Abstract

From 2006 to 2011, an outbreak of a particular type of childhood interstitial lung disease occurred in Korea. The condition was intractable and progressed to severe respiratory failure, with a high mortality rate. Moreover, in several familial cases, the disease affected young women and children simultaneously. Epidemiologic, animal, and post-interventional studies identified the cause as inhalation of humidifier disinfectants. Here, we report a 4-year-old girl who suffered from severe progressive respiratory failure. She could survive by 100 days of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support and finally, underwent heart-lung transplantation. This is the first successful pediatric heart-lung transplantation carried out in Korea.

Keywords: Heart-Lung Transplantation, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, Interstitial Lung Disease, Inhalation Exposure

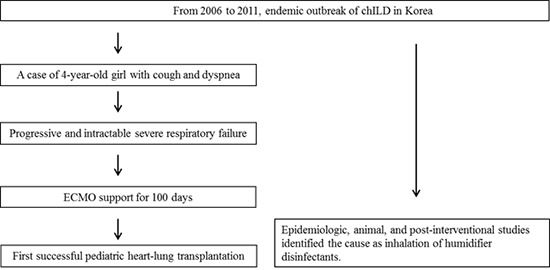

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Children’s interstitial lung disease (chILD) comprises a group of heterogeneous lung conditions characterized by diffuse lung pathology and disordered gas exchange, resulting in high morbidity and mortality (1,2,3). Recently, we reported 16 cases of a particular type of chILD that occurred between 2006 and 2011 in Korea, initially presenting with mild symptoms suggestive of a respiratory infection but rapidly progressing to respiratory failure with a high mortality rate (44%) (4). In addition, two familial cases with the same clinical manifestations were reported (5). Pathologic findings of centrilobular bronchiolar destruction and alveolar damage with fibrosis suggested interstitial lung disease (ILD), possibly associated with inhalation toxicity (6). Epidemiologic and animal studies identified humidifier disinfectants (HD) as a likely cause of this fatal lung disease (7,8,9). Indeed, no new cases were identified during the 2 years after humidifier disinfectants were removed from markets (6).

Here, we report a child with irreversible respiratory failure caused by HD-associated ILD who underwent heart-lung transplantation after a long period of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support. This is the first documented case of pediatric heart-lung transplantation in Korea.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 4-year-old girl was transferred to our hospital with a 2-month history of progressive respiratory problems. Initially, she developed a mild dry cough with no underlying lung disease. However, she developed dyspnea and tachypnea about 2 weeks after initial symptom onset, which became progressively worse and necessitated admission to a tertiary hospital to which her mother and 1-year-old sister had been admitted several days earlier suffering from similar symptoms. The patient was initially diagnosed with chILD of unknown origin and was treated with methyl prednisolone, hydroxychloroquine, and cyclophosphamide. However, the clinical symptoms and radiologic findings worsened (Fig. 1), which brought her to our hospital at June 11th, 2011. Unfortunately, her younger sister could not be transferred and expired one week after her transfer. The patient and her family members had used HD which-contained polyhexamethylene-guanidine (PHMG) as one of components.

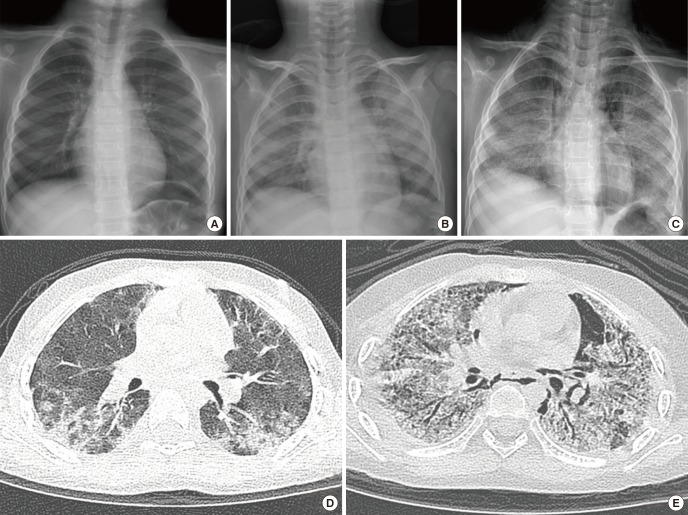

Fig. 1.

