ABSTRACT

Autophagy and apoptosis, which could be induced by common stimuli, play crucial roles in development and disease. The functional relationship between autophagy and apoptosis is complex, due to the dual effects of autophagy. In the Bombyx Bm-12 cells, 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E) treatment or starvation-induced cell death, with autophagy preceding apoptosis. In response to 20E or starvation, BmATG8 was rapidly cleaved and conjugated with PE to form BmATG8–PE; subsequently, BmATG5 and BmATG6 were cleaved into BmATG5-tN and BmATG6-C, respectively. Reduction of expression of BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 by RNAi decreased the proportion of cells undergoing both autophagy and apoptosis after 20E treatment or starvation. Overexpression of BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 induced autophagy but not apoptosis in the absence of the stimuli, but promoted both autophagy and apoptosis induced by 20E or starvation. Notably, overexpression of cleavage site-deleted BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 increased autophagy but not apoptosis induced by 20E or starvation, whereas overexpression of BmAtg5-tN and BmAtg6-C was able to directly trigger apoptosis or promote the induced apoptosis. In conclusion, being cleaved into BmATG5-tN and BmATG6-C, BmATG5 and BmATG6 mediate apoptosis following autophagy induced by 20E or starvation in Bombyx Bm-12 cells, reflecting that autophagy precedes apoptosis in the midgut during Bombyx metamorphosis.

Keywords: autophagy, apoptosis, BmATG5, BmATG6, BmATG8, BmATG5-tN, BmATG6-C, BmATG8–PE, starvation, 20-hydroxyecdysone

Introduction

Autophagy, a strictly regulated self-degradation process that plays critical roles in development and disease is conserved in organisms from yeast to mammals.1 Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy), a highly regulated lysosome-dependent process for degradation and recycling of cellular components, is involved in cell survival or cell death in response to unfavorable conditions. During autophagy, the cytoplasm and intracellular organelles are sequestered within double-membrane autophagosomes and delivered to lysosomes for bulk degradation.2 Apoptosis is the process of rapid demolition of cellular structures and organelles, which leads to cellular shrinkage with nuclear chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation and eventually cell death.3

Maturation of autophagosome is governed by a series of autophagy-related (Atg) genes and several ATG protein complexes.1 Autophagosome initiation requires the ULK1/ATG1-ATG13 protein kinase complex; autophagosome nucleation involves the BECN1/Beclin 1/ATG6-PIK3C3/Vps34 (catalytic subunit of the class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [PtdIns3K]) complex; and autophagosome expansion and completion is mediated by 2 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems: ATG12–ATG5-ATG16L1 and ATG8–PE.4,5 The apoptotic machinery is evolutionarily conserved in higher eukaryotes; apoptosis is triggered by extrinsic cellular stress signals, and characterized by mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and the release of mitochondrial CYCS (cytochrome C, somatic) into the cytosol, which results in the activation of initiator caspases and effector caspases.6 In recent decades, the mechanisms underlying apoptosis have been well documented, while many questions remain regarding to autophagy.4

The functional relationship between autophagy and apoptosis is complex. Under certain circumstances, autophagy prevents cell death from apoptosis, whereas extensive autophagy causes cell death.7 Autophagy and apoptosis may be triggered by the same upstream signals; in some cases, both processes are induced, and in other cases, these processes develop in a mutually exclusive manner. At the molecular level, autophagy and apoptosis may share common pathways to either link or polarize the cellular responses to stress.6 Although significant advances have recently been made regarding the functional relationship between autophagy and apoptosis, the detailed molecular mechanism requires further investigation.8

Starvation is a common stimulus for both autophagy and apoptosis. Starvation triggers autophagy by regulating the PI3K-AMPK-TORC1 interactions and thus phosphorylation of the ATG1-ATG13 complex.4,9 In some cases, starvation induces a high level of autophagy, which precedes apoptosis and might boost together with apoptosis to accelerate the irreversible death of cell in mammals.10,11 In these cases, the truncated fragments N63ATG4D (47 kDa),12 ATG5t (24 kDa; ATG5-tN)13,14 and BECN1-C (alternatively cleaved into 35-kDa or 37-kDa fragments; ATG6-C1 or ATG6-C2)15,16 act as molecular links between autophagy and apoptosis. ATG5t and BECN1-C trigger apoptotic signaling by releasing CYCS to the cytosol from the mitochondria, showing autophagy-mediated apoptosis.17,18 In Drosophila, Cyt-c is not involved in the activation of Decay/Caspase-3;19,20 moreover, knockout of Cyt-c does not inhibit apoptosis.21 These results show that Cyt-c might play little to no role in regulating apoptosis in Drosophila.22 By contrast, a number of studies have revealed that apoptosis in lepidopteran insects exhibits a similar process of Cyt C release as that observed in mammals. In a cell line (Sf21) of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, actinomycin D (AD) induces apoptosis, combined with the reduction of mitochondrial membrane potential and the release of Cyt C from the mitochondria to the cytosol.23,24 In Sf9 cells treated with oxidants or H2O2 and UVB irradiation, the release of Cyt C from the mitochondria to the cytosol is followed by Caspase-3 activation.25 Moreover, a series of biochemical experiments determine that Cyt C is required for lepidopteran apoptosis at an early stage and suggest that the chemical induction of TP53/p53-Bcl-2-Bax-Cyt C signaling is indispensable for apoptosis in lepidopteran cells.24,26

In Drosophila and the silkworm, Bombyx mori, the molting hormone (20-hydroxyecdysone, 20E) is both necessary and sufficient to induce autophagy and apoptosis during metamorphosis.8,27,28 20E and its receptor complex (20E-EcR-USP) trigger the transcriptional cascade of 20E primary-response genes (including Br-C, E74, E75 and E93) and thus 20E secondary-response genes. The 20E-response genes include many apoptosis genes22,27,29 and most Atg genes.27,28 In addition, 20E blocks the PI3K-TORC1 pathway to initiate autophagy.28,30 Interestingly, 20E slowly reduces food consumption and then induces starvation-like conditions during molting and pupation in Bombyx, providing a correlation between 20E and starvation in the induction of both autophagy and apoptosis.31

In Drosophila, the relationship between autophagy and caspases appears to be context specific, varying by developmental stage and cell type.8 During metamorphosis, many obsolete larval tissues undergo massive destruction mainly by autophagic cell death.8,27 Both autophagy and caspases, which function in parallel, contribute to autophagic cell death in the dying salivary gland, but autophagy plays a more important role than caspases.32,33 Moreover, autophagy, but not caspases, governs cell death in the midgut.34 A balancing crosstalk occurs between autophagy and caspase activity in the remodeling fat body, as the inhibition of autophagy induces caspase activity and the inhibition of apoptosis induces autophagy.35,36

During Bombyx metamorphosis, autophagy and apoptosis occur simultaneously in the silk gland,37,38 and fat body.28,29,39 Importantly, we found that autophagy precedes apoptosis in the midgut.40 In this study, we discovered that being cleaved into BmATG5-tN and BmATG6-C, BmATG5 and BmATG6 mediate apoptosis following autophagy induced by 20E or starvation in Bombyx Bm-12 cells, reflecting that autophagy precedes apoptosis in the midgut during Bombyx metamorphosis.

Results

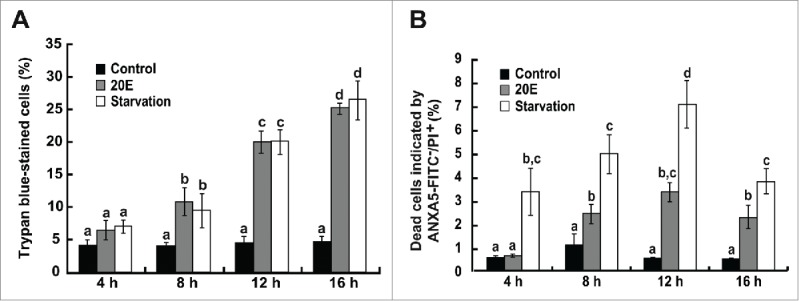

Both 20E and starvation induce cell death in Bm-12 cells

As introduced above, 20E and starvation are 2 important common stimuli of cell death in insects, inducing both autophagy and apoptosis. To study the induction of cell death by 20E and starvation, Bm-12 cells were treated with 10 μM 20E or were starved with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 0, 4, 8, 12, or 16 h. Trypan blue staining, which detects all kinds of cell death, was induced by approximately 10% after 8 h of treatments and steadily increased to approximately 30% at 16 h, indicating that cell death was significantly induced by 20E and starvation in Bm-12 cells (Fig. 1A and S1A). After costaining with ANXA5 (annexin V)-FITC and propidium iodide (PI), normal, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and dead cells were counted (Fig. 1B and S1B). Analysis of the cells indicated by PI staining only showed that 20E and starvation significantly induced cell death in Bm-12 cells (Fig. 1B and S1B). In spite of slight differences of the 2 experimental results, it is conclusive that both 20E and starvation induce significant cell death in Bm-12 cells. In the following, we studied whether and how autophagy and apoptosis are induced by the stimuli in Bm-12 cells.

Figure 1.

Cell death induced by 20E and starvation in Bm-12 cells. Cell death was detected by trypan blue staining, and ANXA5-FITC and PI staining after 20E treatment or starvation in Bm-12 cells for 4, 8, 12, and 16 h. (A) The quantification of trypan blue-stained cells. (B) The quantification of dead cells stained by PI only.

