Abbreviations

- 3-MA

3-methyladenine

- ABC

avidin-biotin peroxidase complex

- AIM

Atg8-family interacting motif

- ALIS

aggresome-like induced structures

- Ape1

aminopeptidase I

- ARN

autophagy regulatory network

- ASFV

African swine fever virus

- Atg

autophagy-related

- AV

autophagic vacuole

- BDI

bright detail intensity

- CASA

chaperone-assisted selective autophagy

- CLEAR

coordinated lysosomal enhancement and regulation

- CLEM

correlative light and electron microscopy

- CMA

chaperone-mediated autophagy

- cryo-SXT

cryo-soft X-ray tomography

- Cvt

cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting

- DAMP

danger/damage-associated molecular pattern

- DQ-BSA

dequenched bovine serum albumin

- e-MI

endosomal microautophagy

- EBSS

Earle's balanced salt solution

- EM

electron microscopy

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorter

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- GAP

GTPase activating protein

- GBP

guanylate binding protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus type 1

- HKP

housekeeping protein

- HSV-1

herpes simplex virus type 1

- Hyp-PDT

hypericin-based photodynamic therapy

- ICD

immunogenic cell death

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IMP

intramembrane particle

- LAMP2

lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2

- LAP

LC3-associated phagocytosis

- LIR

LC3-interacting region

- LN

late nucleophagy

- MAP1LC3/LC3, microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3; MDC

monodansylcadaverine

- MEC

mammary epithelial cell

- mRFP

monomeric red fluorescent protein

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- MTOR

mechanistic target of rapamycin (serine/threonine kinase)

- MVB

multivesicular body

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- ncRNA

noncoding RNA

- NET

neutrophil extracellular trap

- NVJ

nucleus-vacuole junction

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- PAS

phagophore assembly site

- PDT

photodynamic therapy

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PMN

piecemeal microautophagy of the nucleus

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride

- POF

postovulatory follicle

- PSSM

position-specific scoring matrix

- PtdIns3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PtdIns3P

phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate

- PTM

posttranslational modification

- PVM

parasitophorus vacuole membrane

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- RBC

red blood cell

- RCBs

Rubisco-containing bodies

- Rluc

Renilla reniformis luciferase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SD

standard deviation

- SKL

serine-lysine-leucine (a peroxisome targeting signal)

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- tfLC3

tandem fluorescent LC3

- TORC1

TOR complex I

- TR-FRET

time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- TVA

tubulovesicular autophagosome

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- UPS

ubiquitin-proteasome system

- V-ATPase

vacuolar-type H+-ATPase

- xLIR

extended LIR-motif

In 2008 we published the first set of guidelines for standardizing research in autophagy. Since then, research on this topic has continued to accelerate, and many new scientists have entered the field. Our knowledge base and relevant new technologies have also been expanding. Accordingly, it is important to update these guidelines for monitoring autophagy in different organisms. Various reviews have described the range of assays that have been used for this purpose. Nevertheless, there continues to be confusion regarding acceptable methods to measure autophagy, especially in multicellular eukaryotes.

For example, a key point that needs to be emphasized is that there is a difference between measurements that monitor the numbers or volume of autophagic elements (e.g., autophagosomes or autolysosomes) at any stage of the autophagic process versus those that measure flux through the autophagy pathway (i.e., the complete process including the amount and rate of cargo sequestered and degraded). In particular, a block in macroautophagy that results in autophagosome accumulation must be differentiated from stimuli that increase autophagic activity, defined as increased autophagy induction coupled with increased delivery to, and degradation within, lysosomes (in most higher eukaryotes and some protists such as Dictyostelium) or the vacuole (in plants and fungi). In other words, it is especially important that investigators new to the field understand that the appearance of more autophagosomes does not necessarily equate with more autophagy. In fact, in many cases, autophagosomes accumulate because of a block in trafficking to lysosomes without a concomitant change in autophagosome biogenesis, whereas an increase in autolysosomes may reflect a reduction in degradative activity. It is worth emphasizing here that lysosomal digestion is a stage of autophagy and evaluating its competence is a crucial part of the evaluation of autophagic flux, or complete autophagy.

Here, we present a set of guidelines for the selection and interpretation of methods for use by investigators who aim to examine macroautophagy and related processes, as well as for reviewers who need to provide realistic and reasonable critiques of papers that are focused on these processes. These guidelines are not meant to be a formulaic set of rules, because the appropriate assays depend in part on the question being asked and the system being used. In addition, we emphasize that no individual assay is guaranteed to be the most appropriate one in every situation, and we strongly recommend the use of multiple assays to monitor autophagy. Along these lines, because of the potential for pleiotropic effects due to blocking autophagy through genetic manipulation, it is imperative to target by gene knockout or RNA interference more than one autophagy-related protein. In addition, some individual Atg proteins, or groups of proteins, are involved in other cellular pathways implying that not all Atg proteins can be used as a specific marker for an autophagic process. In these guidelines, we consider these various methods of assessing autophagy and what information can, or cannot, be obtained from them. Finally, by discussing the merits and limits of particular assays, we hope to encourage technical innovation in the field.

Introduction

Many researchers, especially those new to the field, need to determine which criteria are essential for demonstrating autophagy, either for the purposes of their own research, or in the capacity of a manuscript or grant review.1 Acceptable standards are an important issue, particularly considering that each of us may have his/her own opinion regarding the answer. Unfortunately, the answer is in part a “moving target” as the field evolves.2 This can be extremely frustrating for researchers who may think they have met those criteria, only to find out that the reviewers of their papers have different ideas. Conversely, as a reviewer, it is tiresome to raise the same objections repeatedly, wondering why researchers have not fulfilled some of the basic requirements for establishing the occurrence of an autophagic process. In addition, drugs that potentially modulate autophagy are increasingly being used in clinical trials, and screens are being carried out for new drugs that can modulate autophagy for therapeutic purposes. Clearly it is important to determine whether these drugs are truly affecting autophagy, and which step(s) of the process is affected, based on a set of accepted criteria. Accordingly, we describe here a basic set of contemporary guidelines that can be used by researchers to plan and interpret their experiments, by clinicians to evaluate the literature with regard to autophagy-modulating therapies, and by both authors and reviewers to justify or criticize an experimental approach.

Several fundamental points must be kept in mind as we establish guidelines for the selection of appropriate methods to monitor autophagy.2 Importantly, there are no absolute criteria for determining autophagic status that are applicable in every biological or experimental context. This is because some assays are inappropriate, problematic or may not work at all in particular cells, tissues or organisms.3-6 For example, autophagic responses to drugs may be different in transformed versus nontransformed cells, and in confluent versus nonconfluent cells, or in cells grown with or without glucose.4 In addition, these guidelines are likely to evolve as new methodologies are developed and current assays are superseded. Nonetheless, it is useful to establish guidelines for acceptable assays that can reliably monitor autophagy in many experimental systems. It is important to note that in this set of guidelines the term “autophagy” generally refers to macroautophagy; other autophagy-related processes are specifically designated when appropriate.

