Abstract

Consumption of fruits and vegetables is associated with a lower risk of developing many chronic health conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. While five or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day are recommended, only 50 % of New York City (NYC) residents consume two or more servings per day. In addition, there is wide variation in dietary behaviors across different neighborhoods in NYC. Using a validated agent-based model and data from 34 NYC neighborhoods, we simulate how a mass media and nutrition education campaign strengthening positive social norms about food consumption may potentially increase the proportion of the population who consume two or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day in NYC. We found that the proposed intervention results in substantial increases in daily fruit and vegetable consumption, but the campaign may be less effective in neighborhoods with relatively low education levels or a relatively high proportion of male residents. A well-designed, validated agent-based model has the potential to provide insights on the impact of an intervention targeting social norms before it is implemented and shed light on the important neighborhood factors that may affect the efficacy of the intervention.

Keywords: Urban health, Neighborhoods, Social norms, Nutrition education, Agent-based modeling

Introduction

Both the World Health Organization and the United States (US) Department of Health and Human Services have published reports that emphasize the importance of having a healthy diet on population health.1,2 A diet high in fruits and vegetables has proved to be a protective factor for many chronic health conditions such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.3–5 In addition, high consumption of fruits and vegetables in early life is associated with lower health care expenditures in older age.6 However, research has shown that most people in the USA do not consume enough fruits and vegetables; only about 30 % of women and 20 % of men report eating the recommended amount (five servings or more) of fruits and vegetables per day.7 Although great effort has been made at both the local and national levels to improve dietary behaviors, the consumption of fruits and vegetables has not increased significantly in recent years.8

The dietary behavior of New York City (NYC) residents is worse than the national average, as only about 10 % of adults consume five or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day.9 In addition, there are striking differences in the consumption of fruits and vegetables across different neighborhoods in NYC.10 For instance, residents in wealthier neighborhoods, such as the Upper East Side, consume more fruits and vegetables than residents of low-income NYC neighborhoods, such as the South Bronx. This difference in healthy eating patterns is likely due to a number of factors. For instance, residents of the Upper East Side have excellent access to fruit and vegetable markets and supermarkets, while the South Bronx is often considered a food desert with an overabundance of fast food restaurants and a lack of healthy food retailers. Studies have also found that exposure to advertising and marketing of unhealthy foods is greater in low-income, African-American, and Latino communities.11 Similarly, evidence suggests that the high cost of healthy foods, such as fresh fruits and vegetables, is a significant barrier to healthy eating for many low-income individuals and families.11

Interventions targeting social norms—such as mass media and nutrition education campaigns—have been shown to influence individuals’ eating behaviors.12–14 These interventions operate through the repeated exposure to media or education that influence the perceptions and cognition of individuals and align them in the direction of the marketed dietary pattern.15 In other words, these types of interventions can strengthen either positive or negative social norms with regard to dietary behaviors. For example, an experimental study showed that varying combinations of TV commercials for junk food and nutritious food can change children’s perceptions of social norms and, thus, influence their eating behaviors.16 Similar mechanisms come into play in other areas such as the perception of people toward violence; research has shown that TV viewers tend to overestimate the prevalence of violence because many TV channels display a higher prevalence of violence than what actually exists in society.17

A recent study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that most TV food commercials marketed unhealthy food such as snacks, soda, and fast food, and none of the reviewed advertisements were for fruits and vegetables.18 Constant exposure to media that promotes unhealthy food may pose a serious threat to population health; it may be an important driver for the tremendous increase in obesity during the past three decades.19,20 However, we hypothesize that interventions targeting social norms—such as mass media campaigns and community-based nutrition education programs promoting the consumption of fruits and vegetables—can improve dietary behaviors, and there is limited evidence on the extent to which these interventions influence dietary patterns.

