Abstract

The prevalence of type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has increased dramatically during the last 2 decades, a fact driven by the increased prevalence of obesity, the primary risk factor for T2DM. The figures for diabetes in the Arab world are particularly startling as the number of people with diabetes is projected to increase by 96.2% by 2035. Genetic risk factors may play a crucial role in this uncontrolled raise in the prevalence of T2DM in the Middle Eastern region. However, factors such as obesity, rapid urbanization and lack of exercise are other key determinants of this rapid increase in the rate of T2DM in the Arab world. The unavailability of an effective program to defeat T2DM has serious consequences on the increasing rise of this disease, where available data indicates an unusually high prevalence of T2DM in Arabian children less than 18 years old. Living with T2DM is problematic as well, since T2DM has become the 5th leading cause of disability, which was ranked 10th as recently as 1990. Giving the current status of T2DM in the Arab world, a collaborative international effort is needed for fighting further spread of this disease.

Keywords: Diabetes, Arab world, Epidemiology, Etiology, Risk factors and complication

Core tip: The Middle Eastern and North African region has the second highest rate of increases in diabetes anywhere in the world. We comprehensively review type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in adults and children from 22 Arab speaking countries by reviewing data published from 1980 to 2015; this allowed us to have a better view of the trends in the dramatic increases of T2DM impacting the Arabic region. We also discuss the etiology of this uncontrolled medical crisis and the most commonly reported complications in these Arab speaking countries. Finally, we highlight a number of crucial data that appear to be unavailable but which may be essential for a more comprehensive understanding of the diabetes epidemic sweeping the Arabian region.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) affects more than 382 million people around the world, of whom 90% are diagnosed with type-2 DM (T2DM)[1]. The prevalence of T2DM has increased dramatically during the last 2 decades[1]. The Arab world is not immune from this epidemic in the prevalence of T2DM. In fact, the Middle Eastern and North African region has the second highest rate of increase in diabetes globally, with the number of people with diabetes is projected to increase by 96.2% in 2035[1]. Having T2DM increases the burden for both patients and their caregivers, and of particular concern for Arab governments is the large economic burden of diabetes in terms of cost of treatment, management of complications, disability and loss of productivity[2-4]. The factors associated with T2DM seem more pronounced in the Arab world. Although genetic risk factors can’t be ruled out in the context of T2DM in the Arab world, factors such as obesity, rapid urbanization and lack of exercise are key determinants of the rapid increase of the rate of T2DM among the Arab world[5].

The unavailability of an effective program to contain the dramatic rise in T2DM in the Arab world has led to a serious development in the disease’s course, where current data indicates that T2DM can’t be ruled out in children less than 18 years old. Children diagnosed with T2DM come from all countries in the Arab world and obesity is a hallmark feature in this age group[6,7].

This review will initially address the epidemiology of T2DM in the Arab world, followed by the etiology of the disease, complication and risk factors of T2DM, and finally will discuss some suggestions related to research on T2DM in the Arab world.

RESEARCH METHODS

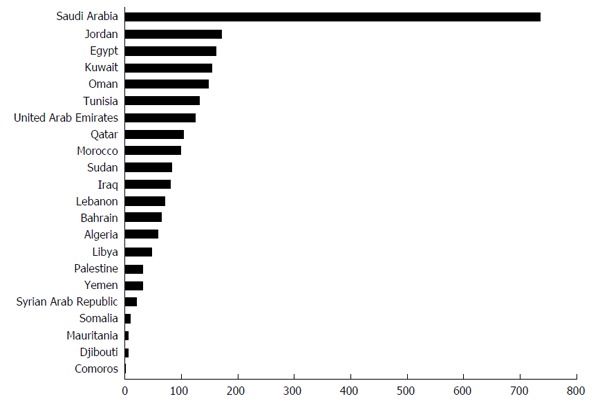

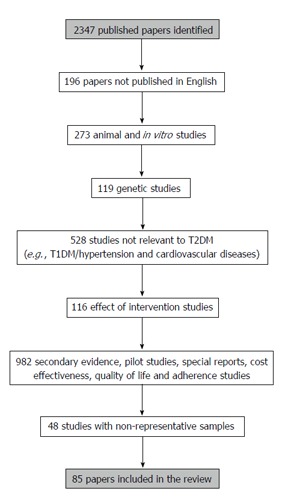

We undertook a search of the medical literature using the PubMed, EMBASE and Ovid databases for articles published in English language between 1980 and 2015, and included the following keywords: Diabetes, Arab world, epidemiology, etiology, risk factors and complication, or their corresponding MeSH term synonyms. Among 22 Arabic countries, a total of 2347 papers were identified and screened by title and/or abstract (Figure 1). To ensure that we included the highest number of epidemiological studies from each country, we did not set any limitations on the study design in our exclusion criteria. However, animal or genetic studies, studies not relevant to T2DM, studies on the effects of treatment, and non-primary data such as review articles or adherence studies were excluded (Figure 2). A total of 85 studies were added in the article and were reviewed in full. Among these, 3 studies were concerning Arab immigrants in different countries not listed in Figure 1, and 1 study (not PubMed indexed) was obtained from the references of other paper.

Figure 1.

Number of studies reviewed by title and/or abstract for each Arabic country.

Figure 2.

Research scheme and exclusion criteria. T2DM: Type-2 diabetes mellitus; T1DM: Type-1 diabetes mellitus.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Adults

