Abstract

Otitis media (OM) is an inflammation of the middle ear associated with infection. Despite appropriate therapy, acute OM (AOM) can progress to chronic suppurative OM (CSOM) associated with ear drum perforation and purulent discharge. The effusion prevents the middle ear ossicles from properly relaying sound vibrations from the ear drum to the oval window of the inner ear, causing conductive hearing loss. In addition, the inflammatory mediators generated during CSOM can penetrate into the inner ear through the round window. This can cause the loss of hair cells in the cochlea, leading to sensorineural hearing loss. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus are the most predominant pathogens that cause CSOM. Although the pathogenesis of AOM is well studied, very limited research is available in relation to CSOM. With the emergence of antibiotic resistance as well as the ototoxicity of antibiotics and the potential risks of surgery, there is an urgent need to develop effective therapeutic strategies against CSOM. This warrants understanding the role of host immunity in CSOM and how the bacteria evade these potent immune responses. Understanding the molecular mechanisms leading to CSOM will help in designing novel treatment modalities against the disease and hence preventing the hearing loss.

Introduction

Otitis media (OM) refers to a group of complex infectious and inflammatory diseases affecting the middle ear (Dickson, 2014). OM in general is very common, as studies show that around 80 % of children should have experienced at least one episode by their third birthday (Teele et al., 1989). OM has been broadly classified into two main types, acute and chronic. Acute OM (AOM) is characterized by the rapid onset of signs of inflammation, specifically bulging and possible perforation of the tympanic membrane, fullness and erythema, as well as symptoms associated with inflammation such as otalgia, irritability and fever (Pukander, 1983; Harkness & Topham, 1998). Despite appropriate antibiotic therapy, AOM may progress to chronic suppurative OM (CSOM) characterized by persistent drainage from the middle ear associated with a perforated ear drum (Wintermeyer & Nahata, 1994; Harkness & Topham, 1998). When examined by otoscope, the middle ear looks red and inflamed with purulent discharge in CSOM patients (Figs 1 and 2). It is one of the most common chronic infectious diseases worldwide especially affecting children (Roland, 2002; Verhoeff et al., 2006). Hearing impairment is one of the most common sequelae of CSOM (Aarhus et al., 2015). The resultant hearing loss can have a negative impact on a child's speech development, education and behaviour (Olatoke et al., 2008; Khairi Md Daud et al., 2010). Mortality due to complications of CSOM is typically higher than other types of OM (Yorgancilar et al., 2013a; Qureishi et al., 2014). Intracranial complications like brain abscess and meningitis are the most common causes of death in CSOM patients (Dubey et al., 2010; Chew et al., 2012; Sun & Sun, 2014).

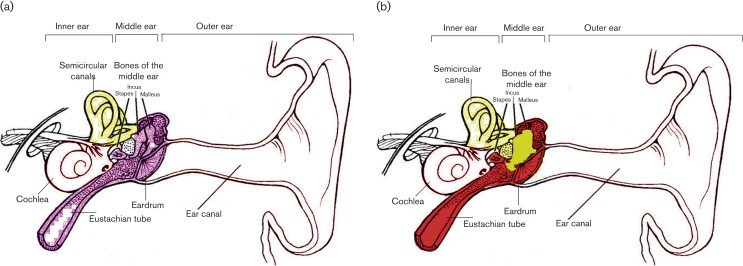

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the ear under normal and CSOM conditions. (a) Under normal conditions, the middle ear cavity is clear and empty. (b) In contrast, the middle ear becomes red and inflamed with the presence of fluid under CSOM conditions. The red colour denotes inflammation, while yellow indicates fluid during CSOM.

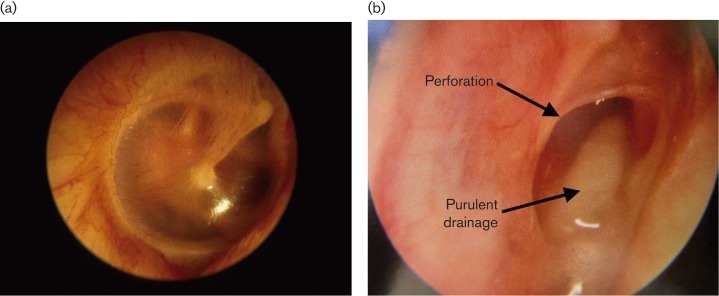

Fig. 2.

Otoscopic examination of the ear. (a) A normal ear from a healthy individual shows an intact eardrum and no fluid. (b) In CSOM patients, there is tympanic membrane perforation and purulent discharge.

In this article, the recent scientific advancements in epidemiology, microbiology, pathogenesis, treatment and effect of CSOM on hearing loss are reviewed. There are only a few studies available in relation to understanding the pathogenesis of CSOM (Table 1). The present review is intended to draw the attention to the fact that there is an urgent need to conduct studies on the pathogenic mechanisms of CSOM in order to identify novel therapeutic targets beyond the antibiotic therapy. A better understanding of the underlying mechanisms and, ultimately, the discovery of more effective therapies would result in decreased healthcare costs and improved quality of life for CSOM patients.

Table 1. Pathophysiological findings in CSOM patients.

| Findings | References |

|---|---|

| Biofilm formation in the middle ear of CSOM patients | Saunders et al. (2011); Lampikoski et al. (2012); Kaya et al. (2013); Khosravi et al. (2014); Gu et al., (2014) |

| Increased levels of IL-8 chemokine in middle ear effusion of CSOM patients | Elmorsy et al. (2010) |

| Increased transcript and protein levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and IFN-γ inflammatory cytokines in the middle ear mucosa of CSOM patients | Si et al. (2014) |

| Temporal bone erosion | Yorgancilar et al. (2013a, b) |

| Ossicular chain disruption | Varshney et al. (2010) |

| Hearing loss in CSOM patients | Paparella et al. (1984); Kolo et al. (2012); Luntz et al. (2013); Aarhus et al. (2014) |

Incidence and epidemiology

CSOM usually develops in the first years of life but can persist during adulthood. The disease affects 65–330 million people worldwide, mainly in developing countries. It has been estimated that there are 31 million new cases of CSOM per year, with 22.6 % in children less than 5 years old (Monasta et al., 2012). The populations with the highest reported prevalence of CSOM are the Inuits of Alaska, Canada and Greenland, American Indians and Australian Aborigines (7–46 %) (Bluestone, 1998; Coates et al., 2002; Couzos et al., 2003). Intermediate prevalence has been reported in the South Pacific Islands, Africa, Korea, India and Saudi Arabia, ranging from 1 to 6 % (Rupa et al., 1999; Zakzouk & Hajjaj, 2002). A prospective population-based longitudinal cohort study among children aged 0 to 4 years demonstrated a cumulative incidence rate of CSOM of 14 % in Greenland (Koch et al., 2011). However, earlier studies have reported CSOM incidence rates of 19 and 20 % among Greenlandic children aged 3–8 years (Pedersen and Zachau-Christiansen, 1986; Homøe et al., 1996). These studies show that CSOM is highly prevalent in Greenlandic Inuits and appears very early in life, on average before 1 year of age. The risk factors that predispose children to CSOM in Greenland include attending childcare centres, having a mother who reported a history of purulent ear discharge, having smokers in the household, a high burden of upper respiratory tract infections and being Inuit (Koch et al., 2011). Although CSOM is still prevalent in developed countries, very few studies are available regarding this disease. The exact incidence of CSOM in the USA is not well documented: 70 % of US children have at least one acute middle ear infection before 3 years of age, constituting a major risk factor for the development of CSOM (Kraemer et al., 1984). In the USA, CSOM has been documented to occur most often in certain ethnic groups, with an estimated prevalence of 12 % in Eskimo and 8 % in American Indian children and less frequently in the white and black population (Fairbanks, 1981; Kenna et al., 1986). For the latter two groups, the exact incidence has not been documented. It has been observed that males and females are equally affected, but the cholesteatomatous form is more common among males (Matanda et al., 2005). Additional epidemiological studies are required to highlight the incidence of CSOM in developed countries.

