Abstract

BACKGROUND

While Electronic Medical Record (EMR) use has increased dramatically, the EMR’s impact on the patient–doctor relationship remains unclear. This systematic literature review sought to understand the impact of EMR use on patient–doctor relationships and communication.

METHODS

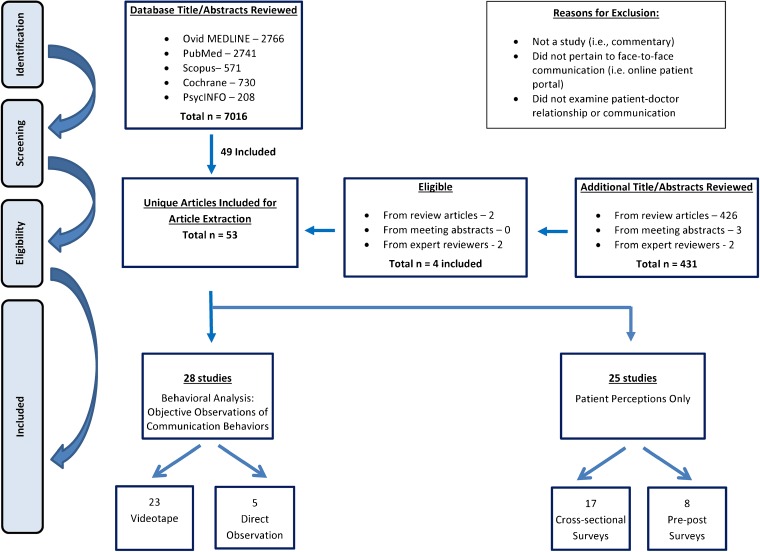

Parallel searches in Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, reference review of prior systematic reviews, meeting abstract reviews, and expert reviews from August 2013 to March 2015 were conducted. Medical Subject Heading terms related to EMR use were combined with keyword terms identifying face-to-face patient–doctor communication. English language observational or interventional studies (1995–2015) were included. Studies examining physician attitudes only were excluded. Structured data extraction compared study population, design, data collection method, and outcomes.

RESULTS

Fifty-three of 7445 studies reviewed met inclusion criteria. Included studies used behavioral analysis (28) to objectively measure communication behaviors using video or direct observation and pre-post or cross-sectional surveys to examine patient perceptions (25). Objective studies reported EMR communication behaviors that were both potentially negative (i.e., interrupted speech, low rates of screen sharing) and positive (i.e., facilitating questions). Studies examining overall patient perceptions of satisfaction, communication or the patient–doctor relationship (n = 22) reported no change with EMR use (16); a positive impact (5) or showed mixed results (1). Study quality was not assessable. Small sample sizes limited generalizability. Publication bias may limit findings.

DISCUSSION

Despite objective evidence that EMR use may negatively impact patient–doctor communication, studies examining patient perceptions found no change in patient satisfaction or patient–doctor communication. Therefore, our findings should encourage providers to adopt the EMR as a communication tool. Future research is needed to better understand how to enhance patient–doctor- EMR communication. This research should correlate observed physician behavior to patient satisfaction, focus on physician communication skills training, and explore inpatient experiences.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3582-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: electronic medical records, EMR, patient–doctor relationship, communication

INTRODUCTION

As physicians increasingly integrate the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) into medical practice, it is important to understand its impact on the patient–doctor communication dynamic. Unfortunately, concerns have been raised over physicians who pay more attention to the “iPatient” on the computer screen than to the real patient during a clinical interaction.1

Leading primary care physician organizations issued the Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) in February 2007, a model that affirms that patient satisfaction with their doctor is an important marker in health care,2 and that patient compliance,3 health outcomes,4 – 6 perceptions of physician competence,7 – 9 and incidence of malpractice suits10 are all closely related to the doctor’s interpersonal skills and quality of the patient–doctor relationship.

While benefits of computerization in health care are well described,11 important drawbacks exist. For instance, some studies show EMR use can prevent doctors from focusing on patients, impede communication, and be detrimental to the patient–doctor relationship.12 – 15 In order to provide patient-centered care in the digital age, it is critical to understand how EMR use impacts the quality of communication and the patient–doctor relationship.

Two prior systematic reviews have examined the impact of EMR use on patient–doctor communication; however, both had limitations impeding application to current clinical practice.16 , 17 First, due to limited search terminology, publication sources and minimal inclusion of international or inpatient studies, the scope of literature reviewed limits its inclusivity. Second, the studies lack results past 2012, which is prior to increased meaningful use participation, and dates many of the findings. To provide a more comprehensive representation of the current literature, the aims of this systematic literature review were to examine the impact of EMR use on the patient–doctor relationship and communication with a focus on patient perspectives and to identify future directions for study.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

We conducted an electronic systematic search of the English literature in Ovid MEDLINE from 1995 to 2015 by exploring Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and keywords related to technology, communication, and relationship terminology in consultation with a biomedical librarian (DW). Given the heterogeneity and lack of standardized terms or MeSH headings used to describe the various types of technologies used in clinical care, additional terms were included (Appendix available online). Only studies or systematic reviews were included; editorials and commentaries were excluded.

We conducted parallel searches in PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library. In addition, we examined references of prior review articles16 – 26 and had two independent expert reviewers evaluate the results to ensure key articles were included. To explore publication bias, we reviewed meeting abstracts from two previous years of Society of General Internal Medicine, American Academy of Family Physicians and International Conference on Communication in Healthcare and European Association of Communication in Healthcare conferences for studies that may not have been published.

Inclusion criteria included studies related to EMR use, the patient–doctor relationship, and face-to-face communication. We included all study designs, all patient populations, and international studies. We excluded studies that reported only physician attitudes and perceptions, as well as articles that did not pertain to face-to-face patient–doctor communication (i.e., patient portals and remote EMR access).

Study Selection

Following the initial search, duplicates were eliminated. For the title and abstract review, each article was independently reviewed for inclusion by three co-authors (ML, SI, ANA). Articles were secondarily reviewed by two senior authors (LAA, WWL). For any titles or abstracts that were unclear, authors erred on the side of including for full review.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

To ensure consistent article extraction, all reviewers participated in a training process. Ten articles were randomly selected and reviewed by three title abstraction reviewers (LAA, WWL, VGP) to ensure that training was successful and definitions were applied appropriately. All discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Following training, all articles were extracted onto a standard extraction form focused on identifying the following for each study: physician type and characteristics (position such as faculty or residents, age, sex, specialty), patient type and demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), study design (observational, RCT, single or pre-post survey), setting (inpatient, outpatient, academic, nonacademic, practice type), recruitment methods, study aims, primary and secondary outcomes, identified barriers & facilitators to patient–doctor communication in the setting of technology use, study strengths and limitations. The validated Downs and Black (DB) checklist27 was going to be used to assess study quality and bias; however, since very few studies were interventional by design, this was not feasible.