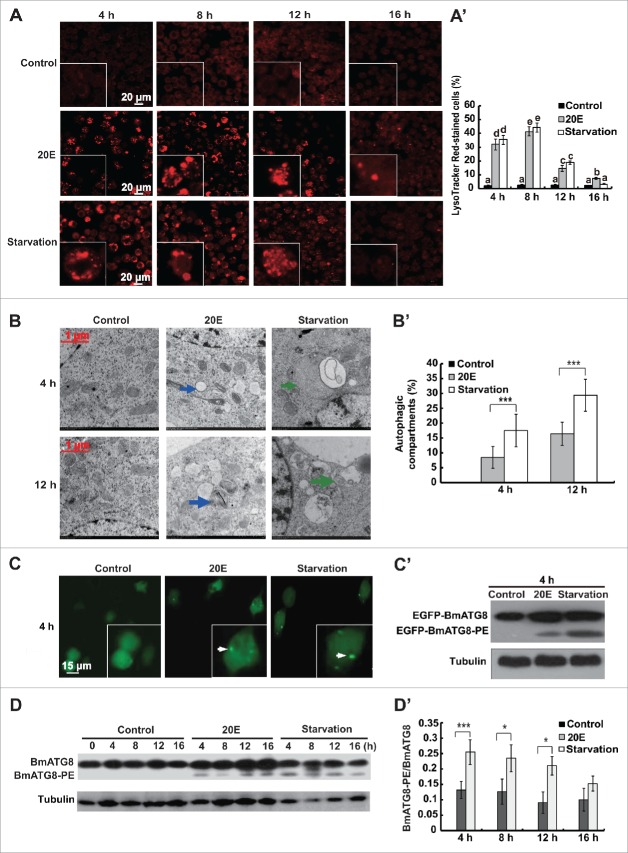

Both 20E and starvation induce autophagy

LysoTracker Red DND-99 staining greatly increased in Bm-12 cells 4–8 h after 20E treatment or starvation, but steadily decreased thereafter (Fig. 2A and 2A′). As observed via TEM, autophagic compartments were evident in Bm-12 cells 4 h after 20E treatment or starvation, and increased at 12 h after treatments (Fig. 2B and 2B′). After transient overexpression of pIEX-4-Egfp-BmAtg8 for 48 h and followed by 20E treatment or starvation for 4 h, a punctate pattern of EGFP-BmATG8 aggregation was induced in the cytoplasm of Bm-12 cells but not in the untreated control cells (Fig. 2C). Compared with the control cells in which only EGFP-BmATG8 (41.5 kDa) was detected by western blotting with an antibody against EGFP, both EGFP-BmATG8 and EGFP-BmATG8–PE (39.5 kDa) were detected in Bm-12 cells after 20E treatment or starvation for 4 h (Fig. 2C'). As detected by western blotting with the antibody against BmATG8, which was shown to be able to detect the endogenous BmATG8 and BmATG8–PE in the midgut and fat body in previous publications,28,40 the BmATG8–PE conjugation formed after treatment with 20E or starvation, reaching a peak at 4 to 8 h and then decreasing from 12 h to 16 h (Fig. 2D and 2D'). In addition, Bm-12 cells were treated with various 20E concentration (1, 2.5, 5, 10, or 20 µM) for 4 h to check the dose-dependent LysoTracker Red staining and ATG8–PE conjugation. LysoTracker Red staining gradually increased from 1 μM to 20 μM 20E (Fig. S2A). BmATG8–PE was not detected after 4-h exposure to 1 μM 20E, although the levels of BmATG8–PE increased following exposure to 2.5 μM to 5 μM 20E, there were no further increases in response to doses of 5 μM to 20 μM 20E (Fig. S2B and 2B′). The combined data indicate that both 20E and starvation are able to induce significant autophagy in Bm-12 cells at 4 to 8 h.

Figure 2.

Autophagy induced by 20E and starvation in Bm-12 cells. Autophagy was monitored by LysoTracker Red staining, TEM, punctate pattern of EGFP-ATG8, and ATG8–PE conjugation after 20E treatment or starvation in Bm-12 cells. (A) and (A′) LysoTracker Red staining (red, magnification 40 X) after 20E and starvation treatments for 4, 8, 12, and 16 h. The chart (A′) shows the quantification of LysoTracker Red staining in (A). (B) and (B′) TEM observation after 20E treatment or starvation for 4 h and 12 h (75000 X). The arrows denote autophagic compartments, autophagosomes or autolysosomes. The chart (B′) shows the quantification of autophagic compartments in (B). (C) and (C') The Egfp-BmAtg8-overexpressing Bm-12 cells were treated with 20E or starvation for 4 h. The aggregating puncta of EGFP-ATG8 (denoted by the arrows) were observed by fluorescence microscopy (green, 40 X) (C). EGFP-ATG8 and EGFP-ATG8–PE were detected by western blotting with EGFP antibody, and α-tubulin as a loading control (C'). (D) and (D') ATG8 and ATG8–PE were detected by western blotting with the antibody against BmATG8 after 20E treatment and starvation for 4, 8, 12, and 16 h. The chart (D') shows the quantification of BmATG8–PE/BmATG8 in (D).

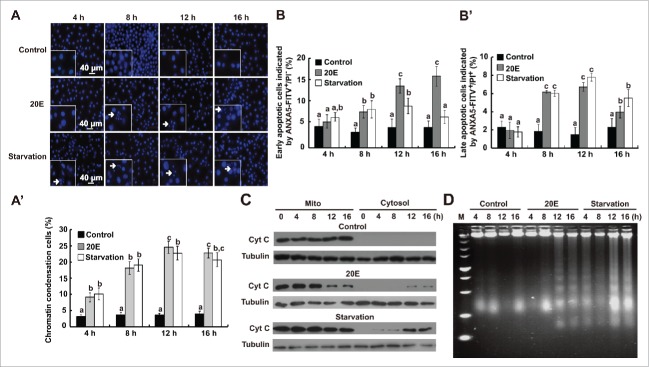

Both 20E and starvation induce apoptosis

Hoechst staining showed that 20E treatment or starvation gradually increased chromatin condensation in Bm-12 cells from 4 h to 12 h (Fig. 3A and 3A′). Analysis of the early apoptotic cells indicated by ANXA5-FITC only and late apoptotic cells indicated by ANXA5-FITC and PI showed that 20E and starvation steadily promoted apoptosis in Bm-12 cells from 4 h to 12 h (Fig. 3B, 3B′ and S1B). Western blotting with a Cyt C polyclonal antibody revealed that the level of Cyt C in the mitochondria decreased from 12 h to 16 h after 20E treatment; in contrast, the level of Cyt C in the cytosol significantly increased from 12 h to 16 h. Starvation induced mitochondrial Cyt C release after 4-h treatment, being faster and stronger than that induced by 20E treatment (Fig. 3C). These results confirmed the release of Cyt C from the mitochondria to the cytosol during apoptosis in Bombyx Bm-12 cells and suggested that the release of Cyt C could be used as an effective indicator of apoptosis in lepidopteran insects. Another apoptotic feature, DNA fragmentation, was detected at 12 h after 20E addition and 4 h after starvation, the fragmented DNA was observed up to 16 h, which was consistent with the trend detected by release of Cyt C showing faster and stronger induction of apoptosis by starvation than 20E (Fig. 3D). In conclusion, 20E and starvation gradually induce apoptosis in Bm-12 cells.

Figure 3.

Apoptosis induced by 20E or starvation in Bm-12 cells. Apoptosis was monitored by Hoechst 33258 staining, ANXA5-FITC and PI labeling with flow cytometry, western blotting of Cyt C, and DNA ladder after 20E treatment and starvation for 4, 8, 12, and 16 h in Bm-12 cells. (A) and (A′) Hoechst staining (blue, 40 X). The arrows in the inserts denote chromatin condensation cells (A). The chart (A′) show the quantification of chromatin condensation cells in (A). (B) and (B′) Quantifications of ANXA5-FITC and PI staining in Figure S1 B. The early apoptotic cells are indicated by ANXA5-FITC only (B), the late apoptotic cells are indicated by ANXA5-FITC and PI (B′). (C) Western blotting of Cyt C in the mitochondria (left lanes) as well as cytosol (right lanes) with a Cyt C antibody. Lacking a proper loading control for mitochondria proteins, α-tubulin, the loading control for total proteins, is used here and thereafter. (D) DNA ladder. M, marker.