In this study, we investigate whether a hypothetical mass media and nutrition education campaign may lead to increases in the consumption of fruits and vegetables across NYC neighborhoods characterized by diverse, disparate populations, and dissimilar food environments. Previous studies have shown that factors such as socioeconomic status (SES), the local food environment, and social influences (e.g., social norms) are directly associated with the consumption of fruits and vegetables in a neighborhood.21–25 Traditional statistical models have limited capacity to predict dietary behaviors because they do not fully capture complex interactions among people and spillover effects caused by these interactions.26,27

To address these concerns, we use a validated agent-based model—that takes into account individual and neighborhood-level factors (e.g., age, gender, education, the food environment) and their interactions—to predict dietary behaviors at the neighborhood level. The model explicitly captures individual decision-making regarding daily food choice, which are influenced by one’s cognitive habits related to dietary behaviors, income level, the influence of peers, access to healthy or less healthy food retailers, and food prices.28,29 Using this systems science model, we simulate a hypothetical mass media and nutrition education campaign and predict the impact of the intervention on the consumption of fruits and vegetables across different neighborhoods in NYC. We also identify important neighborhood factors that may lead to effect differences across groups after the simulated intervention.

Methods

We analyze how a hypothetical mass media and nutrition education campaign across NYC neighborhoods leads to changes in dietary behaviors by using an agent-based model that includes individual behaviors, the food environment, and social influences. The structure, parameterization, and validation of the model have been presented in a previous study.28 We briefly describe the main features of the model and characteristics of our studied populations here.

Model Structure

In our simulation model, an agent can be either an individual or a food outlet. Individuals differ by their demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and educational attainment. They also have different taste preferences (e.g., the extent to which they prefer the strong taste of sweet and salty foods), health beliefs (the extent to which they care about the healthiness of food), price sensitivity (the extent to which they have a strong preference for low-price foods), and abilities to access healthy or less healthy foods (whether a food outlet is within walking distance, defined as less than 1 mile). Food outlets include healthy outlets (supermarkets and fruit and vegetable markets) and less healthy outlets (limited service and full service restaurants). The geographic location of individuals and food outlets are dependent on the size and structure of the simulated neighborhood.

Individuals—who are connected in a social network—make a dietary choice during each simulated day between more healthy and less healthy food based on a probability function that is developed by analyzing data from the Food Attitudes and Behaviors Survey and other empirical studies.30–33 The function includes variables that represent health beliefs, taste preferences, price sensitivity, food accessibility, and demographic characteristics. The taste preferences and health beliefs of each individual are continuously updated in the model due to the influence of friends in the social network in each community. Each simulation was conducted for three years to account for the fact that social influences take time to converge and change dietary behaviors at the population level.28 The main simulation outcome is the proportion of the population in a given neighborhood who on average consume more than two servings of fruits and vegetables per day.

Population Characteristics

We extracted data on demographic characteristics from the 2010 US Census for each zip code in NYC. We then estimated demographic characteristics for each of the 34 United Hospital Fund (UHF) neighborhoods by combining the zip code area data within the particular neighborhood.34 We also estimated healthy diet levels—measured by the proportion of the population who consumed at least two servings of fruits and/or vegetables in the previous day—for the same 34 UHF neighborhoods from the NYC Community Health Survey (CHS) developed by the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.35

Social Network

The existence and importance of social networks is an important feature of urban environments.36,37 In our agent-based model, individuals in a given neighborhood are connected according to a type of social network called a “small world.”38 In a small world network, individuals form densely connected groups and any individual is influenced by others through only a few social ties. A wide variety of models that integrate small world networks have been developed to capture population interactions such as the spread of infectious disease and social influence on individual behaviors.36,39

Food Environment

We extracted data that characterizes the food environment in each of the zip code areas in NYC from the 2010 ZIP Code Business Patterns data provided by the US Census Bureau.40 We then estimated food environment parameters for each of the 34 UHF neighborhoods by combining data from the zip code areas that constitute a particular neighborhood. In our agent-based model, healthy food outlets included supermarkets (including larger grocery stores and supercenters) and fruit and vegetable markets while less healthy food outlets included full service and limited service restaurants. Our classification of food outlets is consistent with existing studies and is based on typical food offerings by these retailers.24,41