Funding for this review was made possible from a grant from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation Research Institute Call for Reviews of Research on Humanistic Healthcare. Funding did not influence our study design, conduct or reporting.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Authors systematically examined studies qualitatively by comparing the study population, design and outcomes. Studies were sub-divided according to method of data collection. A structured data extraction table was created to facilitate collection of these key elements. Articles not meeting inclusion criteria were excluded. Added to this were studies meeting inclusion criteria identified from reference mining systematic review articles, expert opinion, and review of conference abstracts from unpublished studies.

Our review conforms to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards.28 Our systematic review did not meet guidelines for submission to a systematic review protocol registry nor did it facilitate a meta analysis due to the varied interventions, methodology and outcomes, reported in our included studies.

RESULTS

Among 7445 total articles identified, 53 were eligible for review (Fig. 1, Tables 1, 2, and 3). Just over half (n = 28) objectively measured communication behaviors using videotaped or direct observation of clinical encounters and 25 examined patient perceptions by survey or interview. Seven studies examined both patient perceptions and observed behaviors.30 , 31 , 43 , 44 , 48 , 49 , 55 Only two studies were interventional in nature.61 , 70 Forty-seven of the 53 studies were published after the year 2000, and 19 (35.8 %) were published since 2011. Only nine studies reported on both pre- and post-EMR implementation findings,2 , 12 , 49 , 56 – 61 of which only one included both patient perceptions and objective behavioral analysis.49

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Table 1.

Behavioral Analysis Studies (n = 28)

| Author | Setting | Population | Design & outcome measure | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greatbatch29

1995 |

One inner-city general practice (Liverpool, UK) | - 4 doctors - 200 patients (100 pre- & 100 post-EMR) |

Video pre- & post-EMR to examine changes in interpersonal interactions | - Increased doctor computer preoccupation (i.e., pausing mid-sentence to attend to the computer) - Patients synchronized speech with typing pauses to avoid interrupting computer activity |

| Als30

1996 |

Unknown number of urban & rural general practice (GP) offices (Aarhus, Denmark) | - 5 GPs - 39 patients observed, 12 interviewed |

Video & patient interviews to identify desktop use patterns, describe patient perceptions of the computer | - Characterized speech of doctor (pauses, short responses) and patients (synchronized speech with pauses in doctor’s work) - 10 % of patients invited to look at the screen; when done, increased patient perception of understanding |

| Safran31

1998 |

One academic-affiliated outpatient primary care unit (Massachusetts, USA) | - 12 doctors - Patient n unknown |

Video & direct observation, semi-structured patient interviews to examine patient attitudes to effects of EMR | - No relationship between time doctor spent with computer and patient satisfaction - No patient report of computer interfering with patient–provider interactions |

| Makoul32

2001 |

One academic urban general internal medicine faculty practice (Illinois, USA) | - 3 doctors use EMR, 3 doctors use paper - 204 patients |

Video, provider questionnaire & medical record review to assess patient–doctor communication patterns associated with outpatient EMR use. | - EMR doctors more actively clarified information and encouraged questions - Trends that EMR doctors are less active outlining patient agenda and exploring psychosocial aspects |

| Booth33

2002 |

Unknown number of General Practice (GP) offices (Newcastle, UK) | - Doctor n unknown - Patient n unknown |

Video to identify communication skills that enable maintenance of rapport & computer use during clinical encounter | - Doctors prefer typing when patient is not watching - Wide variation in doctors sharing screen with patients - Doctors appear unsuccessful multitasking complex computer interactions with attention to patient |

| Booth34

2004 |

Two GP offices (Northumberland &Yorkshire, UK) | - 10 doctors - 10 patients |

Video to define skills that enable effective computer use in the clinical encounter | - More successful communication skills included signposting computer use, cues they are listening, facing patient, cessation of typing when patients speak |

| Arar35

2005 |

One Veterans’ Administration (VA) internal medicine clinic (Texas, USA) | - 6 doctors - 50 patients |

Video to assess EMR role in content and process of patient–doctor medication discussions | - EMR facilitated medication communication - EMR clarified and expanded medication discussion |

| Frankel36

2005 |

One primary care clinic (USA) | - 6 doctors - 54 patients |

Video pre- & post-EMR introduction to identify communication impact themes | - Introduction of exam-room computers affected clinician–patient communication in four domains; visit organization, verbal & non-verbal behavior, computer navigation & mastery, spatial room organization. - Baseline physician communication behaviors amplified with EMR |

| Margalit37

2006 |

Three academic primary care (adult and pediatric) clinics (Haifa, Israel) | - 3 doctors - 2 faculty, 1 resident - 30 patients |

Video to describe the extent of computer use & impact on a researcher - assigned patient-centered communication (PCC) score |

- Doctor spent 35–42 % looking at screen, 24 % of visits demonstrated heavy keyboarding - PCC score negatively correlated with screen gaze and keyboarding |

| Ventres15

2006 |

Four primary care clinics (Pacific Northwest, USA) | - 6 doctors - 52 patients interviewed, 29 observed |

Video & patient interviews to identify factors influencing doctor EMR with patients | - Factors fall into four thematic domains: EMR impact on spatial interaction, perceptions of EMR, provider proficiency with and patient understanding of EMR use, technological forces influencing doctor EMR use |

| McGrath38

2007 |

One Veterans’ Administration internal medicine clinic (Southwest USA) | - 6 doctors - 50 patients |

Video to identify dimensions of non-verbal physician behavior | - EMR positions facilitating unobstructed patient–doctor visual field most conducive to communication - Breakpoints from EMR use allowed doctors to engage in eye contact, head nodding and verbal utterances |

| Chan39

2008 |

Three academic adult GP training practices in one large health center (Belfast, Ireland) | - 10 doctors - 100 patients |

Video to determine computer use differences in clinical encounters with/without psychological components | - Three styles of doctor EMR use; at the end to summarize encounters, continuous users, and minimal users - Psychological encounters were longer with half as much doctor EMR use |

| Johnson40

2008 |

One academic urban hospital-based pediatric resident clinic (location unknown) | - 59 residents - 149 caregivers pre- & 94 post-ClicTate |

Video pre- & post-ClicTate (electronic visit summary software) introduction to detect changes in questioning style and patient-centeredness of communication | - Significantly greater open-ended questions, more partnership strategies, reinforcing statements and overall more patient-centered interaction post-ClicTate |

| Pearce41

2008 |

Unknown number of GP clinics (Melbourne, Australia) | - 20 doctors - 141 patients |

Video to describe patient–doctor-computer relationship during the opening of visit. | - Doctor, patient or computer encounters start differently, each dictating visit flow - Initial behavior of the patient important in shaping nature of interaction for the rest of the encounter |

| Shachak42

2009 |

Five academic HMO primary care clinics (Israel) | - 5 doctors observed - 69 patients |