Serial follow-up of radiologic examination before transfer to our hospital. (A) Initial chest x-ray showed normal chest radiography. (B) Chest radiograph taken one month after symptom develop revealed diffuse haziness in both lung field. (C) Diffuse reticulo-nodular opacities in both lung fields were aggravated and pneumomediastinum along the bilateral mediastinum were developed after two months. (D) A high-resolution CT scan performed 2 weeks after symptom onset revealed peribronchial and subpelural consolidation, especially in dependent portion of both lower lobes. (E) A follow-up CT scan performed 2 months later showed increased diffuse ground glass opacities with traction bronchiectasis and cystic lesions in both lungs. Pulmonary interstitial emphysema in the left lower lobe and pneumomediastinum also detected.

Her initial respiratory rate was 77 breaths per minute, her pulse rate was 136 beats per minute, and her blood pressure was 113/81 mmHg. Because the patient had already developed air leak syndrome involving subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum, we tried to avoid intubation and maintained oxygenation as efficiently as possible. Thus, the patient received 100% oxygen via a 15 L reservoir mask bag and was lightly sedated to prevent further air leak. She also received intravenous immunoglobulin, azathioprine, and montelukast. However, her condition continued to worsen. She was intubated on Day 8 post-hospitalization. Despite high-frequency oscillatory ventilator care with nitric oxide, desaturation and hypoxemia became worse (saturation < 80% and the PaO2 ≤ 40 mmHg). For respiratory support, we applied veno-venous ECMO via right internal jugular vein and right femoral vein surgical cannulation on Day 12 post-hospitalization. ECMO initially improved the hypoxemia, and her condition appeared to be stabilized; however, respiratory failure progressed to the point that it was considered irreversible. Therefore, she was registered to lung transplantation. During ECMO, progressive pulmonary hypertension was observed by serial echocardiography follow-up. She was switched from veno-venous ECMO to veno-arterial ECMO with right common carotid arterial annulation to provide more effective systemic perfusion with cardiac and pulmonary support after 83 days of ECMO support. Eventually, on Day 100 of ECMO support, she received heart and lung from 11-year-old girl with brain death. The donor to recipient body weight ratio was 1.3 (23.1/17 kg). The ratios of preoperatively measured lung size (donor/recipient) were as follows: T1 (aortic arch level to transverse dimension) 17.6/11.8, T2 (diaphragm level to transverse dimension) 19.8/17, L1 (apex of right lung to diaphragm level) 15.9/11.3 and L2 (apex of left lung to diaphragm level) 15.8/12.3. Due to size mismatch and overinflation of the lung, the sternum was left open. However, we could perform sternal closure without further procedure on Day 2 post transplant. Histological examination of the explanted lung showed interstitial organizing fibrosis and multiple microabscesses (Fig. 2). The patient was extubated on Day 11 post-transplant without acute complication; however, she suffered several morbidities due to prolonged ECMO support including chronic renal failure requiring hemodialysis and pancreatic pseudocyst. She was transferred to a general ward on Day 83 post-transplant. Six months after transplantation, a follow-up abdominal CT accidentally detected lesions in the liver and kidney, which were diagnosed as monomorphic B-cell post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease. She received chemotherapy with a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody (rituximab®), and the condition resolved. The latest pulmonary function test (performed at 3 years post-transplant) showed a forced expiratory volume in 1 second of 0.95 L and a forced vital capacity of 1.01 L, which were 76.3% and 74.2% of predicted values, respectively. Echocardiography found no evidence of pulmonary hypertension with good function (ejection fraction 62% and fractional shortening 32%). Routine follow-up imaging study revealed no evidence of transplant-associated complications such as bronchiolitis obliterans (BO) (Fig. 3).

