Abstract

Enhanced contractility of airway smooth muscle (ASM) is a major pathophysiological characteristic of asthma. Expanding the therapeutic armamentarium beyond β-agonists that target ASM hypercontractility would substantially improve treatment options. Recent studies have identified naturally occurring phytochemicals as candidates for acute ASM relaxation. Several flavonoids were evaluated for their ability to acutely relax human and murine ASM ex vivo and murine airways in vivo and were evaluated for their ability to inhibit procontractile signaling pathways in human ASM (hASM) cells. Two members of the flavonol subfamily, galangin and fisetin, significantly relaxed acetylcholine-precontracted murine tracheal rings ex vivo (n = 4 and n = 5, respectively, P < 0.001). Galangin and fisetin also relaxed acetylcholine-precontracted hASM strips ex vivo (n = 6–8, P < 0.001). Functional respiratory in vivo murine studies demonstrated that inhaled galangin attenuated the increase in lung resistance induced by inhaled methacholine (n = 6, P < 0.01). Both flavonols, galangin and fisetin, significantly inhibited purified phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) (n = 7, P < 0.05; n = 7, P < 0.05, respectively), and PLCβ enzymes (n = 6, P < 0.001 and n = 6, P < 0.001, respectively) attenuated procontractile Gq agonists' increase in intracellular calcium (n = 11, P < 0.001), acetylcholine-induced increases in inositol phosphates, and CPI-17 phosphorylation (n = 9, P < 0.01) in hASM cells. The prorelaxant effect retained in these structurally similar flavonols provides a novel pharmacological method for dual inhibition of PLCβ and PDE4 and therefore may serve as a potential treatment option for acute ASM constriction.

Keywords: bronchodilation, flexiVent, myograph, phosphodiesterase, phytochemical

there are limited pharmacological options available to asthmatic patients that provide acute relaxation of airway smooth muscle (ASM). β-Agonists or anticholinergic medications remain the primary therapeutic classes of medications available for acute bronchodilation; however, in a growing number of patients frequent exacerbations remain a challenge. More recent formulations have combined long-acting β-agonists with inhaled steroids in an attempt to improve asthma symptomology. For example, in poorly controlled persistent asthmatic patients, the current recommendation is the addition of long-acting β-agonist (LABA) to be used in combination with an inhaled corticosteroid. Somewhat paradoxically, when asthma exacerbations occur in patients treated with LABAs, they are often also administered a shorter acting member of the same drug class (i.e., short-acting β-adrenoceptor agonists). Thus clinicians heavily rely on β-agonists (both short and long-acting), in both acute and chronic settings. This reliance has led to several concerns including the pathophysiological consequences of tolerance and airway hyperresponsiveness as well as a growing controversy regarding an association with negative clinical outcomes such as increased exacerbations and an increased risk of death with LABAs (13, 16, 21). These clinical concerns highlight the need to identify novel pharmacological interventions to achieve acute relaxation of ASM that minimize our dependence on β-agonists. More specifically, the identification of novel bronchodilators that target mechanistically distinct signaling pathways classically activated by β-agonist therapy would best complement existing treatment options available for bronchoconstriction.

Dual inhibition of two distinct, yet related enzyme pathways that promote airway constriction have been previously described by our group (22–24). Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase inhibitors, both selective and nonselective for phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4), have classically been used as adjunctive therapeutic options for airway bronchoconstrictive diseases (1). These PDE inhibitors work by increasing intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) to enhance ASM relaxation. Although a mechanistic overlap exists between cyclic PDE inhibitors and β-agonists in that their prorelaxation effect is mediated via an increase in intracellular cAMP, inhibition of the phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ) pathway is an attractive alternative since it mediates relaxation independent of cAMP modulation. By targeting PLCβ, attenuation of several downstream signaling effects not classically altered by β-adrenoceptor activation [e.g., increased inositol phosphates (IPs) and PKC activation] provides a complementary mechanistic approach to relaxation. Additionally, given recent evidence that suggests that chronic activation of the β-adrenoceptor increases expression and activity of PLCβ (12), inhibition of this pathway would seem an especially attractive therapeutic option in the face of widespread chronic β-agonist use. Despite these important considerations, there are no pharmacological options currently available to target this important procontractile pathway.

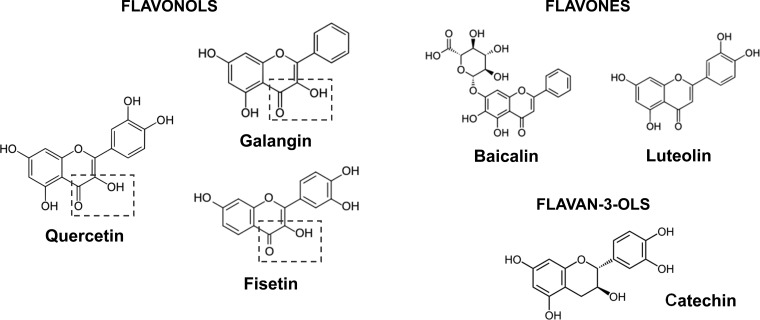

Botanical substances that inhibit the PLCβ enzyme resulting in a decreased generation of downstream second messengers have been previously described by our group. These prior studies demonstrate that a flavonoid compound, quercetin, relaxes ASM via dual inhibition of the PLCβ and PDE4 enzymes (22–24). Quercetin, which is found in high concentration in apples, belongs to a family of phytochemicals known as flavonoids that naturally occur in a variety of plants. These flavonoids are found ubiquitously in nature and are organized into subclasses based on structural variations that arise off a three-ringed backbone structure (Fig. 1). Quercetin belongs to the flavonol subclass for which the distinguishing feature of this subclass is a 3-hydroxyl bond and a 4-carbonyl moiety. Whether other flavonols structurally similar to quercetin also possess the ability to inhibit PLCβ and PDE4 and acutely relax ASM has not been evaluated.

Fig. 1.

Galangin, fisetin, and the known PLCβ/PDE4 inhibitor quercetin are members of the subclass flavonol family. The distinction of this subclass is a 3-hydroxyl, 4-carbonyl moiety located off the three-ringed flavonoid backbone. Other tested compounds are members of the flavone (baicalin and luteolin) and flavan-3-ol (catechin) families and lack the presence of both moieties in the specified structural position.

One flavonol with high structural similarities to quercetin is galangin. It is found in high concentrations in Alpinia oficinarum, a plant of the ginger family, and propolis, a resinous mixture that is a common constituent of honey and beeswax. In small clinical studies orally administered propolis has been shown to improve asthma clinical variables and lung mechanics and to decrease cytokine levels associated with airway inflammation (8). Galangin has been shown to relax bladder and vascular smooth muscle (2, 15), but its effect on ASM and the cellular mechanisms underlying its relaxation properties are unknown. Interestingly, galangin has also been shown to have an anti-inflammatory effect in the airways (26). Fisetin is an additional flavonol that is found in very high concentrations in strawberries and also shares anti-inflammatory properties (17). The role that either galangin or fisetin may play in primary airway bronchoconstrictive diseases, and more specifically their role in acute relaxation of ASM, remains underexplored.

In the present study we questioned whether flavonoid compounds of the flavonol family with close chemical structures to quercetin would acutely relax ASM in functional ex vivo and in vivo studies. We also questioned whether the underlying cellular mechanism of relaxation is analogous to quercetin-mediated PDE4 and/or PLC-β inhibition resulting in a decrease in downstream second messengers known to be important in ASM contraction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Murine tissue force studies.

All animal studies were approved by Columbia University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male A/J mice were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital, and tracheas were rapidly removed and placed in cold modified Krebs-Henseleit (KH) buffer (composition in mM: 115 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.91 CaCl2, 2.46 MgSO4, 1.38 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, and 5.56 d-glucose; pH 7.4). Following removal of connective tissue under a dissecting microscope, tracheas were cut in half axially, allowing for one-half of the trachea to be utilized in each myograph bath (DMT, Ann Arbor, MI). Each tracheal segment was equilibrated at 0.5 g of isotonic tension with periodic buffer changes (every 15 min; bubbled 95% O2-5% CO2 at 37°C). Following equilibration at resting tension, acetylcholine (ACh) EC50 concentrations for each individual tracheal segment were then determined by performing three sequential ACh dose-contraction response studies (100 nM to 1 mM). Trachea segments were then precontracted with an EC50 concentration of ACh, allowed to reach a stable plateau contraction (∼20 min), and 100 μM of flavonoid (galangin, fisetin, luteolin, baicalin, or catechin) or vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) was administered to each individual bath. Relaxation was assessed by measuring the percent of remaining contractile force from the ACh EC50 plateau contraction 15 min after the addition of the various flavonoids or vehicle to the organ bath. The force obtained after a plateaued ACh EC50 contraction represents 100% of muscle force and the baseline tension is represented by 0%.

Following these studies, we then determined the dose response for galangin by assessing the magnitude of relaxation achieved 15 min following treatment of an ACh EC50 contraction with vehicle or 10, 25, 50, or 75 μM of galangin.

Human tissue force studies.

