Abstract

Background and Objective

The present study was aimed at determining the effects of experimental hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism on tissue thyroid hormones by a mass spectrometry-based technique.

Methods

Rats were subjected to propylthiouracil treatment or administration of exogenous triiodothyronine (T3) or thyroxine (T4). Tissue T3 and T4 were measured by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry in the heart, liver, kidney, visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue, and brain.

Results

Baseline tissue T3 and T4 concentrations ranged from 0.2 to 20 pmol ∙ g-1 and from 3 to 125 pmol ∙ g-1, respectively, with the highest values in the liver and kidney, and the lowest values in the adipose tissue. The T3/T4 ratio (expressed as a percentage) was in the 7-20% range in all tissues except the brain, where it averaged 75%. In hypothyroidism, tissue T3 was more severely reduced than serum free T3, averaging 1-6% of the baseline versus 30% of the baseline. The extent of tissue T3 reduction, expressed as percentage of the baseline, was not homogeneous (p < 0.001), with liver = kidney > brain > heart > adipose tissue. The tissue T3/T4 ratio significantly increased in all organs except the kidney, averaging 330% in the brain and 50-90% in the other tissues. By contrast, exogenous T3 and T4 administration produced similar increases in serum free T3 and in tissue T3, and the relative changes were not significantly different between different tissues.

Conclusions

While the response to increased thyroid hormones availability was similar in all tissues, decreased thyroid hormone availability induced compensatory responses, leading to a significant mismatch between changes in serum and in specific tissues.

Key Words: Tissue thyroid hormones, Mass spectrometry, Hypothyroidism, Deiodinases

Introduction

Thyroid hormones (THs) produce their functional effects by interacting with the well-characterized nuclear TH receptors and possibly other membrane or intracellular receptors [1]. The biological effects of THs depend on their cellular concentrations, which exhibit a complex relationship with serum TH concentration because of the complexities of tissue TH metabolism and transmembrane TH transport [2,3,4,5,6,7]. As a consequence, the assay of THs in serum may not be an accurate index of the functional state. Discrepancy between plasma and tissue TH homeostasis has been reported in rare genetic diseases such as MCT8 deficiency [8]. It has also been suggested to occur in common clinical conditions such as heart failure [9], as well as in some patients subjected to replacement therapy after thyroidectomy who still display symptoms related to hypothyroidism in spite of a normal plasma TH profile [10,11].

While the assay of plasma TH has been extensively validated and is largely used in routine clinical practice, determining tissue TH concentration is much more challenging. Immunological methods have been occasionally used by expert investigators [12,13,14,15], but the assay procedure is quite complex, its final yield is uncertain, and cross-reactivity might occur. Mass spectrometry (MS) coupled to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) has been proposed as a highly specific and sensitive technique to assay TH. MS-based techniques have been validated in plasma [16] and they appear to be superior to the classical immunological methods in specific groups of patients. Experimental investigations have shown that similar methods can be applied to tissue homogenates [17,18,19,20,21,22], and we have recently described an HPLC-MS/MS technique which includes a derivatization step and allows the assay of tissue triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) in tissue samples weighing only 50-300 mg [23].

In the present investigation, HPLC-MS/MS was used to determine tissue-specific T3 and T4 concentration in rat organs under control conditions, in propylthiouracil-induced hypothyroidism, and after administration of exogenous T3 or T4. Our aim was to characterize tissue TH distribution and the T3/T4 ratio, and to evaluate whether the effects of experimental hypo- and hyperthyroidism were homogeneous in different organs.

Methods

Chemicals

T4 and 3,3′,5-T3 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo., USA), whereas 13C6-T4 (thyroxine-[13C6]∙HCl) and 13C6-T3 (3,5,3′-triiodothyronine-[13C6]∙HCl) were from IsoScience (King of Prussia, Pa., USA). Unless otherwise specified, all other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich. Solvents for HPLC-MS/MS measurements were LC-MS grade, and the other chemicals were HPLC or reagent grade.