Direct observation to describe doctors’ EMR use patterns, influences on communication | - Average doctor screen gaze 25–55 % of visit - One instance EMR used for patient education - Skills to minimize negative impact of EMR: read aloud while typing, eye contact, empathetic language, disengage from computer for important or sensitive issues |

| Noordman43

2010 |

Unknown number of GP offices (Netherland, Denmark) | - 35 doctors - 1170 patients |

Video two points post-EMR & patient surveys to evaluate how doctors use computer during clinical encounters over time, if computer use related to aspects of communication | - Computer use negatively related to some communication aspects (i.e., GP gaze/posture toward patient) - No change in post-EMR relationships between GP computer use and communication |

| Shield44

2010 |

One academic adult family medicine clinic (Rhode Island, USA) | - 26 doctors (13 faculty, 13 residents) - 170 patients |

Direct observation, patient exit interviews to examine EMR effects on patient–doctor communication, behaviors and patient perceptions | - Mix of positive, neutral & negative patient responses - Patient trust in the doctor and security in the patient–doctor relationship appeared to override most patients’ concerns |

| Fiks45

2011 |

12 hospital owned, two urban academic & ten10 suburban non-academic pediatric practices (USA) | - 27 doctors - 529 patients |

Direct observation to characterize EMR use patterns and patient–doctor interaction | - EMR used 27 % of all stages of visit except exam |

| Pearce46

2011 |

Unknown number of GP offices (Australia) | - 20 doctors - 141 patients |

Video to explore patients’ approach to the doctor’s computer use, influence on patient–doctor relationship | - Two patient themes: dealing primarily with doctor, or dealing with both computer and doctor |

| Gibbings-Isaac47

2012 |

11 GP practices (London & Southeast London, UK) | - 12 GPs - 127 patients |

Video to study silent time in the clinical encounter when an EMR is used | - Median 12.3 % silence during encounter, mean duration 15.7 s - 52.4 % of silent periods doctor initiated & terminated |

| Montague48

2012 |

Five adult primary care clinics (Wisconsin, USA) | - 10 doctors - 100 patients |

Video & post-visit patient survey to understand qualities contributing to patient satisfaction with regard to doctor EMR use | - Three styles of doctor EMR use: technology-centered, optimizing (short typing sessions, stopped when patients spoke), human-centered (less typing) - All doctors had high patient trust and EMR use satisfaction ratings |

| Pandit49

2012 |

One academic adult glaucoma subspecialty practice (Maryland, USA) | - Unknown number doctors - 131 patients |

Direct observation pre- & two points post-EMR, and patient survey assess the EMR impact on patient experience, doctor behavior | - Patient visit perceptions largely unchanged - No change in level of personal contact in the patient–doctor relationship or quality of visit |

| Booth50

2013 |

One state hospital & two private practice outpatient rheumatology clinics (Adelaide, Australia) | - 3 doctors - 15 patients |

Video to examine communication when computers used in clinical encounter | - Patients tried to reorient doctor’s attention from computer to themselves, instances where unsuccessful - Doctors use computer to structure conversation - Patients spoke during computer use gaps & stop speaking when doctor oriented to computer |

| Dowell51

2013 |

Eight adult GP practices (Wellington, Australia) | - 28 doctors - 28 patients |

Video to explore how computer influences clinical encounter interactional flow | - Doctor focused on computer 12 % of encounter time - Varied doctor EMR use, most input notes during visit - Multitasking, interrupted conversation flow |

| Kumarap-eli52

2013 |

11 inner city or country GP offices (London, UK) | - 16 GPs - 163 patients |

Video to explore EMR use with regard to room layout, computer use proportion, doctor–patient–computer interactions | - Room layout & doctor actions determined patient ability to view and interact with EMR - Active screen sharing in 8 % of encounters - Eye contact 39 % & computer use 41 % of encounter |

| Montague53

2014 |

Five adult primary care clinics in the Midwest (USA) | - 10 doctors - 100 patients |

Video pre- & post-EMR to examine gaze patterns between patients and doctors | - 30.7 % of visit is spent looking at EMR vs 8.75 % paper - Doctor-initiated gaze patterns are important drivers of interaction between patient, doctor and technology |

| Saleem54

2014 |

Three primary care clinics located in three VA Hospitals (Southeast, Midwest, Northeast, USA) | - 14 doctors - Unknown number of patients |

Direct observation, occasional opportunistic patient interviews to explore variations in, barriers to and facilitators of the use of the EMR in clinical encounters | - Considerable EMR use variation - Instances of using EMR as education tool (i.e., showing test results on the screen) - No EMR use during sensitive topics |

| Street55

2014 |

Four VA adult primary care clinics (California, USA) | - 21 doctors - 125 patients |

Video, patient post-visit satisfaction survey, researcher-determined PCC score to examine EMR influence on quality of communication and patient involvement | - Overall high satisfaction rates, unknown comparison to previous - Less effective PCC with increased doctor EMR gaze &encounter silence |

Table 2.

Patient Perceptions Studies: Pre- and Post-EMR Surveys (n = 8)

| Study authors | Setting | Population sample | Design & outcome measure | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gadd2

2000 |

Six academic physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) outpatient practices (Pennsylvania, USA) | - 17 doctors pre-EMR - 11 doctors post-EMR - 165 patients |

Pre/Post to assess patient satisfaction | - Little EMR impact on satisfaction, most very satisfied with care - Patients denied loss of doctor rapport - Patients paused more when doctor typed, requiring reassurance before continuing to speak |

| Garrison56

2002 |

One academic family medicine clinic (Minnesota, USA) | - 200 patients pre-EMR - 304 patients 3 years post-EMR |

Pre/Post to assess patient views of computer use and patient satisfaction | - No differences in overall satisfaction - 74.6 % thought positively impacted quality of care (QOC) - Most reported positive effect on face-to-face doctor communication |

| Hsu12

2005 |

Adult primary care clinics (Internal medicine & family practice) in 1 freestanding prepaid integrated delivery system - Kaiser Permanente (Oregon, USA) | - 8 doctors - 313 patients |

Pre/Post to assess patient satisfaction and comprehension. Between 2nd and 3rd observation periods, providers received training how to use computers in visit | - 7 month increase in overall patient satisfaction, communication about medical issues, comprehension of decisions made - No significant change in patient satisfaction with communication about psychosocial issues |

| Nagy57

2007 |

All ambulatory care clinics (including pediatrics) in one large Kaiser Permanente medical center (California, USA) | - 184 doctors - 4140 patients pre-EMR - 3980 patients 1–3 months post-EMR - 3177 patients 4–6 months post-EMR |

Pre/Post to assess patient satisfaction. | - No significant differences in patient–doctor communication or patient satisfaction |

| Stewart58

2010 |

One academic psychiatric outpatient clinic (New Mexico, USA) | - 161 patients pre-EMR - 141 patients 4 months post-EMR |

