Abstract

Objective

Stable housing is a fundamental human right, and an important element for both mental health recovery and social inclusion among people with serious mental illness. This article reports findings from a study on the recovery orientation of structured congregate community housing services using the Recovery Self-Assessment Questionnaire (RSA) adapted for housing (O’Connell, Tondora, Croog, Evans, & Davidson, 2005).

Methods

The RSA questionnaires were administered to 118 residents and housing providers from 112 congregate housing units located in Montreal, Canada.

Results

Residents rated their homes as significantly less recovery-oriented than did proprietors, which is contrary to previous studies of clinical services or Assertive Community Treatment where RSA scores for service users were significantly higher than service provider scores. Findings for both groups suggest the need for improvement on 5 of 6 RSA factors. While proprietors favored recovery training and education, and valued resident opinion and experience, vestiges of a traditional medical model governing this housing emerged in other findings, as in agreement between the 2 groups that residents have little choice in case management, or in the belief among proprietors that residents are unable to manage their symptoms.

Conclusions and Implications for Practice

This study demonstrates that the RSA adapted for housing is a useful tool for creating recovery profiles of housing services. The findings provide practical guidance on how to promote a recovery orientation in structured community housing, as well as a novel approach for reaching a common understanding of what this entails among stakeholders.

Keywords: housing, recovery orientation, services, congregate housing

This article reports findings from a study on the recovery orientation of traditional congregate housing in Montreal, Canada. Stable housing is a fundamental right and gateway to social inclusion. For persons with serious mental illness (SMI), housing is an important adjunct to treatment in achieving mental health recovery (Tsai, Bond, & Davis, 2010). Recovery was first described by Anthony (1993) as a unique process of personal change leading to a better life, even within the limitations of mental illness. While recovery has emerged over the past two decades as the guiding paradigm for international mental health policy, systems and services (Adams, Daniels, & Compagni, 2009; Davidson et al., 2007; Le Boutillier et al., 2011) on how to translate the recovery concept into mental health services remains challenging (Pilgrim, 2008; Slade, 2009).

Research on housing for people with SMI increasingly favors independent, supported, housing over traditional congregate models such as foster homes or group homes. While supported housing is considered a fundamental improvement in housing for this population (Nelson, 2010), no single, evidence-based model of housing has emerged to guide research and practice (Rog, 2004; Tabol, Drebing, & Rosenheck, 2010). Studies have revealed substantial differences in staffing, levels of support, and environmental characteristics among different housing types, as well as definitional confusion (Isaac, 2007; Priebe, Saidi, Want, Mangalore, & Knapp, 2009). One meta-analysis suggested the need to examine outcomes in terms of different population subgroups (Leff et al., 2009).

Research on housing preferences consistently shows that people with SMI prefer independent housing with low restrictiveness and supports as needed (Fakhoury, Murray, Shepherd, & Priebe, 2002; Forchuk, Nelson, & Hall, 2006; Piat et al., 2008). Living in one’s preferred home predicts successful outcomes and is associated with perceived choice and control over the environment (Boydell, 2006; Nelson, Sylvestre, Aubry, George, & Trainor, 2007). By contrast, service providers tend to endorse structured settings such as group homes for their clients (Corrigan, Mueser, Bond, Drake, & Solomon, 2008; Piat et al., 2008; Tsai, Bond, Salyers, Godfrey, & Davis, 2010). Residents in congregate housing may also prefer that model for the security it provides, particularly when age and physical health concerns are taken into account (White, 2013; Piat et al., 2008).

Other research has identified key elements in recovery-oriented housing, beginning with the assumption that residents are full citizens with the same needs and aspirations as others (Nelson, 2010). From the consumer perspective, recovery-oriented housing is good quality and affordable (Padgett, Gulcur, & Tsemberis, 2006); allows choice and control (Ashcraft, Anthony, & Martin, 2008; Grant & Westhues, 2010; Hill, Mayes, & McConnell, 2010); and provides peer support (Tsai, Mares, & Rosenheck, 2012). Recovery-oriented homes promote resident participation (Browne & Hemsley, 2010). Staff are knowledgeable about recovery and convinced that recovery is possible (Farkas, Gagne, Anthony, & Chamberlin, 2005).

There are also links between recovery and meaningful relationships, or social networks, which are enhanced when housing is stable and permanent (Chesters, Fletcher, & Jones, 2005). Kloos and Shah (2009) and Kloos and Townley (2011) found that neighborhood relationships, social climate, and perceived safety are significantly related to psychological well-being and are important mediating factors in recovery. Another recovery approach involving direct funding or “personalization” of services helps connect people assertively to their natural communities and break down stigma (Browne, Hemsley, & St. John, 2008; Chamberlin, 2006).