To corroborate the findings of the murine model, human ASM (hASM) force studies were performed with similar methodology as described above. Briefly, hASM strips were acquired from tracheal discards from healthy donor lungs used in transplant surgery (deemed not human subjects research by IRB review). Following epithelial-denudement, hASM strips were suspended under isotonic force (1.5 g) in organ baths and equilibrated in KH buffer (composition in mM: 118 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 0.24 MgSO4, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 5.6 glucose; pH 7.4) for 1 h at 37°C. KH buffer was bubbled with a gas mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2, and buffer was exchanged every 15 min for 1 h during equilibration of tracheal rings at 1.5 g resting tension. All buffers included 10 μM indomethacin to block the synthesis of endogenous prostanoids. Following equilibration, three ACh dose response studies (100 nM to 1 mM) were performed. Strips were then contracted to their individually calculated EC50 and allowed to reach plateau force. Each hASM strip then received one of the following flavonoid compounds: galangin (100 μM), fisetin (100 μM), luteolin (100 μM), catechin (100 μM), baicalin (100 μM), or vehicle (DMSO 0.1%). The magnitude of relaxation was assessed at 15 min following flavonoid or vehicle treatments. Values reported are the percent of remaining contractile force of the ACh EC50-induced contraction at 15 min, with the force obtained after a plateaued ACh EC50 contraction representing 100% of muscle force and the baseline tension representing 0%.

PDE4 enzyme inhibition assay.

To determine whether inhibition of PDE4 was mechanistically responsible for the observed prorelaxant effects described in the above myograph studies, flavonoid-mediated PDE4 inhibition was measured by utilizing a PDE4D3 fluorescent polarization assay kit (no. 60345; BPS Bioscience) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. This cell-free assay employs a phosphodiester substrate FAM-cyclic 3′5′ AMP (200 nM), purified PDE4D3 enzyme (5 pg/μl), and phosphate-binding beads that in the presence of phosphodiesterase activity creates a FAM-labeled nucleotide bead complex. Following fluorescent stimulation (excitation 485 nm, emission 538, cutoff 530 nm; G factor 1.00) FAM-labeled nucleotide bead complex-mediated changes in fluorescent polarization were quantified by the following calculation:

(Ip = intensity with polarizers parallel; Ipp = intensity with polarizers perpendicular), such that increased PDE activity results in relatively greater polarization values. Specific reaction mixture constituents included the enzyme-substrate mixture containing 25 μl of FAM-cyclic 3′5′ AMP (200 nM), 20 μl of purified PDE4D3 enzyme (5 pg/μl), and either 5 μl of one of the following flavonoid compounds [galangin, fisetin, luteolin, baicalin, catechin (100 μM)], or rolipram (10 μM; positive control), or vehicle (0.1% DMSO). The negative control (no enzyme) was a mixture of 25 μl of FAM-cyclic 3′5′ AMP (200 nM), 20 μl of PDE assay buffer (from kit), and 5 μl vehicle (DMSO 0.1%). The total mixture (50 μl) of each reaction was then pipetted into a single microwell of a 96-well black, low-binding NUNC microtiter plate. The plate was incubated at room temperature for 1 h with gentle shaking on a rocking platform. Following this incubation, 100 μl of 1:200 diluted binding agent (containing the phosphate-binding beads) was added to each microwell and incubated for an additional hour at room temperature with gentle shaking on a rocking platform. Fluorescent polarization was then quantified in a FlexStation 3 microplate reader at 37°C (excitation 485 nm, emission 538, cutoff 530 nm; G factor 1.00). Values obtained are the average of the triplicate measurement for one experiment. Reported fluorescent polarization units (FPUs) for each compound were corrected for baseline FP obtained from negative control samples. Raw data for the flavonols and nonflavonols were analyzed separately by using the same vehicle controls.

PLCβ enzyme inhibition assay.

PLCβ enzymatic studies were also performed to determine whether flavonol-mediated inhibition of this enzyme contributed to the relaxation observed in myograph studies described above. This cell-free assay used the substrate 6,8-difluoro-4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate (DiFMUP 100 μM; Life Technologies D6567) prepared in experimental assay buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl and 0.1 mM CaCl2; pH 7.0). The enzyme utilized was purified phosphatidylinositol-specific PLCβ (Life Technologies P6466). In the presence of an enzyme-substrate complex, converted DiFUMP emits enhanced fluorescence. Preincubation with 10 μl of either 1) flavonoid compounds [galangin (100 μM), fisetin (100 μM), luteolin (100 μM), baicalin (100 μM), or catechin (100 μM)]; 2) PLCβ inhibitor U-73122 (50 μM); or 3) respective vehicles (0.1% and 2% DMSO) was performed with 90 μl of the PLCβ enzyme (0.25 U/ml, diluted in assay buffer). Respective negative controls (without enzyme) were also performed simultaneously to account for background fluorescence and contained 90 μl of experimental buffer with 10 μl of either the flavonoid compounds [galangin (100 μM), fisetin (100 μM), luteolin (100 μM), baicalin (100 μM), or catechin (100 μM)], the PLCβ known inhibitor U-73122 (50 μM), or respective vehicles (0.1% and 2% DMSO). Samples were loaded to an individual microwell on a 96-well clear-bottom plate and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Following this pretreatment 100 μl of DiFMUP was added and the fluorescence was read every 2.5 min for 1 h on a FlexStation 3 microplate reader (358 nm excitation, 455 nm emission; Molecular Devices) at 37°C. Measurements obtained reflect the slope of relative fluorescent units (RFU) over 60 min. Reported slope values were corrected for background fluorescence. Analyses were performed on raw data for flavonol vs. nonflavonol compounds with the same corresponding vehicle control used in each separate analysis. Subsequent dose-response studies (at 1, 10, 50, and 100 μM) were also performed for galangin and fisetin by the methodology outlined above.

IP synthesis studies.

To determine whether downstream effectors of PLCβ enzyme activity were reduced in the presence of flavonol compounds, in vitro radioactive IP assays were conducted as previously described (6). Briefly, confluent ASM cells stably transfected to express the M3 muscarinic receptor (14, 24) were loaded with myo-[3H]inositol (6 μl/ml; 60 mCi/mmol) overnight in inositol- and serum-free DMEM media in 24-well plates at 37°C in a cell culture incubator. On the day of study, cells were washed two times with buffer (HBSS/10 mM LiCl; 37°C) and were pretreated for 15 min with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), fisetin (100 μM), or galangin (100 μM) and then were stimulated with 10 μM ACh. Assays were stopped at 30 min by the addition of 330 μl cold methanol, followed by 660 μl of chloroform, and newly synthesized [3H]IPs were isolated from the top aqueous phase of this mixture by column chromatography. The amount of newly synthesized [3H]IPs (in cpm) was expressed as a ratio of the amount of [3H]inositol in each well which accounts for any differences in cell density or [3H]-myo-inositol incorporation into the plasma membrane.

IP receptor competitive binding assay.

We performed competitive radioligand assays to determine whether binding of galangin or fisetin directly to the inositol triphosphate (IP3) receptor could contribute to their prorelaxant effects. Using a commercially available inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate [3H] radioreceptor assay kit (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, catalog no. NEK064), we first constructed a control curve of specific [3H]IP3 binding in the membrane preparation included with the kit according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The prebound [3H]IP3/membrane preparation was incubated for 1 h at 4°C with the IP3 standard (0.24–24 nM final). In parallel tubes, 100 μM of galangin, fisetin, or the vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) was incubated with the prebound [3H]IP3/membrane preparation. Following centrifugation at 2,500 g for 20 min at 4°C to pellet the membrane fraction, the supernatant was decanted and the membrane fraction was solubilized in 50 μl 0.15 M NaOH for 10 min and counted by liquid scintillation counting. Nonspecific counts were determined by tubes including saturating concentrations of inositol hexaphosphate (IP6) as validated and recommended by the manufacturer. Nonspecific counts were subtracted from all other values (unlabeled IP3 standards and samples) to determine specific counts expressed as counts per minute.

Dual calcium flux assay.

To assess the potential of flavonol inhibition of IP3-mediated sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) calcium release, we employed a dual calcium flux assay (3) to simultaneously assess changes in both cytosolic and SR calcium fluorescence. Immortalized hASM cell lines modified to stably express human telomerase reverse transcriptase (as previously described) (5) were a kind gift from Dr. William Gerthoffer (University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL). Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 (DMEM/F12) media (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Cells were transferred to FBS-free DMEM/F12 media for 48 h prior to experimentation. Differential calcium indicator loading was performed as previously described utilizing both fura 2 (a high-affinity indicator measuring cytosolic Ca2+ concentration) and Mag-fluo-4 (a low-affinity indicator measuring SR Ca2+ concentration) (19). In a black-walled 96-well plate, hASM cells at 100% confluence were washed four times with fluorescence buffer (FB) (concentration in mM: 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 Na2HPO4, 0.5 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 glucose, pH 7.4, 37°C). Cells were then incubated with 5 μM Mag-fluo-4 AM with 0.1% pluronic acid in FB for 40 min at 37°C. Cells were again washed three times and reincubated with 5 μM fura-2 AM with 0.05% pluronic acid for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were washed three additional times with FB and incubated for 30 min at room temperature (RT). Cells were then pretreated with galangin (1, 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μM final) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 10 min. Calcium fluorescence was then assessed in a Flexstation 3 plate reader (excitation: 340, 380, 465; emission: 510) to determine baseline readings for 40 s followed by injection of bradykinin (10 μM final) with differential calcium flux assessed every 5 s for a total of 400 s. Fura 2 fluorescence is reported as a ratio with normalization to baseline (zero time) as expressed below:

All Mag-fluo-4 recordings were also normalized to baseline by dividing by the zero time point at the beginning of the experiment. Calculations to determine the calcium response were performed separately for the two calcium indicators. The values obtained represent the difference between the peak and nadir values recorded for the entirety of the experiment (400 s) each individual microwell.