Experimental Procedures

Principles of laboratory animal care were followed and the study was performed in accordance with the European Directive (2010/63/UE) and Italian law (D.L. 26/2014). The study was approved by the Local Ethical Approval Panel. Twenty Wistar outbred albino rats (2-3 months of age, both genders) were kept in our local animal husbandry facility and housed 1-2 per cage in a room with controlled 12-/12-hour light/dark cycle, temperature (21 ± 0.5°C), and relative humidity (55 ± 2%). They were fed with 4RF18 standard rat diet for long-term maintenance (Mucedola, Milano, Italy). Water and food were available ad libitum. All efforts were made to minimize suffering. Rats were randomly allocated to receive one of the following treatments: (1) administration of 6-propyl-2-thiouracil in drinking water to a final concentration of 0.05% (w/v) for 3 weeks, (2) subcutaneous infusion of synthetic T3 at the dose of 6 μg/kg/day for 3 consecutive days through an osmotic pump (Model 2002, Alzet, Palo Alto, Calif., USA) subcutaneously implanted in the interscapular space, or (3) subcutaneous injection of T4 at a dose of 250 μg/kg/day for 6 consecutive days. Age- and gender-matched rats were treated with subcutaneous infusion of saline for 6 days and used as controls. In each experimental group, a similar number of females and males were used (the difference was equal to one at most).

At the end of each specific treatment, animals were anesthetized (50 mg/kg Zoletil® + 3 mg/kg xylazine) to collect 2 ml of blood from the femoral vein, and then sacrificed by a lethal KCl injection. The following organs were harvested, rinsed in saline to remove residual blood, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until usage: brain, heart (right ventricle), kidney, liver, and white subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue. Blood was immediately centrifuged at 5,000 g for 10 min and serum was assayed to determine the circulating levels of free T3 and T4 by AIA 21 analyzer (Eurogenetics-Tosoh, Turin, Italy).

Tissue T3 and T4 were assayed by HPLC coupled to tandem MS, as described previously [23], with minor changes. Homogenization, extraction, and assay techniques are detailed in the supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000443523) and they were different for denser tissues (heart, liver, and kidney: procedure a) and for lipid-rich tissues (adipose tissues and brain: procedure b). Quality control data for the two procedures are summarized in table 1, and further details are provided in the supplementary material.

Table 1.

Quality control data for tissue TH assay

| Procedure a |

Procedure b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T3, % | T4, % | T3, % | T4, % | |

| Accuracy | 103 ± 4 | 93 ± 3 | 100 ± 2 | 91 ± 2 |

| Precision | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 1.2 |

| Recovery | 47 ± 2 | 23 ± 2 | 99 ± 7 | 114 ± 6 |

| Matrix effect | 63 ± 4 | 99 ± 4 | 36 ± 5 | 67 ± 13 |

Data represent means ± SD. Accuracy is the ratio of measured concentration to spiked concentration; precision is the coefficient of variation of repeated measurements within the same assay; recovery is the ratio of internal standard spiked before extraction to internal standard spiked after extraction; matrix effect is the ratio of internal standard spiked after extraction to internal standard dissolved in the reconstitution solvent. The table summarizes results obtained in the liver (for procedure a) and brain (for procedure b). See supplementary material for further details.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SEM. Differences between groups were analyzed by ANOVA. Pairwise group comparisons were performed by Tukey's post hoc test (when comparing different tissues) or by Dunnett's post hoc test (when comparing different conditions vs. control). The threshold of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. GraphPad Prism version 6.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif., USA) was used for data processing and statistical analysis.

Results

The effectiveness of the experimental procedures used to induce hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism was confirmed by the assay of the free fractions of T3 and T4 in serum, which are summarized in table 2. Treatment with propylthiouracil determined a 70% decrease of free T3, while free T4 was virtually undetectable. Infusion of T3 and T4 was meant to produce a moderate increase of serum free T3, which was about 2-fold and 6-fold higher than the baseline, in the respective treatment conditions. During the time course of this investigation, no animal showed overt signs of pain or distress, as assessed by behavioral reactions.

Table 2.

Serum THs

| Group | fT3, pmol l−1 | fT4, pmol l−1 | fT3/fT4, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 5) | 4.54 ± 0.16 | 13.7 ± 0.29 | 33.4 ± 1.9 |

| Propylthiouracil (n = 4) | 1.42 ± 0.03 | n.q. | n.q. |

| T3 treatment (n = 4) | 9.11 ± 1.52 | 3.46 ± 0.17 | 269.0 ± 57.2 |

| T4 treatment (n = 3) | 26.6 ± 8.75 | 94.2 ± 12.1 | 28.8 ± 6.3 |

Data represent means ± SEM. n.q. = not quantifiable since free T4 (fT4) was below the detection limit of the assay. The limits of detection for fT3 and fT4 provided by the manufacturer were 0.57 and 1.29 pmol/l, respectively. Group numerosity is different from the other tables because for technical reasons serum fT3 and fT4 were not determined in a few animals. Differences between groups were significantly different for each variable (p < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA).