Despite concerns that traditional congregate housing restricts choice and promotes dependency (CAMH Community Support and Research Unit, 2012), congregate housing remains the most prevalent type of housing, and little evaluative research exists on the recovery orientation of this congregate housing from the perspectives of those directly involved. This study addresses this gap by exploring perceptions of residents and housing proprietors on the recovery orientation of traditional congregate housing for persons with SMI.

Methods

Procedure and Participants

The study took place in Montreal, Canada. The study population included individuals diagnosed with serious mental illness living in congregate housing from two university-based psychiatric hospitals in Montreal. This network included 3,206 available places in foster homes and group homes. These group settings offer limited privacy or choice. Services are tied to the housing. Professionals recruit and supervise housing proprietors1 to manage this housing on a contractual and not-for-profit basis. Housing proprietors are primarily nonprofessional caregivers, who provide room and board as well as psychosocial rehabilitation services 24/7, and may live either on or off site. Residents must be referred, and followed, by a hospital multidisciplinary team in order to live in this housing. Placements are long term (over 5 years) for most residents, as movement toward more autonomous housing is not encouraged.

Resident participants had to meet the following criteria: (a) diagnosis of serious mental illness (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression); (b) no primary diagnosis of intellectual handicap; (c) occupancy in congregate housing for at least 6 months; (d) age between 18 and 64 years; (d) English or French speaker; (f) no involvement with the criminal justice system; and (g) deemed well enough to participate in the research by the housing proprietor.

Potential resident participants were randomly selected, then recruited through the housing proprietors, who were contacted and asked to solicit the participation of selected residents living in their homes on behalf of the team. Of 518 individuals approached, 114 (22%) refused to participate, while another 29 (6%) refused after screening; 31 (6%) agreed to participate but were later lost to contact. As resident selection proceeded, investigators identified 30% of potential participants as outside the terms of reference: 118 (23%) had moved into other housing or away from Montreal; 10 (2%) were hospitalized; 5 (1%) deceased; while, for 7 (1%) others, the residence had closed. The final sample included 188 residents from 112 homes. There were 96 housing proprietors in the study, 14 of whom managed more than one home, who were matched to residents and recruited to the study. Interviews were conducted between June 2008 and September 2009.

The Recovery Self-Assessment (RSA) housing questionnaires (RSA-Housing) were administered individually, or in small groups (n = 4–6), and took 45 min on average to complete. Each question asked residents to rate the primary person they came into contact with the proprietor, or other staff person working in the home. A standard sociodemographic questionnaire was also administered, including questions on overall health, mental health, and residential history. The research ethics boards of each participating hospital approved the study. Participation was voluntary, and all participants signed and received a copy of the consent form. Residents received financial compensation for their time.

Measures

The RSA is a self-report instrument designed to assess the recovery orientation of mental health services and includes versions for service providers, service users, family members, and administrators (O’Connell et al., 2005). The RSA comprises 32 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale, and six factors: life goals, consumer involvement, diversity of treatment options, consumer choice, individually-tailored services, and inviting environment. Studies confirm that the RSA has moderate to strong psychometric properties (validity and reliability; McLoughlin, Du Wick, Collazzi, & Puntil, 2013; McLoughlin & Fitzpatrick, 2008; O’Connell et al., 2005; Ye, Pan, Wong, & Bola, 2013). In a hospital-based study, Salyers, Tsai, and Stultz (2007) found that differences on RSA scores held after controlling for sociodemographic factors. A systematic review of recovery measures found that the RSA alone had adequate internal consistency, and among the best-developed conceptual underpinnings (Williams et al., 2012).

The RSA is currently the most widely used instrument for assessing the recovery orientation of mental health services, according to the systematic review by Williams et al. (2012). For example, the RSA provided initial evidence of strong recovery orientation in Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) services (Kidd et al., 2010), while further research by Kidd et al. (2011) found support for an association between recovery oriented services and treatment outcomes across 67 ACT teams in Ontario. Partial hospitalization programs in the United States were also found to be recovery-oriented using the RSA (Yanos, Vreeland, Minsky, Fuller, & Roe, 2009). Burgess, Pirkis, Coombs, and Rosen (2011) identified the RSA as a strong candidate for routine use in the Australian public sector based on an evaluation of 11 recovery measures for mental health services, whereas Ye et al. (2013) translated and validated the RSA for use with Chinese populations.