Microbiology

The most common cause of OM is bacterial infection of the middle ear. AOM is predominantly caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis (Sierra et al., 2011; Qureishi et al., 2014). However, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus are the most common aerobic microbial isolates in patients with CSOM, followed by Proteus vulgaris and Klebsiella pneumoniae (Table 2) (Sattar et al., 2012; Aduda et al., 2013; Prakash et al., 2013). A number of studies from different countries including India, Nepal, Singapore and Nigeria have reported that P. aeruginosa is the most common pathogen that causes CSOM, followed by S. aureus (Yeo et al., 2007; Sharma et al., 2010; Dayasena et al., 2011; Madana et al., 2011; Afolabi et al., 2012; Ahn et al., 2012; Asish et al., 2013). However, studies from Pakistan (Gilgit), Iran and Saudi Arabia reported S. aureus as the most predominant pathogen, followed by P. aeruginosa (Ettehad et al., 2006; Mariam et al., 2013; Ahmad et al., 2013; Ahmed et al., 2013). The difference in the various studies could be due to the differences in the patient population studied and geographical variation. A cross-sectional study of bacterial microbiota in middle ear, adenoid and tonsil specimens from a paediatric patient with chronic serous OM utilizing 16S rRNA gene-based pyrosequencing analysis revealed Pseudomonas spp. as the most common pathogen present in the middle ear, whereas Streptococcus spp. dominated the tonsil microbiota at relative abundance rates of 82.7 and 69.2 %, respectively (Liu et al., 2011). On the other hand, the adenoid microbiota was dominated by multiple bacteria including Streptococaceae, Fusobacteriaceae, Pasteurellaceae and Pseudomonadaceae. P. aeruginosa and S. aureus can enter the middle ear through the external canal. P. aeruginosa can thrive well in the ear environment and is difficult to eradicate. It has been proposed that P. aeruginosa evades the host defence mechanism by taking advantage of a shell of surrounding damaged epithelium that causes decreased blood circulation to the area (Pollack, 1988). P. aeruginosa damages the tissues, interferes with normal body defences and inactivates antibiotics by various enzymes and toxins (Gellatly & Hancock, 2013). Bacteroides spp., Clostridium spp., Peptococcus spp., Peptostreptococcus spp., Prevetolla melaninogenica and Fusobacterium spp. are anaerobic pathogens that can cause CSOM (Table 2) (Verhoeff et al., 2006; Prakash et al., 2013). It is possible that some of these pathogens may be just the normal microbial flora harbouring the middle ear instead of causative agents. However, no studies are available reporting the normal microflora of the middle ear. Therefore, further studies are warranted to characterize the normal microflora of the middle ear, which will help in differentiating normal ear flora from the pathogens that cause CSOM.

Table 2. A list of micro-organisms isolated from CSOM patients.

CSOM can also be characterized by co-infections with more than one type of bacterial and viral pathogen (Vartiainen & Vartiainen, 1996; Bakaletz, 2010). Fungi have also been identified in cultures from patients with CSOM (Ibekwe et al., 1997; Khanna et al., 2000; Prakash et al., 2013; Asish et al., 2014; Juyal et al., 2014). However, the presence of fungi can be due to the treatment with antibiotic ear drops, which causes suppression of bacterial flora and the subsequent emergence of fungal flora (Schrader & Isaacson, 2003). This probably increases the incidence of fungal superinfection, and even the less virulent fungi become more opportunistic. Furthermore, there has been much disparity on the rate of isolation of fungi from CSOM patients (Table 2). This variation can be attributed to the climatic conditions, as the moist and humid environment favours the prevalence of fungal infections of the ear.

Pathogenesis

CSOM is considered a multifactorial disease resulting from a complex series of interactions between environmental, bacterial, host and genetic risk factors (Rye et al., 2012; Li et al., 2013). It is important to identify the genes that contribute to CSOM susceptibility, which will provide insights into the biological complexity of this disease and ultimately contribute to improve the methods of prevention and treatment (Allen et al., 2014). Innate host immune mechanisms such as the TLR4/MyD88 pathway are particularly important in eliciting protective immune responses against bacteria (Hernandez et al., 2008). On the other hand, the transforming growth factor-β pathway helps in balancing the adverse outcome of an exaggerated pro-inflammatory response (Leichtle et al., 2011). The roles of these pathways have been extensively studied in AOM; however, no studies are available in relation to CSOM.

Bacterial biofilms have gained attention in the pathogenesis of CSOM. Biofilms are resistant to antibiotics and other antimicrobial compounds (Stewart & Costerton, 2001; Hall-Stoodley & Stoodley, 2009; Mah, 2012; Alhede et al., 2014; Jolivet-Gougeon & Bonnaure-Mallet, 2014; Römling et al., 2014). Therefore, they are difficult to eradicate and hence could lead to recurrent infections (Donelli & Vuotto, 2014; García-Cobos et al., 2014). In addition, biofilms attach firmly to damaged tissue, such as exposed osteitic bone and ulcerated middle ear mucosa, or to otological implants such as tympanostomy tubes, further aggravating the problem of eradication (Wang et al., 2014). Although biofilms have been demonstrated in the middle ear of CSOM patients, their precise role in the pathophysiology of the disease is yet to be determined (Saunders et al., 2011; Lampikoski et al., 2012; Kaya et al., 2013; Gu et al., 2014; Khosravi et al., 2014). Furthermore, the molecular mechanisms leading to biofilm formation in the middle ear during CSOM are also poorly understood.

Cytokines have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of OM. Most of the studies addressing the role of cytokines are in relation to AOM, and there are very limited studies available demonstrating the role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of CSOM. High levels of inflammatory cytokine such as IL-8 have been demonstrated in the middle ear effusion of CSOM patients (Elmorsy et al., 2010). IL-8 plays a role in the development of chronicity of OM and has also been related to bacterial growth. Increased mRNA as well as protein levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and IFN-γ have been found in the middle ear mucosa of CSOM patients compared with heathy individuals (Si et al., 2014). The upregulation of these pro-inflammatory cytokines can cause tissue damage as well as transition from acute to chronic OM. Additional studies are warranted to investigate the role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of CSOM.

Hearing loss

Hearing impairment is the most common sequela of CSOM (Aarhus et al., 2015). CSOM can cause conductive hearing loss (CHL) as well as sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). CHL results from the obstruction in the transmission of sound waves from the middle ear to the inner ear. CSOM is characterized by the presence of fluid (pus), which can hinder the conductance of sound to the inner ear. The amount of effusion in the middle ear has been directly correlated with the magnitude and severity of CHL (Wiederhold et al., 1980). CSOM is characterized by the presence of tympanic membrane perforation, which can hinder the conductance of sound to the inner ear. The degree to which hearing is compromised has also been demonstrated to be directly proportional to the damage caused to the structures of the middle ear (Yorgancilar et al., 2013b). In some cases of CSOM, there can be permanent hearing loss that can be attributed to irreversible tissue changes in the auditory cleft (Kaplan et al., 1996; Sharma et al., 2013). Chronic infection of the middle ear causes oedema of the middle ear lining and discharge, tympanic membrane perforation and possibly ossicular chain disruption, resulting in CHL ranging from 20 to 60 dB (Varshney et al., 2010).

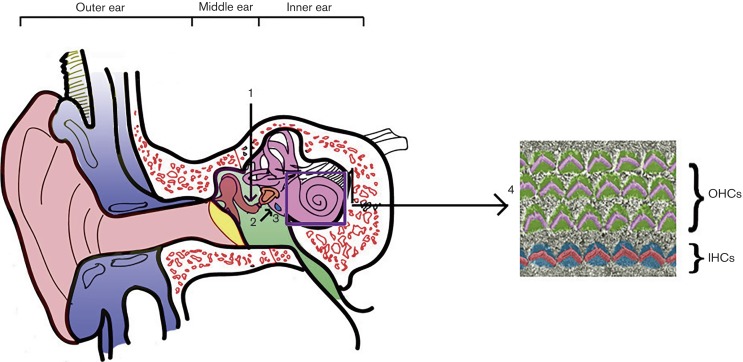

SNHL results either from inner ear damage (cochlea) or injury to the nerve pathways that relay signals from the inner ear to the brain. The cochlea in mammals has three rows of outer hair cells and one row of inner hair cells. The outer hair cells help in the amplification and tuning of sound waves, whereas inner hair cells are involved in converting the mechanical energy of sound into an electrical impulse to be relayed to the auditory nerve. Any damage to outer or inner hair cells can cause severe hearing impairment, which can be irreversible and permanent.