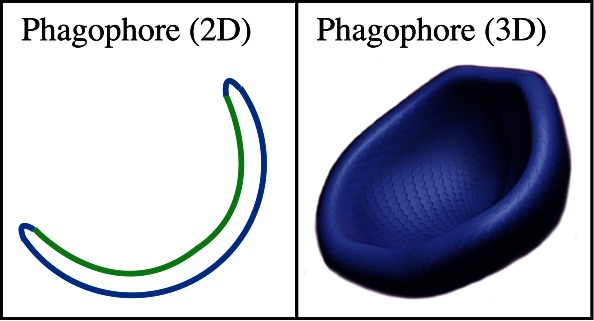

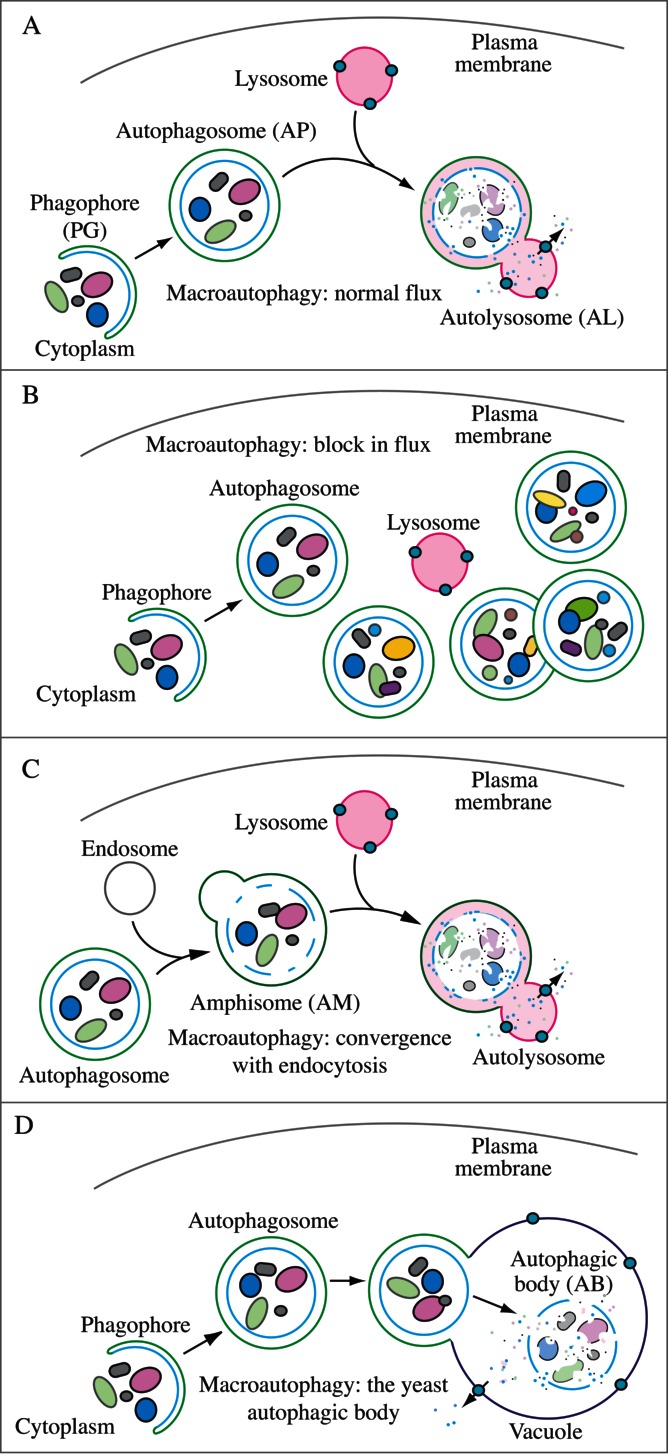

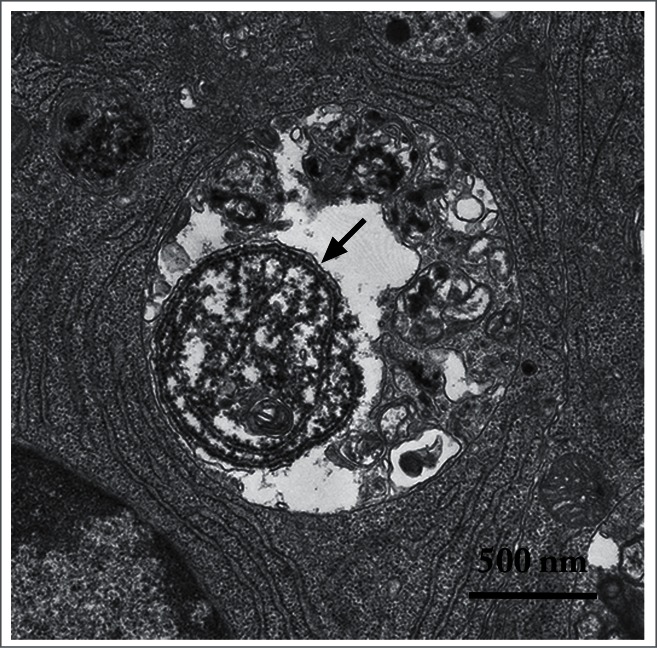

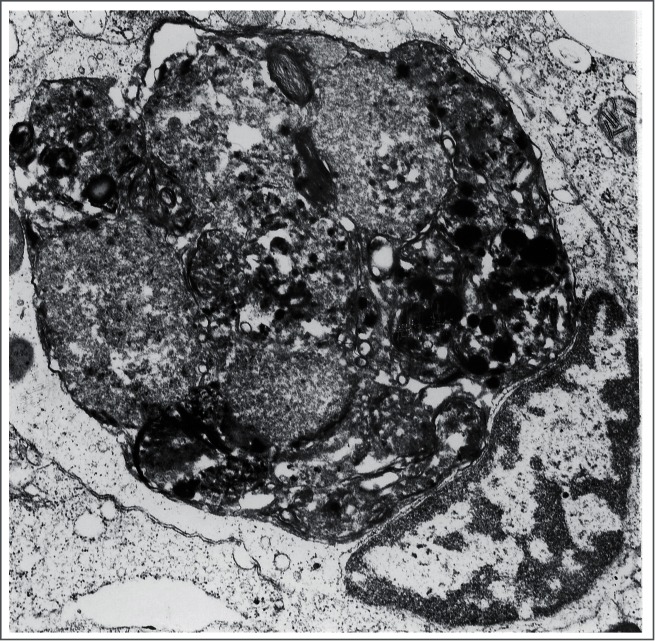

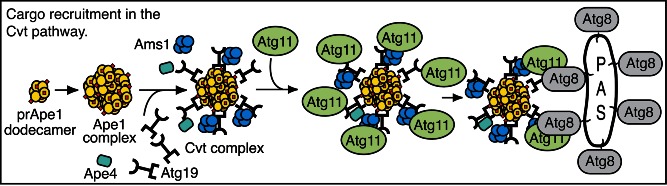

For the purposes of this review, the autophagic compartments (Fig. 1) are referred to as the sequestering (pre-autophagosomal) phagophore (PG; previously called the isolation or sequestration membrane5,6),7 the autophagosome (AP),8 the amphisome (AM; generated by the fusion of autophagosomes with endosomes),9 the lysosome, the autolysosome (AL; generated by fusion of autophagosomes or amphisomes with a lysosome), and the autophagic body (AB; generated by fusion and release of the internal autophagosomal compartment into the vacuole in fungi and plants). Except for cases of highly stimulated autophagic sequestration (Fig. 2), autophagic bodies are not seen in animal cells, because lysosomes/autolysosomes are typically smaller than autophagosomes.6,8,10 One critical point is that autophagy is a highly dynamic, multi-step process. Like other cellular pathways, it can be modulated at several steps, both positively and negatively. An accumulation of autophagosomes (measured by transmission electron microscopy [TEM] image analysis,11 as green fluorescent protein [GFP]-MAP1LC3 [GFP-LC3] puncta, or as changes in the amount of lipidated LC3 [LC3-II] on a western blot), could, for example, reflect a reduction in autophagosome turnover,12-14 or the inability of turnover to keep pace with increased autophagosome formation (Fig. 1B).15 For example, inefficient fusion with endosomes and/or lysosomes, or perturbation of the transport machinery,16 would inhibit autophagosome maturation to amphisomes or autolysosomes (Fig. 1C), whereas decreased flux could also be due to inefficient degradation of the cargo once fusion has occurred.17 Moreover, GFP-LC3 puncta and LC3 lipidation can reflect the induction of a different/modified pathway such as LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP),18 and the noncanonical destruction pathway of the paternal mitochondria after fertilization.19,20

Figure 1.

Schematic model demonstrating the induction of autophagosome formation when turnover is blocked versus normal autophagic flux, and illustrating the morphological intermediates of macroautophagy. (A) The initiation of autophagy includes the formation of the phagophore, the initial sequestering compartment, which expands into an autophagosome. Completion of the autophagosome is followed by fusion with lysosomes and degradation of the contents, allowing complete flux, or flow, through the entire pathway. This is a different outcome than the situation shown in (B) where induction results in the initiation of autophagy, but a defect in autophagosome turnover due, for example, to a block in fusion with lysosomes or disruption of lysosomal functions will result in an increased number of autophagosomes. In this scenario, autophagy has been induced, but there is no or limited autophagic flux. (C) An autophagosome can fuse with an endosome to generate an amphisome, prior to fusion with the lysosome. (D) Schematic drawing showing the formation of an autophagic body in fungi. The large size of the fungal vacuole relative to autophagosomes allows the release of the single-membrane autophagic body within the vacuole lumen. In cells that lack vacuolar hydrolase activity, or in the presence of inhibitors that block hydrolase activity, intact autophagic bodies accumulate within the vacuole lumen and can be detected by light microscopy. The lysosome of most higher eukaryotes is too small to allow the release of an autophagic body.

Figure 2.

An autophagic body in a large lysosome of a mouse epithelial cell from a seminal vesicle in vitro. The arrow shows the single limiting membrane covering the sequestered rough ER. Image provided by A.L. Kovács.

Accordingly, the use of autophagy markers such as LC3-II must be complemented by assays to estimate overall autophagic flux, or flow, to permit a correct interpretation of the results. That is, autophagic activity includes not just the increased synthesis or lipidation of Atg8/LC3 (LC3 is the mammalian homolog of yeast Atg8), or an increase in the formation of autophagosomes, but, most importantly, flux through the entire system, including lysosomes or the vacuole, and the subsequent release of the breakdown products. Therefore, autophagic substrates need to be monitored dynamically over time to verify that they have reached the lysosome/vacuole, and whether or not they are degraded. By responding to perturbations in the extracellular environment, cells tune the autophagic flux to meet intracellular metabolic demands. The impact of autophagic flux on cell death and human pathologies therefore demands accurate tools to measure not only the current flux of the system, but also its capacity,21 and its response time, when exposed to a defined stress.22

One approach to evaluate autophagic flux is to measure the rate of general protein breakdown by autophagy.6,23 It is possible to arrest the autophagic flux at a given point, and then record the time-dependent accumulation of an organelle, an organelle marker, a cargo marker, or the entire cargo at the point of blockage; however, this approach, sometimes incorrectly referred to as autophagic flux, does not assess complete autophagy because the experimental block is usually induced (at least in part) by inhibiting lysosomal proteolysis, which precludes the evaluation of lysosomal functions. In addition, the latter assumes there is no feedback of the accumulating structure on its own rate of formation.24 In an alternative approach, one can follow the time-dependent decrease of an autophagy-degradable marker (with the caveat that the potential contribution of other proteolytic systems and of new protein synthesis need to be experimentally addressed). In theory, these nonautophagic processes can be assessed by blocking autophagic sequestration at specific steps of the pathway (e.g., blocking further induction or nucleation of new phagophores) and by measuring the decrease of markers distal to the block point.12,14,25 The key issue is to differentiate between the often transient accumulation of autophagosomes due to increased induction, and their accumulation due to inefficient clearance of sequestered cargos by both measuring the levels of autophagosomes at static time points and by measuring changes in the rates of autophagic degradation of cellular components.17 Both processes have been used to estimate “autophagy,” but unless the experiments can relate changes in autophagosome quantity to a direct or indirect measurement for autophagic flux, the results may be difficult to interpret.26 A general caution regarding the use of the term “steady state” is warranted at this point. It should not be assumed that an autophagic system is at steady state in the strict biochemical meaning of this term, as this implies that the level of autophagosomes does not change with time, and the flux through the system is constant. In these guidelines, we use steady state to refer to the baseline range of autophagic flux in a system that is not subjected to specific perturbations that increase or decrease that flux.

Autophagic flux refers to the entire process of autophagy, which encompasses the inclusion (or exclusion) of cargo within the autophagosome, the delivery of cargo to lysosomes (via fusion of the latter with autophagosomes or amphisomes) and its subsequent breakdown and release of the resulting macromolecules back into the cytosol (this may be referred to as productive or complete autophagy). Thus, increases in the level of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)-modified Atg8/LC3 (Atg8–PE/LC3-II), or even the appearance of autophagosomes, are not measures of autophagic flux per se, but can reflect the induction of autophagic sequestration and/or inhibition of autophagosome or amphisome clearance. Also, it is important to realize that while formation of Atg8–PE/LC3-II appears to correlate with the induction of autophagy, we do not know, at present, the actual mechanistic relationship between Atg8–PE/LC3-II formation and the rest of the autophagic process; indeed, it may be possible to execute “self-eating” in the absence of LC3-II.27

As a final note, we also recommend that researchers refrain from the use of the expression “percent autophagy” when describing experimental results, as in “The cells displayed a 25% increase in autophagy.” Instead, it is appropriate to indicate that the average number of GFP-Atg8/LC3 puncta per cell is increased or a certain percentage of cells displayed punctate GFP-Atg8/LC3 that exceeds a particular threshold (and this threshold should be clearly defined in the Methods section), or that there is a particular increase or decrease in the rate of cargo sequestration or the degradation of long-lived proteins, when these are the actual measurements being quantified.

In a previous version of these guidelines,2 the methods were separated into 2 main sections—steady state and flux. In some instances, a lack of clear distinction between the actual methodologies and their potential uses made such a separation somewhat artificial. For example, fluorescence microscopy was initially listed as a steady-state method, although this approach can clearly be used to monitor flux as described in this article, especially when considering the increasing availability of new technologies such as microfluidic chambers. Furthermore, the use of multiple time points and/or lysosomal fusion/degradation inhibitors can turn even a typically static method such as TEM into one that monitors flux. Therefore, although we maintain the importance of monitoring autophagic flux and not just induction, this revised set of guidelines does not separate the methods based on this criterion. Readers should be aware that this article is not meant to present protocols, but rather guidelines, including information that is typically not presented in protocol papers. For detailed information on experimental procedures we refer readers to various protocols that have been published elsewhere.28-43,44 Finally, throughout the guidelines we provide specific cautionary notes, and these are important to consider when planning experiments and interpreting data; however, these cautions are not meant to be a deterrent to undertaking any of these experiments or a hindrance to data interpretation.

Collectively, we propose the following guidelines for measuring various aspects of selective and nonselective autophagy in eukaryotes.

A. Methods for monitoring autophagy

1. Transmission electron microscopy

Autophagy was first detected by TEM in the 1950s (reviewed in ref. 6). It was originally observed as focal degradation of cytoplasmic areas performed by lysosomes, which remains the hallmark of this process. Later analyses revealed that it starts with the sequestration of portions of the cytoplasm by a special double-membrane structure (now termed the phagophore), which matures into the autophagosome, still bordered by a double membrane. Subsequent fusion events expose the cargo to the lysosome (or the vacuole in fungi or plants) for enzymatic breakdown.

The importance of TEM in autophagy research lies in several qualities. It is the only tool that reveals the morphology of autophagic structures at a resolution in the nm range; shows these structures in their natural environment and position among all other cellular components; allows their exact identification; and, in addition, it can support quantitative studies if the rules of proper sampling are followed.11

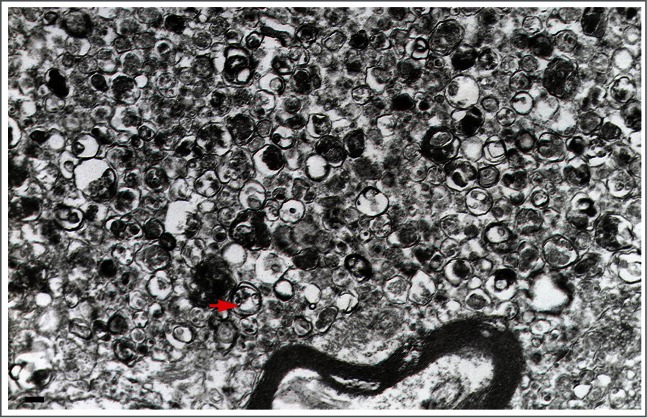

Autophagy can be both selective and nonselective, and TEM can be used to monitor both. In the case of selective autophagy, the cargo is the specific substrate being targeted for sequestration—bulk cytoplasm is essentially excluded. In contrast, during nonselective autophagy, the various cytoplasmic constituents are sequestered randomly, resulting in autophagosomes in the size range of normal mitochondria. Sequestration of larger structures (such as big lipid droplets, extremely elongated or branching mitochondria or the entire Golgi complex) is rare, indicating an apparent upper size limit for individual autophagosomes. However, it has been observed that under special circumstances the potential exists for the formation of huge autophagosomes, which can even engulf a complete nucleus.25 Cellular components that form large confluent areas excluding bulk cytoplasm, such as organized, functional myofibrillar structures, do not seem to be sequestered by macroautophagy. The situation is less clear with regard to glycogen.45-47

After sequestration, the content of the autophagosome and its bordering double membrane remain morphologically unchanged, and clearly recognizable for a considerable time, which can be measured for at least many minutes. During this period, the membranes of the sequestered organelles (for example, the ER or mitochondria) remain intact, and the density of ribosomes is conserved at normal levels. Degradation of the sequestered material and the corresponding deterioration of ultrastructure commences and runs to completion within the amphisome and the autolysosome after fusion with a late endosome and lysosome (the vacuole in fungi and plants), respectively (Fig. 1).48 The sequential morphological changes during the autophagic process can be followed by TEM. The maturation from the phagophore through the autolysosome is a dynamic and continuous process,49 and, thus, the classification of compartments into discrete morphological subsets can be problematic; therefore, some basic guidelines are offered below.

