Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have to be expanded in vitro for clinical use, which often leads to highly variable clinical benefit and experimental results. Multicolor fluorescence labeling and deep sequencing were used to demonstrate the dynamic clonal composition of MSC cultures, which might ultimately explain the variable clinical performance of the cells.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stem cells, Umbilical cord, Clonal evolution, DNA barcoding, Reproducibility of results, Stem cell niche

Abstract

Mesenchymal stem (or stromal) cells (MSCs) have been used in more than 400 clinical trials for the treatment of various diseases. The clinical benefit and reproducibility of results, however, remain extremely variable. During the in vitro expansion phase, which is necessary to achieve clinically relevant cell numbers, MSCs show signs of aging accompanied by different contributions of single clones to the mass culture. Here we used multicolor lentiviral barcode labeling to follow the clonal dynamics during in vitro MSC expansion from whole umbilical cord pieces (UCPs). The clonal composition was analyzed by a combination of flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy, and deep sequencing. Starting with highly complex cell populations, we observed a massive reduction in diversity, transiently dominating populations, and a selection of single clones over time. Importantly, the first wave of clonal constriction already occurred in the early passages during MSC expansion. Consecutive MSC cultures from the same UCP implied the existence of more primitive, MSC culture-initiating cells. Our results show that microscopically homogenous MSC mass cultures consist of many subpopulations, which undergo clonal selection and have different capabilities. Among other factors, the clonal composition of the graft might have an impact on the functional properties of MSCs in experimental and clinical settings.

Significance

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can easily be obtained from various adult or embryonal tissues and are frequently used in clinical trials. For their clinical application, MSCs have to be expanded in vitro. This unavoidable step influences the features of MSCs, so that clinical benefit and experimental results are often highly variable. Despite a homogenous appearance under the microscope, MSC cultures undergo massive clonal selection over time. Multicolor fluorescence labeling and deep sequencing were used to demonstrate the dynamic clonal composition of MSC cultures, which might ultimately explain the variable clinical performance of the cells.

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem (also referred to as stromal) cells (MSCs) were first described by Friedenstein et al. as precursor cells in the bone marrow [1]. Today, they can be isolated from various adult or neonatal tissues and are frequently used in clinical trials for the treatment of a plethora of diseases [2, 3]. For regenerative medicine, they are used not only for their ability to differentiate into specific cell types, but also, and more importantly, for their interaction with other cells because of paracrine effects [4, 5]. Their crosstalk with the immune system makes MSCs ideal candidates to be used in the treatment of autoimmune disorders or graft-versus-host disease or as vehicles in antitumor therapy [6, 7]. Despite their frequent use in more than 400 clinical trials [8], the identity of MSC culture-initiating cells (MSC-I) and a possible clonal diversity of the graft with regard to the cell source and in vitro expansion procedure are poorly understood. The International Society for Cellular Therapy proposed minimal criteria defining multipotent MSCs. They have to be plastic-adherent; express surface proteins CD73, CD90, and CD105; and lack the expression of hematopoietic markers [9]. Additionally, they must be able to differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes, and chondrocytes in vitro. Interestingly, several groups suggested that MSC cultures possess further differentiation capabilities beyond the mesodermal lineage and show features of endodermal (hepatogenic) and ectodermal (neurogenic) cell types under the appropriate culture conditions [10–12]. On the one hand, these observations show the plasticity of cells broadly addressed as MSCs; on the other hand, they highlight the need for a better characterization of this cell type, especially for efficient clinical application. Therapeutic benefit after MSC transplantation is highly variable and depends on the donor, disease type, and isolation procedures [13]. The generation of MSC cultures is usually accompanied by the enzymatic destruction of the tissue source. Alternatively, they can be generated by explant culture from umbilical cord tissue [14]. These umbilical cord pieces (UCPs) continuously initiate uniform MSC explant monolayers (MSC-EMs) over a period of months [15]. If cultured separately, MSC-EMs start to show signs of aging within a period of weeks. Because the stem cell niche in the UCPs remains intact, once transferred to another well, they keep initiating new MSC-EMs over several months. We used a marking technique based on combining fluorescent marker proteins, named RGB marking [16], together with genetic barcoding to individually label cells within UCPs and follow their clonal dynamics over time. These integrating lentiviral vectors encode for the fluorescent transgenes mCherry (red), Venus (green), and Cerulean (blue) and can be visualized by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry [17]. The vectors also contain a genetic barcode with 16 random nucleotides (16N) and 15 vector backbone-specific nucleotides, traceable by deep sequencing (Fig. 1) [18]. We transduced more than 20 UCPs of equal size and analyzed the clonal composition of initiated MSC-EMs by flow cytometry, copy number analysis, and high-throughput sequencing. This enabled us to follow single cell clones and show that MSC cultures undergo massive clonal selection during the expansion phase, which is necessary to produce clinically relevant cell numbers. Additionally, we observed transiently participating clones dominating the bulk culture in early passages, followed by a selection of single clones after prolonged culture. The process of clonal constriction both provides a potential explanation for the variable outcome of MSC studies and highlights the need for better characterization of MSCs for their use in cell therapies.

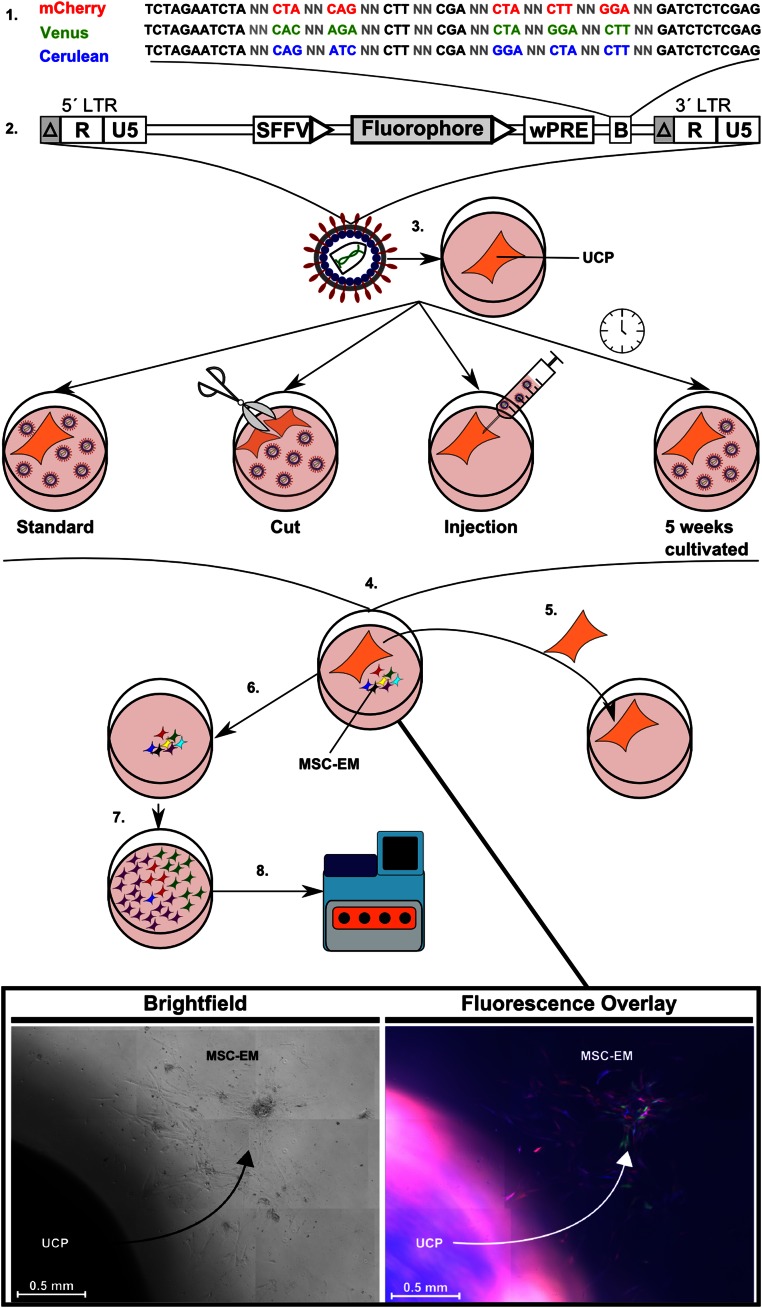

Figure 1.