Fluo-4 calcium studies.

Preliminary experiments revealed fisetin exhibits confounding autofluorescence at 510 nm when excited at 340 nm, thereby obviating our ability to use fura 2 with this particular flavonol (data not shown). Therefore, to assess the effect of fisetin on Gq-evoked intracellular calcium elevation, we utilized Fluo-4 calcium dye indicator exciting at a wavelength (485 nm) that does not induce confounding autofluorescence from fisetin at its emission wavelength (516 nm). To correlate these studies with our observations from the functional organ bath studies and to demonstrate flavonol-mediated inhibition of Gq-coupled calcium elevation is not limited to bradykinin signaling, we used ACh to stimulate calcium flux. hASM cells stably transfected to express the human M3 muscarinic receptor were used as previously described (23). Cells were cultured on black-walled 96-well plates to 100% confluence and washed four times with warmed modified (37°C) Hanks' balanced salt solution buffer (concentration in mM: NaCl 137.93, KCl 5.33, CaCl2 2, MgSO4 1, HEPES 2.38, glucose 5.5, pH to 7.4). Cells were loaded with 5 μM Fluo-4 AM for 45 min and washed an additional three times with buffer. Cells were then pretreated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or fisetin 100 μM or galangin 100 μM (interexperimental positive control) for 10 min after which they were placed in a FlexStation 3 microplate reader. Baseline fluorescence was measured, and ACh (100 μM final concentration) was pipetted into the wells of the plate. Fluorescence was read every 2 s for 240 s at an excitation wavelength of 488, an emission wavelength of 516, and a cutoff filter of 495. Fluorescence values were reported as F/F0 according to the calculation: {ΔF = [(488 nm)f − (488 nm)0]/(488 nm)0}.

Immunoblot.

Immunoblot analysis was performed for phosphorylated CPI-17, a distal downstream product of diacylglycerol activation of protein kinase C, which would be expected to be inhibited with PLCβ inhibition. For these experiments, immortalized hASM cells overexpressing the M3 receptor were placed in FBS-free M199 medium for 48 h prior to experimentation. Medium was then replaced with HBSS for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were treated with 1) 10 μM ACh, 2) 100 μM of galangin, 3) 10 μM ACh and 100 μM galangin, or 4) DMSO 0.1% (vehicle) for 20 min prior to harvest. Cells were disrupted with cell lysis buffer [Cell Signaling no. 9803 with protease inhibitor cocktail set 3 (Calbiochem 1:200) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail set 1 and 2 (Sigma 1:100)] and lysed at 4°C by using a Vibra-Cell sonicator (Sonics & Materials) for 3 s (130 W, 20 kHz). Whole cell lysates were solubilized by heating at 95°C for 5 min in gel loading buffer. Samples were resolved on a SDS-PAGE gel (4–15% precast polyacrylamide gel; Bio-Rad) over 3 h (50 V) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Blockade of nonspecific binding sites was performed with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) over 1 h at RT. Membranes were then probed overnight at 4°C with a 1:2,000 dilution of phosphorylated CPI-17 (Thr38 anti-rabbit Abcam no. 52174). After a series of washes, PVDF membranes were incubated for 1 h at RT with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies (1:40,000 dilution in 5% BSA in 50 mM Tris + 150 mM NaCl + 0.05% Tween 20; GE Healthcare NZ934V). Super Signal West Femto (Life Technologies no. 34095) was used according to the manufacturer's recommendations. To evaluate for β-actin, a series of washes of the PVDF membrane were performed after initial development of phospho-CPI-17 and incubation was performed with 1:20,000 dilution β-actin (anti-rabbit, Cell Signaling no. 4970) with secondary antibody incubation and development performed in the same fashion as described above. Phosphorylated CPI-17 intensities were corrected for β-actin and quantified by use of UVP Vision Works 5 densitometry software.

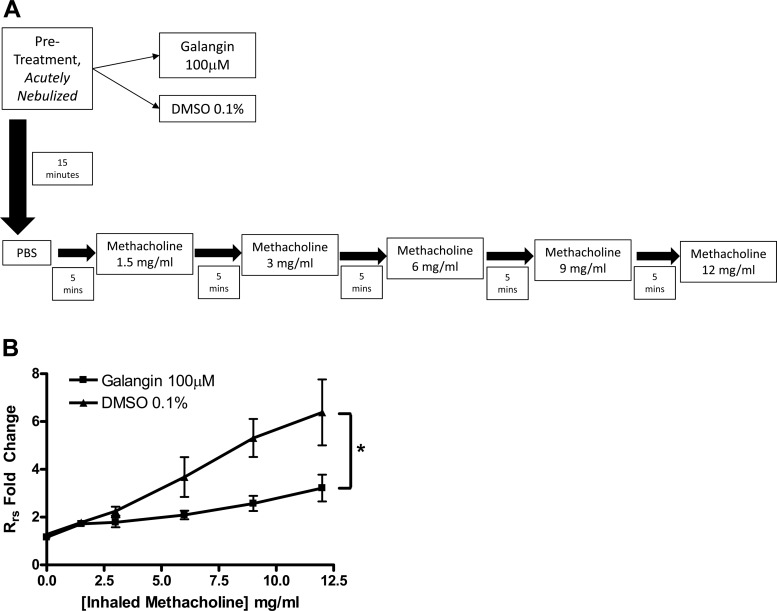

Measurement of murine lung mechanics.

In vivo confirmation of flavonol-mediated relaxation of ASM in vitro was performed in mice by the forced oscillatory technique for lung resistance measurements. Airway measurements were assessed by using a flexiVent FX1 module with an in-line nebulizer (SciReq, Montreal, Canada). Male A/J mice (20–25 g) were anesthetized with 10 mg/kg pentobarbital (Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI), paralyzed with an intraperitoneal injection of 0.1 ml succinylcholine (10 mg/ml), and immediately mechanically ventilated at 150 breaths/min with tidal volume of 10 ml/kg. Animals were given a 20 s nebulization of either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or galangin (100 μM final) in PBS 15 min before nebulized methacholine (MCh) challenge. Measurements of the respiratory resistance (Rrs) were obtained at baseline (PBS, 0 MCh) and following cumulatively increasing doses of nebulized MCh (1.5, 3, 6, 9, 12 mg/ml, respectively) delivered in 5-min intervals. Core temperature was maintained at 37°C with a heating blanket connected to a servocontroller via rectal temperature probe. Heart rate was continually monitored throughout.

Data collected represent the average of the first three resistance readings obtained after acute nebulization at each MCh dose, corrected for baseline airway resistance obtained at the beginning of the challenge. MCh responses were quantified by using area under the curve (AUC) for each individual mouse, compiled into two groups (galangin vs. vehicle pretreatment cohorts) and then analyzed by unpaired t-test comparison.

Statistical analyses.

In functional organ bath experiments, the reported n refers to the number of tissues/rings employed in a particular study group. From each mouse we routinely obtain two rings for study. In the case of human samples, the number of tissue strips we obtain is variable from harvest to harvest but usually allows for at least three strips of tissue up to a maximum of eight strips. The results from organ bath using human tissue are representative of tissues obtained from four patients. In the case of cell-based experiments, the n refers to experiments performed (assays are run in duplicate or triplicate on a given day; results are then averaged to provide an n of 1). Data were analyzed by ANOVA with repeated measures unless otherwise noted. Bonferroni posttest analysis was applied for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05 unless otherwise noted, and all values are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean.

RESULTS

Flavonols elicit relaxation of precontracted murine ASM ex vivo.