Recent studies have demonstrated that CSOM is able to cause SNHL in addition to CHL (Papp et al., 2003; da Costa et al., 2009; Kolo et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2014). Infection of the middle ear leads to the generation of inflammatory mediators such as nitric oxide and arachidonic acid metabolites (Table 3), which can cause functional as well as morphological changes in the auditory structures (Housley et al., 1988; Jung et al., 1992; Guo et al., 1994; Clerici et al., 1995; Jung et al., 2003). These inflammatory mediators can also penetrate the round window membrane and pass into the inner ear causing cochlear damage (Fig. 3) (Morizono & Tono, 1991; Penha & Escada, 2003; Juhn et al., 2008). The loss of outer and inner hair cells in the basal turn of the cochlea has been observed in CSOM patients (Huang et al., 1990; Cureoglu et al., 2004). The majority of SNHL in CSOM patients is in the high-frequency range and is unilateral (Jensen et al., 2013). A recent study has also shown that bacterial toxins found in the middle ear during CSOM can pass into the cochlea and result in cochlear pathology (Joglekar et al., 2010). These bacterial toxins can be exotoxins (proteins) produced by both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, or endotoxins (LPSs of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria). These infection-associated toxins might cause direct damage to hair cells, especially those at the cochlear base where the hair cells are sensitive to high-frequency sounds (Kolo et al., 2012). A significant loss of outer and inner hair cells, as well as significant atrophy of the stria vascularis in the basal turn of the cochlea, has been observed in CSOM patients. The basal turn of the cochlea also demonstrated severe pathological changes that were consistent with the high-frequency SNHL in CSOM patients (Cureoglu et al., 2004; Joglekar et al., 2010).

Table 3. List of inflammatory mediators generated in the middle ear in response to microbial infection.

| Inflammatory mediators | Possible mode of action | References |

|---|---|---|

| Nitric oxide | Destroys hair cells | Huang et al. (1990); Jung et al. (2003) |

| Reactive oxygen species | Morphological changes like cell membrane rupture, blebbing and cell body shortening | Clerici et al. (1995) |

| Arachidonic acid metabolites (prostaglandin and leukotriene) | Alteration in cochlear blood flow, hair cell damage | Jung et al. (1992) |

| Histamine | Interferes with the efferent innervations of the outer hair cells | Housley et al. (1988) |

| Cytokines | Damage to hair cells | Juhn et al. (2008) |

| Bacterial toxins | Block Na/K ATPase and change the ion concentration of endolymph; damage to hair cells | Guo et al. (1994) |

Fig. 3.

OM and inner ear damage. The bacterial infection of the middle ear (1) leads to the generation of inflammatory mediators (2) that can penetrate from the round window (3) to the inner ear, leading to damage to outer (OHCs) and inner (IHCs) auditory hair cells (4).

SNHL in CSOM patients is often demonstrated by higher bone conduction (BC) thresholds in the audiogram. BC thresholds in the healthy and CSOM ear differed by at least 20 dB at all of the measured frequencies (Luntz et al., 2013). In a multi-centre study, 58 % of 874 patients with unilateral CSOM presented with SNHL of more than 15 dB in the affected ear (Paparella et al., 1984). El-Sayed (1998) showed that, in 218 patients, the BC thresholds over a range of frequencies were increased by 9.2 to 14.1 dB in CSOM ears, with a mean difference between CSOM and normal ears of more than 10 dB in 39 % of patients and of 20 dB or more in 12 % of patients. Greater differences at 4000 Hz (5 dB) than at 500, 1000 or 2000 Hz (3 dB) were observed in 145 patients with unilateral CSOM (Eisenman & Parisier, 1998). Significant differences in BC between chronic OM and normal ears in 344 patients, ranging from 0.6 dB at 500 Hz to 3.7 dB at 4000 Hz for all frequencies have also been observed (Redaelli de Zinis et al., 2005). da Costa et al. (2009) reported, in 150 patients, a BC difference of 5 dB between chronic OM and normal ears at 1000 and 2000 Hz, increasing to 10 dB at 3000 and 4000 Hz. The percentage of CSOM patients with higher BC thresholds tended to increase with age (Yoshida et al., 2009). The site and size of the tympanic membrane perforation have been correlated with the degree of hearing loss, with posterior perforations having a greater decibel level loss, probably as a result of loss of protection of the round window membrane from impinging sound pressure waves (Vaidya et al., 2014). It was suggested that all measures for an early cure, including surgery, should be considered promptly to prevent hearing loss in CSOM patients (Yoshida et al., 2009).

Treatment

The current primary treatment modality for CSOM is a combination of aural toilet and topical antimicrobial drops. Systemic oral or parenteral antibiotics, although an option, are less commonly used due to the fact that topical antibiotics in combination with aural toilet are able to achieve significantly higher tissue concentrations than systemic antibiotics (in the order of 100–1000 times greater). Surgery, in the way of mastoidectomy, was traditionally the mainstay of therapy. However, retrospective studies have suggested that mastoidectomy is not superior to more conservative therapies such as aural toilet and topical and systemic antibiotics for uncomplicated CSOM. Reconstruction of the tympanic membrane or tympanoplasty is another surgical technique often used for persistent perforations after the active infection of CSOM has been treated. In addition, surgical eradication of cholesteatoma is indicated in chronic cholesteatomatous OM (CCOM).

Aural toilet

The term aural toilet refers to keeping the chronically draining ear clean and dry as much as possible. Techniques include in-office mopping with cotton swabs, suctioning to remove discharge and debris, and placing an ear wick to stent open an oedematous canal (Doshi et al., 2009). Some practitioners use various powders to help dry the ear, many of which include topical antibiotics. One popular example is otic insufflation powder, which consists of a mixture of chloramphenicol, sulfamethoxazol, and amphotericin B (Fungizone). There is no consensus on how often to perform aural toilet or when to use insufflation powder, but in the case of previous treatment failure, the former can be performed daily, if feasible. Some practitioners recommend at least two to three times a week, depending on the severity and duration of symptoms (Dagan et al., 1992; Daniel, 2012).

A small number of randomized controlled studies have shown that aural toilet is not effective as monotherapy and should be used in combination with medical therapy, ideally ototopical antibiotics in the treatment of CSOM. Otorrhoea resolved frequently in groups treated with a combination of aural toilet, topical and systemic antibiotics, and topical boric acid compared with aural toilet alone or with no specific therapy (Melaku & Lulseged, 1999; Choi et al., 2010). Another trial demonstrated that children with CSOM treated with aural toilet and intravenous antibiotics improved more frequently compared with aural toilet alone (Fliss et al., 1990).

Ototopical antibiotics

Antibiotic drops in combination with aural toilet are the mainstay of therapy for CSOM and have been shown to be the most effective in randomized controlled trials. Quinolones are the most commonly used topical antibiotics in the USA due to their established effectiveness (Aslan et al., 1998; Ohyama et al., 1999). Topical quinolones carry a low side-effect profile and are superior to aminoglycosides (Nwabuisi & Ologe, 2002). Quinolones are particularly effective against P. aeruginosa and do not carry a potential side effect of cochleotoxicity and vestibulotoxicity, which are attributed to aminoglycosides (Dohar et al., 1996). A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that ciprofloxacin is more effective compared with aminoglycoside, and another study showed the efficacy of ofloxacin topical antibiotic over oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid in resolving otorrhoea (Yuen et al., 1994; Couzos et al., 2003).

Corticosteroids are sometimes used in combination with quinolones for CSOM but are not well studied. Combination ear drops can be prescribed when there is inflammation of the external auditory canal or middle ear mucosa, or when granulation tissue is present. Dexamethasone is often used in combination with ciprofloxacin for these conditions (Shinkwin et al., 1996; Hannley et al., 2000; Acuin, 2007).