In the present study, the RSA was adapted for evaluating the recovery orientation of services in congregate housing in Montreal, Canada. The original RSA items were not changed. However, each question began with, “The proprietor and/or caregiver and/or staff …” Study participants were asked to rate either the proprietor, caregiver, or staff. Administrators from two2 university-based psychiatric hospitals validated the questionnaire. It was then back-translated into French (Vallerand, 1989). An analysis of internal consistency on the adapted RSA-Housing indicates acceptable reliability for both resident (Cronbach’s alpha = .92) and proprietor (Cronbach’s alpha = .84) versions.

Data Analysis

Mean scores for residents and proprietors on the 32 RSA-Housing items, means for each of the six factors, and an overall mean score for each group were calculated using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 15. The higher the score, the more positive is the perception of recovery orientation for that item. A further two-step analysis was conducted. First, differences between the means on the six factors and the overall means were calculated for both residents and proprietors, and results for the two groups compared. The second step involved the calculation of mean differences on the 32 RSA-Housing items for residents and for proprietors in relation to their respective global mean scores. Items where differences are significantly inferior to the global means (H0) for either group suggest areas where service provision needs to be prioritized to become more recovery-oriented.

Results

Table 1 presents sociodemographics for residents, two thirds of whom are male (66%). Their average age was 49.5 years. Most were Canadian-born (83%) and single (84%). There were 12 residents on average in each home, with average occupancy 7 years. Most (85%) had a private room, yet 61% indicated a preference to live alone. Most (79%) reported they had not been hospitalized in the year prior to the study, and 66% participated in a rehabilitation program.

Table 1.

Resident Sociodemographic and Housing Characteristics (n = 188)

| Characteristics | n | % | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 123 | 66.1 | |

| Female | 63 | 33.9 | |

| (Missing) | (2) | ||

| Age | 49.5 years | ||

| 44 years or less | 52 | 27.7 | |

| 45–50 | 41 | 21.8 | |

| 51–55 | 40 | 21.3 | |

| 56+ | 55 | 29.3 | |

| Origin | |||

| Canada | 152 | 83.1 | |

| Other | 31 | 16.9 | |

| (Missing) | (5) | ||

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 152 | 84.4 | |

| Married/common-law | 8 | 4.4 | |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 20 | 11.1 | |

| (Missing) | (8) | ||

| Interview language | |||

| English | 36 | 80.9 | |

| French | 152 | 19.1 | |

| Length of stay in residence | 6.8 years | ||

| 30 months or less | 51 | 27.1 | |

| 31–59 | 42 | 22.3 | |

| 60–119 | 48 | 25.5 | |

| 120+ | 47 | 25.0 | |

| Number of residents | 11.8 | ||

| 7 or less | 53 | 28.2 | |

| 8–12 | 75 | 39.9 | |

| 9 or more | 60 | 31.9 | |

| Room | |||

| Individual | 162 | 86.2 | |

| Shared | 26 | 13.8 | |

| Preference | |||

| Live alone | 106 | 60.6 | |

| Live with others | 69 | 39.4 | |

| (Missing) | (13) | ||

| Have a private home | |||

| Yes | 87 | 54.4 | |

| No | 73 | 45.6 | |

| (Missing) | (28) | ||

| Hospitalized in psych hospital during past year | |||

| Yes | 39 | 21.2 | |

| No | 145 | 78.8 | |

| (Missing) | (4) | ||

| Participate in recovery program | |||

| Yes | 63 | 34.4 | |

| No | 120 | 65.6 | |

| (Missing) | (5) | ||

Table 2 presents proprietor characteristics: 70% were male, and 27% completed university. Proprietors had worked 11.4 years on average in the residences they managed. The majority (72%) stated they had received training in recovery, while 60% reported using the term “recovery” in everyday practice.

Table 2.

Proprietor Characteristics (n = 96)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 29 | 30.2 |

| Male | 67 | 69.8 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 30 | 31.3 |