Intervention

An example of the simulated mass media and nutrition education campaign would be a program recently implemented to improve fruit and vegetable consumption among Latino adults in Fresno, California.42 The program used both a mass media campaign (e.g., television and radio advertisements) and nutrition education programs (e.g., community-level educational outreach) to enhance people’s awareness—and shift perceptions—of healthy eating, which resulted in a significant increase in the consumption of fruits and vegetables for the intervention group compared to the control group.42 A previous study has shown that a 10 % improvement in the influence of positive social norms could be more effective in increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables compared to price-based strategies such as taxing unhealthy food and subsidizing healthy food.28 Thus, in our baseline simulation experiments, we assumed that the simulated intervention improved the influence of positive social norms by 10 %. We also conducted sensitivity analyses by varying the effectiveness of the intervention.

Limitations

Like all simulation models, our agent-based model is a simplification of the real world and, thus, has limitations that need to be fully understood and discussed before it is used to inform policy-making. First, we assumed that an individual’s health belief and taste preferences were only influenced by his/her peers within his/her neighborhood. Research has shown that internet-based communities increasingly influence individual behaviors but we are unable to capture this potentially important feature in our current agent-based model.43

Second, our neighborhood food environment data excluded several types of food outlets, such as farmers markets, small grocery stores, and convenience stores, because we did not have such data available. However, our current sets of healthy and less healthy food outlets provide most dietary needs of a population and, thereby, can be used to broadly describe the food environment in a given neighborhood.

Third, we did not directly consider the impact of other demographic characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity, income level, marital status) due to a lack of these data. However, the equations for dietary choices were derived from nationally representative data from the Food Attitudes and Behaviors Survey and other published studies and included other variables that are likely to be highly correlated with socioeconomic status such as the level of education.28,30–33 Model validation was also conducted based on neighborhood data estimated from the NYC CHS.

Finally, we made several simplifying assumptions regarding individual behaviors and interactions. For example, we assumed that individuals behave in a conventional manner in terms of how they are influenced by their peers (e.g., individuals put more weight on their own habits than on the habits of others when making decisions). In addition, we assumed that individuals did not change their location of residence throughout the simulation period of 3 years.

Results

Table 1 presents population characteristics for the eight selected neighborhoods—Riverdale, the South Bronx, Greenpoint, Brooklyn Heights, the Upper East Side, Inwood, Forest Hills, and the Rockaway—that have the highest and lowest fruit and vegetable consumption levels for the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens boroughs of NYC. There is substantial variation in demographic characteristics across different neighborhoods. Riverdale has a relatively older population, with 39 % of the population 55 years of age or older, while only 22 % of the population in Greenpoint is 55 years of age or older. The proportion of women in the neighborhood population ranges from 48 to 57 % in these eight selected neighborhoods. For educational attainment, 39 % of the population in the South Bronx did not have a high school degree compared to only about 3 %in the Upper East Side.

TABLE 1.

Fruit and Vegetable Consumption in Selected New York City Neighborhoods

| NYC boroughs | Bronx | Brooklyn | Manhattan | Queens | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhoods | Riverdale | South Bronx | Greenpoint | Heights | Upper East Side | Inwood | Forest Hills | Rockaway |

| Number of adults | 73,413 | 384,008 | 241,362 | 99,473 | 320,906 | 199,528 | 199,111 | 84,281 |

| Age (%) | ||||||||

| 18–34 | 29 | 39 | 50 | 38 | 39 | 38 | 30 | 31 |

| 35–54 | 32 | 38 | 29 | 36 | 29 | 34 | 36 | 36 |

| 55 and older | 39 | 24 | 22 | 26 | 32 | 28 | 33 | 34 |

| Sex (%) | ||||||||

| Female | 56 | 48 | 51 | 57 | 56 | 52 | 53 | 55 |

| Education (%) | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 17 | 39 | 17 | 20 | 3 | 30 | 13 | 22 |