Lentiviral RGB barcode vector and experimental procedure. (1–3): RGB barcode design with constant and variable (N) nucleotides (1) as part of a (2) lentiviral vector construct (2) driven by an SFFV promoter/enhancer used for the transduction of UCPs (3). (4): Outgrowth of primary MSC-EMs with exemplary microscopic pictures. (5, 6): Transfer of UCP to a new well for initiation of consecutive MSC-EM (5) or independent cultivation of MSC-EM resulting in clonal selection over time (6). (7): MSC-EM after several passages. (8): Next-generation sequencing to assess barcode complexity within DNA samples. Abbreviations: Δ, self-inactivating U3 region; B, barcode; LTR, long terminal repeat; MSC-EM, mesenchymal stem cell explant monolayer; R, repeat region; SFFV, spleen focus forming virus; U, unique region; UCP, umbilical cord piece; wPRE, woodchuck hepatitis virus postregulatory element.

Materials and Methods

UCP and MSC-EM Culture

Human UCPs were obtained from term deliveries (38–40 weeks) after obtaining written informed consent, as approved by the Hannover Medical School ethics committee. UCPs were cultivated in 24-well plates (Sarstedt AG, Nuembrecht, Germany, https://www.sarstedt.com) and MSC-EMs in 12-well plates (Sarstedt AG). The UCPs and MSC-EMs were cultivated in standard medium as previously described and passaged twice a week [15].

H&E Staining and Ki-67 Immunohistochemistry

For hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and for Ki-67 immunohistochemistry 3-µm-thick dewaxed paraffin sections were used [19]. The H&E stain was performed by using Mayer’s hematoxylin, eosin yellow, and phloxin B (all Merck, Darmstadt, Germany, http://www.emdgroup.com). For the immunohistochemical detection of proliferating cells, heat-induced epitope retrieval at pH 6 was applied for permeabilization. Afterward, the slides were incubated with normal goat serum (S-1000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, http://vectorlabs.com) for 20 minutes. The slides were then incubated with the primary antibody (Ki-67 1:200, clone SP6; KI681C01, DCS, Hamburg, Germany, http://www.dcs-diagnostics.de) for 20 hours at 4°C. After washing in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.6), the slides were incubated with the secondary antibody (goat-anti-rabbit-biotin-SP 1:3,000; 111-065-144, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, https://www.jacksonimmuno.com) for 30 minutes, and, likewise, after washing in TBS, with streptavidin-biotin-alkaline phosphatase complex (SA-5100, Vector Laboratories). Fast Red (HK182-5KE, BioGenex, Freemont, CA, http://biogenex.com) was applied as chromogen for 15 minutes. Finally, the slides were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (EGH3411, Linaris Biologische Produkte GmbH, Wertheim-Bettingen, Germany, http://www.linaris.de).

Virus Production and Transduction

Viral supernatants were produced in a four-plasmid split packaging system as described before [18, 20]. We pseudotyped the LeGO-vectors (LeGO-V2-BC16, LeGO-Cer2-BC16, and LeGO-C2-BC16) with 1.5 µg of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G and stored the supernatants at −80°C [21]. Virus supernatants were titrated on SC1 cells without centrifugation as previously described [22]. Before transduction, fresh UCPs (1 cm) were cultivated for 24 hours to remove glycol precipitates in the medium, which might block the access of virus particles to the pieces. The transduction medium contained additional 4 µg/ml protamine sulfate and 0.5 × 107 virus particles per milliliter of each vector construct. UCPs (groups: standard, 5 weeks cultivated, digested and cut in half) were transduced in a final volume of 500 µl of transduction medium. For the digested method, the UCPs were additionally incubated in 1 mg/ml Collagenase IV (Gibco, Darmstadt, Germany, https://www.thermofisher.com) and 1 mg/ml Dispase (Roche Pharma AG, Reinach, Switzerland, http://www.roche-pharma.ch) for 1 hour at 37°C and afterward washed intensely in 50 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before transduction. For the injection group, 10 µl of viral supernatant were injected five to eight times in UCPs. For all groups, medium was changed after 16 hours to standard cultivation medium.

Fluorescence Microscopy and Flow Cytometry

Fluorescence microcopy pictures were taken with an Axio Observer Z1 with the filter set 47 (Cerulean), filter set 46 (Venus), and AHF F36-508 (mCherry) (Zeiss, Stuttgart, Germany, http://www.zeiss.com) and the AxioVision software. For flow cytometry analysis, cells were detached with 400 µl of trypsin/EDTA (GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany, http://www.gelifesciences.com) for 4 minutes at 37°C. Cells were centrifuged at 300g for 5 minutes and resuspended in 300 µl of buffer (PBS, 2% fetal calf serum, and 1 mM EDTA). To determine the expression of transgenes, MSC-EMs were analyzed with a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany, http://www.bdbiosciences.com) and the FlowJo 7.6.5 software (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR, http://www.flowjo.com). For Cerulean 404-nm laser and 450/50 filter, for Venus the 488-nm laser and the filters 525/50 and 505LP, and for mCherry the laser 523-nm and filters 610/20 and 600LP were used.

Tube Formation Assay

The tube formation assay was performed as described previously [23]. After initiation of the MSC-EMs, cells were expanded and transferred to a six-well size, before being sorted by fluorescence using a FACSAria Fusion (BD Biosciences) device. The different populations were cultivated for 1 week in EGM-2 (Lonza). For the tube formation, 1.75 × 104 cells were seeded in triplicates in a 48-well plate precoated with 110 µl of Matrigel (Corning GmbH Life Sciences, Kaiserslautern, Germany, https://www.corning.com). After 4 hours, tube formation was examined by microscopy.

Analysis of Vector Copy Number and Sequencing Preparation

The DNA from MSC-EMs was isolated with QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, http://www.qiagen.com) and DNA from UCPs with genomic DNA from a Tissue Kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL, Dueren, Germany, http://www.mn-net.com) and eluted in 30 µl of water. Vector copy number was measured in a multiplex quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of viral woodchuck hepatitis virus postregulatory element relative to the genomic PTBP2 [24]. For ion torrent sequencing, barcodes were amplified with a nested PCR and a ready-to-use PCR mix MyFi Mix 2× (Bioline, Luckenwalde, Germany, http://www.bioline.com). First PCR using primers pRGB_outer_left and pRGB_outer_right resulted in a 366-bp fragment. A total of 1 µl from a 1:500 dilution served as the template for the nested PCR (primers: pRGB_common; index-primers, ITRGB_XXX). All primers are listed in supplemental online Table 1. Eight samples were pooled and separated on an analytical agarose gel before specific 227-bp fragments were isolated and purified with the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). We used 5 µl of the pooled samples for the final sequencing library in ion torrent deep sequencing (ITS).