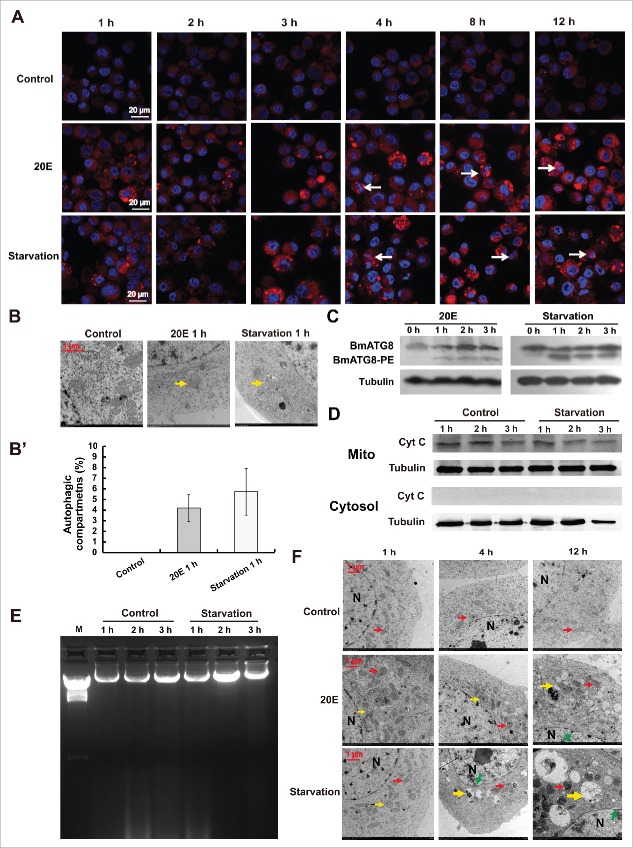

Autophagy precedes apoptosis after 20E treatment or starvation

The above experimental data (Fig. 2 and 3) suggest that autophagy might precede apoptosis in Bm-12 cells after 20E treatment or starvation; we thus verified this hypothesis within 3 h after treatments. Interestingly, 20E and starvation induced LysoTracker Red staining, autophagic compartment formation, and BmATG8–PE conjugation as early as 1 h after treatments (Fig. 4A to 4C). Moreover, the LysoTracker Red staining as well as BmATG8–PE conjugation steadily increased with the dose of 20E addition from 1 µM to 20 µM (Fig. S2C, S2D and S2D'). Consistent with the previous in vivo and in vitro experiments of 20E treatment in Bombyx,28,29 10 µM of 20E was used in the following studies throughout the paper. The above experimental data showed that Cyt C release and DNA fragmentation began at 12 h after 20E treatment and at 4 h after starvation (Fig. 3C and 3D). Nevertheless, starvation was not able to induce Cyt C release and DNA fragmentation even at 3 h after treatments (Fig. 4D and 4E). Next, we investigated whether 20E and starvation induce autophagy and apoptosis within the same Bm-12 cells. As observed via TEM analysis, autophagic compartments but not apoptotic features (including impairments of mitochondria morphology and nuclear membrane integrity) occurred at 1 h and 4 h after 20E treatment and at 1 h after starvation; however, both autophagic compartments and apoptotic features were present in some Bm-12 cells at 12 h after 20E treatment and at 4 h and 12 h after starvation (Fig. 4F). In addition, LysoTracker Red and Hoechst double staining also suggested that both autophagy and apoptosis simultaneously occurred in some Bm-12 cells at 4 to 12 h after 20E treatment and starvation (Fig. 4A). The combined data demonstrate that 20E and starvation induce autophagy faster than apoptosis in Bm-12 cells. In mammals, ATG5 and BECN1 are confirmed as the molecular switches between autophagy and apoptosis. In the following, we investigated whether BmATG5 and BmATG6 play similar roles in switching autophagy to apoptosis after 20E treatment and starvation in Bm-12 cells.

Figure 4.

Autophagy but not apoptosis induced by 20E or starvation was detected within 3 h. (A) LysoTracker Red (red) and Hoechst (blue) double staining (magnification 60 X). LysoTracker Red staining began at 1 h after 20E treatment and starvation, chromatin condensation indicated by Hoechst staining (denoted by arrows, costained with LysoTracker Red) began in some cells at 4 h after 20E treatment and starvation. (B) and (B′) TEM observation after 20E treatment or starvation for 1 h (75000 X). The arrows denote autophagic compartments, autophagosomes or autolysosomes. The chart (B′) shows the quantification of autophagic compartments in (B). (C) ATG8 and ATG8–PE were detected by western blotting with the antibody against BmATG8 after 20E treatment and starvation for 1, 2, and 3 h. (D) Western blotting of Cyt C in the mitochondria (upper panel) as well as cytosol (bottom panel) after 20E or starvation treatments for 1, 2, and 3 h with a Cyt C antibody. (E) DNA ladder detected in Bm-12 cells after starvation for 1, 2, and 3 h. M: marker. (F) As observed via TEM analysis, autophagic compartments (autophagosome and autolysosome) but not apoptotic features (including impairments of mitochondria morphology and nuclear membrane integrity) occurred at 1 h and 4 h after 20E treatment and at 1 h after starvation; however, both autophagic compartments and apoptotic features were present in some Bm-12 cells at 12 h after 20E treatment and at 4 h and 12 h after starvation. Yellow arrows, autophagosome or autolysosome; red arrows, mitochondria; N, nucleus; green arrows denotes the abnormal morphology of the nuclear membrane.

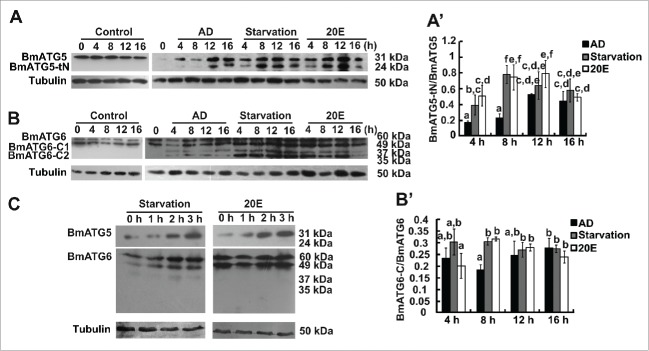

BmATG5 and BmATG6 are cleaved following 20E- or starvation-induced autophagy

As introduced above, mammalian ATG5t and BECN1-C act as molecular links between autophagy and apoptosis.12,18 The cleavage sites in BmATG5 and BmATG6 were predicted by comparison of the homology proteins between human (Homo sapiens; NP_004840.1, NP_003757.1), mouse (Mus musculus; NP_444299.1, NP_062530.2), fly (D. melanogaster; NM_132162.4, NP_651209.1), and nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans; NP-490885.3) (Fig. S3 and S4). One calpain cleavage site was predicted in BmATG5, while 2 caspase-3, −7, or −8 cleavage sites were found in BmATG6 (Fig. S5A and S5B). Incubating the recombinant Bombyx BmATG5 and BmATG6 proteins expressed in E. coli with the appropriate enzyme, µ-Calpain-treated BmATG5 was cleaved into one active fragment (BmATG5-tN, 24 kDa) (Fig. S5C), and Caspase-3-treated BmATG6 was cleaved into 2 active fragments (BmATG6-C1/35 kDa and BmATG6-C2/37 kDa) (Fig. S5D), supporting the predicted results above. To further confirm the above results, cleavage site-deleted BmAtg5 (V5-BmAtg5193–201Δ) or BmAtg6 (V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ,120–123Δ), which was fused with the V5 tag at the N terminus, was overexpressed in Bm-12 cells, followed with 20E treatment or starvation for 12 h. As detected by western blotting with the V5 antibody, the cleavage was not able to be detected any longer (Fig. S5E and S5F), confirming the authenticity of the cleavage sites of both BmATG5 and BmATG6.

Two distinct antibodies against Bombyx BmATG5 and BmATG6 were generated, which are able to detect the full-length and cleaved fragments of BmATG5 and BmATG6 in response to 20E and starvation in Bm-12 cells (Fig. 5A and 5B). Similar to the pattern in mammals,16 an additional band (60 kDa) corresponding to BmATG6, which may be a modified version of full-length form (49 kDa), was detected by western blotting (Fig. 5B). In order to confirm the cleavage of BmATG5 and BmATG6 during apoptosis, the Bm-12 cells were treated with the apoptosis inducer AD as a positive control. As expected, AD led to cleavage of BmATG5 and BmATG6 at 12 h and 4 h after treatment, respectively, while BmATG5 and BmATG6 were cleaved into the active forms at 4 h after 20E treatment or starvation (Fig. 5A and 5B′). Importantly, 20E or starvation did not induce cleavage of BmATG5 or BmATG6 within 3 h after treatments (Fig. 5C), showing that BmATG5 and BmATG6 are cleaved following 20E- or starvation-induced autophagy.

Figure 5.

Cleavage of BmATG5 and BmATG6 following 20E- or starvation-induced autophagy in Bm-12 cells. (A) and (A′) Protein levels of BmATG5 as well as its cleaved form after 20E treatment or starvation for 4, 8, 12, and 16 h are detected by western blotting using AD treated cells as positive controls (B). The chart (A′) shows the quantification of cleaved BmATG5 in (A). (B) and (B′) Protein levels of BmATG6 as well as its cleaved forms after 20E or starvation treatments for 4, 8, 12, and 16 h are detected by western blotting using AD treated cells as positive controls (B). The chart (B′) shows the quantification of cleaved BmATG6 in (B). (C) Western blotting showing noncleavage of BmATG5, BmATG6 after 20E treatment or starvation within 3 h.

