoretical and empirical perspectives suggest that the positive relationship between participation and health is not axiomatic. The benefits of social participation may depend on the group and setting. As Szreter and Woolcock argue (2004), being connected to a large number of people who know little about hip replacements—a procedure which for some individuals might mean extending their active and physically healthy lifestyles for another decade or two—is not more advantageous than being connected to a smaller group of people who know a lot about hip replacements. In essence, being in social circles with the “right” people could be beneficial to physical health outcomes. But in some cases, these connections may just be markers for other factors that influence health, such as having a high income, living in a good neighborhood, or being among other healthy individuals, all of which increase one’s chances of being in good physical health (Kawachi et al. 1997; Kawachi et al. 1999; Navarro 2002). In addition, participating in groups that engage in illicit or unhealthy behaviors such as smoking also can be deleterious to one’s health (Mercken et al. 2010). It is also possible that high levels of social participation could have detrimental impacts on one’s health, due to the stress and physical demands of meeting community obligations, particularly for women (Kawachi and Berkman 2001).

The relationship between social participation and health is likely moderated by age. The limited existing research suggests two ways in which social participation varies by age. First, participation declines as individuals get older (Morgan 1988) as a result of smaller social networks due to fewer living kin and friends (Ajrouch, Blandon, and Antonucci 2005; Cornwell 2011; Marsden 1987). Therefore, it is plausible that declines in social participation would be related to declines in health as people get older. Second, as individuals age, forms of social participation that require more intense physical activity are replaced by less strenuous forms, and overall participation may therefore not be substantially less than younger ages (Bukov, Maas, and Lampert 2002; Cornwell, Laumann, and Schumm 2008). In this case, one’s health could be improved by participating in more activities, even though they are less strenuous and potentially beneficial to one’s immediate physical health. The limited evidence suggests that even if older individuals have low functional ability, social participation of any kind can still mitigate the negative effects of disability on health (Avlund et al. 1999). It appears that age is an important moderator in the relationship between social participation and health, but there is relatively little research on this topic.

Lastly, there is only a small body of research on the relationship between social participation and health in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), which focuses on HIV infection. Participating in organized clubs is associated with both lower chances of young adults becoming infected with HIV (Campbell, Williams, and Gilgen 2002; Gregson et al. 2004) and higher likelihood of HIV infection (particularly for women) due to greater levels of exposure to potential sexual partners, who might have HIV (Pronyk et al. 2008).

The Malawian Context

Malawi is an instructive setting for examining the relationship between social participation and health. Recent research shows that social interaction is an essential part of in everyday life in Malawi (Gerland 2006, Helleringer and Kohler 2005; Kohler, Behrman, and Watkins 2007; Watkins 2004), but social participation has not been examined in this context. Going to the market, attending political meetings, and partaking in religious ceremonies are events that routinely bring people together in tightly knit rural communities. Religious organizations have been particularly important in disseminating information about HIV/AIDS in Malawi, and are primary sources of emotional and financial support to family members in the aftermath of HIV-related deaths (Trinitapoli and Weinreb 2012). Participating in such events are fairly common in other parts of the world, but seemingly a more critical component of Malawian life due to the efforts of its first President, Hastings Kamuzu Banda, who promoted the importance of maintaining “traditional” African values and resisting the individualism found in Western cultures after gaining independence from Britain in the 1960s (Forster 1994).

Despite the importance of social participation, there is reason to believe that not all social participation yields benefits for rural Malawians. Several common venues of participation in Malawi may be associated with health risks: two common locations for participation in Malawi, bars and funerals (Watkins 2004), may have negative impacts on mental and physical health. In addition, given the importance of transfers in Malawi (Swidler and Watkins 2007), social participation may involve obligations of reciprocity that can have a detrimental impact on mental health (ie., Kawachi and Berkman 2001). In Malawi, the fear of being infected by HIV itself is negatively associated with mental health, and religious or political participation does not mitigate this relationship (Hsieh 2013). It is possible that participation in such venues could be stressful or not relaxing. Since social participation is such a routine part of daily life in Malawi, does it have the same effect on health as it seemingly does in a much more individualistic society like the US, where engaging in community activities is seemingly more rare? Alternatively, if a subset of people do not engage in social activities in Malawi, would they be marginalized and not have access to others who could help improve their lives? These questions are important to consider in the Malawian context since they will change our interpretation of the mechanisms linking social participation and health.

As with many countries in SSA, Malawi has relatively low life expectancy, at 51.6 years (UN 2013). Malawi is also predicted to have a rapidly increasing number of elderly individuals in the next half century: life expectancy has been projected to increase nearly 15 years, and 41% of men and 58% of women 45 years older are expected to live their remaining years with major functional limitations (Payne, Mkandawire, and Kohler 2013). One must therefore question whether social participation among Malawi’s older individuals might mitigate some of these declines in health. Finally, as in many other settings in SSA, the predominant focus of social networks and participation has been with regards to HIV infection in Malawi, as opposed to general health.

Data

The Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health

We use data from the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH).1 The MLSFH was designed as a couples’ survey, targeting a population-based representative sample of approximately 1500 ever-married women aged 15–49 and 1000 of their husbands in three rural sites of Malawi. The first follow-up in 2001 included all respondents from the first wave, along with any new spouses. The MLSFH then followed-up with all respondents in 2004, 2006, 2008 and 2010. A description of MLSFH data and sampling technique is described in Watkins et al. (2003) and Kohler et al. (2014); Bignami-Van Assche, Reniers, and Weinreb (2003), Anglewicz et al. (2009), and Kohler et al. (2014) provide assessments of MLSFH data quality.

There are several features of the MLSFH data that are essential for our research on social participation and health. First, the MLSFH data contain a range of common social activities in Malawi and elsewhere in the region. Second, the MLSFH includes robust measures of mental and physical health, which offers several advantages over single-item ratings of health. Third, the longitudinal nature of the data enables us to establish the time-order of events between social participation and health. Unlike the cross-sectional analysis that is common in this area of research, the longitudinal data allows us to identify how social participation predicts physical and mental health without the potential bias of selection of individuals with worse (or better) health into more (or less) participation. We use the two most recent rounds of MLSFH data (2008 and 2010) in this analysis. Our sample consists of 2,328 individuals (1,411 women and 917 men) who were interviewed by MLSFH in both 2008 and 2010.

Measures

For our health outcomes, we use the SF-12 summary measures of mental and physical health. The SF-12 measure has been extensively validated as an accurate measure of mental and physical health (Ware, Kosinski, and Keller 1996), and has been used in a range of cultural contexts (Gandek et al. 1998). While most studies on the relationship between social participation and health have typically focused on various measures of either physical or mental health, much less is known about the relationship between participation and both types of health, particularly in SSA.2

We measure social participation using a set of social activities that are among the most common in rural Malawi. First, we focus on monthly participation activities: “How many times in the last month have you been to: (1) a funeral, (2) a drama performance, (3) a beer place, (4) a place where people dance, and (5) a market. Our second measure is similar, but based on information from the number of times in the last year that respondents have attended a (1) wedding, (2) drama about family planning or HIV/AIDS, and (3) political meeting (events that take place less frequently than those above). Next, we consider a conventional operationalization of social participation: group memberships, constructed based upon whether respondents were members of seven possible village committees, including committees for (1) development, (2) health, (3) funerals, (4) the market, (5) the Chief’s council, (6) District development, and (7) HIV/AIDS.3 Lastly, we measure participation in religious activities using the last time the respondent went to a church/mosque (never=1, 6 months or more=2, last 2–6 months=3, last month=4, last week=5), which is treated as a continuous variable in our analyses.

These four sets of measures offer several benefits for examining the relationship between participation and health in Malawi: these measures include among the most common venues for participation in Malawi, they provide a comparison of participation by exposure time (month, year), and the variety of venues allow for a much more complete evaluation of social participation than most previous studies. To examine the relationship between social participation and health, we use a summary of the overall number of instances of participation for all venues, group membership, and religious activities in order to most effectively approximate social integration, in a Durkheimian fashion and to capture the Malawian spirit of communalism (Forster 1994), rather than identifying individual effects of activities.