Pre/Post to assess patient satisfaction | - No significant changes in any psychiatric patient satisfaction measures pre- versus post-EMR |

| Rosen59

2011 |

One academic pediatric rheumatology practice (Pennsylvania, USA) | - 99 families pre-EMR - 107 families post-EMR |

Pre/Post to assess family satisfaction | - Greater satisfaction with EMR compared to paper - Higher rating of quality of care post-EMR - EMR increased understanding of child’s health |

| Fairley60

2013 |

One large sexual health outpatient service (Melbourne, Australia) | - 9752 pre-EMR patients - 9145 post-EMR patients |

Pre/Post to assess patient satisfaction | - No difference in patient satisfaction with care |

| Furness61

2013 |

One district general hospital adult inpatient trauma unit (Bath, UK) | - 50 pre-tablet patients - 50 post-tablet patients |

Pre/Post to assess if enabling trauma patients to view radiographic images on a tablet during consultation improved satisfaction, understanding, overall experience | - Post-tablet patients significantly improved involvement in care decisions - 97.8 % felt it helped understand what consultant told them, 95.6 % felt positive effect on their overall hospital experience |

Table 3.

Patient Perceptions Studies: Cross-Sectional Surveys (n = 17)

| Author | Setting | Population | Design& outcome measure | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aydin62

1995 |

One Kaiser Permanente ambulatory adult preventative medicine clinic (California, USA) | - 233 EMR patients - 195 non-EMR patients |

Post-visit survey to assess patient satisfaction with & without CompuHx, an EMR. | - No significant difference in patient satisfaction - Use of CompuHx did not depersonalized the patient–doctor relationship |

| Gonzalez-Heydrich63

2000 |

One academic outpatient pediatric psychiatry clinic (Massachusetts, USA) | - 87 parents | Post-visit survey to assess parental acceptance of EMR | - 100 % noted doctors paid attention to concerns - 90 % reported computer use was a “good thing” - 3 % reported concerns (i.e., provider distraction) |

| Chan64

2003 |

Three academic adult training GP offices (Belfast, Ireland) | - 10 doctors - 102 patients |

Post-visit survey to assess attitudes to doctor computer use during clinical encounters | - 1 % distracted by GP computer use, 3 % felt computer distracted GP - 100 % happy with how GP used computer and that it was useful in the encounter (95 %) |

| Houston65

2003 |

One academic adult internal medicine resident clinic (Alabama, USA) | - 82 residents - 93 patients |

Post-visit survey to assess patient perceptions of handheld PDA use | - 59 % liked idea of a doctor with a PDA in the exam room |

| Weaver66

2003 |

One adult family practice (Ohio, USA) | - 212 patients | Post-visit survey to assess patient perceptions of electronic knowledge coupling (KC) tool use during a clinical encounter | - 28 % felt computer interfered with doctor ability to listen & contributed to less personal attention - 21 % had concerns of doctor over-reliance on technology - Positive points include patient education, increased empowerment to understand condition |

| Callen67

2005 |

One outpatient general practice (Sydney, Australia) | - 77 patients | Post-visit survey to assess patient perceptions of computer use during clinical encounters | - 27 % felt doctor distracted by computer, 25 % uncertain - 66 % felt relationship unaffected by computer - 63 % felt it contributed to better quality of care |

| Freeman68

2007 |

One outpatient specialty headache practice (North Carolina, USA) | - 394 patients | Post-visit survey to assess patient satisfaction and perceptions | - 78 % denied EMR interfered with relationship - 40.8 % feel medical care is better with computer - 14.6 % felt eye contact was less |

| Rouf69

2007 |

One academic VA adult primary care faculty & resident clinic (New York, USA) | - 33 doctors - 155 patients |

Post-visit survey to assess patient satisfaction, quality of care and impact of the computer on patient–doctor relationship. | - 8 % felt EMR interfered with relationship - Residents’ patients more likely to agree the computer adversely affected amount of time doctor spoke to and looked at them |

| Almquist70

2009 |

One academic internal medicine clinic (Minnesota, USA) | - 6 doctors - 65 patients - 30 in standard room, 35 in experimental room |

Patient & care partner post-visit survey after randomization to either standard room favoring doctor EMR use or experimental room designed to favor patient-centered care to determine effect of room redesign on the patient-clinician interaction | - No difference between rooms in patient satisfaction with encounter, mutual respect, or communication quality - Experimental room patients reported clinicians allowed them to review the medical record on the screen, shared information on the screen, and reviewed information on the internet with the patient significantly more than standard room |

| McCord71

2009 |

12 academic community adult family medicine resident & faculty clinics (Ohio, USA) | - 284 doctors - 284 patients |

Single post-visit survey to elicit perceptions regarding doctor use of a PDA in clinic visit | - 73 % note no change to provider communication - 83 % note no change in their relationship - Communication rated more positively when doctor explains why they are using the PDA |

| Lelievre72

2010 |

One academic adult family medicine center (Ontario, Canada) | - 175 patients | Post-visit survey to assess patient satisfaction | - Only a doctor’s attitude toward computer shown to have a positive correlation on patient preference for computer - 61 % note no effect on doctor distraction - 57.1 % thought computer had positive effect on their overall satisfaction, 30.3 % saw no effect |

| Strayer73

2010 |

One academic adult family medicine center (Virginia, USA) | - 96 patients | Post-visit survey to assess patient attitudes toward doctor tablet PCs use | - 98 % felt could speak as easily compared to prior - 84 % denied less personal interaction - Those that thought the interaction was less personal (15 %) tended to be minority patients |

| Kahane74

2011 |

Five academic affiliated family medicine clinics (Ontario, Canada) | - 75 doctors - 153 patients |

Post-visit survey to assess patient confidence in their family doctor and perceptions of quality of care after seeing doctors look up medical information during the clinical encounter. | - 9 % of patients perceived decreased confidence when information source not known - When source known, confidence was lower when patients saw providers use a PDA (27 %) or internet search engine (39 %) |

| Hirsch75

2012 |

Unknown number of adult primary care practices (North Rhine-Westphalia & Hesse, Germany) | - 29 doctors - 192 patients |

Post-visit survey to assess patient attitudes with use of Arriba-lib, an electronic library of decision aids, during their clinical encounter | - 97.4 % of patients satisfied with counseling received, 64.7 % wanted to be counseled with the module again in the future |

| Al Jafar76

2013 |

78 primary adult health care centers (Kuwait) | - 518 patients | Post-visit survey to assess patient satisfaction | - 36 % felt EMR increased trust in doctors, 35 % disagreed - 31 % felt EMR improved the relationship, 34 % disagreed, 35 % uncertain |

| Jarvis77

2013 |

2988 different hospitals eligible to participate in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program (USA) | - Unknown number of patients | Single Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and System (HCAHPS) patient survey in order to evaluate association between advanced EMR use on patient estimated process and experience of care scores | - Hospitals with advanced EMR use showed a 4.2 point higher process of care scores - There was no significant difference in estimated patient experience of care scores by level of advanced EMR use |

| Ratanawo-ngsa78

2013 |

One academically-affiliated internal medicine clinic in a public hospital (California, USA) | 399 patients - 31 % Latino - 17 % Asian - 17 % African American - 18 % White |