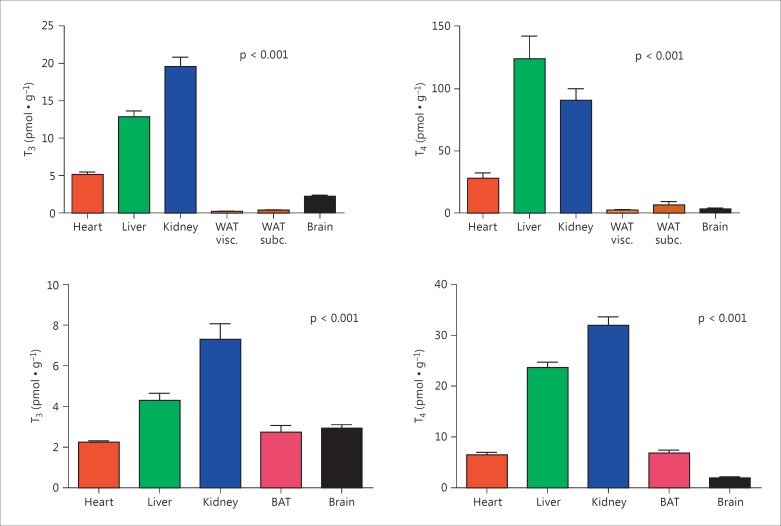

Results of tissue T3 and T4 assay in control animals are shown in the upper panels of figure 1, and reported in the first row of tables 3 and 4. A wide variability was observed in the different organs, spanning two orders of magnitude (about 90-fold for T3 and 55-fold for T4). The liver and kidney were characterized by the highest T3 and T4 concentrations, in the order of 10-20 pmol ∙ g-1 for T3 and 100 pmol ∙ g-1 for T4. The lowest values were found in visceral adipose tissue, namely 0.2 pmol ∙ g-1 for T3 and 2 pmol ∙ g-1 for T4. T3 concentration averaged 6-20% of T4 concentration in all tissues except the brain, where the T3/T4 ratio was significantly higher and averaged about 75% (table 5). Interestingly, a similar profile of T3 and T4 distribution can be derived from the classic paper by Escobar-Morreale et al. [13] (fig. 1, lower panels), although the absolute values obtained by the present assay technique for heart, liver, and kidney were substantially higher (by 2- to 5-fold).

Fig. 1.

The upper panels show the distribution of tissue T3 and T4 in control animals. The lower panels reproduce the results obtained by Escobar-Morreale et al. [13], calculated from table 1 of their paper. WAT = White adipose tissue; BAT = brown adipose tissue. Bars represent means ± SEM of 3-8 hearts per group. Statistical significance refers to differences between groups and was calculated by one-way ANOVA. Pairwise group comparisons performed on the results of the present investigation (upper panels) by Tukey's post hoc test showed that both the differences between WAT (either visceral or subcutaneous) and brain were not statistically significant for T3 and for T4, while all other comparisons between pairs of groups yielded p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Tissue T3

| Group | Heart | Liver | Kidney | WAT visceral | WAT subcutaneous | Brain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 8) | 5.18 ± 0.33 | 12.9 ± 0.81 | 19.7 ± 1.26 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 2.23 ± 0.17 |

| Propylthiouracil (n = 4) | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| T3 treatment (n = 5) | 11.4 ± 3.98 | 19.8 ± 5.40 | 30.6 ± 8.60 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | 0.89 ± 0.09 | 3.52 ± 0.45 |

| T4 treatment (n = 3) | 20.0 ± 6.11 | 74.9 ± 28.5 | 143.2 ± 69.7 | 0.73 ± 0.17 | 1.28 ± 0.31 | 4.84 ± 1.19 |

Results are expressed as pmol · g−1 and represent means ± SEM. WAT = White adipose tissue. Two-way ANOVA yielded p < 0.001 for the effect of treatment and p < 0.001 for the effect of tissue. See figure 2 for pairwise group comparisons after normalization to the baseline.