| High school | 20 | 27 | 20 | 29 | 7 | 19 | 26 | 27 |

| Some college | 22 | 23 | 19 | 24 | 11 | 20 | 23 | 25 |

| College and above | 41 | 11 | 44 | 27 | 79 | 31 | 37 | 25 |

| Number of food retailers | ||||||||

| Limited service restaurant | 63 | 360 | 125 | 234 | 80 | 163 | 191 | 46 |

| Full-service restaurant | 58 | 196 | 235 | 162 | 90 | 154 | 203 | 37 |

| Supermarkets | 53 | 619 | 159 | 314 | 33 | 255 | 202 | 59 |

| Fruit and vegetable markets | 2 | 15 | 14 | 26 | 3 | 4 | 16 | 2 |

| Consumption of fruits and vegetables (%) | ||||||||

| Community health survey | 67 | 54 | 74 | 55 | 81 | 61 | 75 | 60 |

| Model simulation | 68 | 55 | 73 | 58 | 82 | 59 | 75 | 60 |

Consumption of fruit and vegetables was measured by the proportion of the population who consume two or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day within a neighborhood. In each of the NYC boroughs, the neighborhood with the highest fruit and vegetable consumption level (Bronx: Kingsbridge–Riverdale; Brooklyn: Greenpoint; Manhattan: Upper East Side–Gramerey, and Queens: Ridgewood–Forest Hills) and the neighborhood with the lowest consumption level (Bronx: South Bronx; Brooklyn: Heights; Manhattan: Inwood, and Queens: Rockaway) were selected for presentation

Table 1 also compares the dietary behaviors for the eight selected neighborhoods based on data from the NYC CHS and the statistics with simulated results from a baseline (i.e., no intervention) simulation. Data from the NYC CHS demonstrate large differences in healthy dietary behaviors across all the different neighborhoods. For instance, 81 % of the population in the Upper East Side in Manhattan consumed at least two servings of fruits and vegetables per day; in comparison, only 54 % of the population in the South Bronx and 55 % of the population in Brooklyn Heights consumed at least two servings of fruits and vegetables per day. Also, note that the actual (CHS-derived) and simulated consumption of fruits and vegetables per day reported at the bottom of Table 1 are virtually identical in most neighborhoods. This strongly supports the predictive ability and validity of our model.