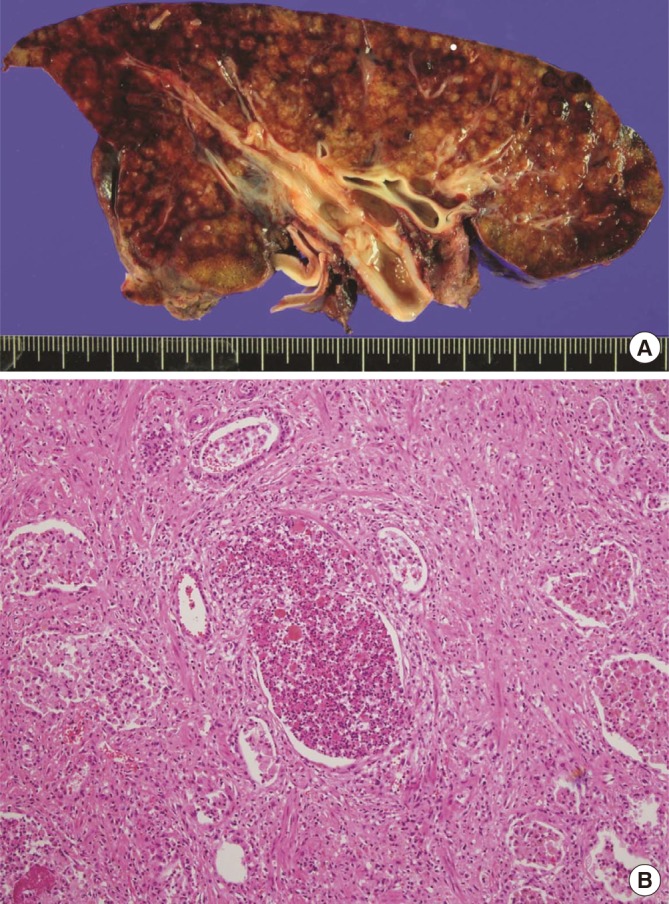

Fig. 2.

Explanted lung of recipient. (A) Gross finding of explanted lung tissue showed diffuse parenchymal consolidation and multiple mucus plugs in the bronchus. (B) Histologic examination of explanted lung biopsy revealed interstitial organizing fibrosis and multiple microabscesses.

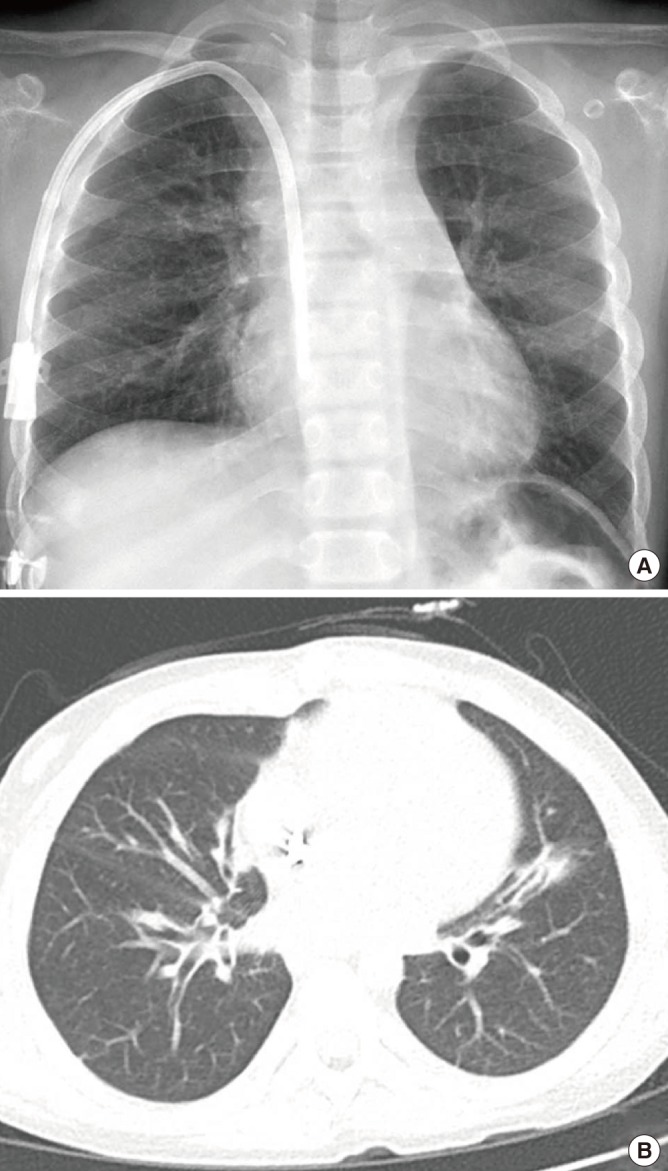

Fig. 3.

Follow up imaging studies at three years post-heart-lung transplantation.