Based on the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimates from 2013[1], three countries from the Arabic world are among the top 10 countries worldwide for the prevalence of T2DM; these countries are Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Qatar. The data obtained from each country in the Arabic world reports variation regarding prevalence of T2DM. However, differences in reported prevalence of T2DM within each country can be attributed to the study design, population and diagnostic methods used to obtain these data. The data clearly confirms that the prevalence of T2DM has increased dramatically during the past two decades. For example, studies from Saudi Arabia in the 80’s indicated that prevalence of T2DM was between 2.4%-4.3%[8,9], while recent a study in Saudi Arabia indicated a dramatic increase in the rate of T2DM with an estimated prevalence of 25.4%[10]. This pattern of massive increases in the rate of T2DM is similar for Iraq, Oman and other countries within the Arabic world (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of type-2 diabetes mellitus in adult Arab population

| Ref. | Country | Year | Sample size | Main findings | Diagnostic technique |

| Bacchus et al[8] | Saudi Arabia | 1982 | 1385 | Prevalence of diabetes: 2.4% | WHO criteria |

| Fatani et al[9] | Saudi Arabia | 1987 | 5222 | Prevalence of diabetes: 4.3% | Random capillary blood glucose |

| Al-Nuaim et al[28] | Saudi Arabia | 1997 | 13177 | Prevalence of diabetes in urban males and females: 12%, 14% | Random plasma glucose |

| Prevalence of diabetes in rural males and females: 7%, 7.7% | |||||

| Rahman Al-Nuaim et al[47] | Saudi Arabia | 1997 | 2059 | Prevalence of T2DM in obese males: 26.0% | OGTT |

| Prevalence of T2DM in non-obese males: 8.6% (P < 0.001) | |||||

| Prevalence of T2DM in obese females: 23.5% | |||||

| Prevalence of T2DM in non-obese females: 4.4% (P < 0.0001) | |||||

| el-Hazmi et al[48] | Saudi Arabia | 2000 | 14660 | Prevalence of obesity in males: 13.05% | FBG |

| Prevalence of obesity in females: 20.26% | |||||

| Prevalence of obesity in diabetics: 29.98% | |||||

| Prevalence of obesity in non-diabetics: 15.87% (P < 0.0001) | |||||

| Al-Nozha et al[49] | Saudi Arabia | 2004 | 16917 | Prevalence of diabetes: 23.7% | FPG |

| Almajwal et al[50] | Saudi Arabia | 2009 | 195851 | Prevalence of diabetes: 17.2% | FBG |

| Al-Rubeaan et al[10] | Saudi Arabia | 2014 | 18034 | Prevalence of diabetes: 25.4% | FPG |

| Al-Rubeaan et al[51] | Saudi Arabia | 2014 | 53370 | Prevalence of abnormal glucose metabolism: 34.5% | FPG |

| El Bcheraoui et al[52] | Saudi Arabia | 2014 | 10735 | Prevalence of diabetes: 13.4% | FPG |

| Abdella et al[53] | Kuwait | 1996 | 8336 | Prevalence of diabetes: 7.6% | Medical chart review |

| Al Khalaf et al[54] | Kuwait | 2010 | 560 | Prevalence of diabetes: 21.4% | FBG |

| Alarouj et al[20] | Kuwait | 2013 | 1970 | Prevalence of diabetes: 17.9% | FPG |

| Al Zurba et al[55] | Bahrain | 1996 | 498 | Prevalence of diabetes: 25.5% | FPG |

| Malik et al[56] | UAE | 2005 | 5758 | Prevalence of T2DM: 20.2% | FPG |

| Saadi et al[57] | UAE | 2007 | 2455 | Prevalence of diagnosed T2DM: 10.5% | FBG |

| Prevalence of undiagnosed T2DM: 6.6% | |||||

| Mansour et al[58] | Iraq | 2007 | 13730 | Incidence of T2DM: 6.8% | FPG |

| Mansour et al[59] | Iraq | 2014 | 5445 | Prevalence of T2DM: 19.7% | FPG |

| Al-Moosa et al[21] | Oman | 2006 | 5840 | Prevalence of T2DM: 11.6% | FPG |

| Al-Lawati et al[60] | Oman | 2015 | NA | Age-adjusted prevalence of T2DM: 10.4% to 21.1% | FPG and OGTT |

| Musaiger et al[61] | Qatar | 2005 | 535 | Prevalence of T2DM among obese females ≥ 50 yr: 51.4% | Self-reported diabetes |

| Bener et al[22] | Qatar | 2009 | 1117 | Prevalence of T2DM: 16.7% | FBG and OGTT |

| Al-Habori et al[62] | Yemen | 2004 | 498 | Prevalence of T2DM: 7.4% | FPG |

| Gunaid et al[63] | Yemen | 2008 | 250 | Prevalence of T2DM: 10.4% | FPG and OGTT |

| Abdul-Rahim et al[23] | Palestine | 2001 | 302 | Prevalence of T2DM: 12% | OGTT |

| Ajlouni et al[64] | Jordan | 2008 | 1121 | Prevalence of T2DM: 17.4% | FPG |

| Albache et al[65] | Syria | 2010 | 806 | Prevalence of T2DM: 15.6% | FPG |

| Hirbli et al[66] | Lebanon | 2005 | 3000 | Prevalence of T2DM: 15.6% | FPG |

| Herman et al[67] | Egypt | 1998 | 1451 | Prevalence of T2DM: 9.3% | OGTT |

| Abolfotouh et al[68] | Egypt | 2008 | 1800 | Prevalence of T2DM: 3.7% | FBG |

| Elbagir et al[25] | Sudan | 1996 | 1284 | Prevalence of T2DM: 3.4% | OGTT |

| Noor et al[69] | Sudan | 2015 | 1111 | Prevalence of T2DM: 1.3% | FBG |

| Prevalence of undiagnosed T2DM: 2.6% | |||||

| Bouguerra et al[26] | Tunisia | 2007 | 3729 | Prevalence of T2DM: 9.9% | FPG |

| Ben Romdhane et al[70] | Tunisia | 2014 | 7700 | Prevalence of T2DM: 15.1% | FPG |

| Kadiki et al[71] | Libya | 2001 | 868 | Prevalence of T2DM: 14.1% | OGTT |

| Rguibi et al[72] | Morocco | 2006 | 249 | Prevalence of undiagnosed T2DM: 6.4% | FPG |

| Bos et al[29] | North Africa | 2013 | NA | Prevalence of diabetes: Range from 2.6% in rural Sudan to 20.0% in urban Egypt | NA |

| Prevalence of diabetes significantly higher in urban than rural areas | |||||

| Significantly higher prevalence of overweight/obesity in females than males in Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia and Sudan | |||||

| Jaber et al[73] | United States (Arab-Americans) | 2003 | 542 | Prevalence of T2DM in males: 22.0% | OGTT |

| Prevalence T2DM in females: 18.0% | |||||

| Rissel et al[74] | Australia (Arab immigrants) | 1998 | 528 | Prevalence of overweight or obesity in males: 73% | NA |

| Prevalence of overweight or obesity in females: 36% | |||||

| Thow et al[75] | Australia (people born in Middle East and North Africa) | 2005 | NA | Highest prevalence and incidence of T2DM | NA |

| Second highest ratio of hospitalization and mortality | |||||

| Standard prevalence ratio for diabetes among Arabic-speaking subjects significantly 3.6 times higher than English-only speaking subjects |

WHO: World Health Organization; OGTT: Oral glucose tolerance test; FBG: Fasting blood glucose; FPG: Fasting plasma glucose; UAE: United Arab Emirates; NA: Data not available; T2DM: Type-2 diabetes mellitus.