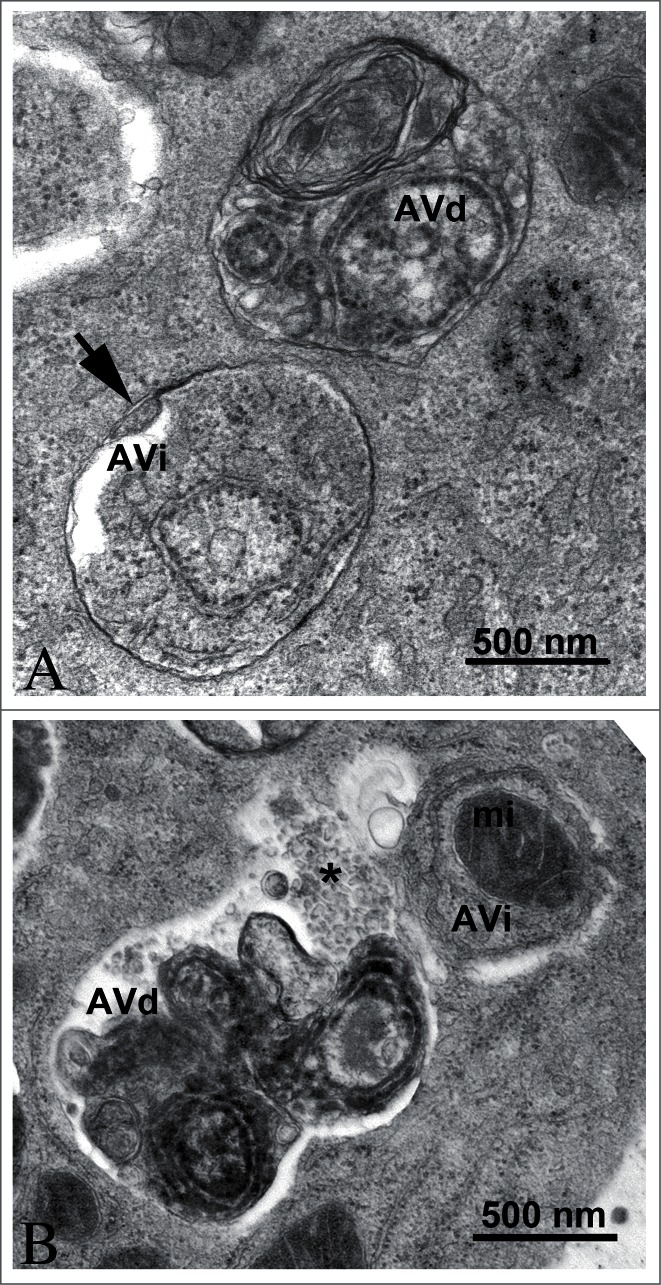

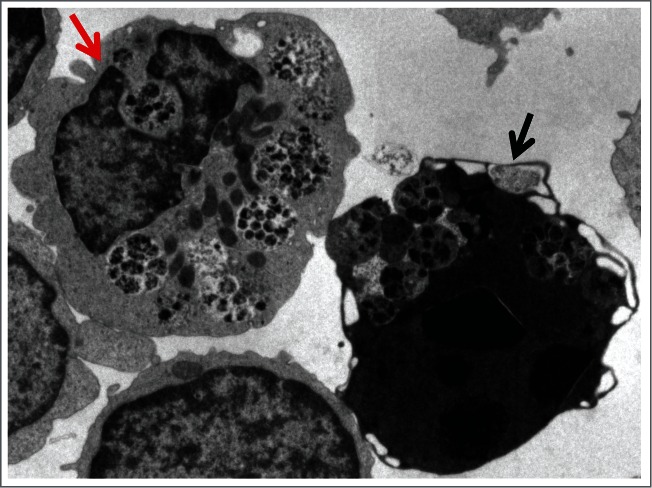

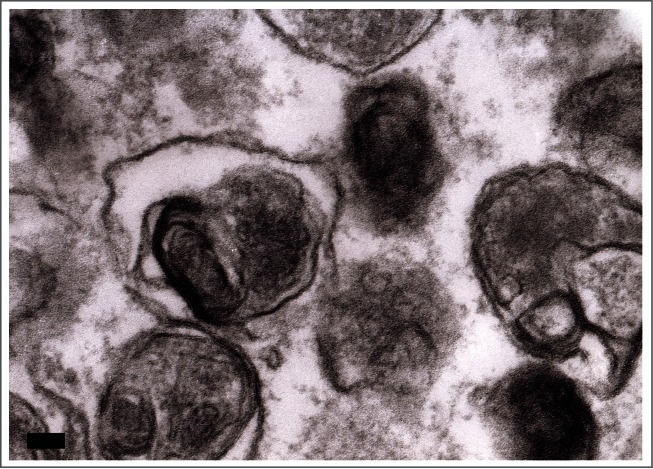

In the preceding sections the “autophagosome,” the “amphisome” and the “autolysosome” were terms used to describe or indicate 3 basic stages and compartments of autophagy. It is important to make it clear that for instances (which may be many) when we cannot or do not want to differentiate among the autophagosomal, amphisomal and autolysosomal stage we use the general term “autophagic vacuole”. In the yeast autophagy field the term “autophagic vesicle” is used to avoid confusion with the primary vacuole, and by now the 2 terms are used in parallel and can be considered synonyms. It is strongly recommended, however, to use only the term “autophagic vacuole” when referring to macroautophagy in higher eukaryotic cells. Autophagosomes, also referred to as initial autophagic vacuoles (AVi), typically have a double membrane. This structure is usually distinctly visible by EM as 2 parallel membrane layers (bilayers) separated by a relatively narrower or wider electron-translucent cleft, even when applying the simplest routine EM fixation procedure (Fig. 3A).50,51 This electron-translucent cleft, however, is less visible or not visible in freeze-fixed samples, suggesting it is an artifact of sample preparation (see ref. 25, 68 and Fig. S3 in ref. 52). In the case of nonselective autophagy, autophagosomes contain cytosol and/or organelles appearing morphologically intact as also described above.48,53 Amphisomes54 can sometimes be identified by the presence of small intralumenal vesicles.55 These intralumenal vesicles are delivered into the lumen by fusion of the autophagosome/autophagic vacuole (AV) limiting membrane with multivesicular endosomes, and care should therefore be taken in the identification of the organelles, especially in cells that produce large numbers of multivesicular body (MVB)-derived exosomes (such as tumor or stem cells).56 Late/degradative autophagic vacuoles/autolysosomes (AVd or AL) typically have only one limiting membrane; frequently they contain electron dense cytoplasmic material and/or organelles at various stages of degradation (Fig. 3A and B);48,53 although late in the digestion process, they may contain only a few membrane fragments and be difficult to distinguish from lysosomes, endosomes, or tubular smooth ER cut in cross-section. Unequivocal identification of these structures and of lysosomes devoid of visible content requires immuno-EM detection of a cathepsin or other lysosomal hydrolase (e.g., ACP2 [acid phosphatase 2, lysosomal]57,58) that is detected on the limiting membrane of the lysosome.59 Smaller, often electron dense, lysosomes may predominate in some cells and exhibit hydrolase immunoreactivity within the lumen and on the limiting membrane.60

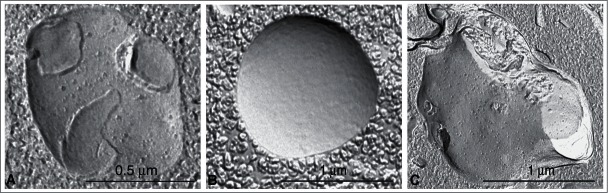

Figure 3.

TEM images of autophagic vacuoles in isolated mouse hepatocytes. (A) One autophagosome or early initial autophagic vacuole (AVi) and one degradative autophagic vacuole (AVd) are shown. The AVi can be identified by its contents (morphologically intact cytoplasm, including ribosomes, and rough ER), and the limiting membrane that is partially visible as 2 bilayers separated by a narrow electron-lucent cleft, i.e., as a double membrane (arrow). The AVd can be identified by its contents, partially degraded, electron-dense rough ER. The vesicle next to the AVd is an endosomal/lysosomal structure containing 5-nm gold particles that were added to the culture medium to trace the endocytic pathway. (B) One AVi, containing rough ER and a mitochondrion, and one AVd, containing partially degraded rough ER, are shown. Note that the limiting membrane of the AVi is not clearly visible, possibly because it is tangentially sectioned. However, the electron-lucent cleft between the 2 limiting membranes is visible and helps in the identification of the AVi. The AVd contains a region filled by small internal vesicles (asterisk), indicating that the AVd has fused with a multivesicular endosome. mi, mitochondrion. Image provided by E.-L. Eskelinen.

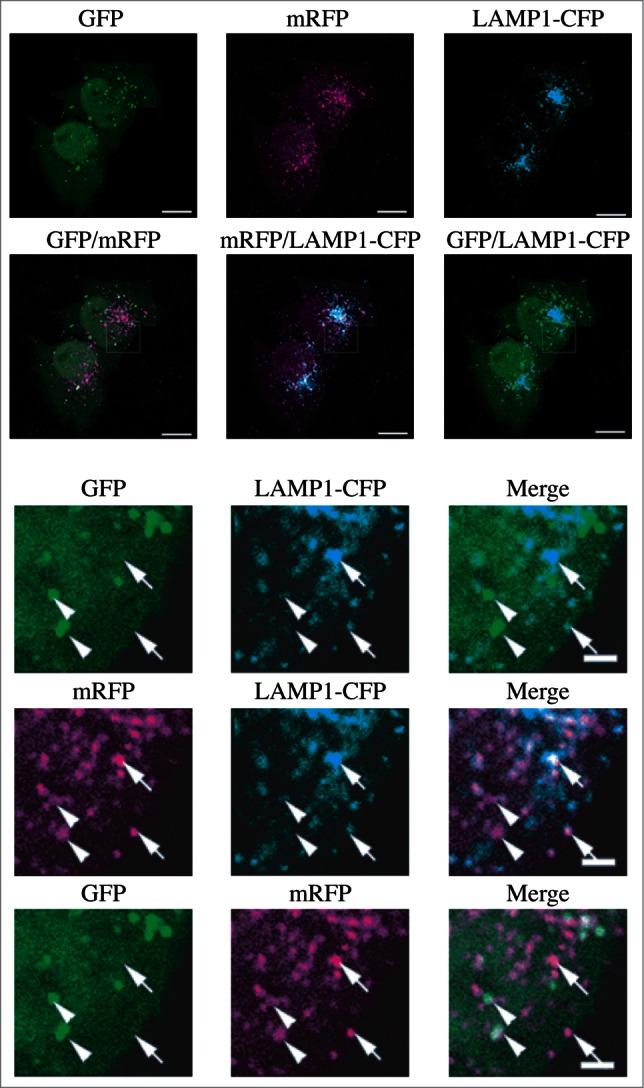

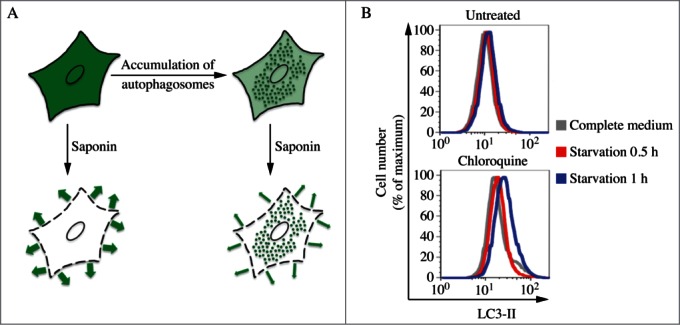

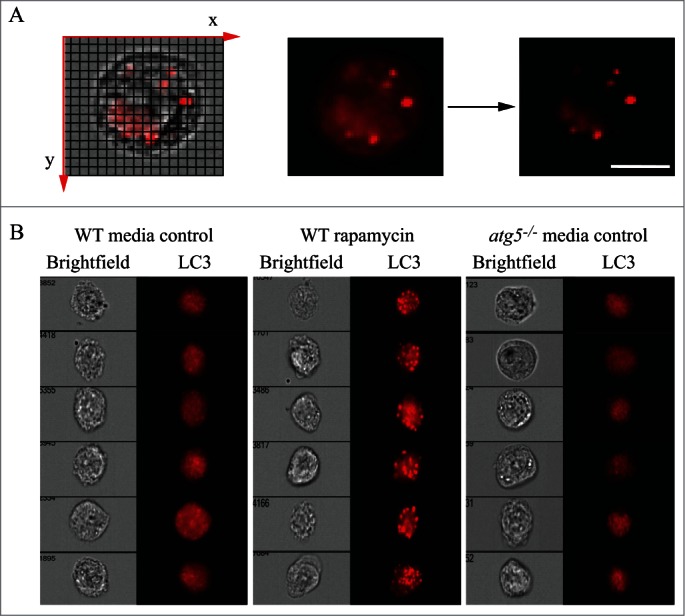

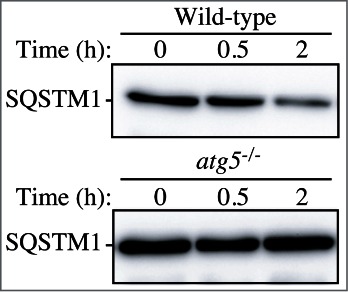

In addition, structural proteins of the lysosome/late endosome, such as LAMP1 and LAMP2 or SCARB2/LIMP-2, can be used for confirmation. No single protein marker, however, has been effective in discriminating autolysosomes from the compartments mentioned above, in part due to the dynamic fusion and “kiss-and-run” events that promote interchange of components that can occur between these organelle subtypes. Rigorous further discrimination of these compartments from each other and other vesicles ultimately requires demonstrating the colocalization of a second marker indicating the presence of an autophagic substrate (e.g., LC3-CTSD [cathepsin D] colocalization) or the acidification of the compartment (e.g., mRFP/mCherry-GFP-LC3 probes [see Tandem mRFP/mCherry-GFP fluorescence microscopy], or Bodipy-pepstatin A detection of CTSD in an activated form within an acidic compartment), and, when appropriate, by excluding markers of other vesicular components.57,61,62

The sequential deterioration of cytoplasmic structures being digested can be used for identifying autolysosomes by TEM. Even when the partially digested and destroyed structure cannot be recognized in itself, it can be traced back to earlier forms by identifying preceding stages of sequential morphological deterioration. Degradation usually leads first to increased density of still recognizable organelles, then to vacuoles with heterogenous density, which become more homogenous and amorphous, mostly electron dense, but sometimes light (i.e., electron translucent). It should be noted that, in pathological states, it is not uncommon that active autophagy of autolysosomes and damaged lysosomes (“lysosophagy”) may yield populations of double-membrane limited autophagosomes containing partially digested amorphous substrates in the lumen. These structures, which are enriched in hydrolases, are seen in swollen dystrophic neurites in some neurodegenerative diseases,60 and in cerebellar slices cultured in vitro and infected with prions.63

It must be emphasized that in addition to the autophagic input, other processes (e.g., endosomal, phagosomal, chaperone-mediated) also carry cargo to the lysosomes,64,65 in some cases through the intermediate step of direct endosome fusion with an autophagosome to form an amphisome. This process is exceptionally common in the axons of neurons.66 Therefore, strictly speaking, we can only have a lytic compartment containing cargos arriving from several possible sources; however, we still may use the term “autolysosome” if the content appears to be overwhelmingly autophagic. Note that the engulfment of apoptotic cells via phagocytosis also produces lysosomes that contain cytoplasmic structures, but in this case it originates from the dying cell; hence the possibility of an extracellular origin for such content must be considered when monitoring autophagy in settings where apoptotic cell death may be reasonably expected or anticipated.