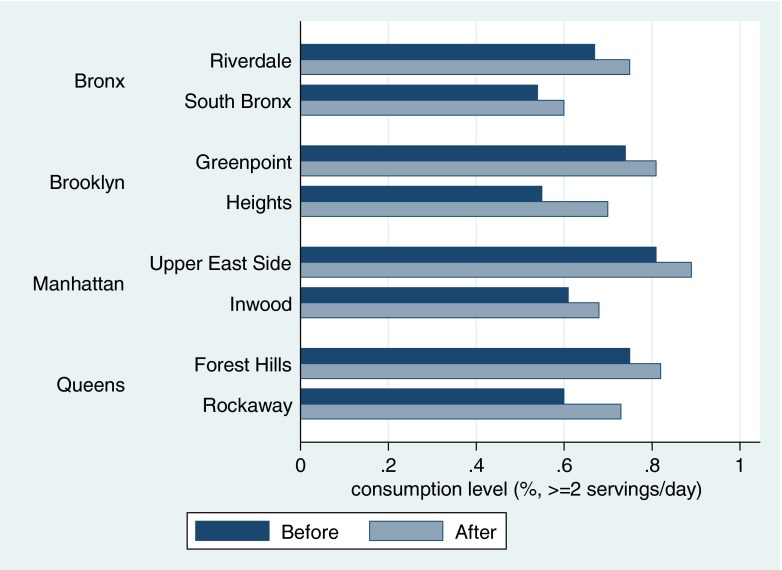

Compared to no intervention, the hypothetical mass media and nutrition education campaign significantly increased the consumption of fruits and vegetables for the eight selected neighborhoods in NYC (Fig. 1). For neighborhoods in the Bronx, the proportion of the population who ate at least two servings of fruits and vegetables a day after the intervention increased from 68.13 to 75.12 % in Riverdale and from 54.74 to 60.4 % in the South Bronx. In Brooklyn, the proportion increased from 73.13 to 80.62 % in Greenpoint and from 57.65 to 70.26 % in Brooklyn Heights. In Manhattan, the proportion increased from 82.44 to 88.95 % on the Upper East Side and from 59.36 to 68.33 % in Inwood. In Queens, the proportion increased from 75.13 to 81.99 % in Forest Hills and from 59.52 to 73.46 % in the Rockaway.

FIG. 1.

Fruit and vegetable consumption before and after policy simulation in selected New York City neighborhoods. Source: Neighborhood-level consumption before the intervention was based on authors’ analysis of data from the NYC Community Health Survey. Consumption estimates after the intervention were based on model simulation. Notes: Consumption of fruits and vegetables was measured by the proportion of the population who consume two or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day within a neighborhood.

Among the 34 UHF neighborhoods, the increase in the proportion of the population who ate two or more servings of fruit and vegetables a day after the hypothetical intervention ranged from 2.68 to 13.94 %. Because there is uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of the mass media and nutrition education campaign in changing people’s perceptions of social norms, we also conducted sensitivity analyses by simulating another set of hypothetical interventions that were less effective in the sense that they strengthened positive social norms by 5 % instead of 10 %. Strengthening social norms by 5 % results in increases in the proportion of the population who ate two or more servings of fruits and vegetables a day that fell between 0.58 and 8.97 % across all the 34 neighborhoods studied (a full set of simulation results and sensitivity analyses are available upon request to the authors).

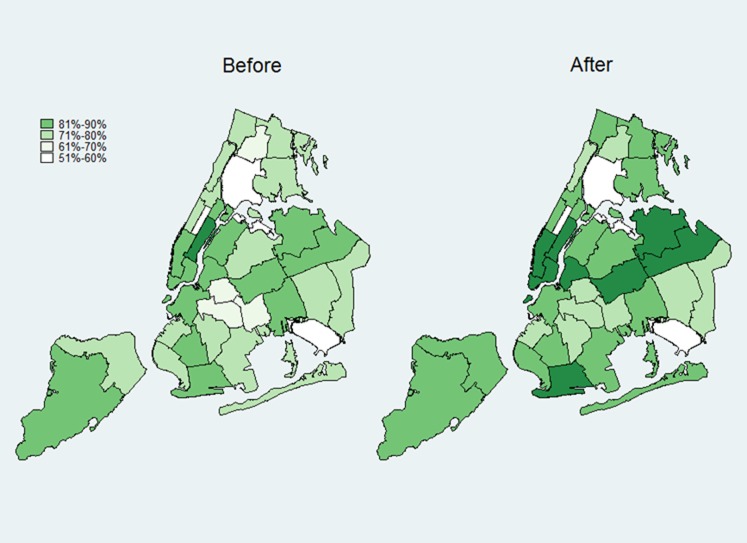

Figure 2 provides a geographic and visual representation of the differences in dietary patterns across different neighborhoods. The maps show that there are substantial differences in the consumption of fruits and vegetables across different neighborhoods in NYC. In many parts of the Bronx and Brooklyn, large segments of the population have a very low intake of fruits and vegetables per day. Our results show how a mass media and nutrition education campaign—by enhancing positive social norms around the consumption of fruits and vegetables—may change the landscape of healthy dietary behaviors for people in NYC.

FIG. 2.