Methods

We begin by providing background information for all measures of interest, separately for men and women. Next, we examine the bivariate relationship between each social participation measure and age, to examine whether the theorized relationship is apparent in our data.

A central feature of our analysis is to identify the association between participation and health while controlling for the possibility that healthier individuals are more likely to participate in social activities. Longitudinal data permit us to use measures of social participation and heath from different times, thereby ensuring that the social participation occurred before the health measurement. Measuring social participation prior to health reduces the chances that an association between social participation and health occurs because healthier individuals are more likely to participate in social activities. Thus, we run OLS multivariate regressions in which the dependent variables are the 2010 SF-12 measures of mental and physical health, and the key independent variables are the 2008 measures of social participation. It is important to note that good or bad health can persist over time, in which case the selection of individuals with systematically different health status into participation could occur before 2008. To reduce this possibility, we also include a baseline (i.e., 2008) measure of mental and physical health in these regressions.

We begin with regressions in which the dependent variables are the 2010 SF-12 summary scores for physical and mental health. For both of these outcomes, we run separate regressions for each of the four summary measures of social participation: monthly, annually, village committee participation, and religious activities. In each regression we also control for factors that, according to the literature, are likely to be associated with both social participation and health. For example, several environmental features, such as population density, access to health care, and climate, vary across the three regions of Malawi and are likely related to both health and social participation. We therefore include a measure of region of residence in the regression models. Other control variables include the number of individuals in each household, and four additional salient predictors of health: education (lower education is typically associated with worse health), marital status (individuals who are married are often the healthiest), age (on average, older individuals are not as healthy as younger individuals), and occupation.4 We run regressions separately for women and men given the extent to which social norms are strongly gendered and that women have “less access to income and less social power” than men (Schatz 2005: 489).

Next, to evaluate the possibility that the relationship between social participation and health changes with age, we then present separate regressions by age group less than 45 years old and 45 years and older. This age cut-off is a conventional marker for defining “younger” and “older” Malawians because the current life expectancy at birth is just over 50 years old, and 45 years marked the age at which Malawians begin to suffer from substantial functional limitations (Payne et al. 2013). We run the same regressions as above (for all age groups) for the older and younger age group.5

Results

Descriptive Statistics

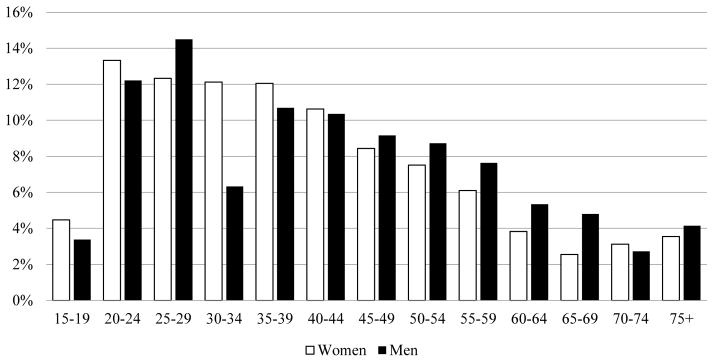

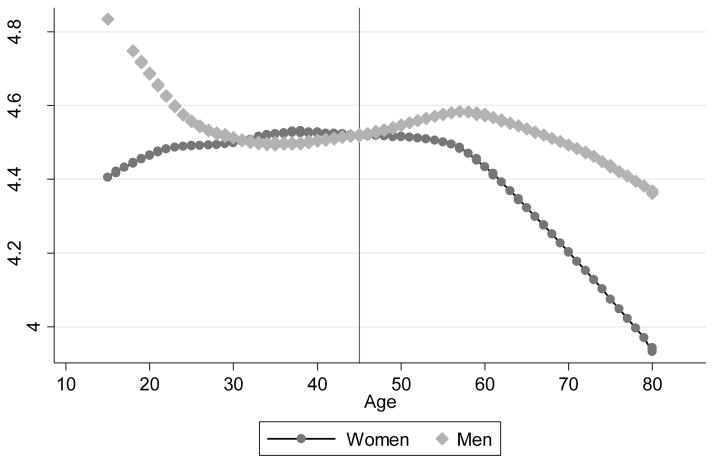

Table 1 provides characteristics of our sample. Men are older than women by an average of approximately two years. Respondents are approximately evenly distributed by region, about one third each in Mchinji (Central Region site), Balaka (Southern Region site), and Rumphi (Northern Region site). Women have less education than men and are less likely to be currently married (compared to divorced or widowed), but average household size is similar by gender. Physical and mental health declined over time between 2008 and 2010 for both men and women. The age distribution of respondents can be found in Figure 1, which shows a substantial percentage of relatively older respondents: 35.5% of women (501) and 43.0% of men (394) are 45 years or older.

Table 1.

Background characteristics, 2008/10 MLSFH women and men

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 Mean age | 40.5 | 42.6 |

| 2008 Level of education | ||

| No education | 31.9% | 14.0% |

| Primary | 61.5% | 66.5% |

| Secondary or higher | 6.6% | 19.5% |

| 2008 Region of residence | ||

| Mchinji | 30.8% | 33.0% |

| Balaka | 35.4% | 29.1% |

| Rumphi | 33.8% | 37.9% |

| 2008 Marital status | ||

| Currently married | 79.5% | 88.0% |

| Widowed/divorced | 19.2% | 3.2% |

| Never married | 1.3% | 8.8% |

| 2008 Mean household size | 5.0 | 5.2 |

| 2008 Occupation | ||

| Agricultural laborer in own land | 63.7% | 64.4% |

| Agricultural wage laborer | 6.5% | 4.8% |

| Salaried employment | 0.6% | 3.1% |

| Market work/sales | 8.5% | 6.0% |

| Handicraft production | 9.4% | 11.7% |

| Other | 11.3% | 10.0% |

| Health status | ||

| 2008 Mean SF-12 mental health | 53.0 | 55.9 |

| 2008 Mean SF-12 physical health | 51.2 | 52.6 |

| 2010 Mean SF-12 mental health | 51.3 | 53.8 |

| 2010 Mean SF-12 physical health | 48.9 | 50.0 |

| N= | 1411 | 917 |

Figure 1.

MLSFH Age Distribution by Sex

We summarize social participation for men and women in Table 2. In 2008, men reported participating in a greater number of total events (15.4) in the past month than women (10.2), on average. Of the number of activities respondents were asked to list that they attended in the previous year, men participated more on average than women (5.2 to 2.7 events). Men appear to attend church or mosque more regularly than women. Lastly, men participated in 1.6 groups, women in 0.8, on average.

Table 2.

2008 Social participation, MLSFH women and men

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| Monthly activities: mean number of times in the last month respondent attended a | ||

| Funeral | 3.5 | 3.7 |

| Drama | 0.3 | 1.1 |

| Bar | 0.3 | 2.5 |

| Dance | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Market | 5.8 | 7.8 |

| Total average monthly activities | 10.2 | 15.4 |

| Annual activities: mean number of times in the last year respondent attended a | ||

| Wedding | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| Drama on family planning or HIV/AIDS | 0.7 | 1.4 |