For many physiological and pathological situations, examination of both early and late autophagic vacuoles yields valuable data regarding the overall autophagy status in the cells.15 Along these lines, it is possible to use immunocytochemistry to follow particular cytosolic proteins such as SOD1/CuZn superoxide dismutase and CA/carbonic anhydrase to determine the stage of autophagy; the former is much more resistant to lysosomal degradation.67

In some autophagy-inducing conditions it is possible to observe multi-lamellar membrane structures in addition to the conventional double-membrane autophagosomes, although the nature of these structures is not fully understood. These multi-lamellar structures may indeed be multiple double layers of phagophores68 and positive for LC3,69 they could be autolysosomes,70 or they may form artifactually during fixation.68

Special features of the autophagic process may be clarified by immuno-TEM with gold-labeling,71,72 using antibodies, for example, to cargo proteins of cytoplasmic origin and to LC3 to verify the autophagic nature of the compartment. LC3 immunogold labeling also makes it possible to detect novel degradative organelles within autophagy compartments. This is the case with the autophagoproteasome73 where costaining for LC3 and ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) antigens occurs. The autophagoproteasome consists of single-, double-, or multiple-membrane LC3-positive autophagosomes costaining for specific components of the UPS. It may be that a rich multi-enzymatic (both autophagic and UPS) activity takes place within these organelles instead of being segregated within different cell domains.

Although labeling of LC3 can be difficult, an increasing number of commercial antibodies are becoming available, among them good ones to visualize the GFP moiety of GFP-LC3 reporter constructs.74 It is important to keep in mind that LC3 can be associated with nonautophagic structures (see Xenophagy, and Noncanonical use of autophagy-related proteins). LC3 is involved in specialized forms of endocytosis like LC3-associated phagocytosis. In addition, LC3 can decorate vesicles dedicated to exocytosis in nonconventional secretion systems (reviewed in ref. 75,76). Antibodies against an abundant cytosolic protein will result in high labeling all over the cytoplasm; however, organelle markers work well. Because there are very few characterized proteins that remain associated with the completed autophagosome, the choices for confirmation of its autophagic nature are limited. Furthermore, autophagosome-associated proteins may be cell type-specific. At any rate, the success of this methodology depends on the quality of the antibodies and also on the TEM preparation and fixation procedures utilized. With immuno-TEM, authors should provide controls showing that labeling is specific. This may require quantitative comparison of labeling over different cellular compartments not expected to contain antigen and those containing the antigen of interest.

In clinical situations it is difficult to demonstrate autophagy clearly in tissues of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded biopsy samples retrospectively, because (1) tissues fixed in formalin have low or no LC3 detectable by routine immunostaining, because phospholipids melt together with paraffin during the sample preparation, and (2) immunogold electron microscopy of many tissues not optimally fixed for this purpose (e.g., using rapid fixation) produces low-quality images. Combining antigen retrieval with the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (ABC) method may be quite useful for these situations. For example, immunohistochemistry can be performed using an antigen retrieval method, then tissues are stained by the ABC technique using a labeled anti-human LC3 antibody. After imaging by light microscopy, the same prepared slides can be remade into sections for TEM examination, which can reveal peroxidase reaction deposits in vacuoles within the region that is LC3-immunopositive by light microscopy.77 In addition, statistical information should be provided due to the necessity of showing only a selective number of sections in publications.

We note here again that for quantitative data it is necessary to use proper volumetric analysis rather than just counting numbers of sectioned objects. On the one hand, it must be kept in mind that even volumetric morphometry/stereology only shows either steady state levels, or a snapshot in a changing dynamic process. Such data by themselves are not informative regarding autophagic flux, unless carried out over multiple time points. Alternatively, investigation in the presence and absence of flux inhibitors can reveal the dynamic changes in various stages of the autophagic process.12,21,78,79,42 On the other hand, if the turnover of autolysosomes is very rapid, a low number/volume will not necessarily be an accurate reflection of low autophagic activity. However, quantitative analyses indicate that autophagosome volume in many cases does correlate with the rates of protein degradation.80-82 One potential compromise is to perform whole cell quantification of autophagosomes using fluorescence methods, with qualitative verification by TEM,83 to show that the changes in fluorescent puncta reflect corresponding changes in autophagic structures.

One additional caveat with TEM, and to some extent with confocal fluorescence microscopy, is that the analysis of a single plane within a cell can be misleading and may make the identification of autophagic structures difficult. Confocal microscopy and fluorescence microscopy with deconvolution software (or with much more work, 3-dimensional TEM) can be used to generate multiple/serial sections of the same cell to reduce this concern; however, in many cases where there is sufficient structural resolution, analysis of a single plane in a relatively large cell population can suffice given practical limitations. Newer EM technologies, including focused ion beam dual-beam EM, should make it much easier to apply three-dimensional analyses. An additional methodology to assess autophagosome accumulation is correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM), which is helpful in confirming that fluorescent structures are autophagosomes.84-86 Along these lines, it is important to note that even though GFP fluorescence will be quenched in the acidic environment of the autolysosome, some of the GFP puncta detected by light microscopy may correspond to early autolysosomes prior to GFP quenching. The mini Singlet Oxygen Generator (miniSOG) fluorescent flavoprotein, which is less than half the size of GFP, provides an additional means to genetically tag proteins for CLEM analysis under conditions that are particularly suited to subsequent TEM analysis.87 Combinatorial assays using tandem monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP)-GFP-LC3 (see Tandem mRFP/mCherry-GFP fluorescence microscopy) along with static TEM images should help in the analysis of flux and the visualization of cargo structures.88

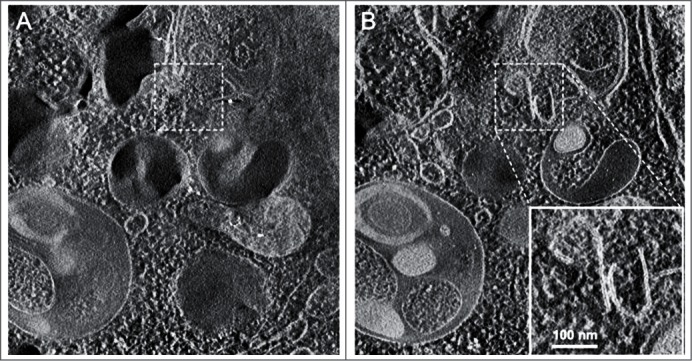

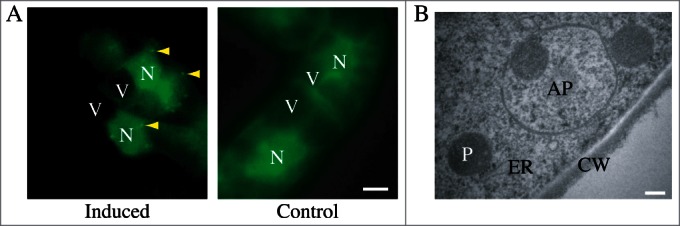

Another technique that has proven quite useful for analyzing the complex membrane structures that participate in autophagy is 3-dimensional electron tomography,89,90 and cryoelectron microscopy (Fig. 4). More sophisticated, cryo-soft X-ray tomography (cryo-SXT) is an emerging imaging technique used to visualize autophagosomes.91 Cryo-SXT extracts ultrastructural information from whole, unstained mammalian cells as close to the “near-native” fully-hydrated (living) state as possible. Correlative studies combining cryo-fluorescence and cryo-SXT workflow (cryo-CLXM) have been applied to capture early autophagosomes.

Figure 4.

Cryoelectron microscopy can be used as a three-dimensional approach to monitor the autophagic process. Two computed sections of an electron tomogram of the autophagic vacuole-rich cytoplasm in a hemophagocyte of a semi-thin section after high-pressure freezing preparation. The dashed area is membrane-free (A) but tomography reveals newly formed or degrading membranes with a parallel stretch (B). Image published previously2185 and provided by M. Schneider and P. Walter.

Finally, although only as an indirect measurement, the comparison of the ratio of autophagosomes to autolysosomes by TEM can support alterations in autophagy identified by other procedures.92 In this case it is important to always compare samples to the control of the same cell type and in the same growth phase, and to acquire data at different time points, as the autophagosome/autolysosome ratio varies in time in a cell context-dependent fashion, depending on their clearance activity. It may also be necessary to distinguish autolysosomes from telolysosomes/late secondary lysosomes (the former are actively engaged in degradation, whereas the latter have reached an end point in the breakdown of lumenal contents) because the lysosome number generally increases when autophagy is induced. An additional category of lysosomal compartments, especially common in disease states and aged postmitotic cells such as neurons, is the residual body. This category includes ceroid and lipofuscin, lobulated vesicular compartments of varying size composed of highly indigestible complexes of protein and lipid and abundant, mostly inactive, acid hydrolases. Reflecting end-stage unsuccessful incomplete autolysosomal digestion, lipofuscin is fairly easily distinguished from AVs and lysosomes by TEM but can be easily confused with autolysosomes in immunocytochemistry studies at the light microscopy level.57

TEM observations of platinum-carbon replicas obtained by the freeze fracture technique can also supply useful ultrastructural information on the autophagic process. In quickly frozen and fractured cells the fracture runs preferentially along the hydrophobic plane of the membranes, allowing characterization of the limiting membranes of the different types of autophagic vacuoles and visualization of their limited protein intramembrane particles (IMPs, or integral membrane proteins). Several studies have been carried out using this technique on yeast,93 as well as on mammalian cells or tissues; first on mouse exocrine pancreas,94 then on mouse and rat liver,95,96 mouse seminal vesicle epithelium,25,68 rat tumor and heart,97 or cancer cell lines (e.g., breast cancer MDA-MB-231)98 to investigate the various phases of autophagosome maturation, and to reveal useful details about the origin and evolution of their limiting membranes.6,99-102

The phagophore and the limiting membranes of autophagosomes contain few, or no detectable, IMPs (Fig. 5A, B), when compared to other cellular membranes and to the membranes of lysosomes. In subsequent stages of the autophagic process the fusion of the autophagosome with an endosome and a lysosome results in increased density of IMPs in the membrane of the formed autophagic compartments (amphisomes, autolysosomes; Fig. 5C).6,25,93-96,103,104 Autolysosomes are delimited by a single membrane because, in addition to the engulfed material, the inner membrane is also degraded by the lytic enzymes. Similarly, the limiting membrane of autophagic bodies in yeast (and presumably plants) is also quickly broken down under normal conditions. Autophagic bodies can be stabilized, however, by the addition of phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF) or genetically by the deletion of the yeast PEP4 gene (see The Cvt pathway, mitophagy, pexophagy, piecemeal microautophagy of the nucleus and late nucleophagy in yeast and filamentous fungi.). Thus, another method to consider for monitoring autophagy in yeast (and potentially in plants) is to count autophagic bodies by TEM using at least 2 time points.105 The advantage of this approach is that it can provide accurate information on flux even when the autophagosomes are abnormally small.106,107 Thus, although a high frequency of “abnormal” structures presents a challenge, TEM is still very helpful in analyzing autophagy.

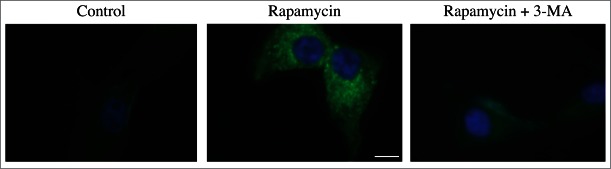

Figure 5.