Children and adolescents

Due to the recent recognition of T2DM during childhood, limited data are available worldwide. This unusual age-related disease has become a focus of attention for medical organizations around the world. A recent analysis showed a significant increase of 30.5% in the prevalence of T2DM among children and adolescents aged 10-19 years old in United States from 2001 to 2009[11]. The international society for pediatric and adolescents diabetes has published comprehensive guidelines for screening, diagnosis and treatment of T2DM in children and adolescents[12].

Not surprisingly, data from the Arab world show similar figures for childhood T2DM. Perhaps more worrying is that recent data from Saudi Arabia reports an age-specific prevalence of 1 per 1000 for T2DM in children less than 18 years old[7], which was similar to the highest prevalence found in specific groups (American Indian and African American) in United States[12]. Additional findings on childhood T2DM are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence of type-2 diabetes mellitus in Arab podiatric and children

| Ref. | Country | Year | Sample size | Main findings | Diagnostic technique | Notes |

| Punnose et al[76] | UAE | 2005 | 96 | 11 children diagnosed with T2DM | FPG | (8-18 years old) |

| 9/11 children were Arab origin | Case series | |||||

| 8/11 children were overweight or obese | ||||||

| 10/11 children were female | ||||||

| Moussa et al[6] | Kuwait | 2008 | 128918 | T2DM found in 45 children | NA | (6-18 years old) |

| Prevalence of T2DM in male children: 47.3/10000 | Medical record review | |||||

| Prevalence of T2DM in female children: 26.3/10000 (P = 0.05) | ||||||

| Al-Agha et al[77] | Saudi Arabia | 2012 | 387 | Prevalence of T2DM: 9.04% | NA | (2-18 years old) |

| Retrospective cross-sectional study | ||||||

| Al-Rubeaan et al[7] | Saudi Arabia | 2015 | 23523 | Age adjusted Prevalence of T2DM: 1/1000 | FPG | ≤ 18 yr |

| Ali et al[78] | Egypt | 2013 | 210 | 28 out of 210 children with diabetes diagnosed with T2DM | Fasting serum C-peptide levels | (1-18 years old) |

| 64.3% of T2DM children were female (P = 0.04) | ||||||

| Osman et al[79] | Sudan | 2013 | 958 | 38/985 children identified with T2DM | NA | (11-18 years old) |

| 32/38 of cases were from tribes of Arab origin | Retrospective cross sectional | |||||

| Ehtisham et al[80] | United Kingdom | 2000 | 8 | First 8 cases reported with T2DM in United Kingdom | NA | (9-16 years old) |

| All cases were overweight and originated from India, Pakistan and Arab countries | Retrospective cross sectional |

UAE: United Arab Emirates; FPG: Fasting plasma glucose; NA: Data not available; T2DM: Type-2 diabetes mellitus.

RISK FACTORS

A number of risk factors could account for the uncontrolled rise in T2DM in the Arab world, with genetic factors likely to play an important role. However, a number of modifiable risk factors such as obesity, rapid urbanization and its associated changes in dietary habits and lack of physical activity are also important determinants in the etiology of T2DM. Other considerations such as multiple pregnancies and a lack of health education may be unique challenges in the diabetes epidemic in the Arab world.

Obesity

Obesity represent a large component in the pathogenesis of T2DM[13], and is by far the primary risk factor for the increased prevalence of T2DM globally[14]. Obesity not only worsens the prognosis of T2DM, but obese diabetics suffer higher rates of microvascular complications and mortality[15-18]. Obesity-related T2DM has been investigated in several countries in the Arab world. In Saudi Arabia, a study of 14252 diabetic patients reported that more than half of the obese diabetics had poor glycemic control[19]. Additionally, the first national health survey in Kuwait indicates that 48% obese males and 77% obese females were also diabetics[20], confirming a significant association between obesity and diabetes [odds ratio (OR) of 2.87] in the Kuwaiti population. In Oman and Qatar, 60.1% and 59.7% of the diabetic patients were obese respectively[21,22]. The average body mass index (BMI) in Palestinian and Lebanese diabetics was 33.7 kg/m2 and 30.8 kg/m2 respectively[23,24]. Nevertheless, obesity is significantly associated with diabetes even in some Arab countries such as Sudan and Tunisia where the prevalence of diabetes can be described as relatively low - the relative risk of developing T2DM was 1.74 (95%CI: 1.32-2.28) in obese Sudanese subjects and the OR of having T2DM was 1.61 (95%CI: 1.34-1.93) in obese Tunisians[25,26].

A recent analysis of 46 Muslim countries (where Muslims represent > 50% of the population) estimated the prevalence of overweight subjects reported that in the Eastern Mediterranean region, females were more likely to be overweight than males (42.1% vs 33%)[27]. Interestingly, those living in Arab countries were 2.92 (95%CI: 2.86-2.97) times more likely to be overweight compared to those living in non-Arab Muslim countries.

Rapid urbanization

Urbanizing of many rural areas within the Arab world carries with it many advantages in term of access to improved medical services, access to education and other “modern” conveniences. There are significant differences in the rate of T2DM between rural and urban communities. For example, an early study in Saudi Arabia found that the prevalence of T2DM in urban communities was 12% and 14% in males and females respectively, which was nearly double the prevalence of T2DM in males and females residing rural areas (7% and 7.7% for males and females respectively)[28]. Another study in Oman indicated that urban residence was significantly associated with T2DM (OR = 1.7, 95%CI: 1.4-2.1), with the prevalence of T2DM was 17.7% and 10.5 in urban and rural areas respectively[21]. Moreover, a systematic review of the prevalence of T2DM in North Africa found that the prevalence of T2DM ranged from 2.6% in rural Sudan to 20.0% in urban Egypt[29].