| Political meeting | 1.3 | 2.0 |

| Total average annual activities | 2.7 | 5.2 |

| Mean committee participation | 0.8 | 1.6 |

| Religious participation: last time attended a church/mosque | ||

| In the last week | 62.9% | 68.7% |

| In the last month | 29.6% | 24.5% |

| In the last 2–6 months | 4.2% | 2.0% |

| 6 months or more | 3.1% | 3.3% |

| Never | 0.2% | 1.5% |

| N= | 1411 | 917 |

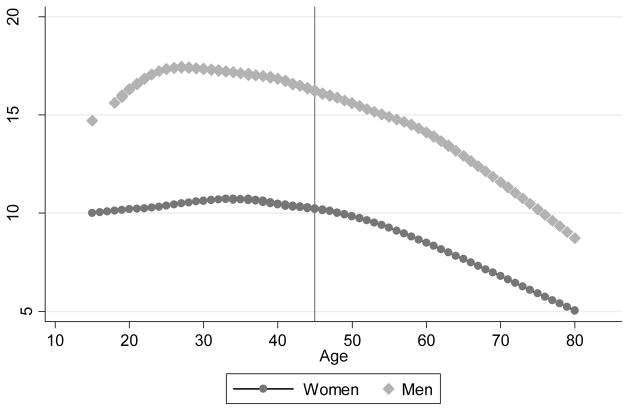

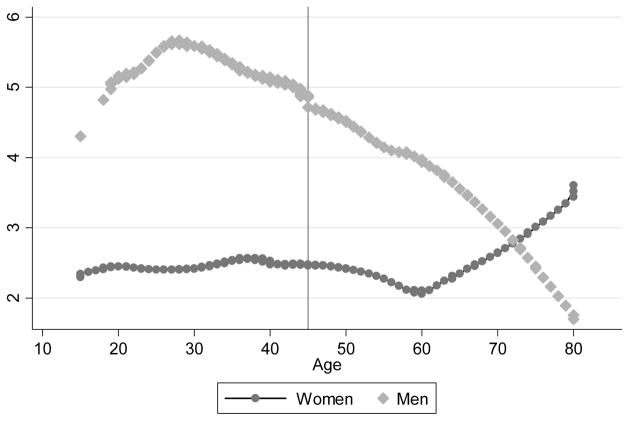

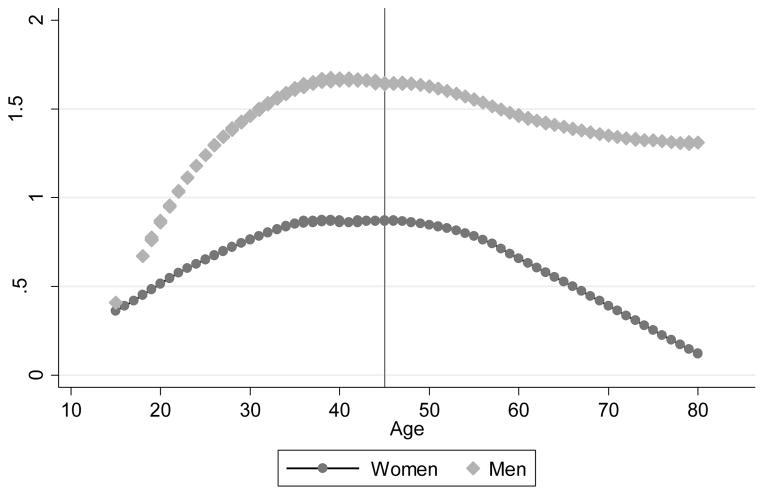

As shown in Figures 2, 3,4,5, social participation declines with age, which provides support for the literature, stemming from HICs, that participation declines as physical limitations increase with age. However, it is important to note an exception to this pattern: there is an increase in annual activities among women in older ages, which appears to occur around the same time as monthly activities decline. This may be due to switching of activities due to an increase in functional limitations for women, as described above.

Figure 2.

Monthly Participation by Age and Sex 2008 MLSFH

Figure 3.

Annual Participation by Age and Sex 2008 MLSFH

Figure 4.

Committee Participation by Age and Sex 2008 MLSFH

Figure 5.

Religious Participation by Age and Sex 2008 MLSFH

Results for the first stage of multivariate analysis are shown in Tables 3A (dependent variable is physical health) and 3B (mental health). The key dependent variables of interest, social participation (separately for monthly participation, annual participation, and committee membership) appear at the bottom of each table, in bold (results for religious activities are presented separately).

Table 3A.

OLS regression results for the association between 2008 social participation and 2010 physical health for MLSFH men and women

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Age | −0.19*** | 0.02 | −0.19*** | 0.02 | −0.19*** | 0.02 | −0.19*** | 0.02 | −0.19*** | 0.02 | −0.20*** | 0.02 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Primary | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.08 | 0.81 | 0.04 | 0.81 |

| Secondary+ | 1.49 | 1.12 | 1.42 | 1.12 | 1.52 | 1.12 | −0.90 | 1.06 | −0.82 | 1.05 | −0.86 | 1.06 |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| Mchinji (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Balaka | −0.40 | 0.63 | −0.28 | 0.62 | −0.18 | 0.62 | −0.60 | 0.75 | −0.63 | 0.75 | −0.55 | 0.75 |

| Rumphi | −1.19* | 0.61 | −0.88 | 0.59 | −0.84 | 0.59 | −2.78*** | 0.65 | −2.72*** | 0.65 | −2.72*** | 0.65 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Currently married (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | −2.24*** | 0.63 | −2.15*** | 0.63 | −2.19*** | 0.63 | −2.10 | 1.50 | −1.95 | 1.50 | −2.05 | 1.52 |

| Never married | −0.89 | 1.99 | −1.30 | 2.04 | −1.05 | 1.99 | −2.41** | 1.04 | −2.47** | 1.03 | −2.60** | 1.05 |

| Household size | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.19** | 0.09 | 0.19** | 0.09 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Agricultural- own land (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Agricultural wage laborer | −0.65 | 0.93 | −0.58 | 0.92 | −0.55 | 0.92 | −1.14 | 1.23 | −1.15 | 1.23 | −0.84 | 1.25 |

| Salaried employment | −0.56 | 2.82 | −0.30 | 2.81 | −0.51 | 2.82 | 1.34 | 1.52 | 1.55 | 1.51 | 1.55 | 1.51 |

| Market work/sales | −0.45 | 0.83 | −0.40 | 0.83 | −0.32 | 0.82 | −0.48 | 1.13 | −0.20 | 1.12 | −0.01 | 1.13 |

| Handicraft production | 0.25 | 0.87 | 0.20 | 0.87 | 0.24 | 0.87 | −0.76 | 0.93 | −0.78 | 0.93 | −0.72 | 0.93 |

| Other | −0.79 | 0.74 | −0.67 | 0.74 | −0.72 | 0.74 | −0.42 | 0.94 | −0.32 | 0.93 | −0.16 | 0.93 |

| 2008 physical health | 0.21*** | 0.03 | 0.21*** | 0.03 | 0.21*** | 0.03 | 0.25*** | 0.04 | 0.26*** | 0.04 | 0.25*** | 0.04 |

| Total monthly participation | 0.06** | 0.03 | 0.04* | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Total annual participation | 0.04* | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Committee participation | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.18 | ||||||||

| N= | 1411 | 917 | ||||||||||

Notes:

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<0.10.

Two-tailed tests.

In Table 3A, we see that even after controlling for physical health in 2008 and other controls, greater overall monthly social participation in 2008 is associated with better 2010 physical health for women (p<.05) and men (p<0.10) in 2010. Greater participation in less frequent annual events is associated with better physical health for women in 2010 (p<0.10), but not for men. Membership in a greater number of groups is not associated with better physical health in 2010 for women or men.

In contrast with physical health, social participation is associated with worse mental health (Table 3B). Greater social participation in the previous month is not statistically significantly associated with mental health in 2010 for women or men. However, greater participation in the past year in 2008 predicts worse SF-12 mental health scores for women (p<.05) and men (p<0.10) in 2010. As with physical health, being a member of a greater number of groups in 2008 also does not predict SF-12 mental health scores in 2010 for women or men.

Table 3B.

