Abstract

Recent analyses have found that coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) portends a poor prognosis in patients with and without obstructive epicardial coronary artery disease (CAD). Chest pain in the absence of epicardial CAD is a common entity. Angina caused by CMD, microvascular angina (MVA), is often indistinguishable from that caused by obstructive epicardial CAD. The recent emergence of noninvasive techniques that can identify CMD, such as stress positron-emission tomography (PET) and cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) myocardial perfusion imaging, allow improved identification of MVA. Using these tools, higher risk patients with MVA can be differentiated from those at lower risk in the heterogeneous population historically labeled as cardiac syndrome X. Likewise, MVA can be diagnosed in those with obstructive epicardial CAD who have persistent angina despite successful revascularization. There is little evidence to support current treatment strategies for MVA and current literature has not clearly defined CMD or whether therapy improves prognosis.

Keywords: coronary microvascular dysfunction, microvascular angina, therapeutics, prognosis

Introduction

When addressing angina pectoris, the majority of attention and research has focused on pathology of the epicardial coronary arteries. Although the importance of the coronary microcirculation in maintaining appropriate myocardial perfusion has been recognized for several decades, the substantial morbidity of coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) has not been appreciated until recently. Traditionally, the assessment of risk severity in coronary artery disease (CAD) has focused on the presence and extent of epicardial coronary stenosis, the magnitude of inducible myocardial ischemia, and the degree of left ventricular dysfunction.[1] Recently, several studies have shown that CMD among patients with and without obstructive CAD denotes a poor prognosis with higher rates of MACE [1–7]. CMD can occur in four separate clinical settings: 1) in the absence of obstructive epicardial CAD and structural heart disease; 2) in the presence of structural heart disease; 3) in the presence of obstructive epicardial CAD; and 4) secondary to iatrogenic causes [8].

Chest pain without obstructive epicardial CAD is a common entity, occurring in up to 30% of patients undergoing invasive coronary angiography for chest pain. Patients who present with angina pectoris in the absence of apparent cardiac or systemic disease have traditionally been characterized as having cardiac syndrome X. This syndrome is heterogeneous, and different etiologies for cardiac syndrome X likely have different prognoses and optimal treatments. One potential pathophysiologic mechanism for symptoms in these patients is CMD, which results in microvascular angina (MVA) [9, 10]. Over the last two decades, noninvasive techniques for assessing CMD have evolved. Despite this, there is little data on what therapies are effective to treat the symptoms of MVA and alter the prognostic impact of CMD [11]. Furthermore, there is no standardized definition for CMD. In this review we will summarize the current literature on the definition and diagnosis of CMD, the prognosis of patients with CMD with and without concomitant CAD, and the treatment of CMD and MVA.

Clinical Presentation and Risk Factors of MVA and CMD

The clinical presentation of MVA is similar to chest pain with obstructive epicardial CAD. MVA is highly prevalent, encompassing an estimated 50% of patients with angina without obstructive epicardial CAD [11–14]. MVA should be suspected in patients presenting with typical chest pain who are found to have no obstructive epicardial CAD on coronary angiography, especially in those patients with stress testing indicative of myocardial ischemia. Patients with MVA have also been shown to have poor or slow response to short acting nitrates [9–15]. However, MVA is just one of several causes of chest pain in patients without obstructive epicardial CAD. The pathophysiology of chest pain without obstructive epicardial CAD can be divided into three groups: 1) non-cardiac; 2) cardiac non-ischemic; and 3) cardiac ischemic. There are multiple causes of non-cardiac chest pain, including gastrointestinal, pulmonary, musculoskeletal, and psychiatric. Cardiac non-ischemic pain can stem from pericardial pathologies and/or inappropriate pain perception. Cardiac ischemic etiologies include MVA, coronary spasm, and myocardial bridging [11]. Cardiac syndrome X is a clinical entity which most often pertains to women with chest pain, no obstructive epicardial CAD, and ST-depression on stress electrocardiography, although there is no standard definition. Cardiac syndrome X is a heterogeneous disorder with multiple pathophysiologic etiologies for chest pain within the non-cardiac and cardiac non-ischemic and ischemic groups. In contrast, MVA has an identifiable cardiac ischemic mechanism.