There are several alternative topical solutions that can be used in settings in which antibiotic drops are not readily available. These are used in developed countries but are much more common in resource-limited settings due to their low cost and availability. Some of these include acetic acid, aluminium acetate (Burrow's solution), or combinations of these (Domeboro's solution), and iodine-based antiseptic solutions. Few studies exist comparing these solutions with ototopical quinolones. However, one retrospective study showed that aluminium acetate solution was as effective as gentamicin in resolving otorrhoea (Clayton et al., 1990). Also, 57 % of patients in another study had resolution of otorrhoea after acetic acid irrigations to their affected ear three times weekly for 3 weeks, in the absence of any other therapy (Aminifarshidmehr, 1996). Aluminium acetate can potentially be even more effective than acetic acid because of its increased activity against many of the pathogens in vitro (Thorp et al., 1998). Povidone–iodine-based antiseptic solution has broad-spectrum action against many organisms that can colonize the middle ear – bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa. One randomized controlled trial demonstrated that povidone–iodine had the same efficacy as ciprofloxacin drops in resolving otorrhoea (Jaya et al., 2003). Additionally, it was shown that bacterial resistance rates were much lower for iodine solution than for ciprofloxacin (Jaya et al., 2003). Further large-scale studies are warranted to confirm the safety and efficacy of these topical agents in CSOM.

Systemic antibiotics

Upon failure of primary treatment to resolve otorrhoea after 3 weeks of therapy, alternative measures must be considered. Oral antibiotics are a second-line therapy for CSOM. Systemic therapy has not been as effective as direct delivery of topical antibiotics due to the inability to achieve effective concentrations in the infected tissues of the middle ear. Multiple factors affect drug efficacy including bioavailability, organism resistance, scarring of middle ear tissues and decreased vascularization of middle ear mucosa in chronic disease (Macfadyen et al., 2006; Daniel, 2012). Topical agents such as quinolones are the drug of choice for the second-line therapy (Lang et al., 1992; Kristo & Buljan, 2011). These, however, must be used with caution in children because of the potential for growth problems related to tendons and joints, and should be reserved for organisms that are otherwise resistant to other therapies or when there is no safe alternative. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (Augmentin) or erythromycin/sulfafurazole (Pediazole) are other antibiotics that are recommended for children.

Intravenous antibiotics have demonstrated efficacy against CSOM but are not the first-line treatment option for several reasons. Due to the risk of systemic side effects and increased potential to breed antibiotic resistance, intravenous antibiotics should be used as the last-line medical option for CSOM patients. When possible, antibiotics should be culture directed, and an infectious disease consultation should be sought, when available. Because the most common organisms encountered in CSOM are P. aeruginosa and meticillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), penicillin-based antibiotics and macrolides have very limited efficacy, as organism resistance rates are high (Brook, 1994; Campos et al., 1995; Park et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2010). The most effective antibiotics for P. aeruginosa and MRSA are quinolones, such as ciprofloxacin, and a combination of vancomycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim), respectively (Park et al., 2008). Other common antibiotics that can be used against Pseudomonas spp. include imipenem and aztreonam (Somekh & Cordova, 2000). In one study, P. aeruginosa isolates resistant to ciprofloxacin also demonstrated high resistance to aminoglycosides, pipercillin-tazobactam, and ceftazidime (Jang & Park, 2004), making these drugs less-than-ideal candidates for intravenous therapy. Despite the activity against the most common infectious agents, intravenous antibiotics are certainly not a panacea in CSOM. The cure rate of patients treated with cultured-directed intravenous vancomycin in MRSA CSOM was similar to those treated with aural toilet and topical acetic acid and aluminium acetate solutions (Choi et al., 2010). This further demonstrates the concept that ototopical treatment combined with aggressive aural toilet is the preferred primary therapeutic modality in CSOM. Systemic antibiotics should be used for various degrees of primary treatment failure or when intracranial complications ensue during CSOM.

Surgery

Surgery should be considered as a last-line resort after maximal medical therapy has been exhausted for cases of CSOM that are particularly recalcitrant or recurrent. Surgery in the form of tympanomastoidectomy is also indicated in cases of CSOM in which there are complications, some of which could potentially be life threatening, such as significant hearing loss, facial nerve palsy, subperiosteal abscess, petrositis, dural venous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, cerebral abscess and labyrinthine fistula, among others (Kangsanarak et al., 1993; Matin et al., 1997; Taylor & Berkowitz, 2004; Matanda et al., 2005; Zanetti & Nassif, 2006; Dubey & Larawin, 2007; Akinpelu et al., 2008; Mostafa et al., 2009). Chronic cholesteatomatous OM requires surgery, usually in the form of tympanomastoidectomy in order to eradicate cholesteatoma, a usual underlying cause of chronic infection (Shirazi et al., 2006). However, some retrospective studies show that there is no difference in outcomes of graft success rate or post-operative hearing with regard to whether mastoidectomy is performed in addition to tympanoplasty (Balyan et al., 1997; Mishiro et al., 2001). Mastoidectomy may be indicated to reduce the burden of disease in cases with abscess formation in the mastoid, tympanoplasty or recalcitrant disease (Collins et al., 2003; Angeli et al., 2006).

Tympanoplasty can be performed anywhere from 6 to 12 months after resolution of the infection. A large percentage of perforations will heal on their own after resolution of infection, but in those that do not, tympanoplasty is indicated to improve hearing and to help prevent recurrence of infection by closing off the middle ear space. In addition, patients must practice dry ear precautions to help decrease the rate of recurrent infection and otorrhoea (Bluestone, 1988).

Recurrent disease

Recurrent CSOM (patients who develop CSOM, recover from disease and develop chronic infection again) is due to one or a combination of several factors. These include treatment with oral antibiotics alone, treatment with non-antibiotic drops, non-compliance with the treatment regimen, infection with resistant bacteria such as P. aeruginosa or MRSA, and the presence of cholesteatoma. Disease can also be particularly recalcitrant and recurrent in patients with a distorted ear anatomy or who are prone to infections.

Recurrent disease can be managed by ototopical antibiotic therapy during the active infection and by several additional methods to prevent relapse. The most conservative of these measures are dry ear precautions and aural toilet (Bluestone, 1988). Prophylactic antibiotics have been used but are not recommended to prevent recurrent disease, as this may lead to antibiotic resistance and difficulty with treatment in the future (Arguedas et al., 1994). Upon resolution of the active infection, tympanoplasty may be performed to help prevent chronic drainage by sealing off the middle ear, assisting in proper Eustachian tube function, and preventing microbial entry into the middle ear space (Rickers et al., 2006; Shim et al., 2010). When a child develops recurrent disease, computed tomographic imaging of the temporal bones should be sought to evaluate for potential cholesteatoma or mastoid abscess formation, as these are surgically correctable causes of recurrent or persistent CSOM.

Conclusions

CSOM is the most common chronic infectious disease worldwide. The factors underlying the pathogenesis of CSOM are still poorly understood. There is an urgent need to focus research studies in the area of CSOM, which will open up avenues to design novel therapeutic studies against CSOM and hence prevent hearing loss. Medical and surgical options are limited, with side effects and risks, and sometimes are not successful in eliminating disease. Topical antibiotics, which are the first-line therapy of choice, are limited only to those that are not potentially ototoxic. Additionally, surgery carries the risks of worsening hearing, as well as the potential for damage to the facial nerve and resulting facial nerve paresis.

It is likely that some of the factors involved in AOM may also be involved in CSOM; however, it is also possible that there are significant differences that need to be elucidated in further studies. There is a need to characterize the role of immunity (both innate and adaptive) as it pertains to the transition from AOM to CSOM. Establishing animal models of CSOM will help in elucidating the role of microbial biofilms and virulence factors, as well as host factors in the CSOM pathogenesis. These models will also help in evaluating the potency and efficacy of novel treatment strategies against CSOM. Recently, a mouse model of CSOM has been reported (Santa Maria et al., 2015) that can be explored to understand host–pathogen interactions during CSOM and the development of novel treatment modalities against the disease. Emerging new technologies such as systems biology approaches employing high-throughput multiomics techniques (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics) can be used to construct predictive models of the networks and dynamic interactions between the biological components of the complex host–pathogen system. Advances in sequencing technology have revolutionized pathogen biology and opened up unprecedented opportunities to understand the pathologies of intractable infectious diseases. Development of computational methods to probe these ‘ultra-fast’ ‘omics’ data to discover new pathogens or deconstruct the molecular network underlying host–pathogen interactions is increasingly being pursued, and is likely to catalyse the development of new clinical approaches for tackling CSOM. Bacteriophages can be a viable option for the treatment of bacterial infections due to the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains (Samson et al., 2013; Viertel et al., 2014; Qadir, 2015). Bacteriophages are viruses that specifically and uniquely destroy bacteria. Bacteriophages are considered safe, economical, self-replicating and effective bactericidal agents (Golkar et al., 2014; Jassim and Limoges, 2014). In a small controlled clinical trial with 24 patients, bacteriophages provided efficient protection and demonstrated efficacy against chronic otitis media caused by chemoresistant P. aeruginosa (Wright et al., 2009). Further large-scale randomized double-blind clinical trials are warranted to explore the translational potential of bacteriophages against CSOM. In addition, studies are warranted to characterize middle ear and inner ear interactions during CSOM pathogenesis. This is especially true regarding the role of inflammatory mediators that appear to be capable of crossing the round window membrane and causing potentially permanent hearing loss via damage to auditory hair cells. The identification of genetic and prognostic markers will help in predicting CSOM-susceptible individuals and possibly even novel therapeutic strategies. Understanding the molecular mechanisms leading to CSOM will provide avenues to design novel treatment modalities against the disease and consequent hearing loss.