Post-visit survey to examine associations of patient race & ethnicity, language and education with perceptions of doctor computer use | - 20 % felt providers listened less carefully because of computer, non-English speakers less likely to endorse this - Most felt the computer helped their provider take better care of them (74 %) with non-English patients recognizing benefits more often |

Study Setting

Thirty-one (58 %) studies were conducted in the US. Most were conducted in an outpatient setting (n = 51, 96 %), with two (4 %) in the inpatient setting. Of outpatient studies, 39 (76 %) were in an adult primary care (i.e., family practice, internal medicine) clinic; only seven (14 %) included pediatric patients or their families. Eight studies (16 %) took place in a specialty clinic. Approximately half (n = 28) were at a single clinic or institution, one-third (n = 19) included multiple sites (range: 2–78), and one examined 2988 unique hospitals.

Twenty of the studies (42 %) were conducted at academic or academically-affiliated training sites; however, only six (26 %) examined outcomes related to residents or their patients.

Behavioral Analysis Outcomes

Of 28 studies15 , 29 – 55 utilizing behavioral analysis to objectively observe communication behaviors, 23 (82 %) analyzed videotaped interactions and five (18 %) used direct observation.42 , 44 , 45 , 49 , 54 An average of 162 patients (range 10–1170) and 15 providers (range 3–59) participated per study, and three studies included resident observations.37 , 40 , 44

Characterizing EMR Communication Behaviors

Six studies quantified EMR use during a clinical encounter, with an average of 32 % of visit time spent using the computer (range 12–55 %).37 , 42 , 45 , 51 – 53 Although many studies reported long periods of silence during the encounter, only one study actually defined it as a percentage of the interaction (12 %, mean duration 15.7 s).47 Studies reported changes in speech style of both providers (i.e., abrupt topic shifts)29 , 30 , 42 , 48 , 51 and patients (i.e., synchronizing speech with typing pauses).29 , 30 , 50 Eight studies described variation in the amount and manner in which the EMR was used.15 , 36 , 39 , 41 , 46 , 48 , 51 , 54 Four studies examined typing behaviors33 , 37 , 42 , 48 and six reported on screen positioning, with only 8–10 % active screen sharing during the visit.29 , 30 , 33 , 37 , 38 , 52 Interestingly, one study noted patients had a more positive attitude towards the EMR when they were shown the screen.30

Provider multitasking was another theme that emerged, highlighting providers were unsuccessful at concentrating on complex computer interactions while attending to the patient simultaneously.29 , 33

There were also instances of communication behaviors that researchers believed promoted communication. Four studies noted that EMR use appeared to facilitate clarification, questions and discussion, as well as more open-ended questions and partnership strategies.32 , 34 , 35 , 40 Specific behaviors that seemed to facilitate a more patient-centered interaction included actively inviting patients to look at the screen and using it as an educational tool (i.e., showing test results), signposting computer use, maintaining eye contact, cessation of computer use when patients spoke about sensitive or important topics, continued verbal and nonverbal cues of listening, and reading aloud while typing.30 , 34 , 38 , 42 , 54 Additionally, being able to make computer use less obvious (i.e., typing softly, continuing to speak while typing) resulted in fewer patient speech pattern modifications.29

Five studies29 , 32 , 36 , 40 , 49 included both a pre- and a post-EMR implementation observation group; however, only two paired findings were to the same physician at both points.29 , 36 Paired observations showed greater doctor preoccupation with computer use and alterations in doctor and patient speech patterns, such as delaying speech until finished with the computer.29 Two studies demonstrated doctors tended to adopt a more active role in clarifying information and encouraging questions when the EMR was used.32 , 40

Correlating EMR Communication Behaviors with Patient Perceptions

While 11 studies29 – 31 , 34 , 37 , 38 , 43 , 44 , 48 , 49 , 55 attempted to correlate objective observations of communication behaviors with patient perceptions of care, only seven of these studies elicited patient perspectives directly.30 , 31 , 43 , 44 , 48 , 49 , 55 The remaining studies used researcher perceptions of the patient perspective as a proxy. Studies noted mixed patient perceptions. An increase in provider screen gaze, keyboarding, silence and closed body posturing negatively impacted communication.43 , 55 However, certain behaviors enabled more successful integration of the EMR into the visit, such as screen sharing that did not obstruct the visual field between doctor and patient.30 Three studies directly examined patient perceptions of change in overall patient–doctor relationship and quality of care or satisfaction overall, and found no significant change as a result of EMR use.31 , 43 , 49 While two studies noted high rates of satisfaction or trust of their doctor, these studies did not report baseline data, thus making it unclear if there was any change in satisfaction related to the introduction of the EMR.48 , 55 Furthermore, two qualitative studies showed a mix of positive, negative and neutral patient responses without quantifying of the effect.30 , 44

Patient Perceptions: Pre- and Post-EMR Surveys

Eight studies used pre- and post-EMR patient surveys as their only method of data collection, with a range of 100 to 18,897 patients responses.2 , 12 , 56 – 61 Five2 , 56 – 58 , 60 studies (63 %), two of which had sample sizes over 10,000, found that most patients reported no change in measures of overall patient satisfaction, communication and the patient–doctor relationship as a result of the introduction of technology into the face-to-face clinical interaction.

Three12 , 59 , 61 studies (38 %) reported largely positive satisfaction with communication and patient–doctor relationship as a result of EMR use. One of these was unique because it was one of only two inpatient studies and it directly enabled patients to interact with the EMR.61 In this study, Furness et al. examined the effect of allowing inpatient trauma patients to view their radiographic images on a tablet with their consultant. After the introduction of tablets, patients perceived significantly more involvement in their care decisions and being given the “right amount of information” about their treatment as compared to before the introduction of tablets.61 Lastly, two studies reported that patients perceived their quality of care as higher with EMRs.56 , 59

Patient Perceptions: Cross-Sectional Surveys

Seventeen studies used single cross-sectional patient surveys as their only method of data collection, with a range of 65–518 patient participants per study. Nine of these examined patient perceptions of physician distraction by the computer, with a range of 3–40 % (mean 18 %) of patients expressing some level of concern.63 , 64 , 66 – 69 , 72 , 76 , 78

Eleven studies examined global perceptions, with eight62 , 67 – 71 , 73 , 77 studies (73 %) reporting no change in overall patient satisfaction, communication or the patient–doctor relationship as a result of the introduction of EMR. One study (9 %) demonstrated equally mixed positive, negative and neutral patient satisfaction,76 and two studies (18 %) demonstrated a majority of positive outcomes.72 , 75 Only one study reported patient-perceived quality-of-care (QOC), with the majority of patients reporting technology contributed to a better QOC.67

The remaining six cross-sectional studies63 – 66 , 74 , 78 (35 %) in this group also examined patient perceptions, but lacked global measures such as overall satisfaction with communication or the patient–doctor relationship. It appears, however, that they contained more positive (i.e., use of the computer was a “good thing”)63 than negative (i.e., the computer interfered with my doctor’s ability to hear my complaints)66 patient comments.