OLS regression results for the association between 2008 social participation and 2010 mental health for MLSFH men and women

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Age | −0.05*** | 0.02 | −0.05** | 0.02 | −0.05** | 0.02 | −0.09*** | 0.02 | −0.09*** | 0.02 | −0.09*** | 0.02 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Primary | 0.86 | 0.70 | 0.89 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 0.71 | −0.89 | 0.92 | −0.85 | 0.92 | −1.01 | 0.91 |

| Secondary+ | 0.78 | 1.33 | 0.97 | 1.32 | 0.77 | 1.32 | −0.80 | 1.20 | −0.78 | 1.20 | −0.85 | 1.19 |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| Mchinji (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Balaka | −0.20 | 0.74 | −0.20 | 0.74 | −0.30 | 0.74 | −0.66 | 0.85 | −0.63 | 0.85 | −0.60 | 0.84 |

| Rumphi | 1.34* | 0.73 | 1.24* | 0.70 | 1.25* | 0.70 | −0.11 | 0.74 | −0.08 | 0.74 | −0.10 | 0.73 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Currently married (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | −1.78** | 0.75 | −1.84** | 0.75 | −1.88** | 0.75 | 0.12 | 1.71 | 0.29 | 1.71 | 0.34 | 1.72 |

| Never married | 0.46 | 2.35 | 0.19 | 2.41 | 0.60 | 2.35 | 0.71 | 1.18 | 0.71 | 1.17 | 1.14 | 1.19 |

| Household size | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Agricultural- own land (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Agricultural wage laborer | 0.78 | 1.10 | 0.86 | 1.09 | 0.83 | 1.09 | 0.44 | 1.40 | 0.41 | 1.40 | 0.32 | 1.41 |

| Salaried employment | 5.83* | 3.33 | 5.59* | 3.33 | 5.82* | 3.33 | −3.03* | 1.73 | −3.07* | 1.72 | −3.24* | 1.71 |

| Market work/sales | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.19 | 0.98 | 0.03 | 0.98 | −0.90 | 1.29 | −0.93 | 1.28 | −0.41 | 1.28 |

| Handicraft production | 1.11 | 1.03 | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.15 | 1.03 | 0.00 | 1.06 | −0.05 | 1.06 | 0.04 | 1.05 |

| Other | −0.54 | 0.88 | −0.59 | 0.87 | −0.59 | 0.87 | −0.99 | 1.07 | −0.90 | 1.06 | −0.95 | 1.05 |

| 2008 mental health | 0.16*** | 0.03 | 0.16*** | 0.03 | 0.15*** | 0.03 | 0.14*** | 0.04 | 0.14*** | 0.04 | 0.15*** | 0.04 |

| Total monthly participation | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| Total annual participation | −0.06** | 0.02 | −0.02* | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Committee participation | −0.13 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.20 | ||||||||

| N= | 1411 | 917 | ||||||||||

Notes:

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<0.10.

Two-tailed tests.

Next we compare the relationship between participation and health by age group, for those under 45 years and 45 years and older. Tables 4A and 4B present results for the “younger” Malawians (physical and mental health, respectively), and older respondents are shown in Tables 5A and 5B.

Table 4A.

OLS regression results for the association between 2008 social participation and 2010 physical health for MLSFH men and women less than 45 years old

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Age | −0.09 | 0.04 | −0.09** | 0.03 | −0.09** | 0.04 | −0.08* | 0.05 | −0.08* | 0.05 | −0.08* | 0.05 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Primary | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.68 | −0.57 | 1.10 | −0.57 | 1.10 | −0.48 | 1.10 |

| Secondary+ | 1.85* | 1.10 | 1.77 | 1.10 | 1.79 | 1.10 | −1.90 | 1.29 | −1.96 | 1.28 | −1.86 | 1.27 |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| Mchinji (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Balaka | −1.76** | 0.70 | −2.03*** | 0.70 | −1.69** | 0.69 | −0.47 | 0.86 | −0.48 | 0.86 | −0.55 | 0.85 |

| Rumphi | −2.97*** | 0.65 | −3.01*** | 0.63 | −2.79*** | 0.62 | −3.69*** | 0.68 | −3.65*** | 0.68 | −3.71*** | 0.68 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Currently married (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | −3.71 | 0.85 | −3.90 | 0.85 | −3.65 | 0.85 | 0.53 | 1.65 | 0.46 | 1.64 | 0.15 | 1.67 |

| Never married | −0.51 | 1.75 | −0.72 | 1.79 | −0.59 | 1.75 | −0.40 | 0.94 | −0.36 | 0.93 | −0.57 | 0.95 |

| Household size | −0.26** | 0.10 | −0.27** | 0.10 | −0.27** | 0.10 | −0.12 | 0.10 | −0.11 | 0.10 | −0.12 | 0.10 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Agricultural- own land (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Agricultural wage laborer | −0.71 | 1.01 | −0.72 | 1.00 | −0.63 | 1.01 | −2.31* | 1.31 | −2.30* | 1.31 | −1.80 | 1.33 |

| Salaried employment | 0.94 | 2.77 | 1.14 | 2.77 | 0.98 | 2.77 | 0.83 | 1.50 | 0.88 | 1.49 | 0.95 | 1.49 |

| Market work/sales | 0.55 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.79 | −0.91 | 1.00 | −0.88 | 0.99 | −0.68 | 0.99 |

| Handicraft production | 0.71 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.97 | 0.69 | 0.96 | −1.81* | 1.09 | −1.78 | 1.09 | −1.63 | 1.08 |

| Other | 1.04 | 0.84 | 1.23 | 0.83 | 1.05 | 0.83 | −0.83 | 1.02 | −0.79 | 1.01 | −0.57 | 1.01 |

| 2008 physical health | 0.10*** | 0.03 | 0.10*** | 0.03 | 0.10*** | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Total monthly participation | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Total annual participation | 0.17** | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Committee participation | −0.01 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.20 | ||||||||

| N= | 910 | 523 | ||||||||||

Notes:

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<0.10.

Two-tailed tests.

Table 4B.

OLS regression results for the association between 2008 social participation and 2010 mental health for MLSFH men and women less than 45 years old

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Age | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Primary | −0.05 | 0.87 | −0.01 | 0.87 | 0.09 | 0.88 | 0.16 | 1.47 | 0.17 | 1.47 | 0.16 | 1.45 |

| Secondary+ | 0.66 | 1.43 | 0.65 | 1.43 | 0.67 | 1.43 | 0.34 | 1.71 | 0.34 | 1.71 | 0.57 | 1.68 |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| Mchinji (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Balaka | −0.69 | 0.91 | −0.54 | 0.91 | −0.85 | 0.90 | −0.54 | 1.14 | −0.51 | 1.14 | −0.64 | 1.12 |

| Rumphi | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.81 | −0.10 | 0.91 | −0.01 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.89 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Currently married (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | −2.09* | 1.11 | −1.96* | 1.11* | −2.12 | 1.11 | 0.56 | 2.20 | 0.95 | 2.19 | 0.73 | 2.21 |

| Never married | 0.28 | 2.28 | −0.09 | 2.33 | 0.35 | 2.27 | 1.29 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.17 | 1.25 |

| Household size | 0.00 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.13 | −0.13 | 0.14 | −0.14 | 0.14 | −0.13 | 0.14 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Agricultural- own land (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Agricultural wage laborer | −0.46 | 1.32 | −0.25 | 1.30 | −0.31 | 1.31 | 0.30 | 1.75 | 0.24 | 1.74 | 0.17 | 1.75 |

| Salaried employment | 3.59 | 3.60 | 3.42 | 3.60 | 3.65 | 3.60 | −1.86 | 2.00 | −1.88 | 1.99 | −1.96 | 1.96 |

| Market work/sales | 0.27 | 1.04 | 0.24 | 1.03 | 0.23 | 1.03 | −0.32 | 1.33 | −0.30 | 1.31 | 0.38 | 1.31 |

| Handicraft production | 0.16 | 1.25 | −0.03 | 1.26 | 0.24 | 1.25 | −0.35 | 1.44 | −0.38 | 1.44 | −0.33 | 1.42 |

| Other | 0.19 | 1.09 | 0.09 | 1.08 | 0.20 | 1.08 | 1.34 | 1.36 | 1.49 | 1.35 | 1.27 | 1.33 |

| 2008 mental health | 0.14*** | 0.04 | 0.14*** | 0.04 | 0.14*** | 0.04 | 0.15*** | 0.05 | 0.15*** | 0.05 | 0.15*** | 0.05 |

| Total monthly participation | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| Total annual participation | −0.13 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Committee participation | −0.22 | 0.29 | −0.25 | 0.26 | ||||||||

| N= | 910 | 523 | ||||||||||

Notes:

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<0.10.

Two-tailed tests.

Table 5A.