Data Processing and Statistics

The preprocessing of the sequencing data was performed with customized Padre 0.94 (http://perlide.org) and Perl 5 (https://www.perl.org) scripts. Sequences were screened for the index-primer sequence to distinguish between biological samples. In a second step, the sequences were screened for the constant nucleotides of the barcodes or for the barcode flanking sequences TACCATCTAGA and CTCGAGACT with a length between 42 and 52 bp to remove unspecific amplicons and to allow for certain rates of sequencing errors. In the third step, identical sequences were clustered. The last step of preprocessing was performed by RStudio 0.98 (RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA, https://www.rstudio.com) and R 3.1.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.r-project.org). All sequences with less than 5 bp difference were summarized to the sequence with the highest read count with the R package igraph to reduce sequencing errors. The Lincoln-Petersen based pool-size calculations were performed by RStudio 0.98 and R 3.1.1. The Shannon-Index was calculated with the R package vegan and the area plots with the package ggplot2. All other diagrams were produced with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, http://www.graphpad.com). Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn´s Multiple Comparison test for statistical significances and linear fit were performed with GraphPad Prism 5. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when p was < .05.

Results

Lentiviral RGB Marking and Barcode Transfer to Umbilical Cord Tissue

Cultured UCPs contain a population of cells that mediates repetitive outgrowth of MSC cultures over a period of at least 6 months. Once initiated, the monolayer cultures grow for several passages before showing signs of senescence, whereas the UCPs are still able to induce the next MSC culture. To understand the clonal development of individually cultured MSC-EMs, we used integrating lentiviral constructs containing the fluorescent RGB-marker genes mCherry (red), Venus (green), or Cerulean (blue). Transduction with all three RGB vectors enabled us to track at least eight different color combinations in flow cytometry, leading to a first assessment of clonal dynamics [16]. Additionally, the RGB vectors coded for a genetic barcode, which included 16 random and 15 backbone-specific nucleotides [18]. We quantified the barcodes via ion torrent deep sequencing, which facilitated the analysis of global MSC culture development and the tracking of individual clones. The relative frequency of individual barcodes, represented by their sequencing reads in ITS, was used as a surrogate marker for the abundance of individual clones. From the deep sequencing experiments, we determined each of our vector libraries to contain at least 1.3 × 105 individual barcodes (detailed information is in supplemental online Fig. 1). To exploit the full potential of RGB-barcode marking, it was necessary to achieve efficient gene transfer to UCP. From previous experiments with primary human MSC monolayers, we identified lentiviral vectors to efficiently transduce our target cells (data not shown). Because of the limited penetration capability of viral particles into solid tissue, we had to investigate the most suitable transduction method for efficient gene transfer. Transduction efficiency was assessed by flow cytometric quantification of transgene-positive MSC-EMs, positive for key surface markers CD73, CD90, and CD105 (supplemental online Fig. 2), growing out from labeled UCPs of similar size. Despite an overall low correlation between the increasing amount of viral particles and the number of genetically labeled MSC-EMs, we achieved reasonable transduction efficiencies above a certain threshold concentration of viral supernatant in the culture medium (supplemental online Fig. 3). Microscopic evaluation of UCP confirmed that, predominantly but not exclusively, cells at the surface of the tissue pieces were transduced by the vector.

Localization of Proliferating Cells Within UCPs

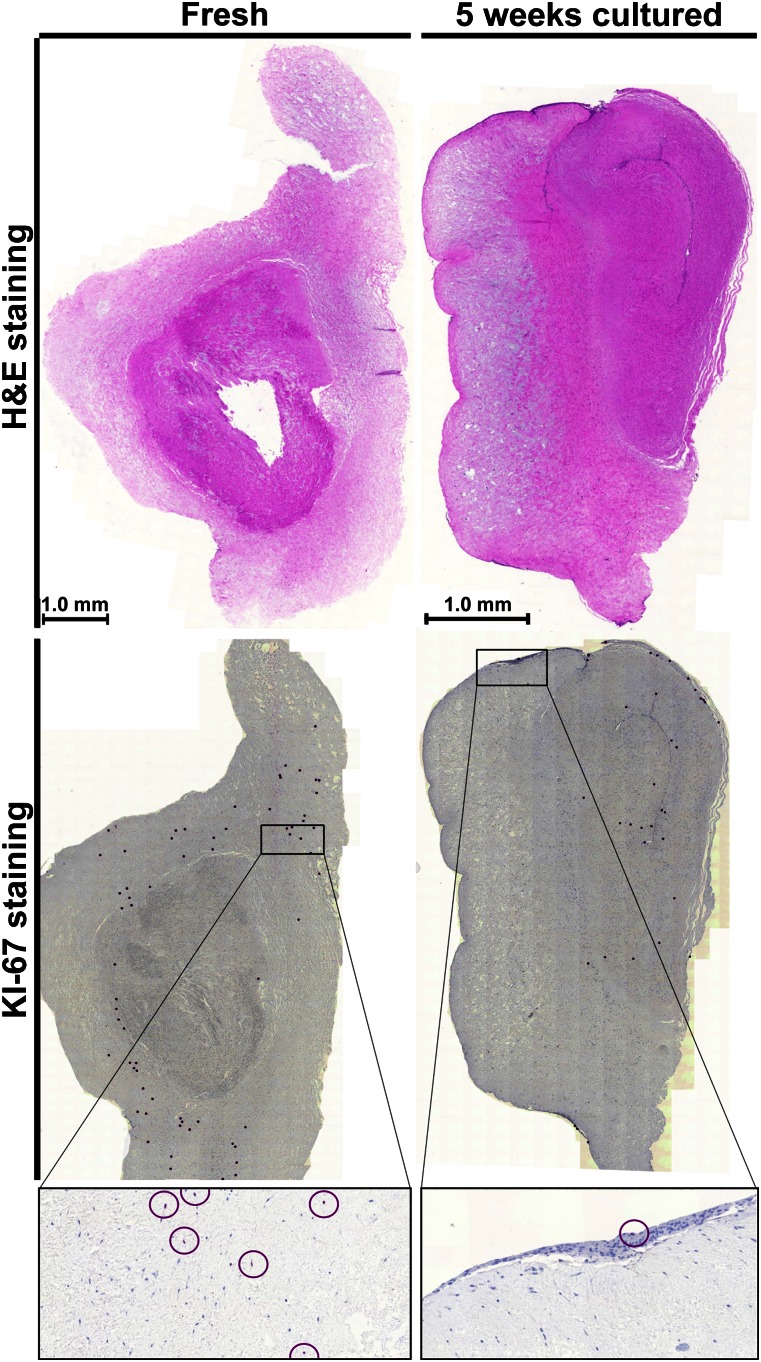

Because the transduction efficiencies of MSC-EMs never reached levels above 45%, we assumed the localization of MSC-I within the tissue piece to be important. Because the inducing cells have to proliferate to initiate a new MSC-EM, we investigated where proliferating cells can be found in general. We compared freshly isolated UCPs and pieces that had been cultivated for 5 weeks already (5WcP). The 5WcP were actively initiating MSC-EMs at the time point of staining. We identified dividing cells by Ki-67 immunohistochemistry, a very specific marker for proliferation. In parallel, we also performed conventional hematoxylin and eosin staining on serial sections to visualize the general morphologic changes during prolonged cultivation (Fig. 2). H&E staining of the fresh piece showed a blood vessel evenly surrounded by Wharton’s jelly. The 5WcP contained a collapsed blood vessel with most of the Wharton’s jelly on one side. The cultured UCP was smaller and the tissue more compact compared with the fresh piece. The Ki-67 staining results implied a different localization of dividing cells in fresh and cultivated UCPs. Most of the proliferating cells in the fresh piece were located in the Wharton’s jelly. In contrast, dividing cells of the cultivated UCP were mostly associated with the blood vessel and the periphery of the piece. Interestingly, UCPs lacking blood vessels lost their capability to induce explant cultures during prolonged cultivation (data not shown). Whether the dividing cells of the fresh piece migrated from their medial position toward the periphery over time to initiate MSC-EMs cannot be answered with this staining. However, our findings implied the need to find optimal transduction conditions to also reach cells deeper within the pieces.

Figure 2.