Patients with CMD have similar risk factors as those with epicardial CAD. Kaufmann et al. demonstrated that the noxious prooxidant effects of smoking extend beyond the epicardial arteries to the coronary microcirculation [16]. Hypercholesterolemia has been shown to cause CMD in patients with normal coronary arteries [17, 18]. Hypertensive patients can develop CMD and MVA [19, 20]. Several studies have shown that patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) develop CMD, which may be an early marker for atherosclerosis and epicardial CAD in this population [7, 21–23]. Inflammation, such as in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis has been associated with CMD [24].

CMD can be present in patients with and without obstructive epicardial CAD. Patients with CMD and obstructive epicardial CAD can present with angina that is prolonged or poorly responsive to sublingual nitrates. Concurrent CMD and MVA can also be suspected in patients with angina that appears to be more severe than expected by the degree of epicardial coronary stenosis [25]. Angina that persists despite successful revascularization may also be due to CMD. This is important to recognize because failing to do so can result in unnecessary revascularization procedures. The relative contribution of CMD and obstructive epicardial coronary stenosis to angina symptoms cannot currently be accurately discerned, and thus treatments must target both of these pathophysiologic mechanisms with risk factor reduction and anti-anginal treatment.

Diagnosis of MVA

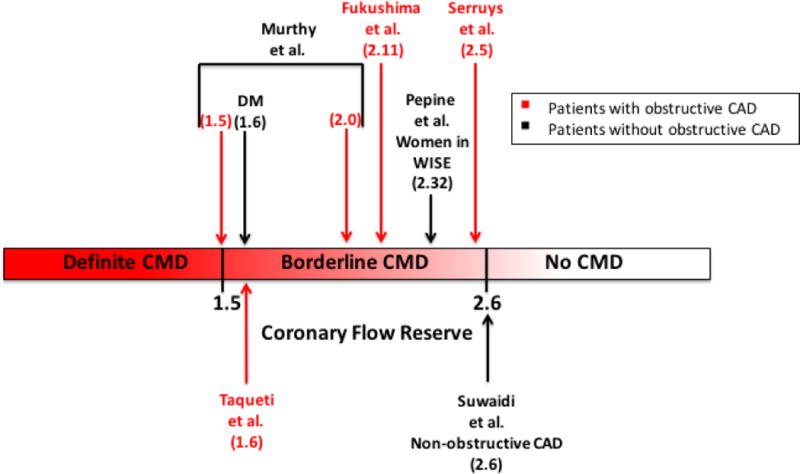

Unlike epicardial coronary arteries, the coronary microcirculation cannot be directly imaged by coronary angiography [8]. Small coronary arteries may be visualized by endomyocardial biopsy, [26] but this is highly invasive and doesn’t allow for functional assessment of the microcirculation. Several measurements relying on the quantification of blood flow through the coronary circulation have been used to describe function of the coronary microvasculature. Coronary flow reserve (CFR) is defined as the magnitude of increase in coronary flow that can be achieved from the resting state to maximal coronary vasodilation [8]. Since resistance of flow through the coronary circulation is primarily determined by the microvasculature, CFR can be used as a surrogate of microvascular function. CFR using invasive testing and MPR using positron-emission tomography (PET) or cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) are the current gold standard for clinically assessing microvascular function. The cut-off to use for CFR to define CMD is currently unclear especially since it has been shown that CFR among healthy individuals can vary according to age and sex [27]. An early study using PET suggested a threshold of 2.5 as the cut-off for “normal [12].” However, several contemporary prognostic studies among patients with and without CAD have found CFR to have prognostic benefit at thresholds of 1.5 to 2.6 (Figure 1) [1–6, 8].

Figure 1.