| College (CEGEP) | 40 | 41.7 |

| University | 26 | 27.1 |

| Interview language | ||

| English | 15 | 15.6 |

| French | 81 | 84.4 |

| Number of residents | ||

| 3–8 | 32 | 33.3 |

| 9 | 25 | 26.0 |

| 10+ | 39 | 40.6 |

| Uses the term “recovery” | ||

| Yes | 57 | 60.0 |

| No | 38 | 40.0 |

| (Missing) | (1) | |

| Received training in recovery practices | ||

| Yes | 69 | 71.9 |

| No | 27 | 28.1 |

Analysis of RSA Factors

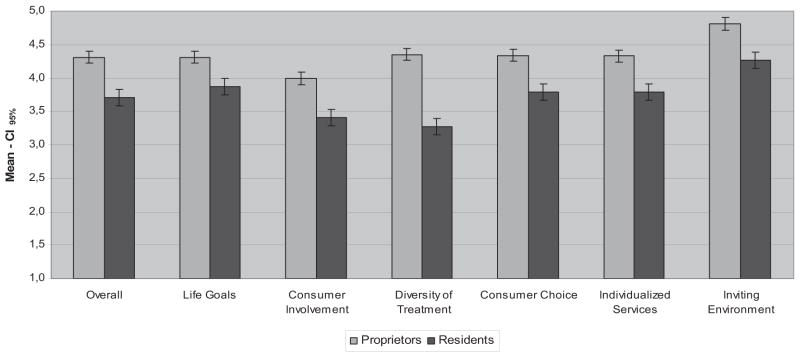

Figure 1 presents the distribution of overall mean scores for residents and proprietors, as well as means on the six factors of the RSA-Housing. The overall mean score is significantly lower for residents, 3.7; 95% CI [3.6, 3.8], than for proprietors, 4.3; 95% CI [4.2, 4.4], with the greatest disparity between the two groups shown on the diversity of treatment options factor, residents: 3.3; 95% CI [3.2, 3.5]; proprietors: 4.4; 95% CI [4.2, 4.4]. The highest scores for both groups occur on the inviting environment factor: that is, 4.3; 95% CI [4.1, 4.4] for residents and 4.8; 95% CI [4.7, 4.9] for proprietors.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Recovery Self-Assessment Questionnaire (RSA) mean global score and of each factor between residents and proprietors.

Analysis of RSA Items

Table 3 presents the mean differences on each item in the RSA-Housing for residents and for proprietors in relation to their respective global mean score, residents: H0 = 3.7; proprietors: H0 = 4.3. Items identified with bold are statistically lower than the mean of each group of respondents, p < .05. As suggested above, negative mean differences with respect to the global mean for residents or proprietors suggest that the recovery orientation on that item could be targeted for improvement, which occurred on 11/32 items (34%) for residents, and on 8/32 items (25%) for proprietors. These results signal that the recovery orientation of housing services could need improvement on 5 of the 6 RSA-Housing factors, that is, in all areas except inviting environment.

Table 3.

Mean Difference Between the Scores on Each RSA-Housing Item and the Mean Global Score for Residents and Proprietors

| Residents (H0 = 3.71)

|

Proprietors (H0 = 4.31)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ | 95% CI | Δ | 95% CI | |||

| Life goals: The proprietor and/or caregiver and/or staff of this residence … | ||||||

| encourage residents to have hope and high expectations for their recovery (RSA #3). | 0.345 | 0.168 | 0.521 | 0.324 | 0.193 | 0.456 |

| believe in the ability of residents to recover (RSA #7). | 0.502 | 0.338 | 0.666 | −0.106 | −0.334 | 0.123 |

| believe that residents have the ability to manage their own symptoms (RSA #8). | 0.328 | 0.150 | 0.506 | −0.930 | −1.181 | −0.679 |

| believe that residents can make their own life choices regarding things such as where to live, when to work, whom to be friends with, and so on (RSA #9). | 0.662 | 0.307 | 1.016 | −0.169 | −0.393 | 0.056 |

| encourage residents to take risks and try new things (RSA #12). | −0.112 | −0.333 | 0.109 | −0.087 | −0.288 | 0.115 |

| help residents develop and plan for life goals beyond managing symptoms or staying stable (e.g., employment, education, physical fitness, connecting with family and friends, and hobbies; RSA #16). | 0.065 | −0.143 | 0.273 | 0.413 | 0.308 | 0.519 |

| routinely assist residents with getting jobs (RSA #17). | −0.471 | −0.731 | −0.212 | −0.367 | −0.645 | −0.089 |

| actively help residents get involved in nonmental health/addiction-related activities such as church groups, adult education, sports, or hobbies (RSA #18). | −0.213 | −0.446 | 0.020 | 0.152 | −0.015 | 0.320 |

| assist residents with fulfilling his/her own goals and aspirations (RSA #28). | 0.296 | 0.099 | 0.493 | 0.445 | 0.338 | 0.552 |

| are knowledgeable about special interest groups and activities in the community (RSA #31). | 0.122 | −0.088 | 0.333 | 0.190 | 0.016 | 0.364 |