Acknowledgements

The research work in Dr Liu's laboratory is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders grants R01 DC05575, R01 DC01246 and R01 DC012115. We are thankful to April Mann for the critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Aarhus L., Tambs K., Kvestad E., Engdahl B. (2015). Childhood otitis media: a cohort study with 30-year follow-up of hearing (The HUNT Study) Ear Hear 36 302–308 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acuin J. (2007). Chronic suppurative otitis media BMJ Clin Evid 2007 0507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aduda D. S., Macharia I. M., Mugwe P., Oburra H., Farragher B., Brabin B., Mackenzie I. (2013). Bacteriology of chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) in children in Garissa district, Kenya: a point prevalence study Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 77 1107–1111 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.04.011 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afolabi O. A., Salaudeen A. G., Ologe F. E., Nwabuisi C., Nwawolo C. C. (2012). Pattern of bacterial isolates in the middle ear discharge of patients with chronic suppurative otitis media in a tertiary hospital in north central Nigeria Afr Health Sci 12 362–367 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M. K., Mir A., Jan M., Imran R. Shah, Farmanullah G. S., Latif A., (2013). Prevalence of bacteria in chronic suppurative otitis media patients and their sensitivity patterns against various antibiotics in human population of Gilgit Pakistan J Zool 45 1647–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S. (2013). Antibiotics in chronic suppurative otitis media: A bacteriologic study Egyptian Journal of Ear, Nose, Throat and Allied Sciences 14 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J. H., Kim M. N., Suk Y. A., Moon B. J. (2012). Preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative results of bacterial culture from patients with chronic suppurative otitis media Otol Neurotol 33 54–59 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31823dbc70 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinpelu O. V., Amusa Y. B., Komolafe E. O., Adeolu A. A., Oladele A. O., Ameye S. A. (2008). Challenges in management of chronic suppurative otitis media in a developing country J Laryngol Otol 122 16–20 10.1017/S0022215107008377 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhede M., Bjarnsholt T., Givskov M., Alhede M. (2014). Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: mechanisms of immune evasion Adv Appl Microbiol 86 1–40 10.1016/B978-0-12-800262-9.00001-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen E. K., Manichaikul A., Sale M. M. (2014). Genetic contributors to otitis media: agnostic discovery approaches Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 14 411 10.1007/s11882-013-0411-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminifarshidmehr N. (1996). The management of chronic suppurative otitis media with acid media solution Am J Otol 17 24–25 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angeli S. I., Kulak J. L., Guzmán J. (2006). Lateral tympanoplasty for total or near-total perforation: prognostic factors Laryngoscope 116 1594–1599 10.1097/01.mlg.0000232495.77308.46 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arguedas A., Loaiza C., Herrera J. F., Mohs E. (1994). Antimicrobial therapy for children with chronic suppurative otitis media without cholesteatoma Pediatr Infect Dis J 13 878–882 10.1097/00006454-199410000-00006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asish J., Amar M., Vinay H., Sreekantha, Avinash S. S., Amareshar M. (2013). To study the bacteriological and mycological profile of chronic suppurative otitis media patients and their antibiotic sensitivity pattern Int J Pharma Bio Sci 4 186–199. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan A., Altuntas A., Titiz A., Arda H. N., Nalca Y. (1998). A new dosage regimen for topical application of ciprofloxacin in the management of chronic suppurative otitis media Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 118 883–885 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70291-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakaletz L. O. (2010). Immunopathogenesis of polymicrobial otitis media J Leukoc Biol 87 213–222 10.1189/jlb.0709518 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balyan F. R., Celikkanat S., Aslan A., Taibah A., Russo A., Sanna M. (1997). Mastoidectomy in noncholesteatomatous chronic suppurative otitis media: is it necessary? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 117 592–595 10.1016/S0194-5998(97)70038-X . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone C. D. (1988). Current management of chronic suppurative otitis media in infants and children Pediatr Infect Dis J 7 (Suppl)), S137–S140 10.1097/00006454-198811001-00003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone C. D. (1998). Epidemiology and pathogenesis of chronic suppurative otitis media: implications for prevention and treatment Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 42 207–223 10.1016/S0165-5876(97)00147-X . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook I. (1994). Management of chronic suppurative otitis media: superiority of therapy effective against anaerobic bacteria Pediatr Infect Dis J 13 188–193 10.1097/00006454-199403000-00004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook I. (2008). The role of anaerobic bacteria in chronic suppurative otitis media in children: implications for medical therapy Anaerobe 14 297–300 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2008.12.002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos M. A., Arias A., Rodriguez C., Dorta A., Betancor L., Lopez-Aguado D., Sierra A. (1995). Etiology and therapy of chronic suppurative otitis J Chemother 7 427–431 10.1179/joc.1995.7.5.427 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew Y. K., Cheong J. P., Khir A., Brito-Mutunayagam S., Prepageran N. (2012). Complications of chronic suppurative otitis media: a left otogenic brain abscess and a right mastoid fistula Ear Nose Throat J 91 428–430 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. G., Park K. H., Park S. N., Jun B. C., Lee D. H., Yeo S. W. (2010). The appropriate medical management of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in chronic suppurative otitis media Acta Otolaryngol 130 42–46 10.3109/00016480902870522 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton M. I., Osborne J. E., Rutherford D., Rivron R. P. (1990). A double-blind, randomized, prospective trial of a topical antiseptic versus a topical antibiotic in the treatment of otorrhoea Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 15 7–10 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1990.tb00425.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici W. J., DiMartino D. L., Prasad M. R. (1995). Direct effects of reactive oxygen species on cochlear outer hair cell shape in vitro Hear Res 84 30–40 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00010-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates H. L., Morris P. S., Leach A. J., Couzos S. (2002). Otitis media in Aboriginal children: tackling a major health problem Med J Aust 177 177–178 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins W. O., Telischi F. F., Balkany T. J., Buchman C. A. (2003). Pediatric tympanoplasty: effect of contralateral ear status on outcomes Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 129 646–651 10.1001/archotol.129.6.646 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couzos S., Lea T., Mueller R., Murray R., Culbong M. (2003). Effectiveness of ototopical antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media in Aboriginal children: a community-based, multicentre, double-blind randomised controlled trial Med J Aust 179 185–190 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cureoglu S., Schachern P. A., Paparella M. M., Lindgren B. R. (2004). Cochlear changes in chronic otitis media Laryngoscope 114 622–626 10.1097/00005537-200404000-00006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa S. S., Rosito L. P., Dornelles C. (2009). Sensorineural hearing loss in patients with chronic otitis media Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 266 221–224 10.1007/s00405-008-0739-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan R., Fliss D. M., Einhorn M., Kraus M., Leiberman A. (1992). Outpatient management of chronic suppurative otitis media without cholesteatoma in children Pediatr Infect Dis J 11 542–546 10.1097/00006454-199207000-00007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel S. J. (2012). Topical treatment of chronic suppurative otitis media Curr Infect Dis Rep 14 121–127 10.1007/s11908-012-0246-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayasena R., Dayasiri M., Jayasuriya C., Perera D. (2011). Aetiological agents in chronic suppurative otitis media in Sri Lanka Australas Med J 4 101–104 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb T., Ray D. (2012). A study of the bacteriological profile of chronic suppurative otitis media in agartala Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 64 326–329 10.1007/s12070-011-0323-6 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson G. (2014). Acute otitis media Prim Care 41 11–18 10.1016/j.pop.2013.10.002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohar J. E., Kenna M. A., Wadowsky R. M. (1996). In vitro susceptibility of aural isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to commonly used ototopical antibiotics Am J Otol 17 207–209 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelli G., Vuotto C. (2014). Biofilm-based infections in long-term care facilities Future Microbiol 9 175–188 10.2217/fmb.13.149 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi J., Coulson C., Williams J., Kuo M. (2009). Aural toilet in infants: how we do it Clin Otolaryngol 34 67–68 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2008.01866.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey S. P., Larawin V. (2007). Complications of chronic suppurative otitis media and their management Laryngoscope 117 264–267 10.1097/01.mlg.0000249728.48588.22 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey S. P., Larawin V., Molumi C. P. (2010). Intracranial spread of chronic middle ear suppuration Am J Otolaryngol 31 73–77 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.10.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenman D. J., Parisier S. C. (1998). Is chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma associated with neurosensory hearing loss? Am J Otol 19 20–25 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed Y. (1998). Bone conduction impairment in uncomplicated chronic suppurative otitis media Am J Otolaryngol 19 149–153 10.1016/S0196-0709(98)90079-5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmorsy S., Shabana Y. K., Raouf A. A., Naggar M. E., Bedir T., Taher S., Fath-Aallah M. (2010). The role of IL-8 in different types of otitis media and bacteriological correlation J Int Adv Otol 6 269–273. [Google Scholar]