(A) Simple chest x-ray showed no active lung lesion. (B) Chest CT scans showed subsegmental atelectasis and diffuse bronchial wall thickening.

DISCUSSION

chILD comprises a diverse group of rare lung diseases, which often makes it difficult to identify a specific underlying cause. From 2006, an outbreak of a particular type of chILD had occurred in Korea. First nationwide survey was performed in 2008, which reported 78 cases with as high as 46.1% of mortality, but could not identify the cause (10). Although progressive clinical course and fatal outcome of the disease are similar to those of acute interstitial pneumonitis, this disease is characterized by unique pathologic patterns of fibrosis in the bronchioles that are not observed in other chILD.

This disease gained much attention in 2011 when it was first reported in adults, mainly because the outcome was often fatal in pregnant and postpartum women. Finally, epidemiologic and animal studies including a nationwide investigation by the Korean Centers for Disease control and Prevention were undertaken, which identified toxic inhalation of HD as the cause (7,8,9). It contains PHMG, oligo (2-[2-ethoxy] ethoxyethyl) guanidium chrolide, 5-chloro-2-methylisothiazol-3(2H)-one/2-methyl isothiazol-3-one, and didecyldimethylammonium chloride. The annual incidence of the disease dropped to zero after sales of humidifier disinfectant were suspended in 2012 (6).

Recently, lung transplantation was considered as a possible therapeutic option for patients with end-stage lung disease. Although median 5 years survival rates after lung transplantation are still around 50%, any patient with a pulmonary disease associated with a life expectancy of less than 2 years (e.g., cystic fibrosis, primary or secondary pulmonary hypertension, ILD with pulmonary fibrosis, bronchiolitis obliterans, and surfactant protein b deficiency in children) is a potential candidate (11,12,13,14). According to the official registry report by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT), lung and/or heart-lung transplantation was first performed in adults and children in 1963 and 1986, respectively. As of 2012, a total of 43,428 lung and 3,703 heart-lung transplantations have been performed in adults, and 1,875 and 667, respectively, have been performed in children, worldwide according to ISHLT registry (14,15). However, long-term results are somewhat disappointing, with a median survival of 5.4 years in adults and 4.9 years in children. The 5 years survival rate for children undergoing a lung transplant is about 50%, and BO is responsible for 48% of deaths in those that survive more than 5 years post-transplant (13). The first lung transplant in Korea was performed in an adult patient in 1996. Prior to the present report, no such procedure had been performed in a child in Korea.

Many barriers to pediatric lung and/or heart-lung transplantation remain; for example, the scarcity of the available donors, size mismatches, and the more technically demanding surgical procedures required for small children. These constraints often extend the waiting time for organ allocation, which may necessitate longer periods of mechanical ventilator or ECMO support. As in the current case, these therapeutic interventions may increase the rate of treatment-related complications post-transplant. In our case, the patient was on ECMO for 100 days before a donor organ became available (by comparison, her mother received ECMO for only 5 days). Her mother suffered no sequelae, however, the patient suffered from multiple organ failure including the heart, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and pancreas due to prolonged ECMO support. A combined heart-lung transplant was required due to severe pulmonary hypertension and related both ventricular failure. The decision to perform lung or heart-lung transplantation is generally dictated by the presence/absence of irreversible left ventricular failure, although the preference of individual surgical teams will ultimately determine the options available (16). Airway complications such as bronchial anastomotic dehiscence, bronchial stenosis, or malacia are the major causes of morbidity and mortality after lung transplantation (11,17); these complications may be more common in pediatric cases due to the smaller airways. Thus, surgical preference and the size of the recipient may determine the best treatment option. However, recent improvements in surgical technique (such as living donor lobar transplantation) and size reduction procedures (such as lobectomy, wedge resection, and split partitioning to the donor lung) all helped to overcome the aforementioned constraints (18,19,20). Considering the improved life expectancy of pediatric patients after surgery, we suggest that lung transplantation be considered more actively as a life-saving therapeutic option in Korea.

In summary, we report a case of pediatric heart-lung transplantation in Korea. The patient was diagnosed with a particular type of chILD caused by toxic inhalation of humidifier disinfectant. Although she suffered post-transplant comorbidities, her life was saved by the heart-lung transplant.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Conception and coordination of the study: Jhang WK, Yu J. Acquisition of data: Jhang WK, Lee E, Yu J. Manuscript preparation: Jhang WK, Park SJ, Lee E, Yang SI, Hong SJ, Seo JH, Kim H, Park J, Yun T, Kim HR, Kim Y, Kim DK, Park S, Lee S, Hong S, Shim T, Choi I, Yu J. Writing the first draft of the manuscript: Jhang WK. Review and revising the manuscript: Jhang WK, Yu J. Manuscript approval: all authors.