OLS regression results for the association between 2008 social participation and 2010 physical health for MLSFH men and women 45 years or older

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Age | −0.20*** | 0.04 | −0.22*** | 0.04 | −0.22*** | 0.05 | −0.26*** | 0.05 | −0.27*** | 0.05 | −0.28*** | 0.05 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Primary | −0.21 | 1.10 | −0.21 | 1.10 | −0.11 | 1.11 | 0.05 | 1.21 | 0.09 | 1.23 | 0.14 | 1.23 |

| Secondary+ | 4.18 | 3.36 | 4.21 | 3.46 | 5.19 | 3.38 | 2.36 | 1.98 | 2.46 | 2.00 | 2.75 | 2.03 |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| Mchinji (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Balaka | 2.09* | 1.19 | 2.38** | 1.19 | 2.40** | 1.19 | −0.35 | 1.27 | −0.49 | 1.30 | −0.26 | 1.29 |

| Rumphi | 2.68** | 1.24 | 3.16** | 1.23 | 3.10** | 1.23 | −1.50 | 1.20 | −1.41 | 1.20 | −1.26 | 1.21 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Currently married (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | −0.53 | 0.97 | −0.32 | 0.98 | −0.41 | 0.98 | −4.43* | 2.65 | −4.27 | 2.65 | −4.32 | 2.67 |

| Never married 1 | ||||||||||||

| Household size | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.33** | 0.15 | 0.29** | 0.15 | 0.30** | 0.15 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Agricultural- own land (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Agricultural wage laborer | 0.64 | 1.81 | 0.86 | 1.81 | 0.78 | 1.81 | −1.39 | 2.28 | −1.10 | 2.28 | −1.04 | 2.29 |

| Salaried employment | −8.73 | 7.01 | −7.54 | 7.03 | −7.75 | 7.08 | 1.98 | 3.13 | 1.86 | 3.14 | 2.07 | 3.17 |

| Market work/sales | −3.38 | 2.31 | −3.17 | 2.33 | −2.84 | 2.31 | 3.33 | 3.80 | 3.71 | 3.80 | 3.68 | 3.82 |

| Handicraft production | −0.10 | 1.63 | −0.09 | 1.63 | −0.09 | 1.63 | −0.17 | 1.54 | −0.26 | 1.55 | −0.33 | 1.55 |

| Other | −2.78** | 1.35 | −2.72** | 1.36 | −2.81** | 1.37 | 0.57 | 1.70 | 0.87 | 1.69 | 0.95 | 1.70 |

| 2008 physical health | 0.38*** | 0.05 | 0.38*** | 0.05 | 0.39** | 0.05 | 0.30*** | 0.06 | 0.32*** | 0.06 | 0.31*** | 0.06 |

| Total monthly participation | 0.11* | 0.06 | 0.09** | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Total annual participation | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| Committee participation | −0.13 | 0.43 | −0.09 | 0.32 | ||||||||

| N= | 501 | 394 | ||||||||||

Notes:

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<0.10.

Two-tailed tests;

No adults aged 45 and older were never married, so this category dropped out of the regression models above.

Table 5B.

OLS regression results for the association between 2008 social participation and 2010 mental health for MLSFH men and women 45 years or older

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Age | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.13** | 0.05 | −0.12** | 0.05 | −0.10** | 0.05 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Primary | 2.37* | 1.22 | 2.33* | 1.22 | 2.47** | 1.23 | −1.32 | 1.25 | −1.22 | 1.26 | −1.70 | 1.25 |

| Secondary+ | −2.50 | 3.74 | −1.15 | 3.83 | −2.87 | 3.73 | −1.30 | 2.04 | −1.16 | 2.06 | −2.77 | 2.07 |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| Mchinji (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Balaka | 1.13 | 1.33 | 1.05 | 1.32 | 1.00 | 1.31 | −0.49 | 1.32 | −0.41 | 1.35 | −0.08 | 1.31 |

| Rumphi | 2.32* | 1.39 | 2.13 | 1.37 | 2.24 | 1.37 | 0.06 | 1.27 | −0.04 | 1.26 | −0.17 | 1.25 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Currently married (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | −1.36 | 1.08 | −1.52 | 1.08 | −1.54 | 1.08 | −0.41 | 2.74 | −0.54 | 2.74 | 0.28 | 2.72 |

| Never married 1 | ||||||||||||

| Household size | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.16 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Agricultural- own land (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Agricultural wage laborer | 3.82* | 2.01 | 3.72 | 2.01 | 3.68 | 2.00 | 0.76 | 2.34 | 0.66 | 2.33 | 0.47 | 2.31 |

| Salaried employment | 15.25* | 7.78 | 13.99* | 7.76 | 14.90* | 7.80 | −6.14* | 3.25 | −6.08* | 3.25 | −7.28** | 3.24 |

| Market work/sales | −0.37 | 2.57 | 0.08* | 2.58 | −0.66* | 2.55 | −2.79 | 3.94 | −2.95 | 3.93 | −2.15 | 3.90 |

| Handicraft production | 2.76 | 1.81 | 2.87 | 1.81 | 2.72 | 1.80 | 0.68 | 1.60 | 0.60 | 1.61 | 0.70 | 1.58 |

| Other | −1.49 | 1.51 | −1.52 | 1.50 | −1.62 | 1.51 | −3.71** | 1.76 | −3.74** | 1.75 | −3.97 | 1.73 |

| 2008 mental health | 0.18*** | 0.05 | 0.19*** | 0.05 | 0.18*** | 0.05 | 0.13** | 0.06 | 0.13** | 0.06 | 0.13** | 0.06 |

| Total monthly participation | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| Total annual participation | −0.06** | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| Committee participation | −0.13 | 0.48 | 0.92*** | 0.32 | ||||||||

| N= | 501 | 394 | ||||||||||

Notes:

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<0.10.

Two-tailed tests;

No adults aged 45 and older were never married, so this category dropped out of the regression models above.

Overall we find that the relationship between social participation and health appears to be more important for older rural Malawians. The results for the association between social participation and mental and physical health for younger individuals shows only one statistically significant relationship: annual participation in social events predicts better physical health for women in 2010 (p<.05). Our results are considerably different for older Malawians. In Table 5A we find that participation in monthly social events is associated with better physical health scores for both older women (p<0.10) and men (p<.05). Interestingly, participation in annual events is linked to worse mental health scores for older women (p<.05) whereas it is linked to better physical health scores for younger women (Table 5B). Further, we finally see that village committee participation is an important, and strong, predictor of mental health, but only for men 45 and older (p<.01).

Lastly, turning to the relationship between religious participation and heath (Table 6A for physical health and 6B for mental), we find that participation is again generally more important among men and women over age 45. We see an overall positive relationship between 2008 religious participation and physical health for women (p<.05), but not men. This relationship is consistent for men and women over age 45, in which both men (p<.05) and women (p<.05) with more frequent religious participation have better physical health in 2008. However, men less than 45 have the opposite relationship with participation and health than older men: greater participation among those less than 45 is associated with worse physical health in 2010 (p<.05). The relationship between participation and mental health is weaker than physical health: the only statistically significant relationship is again among women age 45 and older, in which women with greater participation have better mental health (p<.05).

Table 6A.

OLS regression results for the association between 2008 religious participation and 2010 physical health for MLSFH men and women

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Less than 45 | 45 or more | All | Less than 45 | 45 or more | |||||||