Table 4.

Tissue T4

| Group | Heart | Liver | Kidney | WAT visceral | WAT subcutaneous | Brain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 8) | 27.9 ± 4.40 | 124.3 ± 8.20 | 90.9 ± 4.19 | 2.26 ± 0.16 | 6.45 ± 0.95 | 3.13 ± 0.35 |

| Propylthiouracil (n = 4) | 0.74 ± 0.50 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| T3 treatment (n = 5) | 9.48 ± 0.56 | 29.8 ± 6.66 | 19.9 ± 1.03 | 0.92 ± 0.27 | 2.88 ± 0.81 | 0.88 ± 0.12 |

| T4 treatment (n = 3) | 237.2 ± 83.4 | 791.1 ± 121.3 | 859.2 ± 307.4 | 12.2 ± 1.38 | 42.5 ± 24.0 | 23.1 ± 4.27 |

Results are expressed as pmol · g−1 and represent means ± SEM. WAT = White adipose tissue. Two-way ANOVA yielded p < 0.001 for the effect of treatment and p < 0.001 for the effect of tissue. See figure 2 for pairwise group comparisons after normalization to the baseline.

Table 5.

Tissue T3/T4 ratio

| Group | Heart | Liver | Kidney | WAT visceral | WAT subcutaneous | Brain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 8) | 20.1 ± 1.9 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 21.7 ± 0.9 | 9.5 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 75.3 ± 10.0a |

| Propylthiouracil (n = 4) | 51.4 ± 17.5 | 66.3 ± 17.5* | 27.6 ± 4.9 | 87.5 ± 7.6** | 59.1 ± 17.4** | 331.0 ± 97.1**, a |

| T3 treatment (n = 5) | 122.6 ± 49.2** | 74.0 ± 34.6* | 156.4 ± 51.4** | 72.4 ± 17.9** | 42.1 ± 11.4** | 421.1 ± 59.6**, b |

| T4 treatment (n = 3) | 8.7 ± 0.6 | 10.1 ± 4.4 | 15.5 ± 2.2 | 6.0 ± 1.1 | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 20.5 ± 1.7c |

Results are expressed as percentages and represent means ± SEM. WAT = White adipose tissue. Two-way ANOVA yielded p < 0.001 for the effect of treatment and p < 0.001 for the effect of tissue. Comparisons between specific groups performed within rows and within columns yielded the results summarized by the following symbols:

p < 0.05 versus control;

p < 0.01 versus control by Dunnet's post hoc test;

p < 0.01 versus any other tissue;

p < 0.05 versus liver and p < 0.01 versus any other tissue;

p < 0.05 versus heart and p < 0.01 versus WAT by Tukey's post hoc test.