This figure illustrates the coronary flow reserve (CFR) cutoffs that have been used in studies showing a worse prognosis among patients with coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) with (red font) and without (black font) obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD). A proposed definition of CMD is illustrated that shows ranges of CFR that represent definite CMD, possible CMD, and the absence of CMD.

Several invasive techniques to assess CFR exist, including thermodilution techniques and intracoronary Doppler ultrasonography [11]. Both of these techniques measure flow through one epicardial artery, thus interrogating only one coronary distribution. The development of non-invasive techniques has eliminated the need for invasive flow estimation.

Measurement of myocardial blood flow (MBF) noninvasively by PET [27] and CMR has allowed for noninvasive quantification of microvascular function with high precision [8]. PET perfusion imaging accurately quantifies MBF due to the linear relationship between radioisotope signal intensity and MBF and has become the gold standard of coronary microvascular evaluation [11, 28, 29]. A disadvantage of PET MBF quantification is the short half-lives of the position emitters used, which require production at an onsite cyclotron with radiochemistry facilities or an expensive renewable generator. The risk from radiation should also be considered, although the effective dose received is minimal [27]. Alternatively, CMR can assess myocardial perfusion based on changes in the myocardial signal intensity of gadolinium. Quantitative perfusion reserve assessment is 83% and 77% accurate for the detection of coronary artery stenoses >50% and >70%, respectively [30]. CMR has high spatial resolution, wide scanner availability, and lacks ionizing radiation [11, 31]. However, it is limited by claustrophobia, body size too large for the machine bore, metallic hardware contraindication, and the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis with gadolinium administration in patients with reduced GFR. Several studies have compared CMR to PET for perfusion quantification. CMR MPR values may be lower compared with PET, 2.5 ± 1.0 vs 4.3 ± 1.8 in one study [32]. However, in patients with known or suspected CAD, the diagnostic accuracy of MPR was similar, with an MPR by PET ≤1.44 predicting significant CAD with 82% sensitivity and 87% specificity, and an MPR by CMR ≤1.45 predicting significant CAD with 82% sensitivity and 81% specificity [31].

Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography has also been studied in CMD but is not as robust. This technique measures coronary blood flow velocity, an indirect measurement of coronary blood flow. This technique has only been shown to be reliable when assessing blood flow in the left anterior descending artery [33, 34] in patients with good echocardiographic windows. It is also highly operator dependent. Myocardial contrast echocardiography has also displayed excessive variability [11, 35].

Coronary Flow Reserve (CFR) and Prognosis

Several studies have assessed prognosis in CMD among patients with obstructive epicardial CAD. Among patients with epicardial CAD who underwent PCI, an intracoronary Doppler-derived CFR <2.5 after angioplasty predicted recurrence of angina or ischemia within one month after PCI [3]. Fukushima et al. demonstrated that patients with CAD and a global CFR < 2.11 were at higher risk of a composite of cardiac death, MI, invasive angiography, or hospitalization for heart failure [5]. Murthy et al. demonstrated a 16-fold increased risk of cardiac death in patients with suspected CAD and CFR <1.5 compared to patients with a CFR > 2 [1]. A recently published study assessing patients referred for coronary angiography after stress PET showed an association between CFR and outcomes independent of angiographic disease score [6]. In this study, a CFR < 1.6 predicted benefit from revascularization. Lower CFR was associated with increased morbidity independent of angiographic scores, including admissions for HF.

Similar ranges in CFR have been seen in studies assessing patients without obstructive epicardial CAD. Pepine et al. demonstrated an increase in the composite outcome including death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure in women without obstructive CAD but with a CFR <2.32 [2]. Likewise, Suwaidi et al. demonstrated an increase in cardiac events (MI, percutaneous revascularizations, CABG, and or/cardiac death in patients with non-obstructive CAD and a mean CFR of 2.6 measured by intracoronary Doppler [4]. Diabetic patients without known CAD who have an impaired CFR have a risk of cardiac death comparable to and possibly higher than nondiabetic patients with known CAD [7]. It has been suggested that impaired CFR may be a more powerful biomarker for diffuse atherosclerosis than diabetes mellitus alone [6].