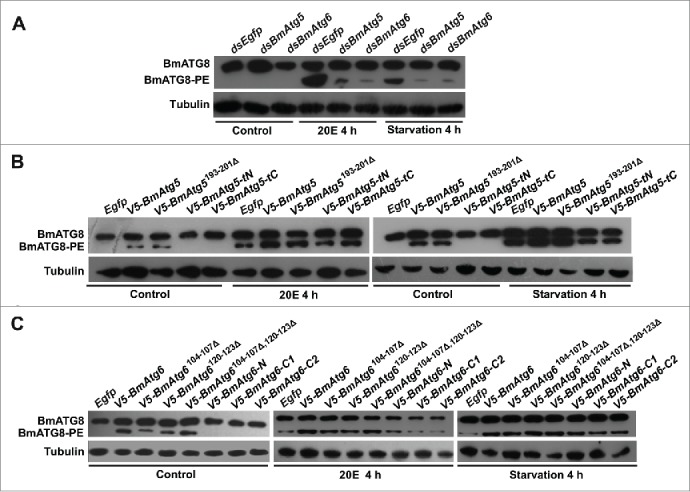

BmATG5 and BmATG6 mediate autophagy

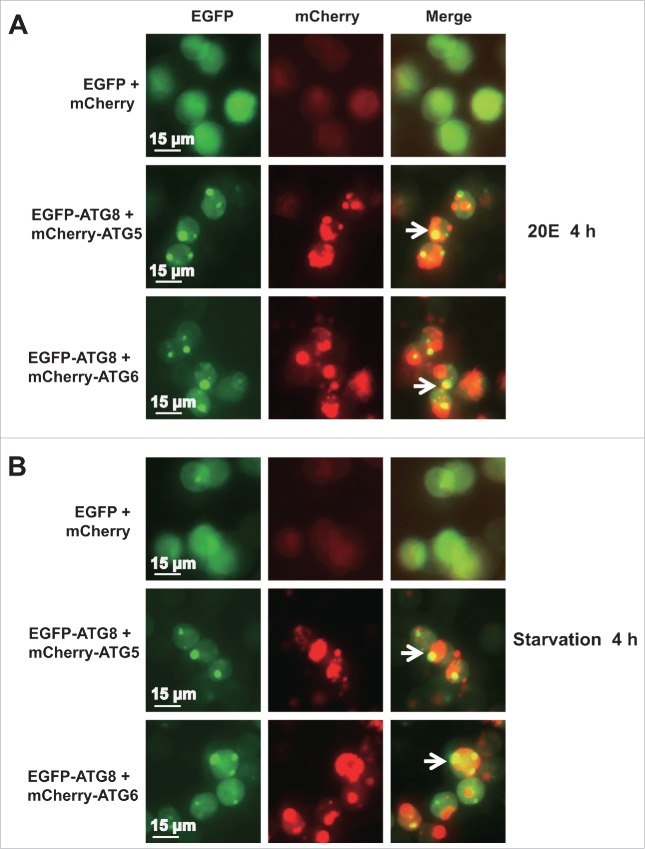

After mcherry-BmAtg5 or mcherry-BmAtg6 (red) was cotransfected with Egfp-BmAtg8 (green), aggregating puncta of mCherry-BmATG5 or mCherry-BmATG6 were observed in the cytoplasm after 20E treatment or starvation, and some colocalized with EGFP-BmATG8, suggesting that BmATG5 and BmATG6 were involved in the formation and maturation of autophagosome in response to the 2 stimuli (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

BmATG5 or BmATG6 colocalized with BmATG8 during 20E- or starvation-induced autophagy. After mCherry-BmAtg5 or mCherry-BmAtg6 cotransfected with Egfp-BmAtg8 for 48 h, the Bm12 cells were subsequently treated with 20E (A) or starved (B) for 4 h, the aggregating puncta of EGFP-ATG8 (green) were colocalized with mCherry-BmATG5 or mCherry-BmATG6 (red, 40X).

As shown above (Figs. 2D and 4C), the protein level of BmATG8–PE can be used as an effective indicator of autophagy in Bm-12 cells, and was used to monitor autophagy hereafter. RNAi of BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 dramatically decreased their mRNA and protein levels (Fig. S6), and reduced BmATG8–PE conjugation induced by 20E and starvation in Bm-12 cells (Fig. 7A). In contrast, overexpression of BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 (V5-BmAtg5, V5-BmAtg6) (Fig. S7) was sufficient to induce BmATG8–PE conjugation in the absence of the stimuli, and enhanced BmATG8–PE conjugation induced by 20E and starvation (Fig. 7B and 7C). Thus, we questioned whether other forms of BmATG5 and BmATG6 affect the autophagy flux. First, the cleavage site-deleted forms of BmAtg5 (V5- BmAtg5193–201Δ) or BmAtg6 (V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ, V5-BmAtg6120–123Δ, V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ,120–123Δ) were transfected into Bm-12 cells. Notably, cleavage site-deleted forms of BmATG5 and BmATG6 had similar stimulatory effects on ATG8–PE conjugation to their full-length forms (Fig. 7B and 7C). By contrast, the fragments V5-BmATG5-tN, V5-BmATG6-C1 or V5-BmATG6-C2 neither cause ATG8–PE conjugation in the absence of the stimuli nor enhance ATG8–PE conjugation induced by 20E and starvation (Fig. 7B and 7C). This result demonstrated that autophagy flux depends on the full-length forms of BmATG5 and BmATG6.

Figure 7.

BmATG5 and BmATG6 are required for 20E- or starvation-induced autophagy in Bm-12 cells. (A) Reduction of BmATG8–PE conjugation after BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 RNAi followed by 20E or starvation treatments for 4 h. (B) Induction of BmATG8–PE conjugation after overexpression of full-length and the cleavage site-deleted form of BmAtg5 in the absence of stimuli (controls); promotion of BmATG8–PE conjugation after overexpression of full-length and the cleavage site-deleted forms after 20E treatment or starvation for 4 h. (C) Induction of BmATG8–PE conjugation after overexpression of full-length, single or double cleavage site-deleted forms of BmAtg6 in the absence of stimuli (controls); promotion of BmATG8–PE conjugation after overexpression of the site-deleted forms of BmAtg6 after 20E treatment or starvation for 4 h.

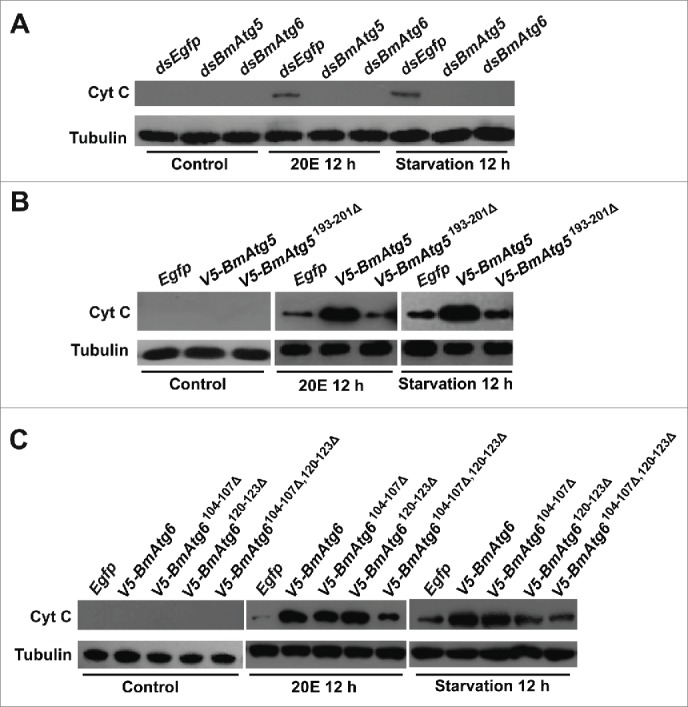

BmATG5 and BmATG6 are involved in apoptosis

After BmATG5 and BmATG6 were confirmed to play key roles in autophagy, we questioned whether these proteins act as molecular links between autophagy and apoptosis. As shown above (Figs. 3C and 4D), Cyt C release can be used as an effective indicator of apoptosis in Bm-12 cells. Compared with control cells, RNAi of BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 nearly eliminated Cyt C in the cytosol induced by 20E and starvation (Fig. 8A); by contrast, overexpression of BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 increased it (Fig. 8B and 8C). Importantly, impairment of the cleavage of BmATG5 and BmATG6 by overexpressing cleavage site-deleted BmAtg5 (V5-BmAtg5193–201Δ) or double cleavage site-deleted BmAtg6 (V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ,120–123Δ) was not able to enhance Cyt C level in the cytosol induced by 20E and starvation (Fig. 8B and 8C), showing the important function of BmATG5 or BmATG6 cleaved fragments in apoptosis.

Figure 8.

BmATG5 and BmATG6 promote 20E- or starvation-induced apoptosis in Bm-12 cells. (A) Cyt C release induced by 20E treatment or starvation was impaired by BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 RNAi. (B) Cyt C release induced by 20E treatment or starvation was promoted by overexpression of full-length but not the cleavage site-deleted form of BmAtg5. (C) Cyt C release induced by 20E treatment or starvation was promoted by overexpression of full-length and single cleavage site-deleted forms of BmAtg6, but not by overexpression of double cleavage site-deleted form of BmAtg6.

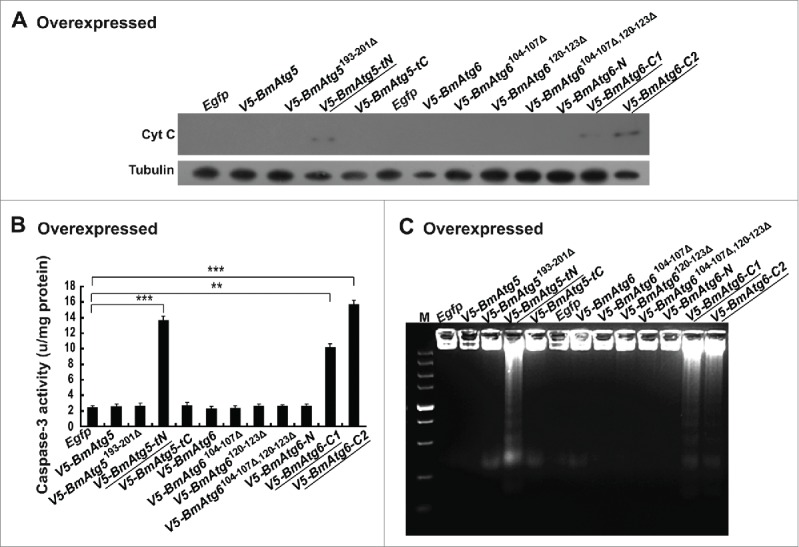

BmATG5-tN and BmATG6-C trigger apoptosis and promote apoptosis induced by 20E or starvation