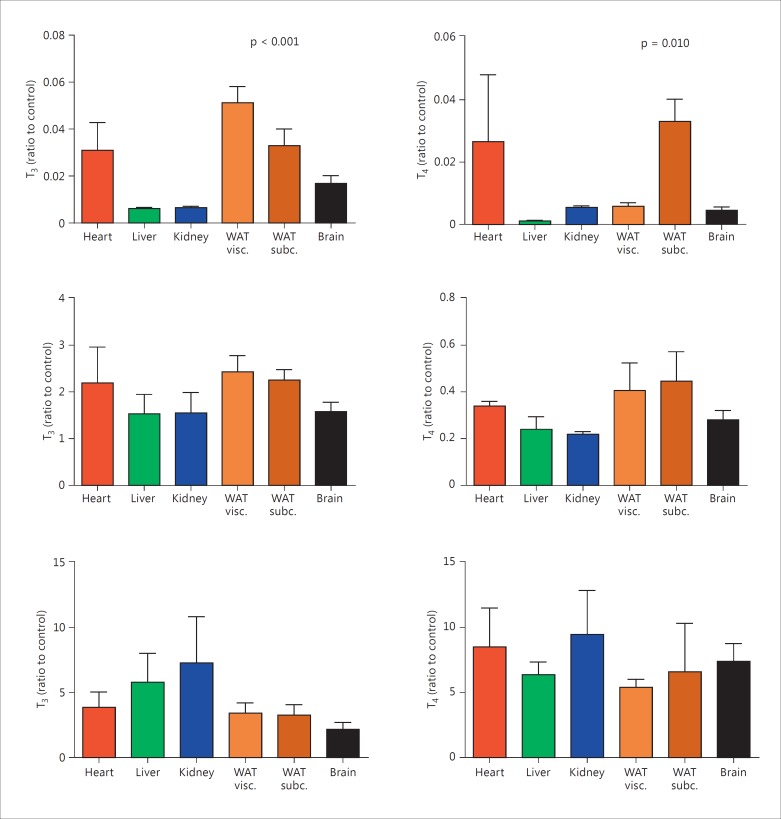

Tissue T3 and T4 concentrations measured after treatment with propylthiouracil, exogenous T3, or exogenous T4 are summarized in tables 3 and 4, while in figure 2 they are expressed as a ratio to the average baseline concentration. Propylthiouracil administration caused a remarkable reduction of tissue T3 and T4 levels in all tissues. The effect was not homogeneous since the ratio to baseline concentration showed a wide variability for both T3 and T4. In particular, the reduction was more severe in the liver, kidney, and brain than in the heart and adipose tissue. Serum T3 underestimated tissue hypothyroidism since tissue T3 was always lower than 6% of the baseline, while serum T3 values averaged about 30% of the baseline. A different trend was observed for serum T4, which was virtually undetectable and therefore appeared to be more severely reduced than tissue T4. Interestingly, propylthiouracil treatment caused a significant increase in the T3/T4 ratio in all tissues, except the kidney (table 5).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of tissue T3 and T4 in animals treated with propylthiouracil (top), exogenous T3 (middle), and exogenous T4 (bottom). The concentrations were normalized to the average values obtained in control animals. WAT = White adipose tissue. Bars represent means ± SEM of 3-8 hearts per group. Statistical significance refers to differences between groups and was calculated by one-way ANOVA. Pairwise group comparisons performed in the propylthiouracil group by Tukey's post hoc test showed that the following differences between pairs of groups were statistically significant (p < 0.05): visceral WAT versus liver, visceral WAT versus kidney, visceral WAT versus brain.

We used two different models of hyperthyroidism, namely exogenous T3 or T4 administration. Treatment with exogenous T3 doubled serum T3 and reduced serum T4 to 25% of the baseline. However, the normal pattern of tissue distribution was conserved since the relative changes in tissue T3 and T4 were close to those occurring in serum.

Exogenous T4 was infused in the last experimental group, at a dose that increased serum T4 by about 7-fold and serum T3 by about 6-fold. Both T3 and T4 were increased in all tissues, and the relative changes versus the baseline did not show significant differences between tissues, although the increase of tissue T3 was slightly lower in the brain. The T3/T4 ratio was similar to the baseline values in all tissues except the brain, where it decreased from 75.3 ± 10.0 to 20.5 ± 1.7% (table 5).

Discussion

We assayed tissue THs in several rat tissues using a novel technique based on MS, which represents a development of the methodology that we have used in previous investigations. The values which we obtained were in general higher than those observed by investigators who used immunological methods [12,13,14,15,24,25,26,27], possibly due to the higher accuracy of the MS technique. Galton et al. [28] reported similar or higher concentrations in kidney and liver, but in that study the homogenates were incubated with β-glucuronidase and therefore tissue concentrations also included glucuronide conjugates of THs.

Previous attempts to assay tissue TH by MS provided similar [18,22] or lower [17,21,23] concentrations. Some differences in tissue extraction were present, and in most previous papers validation parameters were not systematically determined or reported, so a direct comparison is difficult to make. The high accuracy of the present procedure (online suppl. material) and the favorable signal-to-noise ratio associated with sample derivatization [23] may have determined a significant improvement over the previous assays performed in our laboratory.

Additional issues to be taken into account when comparing different studies are the impact of gender differences, developmental age, and the possible persistence of blood in tissue capillaries. Although our samples were rinsed with saline, extensive perfusion was performed in other studies [13] and it may have been more effective in removing residual blood.

The pattern of tissue TH distribution that we have observed is quite consistent with the previous report by Escobar-Morreale et al. [13]. The wide differences in tissue TH concentrations, spanning nearly two orders of magnitude, might reflect differences in the density of TH binding sites. Apart from TH receptors, TH can be bound to several intracellular proteins, such as μ-crystallin, pyruvate kinase M2, aldehyde dehydrogenase, and glutathione S-transferase [21], whose specific tissue concentrations have not been determined so far.