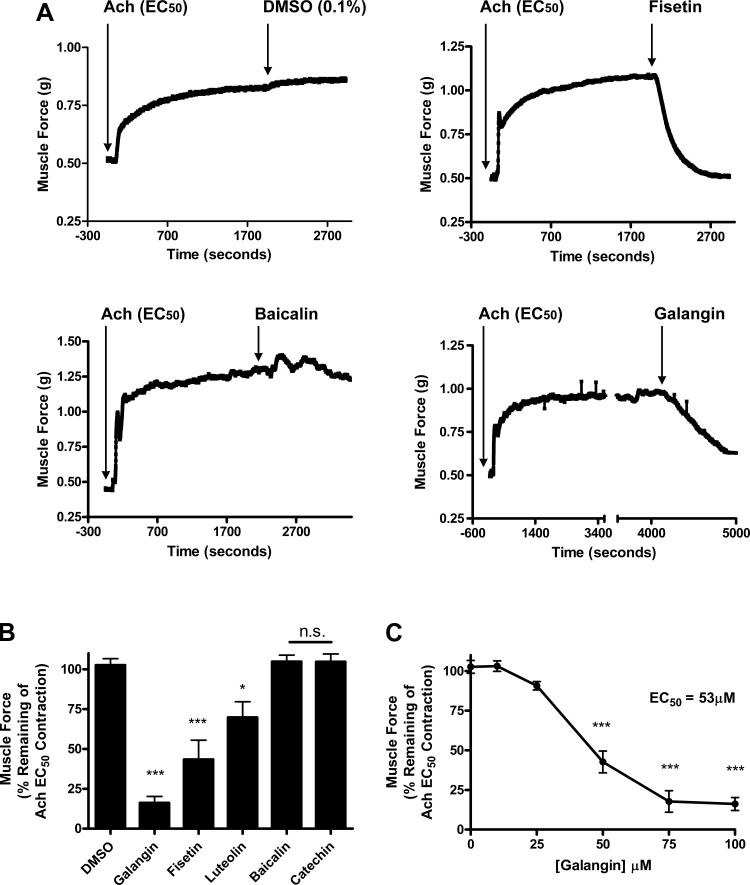

We measured the ability of five flavonols (Fig. 1) to induce relaxation of an established EC50 ACh contraction in isolated mouse tracheal rings suspended in myographs. Using equimolar concentrations of each flavanol (100 μM) we found three compounds that induce significant relaxation (Fig. 2A). The residual ACh-induced contraction after treatment with galangin (16 ± 4.0%, n = 4), fisetin (43 ± 12.13%, n = 5), or luteolin (69 ± 9.7%, n = 6) was significantly decreased at 15 min posttreatment (P < 0.001, <0.001, and <0.05, respectively) compared with vehicle, DMSO (102.6 ± 4.1%, n = 5) (Fig. 2B). All three of these compounds share a 4-carbonyl motif (Fig. 1). Among all compounds tested, galangin proved the most potent (Fig. 2B). In subsequent studies, galangin also exhibited a dose-dependent effect with significant differences in relaxation from an ACh-induced contraction at concentrations of 50 μM (42 ± 6.9%, n = 3) and 75 μM (17 ± 6.7%, n = 3). The calculated IC50 for galangin was 53 μM (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Several of the flavonoids tested relaxed precontracted murine airway smooth muscle (ASM). A: representative tracing of tension recordings in murine ASM contracted with acetylcholine (ACh) EC50 concentration, followed by treatment with flavonoid or vehicle. B: galangin, fisetin, and luteolin (100 μM) significantly relax an ACh-induced contraction measured at 15 min after treatment (***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05) compared with vehicle (DMSO 0.1%). Baicalin and catechin (100 μM) did not induce significant relaxation. C: the effects of galangin respond in a dose-dependent fashion with significant relaxation achieved at 50, 75, and 100 μM. The calculated EC50 for galangin is 53 μM.

Flavonols attenuate hASM contraction in vitro.

To corroborate our murine tracheal ring results in hASM, we functionally screened these compounds in hASM in vitro relaxation studies. We observed a flavonol-specific prorelaxant effect with the same group of flavonoids when testing them against ACh-precontracted hASM tracheobronchial strips (Fig. 3). The flavonols galangin (61 ± 7.5%, n = 8), quercetin (65 ± 5.2%, n = 9), and fisetin (43 ± 4.5%, n = 6) at 100 μM concentration all had a significant reduction in remaining airway tone after an (ACh) EC50-induced contraction at 15 min posttreatment (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) compared with their vehicle, DMSO 0.1% (93.6 ± 2.0, n = 9) (Fig. 3). Luteolin (86.9 ± 4.5%, n = 9) did not show any significant effect. All four compounds share a 4-carbonyl moiety; however, luteolin lacks the 3-hydroxyl group present in the other three compounds (galangin, fisetin, and quercetin), suggesting that the presence of both of these moieties is responsible for the pronounced relaxation effect we observed.

Fig. 3.

Relaxation of precontraction human ASM (hASM) strips is flavonol specific. Flavonols galangin and fisetin (100 μM) significantly relax an ACh-induced contraction measured 15 min after treatment (***P < 0.001) compared with vehicle (DMSO 0.1%). Quercetin (100 μM), a previously studied flavonol, also significantly relaxed precontracted hASM (**P < 0.01). Luteolin (100 μM) did not achieve a significant effect in hASM.

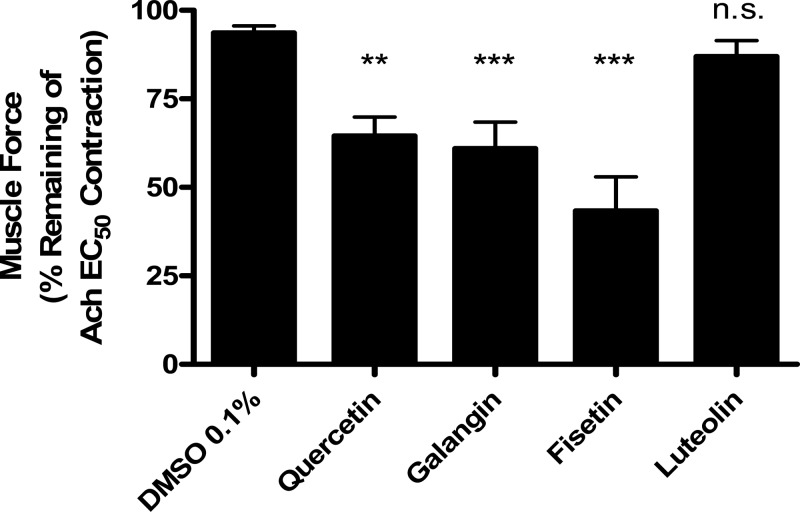

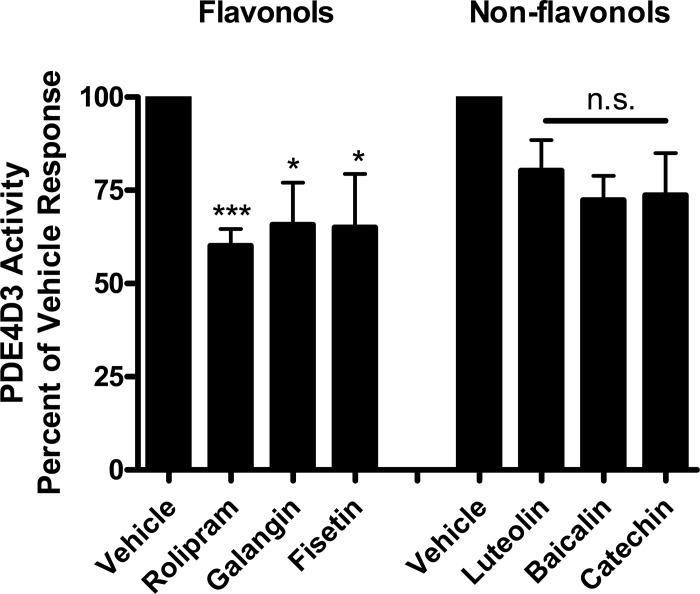

The flavonols galangin and fisetin inhibit PDE4D3.

Since quercetin-mediated relaxation was found to be mediated through the inhibition of two key enzymes that regulate ASM tone (PLCβ and PDE4) (22), we sought to determine whether a similar dual mechanism was also responsible for the galangin and fisetin prorelaxant functional effects. Using a cell-free fluorescent polarization based assay we found significant consistency with regards to a flavonol vs. nonflavonol PDE4D3 effect. Both flavonols, galangin 100 μM (65.8 ± 11.1%, n = 7) and fisetin 100 μM (65.0 ± 14.4%, n = 7), as well as the positive control, rolipram 10 μM (60.1 ± 4.5%, n = 7), significantly reduced the enzyme activity of PDE4D3 (P < 0.05, P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively). The nonflavonol compounds luteolin (80.3 ± 8.2%, n = 7), baicalin (72.4 ± 6.5, n = 7), and catechin (73.8 ± 11.2, n = 7) at functionally relevant equimolar concentrations (100 μM) did not exhibit significant inhibition of PDE4D3 enzyme activity (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Purified phosphodiesterase enzyme (PDE4D3) activity is inhibited in the presence of the flavonol compounds fisetin and galangin (100 μM), consistent with a flavonol subfamily-specific effect (*P < 0.05). The nonflavonols luteolin, baicalin, and catechin (100 μM) failed to inhibit purified PDE4D3 enzyme activity (n.s., nonsignificant) compared with vehicle (DMSO 0.1%). The positive control rolipram (10 μM) effectively inhibited activity (***P < 0.001).