| are diverse in terms of culture, ethnicity, lifestyle, and interests (RSA #32). | 0.123 | −0.090 | 0.340 | 0.067 | −0.150 | 0.290 |

| Consumer involvement: The proprietor and/or caregiver and/or staff … | ||||||

| actively help residents find ways to give back to their community (i.e., volunteering, community services, or neighborhood watch/cleanup; RSA #22). | −0.401 | −0.629 | −0.174 | −0.205 | −0.416 | 0.005 |

| encourage residents to help the proprietor and staff with the development of new groups, programs, or services (RSA #23). | −0.273 | −0.505 | −0.041 | −0.361 | −0.638 | −0.085 |

| encourage residents to be involved in the evaluation of services provided in this residence (RSA #24). | 0.177 | −0.021 | 0.375 | 0.201 | 0.018 | 0.384 |

| encourage residents to attend staff and/or management meetings of this residence (RSA #25). | −0.281 | −0.529 | −0.032 | −0.324 | −0.643 | −0.004 |

| involve residents with facilitating staff trainings and education programs in this residence (RSA #29). | −0.791 | −1.050 | −0.531 | −1.375 | −1.783 | −0.966 |

| Diversity of treatment options: The proprietor and/or caregiver and/or staff … | ||||||

| offer residents opportunities to discuss their spiritual needs and interests when they wish (RSA #14). | −0.075 | −0.285 | 0.134 | 0.314 | 0.142 | 0.485 |

| offer residents opportunities to discuss their sexual needs and interests when they wish (RSA #15). | −0.710 | −0.954 | −0.466 | 0.179 | −0.026 | 0.384 |

| actively introduce residents to persons in recovery who can serve as role models or mentors (RSA #20). | −0.586 | −0.821 | −0.352 | −0.779 | −1.105 | −0.453 |

| actively connect residents with self-help, peer support, or consumer advocacy groups and programs (RSA #21). | −0.321 | −0.545 | −0.098 | 0.103 | −0.076 | 0.282 |

| talk with residents about what it takes to move on to another type of housing (RSA #26). | −0.584 | −0.833 | −0.335 | 0.250 | 0.052 | 0.447 |

| Consumer choice: Residents can … | ||||||

| change their clinician or case manager if they wish (RSA #4). | −0.698 | −0.941 | −0.455 | −0.833 | −1.132 | −0.533 |

| easily access their treatment records if they wish (RSA #5). | −0.246 | −0.484 | −0.007 | −0.071 | −0.280 | 0.137 |

| Consumer Choice: The proprietor and/or caregiver and/or staff … | ||||||

| do not use threats, bribes, or other forms of pressure to influence the behavior of residents (RSA #6). | 0.671 | 0.499 | 0.844 | 0.479 | 0.331 | 0.628 |

| listen to and respect the decisions that residents make about their treatment and care (RSA #10). | 0.537 | 0.363 | 0.712 | 0.116 | −0.066 | 0.297 |

| help residents keep track of the progress made toward each individual’s personal goals (RSA #27). | 0.047 | −0.168 | 0.262 | 0.353 | 0.225 | 0.481 |

| Individually-tailored services: The proprietor and/or caregiver and/or staff … | ||||||

| regularly ask residents about their interests and the things they would like to do in the community (RSA #11). | −0.028 | −0.25 | 0.19 | 0.339 | 0.220 | 0.458 |

| offer specific services that fit each resident’s unique culture and life experiences (RSA #13). | 0.063 | −0.129 | 0.256 | 0.217 | 0.046 | 0.388 |

| work hard to help residents include people who are important to them in their recovery/treatment planning (such as family friends, clergy, or an employer; RSA #19). | −0.001 | −0.216 | 0.213 | 0.281 | 0.135 | 0.428 |

| regularly attend trainings on cultural competency (RSA #30). | 0.290 | 0.099 | 0.481 | −0.950 | −1.312 | −0.588 |

| Inviting environment: The proprietor and/or caregiver and/or staff … | ||||||

| make a concerted effort to welcome people in the residence and help them feel comfortable in this residence (RSA #1). | 0.551 | 0.385 | 0.717 | 0.574 | 0.502 | 0.646 |

| This residence offers an inviting and dignified physical environment (e.g., living rooms, bedroom, etc.; RSA #2). | 0.551 | 0.385 | 0.717 | 0.427 | 0.300 | 0.554 |

Note. Items identified with bold are statistically lower than the mean of each group of respondents, p < .05. RSA = Recovery Self-Assessment Questionnaire.