Dietary habits

The Mediterranean diet is considered to be one of the healthiest food options available, as it contains a variety of fruits, vegetables, grains and olive oil. In fact, several studies have shown significant reduction in the rate of T2DM with the Mediterranean diet[30,31]. However, one is unlikely to obtain the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet without proper adherence, which may be a common habit in most of the Eastern Mediterranean countries. In a comparative risk assessment analysis, data from the United Food and Agricultural Organization was used to estimate the dietary intake of 20 countries in the Middle East and North Africa[32]. These estimates were used to provide a country specific estimates of cardio-metabolic disease mortality secondary to 15 different dietary and metabolic risk factors. This analysis shows that there is suboptimal intake of the “protective” diets (e.g., fruits, vegetables and sea food), and greater consumption of “harmful” diets (e.g., processed meat and trans fatty acids). These results were reflected in the cardio-metabolic disease mortality rate, where non-optimal BMI was the second leading metabolic risk factor for cardio-metabolic disease mortality, accounting for 21% of all cardio-metabolic mortality risk factors, followed by high fasting blood glucose (> 5.3 mmol/L) which accounted for 17% of all cardio-metabolic disease deaths.

Sedentary life style

Numerous studies confirm that physical activity reduces the incidence and/or severity of T2DM[33-35]. Six years of leading an active life coupled with a healthy diet can reduce the incidence of T2DM by 43% in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance followed for 20 years[36]. Another meta-analysis shows that exercise training reduces glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) by 0.66% in type-2 diabetic patients, a percentage that should substantially reduce the complications of T2DM[37]. Not surprisingly, a sedentary life style is one of the most important modifiable risk factors in the Arab world, specifically when comparing the prevalence of highly active subjects in the Arab world with the global data. Among 52746 subject from 20 countries included to study the prevalence of physical activity, 8 countries reported that more than 50% of the population are highly active based on the international physical activity questionnaire[38]. Saudi Arabia, which was the only country from the Arab world that was included in their analysis, is reported to have 26.2% of their population as being highly active. More recent data came from a study over 10 Eastern Mediterranean countries indicating that the highest level of physically active adolescents were in the Emirates (23.9%), while the lowest was in Egypt (9.2%), giving an overall prevalence of physically active adolescents in the Eastern Mediterranean countries of 19%[39].

Other factors

Several factors can explain the unrestrained raise in the rate of T2DM in the Arabian area. Some are attributed to the Eastern cultural heritage from a hundred of years ago, such as multiple pregnancies and cultural barriers for women’s physical activity. However, despite no changes in the traditional risk factors for T2DM in Arabian area, there is an alarming increase in the prevalence of diabetes, particularly within the last two decades - suggesting that recent lifestyle changes may have greater effect on this crisis. The global change impacts the Arab nations even more dramatically than elsewhere: Temperatures that are already scorching on a regular basis are now increased (higher temperatures for longer periods), even more increases in polluted and dusty air. These conditions combine to further discourage many people - regardless of age or gender - from any kind of outdoor activity. The situation is made even worse by the political instability in many of these countries, which affects access to healthy food and medical care.

COMPLICATIONS

According to the World Health Organization, diabetes is the 8th leading cause of death in the world[40]. Data published specifically from the Arab world shows a similar trend to that available globally. A recent analysis indicates that diabetes represents the 5th leading cause of death in the Arab world in 2010, compared to it being the 11th leading cause of death in 1990[41]. Living with T2DM is troublesome as well, as diabetes is the 5th leading cause for the disability-adjusted life years in high income Arabic countries in 2010, compared to it being ranked as the 10th reason in twenty years earlier[41]. The studies summarized in Table 3 summarize the most recent data on the prevalence of common complications (retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy and peripheral vascular diseases) in diabetic patients from the Arab world.

Table 3.