Histological and immunohistochemical proliferation staining of fresh and 5 weeks cultivated umbilical cord piece (UCP). The left column shows fresh and the right column 5 weeks cultivated UCP. The first row depicts the histological staining (H&E staining) and the second row the immunostaining of proliferating cells (anti-Ki-67 antibody). Nuclei of proliferating cells are highlighted with purple circles, and nuclei of nonproliferating cells are blue. The last row is a magnification of the Ki-67 staining.

Effects of Transduction Methods on Labeling MSC-Initiating Cells in UCPs

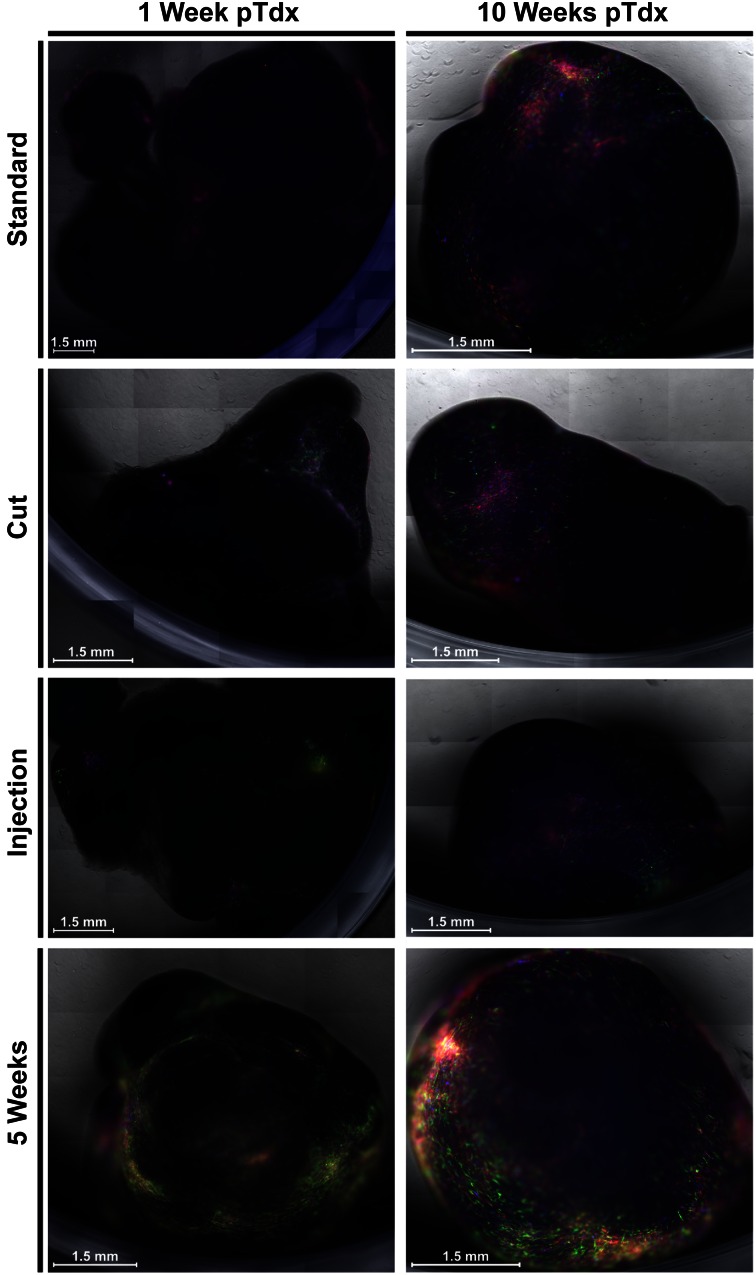

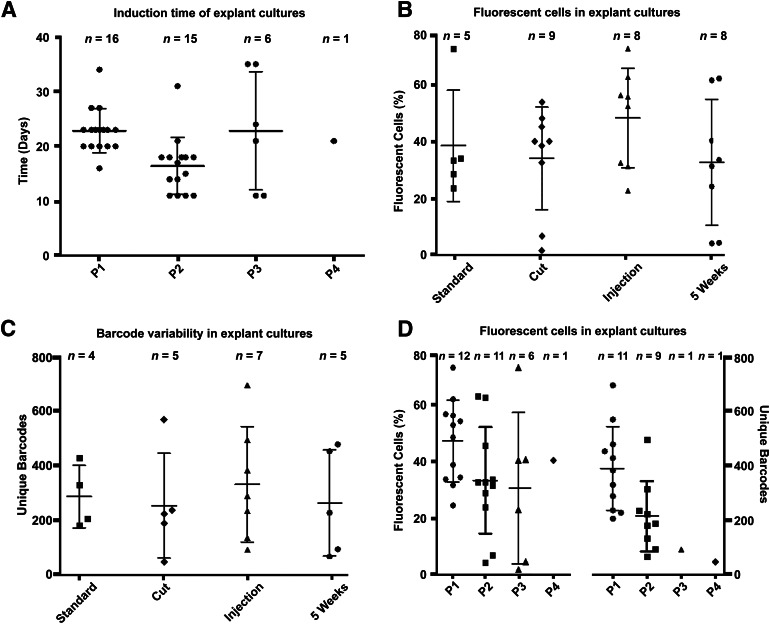

To enhance the overall transduction efficiency of MSC-I, we adapted our standard protocol by either increasing the accessible surface of the UCP or by injecting the viral particles directly into the pieces (up to eight times at different locations). A mild enzymatic digestion was incompatible with the transduction procedure (supplemental online Fig. 4). To increase the surface, we cut the UCP into half, prior to adding the viral supernatant. Similar to the standard technique, this led to mainly superficial transduction of the UCP. In contrast, the injection method resulted in distinct transduced spots. We followed the color distribution based on RGB marking within the UCP by microscopic evaluation for several weeks. In Figure 3, transduced pieces are shown either early after transduction (1 week) or after 10 weeks of in vitro culture. Regardless of the transduction method used, the amount of labeled cells increased over time. Our proliferation staining already implied that the time of transduction might be an important factor, because more MSC-I could have migrated toward the surface of the UCP during culture. Consequently, because we mostly transduced the surface of pieces, this should lead to a more efficient labeling of MSC-I and hence to more fluorescent-positive MSC-EMs. To test this hypothesis, we transduced pieces that had been in culture for 5 weeks. As shown in Figure 3, this led to higher numbers of marked cells early (1 week) after transduction. Unlike the freshly labeled UCP, however, we did not observe a further increase of transgene-positive cells in the 5WcP. Explant cultures were induced every 21 days. We did not observe a significant decrease in initiation times within a period of 100 days, supporting the idea of UCPs to serve as long lasting sources of MSC cultures (Fig. 4A). Our main readout for a successful transduction of MSC-I focused on the frequency of transduced MSC-EMs by flow cytometry (Fig. 4B). Even though the UCP seemed to show differences in RGB marking in fluorescence microscopy, especially for the 5WcP, we did not observe an increase in gene-marked MSC-EMs growing out from the UCP. Hence, the number of labeled MSC-I seemed to be similar between fresh and cultured pieces and independent from the transduction method.

Figure 3.

Fluorescent microscopic comparison of the transduction methods and the development of transgene expression in whole tissue pieces. Fresh and 5 weeks cultivated umbilical cord piece (UCP) were transduced with three viruses either coding for mCherry (red), Cerulean (blue), or Venus (green). Fresh pieces were additionally cut in half to increase the surface of the pieces. Alternatively, the virus was injected in UCP. Depicted is the midlayer of the UCP 1 week (left) or 10 weeks (right) posttransduction. Abbreviation: pTdx, posttransduction.

Figure 4.