Impact of the proposed mass media and nutrition education campaign on fruit and vegetable consumption in New York City—before and after policy simulation. Source: Neighborhood-level consumption before the intervention was based on authors’ analysis of data from the NYC Community Health Survey. Consumption estimates after the intervention were based on simulation of the proposed intervention. Notes: Consumption of fruits and vegetables was measured by the proportion of the population who consume two or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day within a neighborhood.

Using linear regression analysis, we also evaluated the association between population characteristics and changes in fruit and vegetable consumption to identify important factors that may drive the variability in the effectiveness of the hypothetical mass media and nutrition education campaign across different neighborhoods in NYC. We found that the simulated intervention had a greater impact in the neighborhoods with a higher percentage of women (P < 0.01). In addition, we found that the intervention was less effective at increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables in neighborhoods with a relatively high proportion of the population without a high school diploma (P = 0.05).

Discussion

Social norms play an important role in forming individual behaviors, especially when it comes to activities that impact obesity such as food consumption and exercise.27,44 The marketing of unhealthy food has been criticized for having a negative impact on dietary behaviors and being an important contributor to the rise of obesity.20 However, little research has examined the potential benefits of interventions targeting social norms on healthy eating across heterogeneous neighborhoods, which may help alleviate the health, social, and economic burden of obesity and other chronic health conditions in disadvantaged communities. This research gap may be due in part to a lack of evidence regarding the impact of such interventions on dietary behaviors. Research in this area is limited by the fact that many of the currently available statistical models do not fully capture complex population interactions and the impact of social influences.

We use a validated agent-based model to assess how a hypothetical mass media and nutrition education campaign at the neighborhood level may be related to the consumption of fruits and vegetables. Previous empirical studies have provided clear evidence about the main factors that drive and shape dietary behaviors. Our model, built upon a synthesis of the relevant evidence and a multilevel theory of population health focused on habit formation, provides policymakers with a tool to evaluate the potential impact of a neighborhood-level intervention before its implementation in the real world.28,29 In particular, we found that if a mass media and nutrition education campaign can successfully improve the influence of positive social norms regarding dietary behaviors in a social network by 10 %, then this strategy can potentially increase the proportion of the population consuming at least two servings of fruits and vegetables daily by 2.68 to 13.94 percentage points across different NYC neighborhoods. We also found that even modest changes in the influence of positive social norms (e.g., a 5 % improvement) can lead to increases in the daily consumption of fruits and vegetables (an average of 4 % across all 34 neighborhoods studied).

The impact of the hypothetical mass media and nutrition education campaign in our simulation exercise varied substantially across different neighborhoods in NYC. More specifically, we found that the effectiveness of the simulated intervention in a neighborhood is associated with factors such as gender as well as the educational composition of the neighborhood. The former result may be driven by gender differences in healthy diet beliefs—with women being more likely to eat fruits and vegetables than men45—while the latter finding may be related to the sensitivity of eating behaviors to cognitive overload.29 That is, in neighborhoods with a high proportion of residents with lower levels of education, residents may have competing priorities (e.g., housing insecurity, safety) that may result in poorer food consumption choices and a higher sensitivity to unhealthy food advertising.46 Moreover, even if residents with lower levels of education in a given neighborhood are influenced by mass media and nutrition education campaigns to the same extent as everyone else, other factors such as the sensitivity of individuals to food prices and living in a neighborhood with poor access to healthy food may result in a lower consumption of fruits and vegetables in these neighborhoods.

While extensive sensitivity analysis is needed to confirm our findings with different sets of model parameters and assumptions, our results have demonstrated consistency with existing empirical studies and may have important policy implications. As most of the literature shows the harmful impact of unhealthy food marketing, which dominates the food market, countervailing forces working against it that rely on investing in mass media campaigns and community-based nutrition education programs may be needed if one hopes to reduce the harmful effects of unhealthy food marketing. Another important issue is that interventions focused on social norms are likely to have a marked differential impact across neighborhoods; in our model results, the proposed health campaign would need to be more intense in neighborhoods characterized by a relatively high proportion of male residents as well as in neighborhoods with a larger proportion of residents without a high school degree. As such, combining this intervention with other policies such as healthy food subsidies and/or extensive rezoning of the local food environment may be necessary to have a meaningful impact on healthy food consumption in these vulnerable communities. Multilevel interventions are likely to be necessary in disadvantaged communities to change behaviors, shift social norms, and, ultimately, impact population health.