Different autophagic vacuoles observed after freeze fracturing in cultured osteosarcoma cells after treatment with the autophagy inducer voacamine.101 (A) Early autophagosome delimited by a double membrane. (B) Inner monolayer of an autophagosome membrane deprived of protein particles. (C) Autolysosome delimited by a single membrane rich in protein particles. In the cross-fractured portion (on the right) the profile of the single membrane and the inner digested material are easily visible. Images provided by S. Meschini, M. Condello and A. Giuseppe.

Cautionary notes: Despite the introduction of many new methods TEM maintains its special role in autophagy research. There are, however, difficulties in utilizing TEM. It is relatively time consuming, and needs technical expertise to ensure proper handling of samples in all stages of preparation from fixation to sectioning and staining (contrasting). After all these criteria are met, we face the most important problem of proper identification of autophagic structures. This is crucial for both qualitative and quantitative characterization, and needs considerable experience, even in the case of one cell type. The difficulty lies in the fact that many subcellular components may be mistaken for autophagic structures. For example, some authors (or reviewers of manuscripts) assume that almost all cytoplasmic structures that, in the section plane, are surrounded by 2 (more or less) parallel membranes are autophagosomes. Structures appearing to be limited by a double membrane, however, may include swollen mitochondria, plastids in plant cells, cellular interdigitations, endocytosed apoptotic bodies, circular structures of lamellar smooth endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and even areas surrounded by rough ER. Endosomes, phagosomes and secretory vacuoles may have heterogenous content that makes it possible to confuse them with autolysosomes. Additional identification problems may arise from damage caused by improper sample taking or fixation artifacts.50,51,108,109

Whereas fixation of in vitro samples is relatively straightforward, fixation of excised tissues requires care to avoid sampling a nonrepresentative, uninformative, or damaged part of the tissue. For instance, if 95% of a tumor is necrotic, TEM analysis of the necrotic core may not be informative, and if the sampling is from the viable rim, this needs to be specified when reported. Clearly this introduces the potential for subjectivity because reviewers of a paper cannot request multiple images with a careful statistical analysis with these types of samples. In addition, ex vivo samples are not typically randomized during processing, further complicating the possibility of valid statistical analyses. Ex vivo tissue should be fixed immediately and systematically across samples to avoid changes in autophagy that may occur simply due to the elapsed time ex vivo. It is recommended that for tissue samples, perfusion fixation should be used when possible. For yeast, rapid freezing techniques such as high pressure freezing followed by freeze substitution (i.e., dehydration at low temperature) may be particularly useful.

Quantification of autophagy by TEM morphometry has been rather controversial, and unreliable procedures still continue to be used. For the principles of reliable quantification and to avoid misleading results, excellent reviews are available.11,110-112 In line with the basic principles of morphometry we find it necessary to emphasize here some common problems with regard to quantification. Counting autophagic vacuole profiles in sections of cells (i.e., number of autophagic profiles per cell profile) may give unreliable results, partly because both cell areas and profile areas are variable and also because the frequency of section profiles depends on the size of the vacuoles. However, estimation of the number of autophagic profiles per cell area is more reliable and correlates well with the volume fraction mentioned below.53 There are morphometric procedures to measure or estimate the size range and the number of spherical objects by profiles in sections;111 however, such methods have been used in autophagy research only a few times.32,107,113,114

Proper morphometry described in the cited reviews will give us data expressed in µm3 autophagic vacuole/µm3 cytoplasm for relative volume (also called volume fraction or volume density), or µm2 autophagic vacuole surface/µm3 cytoplasm for relative surface (surface density). Examples of actual morphometric measurements for the characterization of autophagic processes can be found in several articles.21,108,111,115,116 It is appropriate to note here that a change in the volume fraction of the autophagic compartment may come from 2 sources; from the real growth of its size in a given cytoplasmic volume, or from the decrease of the cytoplasmic volume itself. To avoid this so-called “reference trap,” the reference space volume can be determined by different methods.112,117 If different magnifications are used for measuring the autophagic vacuoles and the cytoplasm (which may be practical when autophagy is less intense) correction factors should always be used.

In some cases, it may be prudent to employ tomographic reconstructions of the TEM images to confirm that the autophagic compartments are spherical and are not being confused with interdigitations observed between neighboring cells, endomembrane cisternae or damaged mitochondria with similar appearance in thin-sections (e.g., see ref. 118), but this is obviously a time-consuming approach requiring sophisticated equipment. In addition, interpretation of tomographic images can be problematic. For example, starvation-induced autophagosomes should contain cytoplasm (i.e., cytosol and possibly organelles), but autophagosome-related structures involved in specific types of autophagy should show the selective cytoplasmic target, but may be relatively devoid of bulk cytoplasm. Such processes include selective peroxisome or mitochondria degradation (pexophagy or mitophagy, respectively),119,120 targeted degradation of pathogenic microbes (xenophagy),121-126 a combination of xenophagy and stress-induced mitophagy,127 as well as the yeast biosynthetic cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting (Cvt) pathway.128 Furthermore, some pathogenic microbes express membrane-disrupting factors during infection (e.g., phospholipases) that disrupt the normal double-membrane architecture of autophagosomes.129 It is not even clear if the sequestering compartments used for specific organelle degradation or xenophagy should be termed autophagosomes or if alternate terms such as pexophagosome,130 mitophagosome and xenophagosome should be used, even though the membrane and mechanisms involved in their formation may be identical to those for starvation-induced autophagosomes; for example, the double-membrane vesicle of the Cvt pathway is referred to as a Cvt vesicle.131

The confusion of heterophagic structures with autophagic ones is a major source of misinterpretation. A prominent example of this is related to apoptosis. Apoptotic bodies from neighboring cells are readily phagocytosed by surviving cells of the same tissue.132,133 Immediately after phagocytic uptake of apoptotic bodies, phagosomes may have double limiting membranes. The inner one is the plasma membrane of the apoptotic body and the outer one is that of the phagocytizing cell. The early heterophagic vacuole formed in this way may appear similar to an autophagosome or, in a later stage, an early autolysosome in that it contains recognizable or identifiable cytoplasmic material. A major difference, however, is that the surrounding membranes are the thicker plasma membrane type, rather than the thinner sequestration membrane type (9–10 nm, versus 7–8 nm, respectively).109 A good feature to distinguish between autophagosomes and double plasma membrane-bound structures is the lack of the distended empty space (characteristic for the sequestration membranes of autophagosomes) between the 2 membranes of the phagocytic vacuoles. In addition, engulfed apoptotic bodies usually have a larger average size than autophagosomes.134,135 The problem of heterophagic elements interfering with the identification of autophagic ones is most prominent in cell types with particularly intense heterophagic activity (such as macrophages, and amoeboid or ciliate protists). Special attention has to be paid to this problem in cell cultures or in vivo treatments (e.g., with toxic or chemotherapeutic agents) causing extensive apoptosis.

The most common organelles confused with autophagic vacuoles are mitochondria, ER, endosomes, and also (depending on their structure) plastids in plants. Due to the cisternal structure of the ER, double-membrane-like structures surrounding mitochondria or other organelles are often observed after sectioning,136 but these can also correspond to cisternae of the ER coming into and out of the section plane.50 If there are ribosomes associated with these membranes they can help in distinguishing them from the ribosome-free double-membrane of the phagophore and autophagosome. Observation of a mixture of early and late autophagic vacuoles that is modulated by the time point of collection and/or brief pulses of bafilomycin A1 (a vacuolar-type H+-ATPase [V-ATPase] inhibitor) to trap the cargo in a recognizable early state42 increases the confidence that an autophagic process is being observed. In these cases, however, the possibility that feedback activation of sequestration gets involved in the autophagic process has to be carefully considered. To minimize the impact of errors, exact categorization of autophagic elements should be applied. Efforts should be made to clarify the nature of questionable structures by extensive preliminary comparison in many test areas. Elements that still remain questionable should be categorized into special groups and measured separately. Should their later identification become possible, they can be added to the proper category or, if not, kept separate.

For nonspecialists it can be particularly difficult to distinguish among amphisomes, autolysosomes and lysosomes, which are all single-membrane compartments containing more or less degraded material. Therefore, we suggest in general to measure autophagosomes as a separate category for a start, and to compile another category of degradative compartments (including amphisomes, autolysosomes and lysosomes). All of these compartments increase in quantity upon true autophagy induction; however, in pathological states, it may be informative to discriminate among these different forms of degradative compartments, which may be differentially affected by disease factors.

In yeast, it is convenient to identify autophagic bodies that reside within the vacuole lumen, and to quantify them as an alternative to the direct examination of autophagosomes. However, it is important to keep in mind that it may not be possible to distinguish between autophagic bodies that are derived from the fusion of autophagosomes with the vacuole, and the single-membrane vesicles that are generated during microautophagy-like processes such as micropexophagy and micromitophagy.

Conclusion: EM is an extremely informative and powerful method for monitoring autophagy and remains the only technique that shows autophagy in its complex cellular environment with subcellular resolution. The cornerstone of successfully using TEM is the proper identification of autophagic structures, which is also the prerequisite to get reliable quantitative results by EM morphometry. EM is best used in combination with other methods to ensure the complex and holistic approach that is becoming increasingly necessary for further progress in autophagy research.

2. Atg8/LC3 detection and quantification

Atg8/LC3 is the most widely monitored autophagy-related protein. In this section we describe multiple assays that utilize this protein, separating the descriptions into several subsections for ease of discussion.

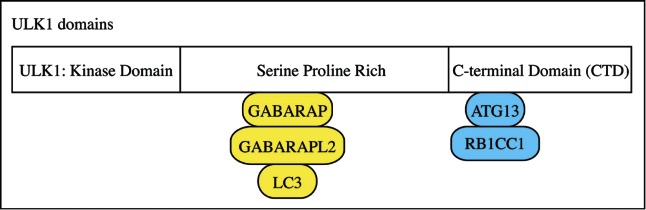

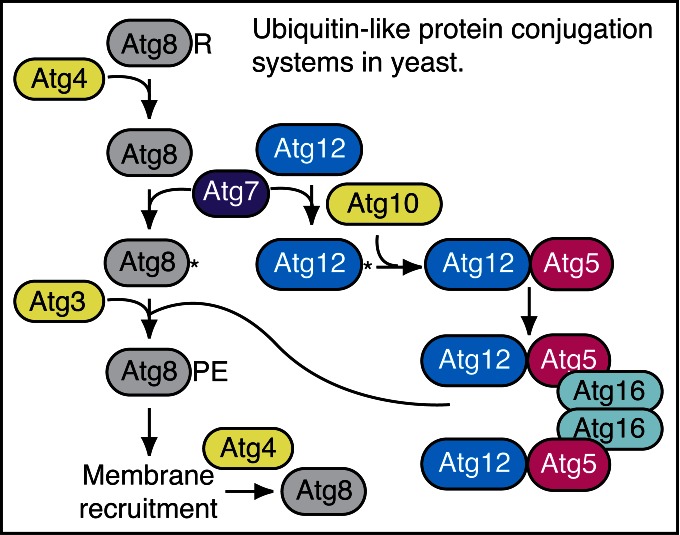

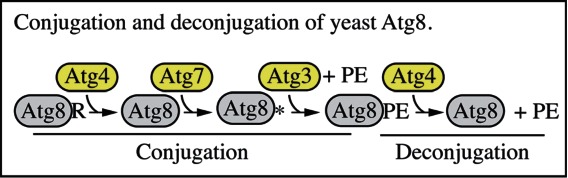

a. Western blotting and ubiquitin-like protein conjugation systems

The Atg8/LC3 protein is a ubiquitin-like protein that can be conjugated to PE (and possibly to phosphatidylserine137). In yeast and several other organisms, the conjugated form is referred to as Atg8–PE. The mammalian homologs of Atg8 constitute a family of proteins subdivided in 2 major subfamilies: MAP1LC3/LC3 and GABARAP. The former consists of LC3A, B, B2 and C, whereas the latter family includes GABARAP, GABARAPL1 and GABARAPL2/GATE-16.138 After cleavage of the precursor protein mostly by the cysteine protease ATG4B,139,140 the nonlipidated and lipidated forms are usually referred to respectively as LC3-I and LC3-II, or GABARAP and GABARAP–PE, etc. The PE-conjugated form of Atg8/LC3, although larger in mass, shows faster electrophoretic mobility in SDS-PAGE gels, probably as a consequence of increased hydrophobicity. The positions of both Atg8/LC3-I (approximately 16–18 kDa) and Atg8–PE/LC3-II (approximately 14–16 kDa) should be indicated on western blots whenever both are detectable. The differences among the LC3 proteins with regard to function and tissue-specific expression are not known. Therefore, it is important to indicate the isoform being analyzed just as it is for the GABARAP subfamily.