One study used a “patient-centered” spatial arrangement of the room and computer, and found no difference in patient satisfaction or perceptions of communication quality with the ergonomic change.70

Characterizing Positive Deviants

An important but limited number of studies (n = 4) examined increases in patient understanding of their condition as a result of their provider using the EMR in the clinical interaction, demonstrating increased perceptions of empowerment and informed decision-making.12 , 59 , 61 , 66 Also, of the 22 total articles examining impacts of the EMR on overall patient perceptions of satisfaction, communication or the patient–doctor relationship as a result of EMR use, five (23 %) found positive changes and these are important to highlight.12 , 59 , 61 , 72 , 75 Three of these (60 %) were conducted outside of the US in countries in which a Universal Health Care system exists (UK, Canada, Germany).61 , 72 , 75 Two focused on the use of a somewhat novel technology aide; one using a tablet to view radiologic images61 and another using an EMR decision aid,75 both of which resulted in increased satisfaction with the encounter, counseling, and involvement in their care. Of the two US studies, Hsu et al.’s Kaiser study was remarkable in that it was the only study that provided physician training on how to integrate computers into the visit.12 , 59 Although there was a decrease in patient satisfaction after physician training, from 67 % 1 month post-EMR (pre-training) to 63 % 7 months post-EMR (post-training), there was increased overall patient satisfaction 7 months post-EMR introduction compared to baseline.12 Due the observational design of the study, it is unknown whether the changes in satisfaction were related to the training; however, it is an important finding.

Interestingly, a greater percentage of positive studies emanated from the international community, with 43 % (n = 3 of 7 total studies)61 , 72 , 75 noting overall positive changes in satisfaction in communication or the patient–doctor relationship as a result of technology use versus 13 % (n = 2 of 15 total)12 , 59 of US studies.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review of the impact of the EMR on the doctor–patient relationship and communication found while physicians exhibited potentially negative communication behaviors with EMR use (i.e., interrupted patient and doctor speech patterns, increased gaze shifts and episodes of multitasking, and low rates of sharing the computer screen with patients), the majority of studies examining patient perceptions reported no change in overall patient satisfaction, communication, or the patient–doctor relationship. Furthermore, some studies identified instances in which patients felt the EMR facilitated the process of communication, clarification, and discussion as well as some potentially patient-centered communication behaviors. These “best practices” may be taught to providers in order to guide them towards more successful and collaborative EMR use. Given that the majority of studies were conducted in adult primary care clinics, these findings are highly pertinent to adult providers since communication is key to the patient–doctor primary care relationship and patient outcomes.3 – 10 Lack of change in overall patient perceptions may be surprising to clinicians, given accounts of negative provider attitudes to EMR implementation.2 , 65 However, knowing that patient perceptions did not suffer, providers and administrators should not be deterred by fears of its adoption and instead learn to actively use it in a more patient-centered manner.

It is important to reflect on the five of 22 studies that reported positive changes in overall patient satisfaction, communication or the patient–doctor relationship as a result of EMR use. These positive patient perceptions are perhaps reflective of a different culture of EMR use in these settings, and an increased acceptance in other countries or highly integrated healthcare systems. It is possible that improved patient and provider familiarity with the EMR in these environments created a different culture of practice that enabled EMR use in a more patient-centered manner. Comparatively, US patients and physicians are perhaps not as cognizant or experienced in achieving this, as evidenced by the greater positive patient perceptions abroad. Given the tremendous potential of EMR integration for patient education, it is important to highlight best practices in order to maximize EMR use as an educational tool.

It is also worth considering why patient and physician perception discrepancies regarding EMR use exist. Patient satisfaction or their perceived quality of care may be driven by factors other than provider communication behaviors. For example, the EMR may improve clinical efficiency by making it easier for physicians to communicate with other providers, and in turn patients may perceive physician technology use as positive overall. Because the majority of studies were conducted in adult primary care settings, strong patient–doctor relationships may have contributed to patients being more accepting of their doctors being unfamiliar with the EMR at first and slowly becoming facile with the EMR. Additionally, patients may not consciously notice behavior differences as much as trained observers.

This review identifies the need for further study in a variety of areas related to EMR use. Future work should correlate observed physician behavior with direct patient perceptions rather than a trained observer as proxy, in order to identify how to best use the EMR during clinical interactions to engage patients in their care. Objective studies should further explore how to integrate EMR use to enhance patient engagement and communication.

Also, few studies took place in primary care academic settings, which is particularly interesting due to issues around the hidden curriculum and potential negative role-modeling by attendings, given the lack of training on patient-centered EMR use. This highlights the need to study academic settings further, and to develop and implement effective curricula for all providers on how to use the EMR to enhance patient–doctor communication.

In the future, greater attention should be given to studies outside of adult outpatient primary care. Since high levels of continuity may influence patient perceptions of EMR use, studies should specifically focus on inpatient or specialty settings to understand the impact of EMR use in low continuity settings. Also, given the increasing rates of technology adoption by younger “millennial” trainees (i.e., fellows, residents, medical students), further studies should look at how this group may differ from older providers in their EMR use. Lastly, future research should utilize randomized study designs where possible; for example, randomizing providers to EMR training and directly eliciting patient experience regarding technology use and the impact on patient–doctor communication.

Although this systematic review found several significant findings, there are important limitations to note. For instance, while nearly one-third of studies examined patient perceptions, the heterogeneity in the type of questions asked and lack of global measures such as overall satisfaction limited the ability to compare findings within this cohort. Also, analysis of the included studies reveals potential areas where study bias could exist. The majority of studies used direct observation methods, which are a proxy for the patient’s experience and are subject to inter-observer variability when multiple individuals are observing and reporting on behaviors observed. Interviewer bias could also have occurred when those observations were followed by questioning from the study personnel. There was also the potential for publication bias, and while we sought to address this by reviewing abstracts from related meetings, we were not able to review abstracts for all possible related meetings and could only review studies published in English. Another limitation is the paucity of studies documenting both specific observed communication behaviors pre- and post-EMR in addition to eliciting direct patient perceptions. With increasing rates of EMR adoption, it will be harder to conduct such a pre-post EMR study. Also, for those studies where the is no pre-EMR observation, it is quite possible that these providers were at baseline poor communicators, and thus the introduction of the EMR is not to account for the negative behaviors observed, but rather they are reflective of the providers’ poor baseline communication ability.