Diabetes complications in the Arab world

| Country | Year | Sample size | Prevalence of complication | Ref. |

| Saudi Arabia | 2015 | 50464 | Retinopathy: 19.7% | [81] |

| 2015 | 3800 | Blindness: 33% | [82] | |

| 2014 | 54670 | Nephropathy: 10.8% | [83] | |

| 2015 | 62681 | Diabetic foot: 3.3% | [84] | |

| Foot ulcer: 2.05% | ||||

| Gangrene: 0.19% | ||||

| Amputation: 1.06% | ||||

| 2014 | 552 | Peripheral neuropathy: 19.9% | [85] | |

| Kuwait | 2007 | 165 | Retinopathy: 40% | [86] |

| Emirates | 2007 | 513 | Retinopathy: 19% | [87] |

| 2007 | 2455 | Retinopathy: 54.2% | [57] | |

| Nephropathy: 40.8% | ||||

| Neuropathy: 34.7% | ||||

| Peripheral vascular disease: 11.1% | ||||

| Bahrain | 2009 | 712 | Microalbuminuria: 27.9% | [88] |

| 2007 | 1477 | Neuropathy: 36.6% | [89] | |

| Foot ulcer: 5.9% | ||||

| Peripheral vascular disease: 11.8% | ||||

| Qatar | 2011 | 540 | Retinopathy: 23.5% | [90] |

| 2014 | 1633 | Retinopathy: 12.5% | [91] | |

| Nephropathy: 12.4% | ||||

| Neuropathy: 9.5% | ||||

| Oman | 2003 | 2249 | Retinopathy: 14.9% | [92] |

| 2009 | 418 | Retinopathy: 7.9% | [93] | |

| 2012 | 2551 | Microalbuminuria: 37% | [94] | |

| Nephropathy: 5% | ||||

| 2012 | 699 | Nephropathy: 42.5% | [95] | |

| Yemen | 2011 | 694 | Blindness: 15.7% | [96] |

| 2009 | 350 | Retinopathy: 55% | [97] | |

| 1997 | 1095 | Peripheral neuropathy: 40.7% | [98] | |

| 2010 | 311 | Peripheral vascular disease: 9.1% | [99] | |

| Jordan | 2015 | 3638 | Blindness: 1.3% | [100] |

| Severe visual impairment: 1.82% | ||||

| Correctable visual impairment: 9.49% | ||||

| 2008 | 986 | Retinopathy: 64.1% | [101] | |

| 2005 | 986 | Blindness: 7.4% | [102] | |

| 2003 | 1142 | Microalbuminuria: 33% | [103] | |

| Ulceration: 4% | ||||

| Amputation: 5% | ||||

| Egypt | 2011 | 1325 | Retinopathy: 20.5% | [104] |

| 2015 | 2000 | Neuropathy: 29.3% | [105] | |

| Peripheral vascular disease: 11% | ||||

| 1998 | 4600 | Retinopathy: 42% | [67] | |

| Blindness: 5% | ||||

| Nephropathy: 7% | ||||

| Neuropathy: 22% | ||||

| Foot ulcer: 1% | ||||

| Tunisia | 2014 | 2320 | Retinopathy: 26.3% | [106] |

| Libya | 2012 | 260 | Retinopathy: 16.2% | [107] |

| Nephropathy: 1.5% | ||||

| Neuropathy: 11.2% |

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The high prevalence of T2DM in Arab nations offers an opportunity to better understand the disease and its treatment. Unfortunately, current research in the Arab nations does not match the level of this health crisis in the area. Large portions of critical data information are unavailable in many countries from the Arab world. For instance, predicting the prevalence of T2DM statistically could crucial in formulating a strategic plan for combating the disease, which requires comprehensive knowledge about its current burden, for which data is available only from Tunisia and Saudi Arabia. The Tunisian study revealed that the prevalence of T2DM in Tunisia will reach 26.6% in 2027[42]. Moreover, it predicts that a 20% reduction in obesity and smoking will yield in a 3.3% reduction in T2DM by 2027. On the other hand, the Saudi study indicates that the prevalence of T2DM in Saudi Arabia could reach 44.1% in 2022, a figure which differs significantly from IDF estimates[43].

It would be important to apply the recommendations on physical activity discussed at conference on Healthy Lifestyles and Non-Communicable Diseases in the Arab World and the Middle East, also called the “Riyadh declaration”[44]. To successfully implement the recommendations of the Riyadh declaration, novel research is needed to determine the social determinants for developing diabetes in the Arab world. For instance, a population based longitudinal cohort of 5124 diabetes-free participants in United States revealed that people residing neighborhoods with fewer opportunities for physical activity have nearly double the risk of developing T2DM[45].

Considering the epidemic nature of obesity and T2DM in the Arab world, studies on the ethnic-specific obesity cut-off points for the risk of diabetes are certainly necessary for peoples of the Arab and North African populations. For example, the risk of diabetes increases with BMI values greater than 25 kg/m2 for South Asians, at 27 kg/m2 for African-Caribbeans and at 30 kg/m2 for Europeans[46].

CONCLUSION

The data obtained from the Arabic world indicates that there is an uncontrolled rise in the prevalence of T2DM over the last two decades, in particular within the Gulf cooperation countries. For example, the prevalence of T2DM in early 1980’s was estimated 2.4%[8], and then increased to 12% in the late 1990’s[28], while recent data from Saudi Arabia shows that the prevalence of T2DM reached 25.4% in 2014. Given that obesity is a major risk factor for developing T2DM, obesity is associated with T2DM in Arab countries even where the prevalence of T2DM is relatively low. In addition, other factors such as rapid urbanization, unhealthy dietary habits and the lack of physical activity are key determinants of T2DM in the area. With this uncontrolled rise in the rate of T2DM in the Arab world, T2DM has now become the 5th leading cause of death in the Arab world. To better estimate the size of this crisis, studies aimed at predicting the rate of T2DM in the future are urgently needed. However, the vast majority of Arabian countries do not provide this important information. In order to successfully contain the uncontrolled rise of T2DM in the Arabian region, one should take advantage of the research conducted in other communities facing similar patterns in the increasing rates of diabetes. For example, genetic studies, ethnic-specific obesity cut-off points for the risk of diabetes studies and community studies to assess the appropriateness of the neighborhoods for physical activity may bring about increased awareness on the epidemic of diabetes sweeping the region-and so help in creating national/regional strategies to successfully limit the widespread firestorm of T2DM ravaging the Arabic region.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors have no financial conflicts of interest related to this work.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: December 18, 2015

