Abstract

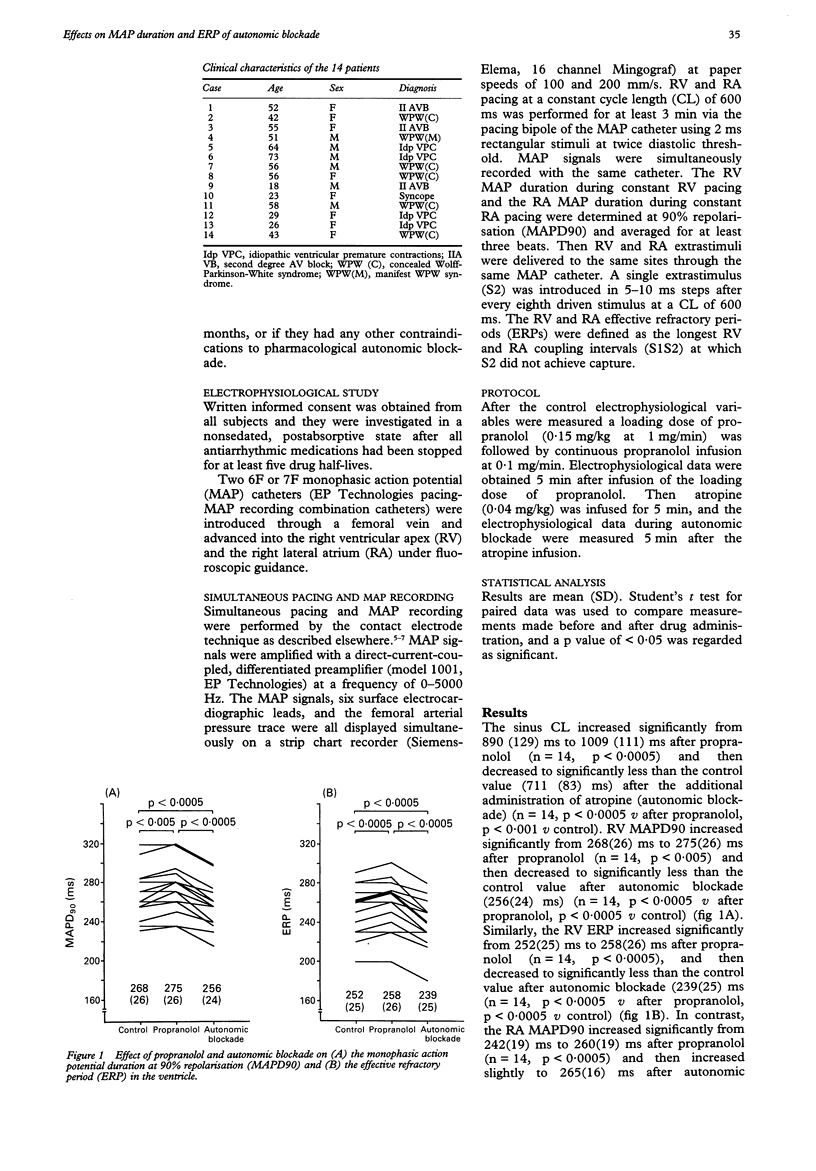

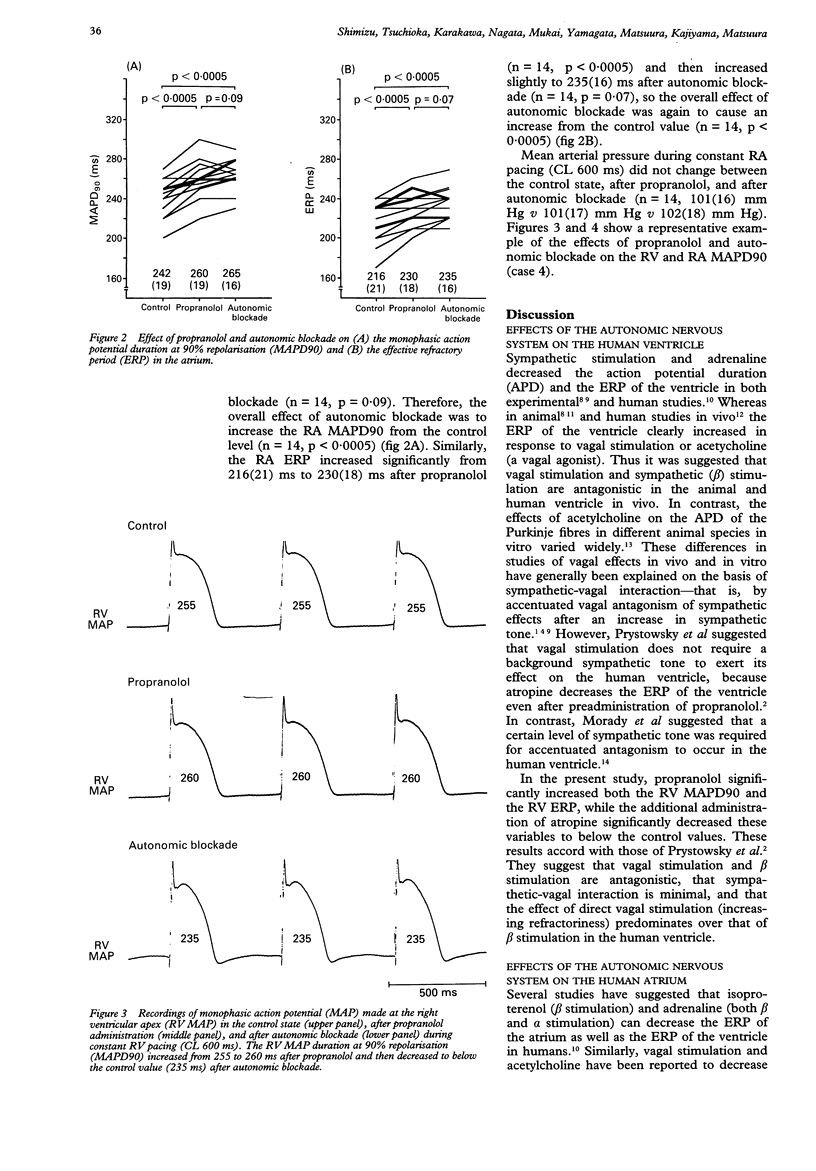

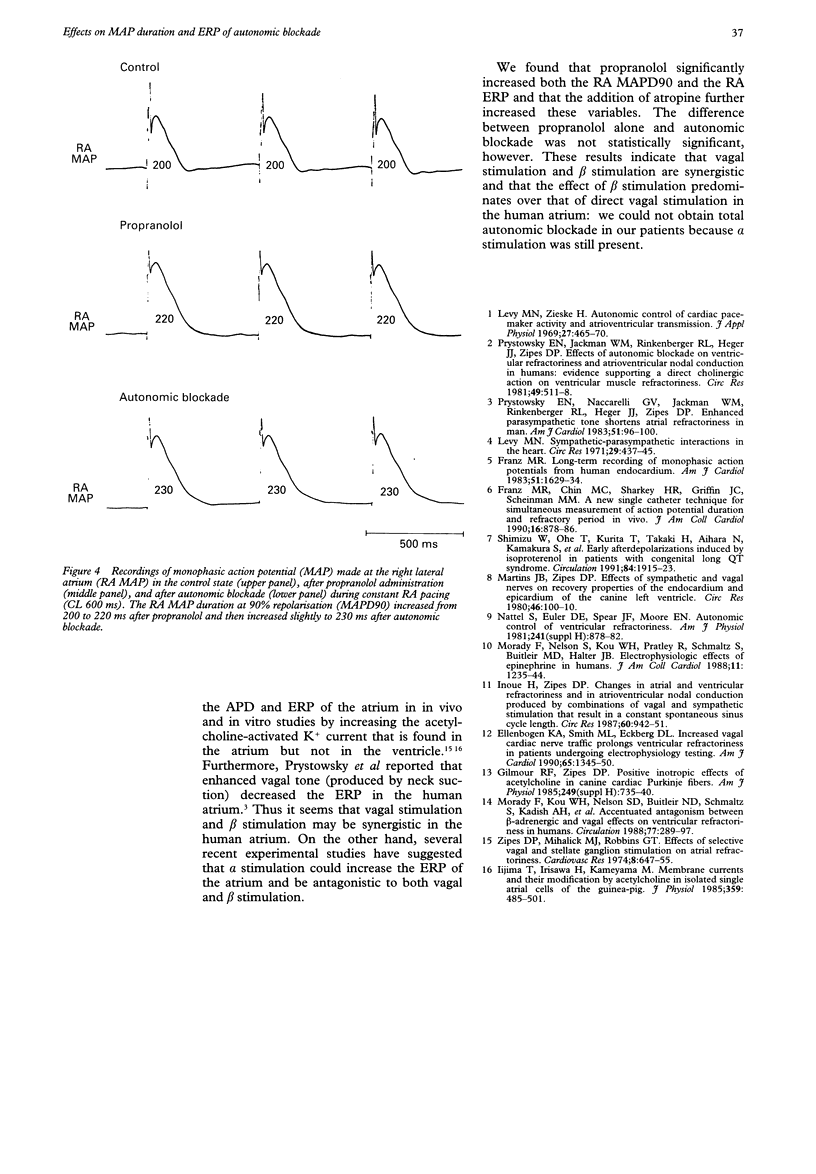

OBJECTIVE--This study investigated the dominance of each limb of the autonomic nervous system and tested sympathetic-vagal interactions in the human ventricle and atrium after administration of propranolol and atropine. PATIENTS AND METHODS--The 90% monophasic action potential duration (MAPD90) and the effective refractory period (ERP) at the right ventricular apex (RV) and the right lateral atrium (RA) were measured in 14 patients. The MAPD90 was measured during constant RV and RA pacing (cycle length 600 ms) and the ERP was measured at a driven cycle length of 600 ms. Electrophysiological variables were measured during a control period, after propranolol (0.15 mg/kg loading dose followed by 0.1 mg/min infusion), and after autonomic blockade (atropine 0.04 mg/kg). RESULTS--Both RV MAPD90 and RV ERP increased after propranolol (RV MAPD90 from 268 (26) ms to 275 (26) ms, p < 0.005; RV ERP from 252 (25) ms to 258 (26) ms, p < 0.0005) and then decreased to below the control values after autonomic blockade (RV MAPD90 256 (24) ms; RV ERP 239 (25) ms, p < 0.0005 v propranolol, p < 0.0005 v control). In contrast, both RA MAPD90 and RA ERP increased after propranolol (RA MAPD90 from 242 (19) ms to 260 (19) ms; RA ERP from 216 (21) ms to 230 (18) ms, p < 0.0005), and then increased slightly more after autonomic blockade (RA MAPD90 265 (16) ms, p = 0.09; RA ERP 235 (16) ms, p = 0.07), thus remaining above control values (p < 0.0005). CONCLUSIONS--The results indicate (a) that in the human ventricle vagal stimulation and sympathetic beta stimulation are antagonistic and that direct vagal stimulation predominates over beta stimulation, with sympathetic-vagal interaction being minimal and (b) that in the human atrium vagal stimulation and beta stimulation are synergistic and beta stimulation predominates over vagal stimulation, with direct vagal stimulation having a minimal effect.