Figure 1 illustrates the multiple studies examining prognosis in CMD. Given that the literature doesn’t clearly define an optimal cut point for the diagnosis of pathologic CMD we propose the following 3-tiered characterization of the likelihood of CMD: <1.5 definite CMD, 1.5–2.6 borderline CMD, and >2.6 no CMD.

Therapies for Microvascular Angina

A recent systematic review by Marinescu et al. assessed the literature on treating MVA and the underlying CMD [11]. Studies were included in the review if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) human subjects; 2) evidence of CMD defined by CFR or MPR <2.5 using PET, CMR, invasive intracoronary Doppler, or invasive intracoronary thermodilution; and 3) angina or an anginal equivalent. Studies that included patients with epicardial CAD with a stenosis ≥ 50%, no evaluation of CAD, or known structural heart disease or heart failure were excluded. CMD therapy in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy has also been studied but was beyond the scope of this review. Strict inclusion criteria were only met in 8 papers evaluating 84 patients, highlighting the limited evidence available to support current treatment strategies for MVA and CMD. Table 1 highlights these findings.

Table 1.

Therapies studied in microvascular angina.

| Treatment | Patients (n) | Treatment Duration | Mode of Assessing CFR or MPR | Findings | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quinapril | 13 | 4 months | IC Doppler | Improvement in angina and CFR | Pauly et al. 2011 [38] |

| Norethindrone/ethinyl estradiol | 18 | 12 weeks | IC Doppler | Improvement in angina | Bairey Merz et al. 2010 [39] |

| L-Arginine infusion | 12 | one time infusion | PET Scan | No improvement in MPR | Bøttcher et al 1999 [37] |

| Sildenafil | 12 | one time administration | IC Doppler | Improvement in CFR | Denardo et al. 2011 [36] |

| TENS | 8 | 4 weeks | PET Scan | Improvement in angina and MPR | Jessurun et al. 2003 [40] |

| Pravastatin | 6 | 6 months | IC Doppler | No improvement in CFR | Houghton et al. 2000 [42] |

| Diltiazem infusion | 5 | one time infusion | Thermodilution | No improvement in CFR | Sutsch et al. 1995 [43] |

| Doxazosin | 10 | 10 weeks | Thermodilution | No improvement in symptoms | Bøtker et al. 1998 [41] |

Table is modified from the systematic review: Marinescu et al. [11]. CFR = coronary flow reserve, MPR = myocardial perfusion reserve, PET = positron emission tomography, TENS = transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

Nitric oxide modulators, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, estrogens, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) were the only drug classes/treatment modalities that met strict inclusion criteria and demonstrated benefits in their respective endpoints. We will briefly review the potential mechanism for each class and the studies that showed benefit. Guanylate cyclase activation by nitric oxide leads to increased cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). Likewise, PDE-5 inhibitors, such as sildenafil, inhibit breakdown of cGMP. The net effect is smooth muscle relaxation. A small study with sildenafil showed improvement in CFR but did not assess symptoms [36]. A study using a one time L-arginine infusion did not show an improvement in MPR [37]. Angiotensin II is a potent coronary vasoconstrictor. It has been proposed that ACE inhibitors may directly modulate coronary microvascular tone [11]. One small placebo-controlled trial involving quinapril showed improvement in angina and CFR [38]. Chest pain in the absence of obstructive epicardial CAD has high prevalence in post-menopausal women. Thus it has been theorized that an estrogen deficiency may play a role on CMD [11]. One small study using norethindrone/ethinyl estradiol showed an improvement in anginal symptoms [39]. Spinal stimulation is thought to modulate pain-related nerve signals and increase myocardial blood flow through effects on sympathetic tone [11]. A small study assessing TENS in MVA showed improvement in myocardial perfusion reserve and angina [40].