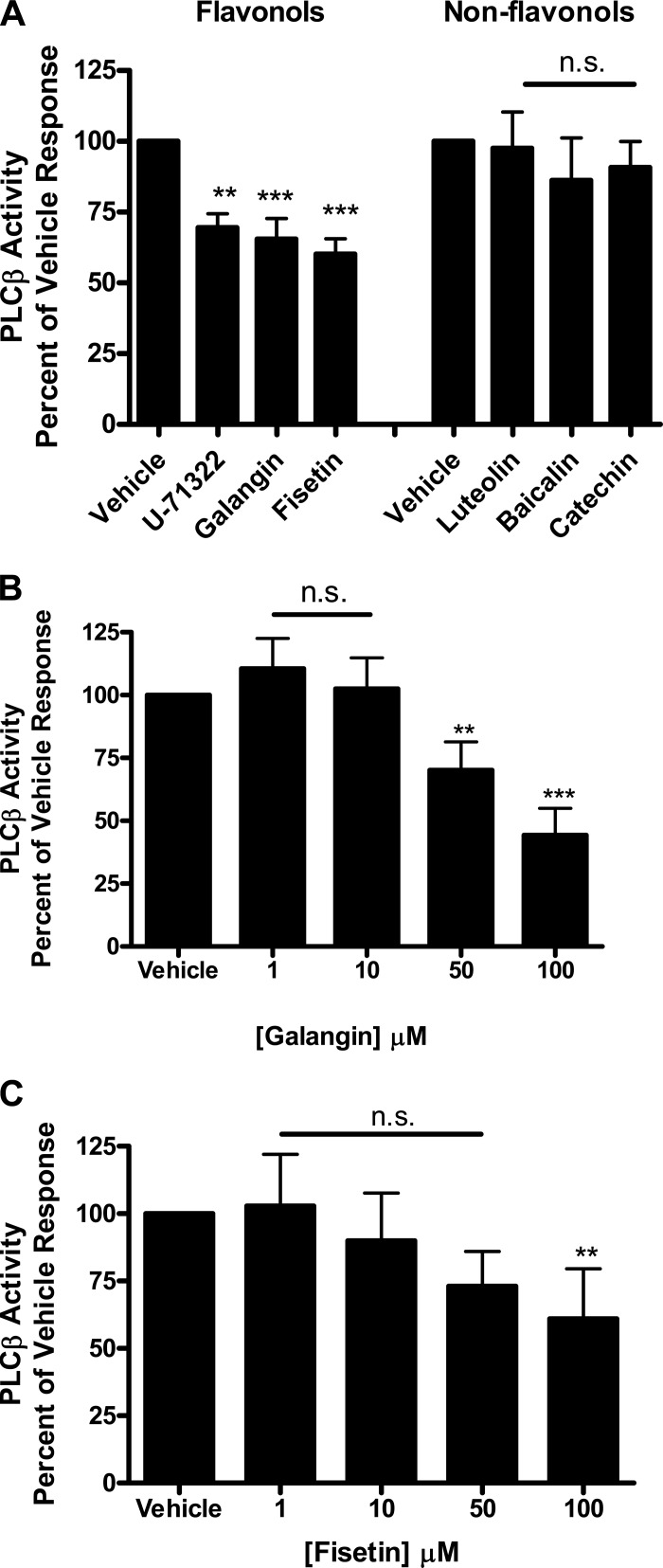

Structurally similar flavonols inhibit PLCβ activity.

There was also remarkable consistency with regard to a subfamily-specific flavonol effect observed in the PLCβ activity assay supporting a dual-enzyme inhibition hypothesis. Both galangin (65.4 ± 7.3%, n = 6) and fisetin (60.2 ± 5.3%, n = 6) (100 μM) significantly inhibited PLCβ activity (***P < 0.001) compared with vehicle, DMSO 0.1%. A known PLCβ inhibitor, U-71322 (50 mM), served as a positive control, demonstrating significant inhibition of PLCβ activity (69.5 ± 5.0%, n = 6) (**P < 0.01) compared with vehicle, DMSO 2%. Luteolin (97.5 ± 12.8%, n = 6), baicalin (86.3 ± 15.0%, n = 6), and catechin (90.8 ± 9.2%, n = 6) (100 μM) did not significantly inhibit PLCβ enzyme activity (Fig. 5A). The observed inhibition suggests a mechanistic basis for the functional organ bath data demonstrated in murine and human tissue. Galangin showed a significant difference at concentrations 50 μM (70.2 ± 11.3%, n = 6) and 100 μM (44.4 ± 10.6%, n = 4) compared with vehicle (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) but not at concentrations of 1 μM (110.6 ± 11.0%, n = 6) and 10 μM (102.5 ± 12.3%, n = 6), respectively (Fig. 5B). Fisetin did not show a dose-dependent effect on PLCβ inhibition at the concentrations we analyzed (Fig. 5C), with no significant inhibition noted at concentrations 1 μM (102.9 ± 19.1%, n = 6), 10 μM (90.0 ± 17.7%, n = 6), and 50 μM (73.2 ± 12.9%, n = 6). However, fisetin retained inhibition at 100 μM (61.0 ± 18.5%, n = 6) (Fig. 5C) compared with vehicle (**P < 0.01).

Fig. 5.

A: purified phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ) enzyme activity is inhibited in the presence of galangin and fisetin (100 μM) (***P < 0.001). The intraexperiment positive control, U-71322 (50 μM), a known PLCβ inhibitor, also significantly inhibits PLCβ (**P < 0.01). The nonflavonol compounds luteolin, baicalin, and catechin (100 μM) did not significantly inhibit PLCβ enzyme activity (n.s., nonsignificant). B: the effects of galangin are also noted at lower concentrations with inhibition occurring at 50 μM, in addition to 100 μM (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, respectively) C: Fisetin shows an effect at 100 μM (**P < 0.01) but not at lower concentrations compared with vehicle (DMSO 0.1%).

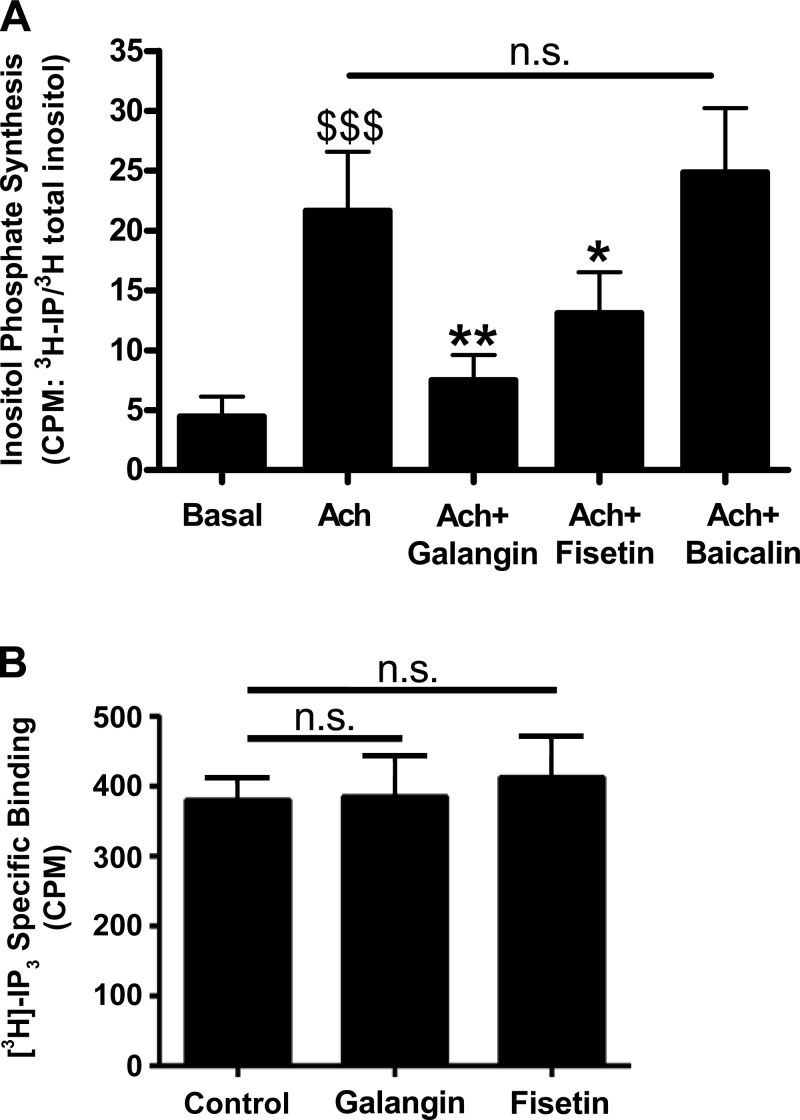

Galangin and fisetin inhibit ACh-stimulated production of IP3 but do not competitively bind to IP3 receptors.