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ellenbogen K. A., Smith M. L., Eckberg D. L. Increased vagal cardiac nerve traffic prolongs ventricular refractoriness in patients undergoing electrophysiology testing. Am J Cardiol. 1990 Jun 1;65(20):1345–1350. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)91325-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz M. R., Chin M. C., Sharkey H. R., Griffin J. C., Scheinman M. M. A new single catheter technique for simultaneous measurement of action potential duration and refractory period in vivo. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990 Oct;16(4):878–886. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz M. R. Long-term recording of monophasic action potentials from human endocardium. Am J Cardiol. 1983 Jun;51(10):1629–1634. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima T., Irisawa H., Kameyama M. Membrane currents and their modification by acetylcholine in isolated single atrial cells of the guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1985 Feb;359:485–501. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H., Zipes D. P. Changes in atrial and ventricular refractoriness and in atrioventricular nodal conduction produced by combinations of vagal and sympathetic stimulation that result in a constant spontaneous sinus cycle length. Circ Res. 1987 Jun;60(6):942–951. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.6.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy M. N. Sympathetic-parasympathetic interactions in the heart. Circ Res. 1971 Nov;29(5):437–445. doi: 10.1161/01.res.29.5.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy M. N., Zieske H. Autonomic control of cardiac pacemaker activity and atrioventricular transmission. J Appl Physiol. 1969 Oct;27(4):465–470. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1969.27.