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Age | 0.02 | −10.88 | −0.09** | 0.03 | −0.19*** | 0.05 | −0.20*** | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.29*** | 0.05 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Primary | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 0.67 | 0.14 | 1.10 | −0.22 | 0.80 | −0.74 | 1.10 | −0.41 | 1.20 |

| Secondary+ | 1.77 | 1.12 | 1.95* | 1.10 | 4.82 | 3.35 | −1.09 | 1.04 | −2.00 | 1.27 | 2.03 | 1.94 |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| Mchinji (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Balaka | −0.11 | 0.62 | −1.65** | 0.69 | 2.47** | 1.19 | −0.53 | 0.75 | −0.21 | 0.85 | −0.53 | 1.27 |

| Rumphi | −0.90 | 0.59 | −2.83*** | 0.62 | 3.12** | 1.23 | −2.64*** | 0.64 | −3.45*** | 0.68 | −1.41 | 1.19 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Currently married (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | −2.18*** | 0.63 | −3.73*** | 0.85 | −0.43 | 0.98 | −1.85 | 1.48 | 0.59 | 1.62 | −4.04 | 2.60 |

| Never married 1 | −0.97 | 1.98 | −0.58 | 1.75 | −2.50** | 1.02 | −0.26 | 0.93 | ||||

| Household size | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.26** | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.19** | 0.09 | −0.11 | 0.10 | 0.29* | 0.15 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Agricultural- own land (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Agricultural wage laborer | −0.41 | 0.92 | −0.59 | 1.01 | 1.10 | 1.82 | −1.23 | 1.22 | −2.42* | 1.30 | −1.23 | 2.23 |

| Salaried employment | −0.45 | 2.81 | 0.93 | 2.77 | −7.38 | 7.04 | 1.49 | 1.49 | 0.73 | 1.49 | 1.56 | 3.07 |

| Market work/sales | −0.18 | 0.83 | 0.66 | 0.79 | −2.80 | 2.30 | −0.31 | 1.11 | −0.72 | 0.98 | 3.05 | 3.72 |

| Handicraft production | 0.41 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 0.96 | 0.37 | 1.63 | −0.97 | 0.92 | −1.80* | 1.08 | −0.64 | 1.52 |

| Other | −0.77 | 0.74 | 0.98 | 0.83 | −2.59 | 1.37 | −0.45 | 0.93 | −0.76 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.68 |

| 2008 physical health | 0.21*** | 0.03 | 0.10*** | 0.03 | 0.36*** | 0.05 | 0.24** | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.29*** | 0.06 |

| Religious participation | 0.78** | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.34 | 1.06** | 0.62 | 0.11 | 0.32 | −0.80** | 0.35 | 1.06** | 0.54 |

| N= | 1411 | 910 | 501 | 917 | 523 | 394 | ||||||

Notes:

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<0.10.

Two-tailed tests;

No adults aged 45 and older were never married, so this category dropped out of the regression models above.

Table 6B.

OLS regression results for the association between 2008 religious participation and 2010 mental health for MLSFH men and women

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Less than 45 | 45 or more | All | Less than 45 | 45 or more | |||||||

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Age | −0.05** | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.09*** | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.13** | 0.05 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Primary | 1.02 | 0.70 | 0.17 | 0.88 | 2.42** | 1.22 | −0.76 | 0.92 | 0.15 | 1.47 | −1.15 | 1.26 |

| Secondary+ | 0.67 | 1.33 | 0.62 | 1.44 | −3.48 | 3.70 | −0.77 | 1.20 | 0.27 | 1.70 | −1.30 | 2.04 |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| Mchinji (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Balaka | −0.21 | 0.74 | −0.68 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 1.32 | −0.79 | 0.86 | −0.60 | 1.14 | −0.72 | 1.34 |

| Rumphi | 1.21* | 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 2.14 | 1.37 | −0.20 | 0.74 | −0.11 | 0.90 | −0.14 | 1.27 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Currently married (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | −1.80** | 0.75 | −2.20* | 1.12 | −1.31 | 1.08 | 0.05 | 1.70 | 0.51 | 2.17 | −0.44 | 2.73 |

| Never married 1 | 0.85 | 2.36 | 0.49 | 2.28 | 0.73 | 1.17 | 1.30 | 1.25 | ||||

| Household size | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.10 | −0.13 | 0.14 | 0.27* | 0.16 |

| Occupation | ||||||||||||

| Agricultural- own land (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Agricultural wage laborer | 0.98 | 1.10 | −0.27 | 1.31 | 4.08** | 2.01 | 0.38 | 1.40 | 0.18 | 1.74 | 0.62 | 2.33 |

| Salaried employment | 5.74* | 3.34 | 3.64 | 3.62 | 15.04* | 7.75 | −3.11* | 1.72 | −1.93 | 1.99 | −6.24* | 3.24 |

| Market work/sales | −0.01 | 0.98 | 0.10 | 1.04 | −0.47 | 2.55 | −0.97 | 1.27 | −0.32 | 1.31 | −2.98 | 3.92 |

| Handicraft production | 1.17 | 1.03 | 0.26 | 1.26 | 2.81 | 1.80 | 0.01 | 1.06 | −0.37 | 1.44 | 0.71 | 1.60 |

| Other | −0.57 | 0.88 | 0.14 | 1.09 | −1.23 | 1.51 | −0.97 | 1.06 | 1.37 | 1.34 | −3.83** | 1.77 |

| 2008 mental health | 0.15*** | 0.03 | 0.14*** | 0.04 | 0.16*** | 0.05 | 0.14*** | 0.04 | 0.15*** | 0.05 | 0.13** | 0.06 |

| Religious participation | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.44 | 1.37** | 0.67 | −0.10 | 0.36 | −0.27 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.57 |

| N= | 1411 | 910 | 501 | 917 | 523 | 394 | ||||||

Notes:

p<.01,

p<.05,

p<0.10.

Two-tailed tests;

No adults aged 45 and older were never married, so this category dropped out of the regression models above.

Discussion

Overall, our results for the relationship between social participation and health are mixed. While evidence shows that social participation generally improves physical health, we find that greater social participation in annual events is associated with worse mental health for men and women. Given that research generally points to the beneficial impact of social participation on heath (Helliwell and Putnam 2004; Hyyppä and Mäki 2003; Lindström et al. 2001; Veenstra 2000), our results are potentially surprising. We also find that that age moderates the relationship between social participation and health. When dividing our sample at age 45, we find limited evidence of an association between social participation and health for younger individuals, but social participation appears to be importantly related to health among those 45 and older—and for all four social participation measures.

Research on social participation and health has struggled to identify the mechanisms behind this relationship. Although identifying mechanisms was not a goal of this research, our results fit within literature that suggests some factors that connect participation and health. Given the literature, the positive relationship between participation and physical health is not surprising in a Malawian setting: in the absence of a public transport system, individuals may have to walk relatively long distances to attend venues of social participation, exercise which could improve individual health. In addition, these venues for social participation could be locations for engaging in transfers, like buying food or sharing information about a new medical clinic with a friend, which may also improve individual health.

While research showing a negative relationship between social participation and health is limited, some suggest that participation can be detrimental to mental health, particularly if participation may lead to obligations to provide financial and non-financial support to others in the community (Kawachi and Berkman 2001). Given the importance and frequency of such transfers in rural Malawi (Kohler et al. 2012; Swidler and Watkins 2007), the negative impact of social participation on mental health is believable in the Malawian context. In addition, participation in “annual” activities, such as weddings, dramas about family planning or HIV/AIDS, and political meetings could also be nerve-racking. It is nearly impossible to remain anonymous in a Malawian village and attending such events, and at least for these dramas and political meetings, one’s attendance might be heavily scrutinized by others in the village—potentially leading to rumors being spread and subsequent social stigma (Watkins 2004). In addition, some events, such as dramas about HIV infection, could heighten fear of being HIV infected (Anglewicz and Kohler 2009) and negatively impact mental health. These effects may be exacerbated for older women because they are often expected to organize these events, which could be stressful.

On this last point, it is possible that broader gendered patterns in rural Malawian social participation—despite limited scholarly investigation on this subject—could be at the heart of our observed differences in health outcomes. The descriptive statistics in Table 2 suggest that men attend bars and participate much more frequently in dramas, weddings, and political meetings than women. It is well-known that men account for the vast majority of patrons in rural Malawian bars, and women who frequent bars are typically involved commercial sex work (Watkins 2004); the same goes for dance clubs (as opposed to ordinary bars with a pool table and little else). Also, while women in rural Malawi discourage their husbands from attending bars (Schatz 2005), women occasionally engage in, female-only, gift-giving parties where dancing is common. Paz Soldan (2004) offers an additional clue about gendered social participation—men are more likely to first learn about family planning strategies through health-related dramas than women, who tend to learn these strategies at hospitals or medical clinics. Since Paz Soldan (2004) indicates that men also often discuss family planning issues informally with friends, rather than formally with medical practitioners, it is possible that men encourage one another to attend these health dramas. Even occupational status could moderate this relationship. Our results indicate that salaried employment for older women is positively associated with health, with the opposite association for men. This might reflect the different types of salaried work that rural Malawian women and men engage in, which could be particularly stressful for men. However, we do not have enough cases to test the extent to which salaried employment could moderate the relationship between social participation and health (or how social participation could moderate the relationship between occupation and health). Since we can do little more than make “informed speculations” on the mechanisms linking social participation and health, and with no research to reconcile other gendered disparities in social participation in rural Malawi, we call for more research to provide further details on these phenomena.