References

- 1.Fan LL, Deterding RR, Langston C. Pediatric interstitial lung disease revisited. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;38:369–378. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinwiddie R, Wallis C. Paediatric interstitial lung disease (PILD)—an update. Curr Paediatr. 2006;16:230–236. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clement A, Eber E. Interstitial lung diseases in infants and children. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:658–666. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00004707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee E, Seo JH, Kim HY, Yu J, Jhang WK, Park SJ, Kwon JW, Kim BJ, Do KH, Cho YA, et al. Toxic inhalational injury-associated interstitial lung disease in children. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:915–923. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.6.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee E, Seo JH, Kim HY, Yu J, Song JW, Park YS, Jang SJ, Do KH, Kwon J, Park SW, et al. Two series of familial cases with unclassified interstitial pneumonia with fibrosis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2012;4:240–244. doi: 10.4168/aair.2012.4.4.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim KW, Ahn K, Yang HJ, Lee S, Park JD, Kim WK, Kim JT, Kim HH, Rha YH, Park YM, et al. Humidifier disinfectant-associated children’s interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:48–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1088OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang HJ, Kim HJ, Yu J, Lee E, Jung YH, Kim HY, Seo JH, Kwon GY, Park JH, Gwack J, et al. Inhalation toxicity of humidifier disinfectants as a risk factor of children’s interstitial lung disease in Korea: a case-control study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohnuma A, Yoshida T, Tajima H, Fukuyama T, Hayashi K, Yamaguchi S, Ohtsuka R, Sasaki J, Fukumori J, Tomita M, et al. Didecyldimethylammonium chloride induces pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis in mice. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2010;62:643–651. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, Kim YH, Kwon JH. Fatal misuse of humidifier disinfectants in Korea: importance of screening risk assessment and implications for management of chemicals in consumer products. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:2498–2500. doi: 10.1021/es300567j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim BJ, Kim HA, Song YH, Yu J, Kim S, Park SJ, Kim KW, Kim KE, Kim DS, Park JD, et al. Nationwide surveillance of acute interstitial pneumonia in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2009;52:324–329. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huddleston CB. Pediatric lung transplantation. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15:199–207. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkby S, Hayes D., Jr Pediatric lung transplantation: indications and outcomes. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:1024–1031. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.04.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huddleston CB. Pediatric lung transplantation. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2011;13:68–78. doi: 10.1007/s11936-010-0105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benden C, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, Christie JD, Dipchand AI, Dobbels F, Kirk R, Lund LH, Rahmel AO, Yusen RD, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Sixteenth Official Pediatric Lung and Heart-Lung Transplantation Report--2013; focus theme: age. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yusen RD, Christie JD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, Benden C, Dipchand AI, Dobbels F, Kirk R, Lund LH, Rahmel AO, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirtieth Adult Lung and Heart-Lung Transplant Report--2013; focus theme: age. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:965–978. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall SE, Kramer MR, Lewiston NJ, Starnes VA, Theodore J. Selection and evaluation of recipients for heart-lung and lung transplantation. Chest. 1990;98:1488–1494. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.6.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvarez A, Algar FJ, Santos F, Lama R, Baamonde C, Cerezo F, Salvatierra A. Pediatric lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1519–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Couetil JP, Tolan MJ, Loulmet DF, Guinvarch A, Chevalier PG, Achkar A, Birmbaum P, Carpentier AF. Pulmonary bipartitioning and lobar transplantation: a new approach to donor organ shortage. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113:529–537. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(97)70366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aigner C, Mazhar S, Jaksch P, Seebacher G, Taghavi S, Marta G, Wisser W, Klepetko W. Lobar transplantation, split lung transplantation and peripheral segmental resection--reliable procedures for downsizing donor lungs. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos F, Lama R, Alvarez A, Algar FJ, Quero F, Cerezo F, Salvatierra A, Baamonde C. Pulmonary tailoring and lobar transplantation to overcome size disparities in lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1526–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]