Analysis of transduced umbilical cord piece (UCP)-derived mesenchymal stem cell explant monolayer (MSC-EM). Whole UCPs were transduced with three different viruses coding for fluorescent proteins and a genetic barcode. After 21 days, the first MSC-EM grew out. (A): Induction time between consecutive MSC-EMs. (B): Flow cytometric analysis of overall transgene positive cells in MSC-EM arranged by transduction method. (C): Amount of unique barcodes in MSC-EM arranged by transduction method. (D): Flow cytometry and unique barcodes in MSC-EM arranged by the order of induction. The data are represented by means, and error bars show the standard deviation. Abbreviations: P1–4, passage of UCP to new cell culture well.

Barcode Complexity in UCPs and MSC-EMs Early After Initiation

A more precise assessment of clonality of either UCPs or MSC-EMs was achieved by analyzing the development of the barcode diversity. First, we investigated the overall barcode complexity within the pieces. We used the complete DNA from a tissue piece and amplified the barcodes in two separate reactions before subjecting the samples to ITS. All sequences containing valid barcodes were clustered for homology, resulting in an increased read count for identical sequences. The read count served as a surrogate marker for clonal abundance, so that the contribution of a barcode was assumed to be proportional to the frequency of cells containing this individual genetic tag. According to the RGB labeling of UCPs in fluorescence microscopy, we expected to find a high number of different barcodes in the 5-week-old pieces. Supplemental online Figure 5 shows the total amount of unique barcodes with regard to the transduction method used. Interestingly, we did not find significant differences between the gene transfer approaches. Next, we analyzed the MSC-EMs originating from those pieces for their barcode complexity. The number of unique barcodes was approximately 10 times lower in the MSC-EMs compared with the respective UCPs and did not correlate with the measured frequency of fluorescence-positive cells in flow cytometry (supplemental online Fig. 6). Also on the barcode level, we did not observe differences in gene marking in relation to the various transduction methods (Fig. 4C). Flow cytometric analysis of the MSC-EMs in order of induction showed no differences in the number of fluorescent-positive cells, but a decrease in barcode variability in later-induced MSC-EMs (Fig. 4D).

Clonal Selection During Expansion of MSC Monolayer Cultures

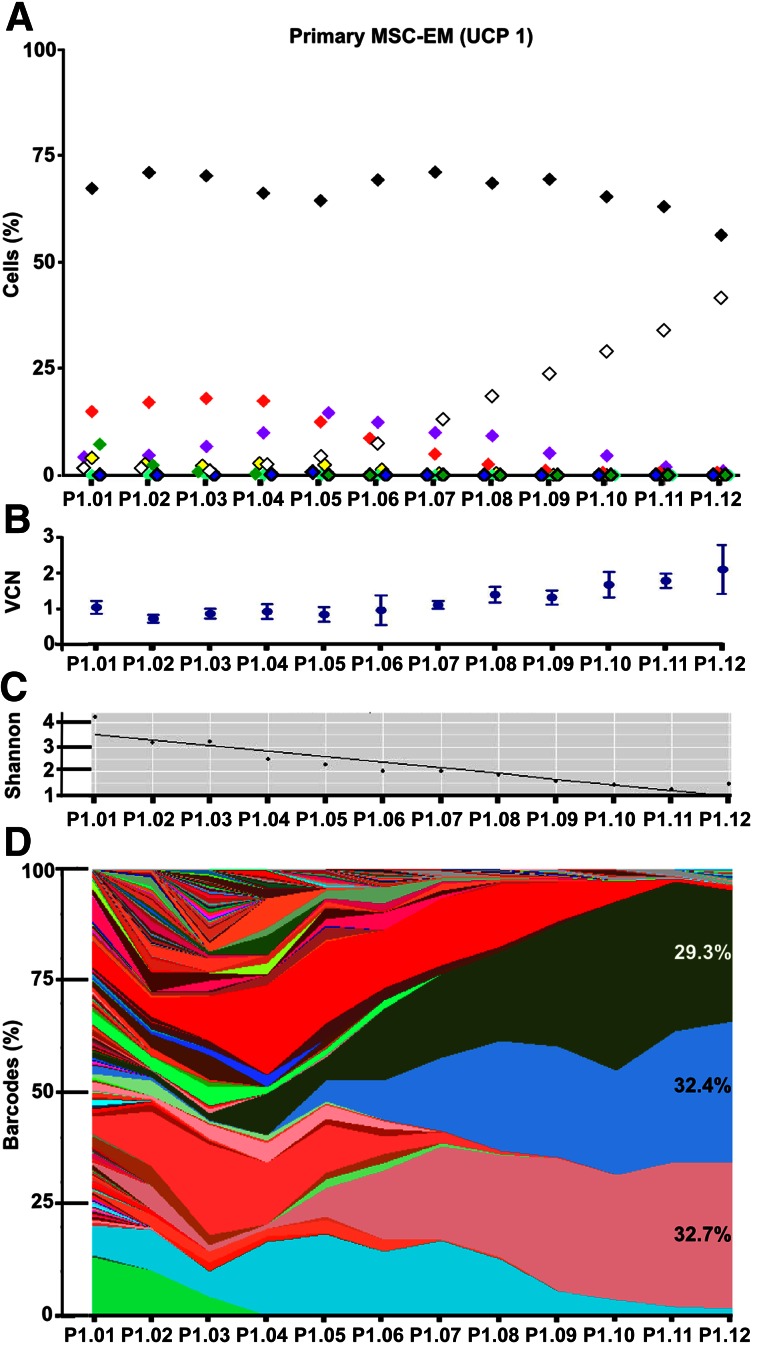

We further investigated whether monolayer cultures, once initiated, remained stable in their clonal repertoire, or if an expansion would lead to selection of certain clones. We screened more than 20 unique MSC-EMs over several passages by flow cytometry. None of the explant cultures remained stable in their color repertoire. In Figure 5, we depict one representative example MSC-EM culture over time. The colors of the symbols in Figure 5A represent the color of the cell fraction measured by flow cytometry (where black indicates unlabeled cells). The fraction of fluorescence negative cells remained stable at 68% (±4%), before decreasing to 57% at passage 12. A red cell fraction contributed with approximately 10% to the overall cell pool until passage 4 and disappeared after passage 8. A purple fraction first appeared with 5% in flow cytometry, increased to 15% at passage 5, and gradually decreased until passage 12. Intriguingly, a white clone (with at least one copy of every transgene) was first detected with a contribution below 2% and increased from passage 4 by 12%–42%. The mean vector copy number (VCN) of the bulk culture first fluctuated around one copy per diploid genome (Fig. 5B). From passage 5 to 12, the VCN increased and followed the kinetics of the upcoming white clone. This increase can be explained by the reduction in vector-negative cells together with the clonal selection of the white cells with a VCN of at least 3. This loss of barcode diversity became even more obvious when we analyzed the dynamics of individual barcodes. Overall, clonal complexity can be assessed by using the Shannon index (Fig. 5C), measuring how many different barcodes were found in a sample and how evenly they contributed to the total sequence pool. In a very complex sample, we observed a high amount of different barcodes with low read counts and consequently also a high Shannon index. In samples with a loss in clonal diversity, the Shannon index dropped as the number of individual barcodes became fewer and the read counts for some barcodes became dominant. In the described MSC-EM sample, the Shannon index decreased from 4.2 (ca. 70 clones) to 1.3 (3.7 clones) in the course of expansion. This general loss of clonal complexity in the expanded MSC-EM cultures is further demonstrated by using stacked frequency charts (Fig. 5D). The contribution of each individual barcode to all sequences over time is displayed as a colored area. Shortly after MSC-EM induction, a variety of barcodes contributed to the complex starting culture. The first severe loss of diversity was observed within the first three passages already. Another major loss of barcodes occurred after passage 5, where mainly three mCherry, two Cerulean, and one Venus barcode became dominant. In flow cytometry at the same time, mainly fluorescence-negative, purple, red, and some white cells were detected. Consequently, three mCherry barcodes were likely to be found in the red, purple, and white cell population. The two Cerulean barcodes were assumed to be a tag of the purple and white cell population, and the Venus barcode was found only in the white cell fraction. At passage 9, one of the mCherry barcodes started to disappear, at the same time when the red cell population was not detectable by flow cytometry anymore. After passage 12, only three dominant barcodes were found in the sequencing result, one of each color. These results highlight the opportunity to follow global culture dynamics in flow cytometry and to assign unique barcodes to individual cell fractions. Explant cultures from independent UCPs showed similar decreases in barcode variability (supplemental online Fig. 7A, 7B). The first loss of clonal complexity is usually found very early after culture initiation, when all cells lacking an MSC phenotype disappear from the culture. A second drop of barcode diversity can be observed during expansion, when specific clones become dominant. This change in clonal complexity was also recapitulated by the proliferation rate of the mass culture, which changed depending on the clonal composition over time (supplemental online Fig. 6C).