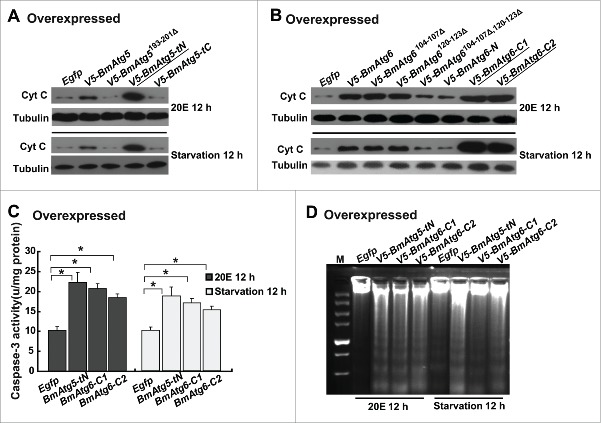

To elucidate the possible function of cleaved BmATG5 and BmATG6 in switching autophagy to apoptosis, the cleaved fragments V5-BmATG5-tN (25 kDa), V5-BmATG5-tC (8 kDa), V5-BmATG6-C1 (36 kDa), V5-BmATG6-C2 (38 kDa) and V5-BmATG6-N (15 kDa) as well as the cleavage site-deleted forms of BmATG5 and BmATG6 were obtained by transient overexpression in Bm-12 cells (Fig. S8). Markedly, only V5-BmAtg5-tN, V5-BmAtg6-C1 or V5-BmAtg6-C2 overexpression was sufficient to induce the release of Cyt C from the mitochondria to the cytosol in the absence of 20E treatment or starvation (Fig. 9A). The activity of the key apoptotic protein Caspase-3 was dramatically upregulated by V5-BmAtg5-tN, V5-BmAtg6-C1 or V5-BmAtg6-C2 overexpression (Fig. 9B). Observation of the DNA ladder confirmed that apoptosis was induced by cleaved fragments of BmATG5 and BmATG6 (Fig. 9C). The results showed that BmATG5-tN and BmATG6-C were sufficient to trigger apoptosis in the absence of stimuli, we then further examined whether the cleaved fragments of BmATG5 and BmATG6 promote apoptosis induced by 20E or starvation.

Figure 9.

The cleaved BmATG5 and BmATG6 are sufficient to induce apoptosis in Bm-12 cells. Egfp, V5-BmAtg5, V5-BmAtg5193–201Δ, V5-BmAtg5-tN, V5-BmAtg5-tC, BmAtg6, V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ, V5-BmAtg6120–123Δ, V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ,120–123Δ, V5-BmAtg6-N, V5-BmAtg6-C1, and V5-BmAtg6-C2 were, respectively, overexpressed in Bm-12 cells for 48 h. The cells were collected for the detection of apoptotic features in the absence of stimuli. (A) Cyt C release was detected in V5-BmAtg5-tN-, V5-BmAtg6-C1- and V5-BmAtg6-C2-overexpressing cells. (B) Activation of Caspase-3 activity was detected in V5-BmAtg5-tN-, V5-BmAtg6-C1- and V5-BmAtg6-C2-overexpressing cells. (C) DNA fragmentation was induced by V5-BmAtg5-tN, V5-BmAtg6-C1 and V5-BmAtg6-C2 overexpression. M, marker.

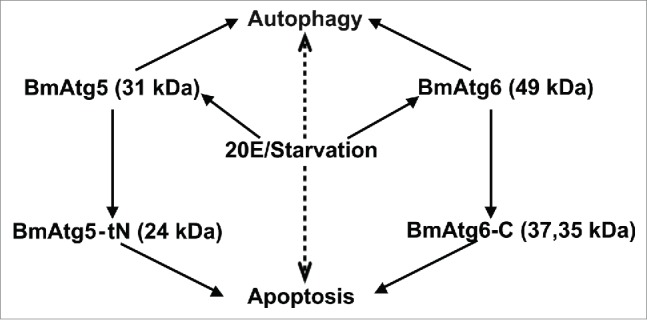

After overexpression of the full-length forms in addition to the cleaved fragments and the cleavage site-deleted forms of BmAtg5 and BmAtg6, the cells were further treated with 20E or starvation for 12 h. The Cyt C release into the cytosol was nearly 2-fold increased in full-length BmAtg5-overexpressing cells compared with the Egfp-overexpressing control cells, while overexpression of the cleavage site-deleted form of BmAtg5 (V5-BmAtg5193–201Δ) led to no changes in Cyt C release (Fig. 10A). Importantly, overexpression of V5-BmAtg5-tN caused much more release of Cyt C than any other forms, whereas overexpression of V5-BmAtg5-tC caused no change in Cyt C release (Fig. 10A). Meanwhile, overexpression of full-length or single cleavage site-deleted forms of BmAtg6 (V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ and V5-BmAtg6120–123Δ) increased Cyt C to the same level in the cytosol after treatment with 20E or starvation. By contrast, overexpression of the double cleavage site-deleted BmAtg6 (V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ,120–123Δ) impaired the ability to stimulate Cyt C release (Fig. 10B). Furthermore, overexpression of either V5-BmAtg6-C1 or V5-BmAtg6-C2 induced more release of Cyt C than any other forms, while overexpression of V5-BmAtg6-N caused no change in Cyt C release (Fig. 10B). Notably, the Caspase-3 activity and DNA ladder detection revealed that both 20E and starvation induced higher caspase activity and more DNA fragmentation in V5-BmAtg5-tN-, V5-BmAtg6-C1- or V5-BmAtg6-C2-overexpressing cells (Fig. 10C and 10D). These composite results demonstrated that BmATG5-tN and BmATG6-C trigger apoptosis and promote induced apoptosis in Bm-12 cells (Fig. 11).

Figure 10.

Cleaved BmATG5 and BmATG6 promote apoptosis induced by 20E or starvation. Egfp, V5-BmAtg5, V5-BmAtg5193–201Δ, V5-BmAtg5-tN, V5-BmAtg5t-C, V5-BmAtg6, V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ, V5-BmAtg6120–123Δ, V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ,120–123Δ, V5-BmAtg6-N, V5-BmAtg6-C1, and V5-BmAtg6-C2 were, respectively, overexpressed in Bm-12 cells for 48 h. Subsequently, the cells were treated with 20E or starved for 12 h and collected for the detection of apoptotic features. (A) Promotion of Cyt C release by overexpression of full-length BmAtg5 or V5-BmAtg5-tN in Bm-12 cells. (B) Promotion of Cyt C release by overexpression of full-length BmAtg6, V5-BmAtg6-C1, or V5-BmAtg6-C2 in Bm-12 cells. (C) Upregulation of Caspase-3 activity by overexpression of V5-BmAtg5-tN, V5-BmAtg6-C1 or V5-BmAtg6-C2 in Bm-12 cells. (D) Increase of DNA fragmentation by overexpression of V5-BmAtg5-tN, V5-BmAtg6-C1 and V5-BmAtg6-C2 in Bm-12 cells.

Figure 11.

A model for 20E and starvation signals to induce autophagy and apoptosis in Bombyx. Treatments with 20E or starvation (middle: the upstream stimuli) activate BmATG5 and BmATG6 to facilitate autophagy and mediate the autophagy-induced apoptosis. See the details in the text.

Discussion

Autophagy precedes apoptosis in Bm-12 cells after 20E treatment or starvation

As introduced above, 20E and starvation are the 2 common stimuli of autophagy and apoptosis in insects. In Bombyx, 20E slowly reduces food consumption and then induces starvation-like conditions during molting and pupation, providing a correlation between 20E and starvation in the induction of both autophagy and apoptosis.31 In a previous study, we have found that autophagy precedes apoptosis in the midgut during Bombyx metamorphosis, but the core mechanism is not illustrated.40 Here, we found that starvation and 20E addition caused significant cell death after 4 to 16 h treatment, with autophagy proceeding apoptosis at least by 3 h in Bombyx Bm-12 cells (Figs. 1 to 4), which was similar to the observation in midgut during metamorphosis.40 In 2 other lepidopteran insect cell lines, glucose starvation in Sl-1 cells (from Spodoptera litura) and amino acid starvation in SL-ZSU-1cells (S. litura) induces autophagy preceding apoptosis at least by 48 h.41,42 In this work, we used PBS starvation and 20E treatment to mimic the conditions during larval-pupal transition, when the animals are severely starved and the 20E titer is extremely high.31,43 Together, in certain circumstances, it is a common feature that autophagy precedes apoptosis induced by the common stimuli such as 20E or starvation.

In general, the stimulatory effects on autophagy and apoptosis by starvation are stronger and faster than those by 20E (Figs. 2 to 4). Starvation is a destructive stress condition causing eventual cell death. Starvation triggers autophagy by regulating the PI3K-AMPK-TORC1 interactions, and thus phosphorylation of the ATG1-ATG13 complex.4,9 Meanwhile, starvation leads to mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and the release of mitochondrial Cyt C into cytosol, which results in the activation of initiator caspases and effector caspases.6 In cell lines or cultured tissues, 20E upregulates many apoptosis genes23,27,29 and most Atg genes.27,28 In addition, 20E blocks the PI3K-TORC1 pathway to initiate autophagy.27,30 Here we show that 20E causes Cyt C release and Caspase-3 activation, leading to apoptosis (Figs. 3, 4, 9, 10). In addition, a long period of starvation caused degradation of ATG8 in S1-HP cells under amino acid starvation (S. litura),44 it appears the same case in Bm-12 cells at 16 h after starvation consistent with the change of LysoTracker Red staining.