The mammalian Atg8 homologs share from 29% to 94% sequence identity with the yeast protein and have all, apart from GABARAPL3, been demonstrated to be involved in autophagosome biogenesis.141 The LC3 proteins are involved in phagophore formation, with participation of GABARAP subfamily members in later stages of autophagosome formation, in particular phagophore elongation and closure.142 Some evidence, however, suggests that at least in certain cell types the LC3 subfamily may be dispensable for bulk autophagic sequestration of cytosolic proteins, whereas the GABARAP subfamily is absolutely required.143 Due to unique features in their molecular surface charge distribution,144 emerging evidence indicates that LC3 and GABARAP proteins may be involved in recognizing distinct sets of cargoes for selective autophagy.145-147 Nevertheless, in most published studies, LC3 has been the primary Atg8 homolog examined in mammalian cells and the one that is typically characterized as an autophagosome marker per se. Note that although this protein is referred to as “Atg8” in many other systems, we primarily refer to it here as LC3 to distinguish it from the yeast protein and from the GABARAP subfamily. LC3, like the other Atg8 homologs, is initially synthesized in an unprocessed form, proLC3, which is converted into a proteolytically processed form lacking amino acids from the C terminus, LC3-I, and is finally modified into the PE-conjugated form, LC3-II (Fig. 6). Atg8–PE/LC3-II is the only protein marker that is reliably associated with completed autophagosomes, but is also localized to phagophores. In yeast, Atg8 amounts increase at least 10-fold when autophagy is induced.148 In mammalian cells, however, the total levels of LC3 do not necessarily change in a predictable manner, as there may be increases in the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II, or a decrease in LC3-II relative to LC3-I if degradation of LC3-II via lysosomal turnover is particularly rapid (this can also be a concern in yeast with regard to vacuolar turnover of Atg8–PE). Both of these events can be seen sequentially in several cell types as a response to total nutrient and serum starvation. In cells of neuronal origin a high ratio of LC3-I to LC3-II is a common finding.149 For instance, SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell lines display only a slight increase of LC3-II after nutrient deprivation, whereas LC3-I is clearly reduced. This is likely related to a high basal autophagic flux, as suggested by the higher increase in LC3-II when cells are treated with NH4Cl,150,151 although cell-specific differences in transcriptional regulation of LC3 may also play a role. In fact stimuli or stress that inhibit transcription or translation of LC3 might actually be misinterpreted as inhibition of autophagy. Importantly, in brain tissue, LC3-I is much more abundant than LC3-II and the latter form is most easily discernable in enriched fractions of autophagosomes, autolysosomes and ER, and may be more difficult to detect in crude homogenate or cytosol.152 Indeed, when brain crude homogenate is run in parallel to a crude liver fraction, both LC3-I and LC3-II are observed in the liver, but only LC3-I may be discernible in brain homogenate (L. Toker and G. Agam, personal communication), depending on the LC3 antibody used.153 In studies of the brain, immunoblot analysis of the membrane and cytosol fraction from a cell lysate, upon appropriate loading of samples to achieve quantifiable and comparative signals, can be useful to measure LC3 isoforms.

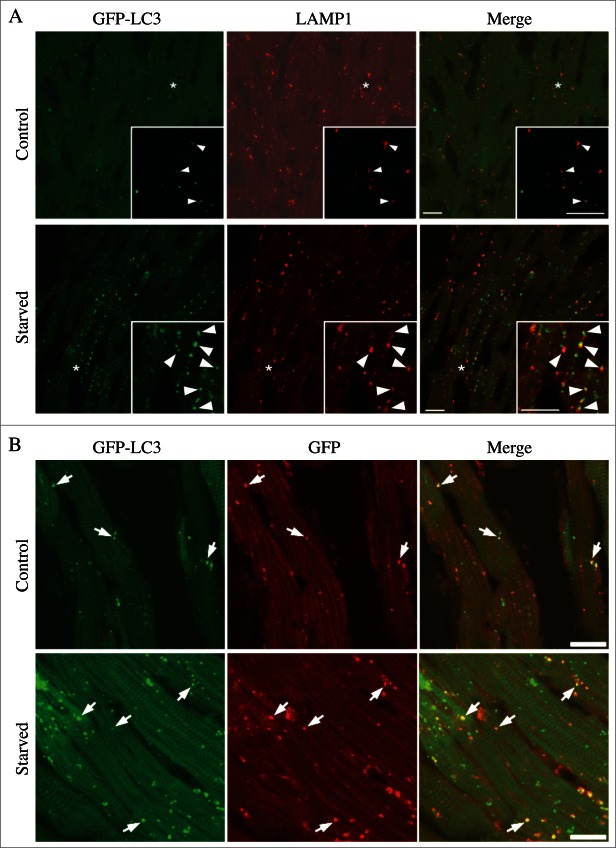

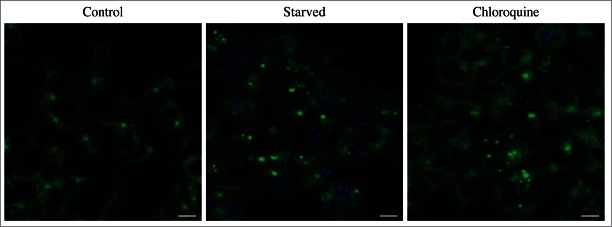

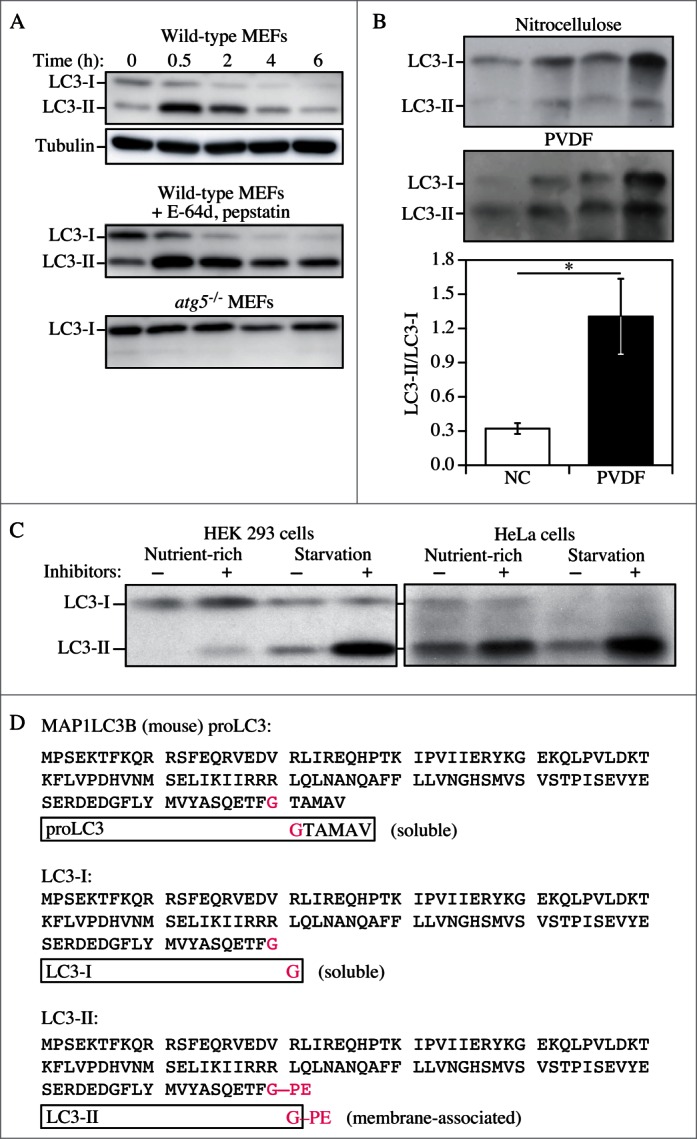

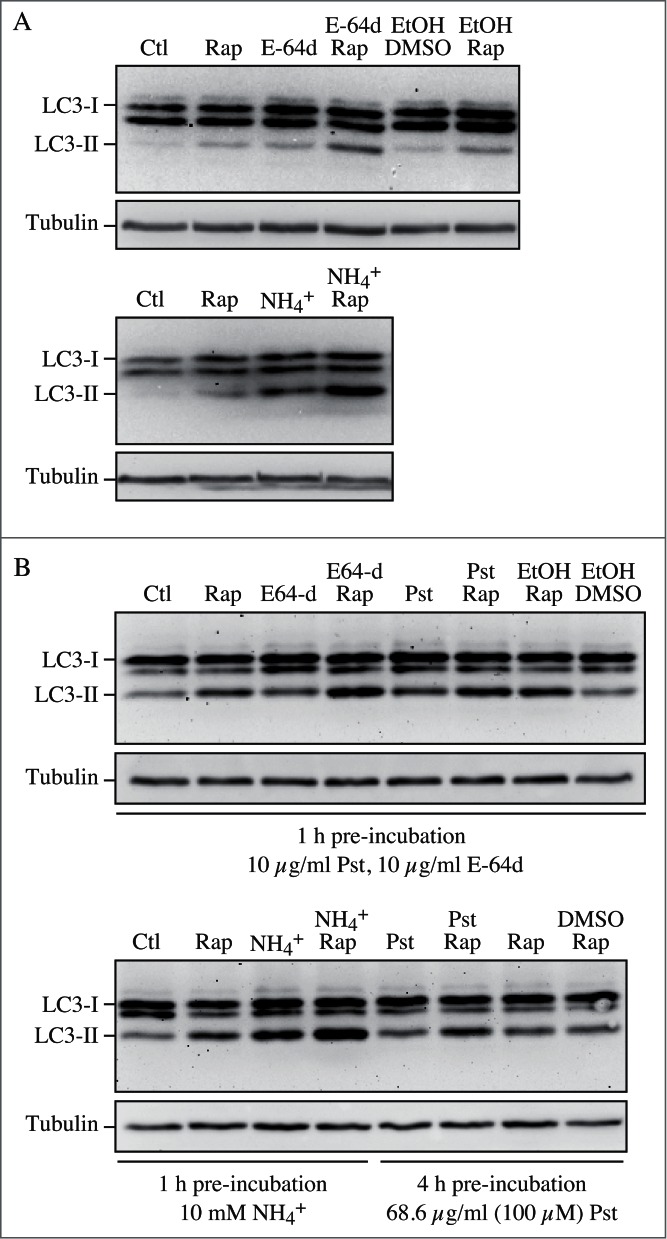

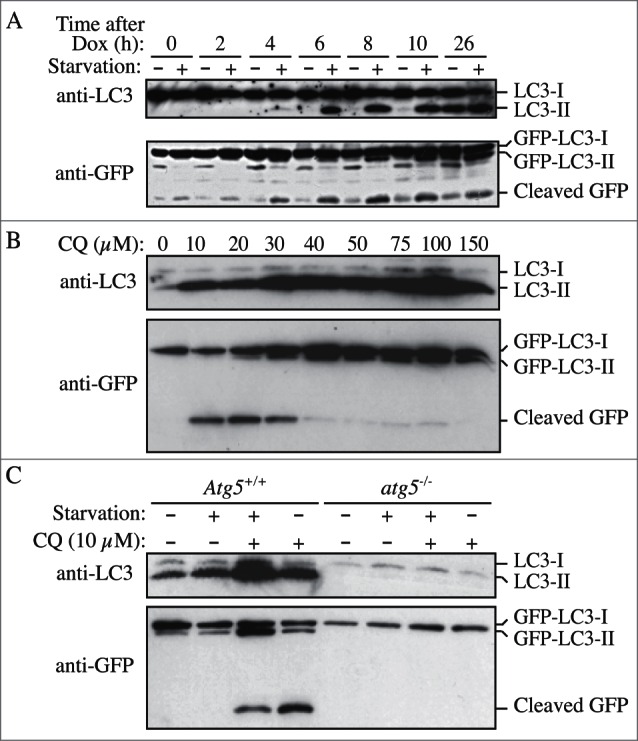

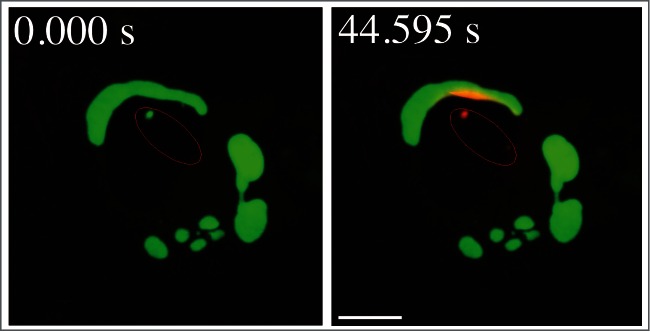

Figure 6.