Figure 5.

Clonal development of one exemplary MSC-EM. (A): Flow cytometric analysis of the clonal development. The graph displays the percentage of fluorescence-positive cells, and the color of the symbol indicates the color of the respective cell population (black indicates fluorescent-negative cells). The development of the mass culture during the first 12 passages (P1.01 to P1.12) of the primary MSC-EM culture is shown. (B): Vector copy number analysis of mass cultures by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Data are displayed as means ± SD. (C): Shannon index describing the diversity of the barcodes in the mass culture. (D): Area plot of the barcode contribution. Each area represents an individual barcode from one of the vector constructs (different shades of the colors red, blue, and green refer to the RGB construct the barcode originated from). The percentages show the contribution of a barcode after the last passage in case it contributed >5% to the total sequencing reads. Abbreviations: MSC-EM, mesenchymal stem cell explant monolayer; P, passage; UCP, umbilical cord piece; VCN, vector copy number.

A Limited Amount of MSC-I Clones Induce the Monolayer Cultures

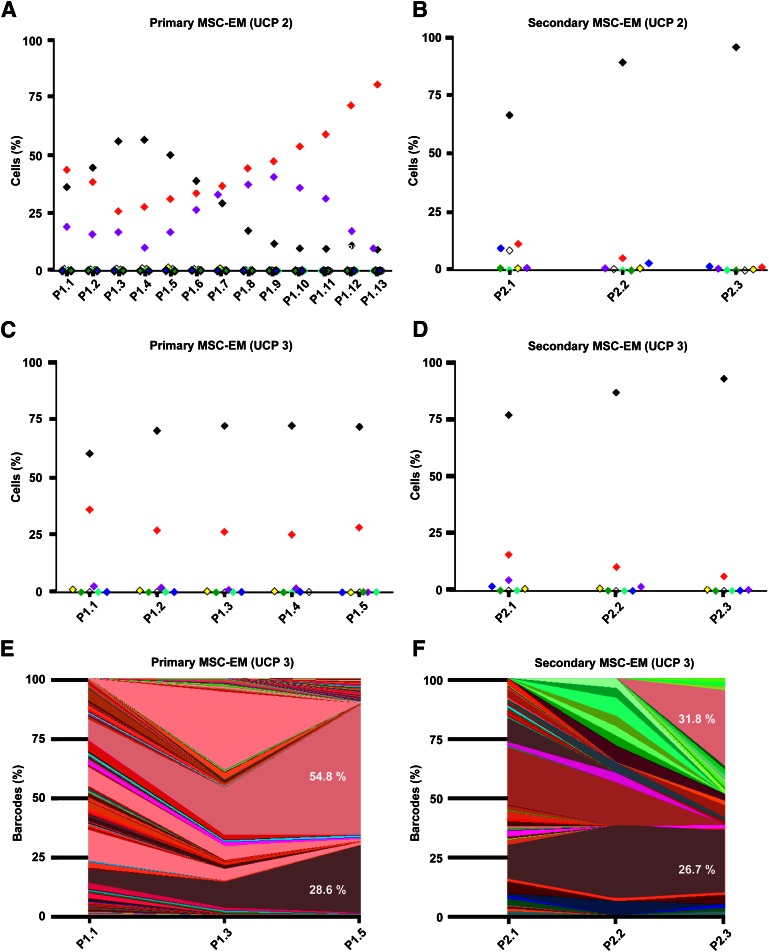

We investigated whether the same MSC-I clones from one UCP always gave rise to explant monolayers. To answer this question, we compared consecutive primary (P1.x) or secondary (P2.x) explant cultures of two individual UCPs (1 and 2). The flow cytometry results of the primary MSC-EM from UCP 1 are depicted in Figure 6A and showed negative (36%), red (44%), and purple (19%) cells after monolayer initiation (P1.1). The culture consisted of 80% red cells after passage P1.13. In contrast, the secondary MSC-EM of UCP 1 showed red (11%), white (9%), blue (10%), and negative (36%) cells in flow cytometry, already indicating differences in MSC-I cells within UCP 1 (Fig. 6B). After three passages, the secondary MSC-EM was confined to 95% of negative cells (P2.3), implying that progeny of a different MSC-I cell took over the culture. These results imply that UCP probably contain several MSC-I. The primary MSC-EM of UCP 2 is depicted in Figure 6C and consisted of a red (34%) and a negative (60%) cell population. We observed only a limited fluctuation in the color composition until passage P1.5 (Fig. 6C). The secondary MSC-EM contained negative (77%), red (16%), and purple (6%) cells at the beginning of culture and a restricted composition of negative (93%) and red (6%) cells after passage P2.3 (Fig. 6D). Further analysis by barcode sequencing revealed a drastic restriction of diversity to only two mCherry barcodes, which were identical between the primary and secondary MSC-EMs from UCP 2 (Fig. 6E, 6F). This selection of identical barcodes from consecutive MSC-EMs suggests a long-lasting, but limited, fraction of progenitor cells, which continuously give rise to new MSC cultures.

Figure 6.

Clonal development of consecutive MSC-EM. Analysis of MSC-EM of two individually transduced UCP (UCP 2, UCP 3). Colors of the symbols and areas indicate fluorescent proteins coded by the vectors. (A): Flow cytometric analysis of the first 13 passages (P1.1 to P1.13) of the primary MSC-EM of UCP 2. (B): Flow cytometric analysis of the first 3 passages (P2.1 to P2.3) of the secondary MSC-EM of UCP 2. (C): Flow cytometry analysis of the first 5 passages (P1.1 to P1.5) of the primary MSC-EM of UCP 3. (D): Flow cytometry analysis of the first 3 passages (P2.1 to P2.3) of the secondary MSC-EM of UCP 3. (E): Area plot of the barcode distribution of the first 5 passages (P1.1 to P1.5) of the primary MSC-EM of UCP 3. (F): Area plot of the barcode contribution of the first 3 passages (P2.1 to P2.3) of the secondary MSC-EM of UCP 3. The percentage show the contribution after the last passage, if it was >5%. The two dominant barcodes for the primary and secondary MSC-EM of UCP 3 were identical. Abbreviations: MSC-EM, mesenchymal stem cell explant monolayer; P, passage; UCP, umbilical cord piece.