In vivo, 20E induces starvation-like condition in a complex manner;31,43,45 in turn, starvation induces autophagy and apoptosis. These phenomena could explain why both 20E and starvation causes massive cell death in the larval midgut during Bombyx metamorphosis, with autophagy preceding apoptosis.31,40 However, it is currently unclear whether 20E induces starvation-like conditions in cultured cells. Our preliminary experiments suggest that 20E might inhibit the PI3K-AMPK-TORC1 interactions to initiate autophagosome formation in cultured cells, but the underlying molecular mechanism requires further investigation.

Crucial roles of BmATG5 and BmATG6 in switching autophagy to apoptosis

In mammals, ATG5 and BECN1 were confirmed to be the molecular switches to trigger apoptosis during autophagy in response to stress condition, the full-length ATG5 and BECN1 are required for autophagosome formation, whereas the cleaved forms ATG5t and BECN1-C induce the release of Cyt C and trigger apoptosis.14,17 To date, a number of Atg5 and Atg6 genes have been identified in insects,28,46,47 but it has never been understood whether they play a role in regulating apoptosis in insects. In Bombyx, BmAtg5, BmAtg6 as well as BmAtg4-like have been cloned, BmAtg5, BmAtg6 but not BmAtg4-like are significantly upregulated by 20E;28 thus, the functions of BmAtg5 and BmAtg6 in autophagy-mediated apoptosis were studied here.

In response to 20E or starvation, the conjugation of BmATG8–PE was rapidly induced within 1 h (Fig. 4); a couple of hours later, BmATG5 and BmATG6 were cleaved into BmATG5-tN and BmATG6-C, respectively (Fig. 5). RNAi of BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 decreased both autophagy and apoptosis after 20E treatment or starvation. Meanwhile, overexpression of BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 induced autophagy but not apoptosis in the absence of the stimuli, but promoted both autophagy and apoptosis induced by 20E or starvation (Fig. 7 and 8). Notably, overexpression of cleavage site-deleted BmAtg5 or BmAtg6 increased autophagy but not apoptosis induced by 20E or starvation; however, overexpression of BmAtg5-tN or BmAtg6-C was able to directly trigger apoptosis or promote the induced apoptosis (Figs. 9 and 10). In conclusion, being cleaved into BmATG5-tN and BmATG6-C, BmATG5 and BmATG6 mediate apoptosis following autophagy induced by 20E or starvation in Bombyx Bm-12 cells. These composite pathways regulated by 20E and starvation orchestrate the programmed cell death in Bombyx larval organs during Bombyx metamorphosis (Fig. 11). For the first time, we demonstrate the crucial roles of BmATG5 and BmATG6 in switching autophagy to apoptosis in insects, revealing a functional conservation from insects to mammals.

In mammals, the balance between autophagy and apoptosis is mediated by the BCL2 family proteins.48 ATG5 and BECN1 are cleaved into active ATG5 (ATG5t) and BECN1-C by CAPN/calpain and CASP3, respectively. Subsequently, ATG5t and BECN1-C are transferred to mitochondria, cause mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, release CYCS from mitochondria to the cytosol, and trigger apoptosis. While ATG5t is confirmed to bind to the antiapoptotic protein BCL2L1/Bcl-2-XL to activate BAX and stimulate the release of CYCS, the BCL2-BECN1 complex regulates both apoptosis and autophagy by controlling of the threshold between cell survival and cell death in mammalian cells,48 but the activation of BECN1-C is not emphasized.14,18 Some BCL2 family members increase the activity of caspases, thus inactivating autophagy by the decrease of ATG5 and BECN1 protein abundance, which in turn negatively regulates autophagy.49,50 Unfortunately, it is ambiguous how the Debcl/Bcl-2 family is involved in the regulation of autophagy and apoptosis in Drosophila.22 Since we have demonstrated that BmATG5 and BmATG6 mediate apoptosis following autophagy induced by 20E or starvation, it brings forth Bombyx as a model insect system to study whether and how the BCL2 family interacts with BmATG5 and BmATG6 in switching autophagy to apoptosis in response to the common stimuli such as 20E and starvation.

It is largely acknowledged that autophagy is a cell survival signal in mammals, as should be the same in insects when the stress conditions are not severe. In our experimental conditions, a high dose of 20E and a complete starvation were used. It is likely that the extensive autophagy boosts together with apoptosis to accelerate the irreversible cell death, reflecting the extensive cell death of midgut larval cells during Bombyx metamorphosis.40 To test this hypothesis in Bm-12 cells, it will be necessary to overexpress BmAtg1 (and probably together with BmAtg13) to cause sufficient autophagy.56 If autophagy indeed results in apoptosis,51 one might investigate how BmATG5 and BmATG6 are cleaved to BmATG5-tN and BmATG6-C1/C2 for switching autophagy to apoptosis and how the BCL2 family is involved in this process.

Materials and methods

Cells

DZNU-Bm-12 cells (abbreviated as Bm-12, kindly provided by Professor Chuanxi Zhang at Zhejiang University) were maintained in TNM-FH medium (Hyclone, AXL50928) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, SV30087.01) at 27°C.28

Bioinformatics analysis of BmATG5 and BmATG6

The amino acid sequences of Bombyx BmATG5 (NM_001142487.1) and BmATG6 (NM_001142490.1) were found in GenBank, and the homology analysis was performed between Homo sapiens, Bombyx, Drosophila, Mus musculus, and Caenorhabditis elegans using ClustalW software. The calpain and Caspase-3 cleavage sites in BmATG5 and BmATG6 were analyzed and predicted using DNAMAN software.

BmATG5 and BmATG6 cleavage assay

The vectors pET21d-BmAtg5 and pET21d-BmAtg6 were constructed and transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 competent cells for prokaryotic expression. The recombinant His-tagged BmATG5 (31 kDa) and BmATG6 (49 kDa) proteins were expressed and purified using Ni-NTA columns (QIAGEN, 30210), then separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and extracted.

The recombinant BmATG5 and BmATG6 were incubated with µ-Calpain (Merck, 208713) or Caspase-3 (Enzo, ALX-201-059), respectively, in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). µ-Calpain (10 µg) was incubated with 100 µg recombinant BmATG5 proteins at 25°C for 1 h, and 10 U of Caspase-3 was incubated with 100 µg BmATG6 at 37°C overnight. The reaction was stopped by adding loading buffer plus 1 mM DTT. The samples were heated at 90°C for 5 min, subsequently separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 (Beyotime Co. Ltd., P0017) to analyze the cleavage of BmATG5 and BmATG6 by µ-Calpain and Caspase-3, respectively.

Antibody generation

A total of 1.0 mg purified recombinant BmATG5 or BmATG6 protein was injected into the abdomen of New Zealand white rabbits for immunization. Four injections were performed at 3-wk intervals. Afterwards, the antiserum was collected for affinity purification, and measured for the antibody titer by ELISA (Zini Biological Science and Technology Co. Ltd, China). The antibody against BmATG8 was generated previously and successful to detect both BmATG8 and BmATG8–PE forms.40

Fluorescent protein subcellular localization

Microscope coverslips (Fisher Scientific, 12-542A) was sterilized before use and placed into 6-well plates during Bm-12 cell plating. After 1 d of preincubation, the cells were transiently cotransfected with pIEX-4-Egfp-BmAtg8 and pIEX-4-mcherry-BmAtg5 or pIEX-4-mcherry-BmAtg6 for 48 h, followed by treatment with 20E or starvation for 4 h. Images were captured using an fluorescence microscope (Life Technologies Co. Ltd., AMF-4302 EVOS FL, USA, Bothell) at 40× magnification.

Trypan blue staining

Bm-12 cells were thoroughly washed with PBS (137 mM NaCl, 10.1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.0) and stained with 0.4% trypan blue (diluted in H2O, Sigma-Aldrich, T6146) for 3 min at 25°C.52 Trypan blue staining was monitored with a fluorescence microscope (Life Technologies Co. Ltd., AMF-4302 EVOS FL, USA, Bothell) at 40× magnification. Three independent experiments were performed; the results of one representative experiment are shown here. The Student t test was used for statistical analysis.

LysoTracker red staining

Bm-12 cells were stained with LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Invitrogen Co. Ltd., L7528) in PBS (pH 7.0) at a final concentration of 50 nM for 10 min at 37°C and washed with PBS 3 times; observations were performed under an LSM510 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Germany, Oberkochen). The ANOVA was used for statistical analysis.

Hoechst staining

Bm-12 cells were stained with 10 μg/mL Hoechst 33258 dye (Beyotime Co. Ltd., C1011) for 5 min at 37°C and washed with PBS 3 times according to the manufacturer's instructions.53 The images of apoptotic bodies were captured by a florescence microscope (Life Technologies Co. Ltd., AMF-4302 EVOS fl, USA) under the same exposure and analyzed using the ANOVA.