We emphasize the importance of methods and study design in research on participation and health. The most notable literature on the relationship between social participation and health may be misled by the use of cross-sectional data, and our use of longitudinal data may overcome some of these limitations. Further, with limited comparisons on this relationship in LICs, we believe that our Malawian data offer an excellent case for theoretical expansion. We also enlarge the scope of social participation beyond the conventional measure of the number of group memberships an individual has, or religious participation, to include more active and culturally relevant forms of social participation found in Malawi such as funerals, drama performances, bars, places to dance, markets, weddings, and political meetings. We bring to light intriguing and important gender and age differences in the process as well—many of which have not been explored in health research.

Yet, while adding to this body of literature, there are important limitations of this research. First, our measures of social participation may not capture all relevant venues. If unmeasured venues—like meeting at a village well to wash clothes—are substantively different from those in this paper, it may affect our results. Although we benefit from longitudinal data, our use of lagged physical and mental health variables in our analyses can only diminish the effect of selection into being able to participate in social events and subsequent health outcomes based on one’s health status; we cannot account for potentially important, yet unobserved, variables that could moderate and mediate the extent to which social participation predicts health outcomes and these results are biased as such. Hence, we cannot claim social participation causes positive or negative effects on physical and mental health.

Any longitudinal approach should consider the possibility of attrition bias. There are 667 individuals who were interviewed in 2008 but not re-interviewed in 2010. Of these 667 who were not re-interviewed, the most prominent reasons for attrition are migration (42.2%), temporary absence (16.0%), death (10.1%), and refusal (8.1%). To evaluate whether these 667 individuals systematically bias the sample, we compare 2008 participation measures for individuals interviewed in both 2008 and 2010 with those interviewed only in 2008 (Appendix Table 2). Results of this analysis show relatively few differences in social participation between individuals who were re-interviewed and those who left the MLSFH sample by 2010, which suggests that any bias due to attrition is minimal.

Despite these limitations, we believe that these longitudinal data offer rare and valuable insight into the ways in which social participation influences health outcomes, while reducing selection effects that often leave the direction of this relationship unclear. Additionally, given the cultural importance of social interactions in Malawi, these data allow us to evaluate how a pertinent aspect of individuals’ social livelihoods influences their lives more-literally. By conducting our research in Malawi—a poor, predominantly rural nation where social participation is a major part of its society’s fabric and where individuals must rely on one another for survival—we believe that we have found a theoretically important venue to assess how social participation predicts health outcomes when considering that the most influential research on this relationship has come from HICs, such as the US, where social participation is no longer as important in individuals’ daily lives. In sum, our results suggest that not all forms of social participation benefit all aspects of one’s health and we caution that there are potentially negative health consequences as a result of participating in certain types of social events, which certainly warrants further investigation in Malawi, other LICs, and HICs. Social participation should not be viewed as a public health strategy, nor as a substitute to medical health services, especially in places like Malawi where these services are underfunded and overburdened. Instead, researchers need to continue to scrutinize why some forms of social participation improve or diminish varying aspects of individual health, with the hope of identifying how social participation could become a complementary component to improving one’s physical and mental health.

Biographies

Tyler W. Myroniuk recently received his PhD in Sociology from the University of Maryland and is currently a postdoctoral research associate in the Population Studies & Training Center at Brown University. His research interests include the determinants of fertility, migration, aging, health, and educational attainment, as well as evaluating the impacts of various aspects of social capital on livelihood outcomes, in sub-Saharan African contexts and India.

Philip Anglewicz is an assistant professor in the Department of Global Health Systems and Development at Tulane University. His primary research interest is the relationship between migration and health in developing countries, which he has pursued in several contexts. In 2007, Anglewicz conducted a study on the relationship between internal migration, marriage and HIV infection in Malawi, which involved collecting survey and HIV biomarker data for over 500 migrants in Malawi. In his current research, Anglewicz is investigating the relationship between rural-urban migration and health in Thailand, and the effect of Hurricane Katrina on migration patterns of the Vietnamese population in New Orleans. In addition to migration, Anglewicz is also engaged in research on the effects of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on household composition and social support systems in sub-Saharan Africa, biomarker measures of health, and survey methodology.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

Regression results for relationship between 2008 social participation and 2010 health for specific activities, MLSFH men and women

| Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Mental | Physical | Mental | |

| Monthly activities | ||||

| Funeral | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Drama | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.08 |

| Bar | 0.05 | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.02 |

| Dance | −0.29 | −0.22 | 0.40 | −0.14 |

| Market | 0.07* | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.02 |

| Annual activities | ||||

| Wedding | 0.09 | −0.28 | 0.01 | −0.03 |

| Family Planning or HIV Drama | 0.09** | −0.07* | 0.10 | 0.13* |

| Political meeting | 0.01 | −0.09* | −0.01 | −0.05 |

Notes:

p<.01,

p<.05.

Two-tailed tests; regression models control for age, education, region of residence, marital status, household size, occupation, and 2008 mental or physical health status.

Appendix Table 2.

Analysis of attrition bias: differences in 2008 participation measures between individuals interviewed in 2008 and 2010 and those interviewed only in 2008, MLSFH men and women

| Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-attrition | Attrition | Non-attrition | Attrition | |

| Monthly activities | ||||

| Funeral | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.6 |

| Drama | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Bar | 0.3 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 2.0 |

| Dance | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Market | 5.8 | 4.7** | 7.8 | 8.5 |

| Total monthly | 10.2 | 8.6** | 15.4 | 15.5 |

| Annual activities | ||||

| Wedding | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 0.8 |

| Family Planning or HIV Drama | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| Political meeting | 1.3 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 1.2* |

| Total annual | 2.7 | 2.3 | 5.2 | 3.1* |

| Committee participation | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| Religious participation | 4.5 | 4.4** | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| N= | 1411 | 384 | 917 | 283 |

Notes:

p<.01

p<.05.

Two-tailed tests.

Footnotes

The authors would like to thank Susan Watkins, Jane Menken, Hans-Peter Kohler, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. The Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) has been supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Development (grants R03 HD058976, R21 HD050652, R01 HD044228, R01 HD053781, R21 HD071471), the National Institute on Aging (grant P30 AG12836), the Boettner Center for Pensions and Retirement Security at the University of Pennsylvania, and the National Institute of Child Health and Development Population Research Infrastructure Program (grant R24 HD-044964), all at the University of Pennsylvania. The MLSFH has also been supported by pilot funding received through the Penn Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), supported by NIAID AI 045008, and the Penn Institute on Aging. The MLSFH study was approved by the IRB at the University of Pennsylvania and the Malawi National Health Sciences Research Council (NHSRC). This paper was also supported indirectly by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development grant R24-HD041041, Maryland Population Research Center, and R24-HD041020, Brown University Population Studies & Training Center.

Between 1998 and 2004 the MLSFH was known as the Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MDICP).

For a graph of physical and mental health by age for MLSFH men and women, please see Kohler et al. (2014).

As shown in Appendix Table 1, we examined the relationship between each individual measure of social participation and our two health outcomes. The results show significant relationships for very few of these individual measures: only 5 of 32 individual venues were significantly associated with mental or physical health for men or women (at p<.05). The fact that the aggregate measures were more likely to have a statistically significant association with health seem to imply that the impact of social participation on health involves a range of venues, as opposed to being influenced by strong relationships with relatively few venues.

We also tested several other measures in these regressions, such as wealth, HIV status, perceived HIV status, number of children, and ethnicity. These variables were not significantly associated with health in most models and were therefore not included in the final set of models.

We ran the interactions between participation and age for all models. Results for this interaction were statistically significant (at least p<0.10) for monthly participation (mental and physical health, both men and women), annual participation (physical health for women), committee participation (physical health for men and women), and religious activities (mental and physical health, both men and women). The significance of this interaction term in the majority of models justifies our approach to run separate models for the two age groups of interest.