More specifically, scores on the consumer involvement factor reveal the most substantial agreement between residents and proprietors on the need for greater recovery orientation. Residents evaluated 4 of the 5 items on this factor significantly below their overall mean, as compared with 3 out of 5 items for proprietors. The greatest disparity on any single item and global mean scores within this factor emerged on the issue of involving residents in staff training and education programs within the residence (RSA #29). Mean scores were −.79 for residents, and −1.40 for proprietors, yet suggesting that residents need to be much more involved in staff training/education from the perspectives of both groups. Proprietor scores on the individually-tailored services factor seem to reflect concerns related to their own lack of training on cultural competency (RSA #30). On the diversity of treatment options factor, residents rated 4 of 5 items below the mean, allowing us to hypothesize that proprietors do not offer sufficient opportunity to discuss residents’ sexual issues (RSA #15), alternative housing options (RSA #26), or possible connections with self-help, advocacy, and peer support (RSA #21). There was agreement between residents and proprietors on the need to introduce residents to peer mentors (RSA #20). On the consumer choice factor, both groups agreed that residents cannot easily change their clinicians or case managers, nor easily access their treatment plans or records. They also suggest, under life goals, that proprietors do not routinely assist residents to find employment (RSA #17). Proprietors expressed doubt that residents have the ability to manage their symptoms (RSA #8).

Discussion and Conclusions

This is the first known study to evaluate the recovery orientation of congregate housing services using the adapted RSA-Housing. Overall, the results show that residents rated the recovery orientation of their homes lower than proprietors (see Figure 1), which contrasts with results for previous studies on ACT and clinical services where provider ratings were lower than those of service users (Kidd et al., 2010; O’Connell et al., 2005). While residents in this study perceived the recovery orientation of their housing less favorably as compared with proprietors, we should acknowledge the validity of the person’s lived experience.

Regarding specific elements on the RSA, both residents and proprietors identify the need for improvement on core elements of recovery. Interestingly, proprietors felt even more strongly than residents that the later are not sufficiently involved in staff training and education, which implies that providers do value resident opinion and experience. The perception of proprietors that they lack training in cultural competency further implies openness to training on their part. Results for residents suggest a lack of support for them to explore housing alternatives or employment, and few opportunities to connect with self-help and peer support resources. Their sexual needs remain unaddressed. The dominance of a traditional medical model governing this housing were also apparent in agreement between the two groups that residents have little choice over case managers or treatment planning, and in the belief among proprietors that residents are unable to manage their symptoms.

This study suggests that the RSA-Housing can be a useful tool in creating recovery profiles of housing services for people with SMI. While proprietor attitudes are key in influencing the course of recovery and in delivering recovery-oriented services (Tsai & Salyers, 2010), the specific method used here to present and compare resident findings provide a source of guidance to proprietors on areas that should be prioritized for improvement. As well, findings suggest that previous training on recovery has likely had a positive effect on proprietors, as they value this aspect. Furthermore, our original strategy of analyzing RSA data opens a novel approach for an important conversation around recovery among different stakeholders.

Findings from this study confirm that congregate housing does not always provide opportunities for recovery. Although most are in agreement that choice is central to recovery, very little choice is offered in congregate housing. The challenge we face is how to transform traditional congregate housing into permanent affordable supportive housing that promotes recovery, such as Housing First. It is only then that congregate housing residents will become tenants and full citizens.

There are several limitations to this study. While the sample is representative for residents and proprietors of congregate housing in Montreal, results are not generalizable to other cities or districts. Furthermore, it is important to note that the mean RSA scores as used here do not provide an absolute measure of recovery orientation but simple benchmarks to compare several dimensions of recovery for residents and proprietors. Another problem, as with any survey or interview, is social desirability. Study participants may have felt pressured to present their homes in the best light by endorsing a recovery orientation that may not be present. Housing proprietors may have also encouraged those residents with particular viewpoints to participate, thus selection bias may also be a limitation. Finally, self-report surveys may lack the methodological rigor that an independent assessment of recovery practices in the homes would provide.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Grant #8110.

Footnotes

Housing proprietors sign a contract with the hospital. They may hire additional staff to help them.

At the time the study was conducted, three hospitals administered housing for this population: two university-affiliated psychiatric hospitals and one acute care hospital with a psychiatric department At the time of writing this article, the administrative responsibilities for housing was merged into two university-based psychiatric hospitals.

Contributor Information

Myra Piat, Department of Psychiatry, Douglas Mental Health University Institute, McGill University.

Richard Boyer, Department of Psychiatry, Mental Health University Institute of Montreal, University of Montreal.