Reliance on convenience samples of both physician and patient subjects may have contributed to selection bias in both groups, as only one study70 was randomized. Most studies identified had small numbers of physician and patient participants as well as study sites. As such, external validity of the findings and the ability to generalize them to other groups or populations is not known. In addition, because many of the studies were observational in nature, causal inferences could not be made and unmeasured confounders may exist. Lastly, multiple variables contribute to the overall experience of the patient–doctor relationship and communication, and it is quite plausible that some other factor is contributing to the observations and effects seen.

In conclusion, it appears EMR use can improve patient understanding of conditions and treatment plans, and increase sharing and confirmation of medical information. Several studies identify behaviors that appear to facilitate patient-centered communication (i.e., screen sharing, signposting, cessation of typing during sensitive discussions) and future work should adapt these best practices into a curriculum to teach providers how to integrate patient-centered EMR use into their clinical workflow. Medical education targeting the continuum of learners can address this gap in training and help foster humanistic patient–doctor-EMR interactions in the digital age.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 13 kb)

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible by a grant from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation.

Contributors

Our two expert reviewers were Darcy Reed MD, MPH, Associate Professor of Medical Education and Associate Professor of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, and Rich Frankel PhD, Professor of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Associate Director, VA HSR&D Center for Health Information and Communication.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funders

Funding for this review was made possible from a grant from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation Research Institute Call for Reviews of Research on Humanistic Healthcare.

Prior Presentations

The results of our review were presented at the Arnold P. Gold Foundation Research Institute Symposium on Reviews of Research on Humanistic Healthcare, 2 May 2015

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose in relation to the content of this paper. Funding was provided by the Gold Foundation. The Gold Foundation had no role in the conduct of the review, management, analysis or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Verghese A. Culture shock—patient as icon, icon as patient. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(26):2748–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0807461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gadd CS, Penrod LE. Dichotomy between physicians’ and patients’ attitudes regarding EMR use during outpatient encounters. Proc AMIA Symp 2000:275–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Schwenk TL, Evans DL, Laden SK, et al. Treatment outcome and physician–patient communication in primary care patients with chronic, recurrent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1892–901. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halbesleben JR, Rathert C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes; exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manag Rev. 2008;33:29–39. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000304493.87898.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maly RC, Stein JA, Umezawa Y, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in breast cancer outcomes among older patients: effects of physician communication and patient empowerment. Health Psychol. 2008;27:728–36. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, et al. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:213–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen JY, Tao ML, Tisnado D, et al. Impact of physician–patient discussions on patient satisfaction. Med Care. 2008;46:1157–62. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817924bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kating NL, Green DC, Kao AC, et al. How are patients’ specific ambulatory care experiences related to trust, satisfaction, and considering changing physicians? J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:29–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waljee JF, Hu ES, Newman LA, et al. Correlates of patient satisfaction and provider trust after breast-conserving surgery. Cancer. 2008;112:1679–87. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, et al. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118:1126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica W, Roth E, Morton SC, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):742–52. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu J, Huang J, Fung V, et al. Health information technology and physician–patient reactions: impact of computers on communication during outpatient primary care visits. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12:474–80. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyle RJ, Wang N, Anthony D, et al. Computers in the examination room and the electronic health record: physicians’ perceived impact on clinical encounters before and after full installation and implementation. Fam Pract. 2012;5:601–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ventres W, Kooienga S, Marlin R, et al. Clinician style and examination room computers: a video ethnography. Fam Med. 2005;37(4):276–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ventres W, Kooienga S, Vuckovic N, et al. Physicians, patients, and the electronic health record: an ethnographic analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(2):124–31. doi: 10.1370/afm.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kazmi Z. Effects of exam room EHR use on doctor–patient communication: a systematic literature review. Inform Prim Care. 2013;21(1):30–9. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v21i1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shachak A, Reis S. The impact of electronic medical records on patient–doctor communication during consultation: a narrative literature review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(4):641–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duke P, Frankel RM, Reis S. How to integrate the electronic health record and patient-centered communication into the medical visit: a skills-based approach. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):358–65. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.827981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarke MA, et al. Addressing human computer interaction issues of electronic health record in clinical encounters. Design, User Experience, and Usability. Health, Learning, Playing, Cultural, and Cross-Cultural User Experience. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013. 381–390.