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins J. B., Zipes D. P. Effects of sympathetic and vagal nerves on recovery properties of the endocardium and epicardium of the canine left ventricle. Circ Res. 1980 Jan;46(1):100–110. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morady F., Kou W. H., Nelson S. D., de Buitleir M., Schmaltz S., Kadish A. H., Toivonen L. K., Kushner J. A. Accentuated antagonism between beta-adrenergic and vagal effects on ventricular refractoriness in humans. Circulation. 1988 Feb;77(2):289–297. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morady F., Nelson S. D., Kou W. H., Pratley R., Schmaltz S., De Buitleir M., Halter J. B. Electrophysiologic effects of epinephrine in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 Jun;11(6):1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prystowsky E. N., Jackman W. M., Rinkenberger R. L., Heger J. J., Zipes D. P. Effect of autonomic blockade on ventricular refractoriness and atrioventricular nodal conduction in humans. Evidence supporting a direct cholinergic action on ventricular muscle refractoriness. Circ Res. 1981 Aug;49(2):511–518. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.2.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prystowsky E. N., Naccarelli G. V., Jackman W. M., Rinkenberger R. L., Heger J. J., Zipes D. P. Enhanced parasympathetic tone shortens atrial refractoriness in man. Am J Cardiol. 1983 Jan 1;51(1):96–100. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu W., Ohe T., Kurita T., Takaki H., Aihara N., Kamakura S., Matsuhisa M., Shimomura K. Early afterdepolarizations induced by isoproterenol in patients with congenital long QT syndrome. Circulation. 1991 Nov;84(5):1915–1923. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.5.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipes D. P., Mihalick M. J., Robbins G. T. Effects of selective vagal and stellate ganglion stimulation of atrial refractoriness. Cardiovasc Res. 1974 Sep;8(5):647–655. doi: 10.1093/cvr/8.5.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]