When PLCβ is activated it cleaves phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into IP3 and diacylglycerol (DAG), which in turn activates protein kinase C. Given that these flavonols showed inhibition of purified PLCβ, we next tested whether they reduced production of IP3 (a well-characterized downstream mediator of PLCβ) in hASM cells. Using radiolabeled inositol (I), we demonstrate that IP synthesis is enhanced in hASM cells following treatment with the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) agonist ACh (21.7 ± 5.0 [3H]IP/[3H]I cpm, n = 5) ($$$P < 0.001) and is attenuated in the presence of galangin (7.5 ± 2.1 [3H]IP/[3H]I cpm, n = 5) (**P < 0.01) or fisetin (13.1 ± 3.4 [3H]IP/[3H]I cpm, n = 5) (*P < 0.05) pretreatment. Baicalin, a flavonoid that had been previously shown to have no acute relaxation effect on ASM tone, did not attenuate the ACh-induced increase in [3H]IP synthesis (Fig. 6A). In an effort to determine whether a component of relaxation induced by galangin or fisetin is due to their competitive binding to the IP3 receptor, we measured specific binding of [3H]IP3 to membrane preparations in the presence of 100 μM galangin, 100 μM fisetin, or their vehicle (0.1% DMSO). Galangin or fisetin did not affect [3H]IP3-specific binding (n = 7) (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

A: inositol phosphate synthesis was stimulated for 30 min by ACh (10 μM) with or without a 15 min pretreatment with 100 μM of galangin, fisetin, or baicalin. All cells were exposed to the same vehicle (0.1% DMSO) during these incubations (P < *0.05 and **0.01, respectively, compared with ACh alone; $$$P < 0.001 compared with basal). B: specific competitive binding of [3H]inositol triphosphate ([3H]IP3) was measured in membrane preparations in the presence of 100 μM galangin, 100 μM fisetin, or control (0.1% DMSO). There was no effect of galangin or fisetin on specific binding (n = 7), n.s. = not significant.

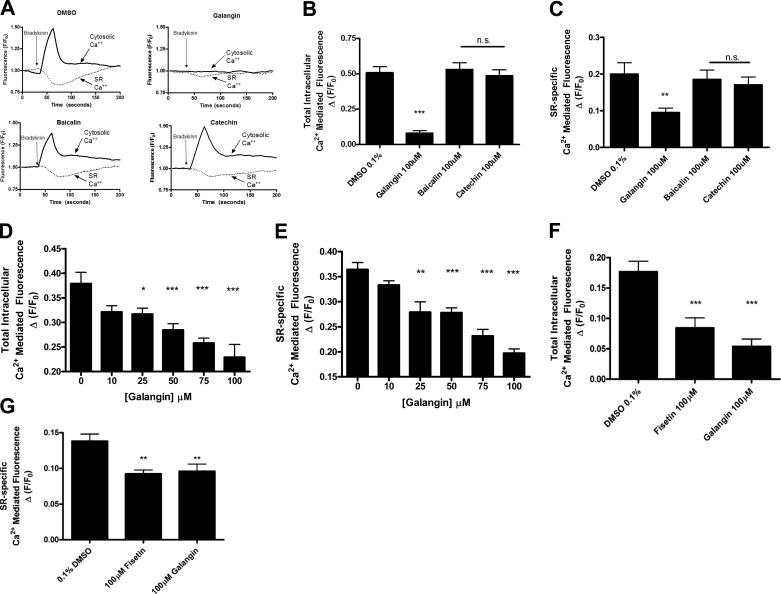

The flavonols galangin and fisetin attenuate GPCR-mediated cytosolic calcium elevations and SR-specific calcium release.

A major intracellular target of IP3 is the SR, resulting in calcium release from internal stores to elevate total cytosolic calcium. To correlate our IP assay findings to SR-mediated calcium release we tested whether galangin and fisetin would attenuate Gq-mediated elevations in cytosolic calcium with use of either the high-affinity fura 2 fluorophore (for galangin studies) or the Fluo-4 fluorophore (for confirmatory fisetin studies) and simultaneous emptying of calcium from the SR using the low-affinity Mag-fluo-4 fluorophore. Representative tracings employing fura 2 and galangin are depicted in Fig. 7A. Here, we observed that the total cytosolic and SR-specific calcium responses induced by bradykinin in a monolayer of hASM cells was attenuated by 100 μM of galangin compared with the DMSO vehicle (0.08 ± 0.02 RFUs, n = 11) (***P < 0.001) and (0.09 ± 0.01 RFUs, n = 11) (**P < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 7, B and C). Consistent with their inability to inhibit purified PLCβ, catechin or baicalin were without significant effects. Galangin also showed significant attenuation of the total cytosolic calcium rise that occurs in the presence of bradykinin at lower concentrations of 25 μM (0.32 ± 0.02 RFUs, n = 6) (*P < 0.05), 50 (0.28 ± 0.01 RFUs, n = 7) (***P < 0.001), and 75 μM (0.26 ± 0.01 RFUs, n = 5) (***P < 0.001) (Fig. 7D) as well as SR calcium release at 25 μM (0.28 ± 0.02 RFUs, n = 6) (**P < 0.01), 50 μM (0.28 ± 0.01 RFUs, n = 7) (***P < 0.001) and 75 μM (0.23 ± 0.01 RFUs, n = 5) (***P < 0.001) (Fig. 7E). Similar results were also observed in parallel studies employing Fluo-4 to examine the capacity of fisetin treatment to attenuate ACh-induced elevations in intracellular calcium. In these studies, we confirmed that both flavonols [galangin (100 μM) or Fisetin (100 μM)] significantly attenuate ACh-mediated increases in total cellular calcium release (0.08 ± 0.02 RFUs, n = 11 and 0.05 ± 0.01 RFUs, n = 11;, respectively) compared with vehicle in hASM cells overexpressing the M3 receptor (0.18 ± 0.02 RFUs, n = 14 ***P < 0.001) (Fig. 7F). Additionally, both galangin (100 μM) and fisetin (100 μM) inhibit SR-specific calcium (Mag-fluo-4) release mediated by ACh (0.09 ± 0.01 RFUs, n = 6 and 0.09 ± 0.01 RFUs, n = 7;, respectively) compared with vehicle in hASM cells overexpressing the M3 receptor (0.14 ± 0.01 RFUs, n = 8 **P < 0.01) (Fig. 7G).

Fig. 7.

A: representative tracings showing the bradykinin-stimulated calcium release by using a dual indicator for total cellular (fura-2) and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)-specific calcium (Mag-fluo-4) release. B: galangin (100 μM) attenuates bradykinin (10 μM)-mediated increases in total cellular calcium (Fura-2) release compared with vehicle, DMSO 0.1% (***P < 0.001, n = 11). Baicalin and catechin do not show an effect. C: galangin (100 μM) also inhibits SR-specific calcium (Mag-fluo-4) release compared with vehicle (**P < 0.01, n = 11). Baicalin and catechin do not show an effect. D: galangin inhibits total cytosolic calcium levels at concentrations of 25 (*P < 0.05), 50 (***P < 0.001), and 75 μM compared with vehicle control, DMSO 0.1%. E: galangin also inhibits SR calcium release at corresponding lower concentrations of 25 μM (**P < 0.01), 50 μM (***P < 0.001), and 75 μM (***P < 0.001) compared with vehicle control, DMSO 0.1%. F: galangin (100 μM) or fisetin (100 μM) attenuates ACh (100 μM)-mediated increases in total cellular calcium (Fluo-4) fluorescence compared with vehicle in hASM cells overexpressing the M3 receptor (***P < 0.001, n = 11–14). G: galangin (100 μM) or fisetin (100 μM) inhibit sarcoplasmic reticulum-specific calcium (Mag-fluo-4) release following treatment with ACh (100 μM) compared with vehicle in hASM cells overexpressing the M3 receptor (**P < 0.01, n = 6–8).

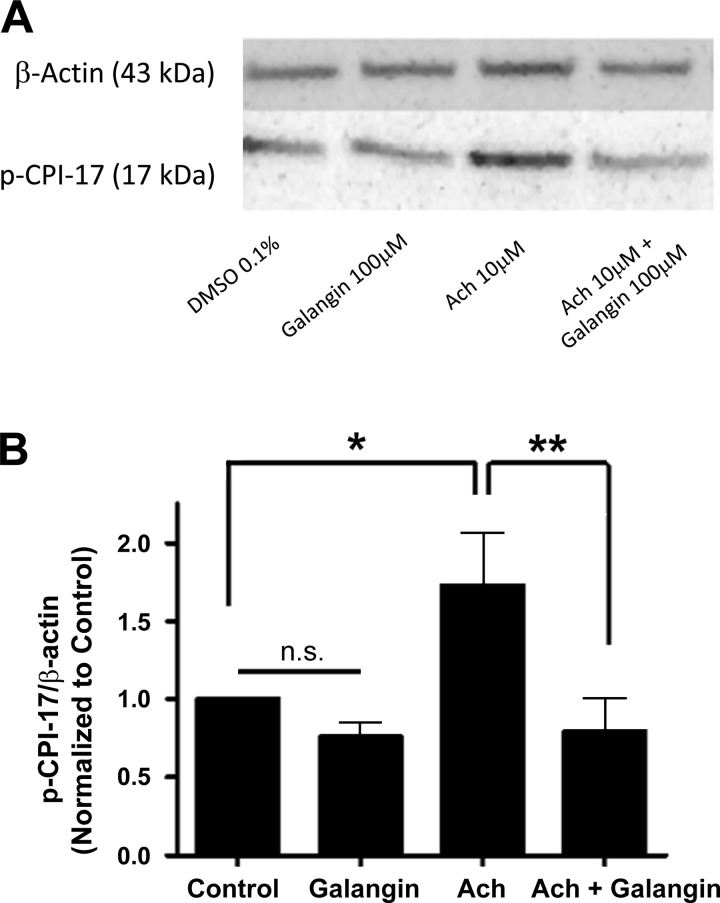

Galangin inhibits phosphorylation of CPI-17.