Marie-Josée Fleury, Department of Psychiatry, Douglas Mental Health University Institute, McGill University.

Alain Lesage, Department of Psychiatry, Mental Health University Institute of Montreal, University of Montreal.

Maria O’Connell, Department of Psychiatry, Center for Community Health and Recovery, Yale University.

Judith Sabetti, Department of Psychiatry, Douglas Mental Health University Institute, McGill University.

References

- Adams N, Daniels A, Compagni A. International pathways to mental health transformation. International Journal of Mental Health. 2009;38:30–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.2753/IMH0020-7411380103. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993;16:11–23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0095655. [Google Scholar]

- Ashcraft L, Anthony WA, Martin C. Home is where recovery begins. Behavioral Healthcare. 2008;28:13–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boydell K. More than a building: Supporting housing for older persons living with mental illness. Toronto: Boydell Consulting Group; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Browne G, Hemsley M. Consumer participation in housing: Reflecting on consumer preferences. Australasian Psychiatry. 2010;18:579–583. doi: 10.3109/10398562.2010.499432. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10398562.2010.499432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne G, Hemsley M, St John W. Consumer perspectives on recovery: A focus on housing following discharge from hospital. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2008;17:402–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00575.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess P, Pirkis J, Coombs T, Rosen A. Assessing the value of existing recovery measures for routine use in Australian mental health services. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;45:267–280. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.549996. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2010.549996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMH Community Support and Research Unit. From this point forward: Ending custodial housing for people with mental illness in Canada. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin J. On our own, together: Peer programs for people with mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:981–982. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.nmd.0000249010.10285.dd. [Google Scholar]

- Chesters J, Fletcher M, Jones R. Mental illness recovery and place. AeJAMH (Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health) 2005:4. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, Solomon P. Principles and practice of psychiatric rehabilitation: An empirical approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Tondora J, O’Connell MJ, Kirk T, Jr, Rockholz P, Evans AC. Creating a recovery-oriented system of behavioral health care: Moving from concept to reality. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2007;31:23–31. doi: 10.2975/31.1.2007.23.31. http://dx.doi.org/10.2975/31.1.2007.23.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhoury WK, Murray A, Shepherd G, Priebe S. Research in supported housing. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2002;37:301–315. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0549-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00127-002-0549-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas M, Gagne C, Anthony W, Chamberlin J. Implementing recovery oriented evidence based programs: Identifying the critical dimensions. Community Mental Health Journal. 2005;41:141–158. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-2649-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10597-005-2649-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forchuk C, Nelson G, Hall GB. “It’s important to be proud of the place you live in”: Housing problems and preferences of psychiatric survivors. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2006;42:42–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2006.00054.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6163.2006.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JG, Westhues A. Choice and outcome in mental health supported housing. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2010;33:232–235. doi: 10.2975/33.3.2010.232.235. http://dx.doi.org/10.2975/33.3.2010.232.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A, Mayes R, McConnell D. Transition to independent accommodation for adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2010;33:228–231. doi: 10.2975/33.3.2010.228.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac M. Provision for the long-term discharged patient. Psychiatry. 2007;6:317–320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mppsy.2007.05.006. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd SA, George L, O’Connell M, Sylvestre J, Kirkpatrick H, Browne G, Thabane L. Fidelity and recovery-orientation in assertive community treatment. Community Mental Health Journal. 2010;46:342–350. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9275-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd SA, George L, O’Connell M, Sylvestre J, Kirkpatrick H, Browne G, … Davidson L. Recovery-oriented service provision and clinical outcomes in assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2011;34:194–201. doi: 10.2975/34.3.2011.194.201. http://dx.doi.org/10.2975/34.3.2011.194.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloos B, Shah S. A social ecological approach to investigating relationships between housing and adaptive functioning for persons with serious mental illness. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;44:316–326. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9277-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10464-009-9277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloos B, Townley G. Investigating the relationship between neighborhood experiences and psychiatric distress for individuals with serious mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:105–116. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0307-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0307-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Boutillier C, Leamy M, Bird VJ, Davidson L, Williams J, Slade M. What does recovery mean in practice? A qualitative analysis of international recovery-oriented practice guidance. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62:1470–1476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.001312011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.001312011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff HS, Chow CM, Pepin R, Conley J, Allen IE, Seaman CA. Does one size fit all? What we can and can’t learn from a meta-analysis of housing models for persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:473–482. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.473. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.60.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin KA, Du Wick A, Collazzi CM, Puntil C. Recovery-oriented practices of psychiatric-mental health nursing staff in an acute hospital setting. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2013;19:152–159. doi: 10.1177/1078390313490025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1078390313490025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin KA, Fitzpatrick JJ. Self-reports of recovery-oriented practices of mental health nurses in state mental health institutes: Development of a measure. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2008;29:1051–1065. doi: 10.1080/01612840802319738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson G. Housing for people with serious mental illness: Approaches, evidence, and transformative change. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare. 2010;37:123–146. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson G, Sylvestre J, Aubry T, George L, Trainor J. Housing choice and control, housing quality, and control over professional support as contributors to the subjective quality of life and community adaptation of people with severe mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2007;34:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0083-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10488-006-0083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell M, Tondora J, Croog G, Evans A, Davidson L. From rhetoric to routine: Assessing perceptions of recovery-oriented practices in a state mental health and addiction system. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2005;28:378–386. doi: 10.2975/28.2005.378.386. http://dx.doi.org/10.2975/28.2005.378.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK, Gulcur L, Tsemberis S. Housing first services for people who are homeless with co-occurring serious mental illness and substance abuse. Research on Social Work Practice. 2006;16:74–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049731505282593. [Google Scholar]