LC3-I conversion and LC3-II turnover. (A) Expression levels of LC3-I and LC3-II during starvation. Atg5+/+ (wild-type) and atg5-/- MEFs were cultured in DMEM without amino acids and serum for the indicated times, and then subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-LC3 antibody and anti-tubulin antibody. E-64d (10 μg/ml) and pepstatin A (10 μg/ml) were added to the medium where indicated. Positions of LC3-I and LC3-II are marked. The inclusion of lysosomal protease inhibitors reveals that the apparent decrease in LC3-II is due to lysosomal degradation as easily seen by comparing samples with and without inhibitors at the same time points (the overall decrease seen in the presence of inhibitors may reflect decreasing effectiveness of the inhibitors over time). Monitoring autophagy by following steady state amounts of LC3-II without including inhibitors in the analysis can result in an incorrect interpretation that autophagy is not taking place (due to the apparent absence of LC3-II). Conversely, if there are high levels of LC3-II but there is no change in the presence of inhibitors, this may indicate that induction has occurred but that the final steps of autophagy are blocked, resulting in stabilization of this protein. This figure was modified from data previously published in ref. 26, and is reproduced by permission of Landes Bioscience, copyright 2007. (B) Lysates of 4 human adipose tissue biopsies were resolved on 2-12% polyacrylamide gels, as described previously.217 Proteins were transferred in parallel to either a PVDF or a nitrocellulose membrane, and blotted with anti-LC3 antibody, and then identified by reacting the membranes with an HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody, followed by ECL. The LC3-II/LC3-I ratio was calculated based on densitometry analysis of both bands. *, P < 0.05. (C) HEK 293 and HeLa cells were cultured in nutrient-rich medium (DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum) or incubated for 4 h in starvation conditions (Krebs-Ringer medium) in the absence (−) or presence (+) of E-64d and pepstatin at 10 μg/ml each (Inhibitors). Cells were then lysed and the proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE. Endogenous LC3 was detected by immunoblotting. Positions of LC3-I and LC3-II are indicated. In the absence of lysosomal protease inhibitors, starvation results in a modest increase (HEK 293 cells) or even a decrease (HeLa cells) in the amount of LC3-II. The use of inhibitors reveals that this apparent decrease is due to lysosome-dependent degradation. This figure was modified from data previously published in ref. 174, and is reproduced by permission of Landes Bioscience, copyright 2005. (D) Sequence and schematic representation of the different forms of LC3B. The sequence for the nascent (proLC3) from mouse is shown. The glycine at position 120 indicates the cleavage site for ATG4. After this cleavage, the truncated LC3 is referred to as LC3-I, which is still a soluble form of the protein. Conjugation to PE generates the membrane-associated LC3-II form (equivalent to Atg8–PE).

The pattern of LC3-I to LC3-II conversion seems not only to be cell specific, but also related to the kind of stress to which cells are subjected. For example, SH-SY5Y cells display a strong increase of LC3-II when treated with the mitochondrial uncoupler CCCP, a well-known inducer of mitophagy (although it has also been reported that CCCP may actually inhibit mitophagy154). Thus, neither assessment of LC3-I consumption nor the evaluation of LC3-II levels would necessarily reveal a slight induction of autophagy (e.g., by rapamycin). Also, there is not always a clear precursor/product relationship between LC3-I and LC3-II, because the conversion of the former to the latter is cell type-specific and dependent on the treatment used to induce autophagy. Accumulation of LC3-II can be obtained by interrupting the autophagosome-lysosome fusion step (e.g., by depolymerizing acetylated microtubules with vinblastine), by inhibiting the ATP2A/SERCA Ca2+ pump, by specifically inhibiting the V-ATPase with bafilomycin A1155-157 or by raising the lysosomal pH by the addition of chloroquine,158,159 although some of these treatments may increase autophagosome numbers by disrupting the lysosome-dependent activation of MTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin [serine/threonine kinase] complex 1 [MTORC1; note that the original term “mTOR” was named to distinguish the “mammalian” target of rapamycin from the yeast proteins160], a major suppressor of autophagy induction),161,162 or by inhibiting lysosome-mediated proteolysis (e.g., with a cysteine protease inhibitor such as E-64d, the aspartic protease inhibitor pepstatin A, the cysteine, serine and threonine protease inhibitor leupeptin or treatment with bafilomycin A1, NH4Cl or chloroquine158,163,164). Western blotting can be used to monitor changes in LC3 amounts (Fig. 6);26,165 however, even if the total amount of LC3 does increase, the magnitude of the response is generally less than that documented in yeast. It is worth noting that since the conjugated forms of the GABARAP subfamily members are usually undetectable without induction of autophagy in mammalian and other vertebrate cells,166,167 these proteins might be more suitable than LC3 to study and quantify subtle changes in autophagy induction.

In most organisms, Atg8/LC3 is initially synthesized with a C-terminal extension that is removed by the Atg4 protease. Accordingly, it is possible to use this processing event to monitor Atg4 activity. For example, when GFP is fused at the C terminus of Atg8 (Atg8-GFP), the GFP moiety is removed in the cytosol to generate free Atg8 and GFP. This processing can be easily monitored by western blot.168 It is also possible to use assays with an artificial fluorogenic substrate, or a fusion of LC3B to phospholipase A2 that allows the release of the active phospholipase for a subsequent fluorogenic assay,169 and there is a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based assay utilizing CFP and YFP tagged versions of LC3B and GABA-RAPL2/GATE-16 that can be used for high-throughput screening.170 Another method to monitor ATG4 activity in vivo uses the release of Gaussia luciferase from the C terminus of LC3 that is tethered to actin.171 Note that there are 4 Atg4 homologs in mammals, and they have different activities with regard to the Atg8 subfamilies of proteins.172 ATG4A is able to cleave the GABARAP subfamily, but has very limited activity toward the LC3 subfamily, whereas ATG4B is apparently active against most or all of these proteins.139,140 The ATG4C and ATG4D isoforms have minimal activity for any of the Atg8 homologs. In particular because a C-terminal fusion will be cleaved immediately by Atg4, researchers should be careful to specify whether they are using GFP-Atg8/LC3 (an N-terminal fusion, which can be used to monitor various steps of autophagy) or Atg8/LC3-GFP (a C-terminal fusion, which can only be used to monitor Atg4 activity).173

Cautionary notes: There are several important caveats to using Atg8/LC3-II or GABARAP-II to visualize fluctuations in autophagy. First, changes in LC3-II amounts are tissue- and cell context-dependent.153,174 Indeed, in some cases, autophagosome accumulation detected by TEM does not correlate well with the amount of LC3-II (Z. Tallóczy, R.L.A. de Vries, and D. Sulzer, unpublished results; E.-L. Eskelinen, unpublished results). This is particularly evident in those cells that show low levels of LC3-II (based on western blotting) because of an intense autophagic flux that consumes this protein,175 or in cell lines having high levels of LC3-II that are tumor-derived, such as MDA-MB-231.174 Conversely, without careful quantification the detectable formation of LC3-II is not sufficient evidence for autophagy. For example, homozygous deletion of Becn1 does not prevent the formation of LC3-II in embryonic stem cells even though autophagy is substantially reduced, whereas deletion of Atg5 results in the complete absence of LC3-II (see Fig. 5A and supplemental data in ref. 176). The same is true for the generation of Atg8–PE in yeast in the absence of VPS30/ATG6 (see Fig. 7 in ref. 177). Thus, it is important to remember that not all of the autophagy-related proteins are required for Atg8/LC3 processing, including lipidation.177 Vagaries in the detection and amounts of LC3-I versus LC3-II present technical problems. For example, LC3-I is very abundant in brain tissue, and the intensity of the LC3-I band may obscure detection of LC3-II, unless the polyacrylamide crosslinking density is optimized, or the membrane fraction of LC3 is first separated from the cytosolic fraction.44 Conversely, certain cell lines have much less visible LC3-I compared to LC3-II. In addition, tissues may have asynchronous and heterogeneous cell populations, and this variability may present challenges when analyzing LC3 by western blotting.

Second, LC3-II also associates with the membranes of nonautophagic structures. For example, some members of the PCDHGC/γ-protocadherin family undergo clustering to form intracellular tubules that emanate from lysosomes.178 LC3-II is recruited to these tubules, where it appears to promote or stabilize membrane expansion. Furthermore, LC3 can be recruited directly to apoptotic cell-containing phagosome membranes,179,180 macropinosomes,179 the parasitophorous vacuole of Toxoplasma gondii,181 and single-membrane entotic vacuoles,179 as well as to bacteria-containing phagosome membranes under certain immune activating conditions, for example, toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated stimulation in LC3-associated phagocytosis.182,183 Importantly, LC3 is involved in secretory trafficking as it has been associated with secretory granules in mast cells184 and PC12 hormone-secreting cells.185 LC3 is also detected on secretory lysosomes in osteoblasts186 and in amphisome-like structures involved in mucin secretion by goblet cells.187 Therefore, in studies of infection of mammalian cells by bacterial pathogens, the identity of the LC3-II labeled compartment as an autophagosome should be confirmed by a second method, such as TEM. It is also worth noting that autophagy induced in response to bacterial infection is not directed solely against the bacteria but can also be a response to remnants of the phagocytic membrane.188 Similar cautions apply with regard to viral infection. For example, coronaviruses induce autophagosomes during infection through the expression of nsp6; however, coronaviruses also induce the formation of double-membrane vesicles that are coated with LC3-I, the nonlipidated form of LC3 that plays an autophagy-independent role in viral replication.189,190 Similarly, nonlipidated LC3 marks replication complexes in flavivirus (Japanese encephalitis virus)-infected cells and is essential for viral replication.191 Along these lines, during herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection, an LC3+ autophagosome-like organelle that is derived from nuclear membranes and that contains viral proteins is observed,192 whereas influenza A virus directs LC3 to the plasma membrane via a LC3-interacting region (LIR) motif in its M2 protein.193 Moreover, in vivo studies have shown that coxsackievirus (an enterovirus) induces formation of autophagy-like vesicles in pancreatic acinar cells, together with extremely large autophagy-related compartments that have been termed megaphagosomes;194 the absence of ATG5 disrupts viral replication and prevents the formation of these structures.195

Third, caution must be exercised in general when evaluating LC3 by western blotting, and appropriate standardization controls are necessary. For example, LC3-I may be less sensitive to detection by certain anti-LC3 antibodies. Moreover, LC3-I is more labile than LC3-II, being more sensitive to freezing-thawing and to degradation in SDS sample buffer. Therefore, fresh samples should be boiled and assessed as soon as possible and should not be subjected to repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Alternatively, trichloroacetic acid precipitation of protein from fresh cell homogenates can be used to protect against degradation of LC3 by proteases that may be present in the sample. A general point to consider when examining transfected cells concerns the efficiency of transfection. A western blot will detect LC3 in the entire cell population, including those that are not transfected. Thus, if transfection efficiency is too low, it may be necessary to use methods, such as fluorescence microscopy, that allow autophagy to be monitored in single cells. The critical point is that the analysis of the gel shift of transfected LC3 or GFP-LC3 can be employed to follow LC3 lipidation only in highly transfectable cells.196

When dealing with animal tissues, western blotting of LC3 should be performed on frozen biopsy samples homogenized in the presence of general protease inhibitors (C. Isidoro, personal communication; see also Human).197 Caveats regarding detection of LC3 by western blotting have been covered in a review.26 For example, PVDF membranes may result in a stronger LC3-II retention than nitrocellulose membranes, possibly due to a higher affinity for hydrophobic proteins (Fig. 6B; J. Kovsan and A. Rudich, personal communication), and Triton X-100 may not efficiently solubilize LC3-II in some systems.198 Heating in the presence of 1% SDS, or analysis of membrane fractions,44 may assist in the detection of the lipidated form of this protein. This observation is particularly relevant for cells with a high nucleocytoplasmic ratio, such as lymphocytes. Under these constraints, direct lysis in Laemmli loading buffer, containing SDS, just before heating, greatly improves LC3 detection on PVDF membranes, especially when working with a small number of cells (F. Gros, unpublished observations).199 Analysis of a membrane fraction is particularly useful for brain where levels of soluble LC3-I greatly exceed the level of LC3-II.

One of the most important issues is the quantification of changes in LC3-II, because this assay is one of the most widely used in the field and is often prone to misinterpretation. Levels of LC3-II should be compared to actin (e.g., ACTB), but not to LC3-I (see the caveat in the next paragraph), and, ideally, to more than one “housekeeping” protein (HKP). Actin and other HKPs are usually abundant and can easily be overloaded on the gel200 such that they are not detected within a linear range. Moreover, actin levels may decrease when autophagy is induced in many organisms from yeast to mammals. For any proteins used as “loading controls” (including actin, tubulin and GAPDH) multiple exposures of the western blot are generally necessary to ensure that the signals are detected in the linear range. An alternative approach is to stain for total cellular proteins with Coomassie Brilliant Blue and Ponceau Red,201 but these methods are generally less sensitive and may not reveal small differences in protein loading. Stain-Free gels, which also stain for total cellular proteins, have been shown to be an excellent alternative to HKPs.202

It is important to realize that ignoring the level of LC3-I in favor of LC3-II normalized to HKPs may not provide the full picture of the cellular autophagic response.153,203 For example, in aging skeletal muscle the increase in LC3-I is at least as important as that for LC3-II.204,205 Quantification of both isoforms is therefore informative, but requires adequate conditions of electrophoretic separation. This is particularly important for samples where the amount of LC3-I is high relative to LC3-II (as in brain tissues, where the LC3-I signal can be overwhelming). Under such a scenario, it may be helpful to use gradient gels to increase the separation of LC3-I from LC3-II and/or cut away the part of the blot with LC3-I prior to the detection of LC3-II. Furthermore, since the dynamic range of LC3 immunoblots is generally quite limited, it is imperative that other assays be used in parallel in order to draw valid conclusions about changes in autophagy activity.

Fourth, in mammalian cells LC3 is expressed as multiple isoforms (LC3A, LC3B, LC3B2 and LC3C206,207), which exhibit different tissue distributions and whose functions are still poorly understood. A point of caution along these lines is that the increase in LC3A-II versus LC3B-II levels may not display equivalent changes in all organisms under autophagy-inducing conditions, and it should not be assumed that LC3B is the optimal protein to monitor.208 A key technical consideration is that the isoforms may exhibit different specificities for antisera or antibodies. Thus, it is highly recommended that investigators report exactly the source and catalog number of the antibodies used to detect LC3 as this might help avoid discrepancies between studies. The commercialized anti-LC3B antibodies also recognize LC3A, but do not recognize LC3C, which shares less sequence homology. It is important to note that LC3C possesses in its primary amino acid sequence the DYKD motif that is recognized with a high affinity by anti-FLAG antibodies. Thus, the standard anti-FLAG M2 antibody can detect and immunoprecipitate overexpressed LC3C, and caution has to be taken in experiments using FLAG-tagged proteins (M. Biard-Piechaczyk and L. Espert, personal communication). Note that according to Ensembl there is no LC3C in mouse or rat.