ANXA5-FITC and PI staining

Bm-12 cells were plated in 6-well plates with sterilized microscope coverslips at the bottom, and preincubated for 1 d. After treatment with 20E or starvation, the cells in the medium were collected by centrifugation and sucked back into the well, thus stained together with the cells adhered to the microscope cover glasses in site by ANXA5-FITC and PI (KeyGEN, KGA107) according to the manufacturer's instructions.54 The ANXA5-FITC and PI staining was monitored under a FV10-ASW confocal microscope (Olympus, Japan, Tokyo). The normal cells (ANXA5− and PI−), early apoptotic cells (ANXA5+ and PI−), late apoptotic cells (ANXA5+ and PI+), and dead cells (ANXA5− and PI+) were detected and counted. The ANOVA was used for statistical analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR and western blotting

For quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis, total RNA was extracted from Bm-12 cells using a qPCR machine (Bio-Rad, CFX96, USA) with a fluorescent dye (Bio-Rad, 172-5201AP). rp49 was used as a reference gene.28

Protein concentration in each sample was measured and adjusted to the same amount of total protein for western blotting according to the standard procedure.28 The primary antibodies were directed against the following proteins: BmATG5 (1:500), BmATG6 (1:500), BmATG8 (1:1000), CYCS/Cyt C (1:1000; BD, 556433), or EGFP (1:1000; Abmart Co. Ltd., 214574), monoclonal antibodies against the V5 tag (1:1000; TransGen Biotech Co. Ltd., HT401-01) and tubulin (1:10,000; Beyotime, AT819) were used in this study. The western blotting images were captured by a Tanon-5500 Chemiluminescent Imaging System (Tanon, China, Shanghai)/KODAK Medical X-Ray Processor 102 (Carestream Health, Inc., USA). Quantitative measurements of western blots were performed using ImageJ software; 3 independent biological replicates were performed and analyzed using ANOVA.

Analysis of Cyt C release from the mitochondria

Bm-12 cells were collected, and the mitochondria were freshly isolated using the mitochondria isolation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Beyotime Co. Ltd., C3601). The content of Cyt C in the mitochondria and cytosol was further analyzed by immunoblotting with a Cyt C antibody (1:1000; BD Co. Ltd., 556433).

DNA ladder detection

Bm-12 cells were collected by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 5 min at 4°C and resuspended in 20 μL of buffer (20 mM EDTA, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.8% SDS (Beyotime Co. Ltd., C0007-1). The cells were subsequently incubated with 10 μL of 10 mg/mL RNase A (TIANGEN, M1105) at 37°C for 1 h. Then, 10 μL of 20 mg/mL protease K (TIANGEN, K0012) was added to the reaction for further incubation overnight at 55°C. The following DNA extraction steps were performed according to the method used in silkworm midguts.40 Finally, 10 µg of genomic DNA was detected on a 2.5% agarose gel and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide.

Caspase-3 activity assay

Caspase-3 activity was detected using a CASP3/Caspase-3 activity kit (Beyotime Co. Ltd., C1116). Bm-12 cells were collected and washed with PBS buffer, total protein was extracted using 100 μl of lysis buffer and quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime Co. Ltd., CCK-8). The protein concentration in each sample was adjusted to 3 μg/μl. The Caspase-3 activity assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. All reactions were incubated at 37°C for 2 h away from light, and then measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Model680, USA, Hercules) at an absorbance of 405 nm. Caspase-3 activity was normalized relative to the total protein content of the sample. Three independent experiments were performed and analyzed using the Student t test.

Starvation

The medium of Bm-12 cells was removed and replaced with filtered PBS buffer (137 mM NaCl, 10.1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4) for the starvation treatment. After starved for 4, 8, 12, 16 h, the cells were collected for further analysis; starvation mentioned in this paper was induced by PBS. In our preliminary experiments, IBBS (insect balanced salt solution; 75m MNaCl, 5 mMCaCl2, 55 mM KCl, 2.6 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 2.8 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 4.2 mM NaHCO3, 7.3 mM NaH2PO4·H2O, 10 mM glucose, pH6.8) induced cell death more than PBS; and in all studies in this paper, PBS was used for the starvation experiments.

20E and AD treatment

The Bm-12 cells were treated with 20E (Sigma-Aldrich, H5142) dissolved in ethanol at a final concentration of 1, 2.5, 5, 10, or 20 µM, the control cells were added with the same volume of solvent. After incubation for 4, 8, 12, 16 h, the cells were collected for further analysis. AD (Sigma-Aldrich, 162400) final concentration used was 1µg/mL.

RNAi knockdown

Primers containing the T7 promoter sequence were designed for RNA interference of BmAtg5, BmAtg6 and Egfp. The template was amplified by PCR from the total cDNA of Bm-12 cells. Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) of Bombyx BmAtg5, BmAtg6 and Egfp was generated using the T7 RiboMAX™ Express RNAi system (Promega, P1700) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The dsRNA was transfected into Bm-12 cells using Effectene transfection reagent (QIAGEN, 301425) at a final concentration of 100 μg/ mL.28 After incubation for 48 h, the cells were further treated with 10 μM 20E or starvation in PBS. All the primers used in this study are listed in Table S1.

Transient overexpression

The various versions of BmAtg5 and BmAtg6, including the full-length, cleavage sites deletion and the cleaved fragments fused with the V5 tag at the N-terminal were amplified by PCR using total cDNA of Bm-12 cells as template. Finally, the sequences were inserted into the pIEX4 vector (pIEX4-BmAtg5, pIEX4-mcherry-BmAtg5, pIEX4-BmAtg6, pIEX4-mcherry-BmAtg6, pIEX4-Egfp-BmAtg8, pIEX4-V5-BmAtg5193–201Δ, pIEX4-V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ, pIEX4-V5-BmAtg6120–123Δ, pIEX4-V5-BmAtg6104–107Δ,120–123Δ, pIEX4-V5-BmAtg5-tN, pIEX4-V5-BmAtg5-tC, pIEX4-V5-BmAtg6-C1, pIEX4-V5-BmAtg6-C2 and pIEX4-V5-BmAtg6-N). Egfp fused with Atg8 and mCherry fused with Atg5 or Atg6 were respectively inserted into the pIEX4 vector. The constructed plasmids were transfected into Bm-12 cells using Effectene transfection reagent (QIAGEN, 301425), according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 48 h, the cells were further treated with 20E or starvation, or collected for various assays.28

TEM analysis

The Bm-12 cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 24 h at 4°C, which were subsequently pretreated with the standard procedure of TEM and viewed on a H7650 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan, Tokoyo) to observe autolysosomes and autophagosomes.28 The Student t test was used for statistical analysis.

Statistics

The experimental data were analyzed with the Student t test and ANOVA test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. ANOVA: the bars labeled with different lowercase letters are significantly different (P < 0.05). Throughout the study, the values are represented as the mean ± standard deviation of 3 independent experiments.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- 20E

20-hydroxyecdysone

- AD

actinomycin D

- BmATG5-tN and BmATG6-C

cleaved forms of BmATG5 and BmATG6

- BmATG8–PE

the cleaved ATG8 conjugated with the lipid phosphatidylethanolamine

- Cyt C

lepidopteran cytochrome C

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PIK3C3

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, catalytic subunit type 3

- PtdIns3K

the class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PI

propidium iodide

- qPCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Nature Publishing Group for English editing. We also thank Dr. Yadong Huang (Biopharmaceutical Research and Development Center, Jinan University, China), Dr. Qili Feng (School of Life Sciences, South China Normal University, China) and Dr. Xiaoqiang Yu (Division of Cell Biology and Biophysics, School of Biological Sciences, University of Missouri-Kansas City, USA) for technical support and suggestions related to this work. We also appreciate Mr. Xiaoyan Gao, Mr. Xiaoshu Gao, Ms. Jiqin Li and Mr. Zhiping Zhang (Core Facility of Plant Physiology and Ecology Institute) for technique supports.

Funding

This study was supported, in whole or in part, by the “973” National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB114600 to Y.C., W.Y., S.L. and Q.X.), the Natural Science Foundation of China (31101765 to W.Y., 31472042 to L.T.), fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-22-ZJ0205 to J.L.), basic research program project of Yunnan provincial science and technology hall (2010ZC151 and 2010CD088 to K.X.), Ph.D specific research project of Honghe University (XJ15B13 to K.X.).