- Ettehad G. H., Refahi S., Nemmati A., Pirzadeh A., Daryani A. (2006). Microbial and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns from patients with chronic otitis media in Ardebil Int J Trop Med 1 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks D. N. (1981). Antimicrobial therapy for chronic suppurative otitis media Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 90 58–62 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliss D. M., Dagan R., Houri Z., Leiberman A. (1990). Medical management of chronic suppurative otitis media without cholesteatoma in children J Pediatr 116 991–996 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80666-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Cobos S., Moscoso M., Pumarola F., Arroyo M., Lara N., Pérez-Vázquez M., Aracil B., Oteo J., García E., Campos J. (2014). Frequent carriage of resistance mechanisms to β-lactams and biofilm formation in Haemophilus influenzae causing treatment failure and recurrent otitis media in young children J Antimicrob Chemother 69 2394–2399 10.1093/jac/dku158 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellatly S. L., Hancock R. E. (2013). Pseudomonas aeruginosa: new insights into pathogenesis and host defenses Pathog Dis 67 159–173 10.1111/2049-632X.12033 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golkar Z., Bagasra O., Pace D. G. (2014). Bacteriophage therapy: a potential solution for the antibiotic resistance crisis J Infect Dev Ctries 8 129–136 10.3855/jidc.3573 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X., Keyoumu Y., Long L., Zhang H. (2014). Detection of bacterial biofilms in different types of chronic otitis media Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 271 2877–2883 10.1007/s00405-013-2766-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Wu Y., Chen W., Lin J. (1994). Endotoxic damage to the stria vascularis: the pathogenesis of sensorineural hearing loss secondary to otitis media? J Laryngol Otol 108 310–313 10.1017/S0022215100126623 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Stoodley L., Stoodley P. (2009). Evolving concepts in biofilm infections Cell Microbiol 11 1034–1043 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01323.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannley M. T., Denneny J. C., III, Holzer S. S. (2000). Use of ototopical antibiotics in treating 3 common ear diseases Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 122 934–940 10.1067/mhn.2000.107813 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness P., Topham J. (1998). Classification of otitis media Laryngoscope 108 1539–1543 10.1097/00005537-199810000-00021 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez M., Leichtle A., Pak K., Ebmeyer J., Euteneuer S., Obonyo M., Guiney D. G., Webster N. J., Broide D. H., other authors (2008). Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 is required for the resolution of otitis media J Infect Dis 198 1862–1869 10.1086/593213 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homøe P., Christensen R. B., Bretlau P. (1996). Prevalence of otitis media in a survey of 591 unselected Greenlandic children Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 36 215–230 10.1016/0165-5876(96)01351-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housley G. D., Norris C. H., Guth P. S. (1988). Histamine and related substances influence neurotransmission in the semicircular canal Hear Res 35 87–97 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90043-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Dulon D., Schacht J. (1990). Outer hair cells as potential targets of inflammatory mediators Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 148 35–38 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibekwe A. O., al Shareef Z., Benayam A. (1997). Anaerobes and fungi in chronic suppurative otitis media Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 106 649–652 10.1177/000348949710600806 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang C. H., Park S. Y. (2004). Emergence of ciprofloxacin-resistant pseudomonas in chronic suppurative otitis media Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 29 321–323 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00835.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jassim S. A., Limoges R. G. (2014). Natural solution to antibiotic resistance: bacteriophages ‘The Living Drugs’ World J Microbiol Biotechnol 30 2153–2170 10.1007/s11274-014-1655-7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaya C., Job A., Mathai E., Antonisamy B. (2003). Evaluation of topical povidone-iodine in chronic suppurative otitis media Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 129 1098–1100 10.1001/archotol.129.10.1098 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen R. G., Koch A., Homøe P. (2013). The risk of hearing loss in a population with a high prevalence of chronic suppurative otitis media Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 77 1530–1535 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.06.025 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joglekar S., Morita N., Cureoglu S., Schachern P. A., Deroee A. F., Tsuprun V., Paparella M. M., Juhn S. K. (2010). Cochlear pathology in human temporal bones with otitis media Acta Otolaryngol 130 472–476 10.3109/00016480903311252 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolivet-Gougeon A., Bonnaure-Mallet M. (2014). Biofilms as a mechanism of bacterial resistance Drug Discov Today Technol 11 49–56 10.1016/j.ddtec.2014.02.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhn S. K., Jung M. K., Hoffman M. D., Drew B. R., Preciado D. A., Sausen N. J., Jung T. T., Kim B. H., Park S. Y., other authors (2008). The role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of otitis media and sequelae Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 1 117–138 10.3342/ceo.2008.1.3.117 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T. T., Park Y. M., Miller S. K., Rozehnal S., Woo H. Y., Baer W. (1992). Effect of exogenous arachidonic acid metabolites applied on round window membrane on hearing and their levels in the perilymph Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 493 171–176 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung T. T., Llaurado R. J., Nam B. H., Park S. K., Kim P. D., John E. O. (2003). Effects of nitric oxide on morphology of isolated cochlear outer hair cells: possible involvement in sensorineural hearing loss Otol Neurotol 24 682–685 10.1097/00129492-200307000-00025 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juyal D., Negi V., Sharma M., Adekhandi S., Prakash R., Sharma N. (2014). Significance of fungal flora in chronic suppurative otitis media Ann Trop Med Public Health 7 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir M. S., Joarder A. H., Ekramuddaula F. M., Uddin M. M., Islam M. R., Habib M. A. (2012). Pattern of chronic suppurative otitis media Mymensingh Med J 21 270–275 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangsanarak J., Fooanant S., Ruckphaopunt K., Navacharoen N., Teotrakul S. (1993). Extracranial and intracranial complications of suppurative otitis media. Report of 102 cases J Laryngol Otol 107 999–1004 10.1017/S0022215100125095 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D. M., Fliss D. M., Kraus M., Dagan R., Leiberman A. (1996). Audiometric findings in children with chronic suppurative otitis media without cholesteatoma Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 35 89–96 10.1016/0165-5876(95)01283-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya E., Dag I., Incesulu A., Gurbuz M. K., Acar M., Birdane L. (2013). Investigation of the presence of biofilms in chronic suppurative otitis media, nonsuppurative otitis media, and chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma by scanning electron microscopy ScientificWorldJournal 2013 638715 10.1155/2013/638715 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenna M. A., Bluestone C. D., Reilly J. S., Lusk R. P. (1986). Medical management of chronic suppurative otitis media without cholesteatoma in children Laryngoscope 96 146–151 10.1288/00005537-198602000-00004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairi Md Daud M., Noor R. M., Rahman N. A., Sidek D. S., Mohamad A. (2010). The effect of mild hearing loss on academic performance in primary school children Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 74 67–70 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.10.013 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna V., Chander J., Nagarkar N. M., Dass A. (2000). Clinicomicrobiologic evaluation of active tubotympanic type chronic suppurative otitis media J Otolaryngol 29 148–153 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi Y., Ling L. C., Loke M. F., Shailendra S., Prepageran N., Vadivelu J. (2014). Determination of the biofilm formation capacity of bacterial pathogens associated with otorhinolaryngologic diseases in the Malaysian population Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 271 1227–1233 10.1007/s00405-013-2637-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A., Homøe P., Pipper C., Hjuler T., Melbye M. (2011). Chronic suppurative otitis media in a birth cohort of children in Greenland: population-based study of incidence and risk factors Pediatr Infect Dis J 30 25–29 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181efaa11 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolo E. S., Salisu A. D., Yaro A. M., Nwaorgu O. G. (2012). Sensorineural hearing loss in patients with chronic suppurative otitis media Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 64 59–62 10.1007/s12070-011-0251-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer M. J., Marshall S. G., Richardson M. A. (1984). Etiologic factors in the development of chronic middle ear effusions Clin Rev Allergy 2 319–328 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristo B., Buljan M. (2011). Microbiology of the chronic suppurative otitis media Med Glas (Zenica) 8 284–286 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampikoski H., Aarnisalo A. A., Jero J., Kinnari T. J. (2012). Mastoid biofilm in chronic otitis media Otol Neurotol 33 785–788 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318259533f . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R., Goshen S., Raas-Rothschild A., Raz A., Ophir D., Wolach B., Berger I. (1992). Oral ciprofloxacin in the management of chronic suppurative otitis media without cholesteatoma in children: preliminary experience in 21 children Pediatr Infect Dis J 11 925–929 10.1097/00006454-199211110-00004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichtle A., Lai Y., Wollenberg B., Wasserman S. I., Ryan A. F. (2011). Innate signaling in otitis media: pathogenesis and recovery Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 11 78–84 10.1007/s11882-010-0158-3 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. D., Hermansson A., Ryan A. F., Bakaletz L. O., Brown S. D., Cheeseman M. T., Juhn S. K., Jung T. T., Lim D. J., other authors (2013). Panel 4: Recent advances in otitis media in molecular biology, biochemistry, genetics, and animal models Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 148 E52–E63 10.1177/0194599813479772 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. M., Cosetti M. K., Aziz M., Buchhagen J. L., Contente-Cuomo T. L., Price L. B., Keim P. S., Lalwani A. K. (2011). The otologic microbiome: a study of the bacterial microbiota in a pediatric patient with chronic serous otitis media using 16SrRNA gene-based pyrosequencing Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 137 664–668 10.1001/archoto.2011.116 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luntz M., Yehudai N., Haifler M., Sigal G., Most T. (2013). Risk factors for sensorineural hearing loss in chronic otitis media Acta Otolaryngol 133 1173–1180 10.3109/00016489.2013.814154 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfadyen C. A., Acuin J. M., Gamble C. (2006). Systemic antibiotics versus topical treatments for chronically discharging ears with underlying eardrum perforations Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1), CD005608 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madana J., Yolmo D., Kalaiarasi R., Gopalakrishnan S., Sujatha S. (2011). Microbiological profile with antibiotic sensitivity pattern of cholesteatomatous chronic suppurative otitis media among children Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 75 1104–1108 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.05.025 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah T. F. (2012). Biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance Future Microbiol 7 1061–1072 10.2217/fmb.12.76 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariam, Khalil A., Ahsanullah M., Mehtab J., Raja I., Gulab S., Farmanullah, Abdul L. (2013). Prevalence of bacteria in chronic suppurative otitis media patients and their sensitivity patterns against various antibiotics in human population of Gilgit Pak J Zool 45 1647–1653. [Google Scholar]