The following drug classes met inclusion criteria and but did not show improvements in their respective endpoints: alpha-blockers, statins, and calcium channel blockers. Alpha-blockers are thought to decrease microvascular tone by decreasing sympathetic activity [11], but a small study using doxazosin did not show any improvement in symptoms [41]. Statins have both anti-inflammatory and antiatherosclerotic effects that could theoretically improve CMD, but a small study of pravastatin did not show a statistically significant improvement in CFR and did not assess symptoms [42]. Calcium-channel blockers are potent vasodilators and thus may decrease microvascular tone. Only one small study using intravenous diltiazem met strict inclusion criteria and failed to show an improvement in CFR [43].

Several of the classes of medications most typically used for angina pectoris in known obstructive CAD lack any data in MVA and CMD, including beta-blockers, anti-anginals, and nitrates. Beta-blockers treat ischemia by reducing myocardial oxygen demand and increasing diastolic perfusion time. Although well studied in obstructive epicardial CAD and in CMD in patients with structural heart disease, there is no currently published study that met our inclusion criteria in patients with MVA. Anti-anginals such as ranolazine are commonly used for refractory angina pectoris, but no study met strict inclusion criteria for MVA. Nitrates increase smooth muscle relaxation and cause arterial vasodilation. These are also commonly used in angina pectoris but have not been well studied in MVA [11].

As illustrated by Marinescu et al. there is little evidence to support current treatment strategies for MVA and CMD [11], and yet most clinicians treat MVA with traditional antianginal therapy. There are several limitations to the current studies assessing therapeutics in microvascular angina. First, they have typically had small sample sizes and short-term follow-up periods. Second, there is not a clearly defined definition of CMD based on CFR cut-offs. Finally, no studies have assessed whether improving CMD leads to an improved prognostic benefit, although it’s well known that impaired CFR in itself is a poor prognostic indicator.

Conclusions

This review summarized the current literature on the definition and diagnosis of CMD, the prognosis of patients with CMD with and without concomitant CAD, and the treatment of CMD and MVA. CMD and MVA are highly prevalent and clinicians need to be aware of their clinical implication. Noninvasive techniques such as CMR and PET have emerged that can accurately assess coronary microvascular function. However, a standardized definition for CMD has not yet been established. Patients with CMD with and without epicardial CAD have been shown to have a poor prognosis including an increase in cardiac death, nonfatal MI, and hospitalizations. Diabetics with CMD and without known CAD have been shown to have a similar prognosis to patients with known obstructive epicardial CAD. Ideal treatment for CMD is unknown as there is little evidence to support current therapies for MVA. Future research needs to focus on developing a universal definition for diagnosing CMD using validated techniques, and on assessing effective therapies that improve angina relief and prognosis among patients with CMD.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Dr. Adrián I. Löffler declares that he has no conflict of interest. Dr. Jamieson Bourque receives research grant support from Astellas Pharma.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Adrián I. Löffler, Email: al2ys@hscmail.mcc.virginia.edu.

Jamieson Bourque, Email: jbourque@virginia.edu.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