The ratio of T3 to T4 was much higher in the brain than in all other tested tissues. This finding is consistent with extensive brain T4 metabolism. As a matter of fact, it has been estimated that only about 20% of brain T3 derives from the circulation, while the large majority is produced locally through the action of deiodinases that show specific cell distribution [7,29,30].

Remarkable inhomogeneity in tissue TH concentrations was also apparent after inducing hypothyroidism with propylthiouracil. We actually observed that the relative decrease in TH concentration versus the baseline varied from tissue to tissue, implying that the impact of hypothyroidism was different in different tissues. The largest reductions were observed in the liver and kidney, which could be regarded as a homeostatic mechanism since these organs are directly involved in TH inactivation and excretion.

Notably, the T3/T4 ratio was increased versus the baseline in all tissues except the kidney, suggesting that compensatory mechanisms included increased T4 deiodination on the phenolic ring. Increased T4 turnover is also consistent with the observation that serum T4 was much more reduced than serum T3. A possible explanation for this finding is increased activity of D2 deiodinase, which is thought to mediate the bulk of T3 production and is expressed in many tissues, including the brain, heart, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. D2 deiodinase has long been known to be inhibited by T3 and T4 at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels, although direct ubiquitination may also occur [31], and increased D2 activity has been specifically observed in brain, heart, and skeletal muscle in experimental models of hypothyroidism [6,29,32,33,34]. On the other hand, the dominant enzyme in liver and kidney is D1 deiodinase, which is known to be transcriptionally induced by T3 and to be inhibited by propylthiouracil [6,29,32,35], consistent with the different response of the liver and kidney. However, we cannot exclude that the targeted action of propylthiouracil in the thyroid gland, namely inhibition of thyroperoxidase, may also contribute to the response observed in this experimental group.

Another hypothetical mechanism might be represented by changes in tissue TH availability, possibly linked to modulation of TH transporters [2]. As a matter of fact, complex changes in serum and tissue TH concentrations have recently been described in mice showing MCT8 and/or MCT10 deficiency [27], although it has been reported that the thyroid state had little effect on the transcription of T4 transporters, at least in the liver [36].

Our findings underline the importance of local factors in the control of tissue TH concentrations and provide support to the concept that selective tissue hypothyroidism might occur even in the presence of normal concentrations of circulating TH, due to local changes in TH transport or metabolism. There is consistent evidence that this may be the case in heart failure, owing to increased cardiac D3 deiodinase activity [37,38].

Under conditions of increased TH availability, the picture was more homogeneous. Administration of exogenous T3 or T4 produced similar increases in tissue T3 levels in all tested organs, if expressed as ratio to the baseline values. Apparently, compensatory mechanisms were more effective in experimental hypothyroidism than in experimental hyperthyroidism. From an evolutionary point of view this is not surprising. Progressive iodine elution from the earth's crust has made iodine deficiency a major challenge for terrestrial vertebrates, so the mechanisms regulating TH distribution and metabolism have been preferentially tuned against the risk of hypothyroidism [6,39]. The brain is usually thought to be particularly resistant to changes in systemic TH availability, thanks to the expression of both D2 and D3 deiodinases, their complementary regulation, and the presence of a complex network of TH transporters [7,24,30]. We did observe some attempt at compensation during T4 treatment, as the brain T3/T4 ratio decreased from about 75 to about 20%; however, the brain homeostatic mechanism appeared to be limited in our model, in agreement with previous reports [40].

An interesting observation is that T3 treatment lowered tissue T4. This finding might be linked to T3-induced inhibition of TSH secretion, and its potential clinical impact should be considered whenever T3 injections are used.

Our investigation has several limitations: we could not assay the concentrations of free TH in tissues, we did not try to assay TH derivatives (e.g. thyroacetic acid derivatives and thyronamines), we did not determine functional indices of tissue response to TH, and the time frame of the experiments was limited to a few weeks at most. However, we could show that while the response to increased TH availability was similar in all tissues, decreased TH availability induced compensatory responses, probably linked to changes in deiodinase activity and/or in transmembrane TH transport, leading to a significant mismatch between changes in serum and tissue levels, and to a significant inhomogeneity in the extent of tissue hypothyroidism. Further investigation of these issues will be necessary for a better understanding of the pathophysiology of hypothyroidism and for a deeper evaluation of the response to replacement or suppressive therapy.