Tube Formation Assay Shows Different Functional Properties of Clones

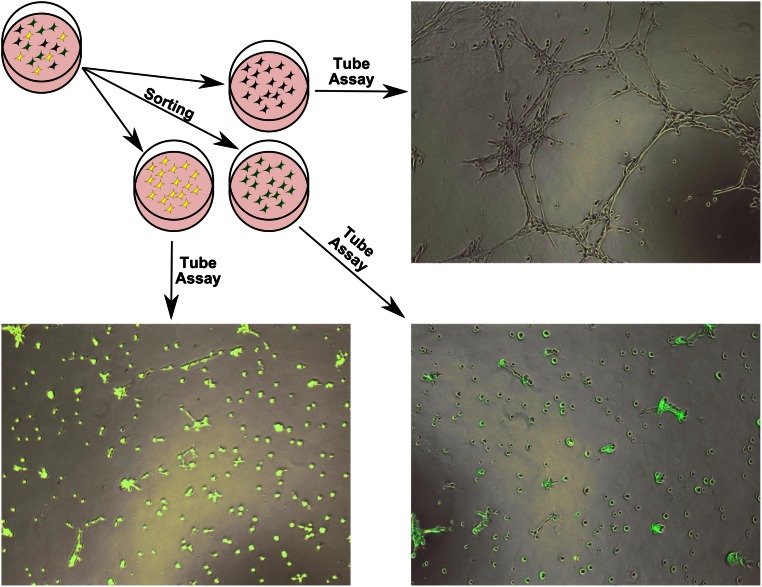

Finally, we investigated whether different clones possess different properties. As a proof of principle, we chose a Matrigel assay in which MSCs can form tube-like structures. This tube formation assay was previously described by Gomes et al. [23]. A freshly initiated MSC-EM was expanded to a six-well size before the cells were sorted by fluorescent color. Technical replicates of three resulting populations (green, yellow, and negative) were cultivated for 1 week in an endothelial growth medium (EGM-2). Afterward, cells were seeded on Matrigel, where they normally form tube-like structures. Four hours after seeding, tube formation was analyzed by microscopy. All replicates of the fluorescent-positive cells had a strongly reduced tube formation potential, whereas the negatively sorted population showed normal tube-like structures (Fig. 7). This shows that MSC mass cultures are composed of cells with different functional properties.

Figure 7.

Tube formation assay with different fluorescence sorted clones. A freshly initiated mesenchymal stem cell explant monolayer was first expanded, before cells were sorted by the present colors green, yellow, and negative. A tube formation assay was performed in triplicate with the different sorted populations. Depicted is microscopic fluorescence overlay after 4 hours. The yellow and green population had a strongly reduced tube formation capability compared with cells from the fluorescence negative population. Magnification, ×5.

Discussion

Despite their broad application in clinical trials for the treatment of a variety of diseases, the definition of unique surface markers to directly isolated MSCs has not been achieved so far [25]. Regardless of the tissue source, MSC monolayer cultures have to be expanded to yield clinically relevant cell numbers [26]. During the first 2 weeks of culture establishment, the cell population is quite heterogeneous and only develops the typical homogenous phenotype during expansion. How many cells are able or necessary to initiate such a culture, and how the clonal composition changes over time, are still unanswered questions [27]. RGB barcode-marking technology is a powerful tool to analyze clonal development on different empirical levels [18]. In our current study, we used this technique to investigate umbilical cord tissue as a constant source of MSC cultures and observed a general clonal selection pressure during the inevitable expansion phase, already shortly after initiation.

Previously, Otte et al. reported a continuous outgrowth of MSC-EMs from cultivated umbilical cord pieces [15]. Whereas monolayer cultures alone showed signs of senescence after 6 weeks, separately cultured UCPs kept initiating new MSC-EMs over months, raising the question of a stem cell-preserving niche in the tissue piece. This would represent an advantage over other MSC sources, where this microenvironment is normally destroyed by enzymatic digestion of the tissue during isolation. MSCs or their direct progenitors have to proliferate inside the UCP and migrate toward the periphery of the pieces, to initiate monolayer cultures. We applied Ki-67 immunohistochemistry to identify actively dividing cells in freshly isolated or cultured UCP. Shortly after preparation of the umbilical cord, proliferating cells were detected mostly in the Wharton’s jelly. In contrast, cultivated pieces showed dividing cells at the periphery and around the collapsed umbilical vessel wall. Several groups suggested a pericytic origin of MSC [10, 28], which would be in line with our observation that nonvascularized tissue pieces lost their MSC-EM initiation potential over time. Consequently, some MSC initiating progenitors are supposedly located in the Wharton’s jelly, whereas the stem cell microenvironment is mostly maintained around the blood vessels.

For our RGB barcode-marking experiments, we aimed to label MSC-I in intact UCPs. Because we did not know the exact localization of these cells, we tried different time points and methods of lentiviral transduction. In particular, we performed gene transfer to fresh pieces or UCPs, which were actively giving rise to MSC-EMs. Additionally, fresh pieces were either cut in half to increase the surface, mildly digested to promote access of virus to the inner cells, or injected with viral supernatant to reach cells deeper in the UCP. Enzymatic digestion shortly before the time of transduction turned out to be incompatible with gene transfer, further cultivation of intact UCP, and MSC-EM initiation. This was likely because of the fact that remaining enzymes after incomplete removal also negatively affect the viral particles. Simple addition of vector supernatant to UCP resulted in reproducible but mainly superficial gene marking. Injection into pieces yielded transduced spots together with labeled cells at the periphery, which could be explained by backflow of viral supernatant from the injection canal into the medium. None of our attempts resulted in a transduction efficiency above 40% of labeled MSC-EM growing out from the pieces. These results imply that we did reach a population of MSC-initiating cells, but failed to access another population located in deeper tissue layers, possibly around the vessel structures. In line with this finding, analysis of the barcode diversity of whole pieces did not reveal a significant difference in the labeling efficiency between different transduction methods.

Shortly after transduction of fresh pieces, the total number of labeled cells in fluorescence microcopy was low in comparison with later time points, when the same pieces were analyzed again. In contrast, UCP, which had been transduced after 5 weeks in culture, showed a high amount of initially labeled cells, but no further increase in gene marking. However, the number of fluorescence-positive MSC-EMs growing out from the pieces was not different between fresh and cultivated pieces. This observation is important, because it suggests that we transduced mostly short-lived cells in the older pieces and that there is only a limited pool of MSC-I in the umbilical cord tissue. This assumption is further supported by the observation of a lower barcode variability in secondary and tertiary MSC-EMs from the same piece.

When we analyzed single MSC-EMs over time, we observed a strong clonal selection after passaging. Initially starting with hundreds of different barcodes and often a diverse color composition, only a few barcodes became dominant over time as fluorescent markers showed a reduced complexity. In line with our observations, Schellenberg et al. described changes in subpopulations during in vitro expansion [27]. Additionally, we observed a change of proliferation rate in the mass cultures at time points of barcode diversity reduction. This happened predominantly after passage 5–9 and potentially displayed the growth rate of those clones, which were about to become dominant. Because of the limited transduction efficiency of whole tissue pieces and possibly the location of MSC-I cells, we also observed a high contribution of unlabeled cells in our MSC-EM cultures. Sometimes the transduced cells diminished, when unlabeled cells became selected, whereas at other times the marked cells dominated over time. This dominance was different among the consecutive MSC-EMs, and no dominance was observed in the UCP. This observation argues against the possibility that the clonal selection was generally triggered by insertional mutagenesis because of the lentiviral vector transduction.

We analyzed the overlap of barcodes and the clonal development in consecutive primary and secondary MSC-EMs from the same UCP. Generally, we observed only a minor overlap, suggesting the existence of several MSC-I in the tissue pieces. However, in some explant cultures, dominant clones carried identical barcodes. Despite the fact that most of the cells in the secondary MSC-EMs were fluorescence-negative, at least the labeled fraction contained the same selected subclone, suggesting a limited number of MSC-I in UCP. The existence of subpopulations within MSC cultures has also been described by other groups according to differences in surface markers, whole genome sequencing, and functional characteristics [29–33]. The best resolution so far was achieved with single colony-derived strains and the linkage to functional properties by Sworder et al. [34].