Conclusion

Well-designed, validated simulation models have the potential to provide insights on the impact of an intervention before it is implemented and shed light on the important neighborhood factors that may affect the efficacy of a given intervention. Our simulation results suggest that carefully designed mass media and nutrition education campaigns may be an effective way to increase the consumption of fruits and vegetables in NYC but its effects are likely to vary substantially across neighborhoods—with a lower effectiveness in neighborhoods characterized by lower levels of education and a higher proportion of men. Dietary behaviors may be more difficult to change for individuals living in neighborhoods with competing priorities and fewer resources. Further research is needed to precisely understand the relevant mechanisms underlying this finding.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/trs916/en/gsfao_introduction.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2016.

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005.; 2005. http://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/clc/1762874. Accessed 27 Sept 2015.

- 3.Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Hercberg S, Dallongeville J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Nutr. 2006;136(10):2588–2593. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montonen J, Knekt P, Härkänen T, et al. Dietary patterns and the incidence of type 2 diabetes. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(3):219–227. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein LH, Gordy CC, Raynor HA, Beddome M, Kilanowski CK, Paluch R. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat and sugar intake in families at risk for childhood obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9(3):171–178. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daviglus ML, Liu K, Pirzada A, et al. Relationship of fruit and vegetable consumption in middle-aged men to medicare expenditures in older age: the Chicago Western Electric Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(11):1735–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanck HM, Gillespie C, Kimmons JE, Seymour JD, Serdula MK. Trends in fruit and vegetable consumption among US men and women, 1994–2005. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(2). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2396974/. Accessed 27 Sept 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Casagrande SS, Wang Y, Anderson C, Gary TL. Have Americans increased their fruit and vegetable intake?: the trends between 1988 and 2002. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jack D, Neckerman K, Schwartz-Soicher O, et al. Socio-economic status, neighbourhood food environments and consumption of fruits and vegetables in New York City. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(07):1197–1205. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012005642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon C, Purciel-Hill M, Ghai NR, Kaufman L, Graham R, Van Wye G. Measuring food deserts in New York City’s low-income neighborhoods. Health Place. 2011;17(2):696–700. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larson N, Story M. Barriers to equity in nutritional health for US children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Curr Nutr Rep. 2015;4(1):102–110. doi: 10.1007/s13668-014-0116-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snyder LB, Hamilton MA, Mitchell EW, Kiwanuka-Tondo J, Fleming-Milici F, Proctor D. A meta-analysis of the effect of mediated health communication campaigns on behavior change in the United States. J Health Commun. 2004;9(S1):71–96. doi: 10.1080/10810730490271548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet. 2010;376(9748):1261–1271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris JL, Bargh JA, Brownell KD. Priming effects of television food advertising on eating behavior. Health Psychol. 2009; 28(4): 404–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Yun D, Silk KJ. Social norms, self-identity, and attention to social comparison information in the context of exercise and healthy diet behavior. Health Commun. 2011;26(3):275–285. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.549814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon HG, Scully ML, Wakefield MA, White VM, Crawford DA. The effects of television advertisements for junk food versus nutritious food on children’s food attitudes and preferences. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(7):1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerbner G, Gross L, Morgan M, Signorielli N. Growing up with television: the cultivation perspective. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1994. http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1994-97177-002. Accessed 19 Oct 2015.

- 18.Gantz W, Schwartz N, Angelini JR, Rideout V. Food for thought: television food advertising to children in the United States. Menlo Park, California: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2007.