Contributor Information

Tyler W. Myroniuk, Brown University, Population Studies & Training Center 68 Waterman Street, Providence, RI 02912

Philip Anglewicz, Tulane University, Department of Global Health Systems and Development.

References

- Adler Paul S, Kwon Seok-Woo. Social Capital: Prospects for a New Concept. Academy of Management Review. 2002;27(1):17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch Kristine J, Blandon Alysia Y, Antonucci Toni C. Social Networks among Men and Women: The Effects of Age and Socioeconomic Status. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60(6):S311–S317. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.s311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz Philip, Kohler Hans-Peter. Overestimating HIV Infection: The Construction and Accuracy of Subjective Probabilities of HIV Infection in Rural Malawi. Demographic Research. 2009;20(6):65–96. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2009.20.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz Philip, Adams Jimi, Onyango Francis, Watkins Susan, Kohler Hans-Peter. The Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project 2004–06: Data Collection, Data quality, and Analysis of Attrition. Demographic Research. 2009;20(21):503–540. doi: 10.4054/demres.2009.20.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avlund Kirsten, Holstein Bjorn E, Mortensen Erik Lykke, Schroll Marianne. Active Life in Old Age. Combining Measures of Functional Ability and Social Participation. Danish Medical Bulletin. 1999;46(4):345–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignami-Van Assche Simona, Reniers Georges, Weinreb Alexander A. An Assessment of the KDICP and MDICP Data Quality: Interviewer Effects, Question Reliability and Sample attrition. Demographic Research. 2003;1(2):31–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu Pierre. The Forms of Capital. In: Richardson JE, editor. Handbook of Theory Research for the Sociology of Education. London: Greenwood Press; 1986. pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bukov Aleksej, Maas Ineke, Lampert Thomas. Social Participation in Very Old Age Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Findings From BASE. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57(6):P510–P517. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.p510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Catherine, Williams B, Gilgen David. Is Social Capital a Useful Conceptual Tool for Exploring Community Level Influences on HIV Infection? An Exploratory Case Study from South Africa. AIDS Care. 2002;14(1):41–54. doi: 10.1080/09540120220097928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattell Vicky. Poor People, Poor Places, and Poor Health: The Mediating Role of Social Networks and Social Capital. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;52(10):1501–1516. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman James Samuel. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell Benjamin, Laumann Edward O, Philip Schumm L. The Social Connectedness of Older Adults: A National Profile. American Sociological Review. 2008;73(2):185–203. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell Benjamin. Age Trends in Daily Social Contact Patterns. Research on Aging. 2011;33(5):598–631. [Google Scholar]

- Dalgard Odd Steffen, Håheim Lise Lund. Psychosocial Risk Factors and Mortality: a Prospective Study with Special Focus on Social Support, Social Participation, and Locus of Control in Norway. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1998;52(8):476–481. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.8.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim Émile. In: Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Spaulding John A, Simpson George., translators. New York: The Free Press; [1897] 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Feld Scott L. The Focused Organization of Social Ties. American Journal of Sociology. 1981;86(5):1015–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Forster Peter G. Culture, Nationalism, and the Invention of Tradition in Malawi. Journal of Modern African Studies. 1994;32(3):477–477. [Google Scholar]

- Gandek Barbara, Ware John E, Aaronson Neil K, Apolone Giovanni, Bjorner Jakob B, Brazier John E, Bullinger Monika, et al. Cross-validation of Item Selection and Scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in Nine Countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51(11):1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerland Patrick. PhD dissertation, Program in Population Studies. Princeton University; Princeton, NJ: 2006. Effects of Social Interactions on Individual AIDS-Prevention Attitudes and Behaviors in Rural Malawi. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson Simon, Terceira Nicola, Mushati Phyllis, Nyamukapa Constance, Campbell Catherine. Community Group Participation: Can it Help Young Women to Avoid HIV? An Exploratory Study of Social Capital and School Education in Rural Zimbabwe. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58(11):2119–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleringer Stephane, Kohler Hans-Peter. Social Networks, Perceptions of Risk, and Changing Attitudes Towards HIV/AIDS: New Evidence from a Longitudinal Study using Fixed-effects Analysis. Population Studies. 2005;59(3):265–282. doi: 10.1080/00324720500212230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell John F, Putnam Robert D. The Social Context of Well-being. Philosophical Transactions-Royal Society of London Series B Biological Sciences. 2004;359:1435–1446. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh Ning. Perceived Risk of HIV Infection and Mental Health in Rural Malawi. Demographic Research. 2013;28(13):373–408. [Google Scholar]

- Hyyppä Markku T, Mäki Juhani. Social Participation and Health in a Community Rich in Stock of Social Capital. Health Education Research. 2003;18(6):770–779. doi: 10.1093/her/cyf044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi Ichiro, Kennedy Bruce P, Lochner Kimberly, Prothrow-Stith Deborah. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(9):1491–1498. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.9.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi Ichiro, Kennedy Bruce P, Glass Roberta. Social Capital and Self-rated Health: A Contextual Analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(8):1187–1193. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi Ichiro, Berkman Lisa F. Social Ties and Mental Health. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler Hans-Peter, Behrman Jere R, Watkins Susan Cotts. Social Networks and HIV/AIDS Risk Perceptions. Demography. 2007;44(1):1–33. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler Hans-Peter, Watkins Susan C, Behrman Jere R, Anglewicz Philip, Kohler Iliana V, Thornton Rebecca L, Mkandawire James, Honde Hastings, Hawara Augustine, Chilima Ben, Bandawe Chiwoza, Mwapasa Victor. Cohort Profile: The Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler Iliana, Kohler Hans-Peter, Anglewicz Philip, Behrman Jere. Intergenerational Transfers in the Era of HIV/AIDS: Evidence from Rural Malawi. Demographic Research. 2012;27(27):775–834. doi: 10.4054/demres.2012.27.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Nan. Building a Network Theory of Social Capital. Connections. 1999;22(1):28–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lindström Martin, Hanson Bertil S, Östergren Per-Olof. Socioeconomic Differences in Leisure-time Physical Activity: The Role of Social Participation and Social Capital in Shaping Health Related Behaviour. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;52(3):441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner Kimberly A, Kawachi Ichiro, Brennan Robert T, Buka Stephen L. Social Capital and Neighborhood Mortality Rates in Chicago. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(8):1797–1805. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden Peter V. Core Discussion Networks of Americans. American Sociological Review. 1987;52(1):122–131. [Google Scholar]

- Mercken Liesbeth, Snijders Tom AB, Steglich Christian, Vartiainen Erkki, De Vries Hein. Dynamics of Adolescent Friendship Networks and Smoking Behavior. Social Networks. 2010;32(1):72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt Terrie E. Teen-aged Mothers in Contemporary Britain. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43(6):727–742. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan David L. Age Differences in Social Network Participation. Journal of Gerontology. 1998;43(4):S129–S137. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.4.s129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Vicente. A Critique of Social Capital. International Journal of Health Services. 2002;32(3):423–432. doi: 10.2190/6U6R-LTVN-FHU6-KCNU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nummela Olli, Sulander Tommi, Rahkonen Ossi, Karisto Antti, Uutela Antti. Social Participation, Trust and Self-rated Health: A Study among Ageing People in Urban, Semi-urban and Rural settings. Health & Place. 2008;14(2):243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne Collin F, Mkandawire James, Kohler Hans-Peter. Disability Transitions and Health Expectancies among Adults 45 Years and Older in Malawi: A Cohort-based Model. PLoS medicine. 2013;10(5):e1001435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz Soldan Valerie A. How Family Planning Ideas are Spread Within Social Groups in Rural Malawi. Studies in Family Planning. 2004;35(4):275–290. doi: 10.1111/j.0039-3665.2004.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips Derek L. Mental Health Status, Social Participation, and Happiness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1967;8(4):285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronyk Paul M, Harpham Trudy, Morison Linda A, Hargreaves James R, Kim Julia C, Phetla Godfrey, Watts Charlotte H, Porter John D. Is Social Capital Associated with HIV Risk in Rural South Africa? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66(9):1999–2010. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam Robert D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]