To determine whether flavonoid modulation of PLCβ was not solely limited to the IP3 pathway, we also assessed the impact of galangin treatment on a PLCβ downstream second messenger of DAG: PKC phosphorylation of CPI-17. This was determined by quantifying the phosphorylation state of the threonine 38 residue on CPI-17 (Fig. 8A). In primary hASM cells overexpressing the M3 receptor, the addition of 10 μM of ACh caused a significant increase in phosphorylation of CPI-17 compared with vehicle control, DMSO 0.1% (1.73 ± 0.3 n = 9) (*P < 0.05). Coincubation of galangin (100 μM, 20 min) with ACh 10 μM prevented this ACh induced increase in phosphorylation (0.79 ± 0.2, n = 9) (**P < 0.01) (Fig. 8B), suggesting an inhibition of the DAG arm of the PLCβ pathway in the presence of the flavonol galangin.

Fig. 8.

A: representative image of immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of CPI-17 (threonine 38) in hASM cells overexpressing the M3 receptor. B: in primary hASM, treatment with 10 μM ACh for 20 min increased CPI-17 phosphorylation compared with vehicle control, DMSO 0.1% (*P < 0.05). This increase in phosphorylation was attenuated when ACh was coincubated with galangin 100 μM (20 min) (**P < 0.01).

Nebulized galangin inhibits murine MCh-induced bronchoconstriction.

To further characterize the clinical applicability of galangin, in vivo murine experiments were performed to measure lung resistance changes in response to a MCh challenge that was performed after pretreatment with either galangin 100 μM or vehicle (Fig. 9A). When galangin was acutely nebulized 15 min prior to a serial MCh challenge, the increases in Rrs was significantly reduced compared with nebulized vehicle (0.1% DMSO) (25.8 ± 2.4 AUC vs. 45.2 ± 6.8 AUC, n = 6 and 4, respectively) (**P < 0.01) (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

A: protocol for murine in vivo airway resistance measurements. All treatments were acutely nebulized to anesthetized mice with cannulated tracheas and ventilated at 150 bpm. PBS [0 methacholine (MCh)] was first administered followed by serial MCh doses spaced 5 min apart to a maximum of 12 mg/ml. B: in vivo airway resistance measurements following MCh dose-response challenges in male A/J mice; 25 μl of galangin (100 μM) (n = 6) significantly attenuated the MCh induced increases in airway resistance (*P = 0.01) compared with vehicle, DMSO 0.1% (n = 6 and 4, respectively).

DISCUSSION

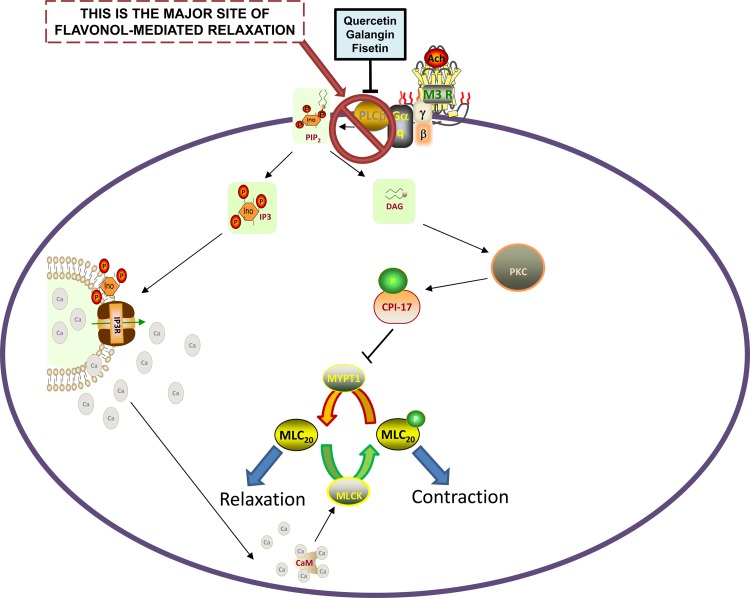

The primary findings of this study are that flavonols (galangin and fisetin) relax ACh-precontracted murine or hASM ex vivo and attenuate MCh-induced lung resistance in a murine model in vivo (Fig. 10). Mechanistic studies with purified cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase-4D3 (PDE4D3) and phospholipase Cβ enzymes reveal a potent flavonol-specific pattern of inhibition. In hASM cells, galangin inhibited Gq receptor-coupled increases in both total and sarcoplasmic-specific intracellular calcium. Furthermore, Gq receptor-coupled activation leading to IP synthesis was also reduced by galangin and fisetin, and diacylglycerol production was attenuated as demonstrated by a reduction in CPI-17 phosphorylation in the presence of galangin. There was significant consistency in the mechanistic findings between our ex vivo tissue, in vitro cellular, and purified enzyme assays results. The flavonols that relaxed intact ASM, both human and murine, inhibited the two phosphodiesterase pathways (PDE4D3 and PLCβ) that are known procontractile pathways. The flavonoids that did not relax intact ASM did not inhibit either of these pathways (PDE4D3 or PLCβ) and had no effect on Gq-signaling mediators of the PLCβ pathway.

Fig. 10.

Proposed mechanism by which quercetin, galangin, and fisetin inhibit PLCβ, resulting in inhibition of downstream signaling events that promote contraction. Inhibition of PLCβ decreases inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) synthesis, the latter of which decreases PKC activation and subsequent CPI-17 phosphorylation. Decreased CPI-17 phosphorylation is thought to promote reduced MYPT1 inhibition, leading to MLC20 dephosphorylation, which favors relaxation. Direct blockade of PLCβ activation may also lead to inhibition of IP3 synthesis and a subsequent reduction in calcium released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Reduced calcium contributes to reduced calcium-calmodulin (CaM) stimulation of MLC kinase (MLCK)-mediated phosphorylation of MLC20 (prorelaxant signaling event). INO, inositol; IP3R, inositol triphosphate receptor; MLC20, myosin light chain; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate.

The main structural difference of these flavonols vs. nonflavonols is the presence of a 3-hydroxyl, 4-carbonyl moiety off the three-ringed flavonoid backbone (Fig. 1). Taken together, these findings suggest that flavonols, in particular galangin, fisetin, and quercetin, inhibit two key enzymes in the maintenance of ASM contraction and that the presence of specific structural moieties may be responsible for the observed effect. Our initial hypothesis was to investigate whether a structure-function relationship could be described for those flavonoids that were chemically similar to quercetin, which was supported by our functional observations with galangin and fisetin. Thus it is plausible that specific moieties on the flavonoid structural backbone may be responsible for the observed enzymatic effects.

Although the ability of flavonols to possess dual inhibition of PLCβ and PDE4 may seem unrelated, from an enzymatic perspective both enzymes cleave phosphodiester bonds. This property is shared by many cellular enzymes including phospholipases C and D, DNases, RNases, and restriction endonucleases, which cleave phosphodiester bonds in DNA or RNA. Classically, cyclic-nucleotide PDEs are well recognized therapeutic targets in ASM since inhibition of PDEs maintain elevated cAMP levels that favor ASM relaxation (10). Activation of the PLCβ pathway initiates the same enzymatic process (i.e., cleavage of a phosphodiesterase bond); however, the downstream by-products produced are different and seem to have a more profound role in ASM contractility. Thus it is plausible that the inhibitory action of PLCβ may contribute more significantly to the profound relaxation effects on ASM we observed in our ex vivo and in vivo studies.

The PLCβ enzyme is a plasma membrane associated protein activated by Gq proteins after procontractile agonists such as histamine, ACh, and cysteinyl leukotrienes bind to their Gq-coupled receptors. For example, ACh is an endogenous mediator of ASM contraction mediated by its activation of the M3 muscarinic receptor which in turn couples to the Gq protein to activate PLCβ. PLCβ cleaves membrane-associated PIP2 to yield IP3 and DAG. These two second messengers activate parallel intracellular signaling pathways that both favor ASM contraction. IP3 activates its receptor on the SR, inducing an acute increase in cytosolic calcium and an increase in the frequency of calcium oscillations. DAG activates isoforms of PKC, which in turn phosphorylates and activates CPI-17, a rho-kinase-associated protein, which normally phosphorylates and inactivates myosin phosphatase favoring the maintenance of myosin light chain phosphorylation and smooth muscle contraction. Flavonol-mediated inhibition at the level of PLCβ would be expected to attenuate increases in IP3 synthesis, SR calcium release (independent of IP3 receptor blockade), and CPI-17 phosphorylation as demonstrated in the present study. Although our results demonstrate that upstream inhibition of PLCβ could account for interruption of these procontractile downstream signaling pathways in hASM cells, it is possible that there are additional cell signaling targets of flavanols that contribute to their prorelaxant effects. In particular, there is evidence that several members of the flavonoid family also modulate PKC activity (4). Although galangin or fisetin specifically have never been shown to modulate PKC activity, it is plausible that such an interaction may exist. Given the numerous PKC isoforms expressed in hASM, this determination was beyond the scope of the present study but warrants further investigation. We did however, test the possibility of whether galangin or fisetin's prorelaxant effects were also due to direct inhibition of the IP3 receptor. Although our competitive receptor binding assay results clearly demonstrate that neither of these compounds competitively displaces IP3 at the IP3 receptor, it is also plausible that they may be affecting calcium dynamics by a yet unidentified mechanism in addition to upstream PLCβ inhibition.