*Of importance

**Of major importance

- 1.Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, et al. Improved cardiac risk assessment with noninvasive measures of coronary flow reserve. Circulation. 2011;124:2215–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.050427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pepine CJ, Anderson RD, Sharaf BL, et al. Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia: Results from the national heart, lung and blood institute. WISE (women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2825–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serruys PW, di Mario C, Piek J, et al. Prognostic value of intracoronary flow velocity and diameter stenosis in assessing the short- and long-term outcomes of coronary balloon angioplasty: The DEBATE study (doppler endpoints balloon angioplasty trial europe) Circulation. 1997;96:3369–77. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suwaidi JA, Hamasaki S, Higano ST, Nishimura RA, Holmes DR, Lerman A. Long-term follow-up of patients with mild coronary artery disease and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2000;101:948–54. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.9.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukushima K, Javadi MS, Higuchi T, et al. Prediction of short-term cardiovascular events using quantification of global myocardial flow reserve in patients referred for clinical 82Rb PET perfusion imaging. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2011;52:726–32. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.081828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6**.Taqueti VR, Hachamovitch R, Murthy VL, et al. Global coronary flow reserve is associated with adverse cardiovascular events independently of luminal angiographic severity and modifies the effect of early revascularization. Circulation. 2015;131:19–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011939. This paper was recently published and of great importance as it showed that low CFR independent of angiographic score predicts poor outcome. It also showed that those with lowest CFR received greatest benefit from revascularization. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7*.Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, et al. Association between coronary vascular dysfunction and cardiac mortality in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2012;126:1858–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.120402. This paper is of an importance as it illustrated the importance of determining CFR among diabetics. They found that diabetic patients without known CAD who have an impaired CFR have a risk of cardiac death comparable to and possibly higher than nondiabetic patients with known CAD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camici PG, Crea F. Coronary microvascular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:830–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanza GA, Crea F. Primary coronary microvascular dysfunction: Clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and management. Circulation. 2010;121:2317–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.900191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannon RO, Epstein SE. “Microvascular angina” as a cause of chest pain with angiographically normal coronary arteries. American Journal of Cardiology. 1988:1338. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(88)91180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11**.Marinescu MA, Loffler AI, Ouellette M, Smith L, Kramer CM, Bourque JM. Coronary microvascular dysfunction, microvascular angina, and treatment strategies. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:210–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.12.008. This systematic review was recently published and of great importance as it illustrates the lack of data to support current therapy for MVA and that there is no established definition for defining CMD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geltman EM, Henes CG, Senneff MJ, Sobel BE, Bergmann SR. Increased myocardial perfusion at rest and diminished perfusion reserve in patients with angina and angiographically normal coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16:586–95. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90347-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graf S, Khorsand A, Gwechenberger M, et al. Typical chest pain and normal coronary angiogram: Cardiac risk factor analysis versus PET for detection of microvascular disease. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48:175–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reis SE, Holubkov R, Smith AJC, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is highly prevalent in women with chest pain in the absence of coronary artery disease: Results from the NHLBI WISE study. Am Heart J. 2001;141:735–41. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lanza GA, Manzoli A, Bia E, Crea F, Maseri A. Acute effects of nitrates on exercise testing in patients with syndrome X. clinical and pathophysiological implications. Circulation. 1994;90:2695–700. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.6.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufmann PA, Gnecchi-Ruscone T, di Terlizzi M, Schäfers KP, Lüscher TF, Camici PG. Coronary heart disease in smokers: Vitamin C restores coronary microcirculatory function. Circulation. 2000;102:1233–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.11.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dayanikli F, Grambow D, Muzik O, Mosca L, Rubenfire M, Schwaiger M. Early detection of abnormal coronary flow reserve in asymptomatic men at high risk for coronary artery disease using positron emission tomography. Circulation. 1994;90:808–17. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yokoyama I, Ohtake T, Momomura S, Nishikawa J, Sasaki Y, Omata M. Reduced coronary flow reserve in hypercholesterolemic patients without overt coronary stenosis. Circulation. 1996;94:3232–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brush JE, Cannon RO, Schenke WH, et al. Angina due to coronary microvascular disease in hypertensive patients without left ventricular hypertrophy. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1302–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811173192002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treasure CB, Klein JL, Vita JA, et al. Hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy are associated with impaired endothelium-mediated relaxation in human coronary resistance vessels. Circulation. 1993;87:86–93. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nitenberg A, Valensi P, Sachs R, Dali M, Aptecar E, Attali J. Impairment of coronary vascular reserve and ACh-induced coronary vasodilation in diabetic patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries and normal left ventricular systolic function. Diabetes. 1993;42:1017–25. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.7.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokoyama MD I, Momomura MD S, Ohtake MD T, et al. Reduced myocardial flow reserve in Non–Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1472–7. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitkänen O, Nuutila P, Raitakari OT, et al. Coronary flow reserve is reduced in young men with IDDM. Diabetes. 1998;47:248–54. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Recio-Mayoral A, Mason JC, Kaski JC, Rubens MB, Harari OA, Camici PG. Chronic inflammation and coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients without risk factors for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1837–43. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crea F, Lanza GA, Camici PG. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. Milan: Springer; 2014. CMD in obstructive CAD; pp. 152–154. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson PJ, Livesley B, Oram S, Olsen EGJ, Armstrong P. Angina pectoris with normal coronary arteries. Transvenous myocardial biopsy in diagnosis. The Lancet. 1974;304:677–80. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)93260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufmann PA, Camici PG. Myocardial blood flow measurement by PET: Technical aspects and clinical applications. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2005;46:75–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saraste MD, PhD Antti, Kajander, MD Sami, et al. PET: Is myocardial flow quantification a clinical reality? Journal of Nuclear Cardiology. 2012;19:1044–59. doi: 10.1007/s12350-012-9588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danad I, Uusitalo V, Kero T, et al. Quantitative assessment of Myocardial Perfusion in the detection of significant coronary artery disease: Cutoff values and diagnostic accuracy of quantitative [15O]H2O PET imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1464–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel AR, Antkowiak PF, Nandalur KR, et al. Assessment of advanced coronary artery disease: Advantages of quantitative cardiac magnetic resonance perfusion analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:561–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morton G, Chiribiri A, Ishida M, et al. Quantification of absolute myocardial perfusion in patients with coronary artery disease: Comparison between cardiovascular magnetic resonance and positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1546–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pärkkä JP, Niemi P, Saraste A, et al. Comparison of MRI and positron emission tomography for measuring myocardial perfusion reserve in healthy humans. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006;55:772–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hozumi T, Yoshida K, Akasaka T, et al. Noninvasive assessment of coronary flow velocity and coronary flow velocity reserve in the left anterior descending coronary artery by doppler echocardiography: Comparison with invasive technique. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1251–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lethen H, Tries HP, Brechtken J, Kersting S, Lambertz H. Comparison of transthoracic doppler echocardiography to intracoronary doppler guidewire measurements for assessment of coronary flow reserve in the left anterior descending artery for detection of restenosis after coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:412–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogel R, Indermühle A, Reinhardt J, et al. The quantification of absolute myocardial perfusion in humans by contrast echocardiography: Algorithm and validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:754–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denardo SJ, Wen X, Handberg EM, et al. Effect of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition on microvascular coronary dysfunction in women: A women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (WISE) ancillary study. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:483–7. doi: 10.1002/clc.20935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bøttcher M, Bøtker HE, Sonne H, Nielsen TT, Czernin J. Endothelium-dependent and -independent perfusion reserve and the effect of l-arginine on myocardial perfusion in patients with syndrome X. Circulation. 1999;99:1795–801. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.14.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pauly DF, Johnson BD, Anderson RD, et al. In women with symptoms of cardiac ischemia, nonobstructive coronary arteries, and microvascular dysfunction, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition is associated with improved microvascular function: A double-blind randomized study from the national heart, lung and blood institute women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (WISE) Am Heart J. 2011;162:678–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merz CNB, Olson MB, McClure C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of low-dose hormone therapy on myocardial ischemia in postmenopausal women with no obstructive coronary artery disease: Results from the national institutes of health/national heart, lung, and blood institute–sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (WISE) Am Heart J. 2010;(159):987. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jessurun GAJ, Hautvast RWM, Tio RA, DeJongste MJL. Electrical neuromodulation improves myocardial perfusion and ameliorates refractory angina pectoris in patients with syndrome X: Fad or future? European Journal of Pain. 2003;7:507–12. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(03)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bøtker HE, Sonne HS, Schmitz O, Nielsen TT. Effects of doxazosin on exercise-induced angina pectoris, ST-segment depression, and insulin sensitivity in patients with syndrome X. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:1352–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Houghton JL, Pearson TA, Reed RG, et al. Cholesterol lowering with pravastatin improves resistance artery endothelial function*: Report of six subjects with normal coronary arteriograms. Chest. 2000;118:756–60. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sütsch G, Oechslin E, Mayer I, Hess OM. Effect of diltiazem on coronary flow reserve in patients with microvascular angina. Int J Cardiol. 1995;52:135–43. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(95)02458-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]