- Matanda R. N., Muyunga K. C., Sabue M. J., Creten W., Van de Heyning P. (2005). Chronic suppurative otitis media and related complications at the University Clinic of Kinshasa B-ENT 1 57–62 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matin M. A., Khan A. H., Khan F. A., Haroon A. A. (1997). A profile of 100 complicated cases of chronic suppurative otitis media J R Soc Health 117 157–159 10.1177/146642409711700306 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melaku A., Lulseged S. (1999). Chronic suppurative otitis media in a children's hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Ethiop Med J 37 237–246 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishiro Y., Sakagami M., Takahashi Y., Kitahara T., Kajikawa H., Kubo T. (2001). Tympanoplasty with and without mastoidectomy for non-cholesteatomatous chronic otitis media Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 258 13–15 10.1007/PL00007516 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monasta L., Ronfani L., Marchetti F., Montico M., Vecchi Brumatti L., Bavcar A., Grasso D., Barbiero C., Tamburlini G. (2012). Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates PLoS One 7 e36226 10.1371/journal.pone.0036226 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morizono T., Tono T. (1991). Middle ear inflammatory mediators and cochlear function Otolaryngol Clin North Am 24 835–843 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa B. E., El Fiky L. M., El Sharnouby M. M. (2009). Complications of suppurative otitis media: still a problem in the 21st century ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 71 87–92 10.1159/000191472 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwabuisi C., Ologe F. E. (2002). Pathogenic agents of chronic suppurative otitis media in Ilorin, Nigeria East Afr Med J 79 202–205 10.4314/eamj.v79i4.8879 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama M., Furuta S., Ueno K., Katsuda K., Nobori T., Kiyota R., Miyazaki Y. (1999). Ofloxacin otic solution in patients with otitis media: an analysis of drug concentrations Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 125 337–340 10.1001/archotol.125.3.337 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatoke F., Ologe F. E., Nwawolo C. C., Saka M. J. (2008). The prevalence of hearing loss among schoolchildren with chronic suppurative otitis media in Nigeria, and its effect on academic performance Ear Nose Throat J 87 E19 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orji F. T., Dike B. O. (2015). Observations on the current bacteriological profile of chronic suppurative otitis media in South eastern Nigeria Ann Med Health Sci Res 5 124–128 10.4103/2141-9248.153622 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paparella M. M., Morizono T., Le C. T., Choo Y. B., Mancini F., Liden G., Sipila P., Kim C. S. (1984). Sensorineural hearing loss in otitis media Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 93 623–629 10.1177/000348948409300616 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp Z., Rezes S., Jókay I., Sziklai I. (2003). Sensorineural hearing loss in chronic otitis media Otol Neurotol 24 141–144 10.1097/00129492-200303000-00003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D. C., Lee S. K., Cha C. I., Lee S. O., Lee M. S., Yeo S. G. (2008). Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus from otorrhea in chronic suppurative otitis media and comparison with results of all isolated Staphylococci Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 27 571–577 10.1007/s10096-008-0478-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen C. B., Zachau-Christiansen B. (1986). Otitis media in Greenland children: acute, chronic and secretory otitis media in three- to eight-year-olds J Otolaryngol 15 332–335 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penha R., Escada P. (2003). Interrelations between the middle and inner ear in otitis media Int Tinnitus J 9 87–91 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack M. (1988). Special role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in chronic suppurative otitis media Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 97 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash R., Juyal D., Negi V., Pal S., Adekhandi S., Sharma M., Sharma N. (2013). Microbiology of chronic suppurative otitis media in a tertiary care setup of Uttarakhand state, India N Am J Med Sci 5 282–287 10.4103/1947-2714.110436 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukander J. (1983). Clinical features of acute otitis media among children Acta Otolaryngol 95 117–122 10.3109/00016488309130924 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qadir M. I. (2015). Review: phage therapy: a modern tool to control bacterial infections Pak J Pharm Sci 28 265–270 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureishi A., Lee Y., Belfield K., Birchall J. P., Daniel M. (2014). Update on otitis media – prevention and treatment Infect Drug Resist 7 15–24 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redaelli de Zinis L. O., Campovecchi C., Parrinello G., Antonelli A. R. (2005). Predisposing factors for inner ear hearing loss association with chronic otitis media Int J Audiol 44 593–598 10.1080/14992020500243737 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickers J., Petersen C. G., Pedersen C. B., Ovesen T. (2006). Long-term follow-up evaluation of mastoidectomy in children with non-cholesteatomatous chronic suppurative otitis media Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 70 711–715 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.09.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland P. S. (2002). Chronic suppurative otitis media: a clinical overview Ear Nose Throat J 81 (Suppl) 1), 8–10 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Römling U., Kjelleberg S., Normark S., Nyman L., Uhlin B. E., Åkerlund B. (2014). Microbial biofilm formation: a need to act J Intern Med 276 98–110 10.1111/joim.12242 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupa V., Jacob A., Joseph A. (1999). Chronic suppurative otitis media: prevalence and practices among rural South Indian children Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 48 217–221 10.1016/S0165-5876(99)00034-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rye M. S., Blackwell J. M., Jamieson S. E. (2012). Genetic susceptibility to otitis media in childhood Laryngoscope 122 665–675 10.1002/lary.22506 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson J. E., Magadán A. H., Sabri M., Moineau S. (2013). Revenge of the phages: defeating bacterial defences Nat Rev Microbiol 11 675–687 10.1038/nrmicro3096 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa Maria P. L., Kim S., Varsak Y. k., Yang Y. P. (2015). Heparin binding-epidermal growth factor-like growth factor for the regeneration of chronic tympanic membrane perforations in mice Tissue Eng Part A 21 1483–1494 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0474 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattar A., Alamgir A., Hussain Z., Sarfraz S., Nasir J., Badar-e-Alam (2012). Bacterial spectrum and their sensitivity pattern in patients of chronic suppurative otitis media J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 22 128–129 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J., Murray M., Alleman A. (2011). Biofilms in chronic suppurative otitis media and cholesteatoma: scanning electron microscopy findings Am J Otolaryngol 32 32–37 10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.09.010 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader N., Isaacson G. (2003). Fungal otitis externa – its association with fluoroquinolone eardrops Pediatrics 111 1123 10.1542/peds.111.5.1123 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Rehan H. S., Goyal A., Jha A. K., Upadhyaya S., Mishra S. C. (2004). Bacteriological profile in chronic suppurative otitis media in Eastern Nepal Trop Doct 34 102–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K., Aggarwal A., Khurana P. M. (2010). Comparison of bacteriology in bilaterally discharging ears in chronic suppurative otitis media Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 62 153–157 10.1007/s12070-010-0021-9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K., Manjari M., Salaria N. (2013). Middle ear cleft in chronic otitis media: a clinicohistopathological study Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 65 (Suppl. 