- 19.Scully M, Wakefield M, Niven P, et al. Association between food marketing exposure and adolescents’ food choices and eating behaviors. Appetite. 2012;58(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmerman FJ. Using marketing muscle to sell fat: the rise of obesity in the modern economy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:285–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090810-182502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot. 2005;19(5):330–333. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morland K, Wing S, Roux AD. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents’ diets: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1761–1768. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.11.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rose D, Richards R. Food store access and household fruit and vegetable use among participants in the US Food Stamp Program. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(08):1081–1088. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zenk SN, Lachance LL, Schulz AJ, Mentz G, Kannan S, Ridella W. Neighborhood retail food environment and fruit and vegetable intake in a multiethnic urban population. Am J Health Promot. 2009;23(4):255–264. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.071204127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izumi BT, Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Mentz GB, Wilson C. Associations between neighborhood availability and individual consumption of dark-green and orange vegetables among ethnically diverse adults in Detroit. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(2):274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manski CF. Identification of endogenous social effects: the reflection problem. Rev Econ Stud. 1993;60(3):531–542. doi: 10.2307/2298123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.VanderWeele TJ. Sensitivity analysis for contagion effects in social networks. Sociol Methods Res. 2011;40(2):240–255. doi: 10.1177/0049124111404821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang D, Giabbanelli PJ, Arah OA, Zimmerman FJ. Impact of different policies on unhealthy dietary behaviors in an urban adult population: an agent-based simulation model. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):1217–1222. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmerman FJ. Habit, custom, and power: a multi-level theory of population health. Soc Sci Med. 2013;80:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Cancer Institute. Food Attitudes and Behaviors Survey. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/fab/. Accessed 25 Sept 2015.

- 31.Powell LM, Auld MC, Chaloupka FJ, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Access to fast food and food prices: relationship with fruit and vegetable consumption and overweight among adolescents. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res. 2007;17:23–48. doi: 10.1016/S0731-2199(06)17002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beydoun MA, Powell LM, Wang Y. The association of fast food, fruit and vegetable prices with dietary intakes among US adults: is there modification by family income? Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(11):2218–2229. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore LV, Roux AVD, Nettleton JA, Jacobs DR, Franco M. Fast-food consumption, diet quality, and neighborhood exposure to fast food the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2009; 170(1): 29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.United Hospital Fund. NYC UHF 34 Neighborhoods. http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/tracking/uhf34.pdf. Accessed 24 Sept 2015.

- 35.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. New York City Community Health Survey (CHS), 2010. http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/data/chs-data.shtml. Accessed 24 Sept 2015.

- 36.Eubank S, Guclu H, Kumar VA, et al. Modelling disease outbreaks in realistic urban social networks. Nature. 2004;429(6988):180–184. doi: 10.1038/nature02541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luke DA, Harris JK. Network analysis in public health: history, methods, and applications. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:69–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watts DJ, Strogatz SH. Collective dynamics of “small-world” networks. Nature. 1998;393(6684):440–442. doi: 10.1038/30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giabbanelli PJ, Alimadad A, Dabbaghian V, Finegood DT. Modeling the influence of social networks and environment on energy balance and obesity. J Comput Sci. 2012;3(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jocs.2012.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US Census Bureau. 2010 ZIP Code Business Patterns (ZBP). http://www.census.gov/econ/cbp/. Accessed 25 Sept 2015.

- 41.Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in stores (NEMS-S): development and evaluation. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Backman DR, Gonzaga GC. Media, festival, farmers/flea markets and grocery store interventions lead to improved fruit and vegetable consumption for California Latinos. Oakland, CA: California Department of Health Services, Public Health Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centola D. The spread of behavior in an online social network experiment. Science. 2010;329(5996):1194–1197. doi: 10.1126/science.1185231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A, Nillapun M, Jonwutiwes K, Bellisie F. Gender differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27(2):107–116. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zimmerman FJ, Shimoga SV. The effects of food advertising and cognitive load on food choices. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):342. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]