Taken in totality, our findings suggest that agents capable of dual inhibition of PLCβPDE4 should be further pursued in clinical studies as an adjunctive or additional agent to be utilized for acute relaxation of ASM. The action by which flavonols achieve ASM relaxation appears to be independent of the cellular mechanism activated by β-agonist administration (classically viewed as activation of Gs proteins). The possibility to relieve our dependence on β-agonists for asthma management would be a substantial therapeutic advance and is of clinical relevance to a multitude of patients with asthma. In particular for patients with moderate to severe persistent asthma currently employing both chronic and acute β-agonist strategies, the ability to target a complementary prorelaxant cellular signaling pathway in ASM could tremendously improve efficacy of our pharmacological therapeutic options in asthma.

Although β-agonists are highly effective for the acute relaxation of ASM, there is also a paradoxical loss of this bronchoprotective effect when β-agonists are frequently administered (18). These patients may become hypercontractile to their asthma triggers resulting in worsening overall asthma control and an increased frequency of asthma exacerbations. Patients chronically administered β-agonists may also suffer from the development of tolerance and become effectively “desensitized” from β-agonist-mediated relaxation due to overadministration (7).

The cellular mechanisms mediating this β-agonist desensitization after chronic β-agonist administration has been the subject of a great amount of laboratory investigation. Prior studies using an overexpression of the β2-adrenoceptor (β2AR) demonstrated that this overexpression was associated with an increase in PLCβ signaling and downstream mediators suggesting that cross talk exists between these classic Gs- and Gq-coupled signaling pathways (12). Additionally, Liu et al. (11) demonstrated in rat ASM that chronic β2AR signaling leads to overexpression of M3R and PLCβ1. These findings of chronic β2-agonist-mediated increases in PLCβ are particularly relevant to the present study in which we demonstrate inhibition of the PLCβ enzyme and its associated second messengers, highlighting the potential therapeutic role for PLCβ inhibition in the face of chronic β2-agonist desensitization.

The present study evaluated the acute ASM relaxation potential of flavonols but we did not examine the inflammatory or remodeling components of asthma. Previous studies have demonstrated that the flavonoid compounds used in the present study also have immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and anti-proliferation properties that may be additional beneficial effects in allergic lung diseases (9, 20, 25). Evaluating these compounds for their chronic anti-inflammatory and antiproliferation properties in the airways would be an important complement to the present study. This would offer promise that a single therapeutic agent may target multiple pathophysiological events occurring in allergic asthmatic airways.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study demonstrate an alternative mechanism for achieving ASM relaxation via a pathway that is independent from β-agonist-mediated relaxation. This may be a complementary intervention to assist in addressing some of the mechanistic concerns that have developed as a consequence of administration of long-acting β-agonists, including the negative implications of PLCβ signaling upregulation seen with chronic β-adrenoceptor activation.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grants GM093137 (G. Gallos), GM065281 (C. W. Emala), and GM008464 (C. W. Emala); by the Stony Wold-Herbert Fund (J. Danielsson); and by Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research Grant MRTG-BS-2/15/2014 (J. Danielsson).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.S.B., E.A.T., J.F.P.-Z., C.W.E., and G.G. conception and design of research; A.S.B., J.D., Y.Z., J.F.P.-Z., and C.W.E. performed experiments; A.S.B., J.D., J.F.P.-Z., C.W.E., and G.G. analyzed data; A.S.B., J.D., C.W.E., and G.G. interpreted results of experiments; A.S.B., C.W.E., and G.G. prepared figures; A.S.B. and G.G. drafted manuscript; A.S.B., J.D., E.A.T., C.W.E., and G.G. edited and revised manuscript; A.S.B., J.D., E.A.T., Y.Z., J.F.P.-Z., C.W.E., and G.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beghe B, Rabe KF, Fabbri LM. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor therapy for lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188: 271–278, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capasso R, Tavares IA. Effect of the flavonoid galangin on urinary bladder rat contractility in-vitro. J Pharm Pharmacol 54: 1147–1150, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danielsson J, Perez-Zoghbi J, Bernstein K, Barajas MB, Zhang Y, Kumar S, Sharma PK, Gallos G, Emala CW. Antagonists of the TMEM16A calcium-activated chloride channel modulate airway smooth muscle tone and intracellular calcium. Anesthesiology 123: 569–581, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gamet-Payrastre L, Manenti S, Gratacap MP, Tulliez J, Chap H, Payrastre B. Flavonoids and the inhibition of PKC and PI 3-kinase. Gen Pharmacol 32: 279–286, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gosens R, Stelmack GL, Dueck G, McNeill KD, Yamasaki A, Gerthoffer WT, Unruh H, Gounni AS, Zaagsma J, Halayko AJ. Role of caveolin-1 in p42/p44 MAP kinase activation and proliferation of human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L523–L534, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hotta K, Emala CW, Hirshman CA. TNF-α upregulates Giα and Gqα protein expression and function in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 276: L405–L411, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson M. The β-adrenoceptor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 158: S146–S153, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khayyal MT, el-Ghazaly MA, el-Khatib AS, Hatem AM, de Vries PJ, el-Shafei S, Khattab MM. A clinical pharmacological study of the potential beneficial effects of a propolis food product as an adjuvant in asthmatic patients. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 17: 93–102, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HH, Bae Y, Kim SH. Galangin attenuates mast cell-mediated allergic inflammation. Food Chem Toxicol 57: 209–216, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krymskaya VP, Panettieri RA Jr. Phosphodiesterases regulate airway smooth muscle function in health and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol 79: 61–74, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu YH, Wu SZ, Wang G, Huang NW, Liu CT. A long-acting β2-adrenergic agonist increases the expression of muscarine cholinergic subtype3 receptors by activating the β2-adrenoceptor cyclic adenosine monophosphate signaling pathway in airway smooth muscle cells. Mol Med Rep 11: 4121–4128, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGraw DW, Almoosa KF, Paul RJ, Kobilka BK, Liggett SB. Antithetic regulation by β-adrenergic receptors of Gq receptor signaling via phospholipase C underlies the airway β-agonist paradox. J Clin Invest 112: 619–626, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMahon AW, Levenson MS, McEvoy BW, Mosholder AD, Murphy D. Age and risks of FDA-approved long-acting β2-adrenergic receptor agonists. Pediatrics 128: e1147–e1154, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuta K, Gallos G, Zhu D, Mizuta F, Goubaeva F, Xu D, Panettieri RA Jr, Yang J, Emala CW Sr. Expression and coupling of neurokinin receptor subtypes to inositol phosphate and calcium signaling pathways in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L523–L534, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morello S, Vellecco V, Alfieri A, Mascolo N, Cicala C. Vasorelaxant effect of the flavonoid galangin on isolated rat thoracic aorta. Life Sci 78: 825–830, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson HS, Weiss ST, Bleecker ER, Yancey SW, Dorinsky PM, Group SS. The Salmeterol Multicenter Asthma Research Trial: a comparison of usual pharmacotherapy for asthma or usual pharmacotherapy plus salmeterol. Chest 129: 15–26, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park HH, Lee S, Oh JM, Lee MS, Yoon KH, Park BH, Kim JW, Song H, Kim SH. Anti-inflammatory activity of fisetin in human mast cells (HMC-1). Pharmacol Res 55: 31–37, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Meta-analysis: respiratory tolerance to regular β2-agonist use in patients with asthma. Ann Intern Med 140: 802–813, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shmigol AV, Eisner DA, Wray S. Simultaneous measurements of changes in sarcoplasmic reticulum and cytosolic. J Physiol 531: 707–713, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shu YS, Tao W, Miao QB, Lu SC, Zhu YB. Galangin dampens mice lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Inflammation 37: 1661–1668, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer WO, Suissa S, Ernst P, Horwitz RI, Habbick B, Cockcroft D, Boivin JF, McNutt M, Buist AS, Rebuck AS. The use of β-agonists and the risk of death and near death from asthma. N Engl J Med 326: 501–506, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Townsend EA, Emala CW Sr. Quercetin acutely relaxes airway smooth muscle and potentiates β-agonist-induced relaxation via dual phosphodiesterase inhibition of PLCβ and PDE4. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 305: L396–L403, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Townsend EA, Siviski ME, Zhang Y, Xu C, Hoonjan B, Emala CW. Effects of ginger and its constituents on airway smooth muscle relaxation and calcium regulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 48: 157–163, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Townsend EA, Zhang Y, Xu C, Wakita R, Emala CW. Active components of ginger potentiate β-agonist-induced relaxation of airway smooth muscle by modulating cytoskeletal regulatory proteins. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 50: 115–124, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen M, Wu J, Luo H, Zhang H. Galangin induces autophagy through upregulation of p53 in HepG2 cells. Pharmacology 89: 247–255, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zha WJ, Qian Y, Shen Y, Du Q, Chen FF, Wu ZZ, Li X, Huang M. Galangin abrogates ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation via negative regulation of NF-κB. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013: 767689, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]