Finally, we analyzed whether different clones have different functional properties. We used a tube formation assay with cells sorted by color. Although the three different populations originated from the same MSC-EM, only one population efficiently formed tubes in all replicates, highlighting different capabilities among clones. Despite several functional in vitro tests, like trilineage differentiation or the tube formation assay, the predictive value in terms of clinical translation remains doubtful. We believe the tube-like structure formation to be a specialized surrogate assay in terms of functionality. Because the secretion of various instructive cytokines by MSC is believed to be one of major factors accounting for their in vivo regenerative potential, future studies should focus on differences in the expression of these factors by specific clones.

Conclusion

We observed clonal selection of UCP-derived MSC-EMs, which can be explained by complex proliferation dynamics and a small set of long-term proliferating progenitors. Furthermore, we could also demonstrate functional differences among clones. In particular, temporary contribution of clones to the expanded culture might explain sources of variation seen in MSC in vitro experiments or potentially even clinical trials. Our study also showed the suitability of UCP transduction with lentiviral vectors coding for fluorescent proteins and genetic barcodes as a tool for clonal development analysis. Future studies should aim to analyze the consequences of the clonal dynamics on functional difference between MSC cultures and the possibility to manipulate this outcome by the choice of different culture conditions. This will help to identify conditions for the generation of clinically applicable MSCs with less heterogeneity and better reproducibility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Constantin von Kaisenberg (Hannover Medical School) for preparing the umbilical cord and the Research Core Unit Next Generation Sequencing, especially Lutz Wiehlmann, Martin Stanulla, and Sabine Schreek of the Hannover Medical School, as well as the Leiden University Medical Center, for excellent help with ion torrent sequencing. This work was supported by the European Union Seventh Framework Project CELL-PID and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants FE568/11-2, Cluster of Excellence REBIRTH (Exc 62/1), and SFB 738.

Author Contributions

A. Selich and M.R.: conception and design, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript; J.D.: collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation; R.H.: conception and design, collection and/or assembly of data; F.P., G.P., and S.R.: collection and/or assembly of data; C.v.K.: provision of study material, administrative support; K.C. and B.F.: provision of study material, manuscript writing, data analysis and interpretation; A. Schambach: conception and design, financial support, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Friedenstein AJ, Petrakova KV, Kurolesova AI, et al. Heterotopic of bone marrow. Analysis of precursor cells for osteogenic and hematopoietic tissues. Transplantation. 1968;6:230–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boxall SA, Jones E. Markers for characterization of bone marrow multipotential stromal cells. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:975871. doi: 10.1155/2012/975871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma RR, Pollock K, Hubel A, et al. Mesenchymal stem or stromal cells: a review of clinical applications and manufacturing practices. Transfusion. 2014;54:1418–1437. doi: 10.1111/trf.12421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffin MD, Ritter T, Mahon BP. Immunological aspects of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell therapies. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:1641–1655. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wuchter P, Bieback K, Schrezenmeier H, et al. Standardization of Good Manufacturing Practice-compliant production of bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stromal cells for immunotherapeutic applications. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGuirk JP, Smith JR, Divine CL, et al. Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stromal cells as a promising cellular therapeutic strategy for the management of graft-versus-host disease. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2015;8:196–220. doi: 10.3390/ph8020196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhn NZ, Tuan RS. Regulation of stemness and stem cell niche of mesenchymal stem cells: Implications in tumorigenesis and metastasis. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:268–277. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramann R, Schneider RK, DiRocco DP, et al. Perivascular Gli1+ progenitors are key contributors to injury-induced organ fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:51–66. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crisan M, Huard J, Zheng B, et al. Purification and culture of human blood vessel-associated progenitor cells. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol. 2008;Chapter 2:Unit 2B.2.1–2B.2.13. doi: 10.1002/9780470151808.sc02b02s4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aurich H, Sgodda M, Kaltwasser P, et al. Hepatocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from human adipose tissue in vitro promotes hepatic integration in vivo. Gut. 2009;58:570–581. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.154880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hou L, Cao H, Wang D, et al. Induction of umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells into neuron-like cells in vitro. Int J Hematol. 2003;78:256–261. doi: 10.1007/BF02983804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trounson A, Thakar RG, Lomax G. et al. Clinical trials for stem cell therapies. BMC Med. 2011;9:52. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hass R, Kasper C, Böhm S, et al. Different populations and sources of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC): A comparison of adult and neonatal tissue-derived MSC. Cell Commun Signal. 2011;9:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otte A, Bucan V, Reimers K, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells maintain long-term in vitro stemness during explant culture. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2013;19:937–948. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2013.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber K, Thomaschewski M, Warlich M, et al. RGB marking facilitates multicolor clonal cell tracking. Nat Med. 2011;17:504–509. doi: 10.1038/nm.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber K, Thomaschewski M, Benten D, et al. RGB marking with lentiviral vectors for multicolor clonal cell tracking. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:839–849. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornils K, Thielecke L, Hüser S, et al. Multiplexing clonality: Combining RGB marking and genetic barcoding. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muskhelishvili L, Latendresse JR, Kodell RL, et al. Evaluation of cell proliferation in rat tissues with BrdU, PCNA, Ki-67(MIB-5) immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization for histone mRNA. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:1681–1688. doi: 10.1177/002215540305101212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voelkel C, Galla M, Dannhauser PN, et al. Pseudotype-independent nonspecific uptake of gammaretroviral and lentiviral particles in human cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23:274–286. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber K, Bartsch U, Stocking C, et al. A multicolor panel of novel lentiviral “gene ontology” (LeGO) vectors for functional gene analysis. Mol Ther. 2008;16:698–706. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraunus J, Schaumann DHS, Meyer J, et al. Self-inactivating retroviral vectors with improved RNA processing. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1568–1578. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomes SA, Rangel EB, Premer C, et al. S-Nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR) enhances vasculogenesis by mesenchymal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:2834–2839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220185110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothe M, Rittelmeyer I, Iken M, et al. Epidermal growth factor improves lentivirus vector gene transfer into primary mouse hepatocytes. Gene Ther. 2012;19:425–434. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Augello A, Kurth TB, De Bari C. Mesenchymal stem cells: A perspective from in vitro cultures to in vivo migration and niches. Eur Cell Mater. 2010;20:121–133. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v020a11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartmann I, Hollweck T, Haffner S, et al. Umbilical cord tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells grow best under GMP-compliant culture conditions and maintain their phenotypic and functional properties. J Immunol Methods. 2010;363:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schellenberg A, Stiehl T, Horn P, et al. Population dynamics of mesenchymal stromal cells during culture expansion. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:401–411. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.640669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Silva Meirelles L, Chagastelles PC, Nardi NB. Mesenchymal stem cells reside in virtually all post-natal organs and tissues. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2204–2213. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mabuchi Y, Houlihan DD, Akazawa C, et al. Prospective isolation of murine and human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells based on surface markers. Stem Cells Int. 2013;2013:507301. doi: 10.1155/2013/507301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Espagnolle N, Guilloton F, Deschaseaux F, et al. CD146 expression on mesenchymal stem cells is associated with their vascular smooth muscle commitment. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:104–114. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majore I, Moretti P, Hass R, et al. Identification of subpopulations in mesenchymal stem cell-like cultures from human umbilical cord. Cell Commun Signal. 2009;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai J, Miao X, Li Y, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies genetic variances in culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;3:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner W, Feldmann RE, Jr, Seckinger A, et al. The heterogeneity of human mesenchymal stem cell preparations—evidence from simultaneous analysis of proteomes and transcriptomes. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:536–548. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sworder BJ, Yoshizawa S, Mishra PJ, et al. Molecular profile of clonal strains of human skeletal stem/progenitor cells with different potencies. Stem Cell Res (Amst) 2015;14:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.