Disclosure Statement

There is no conflict of interest for any of the authors.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Davis PJ, Leonard JL, Davis FB. Mechanisms of nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hennemann G, Docter R, Friesema EC, de Jong M, Krenning EP, Visser TJ. Plasma membrane transport of thyroid hormones and its role in thyroid hormone metabolism and bioavailability. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:451–476. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.4.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansen J, Friesema ECH, Milici C, Visser TJ. Thyroid hormone transporters in health and disease. Thyroid. 2005;15:757–768. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bianco AC, Kim BW. Deiodinases: implications of the local control of thyroid hormone action. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2571–2579. doi: 10.1172/JCI29812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visser WE, Friesema EC, Visser TJ. Minireview: thyroid hormone transporters: the knowns and the unknowns. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:1–14. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsen PR, Zavacki AM. Role of iodothyronine deiodinases in the physiology and pathophysiology of thyroid hormone action. Eur Thyroid J. 2012;1:232–242. doi: 10.1159/000343922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wirth EK, Schweizer U, Köhrle J. Transport of thyroid hormone in brain. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:98. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumitrescu AM, Refetoff S. The syndromes of reduced sensitivity to thyroid hormone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3987–4003. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerdes AM, Iervasi G. Thyroid replacement therapy and heart failure. Circulation. 2010;122:385–393. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.917922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biondi B, Wartofsky L. Combination treatment with T4 and T3: toward personalized replacement therapy in hypothyroidism? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2256–2271. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiersinga WM. Paradigm shifts in thyroid hormone replacement therapies for hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:164–174. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroeder-van der Elst JP, van der Heide D. Effects of 5,5′-diphenylhydantoin on thyroxine and 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine concentrations in several tissues of the rat. Endocrinology. 1990;126:186–191. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-1-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Escobar-Morreale HF, Obregón MJ, Escobar del Rey F, Morreale de Escobar G. Replacement therapy for hypothyroidism with thyroxine alone does not ensure euthyroidism in all tissues, as studied in thyroidectomized rats. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2828–2838. doi: 10.1172/JCI118353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escobar-Morreale HF, del Rey FE, Obregón MJ, de Escobar GM. Only the combined treatment with thyroxine and triiodothyronine ensures euthyroidism in all tissues of the thyroidectomized rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2490–2502. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.6.8641203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedraza PE, Obregon MJ, Escobar-Morreale HF, del Rey FE, de Escobar GM. Mechanisms of adaptation to iodine deficiency in rats: thyroid status is tissue specific. Its relevance for man. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2098–2108. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soldin OP, Soldin SJ. Thyroid hormone testing by tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saba A, Chiellini G, Frascarelli S, Marchini M, Ghelardoni S, Raffaelli A, Tonacchera M, Vitti P, Scanlan TS, Zucchi R. Tissue distribution and cardiac metabolism of 3-iodothyronamine. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5063–5073. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunisue T, Fisher JW, Kannan K. Determination of six thyroid hormones in the brain and thyroid gland using isotope-dilution liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2011;83:417–424. doi: 10.1021/ac1026995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ackermans MT, Kettelarij-Haas Y, Boelen A, Endert E. Determination of thyroid hormones and their metabolites in tissue using SPE UPLC-tandem MS. Biomed Chromatogr. 2012;26:485–490. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoefig CS, Renko K, Piehl S, Scanlan TS, Bertoldi M, Opladen T, Hoffmann GF, Klein J, Blankenstein O, Schweizer U, Köhrle J. Does the aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase contribute to thyronamine biosynthesis? Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;349:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weltman NY, Ojamaa K, Savinova OV, Chen YF, Schlenker EH, Zucchi R, Saba A, Colligiani D, Pol CJ, Gerdes AM. Restoration of cardiac tissue thyroid hormone status in experimental hypothyroidism: a dose-response study in female rats. Endocrinology. 2013;154:2542–2552. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariotti V, Melissari E, Iofrida C, Righi M, Di Russo M, Donzelli R, Saba A, Frascarelli S, Chiellini G, Zucchi R, Pellegrini S. Modulation of gene expression by 3-iodothyronamine: genetic evidence for a lipolytic pattern. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saba A, Donzelli R, Colligiani D, Raffaelli A, Nannipieri M, Kusmic C, Dos Remedios CG, Simonides WS, Iervasi G, Zucchi R. Quantification of thyroxine and 3,5,3′-triiodo-thyronine in human and animal hearts by a novel liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method. Horm Metab Res. 2014;46:628–634. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1368717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broedel O, Eravci M, Fuxius S, Smolarz T, Jeitner A, Grau H, Stoltenburg-Didinger G, Plueckhan H, Meinhold H, Baumgartner A. Effects of hyper- and hypothyroidism on thyroid hormone concentrations in regions of the rat brain. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E470–E480. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00043.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao X-H, Di Cosmo C, Dumitrescu AM, Hernandez A, Van Sande J, St Germain DL, Weiss RE, Galton VA, Refetoff S. Distinct roles of deiodinases on the phenotype of Mct8 defect: a comparison of eight different mouse genotypes. Endocrinology. 2011;152:1180–1191. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reyns GE, Janssens KA, Buyse J, Kühn ER, Darras VM. Changes in thyroid hormone levels in chicken liver during fasting and refeeding. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 2002;132:239–245. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(01)00528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller J, Mayler S, Visser TJ, Darras VM, Boelen A, Frappart L, Mariotta L, Verrey F, Heuer H. Tissue-specific alterations in thyroide hormone homeostasis in combined Mct10 and Mct8 deficiency. Endocrinology. 2014;155:315–325. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galton VA, Hernandez A, St Germain DL. The 5′-deiodinases are not essential for the fasting-induced decrease in circulating thyroid hormone levels in male mice: possible roles for the type 3 deiodinase and tissue sequestration of hormone. Endocrinology. 2014;155:3172–3181. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bianco AC, Salvatore D, Gereben B, Berry MJ, Larsen PR. Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology, and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:38–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.1.0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schweizer U, Köhrle J. Function of thyroid hormone transporters in the central nervous system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3695–3973. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arrojo e Drigo F, Fonseca TL, Werneck-de-Castro JPS, Bianco AC. Role of type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase (D2) in the control of thyroid hormone signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3956–3964. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silva JE, Gordon MB, Crantz FR, Leonard JL, Larsen PR. Qualitative and quantitative differences in the pathways of extrathyroidal triiodothyronine generation between euthyroid and hypothyroid rats. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:898–907. doi: 10.1172/JCI111313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner MS, Morimoto R, Dora JM, Benneman A, Pavan R, Maia AL. Hypothyroidism induces type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase expression in mouse heart and testis. J Mol Endocrinol. 2003;31:541–550. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0310541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsili A, Ramadan W, Harney JW, Mulcahey M, Castroneves LA, Goemann IM, Wajner SM, Huang SA, Zavacki AM, Maia AL, Dentice M, Salvatore D, Silva JE, Larsen PR. Type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase levels are higher in slow-twitch than in fast twitch mouse skeletal muscle and are increased in hypothyroidism. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5952–5960. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zavacki AM, Ying H, Christoffolete MA, Aerts G, So E, Harney JW, Cheng SY, Larsen PR, Bianco AC. Type 1 iodothyronine deiodinase is a sensitive marker of peripheral thyroid status in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1568–1575. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peeters RP, Friesema EC, Docter R, Hennemann G, Visser TJ. Effects of thyroid state on the expression of hepatic thyroid hormone transporters in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E1232–E1238. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00214.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wassen FW, Schiel AE, Kuiper GG, Kaptein E, Bakker O, Visser TJ, Simonides WS. Induction of thyroid hormone-degrading deiodinase in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2812–2815. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.7.8985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pol CJ, Muller A, Zuidwijk MJ, van Deel ED, Kaptein E, Saba A, Marchini M, Zucchi R, Visser TJ, Paulus WJ, Duncker DJ, Simonides WS. Left-ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction is associated with a cardiomyocyte-specific hypothyroid condition. Endocrinology. 2011;152:669–679. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obregon MJ, Escobar del Rey F, Morreale de Escobar G. The effect of iodine deficiency on thyroid hormone deiodination. Thyroid. 2005;15:917–929. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharlin DS, Gilbert ME, Taylor MA, Ferguson DC, Zoeller RT. The nature of the compensatory response to low thyroid hormone in the developing brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:153–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data