3), 493–497 10.1007/s12070-011-0372-x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim H. J., Park C. H., Kim M. G., Lee S. K., Yeo S. G. (2010). A pre- and postoperative bacteriological study of chronic suppurative otitis media Infection 38 447–452 10.1007/s15010-010-0048-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkwin C. A., Murty G. E., Simo R., Jones N. S. (1996). Per-operative antibiotic/steroid prophylaxis of tympanostomy tube otorrhoea: chemical or mechanical effect? J Laryngol Otol 110 531–533 10.1017/S0022215100134188 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi M. A., Muzaffar K., Leonetti J. P., Marzo S. (2006). Surgical treatment of pediatric cholesteatomas Laryngoscope 116 1603–1607 10.1097/01.mlg.0000233248.03276.9b . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si Y., Zhang Z. G., Chen S. J., Zheng Y. Q., Chen Y. B., Liu Y., Jiang H., Feng L. Q., Huang X. (2014). Attenuated TLRs in middle ear mucosa contributes to susceptibility of chronic suppurative otitis media Hum Immunol 75 771–776 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.05.009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra A., Lopez P., Zapata M. A., Vanegas B., Castrejon M. M., Deantonio R., Hausdorff W. P., Colindres R. E. (2011). Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae as primary causes of acute otitis media in colombian children: a prospective study BMC Infect Dis 11 4 10.1186/1471-2334-11-4 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somekh E., Cordova Z. (2000). Ceftazidime versus aztreonam in the treatment of pseudomonal chronic suppurative otitis media in children Scand J Infect Dis 32 197–199 10.1080/003655400750045330 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart P. S., Costerton J. W. (2001). Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms Lancet 358 135–138 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05321-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Sun J. (2014). Intracranial complications of chronic otitis media Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 271 2923–2926 10.1007/s00405-013-2778-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. F., Berkowitz R. G. (2004). Indications for mastoidectomy in acute mastoiditis in children Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 113 69–72 10.1177/000348940411300115 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teele D. W., Klein J. O., Rosner B. (1989). Epidemiology of otitis media during the first seven years of life in children in greater Boston: a prospective, cohort study J Infect Dis 160 83–94 10.1093/infdis/160.1.83 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorp M. A., Kruger J., Oliver S., Nilssen E. L., Prescott C. A. (1998). The antibacterial activity of acetic acid and Burow's solution as topical otological preparations J Laryngol Otol 112 925–928 10.1017/S0022215100142100 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya S., Sharma J. K., Singh G. (2014). Study of outcome of tympanoplasties in relation to size and site of tympanic membrane perforation Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 66 341–346 10.1007/s12070-014-0733-3 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney S., Nangia A., Bist S. S., Singh R. K., Gupta N., Bhagat S. (2010). Ossicular chain status in chronic suppurative otitis media in adults Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 62 421–426 10.1007/s12070-010-0116-3 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartiainen E., Vartiainen J. (1996). Effect of aerobic bacteriology on the clinical presentation and treatment results of chronic suppurative otitis media J Laryngol Otol 110 315–318 10.1017/S0022215100133535 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeff M., van der Veen E. L., Rovers M. M., Sanders E. A., Schilder A. G. (2006). Chronic suppurative otitis media: a review Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 70 1–12 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.08.021 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viertel T. M., Ritter K., Horz H. P. (2014). Viruses versus bacteria - novel approaches to phage therapy as a tool against multidrug-resistant pathogens J Antimicrob Chemother 69 2326–2336 10.1093/jac/dku173 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishwanath S., Mukhopadhyay C., Prakash R., Pillai S., Pujary K., Pujary P. (2012). Chronic suppurative otitis media: optimizing initial antibiotic therapy in a tertiary care setup Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 64 285–289 10.1007/s12070-011-0287-6 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. C., Hamood A. N., Saadeh C., Cunningham M. J., Yim M. T., Cordero J. (2014). Strategies to prevent biofilm-based tympanostomy tube infections Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 78 1433–1438 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.05.025 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederhold M. L., Zajtchuk J. T., Vap J. G., Paggi R. E. (1980). Hearing loss in relation to physical properties of middle ear effusions Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 89 185–189 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermeyer S. M., Nahata M. C. (1994). Chronic suppurative otitis media Ann Pharmacother 28 1089–1099 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright A., Hawkins C. H., Anggård E. E., Harper D. R. (2009). A controlled clinical trial of a therapeutic bacteriophage preparation in chronic otitis due to antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa; a preliminary report of efficacy Clin Otolaryngol 34 349–357 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01973.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. J., Kim T. S., Shim B. S., Ahn J. H., Chung J. W., Yoon T. H., Park H. J. (2014). Abnormal CT findings are risk factors for otitis media-related sensorineural hearing loss Ear Hear 35 375–378 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000015 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo S. G., Park D. C., Hong S. M., Cha C. I., Kim M. G. (2007). Bacteriology of chronic suppurative otitis media – a multicenter study Acta Otolaryngol 127 1062–1067 10.1080/00016480601126978 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorgancilar E., Yildirim M., Gun R., Bakir S., Tekin R., Gocmez C., Meric F., Topcu I. (2013a). Complications of chronic suppurative otitis media: a retrospective review Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 270 69–76 10.1007/s00405-012-1924-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorgancilar E., Akkus Z., Gun R., Yildirim M., Bakir S., Kinis V., Meric F., Topcu I. (2013b). Temporal bone erosion in patients with chronic suppurative otitis media B-ENT 9 17–22 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H., Miyamoto I., Takahashi H. (2009). Is sensorineural hearing loss with chronic otitis media due to infection or aging in older patients? Auris Nasus Larynx 36 269–273 10.1016/j.anl.2008.07.004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen P. W., Lau S. K., Chau P. Y., Hui Y., Wong S. F., Wong S., Wei W. I. (1994). Ofloxacin eardrop treatment for active chronic suppurative otitis media: prospective randomized study Am J Otol 15 670–673 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakzouk S. M., Hajjaj M. F. (2002). Epidemiology of chronic suppurative otitis media among Saudi children – a comparative study of two decades Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 62 215–218 10.1016/S0165-5876(01)00616-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti D., Nassif N. (2006). Indications for surgery in acute mastoiditis and their complications in children Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 70 1175–1182 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.12.002 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]