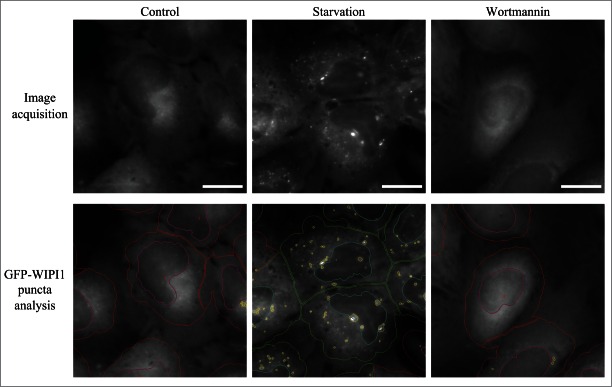

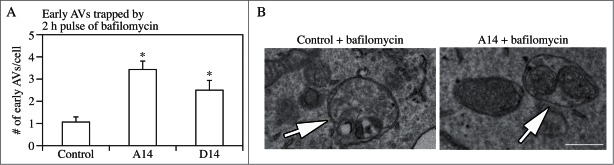

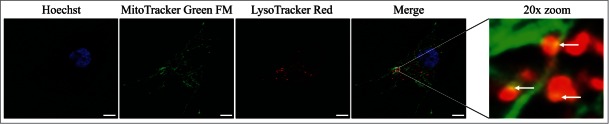

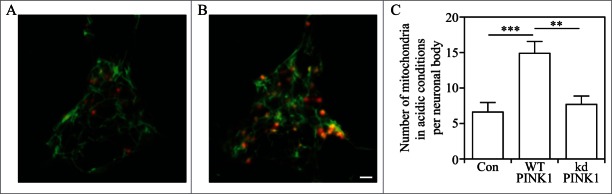

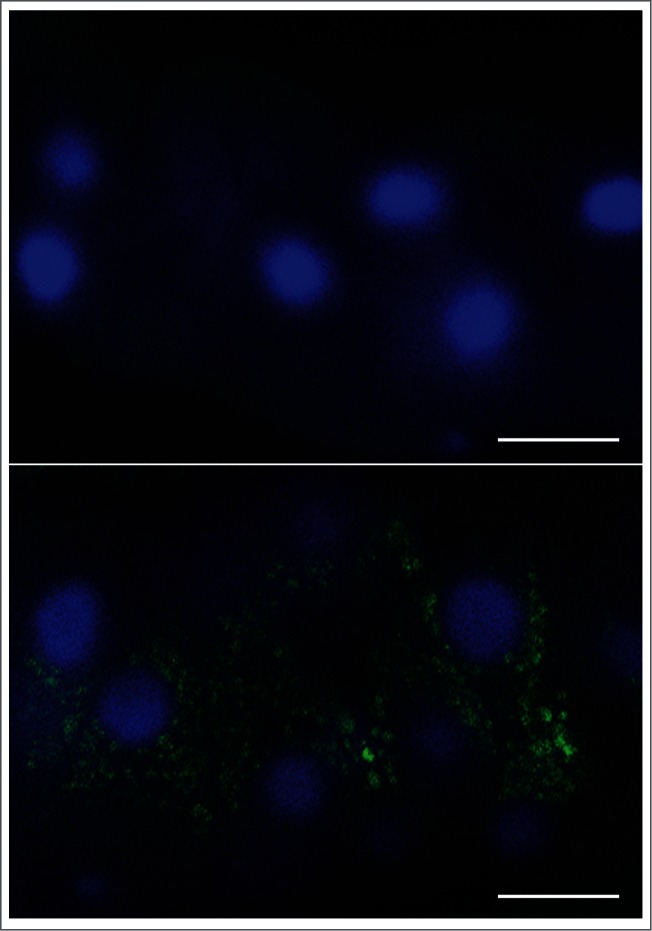

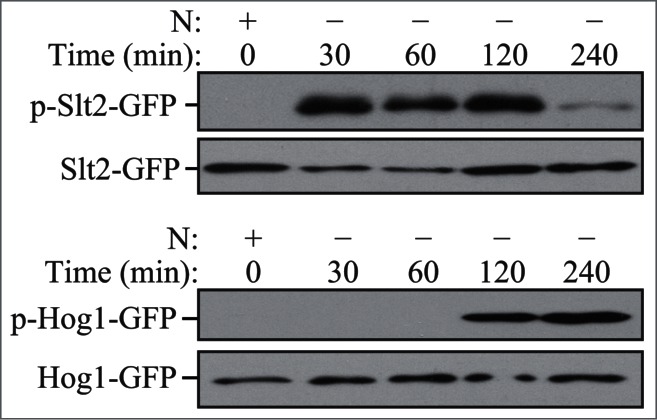

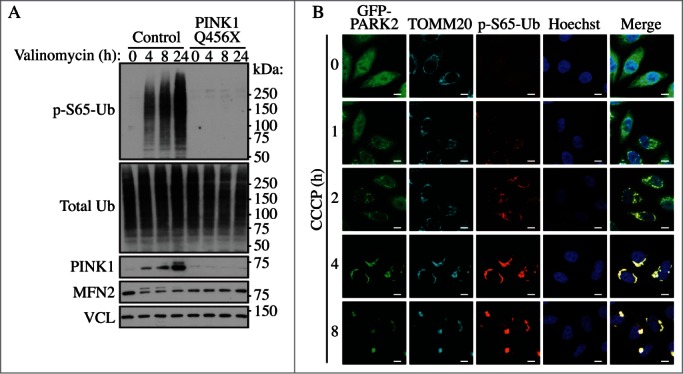

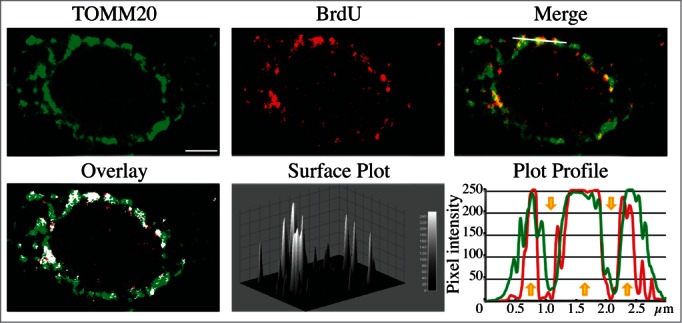

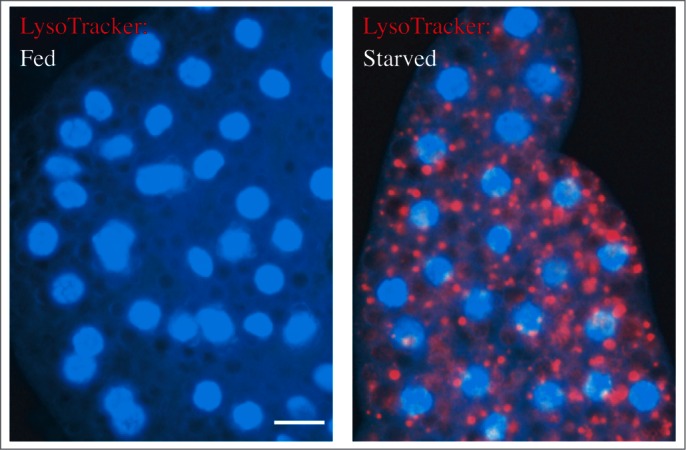

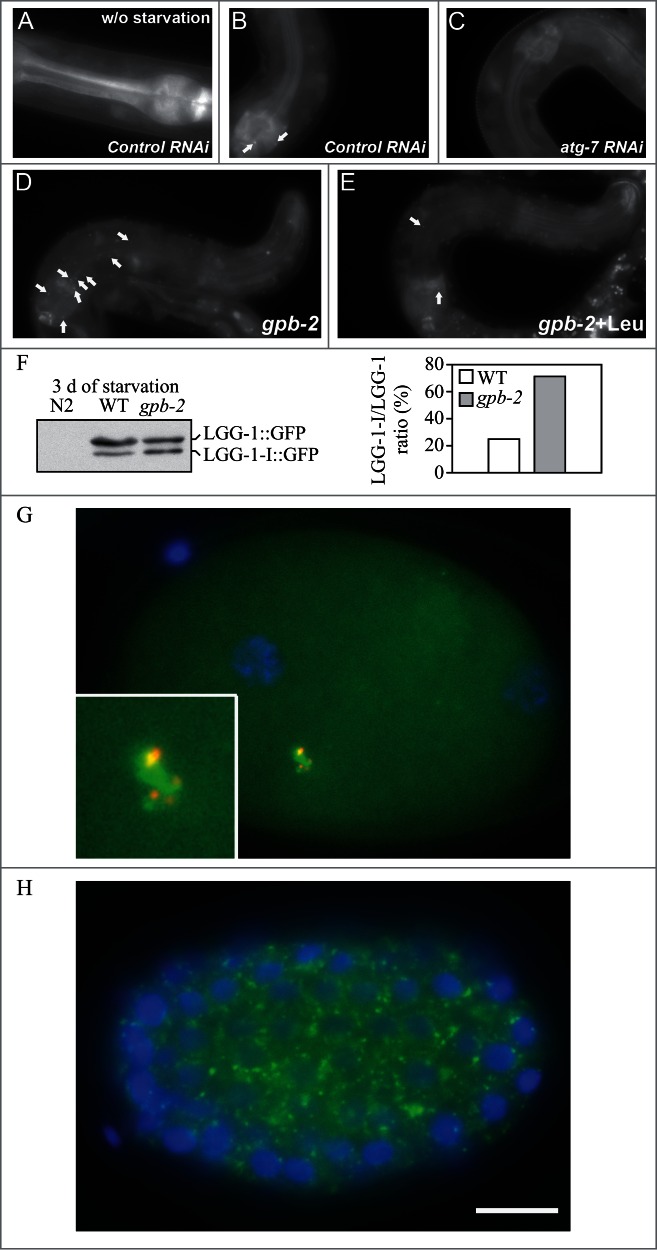

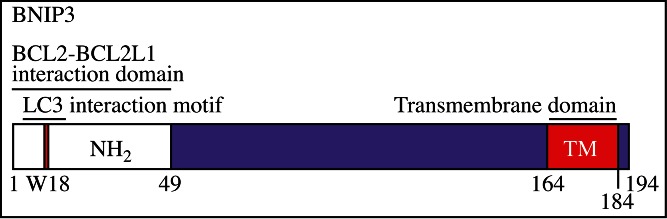

In addition, it is important to keep in mind the other subfamily of Atg8 proteins, the GABARAP subfamily (see above).141,209 Certain types of mitophagy induced by BNIP3L/NIX are highly dependent on GABARAP and less dependent on LC3 proteins.210,211 Furthermore, commercial antibodies for GABARAPL1 also recognize GABARAP,138,143 which might lead to misinterpretation of experiments, in particular those using immunohistochemical techniques. Sometimes the problem with cross-reactivity of the anti-GABARAPL1 antibody can be overcome when analyzing these proteins by western blot because the isoforms can be resolved during SDS-PAGE using high concentration (15%) gels, as GABARAP migrates faster than GABARAPL1 (M. Boyer-Guittaut, personal communication; also see Fig. S4 in ref. 143). Because GABARAP and GABARAPL1 can both be proteolytically processed and lipidated, generating GABARAP-I or GABARAPL1-I and GABARAP-II or GABARAPL1-II, respectively, this may lead to a misassignment of the different bands. As soon as highly specific antibodies that are able to discriminate between GABARAP and GABARAPL1 become available, we strongly advise their use; until then, we advise caution in interpreting results based on the detection of these proteins by western blot. Antibody specificity can be assessed after complete inhibition of GABARAP (or any other Atg8 family protein) expression by RNA interference.143,167 In general, we advise caution in choosing antibodies for western blotting and immunofluorescence experiments and in interpreting results based on stated affinities of antibodies unless these have been clearly determined. As with any western blot, proper methods of quantification must be used, which are, unfortunately, often not well disseminated; readers are referred to an excellent paper on this subject (see ref. 212). Unlike the other members of the GABARAP family, almost no information is available on GABARAPL3, perhaps because it is not yet possible to differentiate between GABA-RAPL1 and GABARAPL3 proteins, which have 94% identity. As stated by the laboratory that described the cloning of the human GABARAPL1 and GABARAPL3 genes,209 their expression patterns are apparently identical. It is worth noting that GABARAPL3 is the only gene of the GABARAP subfamily that seems to lack an ortholog in mice.209 GABARAPL3 might therefore be considered as a pseudogene without an intron that is derived from GABARAPL1. Hence, until new data are published, GABARAPL3 should not be considered as the fourth member of the GABARAP family.