Buckle fractures of the distal radius are common in children between 2 and 12 years of age

Buckle (torus) fractures occur when the bony cortex is compressed and bulges, without extension of the fracture into the cortex (Figure 1). This type of fracture occurs in about 1 in 25 children and represents 50% of pediatric fractures of the wrist.1 Cosmetic or functional consequences have not been reported in association with buckle fractures.2

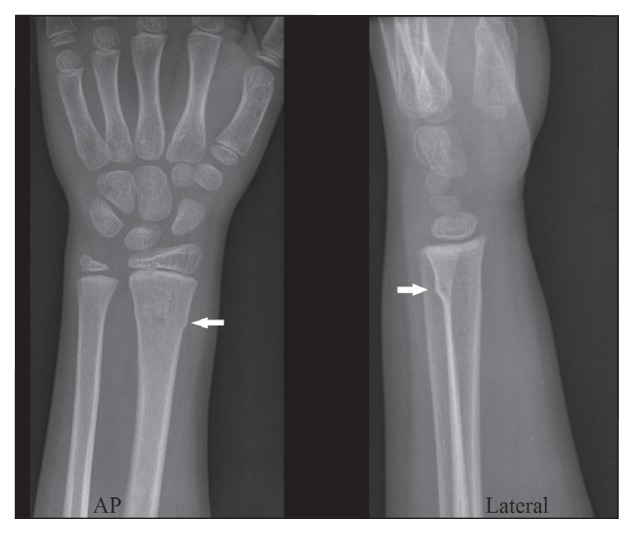

Figure 1:

A buckle fracture of the distal radius in a six-year-old child. Arrows point to buckling of the cortex.

Treatment with a removable splint is just as effective as a short arm cast

Evidence from randomized controlled trials shows that children with this type of injury who are given a removable splint have better physical function, less difficulty with daily activities and a strong parental preference for the splint compared with children given a short arm cast.3 In Canada, 60% of emergency physicians currently treat buckle fractures of the distal radius with a removable splint.4

Splint use and return to play should be guided primarily by pain

Immobilization with a splint is used as needed to reduce pain and to protect against re-injury. Most children use the splint regularly for two to three weeks.4 Activities that could lead to re-injury should be avoided until the child has been free of symptoms for two weeks. Typically, most children resume full activities within four to six weeks.4

Follow-up with an orthopedic surgeon is not routinely necessary

Observational studies support the follow-up of this injury with a primary care physician.4 If clear instructions about splint use and the return to activities are provided at discharge in the emergency department, no physician follow-up is an option.5 An orthopedic surgeon should be consulted if the child’s condition is not improving over time or the child has not fully recovered by six weeks.4

Radiographs should be scrutinized for other diagnoses

Minimally displaced greenstick and Salter–Harris II fractures of the distal radius (see examples in Appendix 1, at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.151239/-/DC1) may be mistaken for buckle fractures. These injuries require urgent outpatient orthopedic consultation within one week.2

CMAJ invites submissions to “Five things to know about …” Submit manuscripts online at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/cmaj

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Naranje SM, Erali RA, Warner WC, Jr, et al. Epidemiology of pediatric fractures presenting to emergency departments in the United States. J Pediatr Orthop 2015. July 14 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkins KE. Principles of fracture remodeling in children. Injury 2005;36:A3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plint AC, Perry JJ, Correll R, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of removable splinting versus casting for wrist buckle fractures in children. Pediatrics 2006;117:691–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koelink E, Schuh S, Howard A, et al. Primary care physician follow-up of distal radius buckle fractures. Pediatrics 2016;137:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Symons S, Rowsell M, Bhowal B, et al. Hospital versus home management of children with buckle fractures of the distal radius: a prospective, randomised trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001;83:556–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.