References

- 1.Kourtis N, Tavernarakis N. Autophagy and cell death in model organisms. Cell Death Differ 2009; 16(1):21-30; PMID:19079286; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2008.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, Agholme L, Agnello M, Agostinis P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, et al.. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 2012; 8:445-544; PMID:22966490; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.19496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green DR. Apoptotic pathways: ten minutes to dead. Cell 2005; 121:671-4; PMID:15935754; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin M, Klionsky DJ. The core molecular machinery of autophagosome formation. Autophagy and Cancer 2013; 8:25-45; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-4614-6561-4_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boya P, Reggiori F, Codogno P. Emerging regulation and functions of autophagy. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15(7):713-20; PMID:23817233; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007; 8(9):741-52; PMID:17717517; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shintani T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy in health and disease: a double-edged sword. Science 2004; 306(5698):990-5; PMID:15528435; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1099993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryoo HD, Baehrecke EH. Distinct death mechanisms in Drosophila development. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2010; 22(6):889-95; PMID:20846841; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death Differ 2005; 12:1542-52; PMID:16247502; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wirawan E, Vanden BT, Lippens S, Agostinis P, Vandenabeele P. Autophagy: for better or for worse. Cell Res 2012; 22(1):43-61; PMID:21912435http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cr.2011.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell RC, Tian Y, Yuan H, Park HW, Chang Y, Kim J, Kim H, Neufeld TP, Dillin A, Guan K. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15(7):741-50; PMID:23685627; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betin VM, Lane JD. Caspase cleavage of Atg4D stimulates GABARAP-L1 processing and triggers mitochondrial targeting and apoptosis. J Cell Sci 2009; 122(14):2554-66; PMID:19549685; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.046250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Codogno P, Meijer AJ. Atg5: more than an autophagy factor. Nat Cell Biol 2006; 8(10):1045-7; PMID:17013414; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1006-1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yousefi S, Perozzo R, Schmid I, Ziemiecki A, Schaffner T, Scapozza L, Brunner T, Simon H. Calpain-mediated cleavage of Atg5 switches autophagy to apoptosis. Nature Cell Biol 2006; 8(10):1124-32; PMID:16998475; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maiuri MC, Criollo A, Kroemer G. Crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy within the Beclin 1 interactome. EMBO J 2010; 29(3):515-6; PMID:20125189; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2009.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wirawan E, Walle LV, Kersse K, Cornelis S, Claerhout S, Vanoverberghe I, Roelandt R, De Rycke R, Verspurten J, Declercq W. Caspase-mediated cleavage of Beclin-1 inactivates Beclin-1-induced autophagy and enhances apoptosis by promoting the release of proapoptotic factors from mitochondria. Cell Death Dis 2010; 1(1):e18; PMID:21364619; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cddis.2009.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yousefi S, Simon H. Apoptosis regulation by autophagy gene 5. Crit Rev Oncol/Hemat 2007; 63(3):241-4; PMID:17644402; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Tang D. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 2011; 18(4):571-80; PMID:21311563; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2010.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varkey J, Chen P, Jemmerson R, Abrams JM. Altered cytochrome c display precedes apoptotic cell death in Drosophila. J Cell Biol 1999; 144(4):701-10; PMID:10037791; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.144.4.701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorstyn L, Mills K, Lazebnik Y, Kumar S. The two cytochrome c species, DC3 and DC4, are not required for caspase activation and apoptosis in Drosophila cells. J Cell Biol 2004; 167(3):405-10; PMID:15533997; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200408054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmermann KC, Ricci JE, Droin NM, Green DR. The role of ARK in stress-induced apoptosis in Drosophila cells. J Cell Biol 2002; 156(6):1077-87; PMID:11901172; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.20112068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hay BA, Guo M. Caspase-dependent cell death in Drosophila. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2006; 22: 623-50; PMID:16842034; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012804.093845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clem RJ, Miller LK. Control of programmed cell death by the baculovirus genes p35 and iap. Mol Cell Biol 1994; 14(8):5212-22; PMID:8035800; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.14.8.5212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin C, Wu S, Lu X, Liu Q, Zhang L, Yang J, Xi Q, Cai Y. Conditioned medium from actinomycin D-treated apoptotic cells induces mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in bystander cells. Toxicol Lett 2012; 211(1):45-53; PMID:22421271; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahdev S, Taneja TK, Mohan M, Sah NK, Khar AK, Hasnain SE, Athar M. Baculoviral p35 inhibits oxidant-induced activation of mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003; 307(3):483-90; PMID:12893247; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01224-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumarswamy R, Seth RK, Dwarakanath BS, Chandna S. Mitochondrial regulation of insect cell apoptosis: evidence for permeability transition pore-independent cytochrome-c release in the Lepidopteran Sf9 cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2009; 41(6):1430-40; PMID:19146980; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin VP, Thummel CS. Mechanisms of steroid-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2005; 16(2):237-43; PMID:15797834; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tian L, Ma L, Guo E, Deng X, Ma S, Xia Q, Cao Y, Li S. Twenty-hydroxyecdysone upregulates Atg genes to induce autophagy in the Bombyx fat body. Autophagy 2013; 9(8):1172-87; PMID:23674061; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.24731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian L, Liu S, Liu H, Li S. Twenty-hydroxyecdysone upregulates apoptotic genes and induces apoptosis in the Bombyx fat body. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 2012; 79:207-19; PMID:22517444; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/arch.20457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delanoue R, Slaidina M, Léopold P. The steroid hormone ecdysone controls systemic growth by repressing dMyc function in Drosophila fat cells. Dev Cell 2010; 18:1012-21; PMID:20627082; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang S, Liu S, Liu H, Wang J, Zhou S, Jiang RJ, Bendena WG, Li S. Twenty-hydroxyecdysone reduces insect food consumption resulting in fat body lipolysis during molting and pupation. J Mol Cell Biol 2010; 2(3):128-38; PMID:20430856; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jmcb/mjq006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berry DL, Baehrecke EH. Growth arrest and autophagy are required for salivary gland cell degradation in Drosophila. Cell 2007; 131:1137-48; PMID:18083103; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott RC, Schuldiner O, Neufeld TP. Role and Regulation of Starvation-Induced Autophagy in the Drosophila Fat Body. Dev Cell 2004; 7(2):167-78; PMID:15296714; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Denton D, Shravage B, Simin R, Mills K, Berry DL, Baehrecke EH, Kumar S. Autophagy, not apoptosis, is essential for midgut cell death in Drosophila. Curr Biol 2009; 19:1741-6; PMID:19818615; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Jia Q, Tettamanti G, Li S. Balancing crosstalk between 20-hydroxyecdysone-induced autophagy and caspase activity in the fat body during Drosophila larval-prepupal transition. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 2013; 43(11):1068-78; PMID:24036278; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H, Wang J, Li S. E93 predominantly transduces 20-hydroxyecdysone signaling to induce autophagy and caspase activity in Drosophila fat body. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 2014; 45:30-9; PMID:20430856; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sekimoto T, Iwami M, Sakurai S. Coordinate responses of transcription factors to ecdysone during programmed cell death in the anterior silk gland of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Mol Biol 2006; 15(3):281-92; PMID:16756547; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00641.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li QR, Deng XJ, Yang WY, Huang ZJ, Tettamanti G, Cao Y, Feng QL. Autophagy, apoptosis, and ecdysis-related gene expression in the silk gland of the silkworm (Bombyx mori) during metamorphosis. Cana J Zool 2010; 88(12):1169-78. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1139/Z10-083; [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sumithra P, Britto CP, Krishnan M. Modes of cell death in the pupal perivisceral fat body tissue of the silkworm Bombyx mori L. Cell Tissue Res 2010; 339(2):349-58; PMID:19949813; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00441-009-0898-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franzetti E, Huang Z, Shi Y, Xie K, Deng X, Li J, Li Q, Yang W, Zeng W, Casartelli M. Autophagy precedes apoptosis during the remodeling of silkworm larval midgut. Apoptosis 2012; 17(3):305-24; PMID:22127643; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10495-011-0675-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu KY, Tang QH, Fu C, Peng J, Yang H, Li Y, Hong H. Influence of glucose starvation on the pathway of death in insect cell line Sl: apoptosis follows autophagy. Cytotechnology 2007; 54(2):97-105; PMID:19003024; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10616-007-9080-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu W, Wei W, Ablimit M, Ma Y, Fu T, Liu K, Peng J, Li Y, Hong H. Responses of two insect cell lines to starvation: Autophagy prevents them from undergoing apoptosis and necrosis, respectively. J Insect Physiol 2011; 57(6):723-34; PMID:21335011; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian L, Guo E, Wang S, Liu S, Jiang RJ, Cao Y, Ling E, Li S. Developmental regulation of glycolysis by 20-hydroxyecdysone and juvenile hormone in fat body tissues of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J Mol Cell Biol 2010; 2(5):255-63; PMID:20729248; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jmcb/mjq020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gai Z, Zhang X, Islam M, Wang X, Li A, Yang Y, Li Y, Peng J, Hong H, Liu K. Characterization of Atg8 in lepidopteran insect cells. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 2013; 84(2):57-77; PMID:23959953; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/arch.21114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hossain MS, Liu Y, Zhou S, Li K, Tian L, Li S. Twenty-Hydroxyecdysone-induced transcriptional activity of FoxO upregulates brummer and acid lipase-1 and promotes lipolysis in Bombyx fat body. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 2013; 43(9):829-38; PMID:23811219; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X, Hu Z, Li W, Li Q, Deng X, Yang W, Cao Y, Zhou C. Systematic cloning and analysis of autophagy-related genes from the silkworm Bombyx mori. BMC Mol Boil 2009; 10(50):1-9; PMID:19470186; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2199-10-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee CY, Clough EA, Yellon P, Teslovich TM. Genome-wide analyses of steroid-and radiation-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Curr Biol 2003; 13:350-7; PMID:12593803; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00085-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo S, Rubinsztein DC. Apoptosis blocks Beclin 1-dependent autophagosome synthesis: an effect rescued by Bcl-xL. Cell Death Differ 2010; 17(2):268-77; PMID:19713971; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2009.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu H, Che X, Zheng Q, Wu A, Pan K, Shao A, Wu Q, Zhang J, Hong Y. Caspases: a molecular switch node in the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Int J Biol Sci 2014; 10(9):1072-83; PMID:25285039; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7150/ijbs.9719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cho DH, Jo YK, Hwang JJ, Lee YM, Roh SA, Kim JC. Caspase-mediated cleavage of ATG6/Beclin-1 links apoptosis to autophagy in HeLa cells. Cancer Lett 2009; 274(1):95-100; PMID:18842334; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott RC, Juhász G, Neufeld TP. Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr Biol 2007; 17(1): 1-11; PMID:17208179; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Y, Azad MB, Gibson SB. Methods for detecting autophagy and determining autophagy-induced cell death. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2010; 88(3):285-95; PMID:20393593; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1139/Y10-010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wei W, Gai Z, Ai H, Wu W, Yang Y, Peng J, Hong H, Li Y, Liu K. Baculovirus infection triggers a shift from amino acid starvation-induced autophagy to apoptosis. PLoS One 2012; 7(5):e37457; PMID:22629397; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0037457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen WJ, Huang CG, Fan-Chiang MH, Liu YH, Lee YF. Apoptosis of Ascogregarina taiwanensis (Apicomplexa: Lecudinidae), which failed to migrate within its natural host. J Exp Biol 2013; 216(2):230-135; PMID:22996442; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jeb.072918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.