- Piat M, Boyer R, Lesage A, Dorvil H, Couture A, Bloom D. Housing for persons with serious mental illness: Consumer and service provider preferences. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(9):1011–1017. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.9.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piat M, Lesage A, Boyer R, Dorvil H, Couture A, Grenier G, Bloom D. Housing for persons with serious mental illness: Consumer and service provider preferences. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:1011–1017. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.9.1069. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.59.9.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piat M, Ricard N, Sabetti J, Beauvais L. Building life around foster home versus moving on: The competing needs of people living in foster homes. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2008;32:32–39. doi: 10.2975/32.1.2008.32.39. http://dx.doi.org/10.2975/32.1.2008.32.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim D. ‘Recovery’ and current mental health policy. Chronic Illness. 2008;4:295–304. doi: 10.1177/1742395308097863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S, Saidi M, Want A, Mangalore R, Knapp M. Housing services for people with mental disorders in England: Patient characteristics, care provision and costs. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44:805–814. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0001-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rog DJ. The evidence on supported housing. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2004;27:334–344. doi: 10.2975/27.2004.334.344. http://dx.doi.org/10.2975/27.2004.334.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyers MP, Tsai J, Stultz TA. Measuring recovery orientation in a hospital setting. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2007;31:131–137. doi: 10.2975/31.2.2007.131.137. http://dx.doi.org/10.2975/31.2.2007.131.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M. The contribution of mental health services to recovery. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England) 2009;18:367–371. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2018.1437609. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/09638230903191256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabol C, Drebing C, Rosenheck R. Studies of “supported” and “supportive” housing: A comprehensive review of model descriptions and measurement. Evaluation Program Planning. 2010;33:446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Bond GR, Davis KE. Housing preferences among adults with dual diagnoses in different stages of treatment and housing types. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2010;13:258–275. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2010.523357. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15487768.2010.523357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Bond GR, Salyers MP, Godfrey JL, Davis KE. Housing preferences and choices among adults with mental illness and substance use disorders: A qualitative study. Community Mental Health Journal. 2010;46:381–388. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9268-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9268-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Mares AS, Rosenheck RA. Housing satisfaction among chronically homeless adults: Identification of its major domains, changes over time, and relation to subjective well-being and functional outcomes. Community Mental Health Journal. 2012;48:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Salyers MP. Recovery orientation in hospital and community settings. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2010;37:385–399. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9158-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11414-008-9158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand RJ. Vers une méthodologie de validation transculturelle de questionnaires psychologiques: Implications pour la recherche en langue française. Psychologie canadienne. 1989;30:662–689. [Google Scholar]

- White C. Doctoral dissertation. Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Queens University; 2013. Recovery as a guide for environmental enhancement in group homes for people with a mental illness: A social-ecological approach. [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Leamy M, Bird V, Harding C, Larsen J, Le Boutillier C, … Slade M. Measures of the recovery orientation of mental health services: Systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2012;47:1827–1835. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0484-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0484-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanos PT, Vreeland B, Minsky S, Fuller RB, Roe D. Partial hospitalization. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 2009;47:41–47. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20090201-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20090201-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S, Pan JY, Wong DFK, Bola JR. Cross-validation of mental health recovery measures in a Hong Kong Chinese sample. Research on Social Work Practice. 2013;23:311–325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049731512471861. [Google Scholar]