First decision: January 18, 2016

Article in press: February 17, 2016

P- Reviewer: Gómez-Sáez JM, Papazoglou D, Tziomalos K S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 6th edition. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2013. Available from: http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. In 2007. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:596–615. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. The World Health Statistics. 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2008/en/index.ht. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Maskari F, El-Sadig M, Nagelkerke N. Assessment of the direct medical costs of diabetes mellitus and its complications in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:679. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badran M, Laher I. Type II Diabetes Mellitus in Arabic-Speaking Countries. Int J Endocrinol. 2012;2012:902873. doi: 10.1155/2012/902873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moussa MA, Alsaeid M, Abdella N, Refai TM, Al-Sheikh N, Gomez JE. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus among Kuwaiti children and adolescents. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17:270–275. doi: 10.1159/000129604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Rubeaan K. National surveillance for type 1, type 2 diabetes and prediabetes among children and adolescents: a population-based study (SAUDI-DM) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:1045–1051. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-205710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacchus RA, Bell JL, Madkour M, Kilshaw B. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus in male Saudi Arabs. Diabetologia. 1982;23:330–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00253739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fatani HH, Mira SA, el-Zubier AG. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in rural Saudi Arabia. Diabetes Care. 1987;10:180–183. doi: 10.2337/diacare.10.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Rubeaan K, Al-Manaa HA, Khoja TA, Ahmad NA, Al-Sharqawi AH, Siddiqui K, Alnaqeb D, Aburisheh KH, Youssef AM, Al-Batel A, et al. Epidemiology of abnormal glucose metabolism in a country facing its epidemic: SAUDI-DM study. J Diabetes. 2015;7:622–632. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Saydah S, Imperatore G, Linder B, Divers J, Bell R, Badaru A, Talton JW, Crume T, et al. Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. JAMA. 2014;311:1778–1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeitler P, Fu J, Tandon N, Nadeau K, Urakami T, Barrett T, Maahs D. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2014. Type 2 diabetes in the child and adolescent. Pediatr Diabetes. 2014;15 Suppl 20:26–46. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abuyassin B, Laher I. Obesity-linked diabetes in the Arab world: a review. East Mediterr Health J. 2015;21:420–439. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Wasserman DH, Castaneda-Sceppa C. Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2518–2539. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonora E, Targher G, Formentini G, Calcaterra F, Lombardi S, Marini F, Zenari L, Saggiani F, Poli M, Perbellini S, et al. The Metabolic Syndrome is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease in Type 2 diabetic subjects. Prospective data from the Verona Diabetes Complications Study. Diabet Med. 2004;21:52–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masuo K, Rakugi H, Ogihara T, Esler MD, Lambert GW. Cardiovascular and renal complications of type 2 diabetes in obesity: role of sympathetic nerve activity and insulin resistance. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2010;6:58–67. doi: 10.2174/157339910790909396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tobias DK, Pan A, Jackson CL, O’Reilly EJ, Ding EL, Willett WC, Manson JE, Hu FB. Body-mass index and mortality among adults with incident type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:233–244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logue J, Walker JJ, Leese G, Lindsay R, McKnight J, Morris A, Philip S, Wild S, Sattar N. Association between BMI measured within a year after diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and mortality. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:887–893. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Shahrani A, Al-Khaldi Y. Obesity among diabetic and hypertensive patients in Aseer region, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Obes. 2013;1:14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alarouj M, Bennakhi A, Alnesef Y, Sharifi M, Elkum N. Diabetes and associated cardiovascular risk factors in the State of Kuwait: the first national survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:89–96. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Moosa S, Allin S, Jemiai N, Al-Lawati J, Mossialos E. Diabetes and urbanization in the Omani population: an analysis of national survey data. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bener A, Zirie M, Janahi IM, Al-Hamaq AO, Musallam M, Wareham NJ. Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in a population-based study of Qatar. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;84:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdul-Rahim HF, Husseini A, Giacaman R, Jervell J, Bjertness E. Diabetes mellitus in an urban Palestinian population: prevalence and associated factors. East Mediterr Health J. 2001;7:67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naja F, Hwalla N, Itani L, Salem M, Azar ST, Zeidan MN, Nasreddine L. Dietary patterns and odds of Type 2 diabetes in Beirut, Lebanon: a case-control study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2012;9:111. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-9-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elbagir MN, Eltom MA, Elmahadi EM, Kadam IM, Berne C. A population-based study of the prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in adults in northern Sudan. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:1126–1128. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.10.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouguerra R, Alberti H, Salem LB, Rayana CB, Atti JE, Gaigi S, Slama CB, Zouari B, Alberti K. The global diabetes pandemic: the Tunisian experience. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61:160–165. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahan D. Prevalence and correlates of adult overweight in the Muslim world: analysis of 46 countries. Clin Obes. 2015;5:87–98. doi: 10.1111/cob.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Nuaim AR. Prevalence of glucose intolerance in urban and rural communities in Saudi Arabia. Diabet Med. 1997;14:595–602. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199707)14:7<595::AID-DIA377>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bos M, Agyemang C. Prevalence and complications of diabetes mellitus in Northern Africa, a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:387. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martínez-González MA, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Nunez-Cordoba JM, Basterra-Gortari FJ, Beunza JJ, Vazquez Z, Benito S, Tortosa A, Bes-Rastrollo M. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of developing diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:1348–1351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39561.501007.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salas-Salvadó J, Bulló M, Babio N, Martínez-González MÁ, Ibarrola-Jurado N, Basora J, Estruch R, Covas MI, Corella D, Arós F, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:14–19. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Afshin A, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Fahimi S, Shi P, Powles J, Singh G, Yakoob MY, Abdollahi M, Al-Hooti S, et al. The impact of dietary habits and metabolic risk factors on cardiovascular and diabetes mortality in countries of the Middle East and North Africa in 2010: a comparative risk assessment analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006385. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sigal RJ, Armstrong MJ, Colby P, Kenny GP, Plotnikoff RC, Reichert SM, Riddell MC. Physical activity and diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37 Suppl 1:S40–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LaMonte MJ, Blair SN, Church TS. Physical activity and diabetes prevention. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2005;99:1205–1213. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00193.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Wasserman DH, Castaneda-Sceppa C, White RD. Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes: a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1433–1438. doi: 10.2337/dc06-9910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, Gregg EW, Yang W, Gong Q, Li H, Li H, Jiang Y, An Y, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371:1783–1789. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60766-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boulé NG, Haddad E, Kenny GP, Wells GA, Sigal RJ. Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. JAMA. 2001;286:1218–1227. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bauman A, Bull F, Chey T, Craig CL, Ainsworth BE, Sallis JF, Bowles HR, Hagstromer M, Sjostrom M, Pratt M. The International Prevalence Study on Physical Activity: results from 20 countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al Subhi LK, Bose S, Al Ani MF. Prevalence of physically active and sedentary adolescents in 10 Eastern Mediterranean countries and its relation with age, sex, and body mass index. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12:257–265. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. Fact sheet No. 310. 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mokdad AH, Jaber S, Aziz MI, AlBuhairan F, AlGhaithi A, AlHamad NM, Al-Hooti SN, Al-Jasari A, AlMazroa MA, AlQasmi AM, et al. The state of health in the Arab world, 1990-2010: an analysis of the burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. Lancet. 2014;383:309–320. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saidi O, O’Flaherty M, Mansour NB, Aissi W, Lassoued O, Capewell S, Critchley JA, Malouche D, Romdhane HB. Forecasting Tunisian type 2 diabetes prevalence to 2027: validation of a simple model. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:104. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1416-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Quwaidhi AJ, Pearce MS, Sobngwi E, Critchley JA, O’Flaherty M. Comparison of type 2 diabetes prevalence estimates in Saudi Arabia from a validated Markov model against the International Diabetes Federation and other modelling studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bull F, Dvorak J. Tackling chronic disease through increased physical activity in the Arab World and the Middle East: challenge and opportunity. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:600–602. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christine PJ, Auchincloss AH, Bertoni AG, Carnethon MR, Sánchez BN, Moore K, Adar SD, Horwich TB, Watson KE, Diez Roux AV. Longitudinal Associations Between Neighborhood Physical and Social Environments and Incident Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1311–1320. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tillin T, Sattar N, Godsland IF, Hughes AD, Chaturvedi N, Forouhi NG. Ethnicity-specific obesity cut-points in the development of Type 2 diabetes - a prospective study including three ethnic groups in the United Kingdom. Diabet Med. 2015;32:226–234. doi: 10.1111/dme.12576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rahman Al-Nuaim A. Effect of overweight and obesity on glucose intolerance and dyslipidemia in Saudi Arabia, epidemiological study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1997;36:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(97)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.el-Hazmi MA, Warsy AS. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in diabetic and non-diabetic Saudis. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6:276–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Nozha MM, Al-Maatouq MA, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Harthi SS, Arafah MR, Khalil MZ, Khan NB, Al-Khadra A, Al-Marzouki K, Nouh MS, et al. Diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1603–1610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Almajwal AM, Al-Baghli NA, Batterham MJ, Williams PG, Al-Turki KA, Al-Ghamdi AJ. Performance of body mass index in predicting diabetes and hypertension in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:437–445. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.57165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Rubeaan K, Al-Manaa H, Khoja T, Ahmad N, Al-Sharqawi A, Siddiqui K, AlNaqeb D, Aburisheh K, Youssef A, Al-Batil A, et al. The Saudi Abnormal Glucose Metabolism and Diabetes Impact Study (SAUDI-DM) Ann Saudi Med. 2014;34:465–475. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2014.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.El Bcheraoui C, Basulaiman M, Tuffaha M, Daoud F, Robinson M, Jaber S, Mikhitarian S, Memish ZA, Al Saeedi M, AlMazroa MA, et al. Status of the diabetes epidemic in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Int J Public Health. 2014;59:1011–1021. doi: 10.1007/s00038-014-0612-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdella N, Khogali M, al-Ali S, Gumaa K, Bajaj J. Known type 2 diabetes mellitus among the Kuwaiti population. A prevalence study. Acta Diabetol. 1996;33:145–149. doi: 10.1007/BF00569425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Al Khalaf MM, Eid MM, Najjar HA, Alhajry KM, Doi SA, Thalib L. Screening for diabetes in Kuwait and evaluation of risk scores. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:725–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Al Zurba FI, Al Garf A. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus among Bahrainis attending primary health care centres. East Mediterr Health J. 1996;2:274–282. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Malik M, Bakir A, Saab BA, King H. Glucose intolerance and associated factors in the multi-ethnic population of the United Arab Emirates: results of a national survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saadi H, Carruthers SG, Nagelkerke N, Al-Maskari F, Afandi B, Reed R, Lukic M, Nicholls MG, Kazam E, Algawi K, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and its complications in a population-based sample in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;78:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mansour AA, Al-Jazairi MI. Predictors of incident diabetes mellitus in Basrah, Iraq. Ann Nutr Metab. 2007;51:277–280. doi: 10.1159/000105449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mansour AA, Al-Maliky AA, Kasem B, Jabar A, Mosbeh KA. Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in adults aged 19 years and older in Basrah, Iraq. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014;7:139–144. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S59652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Al-Lawati JA, Panduranga P, Al-Shaikh HA, Morsi M, Mohsin N, Khandekar RB, Al-Lawati HJ, Bayoumi RA. Epidemiology of Diabetes Mellitus in Oman: Results from two decades of research. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2015;15:e226–e233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Musaiger A, Shahbeek N. The relationship between obesity and prevalence of chronic diseases in the Arab women. J Hum Ecol Special Issue. 2005;13:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Al-Habori M, Al-Mamari M, Al-Meeri A. Type II Diabetes Mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in Yemen: prevalence, associated metabolic changes and risk factors. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2004;65:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gunaid AA, Assabri AM. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors in a semirural area in Yemen. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:42–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ajlouni K, Khader YS, Batieha A, Ajlouni H, El-Khateeb M. An increase in prevalence of diabetes mellitus in Jordan over 10 years. J Diabetes Complications. 2008;22:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Albache N, Al Ali R, Rastam S, Fouad FM, Mzayek F, Maziak W. Epidemiology of Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Aleppo, Syria. J Diabetes. 2010;2:85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-0407.2009.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hirbli KI, Jambeine MA, Slim HB, Barakat WM, Habis RJ, Francis ZM. Prevalence of diabetes in greater Beirut. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1262. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Herman WH, Aubert RE, Engelgau MM, Thompson TJ, Ali MA, Sous ES, Hegazy M, Badran A, Kenny SJ, Gunter EW, et al. Diabetes mellitus in Egypt: glycaemic control and microvascular and neuropathic complications. Diabet Med. 1998;15:1045–1051. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(1998120)15:12<1045::AID-DIA696>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abolfotouh MA, Soliman LA, Mansour E, Farghaly M, El-Dawaiaty AA. Central obesity among adults in Egypt: prevalence and associated morbidity. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:57–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Noor SK, Bushara SO, Sulaiman AA, Elmadhoun WM, Ahmed MH. Undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in rural communities in Sudan: prevalence and risk factors. East Mediterr Health J. 2015;21:164–170. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.3.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ben Romdhane H, Ben Ali S, Aissi W, Traissac P, Aounallah-Skhiri H, Bougatef S, Maire B, Delpeuch F, Achour N. Prevalence of diabetes in Northern African countries: the case of Tunisia. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kadiki OA, Roaeid RB. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in Benghazi Libya. Diabetes Metab. 2001;27:647–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rguibi M, Belahsen R. Prevalence and associated risk factors of undiagnosed diabetes among adult Moroccan Sahraoui women. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:722–727. doi: 10.1079/phn2005866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jaber LA, Brown MB, Hammad A, Nowak SN, Zhu Q, Ghafoor A, Herman WH. Epidemiology of diabetes among Arab Americans. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:308–313. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rissel C, Lesjak M, Ward J. Cardiovascular risk factors among Arabic-speaking patients attending Arabic-speaking general practitioners in Sydney, Australia: opportunities for intervention. Ethn Health. 1998;3:213–222. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1998.9961863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thow AM, Waters AM. AIHW 2005. Diabetes in culturally and linguistically diverse Australians. Cat. No. CVD 30. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Punnose J, Agarwal MM, Bin-Uthman S. Type 2 diabetes mellitus among children and adolescents in Al-Ain: a case series. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11:788–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Al-Agha A, Ocheltree A, Shata N. Prevalence of hyperinsulinism, type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome among Saudi overweight and obese pediatric patients. Minerva Pediatr. 2012;64:623–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ali BA, Abdallah ST, Abdallah AM, Hussein MM. The Frequency of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus among Diabetic Children in El Minia Governorate, Egypt. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013;13:399–403. doi: 10.12816/0003262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Osman H, Elsadek N, Abdullah M. Type 2 diabetes in Sudanese children and adolescents. Sudan J Paediatr. 2013;13:17–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ehtisham S, Barrett TG, Shaw NJ. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in UK children--an emerging problem. Diabet Med. 2000;17:867–871. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Al-Rubeaan K, Abu El-Asrar AM, Youssef AM, Subhani SN, Ahmad NA, Al-Sharqawi AH, Alguwaihes A, Alotaibi MS, Al-Ghamdi A, Ibrahim HM. Diabetic retinopathy and its risk factors in a society with a type 2 diabetes epidemic: a Saudi National Diabetes Registry-based study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93:e140–e147. doi: 10.1111/aos.12532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hajar S, Al Hazmi A, Wasli M, Mousa A, Rabiu M. Prevalence and causes of blindness and diabetic retinopathy in Southern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2015;36:449–455. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.4.10371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Al-Rubeaan K, Youssef AM, Subhani SN, Ahmad NA, Al-Sharqawi AH, Al-Mutlaq HM, David SK, AlNaqeb D. Diabetic nephropathy and its risk factors in a society with a type 2 diabetes epidemic: a Saudi National Diabetes Registry-based study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Al-Rubeaan K, Al Derwish M, Ouizi S, Youssef AM, Subhani SN, Ibrahim HM, Alamri BN. Diabetic foot complications and their risk factors from a large retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang DD, Bakhotmah BA, Hu FB, Alzahrani HA. Prevalence and correlates of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in a Saudi Arabic population: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Al-Adsani AM. Risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in Kuwaiti type 2 diabetic patients. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:579–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Al-Maskari F, El-Sadig M. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United Arab Emirates: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Ophthalmol. 2007;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Al-Salman RA, Al-Basri HA, Al-Sayyad AS, Hearnshaw HM. Prevalence and risk factors of albuminuria in Type 2 diabetes in Bahrain. J Endocrinol Invest. 2009;32:746–751. doi: 10.1007/BF03346530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Al-Mahroos F, Al-Roomi K. Diabetic neuropathy, foot ulceration, peripheral vascular disease and potential risk factors among patients with diabetes in Bahrain: a nationwide primary care diabetes clinic-based study. Ann Saudi Med. 2007;27:25–31. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2007.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bener A, Al-Laftah F, Al-Hamaq AO, Daghash M, Abdullatef WK. A study of diabetes complications in an endogamous population: an emerging public health burden. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2014;8:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Elshafei M, Gamra H, Khandekar R, Al Hashimi M, Pai A, Ahmed MF. Prevalence and determinants of diabetic retinopathy among persons ≥ 40 years of age with diabetes in Qatar: a community-based survey. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21:39–47. doi: 10.5301/ejo.2010.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Khandekar R, Al Lawatii J, Mohammed AJ, Al Raisi A. Diabetic retinopathy in Oman: a hospital based study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1061–1064. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.9.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Khandekar RB, Tirumurthy S, Al-Harby S, Moorthy NS, Amir I. Diabetic retinopathy and ocular co-morbidities among persons with diabetes at Sumail Hospital of Oman. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009;11:675–679. doi: 10.1089/dia.2009.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Al-Lawati JA, N Barakat M, Al-Zakwani I, Elsayed MK, Al-Maskari M, M Al-Lawati N, Mohammed AJ. Control of risk factors for cardiovascular disease among adults with previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus: a descriptive study from a middle eastern arab population. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2012;6:133–140. doi: 10.2174/1874192401206010133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Alrawahi AH, Rizvi SG, Al-Riyami D, Al-Anqoodi Z. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic nephropathy in omani type 2 diabetics in Al-dakhiliyah region. Oman Med J. 2012;27:212–216. doi: 10.5001/omj.2012.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Al-Akily SA, Bamashmus MA, Gunaid AA. Causes of visual impairment and blindness among Yemenis with diabetes: a hospital-based study. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17:831–837. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.11.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bamashmus MA, Gunaid AA, Khandekar RB. Diabetic retinopathy, visual impairment and ocular status among patients with diabetes mellitus in Yemen: a hospital-based study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57:293–298. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.53055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gunaid AA, El Khally FM, Hassan NA, Mukhtar el D. Demographic and clinical features of diabetes mellitus in 1095 Yemeni patients. Ann Saudi Med. 1997;17:402–409. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1997.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Al-Khawlani A, Atef ZA, Al-Ansi A. Macrovascular complications and their associated risk factors in type 2 diabetic patients in Sana’a city, Yemen. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:851–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rabiu MM, Al Bdour MD, Abu Ameerh MA, Jadoon MZ. Prevalence of blindness and diabetic retinopathy in northern Jordan. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2015;25:320–327. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Al-Bdour MD, Al-Till MI, Abu Samra KM. Risk Factors for Diabetic Retinopathy among Jordanian Diabetics. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2008;15:77–80. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.51997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Al-Till MI, Al-Bdour MD, Ajlouni KM. Prevalence of blindness and visual impairment among Jordanian diabetics. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2005;15:62–68. doi: 10.1177/112067210501500110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jbour AS, Jarrah NS, Radaideh AM, Shegem NS, Bader IM, Batieha AM, Ajlouni KM. Prevalence and predictors of diabetic foot syndrome in type 2 diabetes mellitus in Jordan. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:761–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Macky TA, Khater N, Al-Zamil MA, El Fishawy H, Soliman MM. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy in Egypt: a hospital-based study. Ophthalmic Res. 2011;45:73–78. doi: 10.1159/000314876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Assaad-Khalil SH, Zaki A, Abdel Rehim A, Megallaa MH, Gaber N, Gamal H, Rohoma KH. Prevalence of diabetic foot disorders and related risk factors among Egyptian subjects with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2015;9:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kahloun R, Jelliti B, Zaouali S, Attia S, Ben Yahia S, Resnikoff S, Khairallah M. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in diabetic patients in Tunisia, North Africa. Eye (Lond) 2014;28:986–991. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Elhwuegi AS, Darez AA, Langa AM, Bashaga NA. Cross-sectional pilot study about the health status of diabetic patients in city of Misurata, Libya. Afr Health Sci. 2012;12:81–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]