- 20.Lau F, Price M, Boyd J, et al. Impact of electronic medical record on physician practice in office settings: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irani JS, Middleton JL, Marfatia R, et al. The use of electronic health records in the exam room and patient satisfaction: a systemic review. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(5):553–62. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.05.080259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J, Luo L, Zhang R, et al. Patient satisfaction with electronic medical/health record: a systematic review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(4):785–91. doi: 10.1111/scs.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell E, Sullivan F. A descriptive feast but an evaluative famine: systematic review of published articles on primary care computing during 1980–97. BMJ. 2001;322(7281):279–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7281.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buntin MB, Burke MF, Hoaglin MC, et al. The benefits of health information technology: a review of the recent literature shows predominantly positive results. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(3):464–71. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holroyd-Leduc JM, Lorenzetti D, Straus SE, et al. The impact of the electronic medical record on structure, process, and outcomes within primary care: a systematic review of the evidence. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(6):732–7. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2010-000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nusbaum NJ. The electronic medical record and patient-centered care. Online J Public Health Inform. 2011;3(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomized and nonrandomized studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–84. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greatbatch D, Heath C, Campion P, et al. How do desk-top computers affect the doctor–patient interaction? Fam Pract. 1995;12(1):32–6. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Als AB. The desk-top computer as a magic box: patterns of behaviour connected with the desk-top computer; GPs’ and patients’ perceptions. Fam Pract. 1997;14(1):17–23. doi: 10.1093/fampra/14.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Safran C, Jones PC, Rind D, et al. Electronic communication and collaboration in a health care practice. Artif Intell Med. 1998;12(2):137–51. doi: 10.1016/S0933-3657(97)00047-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makoul G, Curry RH, Tang PC. The use of electronic medical records: communication patterns in outpatient encounters. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2001;8(6):610–5. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2001.0080610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Booth N, Robinson P. Interference with the patient–doctor relationship--the cultural gap? Lessons from observation. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2002;87:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Booth N, Robinson P, Kohannejad J. Identification of high-quality consultation practice in primary care: the effects of computer use on doctor–patient rapport. Inform Prim Care. 2004;12(2):75–83. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v12i2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arar NH, Wen L, McGrath J, et al. Communicating about medications during primary care outpatient visits: the role of electronic medical records. Inform Prim Care. 2005;13(1):13–22. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v13i1.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frankel R, Altschuler A, George S, et al. Effects of exam-room computing on clinician–patient communication: a longitudinal qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(8):677–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margalit RS, Roter D, Dunevant MA, et al. Electronic medical record use and physician–patient communication: an observational study of Israeli primary care encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(1):134–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGrath JM, Arar NH, Pugh JA. The influence of electronic medical record usage on nonverbal communication in the medical interview. Health Informatics J. 2007;13(2):105–18. doi: 10.1177/1460458207076466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan WS, Stevenson M, McGlade K. Do general practitioners change how they use the computer during consultations with a significant psychological component? Int J Med Inform. 2008;77(8):534–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson KB, Serwint JR, Fagan LA, et al. Computer-based documentation: effects on parent–provider communication during pediatric health maintenance encounters. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):590–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pearce C, Trumble S, Arnold M, et al. Computers in the new consultation: within the first minute. Fam Pract. 2008;25(3):202–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shachak A, Hadas-Dayagi M, Ziv A, et al. Primary care physicians’ use of an electronic medical record system: a cognitive task analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):341–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0892-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noordman J, Verhaak P, van Beljouw I, et al. Consulting room computers and their effect on general practitioner-patient communication. Fam Pract. 2010;27(6):644–51. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shield RR, Goldman RE, Anthony DA, et al. Gradual electronic health record implementation: new insights on physician and patient adaptation. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(4):316–26. doi: 10.1370/afm.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fiks AG, Alessandrini EA, Forrest CB, et al. Electronic medical record use in pediatric primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(1):38–44. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2010.004135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearce C, Arnold M, Phillips C, et al. The patient and the computer in the primary care consultation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(2):138–42. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2010.006486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gibbings-Isaac D, Iqbal M, Tahir MA, Kumarapeli P, et al. The pattern of silent time in the clinical consultation: an observational multichannel video study. Fam Pract. 2012;29(5):616–21. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montague E, Asan O. Considering social ergonomics: the effects of HIT on interpersonal relationships between patients and clinicians. Work. 2012;41(Suppl 1):4479–83. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0748-4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pandit RR, Boland MV. The impact of an electronic health record transition on a glaucoma subspecialty practice. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(4):753–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Booth A, Lecouteur A, Chur-Hansen A. The impact of the desktop computer on rheumatologist-patient consultations. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32(3):391–3. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2140-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dowell A, Stubbe M, Scott-Dowell K, et al. Talking with the alien: interaction with computers in the GP consultation. Aust J Prim Health. 2013;19(4):275–82. doi: 10.1071/PY13036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumarapeli P, de Lusignan S. Using the computer in the clinical consultation; setting the stage, reviewing, recording, and taking actions: multi-channel video study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(e1):e67–75. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Montague E, Asan O. Dynamic modeling of patient and physician eye gaze to understand the effects of electronic health records on doctor–patient communication and attention. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83(3):225–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saleem JJ, Flanagan ME, Russ AL, et al. You and me and the computer makes three: variations in exam room use of the electronic health record. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e147–51. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Street RL, Jr, Liu L, Farber NJ, et al. Provider interaction with the electronic health record: the effects on patient-centered communication in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):315–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garrison GM, Bernard ME. Rasmussen NH. 21st-century health care: the effect of computer use by physicians on patient satisfaction at a family medicine clinic. Fam Med. 2002;34(5):362–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagy VT, Kanter MH. Implementing the electronic medical record in the exam room: the effect on physician–patient communication and patient satisfaction. Perm J. 2007;11(2):21–4. doi: 10.7812/TPP/06-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stewart RF, Kroth PJ, Schuyler M, et al. Do electronic health records affect the patient-psychiatrist relationship? A before & after study of psychiatric outpatients. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosen P, Spalding SJ, Hannon MJ, et al. Parent satisfaction with the electronic medical record in an academic pediatric rheumatology practice. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(2):e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fairley CK, Vodstrcil LA, Huffam S, et al. Evaluation of Electronic Medical Record (EMR) at large urban primary care sexual health centre. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Furness ND, Bradford OJ, Paterson MP. Tablets in trauma: using mobile computing platforms to improve patient understanding and experience. Orthopedics. 2013;36(3):205–8. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20130222-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aydin CE, Rosen PN, Jewell SM, et al. Computers in the examining room: the patient’s perspective. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1995:824–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Gonzalez-Heydrich J, DeMaso DR, Irwin C, et al. Implementation of an electronic medical record system in a pediatric psychopharmacology program. Int J Med Inform. 2000;57(2–3):109–16. doi: 10.1016/S1386-5056(00)00058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan W. McGladeK. Patients’ attitudes to GPs’ use of computers. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(491):490–1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Houston TK, Ray MN, Crawford MA, et al. Patient perceptions of physician use of handheld computers. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003:299–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Weaver RR. Informatics tools and medical communication: Patient perspectives of “knowledge coupling” in primary care. Health Commun. 2003;15(1):59–78. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1501_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Callen JL, Bevis M, McIntosh JH. Patients’ perceptions of general practitioners using computers during the patient–doctor consultation. HIM J. 2005;34(1):8–12. doi: 10.1177/183335830503400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Freeman MC, Taylor AP, Adelman JU. Electronic medical record system in a headache specialty practice: a patient satisfaction survey. Headache. 2009;49(2):212–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.01009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rouf E, Whittle J, Lu N, Schwartz MD. Computers in the exam room: differences in physician–patient interaction may be due to physician experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(1):43–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0112-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Almquist JR, Kelly C, Bromberg J, et al. Consultation room design and the clinical encounter: the space and interaction randomized trial. HERD. 2009;3(1):41–78. doi: 10.1177/193758670900300106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McCord G, Pendleton BF, Schrop SL, et al. Assessing the impact on patient–physician interaction when physicians use personal digital assistants: a Northeastern Ohio Network (NEON) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:353–9. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.04.080056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lelievre S, Schultz K. Does computer use in patient–physician encounters influence patient satisfaction? Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(1):e6–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Strayer SM, Semler MW, Kington ML, et al. Patient attitudes toward physician use of tablet computers in the exam room. Fam Med. 2010;42(9):643–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kahane S. Must we appear to be all-knowing? Patients’ and family physicians’ perspectives on information seeking during consultations. Can Fam Physician. 2001;57:e228–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hirsch O, Keller H, Krones T, et al. Arriba-lib: association of an evidence-based electronic library of decision aids with communication and decision-making in patients and primary care physicians. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2012;10(1):68–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2012.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Al Jafar E. Exploring patient satisfaction before and after electronic health record (EHR) implementation: the Kuwait experience. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2013;10:1c. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jarvis B, Johnson T, Butler P, et al. Assessing the impact of electronic health records as an enabler of hospital quality and patient satisfaction. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1471–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a36cab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ratanawongsa N, Barton JL, Schillinger D, et al. Ethnically diverse patients’ perceptions of clinician computer use in a safety-net clinic. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4):1542–51. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 13 kb)